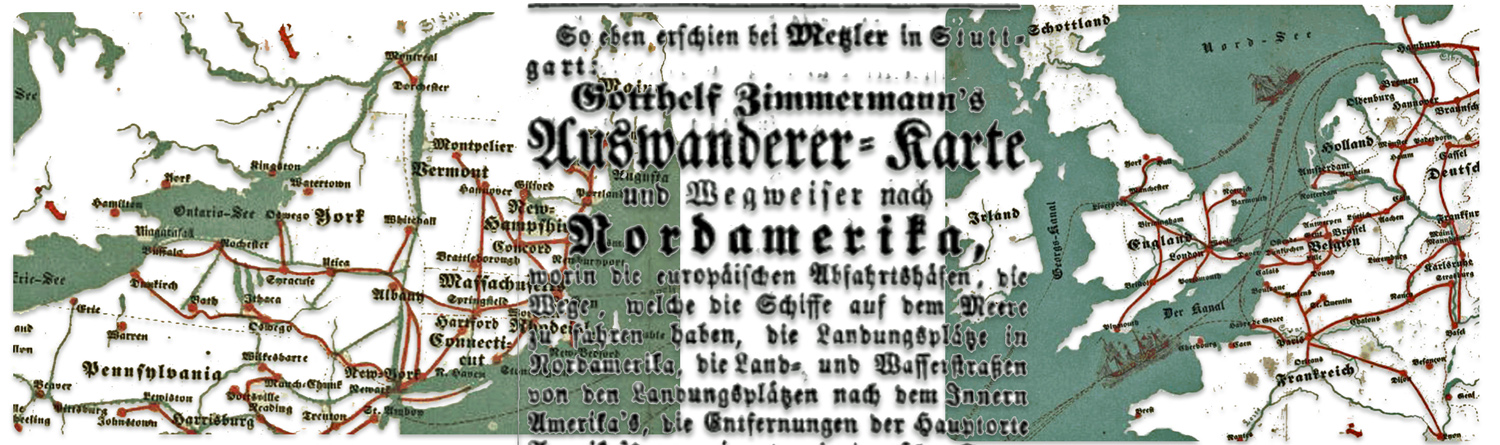

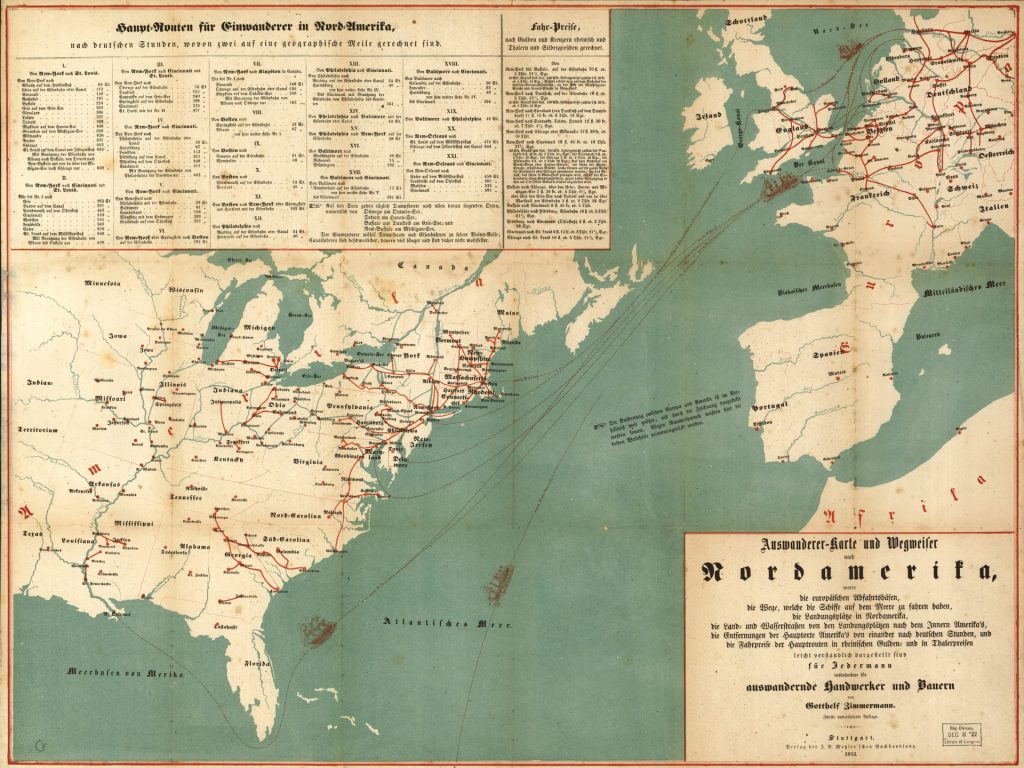

There was a point in my long and focused research to document the immigration of our German ancestors that I came upon a map in my research. The map is 49 x 65 centimeters or about 19.3 x 25.5 inches in size.

The map was created in the early 1850s and, it contained a wealth of information about major German immigration routes to America. The map documented inland European travel routes to specific intercontinental ports of departure to the United States. The map also documented various inland routes from American ports to various cities in America. The map also provided information on the main routes for immigrants traveling in North America, measured in miles and the estimated time and cost of travel.

The map graphically portrayed the German immigrant experience in the mid 1800s in one page. It captured the gist of what I had documented through many hours of research. It was one of those moments that you look at the map and say to yourself, “Why didn’t I find this map before I started this research journey?“. While my research substantiated and explained in more detail what was depicted in the map, having the map at the beginning of the research process would have provided a great starting point.

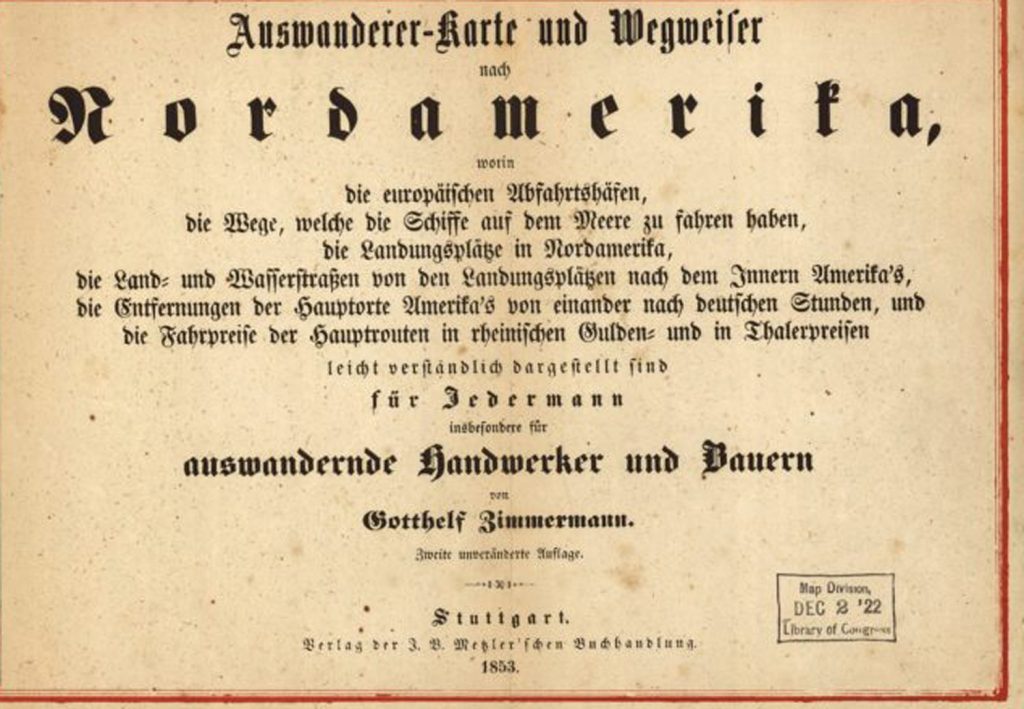

The map is the “Auswanderer-Karte und Wegweiser nach Nordamerika” (Emigrant Map and Guide to North America), published in Stuttgart in 1852-1853 by Gotthelf Zimmermann. [1]

Map One: Zimmermann’s Emigrant Map & Guide to North America

☞ See also a 1970 x 1478 pixel sized version of the map. ☜

The Significance of Auswandererkarten

Auswandererkarten, or German emigration maps in the mid 1800s offered detailed information about migrating to the United States. Special maps like the 1853 “Emigrant Map and Guide to North America” were published in Germany to aid emigrants, providing detailed travel information on routes, ports, and settlements in the United States.

Emigration maps were published as separate items for guidance, advertised in German newspapers and were published as part of emigrant guides and handbooks. These maps, together with the weekly posting of departing ship schedules in German newspapers satisfied the needs of a growing market of German emigrants heading to the United States in the 1830s through 1850s.

The emigration maps provide a wealth of information, graphically depicting the predominate immigration routes in the mid 1800s. The routes are based on the transportation networks (e.g. road, canal, and rail) and major ports of departure and ports of entry that existed at the time. They capture an historical and visual snapshot of the development of the transcontinental transportation network that Germans utilized in the mid 1800s to immigrate to the United States. [2]

Here are some key details and general observations about these emigration maps :

- They provided information for Germans planning to emigrate to the United States and other parts of North America, showing specific routes, travel times, ports of arrival, and potential settlement locations.

- The maps were at times part of written travel guides with practical advice for emigrants on the journey, arrival ports, transportation options, costs, and life in America.

- They were published by book publishers, map makers, emigration societies and travel agencies catering to the large numbers of Germans emigrating in the nineteenth century.

- By depicting the routes, travel information and settlement locations, these maps provide a reflection of where Germans migrated to specific areas in North America.

- From an historical perspective, these maps reflected the current outlines of the transportation infrastructure in Europe and the United States.

- The maps provide a prescient graphic outline of the immigration patterns of where Germans eventually settled in the United States.

The Relationship of Emigrant Maps and Migration Patterns

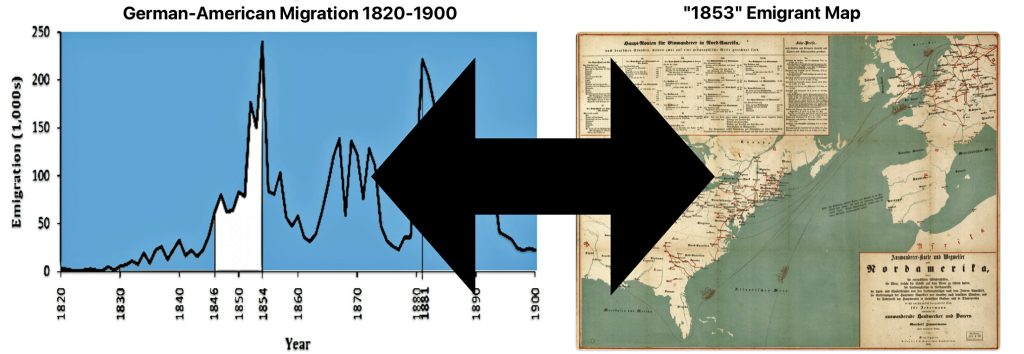

These emigration maps did not cause massive upswings of Germans immigrating to the United States. Nor did they have a significant influence on the migration and settlement patterns of German immigrants in America. [3] This line of reasoning is akin to saying that since fireman are always around fires, they cause fires. To mix metaphors, it is a bit of the tail wagging the dog.

In a book, ‘A History of American in 100 Maps’, Susan Schulten chose this map as one of the hundrend influential maps of the United States. “The maps in this volume were made in vastly different contexts. Yet when considered together, they underscore the persuasive power of cartography.” [4]

Schulten points out that richly colored map was part of the large corpus of immigrant literature associated with the immigrant expansion of the United States in the mid 1800s.

“At first glance, it shows prospective emigrants a range of destinations that awaited them … . But a closer look shows not only patterns of immigration but also the more fundamental dynamics that contributed to the Civil War.”

“… (W)hile this map was designed for one purpose, it inadvertently reveals a much larger set of forces that increasingly differentiated the slave-based agricultural economy of the South from the free-market wage economy in the North. And by guiding immigrants to the latter, the map actually helps us understand the way that immigration was both a cause and consequence of that growing regional distinction, which ultimately led to the sectional crisis.” [5]

I believe the above quote correctly points to ‘a larger set of forces‘ that influenced German migration in the antebellum United States. The map also reflects the imbalance of the growth of the transportation infrastructure between the northern and southern states in the mid 1800s.

Whether the map and other emigrant maps played an influential role in guiding immigrants to the north is subject to debate. The above quote does not imply this map or German immigrants had a fundamental role in the emerging differences between the north and the south. Schulten’s observations point to the map’s reflection of the current state of affairs in the mid 1800s.

Based on various historical studies of immigrant letters and chain migration, maps and other forms of publications did not necessarily play an active, casual, or dominant role in directing immigrants to particular areas of the United States or actively guide or steer immigrants to the northeast and mid-west regions of the antebellum period. Maps of the 1850s were the reflection of the regionalized industrial growth in the United States. [6]

Whether one does immigration history by the numbers or by the letters, the results show a striking congruence. The decision to emigrate was very much a bottom-up decision. Private sources of information, above all immigrant letters, were much more influential than any public sources, be they guidebooks or state immigration agencies, in determining immigrants’ destinations. [7]

While opposition to slavery was widespread among nineteenth century German immigrants and many were active abolitionists, their attitudes were complex and varied by individual, class and circumstance. Views on the issue of slavery were not a major cause of migratory patterns. [8]

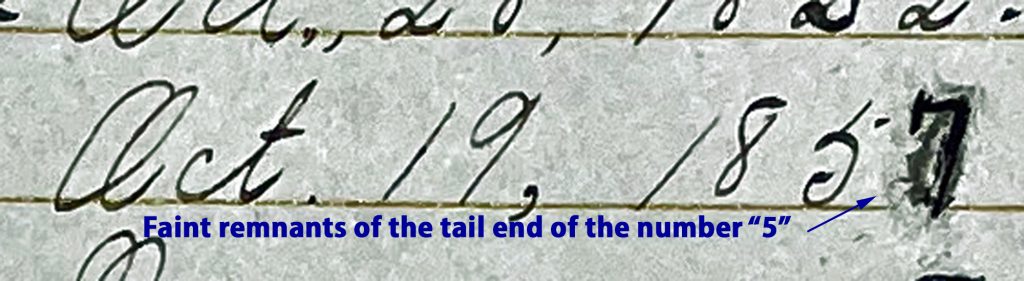

Illustration One: A Spurious Correlation: Emigration Maps and German Immigration Trends and Migratory Patterns

The views or conclusions about the influence of maps and publications on immigrant patterns are examples of what I believe to be a spurious correlation between the existence of emigration maps and migration trends and patterns. In this instance, a spurious correlation gives the false appearance of a causal relationship between two variables (e.g. maps and German emigration), when in reality the association is due to both variables being influenced by a number of other factors (e.g. push and pull migration factors, chain migration patterns, transportation infrastructure development in Europe and America, the refinement of packet ships and their schedules, etc). Identifying spurious correlations requires a careful analysis of the evidence and teasing out the effects of potential confounding variables.

Emigrant maps, in general, were specific tools to facilitate an emigrant’s journey. They did not necessarily promote or determine an emigrant’s path. However, like maps in the twentieth century, I would imagine maps in the mid 1800s in Germany may have sparked ideas of adventure or bolster decisions to make decisive moves to America in the minds of some. For the most part, they were an aid in helping immigrants that had already made their minds up in emigrating to a specific area or region of the United States.

In a society dominated by small towns and villages, horizons were narrow, local sentiments strong and information passed between generations and those you knew. The decisions made by German emigrants were not made in a vacuum. Local and regional socio-economic and political factors created a set of unique ‘push’ factors for them to consider emigrating from their homeland.

Their subsequent journey to America was also influenced by information they may have garnered from local community members who had descendants who migrated to America in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s. Travel agents and brokers, and German publications, such as maps, also provided to some degree information that may have facilitated their decisions to emigrate and guided their specific paths to their destinations..

As stated in prior stories, the areas in Germany where our relatives migrated from had a long tradition of migrating to America. Their specific route getting to America was different from the Baden emigrants in the 1700s and early 1800s. However, there may have been a strong likelihood that they followed the guidance from past generations from their local communities to settle in places that prior generations had settled or use those places as starting points to go further. Even without specific contacts, they may had at least a general idea of settling in the ‘Palatine area’ along the Mohawk River in New York state where past generations originally settled.

Regardless of the relative influence that emigrant maps may have had on emigration patterns, Zimmerman’s emigrant map provides an amazing, graphic snapshot of possible German migratory patterns in the mid 1800s. It is a great 1850s version of the contemporary travel map of the twentieth century.

