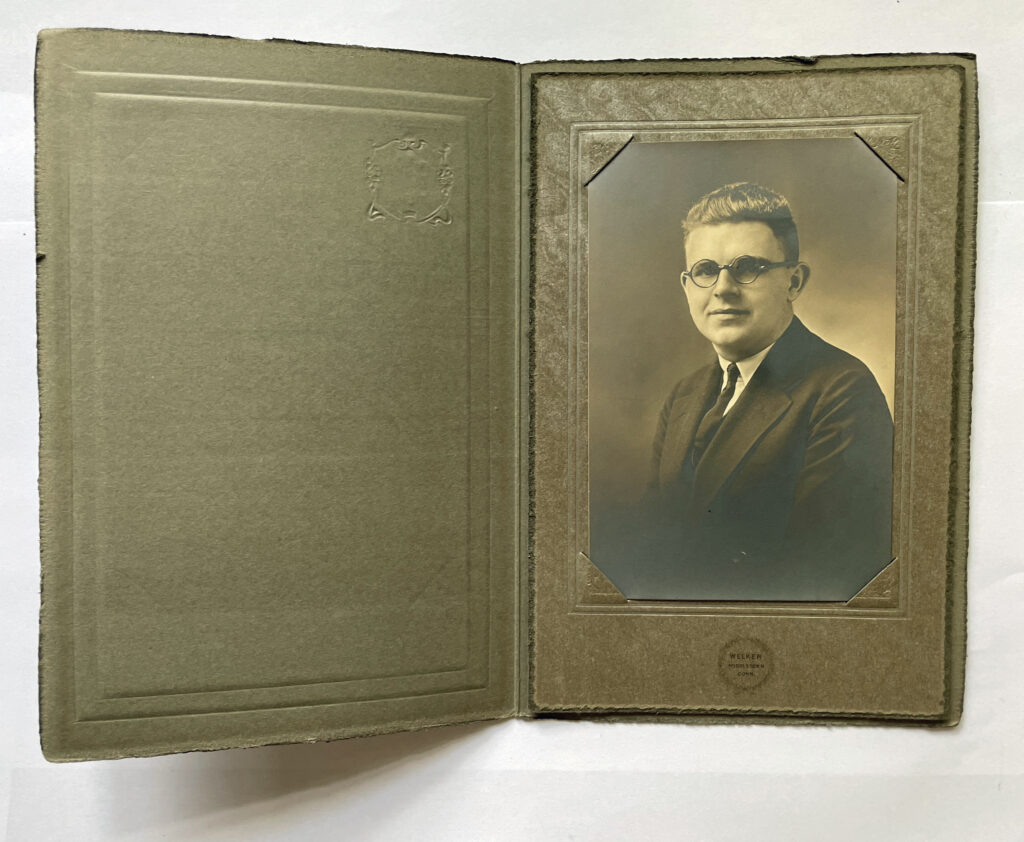

This is the second part of the story of Harold Griffis as a Methodist minister and pastor.

