Finding unusual stories embedded in historical documents about distant relatives can be similar to the thrill of catching a good sized trout while fly fishing. Well maybe not entirely but the element of surprise is certainly present. A lot of patience, focused work on a specific goal, and luck sometimes provides for an exciting catch!

Family research usually involves many hours of methodically reviewing digital and original paper sources of documents. A good researcher also checks and cross references enticing discoveries to ensure their accuracy. Oftentimes, this research leads to dead ends or in a positive light, reducing various potential leads for discovering information about a given family member. However, when you discover an unusual ‘fact’ about a relative that has not been documented in the family folklore, it is a moment that can make your day. Then comes the hours of corroborating that great find!

My paternal grandmother’s mother’s family, the Platts, settled in the Cherry Valley, New York area. The family can be traced back to the 1770’s from a John Platts who was born around 1775. John had four sons, George (born 1795), Thomas (b. 1800) John (b. 1804), Peter (b. 1809). My direct line of descent was through the youngest son Peter Platts. Click here for more on tracing James and John Platts from Evelyn Dutcher Griffis.

Many families have ‘colorful’ stories of relatives that are handed down from generation to generation. There are also other situations where stories are hidden or intentionally forgotten or wiped from the oral family history. This may be due to moral judgements about what happened in the past or the collective embarrassment that was felt by a specific generation in the family.

While in the process of documenting additional ancestral information on the oldest son, George Platts, I discovered a series of interesting events about one of his children, James Alfred Platts (b. 1835), and a grandson, John E. Platts (b. 1868). Both father and sons’ time lines are sketchy and perhaps the few facts that are available raise more questions than answers regarding their respective life histories.

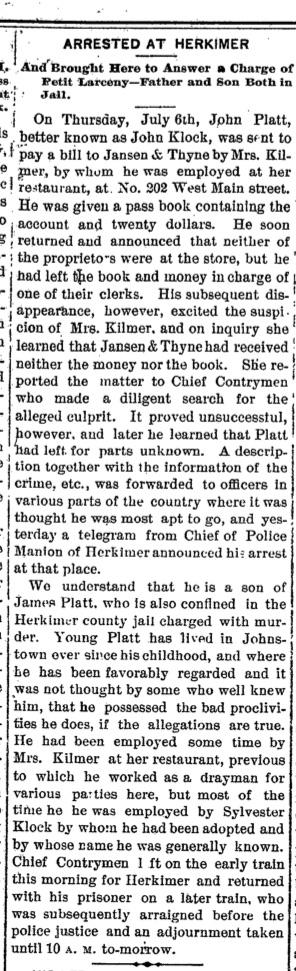

While comparing leads obtained from another researcher on a common relative, I came upon a reference to a newspaper article regarding a murder. I dug a little deeper and searched the on-line archives of the NYS Historic Newspapers and found this story.

It perhaps is unusual to discover criminal activity of a relative, let alone reveal an intergenerational tradition of criminal activity. Both father and son were in jail for murder and petty larceny respectively. This newspaper article definitely got my attention. I started to dig for additional information to explain how and why James and John Platts got to this point in their lives.

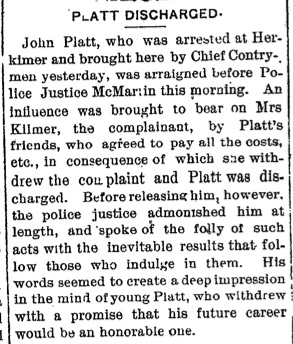

It appeared that the following day, the petty larceny charges were dropped by the complainant. John Platts (Klock) promised that ‘his future career would be an honorable one”.