“(O)ld maps are valuable as both records and agents of history. Across five centuries, artifacts such as these have guided exploration, conquest, and settlement but also politics, commerce, science, medicine, education, bureaucracy, reform, and entertainment. Whether made for military strategy or moral reform, to encourage settlement or investigate disease, maps both reflect and mediate change. They tell us what people knew, what they thought they knew, what they hoped for, and what they feared. They invest information with meaning by translating it into visual form, thereby reflecting decisions about how the world ought to be seen. They capture the irreducible complexity and contingency of the past. Above all, they remind us that the past is not just a chronological story, but a spatial one as well.” [9]

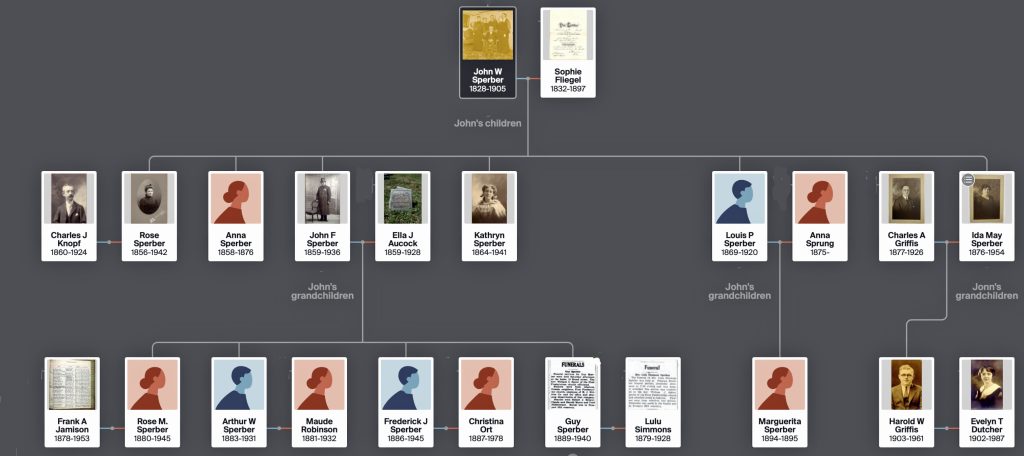

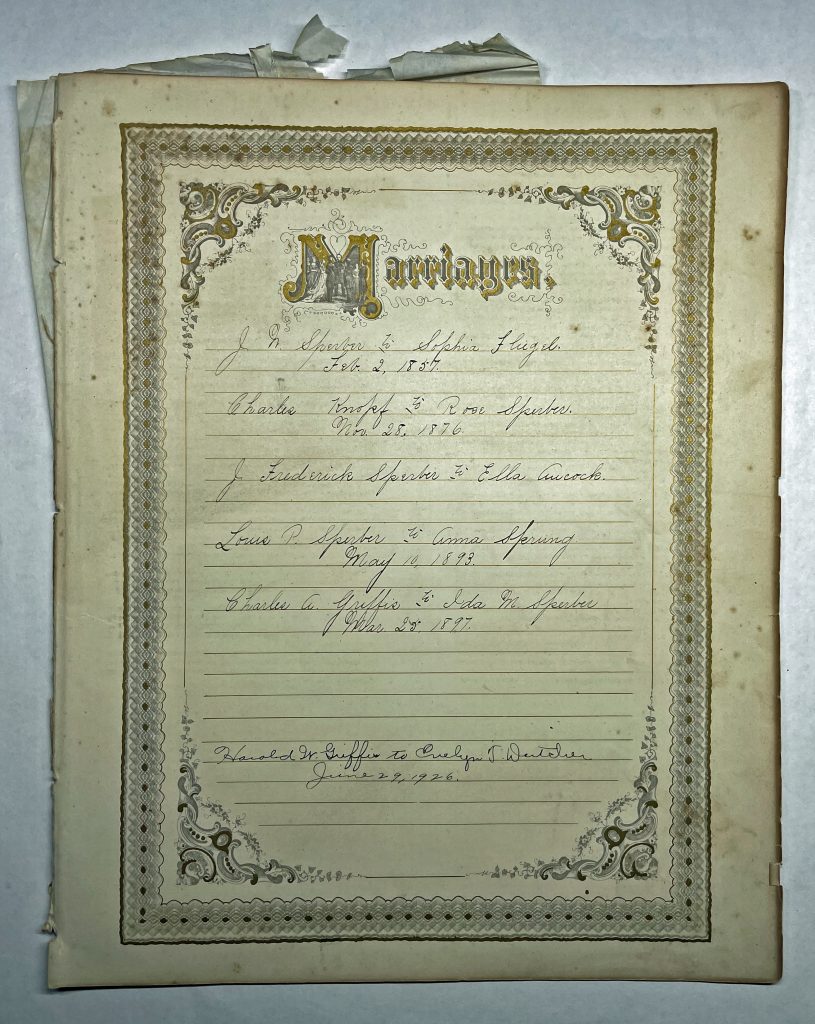

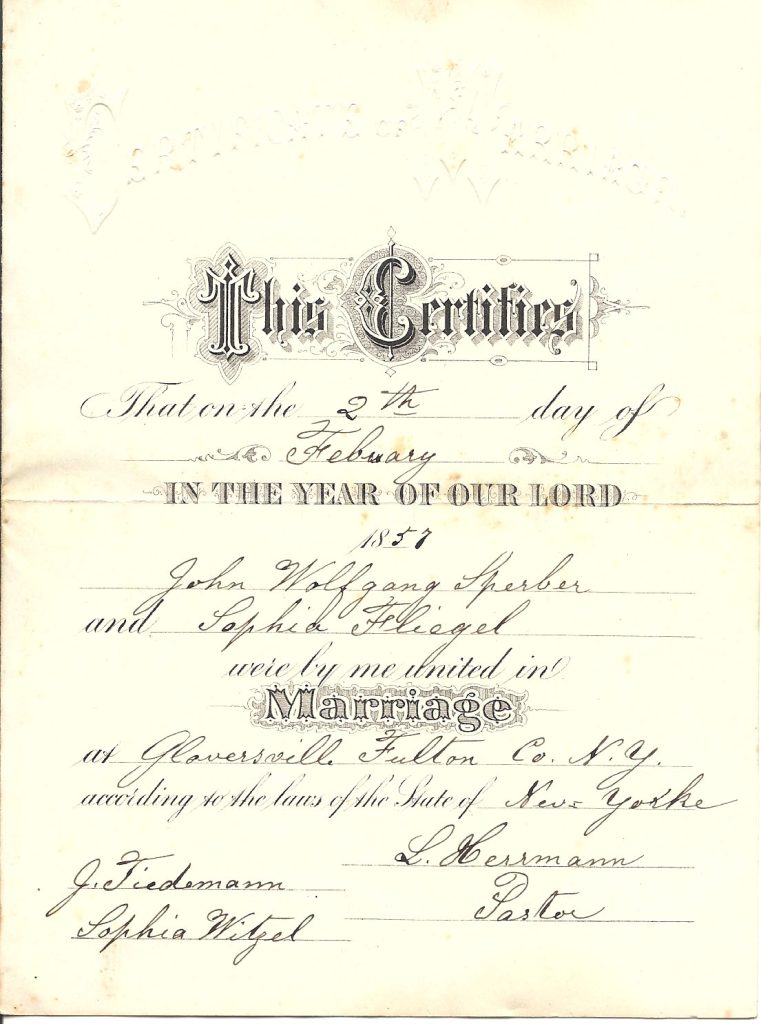

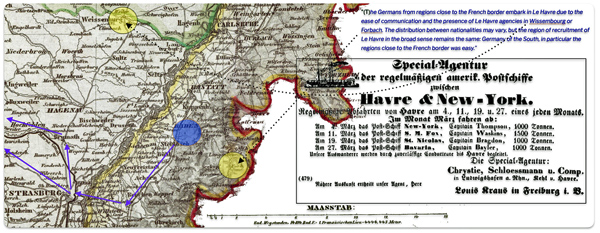

Advertisements for the Auswanderer-Karte und Wegweiser nach Nordamerika

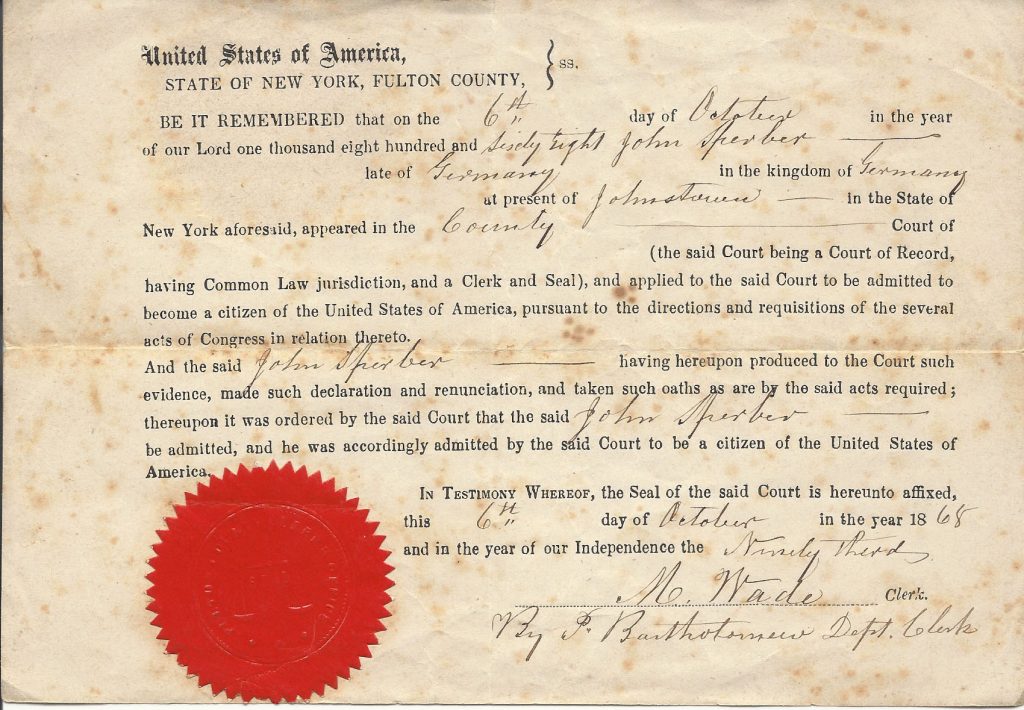

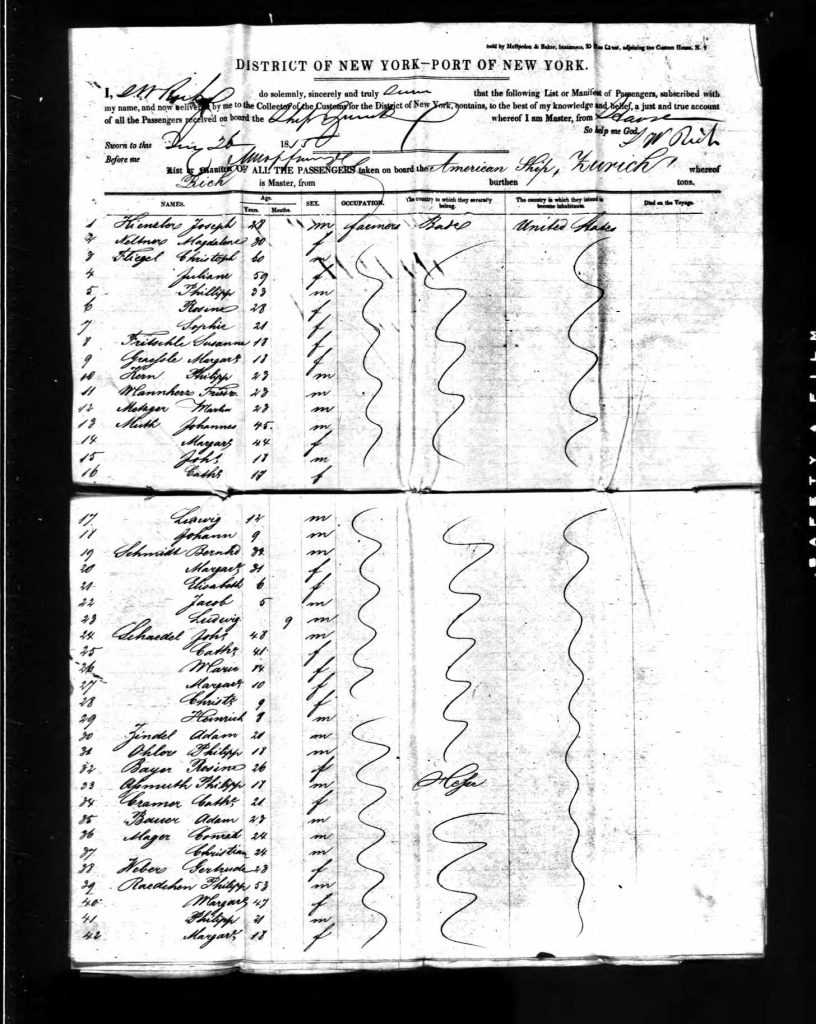

The “Auswanderer-Karte und Wegweiser nach Nordamerika” (Emigrant Map and Guide to North America) was published in Stuttgart, which was located in the Kingdom of Württemberg, around 1852. This is around the time that ancestors of the Griffis family emigrated from Baden. This is the year that John Speber departed from Le Havre to New York. It is five years after Catherine Fliegel departed from Le Havre for the port of New York city. It is three years before the remainder of the Fliegel family embarked from Le Havre to New York City.

The map was published by J.B. Metzler. The J.B. Metzler publishing house was one of he oldest publishing houses in Gemany. It was founded in Stuttgart in 1682 by August Metzler. [10] Metzler advertised the emigration map in German papers and offered special rates for bulk orders by emigration agents. [11]

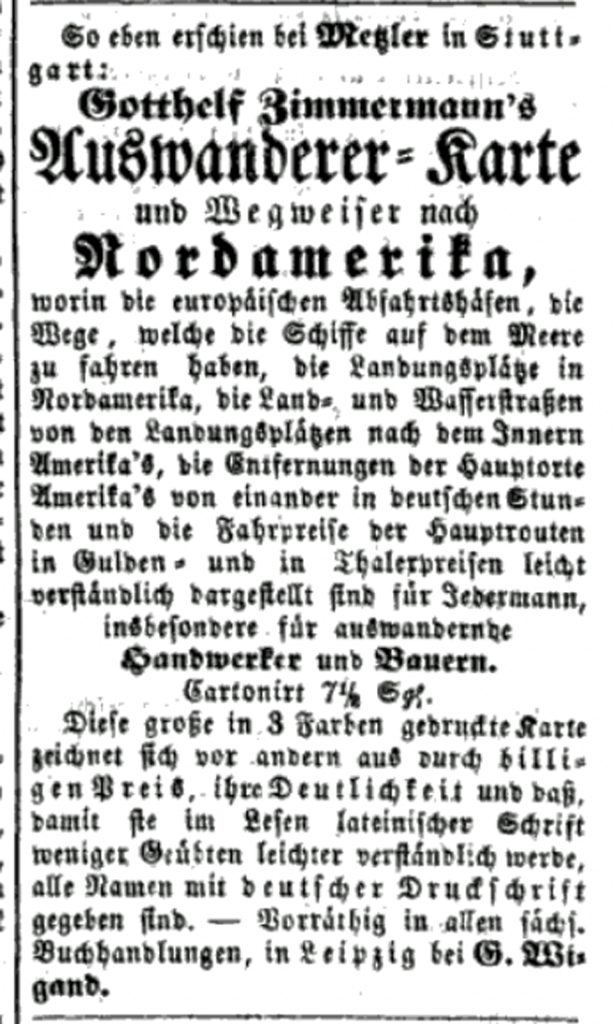

While the map is often referenced as the ‘1853 German Map’, its existence is documented prior to 1853. For example, the pamphlet or map is referenced in an advertisement in the newspaper Leipziger Freitag in September 1852 [12]

Advertisement for Zimmermann’s Map in the Leipziger Zeitung, September 1852

The advertisement states:

“Mesler in Stuttgart has just published: Gotthel Zimmermann’s emigrant map and guide to North America”

“Emigrant Map and Directions to North America, containing the European ports of departure, the routes that the ships follow at sea, the disembarkation points in North America, the land and water routes from the disembarkation points to the interior of America, the distances of the main American towns and cities (Hauptorte) from one another in German hours, and the cost of the trip on the main routes in guilder and thaler. Presented in an easy to understand form for everyone, especially emigrating artisans and farmers.“

Cartonized 7 1/2 Silver Groschen

“This large map, printed in 3 colors, is distinguished above all by its cheap price, clarity and basics, so that it is easier to read in Latin script for the less inclined, all frames are given in German print.”

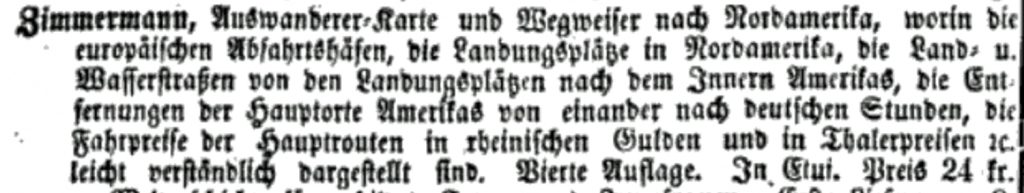

Another example of an advertisement for the map was found in the newspaper, Kempter Zeitung, in March 1854. [13]

Advertisement for Zimmermann’s Map in the Kempter Zeitung, Mar 12 1854

The following is a translation of the advertisement.

