Letter writing was the main form of communication with loved ones during the Civil War. The Union Army had a post office near forts and camps. The Union Army also had a mail service that followed the armies for the men where they could purchase stamps and mail their letters. In 1864, the U.S. Mail Service announced that Union soldiers could send their letters home for free as long as they wrote “Soldier’s Letter” on the outside of the envelope. [1]

“Where and when a soldier had an opportunity to put pen (or pencil) to paper depended on what time of year it was, whether that soldier’s unit was actively campaigning, and what objects might be available to assist in the mechanics of writing.” [2]

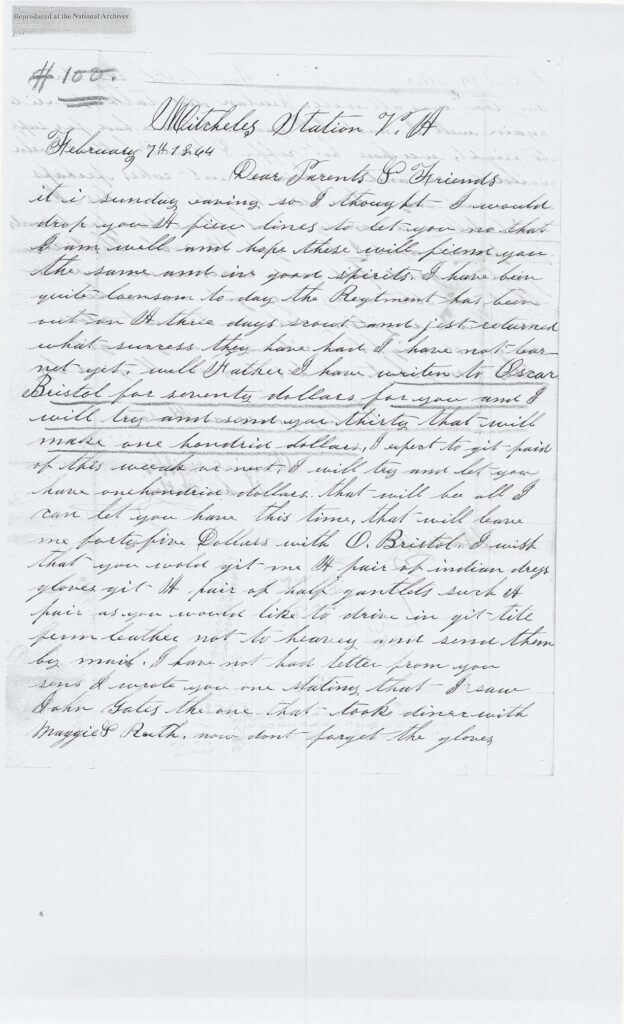

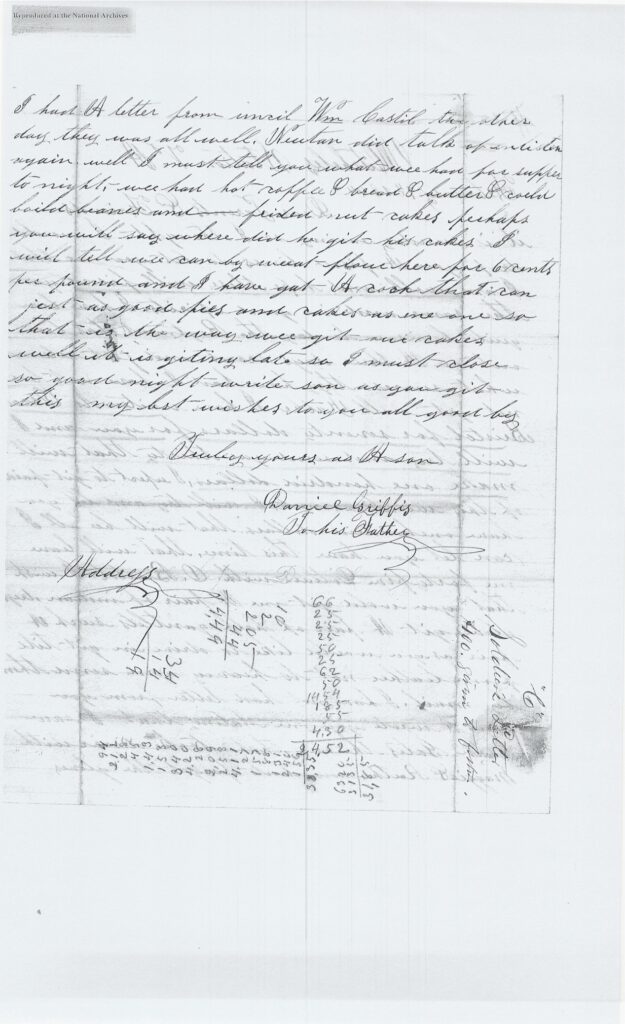

One of the letters that Daniel Griffis wrote to his father was preserved in a pension file claim of his father Joel Griffis. [3] The two page letter was written while Daniel, age 32, and his regiment were camped in Mitchell’s Station, Virginia in the winter of 1863-1864. Daniel was a wagon master in the New York First Dragoons Regiment in the Civil War.

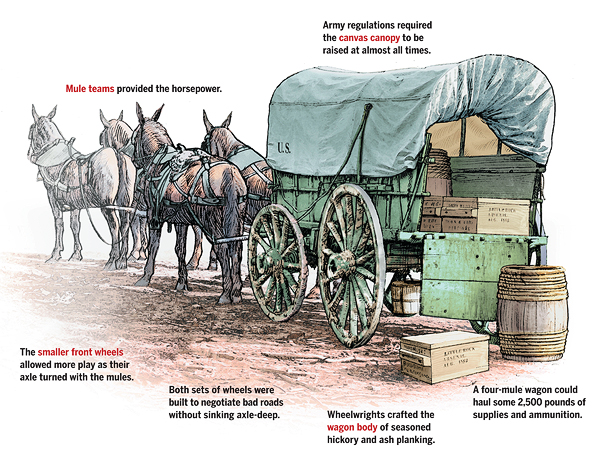

It is not known what type of wagon Daniel Griffis handled. The illustration above represents the predominant wagon used by Union forces during the war. Brothers Henry and Clement Studebaker set up a blacksmith shop in South Bend, Ind., in 1852, they started making wagons. Earning a reputation for quality and durability, they expanded into the manufacture of carriages in 1857. That same year they landed a subcontract to build supply wagons for the U.S. Army. [4]

