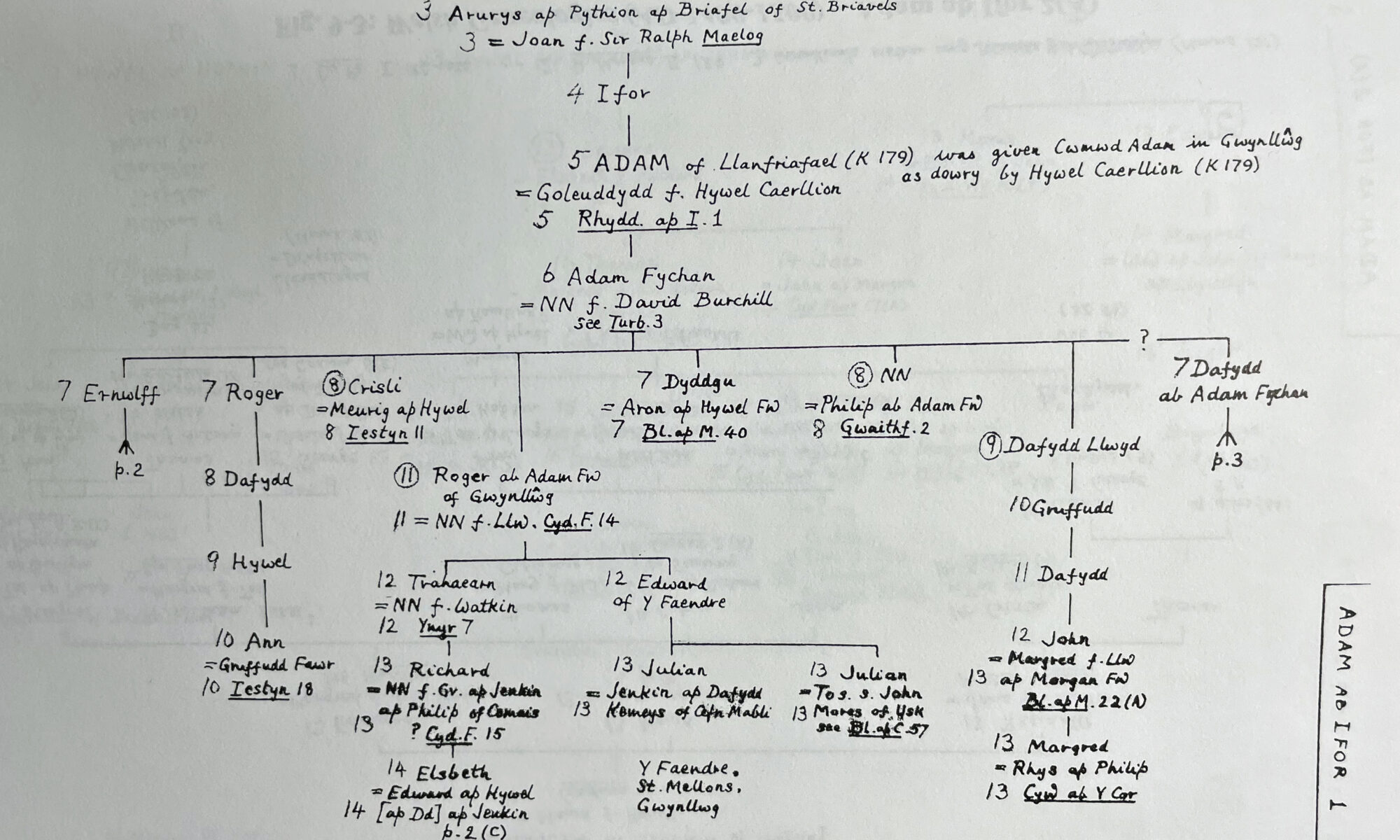

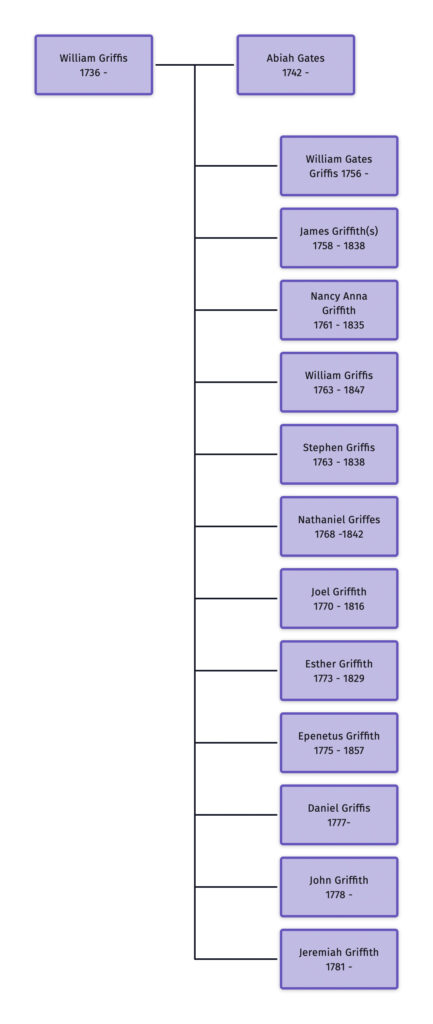

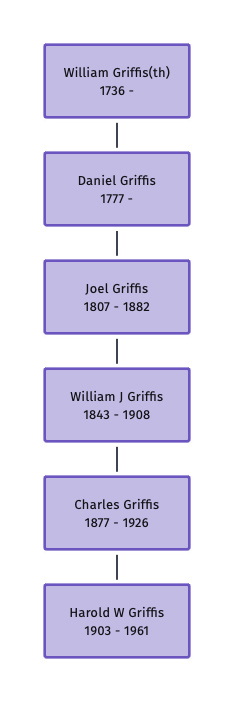

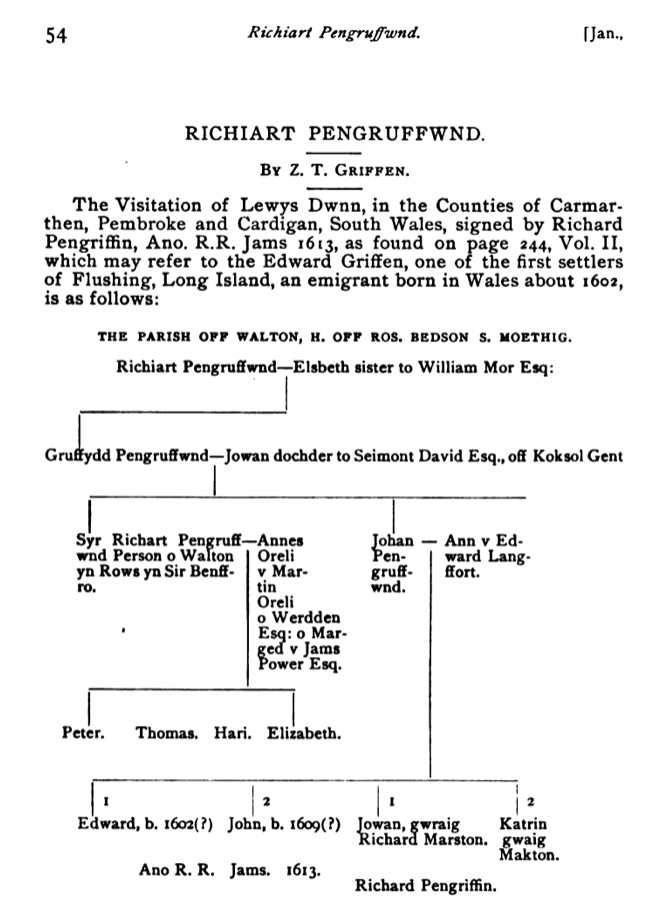

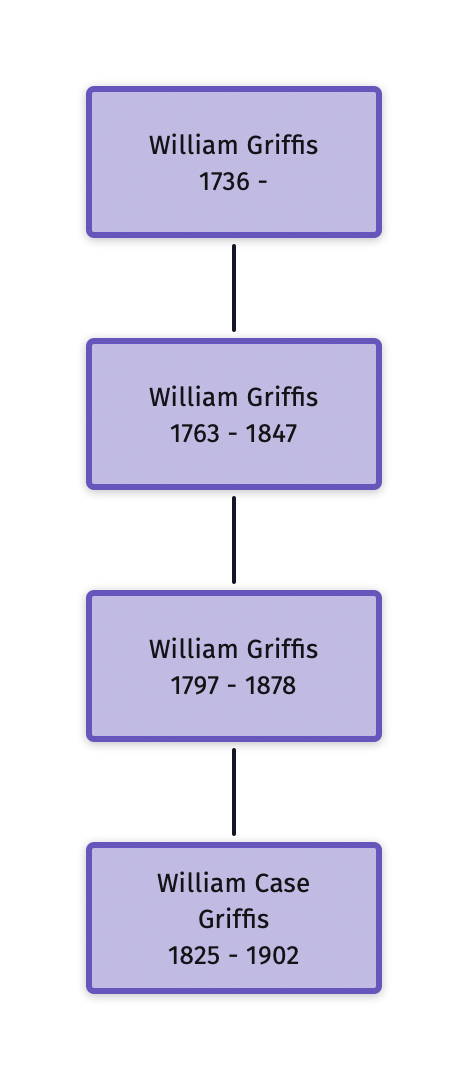

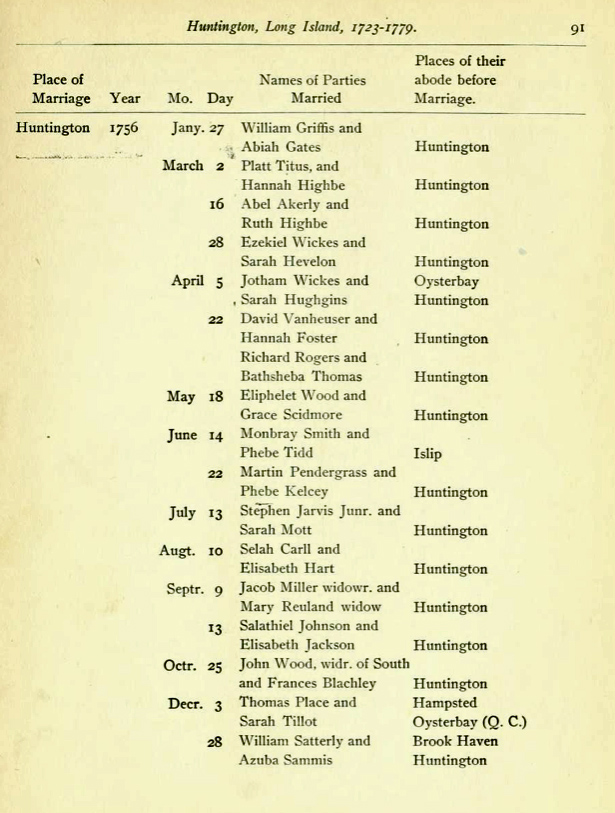

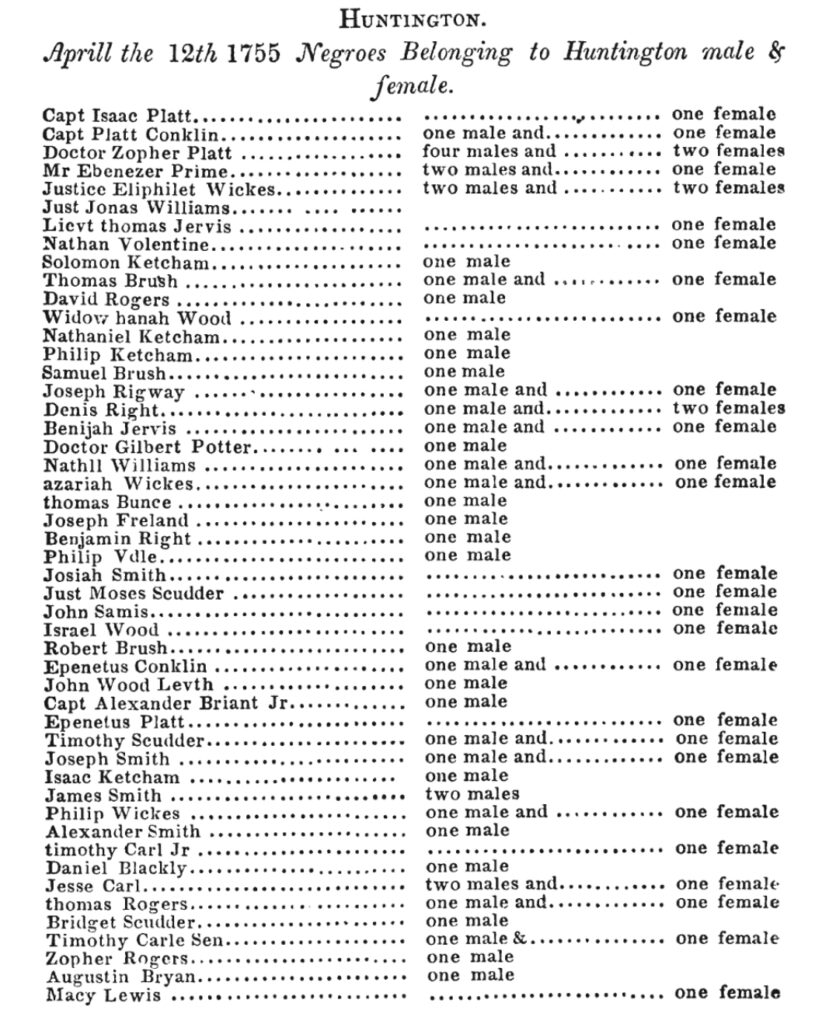

At a certain point in my research on tracing the Griff(ith)(is)(es) family surname, I reached a ‘brick wall’ regarding its origin in Europe. Despite written references of oral history in family genealogies that indicate the surname and its respective fore-bearers came from Wales [1], there was no actual evidence or corroboration of this fact based on my traditional genealogical research.