Meanwhile Father is in Jail on Murder Charges

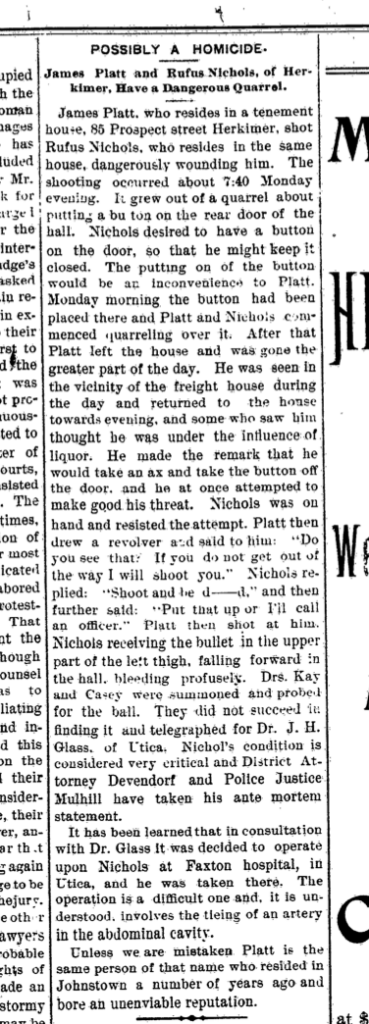

Meanwhile, John’s biological father, James Alfred Platts, languished in the county jail on murder charges. As indicated in the newspaper article below, James Platts shot Rufus Nichols over a quarrel about putting a “button” or lock on a back door of a tenement house where both men lived. The newspaper article indicates that James Alfred Platts’ “unenviable” reputation preceded this incident when he lived in Johnston. In a June 17, 1893 newspaper article (page 4) in The Plattsburgh Republican, while referencing the shooting, the article indicates “Platt (sic) is a hard one and is in jail now for the third time, once before for stealing and twice for drunkenness”.

The shooting occurred on a Monday evening. The Platts and Nichols’ families lived in the house and previous to the shooting there had been frequent quarrels over the button on the inside of the back door. Platts complained that when he went out the back door Nichols would fasten it compelling them to go around to the front door to get into the house. That Saturday night Platts, with an axe, started to take the button off when Nichols came out to prevent it. There was a war of words and finally Platts drew his revolver and fired. Nichols struck the gun down and the ball entered the left leg below the hip. Platts ran and hid under a barn where he was soon found by chief Manion. Nichols was attended by Dr. Kay and Dr. Casey. The day following he was taken to Utica hospital were an operation was performed, but gangrene set in and he died the following Wednesday.

The outcome of the shooting was grim and takes a turn worse for Platts when Rufus Nichols died from the effects of surgery to remove the bullet in his leg and infection.

James Platts remained in jail through the summer and fall and faced the inevitable in his trial in December of 1893.