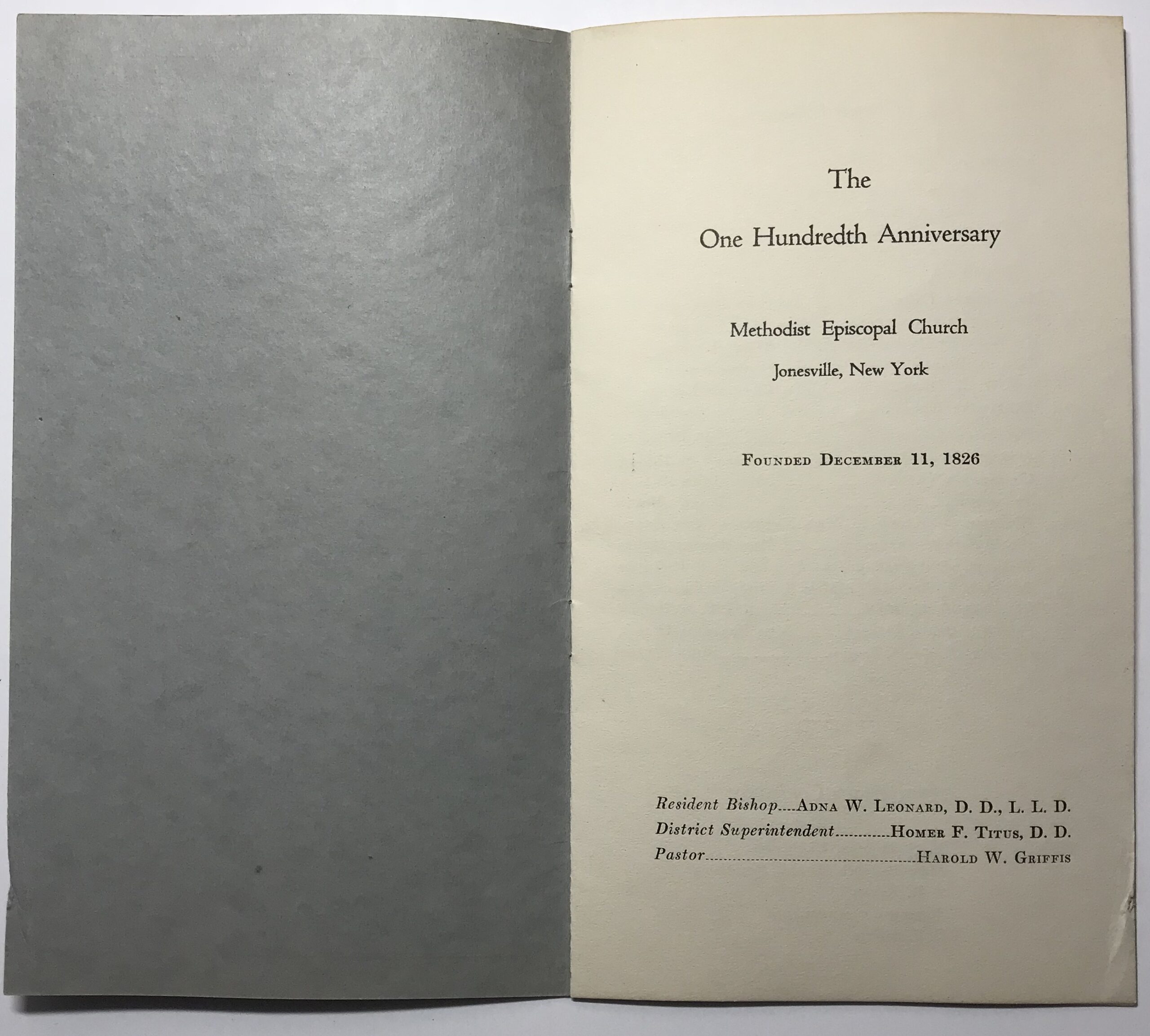

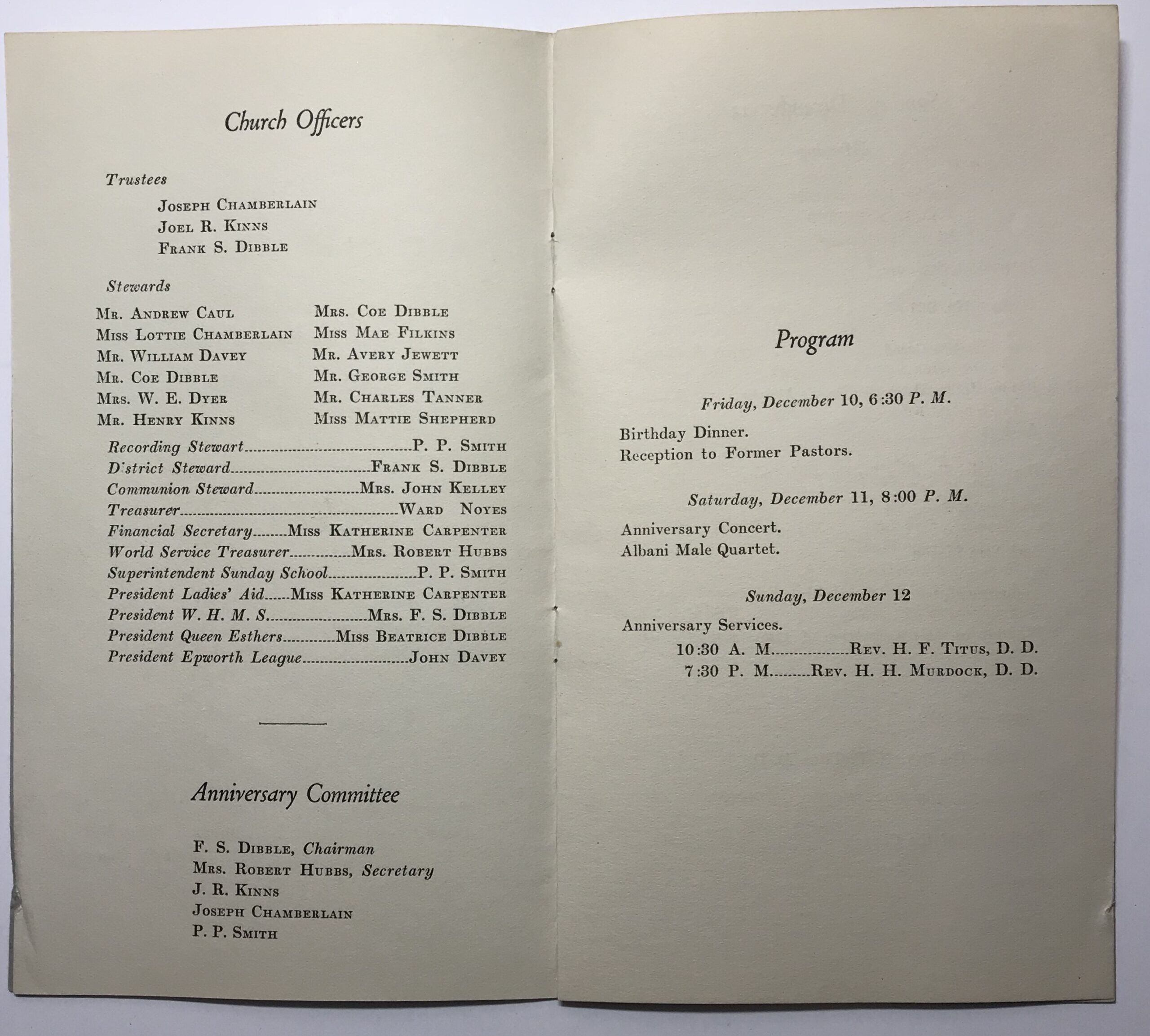

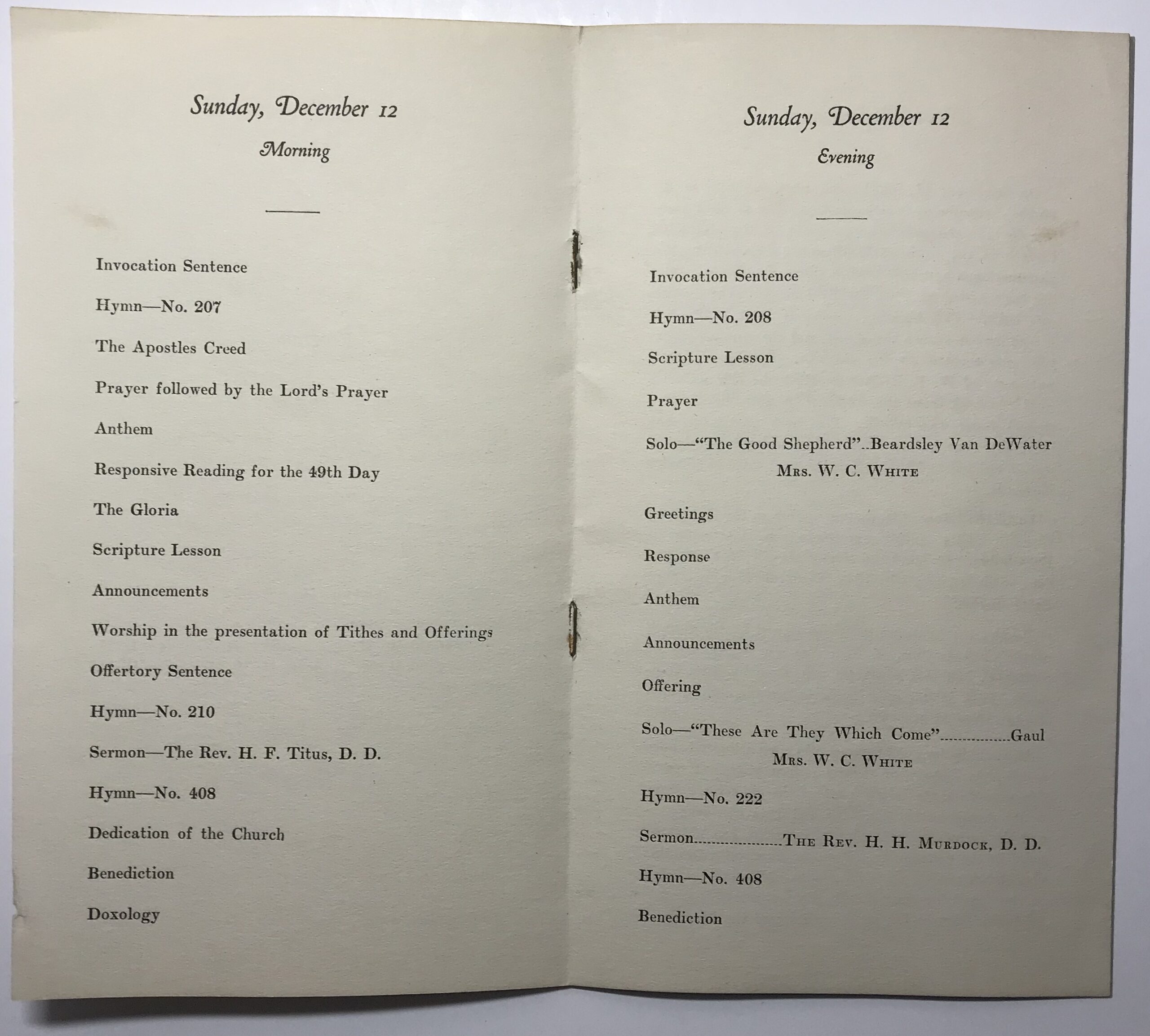

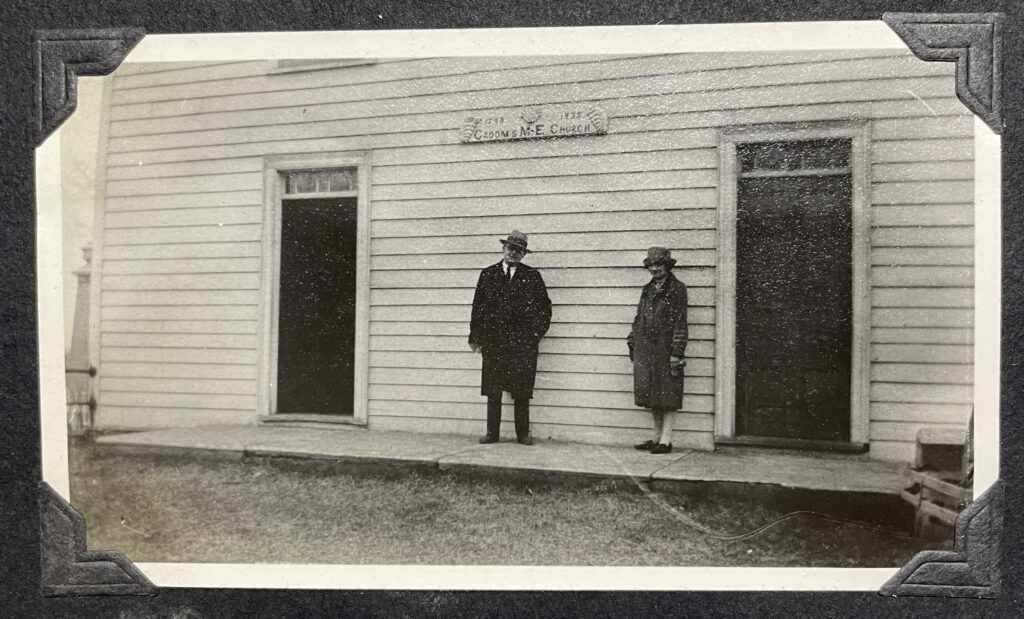

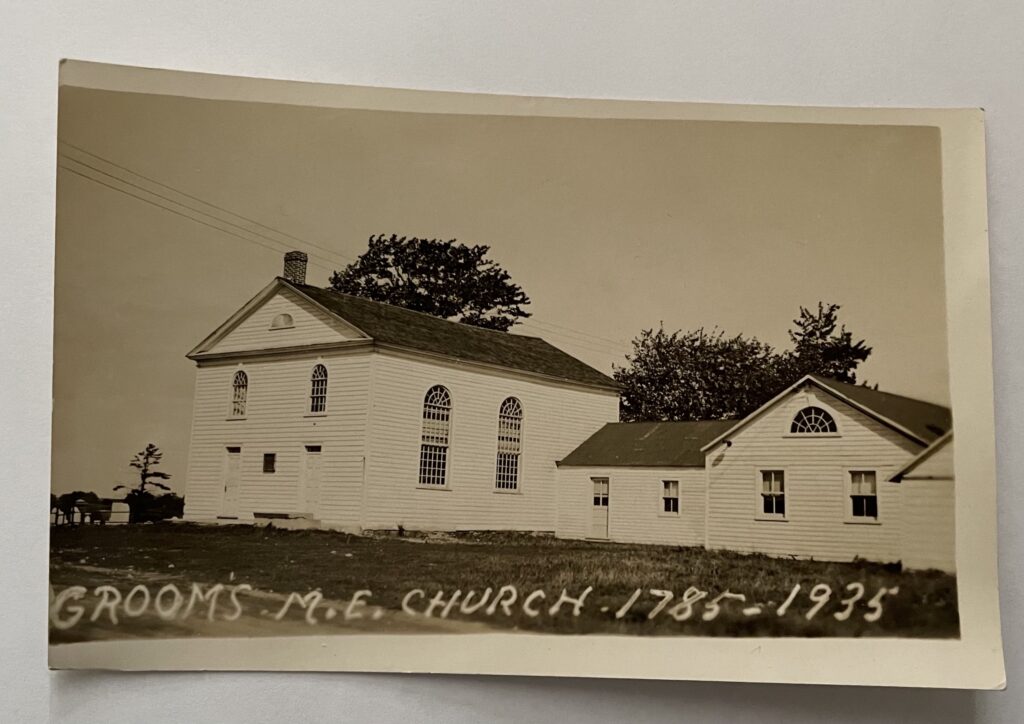

The following reflects the major milestones in his career within the Methodist Episcopal church. The first part of the story covered Harod’s career up through his pastoral duties with the Jonesville Methodist Episcopal (M.E.) Church and Groom’s M.E. Church from 1925 – 1928. Part II of the story resumes with his career in 1928 at the Methodist M.E. Church in Williamstown, Massachusetts and at the First Methodist Church in Troy, New York (indicated in bold face below).

| Year | Position |

| 1925 | Pastor of Jonesville Methodist Episcopal (M.E.) Church and Groom’s M.E. Church, NY |

| 1928 | Pastor at Methodist M.E. Church in Williamstown, MA |

| 1930 | Pastor at Trinity Church, Troy, NY |

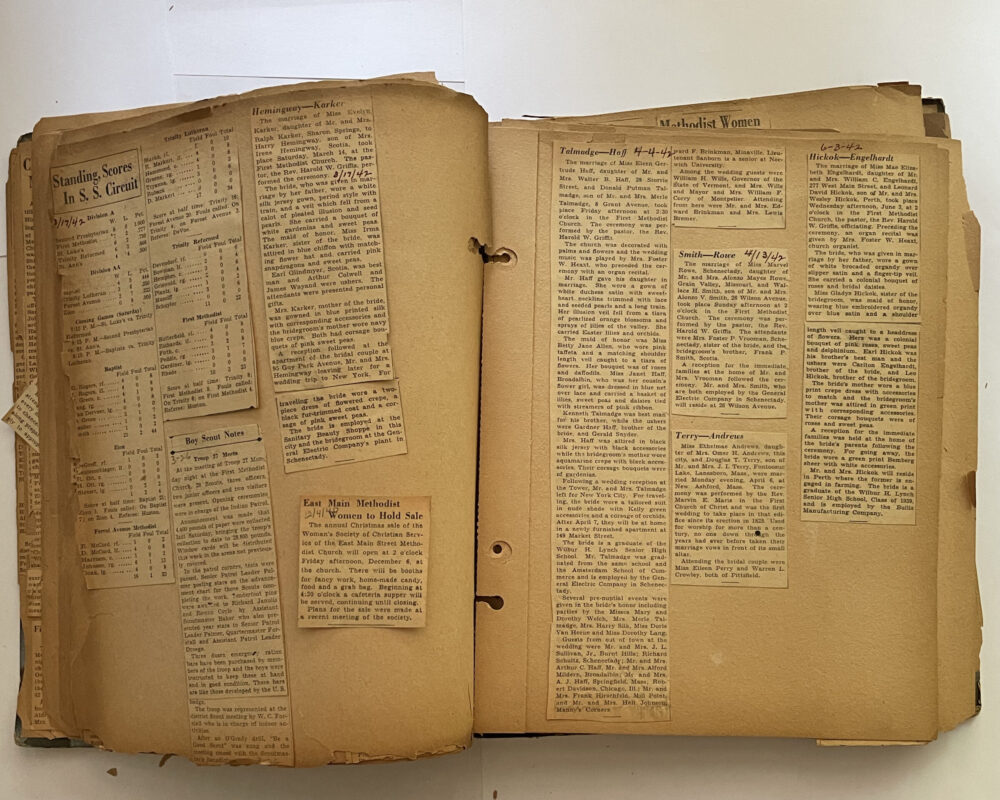

| 1938 | Pastor at the First Methodist Church, Amsterdam, NY |

| 1940 | In addition to First Methodist Church, pastor of East Main M.E. Church, Amsterdam |

