In addition to local community influences and past traditions for emigrating, John Sperber’s choices for emigrating from Baden to the United States were greatly influenced by the shifts in dominance of European ports that managed international trade after 1815. His decision to emigrate to the United States was also influenced by available inland routes to European ports.

This is the third part of his story of emigration. It assesses the three major inland pathways to European ports that John had options to consider. Since it is not 100% absolutely certain that John sailed on the Germania from Le Havre, I have provided the results of my historical research on the the relative accessibility of the three major routes John may have considered to make his voyage to the United States. This part of the story is a bit lengthy with a number of references. I have provided many references for readers who are interested to learn more about the development of roads, waterways and railways at the time of John Sperber’s journey

The Journey of John Wolfgang Sperber: A Four Part Story

The first part of the story provides an overview of the family legacy John Sperber established in his new homeland, an historical background on where John was from in Baden, Germany, the influences on his migration to the United States, and the historical evidence of his departure and arival to America.

The second part of John Sperber’s story describes his journey from Baden-Baden to Le havre based on historical evidence and historical accounts.

The fourth and final portion of John Sperber’s story is about his coming to America and establishing a new life and family in the Johnstown and Gloversville, New York area.

Influences on Choosing a Port of Embarkation

In his late twenties, John Sperber was deciding when and where he would make a life altering decision to move to the United States. Like many who made similar decisive decisions to emigrate from Germany, we know little behind his decisions, why he may have left Baden and the characteristics of his local community in Baden. As discussed in the first part of this story, there are a range of push and pull factors that influenced his decision.

John Sperber’s choice of a specific inland route to a major European port to start his journey to the United States was influenced by:

- established roadways that linked many of German states and France to northern European ports;

- the continental waterways associated with these European ports that emptied into the English Channel and North Sea (natural and man-made); and

- the quickly emerging rail lines in the German states and France.

“In choosing a route … the intending emigrant selected a port of departure mainly with reference to its accessibility from his home, though he was obliged to consider to some extent the likelihood of his finding there with-out long delay some ship clearing for America. As emigration increased, however, there was a growing tendency for it to be concentrated at certain points. This was because later emigrants learned from the experience of those who had preceded them that some ports offered greater facilities than others, and because the merchant houses and ship-owners of some cities were more active in seeking the business of passenger transportation than were those of other places.” [1]

German trans-Atlantic emigration in the nineteenth century differed considerably from emigration during the previous century.

Most German immigrants in the 1700s came from the southwestern states of the Holy Roman Empire, particularly the Palatinate, Baden, and Württemberg areas along the Rhine River. The journey to America involved obtaining permission from local authorities, paying a fee to emigrate, and traveling down the Rhine River to the Dutch port of Rotterdam. The transatlantic voyage lasted seven to fourteen weeks in crowded conditions. Many German immigrants arrived in Philadelphia and to a lessor extent New York City. [2]

In the nineteenth century, a large number of German migrants continued to depart from the Palatinate, Baden, and Württemberg areas. However, different ports of departure were used. The Atlantic migration … (after 1816/1817)… was conducted by different models and networks than in the previous century. … (T)he majority departed from ports such as Le Havre, Bremen, Liverpool, and latterly Hamburg. New logistical networks, migration laws, and pronounced subsistence crises quickly brought more German regions into this newly expansive Atlantic migration.” [3]

Other Migration Influences

Other factors may have influenced John’s decision (as well as the decisions of the members of the Fliegel family) to immigrate to the United States. In addition to the transportation infrastructure at the time, the following factors undoubtably played a role:

- the cost and difficulty of travel to a given port;

- the ship fares and transportation costs to America from a given port;

- the amount of estimated time required to travel to a given port;

- the influence of information garnered from the experiences of other German emigrants;

- the influence of prior generations of families and individuals immigrating from their respective local areas;

- the effects of local community support to emigrate from Baden; and

- the influence of the German press and publications on travel options to a specific port and United States destinations.

These ‘other’ migration factors are discussed in stories after this one.

A Shift in European Ports of Departure

The shift in German immigration ports before and after 1815 can be attributed to a combination of economic, political, and technological factors that influenced migration patterns and choices of embarkation ports for emigrants heading to the United States.

Prior to 1815, German emigrants primarily used ports in the Netherlands, such as Rotterdam, for their departure to the New World. This preference was due to several reasons:

- Geographical Proximity and Accessibility: The Rhine River and its German tributaries ( the Main and the Neckar rivers) served as a natural transportation route for emigrants from the southwestern parts of Germany, facilitating their journey to Dutch ports. [4]

- Established Migration Networks: Early German emigration patterns established a precedent for using Dutch ports, supported by networks of merchants and river boatmen who facilitated the migration process down the inland waterways. [5]

- Economic and Political Conditions: The period leading up to 1815 was marked by economic hardships, including crop failures and the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, which spurred emigration. Dutch ports were accessible and had long established connections to America, making them a logical choice for emigrants seeking better opportunities overseas. [6]

The shift away from Dutch ports towards the European ports of Havre, Bremen and Hamburg, as well as other European ports, after 1815 was influenced by several key developments:

- Technological Advances: The introduction of steamships in the 1810s onward on the inland waterways [7] and the expansion of railroads in the 1840s and 1850s significantly reduced travel time and costs, making it easier for emigrants to reach and prefer ports that offered regular packet ship lines and more direct services to the United States, such as Bremen, Hamburg, and Le Havre. [8]

- Economic Factors: The agricultural depression in regions like Baden and Württemberg, coupled with unemployment and the impact of the failed German Revolution of 1848, made emigration an attractive option. Ports that offered lower passage costs and were actively seeking to attract emigrants, like Havre, Bremen and Hamburg, became more popular. [9]

- Legislative Changes and Migration Policies: Changes in migration policies, including the enforcement of legislation that required migrants to have valid contracts and the exclusion of economically distressed migrants, directed the flow of emigration towards ports that were better regulated and prepared to handle solvent emigrants, such as Bremen and Hamburg. [10]

- The refinement of large scale mercantile practices and networks between American and European ports and inland commercial networks in both continents played a significant role in reshaping German migratory paths to the United States during the 19th century. [11]

“A large scale peasant emigration was possible only when the European demand for American products was so steady as to insure an adequate supply of vessels and when the tentacles of trade pushed inland to facilitate transportation on land (in Europe). It was a commercial expansion of this nature that in the 1830’s bridged the Atlantic and opened the doors of America to those countless individuals who must rely on their own resources, knowledge and courage for the great adventure.” (emphasis is mine) [12]

In the 1830s, “the German who smoked used American tobacco, the factories of Switzerland and France spun American cotton, and British houses and ships drew their timber from the Candian forests. To satisfy these wants, steamboats threaded their way up and down European rivers, long-pointed barges glided through the canals, heavily laden wagons crawled along endless stretches of newly built roads, while on the Atlantic thousands of sails bound the two continents in a mutual dependance which no legislation could thwart and no wars destroy.” [13]

European Ports in the mid 1800s

A port’s size and significance were, first of all, determined by the radius (and value) of its interior connections. Ports with relatively poor hinterland extension, like Marseille, lagged behind ports whose hinterlands opened to them the vast flows generated by producer and consumer territories. To a certain extent hinterlands were a fact of nature, particularly for ports located on rivers. Traffic along the Elbe flowed through Hamburg. But traffic along the Rhine could run, via waterway connections, through a number of possible ports. Hinterlands were thus constructed relationships, most notably but not exclusively, out of transportation networks that exploited or overcame nature and joined interiors to desired points. …

“The relationship between ports and their hinterlands, however, was never simply a matter of contouring transportation networks to physical geography. Power intruded on hinterland connections or rearranged them.” [14]

