It is not uncommon to have siblings in a family who follow similar career paths. There are many stories of brothers or sisters who are doctors, lawyers, or teachers. This is a story of two brothers who were policemen in the late 1800’s and the turn of the century. The role of local community law enforcement in the United States was politicized, provided no training, required the unique ability to balance community demands and encountered all forms of social transgressions.

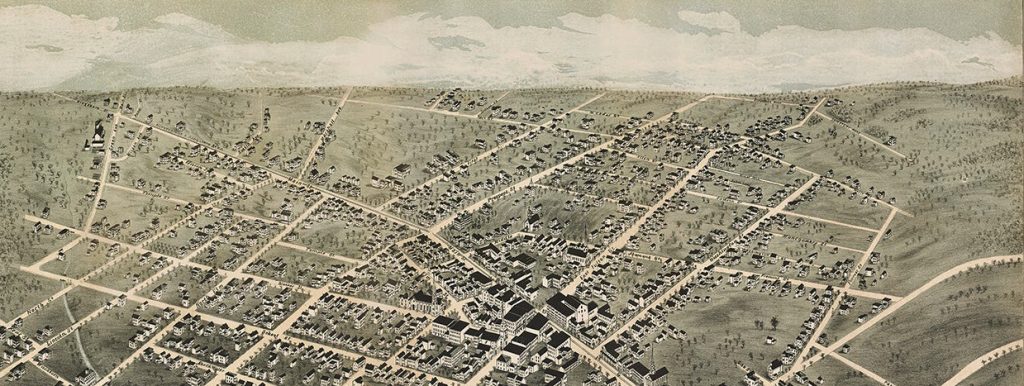

John Frederick Sperber was a police officer for sixteen years between the ages of 30 and 46. For six years of his law enforcement career he was the Chief of Police in Gloversville, New York. His younger brother, Louis P. Speber, was also a policeman for Gloversville between the ages of 31 and 37. They worked together for five years.

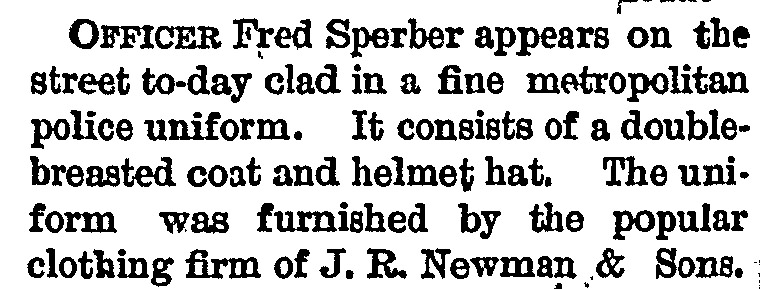

Fred Sperber in Police Uniform

From “A Bird’s Eye View” Daily Column in the Gloversville Daily Leader [1]

Table of Contents / Quick Links to Sections Within This Story

Police in the United States in the late 1800’s

The capabilities and responsibilities of the police in the late 1800’s were largely influenced by local politics and business interests. In Gloversville, there were two 12 hour shifts. In many towns and cities, the police wore designated hats and carried wooden clubs, such as the feature photograph of John Frederick Sperber’s wooden club at the top of this story. It is not known when uniforms were introduced in Gloversville but the photograph above and the news story that memorialized the photo would appear to indicate that the police force in Gloversville had uniforms in the 1880’s. It was not until the late 1800’s when police officers began to routinely carry firearms.

Due to the emergence of industrial towns and cities in the United States from the mid 1800’s till the 1920’s, police departments were established in the United States. This era of policing is referred to as the “Political Era” of policing. [2]

Population growth, the widening inequality brought about by the Industrial Revolution, and the rise in such crimes as prostitution, public drinking, and burglary all contributed to the emergence of urban policing. The United States was no longer a collection of small towns and rural hamlets. Urbanization was occurring at a quick pace and the old informal ‘watch and constable system‘ [3] was no longer adequate to control ‘disorder’.

Anecdotal accounts suggest increasing crime and vice in urban centers led to the emergence of police departments in cities. Mob violence, particularly violence directed at immigrants and African Americans, occurred with some frequency. Public disorder, mostly public drunkenness and sometimes prostitution, was more visible and less easily controlled in growing urban centers than it had been rural villages. More than actual crime, modern police forces in the United States emerged as a response to perceptions of “disorder.”

Social Order and Policing in the Late 1800’s

What constituted social and public order depended largely on who was defining those terms. In the cities of the 19th century America, they were largely defined by the local business interests who, through taxes and political influence, supported the development of bureaucratic policing institutions.

Table one below lists the major arrests by the Gloversville police department by type of arrests for 1899. The table provides an interesting snapshot of the nature and types of arrests that were made by the Gloversville Police Department. It represents arrests between February 1, 1988 and January 30, 1900. It was an 11 month period in which Fred Sperber was the Chief of Police and his brother was a policeman. Perhaps the arrest statistics reflect the “sentiments” of the local community in terms of what constitutes ‘keeping the peace’. [4]

As reflected in the annual report, public intoxication , assaults, disorderly conduct, petty larceny were major areas for arrests. To a lessor extent, keeping a disorderly house (prostitution), non-support of family, and school truancy wereissues of concern the reflected arrests.

Table One: Annual Report of Gloversville Police 1899

| Offense | Arrests | Fines Paid | Total Amnt. Paid $ | Sent to Jail | Sent to Pen | Repri- mand | Dis- charge | Sent out of city |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Intoxication | 93 | 40 | $189 | 5 | 14 | 27 | 4 | 3 |

| Assault 3rd degree a | 35 | 8 | $83 | 2 | 10 | |||

| Assault 2nd degree | 2 b | |||||||

| Assault 1st degree | 1 b | |||||||

| Disorderly Conduct c | 28 | 4 | $35 | 2 | 3 | 6 | ||

| Bicycle Violations | 25 | 19 | $27 | |||||

| Petit Larceny | 15 d | 3 | $40 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Coercion | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Non-support of family | 8 | 3 | $3/wk e | |||||

| Keeping Dis- orderly house f | 3 | 2 | $20 | 1 | ||||

| Defrauding Hotel Keeper | 5 | 2 | $3 | |||||

| Violating School | 4 | 2 | $10 | 2 | ||||

| Liquor Tax Violations g | 4 | 3 | $120 | |||||

| Leaving Horses without weights | 2 | 1 | $1 | 1 | ||||

| Block Streets with electric cars | ||||||||

| Cruelty to animals | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||

| Use of Physician sign | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Selling cider on Sunday | 2 h | 1 | $15 | |||||

| Vagrancy | 3 | 1 i | 2 | |||||

| Tramps | 9 | 1 | 3 | 5 | ||||

| Burglary | 3 j |

a – In nine cases there was no appearance; 2 cases were withdrawn; and two were settled out of court. There were two cases for assault in the second degree and both defendants were held to await the action of the grand jury. There was one assault in the first degree and the offender was held for the grand jury.

b- Held waiting actions of grand jury

c – One sent to house of refuge Hudson; 5 cases no appearance due to no show odf complainent; one suspended case.

d – Two to Rochester Industrial School (for juveniles); 3 cases complainent did not show

e – Three agreed o pay $3 weekly support, 1 suspension 3 withdrawn one settled out of court

f – one settled in court 2 cases there was no appearance of the complainants

g- One held for grand jury; 2 paid fines for reckless driving $20; 1 violation for bankrupt sale ordinance with $100 fine

h – one suspended sentence

I – one sent to women’s refuge house

j – 3 arrests for burglary but all were juveniles.

While public intoxication, disorderly conduct, assault and keeping a disorderly house (prostitution) were constant concerns of various segments of the Gloversville public, priorities of the police were influenced by different segments of the community at different times. For example, the following newspaper account reflects the ongoing tensions in Gloversville between business interests, the police, and the ‘public interest’ as expressed by newspaper’s reporting concerns over the open hours for local saloons on the weekends.

Chief of Police, Fred Sperber, provided summary statistics and prior year comparisons of the law enforcement profile of the city. Total arrests were 247, of which 232 were males and 15 were females. The total amount of fines paid were $445.00, equivalent in purchasing power to about $14,471.54 today. 118 ‘lodgers’ were ‘accommodated’ at the station house. [5]

“A comparison of the arrests for the year previous shows that the arrests for public intoxication decreased from 121 to 93. There were four grand jury cases last year, as compared with seven the year previous, and the general condition of the city is shown to have materially improved. At the present time the city is not oppressed by any thug element, and although there are a certain number of tough characters about the city, the police allow them little license and very few brawls or fights are reported.” [6]

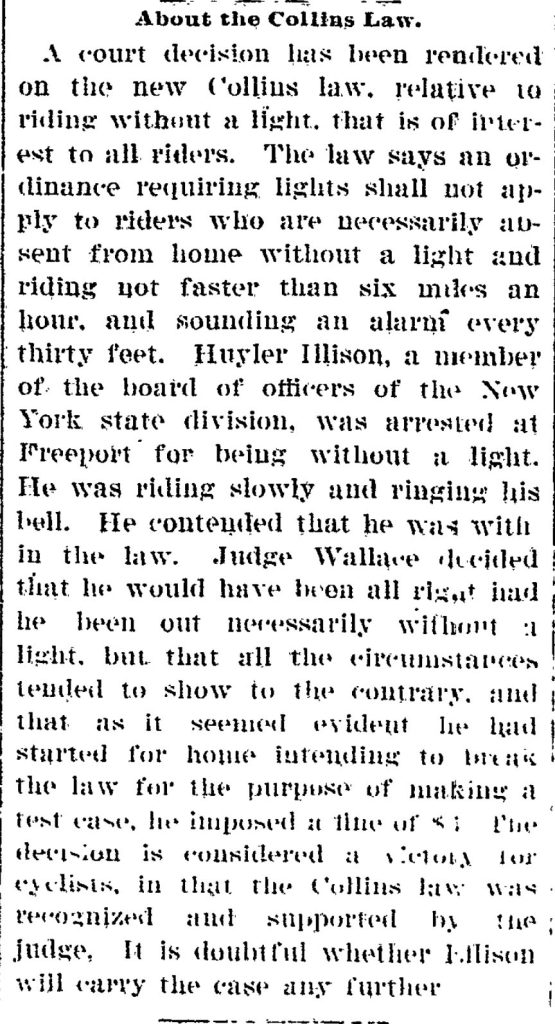

What is interesting is the prominent number of arrests for bicycle violations. The arrests for bicycle violations in Gloversville reflect a larger trend in the nation about complaints about bicycles in the 1890’s. These complaints and the resultant community-wide attempts to regulate new technology resemble the complaints often heard about electric scooters in contemporary times. [7]

“TO TEST THE LAW“

“C.F. Cumming went out last night to test the new Collins law concerning the carrying of a lamp on his bicycle, and after riding up and down the street he was arrested by Officer Louis Sperber.”

Source: The daily leader., June 22, 1899, Page 8

The case was disposed by Recorder (judge) McDonald. It was held that the Collins Law repealed all ordinances concerning bicycle riding and at the time of his arrest, Gloversville did not have any ordinances in place to arrest Cumming for the alleged offense… .

Source:The daily leader., July 14, 1899, Page 7

Bicycle Scorchers

See Jim Kellet’s short documentary “Victorian Cycles – Wheels of Change” on 1890s scorchers and the attempts to stop them in 19th Century Denver, Colorado.

Bicycles in Gloversville and Law Enforcement in the 1890’s

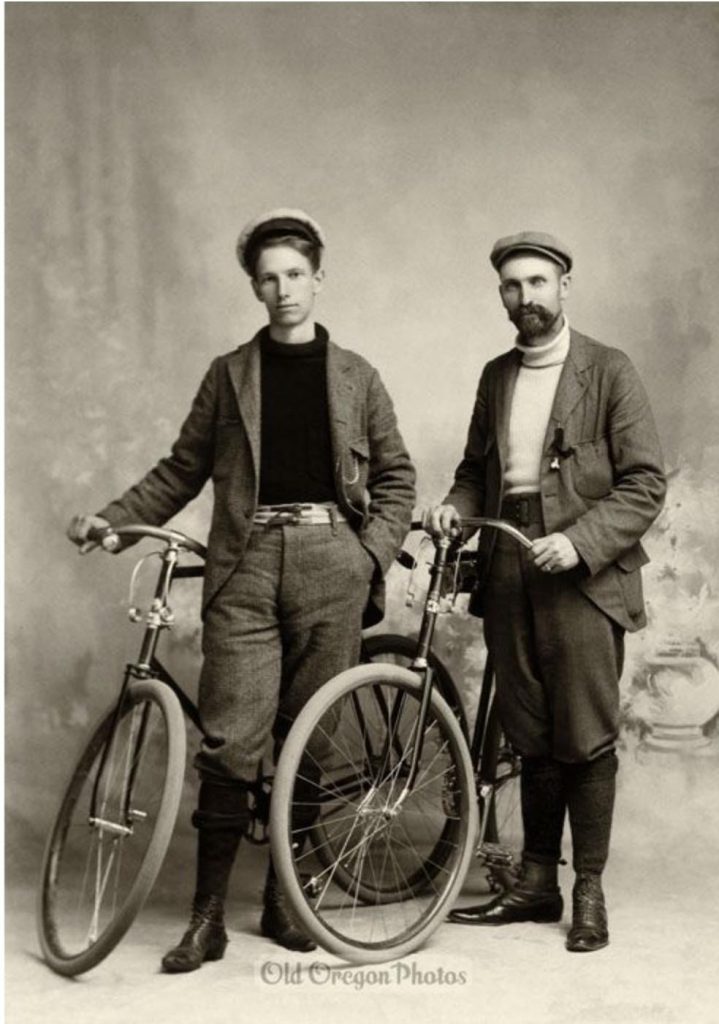

In the 1880s, the so-called safety bicycle was developed, emphasizing greater steering control and more even wheel sizes, giving the rider greater control and greater comfort. These new safety bikes also became the first bikes to be popular among both sexes and for different age groups. In the late 1880s, improvements with rubber wheels made bicycles also more able to travel rougher surfaces.

The safety bike entered already-crowded streets with pedestrians, single horses, horse-drawn vehicles, and electrified street cars. Safety concerns quickly arose. Bicycles were scattered about and not racked. People rode on sidewalks with no warning to pedestrians. Cities scrambled to catch up with the craze and began to regulate bicyclists with new city ordinances. [8]

As reflected in a number of newspaper articles in local newspapers, the Sperber brothers were soon caught up with enforcing a law that did not have Gloversville city ordinances in place on bicycle use. There are a number of newspaper articles that chronicled the interplay of bicycle activists pushing the limits of how the Gloversville police implemented a new law involving the use of the bicycle. [9]

The bicycle “scorchers” menaced the 1890s cities. While the modern day cyclist is often viewed by non cyclists as individuals disobeying traffic laws, the Gilded Age city dealt with ‘reckless bike riders’ first.

“Called “scorchers” for their speed, they gave the very trendy new sport of cycling a bad name and were much-discussed in newspaper articles of the day.” [10]

The newspaper article below documents the presence of “scorchers” in Gloversville. In April, 1890, when Fred Sperber was Chief of Police. With determination to put a stop to the great nuisance to pedestrians and horsemen, he assigned his brother, Louis, and another patrolman to a specific area in the city to control scorching. His efforts led to a few arrests.

“Ten cyclists have been arrested within a few days charged with violating city ordinances. Chief Sperber is determined to have the law obeyed and unless it is more arrests will be made.” [11]

Based on a newspaper story in one of the local newspapers, the president of the Gloversville Board of Directors felt it was important to publicly underscore his and the police force’s actions in upholding laws governing the management of saloons in Gloversville. He raised the issue in a town meeting and provided an affidavit signed by the chief of police and two of his policeman, including Fred Sperber, attesting to their enforcing existing laws and local statutes governing the management of saloons. This was during Fred Speber’s first year as a policeman.

“A Lively Meeting of the Board of Trustees Held Last Night“

The competing interests between businesses, religious elements, and local community interests in Gloversville defined the changing boundaries of what was considered as ‘social order’ and ‘crime waves’. The following arrests by Fred Sperber brought up larger issues concerning the serving of liquor to minors in the community.

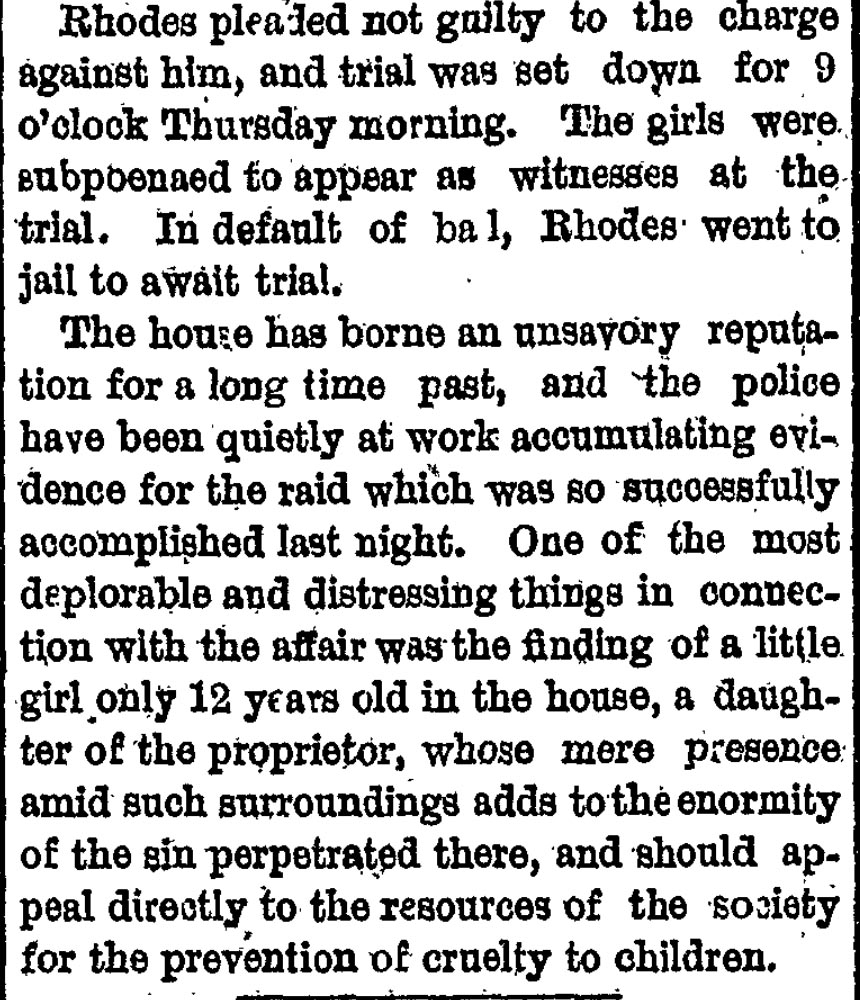

Public intoxication and prostituion were visible and persistent concerns in many cities in the late 1800’s. The following newspaper article reports on a raid of a “disorderly house”, located at 25 Judson Street in Gloversville. Fred Sperber was involved along with the entire police force in conducting the raid. The raid on the house of ill repute reflects the relationship between local political forces, the use of police and the changing concept of social order.