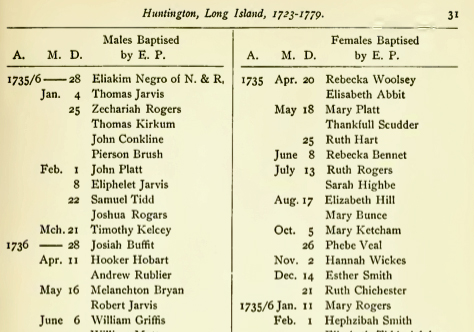

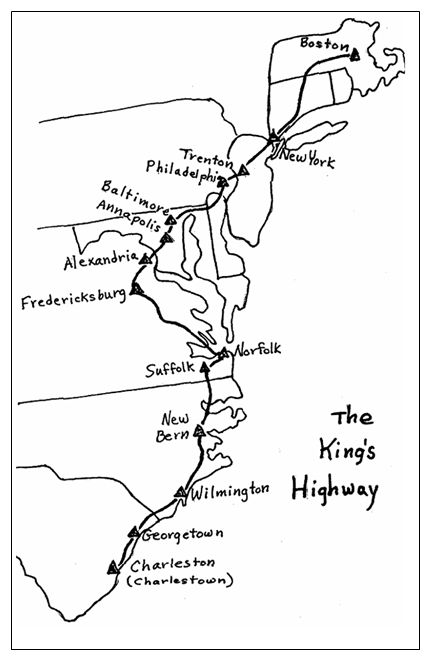

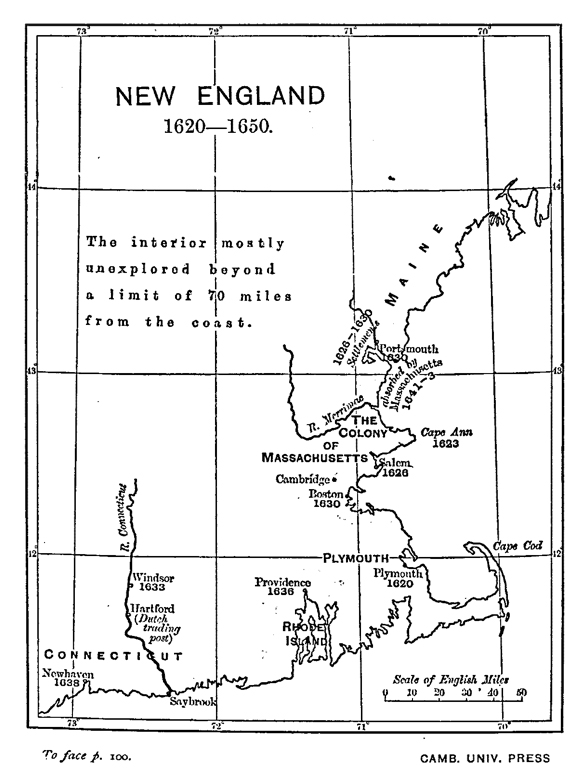

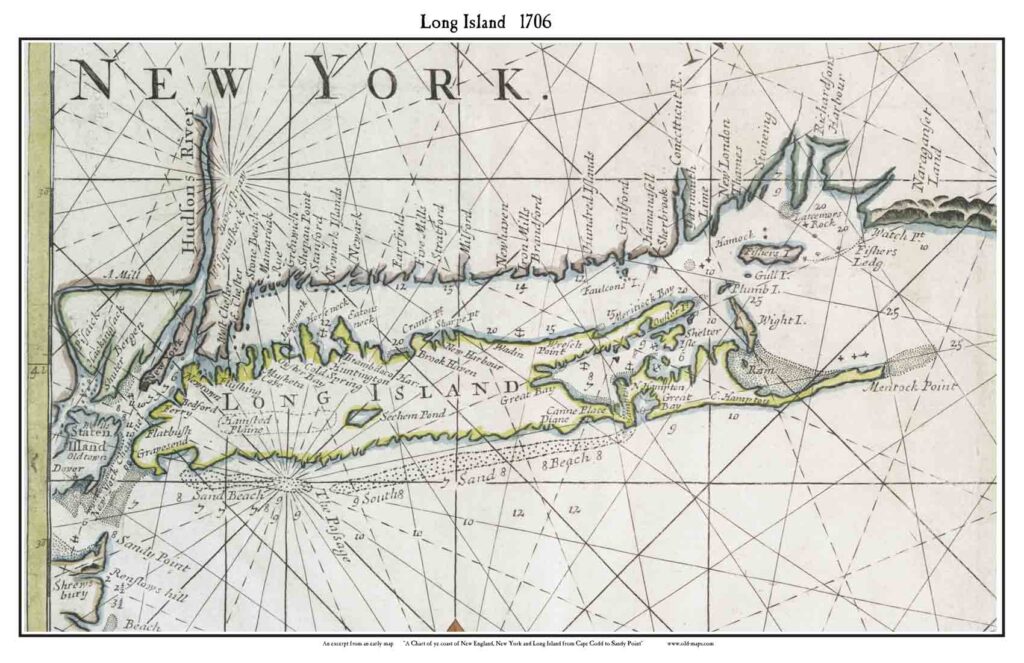

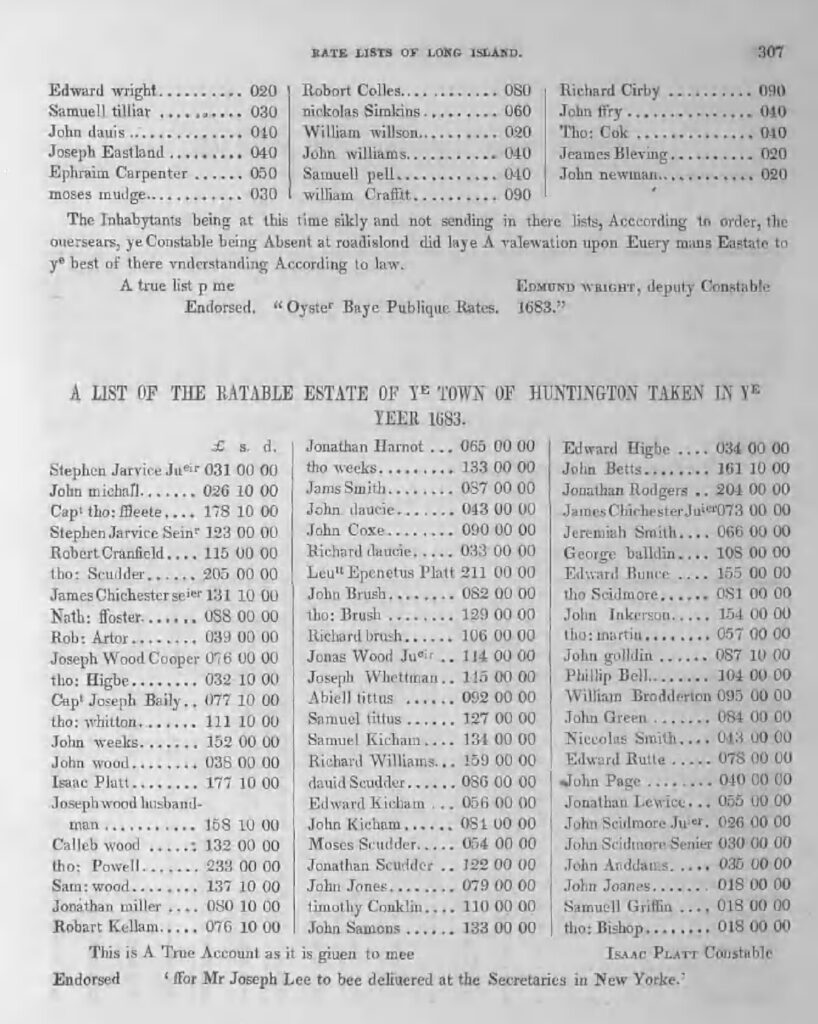

Based on my current traditional genealogical research, it is assumed that the father or grandfather of William Griffis (the earliest documented male with the surname) emigrated to the British colonies, possibly from southern Wales. It is believed that this person and possibly family traveled from Bristol or London and arrived to Boston, Salem or another northern port. It is conceivable that they then traveled to one of the settlements from Massachusetts or Connecticut to Huntington, Long Island. This would imply that William’s descendants conceivably emigrated between the 1640 to the late 1600’s or possibly the early 1700’s.

The lack of tangible leads through traditional genealogical research sources and the advances of commercial direct-to-consumer DNA genealogical tests lead me to looking into Y-DNA genetic tests as a possible avenue to gain insights and possible leads on identifying information about the family surname line of descendants.

Y-DNA: Linking Three Periods of Geneaological Research

“DNA testing for genealogy has become really popular in the past few years, and incredible discoveries are being made through DNA testing that in many cases, could not be made any other way. … Y-DNA testing also provides great genealogical value, and while more limited in scope, it can be a tremendous aid in breaking through more distant genealogical brick walls.” [2]

“In most cultures Y-DNA tracks the same line of inheritance as surnames. A Y-DNA test can be used to answer questions such as whether two men with the same surname from different parts of the country share a common ancestor, or whether two variant spellings of a surname have a common root. You will get the most out of a Y-DNA test if there is already a structured one-name study for your surname.” [3]

Based on the limitations and the realistic expectations of what Y-DNA tests can find [4], I had a few expectations of what I might be able to find by taking a Y-DNA test:

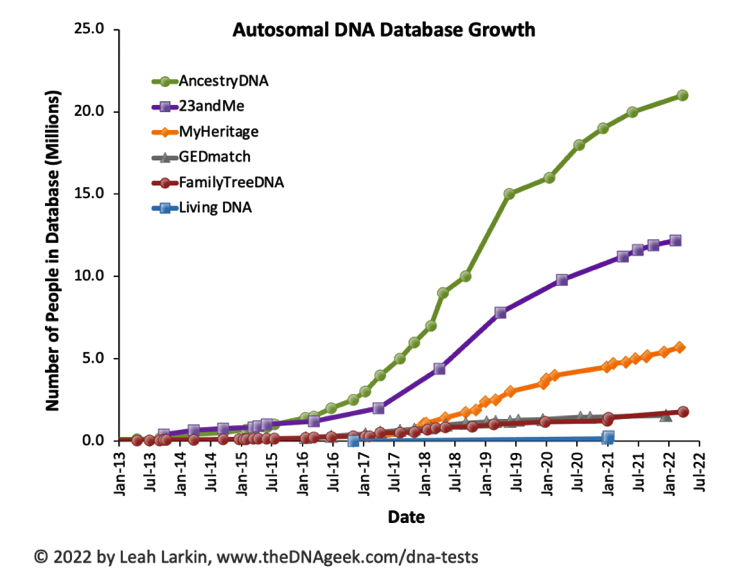

- Finding genealogical matches would be slim. The size of current databases of Y-DNA testers for genealogical matching is relatively small. The probability of finding matches is obviously related to the size of the population that has completed a Y-DNA test with the particular company that you are utilizing. While DNA testing has appreciably increased over the past 10 years, Y-DNA testing has specifically increased at a lower rate than the popular ‘ethnic heritage’ tests. Like fly fishing, I knew my ability to snag a ‘lead’ through Y-DNA analysis might be slim but a catch would be delightful.