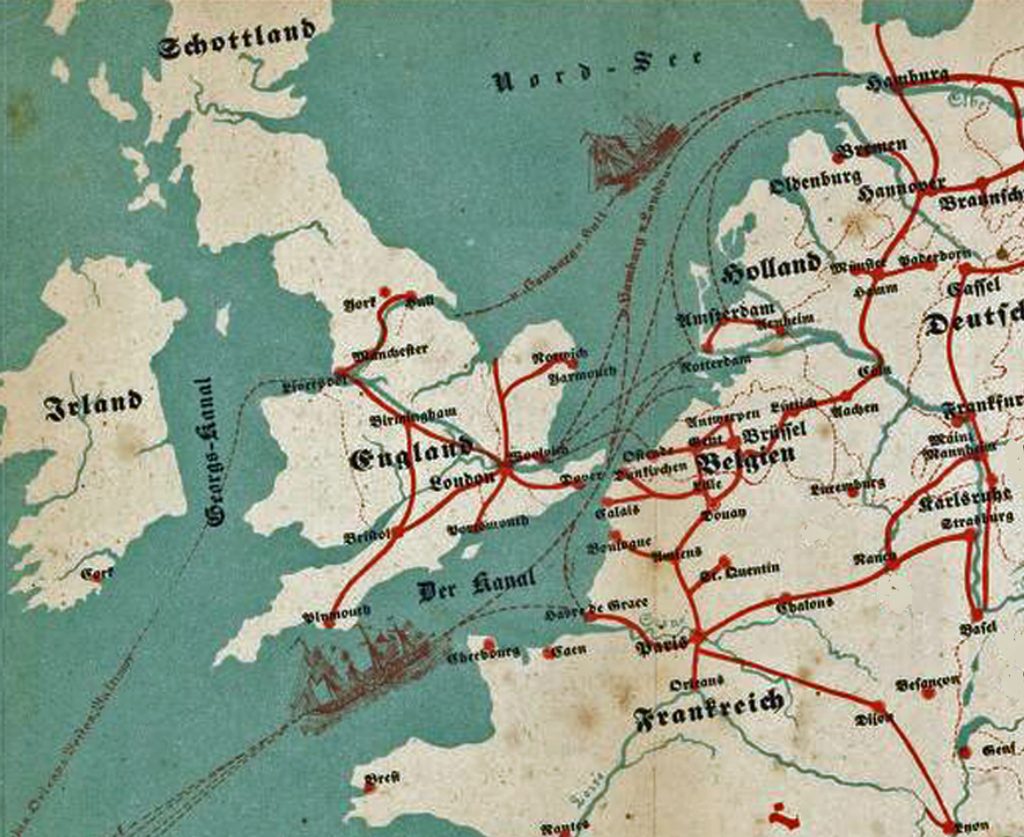

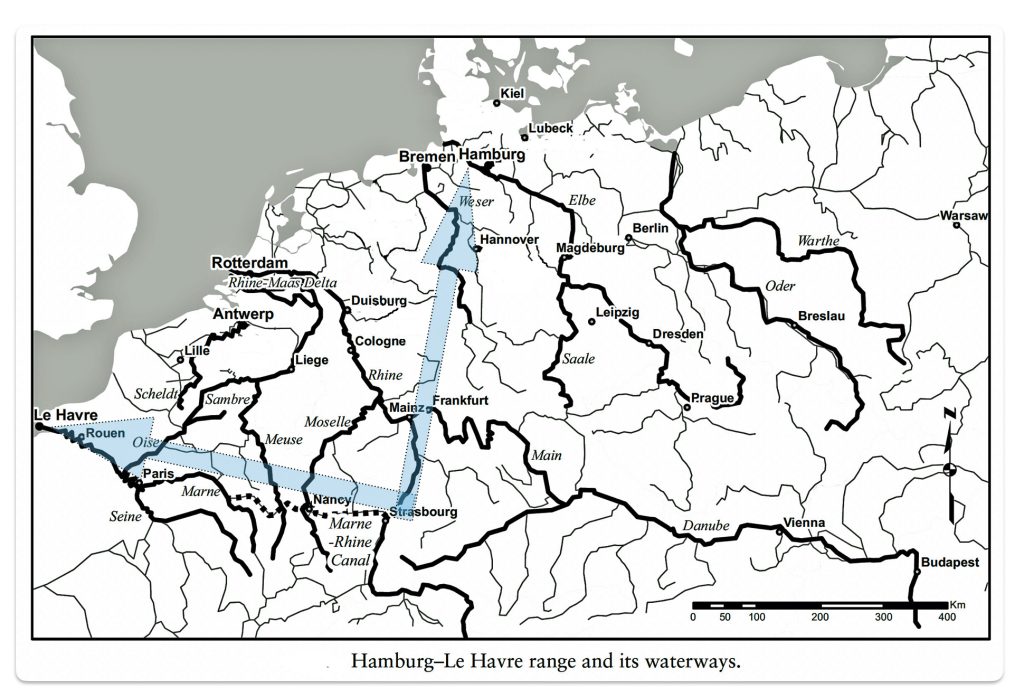

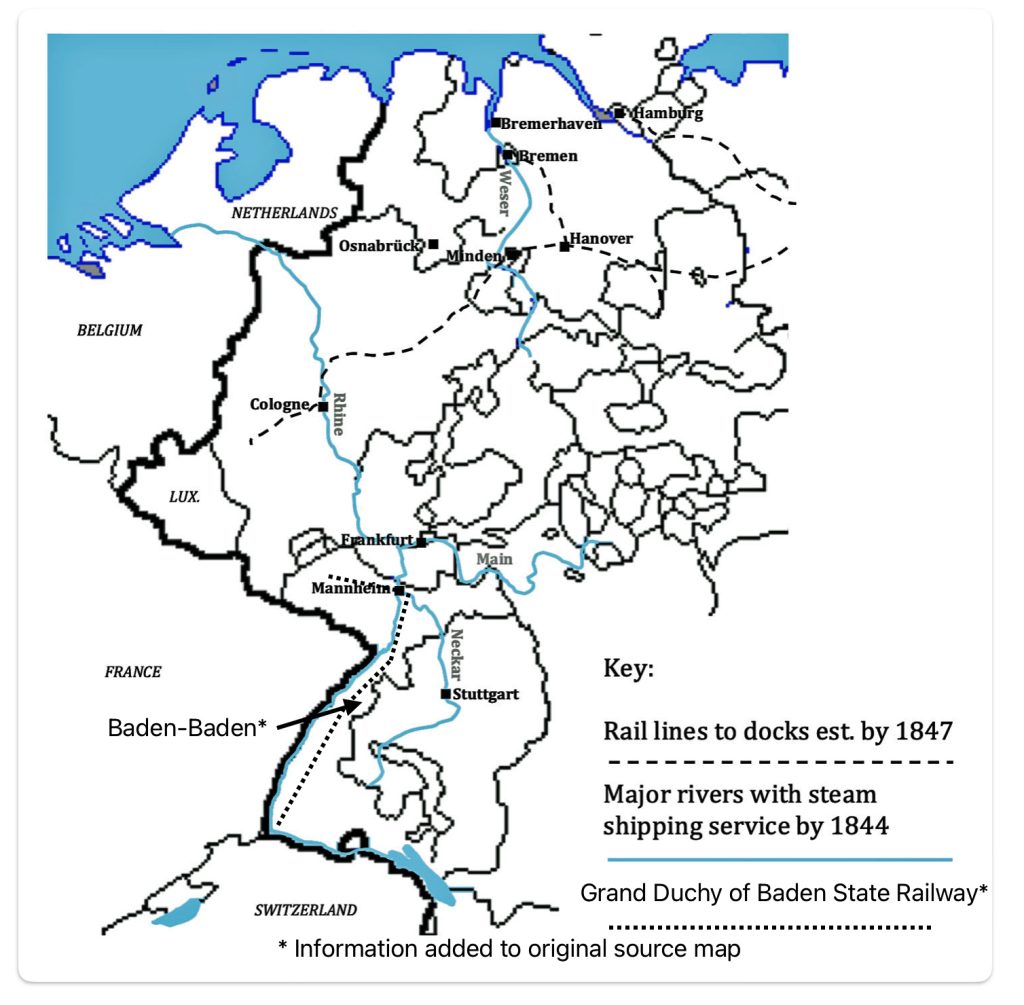

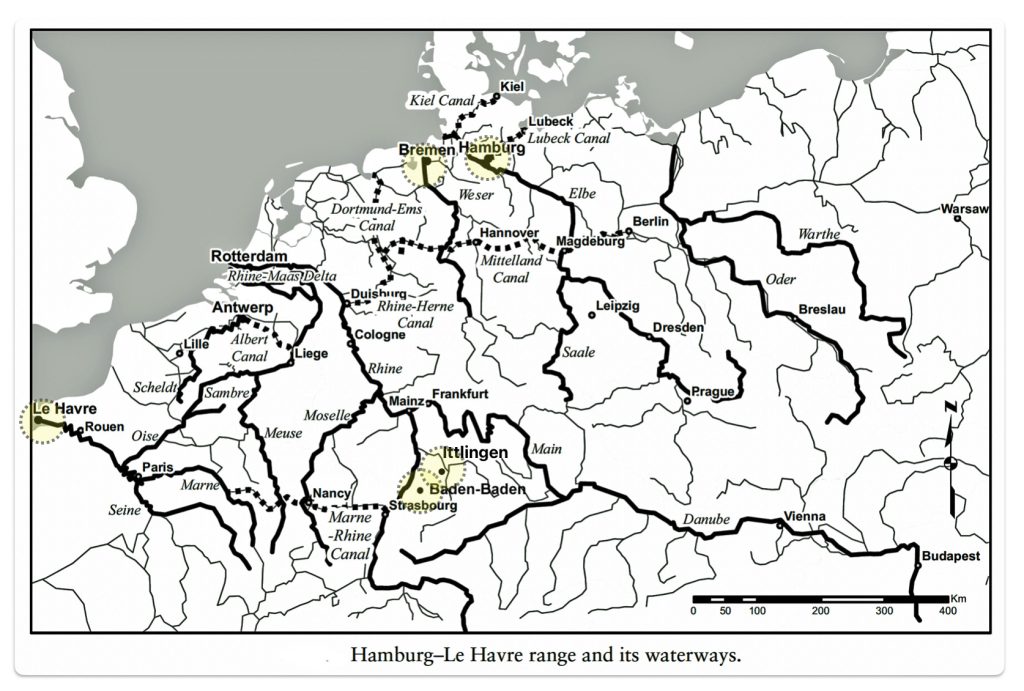

A major development on the north-western coast of the European continent in the 1800s was the emergence of a powerful and influential range of ports between the mouth of the Seine and Elbe River on the German northern coast. As reflected in map one, the prominence of this so-called “Northern Range” was based on its location at the interface between the North Atlantic maritime route and the expansive inland European waterways.

For reference, Baden-Baden and Ittlingen are highlighted on map one to indicate where John Sperber and the Fliegel Family respectively lived. The principal ports of Havre, Bremen and Hamburg are also highlighted.

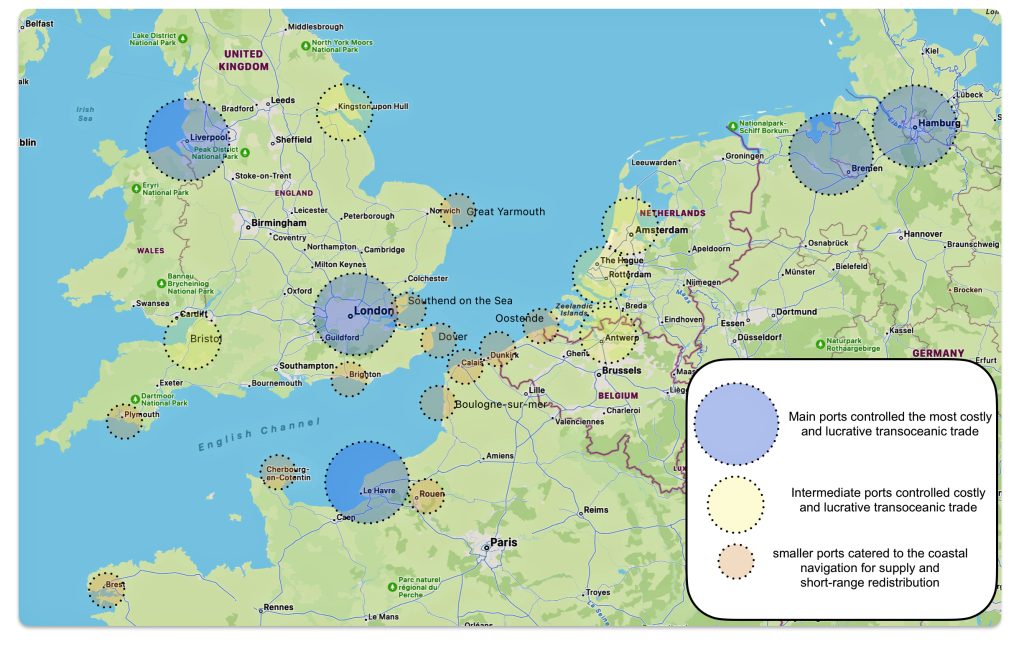

“At the time when ports had no or only very few facilities, it is striking to note the profusion of small, scattered port sites, a situation described by Gérard Le Bouëdec as “poussière portuaire” (literally “port dust”). In the French province of Brittany alone there were 123 identifiable harbours in the 16th century; by the 18th century there were only around 90. This reduction of the number of ports was accompanied by a process of concentration within a few major port sites, leading to the creation of large zones of maritime activity.”

“London, the great international warehouse, remained the world’s biggest port in the 19th and early 20th century but faced increasing competition from the ports on Europe’s North-Western coast, known collectively as the Northern Range. Stretching from Le Havre to Hamburg, … .” [15]

Map One: Contemporary View of the Northern Range Ports and Hinterland Waterways [16]

The Northern Range consisted of major and minor ports between Europe and the United States in the northern hemisphere. The ports on European side of the northern range were located at the end of large estuaries at the gateways to great river basins. A division of power and specific aspects of trade came into being between the larger and smaller ports. The main ports controlled the volume of the most costly and lucrative transoceanic trade and immigrants while the other nearby smaller ports catered to the coastal navigation for supply and short-range redistribution of goods and transportation of people. [17]

The hierarchy of transatlantic ports was also reflected in the popularity of ports for German immigration. In 1850, two years after Catherine Fliegel emigrated to America and two years before John Sperber left for America, Havre and Bremen were roughly equal in attracting emigrants. Emigrants departing from Havre and Bremen were roughly equal. However, it is interesting to note in table one that virtually all of the immigrants departing from Havre landed in New York City. German immigrants departing from Bremen had a more diverse itinerary. While ninty-eight percent had the United States as their destination, only 53 percent landed in New York City. German immigrants from Hamburg had a diverse range of destinations: to New York City and various other American ports as well as Québec, Brazil, Valdivia, Valparaiso and Australia. [18]

Table One: German Emigrants by Port of Departure in 1850

| Port | Number of Emigrants | New York as Destination |

|---|---|---|

| Havre | 25,824 | 24,016 * |

| Bremen | 25,169 | 13,508 |

| Hamburg | 13,508 | 5,025 |

“The completion of the German railway system and the great expansion of steam navigation in the Hanseatic cities eventually deprived Havre of her predominance in the business, but she remained an important port of departure as long as there was a large emigration from the region to which she was an accessible outlet.” [19]

Map two depicts the European side of the Northern range. Reflected on the continental side of the channel is the dynamic between the large and intermediate sized ports of Le Havre-Rouen, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Antwerp and Bremen and Hamburg. The smaller ports on the continental side were Berest, Cherbourg, Boulogne, Calais and Oosteride. On the English side of the channel, London, Liverpool and Bristol were the dominant ports while Plymouth, Brighton, Dover, Southend, Great Yarmouth and Kingston-Hull played supporting roles. [20]

Map Two: The Relative Influence of Northern Range Ports Mid 1800s

It is interesting to see this graphic depiction of the relationship between the ports in an early 1853 pamphlet for German immigration. Map three is portion of a map from a German immigration pamphlet. It depicts the northern range ports in terms of possible emigration routes. The map also depicts inland routes to the major ports of embarkation. The map also indicates the inland routes that immigrants can take to reach each of these ports of embarkment. [21]

Map Three: The Northern Range Ports and German Emigration

John Sperber had largely three alternative routes to consider for his journey to America: Hamburg, Bremen and Havre. “By 1842 La Havre, Bremen and Hamburg had become the sluice gates through which the rising flood of Continental immigration moved.” [22]

To a lessor extent German immigrants also used other European ports to embark to America. Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Antwerp were also points of departure. Liverpool was also used as a port for Germans traveling to the United States. The “Hull route” for German immigration involved traveling from Hamburg to Hull, England by sea, then crossing England by train to Liverpool, and finally embarking on a transatlantic voyage to North America. At Hamburg, travel agencies sold tickets at Hull German guides who also spoke English met and conducted them across the island to departing ships from Liverpool. [23]

Until the railway revolution gathered momentum in the late 1840s, the relative importance or strength of a given port was based on their connections with river and canal traffic to the inland hinterlands. Road traffic was also relied upon for transportation to major ports. The use of waterways over road transport was a result of lower costs associated with river transport as compared to road transport. Railway development in the mid to late 1840s and 1850s onward changed this dynamic.

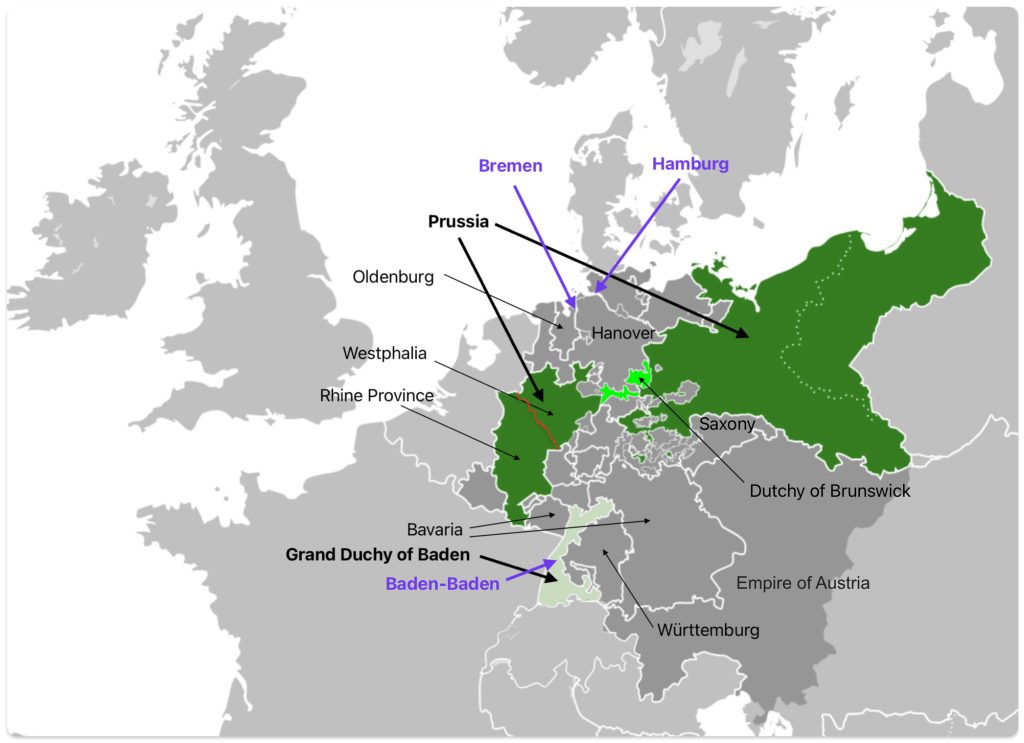

The ‘top three’ ports for German immigration all reside at the mouths of rivers. Le Havre is located on the English Channel at the mouth of the Seine River in France. The two largest emigration ports from Germany to the New World were the Free Hanseatic cities of Bremen and Hamburg, Germany. Bremen is the port city for the Weser River and the Westphalia region. Hamburg is the primary port on the Elbe River, the watery highway of Central Germany.