“One of the first movements made by this new city administration is a plain indication that the policy of the new ” powers to be” will be governed by cleanliness and that vice will be eliminated as far as possible.”

The following arrests in March 1894, depicted in a daily newspaper column, “Local Happenings”, describes two arrests by Fred Speber that involved two women who were maintaining a “disorderly house”. One of the two women were previously arrested by Fred Sperber for selling unauthorized liquor.

A similar news story chronicles the police raid of a “filthy resort” in Gloversville , of which Fred Sperber was part of the police raid. The proprietor of the house was subsequently sentenced to six months in prison. The maternal uncle assumed custody of the little girl. [12]

“The house has borne an unsavory reputation for a long time past, and the police have been quietly at work accumulating evidence for the raid… . One of the most deplorable and distressing things in connection with the affair was the finding of a little girl only 12 years old in the house, a daughter of the proprietor, whose mere presence amid such surroundings adds to the enormity of the sins perpetuated here, and should appeal directly to the resources of the society for the prevention of cruelty to children.”

As a result of a death of a woman who had frequented a saloon in Gloversville, Fred Sperber, as the Chief of Police, ordered certain saloon keepers to keep women out of their places and cease the practice of making their saloons “resorts of dissolute characters“. As stated in a March 26, 1902 news article [13], one of the most stringent orders ever issued by the police was served on various saloon keepers in person by the Police Chief.

The woman She was found at the bottom of a rear stairway of a local saloon at nine in the morning. A worker from a nearby creamery found the body at in the morning and notified the police. Louis Sperber initially was sent to investigate. He found the body and the coroner was summoned. There was enough to give an impression that the woman had been struck and staggered from the saloon. An investigation was immediately started by Chief Fred Sperber and the district Attorney Egelston. Authorities were told that deceased told other people that she was going to commit suicide while in the saloon the previous night and she was seen with ‘white substance’ on her lips.

The episode created such a stir that saloon keepers were ordered not to permit women to enter their establishments. Members of the police force were ordered to arrest any woman seen coming out of a saloon and evidence that women have been in a saloons would cause actions to be commenced against the proprietors for keeping disorderly houses.

“Crimes which have never reached the ears of the public and of which the police have only been able to get clues, have been perpetuated in some of the places, and Chief Sperber concluded that the only way to stop the practice was to order all the saloon keepers to prohibit women coming into places and to arrest all women who went into the saloons.” – The GloversvilDaily Leader

One of the saloon owners,. Charles Whiskey, personally visited Chief Sperber to lodge a complaint against one of his patrolman who was stationed outside of this establishment, asserting that it was hurting his business. “It took Chief Sperber about thirty seconds to convince Whiskey that he had come to the wrong place and the saloon keeper was plainly informed that until he stopped the practice of allowing women to congregate in his place a policeman would be stationed near his place.” [14]

Police in Gloversville in the late 1800’s

It was not until the 1830s that the idea of a centralized municipal police department first emerged in the United States. In 1838, the city of Boston established the first American police force. New York City followed in 1845, Albany, NY and Chicago in 1851, New Orleans and Cincinnati in 1853, Philadelphia in 1855, and Newark, NJ and Baltimore in 1857. By the 1880s all major U.S. cities had municipal police forces in place. [15]

During this era, as indicated, police represented the local politicians and the commercial interests in the neighborhoods that they patrolled. There was no civil service systems until the late 1800’s and the turn of the century. Police officers were hired, fired and managed at the discretion of the local politicians. Politicians ran police precincts as small departments. This meant that the mission of the police was also the same mission of their local politicians. The police had to handle community crime problems that favored the predilections of local politicians.

In Gloversville and Johnstown, officers were selected for their political service by a local town board (the common council) and the police officer owed his allegiance to the mayor and the common council of the town. It is not known how one initially requested to be a policeman. It is presumed that there was a process of submitting a request to be considered for the position. A vote by the common council was then held to select individuals for each of the authorized positions. Tenure as a policeman was not guaranteed. Gloversville policemen were selected through annual votes by the local government.

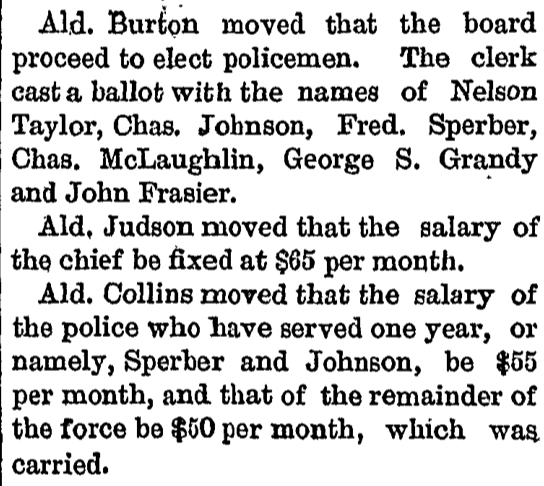

The following snippet from a Gloversville newspaper article in 1890 reflects the by-laws associated with the Gloversville Common Council and their power over the selection and payment of wages of police officers. [16]

Duties of the Gloversville Common Council

As reflected in the following newspaper announcement, the Gloversville police were selected on an annual basis through nominations and voting through the common council. [17]

Business Transactions by the Common Council

New officers were sent on patrol with no training and with few instructions. Most of their training relied on innate street smarts, the ability to get along and judge people, and learning from their peers and experience. A police officer was considered a decent job but had extremely poor job security due to political turnover.

Police officers were intimately connected with the social and political community. Police had limited supervision and an enormous amount of discretion. During this era, police were on foot patrol and knew their communities very well. Through their experience, they “knew who was supposed to be where and who was not” in various areas of the city. The police recognized potential crime problems based on the intelligence they received from members of the community and what they observed on a daily basis.

Walking the Fine Line

Police work was a daily balancing act of protecting property, the citizenry, and enforcing the changing political priorities. Sometimes on-the-spot decisions were not in the Sperber brother’s favor. The following string of newspaper articles between September 11th – 27th, 1890 chronicled an emerging dispute between Fred Sperber and the editor of the Gloversville Standard newspaper. This was during his second year as a policeman.

Fred Sperber was ‘accused’ of preventing a resident from entering his house when it was on fire. The editor of the Standard made a public statement rebuking Sperber’s actions. Sperber subsequently paid a personal visit to the editor’s office and evidently gave him a piece of his mind. The newspaper editor subsequently had officer Sperber arrested and Fred was placed under bail for $200. Under the banner of “The Freedom of the Press”, the Gloversville Standard reported that the Gloversville city council suspended Officer Sperber for unbecoming behavior and was ordered to apologize to the editor. It is not known how long Fred Sperber was suspended.

As reflected in subsequent newspaper stories, Fred Sperber evidently learned his lesson about one’s conduct with politicians and the “fourth estate” (newspaper editors and reporters) and moved on from this episode and continued to do police work for the following eight years.

Police and Civil Service Reform

Public support in the United States for civil service reform strengthened following the assassination of President James Garfield. The United States Civil Service Commission was created by the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, which was passed into law on January 16, 1883. The commission was created to administer the civil service of the United States federal government. The law required federal government employees to be selected through competitive exams and on the basis of merit. It also prevented elected officials and political appointees from firing civil servants, removing civil servants from the influences of political patronage and partisan behavior.

The federal law did not apply to state and municipal governments. The state of New York was one of the first states to enact a law similar to the federal law. Within a few months, an Assemblyman named Theodore Roosevelt routed a bill through the state legislature and Governor Grover Cleveland signed the measure into law on May 4, 1883. This law provided for a New York State Civil Service Commission consisting of three commissioners: two from one party and one from the other. Appointments to the new commission were made by the governor and they wasted no time getting together. The first meeting of the newly formed New York State Civil Service Commission was May 31, 1883. [18]

The implementation of civil service reform in New York state was not a smooth process. Within the year of the state’s signing of the law, new legislation was enacted that extended the concept of merit system administration to municipal levels of government. However, word of this new law did not get to some of the towns and villages until the late 1990s. 1894 was a landmark year for civil service in New York State. A constitutional convention was called and some changes were made to the constitution of New York State. As a result, article V, Section 6 of the New York state constitution was modified to read:

“Appointments and promotions in the civil service of the State and all of the civil divisions thereof, including cities and villages, shall be made according to merit and fitness to be ascertained, as far as practicable, by examination which, as far as practicable, shall be competitive, …” [19]

For many years, those in power at various levels in the state government, statewide or local municipalities, simply chose to ignore this new constitutional amendment or bastardized the process so much that the appointing authorities were still able to achieve their goal of hiring friends, family and political patrons. [20]

It was during this period of time that the Sperber brothers were policeman. Despite the enactment of the civil service reform in the state constitution, local governmental entities implemented their own unique interpretations of how policemen and civil servants were selected. While the police in Gloversville in the 1880’s and early 1890’s were selected and managed by local municipal committees, there appeared to be some aspects of civil service requirements .

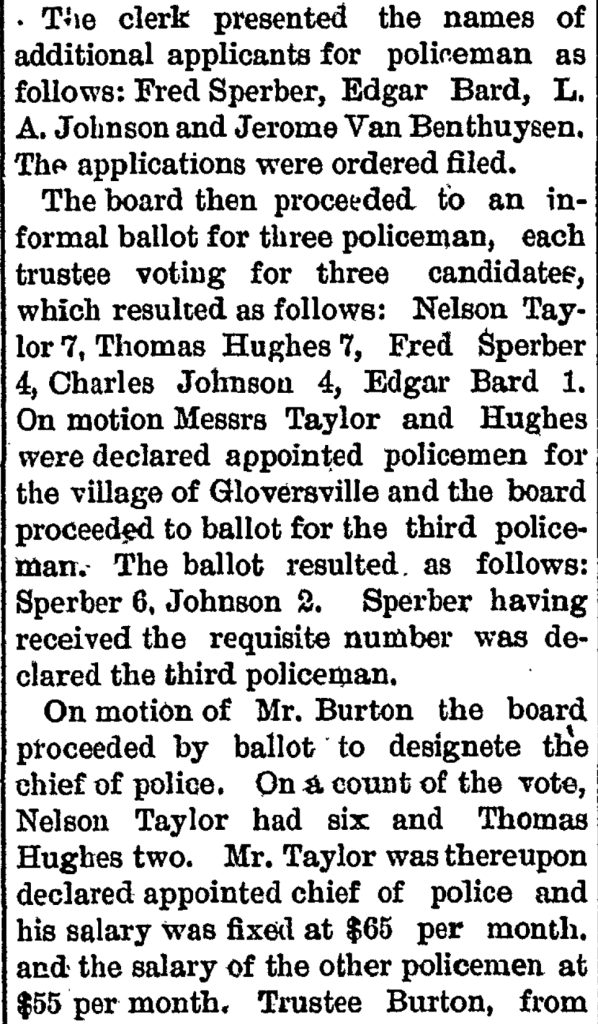

The following local newspaper article reflects the process of becoming a policeman in Gloversville and the determination of police salaries. This was the second year in which Fred Sperber was a policeman. [21]

Fred Sperber Elected as Policeman in 1891

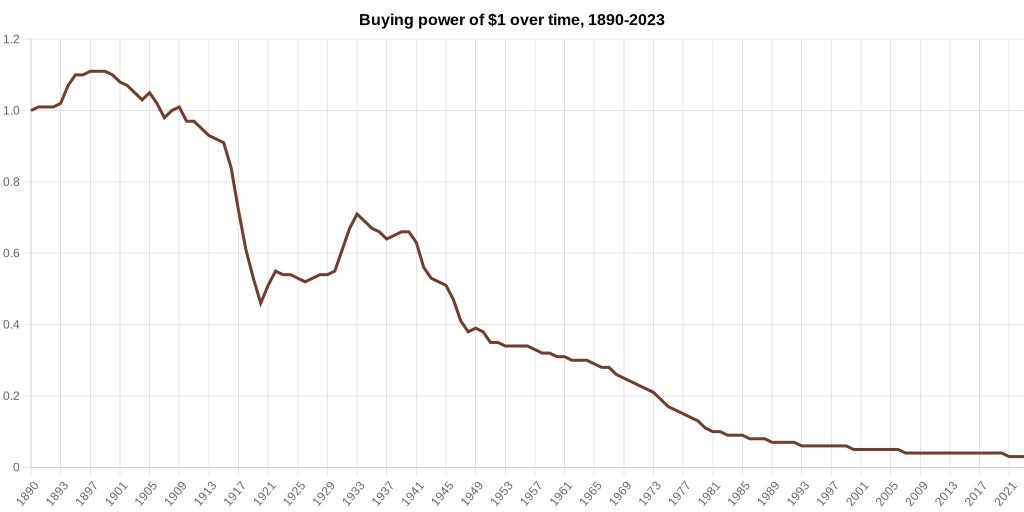

A Series 1890 $1 Treasury Note depicting Edwin Stanton with the signatures of William Starke Rosecrans and James N. Huston. Stanton served as U.S. Attorney General (1860–61) and U.S. Secretary of War (1862–68)

Source: Wikipedia Image https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:US-$1-TN-1890-Fr-347.jpg

A side note should be made regarding Fred Sperber’s salary. While he was not ‘abundantly rich’, Fred Sperber had a comfortable standard of living in 1890. Since Fred Sperber was a policeman for one year, in 1891 he received a $5.00 monthly raise to his salary. He worked a 12 hour shift, either a night shift or day shift. Fifty- five dollars in 1890 is equivalent in purchasing power to about $1,847.45 per month in today’s world. [22] This translates to a modern day annual salary of $22,169.40. While that may seem low, the cost of food, housing, and other living costs were considerably lower than they are today.

During the time when the Sperber brothers were policemen, in an effort to take the teeth out of the constitutional amendment, Governor Frank S. Black passed the Black Law in 1897. The Black law removed the exclusive right to give examinations from the hands of the state Civil Service Commission and handed it right back over to the local government entities. Teddy Roosevelt succeeded Frank Black as governor in 1899. Roosevelt took up his old cause of a fair and impartial civil service system and had Senator Horace White draft and sponsor new legislation that would replace the Black Law. This legislation became known as the ‘White Law’. It tightened up several of the loopholes in the existing system and gave the power of examination back to the commission. [23]

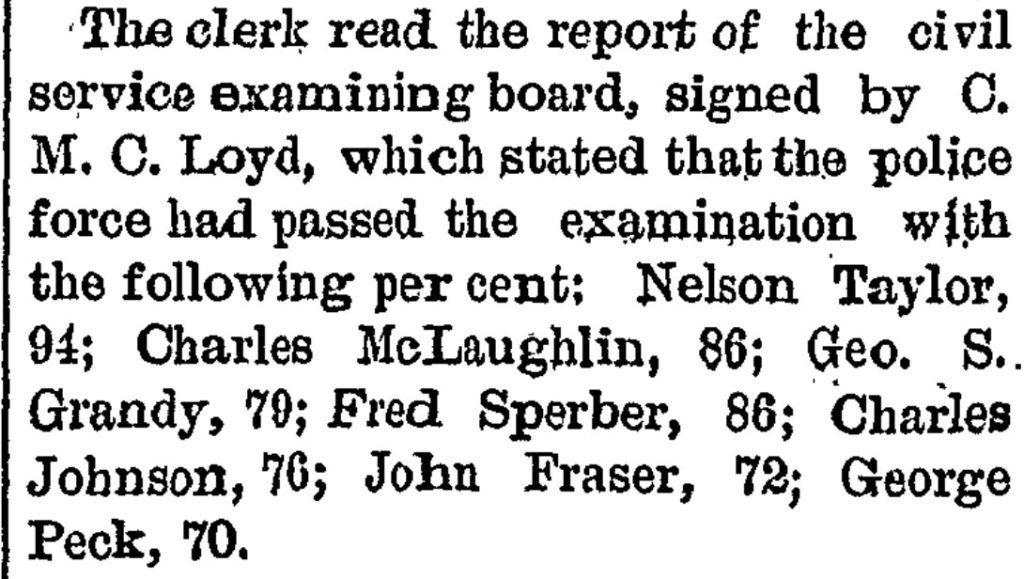

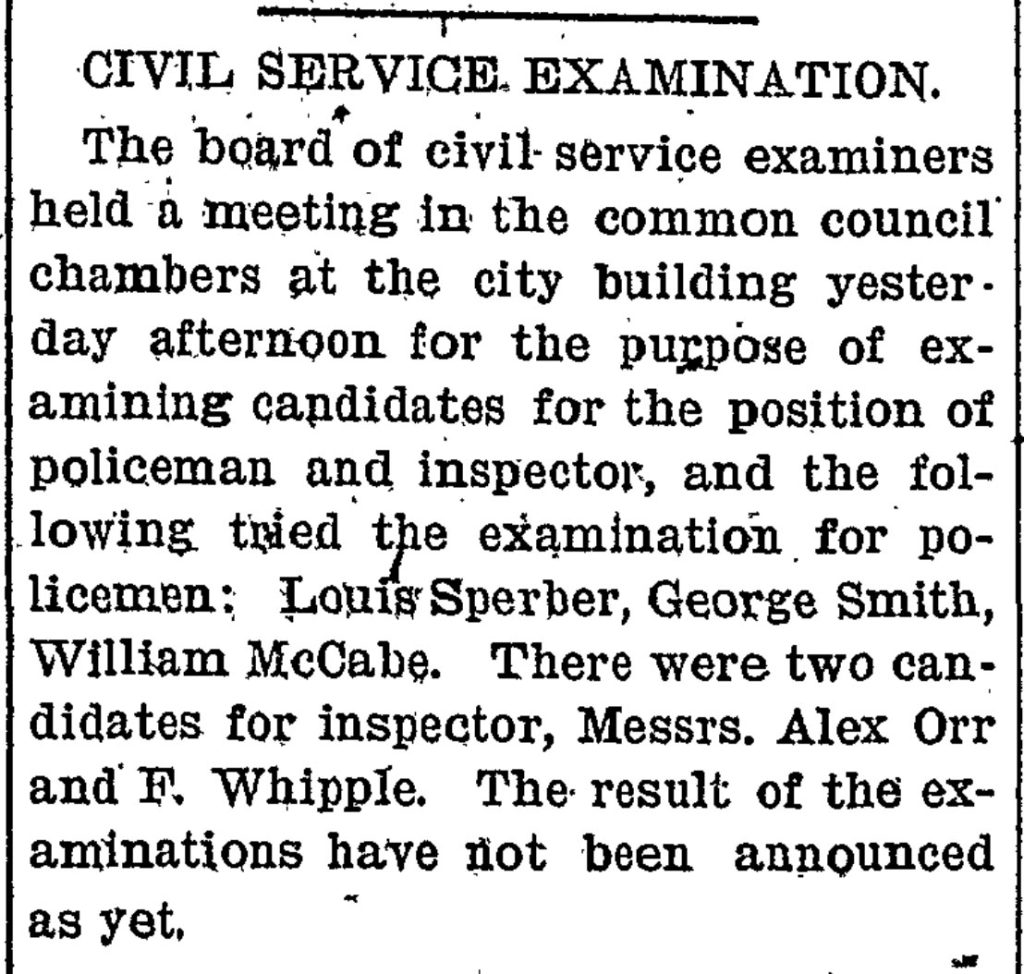

It appears that the Gloversville Police were required to take civil service exams, As reflected in the following March 24, 1891 and March 24, 1898 newspaper reports in the The daily leader..