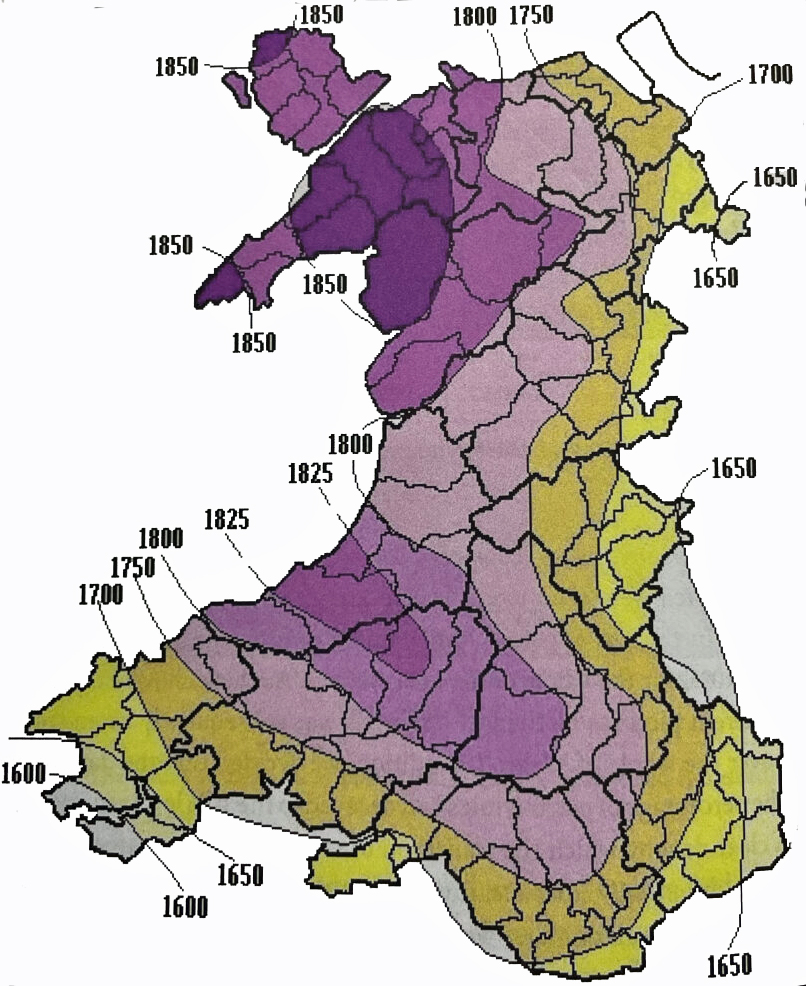

- Finding genealogical matches with different surnames. Since the Griff(is)(es)(ith) surname was purportedly a Welsh surname, the use of surnames did not become firmly established in certain parts of Wales until the late 1700’s to mid 1800’s. Based on my traditional genealogical research I knew the Griffis family line had three spellings of the surname (Griffis, Griffith, and Griffes) in America. Y-DNA tests could increase my chances of finding genetically related ancestors with different surnames in Europe.

- Finding genealogical matches currently confirmed through traditional research. The Y-DNA test may find matches with individuals that have already been documented in my family tree. I might be able to find additional clues to male family members that are descendants of William Griffis.

- Finding genealogical matches that point to Wales. If I am able to locate genealogical matches, regardless of surname, there could be a chance that they would lead to family trees that locate descendants in Wales. Obviously, one’s ancestors could be Welsh and have lived in London or other parts of the British Isles.

- Identify unknown ancestors and lineages in timelines where no records exist. The DNA test could narrow the search of male ancestors to specific genetic Y-DNA lines and identify the branching in these paternal lines.

- Identify ancient groups and migration patterns associated with the genertic paternal line. By choosing an appropriate Y-DNA test, I should be able to obtain information about ‘deep ancestry’. I should be able to obtain information on the patrilineal line at a higher, anthropological level and gain insights into the population level origins of the lineage.

With these expectations in mind, I did a comparative review on various “direct to consumer” types of Y-DNA tests. [5] I decided to complete a “Big Y” 700 DNA test from FamilyTreeDNA. [6]

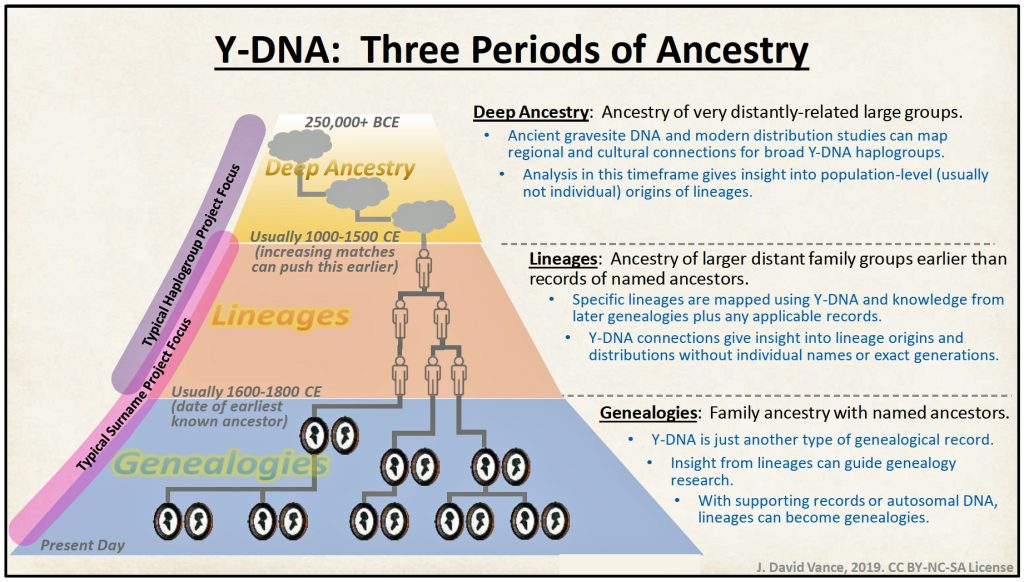

The Big Y 700 test provides the capability of obtaining genealogical information on what David Vance calls the “three periods of ancestry” (as depicted in the illustration below). Vance’s ‘three periods of ancestry’ model provides a framework to visualize how various levels of genealogy are integrated through recent technical and scientific breakthroughs related to genetic genealogy.

Illustration 1: Y-DNA: Three Periods of Ancestry

Source: Page 13 of a readable transcript of the narration in a YouTube at https://drive.google.com/open?id=1CdU…, The video is by J. David Vance, DNA Concepts for Genealogy: Y-DNA Testing Part 1, 10 Oct 2019, https://youtu.be/RqSN1A44lYU

On the bottom of the illustration are the family genealogies that have been created through traditional genealogical research. At the top of the illustration is ‘deep ancestry’, a realm of genealogical research that has been documented through various studies of ancient cultures, archeological studies, and genetic testing of ancient human remains.

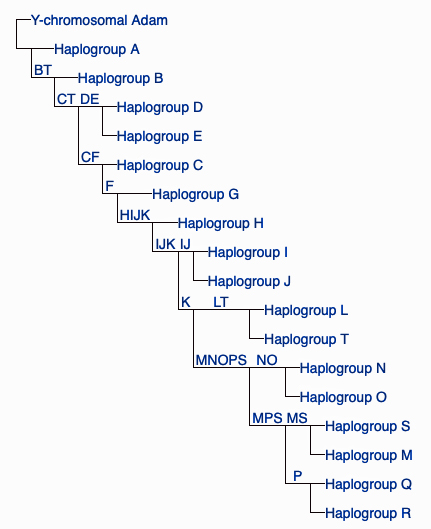

Recent developments in paleo-genetic science allows us to see what Y-DNA mutations occurred among groups in various geographic areas, what they have in common and where they differ. These developments and discoveries have enabled researchers to reconstruct a timeline and genetic tree of when different genetic groups, called haplogroups, went their separate ways. General ancient haplogroups and specific branches of haplogroups ( called subclades) can be predicted from genetic signatures obtained from ancient bone fragments and mapped out in what is known as a haplotree. The results of these paleo-genetic studies have generated new information and informed theories for where and when certain Y-DNA was carried by certain groups and cultures, and more knowledge is gleaned from ancient digs and genetic technological innovations that enable the mapping out the locations by points of time of where Y-DNA had spread.

An haplogroup is a genetic population group of people who share a common ancestor through a unique series of Y-DNA or mitochondria DNA genetic mutations through time. A haplotree is like a family tree but is based on the tracing of genetic mutations on the Y chromosome. Haplogroups can be traced through the maternal and paternal lines. [7] However, unlike generations in a family tree, the branches in a haplotree can represent hundreds or thousands of years based on the variable nature of when genetic mutations occur.

The following phylogenic diagram depicts the major branches of the Y-DNA haplotree.

Illustration 1: The Major Branches of the Y-DNA Haplotree

“. . . in between deep ancestry and the genealogy of named ancestors, we have what I’m calling “lineages” for lack of a better term. These are genealogies if you will but of unnamed ancestors over a period of time when you have known interconnections.

“The generations may be estimated, the timeframes may be estimated, but you know that the connections happened because the Y-DNA tells you that there were mutations that were passed on by men who lived in those time periods and those men had descendants who had further mutations and so you can map the family relationships between those men even if you can’t ever name them. ” [8]

The BigY 700 test is the most comprehensive in a variety of ways and provides information on all three ancestry levels. It is primarily designed to explore deep ancestral links. This test examines thousands of known Y-DNA branch markers as well as millions of places where there may be new Y-DNA branch markers. As the Y haplotree grows, the genetic markers, Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) [9] that have been tested in a Big Y-700 test and are identified with individuals that have taken the test will gradually be placed on the Y- DNA Haplotree, furthering individual genealogical research.

The Big Y test is not technically one test but a package of Y-DNA tests. While the Y-DNA 700 test provides information on ‘deep ancestry’ and ‘lineages’, the purchase of the Big Y test includes other separate tests that provide potential ‘match’ results with the company’s other Y-STR tests which touch on the genealogical level, such as the Y-37, Y-67, and Y-111 tests. The “Y-” numbers refer to the number of genetic Short Tandem Repeat (STR) [10] markers that are analyzed and compared with other individuals who have taken the test. The results of these tests are included with the Big Y test. [11] STRs and SNPs are discussed later in the story.

Every male’s Y-DNA carries within it the mutations that formed in his male ancestors going back thousands of years. Deep ancestry analysis focuses on the population level origins and distributions of the haplogroups based on these genetic mutations. While a handful of these mutations have been identified before the recent explosion of DNA testing, over a million of them have been identified in the last ten years. Y-DNA testing shows that each male carries several hundred thousand of those identifiable mutations that represent our respective branches of the haplotree. These mutations ultimately connect every male on the planet back to the earliest ancestor of all males who have tested thus far. This earliest ancestor was not the first man who ever lived, he is just the most recent common ancestor of all men who have had their Y-DNA tested. There may certainly have been older men who lived but they have not left any paternal descendants or ancient remains have yet to be found to identify someone who is older.

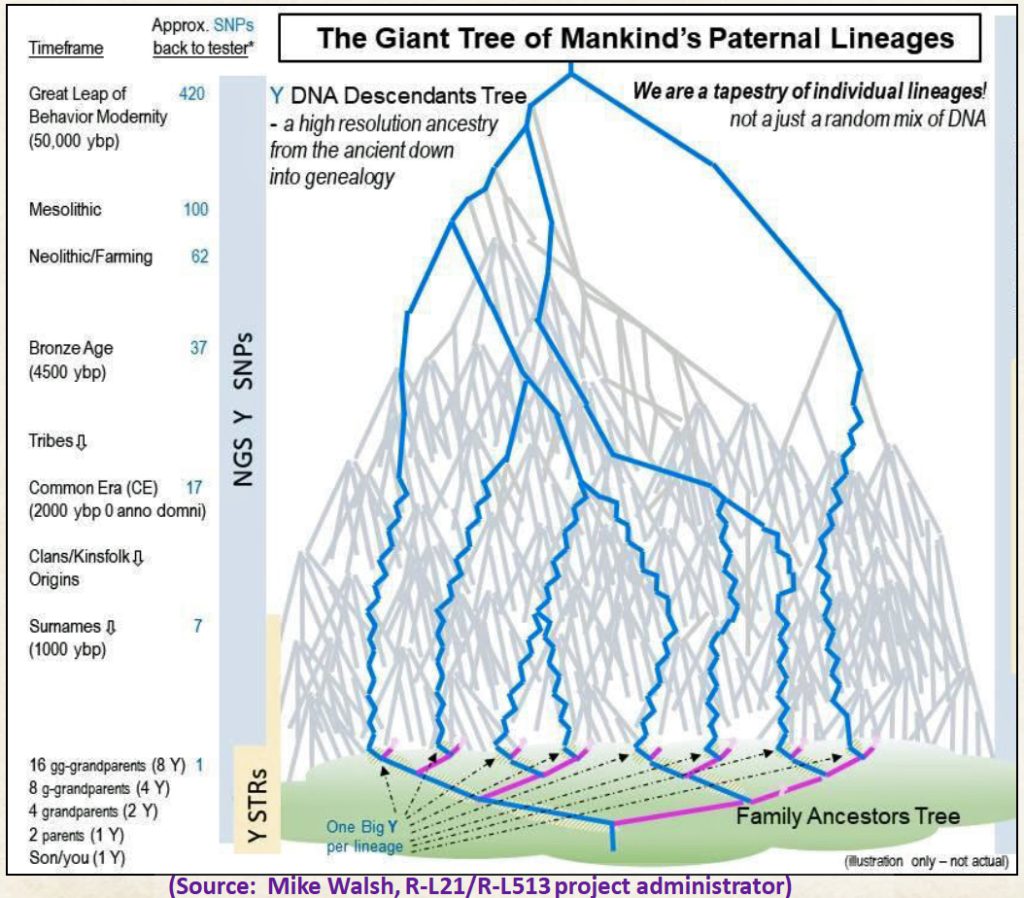

As indicated in the illustration 2 below, the paternal line of all men is represented in a genetic ancestral tree – the YDNA haplotree. The various branches in this haplotree are marked by unique Y-DNA genetic SNP mutations found on the Y chromosome. Each mutation defines a branch or sub-branch of the haplotree.