Map Four: Three Popular Embarkment Ports Used by German Immigrants Between 1840-1855 in Relation to John Sperber’s Point of Origin

Map Four illustrates the three port cities in relation to where John Sperber started his inland journey in Baden-Baden in the Grand Duchy of Baden. The map illustrates in white outlines the political boundaries of the Germanic states and other countries around 1850-1852. The dotted line signifies the boundaries of the German Confederation of states. While John made his trip to American in the early 1850s, the political boundaries did not change much, if any, between the mid 1840s to 1860. [24]

It is a simplified map but it puts into relief the complexity of traveling northward to Bremen or Hamburg through a myriad of independent Germanic states from Baden to the northern independent cities of Hamburg and Bremen. As stated in part one of this story, each of these German states regulated their own economic, political and social affairs.

At the time of his emigration in 1852, the general route to Havre posed less of a challenge traversing different states, roadway conditions, and rail lines and river – canal transportation. The ‘Havre – Strasburg’ route was also a known route, utilized by German immigrants from John Sperber’s area since the late 1820’s.

“After the fall of Napoleon (1815), Havre became the chief port of departure for continental Europe, and it retained its supremacy for more than a generation. The Swiss and South Germans arrived there overland or by sail from Cologne; and many came in coasting vessels from North Germany, and even from Norway for transshipment to America. In 1854 the German emigration by way of Havre exceeded that from Bremen by twenty thousand; while Bremen was ahead of Hamburg by twenty-five thousand, and Hamburg in turn led Antwerp by a like number.” [25]

After 1815 many of the German states pursued their own interests and approaches in infrastructure development (roadways, waterways and railways), tariff and taxation policy, official support for the trade industries and in supporting emigrating Germans. [26] This consequently affected the pattern and uneven growth of trade, transportation networks and economic development between the various German states. The uneven rate of infrastructure development also affected German immigration patterns to various ports and the relative dominance of specific ports for immigration to the United States. [27]

In addition to the different rates of infrastructure development, “(i)n the context of the competition between emigration ports in Europe, the two German ports were latecomers since their hinterlands at first provided few or no migrants. In the north, Scandinavian migrants left through numerous small ports and through Gothenburg or Copenhagen. In Central Europe, migration began in the south, in Baden, Wuerttemberg and the German-speaking areas of Switzerland. From these, the cheapest route was by boat down the river Rhine to the Dutch and Belgian ports, and later with the coming of trains through France to Le Havre.” [28]

In many of the German states, no emigrant could lawfully leave his parish until various documents were completed. The emigrant essentially surrendered all clams upon his local community and the State. Concessions were made after the political unrest in various German states in 1849-49. Legal formalities which preceded emigration were simplified. It was also easier for the individuals in the southwestern region of the German Confederacy, such as Baden, who wanted to avoid military service obligations at the time to slip over the Rhine into France where passport formalities were more or less perfunctory. Hamburg and Bremen kept on good terms with interior German states by instituting strict law enforcement supervision over German Emigrants. [29]

The prominence of both Havre and Bremen as ports of departure for German immigrants to America in the mid 1800s was largely due to their established overseas and inland continental commerce routes for the transport of raw cotton and tobacco to inland manufacturing areas respectively. [30]

Le Havre as a port for German Emigrants was dominant between 1820 to the mid 1850s. In the mid 1850s Bremen and Hamburg caught up with Havre in terms of the number of immigrants utilizing their ports. The emerging dominance of Bremen and Hamburg were due to the widening impact of economic conditions in other regions of the German Confederacy (the North and Northeastern areas) that facilitated emigration and technological advances (railway and steam ships on inland waterways).

“The passenger trade had reached the modern era, and Bremen and Hamburg had come to dominate it; in the 1850s they shipped 63% of all German emigrant traffic, and they claimed a virtual monopoly on it every decade thereafter. … “

“By the mid-1840s, the approach of Bremen in handling emigrant traffic, and the diffusion of modern technology throughout the internal transport system had carved the path for the future of emigrant transportation; the convenient and cheap routes offered in France and England would fall by the wayside as the traffic became increasingly internalised and was competed for between the Hanseatic ports. The most competitive strategies for acquiring migrant traffic and the most modern means of conveyance – rail and ocean steamer – were all established precisely by the point the emigration began its major upswing in 1846/7.” [31]

By 1843 Bremerhaven had begun to at least equal Le Havre as the principal port of embarkation, and new passenger milestones were hit every year from 1844 to 1847. [32]

This pivotal moment for the dominance of Bremen and Hamburg for German American immigration happened just after the immigration of the Fliegel family members and John Sperber .

Table Two: German Emigration through German and Foreign Ports 1846- 1851

| Year | German Ports | Foreign Ports |

|---|---|---|

| 1846 | 38,058 | 56,523 |

| 1847 | 42,382 | 67,147 |

| 1848 | 37,532 | 44,368 |

| 1849 | 36,249 | 52,852 |

| 1850 | 37,061 | 45,343 |

| 1851 | 56,070 | 56,477 |

| Total | 247,352 | 322,710 |

Since the port of Le Havre was discussed in part two of this story, I am limiting discussion to Bremen and Hamburg in this part of the story.

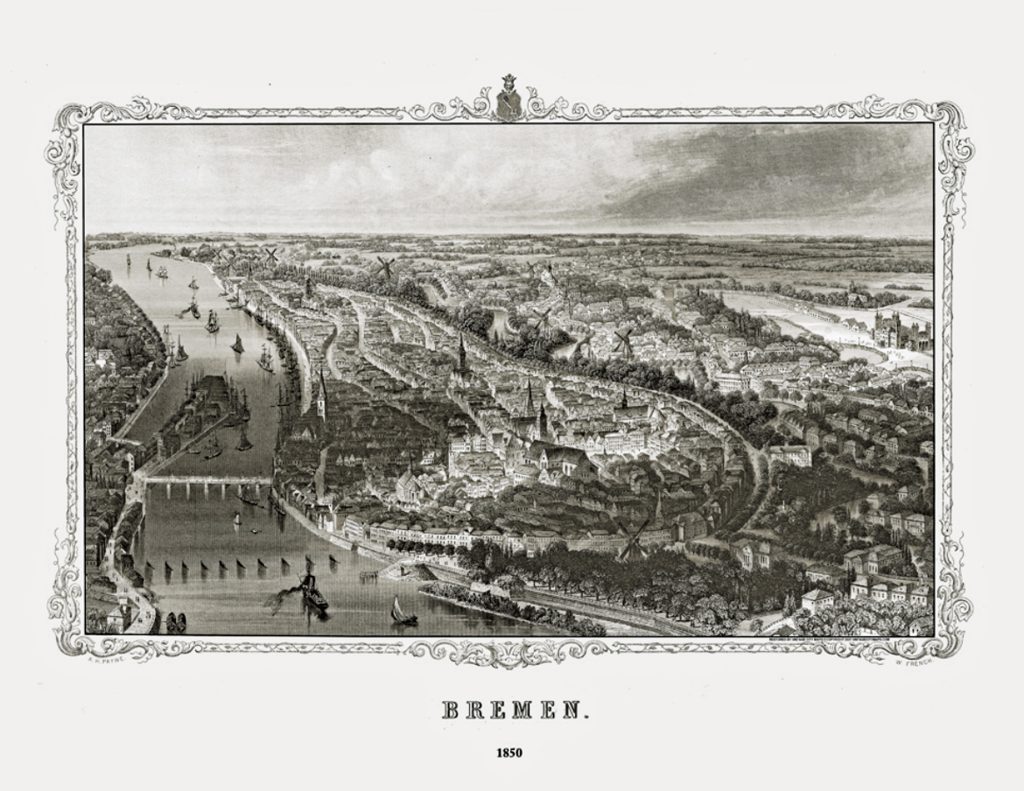

The Free Hanseatic City of Bremen

For most of its 1,200 year history, Bremen was an independent city within various state jurisdictions. Initially, Bremen’s port activities were centered around the Balge and Schlachte ports along the Weser River. [33] By the 19th century, silting problems in the Weser River made it difficult for sea vessels from the north to reach these inland ports, necessitating access and the establishment of outer harbors. [34]

“Throughout the nineteenth century commerce and trade determined the daily life of Bremen and its development in the region. Bremen established its position as a major emigrant port during the first half of the nineteenth century with extensive trading links with North America. It imported a wide range of staple goods, notably tobacco, sugar, animal skins, French wine and cotton which had become key components of its trading activity by the 1850s.” [35]

Bremen in 1850 [36]

“Close trade connections to the American republic, developed since the 1780s… . But throughout much of the nineteenth century, the merchant-shipowners faced a curious problem: Quicksands filled the city’s harbor, seventy kilometers upstream from the mouth of the river Weser, so that it could no longer be reached by seagoing ships. Their vessels had to moor downstream at Vegesack, Lehe or Brake, small port towns which belonged to the states of Oldenburg and Hanover, and had to pay tolls, taxes and dues there. To escape from this dilemma, the city’s merchant-dominated Senate, in a farsighted decision, bought land downstream and in 1827 founded the harbor and city of Bremerhaven close to the North Sea.” [37]

“The one problem remained the 50 km connection between Bremen and Bremerhaven. In to the 1850s, this distance had to be travelled by small open riverboats, rain or wind notwithstanding. This last Jog could be traveled in a day but it usually took two to three days depending on wind and tides. The waiting period in Bremen for a ship (in the 1820s and 1830s often six to eight weeks) was reduced by the regular train connections, regularly scheduled ship departures and better planning to three to four days on average, thus reducing the cost for the emigrants.” [38]

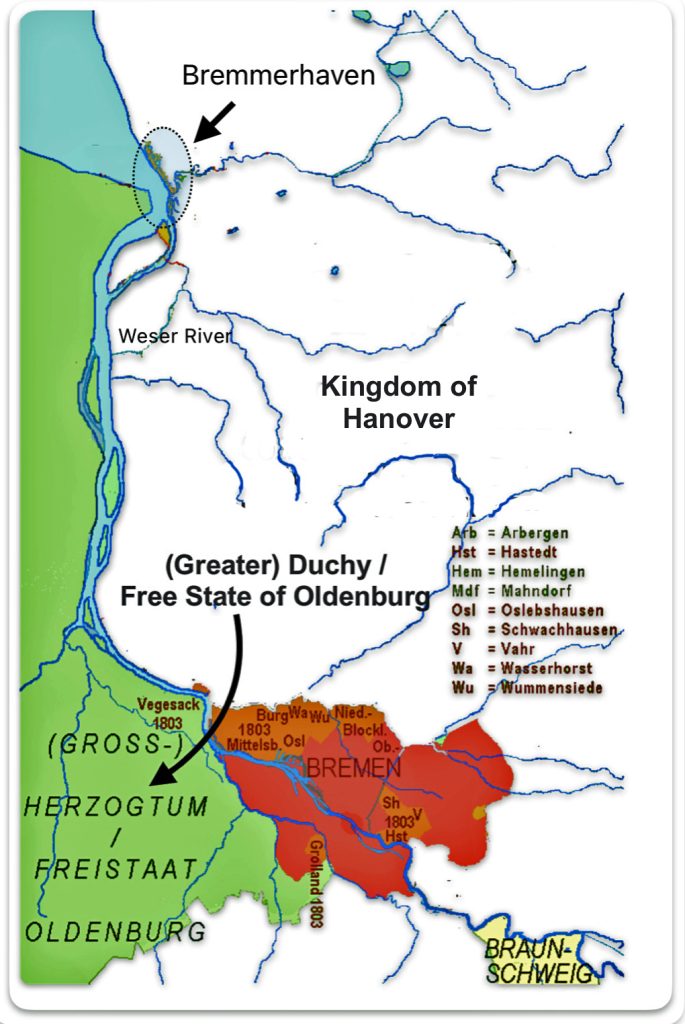

In 1827, the city of Bremen purchased land at the mouth of the Weser River to establish Bremerhaven, a new port that would allow direct access to the North Sea and accommodate larger ships. This strategic move was crucial in Bremen’s emergence as a major passenger port. The establishment of Bremerhaven enabled Bremen to handle the increasing volume of overseas trade and consequently passenger traffic. [39]

After the acquisition, Bremen, or the Free Hanseatic City State of Bremen, consisted of two non-contiguous territories: Bremen, officially the ‘City’ (Stadtgemeinde Bremen) and the city of Bremerhaven (Stadt Bremerhaven). Both are located on the River Weser. [40]