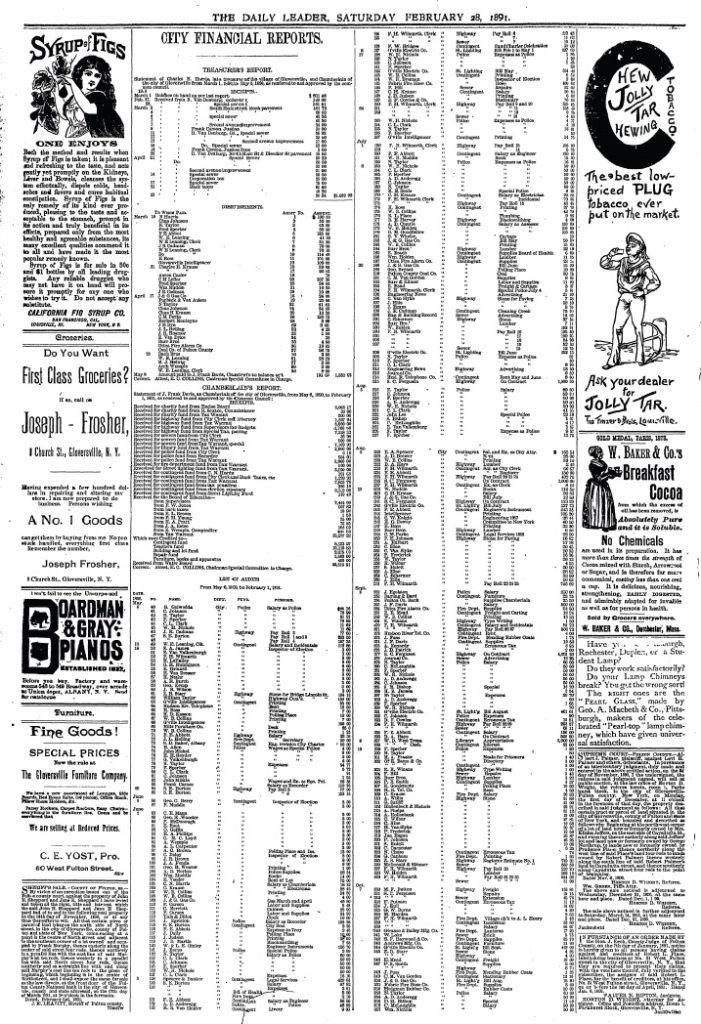

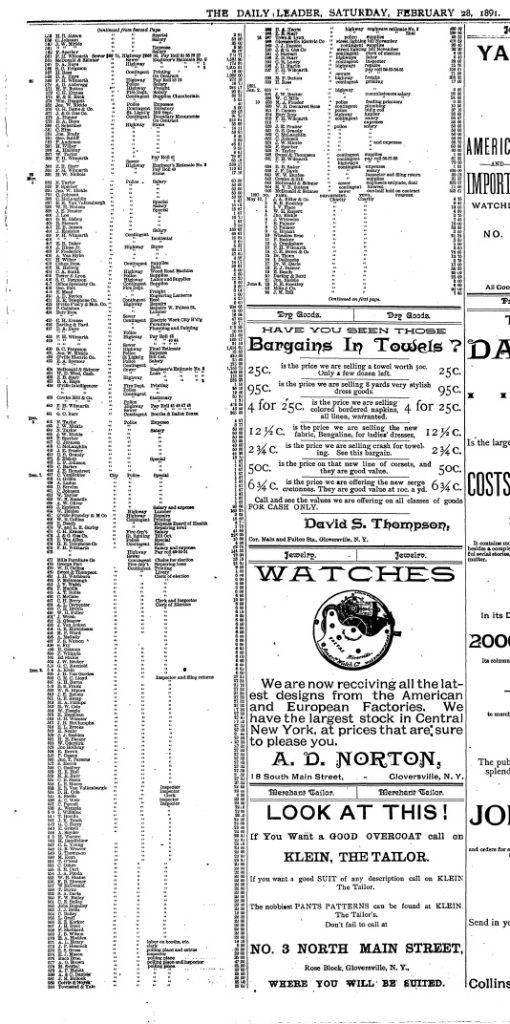

Coupled with civil service exams, the city also conducted audits of police spending on a recurrent basis. A Gloversville Treasurer’s Report of the city’s finances indicates the presence of financial controls and accountability during this time period. The funding of payments of police salaries were audited 122 times between May 6, 1890 through August 7, 1891. Payments to Fred Sperber were reviewed on thirteen occasions. [24]

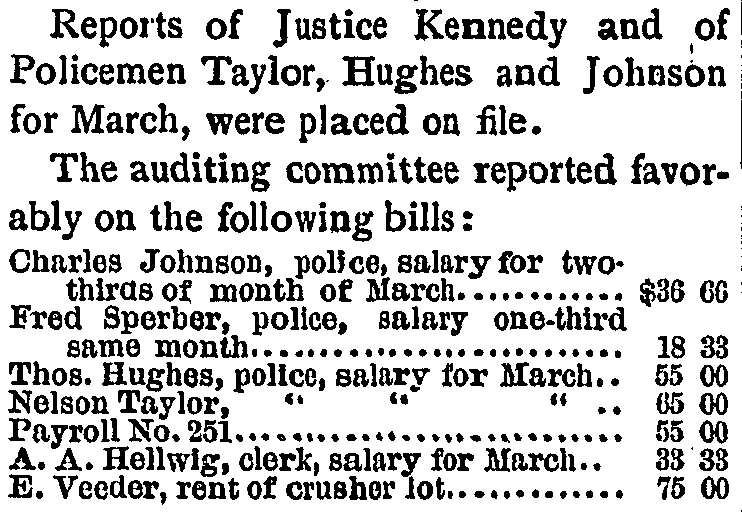

The following was reported in the local newspaper, The Gloverville Daily Leader. The brief news story reflects that the city regularly audited city bills for various services, including police work. The story also reflects the level of pay for a policeman in the early 1890’s. Fred Sprerber received thrty-three dollars for working hours in one-third of a month. [25]