| 1946 | District Superintendent of Troy District |

| 1948 | Pastor at 5th Avenue & State Street Methodist Church, Troy, NY |

| 1954 | District Superintendent of Albany District |

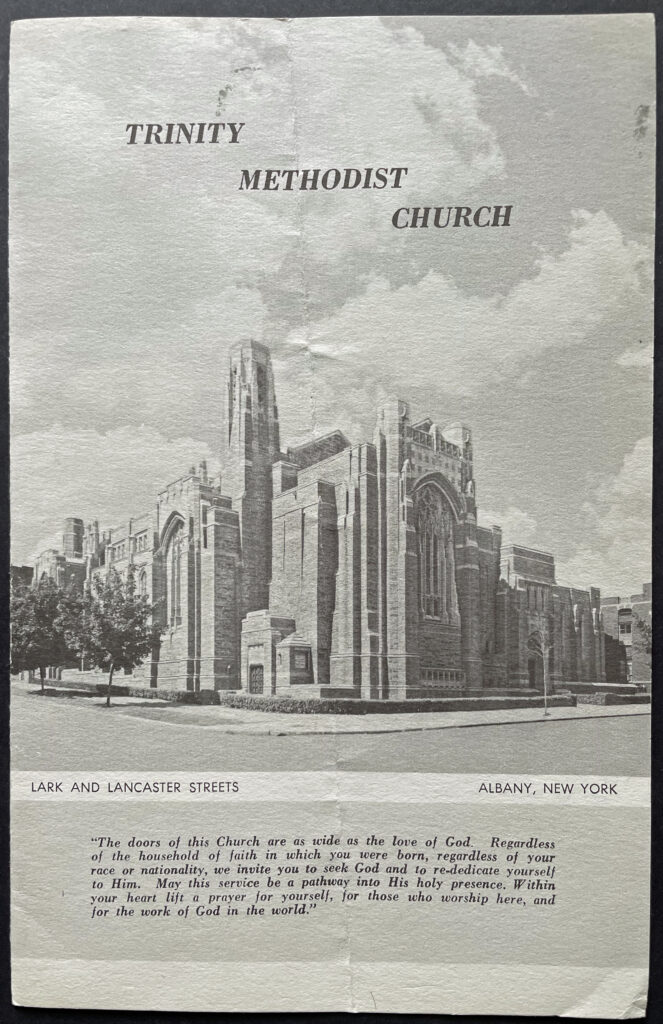

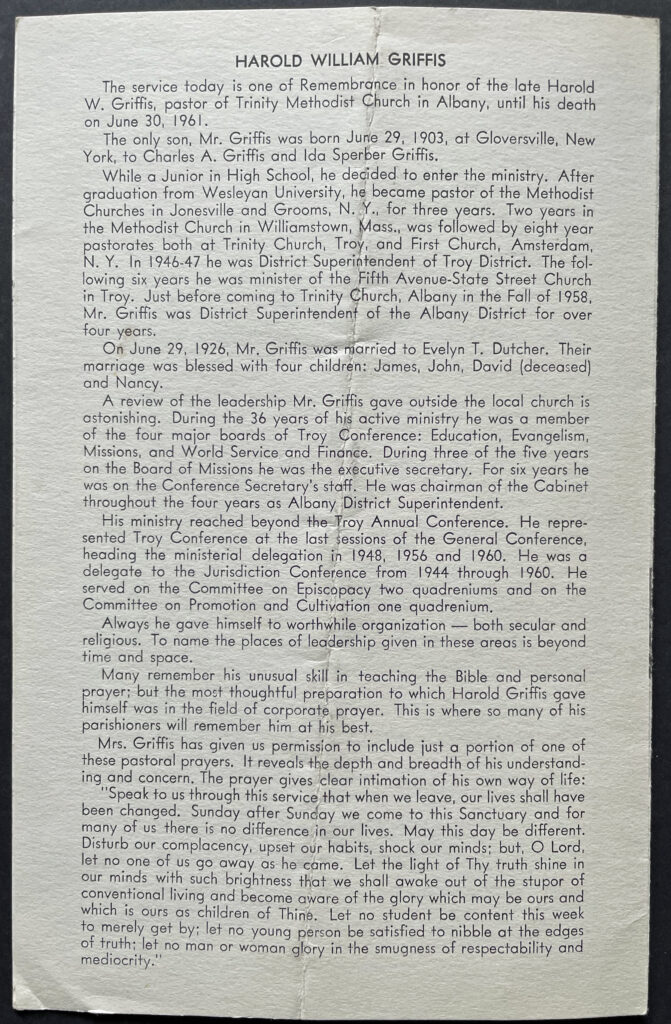

| 1958 – 1961 | Pastor at Trinity Methodist Church, Albany, NY |

1928 – 1930: Williamstown Massachusetts

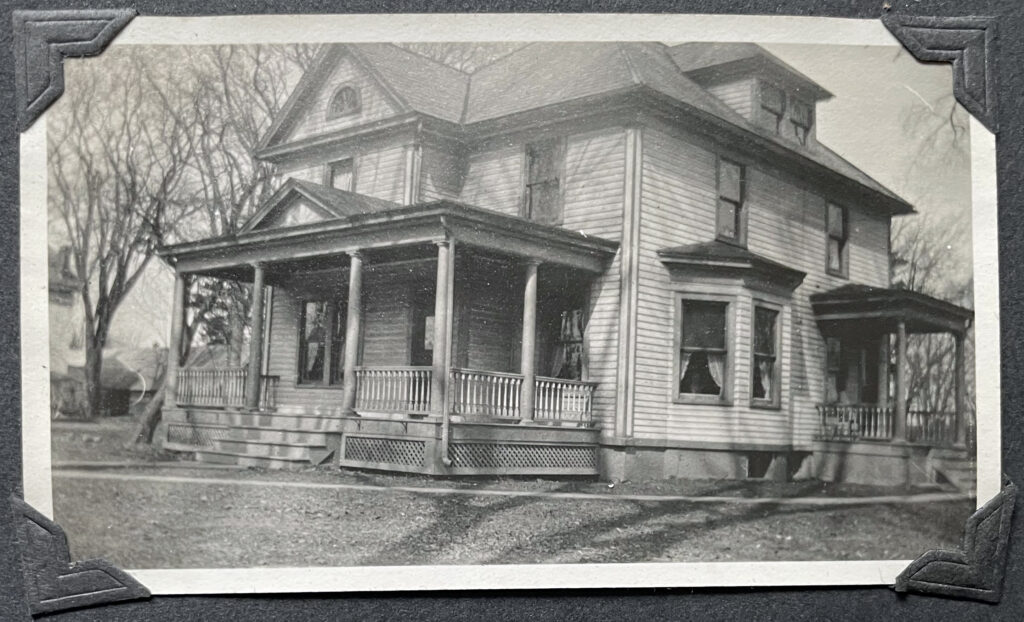

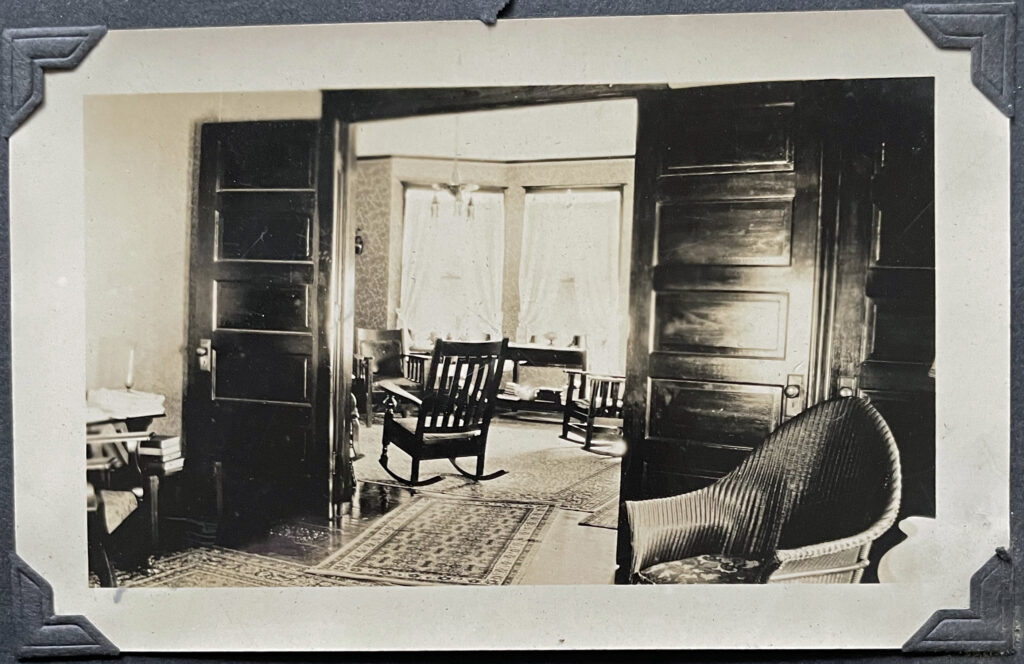

After their productive years serving the Grooms M.E. Church and the Jonesville M.E. Church, Evelyn and Harold moved to Williamstown, Massachusetts where Harold was the pastor at the Methodist Church for two years.

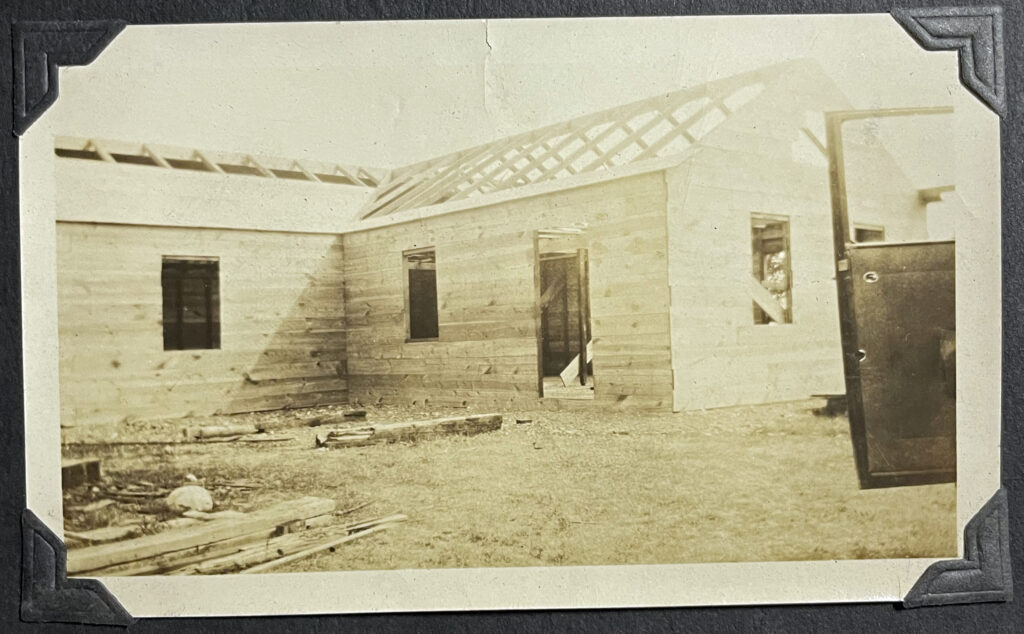

The first Methodist church in Williamstown was originally a white frame building erected in 1845. The lot for the building, which in later years was fitted with a stage and became known as the Opera House, was acquired by Summer Southworth, a manufacturer of cotton goods.

When the congregation grew and required a larger building, Southworth contributed $8,000 toward building the red brick church, which cost $13,000, aside from the lot and furnishing. The church was dedicated on March 6, 1872.