Map Five: Bremen and Bremerhaven [41]

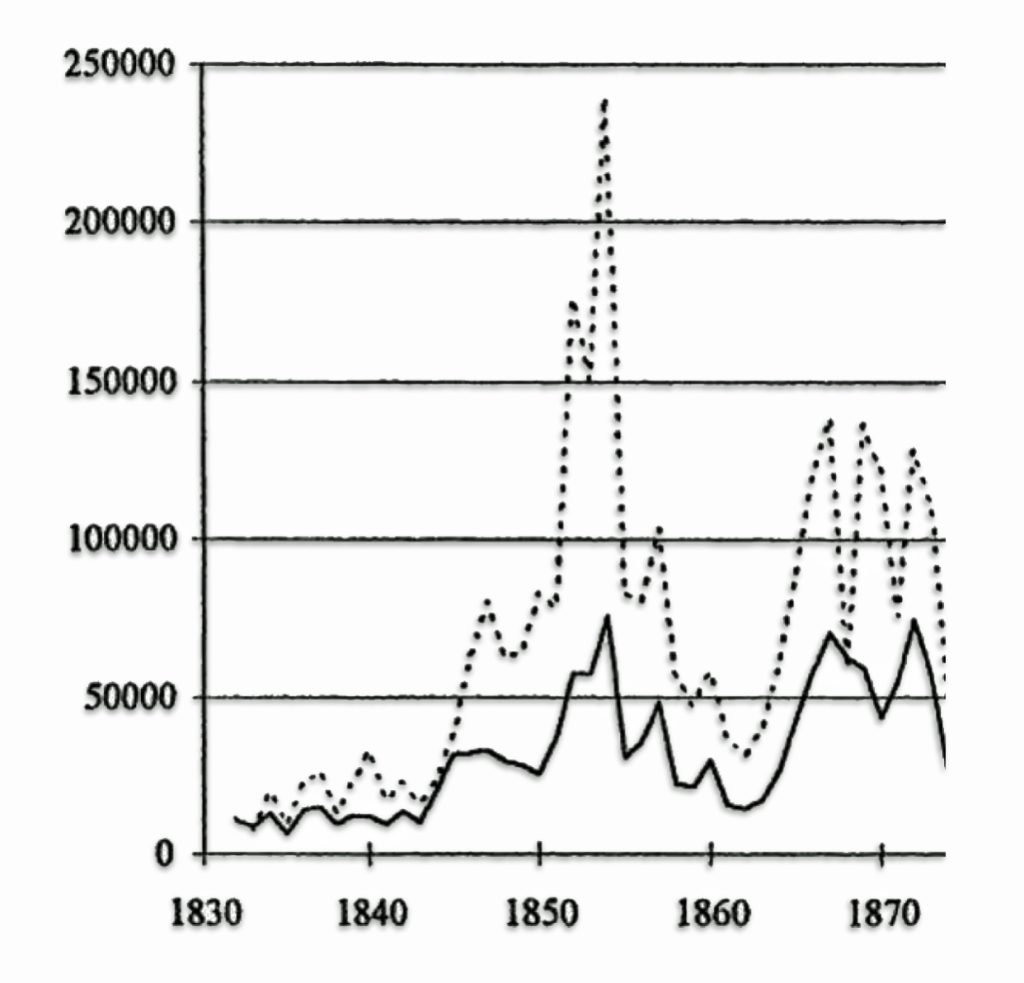

Until the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, emigration from Bremen was low. It grew in the 1820s and in the fall of 1830 and in 1831, Bremen almost accidentally experienced its first emigration “wave.” The July Revolution in France [42] and poor harvests in northwestern Germany sent many people migrating. They, however, could not access the western ports of Antwerp, Rotterdam and Le Havre because of the Belgian rebellion blocking access [43] and a cholera epidemic. [44] About 3,500 emigrants passed through Bremen/Bremerhaven in 1831. This little wave is illustrated in graph one below.

Graph one illustrates a small increase in immigration around 1832. The increase in migration through Bremen was brought about by a number of factors. The institution of protective measures for immigrants by the local government and a number of private initiatives to stimulate and profit from immigration had direct positive impacts on immigration. The city council of Bremen passed ordinances in 1832 that required companies transporting emigrants to file passenger lists and maintain certain standards for the ships, which improved the quality of life for emigrants. [45]

In addition, a 1827 treaty with the United States established mercantile privileges to the city that were on par with European states. [46] This facilitated the commerce ties between the independent city and the United States.

“After the initial 3,500 had passed through in 1831, the city transported some 38,506 migrants between 1832 and 1835. This huge upswing was coterminous with significant increases in tobacco shipping, as Bremen’s capturing of valuable export material encouraged an increasingly profitable two‐way trade. The city was soon a near monopoly importer of vast amounts of the raw American product, absorbing fully half of all U.S. exports, yet by just 1836, the emigrant trade had outstripped tobacco in overall value to the city.” [47]

These regulations and international treaties may have contributed to Bremen’s growing popularity as a port of departure over the 1840s and 1850s [48]. Bremen also established an office where emigrants could find information needed for their journey, monitored prices being charged to emigrants, and ensured they were fair [49]. This focus on treating emigrants well was good advertising, as satisfied emigrants would write back to their families recommending Bremen as the departure point [50]

As reflected in graph one, Immigration from Bremen and Bremerhaven did not take off until the early 1840s.The effects on Germans emigrating from Bre=men around 1848 was not as dramatic as experienced in other European ports. Thereafter, the trends in immigration from Bremen mirrored other European ports until 1866-1867.

Graph One: Emigration via Bremen / Bremerhaven and Other Ports 1830 – 1870 [51]

When John Sperber was contemplating the move to America in 1851-1852, Bremen was starting to gain prominence as an emigrating port equal to Havre. This was mainly due to the development of the port , its ties to the outer lying geographical region [52], the establishment of railways between Bremen and inland waterways [53], and the increasing economic hardships faced by Germans in other regions of the Confederation (the northwestern and northeastern German states). [54]

“The waiting period in Bremen for a ship (in the 1820s and 1830s often six to eight weeks) was reduced by the regular train connections, regularly scheduled ship departures and better planning to three to four days on average, thus reducing the cost for the emigrants.” [55]

In the first three quarters of the nineteenth century, legislative efforts in the free Hanseatic states of Bremen and Hamburg facilitated German emigration by improving the conditions of transportation to the ports and regulating the quality of care for immigrants.

“Much more efficient was the legislation of the free cities of Bremen and Hamburg. The measures they adopted were dictated by an enlightened appreciation of their own interests. As soon as the stream of emigration began to flow through Bremen, she began to regulate the traffic in transoceanic passengers, so as to encourage the business; and since the administration of the law was in the hands of those that made it, evasion was not easy. As early as 1830, she not only prescribed what was then considered sufficient space and food for steerage passengers, but she also required that the food should be cooked. After 1850 for the accommodation of emigrants passing through she maintained a bureau of information; and special agents appointed by the city authorities met the incoming trains at the railway stations, guided them to hotels that had been inspected and licensed to receive them, protected them against extortion, and gave them aid and advice in preparing for the voyage” [56]

In the short run these regulations may have contributed to Bremen’s growing popularity over the 1840s and 1850s as a port of embarkation for emigrants. Other port cities gradually followed suit such as Hamburg. A competitor of Bremen, Hamburg passed protective legislation in 1837. [57]

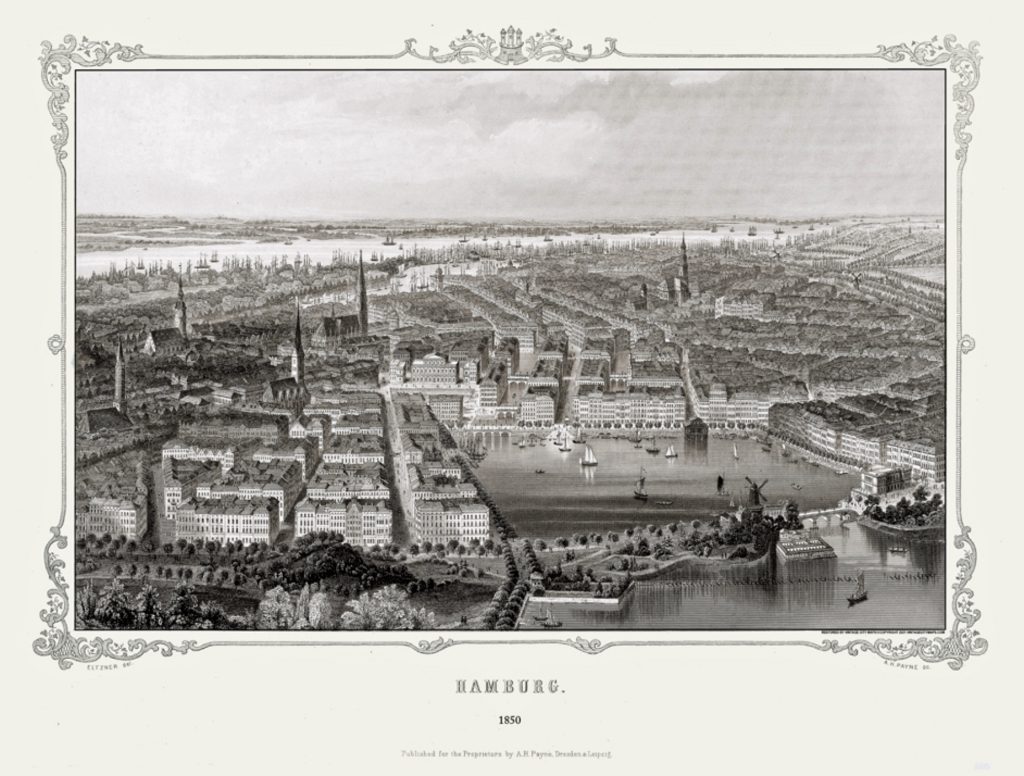

The Free Hanseatic City of Hamburg

Hamburg is situated on the River Elbe, approximately 110 kilometers or about 68 miles from the North Sea, which has historically provided the city with direct access to international shipping routes. This advantageous position allowed Hamburg to become a central point for goods moving in and out of Central Europe. Hamburg served as a port for the timber and grain of Prussian estates, as well as the manufactured goods of Saxony and Bohemia.

Hamburg is one of Germany’s three city-states alongside Lübeck and Bremen. Similar to Bremen, Hamburg was an independent city state within various historic jurisdictions through its history. During John Sperber’s life, Hamburg was a member of the 39-state German Confederation from 1814 to 1866 and, as the other member-states, enjoyed full sovereignty.

Hamburg’s history as a port dates back to at least the 9th century, but it was officially founded in 1189 when Emperor Frederick I granted the city a charter, which included tax-free access to the North Sea via the River Elbe. This charter laid the groundwork for Hamburg’s development as a port by encouraging trade and shipping activities. During the medieval period, Hamburg became a member of the Hanseatic League, an economic and defensive alliance of merchant guilds and market towns in Northwestern and Central Europe. [58]

“A few miles to the east, at the mouth of the Elbe, lay the city of Hamburg, a great emporium which first looked with interested disdain upon the efforts of its weaker neighbor. … (I)t did not for some time appreciate the opportunities offered by the transportation of human beings.” [59]

“The initial migrations of the 1830s had utilized the Atlantic ports of Le Havre, Antwerp and Rotterdam, and Hamburg made no effort to attract this new business. In fact, in 1832 when Bremen began to enact legislation protecting emigrants, Hamburg tried instead to prevent emigrants from using its facilities.”[60]

“Until early in the nineteenth century … Hamburg paid little attention to the New World.” [61]

Hamburg 1850 [62]

When Bremen enacted innovative policy and practices that required ships to provide food and adequate travel accommodations in 1832, Hamburg was placed in a disadvantage in terms of the emigrant transportation market. In the ensuing five years Hamburg lost five percent of the trade with America while Bremen experienced a twenty percent increase. [63]

While Hamburg initially took a dim view of German emigrants, the local businesses and collective actions of the city were amenable to utilize existing commercial ties with England to forward immigrants on to British ships traversing the trade route between their city and Hull, England. The lack of state regulation in Hamburg encouraged shipping firms and agents to advertise ballast space on the boats that traveled on regular routes between ports on the North Sea. The ships working between Hamburg and Hull were small, dealt poorly with bad weather, and often carried livestock. [64]

“Connections between Hamburg and England had always been close. In 1838 steamships crossed three or four times a week from Hamburg to Hull, which was reached on the third day. Another three days’ journey brought the travelers to Liverpool here usually they could embark at once for New York a voyage of thirty-five or forty days.” [65]

In 1828 the first North American shipping line began to operate in Hamburg. However, the majority of the North American traffic from German ports flowed through Bremen. In the 1840s Hamburg shipping interests began to consider the passenger trade. In March 1847 a stock corporation was founded, the Hamburg Amerikanische Packetfahrt Aktiengesellschaft (HAPAG) or the Hamburg-Amerika shipping line, and started out with two sail ships that accommodated 220 passengers. [66]

“With these two ships the round trip to North America took forty-two days out and thirty days to return. The emigrant trade was so lucrative, that within the next five years the Hamburg-Amerika Line bought four more ships, and chartered a number of others. By the end of 1853 the corporation commissioned the construction of two steamships, without waiting for a government subsidy.” [67]

The Hamburg-Amerika Line was instrumental in shaping the patterns of migration from Europe to the Americas. However, its impact was largely felt after John Sperber and the Fliegel family emigrated from Baden. From its inception, it facilitated the mass movement of emigrants, primarily from Germany, Scandinavia, and later from Eastern Europe, to destinations across the Atlantic including the United States, Canada, and Latin America. The line’s operations significantly contributed to the demographic transformations in these regions, as millions of Europeans sought new lives in the Americas. [68]

The Hamburg merchants also grew increasingly concerned with the more human aspects of the emigration trade. Their primary interest was managing the impact on the city of the increasing flow of emigrants to the port. To cope with these and other issues, Hamburg merchants formed the Hamburg Association for the Protection of Emigrants, and under its direction established an Information Bureau for Emigrants in 1851. Supported by the financial contributions of the merchants, the Bureau opened offices at the major railroad stations and other locations where emigrants congregated. It provided reliable information on the cost of rooms and provisions, passage prices and dates, and advised emigrants on the amount and types of provisions to take with them. [69]

“In 1850, just 10,000 passengers had passed through Hamburg; in 1854, the number was 50,809.56. Of those, Hapag carried 8,601, and Sloman 8,571, although some of Sloman’s custom remained linked to the indirect route. In fact 18,509 passing through Hamburg that year still went via Liverpool. … In total, 25,700 Germans emigrated via Liverpool in 1854, among which 3,000 Hessians, 6,000 Württembergers, 6,000 Badeners, 1,600 Palatines and 1,500 from the duchy of Nassau were enumerated.” [70]

Robert Miles Sloman was an English-German shipbuilder and ship owner. He made several significant contributions to the shipbuilding industry, particularly in the transition from sail to steam-powered vessels and in establishing regular transatlantic shipping services. [71]

Inland Waterways to the Three Ports

If John Sperber was able to utilize any of these waterways to the ports of Le Havre, Bremen or Hamburg, he would have had to use a combination of roadways and possibly rail systems or roads that existed in the early 1850’s. None of the waterways from Baden-Baden were directly linked to these three major ports.