“Zimmerman, Emigrant Map and Guide to North America in which the European ports of departure, the landing places in North America, the land and waterways from these landing places to the interior of America, the distances of the main places in America from each other according to German hours, the of the main routes in Rhenish guilders and in prussian thaler are presented in an easily understandable way. Fourth edition. In case. Price 24 fr.”

The map was listed in a German book bibliography, Allgemeines Deutsches Bücher-Lexikon, as late as 1858. The Allgemeines Deutsches Bücher-Lexikon was a comprehensive German book lexicon or bibliography published in the 19th century. [14] The map was advertised in German newspapers and sold in multiple editions through the late 1850s, indicating demand for such emigration maps.

The Audience and Marketing of the Map

The map was intended for a specific audience: Germans who had an interest or plans for immigrating to America. The introduction of the Map, found in the lower right corner of the map states:

“Emigrant Map and Directions to North America, containing the European ports of departure, the routes that the ships follow at sea, the disembarkation points in North America, the land and water routes from the disembarkation points to the interior of America, the distances of the main American towns and cities [main places] from one another in German hours, and the cost of the trip on the main routes in guilder and thaler. Presented in an easy to understand form for everyone, especially emigrating artisans and farmers.”

“Gotthelf Zimmermann. Second Edition”

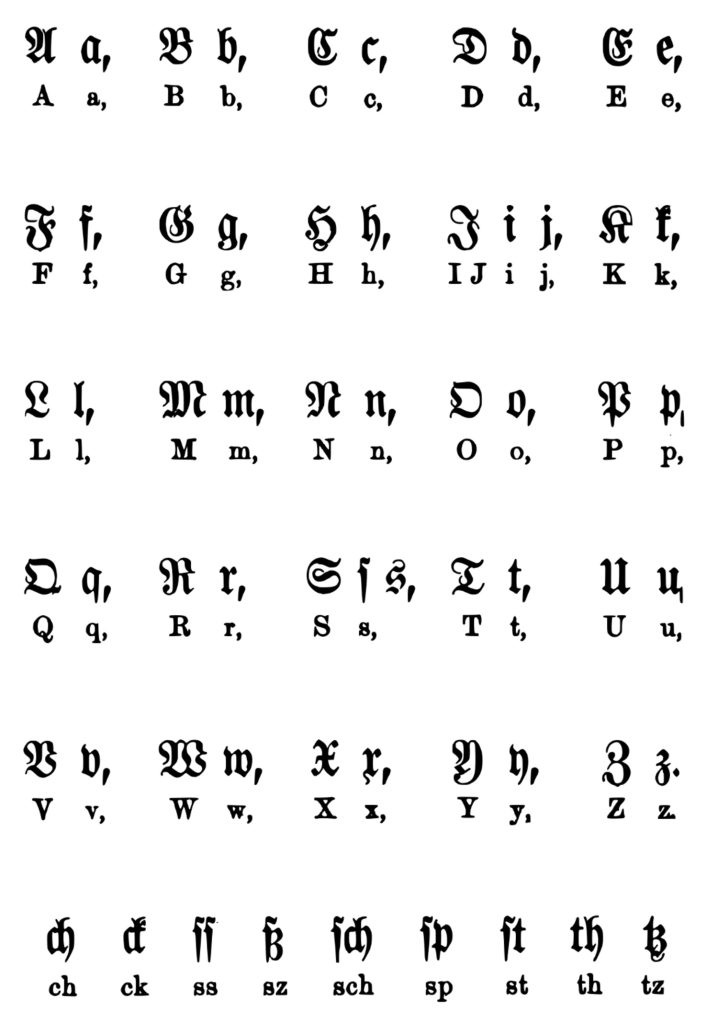

With the exception of the title of the map (which appears to use Textra print [15] ), the map is using Fraktur typeface which was a common typeface of the day. Fraktur type was used for printing in Germany throughout the nineteenth century. Frakur typeface became the most common German blackletter typeface from the mid-16th century until the early 20th century. [16] As the description of the map states: the map is “presented in an easy to understand form for everyone, especially emigrating artisans and farmers“.

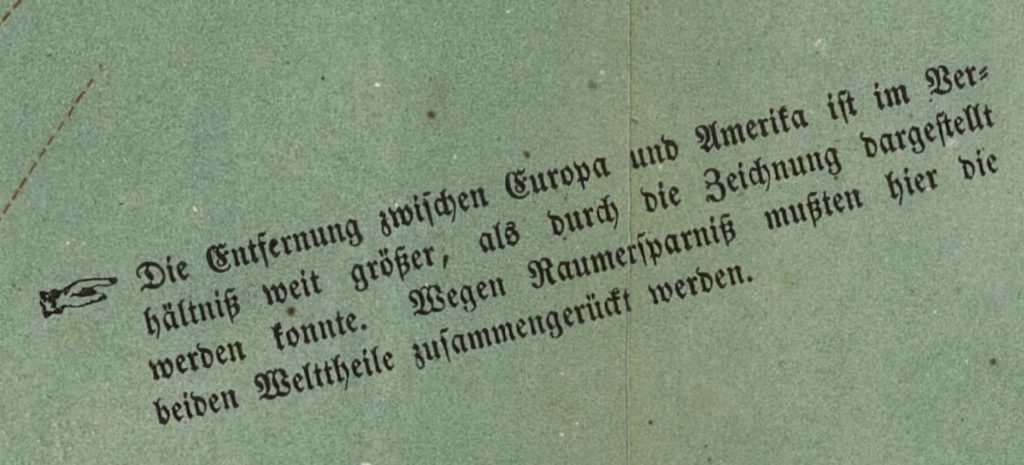

The map was intended to be published to fit on one piece of paper. The goal obviously was to fit both northern Europe and the United States and related information on the face of one piece of paper. The ability to fit this geographical space onto one page necessitated the need to take liberties on the accuracy of scale. This is explicitly mentioned in a note that was placed in the middle of the Atlantic ocean near Spain. The European countries and the American states are also not to scale on the map.

Annotation In-Between the Two Continents on the Map [17]

“The distance between Europe and America is relatively far greater than could be shown in the drawing. To save space, the two parts of the world had to be brought together here.”

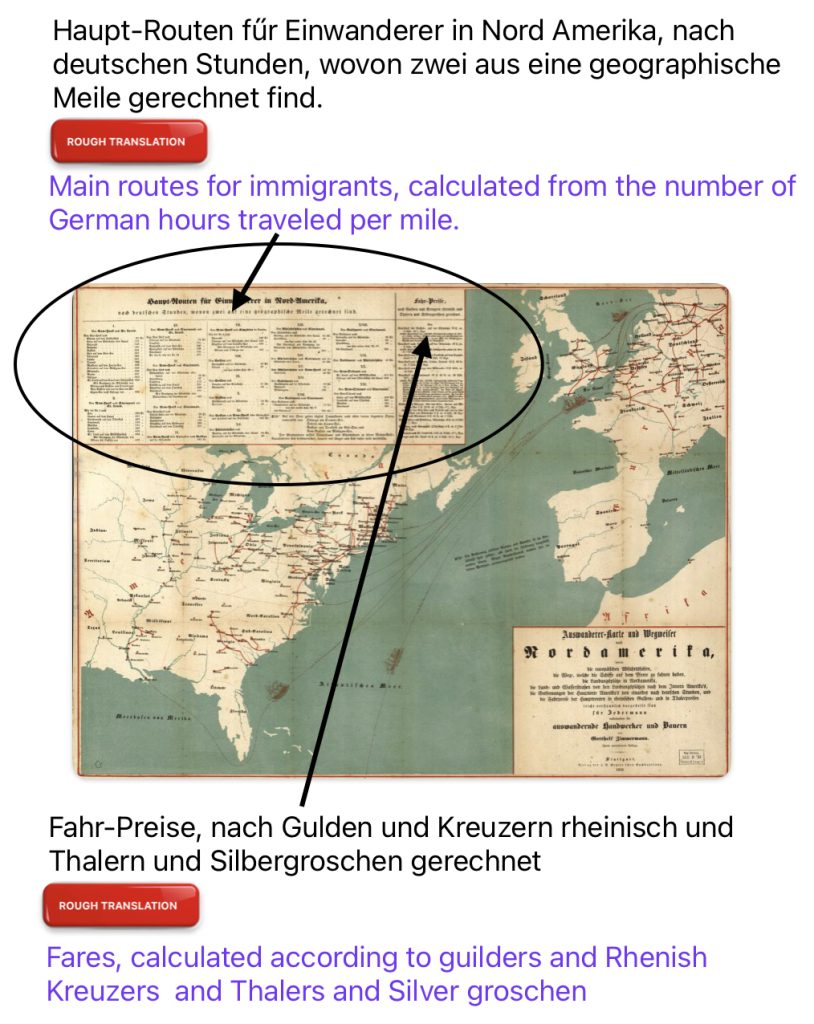

Information on Travel Distance and Cost

In the upper left hand corner of the map, traditional Fraktur German typography identifies cities and towns, and the distance and travel cost from each of the ports along the Atlantic coast to the interior towns and cities. Cost is provided in guilders, kreuzers and silver groschen. [18]

Illustration Two: Travel Time and Cost of Travel in the Zimmermann Map

An Example of a Baden Kreuzer

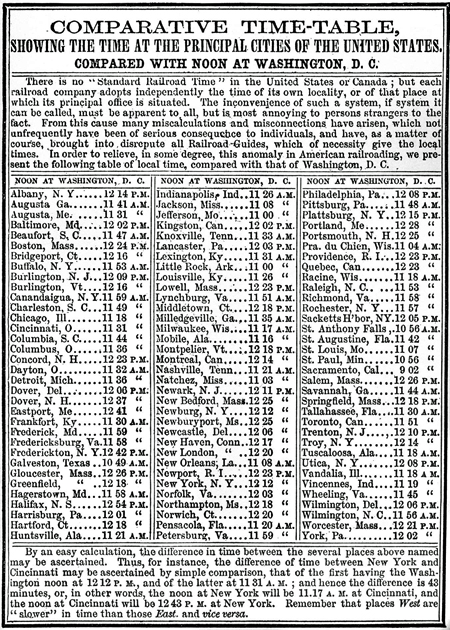

Comparative Time Table of Time 1868 [19]

“(F)or example, when it was noon in New York, it was 11:10 in Indianapolis, 11:19 in Cincinnati, 11:24 in Columbus, 11:30 in Cleveland, 11:36 in Pittsburgh, 11:56 in Philadelphia, and 12:12 in Boston—that is to say, local time was defined relative to the sun at midday.”[20]

It is not known what “nach deutschen Stunden“, by German hours, means in the context of Zimmermann’s calculation of the amount of time to travel between designated cities. It is not known if ‘German time’ implies the use of a standardized base for computing time for the figures found in the map. This could be possible since time was not standardized in the United States.

The growth of railroads in the 1800s exposed the problems with every locality having its own solar time, and drove the adoption of standardized time zones that enabled more efficient train scheduling and safer operations. But this transition occurred gradually over many decades. In the early-to-mid 1800s, each town kept its own local time, usually based on “solar time” where noon was when the sun was highest in the sky. This meant adjacent towns could have slightly different local times. Railroads initially had to deal with this patchwork of local times when scheduling trains. [21]

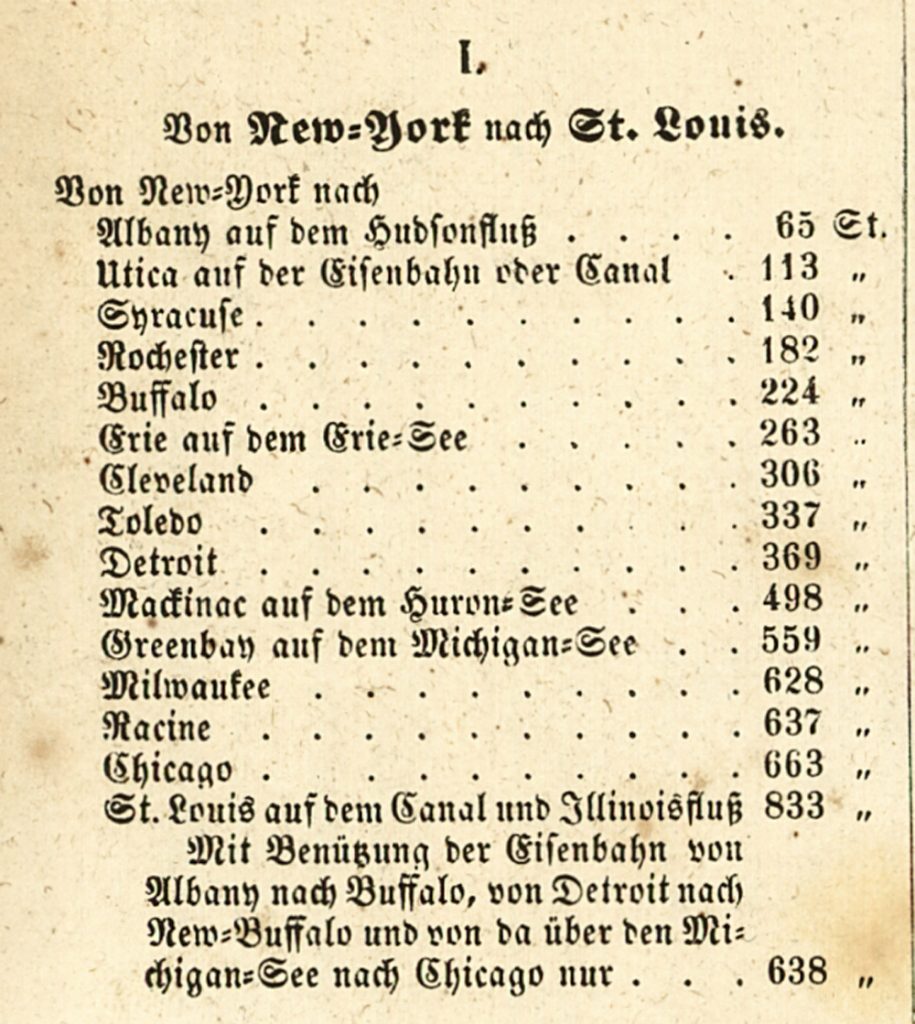

The map lists twenty-one combinations of trips and their distances from major United States cities. For example Part I lists routes from New York to various inland destinations.

The following is a rough translation of the estimated time in hours it took to travel between New York City and the various destination points.

It is not clear what mode of transportation was used to calculate the estimated number of hours to travel to each of these various places. I am assuming many of the above travel routes between New York and the various places listed were based on travel by water.

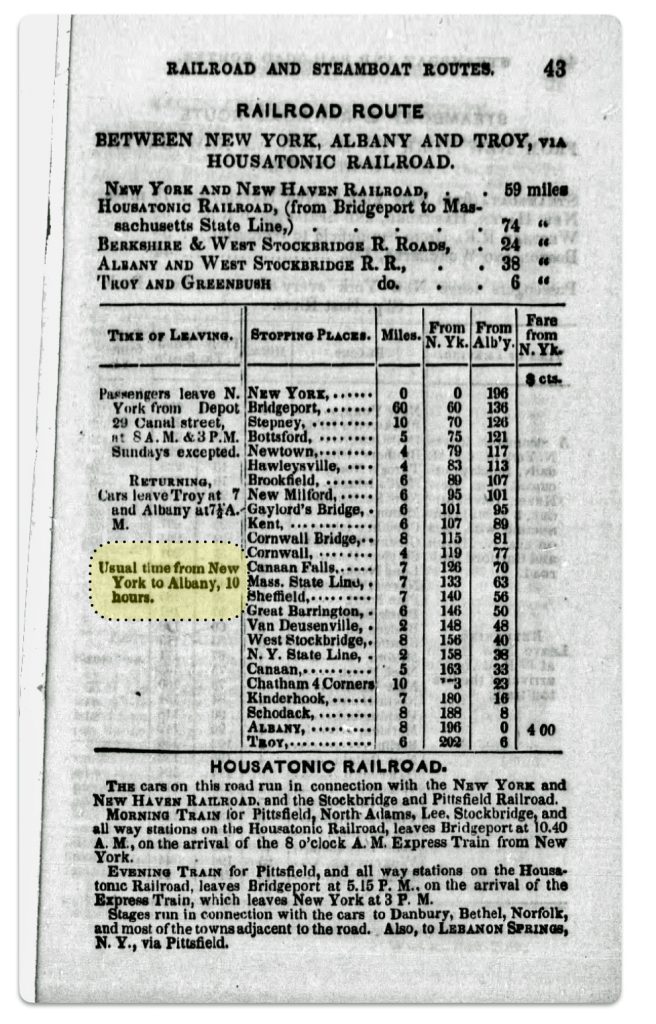

Comparing the estimated time for travel in the Zimmermann map with American travel guides published around the same time period suggests the ‘Zimmermann travel’ was based on travel on canals, rivers, or lakes.