Results of the Audit Committee

The Sperber Brothers: Their Lives in Gloversville

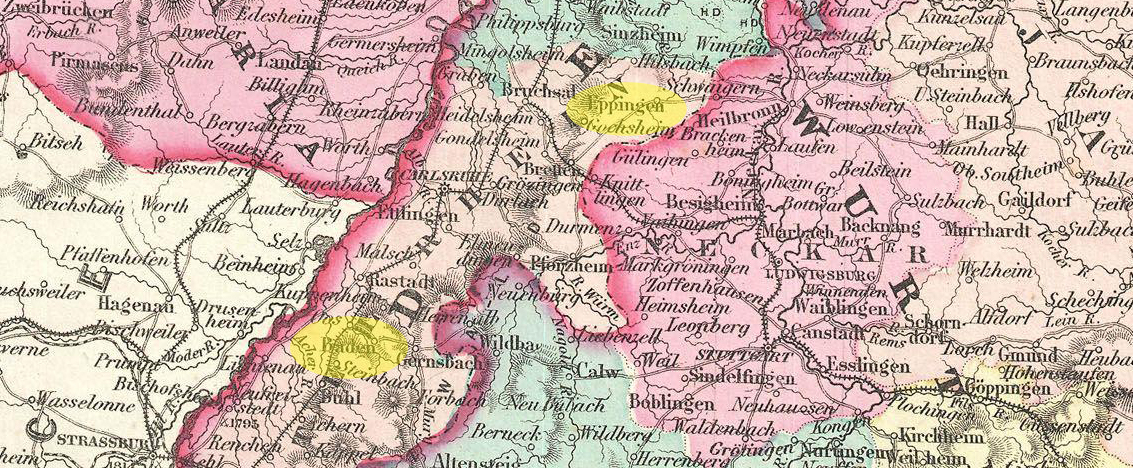

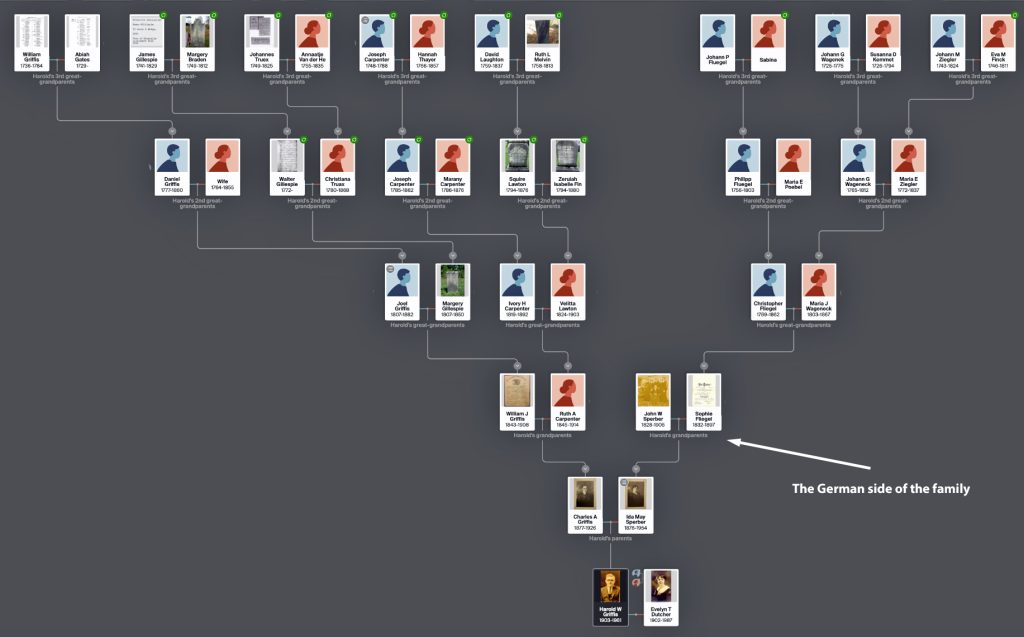

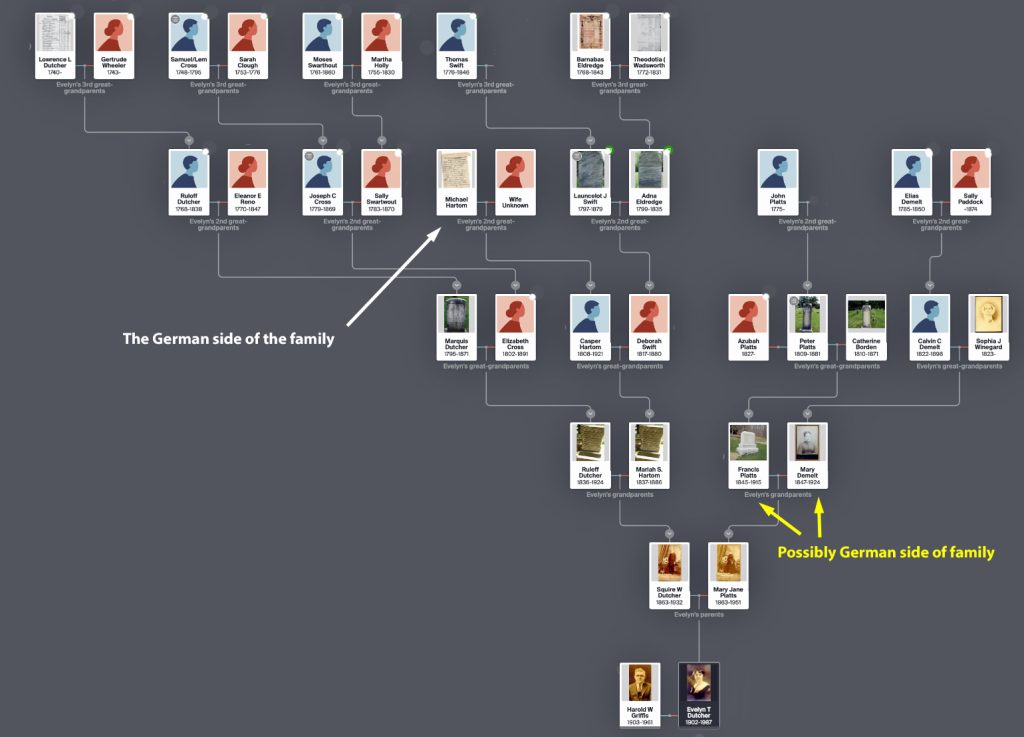

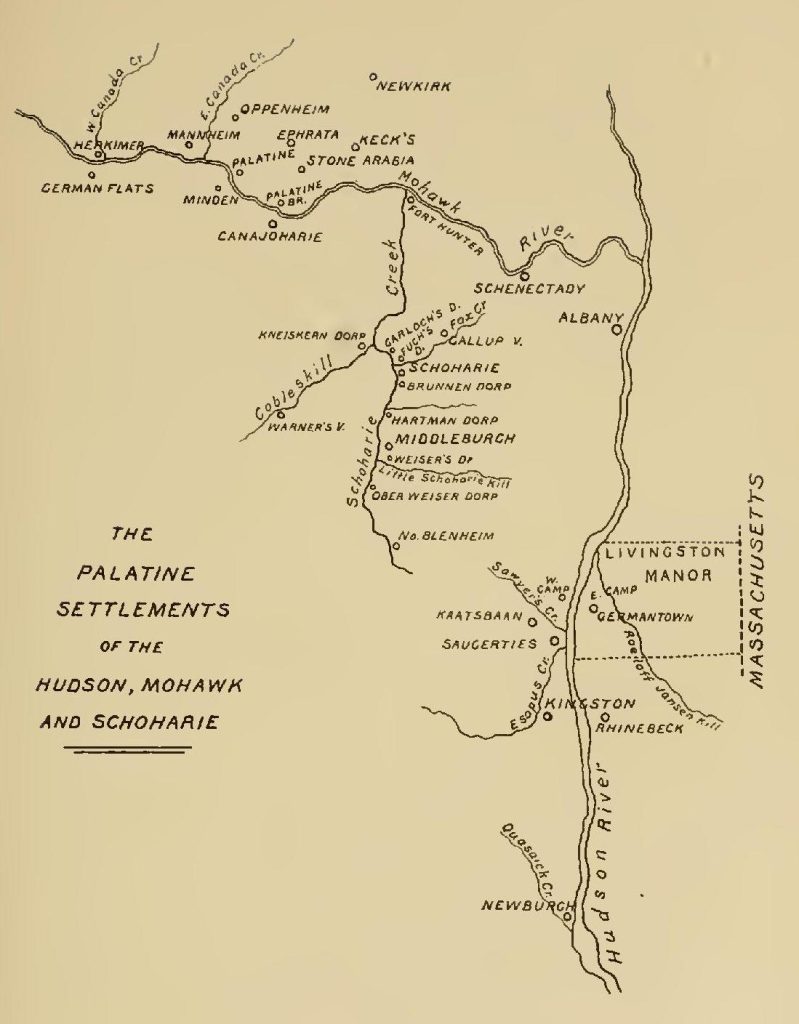

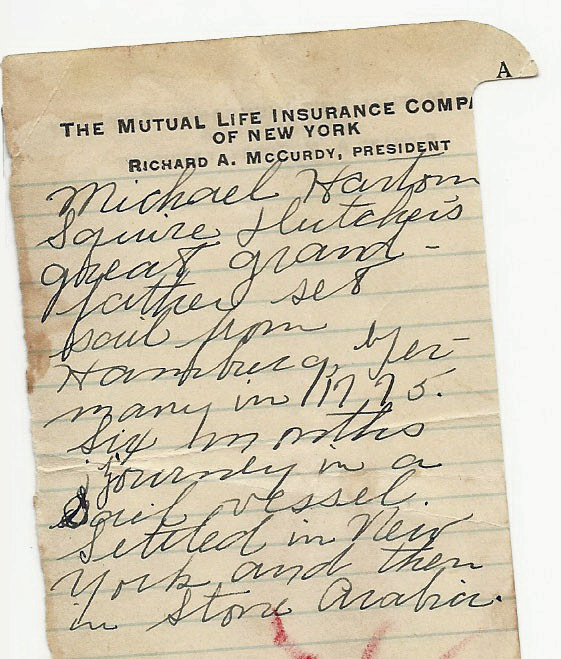

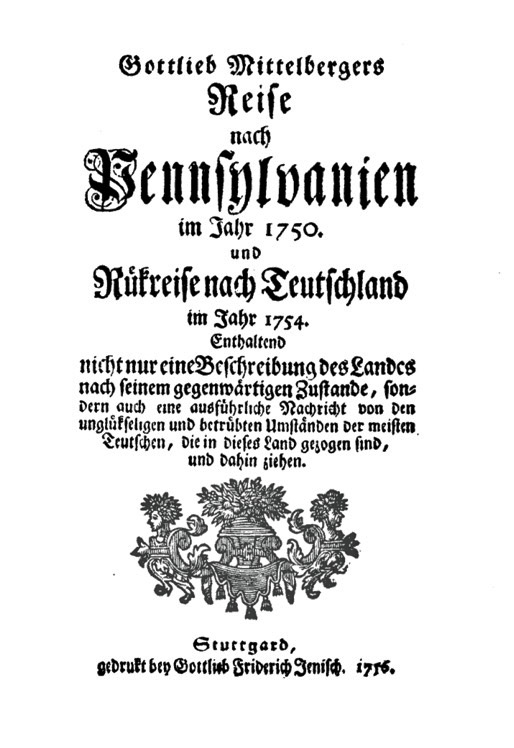

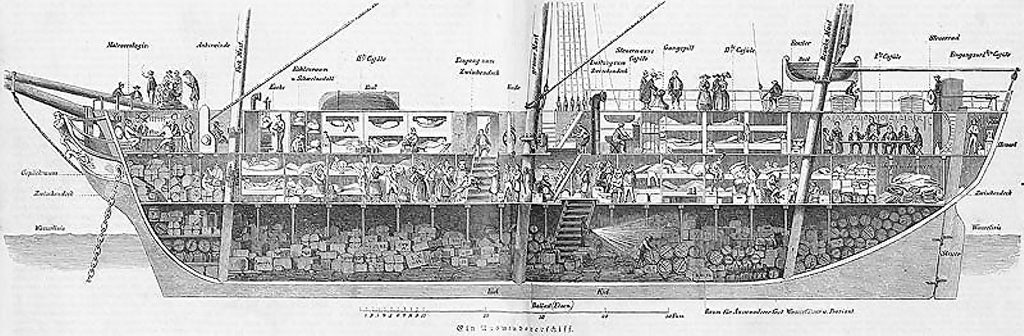

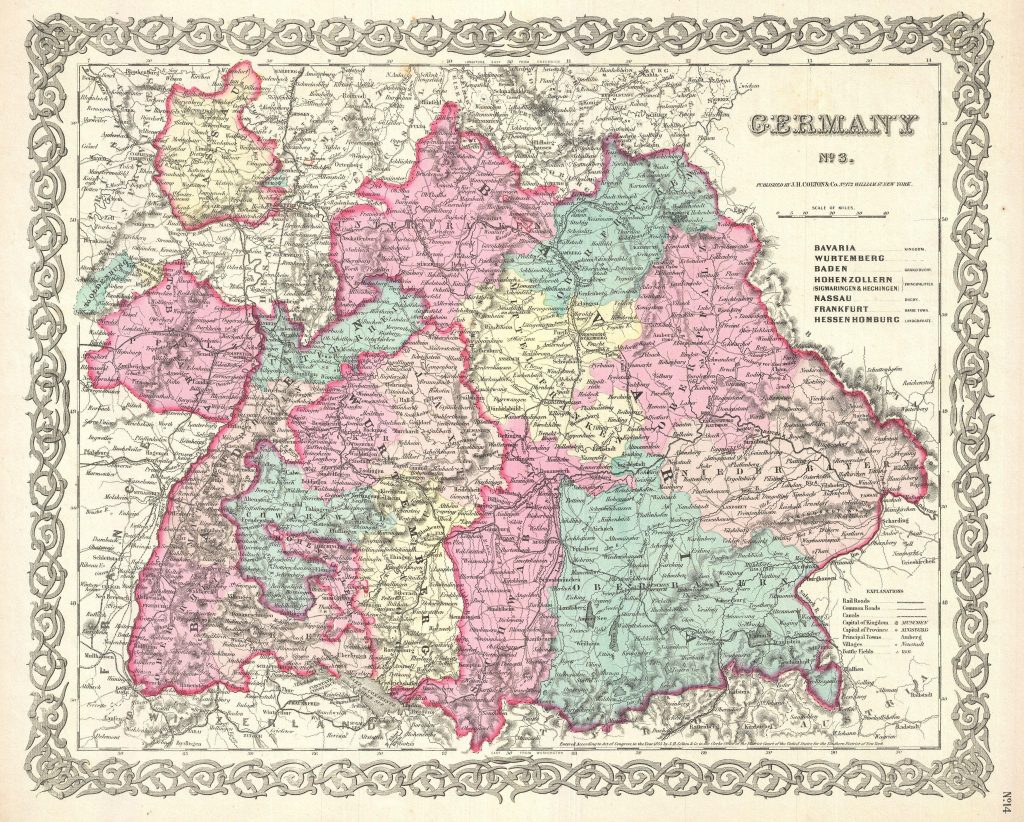

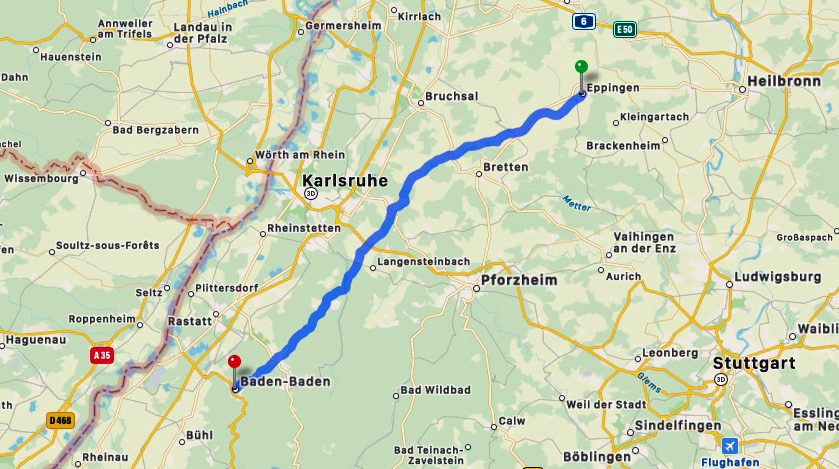

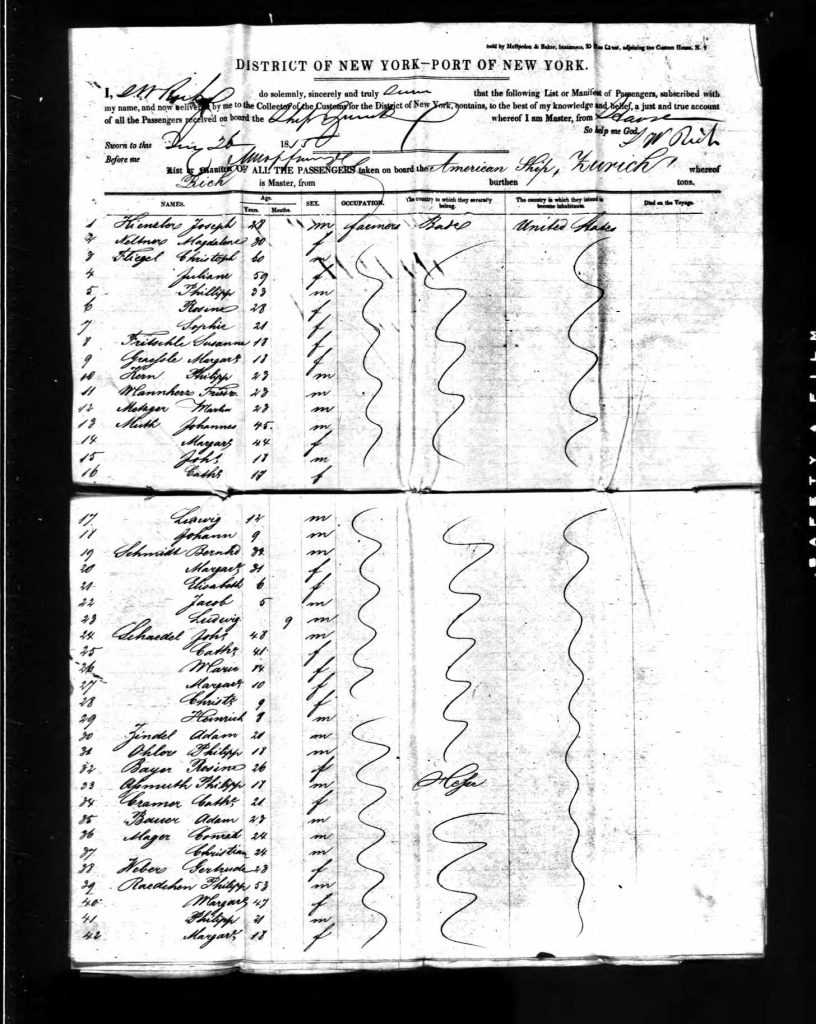

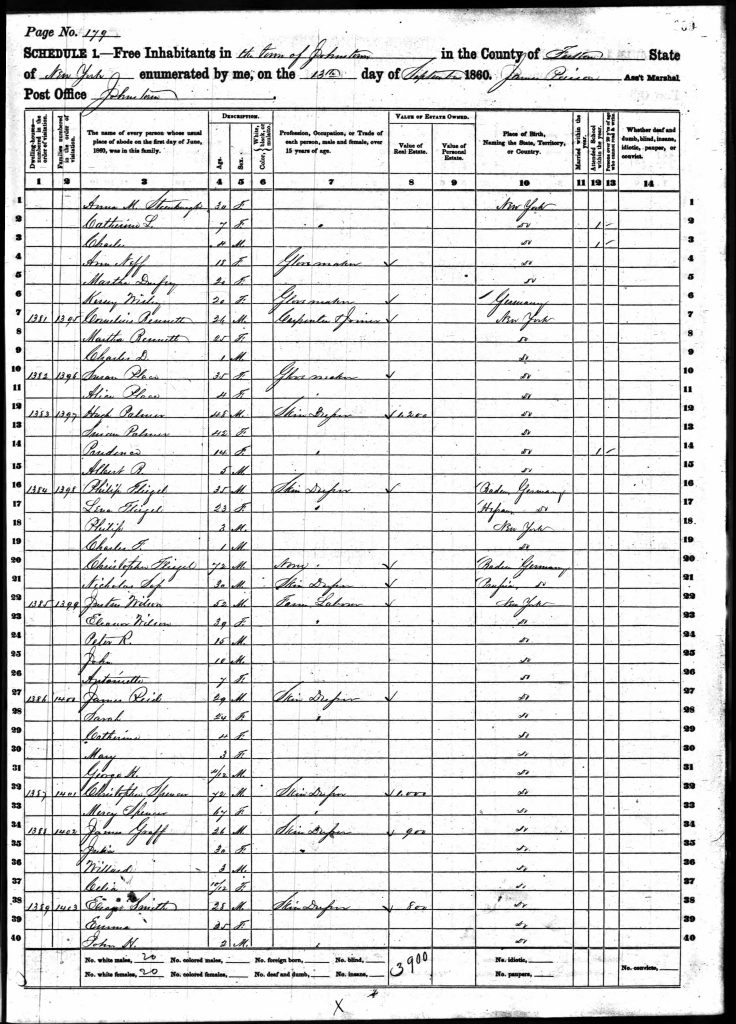

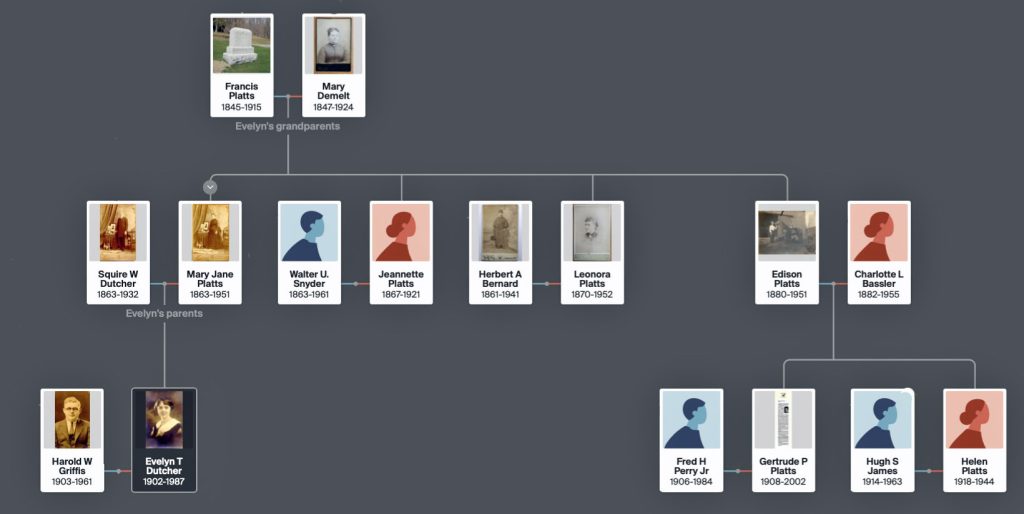

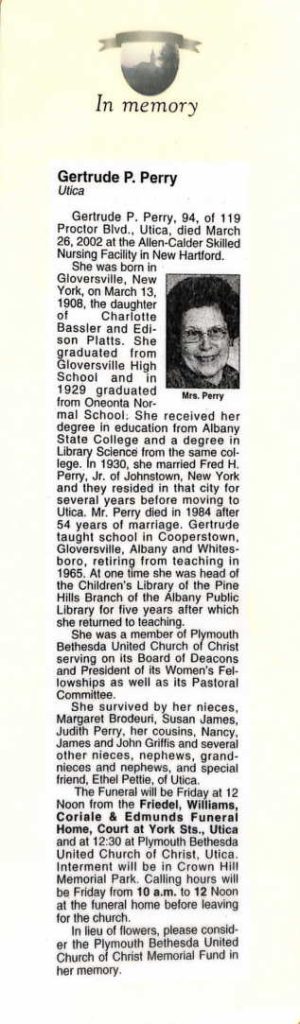

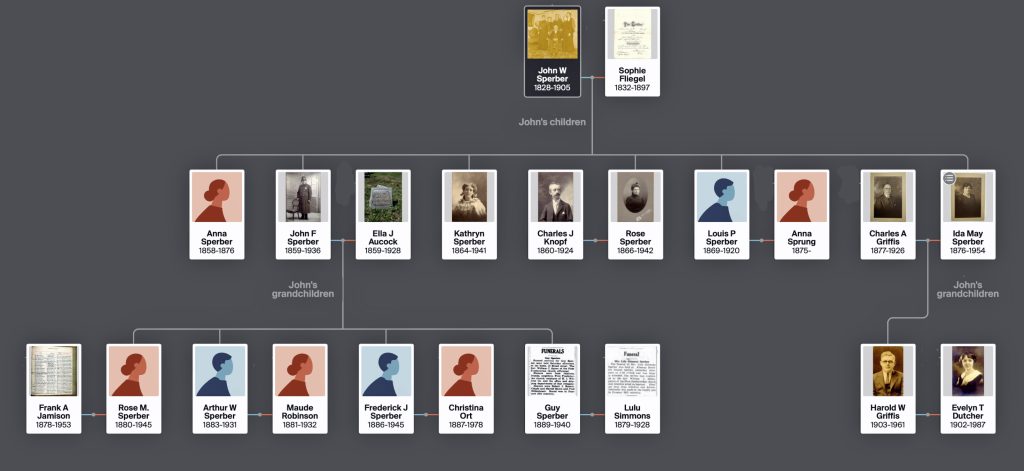

John Frederick Sperber and his younger brother Louis P. Sperber were the first generation of their family to be born in the United States. They were both uncles to Harold Griffis. Their father, John Wolfgang Sperber, and his mother, Sophia Fliegel, grandparents of Harold Griffis, immigrated to the United States in the mid 1850’s just before the country was torn into two with the American Civil War.

John and Sophie married in the United States and quickly started a family. When John Frederick Sperber was born in December 1859 in Johnstown, New York, his father, John, was 31 and his mother, Sophie, was 27. Louis Sperber was also born in Johnstown, the second son and the fifth of six children in the family. He was ten years younger than his older brother.

Based on local newspaper accounts, it appears that John Frederick preferred to use his middle name Frederick or Fred rather than his first name. So I will refer to John Frederick Sperber as “Fred Sperber” throughout this story.

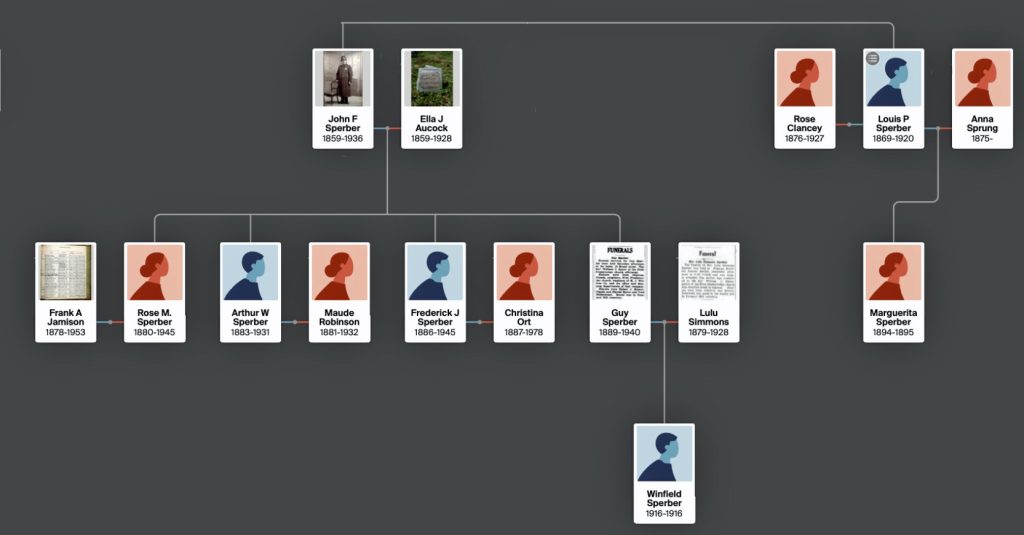

As reflected in the family trees below, Fred Sperber and Louis Sperber were maternal uncles of Harold Griffis.