Map six reflects the major waterways in relation to Baden and the three major ports of Havre, Bremen and Hamburg. It should be noted that the Marne-Rhine Canal between Marne and Strasbourg, France was not completed when John Sperber emigrated in 1852. [72]

Map Six: Havre, Bremen, and Hamburg: Their Range and Their Waterways

Of the three ports, Bremen exploited the use of inland waterways for immigrant transportation. The use of steam ships on inland waterways coupled with emerging railways, had a major impact for the port of Bremen for transporting German emigrants. “It was not until steam technology began to diffuse more completely into the interior German river routes that Bremen was able to fully challenge the natural advantages of its competitor ports.” [73]

A steamship company, the Cologne Rhenish Prussian Steamship Company, was established in 1829 and was operational by 1833. By 1835 the company had 15 steamships that operated on the middle and lower Rhine River. The steam ships operated as far south as Strasbourg to pick up Palatine, Baden and Württemberg emigrants and bring them to the northern city of Bremen. The steamship line also connected services along the Main River.

“The steamship companies expanded their number of vessels and significantly advanced the speed of south-north transportation from weeks to a matter of days. As the emigration began to gather pace in the early 1840s, localized river connections also began to spring up in order to accommodate the trade.” [74]

Steam shipping was also established on the Neckar River in the spring of 1841. Steamships worked on a daily basis from Heilbronn to Mannheim where the Rhine and Neckar Rivers join. Connections from this conjunction point could then be made with the dozens of steamers traversing the ‘south‐north route’. [75]

In 1842 Bremen legislators and merchants established the Upper Weser Steamship Company which included eight ships. The price for the trip was hardly higher than that charged by carters for an overland trip. This company served as a feeder connection to transport from Bremen to Bremerhaven. [76]

The advancement of utilizing inland steamship transportation made it possible to reach Bremerhaven from the Neckar Valley, Kraichgau or Black Forest region in five to six days. When emigrants had travelled up the Rhine to Rotterdam in 1816 – 1820, the average journey time had been 4-6 weeks. [77]

Roadways in France and German States in 1800s

Until the mid 1700s onward, “(t)he roads of Europe were essentially those of the Roman Empire–after fourteen hundred years of neglect.” [78]

Paved roads were built with a long-term perspective. Paved roads embodied large investments to connect cities, towns and regions. The use of the roads, through tolls, enabled the funding of new investments. Government taxes and the use of wage labor, pauper labor or unpaid duty-service helped to maintain the paved roads.

France was comparatively ahead of the German states in the development and maintenance of roadways connecting major towns. As early as the late 1600s and into the 1700s, France committed government funds, laws and organizational means for establishing roadways to connect outlying regions of France to Paris.

“France led the way with an early initiative promoted by Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV’s chief minister for domestic affairs. One of his first measures … was to centralize responsibility for the maintenance of roads. In 1669 special ‘commissioners for bridges and highways’ were appointed to serve alongside the intendants, the most powerful provincial officials. As a first step towards their upgrading, all roads were classified either as ‘royal roads’ (chemins royaux) with a width of between 23 and 33 feet (7–10 m), or secondary roads (chemins vicinaux) or side-roads (chemins de traverse). … Significant improvement did not come until the 1740s, when the service was reorganized and a special academy established to train engineers in the art of road-building.” [79]

To improve transportation and connectivity between cities, the French government classified roads according to their economic or strategic importance, prioritizing major thoroughfares used by postmasters and main highways connecting Paris to the frontiers and ports. In addition, with the rise of the French Empire in the early 1800s, there was a need for armies to travel rapidly from one area to another, which was facilitated with paved roads.

“By the end of the monarchy, there were about 25,000km of major roads in France. This highly centralised network was mostly constructed during the last third of the 18th century. The so-called military roads that lead to the eastern frontiers reveal that favouring trade was not the only reason for the construction of the network.”[80]

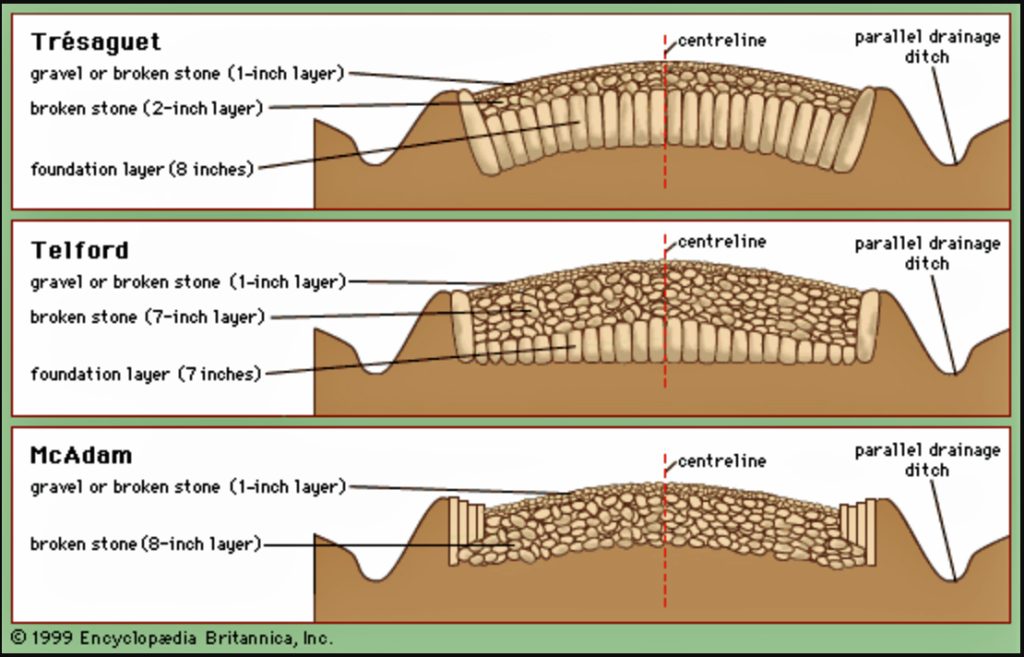

To make roads cheaper to build and easier to maintain, innovations by civil engineers like Trésaguet aimed to create roads with reduced workforce and building costs so more work could be completed. His method established in 1775 involved a layer of large rocks covered by smaller gravel, improving drainage and allowing for continuous maintenance. Well-constructed paved roads with good foundations and drainage allowed vehicles to travel more quickly and smoothly compared to muddy, unpaved routes. [81]

Cross Sections of Three 18th-Century European Roads [82]

As indicated in the second part of this story, there were a number of roadways in France that were built between major cities and towns that were used for emigrants traveling to European ports. These French postal roads coincided with commerce routes from the port of Le Havre to inland areas.

“The monarchy began to classify roads according to their economic or strategic importance. Priority was given to major thoroughfares used by the postmasters and to the main highways from Paris to the frontiers and the ports. Royal instructions defined the width of different kinds of roads: the widest were three lane roads with a paved road in the middle and two dirt tracks (bermes) on either side. Unpaid duty-service was generally used in France after 1738, in order to build toll-free main roads and to keep them in good repair. This continued until the French Revolution and during this period some 24,000 kilometres of paved roads were built.”[83]

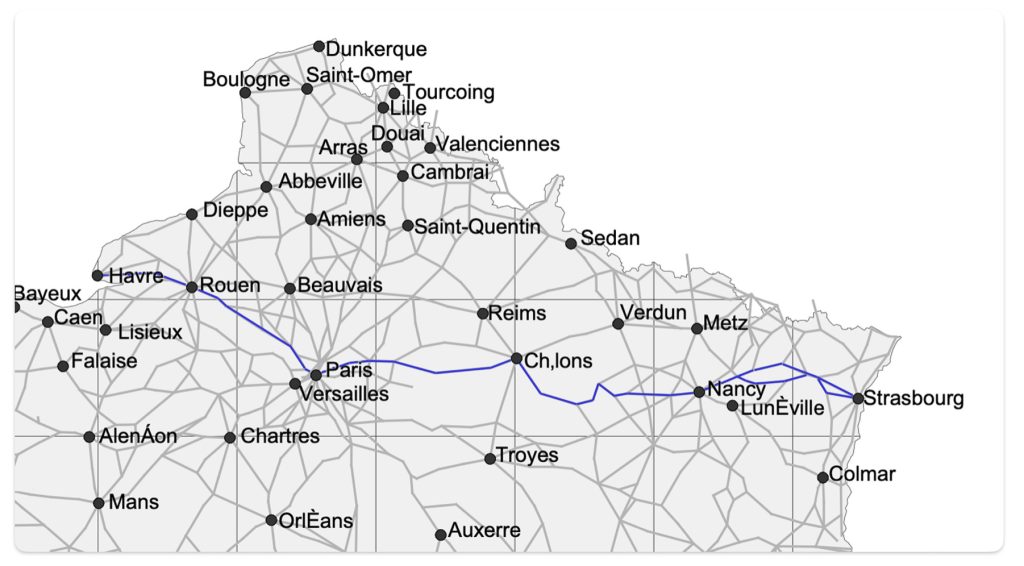

Map six was discussed in the part two of this story. I am introducing this map again to underscore the direct path that John Sperber had when traveling via road from the French border in Strasbourg to the port of Le Havre.

Map Six: French Postal Roads, Main Cities and Towns in 1833; and the Highlighted Possible Route of John Sperber from Strasbourg to Le Havre [84]

The basic ideas on building and repair of French roads were put forward by an emerging cadre of civil engineers, who began to produce theories about and general principles of the practice of road construction and advocated technical advances road building and maintenance. These theories and general principles were subsequently utilized by German states in developing paved road networks between towns and cities.

“Gradients were improved by cutting through hilltops and narrow and crooked roads were widened and straightened. Most writers and engineers agreed that roads should be built straight, as this allowed for simpler construction. The common aim of eighteenth century innovations was to create roads that were cheaper to build and easier to maintain.” [85]

Similar to France, the latter part of eighteenth century experienced the first German-wide road building since the Roman Empire in Europe. However, given the political configuration of the confederated states, road building and maintenance was not centralized as it was in France.

“The origin of the name “Chaussee” and the design comes from French. The term “Chaussee” almost certainly found its way into Germany with the construction of the first artificial streets based on the French model. German road construction was under French influence from the beginning. Consequently, the first highway in Germany was built between Nördlingen and Öttlingen in an area (southwest Germany) where French influence was always strong.”[85a]

During the Napoleonic occupation, local traffic connections were generally not in a good shape. [86] However, improvements were made in the first half of the 1800s to main roads between major German cities. Cargo as well as passenger and mail transportation time were greatly reduced during this time period. Cargo and passenger capacity rose in the same manner. In addition to improvements in road construction, the introduction of express carriages reduced travel time. [87]

“(T)he larger part of the investments in traffic infrastructure went into highway building. The improvement of these new roads was so remarkable compared to the old ones that they were called “artificial streets”. In the three years from 1805 to 1807, more than 5,000 km of highways (Chausseen) were built or improved in Bavaria, and in Prussia, the length of the highways doubled between 1830 and 1848 to 15,000 km. …“The improvements that followed from these measures (and especially from the improvements in traffic organization) were quite considerable. Cargo as well as passenger and mail transportation time was greatly reduced and capacity rose in the same manner. The improvements that were possible become obvious when one considers that the introduction of express carriages alone reduced travel time between Frankfurt / Main and Stuttgart from 40 hours in 1821 to 25 hours in 1822.” [88]

After the Napoleonic Wars, Germany became a federation of thirty-nine states. As discussed previously, the map of Germany was the most confused in the center of the confederation of the German states. This part of Germany was split up into a medley of medium and small sized states and territories. It is in this area that the quality of transportation routes and maintenance of roads were hampered by lack of funds and planning.