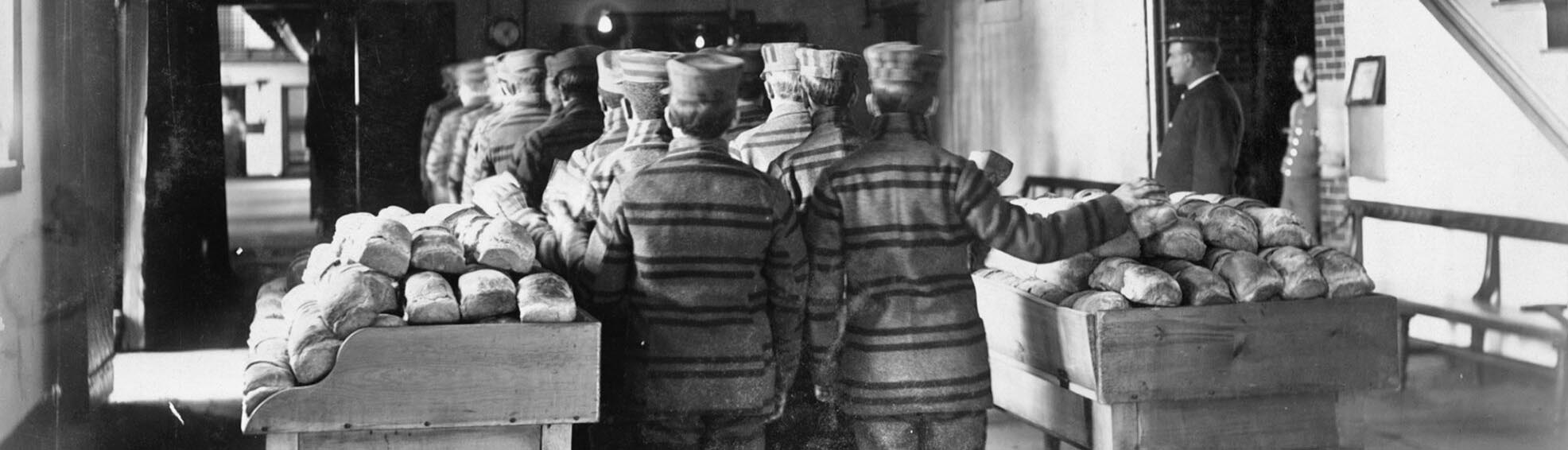

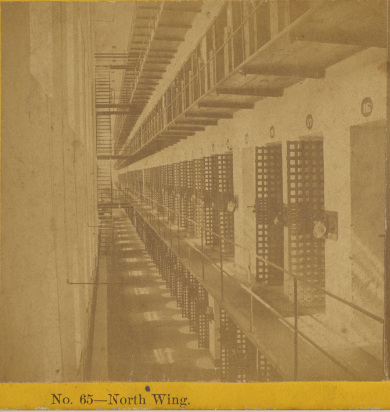

James Platts served 10 years of his sentence at Auburn Prison. Auburn Prison was in the late 1800’s a maximum security prison that had a tradition of enforcing strict draconian rules for prisoners. He was released, based on good behavior, at the age of 69. I have provided more detail on James Platts’ incarceration on a separate page.

Read more about James A. Platts and Auburn Prison ,

Photo: Christopher G. Gibbard, No. 65 – North Wing Auburn Prison, 1870, J. Paul Getty Museum

Old Habits Continue with John Klock

Despite young John Klock’s promise to lead an honorable life, two years later he again is found in the cross hairs of the law. John stole carpenter tools and sold them to different parties, resulting in a five month sentence in prison.

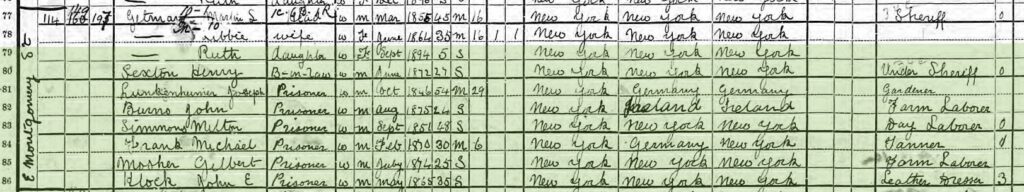

Five years later, John is again caught stealing. This time he stole a bicycle and was charged for grand larceny in the second degree without bail. While incarcerated pending his trial, he changed his plea from not guilty to guilty of petit larceny and was sentenced to four months imprisonment in the county jail and to pay a $40.00 fine. Not only is this incident captured in the local newspapers but his incarceration before sentencing is memorialized in the 1900 census.

Based on the 1900 Federal Census, he is listed as John E Klock, age 35, as a leather dresser and one of six prisoners in the household of Martin Getman, Sheriff of the Fulton County Jail. As an unsentenced defendant in custody of the courts, the census taker Edward Hodges, dutifully captured John Klock’s ‘residence on June 6, 1900. It is ironic that both father and son were once again incarcerated at the same time in 1900.

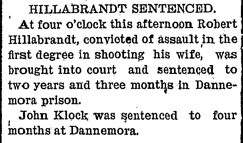

Sixteen days after the census was taken, John was sentenced to four months at the Dannemora Prison, Dannemora, NY.

There is no mention of John when his biological father’s passed away in February, 1909. When his adopted father passed, he was not listed as a son in his obituary [1].

The Son: John E. Platts

Who was John E. Platts or John E. Klock? He was born in May 1868. It appears that his aunt Margaret Platts and his Uncle Sylvester Klock adopted him or took him into their household at an early age. Throughout his life, he used both the Platts and Klock surnames. The circumstances behind his adoption or moving into the Klock family are not known.

John Platts is found in the 1870 U.S. census [2], residing in the town of Minden, Montgomery County, New York. At that time, two year old young John was living in a household that included his grandfather George and grandmother Margaret Platts. Both grandparents were 70 years old. His grandfather listed his occupation as a farmer. The head of the household was Sylvester Klock, a 35 year old farmer who married George’s daughter, Margaret, who was one year younger than her husband. Margaret and Sylvester had a daughter, Nancy, who was eleven years old.