Family Tree of Fred and Louis Sperber

The Two Brothers: Family Trees

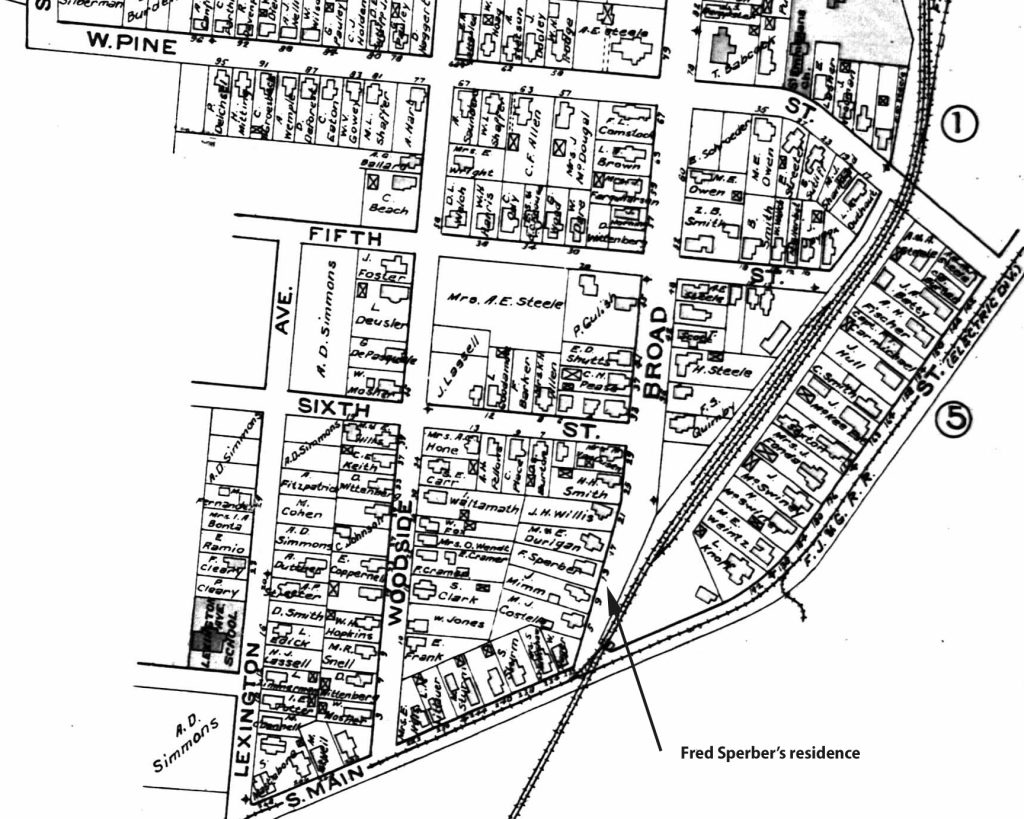

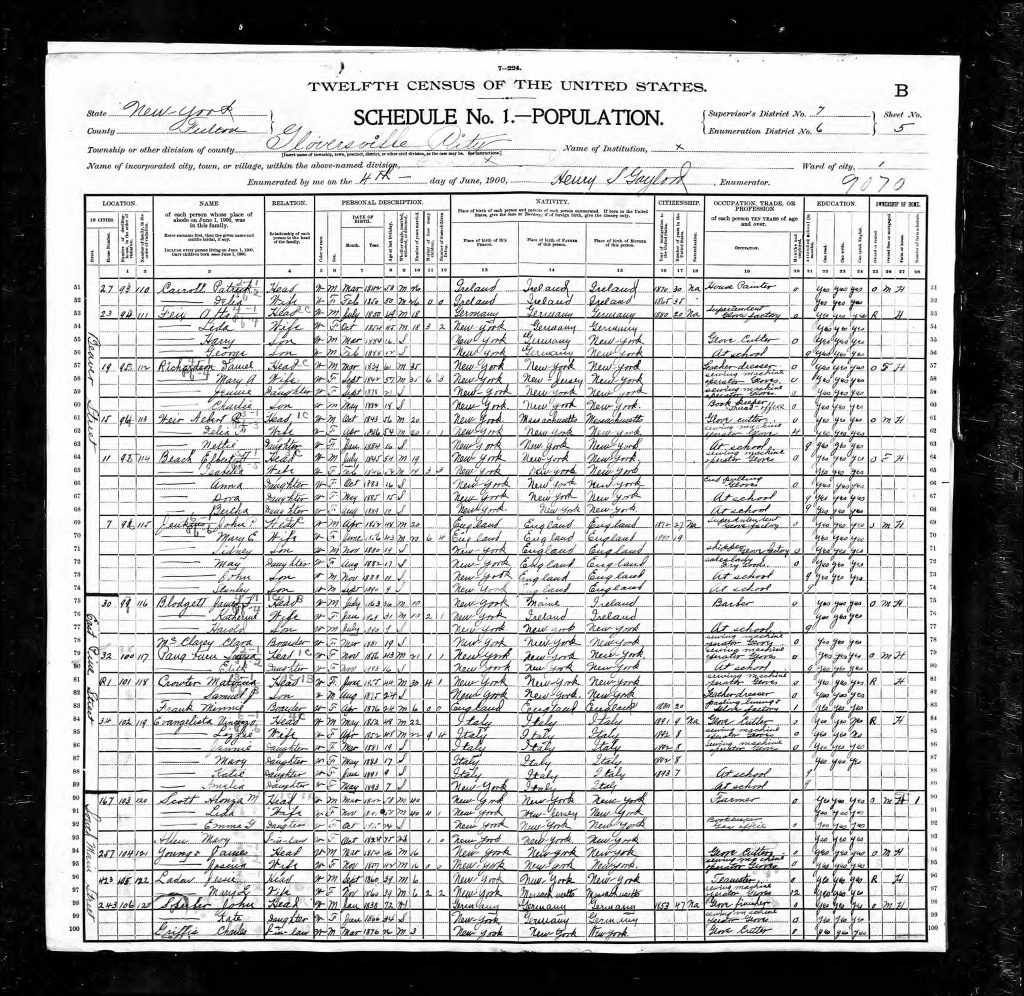

Both Fred and Louis Sperber lived their entire lives in the Johnstown – Gloversville, New York area. A review of U.S Census documents indicate that Fred lived in the same house, located at 13 Broad Street, Gloversville, New York, for over 40 years. [26]

Residence of Fred Sperber, Gloversville 1905 [27]

Fred Sperber married Ella J. Aucock. Fred lived with his parents and siblings until he purportedly married Ella at the age of 19. However, documentation, such as a marriage certificate or written affirmation of the date of marriage on what date Fred and Ella were married are not available. The 1880 Federal Census indicates that Fred lived with his parents and siblings. [28] Ella is not listed as living with Fred in this household. She is reported as living with her parents in 1880. [29] The 1880 census in the Glovesville area was conducted on June 1st , 1880 for the Sperber household and June 10th for the Aucock household. Fred and Ella were married in the latter part of the year. In later census enumerations, they reported they were married in 1878 or 1880.

Their first child, when Fred was 19, was born in 1878. They had four children during their marriage: Rose Sperber (180 – 1945), Arthur Sperber (1883 – 1931), Frederick John Sperber (1886 – 1945) and Guy Sperber (1889 – 1940). Fred Sperber psssed away on July 5, 1936 at the age of 76. [30]

Louis P. Sperber resided in various rental properties in Gloversville, New York. In 1890, he lived with his father at 155 South Main Street. He married Anna Sprung in 1893. They had a daughter Marguerita who was born August 5, 1894. However, she passed away at the age of 8 months on April 8, 1895. [31] In 1895 he and Anna lived at 3 Woodside Ave. In 1900, he and his wife Ann, lived with her mother Kate Sprung at 14 Washington Street. In 1902 he and Anna lived next door to his mother in law , at 14 Washington Street. In 1903, they resided at 18 Spring and in 1904 at 32 Elm Street. In 1909 through 1912 Louis and Ann, along with her mother, lived at 25 S School. [32] While it is not known when Ann passed away, Louis P Sperber remarried Rose Clancey in 1913. [33] Louis Sperber died at the 51 on September 15, 1920. [34]

The Brothers’ Careers in Gloversville

Both brothers had varied careers in the glove industry and local law enforcement. Fred also worked as an Expressman for two years when he was in his late 40’s after he was police chief.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, an expressman was someone whose responsibility was to ensure the safe delivery of gold or currency, being shipped by railroad. This job included guarding the safe or other strongboxes or coffers and memorizing the safe’s combination to use at delivery. It was a job that Fred Sperber could easily slide into as a former policeman.

“The expressman served not only as a courier, but as a highly ethical agent of currency, documents and other high-value items, and was considered a highly valuable employee.” [35]

It was natural for both Fred and Louis to spend some of their productive years in the tanning or glove making industries. Their father, John (Johann) Wolfgang Speber, spent virtually all of his gainful employment in the glove making industry after he arrived in the United States. Once having worked as a glove maker, it was an occupation or an industry that one could easily return to or leave, depending on job prospects and opportunities. It provided a ‘safe haven’ for employment in Gloversville or Johnstown, New York.

“(G)loves and mittens were first manufactured in the United States in what is now Fulton county. As the industry became of commercial importance the number of families that depended upon it for a livelihood increased, until nearly every man, woman, and child in the surrounding country became proficient in the making of some special part of the glove or mitten. Foreign cutters coming to this country naturally settled in Fulton county. In this way the industry became localized, and contemporaneously came the development of the tanning industry and the establishment of factories engaged in making glove and mitten dies.” [36]

Based on a review of Federal and New York state census records and Gloversville City Directories between 1875 and 1924, as reflected in Table Two below, Fred Sperber and Louis started their work lives in the glove making industry. Fred Sperber was a glove maker and glove finisher between the ages of 16 and 21 years. He was a butcher and glove finisher in his mid twenties up to the age of 30.

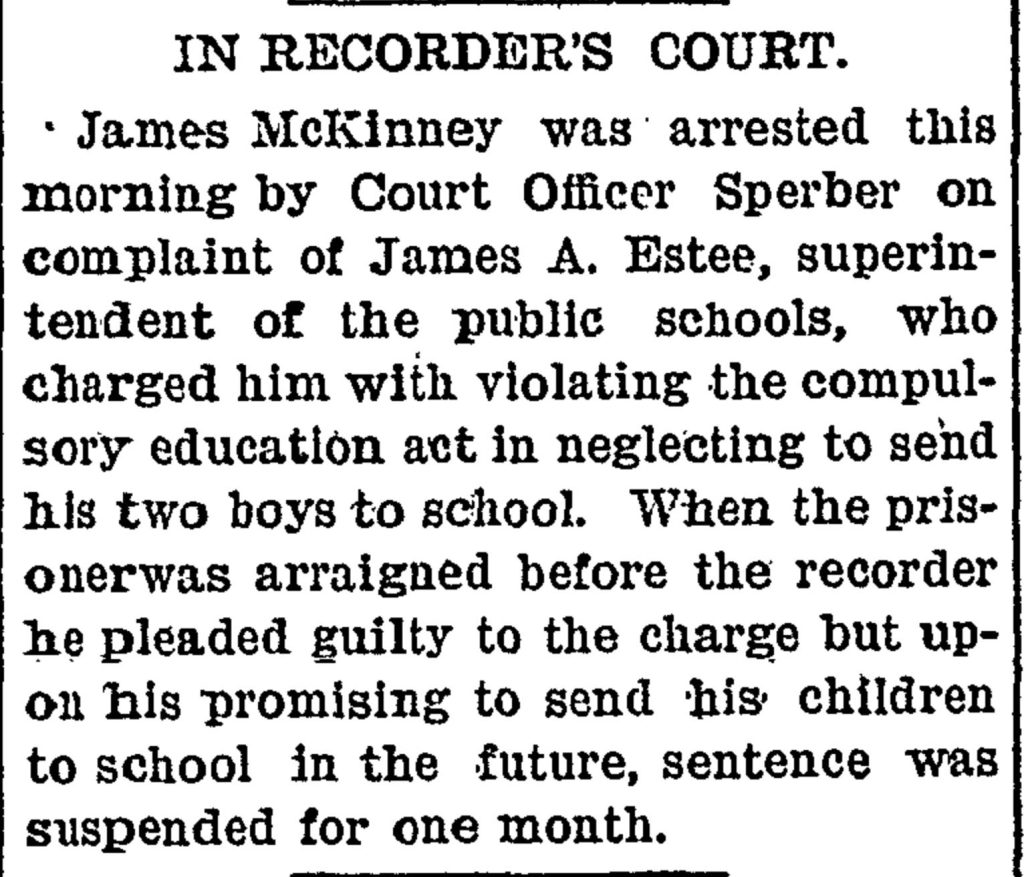

It appears, based on various newspaper articles published in the Daily Leader, that Fred Sperber was a “Court Officer” between 1895-1899. In addition to duties of protecting the Recorder or city judge, Fred Sperber also served court papers, executed warrants for the arrest of fugitives of the court, escorted sentenced prisoners, and went after fugitives of the court. In many ways, his duties mirrored the duties of a deputy U.S. Marshal at the local level. [37]

In February of 1896, Fred Speber was also given the responsibilities of truant officer in Gloversville. This came with an $5.00 per month salary increase compatible to $162.60 in current U.S. dollars. [38]

While I could not find Louis Sperber in the local city directories when he was in his teens and twenties, it is presumed he started work at the age of 16 and probably worked as a glove maker. Between the ages of 21 and 23, he is listed as a “Glover” in the Gloversville City Directory. At 24, he lists his occupation as a “Tanner”.

Table Two: Occupations of Fred and Louis Sperber

| Year | Fred Age | Sperber Occupation | Louis Age | Sperber Occupation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1875 | 16 | Glove Maker | 6 | At School | N.Y State Census |

| 1880 | 21 | Glove Finisher | 11 | At School | U.S. Federal Census |

| 1884 | 25 | Butcher | 15 | Not Stated | Gloversville City Directory |

| 1885 | 26 | Glove Finisher | 16 | Not Stated | Gloversville City Directory |

| 1889 | 30 | Listed as Butcher but was policeman in ’89 | 20 | Not Stated | Gloversville City Directory |

| 1890 | 31 | Policeman | 21 | Glover | Gloversville City Directory |

| 1891 | 32 | Policeman | 22 | Glover | Gloversville City Directory |

| 1892 | 33 | Policeman | 23 | Glover | Gloversville City Directory |

| 1893 | 34 | Policeman | The daily leader., March 24, 1893, Page 7 | ||

| 1894 | 35 | Policeman | 25 | Tanner | Gloversville City Directory The daily leader., March 14, 1894, Page 8 |

| 1898 | 39 | Chief of Police | The Johnstown daily Republican. December 08, 1898, Page 7 | ||

| 1899 | 40 | Chief of Police | 30 | Policeman | The daily leader., January 04, 1899, Page 5 |

| 1900 | 41 | Chief of Police | 31 | Policeman | U.S. Federal Census |

| 1902 | 43 | Chief of Police | 33 | Policeman | Gloversville City Directory The Johnstown daily Republican. volume, January 07, 1902, Page 6 |

| 1903 | 44 | Chief of Police | 34 | Policeman | Gloversville City Directory The Gloversville daily leader., January 06, 1903, Page 4 |

| 1904 | 45 | Policeman | 35 | Policeman | Gloversville City Directory |

| 1905 | 46 | Policeman | 36 | Policeman | N.Y. State Census |

| 1906 | 47 | Expressman | 37 | Policeman | Gloversville City Directory |

| 1907 | 48 | Expressman | 38 | Glover | Gloversville City Directory |

| 1908 | 49 | Insurance Agent | 39 | Glover | Gloversville City Directory |

| 1912 | 53 | Insurance Agent | 43 | Gloves: Fownes Bros & Co | Gloversville City Directory |

| 1913 | 54 | Insurance Agent | 44 | Gloves: Fownes Bros & Co | Gloversville City Directory |

| 1915 | 57 | Not Stated | 47 | Silker | N.Y. State Census |

| 1917 | 59 | 2nd hand store w/ Guy Sperber | 49 | Gloves: Fownes Bros & Co | Gloversville City Directory |

| 1918 | 60 | Liberty Gas Co | 50 | Gloves: H.G. Hilts & Co | Gloversville City Directory |

| 1919 | 61 | Gloves: Frank P Simmons | 51 | Gloves: H.G. Hilts & Co | Gloversville City Directory |

| 1920 | 63 | Gloves: Littauer Glove Corp | 53 | Gloversville City Directory | |

| 1924 | 64 | Gloves: Littauer Glove Corp | 54 | Gloversville City Directory |

The Sperber Brothers as Policemen

As stated above, John Frederick Sperber was a police officer and, for three years, a Chief of Police in Gloversville, New York between the ages of 30 and 46. His younger brother, Louis P. Speber, was also a policeman for Gloversville between the ages of 31 and 37. They worked together for five years between 1900 and 1905.

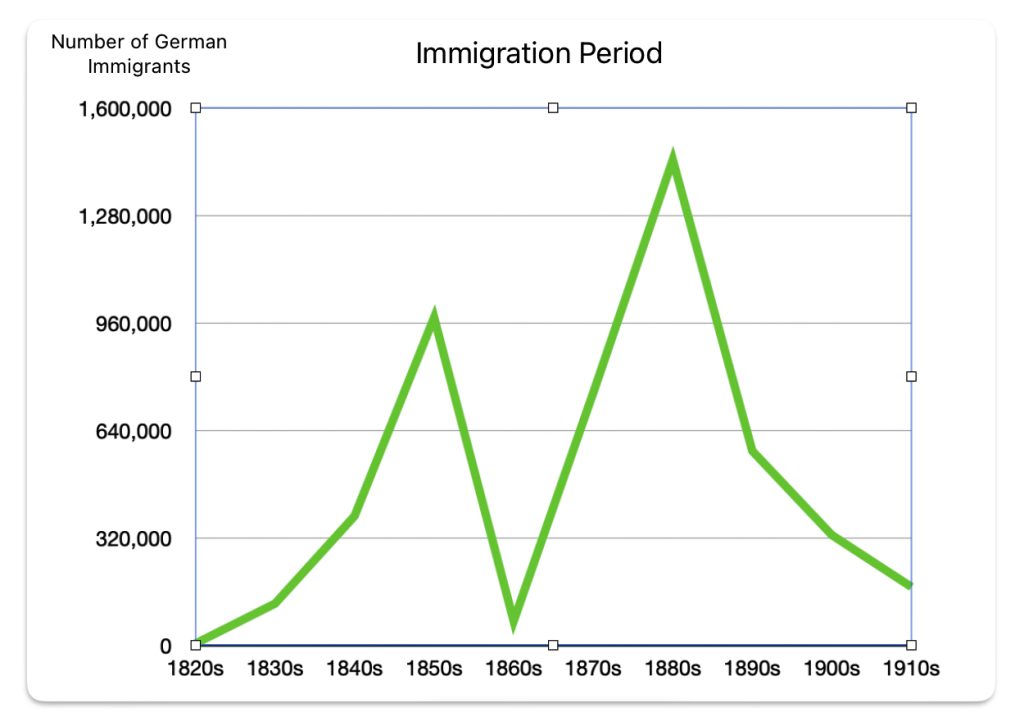

As illustrated in table three, the brother’s employment as law enforcement officers between 1890 and 1906 represented a period of explosive population growth of Gloversville. Within ten years, the population doubled in size by the beginning of 1890. Between 1890 and 1900, the city’s population increased by one third. The growth between 1900 and 1910 slowed a bit but still grew by 12.5 percent.

The expansive growth during this time period undoubtably had an impact on the nature and quality of life within the city. The explosive growth affected the composition and fabric of neighborhoods, and had transformative effects on life experiences of families in the Gloversville area. The focus of the economy began to move from the land more toward the production of goods, specifically tanning, glove making and other industries related to glove and shoe production.

America in general and Gloversville in particular was experiencing massive immigration, and these new comers wanted jobs. People tended to settle in close proximity to where they worked. As a result, new cities formed and already existing cities like Gloversville got much larger.

With this increase in growth, the local police witnessed increased demands in maintaining social order, assisting neighborhoods, and protecting commercial property.