Illustration 2: TheY DNA Haplotree from Ancient to Recent Genealology

Click for larger view.

Coupled with the Y-STR tests, Family Tree DNA offers a wide variety of Y-DNA Group Projects to help further research goals. The group projects are associated with specific branches of the Haplotree, geographical areas, surnames, or other unique identifying criteria. Based on their respective area of focus, the research groups have access to and the ability to compare Y-DNA results of fellow project members to determine if they are related. These projects are run by volunteer administrators who specialize in the haplogroup, surname, or geographical region that one may be researching.

For my research on the Griff(is)(es)(ith) family, upon the receipt of my Y-DNA test, I joined five Y-DNA Family Tree DNA based projects to assist in my ongoing research:

- The GRIFFI(TH,THS,N,S,NG…etc) surname project is intended to provide an avenue for connecting the many branches of Griffith, Griffiths, Griffin, Griffis, Griffing and other families with derivative surnames. The Welsh patronymic naming system, practiced into the latter 18th century, makes this task more difficult. Evan, Thomas, John, Rees, Owen, and many other common Welsh names may share common male ancestors. (820 members as of the date of this article).

- The G-L497 project includes men with the L497 SNP mutation or reliably predicted to be G-L497+ on the basis of certain STR marker values. The L-497 is a branch or subclade of the G-haplogroup (M201+). The project also welcomes representatives of L497 males who are deceased, unavailable or otherwise unable to join, including females as their representatives and custodians of their Y-DNA. The primary goal of the project is to identify new subgroups of haplogroup G-L497 which will provide better focus to the migration history of our haplogroup G-L497 ancestors. (2,326 members as of the date of this article.)

- The G-Z6748 project is a Y-DNA Haplogroup Project for a specific branch that is a more recent, ‘downstream’ branch from the L-497 branch of the G haplotree. It is a project work group that is a subset of the L497 work group. The G-Z6748 subclade or brand appears to be a largely Welsh haplogroup, though extending into neighboring parts of England. (33 members as of the date of the article)

- The Welsh Patronymics project is designed to establish links between various families of Welsh origin with patronymic style surnames. Because the patronymic system (father’s given name as surname) continued until the 19th century in some parts of Wales, there was no reason to limit this study to a single surname. (1,572 members as of the date of this article.)

- The Wales Cymru DNA project collects the DNA haplotypes of individuals who can trace their Y-DNA and/or mtDNA lines to Wales (the reasoning by many researchers being that there was less genetic replacement from invaders there than elsewhere, excepting small inaccessible islands and similar locales). Tradition holds that the Celts retreated as far west in Wales as possible to escape invading populations. This project seeks to determine the validity of the theory. This project is open to descendants from all of Wales. (842 members as of the date of this article.)

Summary of the Story

The results of completing the Y-DNA tests have currently led to the following results:

Deep Ancestry Results: The Griff(is)(es)(ith) patrilineal line belongs to the G Haplogroup. The G haplogroup was one of the earliest branches of Y-DNA to emerge from Africa. My test Y-DNA results also identified a new ‘recent’ terminal branch on the G haplogroup tree which was named Haplogroup G-BY211678. G-BY211678 represents a man who is estimated to have been born around 500 years ago, plus or minus 250 years. This corresponds to about 1500 CE with a 95 percent probability he was born between 1285 and 1685 Common Era (CE). G-BY211678’s paternal line was formed when it branched off from G-Y132505 about 800 years ago, plus or minus 300 years.

The Y-DNA Griff(is)(es)(ith) descendants were part of the second wave to populate Europe. The G Haplogroup were Neolithic Europeans who were descendants of Neolithic farmers from the Anatolia region, among some of the earliest groups in the world to practice agriculture. The percentage of haplogroup G decendants among available samples from Wales is overwhelmingly from the G-P303 subclade of the G branch. Such a high percentage is not found in nearby England, Scotland or Ireland. [12]

Lineage Ancestry Results: It is highly likely the paternal line of the family ‘recently’ lived in the area known as Wales and may have lived on the southern coast of what is Wales. The paternal descendants lived in this area about 1,600 years before the present. I have come to this tentative conclusion based on the work of the project administrator for the G-Z6748 project. The project administrator correlated information of Y-DNA test results with information on reported locations of the most distance ancestor for project members with similar DNA compositions. The geographic information is from project group members and is based on their ability to trace their ancestors back to specific geographical areas in southern Wales based on traditional genealogical research.

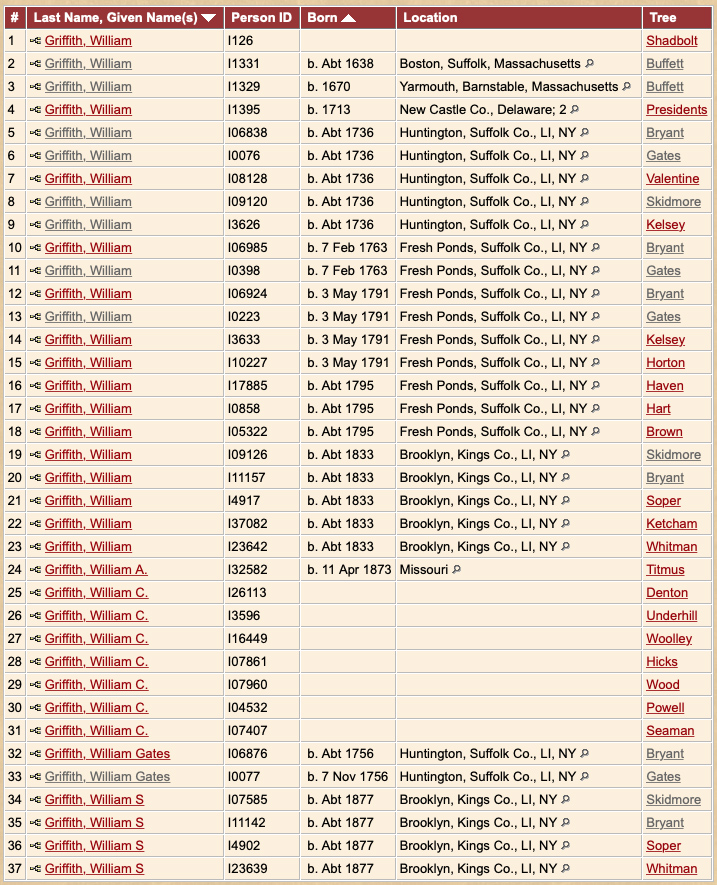

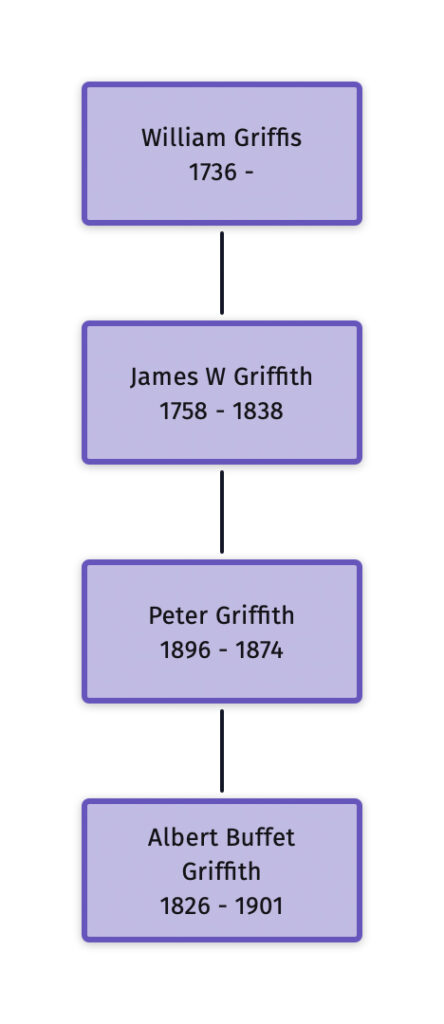

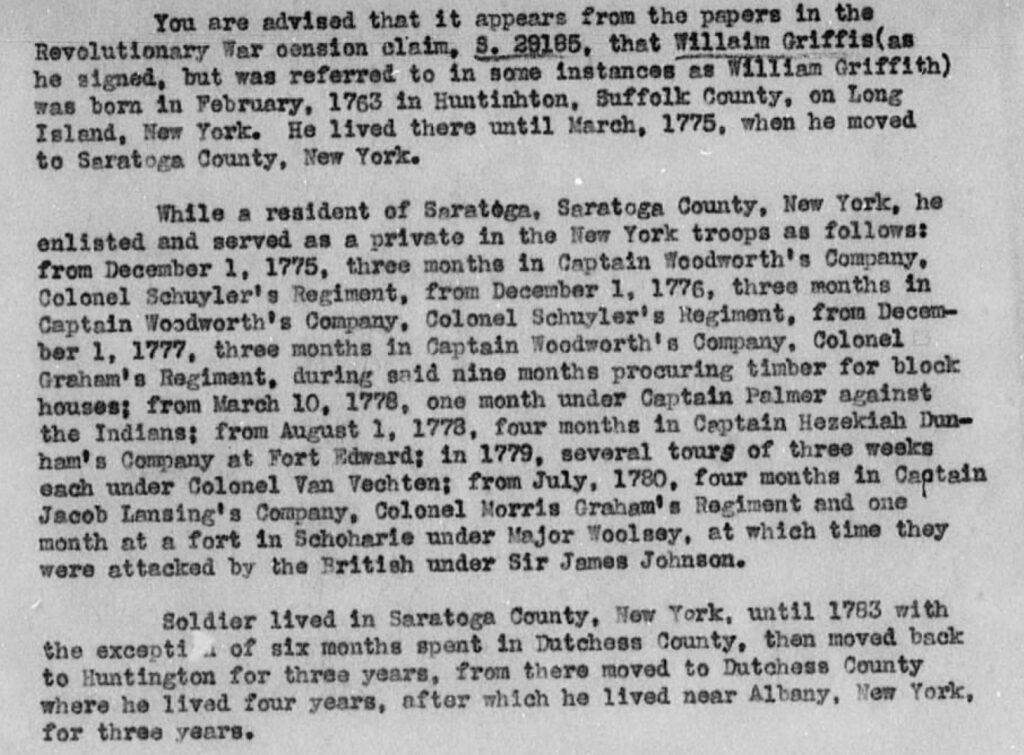

Genealogical Results: The results of the Y-DNA testing thus far have also confirmed one distant Griffith relative, Henry Vieth Griffith (1923 – 2017), who was originally discovered through traditional research. Henry Vieth Griffith is my fifth cousin once removed. Henry’s third great grandfather was James Griffis. James Griffis was the second oldest son of William Griffis.

The ‘What’ & ‘How’Genetic Genealogy Works is a Challenge to Comprehend

The process of Y-DNA testing was personally a learning experience in terms of understanding and interpreting DNA genealogical results. The research methods associated traditional genealogy are relatively straightforward, involving the search and assessment of various historical documents. Genetic ancestry, on the other hand, requires one to master a new set of terms and gain an understanding of how to interpret DNA results.

The literature of genetic genealogy ranges from the esoteric scientific peer reviewed articles, to DNA company based blog articles to popular magazine / social network stories. The scientific and test company based articles are at times difficult to understand. The DNA company based literature is frequently inadequate in demystifying the technical components of how results are determined and interpreted. The DNA company based literature also is limited in terms of explaining how company results differ from other companies. The popular stories are often deficient in explaining the science of DNA. The results are often labeled differently, based on which organization is managing the results.