Five years later, the family witnessed some changes and transitions. As documented in the 1875 New York census [3] , it appears that John E. Platts has been adopted by his uncle Sylvester and aunt Margaret. In the five year time span, the Klocks moved 15 miles eastward in the Johnstown, New York area. Sylvestor Klock identified himself as a laborer. Seven year old John is now listed as John Kloch. Nancy Kloch, now 17 years old, is still living at home. The grandmother, Margaret, appears to have passed and the patriarch of the family, George, has moved west, almost 200 miles, to live with his eldest son Henry Platts in Bergen, New York. In 1800, young John is still residing with his step family as a student at the age of 12 [4]. In his early 20’s, John resided in Johnstown as a brickmaker in 1890 and 1891 [5]. Two years later John officially starts his career as a petty thief.

There are no records of his whereabouts beyond this point in time in 1900 when he was incarcerated in in the Dannemora Prison. While the name ‘John Klock’ was not unique as found in the U.S. Census, there is a John Klock identified in the 1920 in Rochester, as an unemployed laborer in the role of a servant in a household. The individual has the same birth year as John Klock and he and his parents were born in New York state. It is not certain that his is the same John Klock. [6]

The Father: James Alfred Platts

James Alfred Platts was born in May 1835 in Minden, New York. At the age of 15, he was attending school in Minden [7]. He was living with his parents George and Margaret and his four brothers and sisters: Lucinda (24), Henry (22), Abraham (18), and Margarett (13). In 1860, there is a young James Platts that is living with a family that has Loomis Brown, a carpenter, as head of household. [8]