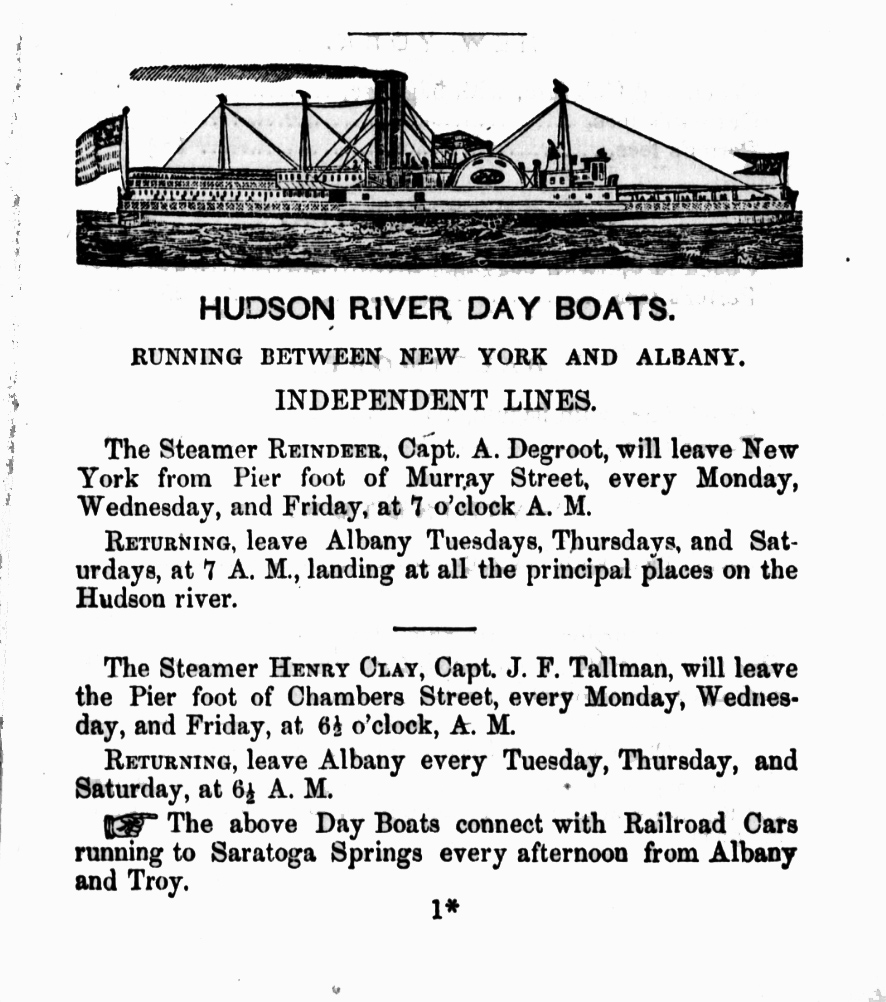

This is obviously the case traveling to “Albany on the Hudson River” (nach Albany auf hudsonfluss). For example, the Zimmerman map indicates the trip between New York city and Albany was estimated to be 65 hours in 1853 (perhaps based on data earlier than 1853 since that was the publication date). An 1851 travel publication indicated a train ride from New York to Albany took 10 hours (see below)

Travel on the Housatonic Railroad between New York City and Albany 1848 [22]

Hudson river days boats were also available in 1851 (see below). [23] Whether German immigrants utilized these boats or other slower vessels to travel further inland in New York state is not certain.

Hudson River Day Boats to Albany

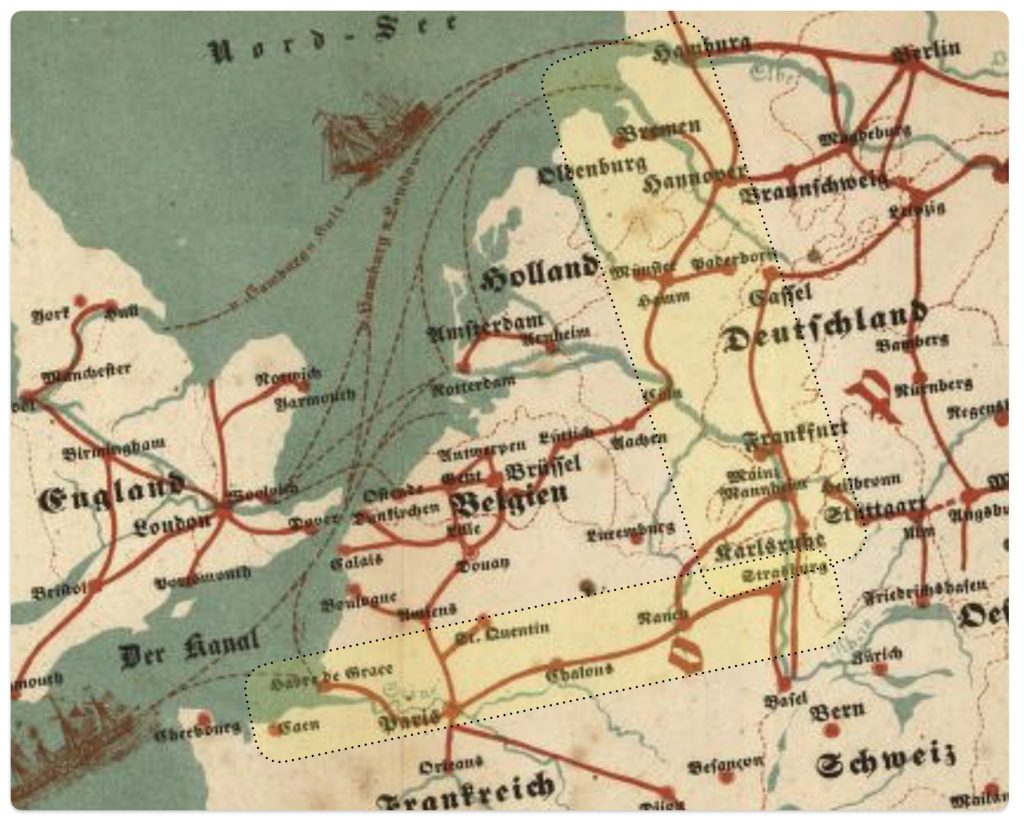

Major Land Routes in Europe Portrayed in the Map

The ‘1853’ map was the second edition of Zimmermann’s map. As such it purportedly represents knowledge of the transportation networks in Europe and the United States around that time.

There is no explicit legend defining what the red lines denote or mean in the map. It is not known if the red routes on the map are intended solely to denote railways or routes that include roadways and railways. Canals and rivers are in blue or grey (depending on what version of the map you are viewing).

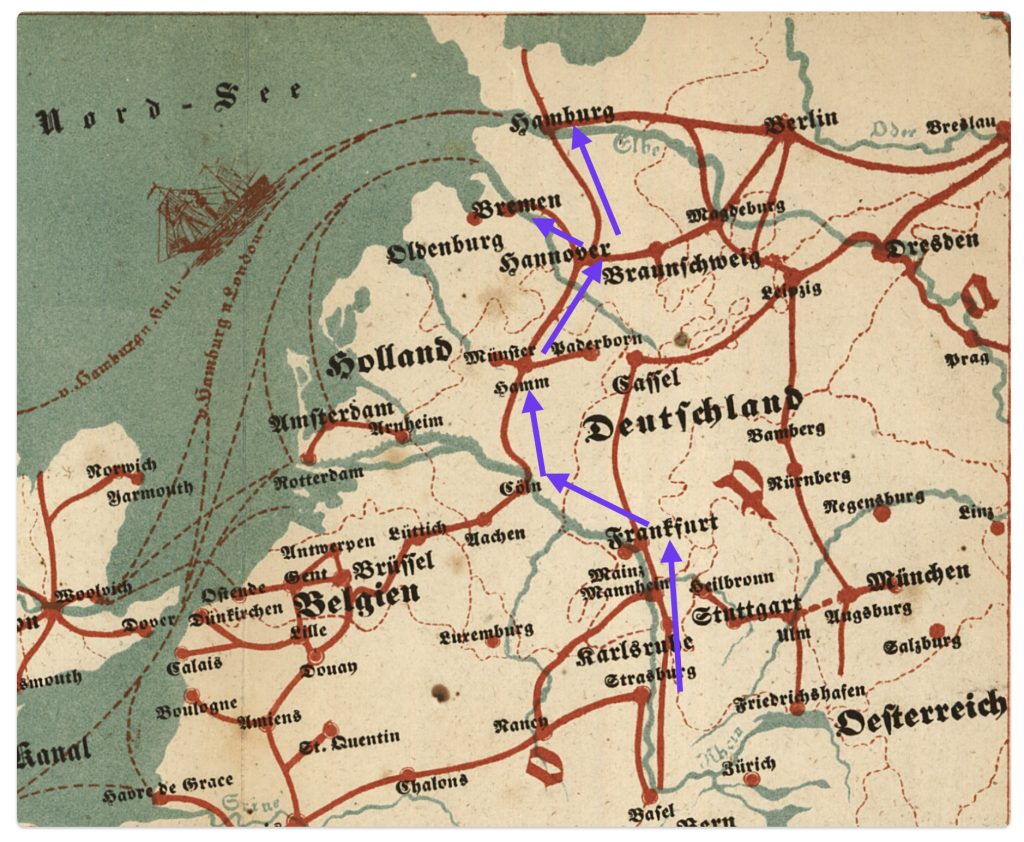

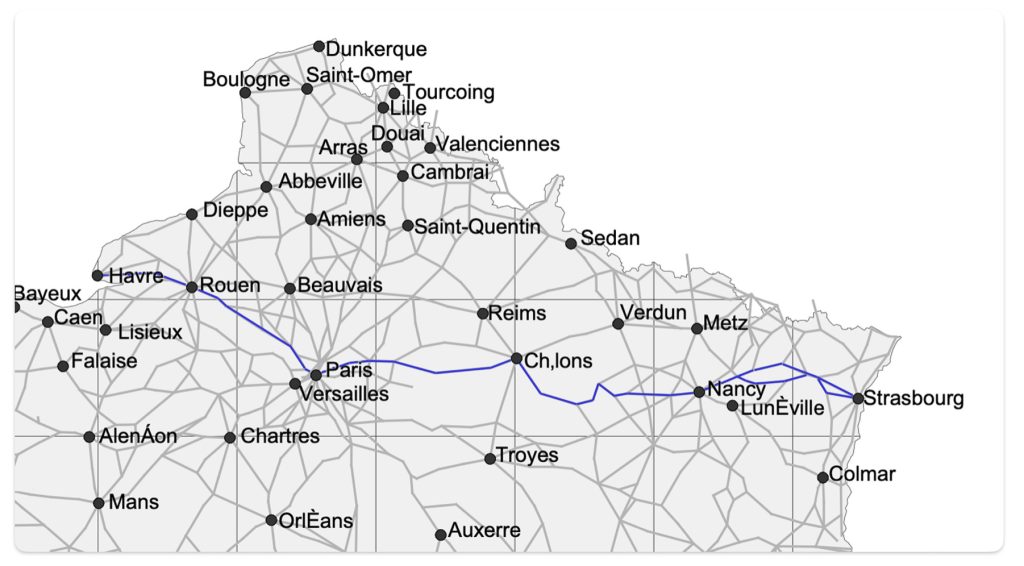

Map Two: Highlighted Possible Immigration Routes for John Sperber in 1852 on the ‘1853’ Zimmemann Map

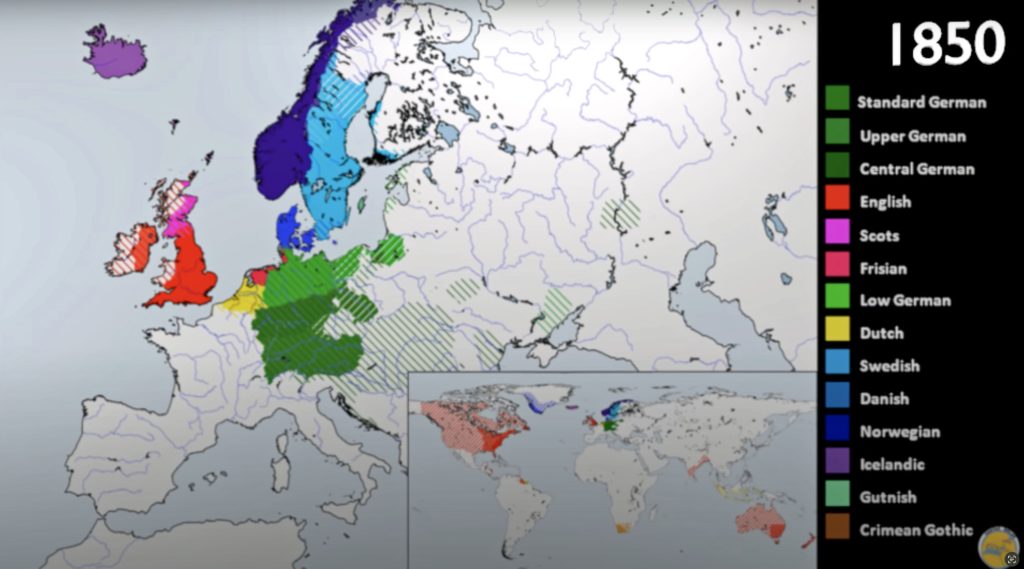

Based on an historical analysis of German migration, we know that the red routes in the map signify popular routes that German emigrants had taken to major European ports of departure for America between 1830 to the 1860s and perhaps onward. However, based on the historical development of French and German railway networks around 1850-1852, I believe the red routes on the map signify routes that include a combination of road and railway travel not just rail travel. (See map two)

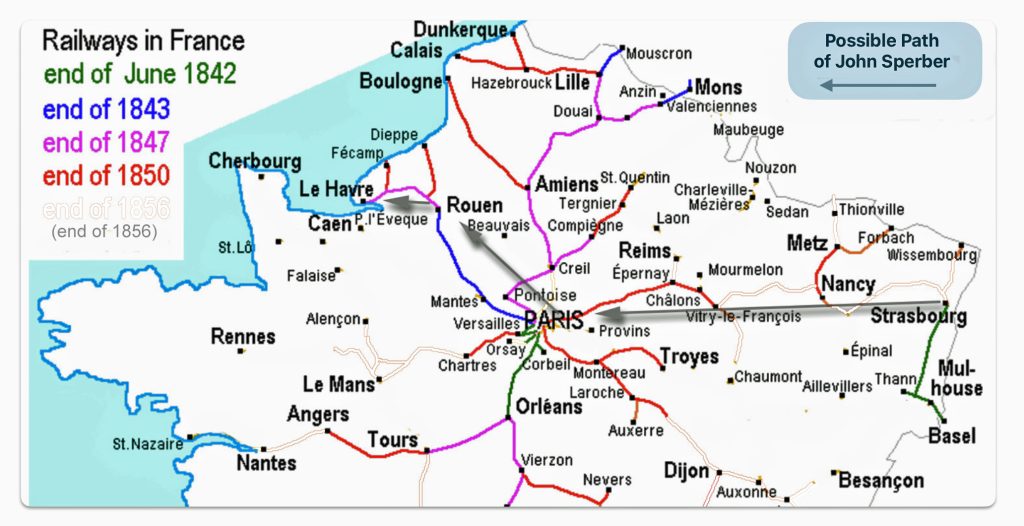

As indicated in a prior stories, a great great grandfather of mine, John Sperber, immigrated to America from Baden-Baden, Grand Duchy of Baden which is close to and on the other side of the Rhine River to Strasbourg, France. Based on historical evidence, I believe he traveled from Baden-Baden to Le Havre France and departed in 1852 to New York City. At the time of his journey the railway lines between Paris and Strasbourg were not complete. (See map three below)

If John traveled by railway, his options were limited. The rail line between Paris and Strasbourg was built and operated by the Compagnie du chemin de fer de Paris à Strasbourg, which later became part of the Chemins de fer de l’Est This railway line between Paris and Strasbourg was complete after John arrived to the United States in 1852. It was not available for him when he emigrated to the United States.

The first section of the French railway line between Le Havre and Strasbourg was opened in 1849. This first section connected Paris to Châlons-sur-Marne (see map three below). In 1850 a line from Nancy to Frouard and a line from Châlons to Vitry-le-François were completed. In the following year, a line from Vitry-le-François to Commercy as well as a line from Sarrebourg to Strasbourg were completed. Finally, in 1852, the year John Sperber emigrated, the sections between Commercy and Frouard, and the line between Nancy and Sarrebourg were opened. The 1852 sections were probably open after John’s voyage in June 1852. [24]

During this period, railway technology and infrastructure were rapidly developing. The rapid development had its impact on the production of maps. It has been observed that for American maps “even the most accurately drawn map which spent a month or two in production might miss more new railroad mileage during these years than had existed in the entire country in the 1830s or early 1840s. Some mapmakers tried to anticipate this fluidity by building their expectations for expansion into their maps, only to see those plans unrealized as funding fell through or construction was temporarily halted.” [25] I imagine this was an issue faced by the German and French map makers as well.