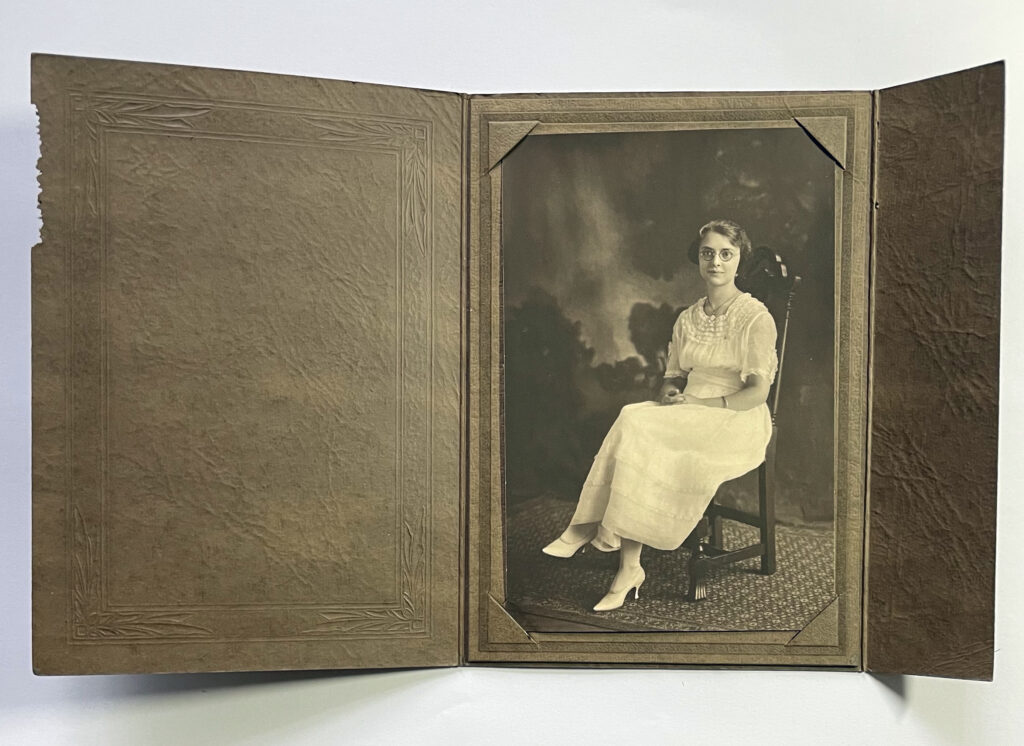

Southworth also gave the Methodists a gift of music, an Opus 447 pipe organ manufactured by the William A. Johnson and Son Co. of Westfield. [1] The photograph was taken by Evelyn Griffis, (personal scrapbook). Click for larger view.

Today, the Williamstown church still stands but it is now the Williamstown Community Preschool center. The parsonage no longer exists. Where the parsonage once stood, adjacent to the church, there is now used as a playground for the preschoolers (for larger views of photographs: photo one, two, three, and four.)

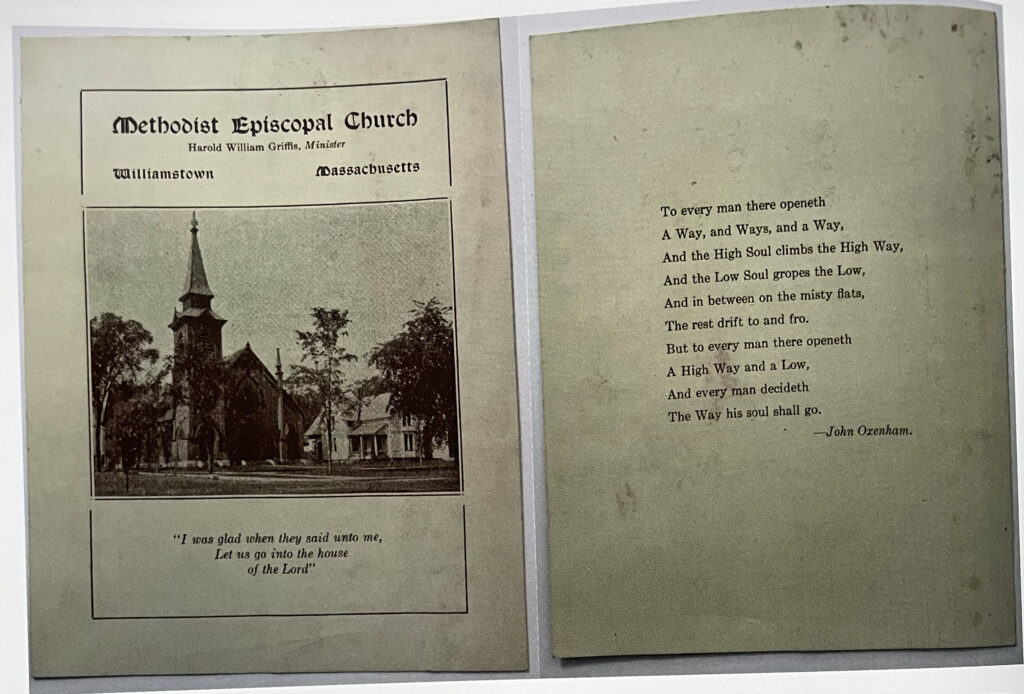

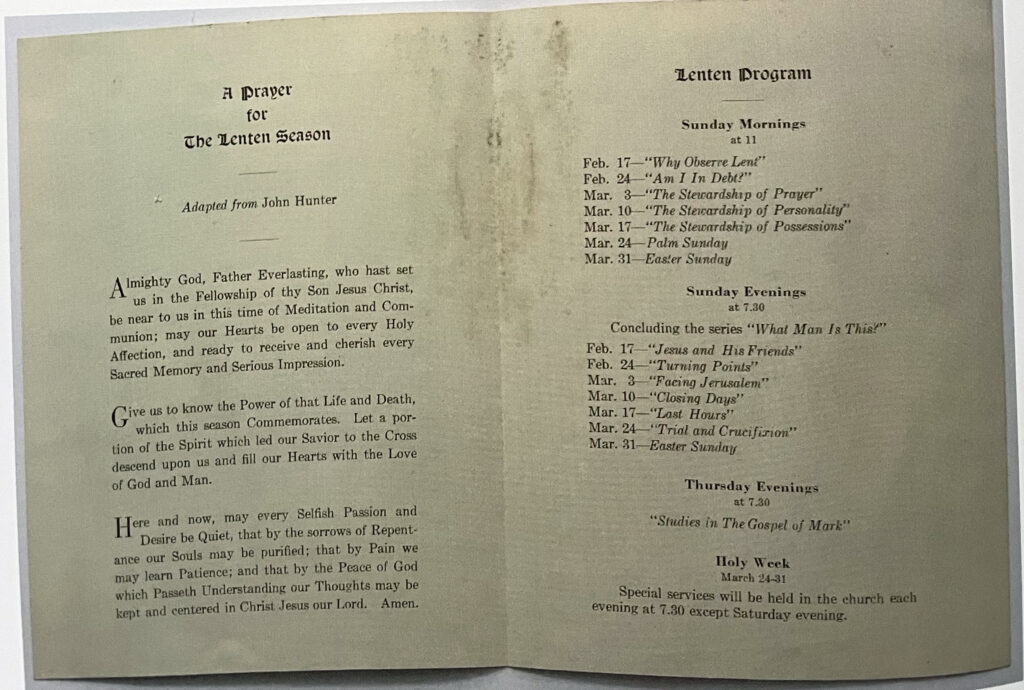

The following is a Lenten Program from the Williamstown church when Harold was the pastor.