Table Three: Population Growth of Gloversville, New York

| Year | Population | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 7,133 | — |

| 1890 | 13,864 | + 94.4 |

| 1900 | 18,349 | + 32.3 |

| 1910 | 20,642 | + 12.5 |

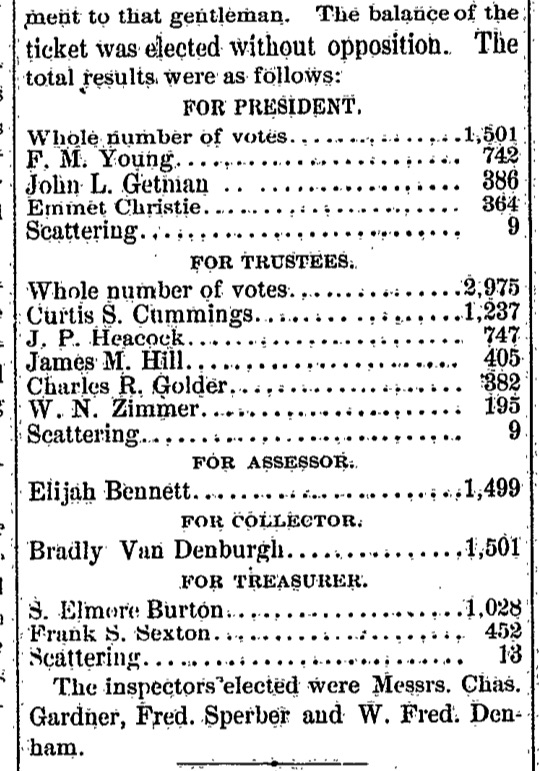

Fred’s initial foray into local government appears to be his successful election as an inspector for the Village of Gloversville on March 3, 1887. It is not known if the job was part time or full time. It is not known what the specific duties of the inspector were in Gloversville. The responsibilities of inspector in Gloversville may have been related to the inspection of ‘nuisances’, similar to the inspector role in England in the mid to late 1800’s. Towns were authorized to appoint an inspector of nuisances. By the end of the century that officer was a fixture in every town, a member of a subordinate profession whose domain, skills and responsibilities were exactly demarcated. [39]

Two years later, Fred Sperber put his hat in the ring to become a police officer in Gloversville. As documented in the local Gloversville newspaper, The Daily Leader, during a Board of Trustees meeting on March 26, 1889, the board voted on the election of three police officers for the village of Gloversville. They first voted for the top two positions. Speber came in third based on the votes. The board then voted for the third and final position, which Fred Sperber garnered the final spot. Fred then began his career as a policeman.

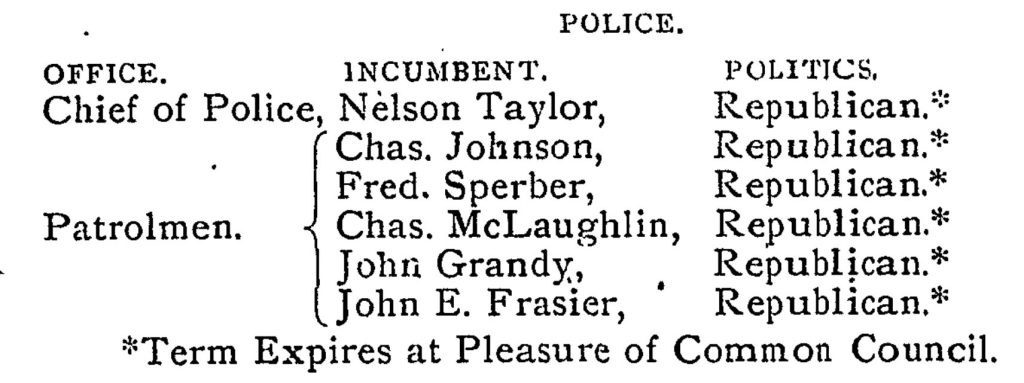

In 1891, the police force was composed of a Police Chief and five officers. These five officers were responsible for patrolling six political wards that had a population of almost 14, 000. As indicated in the newspaper article, the policemen serve at the pleasure of the Common Council. [40]

The following newpaper story records the annual voting for police officers in 1894.

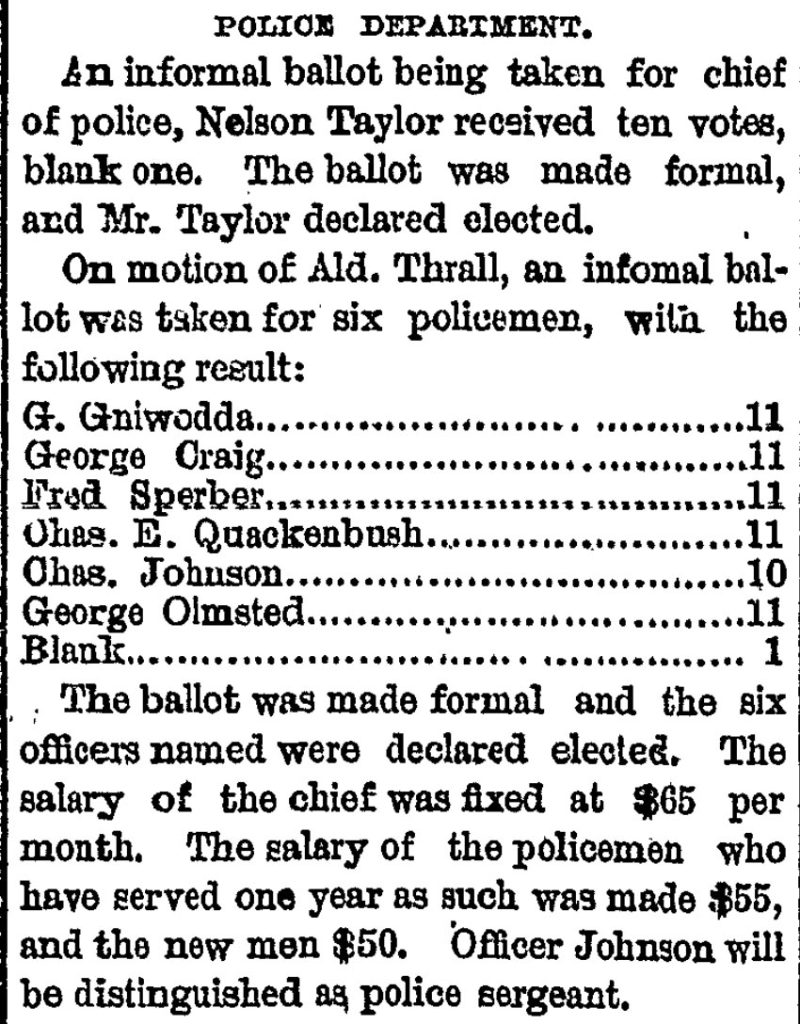

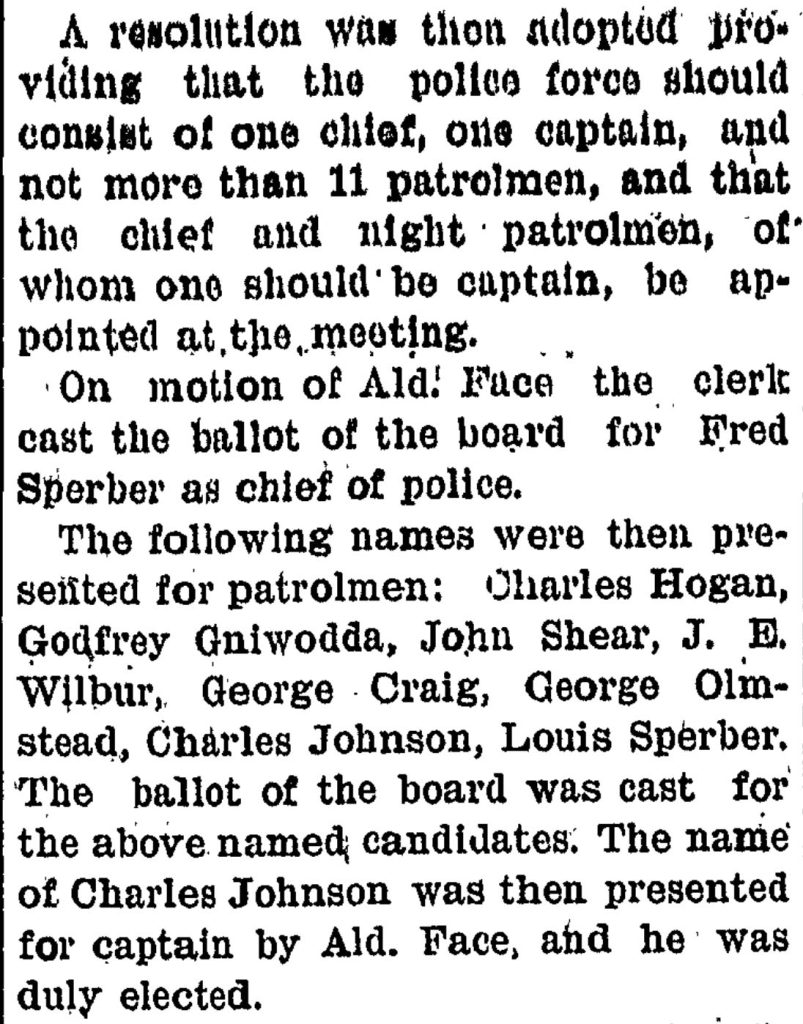

The newspaper article below documented when both brothers were police officers in Gloversville. Fred was elected as Chief of Police and Louis was elected as a police officer in 1899.

The following news article provides a snapshot of Fred Sperber as Chief of Police and his brother, Louis Sperber, as a subordinate police officer. I imagine Fred did not directly supervise his brother since there was a captain and sergeant within the small police force.

Source: The daily leader., March 16, 1899, Page 7; See also The Johnstown daily Republican. volume, March 17, 1899, Page 6

“A telephone message was … sent to Chief Sperber and Officer Louis Sperber went to the warehouse and took the boys to the station house.”

In 1900, Fred Sperber ‘earned’ two stripes, signifying 10 years on the police force.

Fred Sperber was re-elected 11 to 1 as Chief of Police in 1900. His brother Louis was also reappointed as patrolman. The police force consisted of eleven men including the Chief and the Captain.

Perhaps one of many incidents where the two brothers were part of an investigation are documented in a news article in January 1900. .

Source: The Johnstown daily Republican. volume, January 10, 1900, Page 5

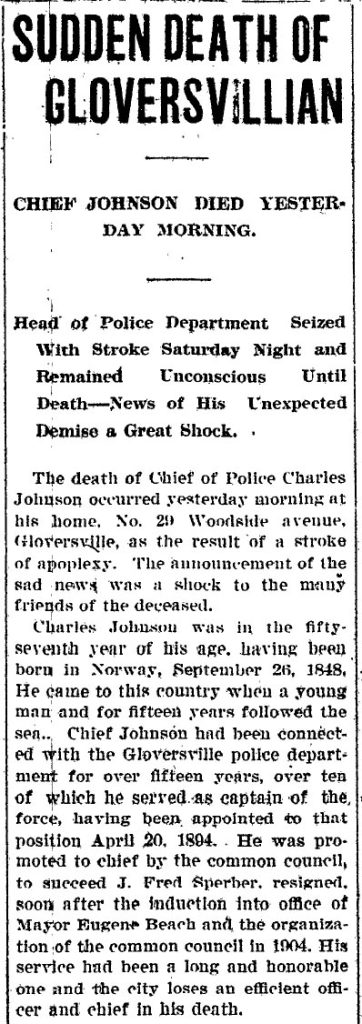

It appears that Fred Sperber continued as the Chief of Police in 1904 despite an initial tie vote by the Gloversville alderman.

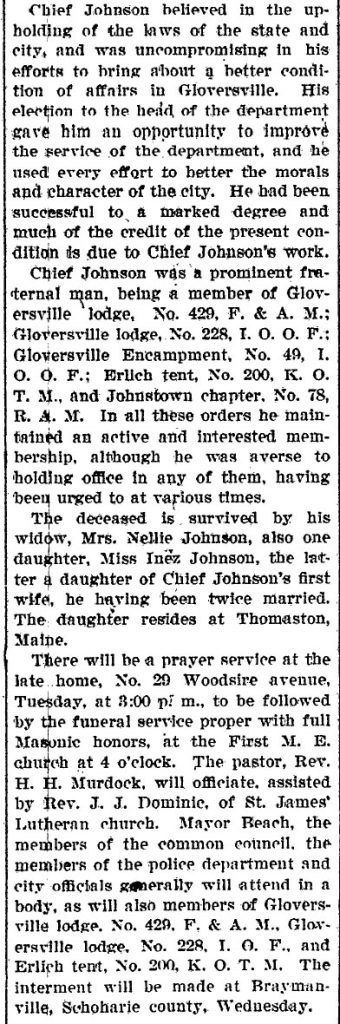

However, with the induction of a new mayor and a new organizational composition of the common council, Fred Sperber was replaced by Johnson in 1904. [41]

Louis Sperber received an additional $5.00 for service over five years during his final year as a policeman.

The work of a policeman at times is never done, even after leaving the role. The following newspaper story indicates the the Gloversville Chief of Police intending to reach out to former policeman Louis Sperber on a murder investigation.

The Sperber Brothers in the Local Newspaper

Many of the arrests and investigations by the brothers were made in all hours of the day and night by the Sperber brothers. I have found 940 newspaper articles on the Sperber brothers as policeman. [42]

“Officer Sperber is a quiet man full of business…”

Source: The daily leader, December 22, 1893, Page

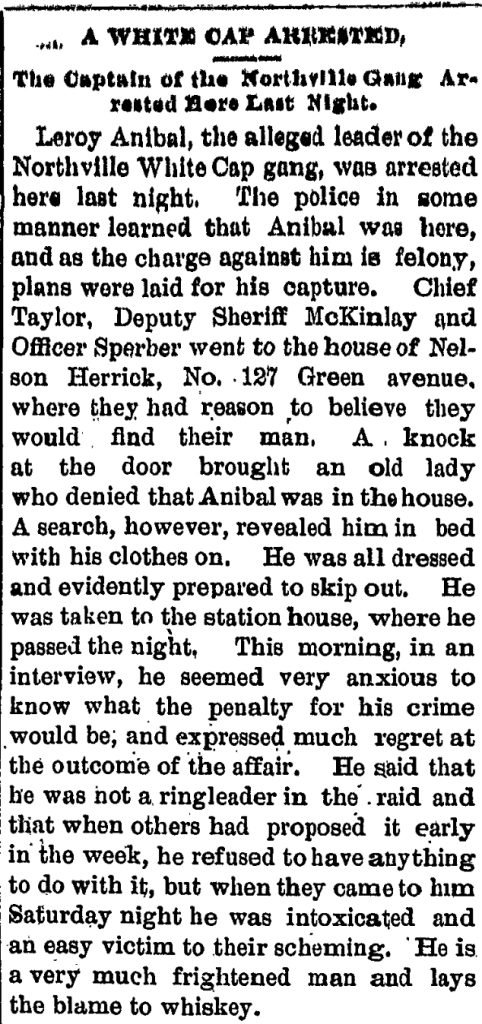

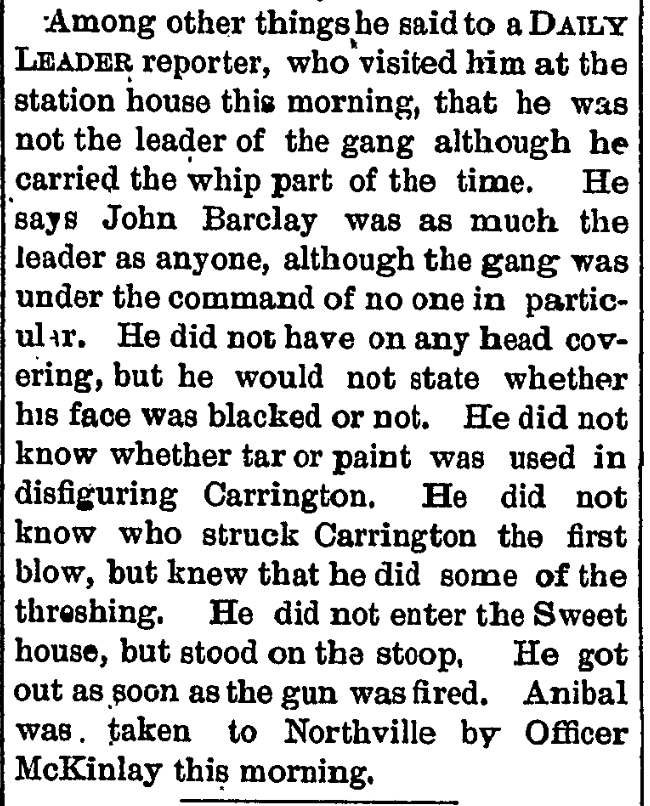

Many of their exploits in law enforcemement were documented in a daily column in the local Gloversville newspaper, The Daily Leader, called: “A Bird’s Eye View“. It is not known who was the writer for this daily column. Whoever wrote this column obviously received daily information from the police and the local judge. The writer also had a unique style of writing and sense of humor in capturing what otherwise were mundane arrests or encounters in Gloversville and made these events a delight to read. Even over one hundred years later, they can evoke a smile and a laugh when reading about these arrests.