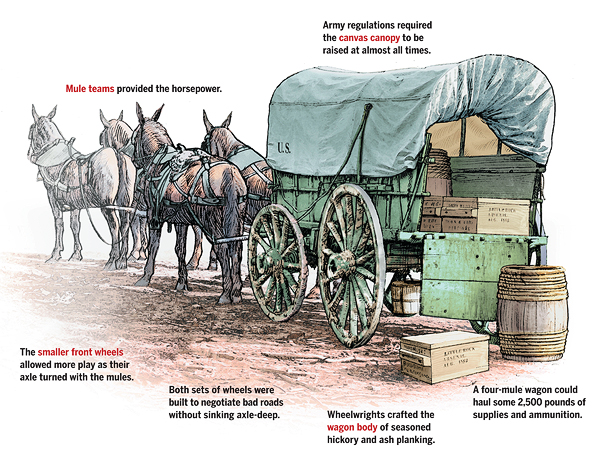

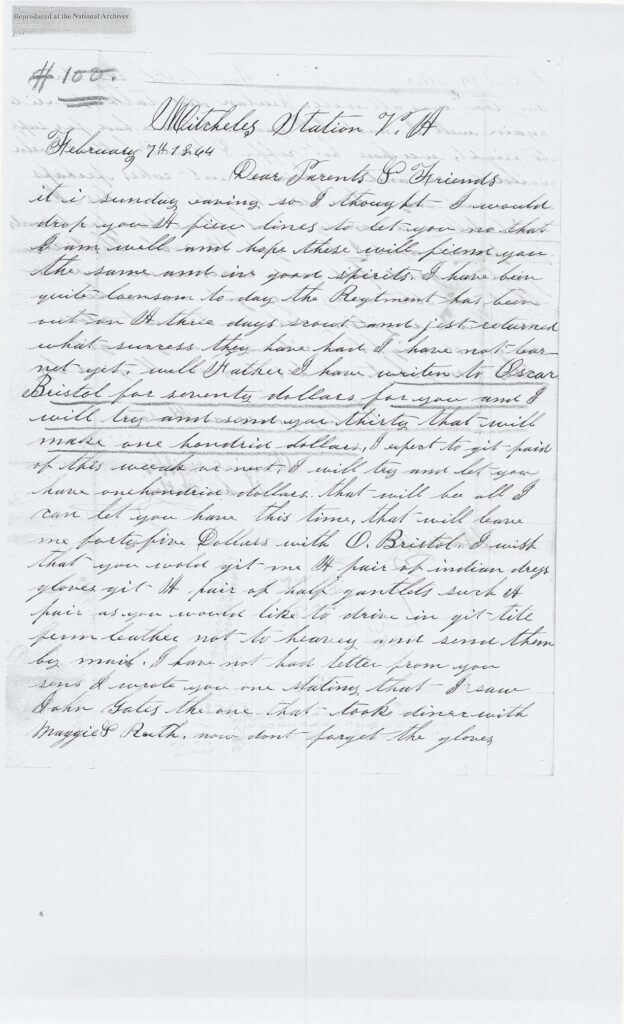

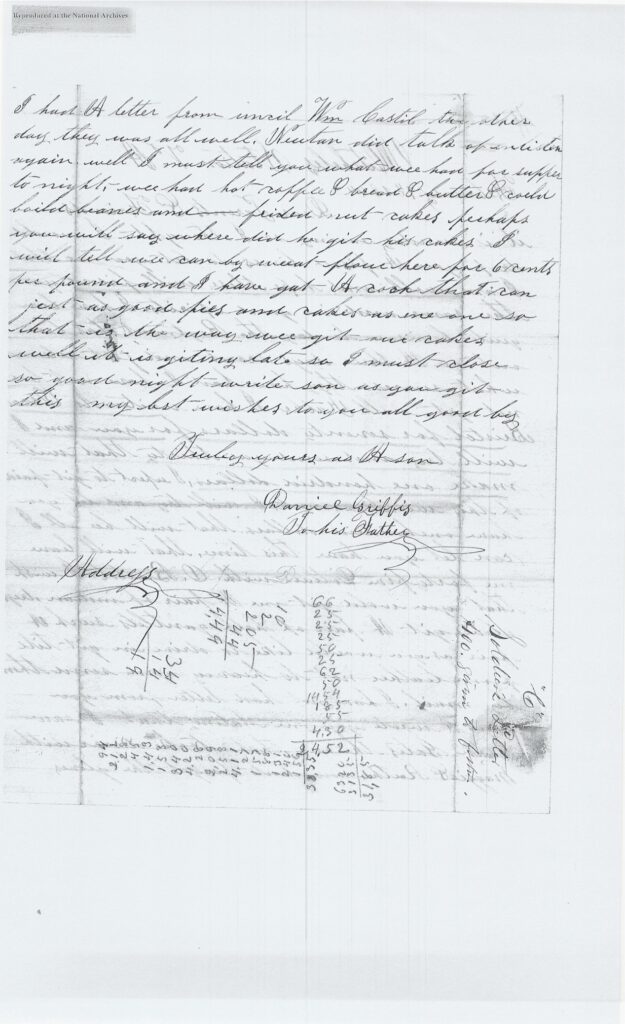

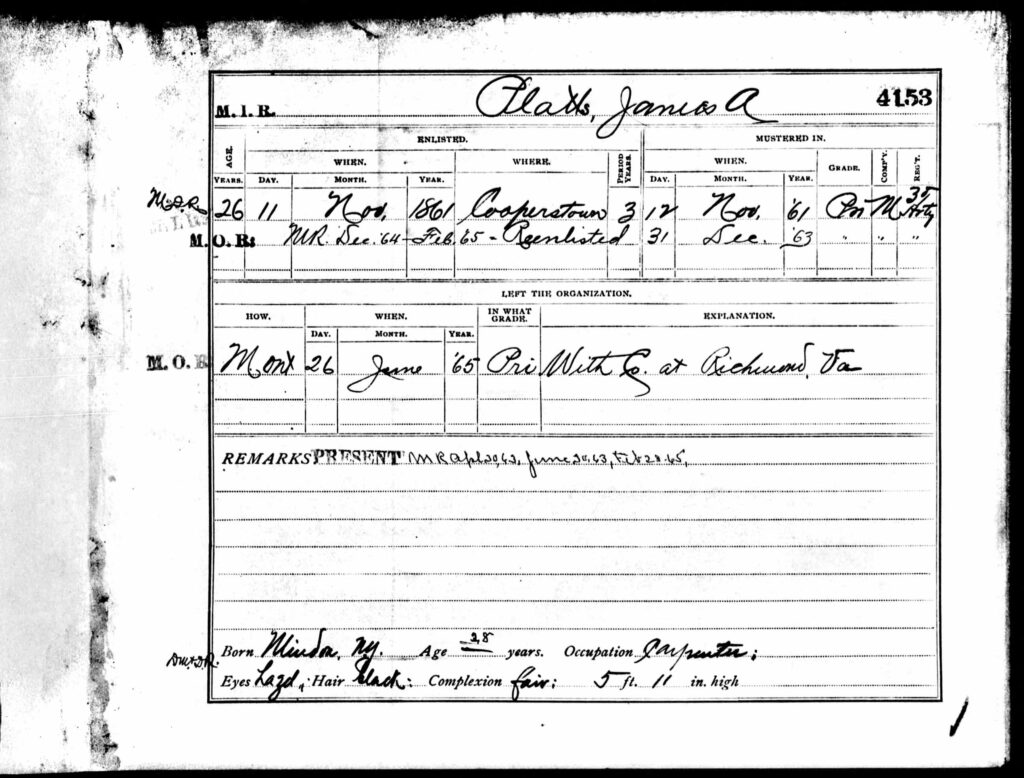

He enlisted in the Union Army November 11, 1861 in Cooperstown, NY and mustered out the next day. Documents indicated he is listed as a carpenter in one source [9] and as a teacher in another source [10]. He had hazel eyes, black hair, fair complexion, and was 5 foot eleven inches tall. He mustered out of the service June 26, 1865 in Richmond, VA after two tours of duty. He was part of Battery M of the 3rd Regiment of the New York Light Artillery [10] [11]. The artillery unit experienced a number of major engagements during the war [12] and [13].

After four years of military service in the Civil War, James returned home in 1865 and started a family at the age of 30. It appears he is listed as single, living with his father and mother along with his sister Lucinda and her 2 and a half year old son Harvey Ruder on June 10, 1865 [14] but he was not discharged from the military until June 26, 1865. I suspect his father reported James as living with them despite being in Richard, VA before he was discharged. Although there are no available records of a marriage in 1865, in the next 10 years he has four children: Minnie Agnes Platts (1866), James E. Platts (1868), Olive (1870), Mary (1872) and James Henry (1875).

In June of 1875, 40 year old James is listed in the 1875 New York Census with his wife Mary, who is ten years younger. But a more telling fact is the absence of John E. Platts in the household. [15] At the age of 2, a decision was made to have James Alfred Platt’s sister assume custody of the child. It is not known what precipitated the move. In 1800, the family sans young John E. was living in Amsterdam, NY. James Alfred listed his occupation as a carpenter but it was reported that he was unemployed four of the first six months of the calendar year. [16]