As James Riley Brown indicates in his recollections of the Regiment, Mitchell’s Station (where Daniel was able to compose this letter) was the winter camp for the Dragoons:

“A year and a half had passed since we donned the blue, and we were now counted among the veterans, thoroughly inured to the vicissitudes of army experience. With the exception of our short stay in Manassas, we had for seven months been so incessantly on the move that we could never tell where night would overtake us.”[5]

The letter touches on a number of subjects that provide a glimpse of everyday life as a soldier during war. You can get an idea of what Daniel was like and what he thought of while away from home. The letter also touches on some of Daniel’s relationships with his family and friends. Like many of the Civil War soldiers, Daniel had a limited education. Daniel’s education was probably at the fourth grade level. While many young men from rural areas had never attended school and could neither read nor write, Daniel was able to put his thoughts on paper and often spelled words phonetically. As reflected in the letter, his limited education led to many words being mispelled or sentences left incomplete. For phonetic spellings I have provided the intended words in parentheses.

(Click on a specific page of the letter to view a large version of the image.)

The underlined sentences and the numbers written on the second page were probably notations made by Daniel’s father Joel Griffis. The letter was used to support Joel’s claim that he was dependent upon his son’s financial assistance. The addition on the second page perhaps was a tally of money that Daniel had sent to his father.