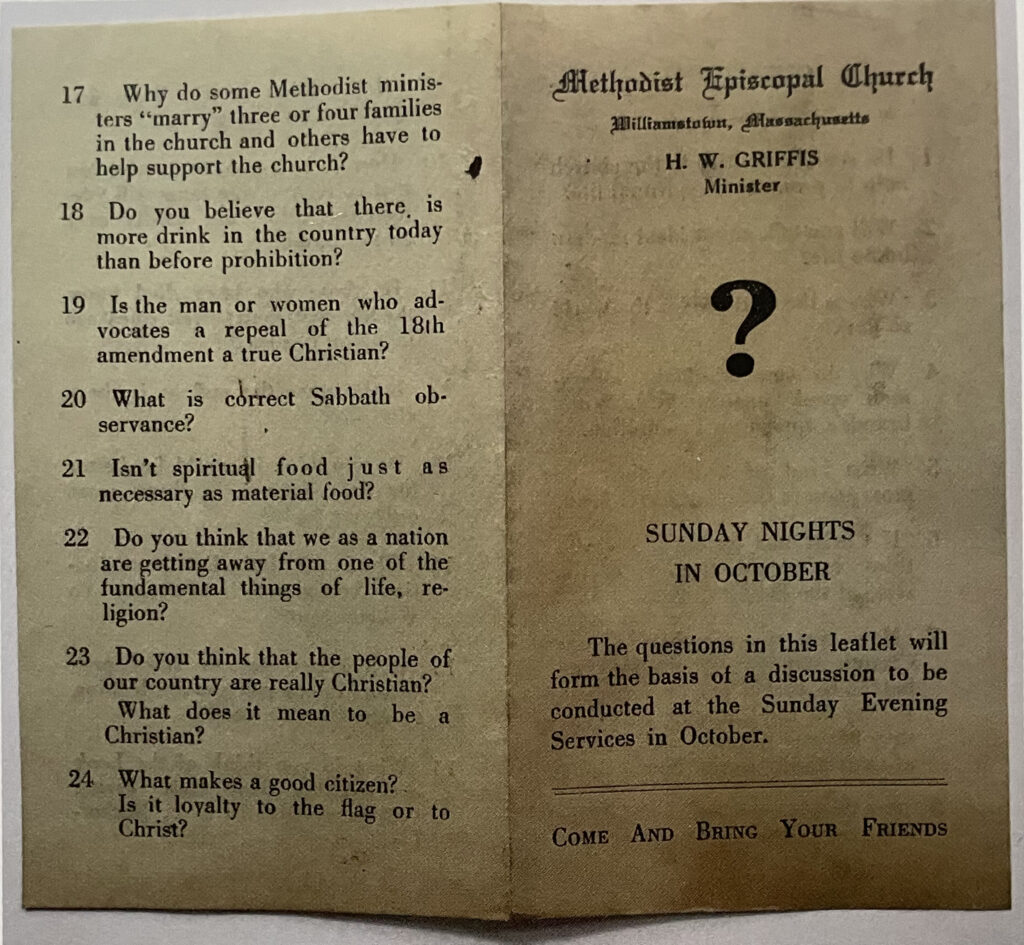

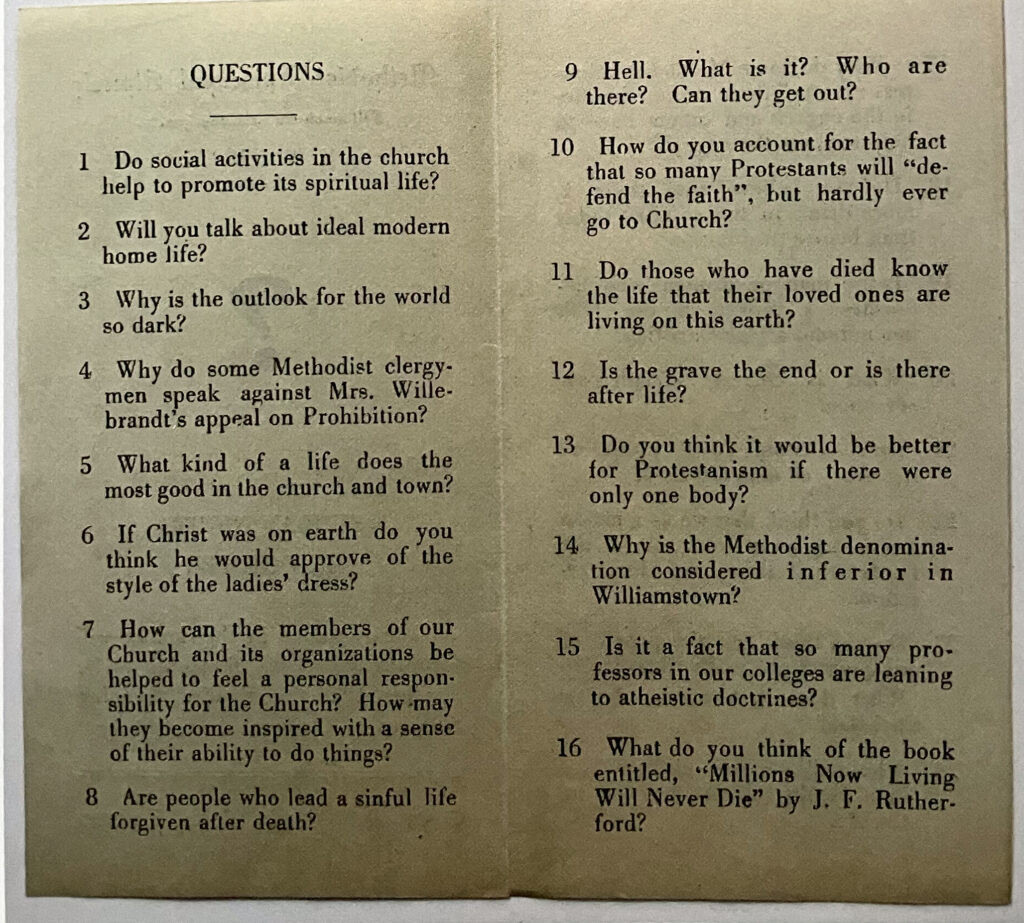

The following is a pamphlet from the Williamstown church on religious questions for discussion at Sunday evening service. The questions reflect Harold’s interest in engaging his parishioners on spiritual issues that were defined or viewed through current events and daily life experiences. It perhaps also indicates that Harold was a keen observer of community attitudes and his desire to understand the values held by his parishioners.