Despite the dramatic technical advances in testing and explosive growth of DNA databases and results, even after 20 years, the field of genetic genealogy is still relatively young, ever changing and akin to the “wild, wild west”. At the same time, discoveries are frequent.

“The field of ancestry DNA testing is a work of progress. Companies continue to expand their population reference panels, refine their algorithms and improve on the markers used in a sample to infer ancestry. Customer demand may be ahead of what companies can offer. “ [13]

Because the methods for undertaking DNA genealogical analysis and nomenclature are not currently entirely standardized, in contrast for example, to forensic DNA identification, commercial Y-DNA companies have their own unpublished proprietary reference databases and methodologies. It is not unusual for the outcomes of genetic ancestry tests to vary across companies and research organizations.

The naming of genetic markers (SNPs and STRs) are sometimes different between companies. This observation was noted over 10 years ago by the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG), a leading professional scientific membership organization for human genetics and genomics researchers in the world as well as genetic scientists about the need for standardizing tests and genetic marker nomenclature [14].

Haplotree are also different between organizations and databases. In the 1980s and 1990s, individual academic research groups each had their own nomenclature for naming Y-DNA haplogroups. In 2002, the Y-Chromosome Consortium (YCC) published a proposal to standardize the naming of all Y-Chromosome haplogroups. This effort was based on comprehensive retesting of DNA samples (YCC 2002). [15]

As of the writing of this story there are four major Y-DNA haplogroup trees managed by various groups. The most widely used versions are Family Tree DNA, YFULL, the BigTree, and ISOGG. Each of the companies or organizations have different representations of the tree. They also do not uniformly use the same branches or SNP names. Some of the reasons for the differences between the various haplogroup trees are:

- Different databases: the databases of the tested men differ between companies and groups. The different databases reflect the SNPs and order of those SNPs that have been found through their analysis of that database. The different companies and analysis groups use different sources for there SNPs: their own testers (YFull does not test), academic databases, historical sources archeological site analysis.

- Synomyn SNPs: Different companies may select different synonyms for the same SNP even though the mutation may appear in same place on each of their Y-DNA haplotrees it may not have the same name. Oftentimes different labs or analysis companies will discover the same SNP and provide independent names for the SNP. Different companies may select different SNPs from the same equivalent block of SNPs that are part of a branch to represent a particular branch of the D-DNA haplotree.

- Equivalent SNPS: Each of these haplogroup trees are developed by analyzing a group of tested men and developing a SNP mutation history that shows how these ancestors branched from each other. Many branches have died out before present day men were tested. As more men are tested, mutations will be found that are new but related to specific older branches. If a number of men who are tested by a given company and found to have new mutations they may form a new branch. However, the results from this one company may be viewed by other companies who manage other haplotrees as ‘private’ SNPs and therefore will not be viewed as a new branch.

- Selection Criteria: The companies also have different criteria for testing quality, region of the chromosome, for which SNPs belong on their haplogroup tree. SNPs which may be selected by one company may not be acceptable to another.

An Intuitive View of the Griff(is)(es)(ith) Genetic Paternal Line in Time

Before I get too deep into an attempt to explain the ‘what’s’ of genetic ancestry and the ‘results‘ of the testing, I thought a bit of visualization of the ‘deep ancestry’ results would be intuitive and perhaps more appealing and entertaining. Hopefully this will keep your attention.

The following on-line interactive program called “STR Tracker” [16], developed by Rob Spencer, traces individual genetic lines of ancestry. Based on the terminal point on the haplotree, provided by the user, it provides an animated route over time from where modern day humans evolved, starting with the haploid group A – “Adam” Haplogroup, to an end point on the map.

“(T)he emphasis here is on getting the most out of personal Y DNA data by applying original algorithms to create informative graphics. If you’re like me, you find large tables and spreadsheets more exhausting than inspiring. DNA is an intrinsically digital medium for information, and so its patterns are ideally suited for computer analysis and visualization.” [17]

STR Tracker shows a walking man icon traversing the path of either your paternal or maternal ancestors. Selected major events and cultures appear as the walking man traverses the continent. I have entered my ‘terminal STR’, BY211678 (which is genetically akin to a small twig on an ancestral tree composed of branches, limbs, twigs and leaves). that was confirmed by my Y-DNA test and created a video of the path that illustrates the paternal migration time line for the Griff(is)(es)(ith) family. While the accuracy or reliability of the statistical results of such an illustration are fraught with possible sources of error, Spencer does an amazing job at bringing historical and DNA data to life. [18]

The historical path generated from this program is probably not the actual path of he ancestors of the Griff(is)(es)(ith) patrilineal line but captures the time period and general location of each successive genetic mutation that occurred along the paternal lineage. A brief discussion on possible paths of migration are provided later in the story.

For a larger rendition of the video click here (recommended) and then click on the video arrow for the animation to start.

Video: Historical Path of the Griff(is)(es)(ith) Paternal Line

We will come back to the walking man’s journey from Africa to the English Isle later in the story. Suffice to say, the video is a concise intuitive summation of the ‘deep ancestry’ of the Griff(is)(es)(ith) paternal line.

The Emergence of Consumer-Based Genetic Ancestry Testing

A review of the literature on DNA Genealogy reflects that the last 20 years has experienced rapid technological advances, the reduction of costs associated with testing, and an ever changing market of consumer products for genealogical research. As I said, it is the ‘wild wild west’ in terms of the growth of genetic ancestry testing. Similarly, one finds rapid advances in the field of paleogenetics or paleogenomics that are associated with deep ancestry.

Genealogists grew interested in genetic research at the turn of the millennium when genetic testing became commercially possible to analyze bits of information from the Y chromosome. Because the Y chromosome is passed from father to son with little mutation and because surnames historically were passed down the same way, this confluence became worthy of exploration for commercial applications for ancestry research.

For an excellent overview of Y-DNA concepts and how it fits into traditional ancestry research, J. David Vance provides a cogent book on the subject as well as a three part series of videos: [19]

In the late nineties, Bryan Sykes, an Oxford geneticist, persuaded forty-eight men who shared his surname to take Y-DNA tests. [20] The name was thought to have arisen separately among unrelated families. But the genetics suggested that the men descended from a single ancestral line. “If this pattern is reproduced with other surnames, it may have important forensic and genealogical applications”, Sykes concluded. Theoretically, researchers could use Y-DNA to establish the pedigree of a man with an unknown identity. Sykes made a similar case for mt-DNA (mitochondrial DNA) , which is passed down on the maternal line, in a book titled “The Seven Daughters of Eve.” The book described the seven major mitochondrial DNA haplogroups of European ancestors.

The first company to provide direct-to-consumer genealogical DNA tests was the now defunct GeneTree. In 2001, GeneTree sold its assets to Salt Lake City-based Sorenson Molecular Genealogy Foundation (SMGF) which originated in 1999. While in operation, SMGF provided free Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA tests to thousands. Later, GeneTree returned to genetic testing for genealogy in conjunction with the Sorenson parent company and eventually was part of the assets acquired in the Ancestry.com buyout of SMGF in 2012. [21]

In May 2000, Family Tree DNA in Houston, Texas, began offering the first genetic genealogy tests to the public. This provided the commercial basis to test and amass data to validate the theory of tracing genealogy through the Y chromosome outside of an academic study. [22] Additionally, Sykes’ concept of a surname study, which by this time had been adopted by several other academic researchers outside of Oxford University, was expanded into online surname projects and the effort helped spread knowledge gained through testing to interested genealogists worldwide.

Bryan Sykes launched Oxford Ancestors, in anticipation of the expected demand for mitochondrial DNA tests from the publication of Sykes’ book The Seven Daughters of Eve, which appeared in the spring of 2001. In the wake of the book’s success, and with the growing availability and affordability of genealogical DNA testing, genetic genealogy as a field began growing rapidly.

By 2003, the field of DNA testing of surnames was declared to have officially “arrived” and by the mid 2000’s the number of firms offering Y-DNA tests, and the number of consumers ordering them, had risen dramatically. [23]

In 2007, 23andMe was the first company to offer a saliva-based direct-to-consumer genetic testing. [24] It was also the first to implement the use of autosomal DNA for ancestry testing, which other major companies now use (e.g., Ancestry, Family Tree DNA, and MyHeritage).

By 2012, there were 12 companies that provided various types of Y-DNA tests. [25]

In 2013 Family Tree DNA released what they called the the advanced Big Y test and since then, they have analyzed 32,000 Y chromosomes. This process has resulted in the identification of hundreds of thousands of unique Y chromosome mutations. The human Y chromosome contains about 56 million positions or base pairs. Of them, roughly 23 million base pairs (40%) are useful for phylogenetic analysis. In these 23 million positions, the company has detected over 500,000 unique mutations in the total 32,000 individuals who have completed the Big Y test. The company maintains one of the largest Y-DNA data bases and maintains one of the most up to date phylogenic Y-DNA trees. [26]

MyHeritage launched its genetic testing service in 2016, allowing users to use cheek swabs to collect samples. In 2019, the company provided new analysis tools called autoclusters (grouping all matches visually into clusters) [27] and family tree theories that suggested possible relations between DNA matches by combining several Myheritage trees as well as the Geni global family tree. [28]

Living DNA, founded in 2015, started providing a genetic testing service. Living DNA used SNP chips to provide reports on autosomal ancestry, Y-DNA, and mtDNA ancestry. The company provides detailed reports on ancestry as well as detailed Y chromosome and mtDNA reports. [29]

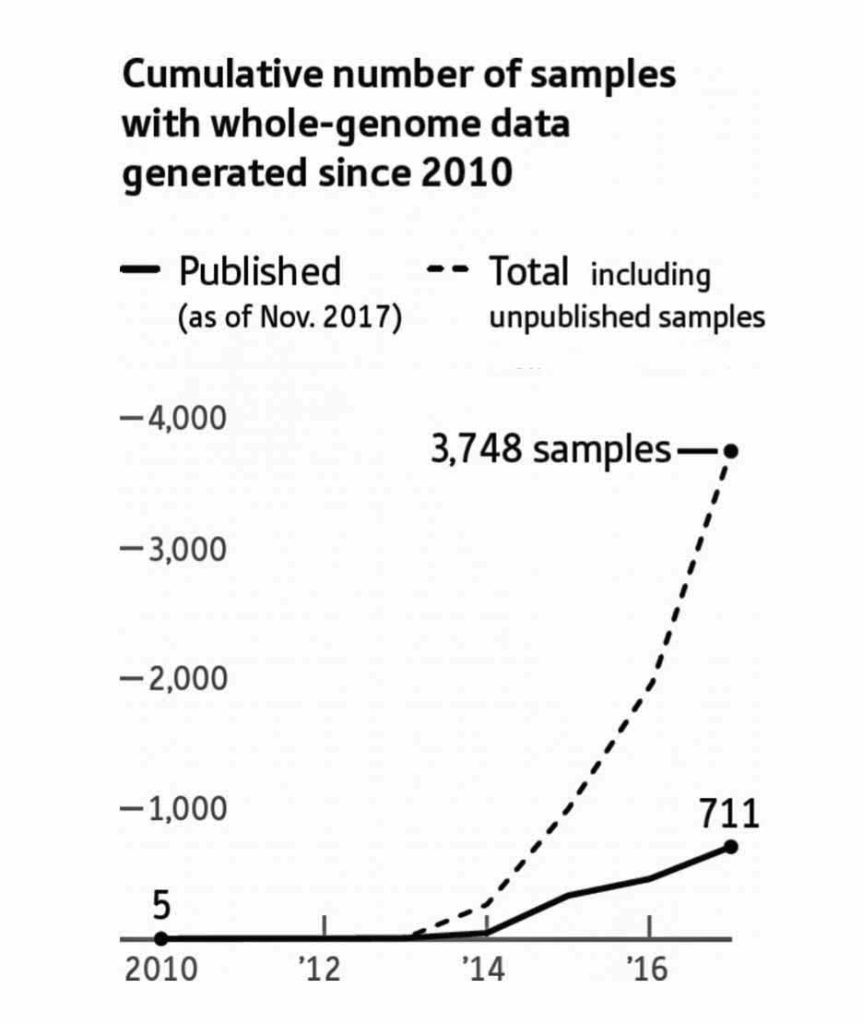

Illustration 3: DNA Database Growth 2013 – 2022

In 2019 it was estimated that large genealogical testing companies had about 26 million DNA profiles. In 2022, estimates based on the same companies were roughly 40.7 million. Many transferred their test results for free to multiple testing sites, and also to genealogical services such as Geni.com and GEDmatch. GEDmatch said in 2018 that about half of their one million profiles were from the USA. [30]

In 2019, FamilyTreeDNA announced an enhanced chemistry formula for Big Y. This allowed the company to detect more mutations. The human Y chromosome contains about 56 million positions or base pairs. Of them, roughly 23 million base pairs (40%) are useful for phylogenetic analysis. In these 23 million positions, the company detected over 500,000 unique mutations in the total 32,000 Big Y testers. In May 2019, FamilyTreeDNA documented over 20,000 branches in the Y haplogroup tree. The branches are defined by over 150,000 unique mutations. Compared to other organization and company haplogroup trees, this made the company’s haplotree the largest and most detailed phylogenetic tree. [31]

FamilyTreeDNA is the clear forerunner in terms of having the largest Y-DNA database. As of August 28, 2022, the FamilyTreeDNA database contained a total of 1,199,769 records. This number includes transfers from the Genographic Project and resellers in Europe and the Middle East. The company had 809,908 Y-DNA records and 226,790 mtFull (mitochondria) DNA records . [32]

Relative to the size of autosomal DNA databases that showcase “ethnic backgrounds’ and genetic matches of ‘foruth and fifth cousins’, Y-DNA databases are relatively small. Consequently, finding genealogical matches via Y-DNA can be a challenge. The nature of the consumer audience for Y-DNA tests is also perhaps unique and specialized. Individuals obtaining Y-DNA tests have usually completed autosomal tests and are looking for more advance and refined results.