As reflected in map three, I have modified and removed from the original source map all of the rail lines that were built between 1850 and 1856. You can see of illustrative purposes, however, remnants of removed lines for the railways completed in this six year period. John Sperber may not have been able to travel by rail between Strasbourg, Nancy and Vitry-le-François. Even if they were able to travel by train, his journey would have been interrupted and punctuated with the need to travel by roadways where the train line was under construction. [26]

Map Three: French Railway System 1842 – 1850

Many of the major contemporary road arteries in France follow the routes of royal postal roads that were originally built in the 1700s. The French postal roads of the 1700s were innovative in their design and construction. Many of the these postal routes survived and became the major roadways in France. In fact, all of the roadways in the along the route from Strasbourg to Le Havre in 1853 are part of the old postal route system.

Map four below depicts the postal roads in northern France that linked major towns and cities in France in 1833. The creation of the map is the result of analyzing the changes over time of the expansion of postal routes in France through time. I have highlighted the postal roads that followed the possible route that John Sperber had taken to reach the post of Le Havre.

Based on the above analysis, I believe the Zimmermann ‘red route’ between Strasbourg and Le Havre merely denotes a popular route to Le havre that included roadway and railway, depending on when one traveled across northern France.

Map Four: French Postal Roads and Main Cities and Towns in 1833 and the Highlighted Possible Route of John Sperber from Strasbourg to Le Havre [27]

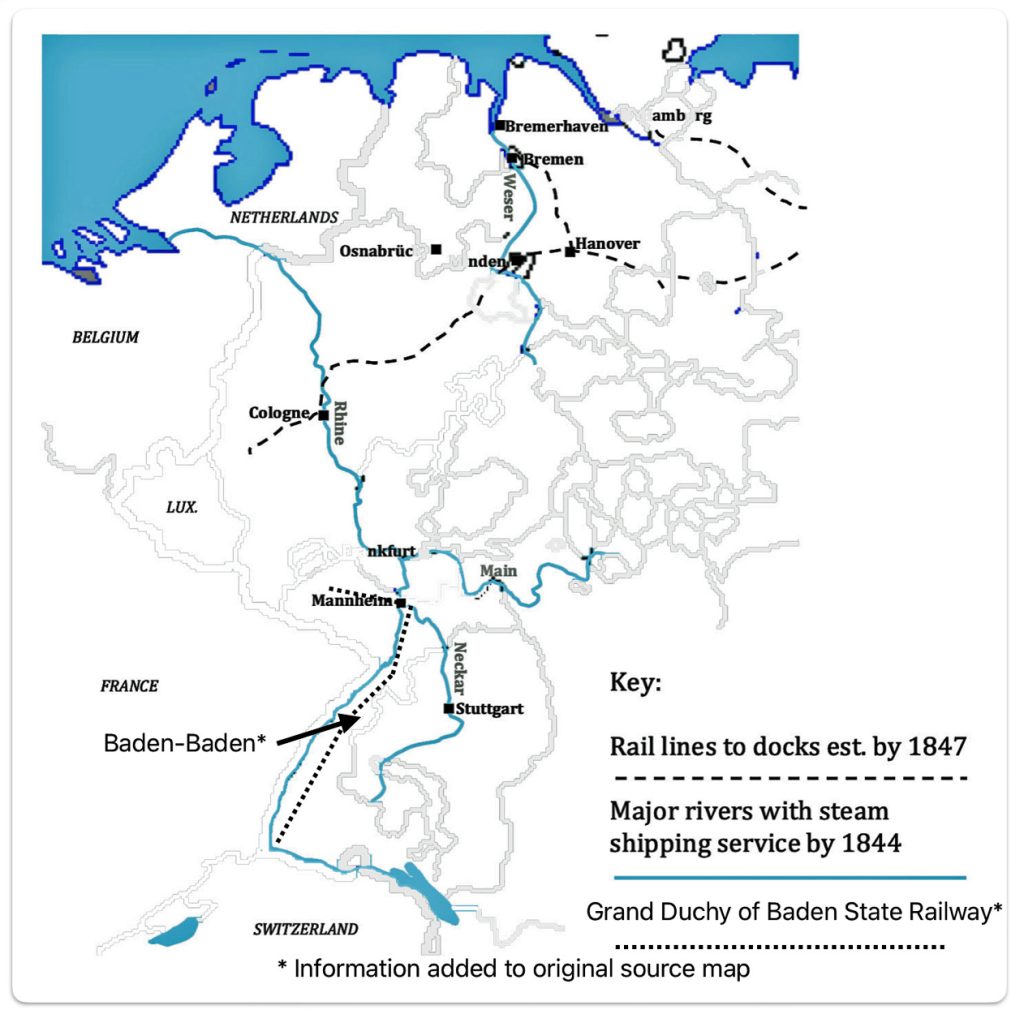

Between 1850 and 1853, the Baden to Bremen route probably was an effective alternative route for John Sperber’s consideration or others from the Grand Duchy of Baden. Bremen could have been reached by roadways from Baden. Bremen could also be reached through the use of a combination of train (Baden Main Line), waterway (the Rhine River to Cologne) and then rail via Hanover and Bremen. (See map five)

Map Five: Major Interior Rivers Served By Steam Transportation & Rail Lines to Docks of Bremen and Hamburg, 1847 [28]

Map six below is a portion of Zimmermann’s map that shows the same route that is reflected in map five.

Map Six: Portion of Zimmerman Map Showing Route from Baden-Baden to Bremen and Hamburg

Based on historical evidence on the development of German railways in the 1840s and 1850s, it is reasonable to assume that the red travel paths in the Zimmermann map for this particular “Baden to Bremen” route denote rail lines connected with waterways .

Depending on the specific popular routes in the Zimmermann map, the red lines may denote railways or roadways. Nonetheless, the emigrant map serves its purpose of providing a simplified depiction of the major routes to outgoing European ports.

Major Inland Routes in America Portrayed in the Map

The first thing that comes to mind when viewing the American cities and towns in Zimmermann’s map is why some of these locations were chosen and not others. Many of the cities in the map were obvious choices given German immigration patterns since the early 1800s.

“The sheer volume of detailed information in the map … raises the question of how the mapmaker assembled it. What advertising and promotional materials could he draw on? Newspapers? Firsthand reports from sales agents or people who had already emigrated? Related guidebooks or maps? Train and ship schedules? In any case, the information conveyed by this map was part of a broader ecosystem of knowledge of varying reliability bound up with the experiences and agency of those who had made or would make the journey.” [29]

Zimmermann may have obtained information for his map from various sources. He may have utilized the information contained in other German emigration maps, newspapers, and popular German travel and immigration books as a reflection of accumulated knowledge of migration. Information on travel schedules and major shipping routes were readily available in German newsprint.

Zimmermann may have also relied on pocket travel guides that were published in America. Many guides contained multiple large scale maps. These travel guides and maps often provided detailed depictions of travel routes, such as bridges and tunnels that are not easily seen on other, larger maps.

“Probably the best (American) nineteenth century railroad maps were those which appeared in “pocket” travel guides. Appearing first in the 1840s, some were published monthly; others, semi-annually or annually, often under slightly changed names. … Each went through many editions.” [30]

The Zimmermann map highlighted the major American port cities of the mid 1800s like New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Baltimore and New Orleans. New York was major port of entry during the time period.

“Her connection with the interior was a prime cause of New York’s commercial supremacy, and the two together account for the growing favor shown her by immigrants. In the middle of the century Buffalo, Cleveland, and Milwaukee were the distributing points for those bound to the Northwest, and to reach these cities the Erie Canal and, after 1846, the railroad from New York to Buffalo were by far the quickest and the cheapest routes. For those bound to the Middle West, Wheeling, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and St. Louis were the distributing points; and for reaching them New York offerred facilities as good as those from Philadelphia and better than those from Boston or Baltimore. New Orleans was favorably situated for such as were bound for the Mississippi Valley and she did receive a considerable number of immigrants; but the voyage was two or three weeks longer than to New York, the ships sailing thither from Europe were inferior, the journey up the Mississippi to St. Louis was unpleasant, dangerous, and little shorter than from New York, and above all, the dread of yellow fever and other maladies common among strangers in a southern climate combined to deter most Europeans from choosing that route.” [31]

The Zimmermann map also identifies inland cities in the midwest that were popular destinations for German immigrants. In the nineteenth century, German immigrants settled in Midwest, where land was available. Cities along the Great Lakes, the Ohio River, and the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers attracted a large German element. The Midwestern cities of Cleveland, Cincinnati, Fort Wayne, Milwaukee, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Chicago were favored destinations of German immigrants. The Northern Kentucky and Louisville area along the Ohio River were also a popular destinations. Dubuque and Davenport, Iowa and Omaha, Nebraska, were also areas where Germans settled. By 1850 there were 5,000 Germans in Ann Arbor, Michigan. [32]

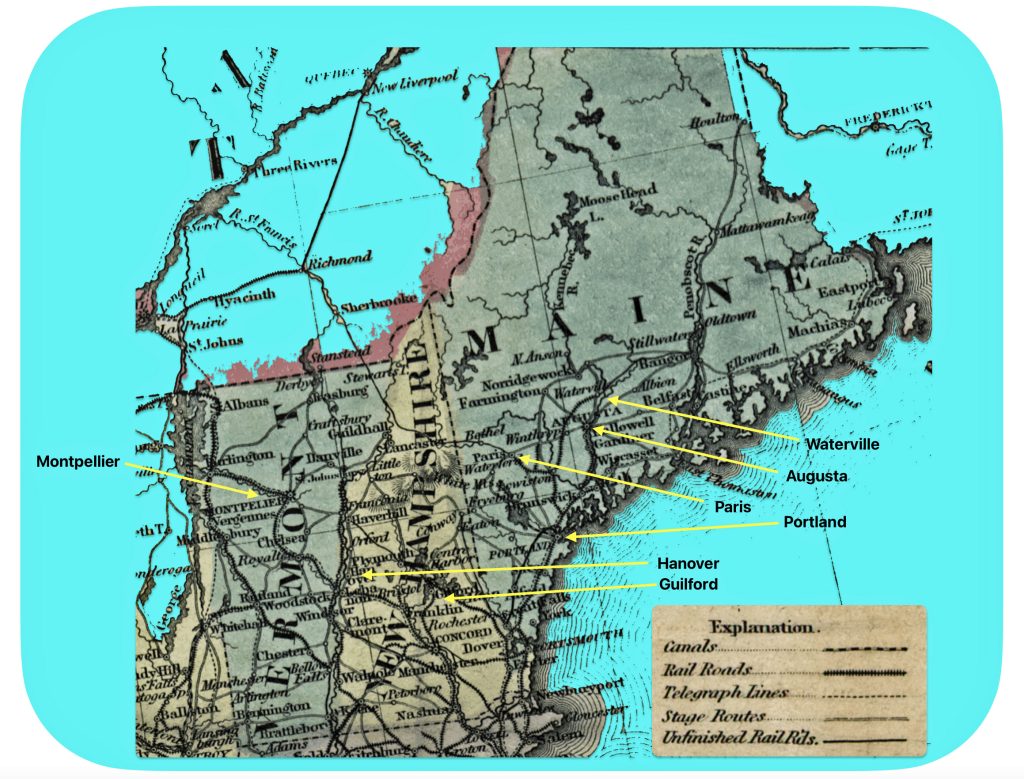

The presence of smaller cities and towns on the Zimmermann map are a bit puzzling, perhaps due to my lack of knowledge of the history of the towns. Smaller inland towns like Guilford and Hanover in New Hampshire; Montpellier in Vermont; and the Maine towns of Portland, Waterville, Augusta and Paris are identified along red routes on the map. Perhaps these towns were noted on the map based on reports from earlier German migrants, earlier settlements or efforts by land developers to attract settlers. [33]