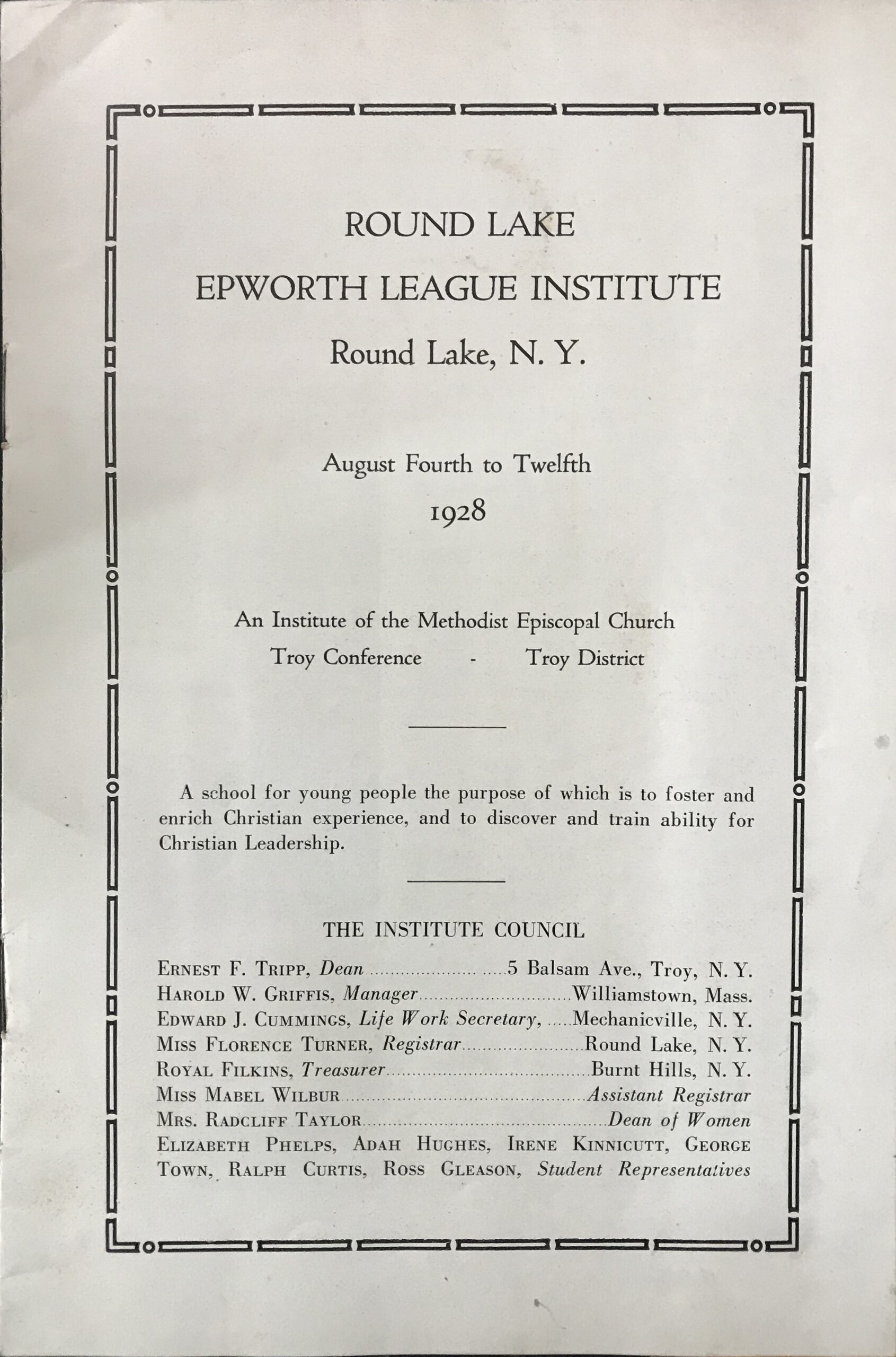

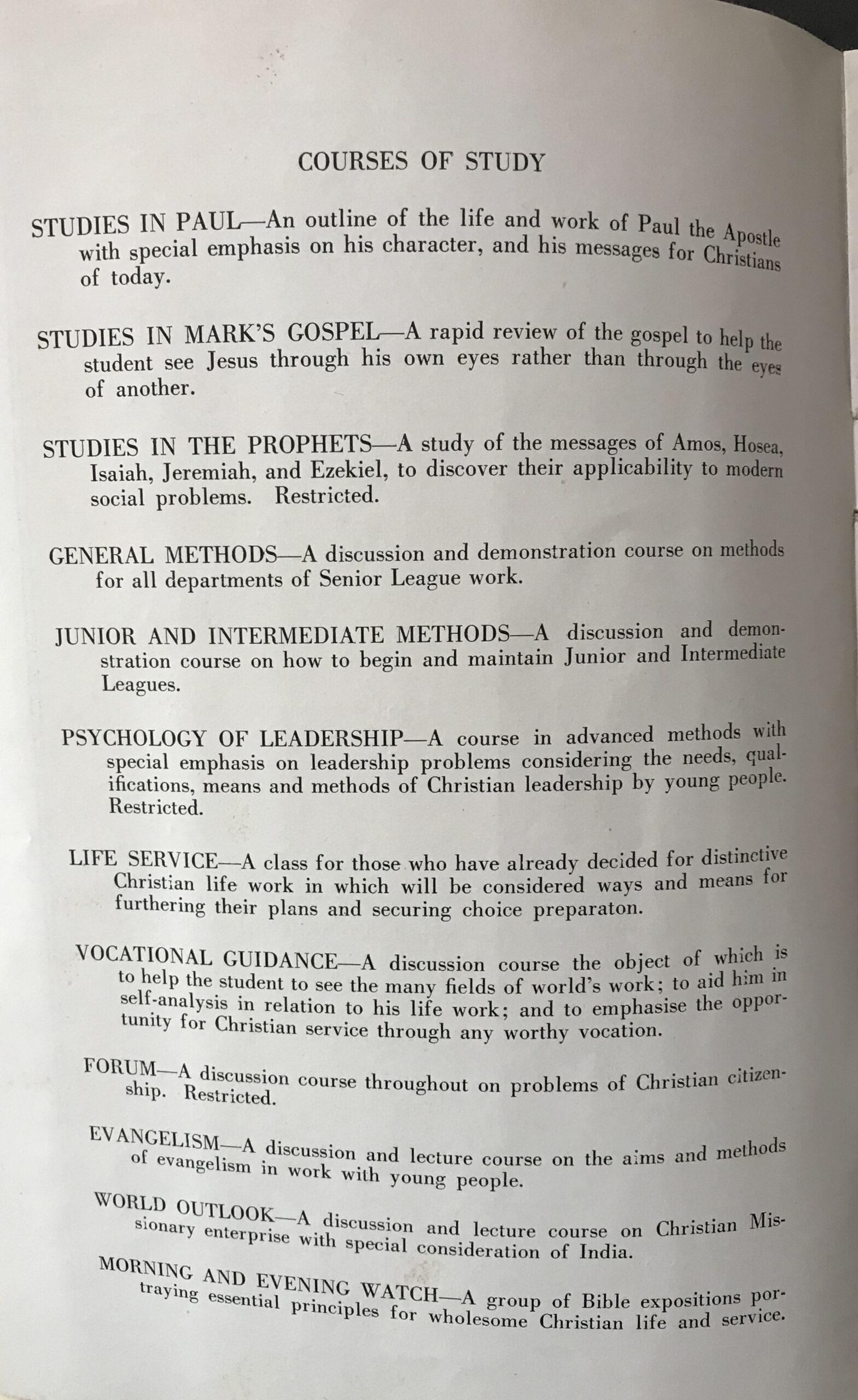

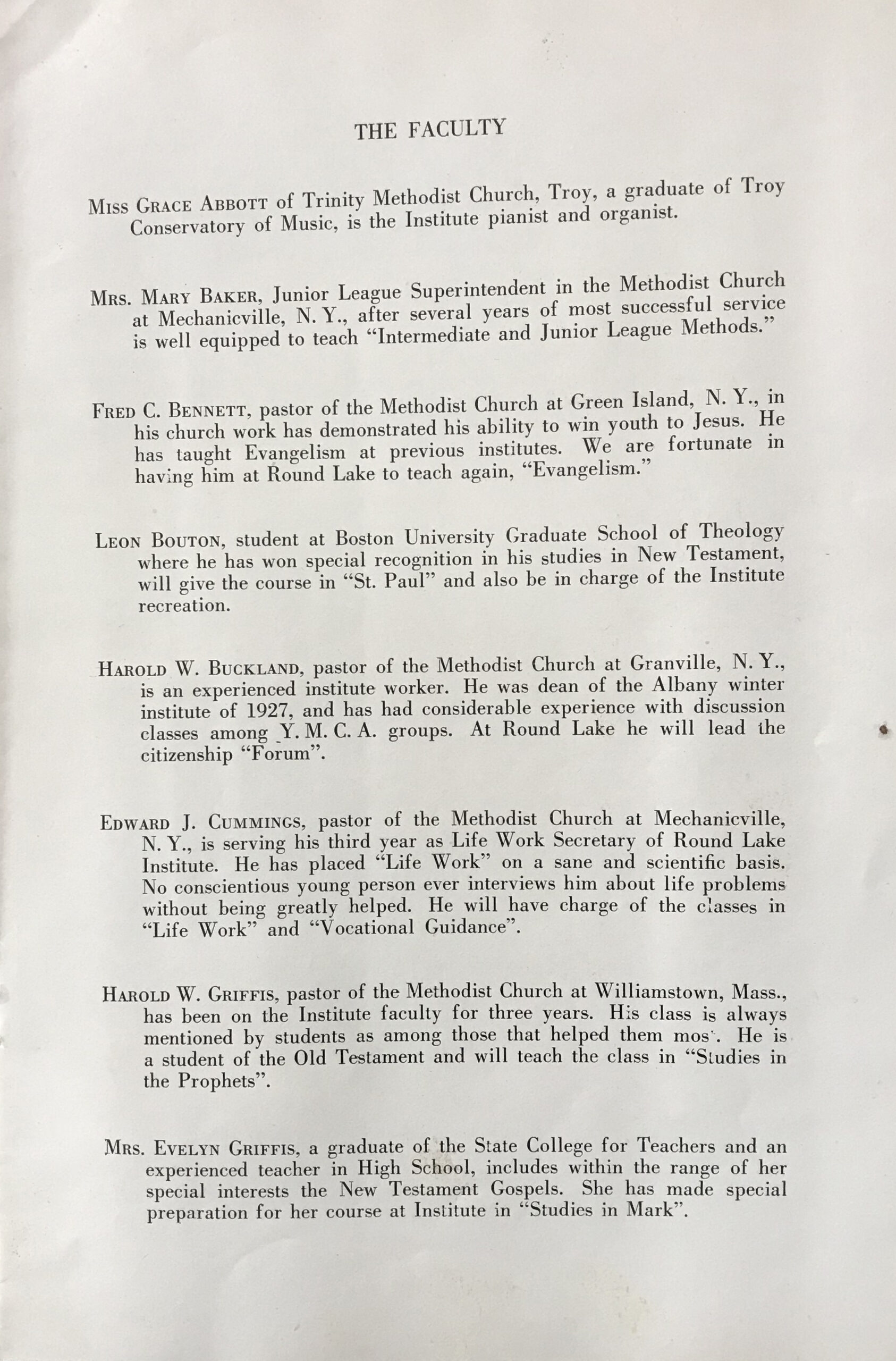

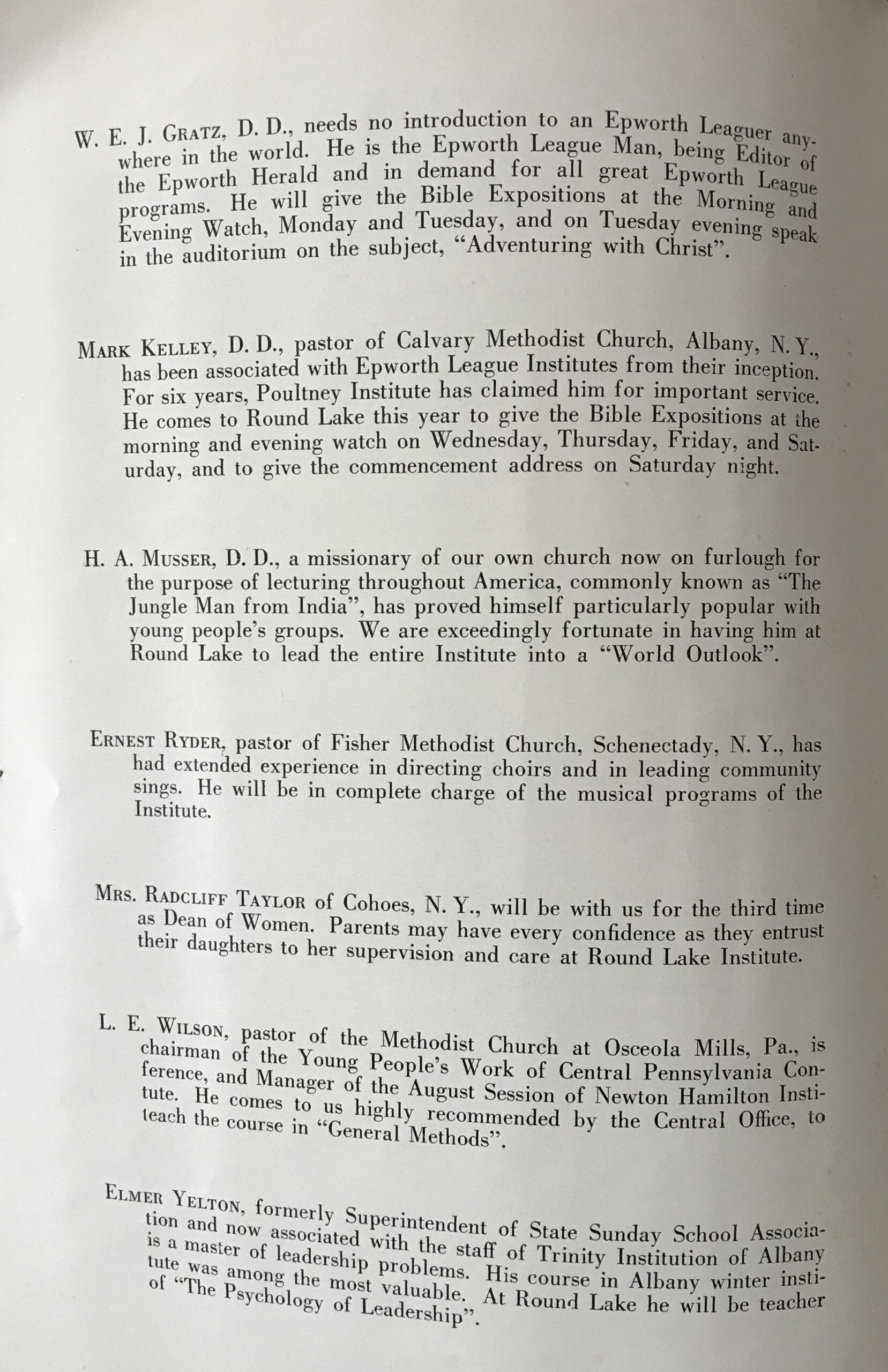

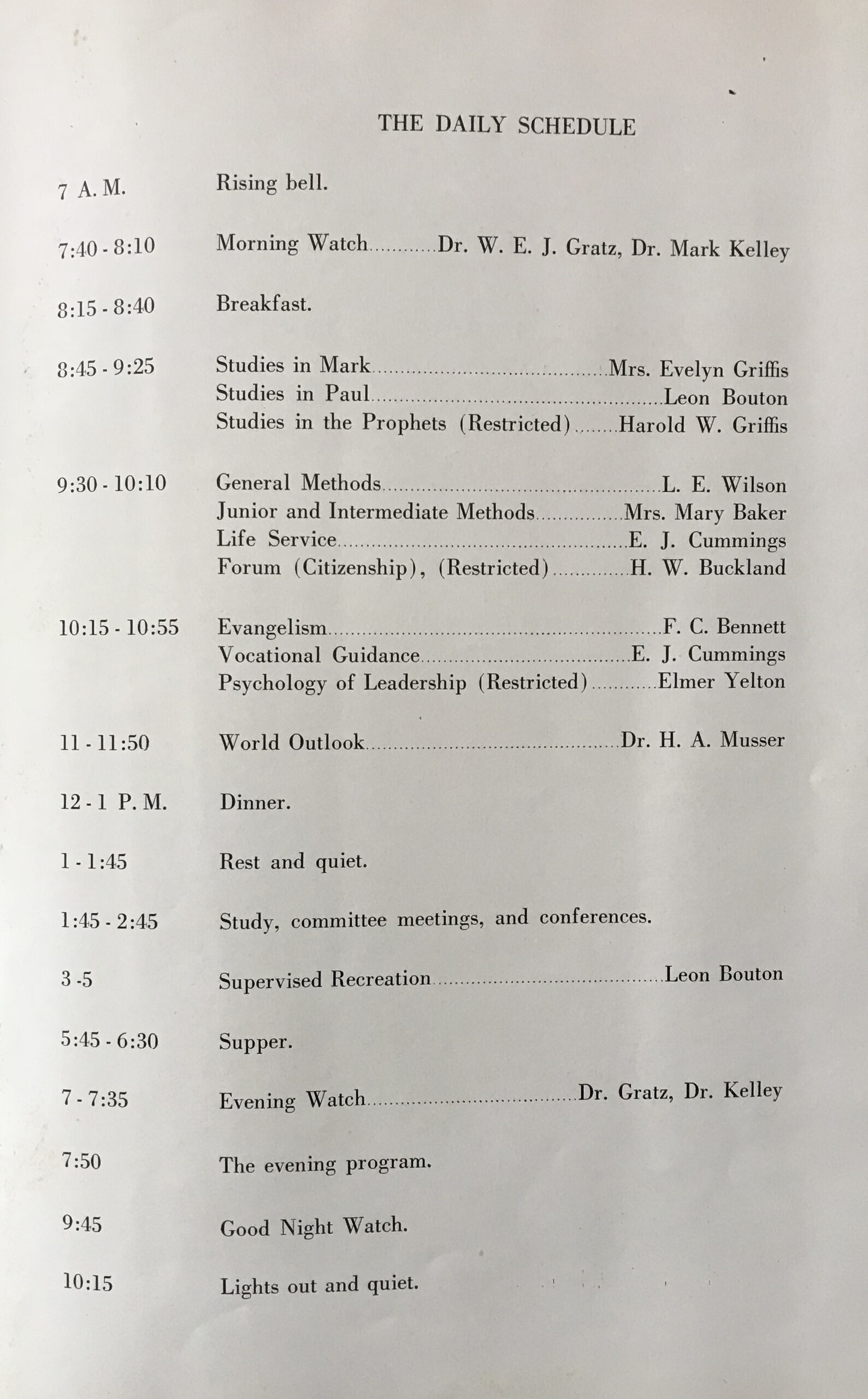

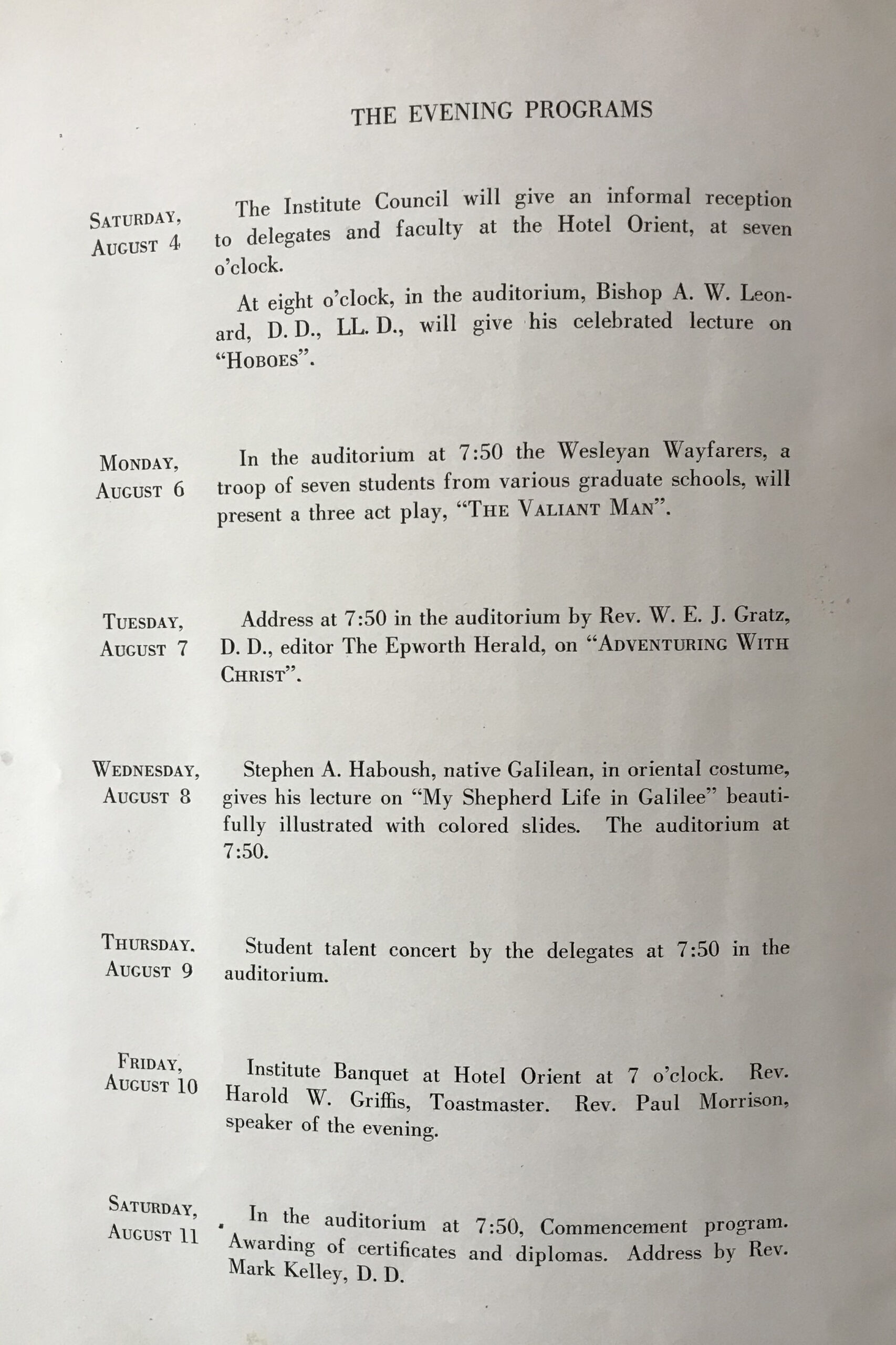

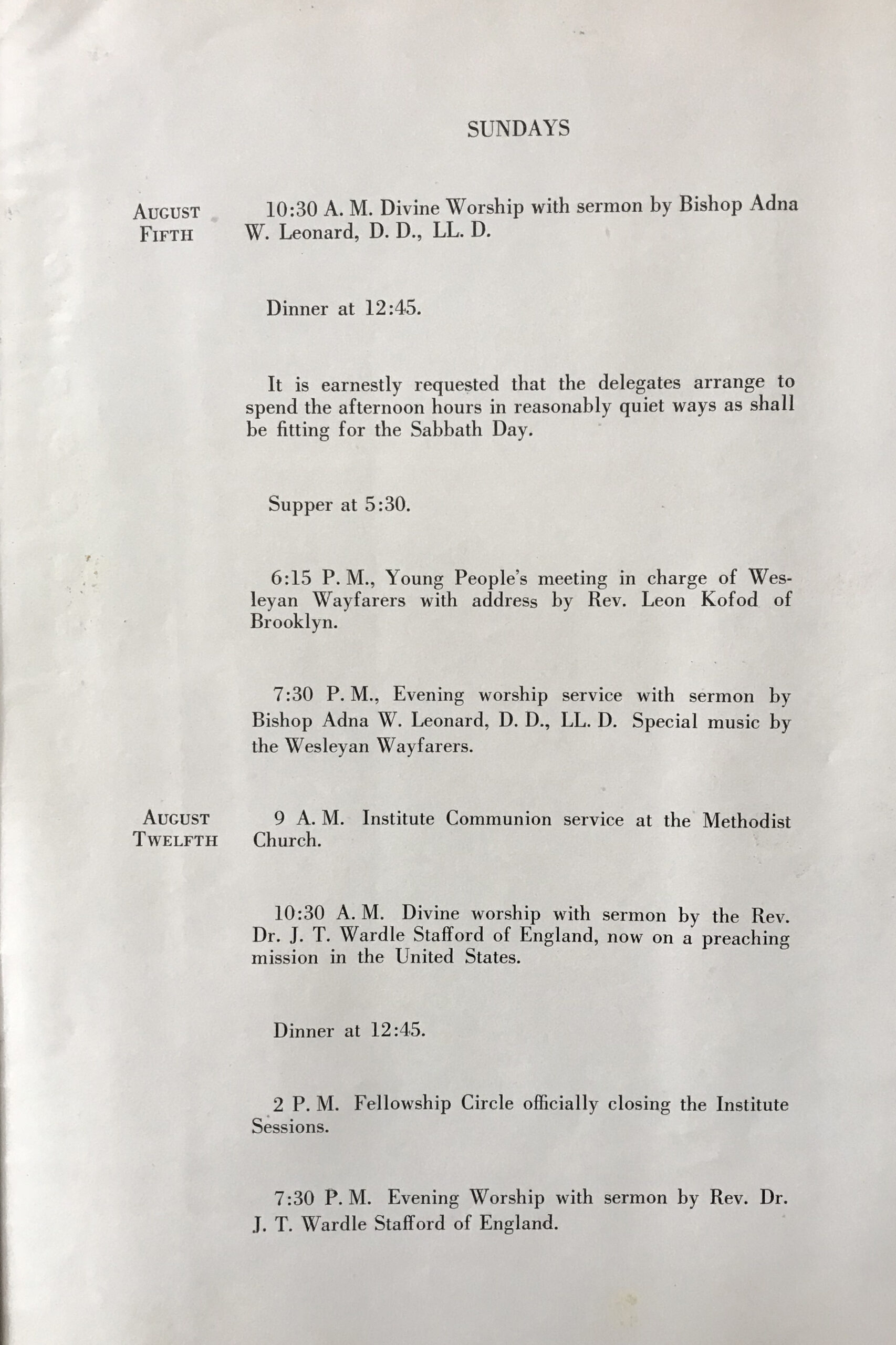