One notable exception was the small Duchy of Braunschweig (the Duchy of Brunswick). [89] Between 1785 and 1840, Duchy of Braunschweig was one of the densest and centrally organized land transport networks in the German Confederation. The Duchy of Brunswick State Railway was the first state railway in Germany. The first section of its railway line opened in December 1838. [90]

Since all of these states controlled their own social and economic affairs, road building and maintenance were controlled by each state. Each state used its geographical position and natural resources to their advantage. German states did not hesitated to pursue economic initiatives for their own gain, even if it had a negative impact on neighboring states. This led to road building deliberately designed to attract or divert transit trade from one state to another. [91]

Despite the political and economic maneuvering between the German states, substantial investments in transport infrastructure were made in many parts of Germany before 1850. Influenced by attempts to join firmly together its eastern and western, the Kingdom of Prussia built large networks of paved roads, especially in the regions of Westphalia and the Rhineland (see map seven). [92] The German state of Westphalia, experienced rapid paved road network growth and road development accelerated during the 1820s. By 1830,

Westphalia was the Prussian province with the second longest paved road network

after the Rhine province. [93]

“It was only with the political reorganization after 1815 that highway construction in Westphalia was tackled on a large scale. Both the promotion of the economy in the New Prussian areas and the possibility of quickly deploying troops throughout the extensive kingdom were the central motives for this complex and resource-intensive projects. Part of the ongoing costs incurred for construction should be recovered through the road tolls charged for the use of the state-owned artificial roads. In total, the state invested approximately from 1830 to 1850, up to 2.5 million thalers per year were spent on the construction and maintenance of the roads, which was the highest amount of all road construction expenditure in the Prussian provinces. “ [94]

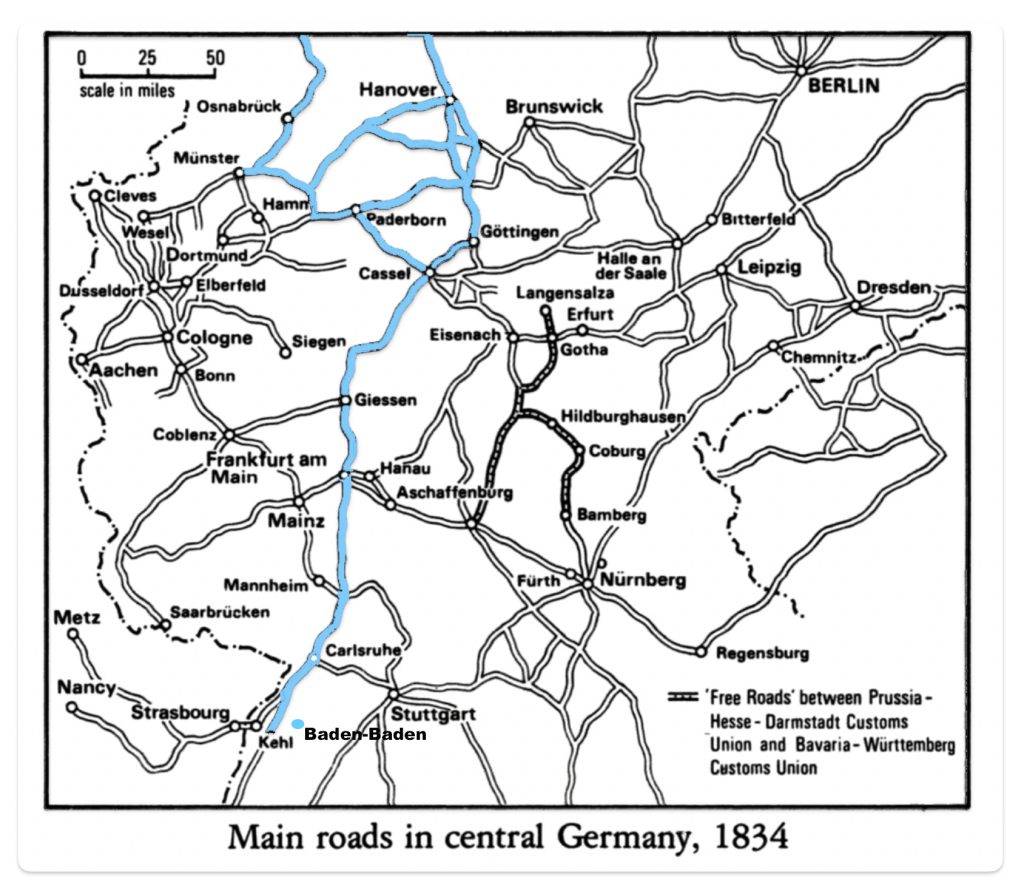

Map seven provides a geographical view of the discussion of German roadways in German states. [95] The potential points of travel for John Sperber are in blue (e.g. Baden-Baden, Bremen and Hamburg). German States that are discussed are noted on the map. As reflected in the map, John Sperber’s possible journey on the roads in Germany to either Bremen or Hamburg would have led him through a number of the smaller states.

Map Seven :German States After 1815

Roads in Prussia (and other German states) were systematically paved and upgraded for heavier loads, long distance road transports of goods and passengers. A mitigating factor with road transport was tolls on roadways. In Prussia, road tolls were not abolished until 1875. [97]

“The State in Prussia not only promoted industrialization directly — by running nationalized undertakings and by assisting private firms in various ways — but it also stimulated the economy in an indirect way by providing a legislative and physical environment favourable to industrial progress. The State was responsible for the provision and maintenance of the main roads, the rivers and the canals. Despite financial difficulties the Prussian government made strenuous efforts to improve the main roads in the period of reconstruction after the Napoleonic Wars. A loan raised in London enabled over 1,000 miles of roads to be built between 1825 and 1828. In Westphalia, Ludwig Vincke (president of the province between 1815 and 1844) showed how an energetic official could improve communications. He succeeded in completing the construction of the great highway running through the province from Wesel to Minden. This road proved to be of great benefit to the coal and iron industries of the Ruhr.” [98]

Arrangements to reach Bremen and Hamburg from southwestern parts of the German Confederation by road improved in the late 1840s. However, the arrangements were cumbersome. While immigrants from Baden to Havre could travel in their vehicles due to the availability of selling their wagons and horses in Paris, no such opportunities existed in the northern German states where Hamburg and Bremen existed. Similar to Havre, freight wagons and wagon services were available going to Bremen. [99]

Possible road routes that John Sperber could have considered to reach the ports of Bremen or Hamburg are noted in map eight. John could have traveled from Baden-Baden north through Carlsruhe [100] to Frankfurt. From Frankfurt, the journey could have proceeded through Giessen, then Cassel (Kassel) and Gottingen to Hanover. Bremen or Hamburg could then be reached from Hanover. Many of these road were toll roads. [101]

Map Eight: Possible Road Routes from Baden-Baden to Bremen or Hamburg [102]

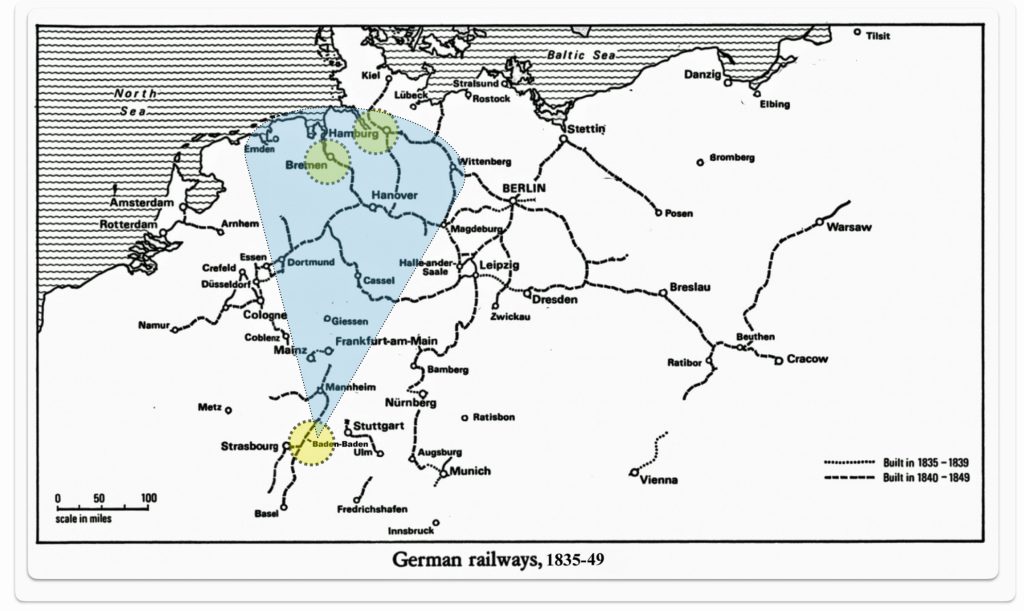

German Railway in the First Half of the 1800s

The development of rail lines in German states in the 1840s facilitated the transportation capabilities for German travel to the ports of Bremen, Hamburg, Antwerp, Amsterdam, and Havre. The German rail lines, however, did not provide continuous links to each of these ports and to other cities within the German states in the late 1840s and early to mid 1850s.

“(T)he railways were not to escape from the jealousies and conflicts of the German states, since the different states’ postures towards them varied considerably.” [103]

“In these 38 states prevails as many separate interests which injure and destroy each other down to the last detail of daily intercourse. No post can be hurried, no mailing charge reduced without special connections, no railway can be planned without each seeking to keep it in his own state as long as possible.” [104a]

Political disunity among the Germanic states made it difficult to build railways in the 1830s. The German railway system was built piecemeal with no centralized planning as found in France. Each German state was responsible for the lines within its own borders. “In the early days there was what has been called a ‘spontaneous anarchy of petty companies’. There were rivalries between different states over railway building and there were disputes between towns and districts in the same state. [105]

“The contemporary mind in Germany had boggled at the implications of large scale railway planning in organisational, technical and financial terns, but several states quickly appreciated the need for broad legal regulation of railways, especially as piecemeal construction of individual railways began to fuse into longer routes and, even more significantly, began to cross state boundaries.”[106]

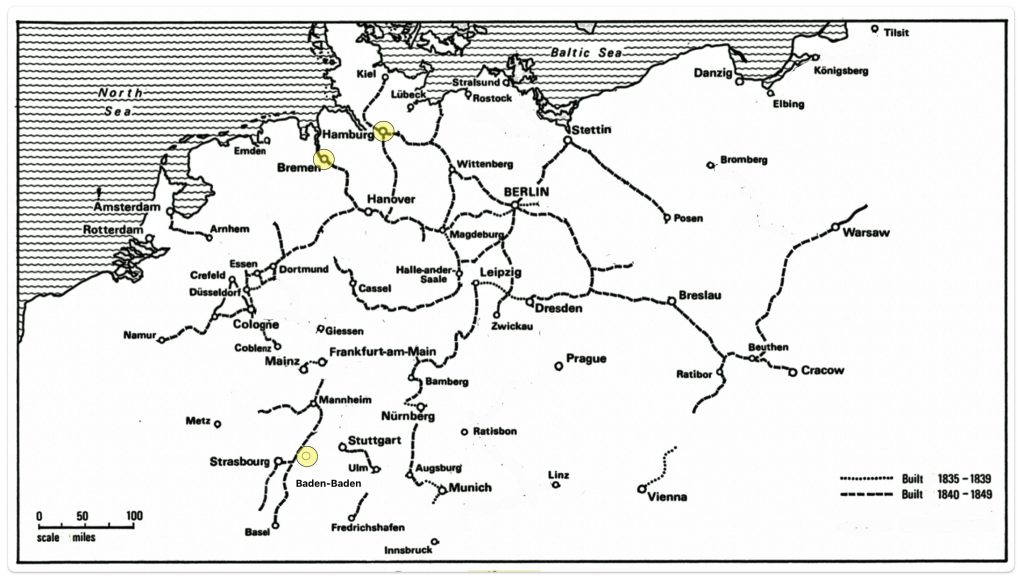

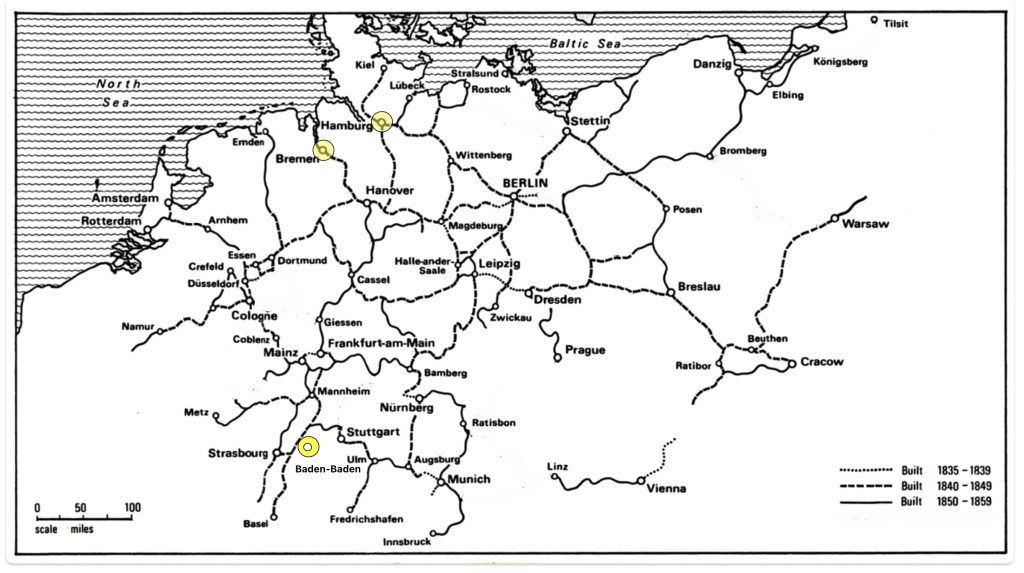

By the 1840s, trunk lines linked the major cities in the larger German states. See map nine. By 1845, there were already more than 2,000 kilometers or about 1,245 miles of railway line across German states. [107]

Map Nine: Railway in the German States 1835 – 1849 [108]

By 1855, the length of railway was above 8,000 kilometers. Oftentimes immigrants would need to take wagons or travel on waterways to catch another train line. [109]

In the first half of the 1800’s, the development of railway systems caused a major, perhaps an epochal shift, a transportation revolution. Industrialization in Germay was pushed by the development of the rail system along with the demand for coal, iron, and steel. Between 1840 and 1870, the train became the dominant mode of inland transport, with inland water navigation losing its leading position. It has been argued that the Industrial Revolution in Germany cannot be explained without the development of the railroad.