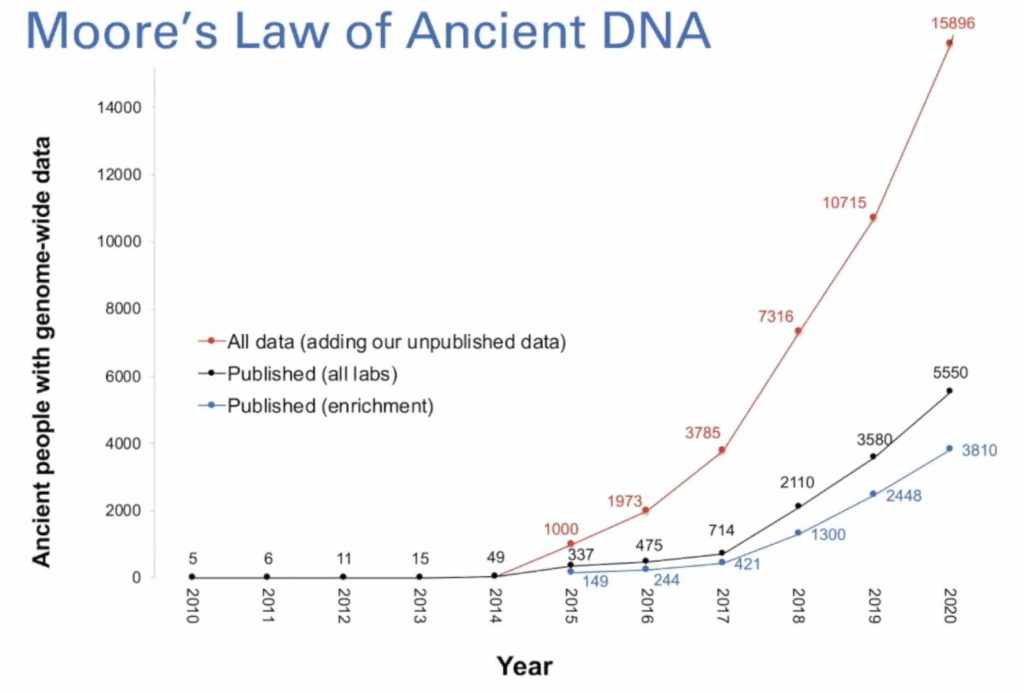

While rapid technical and market based advances were happening with the rise of the consumer based DNA testing, the scientific breakthroughs associated with the ability to extract DNA from ancient bones, “the ancient DNA revolution’, was also happening. During the past decade technological advances have made it cost effective and efficiently possible to sequence the entire genome of humans who lived tens of millions of years ago. The result has been an explosion of new information that has fueled in an emerging academic field of paleo-genetics or paleo-genomics that is transforming archaeology and the mapping of deep ancestry at a macroscopic level. In 2018 alone, the genomes of more than a thousand prehistoric humans were determined, mostly from bones dug up years ago and preserved in museums and archaeological labs. [33]

The analysis of ancient genomes provides the equivalent of the personal DNA testing kits available today, but for people who died long before humans invented writing, the wheel, or pottery. The genetic information is startlingly complete: everything from hair and eye color to the inability to digest milk can be determined from a thousandth of an ounce of bone or tooth. Similar to personal DNA tests, the results reveal clues to the identities and origins of ancient humans’ ancestors—and thus to ancient migrations.

As the chart to the left illustrates, ancient DNA labs are now producing data on ancient human artifacts so quickly that the time lag between data production and publication of the results is longer than the time it takes to double the data production in the field. David Reich published this chart in 2018. In the matter of two years, Reich updated the chart (below) [34] to reflect the dramatic increase in the number of completed whole genome sequencing of ancient remains. He referred to the dramatic increase in sampling of ancient genome data as “Moore’s Law of Ancient DNA”. [35]

Illustration 5: Growth of Genome Sequencing of Ancient Remains

“Over the past few years, David (Reich) and a tiny handful of other scientists have reordered our understanding of humanity’s pre-history. Open questions pondered by generations of archaeologists have been suddenly and definitively answered. … It’s hard to overstate the significance of this work, and the speed with which it’s unfolding. So rapidly, that even electronic scientific journals can’t keep up. It’s prompting one of the biggest shifts ever in our understanding of ourselves as a species. Yet most people are hardly aware of it. “

Robert Reid, After On Podcasts, July 31, 2018, Episode 34: David Reich – Ancient DNA https://after-on.com/episodes-31-60/034

The technological and statistical breakthroughs associated with paleo-genomics has been reflected in the recent award of the Nobel Prize in Medicine to Svante Pääbo.

“Through his pioneering research, Svante Pääbo accomplished something seemingly impossible: sequencing the genome of the Neanderthal, an extinct relative of present-day humans. He also made the sensational discovery of a previously unknown hominin, Denisova.

“Through his groundbreaking research, Svante Pääbo established an entirely new scientific discipline, paleogenomics. Following the initial discoveries, his group has completed analyses of several additional genome sequences from extinct hominins. Pääbo’s discoveries have established a unique resource, which is utilized extensively by the scientific community to better understand human evolution and migration. New powerful methods for sequence analysis indicate that archaic hominins may also have mixed with Homo sapiens in Africa. However, no genomes from extinct hominins in Africa have yet been sequenced due to accelerated degradation of archaic DNA in tropical climates.” [36]

Notes

The story was updated on Oct 3, 2022, based on the news of the Nobel Award in Medicine to Svante Pääbo.

Feature Image of the story is a rendition of the double helix DNA, source: background image in Big Y-700: The Forefront Of Y Chromosome Testing, Blog Update, 7 Jun 2019, Family Tree DNA, https://blog.familytreedna.com/human-y-chromosome-testing-milestones/

[1] One quote attributes the surname change to the turbulence of the Revolutionary War and the effects of the name being transcribed in various formats.

“In the tumultuous days preceding and during the Revolution, many records and many buildings were destroyed. At best the records are sketchy and inconsistent, and, obviously the spelling by clerks laboriously writing by hand as casual and irregular; for instance, in one book we find the name spelled GRIFFIS on one page and then spelled GRIFFITHS on another page.”

Source: Griffith & Peets, Griffith Family History in Wales 1485–1635 in America from 1635 Giving Descendants of James Griffis (Griffith) b. 1758 in Huntington, Long Island, New York, compiled by Capitola Griffis Welch, 1972 . Page 8

Another quote attributes the name change to William Griffis’ purported lisp and inability to pronounce Griffith and his resultant behavioral actions to hide his impediment by spelling the surname as ‘Griffis’.

“According to the family legend, as told by Albert Buffet Griffith… , William Griffith had difficulty pronouncing ‘th’, and in a name or worth ‘th’ sounded like an ‘s’. As this speech impediment was an embarrassment to him, he allowed the clerk to record his name as Griffis rather than confessing the spelling was Griffith which would have called the clerk’s attention to the impediment.”

Source: Griffith & Peets, Griffith Family History in Wales 1485–1635 in America from 1635 Giving Descendants of James Griffis (Griffith) b. 1758 in Huntington, Long Island, New York, compiled by Capitola Griffis Welch, 1972 . Page 9

A third quote from a grandson of William Griffis states that he was told the family came from Wales and it was not known why the name changed from Griffith.

“My Great Grandfather, on my father’s side came from Wales & settled in Huntington, Long Island. They spelled the name Griffiths. My Grandfather, who died at my Father’s house could never give me a reason why he changed it to Griffis.” – William Case Griffis

Source: Information that was added by William Case Griffis to his father’s personal journal, William Griffis, in a family manuscript written compiled by Mary Martha Ryan Jones and Capitola Griffis Welch, compiled by, Griffis Sr of Huntington Long Island and Fredericksburg, Canada 1763-1847 and William Griffis Jr, (Reverend William Griffis) 1797-1878 and his descendants. A self published genealogical manuscript, 1969. Page 103 PDF copy of the manuscript can be found here.

Family folklore indicates that Albert Buffet Griffith told his daughter-in-law, Lillian that

“his great, great grandfather’s name was Samuel”.

Source: Mildred Griffith Peets, Griffith Family History in Wales 1485–1635 in America from 1635 Giving Descendants of James Griffis (Griffith) b. 1758 in Huntington, Long Island, New York, compiled by Capitola Griffis Welch, 1972 , page 8 .PDF copy of the manuscript can be found here.

If Albert Griffith’s recollections are true, then William’s father was perhaps Samuel Griffith, from Wales.

[2] Testing: The Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How of Y-DNA Testing, Legacy Tree Genealogists, Page accessed 21 Jun 2022

[3] Debbie Kennett, What is Y-DNA?, Who Do you Think You Are?, May 17, 2022

[4] Things that DNA tests cannot do:

Y-DNA tests can not tell you if your paternal line was from a particular culture or tribe, or some other group in the past. If based on the results of your DNA test you connect with another person in a Y-DNA project who had documentation of this knowledge, then indirectly the DNA test can provide leads to document this specific fact. One does not learn about this information through Y-DNA. Certain genetic configurations of designated markers of Y-DNA have been found in human remains in areas inhabited by specific ancient cultures. The results of various studies indicate that specific Y-DNA spread historically in general geographic areas at certain, general time periods. The mapping of ancient DNA distributions are more precise in the last ten years but as to whether one’s ancestors spent time among a particular culture is completely unknown. Current knowledge reflects that we do not know where all the Y-DNA mutations started. We have an idea of what cultures certain Y-DNA may have traveled with but that does not mean anyone’s specific ancestors traveled with them and did not travel with another culture.

DNA tests per se can not break brick walls encountered in ancestry research. DNA tests can help to break through brick wall but only with help. Typically the test results will facilitate finding other individuals with knowledge or documentation that helps you break through your own brick wall because they knew something farther back that you did, or you put your two sets of knowledge together and you find discoveries based on common ancestors.

Y-DNA tests can not identify specific ancestors or where they lived. The original, geographical locations and names of ancestors can be determined through traditional historical sources based on genetic lines that may be discovered.

Y-DNA tests can not identify the exact generation of a common ancestor with supporting data. Age estimation of a common ancestor has a large margin of error and is a topic of contention among DNA companies and scientists.

[5] The best Y-DNA tests are from FamilyTreeDNA (FTDNA). They are the only company of ‘the big five’ to offer dedicated Y testing and the only company that provides matching capabilities based on other testers who may post gnealological trees with supporting information. FamilyTreeDNA offers three levels of Y-DNA STR testing: Y-37, Y-111, and Big Y-700 (Big Y also tests SNPs). The numbers refer to how many DNA markers the test examines. The more markers, the more useful the results will be. They also have the largest population of Y-DNA testers. LivingDNA tests the most number of Y SNPs among the big five autosomal companies. 23andMe will test the Y-chromosome as part of their autosomal test, but only enough to tell you your haplogroup. Their test does not allow you to compare your results against other users to find distant paternal ancestors. Ancestry.com unfortunately does not offer Y-DNA testing at this time. But they do actually “test” the Y chromosome and supply the results if you look at your raw data. The amount of SNPs tested are roughly half of what 23andMe reports and about 20 times less than LivingDNA.