The following is a transcription of the original letter:

Mitcheles (Mitchell’s) Station, Virginia

February 7th, 1864

Dear Parents and Friends

It is sunday eavning (evening) so I thought I would drop you A fieu (few) lines to let you no (know) that I am well and hope there will fiend (find) you the same and in good spirits. I have been quite loensome (lonesome) to day the Regiment has been out on A three days scout and just returned what success they have had I have not lear net (learned) yet. well Father I have written to Oscar Bristol for seventy dollars for you and I will try and send you thirty that will make one hundred dollars. I expect to git (get) paid of this week or next. I will try and let you have one hundred dollars. that will be all I can let you have this time. that will leave me forty five Dollars with O. Bristol. I wish that you would git (get) me a pair of indian drys gloves git (get) a pair of half guntlets such A pair as you would like to drive in get tite (tight) firm leather not to heavey (too heavy) and send them by mail. I have not had letter from you (your) sons. I wrote you one stating that I saw John Gates the one that took dinner with Maggie and Ruth. now dont (don’t) forget the gloves.

[end of page one)

I had A letter from uncil Wm (uncle William) lastil (?) the other day they was all well. Newtan (?) did talk of inlisten (enlisting) again well I must tell you what wee (we) had for supper to night. wee (we) had hot coffee & bread & butter & cold boild beanes (boiled beans) and frided (fried) nut cakes perhaps you will say where did he git (get) his cakes. I will tell you wee (we) can by (buy) weat (wheat) flour here for 6 cents per pound and I have got A cook that can jest (just) as good pies and cake as ene one (anyone) so that is the way wee git (we get) our cakes, well it is giting (getting) late so I must close so good night write son (soon) as you git (get) this my best wishes to you all good bye.

Truly yours as A son

Daniel Griffis

To his father

Daniel’s letter contains the following subjects:

- The Regiment’s scout trip;

- Discussion on monetary support to his father and obtaining funds owed by Oscar Bristol;

- Obtaining leather gloves for his wagon master duties;

- A brief discussion about family and friends; and

- The quality of food while at winter camp at Mitchell’s Station.

The Regiment’s expedition that Daniel references in the letter refers to a forward movement of the Union Army to the Robertson River. The following is James R. Brown’s recollection of the reconnaissance:

“The Dragoons crossed Robertson River at Moot’s Ford, where the enemy’s calvary pickets were met and driven in. The principle fighting, however, was a sharp artillery duel, and a brush we had with a brigade of infantry, in which we lost three killed and eight wounded. Our infantry had some sharp fighting, sustaining a loss of three hundred. After floundering around in the deep mud, we returned to camp, the whole affair, like most of Meade’s later movements, proving a failure.” [6]

The discussion about money appears to be in response to an earlier request from his father for monetary assistance. One hundred dollars in 1865 is equivalent in purchasing power to about $1,596.50 today. [7] Sending one hundred dollars to his father was a considerable sum. Joel was 57 years old and supporting his second family of three children. He no longer was a farmer in Mayfield. He was living in Gloversville and working as a teamster. [8] He was financially struggling.

Daniel intended to ask for $70 dollars from Oscar Bristol to be sent to his father. Oscar Bristol is believed to be a cousin of Daniel’s late wife Augusta Bristol who passed away at a young age of 29 in 1861. Daniel was a Blacksmith prior to his enlistment into the service in August 1862. It appears that Daniel left Mayfield, New York after his wife passed away and went to Stillwater, New York to work for her extended family. Stillwater is approximately 200 miles to the west of Mayfield. Daniel provided his services to Oscar Bristol, a farmer, who lived in Stillwater, New York and owed Daniel $115.00. [9] In addition to the $70.00 from Oscar Bristol, Daniel intended to mail and additional $30.00 to his father and “…that will leave me forty five Dollars with O. Bristol”. Daniel wrote that “that will be all I can let you have this time”, suggesting he sent money back to his father on a number of occasions.