The following links are provided if you wish to view specific newspaper articles based on the following subject areas:

Links to Newspaper Articles Based on Topic

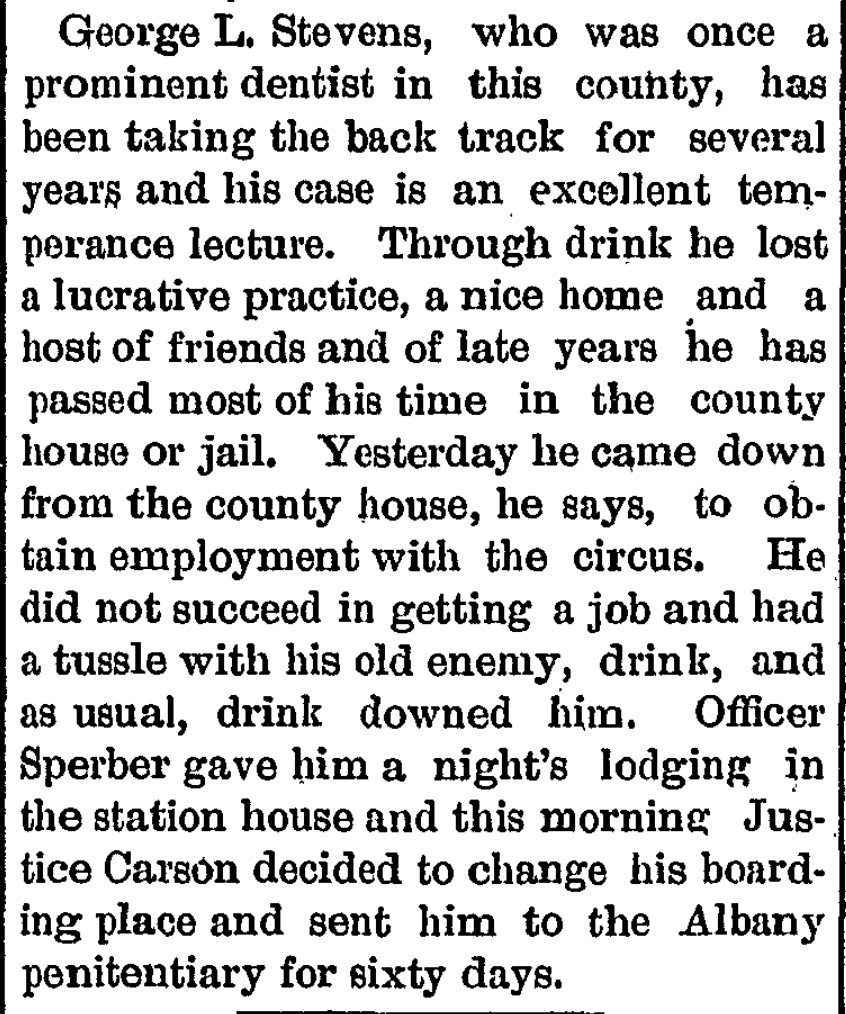

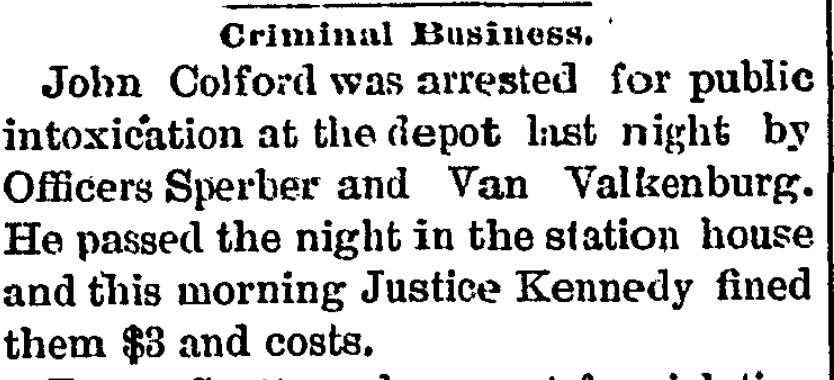

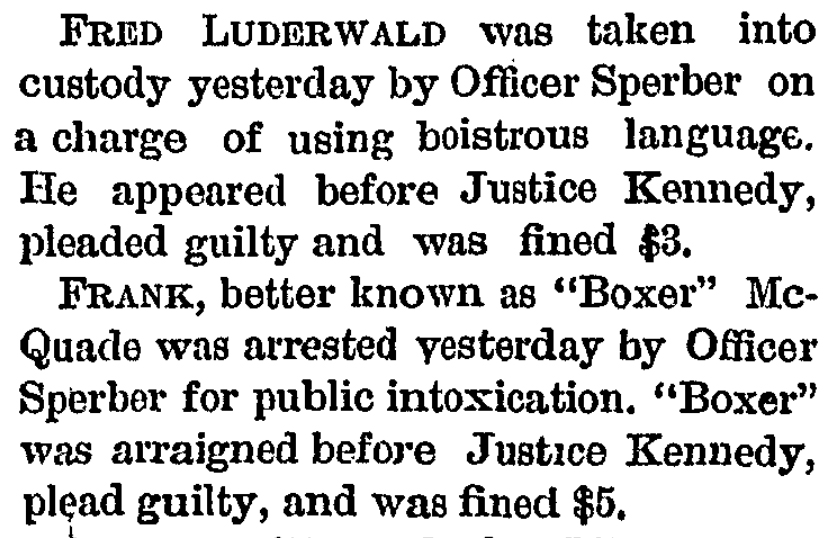

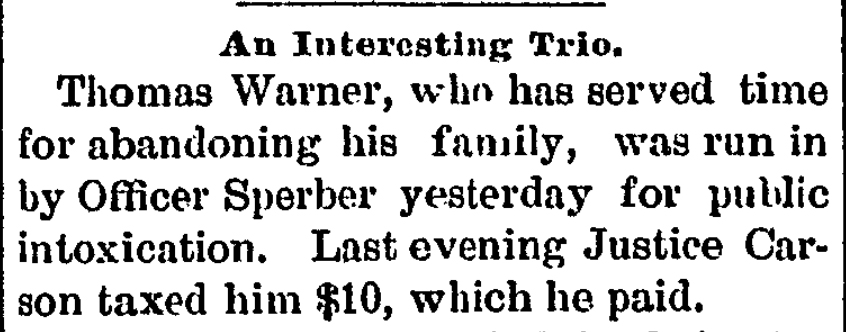

Public Intoxication Arrests

The following newspaper articles capture many of arrests for intoxication by the Sperber brothers. It is not certain in many of the articles as to which brother was making the arrest when both were working in the Gloversville Police Department between 1900 and 1906. When Fred was Chief of Police, it is assumed the arrests were made by Louis Sperber.

Many of the arrests that were documented in the local daily newspaper reflect public intoxication and disorderly conduct arrests. The frequency of these types of arrests were not unusual. In fact, they were the predominate type of arrests throughout the country.

“Beyond serving the interests of politicians, the police were primarily engaged in providing services to citizens. … More than half of all arrests made at this time were for public drunkenness. This was an offense that beat cops could easily discover with no investigation necessary. The police simply did not have the capability to respond to and investigate crimes. When an arrest was made, it was usually as a last resort. Making an arrest in the late 1800s presented some serious logistical difficulties; officers would literally have to “run ’em in” to the police station or, when arresting a drunk, use a wheelbarrow and wheel him into the station. So-called curbside justice with a wooden baton often became an alternate means of dealing with drunken citizens and other law breakers.” [43]

From very early on, the 1840s and the 1850s, the police found themselves involved in endless controversy as a result of the insistence of various local elements that they be used to enforce moral legislation. And the group of issues surrounding liquor sales came to dominate politics in general.

“The sale of alcohol was associated with a host of other popular recreations and vices… and the right to grant or deny such a sale was measured in dollars as well as other forms of power. Shifting coalitions of Catholics and Protestants, Irishman, natives, and Germans, Republicans and Democrats, state legislators, and city councilmen enacted a variety of policies ranging from absolute prohibition to nearly free license.”

“But ultimate responsibility came always to rest on the police, who might enforce these regulations strictly, selectively, or not al all. The inevitable results – shakedown and shake -up, cyclical waves of protest – made this aspect of police work a matter of chronic tension.”[44]

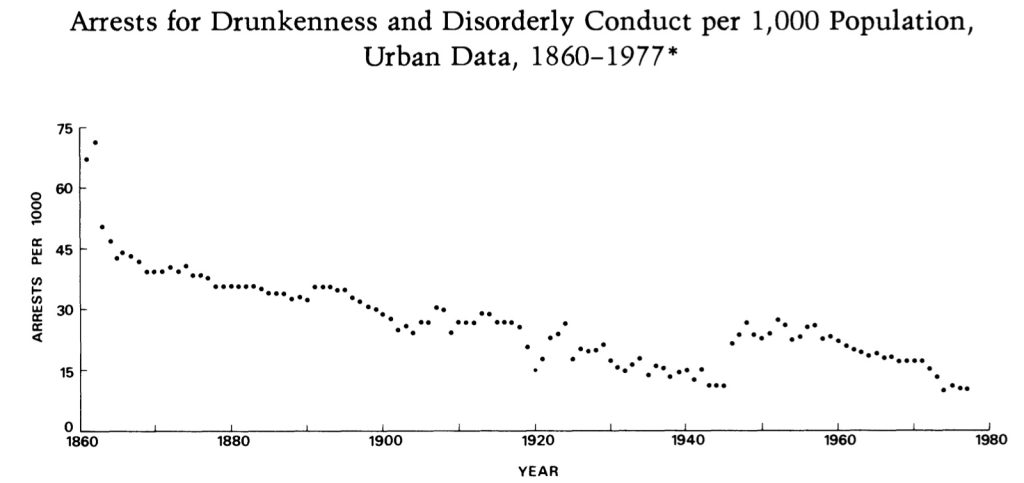

As reflected in the chart below, which is part of in an historical study by Eric Monkkonen on arrests for drunkenness and disorderly conduct [45] , such arrests were more prominent in the mid to late 1800’s. The downward arrest trend allows for several inferences of broader implication than the simple, and important, observation that police have for over a century been making fewer and fewer ‘catchall arrests’. Given that the prime mover in creating the data was the police, one can only speculate about the probable social meanings of the trends. However, I wish to only convey that the preoccupation of the Sperber brothers arresting individuals for such behvior is consistent with the over all trends found when they were working as policeman.

“Let us first consider a nineteenth-century police officer’s decision to arrest and take into custody a drunk or disorderly person, examining the differences between the nineteenth century and the mid-twentieth century. Prior to the last two decades of the nineteenth century, one of the most difficult parts of the arrest process, from both the officer’s and arrestee’s perspective, was the period between the arrest and booking in the station house. Before a city had both an electronic communications system and a wagon to haul in the arrested person, the officer and the arrestee had to walk or take public transportation to the station house. Even toward the end of the century, after most cities obtained some form of electronic communication, the officer and the arrestee had to walk to a call box, signal in the request, and wait for a horse-drawn wagon to come from the station house. Until the wagon arrived, the officer and the arrestee were, at best, alone; more often, they were surrounded by curious onlookers or, worse for the officer, the arrestee’s friends. In all cases the arrest involved physical contact and struggle in public: the officer had to be sure of his ability to control the arrestee.” [46]

Many of the news stories were part of a daily column called “The Bird’s Eye View: Of the Thriving Metropolis of Fulton County”.

“…he came down from the county house, he says, to obtain employment with the circus. He did not succeed in getting a job and had a tussle with his old enemy, drink, and as usual, drink downed him.”

“…better known as ‘Boxer’ McQuade was arrested yesterday by Officer Sperber for public intoxication.”

“George Lockwood was also full of fire water last night. officer Speber took him to the cooler.”

“A man who will sell liquor to be drank on his premises by a boy only 15 years of age (say nothing about his company who were possibly a couple of years older) ought not to be allowed the privilege of selling liquor at all. “

“The stench that hovered about him would lead one to believe that he had a very aged load on. Justice Carlson evidently concluded that one fine was enough for one toot and sentence was suspended.”

“He was asked whether he would like to go to jail again and said he would not whereupon he was sentenced to ninety days in the Albany penitentiary. When he was arrested last evening it was found necessary top take him to the station house in a wagon.”

Arrests for Disorderly Conduct & Resisting Arrest

“Michael Delany, better known as “Jenny Lind”, a long haired individual who frequently indulges in the cup that intoxicates, was on a rampage last night.”

Arrests and Assists for Stolen Property

“John Marlette was arrested at an early hour this morning by Office Sperber , who discovered that character with couple of unknown chickens under his coat. The owner of the chickens was hunted up while John took up his bed in the station house.”

“Guy Hopkins, a young lad about nine years of age, was arrested last night, chaged with a crime, and when confronted with facts, made a confession.

Chief of Police Sperber has been working on the case for some time…

Calls for Assistance

Protection of Commercial Property

Officer Sperber got in some heavy work on the big bell and in short time a stream was ready.

Officer Sperber and Constable Clark were prowling about among the cars in the freight yard when they saw a light under the freight office…

… followed by a crowd of at least 200 men and boys…

Transporting Prisoners

Arrests for Violent Crime

“The prisoners were shacked together and attracted considerable attention, as they passed down Main Street to the car in charge of Officers Sperber and Olmsted, who took them to Albany. “

Arrests Related to Gang Behavior

Investigation of Death

Louis Sperber was one of the Police Officers investigating the death.

“Night’s Debauch Ends in Death”, The Johnstown Daily Republican. January 22, 1906, Page 5, See PDF of the news story,

See also “Night’s Debauch Ends in Death, The Johnstown Daily Republican. volume, January 22, 1906, Page 5, See PDF of the news story,

Enforcement of City Ordinances

Additional Page on:

Aside from the legal offenses of disorderly conduct, drunkenness, stolen property, theft, vandalism, and violent crime, the Sperber brothers were also responsble for the enforcement of city ordinances.

Fugitive Investigator

There are a number of newspaper articles reflecting the Sperber brothers’ official efforts as fugitive investigators, ranging from theft, murder, and violent crime. There are also many news accounts of their efforts to simply locate individuals for lessor offenses such as the one below.

Federal Witness

“The witnesses present from Gloversville were Chief of Police Taylor. Officers Sperber and Johnson, and three newsboys … who had received spurious ten cent pieces from Mrs. Johnson, at various times.”

Fred Sperber as Police Chief

In addition to the added complexities of maintaining and navigating relationships with the mayor, the city alderman, various local businesses and neighborhoods, Fred Sperber also had the inherent challenges of managing a police force as the chief of police.

The following newspaper article touches on the influence of local business and the practical allocation of law enforcement resources to the enforcement of local ordinances. Evidently there were concerns about individuals coming into the city and selling clothing. Chief Sperber made it be known via the press, that he had the local business interests in mind when managing his limited resources.

Another example of political influence and business interests on the management of the police force is reflected in the following news article on gambling establishments.

As a Chief of Police, Fred Sperber was involved in many major criminal investigations in the city. One example is Chief Sperber’s involvement in investigating the fire in a major shoe tannery. The fire was caused by a prominent Gloversville businessman who was associated with a rival business and resulted in his death.

The incident made front page news. The presumption was that a fatally injured man, John Kennedy, a prominent businessman of Kennedy & Co, was trying to obtain a secret process for dressing shoe leather, known only to a competitor, the Mills Bros, and believed that by obtaining some of the packages in the Mills Bros. building and some of the camphene it would be possible to reproduce the same kind of leather. The man who was inside the building when an explosion occurred probably had the packages in his hands and, believing he had the secrets of the process, hung onto the packages despite the fact that he was being burned to death. It is presumed that his brother Daniel Kennedy helped his brother flee to his father’s house where he was treated by a doctor but subsequently died from his burns.

See PDF version of the newspaper article

“Coroner Palmer, District Attorney Egelston and Chief Sperber have worked diligently to get all of the facts in connection with the matter and will do their best to solve it.”

Source: The Gloversville daily leader., May 25, 1903, Page 1 |

See PDF version of newspaper article

“As a result of evidence now in possession of Chief Sperber and District Attorney Egelston and Coroner Palmer, it has been decided to present the case of Daniel Kennedy to the grand jury which will meet in Johnstown next week….”

Source: The Gloversville daily leader., May 28, 1903, Page 8, |

Working with the mayor and the city alderman was a major, continuous challenge. Chief Sperber was required to balance his perceptions of civic duty with the views of each alderman, the mayor, influences of local business establishments and the general citizenry. The following newspaper article reflects the “political tussles” between the city aldermen and Chief Sperber’s occational insertion between warring alderman.

See PDF version of the newspaper article

“Never has a meeting of the board of aldermen been … filled with such an amount of personal abuse and vituperation and never has a meeting of the board come so near culminating in a riot. “

Source: The Gloversville daily leader., April 28, 1903, Page 5 |

While Chief Fred Sperber endured verbal attacks and political heat and pressure, he also received occasional accolades for his work. His planning and coordination during a fireman’s convention in Gloversville received high marks.

“Chief Sperber is entitled to considerable credit for the protection he provided for the town. “

Even as a Chief of Police in a town with over 18,000 inhabitants, Fred Sperber continued to be involved in low level cases that had a ‘human element’ concerned with typical family matters. The following article portrays an incident that probably happened in many small towns in America. Although, taking $20 from your parents in 1899 was a lot of money!.

The following newspaper account chronicles the culmination of a festering relationship between Chief Sperber and one of his officers. Chief Sperber brought charges against a long time colleague and subordinate William Nichols. The charges resulted in the city’s common council conducting a “court martial” hearing that the public was allowed to attend. Nichols was acquitted but required to provide a formal apology to the mayor and Chief Sperber before he was able to be reinstated as a policeman.

Click for larger view of News Article Below

Click for larger view of News Article Below

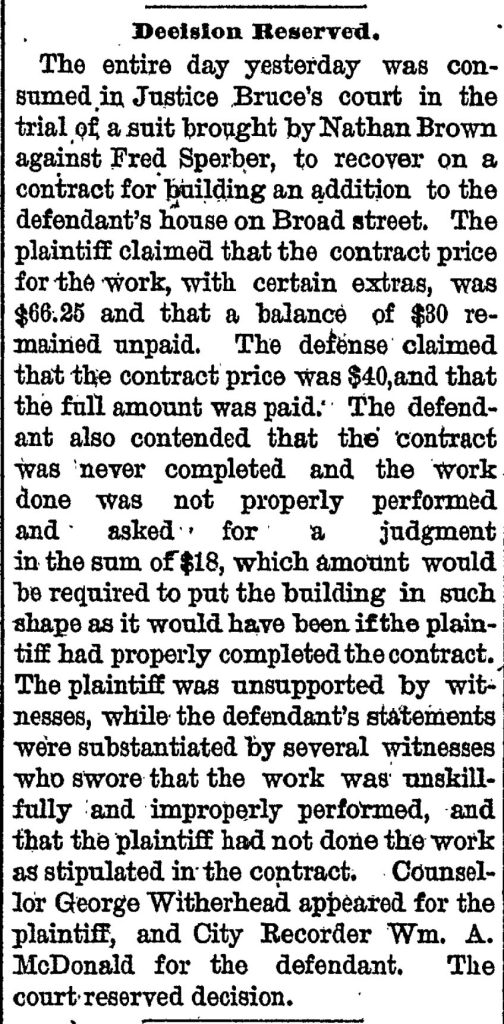

As a defendant

Even though they were policemen, they too had their time in court. A suit was raised against Fred Sperber for allegedly not paying the agreed upon price for home renovations. Fred’s experience in court preparation proved to be very helpful.

“The plaintiff was unsupported by witnesses, while the defendant’s statements were substantiated by several witnesses who swore the work was unskillfully and improperly performed, and that the plaintiff had not done the work as stipulated in the contract.”

Sources

Feature Photograph: Frederick Sperber’s Blackjack. The wooden Blackjack Slap Jack (American English), or cosh (British English), is a small, easily concealed club. Frederick’s black wooden blackjack may have had a leather strap when he used it as a policeman. When directed at the head, it works by concussing the brain without cutting the scalp. This is meant to stun or knock out the subject, although head strikes from blackjacks are regularly fatal. It can also be used to jab an individual. Blackjacks were popular among law enforcement for a time due to their low profile, small size, and their suitability for knocking a suspect unconscious or inflicting non-deadly force..