Additional references:

Genealogical DNA Test, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 11 August 2022, page accessed 12 Aug 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genealogical_DNA_test

A Y-STR testing chart provides comparative information on the Y-STR Y chromosome DNA tests offered by 3 major DNA testing companies. Y-STR tests are used for genetic genealogy within a genealogical timeframe and are generally co-ordinated through surname DNA projects. See: Y-DNA STR testing comparison chart, International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki, This page was last edited on 11 July 2022, https://isogg.org/wiki/Y-DNA_STR_testing_comparison_chart

A Y-DNA SNP testing chart in this article provides comparative information on the Y chromosome SNP tests offered by 6 major DNA testing companies. For information on the Y-STR tests used for genealogical DNA matching purposes within surname DNA projects see the Y-DNA STR testing chart. See: Y-DNA SNP testing chart, Y-DNA SNP testing chart, Y-DNA STR testing comparison chart, International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki, This page was last edited on 16 February 2022, page accessed 20 Feb 2022, https://isogg.org/wiki/Y-DNA_SNP_testing_chart

Marc McDermott, Best Y-DNA Test: Everything you need to know about Y-DNA testing for genealogy, 17 Nov 2021, smarterhobby.com, https://www.smarterhobby.com/genealogy/best-y-dna-test/

Coakley L. Which DNA testing company should I use? Genie1 blog (a review from the perspective of people living in Australia and New Zealand)

Griffith S. Buyer beware links. Genealogy Junkie, 14 May, 2014.

Griffith S. Notes for UK (& Ex-US) residents re DNA testing companies. Genealogy Junkie, 16 January 2014.

MacArthur D. Ready to test your DNA: how to choose a genetic testing company. PRI’s The World, 22 March 2012.

Aulicino E. Which DNA testing company fits your needs? Genealem blog, 23 May 2009.

Wagner JK, Cooper JD, Sterling R, and Royal CD. Tilting at windmills no longer: a data-driven discussion of DTC DNA ancestry tests. Genetics in Medicine 2012:14(6):586–593. The article provides a bit outdated snapshot of the direct-to-consumer DNA ancestry testing industry in April 2010 based on a survey of company websites.

[6] Diahan Southard, What’s the Big Y-700 Test? Should I Choose a Y-DNA Test?, Family Tree Magazine, Jan / Feb/ 2018, https://familytreemagazine.com/dna/big-y-700/

In a nutshell, the following blog article provides an overview of the business model that Family DNA employs for customers researching the genetic path of the Y chromosome and providing possible leads to family members. Working with Y DNA – Your Dad’s Story, DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy, 5 Jun 2017, Page accessed 26 Jan 2021

Y-chromosome DNA (Y-DNA),FamilyTreeDNA Help Center, Page accessed 14 Aug 2022, https://help.familytreedna.com/hc/en-us/articles/4414463886351-Y-chromosome-DNA-Y-DNA-#y-dna-snps-0-0

2020 Review Of Big Y, FamilyTreeDNA Blog, 1 Feb 2021, https://blog.familytreedna.com/2020-review-of-big-y/

Big Y-700 Tests: Any advice for advanced analysis of results?, WikiTree G2G, 19 Apr 2021, https://www.wikitree.com/g2g/1223388/big-y-700-tests-any-advice-for-advanced-analysis-of-results

Big Y, FamilyTreeDNA Blog, not dated, https://blog.familytreedna.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/big-y.pdf

2019 Review Of Big Y, FamilyTree DNA Blog, 27 Dec 2019, https://blog.familytreedna.com/2019-review-of-big-y/

Family Tree DNA’s Y-500 is Free for Big Y Customers, FamilyTreeDNA Blog, 23 Apr 2018, https://dna-explained.com/2018/04/23/family-tree-dnas-y-500-is-free-for-big-y-customers/

Davis, C., Sager, M., Runfeldt, G., Greenspan, E., Bormans, A., Greenspan, B., & Bormans, C., Big Y-700 [White paper] 2019: https://blog.familytreedna.com/big-y-700-white-paper/

Biology Dictionary: https://biologydictionary.net/dna-sequencing/

FamilyTreeDNA Public Y-DNA Haplotree: https://www.familytreedna.com/public/y-dna- haplotree

McDonald, Dr. Iain. Recent human genetic anthropology: http://www.jb.man.ac.uk/~mcdonald/genetics.html

[7] A haplotype is a group of alleles in an organism (i.e. a person) that are inherited together from a single parent, and a haplogroup is a group of similar haplotypes (i.e. a group of people) that share a common ancestor with a single-nucleotide polymorphism mutation.

For Y-DNA, a haplogroup may be shown in the long-form nomenclature established by the Y Chromosome Consortium, or it may be expressed in a short-form using a deepest-known single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP).

see for example: Haplogroup, Wikipedia, page was last edited on 12 August 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup

Haplogroup, International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki, This page was last edited on 27 June 2022, https://isogg.org/wiki/Haplogroup

[8] Page 13-14 of a readable transcript of the narration in a YouTube at https://drive.google.com/open?id=1CdU…, the video is by J. David Vance, DNA Concepts for Genealogy: Y-DNA Testing Part 1, 10 Oct 2019, https://youtu.be/RqSN1A44lYU

[9] Chris Gunter, Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPS), National Human Genome Research Institute, 12 Sep 2022, https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Single-Nucleotide-Polymorphisms

What are single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)?, National Library of Medicine, accessed 10 Jul 2022, https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/genomicresearch/snp/

Single-nucleotide polymorphism, Wikipedia, page accessed 4 Apr 0222, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Single-nucleotide_polymorphism

What are SNP’s, Genetics Generation, Page accessed 15 Jun 2022, https://knowgenetics.org/snps/

Sampson JN, Kidd KK, Kidd JR, Zhao H. Selecting SNPs to identify ancestry. Ann Hum Genet. 2011 Jul;75(4):539-53. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3141729/

[10] National Institute of Justice, “What Is STR Analysis?,” March 2, 2011, nij.ojp.gov:

https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/what-str-analysis

STR analysis, Wikipedia, page was last edited on 13 June 2022, page accessed, 4 Sep 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/STR_analysis

Short Tandem Repeat, International Society of Genetic Genealology Wiki, page was last edited on 31 January 2017,page accessed 10 Oct 2022, https://isogg.org/wiki/Short_tandem_repeat

[10] 2020 Review Of Big Y, FamilyTreeDNA Blog, 1 Feb 2021, https://blog.familytreedna.com/2020-review-of-big-y/

Big Y-700 Tests: Any advice for advanced analysis of results?, WikiTree G2G, 19 Apr 2021, https://www.wikitree.com/g2g/1223388/big-y-700-tests-any-advice-for-advanced-analysis-of-results

Big Y, FamilyTreeDNA Blog, not dated, https://blog.familytreedna.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/big-y.pdf

[11] In human genetics, the haplogroups most commonly studied are Y-chromosome (Y-DNA) haplogroups and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups, each of which can be used to define genetic populations. Y-DNA is passed solely along the patrilineal line, from father to son, while mtDNA is passed down the matrilineal line, from mother to offspring of both sexes. The haplogroups are based on the identification of a unique series of genetic values for specific genetic markers. These unique sequences in the Y-DNA and mtDNA change only by chance mutation in various generations. When a mutation occurs, the haplogroup branches off into another branch that can still be identified through its past branches.

[12] “The percentage of haplogroup G among available samples from Wales is overwhelmingly G-P303. Such a high percentage is not found in nearby England, Scotland or Ireland.”

source: Haplogroup G-P303, Wikipedia, Page updated 1 Feb 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_G-P303

Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup, Wikipedia, page was last edited on 24 August 2022, page accessed 30 Aug 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_Y-chromosome_DNA_haplogroup#cite_note-isogg2015-10

Specifically, the descendants are part of the Y-chromosome subclade Haplogroup G-P303 (G2a2b2a, formerly G2a3b1). It is a branch of haplogroup G (Y-DNA) (M201). In descending order, G-P303 is additionally a branch of G2 (P287), G2a (P15), G2a2, G2a2b, G2a2b2, and finally G2a2b2a. This haplogroup represents the majority of haplogroup G men in most areas of Europe west of Russia and the Black Sea.

source: Haplogroup G-P303, Wikipedia, Page updated 1 Feb 2022, page accessed 28 Jun 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_G-P303

“G2a3b1a This is the dominant G group in Europe (perhaps 80% of G samples) and may reach up to about 7% of all men in a country but averages about 3%. A high percentage of G2a3b1a samples form three major subgroups, DYS388=13 (L497+), YCA=19,20 type of L13+ and DYS568=9. One G2a31a subgroup (U1+) is also confirmed in some frequency outside Europe only in the Caucasus region, particularly in the northwest. North of the European borders of the once Roman Empire, the prevalence of these three G2a3b1a subgroups (and G in general) drops considerably, and the three subgroups are found in noticeable amounts in almost all regions of the once Roman Empire in Europe except among the Basques of Spain. An Ashkenazi Jewish cluster from northeastern Europe comprises about half of the DYS568=9 subgroup, and this Jewish subgroup represents an exception to usual European boundaries mentioned. The connection of these three G2a3b1a subgroups to Etruscans, Alans and Sarmatians and other groups who migrated to Europe is widely debated. (data from Adams and abt 2000 G2a3b1a samples in G project)”

source: Y-DNA Haplogroup G and its Subcldes – 2018, ISOGG,8 March 2018 https://isogg.org/tree/ISOGG_HapgrpG.html

[13] Sheldon Krimsky, Understanding DNA Ancestry, Cambridge: Cambridge University , 2022, Page 126

[14] The American Society of Human Genetics Ancestry Testing Statement, November 13, 2008 https://www.ashg.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/11/Statement-20081311-ASHGAncestryTesting.pdf

J.M. Butler, Nomenclature Issues and the Y-Chromosome Genetic Genealogy Conference, Houston, TX, October 20, 2007, https://strbase.nist.gov/pub_pres/GeneticGenealogy_Y-STR_nomenclature.pdf

Michael L. Hébert, -DNA Testing Company STR Marker Comparison Chart, last updated 8 Jan 2012, http://www.gendna.net/ydnacomp.htm

[15] The Y-Chromosome Consortium for many years left individual groups to maintain this standard. In 2008, they again published a comprehensive review of tree changes and retested samples. With this work, they strengthened their recommendation to move to a nomenclature system they referred to as shorthand (Karafet 2008). The Y Chromosome Consortium (2002) defined a set of rules to label the different lineages within the tree of binary haplogroups. Capital letters (from A to R) were used to identify 18 major clades. Two complementary nomenclature systems were proposed. The first system used selected aspects of set theory to define hierarchical subclades within each major haplogroup using an alphanumeric system (e.g., E1, E1a, E1a1, etc.). A shorter alternative mutation-based system named haplogroups by the terminal mutation that defined them (e.g., E-M81).

Karafet, T. M.; Mendez, F. L.; Meilerman, M. B.; Underhill, P. A.; Zegura, S. L.; Hammer, M. F., Y Chromosome Consortium, A Nomenclature System for the Tree of Human Y-Chromosomal Binary Haplogroups, Genome Research, (18) 5, 2008

Conversion table for Y chromosome haplogroups, This page was last edited on 29 January 2022, page was accessed on 18 Jul 2022.

YDNA-Warehouse: The Y-DNA Warehouse is a free community initiative to allow collection sequencing results of the human genome. Members can upload and combine their sequencing results from labs such as 23andMe, AncestryDNA, FamilyTreeDNA, Full Genomes Corporation, YSEQ or one of the many newer WGS providers. A suite of tools is in development to help allow members learn more about what was found in these tests individually through a match messaging system or enrolling in anonymized studies. The primary goal is to construct a public YSNP Tree that is explicitly reusable under the Creative Commons license. https://ydna-warehouse.org

yFull Y-DNA Haplotree: https://www.yfull.com/home/

[16] Rob Spencer, STR Tracker, http://scaledinnovation.com/gg/snpTracker.html

[17] Rob Spencer, Tracking Back: a website for genetic genealogy tools, experimentation, and discussion, Page accessed 3 Feb 2022, http://scaledinnovation.com/gg/gg.html

[18] See Spencer’s comments on updates to the tracker: Robb Spencer, Highway Maintenance, Tracking Back, a website for genetic genealogy tools, experimentation, and discussion, Page accessed 1 Aug 2022,

As one individual indicated in his assessment of Spencer’s SNP Tracker tool:

“Rob Spencer does his best with this tool, but ultimately this is a very tricky subject to get right. Consequently, you should take anything you see on the SNP tracker with a very large pinch of salt. The results are meant to be instructive, but not accurate.”

source: Comment about the SNP Tracker at R1b-U106@groups.io This is a forum for discussion of Haplogroup R1b-U106 and related genetic genealogy topics.