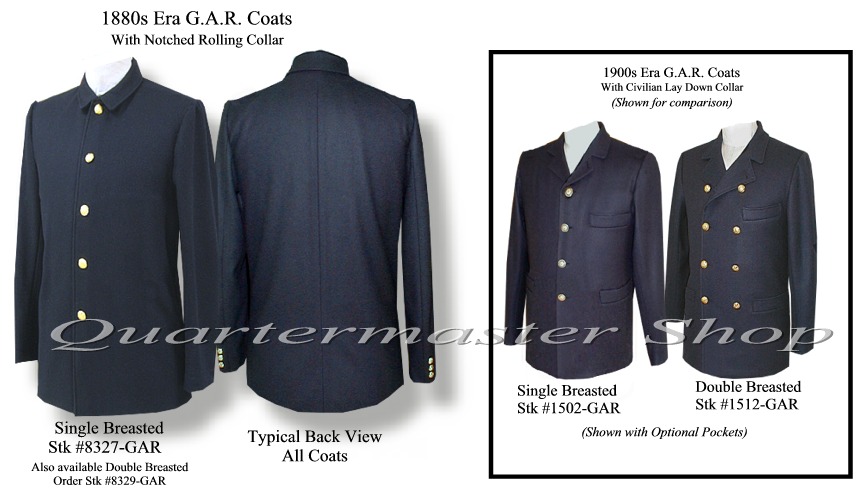

The arduous demands of managing and driving supply wagons that had two, four and sometimes six horses, depending on the size and weight of the load, certainly demanded having a good pair of gloves.

“Among the teamster and wagon man’s many enemies were shoddy, stump-filled roads, sucking mud that threatened to swallow up teams and wagons whole, and lame or otherwise injured animals. Drivers often found themselves down in the dirt, digging out their wagons or helping mechanics with repairs. They were also responsible for the care of their hard-working teams and constantly fed their animals from the sacks of forage they lugged in each 2,500- to 2,800- pound wagonload.” [10]

Daniel’s family lived in an area of New York state where the glove making industry provided jobs for generations of families, making the Gloversville community a center of leather production early in its history. There were already 40 small glove and mitten factories there by 1852. The city would become the center of the American glovemaking industry for many years. [13] His father certainly would have access to buying the finest wagon gloves for his son.

Daniel requested tight firm leather gloves, specifically a pair of half gauntlet style gloves that were suitable for driving a wagon and withstanding the nature and duties of a wagon master. He also specified that he wanted gloves that were made out of supple leather, similar to indian dry leather processed gloves. The Indian process of tanning rendered a soft, pliable and durable leather. [14] Daniel went on in the letter to talk about family but came back to the subject of the gloves to underscore his need for them: “now dont forgit the gloves“.

In his brief letter, Daniel touches on a number of family and friends that he either saw or received correspondence and also those he has not heard from. He tersely mentions that he had not heard from his brothers, Stephen and William. He mentioned he saw John Gates (no relation) who knew and visited his sisters Maggie and Ruth. John Gates may have been in the 121st Infantry Regiment, which at the time of Daniel’s letter writing, was in the general area where Daniel was camped for the winter. [15] He also mentions receiving a letter from uncle (“uncil”) William. It is not apparent from my research who he is referencing in the letter. The only uncle I am able to document for Daniel is Joel’s brother, William Gates Griffis. William Gates Griffis, however, died in December 1860 so it certainly was not William Gates Griffis. He also mentioned that he was considering enlisting again after this three years were completed.

While staying in their winter quarters at Mitchell’s station, James Riley Bowen revealed novel approaches to making ends meet when it came to food. In addition, being stationary during the winter, allowed many soldiers to receive ‘gift packages’ of food from home.

“Some of the boys also ‘borrowed’ a baking pan and waffle iron, so that we had baked puddings and beans with waffles on our bill of fare. … The boxes from home now began to flow into the regimental city, and the boys reveled in the luxuries of home made ‘vittles’.” [16]

Food is a recurrent subject in civil war correspondence from soldiers to their family. Soldier’s complained about the quality of food and were also forthright in describing occasions where they have had a good meal.