In January, 1883, James and his wife Mary lost their 13 year old daughter. It is not known what was her cause of death. It certainly must have had a traumatic impact on the family. A year later, his sister who adopted young John E Platts, passed away at the age of 41.

Then a puzzling fact appears in 1884. A New York marriage index indicates that a James A. Platts from Amsterdam was married [17]. Does this reflect our James Alfred Platts who lived in Amsterdam? Does it indicate that he married his common law wife Margaret? Does it indicate he remarried?

At this stage in his life, he begins to witness frequent changes in his residence. Perhaps challenges in his ability to make ends meet are increasing. In 1887 and part of 1888, James A. Platts is living at the Commercial Hotel in Amsterdam for two years. His occupation is listed as a carpenter. We do not know if his family is living with him at the Commercial hotel or if he is living alone. In 1888 and 1889, Platts moved to a boarding house located at 75 Spring Street, Amsterdam, NY. [18]

At 55 years of age, life must have been getting difficult for James Platts. On July 26, 1890, he filed for an invalid military pension [19]. In 1890, James Platts is listed in the Gloverville, NY directory. [20] Sometime in between 1890 and early 1892, he and Margaret also moved to Herkimer, NY [21]. It is not known if the couple moved into the tenement house where Rufus Nichols lived at the time. The next stage of his life was overtaken with the shooting of Rufus Nichols. James Platts does not surface until 1904 after his 10 years in prison.