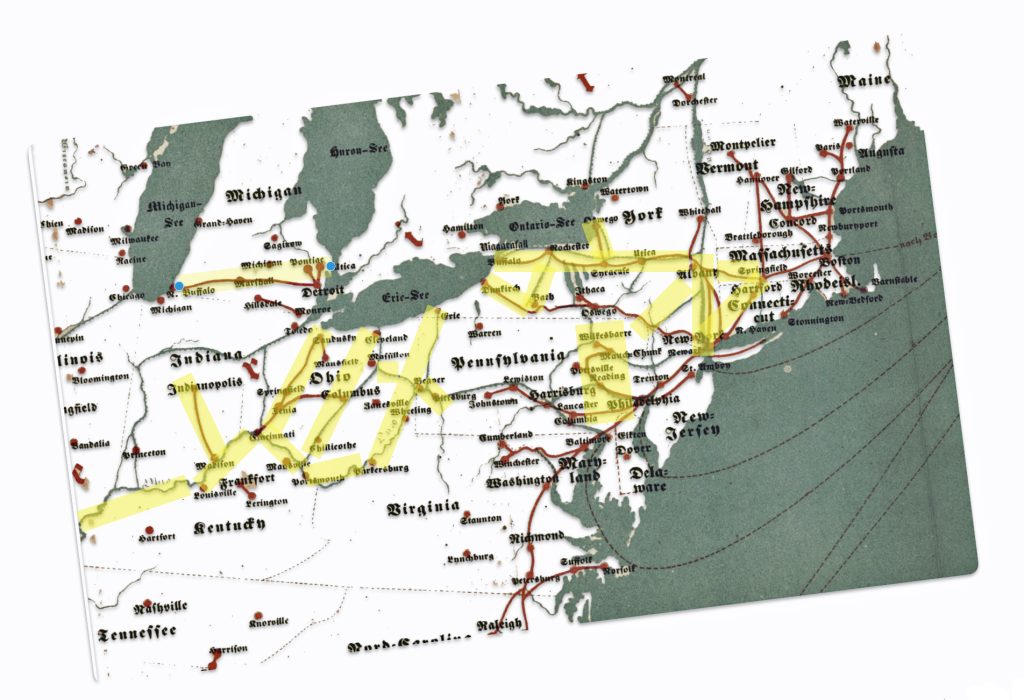

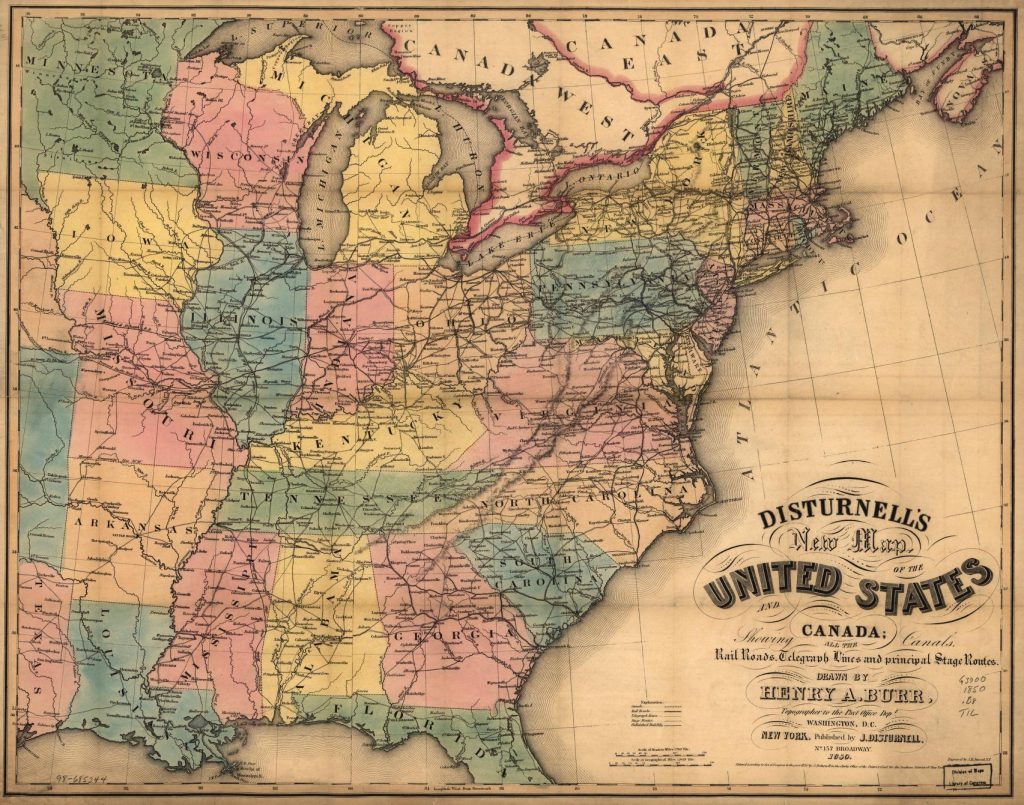

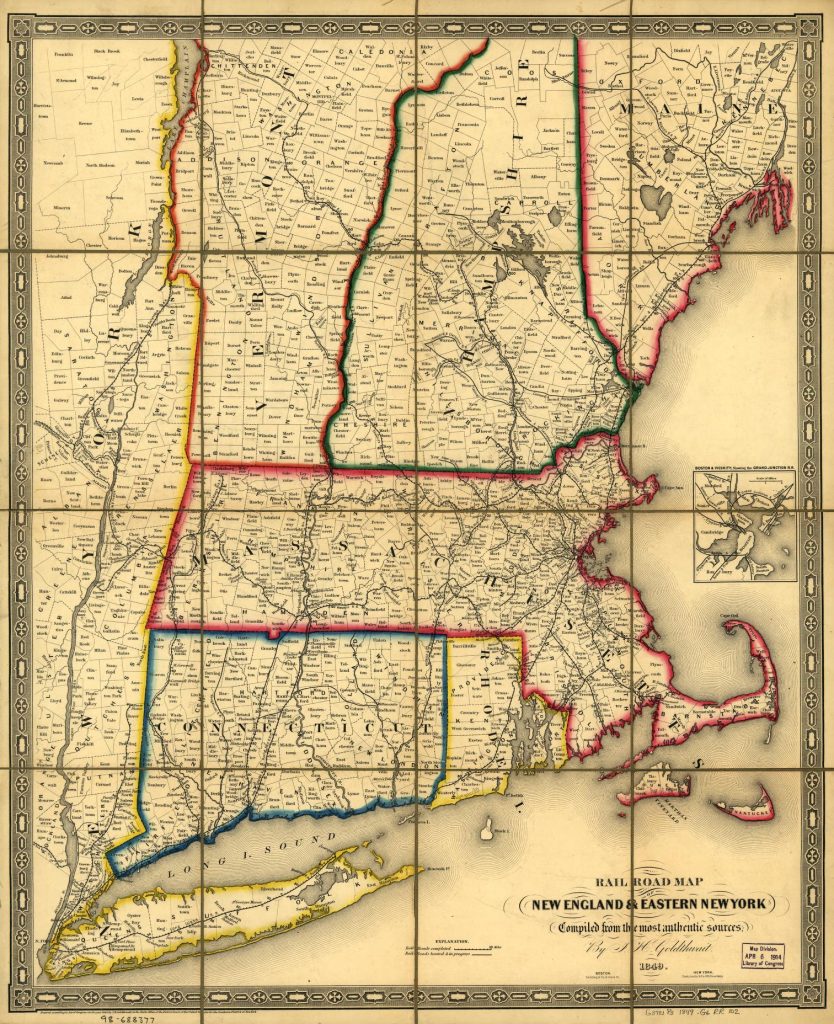

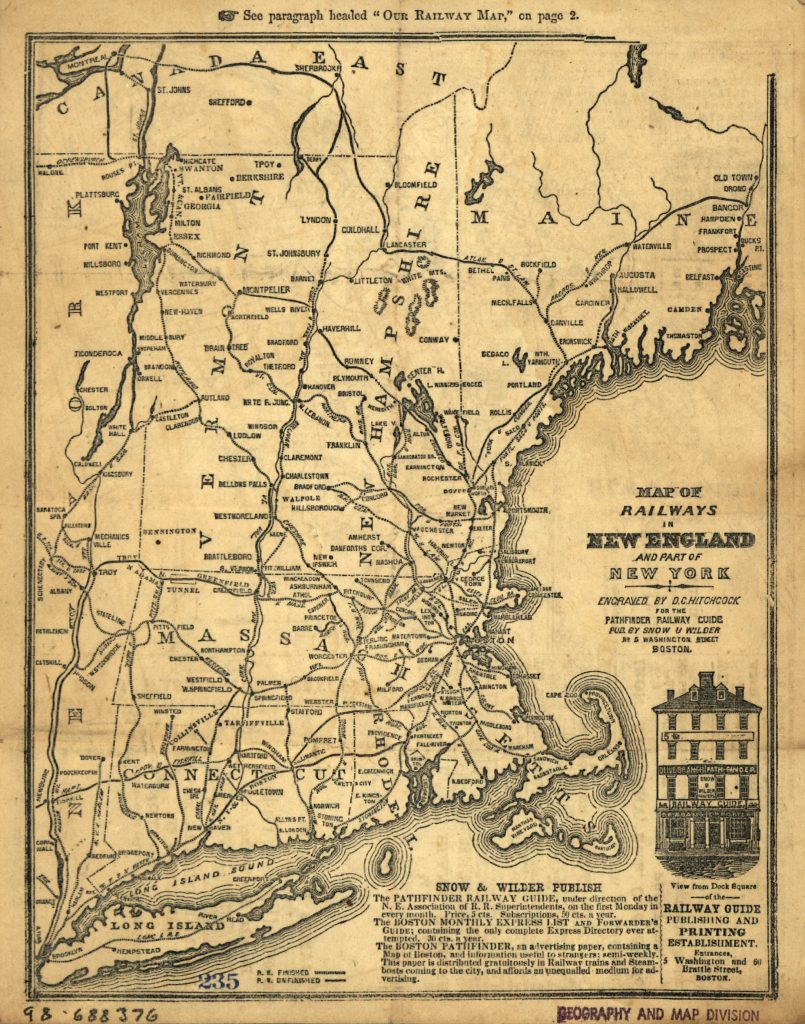

It is interesting to compare Zimmermann’s simplified, elegant emigrant map with a more detailed American map that shows canals, railroads, telegraph lines and principal stage routes. [34] If compare the transportation networks that existed in 1850 (see map seven) with the simplified ‘1853’ Zimmermann emigrant map (see map eight), one can see the transportation links with the above mentioned towns and cities in Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine. All of these towns had rail connections.

Map Seven: Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine 1850 [35]

Map seven depicts railways, roadways, and waterways. As evident in the 1850 map, the towns highlighted in Zimmermann’s map are linked to other towns through railways, waterways and roadways.

Map Eight: Portion of Zimmermann’s Emigrant Map: Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine

Similar to my conclusion regarding what the red lines denote for travel paths on the European continent, I believe the red lines depicting travel routes to inland cities in the United States also represent ‘popular routes’ that are a combination of roadways, railways and waterways.

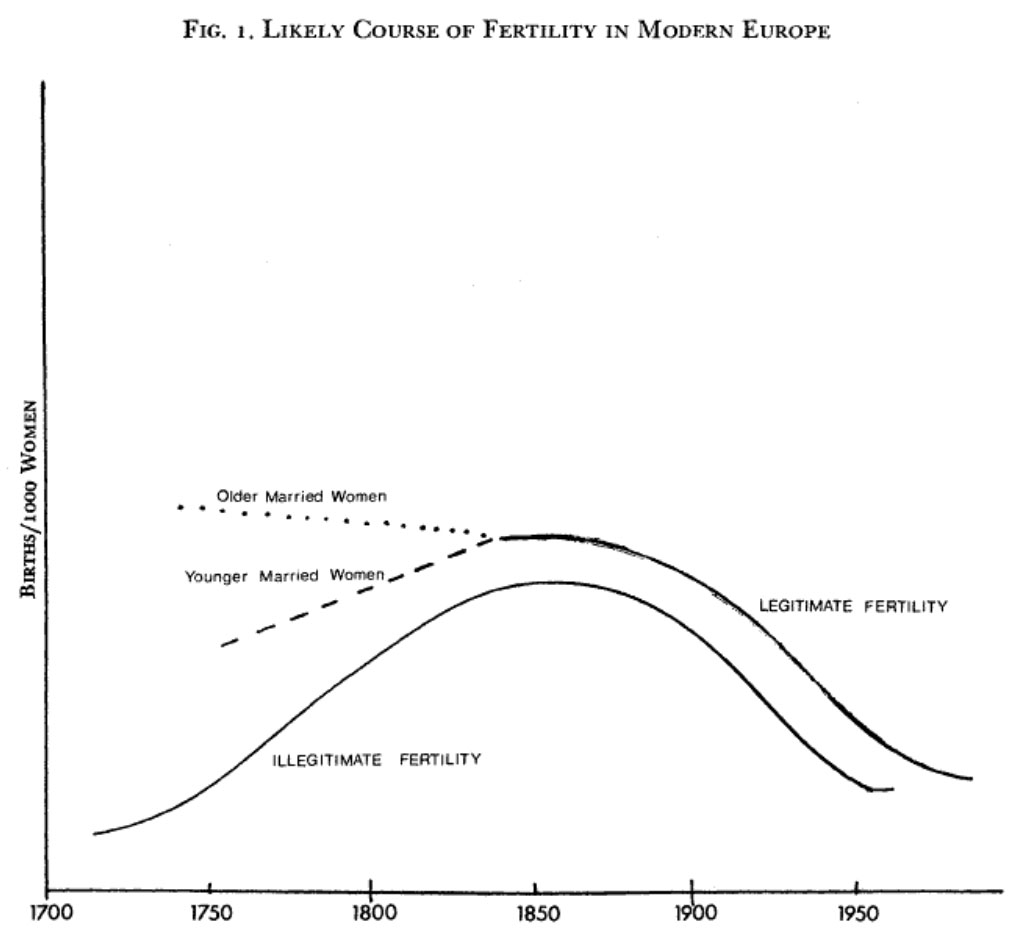

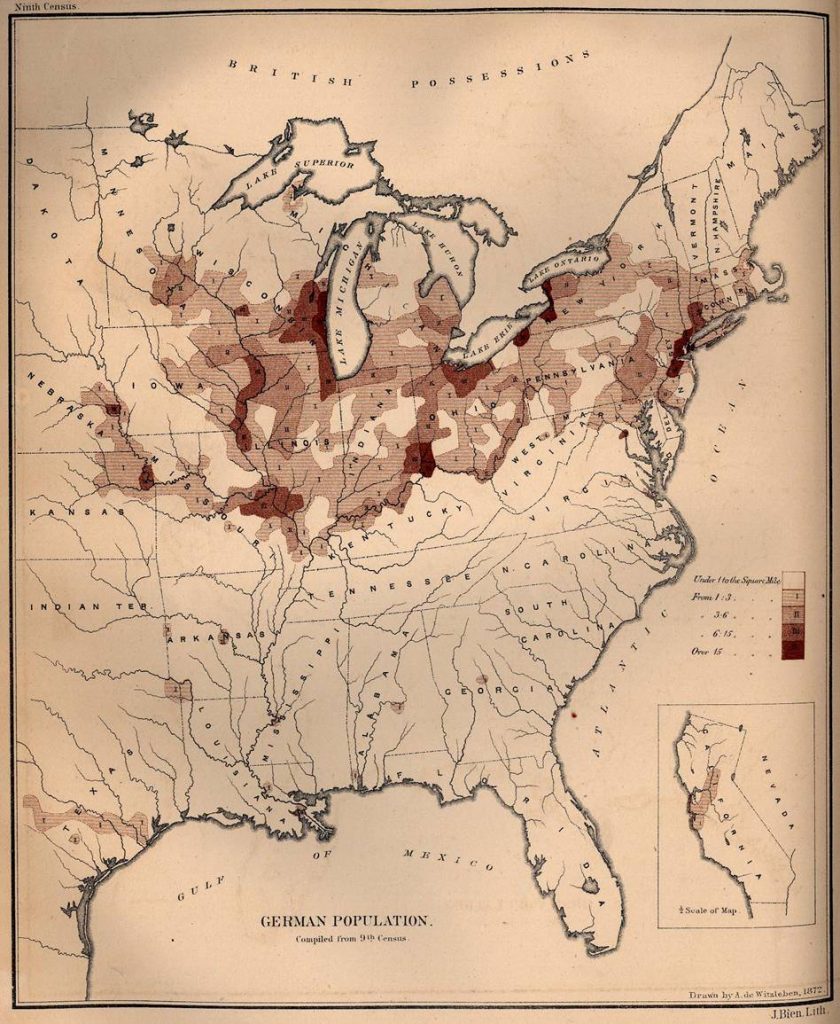

Comparing Transportation Networks in the 1953 Zimmermann Map and German Population Density in 1870

While this map was designed for the purpose of providing guidance to German immigrants for planning travel to the United States, it provided a ‘snapshot’ of the current state of affairs for German émigrés that traveled to America.

Railroads and waterways, natural and man made, had a significant influence on German immigration and settlement patterns in the United States during the 19th century. In the 1700s and early 1800s, a majority of German immigrants settled in cities and rural areas near the major ports on the eastern seacoast roadways and waterways increased their travel inward on the American continent. [36]

In the central part of America, many German immigrants initially settled in cities along major waterways like the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, as these provided transportation routes into the frontier. Towns with large German populations developed along the Missouri River in the early to mid-1800s. [37]

The opening of the Ohio & Erie Canal in the 1830s attracted more German immigrants to settle in Cleveland and other cities in Ohio. Canals in general improved transportation and opened up new areas for settlement before railroads became dominant. [38]

Railroad construction in the mid to late 1800s enabled German immigrants to travel further inland to establish new settlements, especially in the Midwest. Many Germans worked as laborers to build the railroads. As railroads expanded, new waves of German immigrants arrived and often settled in areas that already had established German communities. However, the core areas of German settlement did not significantly expand, with the exception of a few new settlements along railroad lines in the 1870s-1880s. [39]

Railroads played a key role in the rapid growth of cities like Chicago, St. Louis and Milwaukee which developed large German populations in the late nineteenth century. There was a “German triangle” in the Midwest connected by rail between New York, Minneapolis, St. Louis and Baltimore where there was a concentration of German settlement.

While this pamphlet-sized map was designed for the purpose of providing guidance for planning travel to the United States, it provided a prescient future view of settlement patterns for subsequent generations of German-Americans. The significant influence on the history of American transportation networks on nineteenth century German immigration and settlement patterns is apparent if we compare Zimmermann’s map with density settlement patterns of Germans in 1870.

“The 1870 census provided the nation with an astounding array of graphic and cartographic depictions of its state of geographic knowledge.” [40] A national atlas produced by the U.S. government was first realized in the Statistical Atlas issued by the Bureau of the Census with the 1870 census. The U.S. census had been transformed from a massive tabulating project to assist in apportioning Congressional representation among the states to a quantitative scientific accounting of numerous aspects of the nation’s many human geographies.

“Members of the fledgling American Geographical Society and American Statistical Society, including the geographer Daniel C. Gilman of Yale University, Samuel B. Ruggles of the American Geographical Society, and Edward Jarvis of the American Statistical Association, had attended meetings of the International Statistical Institute in Europe where new ideas concerning the graphic presentation of information were regularly discussed.” [41]

The 1870 census and its supplemental publications introduced more sophisticated capabilities for visualizing quantitative information, both graphically in charts and cartographically in thematic maps. The Census Office issued its first 1870 census thematic maps in its final reports, just before publishing the Statistical Atlas. These reports included a total of some twenty-six thematic maps. [42] The atlas appeared as a complete volume in 1874.

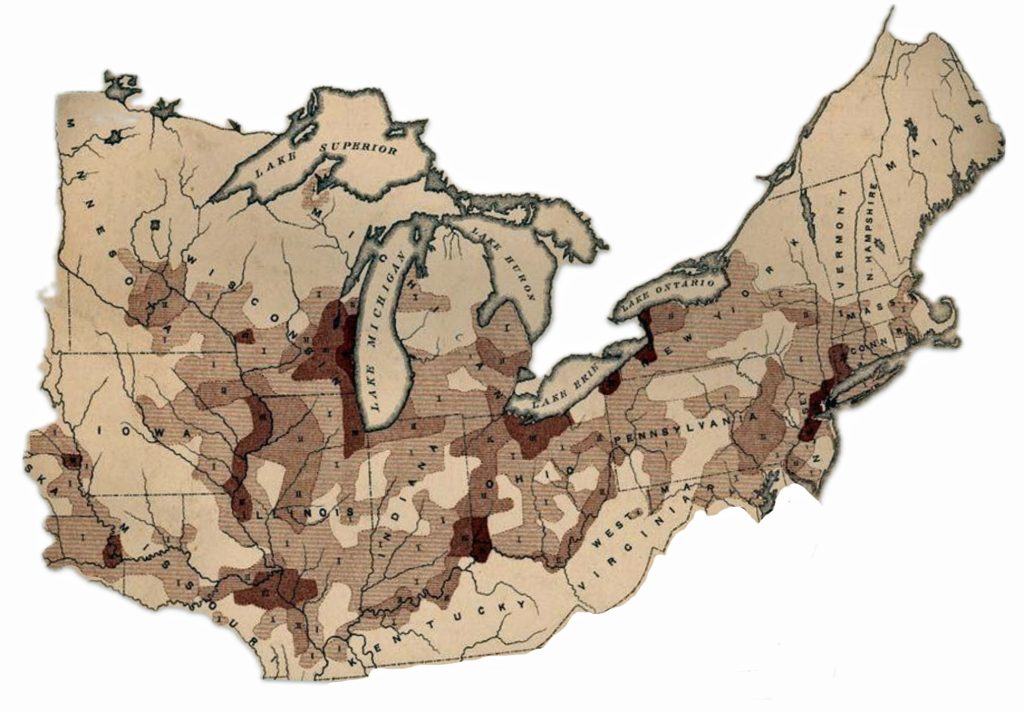

Map nine is from the Ninth U.S. Census. It indicates the density of people of German descent living in the eastern half of the United States in 1870, twenty years after the publication of Zimmermann’s map. The 1870 U.S. Census map provides the population density patterns of people of German descent in the eastern portion of the United States. The U.S. Census map indicates that individuals of German descent are largely found along and above the Missouri and Ohio Rivers in the mid-west. The Mason-Dixon line appears to be an imaginary line for Germans settling in the United States. Individual of German descent are found in New York, Pennsylvania, parts of Massachusetts and Connecticut, the Great Lakes region above the Ohio River and along the Missouri River.