A lot of the problems come from the fact DNA testing is very biased towards testing people from the British Isles, by factors of up to 12:1 or more compared to other European countries. This is changing as more individuals are completing Y-DNA tests from other regions of the world. This means that the tracker can not work with a homogeneous data set. Rob has corrected the British / European Continental bias as best he as he can, but as he professes, he does not correct for variations within Europe, and he can not remove the basic fundamental problem that he has to use small numbers of testers from poorly sampled regions to fill in a lot of the gaps. Consequently, the origins he marks for individual haplogroups are usually too far west. He indicates that he has pinned some of them manually to increase historical accuracy. Many of the haplogroups he claims have originated in the British Isles are simply there because they show up as a handful of cases in Britain or Ireland and we have no evidence of their existence elsewhere due to this bias. Unless a haplogroup has a very unique geographical distribution or is wholly found in continental Europe (a lot of haplogroups do fit these criteria), it takes several hundred testers to accurately place its origin at the level of individual countries.

As stated in a related post on this forum, the ages in the SNP tracker come from YFull.org.

“YFull only contains a small subset of the overall data that’s available to Family Tree DNA. This means their underlying set of tests is small, and their uncertainties are correspondingly large. Potentially, the most serious consequence of this – and I don’t know how Rob deals with this – is that haplogroups that are on YFull’s tree don’t always match up with those on Family Tree DNA’s tree, even when they have the same name. This is because many of those haplogroups have been split by FTDNA. I also don’t know exactly what Rob does for haplogroups that don’t have ages in YFull – I presume he just counts SNPs down the tree, but he’ll have to do this without knowledge of whether those SNPs come from BigY-500 or -700 tests, which makes a big difference.” PDF of comment:

See: Original Threaded post: SNP Tracker 19 Jan 2021, https://groups.io/g/R1b-U106

YFull’s uncertainties also remain large because they only take SNP data into account. If you take STR data and any other historical information you can get your hands on (paper trails, surnames, ancient DNA), then you can create much more accurate results… at least, in theory.

[19] J. David Vance, DNA Concepts for Genealogy: Y-DNA Testing Part 1, 10 Oct 2019, https://youtu.be/RqSN1A44lYU

Part 1 of a 3-part introduction series to Y-DNA for genealogists. This first video focuses on “Why?” use Y-DNA for genealogy – what benefits does it offer and why should genealogists consider using Y-DNA as part of their research?

J. David Vance, DNA Concepts for Genealogy: Y-DNA Testing Part 2, 3 Oct 2019 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mhBYXD7XufI&t=355s

Part 2 of a 3-part introduction series to Y-DNA for genealogists. This second video focuses on “What?” for Y-DNA for genealogy – what are STRs and SNPs, what is genetic distance, what is the haplotree, and other related questions

J. David Vance, DNA Concepts for Genealogy: Y-DNA Testing Part 3, 10 Oct 2019 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=03hRXVg9i1k&t=4s

Part 3 of a 3-part introduction series to Y-DNA for genealogists. This third video focuses on “How?” for Y-DNA for genealogy – how do I use the information provided by Y-DNA tests to advance my genealogy and/or my lineages?

J David Vance, The Genealogist Guide to Genetic Testing, 2020 https://www.amazon.com/Genealogists-Guide-Testing-Genetic-Genealogy/dp/B085HQXF4Z/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

For other recent guides, see:

Blaine Bettinger, The Family Tree Guide to DNA Testing and Genetic Genealogy, 2nd Edition, Penguin Random House LLC 2016

Diana Elder, NicoleDyers and Robin Wirthlin, Research Like a Pro with DNA: A Genealogist’s guide to Finding and Confirming Ancestors with DNAEvidence, Highland UT: Family Locket Books, 2021

[20] Bryan Sykes and Catherine Irven. Surnames and the Y Chromosome. American Journal of Human Genetics, April 2000, Vol 66, issue 4, pp 1417–1419.

Bryan Sykes, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 3 August 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bryan_Sykes

Oxford Ancestors, International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki, This page was last edited on 11 May 2022, https://isogg.org/wiki/Oxford_Ancestors

Bryan Sykes and Catherine Irven. Surnames and the Y Chromosome. American Journal of Human Genetics, April 2000, Vol 66, issue 4, pp1417–1419.

Bryan Sykes, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 3 August 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bryan_Sykes

Oxford Ancestors, International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki, This page was last edited on 11 May 2022 https://isogg.org/wiki/Oxford_Ancestors

Roberta Estes, Bryan Sykes Finally Meets Eve’s 7 Daughters, DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy 20 Dec 2020, Page accessed 28 Jun 2020, https://dna-explained.com/2020/12/20/bryan-sykes-finally-meets-eves-7-daughters/

The Seven Daughters of Eve, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 20 April 2022, page accessed 7 Jul 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Seven_Daughters_of_Eve

[21] Genealogical DNA test, Wikipedia, Page updated 11 Aug 2022, page accessed 20 Aug 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genealogical_DNA_test

“CMMG alum launches multi-million dollar genetic testing company”(PDF). Alum Notes. Wayne State University School of Medicine. 17 (2): 1. Spring 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

“How Big Is the Genetic Genealogy Market?”. The Genetic Genealogist. 6 November 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2009.

Dobush, Grace (12 July 2012). “Ancestry.com Acquisition Means Changes at GeneTree and SMGF.org”. Family Tree. Retrieved 10 April2019.

“Ancestry.com Launches new AncestryDNA Service: The Next Generation of DNA Science Poised to Enrich Family History Research”(Press release). Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

[22] Belli, Anne (18 January 2005). “Moneymakers: Bennett Greenspan”. Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

“National Genealogical Society Quarterly”. 93 (1–4). National Genealogical Society. 2005: 248. .

Lomax, John Nova (14 April 2005). “Who’s Your Daddy?”. Houston Press. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

Dardashti, Schelly Talalay (30 March 2008). “When oral history meets genetics”. The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

Bradford, Nicole (24 February 2008). “Riding the ‘genetic revolution'”. Houston Business Journal. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

[23] Mark A. Jobbing and Chris Tyler – Smith, The Human Y chromosome: an evolutionary marker comes of age, Nature Reviews Genetics, 4, 598-612, 1 Aug 2003

Blaine Bettinger, How Big is the Genetic Genealogy Market?, The Genetic Genealogist, 6 Nov 2007.

Guido Deboeck, “Genetic Genealogy Becomes Mainstream”, BellaOnline.

DNA genealogy timeline compiled by Georgia Kinney-Bopp (copy of website preserved in the Internet Archive on 26 January 2017)

History of genetic genealogy, International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki, Page last updated 8 Aug 2018, page accessed 22 Jul 2022.

Powell, Kimberly. “Y-DNA Testing for Genealogy.” ThoughtCo, 30 Jul 2021, Updated on March 24, 2019 thoughtco.com/y-dna-testing-for-genealogy-1421847.

Diahan Southard, Big Y DNA Test: When To Use It, Your DNA Guide, https://www.yourdnaguide.com/ydgblog/big-y-ftdna, Page accessed 4 Jan 2022

Marc McDermott, Best DNA Test, 17 Nov 2021, Smarter Hobby, https://www.smarterhobby.com/genealogy/best-y-dna-test

[24] Hamilton, Anita (29 October 2008). “Best Inventions of 2008”. Time. Archived from the original on 2 November 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

[25] Y-DNA Testing Company STR Marker Comparison Chart, page updated 8 Jan 2012, http://www.gendna.net/ydnacomp.htm

[26] Big Y-700: The Forefront of Y Chromosome Testing, 7 June 2019, https://blog.familytreedna.com/human-y-chromosome-testing-milestones/

Caleb Davis, Michael Sager, Göran Runfeldt, Elliott Greenspan, Arjan Bormans, Bennett Greenspan, and Connie Bormans, Big Y-700 White Paper, 22 Mar 2019, https://blog.familytreedna.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/big-y-700-white-paper_compressed.pdf

[27] “Introducing AutoClusters for DNA Matches”. MyHeritage Blog. 28 February 2019.

“MyHeritage’s “Theory of Family Relativity”: An Exciting New Tool!”. DanaLeeds.com. 15 March 2019.

[28] “Is this the most detailed at-home DNA testing kit yet?”. CNN. 22 April 2019

[29] “Comparing the 5 Major DNA Tests: Living DNA – Family Tree”. www.familytreemagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018.

“What I actually learned about my family after trying 5 DNA ancestry tests”. 13 June 2018.

[30] Leah Larkin, The DNA Geek, Spring Growth Is for Databases, Too!, 29 Mar 2022, https://thednageek.com/spring-growth-is-for-databases-too/

Margaret O’Brien, Who Has The Largest DNA Database? (2022), Data Mining DNA, 17 July 2021, Page accessed 21 Aug 2022, https://www.dataminingdna.com/who-has-the-largest-dna-database/

Antonio Regaldo, More than 26b Million People have taken an at home ancestry test, Technology Review, 11 Feb 2019, https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/02/11/103446/more-than-26-million-people-have-taken-an-at-home-ancestry-test/

GlobaL Newswire, World Consumer DNA (Genetic) Testing Market Report 2021, 28 June 2021, https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2021/06/28/2253793/28124/en/World-Consumer-DNA-Genetic-Testing-Market-Report-2021.html

List of DNA testing companies, International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki, Page last updated 11 July 2022 page accessed 22 Jul 2022. https://isogg.org/wiki/List_of_DNA_testing_companies

Phillips AM (2016). ‘Only a click away — DTC genetics for ancestry, health, love…and more: A view of the business and regulatory landscape’. Applied & Translational Genomics 8: 16-22.

Wagner JK, Cooper JD, Sterling R, and Royal CD (2012). Tilting at windmills no longer: a data-driven discussion of DTC DNA ancestry tests. Genetics in Medicine 14(6):586–593. The article provides a snapshot of the direct-to-consumer DNA ancestry testing industry in April 2010 based on a survey of company websites.

[31] Why Choose FamilyTreeDNA, FamilyTreeDNA, page accessed 10 Sep 2022. https://www.familytreedna.com/why-ftdna

International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki, page undated 11 Jul 2022, https://isogg.org/wiki/Y-DNA_STR_testing_comparison_chart#cite_note-5

[32] Big Y-700: The Forefront Of Y Chromosome Testing FamilyTreeDNA Blog, 7 June 2019, https://blog.familytreedna.com/human-y-chromosome-testing-milestones/

[33] David Reich, Who We are and How We got Here, Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past, New York: Vintage Books, 2018

Michael Hofreiter, Johanna L. A. Paijmans, Helen Goodchild, Camilla F. Speller, Axel Barlow, Gloria G. Fortes, Jessica A. Thomas, Arne Ludwig and Matthew J. Collins, The future of ancient DNA: Technical advances and conceptual shifts, Bio Essays 37 (3) Nov 2015. original publication Nov 21 2014, , https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268579140_The_future_of_ancient_DNA_Technical_advances_and_conceptual_shifts

Chinese Academy of Sciences, Researchers chart advances in ancient DNA technology July 21 2022, Phys.org, https://phys.org/news/2022-07-advances-ancient-dna-technology.html

Lorelei Verlhac, DNA and New Technologies: Is Paleogenomics yer Future of Archiealology?, Byacardia, https://www.byarcadia.org/post/dna-and-new-technologies-is-paleogenomics-the-future-of-archaeology

Tsosie KS, Begay RL, Fox K, Garrison NA. Generations of genomes: advances in paleogenomics technology and engagement for Indigenous people of the Americas. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2020 Jun;62:91-96 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7484015/

Evan K Irving-Pease, Rasa Muktupavela, Michael dannermann, Fernando Racimo, Quantitative Human Paleogenetics: What can Ancient DNA Tell us About Complex Trait Evolution?, Frontiers in Genetics, Agustust 2021, Volume 12 Article 703541, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2021.703541/full

[34] David Reich, Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past, 3 Mar 2021, Simon’s Foundation Presidential Lectures, https://www.simonsfoundation.org/event/ancient-dna-and-the-new-science-of-the-human-past/

[35] Moore’s Law refers to Gordon Moore’s perception that the number of transistors on a microchip doubles every two years, though the cost of computers is halved. Moore’s Law states that we can expect the speed and capability of our computers to increase every couple of years, and we will pay less for them. Another tenet of Moore’s Law asserts that this growth is exponential.

Moore’s Law, Wikipedia, page last updated 23 Sep 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moore%27s_law

[36] The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet, Press release: The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2022, 2022-10-03, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2022/press-release/?fbclid=IwAR0nEVI5fMOglx2FR3nZyxMsWttqTOJug8lPYF8cRzd3JLz05QTtR3It1i

Benjamin Meuller, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine Is Awarded to Svante Pääbo, New York Times, 3 Oct 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/03/health/nobel-prize-medicine-physiology-winner.html