“In camp we had Hardtack and frequently soft bread, the latter usually drawn loose in dirty wagons and dumped upon the ground by the indifferent teamsters. We however, usually ‘skinned’ our loaves, that is, cut off the outside, before using.”

“Company cooking in time became unpopular, and was dispensed with, the men greatly preferring to form themselves into squads, or messes, of from four to six, and prepare their own food.” [17]

Daniel was no exception to writing about food in his letter. He was proud to state that they had a cook that knew how to make pies and cakes as best as ‘anyone can get’. For Sunday dinner, he had a king’s meal of hot coffee, bread & butter & cold boiled beans and fried nut cakes. As he stated in the letter, it was hard to believe he could have such a meal since flour was a precious commodity for food preparation during the war. The supply chain to the winter camp provided access to purchasing flour at six cents per pound.

This was certainly better than a meal of Hardtack and coffee. The Union soldier received a variety of edibles. The food issue, or ration, was usually meant to last three days while on active campaign and was based on the general staples of meat and bread.

Meat usually came in the form of salted pork or, on rare occasions, fresh beef. Rations of pork or beef were boiled, broiled or fried over open campfires. Army bread was a flour biscuit called hardtack, re-named “tooth-dullers”, “worm castles”, and “sheet iron crackers” by the soldiers who ate them. Hardtack could be eaten plain though most men preferred to toast them over a fire, crumble them into soups, or crumble and fry them with their pork and bacon fat in a dish called skillygalee. [18]

“Many became expert in the preparation of food, considering our limited material. One way was to fry pork, and then fry the hardtack to a crisp in the grease, which with coffee made a palatable meal. For a change we cut pork into small pieces, then pounded up hard tack, and boiled all together. This dish was called ‘lobloll’.”

“Another was was to put the hardtack into a small, strong bag, and laying it on a stump or stone, pound to a powder with a hatchet; then make into a batter, and bake in pancakes. This with melted sugar was a luxury.”

“There were many other methods for preparing dishes which necessity, the mother of inventions, compelled us to originate. Anything for a change.” [20]

Daniel ended his letter on a good note regarding the joy of having a good meal. We do not know if he received the gloves from his father.

A few months later Daniel and the Dragoons would experience a totally new life as soldiers. On April 6, 1864, General Philip Henry Sheridan assumed command of the cavalry corps, including the Dragoons. Sheridan reached only 5 feet 5 inches tall, a stature that led to the nickname, “Little Phil.” Abraham Lincoln described his appearance in a famous anecdote: “A brown, chunky little chap, with a long body, short legs, not enough neck to hang him, and such long arms that if his ankles itch he can scratch them without stooping.” [21]

Daniel and the First Regiment stayed at Michell’s Station until April 23, 1864 and then briefly moved to Culpepper, Virginia. On May 4th, the Regiment broke camp and joined Ulysses S. Grant’s and General George G. Meade’s 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign against Gen. Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia known as the Wilderness Campaign – a series of battles designed to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia.