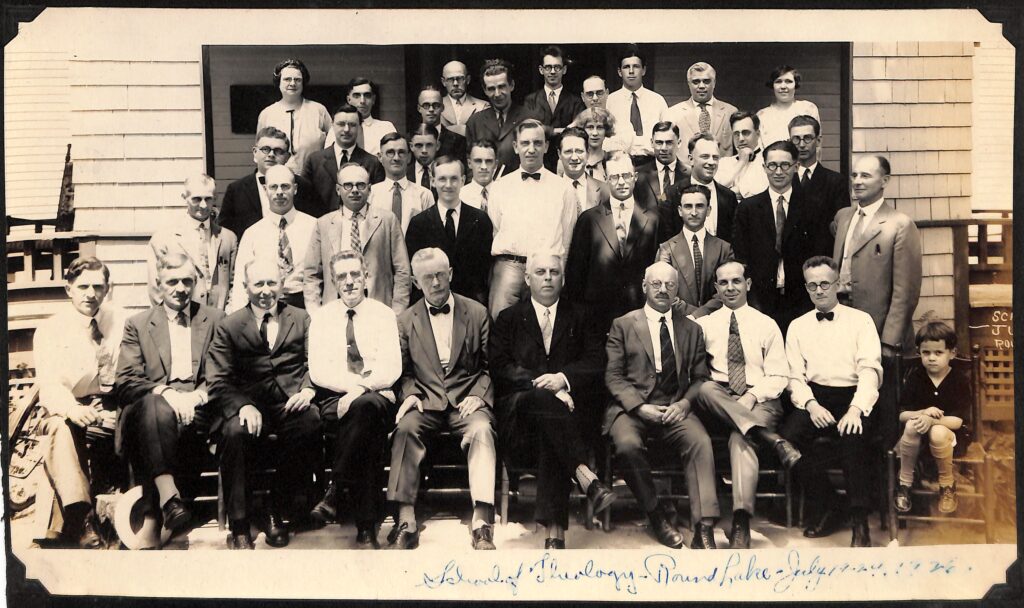

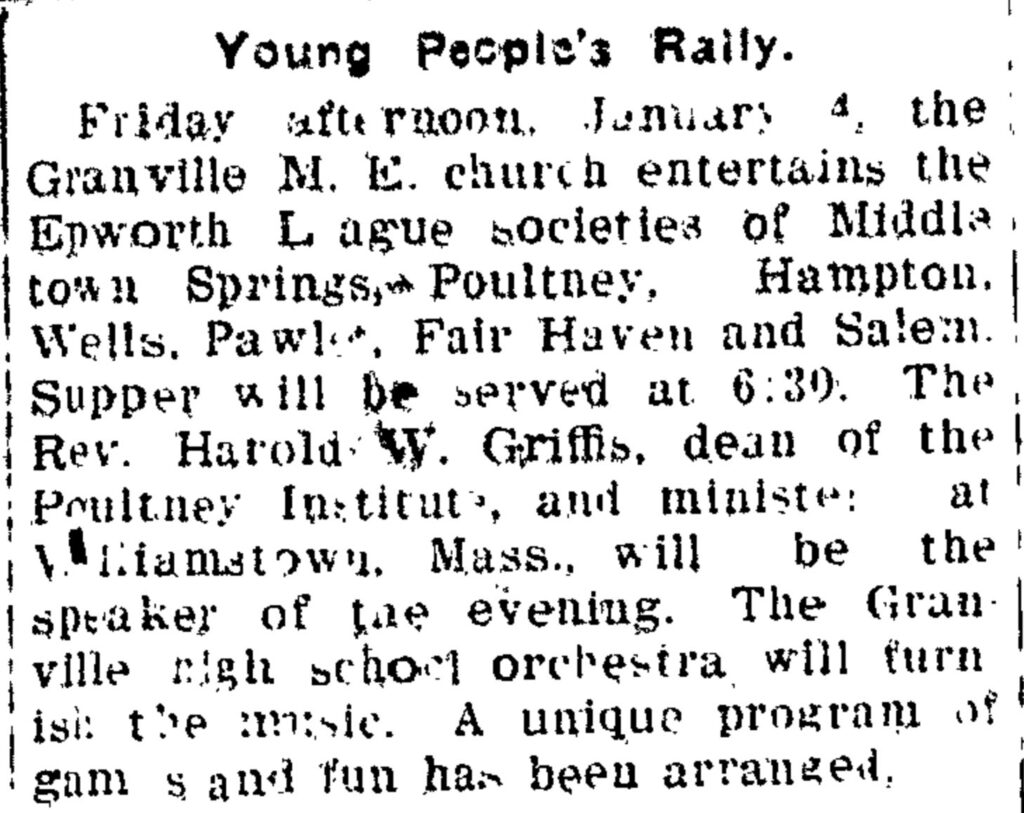

While a pastor at the Williamstown M.E. Church, Harold was also deeply involved with the Epworth League and was Dean of the Epworth League Pultney Institute each summer. [2]