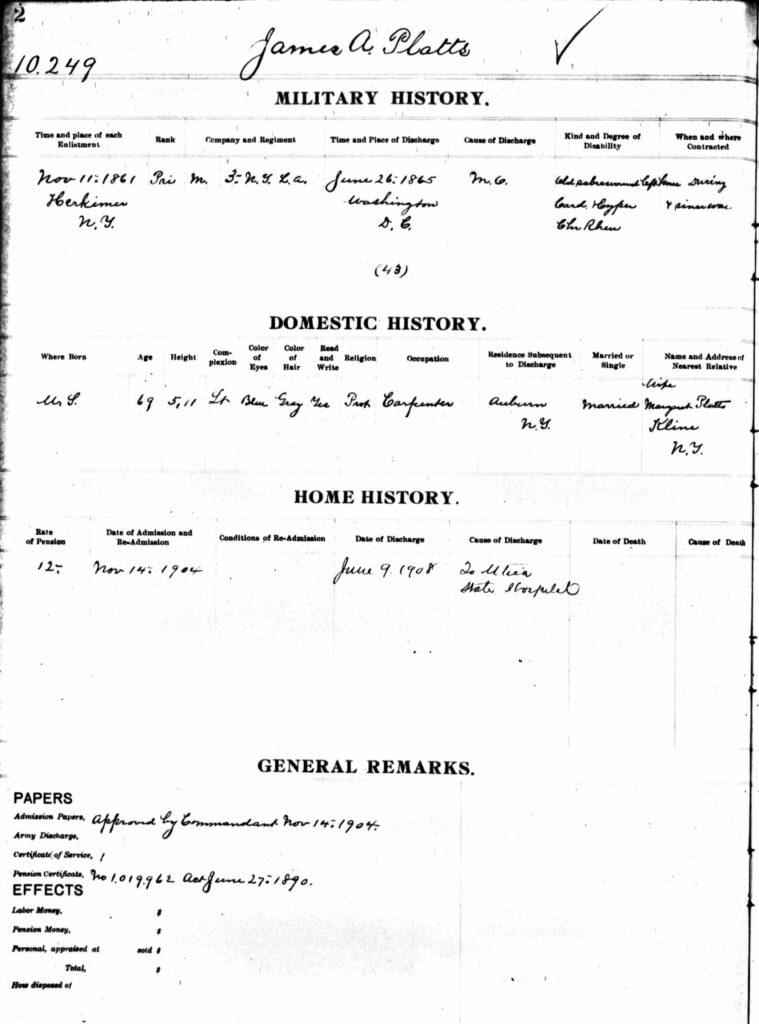

After James was released from prison in July 1900, he was admitted to the New York State Soldier’s and Sailor’s Home located in Bath, NY on November 14, 1904 and was discharged on June , 1908 [22] James Platt was captured in the 1905 New York Census, age 70, carpenter, when residing in the New York State Soldiers and Sailors home. At the time he was admitted to this institution, he had been a resident of Amsterdam, NY. [23]

Ten months after his discharge, James Alfred Platts passed away at the age of 73 in March, 1909 in Florida, NY. The date of death is inferred from a widow’s petition for letters of administration on 16 March 1909 in Amsterdam, NY. [24] Margaret Platts, widow of James A. Platts, named administratrix of James A. Platts on March 16, 1909, who died intestate. [25]

Sources

Featured photograph: Auburn Prison Bread Line, Cayuga Museum of History and Art

[1] Johnstown Daily Republican, July 11 ,1911, page 2

[2] 1870 U.S. Federal Census, Minden District 1 and 2, Montgomery County, NY, Page 38, Lines 34-39, August 16, 1870

[3] 1875 New York State Census Johnstown, Fulton County, NY, Page 7, Lines 18-21, June 1875

[4] 1880 U.S. Federal Census, Johnstown, Fulton County, NY, Page 40, Lines 22-25, June 19, 1880

[5] Gloversville, New York Directories, 1890-93, (Database online), Provo, UT, Ancestry.com

[6] 1920 U.S. Federal Census Rochester Ward 5, District 68, Monroe County, NY, Page 2, Line 51

[7] 1850 U.S. Federal Census, Minden, Montgomery County, NY, Page 48, Lines 11-17, June 5, 1850