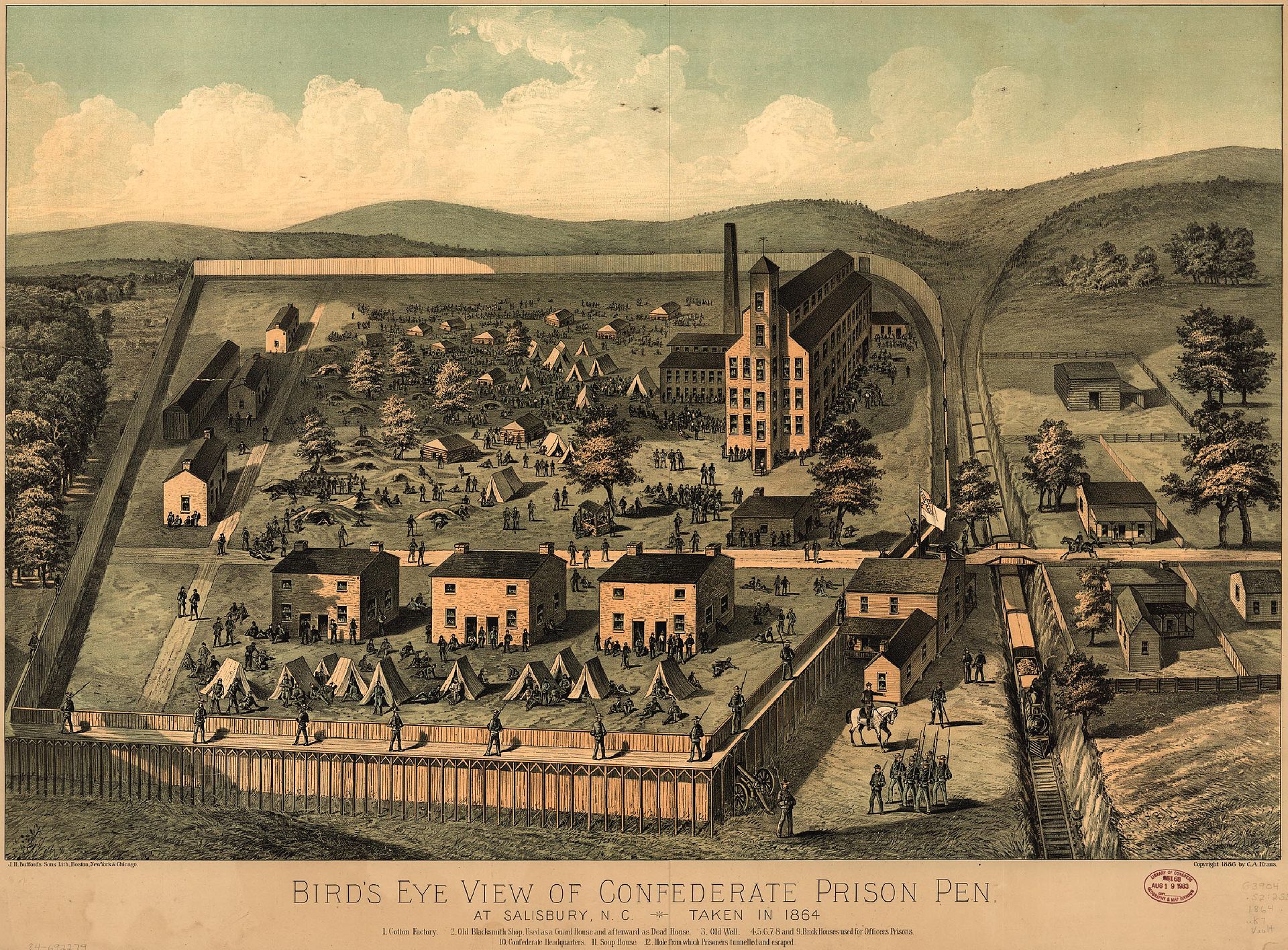

No other letters were saved by his father Joel. Between April and August in 1864, Daniel undoubtably experienced a multitude of mundane and harrowing events as a wagon master supporting the Dragoons in the various raids in northern Virginia. His support ultimately led to his capture by Mosby’s guerrillas and his imprisonment and death in a prison hospital. [23]

Information about Daniel’s capture by Mosby and his imprisonment is found in a separate story.

Sources

[1] American Civil War Soldier Letters,

AmericanCivilWar.com, article source: National Park Service, Gettysburg National Military Park;

Letter Writing in America: Civil War Letters, Smithsonian, National Postal Museum;

Delahanty, Ian, Soldier’s Diaries and Letters, Essential Civil War Curriculum, Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, June 2015

[2] Delahanty, Ian, Soldier’s Diaries and Letters, Essential Civil War Curriculum, Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, June 2015

[3] U.S. Civil War Pension File Claim 231.631, Joel Griffis, 31 May 1877: Joel Griffis claimed that he was economically dependent on Daniel Griffis and unsuccessfully requested a survivor’s pension.