“Within five years of the opening of the first railway, some. 500 km. of route in ten sections had been opened and many further sections were being built, so that by 1845 the route length had risen to over 2,000 km. , three-quarters run by private companies and the rest by the rapidly growing state railways.” [110]

“In the 1840s Germany expanded her network of railways more rapidly than any country on the Continent except Belgium. … Germany had 3,660 miles of railway in operation in 1850, which was nearly double that of France. … While in England and France the major railways radiated from the capital, there was no city that dominated the whole railway system in Germany. The three most important railway centres were Berlin, Cologne and Munich.” [111]

Map Ten: Railway in the German States 1835 – 1859 [112]

“As the various companies’ tracks extended and began to join up, the network of through routes spread, so that by 1850 (as indicated in map ten) the railway map was already beginning to show the main characteristics of the modern system. “Five lines already radiated from Berlin; the Saxon lands were served by an appreciable basic network; while the Rhenish-Westphalian and Rhine-Main areas were emerging as focal points of local systems. Within the next five years, almost all the principal provincial towns were to be drawn into the railway network as additional through routes were completed … .” [113]

It is apparent that rail access between Baden and the respective ports of Bremen and Hamburg were not directly accessible for John Sperber between 1850 and 1853. When they left Baden, railway development in other parts of Germany was just starting to expand. “Between 1846 and 1861, the number of steam engines in both Baden and Württemberg increased ten-fold; in Hanover, the figure was more than twenty-fold. The number of steam engines increased in from 24 in 1846 to 226 in 1861 in Baden [113a]

For Germans traveling from Baden, such as John Sperber, railways were not complete to travel to Bremen or Hamburg. Various roadways or a combination of rail, waterways and roadways would have been utilized to travel northward to the German ports in the early 1850s.

Map Eleven: Northward path to Bremen and Hamburg Based on Railway Development in 1850

The development of the rail system had a slow fitful start in the 1840’s. Catherine Fliegel’s emigration and John Sperber’s journey to the United States in 1848 and 1852 respectively could not exploit the benefits of the German rail system since the railways from Baden to Havre and from Baden to Bremen or Hamburg were not complete. However, the remainder of the Fliegel family (John Sperber’s in-laws) could have utilized the rail systems in 1854 when they traveled to Havre from Baden; and if desired, utilized railways to Bremen and Hamburg.

The Three Routes: Waterway, Road, Railway Development

“In the 40 years between 1816/17 and 1856/7, the entire mass transit system of German emigration was built. The impetus for building this system came from the emigrant trade of the North and particularly the South West, which led to farsighted policy and business strategies in Bremen, and greatly supported the early steamers of the interior river routes.” [114]

However, the dates of emigration for the Fliegel family and John Sperber were at the tail end of this 40 year period. As such, they could not totally benefit from its completion. If my evidence of John Sperber sailing to the United States on the Germania from Le Havre in 1852 is of the contrary and he possibly sailed from Bremen or Hamburg, it is likely that his alternative path would have been from Bremen.

“In 1842, Bremen merchants founded an Upper Weser Steamship Company with eight ships as a feeder connection to bring migrants from central Germany. The price for the trip was hardly higher than that charged by carters for an overland trip. By 1847, Bremen -but not Bremerhaven – was connected to the southbound railroad network by the Hanover line. … The railroads offered special low-priced tickets to emigrants to keep the German network competitive as compared to the French rail connections to Le Havre.” [115]

The Baden to Bremen route probably was an effective alternative route to the Baden to Le havre inland route. Bremen could have been reached by roadways from Baden. Bremen could also be reached through the use of a combination of train (Baden Main Line), waterway (the Rhine River to Cologne) and then rail via Hanover and Bremen.

Major Interior Rivers Served By Steam Transportation/Rail Lines to Docks of Bremen and Hamburg, 1847 [116]

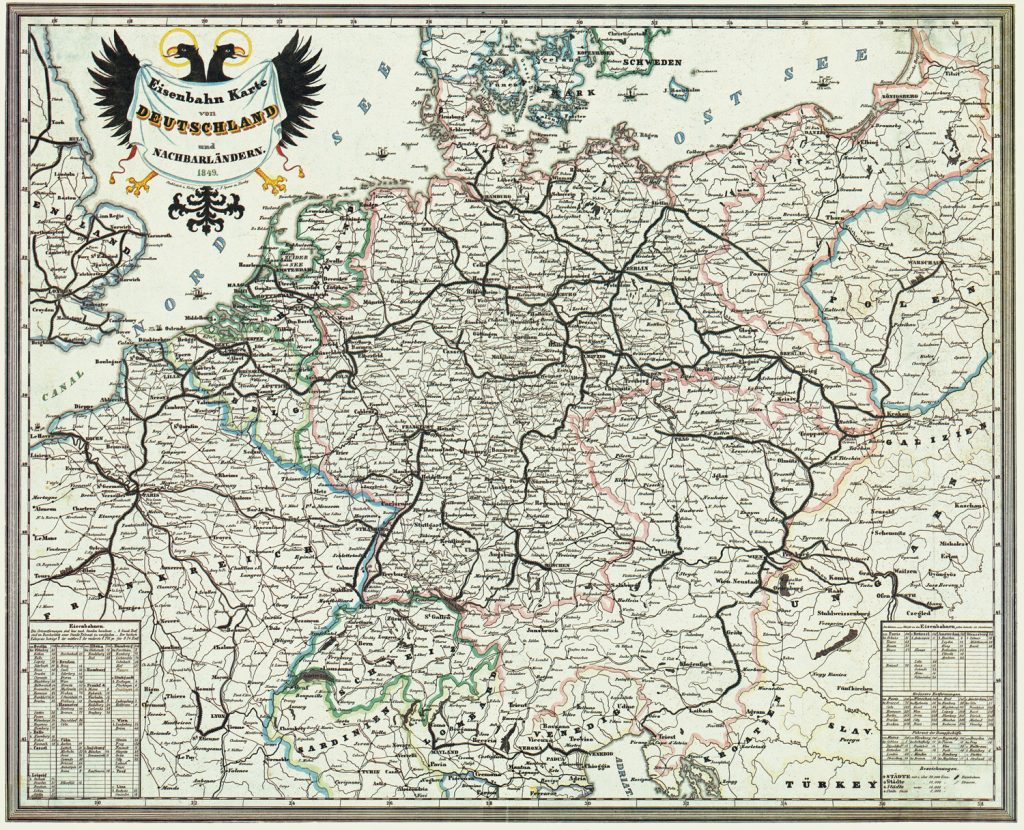

An excellent map of Rail and Roadways in the German Confederation and neighboring countries in 1848 is provided below.

Railway Map of Germany and Neighboring Countries 1849 [117]

Sources

Feature Photograph: The feature photograph is an amalgam of two maps. The map on the left is a map I created that shows the outline of the German Confederation and France with the three possible ports that John Speber possible considered for his voyage to America. The map on the right is from an historical German immigration pamphlet, referenced below, that provided information on inland routes of travel to ports of embarkation for German immigrants in the 1850s.

Source: Zimmermann, Gotthelf. Auswanderer-Karte und Wegweiser nach Nordamerika. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler’schen Buchh, 1853. Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, < www.loc.gov/item/98687132/ >.

[1] Page, Thomas W. “The Transportation of Immigrants and Reception Arrangements in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 19, no. 9, 1911, pp. 732. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1820349. Accessed 3 Feb. 2024.

[2] Page, Thomas W. “The Transportation of Immigrants and Reception Arrangements in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 19, no. 9, 1911, pp. 732. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1820349.

Wokeck, Marianne S., Trade in Strangers: The Beginnings of Mass Migration to North America, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999

Boyd, James D.An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

Moltmann, Günter. “Migrations from Germany to North America: New Perspectives.” Reviews in American History, vol. 14, no. 4, 1986, pp. 580–96. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2702202

Helbich, Wolfgang. “German Research on German Migration to the United States.” Amerikastudien / American Studies, vol. 54, no. 3, 2009, pp. 383–404. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41158447

[3] Boyd, James D., The Rhine Exodus of 1816/1817 within the Developing German Atlantic World, The Historical Journal, vol. 59, no. 1, 2016, Page 105. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24809839

[4] Boyd, James D., The Rhine Exodus of 1816/1817 within the Developing German Atlantic World, The Historical Journal, vol. 59, no. 1, 2016, Page 105. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24809839

Page, Thomas W. “The Transportation of Immigrants and Reception Arrangements in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 19, no. 9, 1911, pp. 732 – 735. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1820349.

Germany emigration and Immigration, FamilySearch Research Wiki, This page was updated 29 Feb 2024, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Germany_Emigration_and_Immigration

Wokeck, Marianne S.Trade in Strangers: The Beginnings of Mass Migration to North America, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999

[5] Boyd, James, Merchants of Migration: Keeping the German Atlantic Connected in America’s Early National Period, Updated August 22, 2018 , Immigrant entrepreneurship 1720 to the Present, https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entries/merchants-of-migration-keeping-the-german-atlantic-connected-in-americas-early-national-period/.

Boyd, James,The Rhine Exodus of 1816/17 within the Developing German Atlantic World, The Historical Journal, vol. 59, no. 1, 2016, pp. 99–123. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24809839

Wokeck, Marianne S., Trade in Strangers: The Beginnings of Mass Migration to North America, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999

[6] Cohn, Raymond L., and Simone A. Wegge. “Overseas Passenger Fares and Emigration from Germany in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Social Science History, vol. 41, no. 3, 2017, pp. 393–413. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/90017919

[7] Steamships were introduced on the inland waterways in Europe during the early 19th century. The introduction of steamships on inland waterways coincided with the period of industrialization in Europe, where the development of new shipbuilding materials such as iron and steel, along with the steam engine, enabled the construction of larger vessels capable of faster navigation independent of natural forces like wind and currents.

By the end of the 19th century, steamships had become a significant part of the inland waterway system in Europe, with the Rhine, Danube, and Elbe rivers being major routes for such navigation. Steam-driven tugboats with barges in tow were the main ships used in inland navigation. Self-propelled ships were also employed for special cargoes or on certain waterways.

Steamship, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 28 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steamship

“Shipping, Inland Waterways, Europe .” History of World Trade Since 1450. . Encyclopedia.com. (February 22, 2024). https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/shipping-inland-waterways-europe

[8] Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951.

James Boyd, Merchants of Migration: Keeping the German Atlantic Connected in America’s Early National Period, Updated August 22, 2018 , Immigrant entrepreneurship 1720 to the Present, https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entries/merchants-of-migration-keeping-the-german-atlantic-connected-in-americas-early-national-period/.

Immigration to the United States, 1851-1900, U.S. History Primary Source Timeline, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/rise-of-industrial-america-1876-1900/immigration-to-united-states-1851-1900/

Boyd, James , Merchants of Migration: Keeping the German Atlantic Connected in America’s Early National Period, Updated August 22, 2018 , Immigrant entrepreneurship 1720 to the Present, https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entries/merchants-of-migration-keeping-the-german-atlantic-connected-in-americas-early-national-period/.

[9] Boyd, James, Merchants of Migration: Keeping the German Atlantic Connected in America’s Early National Period, Updated August 22, 2018 , Immigrant entrepreneurship 1720 to the Present, https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entries/merchants-of-migration-keeping-the-german-atlantic-connected-in-americas-early-national-period/.