[8] It is not certain that this is James A. Platts. His age is listed as 20 but he would have been 25 in 1860. However, the following year James enlists in the Union Army in Cooperstown. 1860 U.S. Federal Census, Cooperstown, Otsego County, NY, Page 2, 32-35, June 27, 1860

[9] New York, Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900, 3rd Artillery (Heavy), Record 4153, (Online Record, Provo UT, Ancestry.com)

[10] This record indicated James Platts enlisted at the age of 24, born in Montgomery Count, was single, a teacher. He enlisted in the 47th Volunteers in October 1861 as a Private and his first term of enlistment was for 39 months. He reenlisted and was still a Private as of June 1965. Source: Return of Officers and Enlisted Men who are Now in the Military or Naval Service, Vol 2: Volunteers Now in Service, Kings – Orleans Counties; New York, U.S., Registers of Officers and Enlisted Men Mustered into Federal Service, 1861-1865 (On Line Records, Image 256, Provo, UT: Ancestry.com)

[11] Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1896, Registers of the Third and Fourth Artillery in the War of the Rebellion. Transmitted to the Legislature January 19, Albany, NY: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co, 1897, 1897.Page 408

[12] Battery M was organized as Company I of the 76th N. Y. infantry and with two other companies was assigned to the regiment on Jan. 24, 1862. It was mustered into the U. S. service at Albany, Jan. 18, 1862, for a three years’ term and joined the regiment in North Carolina. It served near New Berne, N. C, until Oct., 1863, and was then ordered to Fortress Monroe. In Jan., 1864, it was assigned to the 18th corps and to the 1st division of that corps in March, being transferred to the 3d division the following May. In June it became a part of the artillery brigade, 18th corps, and in Dec, 1864, of the artillery brigade, 24th corps. It took part in the operations before Petersburg, joined in the final assault, and was mustered out of the service at Richmond, June 26, 1865.

[13] For information on the New York 3rd Regiment Light Artillery, see Civil War of the East Third New York Battery; the Civil War Index; 3rd Artillery Regiment (Light), NY Volunteers

Civil War Newspaper Clippings;

[14] 1865 New York Census, Minden, Montgomery County, Page 80, Line 24 (On line Record, Provo, UT, Ancestry.com)

[15] 1875 New York State Census, Glen, Montgomery County, Page 9, Lines 38-43 June 26, 1875 (On Line Record, Provo, UT, Ancestry.com)

[16] 1880 U.S. Federal Census, Amsterdam, Montgomery County, NY, Page 11, Lines 22-27

[17] New York State, Marriage Index, 1881-167, New York State Department of Health, Albany, NY, 1884, page 331, certificate 10898

[18] Amsterdam, New York Directories, 1887-1890, (Online data, Provo Utah, Ancestry.com); Amsterdam, New York, City Directory, 1887

[19] July 26, 1890 Organization Index to Pension Files of Veterans Who Served Between 1861 and 1890.

[20] Gloversville, New York, City Directory, 1890, James A Platts, carpenter living at 13 School, Gloversville, NY

[21]February 16, 1892,New York State Census, 1892, Herkimer, Herkimer County, NY, Page 6

[22] U.S. National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, 1836-1838, Bath, 249 on film strip roll. The original hospital was established in 1877 by the Grand Army of the Republic. The property was transferred to the State in 1878, greatly expanded, and rededicated in 1879 as the New York State Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home, Bath. It initially housed disabled New York veterans of the Civil War, but, as the men aged, it became largely a geriatric facility.

1905 • Bath, Steuben, New York, USA

[23] New York State Census, 1905, New York State Archives, Albany, NY; State Population Census Schedules, Election District A.D. 01 Bath, Steuben County, Page 5, Line 4

[24] New York, Wills, and Probated Records, 1659-1999, Record of Wills and Administration, 1787-1922; New York Surrogate’s Court (Montgomery Count, Probate Place, Montgomery NY, Page 582

[25] New York, Wills, and Probated Records, 1659-1999, Letter, Admn, Vol 0009-0011, 1903-1919, Page 45; Margaret Platts, widow of James A. Platts, also petitioned the Surrogate Court in Amsterdam, NY for letters of administration.New York, Wills, and Probated Records, 1659-1999, Orders of Admn, Vol 002, 1896-1909, Page 583