[4] Guttman, Jon, Studebaker Wagon: The Studie That Served on the Front Lines, History.net

[5] James Riley Bowen, Regimental History of the First New York Dragoons: Originally the 130th N. Y. Vol; Infantry; During Three Years of Active Service in the Great Civil War, originally published by author 1900, Reprinted by Forgotten Books, 2012, page 112

[6] Ibid, page 118-119

[7] CPI Inflation calculator, $100 in 1865 is equivalent in purchasing power to about $1,596.50 today, an increase of $1,496.50 over 156 years. The dollar had an average inflation rate of 1.79% per year between 1865 and today, producing a cumulative price increase of 1,496.50%.

[8] U.S. IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1862-1918, Tax Year 1864, Division 9 of Collection District 18, New York state, image 313 of 578; assessed a $10.00 tax on $400.00 assessed value.

[9] In a September 28, 1877 affidavit from Joel Griffis for obtaining a pension from Daniel’s military service, it was also indicated that the 70 dollars “he had earned by his labor just before enlisting and left it with him at time of his departure with said Bristol at Springwater” (September 28, 1877 Affidavit of Joel Griffis, Claim No. 231.631 filed by J. Reck. Ally, Johnstown, NY)

[10] Ether, Eric, Behind the Horsepower of Civil War Armies, History.net

[11] Reeke, John, photographer, Photograph of the siege of Petersburg, April 1865, Library of Congress Civil War Photograph of Petersburg, Va. The first Federal wagon train entering the town

[12] This is a photograph of antique Civil War Gloves leather gauntlet riding calvary uniform dress gloves. Daniel requested half gauntlets made of soft leather but durable to withstand the nature of a wagon master’s duties.

[13] Downtown Gloversville Historic District, Living Spaces; Gloversville, New York, Wikipedia; Gloversville, New York, Wikipedia

[14] Frothingham, Washington, Revised and Edited, History of Fulton County, Syracuse, NY: D. Mason & Co. 1892, Page 156; See also Hosterman, Elizabeth R & Hobbs, Robert B. Leather Gloves: General Information, Letter Circular LC921, U.S. Department of Commerce, national Bureau of Standards, Washington D.C. Oct 11, 1948

[15] New York Civil War Regiment Lists, Volume IV (106th-137th Regiment), page 358 Fold3.com link; 121st New York Infantry Regiment, The Civil War in the East Z: the regiment was probably camped for the winter of 1863-64 in Northern Viginia after the Mine Run Campaign in November and December 1863.

[16] James Riley Bowen, Regimental History of the First New York Dragoons: Originally the 130th N. Y. Vol; Infantry; During Three Years of Active Service in the Great Civil War, originally published by author 1900, Reprinted by Forgotten Books, 2012, page 114

[17] Ibid, Page 37

[18] Author unknown, Soldier’s Food during the Civil War, Civilwar.com; Godoy, Maria, Civil War Soldiers Needed Bravery To Face The Foe, And The Food, National Public Radio; Heichelbech, Rose, What Exactly did Civil War Soldiers Eat?, DustyOldthing.com ; Civil War Food, Civil War Academy online; Colleary, Eric, Civil War Recipe: Hardtack (1861), The American Table June 26, 2013; Rose, Savannah, The Hardtack Challenge: How a Soldier’s Staple Holds Up Today, The Gettysburg Compiler: On the Front Lines of History (online)

[19] Photograph by Matt Rourke, Associated Press, of re-created hardtack made at Bushey Farm ,Gettysburg, PA,

[20] James Riley Bowen, Regimental History of the First New York Dragoons, Page 47

[21] Morris, Roy, Jr. Sheridan: The Life and Wars of General Phil Sheridan. New York: Crown Publishing, 1992. Page 1

[22] Photo by Mathew Brady (1822-1896), 1864 Heritage Auction Gallery: Major General Philip Sheridan and his generals in front of Sheridan’s tent, 1864. Left to right: Henry E. Davies, David McM. Gregg, Sheridan, Wesley Merritt, Alfred Torbert, and James H. Wilson.

[23] The Battle of Berryville Pike, American Civil War