Map Nine: Density of German Population in U.S. in 1870

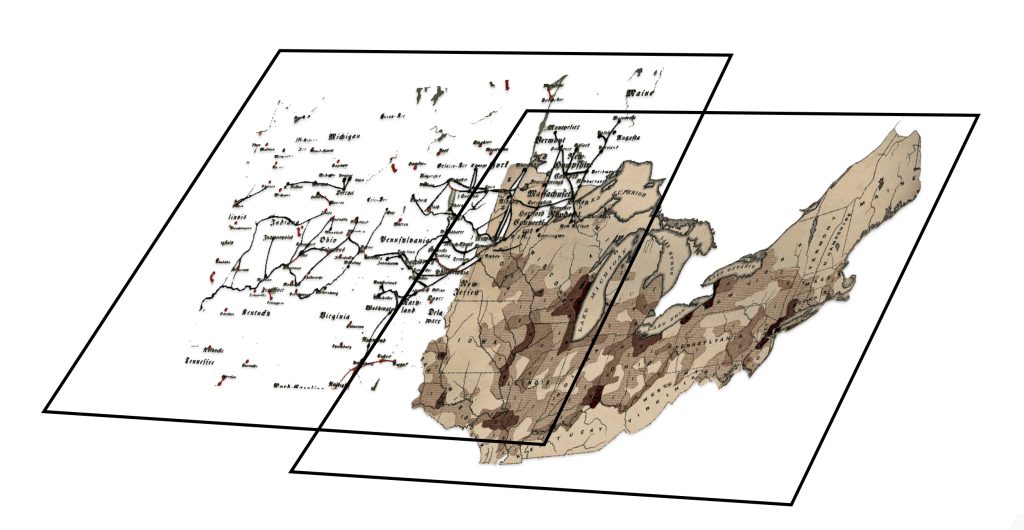

It is interesting to compare the density patterns of the German population in 1870 with the transportation routes depicted in Zimmermann’s map. I abstracted the transportation routes of the Northeastern United States from the Zimmermann map and I tried to overlay both maps. The latitudinal and longitudinal scales of each map are different. I was unsuccessful in modifying the dimensions of each map to make them conform and consequently was unable to overlay both maps to provide a visual comparison. The image below graphically shows what I was attempting.

Illustration Three: Attempted Overlay of Zimmermann’s Map with 1870 U.S. Census Density Map of German Population

Despite my failure to meld and overlay both maps, if both maps are closely examined (maps ten and eleven), you can see that Germans ultimately settled along major transportation networks that existed in the 1850’s. Zimmermann’s map depicted the major transportation arteries to cities in the United States at this time. I have taken the northeastern portions of each map for comparison. In map eleven, I have highlighted in yellow the major routes in Zimmermann’s map that correspond with dense areas of German population in 1870.

Map Ten: Density of German Population in 1870 in North East and North Central United States

Map Eleven: Transportation Netweks Abstracted from Zimmermann’s Emigrant Map

The rapid development of rail lines and the pre-existing river transportation networks enabled and encouraged German immigrants to spread westward from initial entry points on the East Coast, concentrating in the Midwest and the Plains states that became the “German belt” in the 19th century. [43] The transportation infrastructure had a fundamental effect on the settlement patterns and density of German immigrant communities. [44]

German immigrants often traveled inland to the Midwest after arriving at ports like New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New Orleans. They also to a lessor extent used the Mississippi, Ohio, and Missouri river systems to reach areas in the “German triangle” between Cincinnati, Milwaukee, and St. Louis where many of them settled. [45]

The expansion of railroads in the mid-1800s enabled German immigrants to more easily travel west from the East Coast to settle in the Midwest and establish farms. States in the “German belt” stretching from Pennsylvania to Oregon saw high concentrations of German settlement.

Cities along major waterways like the Great Lakes, Ohio River, and Mississippi River, such as Milwaukee, Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Chicago, became centers of large German-American populations in the 1800s. Access to both rail and water transportation supported rapid growth and industrialization in these areas.

A Map to Guide and a Map to Predict

Zimmermann’s map was a simple map that contained a wide range of information for German emigrants making their journey to America. While it served a very useful purpose in the 1850s, his map reflected the current outlines of the transportation infrastructure in Europe and the United States. It also provided a glimpse of the emerging graphic outline of the immigration patterns of where Germans and their families eventually settled in the United States.

Maps “record efforts to make sense of the world in physical terms. They capture what people knew, what they thought they knew, what they hoped for, and what they feared. They invest information with meaning by translating it into visual form, and in so doing reveal decisions about how the world ought to be seen. Above all, they demonstrate that the past was not just a chronological story but a spatial one as well. ” [46]

Sources

Feature banner: The banner is an amalgam of parts of the 1852-1853 immigration map that is discussed in the story.

Source: Gotthelf Zimmermann, Auswanderer-Karte und Wegweiser nach Nordamerika, 2nd ed. (Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler’schen Buchh., 1853), Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, DC, http://www.loc.gov/resource/g3701e.ct000244

[1] Zimmermann, Gotthelf. Auswanderer-Karte und Wegweiser nach Nordamerika. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler’schen Buchh, 1853. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/98687132/

[2] Ronald Grim discusses Grim, Ronald, Mapping Migration andSettlement, The Newberry, https://mappingmovement.newberry.org/mapping-migration/

For an interesting perspective on cartography andAmerican history, see: Mapping Movement, The Newberry, https://mappingmovement.newberry.org

[3] For example, a February 2024 Reddit discussion thread, titled “A German map of American ports and major cities, intended for use by travelers and immigrants to the United States, circa 1853. The German immigration wave to the US soared to then-record numbers around this time”, implies that the map had a substantial correlation with German migration to the United States. https://www.reddit.com/r/TheWayWeWere/comments/1ajwfvd/a_german_map_of_american_ports_and_major_cities/

Danzer, Gerald A. Danzer with James Akerman, American Railroad Maps, 1828 – 1876, The Newberry, https://mappingmovement.newberry.org/american-railroad-maps-1828-1876/

[4] Susan Schulten, A History of America in 100 Maps, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2018, Page 9

[5] Schulten, Susan, How Maps Reveal, and Conceal, History, Progress: A Blog for American History, https://www.oah.org/process-blog/schulten-maps/

See also:

Susan Schulten, A History of America in 100 Maps, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2018, Pages 138 – 239

[6] Kamphoefner, Walter D. “Immigrant Epistolary and Epistemology: On the Motivators and Mentality of Nineteenth-Century German Immigrants.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 28, no. 3, 2009, pp. 34–54. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40543427

For a general review of research on German emigration and immigration, see Helbich, Wolfgang. “German Research on German Migration to the United States.” Amerikastudien / American Studies, vol. 54, no. 3, 2009, pp. 383–404. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41158447

See also:

Félix Krawatzek and Gwendolyn Sasse, Integration and Identities: The Effects of Time, Migrant Networks, and Political Crises on Germans in the United States. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 60(4), June 2018, 1029-1065. doi:10.1017/S0010417518000373 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/comparative-studies-in-society-and-history/article/abs/integration-and-identities-the-effects-of-time-migrant-networks-and-political-crises-on-germans-in-the-united-states/A5B951CA7AEB2C2C33958799C40FDDA2

See also other work of Krawatzek and Sasse where they developed a computer-aided textual analysis of about 6,000 letters sent between the US and Germany between 1830 and 1970. Their contents allowed the researchers to trace how migrants’ identities and transnational ties changed over the decades.

Félix Krawatzek and Gwendolyn Sasse, Writing home: how German immigrants found their place in the US, February 18, 20016, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/writing-home-how-german-immigrants-found-their-place-in-the-us-53342

Félix Krawatzek, Gwendolyn Sasse, The simultaneity of feeling German and being American: Analyzing 150 years of private migrant correspondence, Migration Studies, Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2020, Pages 161–188 https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mny014

Félix Krawatzek and Gwendolyn Sasse, Deciphering Migrants’ Letters, November 28, 2018, comparative Studies in Society and History, https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/cssh/tag/krawatzek/

Walter D. Kamphoefner, Wolfgang Helbich, et al., Editors., News from the Land of Freedom: German Immigrants Write Home (Documents in American Social History) : Cornell University Press, 1991.

Karl Dargel, Tyler Hoerr, Petar Milijic, Economic Migration: Tracing Chain Migration through Migrant Letters in an Economic Framework, Global Histories, Special Issue (Feb 2019) Pages 19 -30

Moltmann, Günter. “Migrations from Germany to North America: New Perspectives.” Reviews in American History, vol. 14, no. 4, 1986, pp. 580–96. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2702202 Accessed 26 Sept. 2023.

Helbich, Wolfgang. “German Research on German Migration to the United States.” Amerikastudien / American Studies, vol. 54, no. 3, 2009, pp. 383–404. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41158447Accessed 26 Sept. 2023.

[7] Kamphoefner, Walter D. “Immigrant Epistolary and Epistemology: On the Motivators and Mentality of Nineteenth-Century German Immigrants.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 28, no. 3, 2009, pp. 48. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40543427

[8] Barkin, Kenneth. “Ordinary Germans, Slavery, and the U.S. Civil War.” The Journal of African American History, vol. 93, no. 1, 2008, pp. 70–79. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20064257

Raphael-Hernandez, H., & Wiegmink, P. (2017). German entanglements in transatlantic slavery: An introduction. Atlantic Studies, 14(4), 419–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/14788810.2017.1366009

Anderson, Kristen Layne, Abolitionizing Missouri: German Immigrants and Racial Ideology in Nineteenth-Century America (Antislavery, Abolition, and the Atlantic World),Baton Rouge: Louisiana State Press, 2016

Efford, Alison Clark, “German Immigrants and the Arc of Reconstruction Citizenship in the United States, 1865-1877” (2010). Hist or y F aculty Research and Publications. 285.

https://epublications.marquette.edu/hist_fac/285

Biesele, Rudolph, German Attitude Toward the Civil War, Sep 1, 1995, Texas State Historical Association, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/german-attitude-toward-the-civil-war

[9] Schulten, Susan, How Maps Reveal, and Conceal, History, Progress: A Blog for American History, https://www.oah.org/process-blog/schulten-maps/

[10] J.B. Metzler, Wikipedia, Diese Seite wurde zuletzt am 18. März 2024, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/J.B._Metzler

“Der J.B. Metzler Verlag ist ein traditionsreicher geisteswissenschaftlicher Verlag. Gegründet 1682, ist er einer der ältesten Verlage Deutschlands überhaupt. Verlagsort ist Stuttgart.”

The J.B. Metzler Verlag is a traditional humanities publisher. Founded in 1682, it is one of the oldest publishing houses in Germany. Publishing place is Stuttgart.

J.B. Metzle Publishing Website , https://www.metzlerverlag.de/der-verlag/verlagsprofil

[11] This is pointed out by Mark R. Stoneman in “An 1853 Map for German-Speaking Emigrants,” Migrant Knowledge, January 30, 2022, https://migrantknowledge.org/2022/01/30/an-1853-map-for-german-speaking-emigrants/

[12] Leipziger Zeitung, No. 218, Friday, September 10, 1852 Page 4329. https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/iPxjAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA4329&dq=%22Auswanderer-Karte+und+Wegweiser+nach+Nordamerika%22

[13] Kempter Zeitung, Mar 12 1854, No. 62 Page 254 , https://www.google.com/books/edition/Kemptner_Zeitung/ScVDAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=kemptner%20zeitung%201854&pg=PA254&printsec=frontcover

[14] This is pointed out by Mark R. Stoneman in “An 1853 Map for German-Speaking Emigrants,” Migrant Knowledge, January 30, 2022, https://migrantknowledge.org/2022/01/30/an-1853-map-for-german-speaking-emigrants/

Heinsius, W. (1858). Allgemeines Bücher-Lexikon oder vollständiges alphabetisches Verzeichnis aller … erschienenen Bücher, welche in Deutschland und in den durch Sprache und Literatur damit verwandten Ländern gedruckt worden sind. Germany: Brockhaus. Volume 12 https://www.google.com/books/edition/Allgemeines_Bücher_Lexikon_oder_vollst/4G6LLUh1isUC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22Auswanderer-Karte+und+Wegweiser+nach+Nordamerika%22&pg=PA519&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=%22Auswanderer-Karte%20und%20Wegweiser%20nach%20Nordamerika%22&f=false

[15] Textualis, also known as textura or Gothic bookhand, was the most formal and calligraphic form of blackletter script, widely used for book production in Western Europe from the 12th to 15th centuries. Textualis was most widely used in France, the Low Countries, England, and Germany.

Blackletter, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 30 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackletter

[16] Fraktur, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 8 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fraktur

Draper, Kelly, Fraktur Basics, Aug 17, Backlog Achivists and Historians, https://www.backlog-archivists.com/blog/fraktur

The History of Old German Cursive Alphabet and typefaces, German Girl in America Blog, https://germangirlinamerica.com/old-german-cursive-alphabet-and-typefaces/

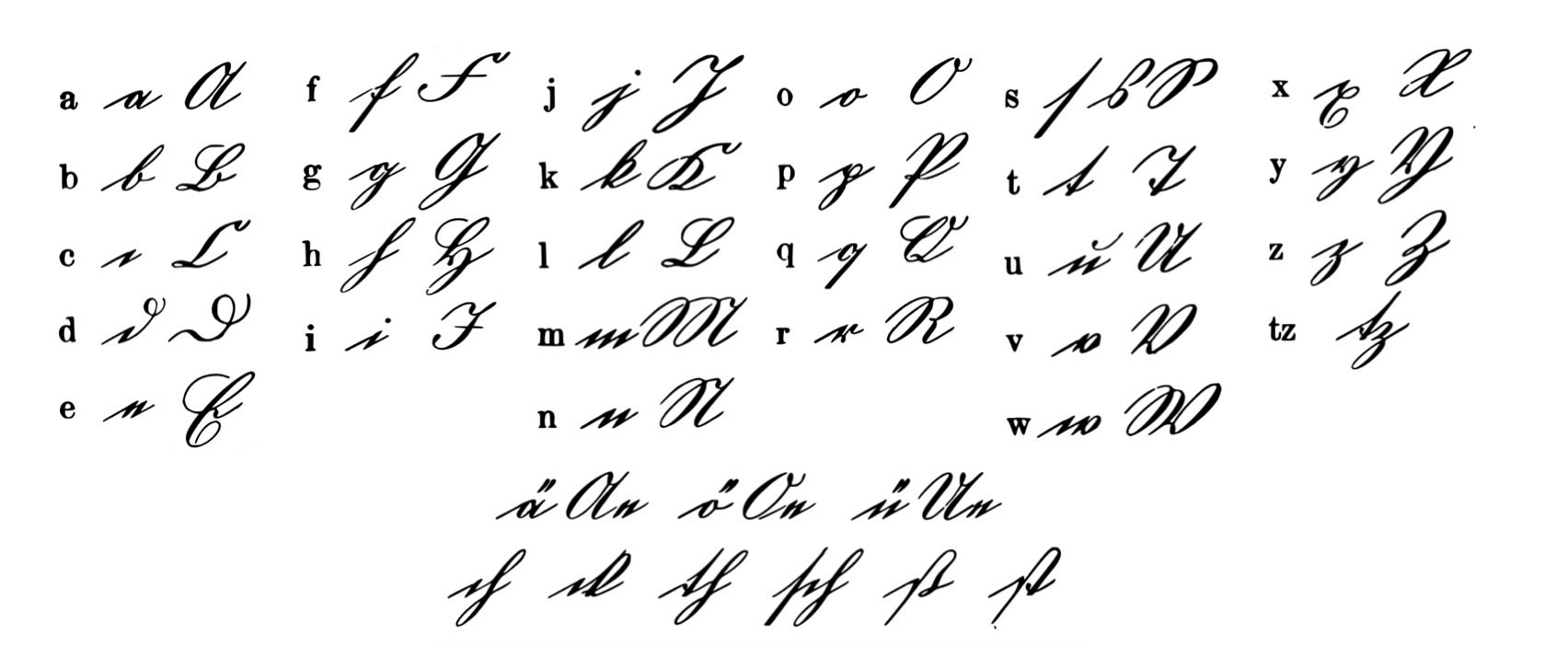

German Fraktur Alphabet

Fraktur, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 8 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fraktur

[17] “Die Entfernung zwischen Europa und Amerika ist im Berhältnisz weit gröszer, als durch die Zeichnung dargestellt werden konnte. Wegen Raumersparnisz muszten hier die beiden Welttheille zusammegerückt werden.”