Baton (law enforcement), Wikipedia, page accessed 15 May 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baton_(law_enforcement)

Massad Ayoob, Fundamentals of Modern Police Impact Weapons, Springfield: Charles C Thomas, 1978, Pages 11-18 https://archive.org/details/Fundamentals_of_Modern_Police_Impact_Weapons_Massad_Ayoob/page/n1/mode/2up

“blackjack | Origin and meaning of blackjack by Online Etymology Dictionary”. etymonline.com. Retrieved 30 March 2018. The hand-weapon so called from 1889

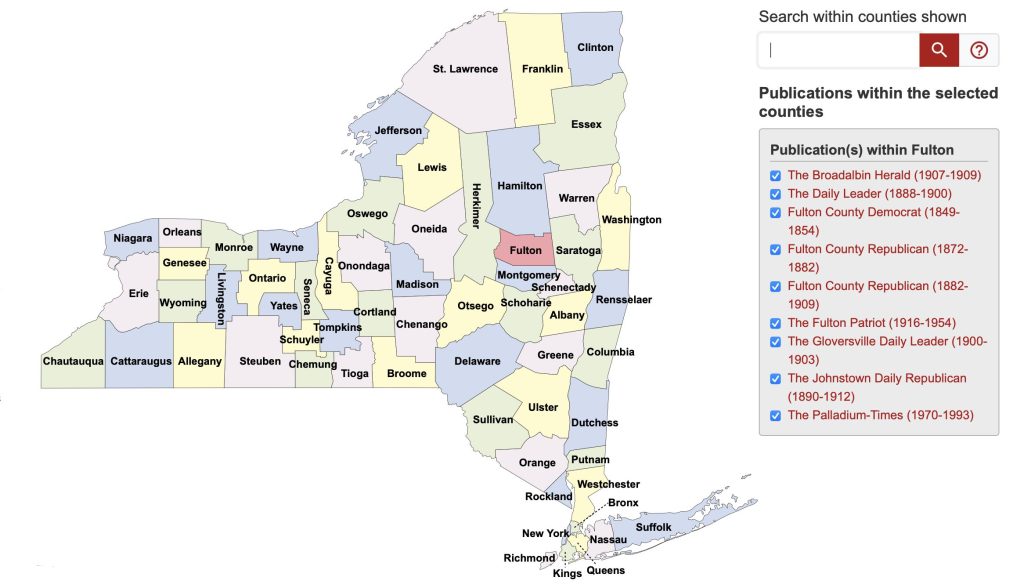

The historical newspaper sources found in this story are principally from The New York State (NYS) Historic Newspapers project. The New York Historic Newspapers project exists to digitize and make freely available for research significant runs of historic newspapers for every county in the state. It is an amazing source for historical research and their search engine is very robust in terms of its search capabilities.

This is created and administered by the Northern New York Library Network in partnership with the Empire State Library Network.

Virtually all of the news stories are from three local newspapers:

- The Daily Leader (1888-1900) ;

- The Gloversville Daily Leader (1900-1903); and the

- The Johnstown Daily Republican (1890-1912)

Just after I published this story, the NYS Historic Newspaper project revamped their entire website. The original architecture of the website provided persistent links to pages in specific newspapers. It is not apparent that these links are currently available. If you wish to locate the original page of the newspaper articles that are referenced in this story, it is suggested that you copy the source listed and go to the following page: https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=p&p=countybrowser&county=Fulton&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN———- , then ‘paste’ the copied reference in the search box.

[1] From “A Bird’s Eye View Daily Column” in the Gloversville Daily Leader., April 06, 1889, Page 3

[2] Spitzer, Stephen, “The Rationalization of Crime Control in Capitalist Society,” Contemporary Crises 3, no. 1 (1979).

Gaines, Larry. Victor Kappeler, and Joseph Vaughn, Policing in America (3rd ed.), Cincinnati, Ohio: Anderson Publishing Company, 1999.

Harring, Sidney, Policing in a Class Society: The Experience of American Cities, 1865-1915, New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1983.

Lundman, Robert J., Police and Policing: an Introduction, New York, New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1980.

Lynch, Michael, Class Based Justice: A History of the Origins of Policing in Albany, Albany, New York: Michael J. Hindelang Criminal Research Justice Center, 1984.

Reichel, Philip L., “The Misplaced Emphasis on Urbanization in Police Development,” Policing and Society 3 no. 1 (1992).

Spitzer, Stephen, “The Rationalization of Crime Control in Capitalist Society,” Contemporary Crises 3, no. 1 (1979).

Spitzer, Stephen and Andrew Scull, “Privatization and Capitalist Development: The Case of the Private Police,” Social Problems 25, no. 1 (1977).

Walker, Samuel, The Police in America: An Introduction, New York, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996.

The First American Police Departments: The Political Era of Policing, Sage Publications, 2021, https://us.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-assets/109011_book_item_109011.pdf

[3] Olivia B Waxman, How the U.S. Got Its Police Force, Time, May 18, 2017, https://time.com/4779112/police-history-origins/

The First American Police Departments: The Political Era of Policing, Sage Publications, 2021, https://us.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-assets/109011_book_item_109011.pdf

The History of Police Sage Publications, https://www.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/50819_ch_1.pdf

[4] The Annual Report Submitted by Chief Sperber, The daily leader., January 30, 1900, Page 8,

[5] The Annual Report Submitted by Chief Sperber, The daily leader., January 30, 1900, Page 8,

[6] Ibid

[7] Joe Blundo, Early bikes sparked same fears in 19th century that scooters do today, Sep 8, 2019, The Columbus Dispatch, https://www.dispatch.com/story/lifestyle/2018/09/08/early-bikes-sparked-same-fears/10812113007/

[8] Safety Bicycle, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 1 June 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Safety_bicycle

David Herlihy, David V. (2004). Bicycle: the History. Yale University Press. 1980, pp. 216–217. In 1876, the British engineer Henry J. Lawson proposed a new rear-drive machine he called the Safety Bicycle.

Joe Blundo, Early bikes sparked same fears in 19th century that scooters do today, Sep 8, 2019, The Columbus Dispatch, https://www.dispatch.com/story/lifestyle/2018/09/08/early-bikes-sparked-same-fears/10812113007/

Diane Budd’s, How bicycles ignited 200 years of controversy in New York City, Mar 14, 2019, Curbed New York, https://ny.curbed.com/2019/3/14/18264413/cycling-in-the-city-museum-of-the-city-of-new-york-mcny

History of the bicycle, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 29 June 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_bicycle

James Longhurst, Bike Battles: A History of Sharing the American Road, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017

James Longhurst, Bike Battles: A History of Sharing the American Road, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017

Jesse Gant, Podcasts, Bike Battles: A Conversation on the Road with James Longhurst, , Edgeffects Oct 12, 2019, https://edgeeffects.net/bike-battles/

Robert Loerzel, In 1890s Chicago, bicycles were all the rage, Chicago Tribune, May 14, 2014, https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-bicycle-craze-flashback-0427-20140503-story.html

Michael Taylor. “The Bicycle Boom and the Bicycle Bloc: Cycling and Politics in the 1890s.” Indiana Magazine of History 104, no. 3 (2008): 213–40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27792904.

Rubinstein, David. “Cycling in the 1890s.” Victorian Studies 21, no. 1 (1977): 47–71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3825934.

Photograph: Clarence L. Winter, Bicycle Riding, 1890s Style – circa 1895, cabinet car, 3.9 x 5.5 inches, Eugene, Oregon. https://www.oldoregonphotos.com/bicycle-riding-1890s-style-circa-1895.html

[9] The Johnstown daily Republican. volume, July 15, 1899, Page 5,

See also: What the City Can Do, The Collins Law Permits certain Local Bicycle Legislation , The Johnstown daily Republican. volume, June 19, 1899, Page 6,

This article points out that the law provides for the ability for municipalities, towns, cities, and villages to pass cycle ordinances to conform to the following:

- Require cyclists to carry a light to be seen 200 feet ahead and to be kept lighted between one hour after sunset and one hour before sunrise;

- Require the use of an alarm bell or signal which can be heard 100 feet distant and used when approaching people or vehicles;

- Prohibit coasting , the carrying of children under five years of age on the bicycles, observance of road rules established by highway law;

- To permit the granting of permits to persons to ride during specified portions of streets at any rate of speed; and

- To provide the establishment of violations to be punished by a fine not exceeding $5 and in case of non payment.

See also:

There can be no question now as to the rights and duties of wheelmen, The daily leader., June 29, 1899, Page 8,

Considers himself aggrieved, The daily leader., June 23, 1899, Page 7,

Stringent ordinances adopted at last night’s meeting, The Johnstown daily Republican. volume, July 26, 1899, Page 3

[10] The bicycle “scorchers” menacing the 1890s city, Ephemeral New York, blog, August 9, 2014, https://ephemeralnewyork.wordpress.com/2014/08/09/the-bicycle-scorchers-menacing-the-1890s-city/

Steve Hoffbeck, Bicycles Scorcher, Prairie Public NewsRoom, July 26 2010, https://news.prairiepublic.org/show/dakota-datebook-archive/2022-05-22/bicycles-scorchers

[11] The Gloversville daily leader., May 03, 1900, Page 8,

[12] Keeping a Disorderly House, The daily leader., August 09, 1894, Page 7,

[13] The original incident involved the death of a women found at a saloon. No place for Women: Police Demand that Admittance to Saloons be Denied to Them, The Gloversville daily leader., March 26, 1902, Page 8,

[14] The backlash from saloon owners can be found in: Women and the Saloon: Police are Keeping Strict Watch to see that the Law is Obeyed”,, The Gloversville daily leader., May 24, 1902, Page 5,

[15] Gary Potter, The History of Policing in the United States, Academia, https://www.academia.edu/30504361/The_History_of_Policing_in_the_United_States

Jill Lepore, The Invention of the Police, The New Yorker, July 13 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/07/20/the-invention-of-the-police9

Gaines, Larry. Victor Kappeler, and Joseph Vaughn, Policing in America (3rd ed.), Cincinnati, Ohio: Anderson Publishing Company, 1999.

Watchman (law enforcement), Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 1 August 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watchman_(law_enforcement)

[16] The Daily Leader, Gloversville, April 24, 1890, Page 4,

[17] Ibid

[18] Stephen Estes, Civil Service in New York State, Aug 11, 2008, Tompkins County, New York, https://tompkinscountyny.gov/files2/personnel/CIVIL%20SERVICE%20IN%20NEW%20YORK%20STATE%20HISTORY%20AND%20OVERVIEW.pdf

[19] Constitution of the State of New York Art. V § 6. [Civil service appointments and promotions; veterans’ preference and credits], Find Law, https://codes.findlaw.com/ny/constitution-of-the-state-of-new-york/ny-const-art-5-sect-6/

[20] Stephen Estes, Civil Service in New York State, Aug 11, 2008, Tompkins County, New York, https://tompkinscountyny.gov/files2/personnel/CIVIL%20SERVICE%20IN%20NEW%20YORK%20STATE%20HISTORY%20AND%20OVERVIEW.pdf

Civil Service in NYS, History of Civil Service in New York State, Cort;and County, New York, https://www.cortland-co.org/702/Civil-Service-in-NYS

[21] Sperber Elected as Police Officer 1891 and Salary Specified, The daily leader., March 24, 1891, Page 8,

[22] $1 in 1891 is worth $33.59 today, CPI Inflation calculator, https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1891?amount=1

[23] Stephen Estes, Civil Service in New York State, Aug 11, 2008, Tompkins County, New York, https://tompkinscountyny.gov/files2/personnel/CIVIL%20SERVICE%20IN%20NEW%20YORK%20STATE%20HISTORY%20AND%20OVERVIEW.pdf

[24] The daily leader., February 28, 1891, Page 2 & 3 , | Click For Larger View | Click for PDF view that allows magnification of image

[25] The daily leader., April 03, 1889, Page 3 |

[26] 1900 U.S. Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Gloversville Ward 02, District 9, Page 106, Line 30.

1910 United States Census, New York, Fulton County, Gloversville Ward 2, District 0012, Page 1B, Line 70

1920 U. S. Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Gloversville Ward 2, District 12, Page 8A, Line 2

1930 U.S. Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Gloversville, District 11, Page 8B, Line 61

[27] U.S., Indexed County Land Ownership Maps, 1860-1918, Collection Number: G&M_9; Roll Number: 9; County and Year: Montgomery and Fulton, 1905, Page 88

Ancestry.com. U.S., Indexed County Land Ownership Maps, 1860-1918 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Various publishers of County Land Ownership Atlases. Microfilmed by the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. This database contains approximately 1,200 U.S. county land ownership atlases from the Library of Congress’ Geography and Maps division, covering the approximate years 1864-1918.

[28] 1880; Census Place: Gloversville, Fulton, New York; Roll: 834; Page: 95A; Enumeration District: 006, Line 22

[29] Ella Aucock, 1880 U.S. Federal Census; Gloversville, Fulton, New York; Roll: 834; Page: 111B; Enumeration District: 006, Page 34, Line 33;

[30] New York Department of Health; Albany, NY; NY State Death Index, 1936, certificate number 42474, P 1118

J. Frederick Sperber, Find A Grave, Prospect Hill Cemetery, Section 4 memorial ID: 114579434 Age 76, funeral was on July 7, 1936, cause of death: apoplexy, undertaker: Rogers & Young, Gloversville, New York, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/114579434/j-fred-sperber

[31] Birth of Marguerita Sperber, August 5, 1984, New York State Department of Health; Albany, NY, USA; New York State Birth Index, 1984, Page 814

Death of Marguerita Sperber, 8 Apr 1895 (aged 8 months), Burial: Gloversville, Fulton County, New York, Prospect Hill Cemetery Gloversville, Fulton County, New York, USA MEMORIAL ID158848379 · View Source, Fina A Grave https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/158848379/marguerita-sperber

[32] Residences of Louis P. Sperber as documented in the Gloversville City Directories and Federal and New York State census:

- Gloversville City Directory, 1895, Louis P. Sperber, 3 Woodside Ave, Page 165

- Gloversville City Directory, 1902, Louis P. Sperber, 12 Washington Street, Page 195

- Gloversville City Directory, 1903, Louis P. Sperber, 18 Spring Street, 201

- Gloversville City Directory, 1904, Lois P. Sperber, 32 Elm Street, Page 182

- Gloversville City Directory, 1909, Louis P. Sperber, 25 S. School, Page 334

- Gloversville City Directory, 1912, Louis P. Sperber, 25 S School, Page 307

Gloversville City Directory, 1880, Page 155, Online source: ancestry.com. U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com

Louis Sperber, 1900 United States Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Gloversville Ward 01, District 7, Page 15, Line 34

Marriage to Rose Clancey, 5, 28, 1913, New York State Marriage Index 1913, marriage certificate number 10165, Page 6164.

Gloversville, New York, City Directory, 1890 Source : Ancestry.com. U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original sources vary according to directory. The title of the specific directory being viewed is listed at the top of the image viewer page. Check the directory title page image for full title and publication information.

Louis Sperber, 1900 Federal Census, Gloversville Ward 1, Fulton, New York; Roll: 1036; Page: 16; Enumeration District: 0007, Sheet No. 16, Lines 34-36

1903 Gloversville, New York, City Directory, 1903, Ancestry.com. U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original sources vary according to directory. This database is a collection of city directories for various years and cities in the U.S. Generally a city directory will contain an alphabetical list of its citizens, listing the names of the heads of households, their addresses, and occupational information.

[33] New York State Marriage Index, 1913, page 6164, May 28, 1913, certificate number 10165.

[34] Louis P. Sperber, New York Department of Health; Albany, NY; NY State Death Index, 1920 certificate number 54031

Louis P. Sperber, Find A Grave, Prospect Hill cemetery, memorial ID 158848240, Section 8, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/158848240/louis-p.-sperber

Louis P. Sperber, a life-long resident of Gloversville, died at his home following a lingering illness. Louis was the son of John W. and Sophia (Fliegel) Sperber. Louis was first married to Anna Sprung. After her death, he married Rose Clancy. He was a leather worker, a former member of the police force and a member of the Republican City committee from the third district of the sixth word.

Besides his wife, Rose, he is survived by one brother, former Police Chief Fred Sperber, of Gloversville: three sisters, Rose Knopf of Brooklyn, Catherine Sperber and Ida M Griffis of Gloversville; one niece, Mrs. Rose Jennison of Rural Grove and four nephews.

[35] Expressman, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 24 May 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expressman#:~:text=The%20expressman%20served%20not%20only,considered%20a%20highly%20valuable%20employee.

Alexander Lovett Stimson, History of the Express Business, New York: Baker & Godwin, Printers 1881 https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_of_the_Express_Companies/JwJd5duDscIC?hl=en

T.W. Tucker, Waifs from the Way-Bills of an Old Expressman, Boston: Lee and Shepard Publishers, 1891, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Waifs_from_the_Way_bills_of_an_Old_Expre/PHBCAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Tucker,+T.W.+(1891).+Waifs+from+the+Way-Bills.+Lee+%26+Shepard+Publishers&pg=PA1&printsec=frontcover

Allan Pinkerton, The Expressman and the Detective, Chicago: W.B. Keen, Cooke & Co., 1874, https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Expressman_and_the_Detective/CEM7AAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

[36] Twelfth Census of the United States, Census Bulletin No. 175, Washington D.C. May 24, 1902, Manufactures: Gloves and Mittens – Leather, Page 10 https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1900/bulletins/manufacturing/175-manufactures-gloves-mittens-leather.pdf

[37] Duties of the U.S. Marshal can be found at: https://www.usmarshals.gov. Specifically Fred Sperber was responsible for fugitive investigations, protecting the city judge, escorting arrested individuals and sentenced prisoners on behalf of the court, and transporting sentenced prisoners.

[38] Sperber designated as a truant officer in addition to police duties, The daily leader., February 06, 1896, Page 4,

Worth of dollar in 1886, https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1886

“$1 in 1886 is equivalent in purchasing power to about $32.52 today, an increase of $31.52 over 137 years. The dollar had an average inflation rate of 2.57% per year between 1886 and today, producing a cumulative price increase of 3,152.03%.”

- CPI Inflation Indicator, https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1886?amount=1#:~:text=Value%20of%20%241%20from%201886,cumulative%20price%20increase%20of%203%2C152.03%25.

[39] Hamlin, Christopher. “Nuisances and Community in Mid-Victorian England: The Attractions of Inspection.” Social History, vol. 38, no. 3, 2013, pp. 346–79. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24246600. Accessed 19 Aug. 2023

[40] The daily leader., April 02, 1891, Page 6,

[41] The Johnstown Daily Republican. volume, July 24, 1905, Page 541

[42] All of the newspaper stories of the Sperber brothers were found at the NYS Historic Newspapers website. Since its launch in 2014, New York State Historic Newspapers has provided free access to a wide range of newspapers chosen to reflect New York’s unique history. This now includes 920 titles from all 62 counties comprising over 11.7 million pages of historical content. https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org

[43] The History of Police in America, Sage Publications, Inc. Page 25, https://us.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-assets/109011_book_item_109011.pdf

[44] Lane, Roger. “Urban Police and Crime in Nineteenth-Century America.” Crime and Justice 15 (1992): 1–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1147616. Page 10

Monkkonen, Eric H. “The Organized Response to Crime in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century America.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 14, no. 1, 1983, pp. 113–28. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/203519.

[45] Monkkonen, Eric H. “A Disorderly People? Urban Order in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.” The Journal of American History, vol. 68, no. 3, 1981, pp. 539–59. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1901938. Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[46] Ibid, page 542