Hoerder, Dirk. “The Traffic of Emigration via Bremen/Bremerhaven: Merchants’ Interests, Protective Legislation, and Migrants’ Experiences.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 13, no. 1, 1993, pp. 76. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27501115

Page, Thomas W. “The Transportation of Immigrants and Reception Arrangements in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 19, no. 9, 1911, pp. 738. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1820349

Boyd, James, The Rhine Exodus of 1816/1817 within the Developing German Atlantic World, The Historical Journal, vol. 59, no. 1, 2016, Page 105. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24809839

A New Surge of Growth, Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/german/new-surge-of-growth/

Boyd, James D., An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

[10] Boyd, James D.,An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

Moltmann, Günter. “Migrations from Germany to North America: New Perspectives.” Reviews in American History, vol. 14, no. 4, 1986, pp. 580–96. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2702202

Helbich, Wolfgang. “German Research on German Migration to the United States.” Amerikastudien / American Studies, vol. 54, no. 3, 2009, pp. 383–404. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41158447

Page, Thomas W. “The Transportation of Immigrants and Reception Arrangements in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 19, no. 9, 1911, pp. 738. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1820349

Cohn, Raymond L., and Simone A. Wegge. “Overseas Passenger Fares and Emigration from Germany in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Social Science History, vol. 41, no. 3, 2017, Pages. 394, 412. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/90017919

Hoerder, Dirk. “The Traffic of Emigration via Bremen/Bremerhaven: Merchants’ Interests, Protective Legislation, and Migrants’ Experiences.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 13, no. 1, 1993, pp. 76. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27501115

[11] Hansen, Marcus Lee., The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951

Boyd, James, Merchants of Migration: Keeping the German Atlantic Connected in America’s Early National Period, Updated August 22, 2018 , Immigrant entrepreneurship 1720 to the Present, https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entries/merchants-of-migration-keeping-the-german-atlantic-connected-in-americas-early-national-period/.

[12] Hansen, Marcus Lee , The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Page 172

[13] Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Page 172 – 173

[14] Mille, Michael, Europe and the Maritime World: A Twentieth-Century History, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012, Page 25, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139170048.001

[15] Michon , Bernard, European Commercial Ports, Encyclopédie d’histoire numérique de l’Europe [online], ISSN 2677-6588, published on 22/06/20 , consulted on 01/02/2024. Permalink : https://ehne.fr/en/node/12347

[16] This map is a revision of a wonderful map originally found as “Map 1 Hamburg–Le Havre range and its waterways”, from Michael Mille, Europe and the Maritime World: A Twentieth-Century History, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012, Page 27, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139170048.001

I have removed the canals that were depicted in the original map to illustrate the extensive reach of the waterways from each of these principal ports. Many of the canals that were originally portrayed in Mille’s map were also completed after John Sperber’s journey to America.

[17] Michon , Bernard, European Commercial Ports, Encyclopédie d’histoire numérique de l’Europe [online], ISSN 2677-6588, published on June 6 2020, consulted on 01/02/2024. Permalink : https://ehne.fr/en/node/12347

[18] “…(M)ost of the emigration of this period was towards the United States, as the statistics from Bremen confirm and Hamburg in 1850. If we compare these statistics with those … (for) … Le Havre, we see that 98% of departures from Bremen are for the United States, while this figure is 93% for Le Havre and 81.2% for Hamburg. Bremen and Le Havre therefore appeared at this time as ports of emigration to the United States, while Hamburg is more diversifies, and that in France. Bordeaux or Saint-Nazaire are more oriented towards South America.“

“Si l’on compare ces statistiques avec celles evoquees plus haut concernant le port du Havre, on s’aperçoit que 98 % des departs de Breme se font pour les Etats-Unis, alors que ce chiffre est de 93 % pour Le Havre et 81,2 % pour Hambourg. Breme et Le Havre apparaissent done a cette epoque comme des ports d’emigration vers les Etats-Unis, alors que Hambourg est plus diversifie, et qu·en France. Bordeaux ou Saint-Nazaire sont plus orientes vers I’ Amerique du Sud.”

Braunstein, Jean, L’émigration allemande par le port du Havre au XIXe siècle (German Emigration through the Port of Le Havre in the 19th Century), Table: Emigrants Allemands Embarques Au Havre (1830 – 1870), Annales de Normandie, 1984, Page 103, https://www.persee.fr/doc/annor_0003-4134_1984_num_34_1_6382

Data in the Table is from: Braunstein, Jean, L’émigration allemande par le port du Havre au XIXe siècle (German Emigration through the Port of Le Havre in the 19th Century), Table: Emigrants Allemands Embarques Au Havre (1830 – 1870), Annales de Normandie, 1984, Page 103, https://www.persee.fr/doc/annor_0003-4134_1984_num_34_1_6382

[19] Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Page 195

[20] Evans, Nichols J., Work in progress: Indirect passage from Europe Transmigration via the UK, 1836–1914, 2001, Journal for Maritime Research, 3:1, 70-84, DOI: 10.1080/21533369.2001.9668313, Published online: 08 Feb 2011 https://doi.org/10.1080/21533369.2001.9668313

[21] Source: Zimmermann, Gotthelf. Auswanderer-Karte und Wegweiser nach Nordamerika. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler’schen Buchh, 1853. Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/98687132/

[22] Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Page 194

[23] Evans, Nicholas J., Indirect passage from Europe Transmigration via the UK, 1836-1914, Journal for Maritime Research, June 2001, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/21533369.2001.9668313

[24] This map is an annotated version of:

Blank map of Europe 1860, Wikimedia Commons,. This map is part of a series of historical political maps of Europe. All maps by Alphathon and based upon Blank map of Europe.svg , https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blank_map_of_Europe_1860.svg

The German Confederation was breifly interrupted by the German Empire (1848-1849). The external boundaries basically stayed the same. The German Empire was a proto-state which attempted to unify the German states within the German Confederation It was created in the spring of 1848 during the German revolutions by the Frankfurt National Assembly. The German Empire’s controlled territories and its claims are noted in the darker color in the map below while the claimed territories are essentially the remaining states in the German Commonwealth.

German Empire (1848-1849)

Map source: Alphathon, The German Empire in 1849, a revolutionary German state that attempted to unify Germany in 1848, 4 February 2007, Wkimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:German_Empire_(1849).png

[25] Page, Thomas W. “The Transportation of Immigrants and Reception Arrangements in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 19, no. 9, 1911, pp. 732–49. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1820349

[26] In 1815, the formation of the German Confederation was a pivotal event for the German states. Established by the Congress of Vienna, the Confederation replaced the Holy Roman Empire, which had been dissolved in 1806. This loose political association comprised 39 German states and was designed for mutual defense, lacking a central executive or judiciary.

The Confederation was dominated by Austria, reflecting the balance of power desired by the Congress of Vienna to prevent any single state, particularly Austria or Prussia, from dominating the German territories. The Confederation itself was characterized by its weak structure. Most sovereignty rights remained with the individual states. Major decisions required agreement from all states which made it difficult to enact reforms. The Confederation played a role in the political and economic landscape of the German states from 1815 to 1866.

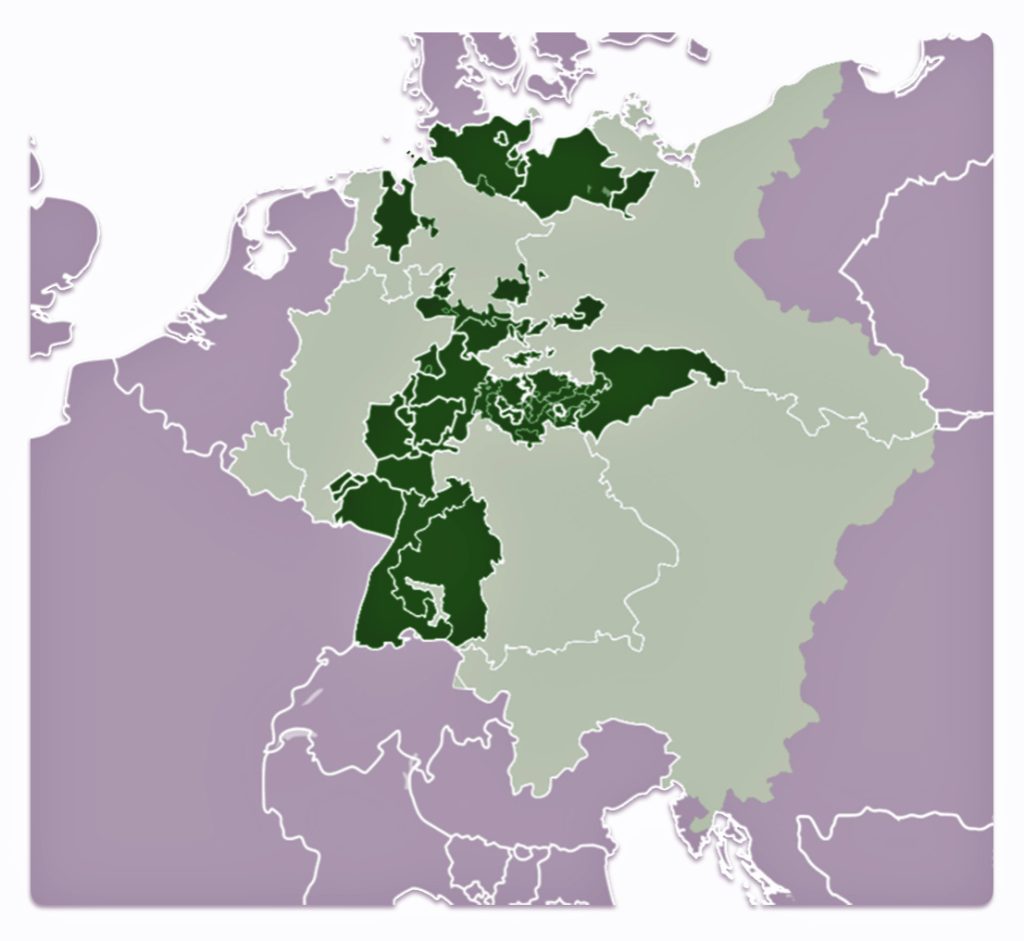

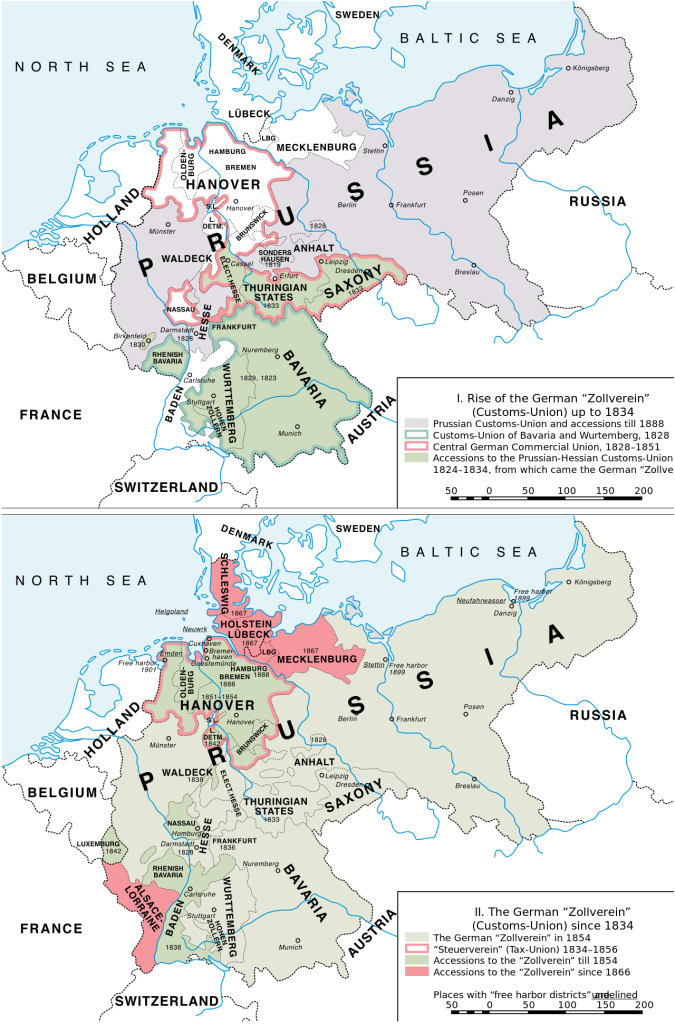

The German Zollverein

One of the Confederation’s notable achievements was the establishment of the Zollverein in 1834. The Zollverein was a customs union, excluding Austria, that facilitated economic cooperation and growth among the member states. This economic integration was a significant factor in the growing sense of German national identity and the push towards unification. The Zollverein facilitated laying the groundwork for the construction of railroads, the use of steamships on the inland waterways, and improvement of roads and canals.

Ploeckl, Florian, A Novel Institution: The Zollverein and the Origins of the Customs Union, Discussion Paper No. 2019-05, November 2019, Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence in International Trade and Global Affairs, Discussion Papers, The University of Adelaide, https://iit.adelaide.edu.au/ua/media/390/Discussion%20Paper%202019-05%20Florian%20Ploeckl%20131119.pdf

Price, Arnold H. , Evolution of the Zollverein, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1949

Henderson, W.O., The Zollverein. 3rd ed., London: F. Cass, 1984

Economic changes and the Zollverein, Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/place/Germany/Bismarcks-national-policies-the-restriction-of-liberalism

Zollverein, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 8 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zollverein

[27] Robert, Lee, ‘Relative backwardness and long-run development; economic, demographic and social changes’, in J. Breuilly (ed.), Nineteenth-Century Germany. Politics, Culture and Society 1780-1918 (London, 2001), Page 82

[28] Hoerder, Dirk. “The Traffic of Emigration via Bremen/Bremerhaven: Merchants’ Interests, Protective Legislation, and Migrants’ Experiences.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 13, no. 1, 1993, pp. 68. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27501115

[29] Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Atlantic Migration 1607-1860. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, Page 187-188; 288-290

[30] Boyd, James D., An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf Page 155 & Pages 133-134

[31] Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Page 186

[32] Boyd, James D., An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf Page 155 Page 121-122

Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951. Page 191