[18] “Rheinisch” means “Rhenish” and refers to the Rhineland area. So “Kreuzer rheinisch” specifies Kreuzer coins minted and used in the Rhineland currency system. In the Rhineland region of Germany, 1 Gulden was typically equal to 60 Kreuzer. In the 18th century, common larger denominations included the Reichsthaler (worth 90 Kreuzer rheinisch), the Gulden (60 Kreuzer rheinisch), and the Batzen (4 Kreuzer rheinisch).

The following provides a brief discussion of the currencies mentioned in the map.

“From 1837: the Prussia-led Zollverein customs union led to a more vigorous transition into the Prussian currency standard, with North German thalers being replaced by lower-valued Prussian thalers worth 14 to a Cologne Mark of fine silver (or 16.704 g), and with each thaler now divided into 30 silbergroschen. The Prussian thaler was also fixed at 13⁄4 South German gulden.”

Thaler, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 9 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thaler

The Rhenish kreuzer was a common small silver coin used for centuries in the Rhineland and nearby regions of Germany, with its value defined relative to larger units like the albus, groschen, and gulden. The kreuzer’s role was as a convenient everyday coin for smaller transactions.

The Taler – the Trade Currency of the 16th Century, Money Museum, https://moneymuseum.com/pdf/yesterday/05_Modern_Times/01%2804%29%20The%20Taler%20the%20Trade%20Currency%20of%20the%2016th%20Century.pdf

Albus (coin), Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 10 November 2023 , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albus_%28coin%29

South German gulden, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 12 August 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_German_gulden

Medieval Currencies, Money Museum, https://www.moneymuseum.com/pdf/yesterday/04_Middle_Ages/19%20Medieval%20Currencies.pdf

“In the German-speaking world, the groschen was usually worth 12 pfennigs … The later Kreuzer, a coin worth 4 pfennigs arose from the linguistic abbreviation of the small Kreuzgroschen.”

Groschen, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 6 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Groschen

[19] Comparative-Time Table, Showing the Time at the Principal Cities of the United States, compared with Noon at Washington, D. C., 1868, Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum, http://cprr.org/Museum/Ephemera/Comparative_TT_1868.html

[20] Atack, Jeremy & Bateman, Fred & Margo, Robert. The Transportation Revolution Revisited: Towards a New Mapping of America’s Transportation Network in the 19th Century. Uploaded 12 Jan 2015, preliminary paper, ResearchGate, Footnote 27, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-Railroad-Network-in-1850-1860-1870-and-1880-Mapped-Against-1860_fig3_267239718

[21] The major railroads took it upon themselves to solve the problems caused by the jumble of local times. By collectively adopting a standard time zone system in 1883, they paved the way for the nationwide standardization of time.

Time Zone, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 16 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Time_zone

Railway Time, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 4 January 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Railway_time

History of Time in the United States, This page was last edited on 6 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_time_in_the_United_States

Barass, Karen, Time Zone Origins, Infoplease, Aug 24, 2020, https://www.infoplease.com/calendars/history/time-zone-origins

Standardizing time: Railways and electric telegraph, 4 Oct 2018, sciencemuseum.org,

When the Standardization of Time Advanced in America, Dec 19, 2016, Smithsonian, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-standardization-time-changed-american-society-180961503/

Buckle, Ann, Why Do We have Time Zones, timeanddate, https://www.timeanddate.com/time/time-zones-history.html

[22] Disturnell, John, Disturnell’s railroad, steamboat and telegraph book being a guide through the United States and Canada : also giving the ocean steam packet arrangements, telegraph lines and charges, list of hotels, &c. : with a map of the United States and Canada showing all the canals, railroads, &c, July 1851, New York: J. Disturnell, Page 43, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100280015/Home

For a fairly complete list of John Distunrell’s books, see: Online Books by John Disturnell, https://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=Disturnell%2C%20John%2C%201801%2D1877

[23] Ibid, Page One

[24] Paris-Est–Strasbourg-Ville railway, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 14 June 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris-Est–Strasbourg-Ville_railway

Direction Générale des Ponts et Chaussées et des Chemins de Fer, Statistique centrale des chemins de fer. Chemins de fer français. Situation au 31 décembre 1869 (in French). Paris: Ministère des Travaux Publics, 1869, pp. 146–160

[25] Atack, Jeremy & Bateman, Fred & Margo, Robert. The Transportation Revolution Revisited: Towards a New Mapping of America’s Transportation Network in the 19th Century. Uploaded 12 Jan 2015, preliminary paper, ResearchGate, Page 15, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-Railroad-Network-in-1850-1860-1870-and-1880-Mapped-Against-1860_fig3_267239718

[26] Modified version of Map originally from ULamm, France1860railways.png, 24 Aug 2009, Wikimedia Commons, This page was last edited on 8 June 2022 , https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:France1860railways.png

[27] The map is a portion of the map: Figure 3-bis: Postal roads and main cities and towns in 1833 in Verdier, Micolas and Anne Bretagnolle. Expanding the Network of Postal Routes in France 1708-1833. histoire des réseaux postaux en Europe du XVIIIe au XXIe siècle, May 2007, Paris, France. pp.159 – 175. https://shs.hal.science/halshs-00144669/document

[28] Boyd, James D., An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, Page 123 https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

[29] Mark R. Stoneman, “An 1853 Map for German-Speaking Emigrants,” Migrant Knowledge, January 30, 2022, https://migrantknowledge.org/2022/01/30/an-1853-map-for-german-speaking-emigrants/

[30] Atack, Jeremy & Bateman, Fred & Margo, Robert. The Transportation Revolution Revisited: Towards a New Mapping of America’s Transportation Network in the 19th Century. Uploaded 12 Jan 2015, preliminary paper, ResearchGate, Page 20 https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-Railroad-Network-in-1850-1860-1870-and-1880-Mapped-Against-1860_fig3_267239718

[31] Page, Thomas W. “The Transportation of Immigrants and Reception Arrangements in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 19, no. 9, 1911, pp. 736. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1820349

[32] German Americans, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 17 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_Americans

[33] Maine nor New Hampshire were top destinations. There were a couple notable German immigrant communities established there by the mid-1800s, especially in Waldoboro, Maine which retained its German heritage. Between 1740 and 1753, approximately 1,500 Germans immigrated to what was then known as Broad Bay Plantation (now Waldoboro, Maine). They were recruited by Samuel Waldo with promises of land, funding, and freedom.

By the mid-1800s, Waldoboro was one of the only two named German settlements in Maine according to Traugott Bromme’s emigrant guidebook, the other being Biddeford. In addition to Waldoboro, some other Maine towns were named after German hometowns by early settlers, such as Hanover, Bremen, and Dresden.

German Jews also immigrated to Maine, arriving in Bangor as early as 1829 and establishing the Bangor Hebrew Center in 1839. The Congregation Ahawas Achim was founded there in 1849.

Bland, L., Traugott Bromme and the State of Maine, Maine History, Jan 1 2015, Volume 49, Number ! The Maine Melting Pot, Page 102 – 112, https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1126&context=mainehistoryjournal

The Germans of Waldoboro, Meander Maine, https://meandermaine.com/tale/the-germans-of-waldoboro/

German Americans, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 17 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_Americans

Welcome to Documenting Maine Jewry, a collaborative history and genealogy of Maine’s vibrant Jewish communities, https://mainejews.org

Maine Historical Society, Copy of a plan of lands on the west side of Madomack River, Waldoboro, 1774, Maine Memory Network, https://www.mainememory.net/record/102767

400 Years Waldo Patent and German immigrants, Maine Memory Network, https://www.mainememory.net/sitebuilder/site/2623/slideshow/1635/display?format=list&prev_object=page&prev_object_id=4227&use_mmn=1

Thompson, Garret W., The Germans in Maine (Waldoboro’, Lincoln County, Maine), http://files.usgwarchives.net/me/lincoln/waldoboro/settlers/german/sj5p140.txt

[34] Disturnell’s New Map of the United States and Canada Showing all the Canals, Rails Roads, Telegraph Lines and principal Stage Routes, Drawn by Henry A Burr, New York: J. Disturnell, 1850, Online Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/98685344/

Disturnell’s 1850 Map

[35] The map is a blown up portion of “Disturnell’s New Map of the United States and Canada” that focuses on Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. I have added the legend from the original map to provide an idea of what each of the types of lines represent. I have also indicated where each of the towns that Zimmermann identified in his map are located on Disturnell’s map.

Other American Maps that can be used to provide comparisons with Zimmermann’s map are mentioned below. Distunell’s map, however, is a excellent map to utilize since it portrays road, rail and waterways.:

Historic Railroad Map Of The Northeastern United States – 1853 https://www.worldmapsonline.com/historic-railroad-map-of-the-northeastern-united-states-1853

Goldthwait, J. H., Railroad map of New England & eastern New York complied from the most authentic sources, Boston : Redding & Co. ; New York : Clark, Austin & Co., 1849, Library of Congress, Library of Congress Control Number 98688377, https://lccn.loc.gov/98688377

Snow & Wilder, Hitchcock, DeWitt C., Map of railways in New England and part of New York; Boston, [1847] engraved by D. C. Hitchcock for the Pathfinder Railway Guide, Library of Congress Control Number 98688376, Library of Congress, https://lccn.loc.gov/98688376

[36] Rudolph Vecoli, European Americans: From Immigrants to Ethnics, Section I : Immigrants, Ethnics, Americans, Cleveland Ethnic Heritage Studies, Press Books, Cleveland State University 1976. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/ethnicity/chapter/european-americans-from-immigrants-to-ethnics/

James Boyd in his Introduction to his PhD Dissertation , The Limits to Structural Explanation, provides a good overview of the historical approaches that have been used for explaining German migration to America, see:

James D. Boyd, An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

Helbich, Wolfgang. “German Research on German Migration to the United States.” Amerikastudien / American Studies, vol. 54, no. 3, 2009, pp. 383–404. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41158447

Günter Moltmann, “Migrations from Germany to North America: New Perspectives.” Reviews in American History, vol. 14, no. 4, 1986, pp. 580–96. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2702202

Marianne S. Wokeck, Trade in Strangers: The Beginnings of Mass Migration to North America, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999

Häberlein, Mark. “German Migrants in Colonial Pennsylvania: Resources, Opportunities, and Experience.” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 50, no. 3, 1993, pp. 555–74. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2947366

Philip Otterness, Becoming German, The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004

Donna Merwick, Possessing Albany, 1630-1710: The Dutch and English Experiences, Cambridge, 1990

Thomas Burke, Mohawk Frontier: The Dutch Community of Schenectady, New York 1660-1710, Ithaca, 1991, Page 213

Natalie Zemon Dennis, Cultivating a Landscape of Peace: Iroquois-European Encounters in the Seventeenth-century America, Ithaca, 1993

Francis Jennings, Ambiguous Iroquois Empire, New York, 1984

The Palatine Germans, The National Park Service, Updated October 8, 2022 https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/the-palatine-germans.htm

Aaron Spencer Fogleman, Hopeful Journeys: German Immigration, Settlement and Political Culture in Colonial America, 1717-1775, Philadelphia: University of pennsylvania Press 1996

Philip Otterness, Becoming German, The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York,Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004

Cobb, Sanford Hoadley. The Story of the Palatines: An Episode in Colonial History. United Kingdom, G. P. Putnam’s sons, 1897. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Story_of_the_Palatines/eUgjAAAAMAAJ?hl=en

Brink, Benjamin Myer. “The Palatine Settlements” Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association, vol. 11, 1912, pp. 136–43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42889955. Accessed 27 May 2023.

Ellsworth, Wolcott Webster. “The Palatines in the Mohawk Valley.” Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association, vol. 14, 1915, pp. 295–311. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42890044. Accessed 27 May 2023.

Diefendorf, Mary Riggs. The Historic Mohawk. United Kingdom, Putnam, 1910. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Historic_Mohawk/ziIVAAAAYAAJ?hl=en

Benton, Nathaniel Soley. A History of Herkimer County: Including the Upper Mohawk Valley, from the Earliest Period to the Present Time ; with a Brief Notice of the Iroquois Indians, the Early German Tribes, the Palatine Immigrations Into the Colony of New York, and Biographical Sketches of the Palatine Families, the Patentees of Burnetsfield in the Year 1725 ; and Also Biographical Notices of the Most Prominent Public Men of the County ; with Important Statistical Information. United States, J. Munsell, 1856. https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_History_of_Herkimer_County/G1IOAAAAIAAJ?hl=en

[37] Burnett and Ken Luebbering, German Settlement in Missouri: New Land, Old Ways, Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1996

[38] Hungerford, Edward. “Early railroads of New York” New York History, vol. 13, no. 1, 1932, pp. 75–89. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24469729

Ellis, David Maldwyn, “Rivalry between the New York central and the Erie Canal” New York History, vol. 29, no. 3, 1948, pp. 268–300. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43460288

Rapp, Marvin A., “New York’s Trade on the Great Lakes, 1800 -1840.” New York History, vol. 39, no. 1, 1958, pp. 22–33. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23153562

Fairlie, John A. “The New York Canals.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 14, no. 2, 1900, pp. 212–39. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1883769

North, Edward P. “The Erie Canal and Transportation.” The North American Review, vol. 170, no. 518, 1900, pp. 121–33. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25104942

Whitford, Noble E. “Effects of the Erie Canal on New York History.” The Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association, vol. 7, no. 2, 1926, pp. 84–95. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43566182

Jackson, Harry F., “The Erie Canal.” Scholar in the Wilderness: Francis Adrian Van Der Kemp, Syracuse University Press, 1963, pp. 268–82. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv64h7kc.25

Shaw, Ronald E. “Canals in the Early Republic: A Review of Recent Literature.” Journal of the Early Republic, vol. 4, no. 2, 1984, pp. 117–42. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3122718

Burd, Camden. “A New, Historic Canal: The Making of an Erie Canal Heritage Landscape.” IA. The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology, vol. 42, no. 2, 2016, pp. 23–34. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26643089

[39] Gerlach, Russel, The German Presence in the Ozarks, OzarksWatch, Vol III, No.1, Summer 1989, https://thelibrary.org/lochist/periodicals/ozarkswatch/ow301h.htm Page, Thomas W. “The Transportation of Immigrants and Reception Arrangements in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 19, no. 9, 1911, pp. 736. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1820349 .

Reinhard Wittmann, Ein Verlag und seine Geschichte: Dreihundert Jahre J. B. Metzler Stuttgart (Stuttgart: J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1982), 411.

Dolindel, Sonja, , Off to New York ! A story of immigration in the 19th century in pictures, 16.12.2021, Kultur und Wissen online, Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek, https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/content/blog/ab-nach-new-york-eine-geschichte-der-auswanderung-im-19-jahrhundert-bildern?lang=en

Zimmermann, Gotthelf. Auswanderer-Karte und Wegweiser nach Nordamerika. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler’schen Buchh, 1853. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/98687132/

[40] Dahmann, Donald C., Presenting the Nation’s Cultural Geography, General Maps Collection, Articles and Essays, Nationals Atlases. Library of Congress, https://web.archive.org/web/20201109045038/https://www.loc.gov/collections/general-maps/articles-and-essays/national-atlases/presenting-the-nations-cultural-georgraphy/

[41] Ibid, Dahmann, Donald C., Presenting the Nation’s Cultural Geography

[42] A. de Witzleben, German Population 9th Census, Page 325, in Francis A Walker, Superintendent of Census, Ninth census – Volume I, The Statistics of the Population of the United States, Washington, Government Printing Office, 1872 https://www.google.com/books/edition/Ninth_Census_volumes/0ngZm56S-7sC?hl=en&gbpv=1

For a 1890 version, see: Gannett, Henry, 50. Density of Distribution of the Natives of the Germanic Nations, Plate 20, Statistical atlas of the United States, based upon the results of the eleventh census, United States. Census office. 11th census, 1890 https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3701gm.gct00010/?sp=40

[43] The “German belt” refers to the region of the United States where large numbers of German immigrants settled in the 19th century, especially from the 1840s to early 1900s. This area stretched from Pennsylvania across the Midwest to the Great Plains states. It included states like Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, Kansas, and parts of the Dakotas. The highest concentrations were in the Upper Midwest.

[44] Midwestern United States, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 15 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Midwestern_United_States

[45] Kamphoefner, Walter, The German Component to American Industrialization, Jan 27, 2014, Immigrant Entrepreneurship: 1720 to the Present, , German Historical Institute, http://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entries/the-german-component-to-american-industrialization/

Bergquist, James M. “German Communities in American Cities: An Interpretation of the Nineteenth-Century Experience.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 4, no. 1, 1984, pp. 9–30. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27500350

[46] Schulten, Susan ,A History of America in 100 Maps, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2018, Page 8