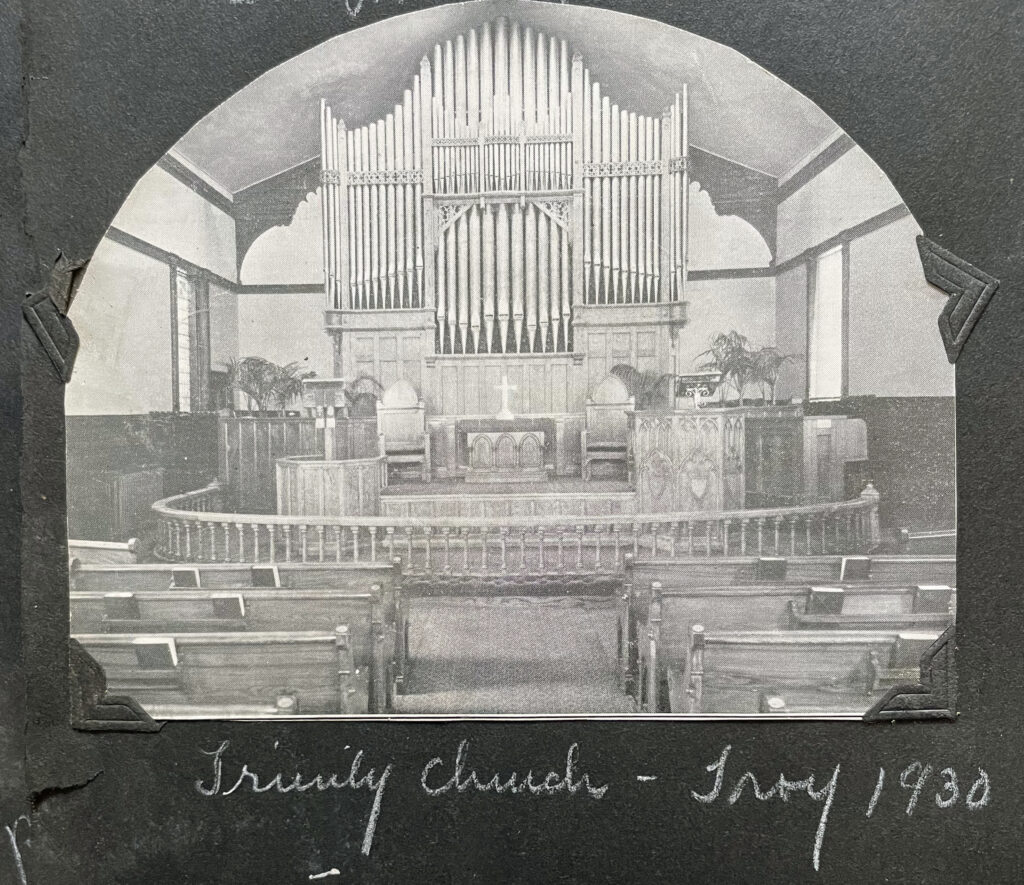

1930 – 1938: Trinity Church, Troy, NY

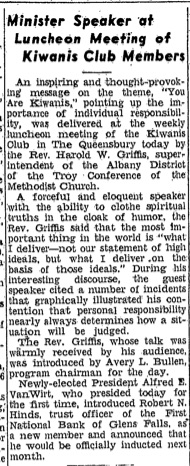

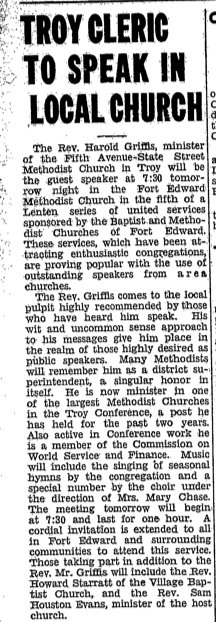

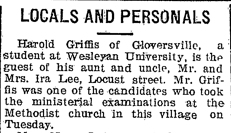

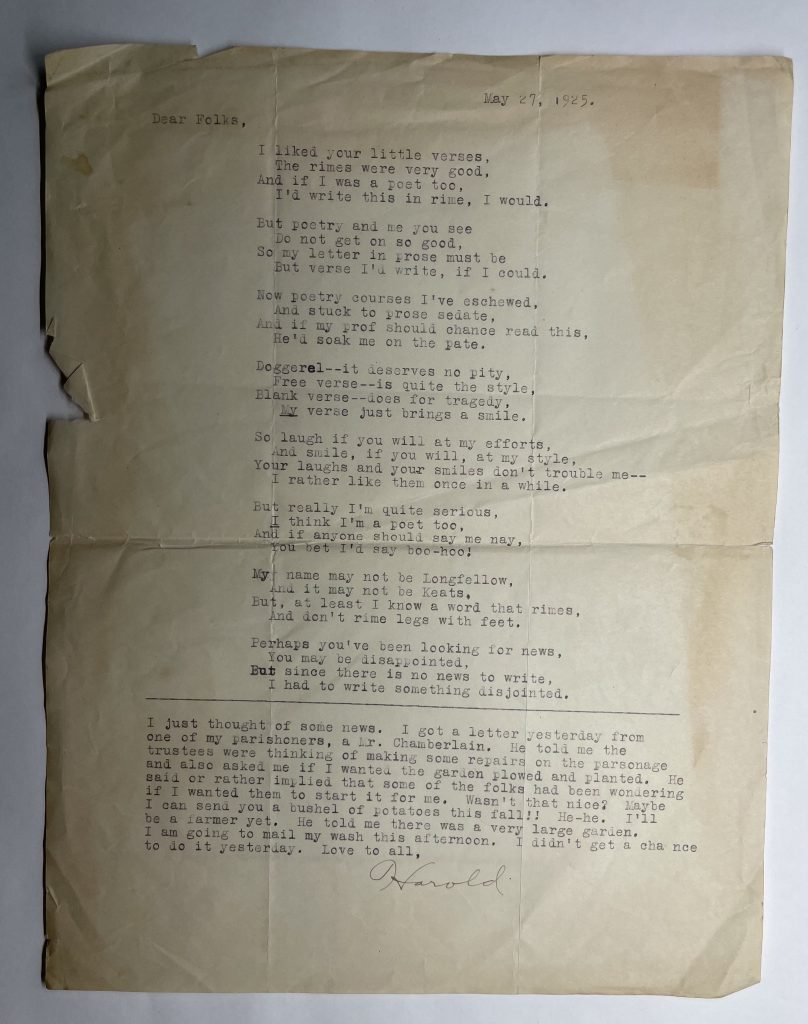

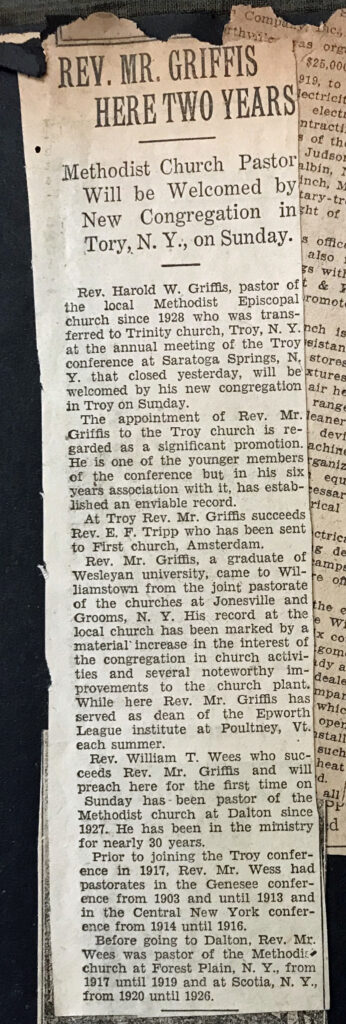

His career as a pastor continued with an eight year assignment at the Trinity Church in Troy, New York. The following newspaper article provides a cogent summary of his accomplishments at Jonesville and Grooms churches, prior to his pastoral duties in Williamstown, Massachusetts.

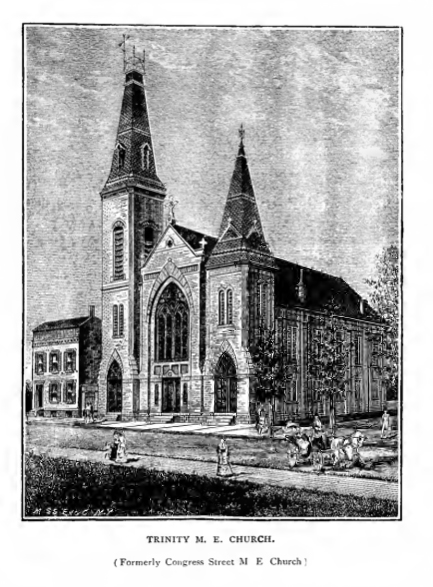

Troy, New York had a long history of Methodist congregants and churches. The first church was built in in the early 1800’s. As the Methodists grew in number, additional churches were started throughout Troy. Members of the original State Street church organized many of these churches. By 1860 there were nine Methodist churches. In addition to State Street Methodist Episcopal Church there was North Second Street (later named Fifth Avenue), Congress Street (later named Trinity), Third Street, Levings Chapel, Albia, North Troy, German, and Zion. [3]

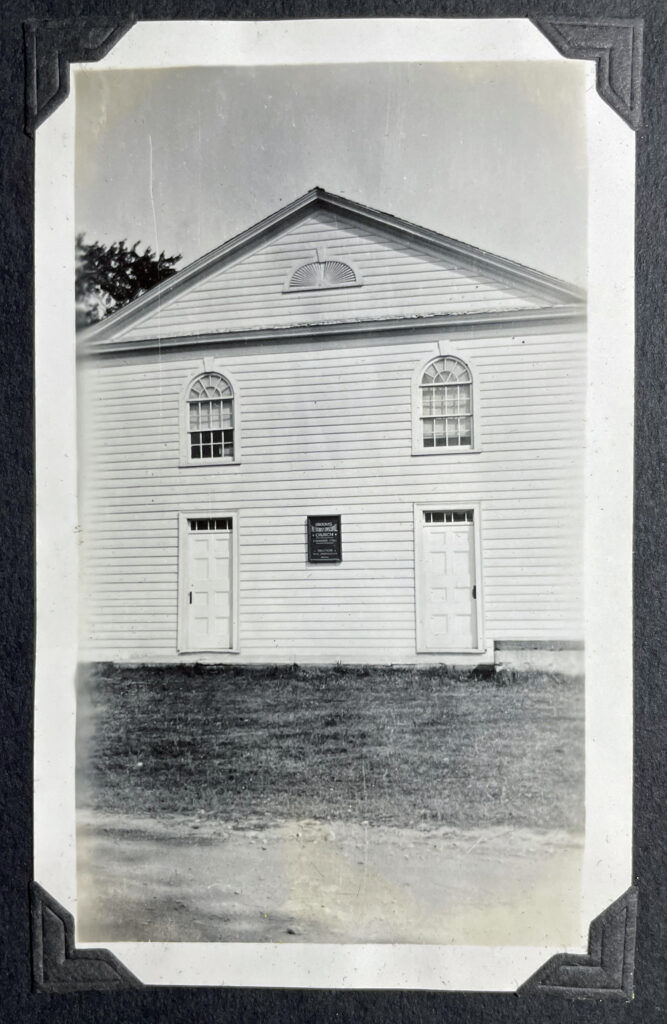

The Trinity Methodist Episcopal church was formerly known as the Congress Street church.

“The Methodist Episcopal Church on Congress Street, Troy, N. Y., was organized in the month of October, 1846, in the following manner: Several persons from the State Street Methodist Episcopal Church, and the North Second Methodist Episcopal Church, came with certificates from the pastors of those churches to Rev. Oliver Emerson, pastor of the Third Street Church, and wished to come under his care and to be formed into a class to meet in Congress Street, Ida Hill. They were received and a class was formed under the care of Stephen Monroe and William H. Robbins.” [3]

In June 1847, an old blacksmith shop on the south side of Congress Street at an intersection with Ferry Street, was reconstructed for a house of worship. It was called the “Hemlock Church”. On its completion, the Sunday school of the society, began holding its sessions in the new meeting house. Desiring a larger structure, the congregants built a larger church of brick on the north side of Thirteenth Street, near the intersection with Congress Street. The corner stone of the brick church was laid in October, 1848. The building was originally dedicated on July 12, 1849. [4]

The pews in the church were free and no rentals for sittings were imposed or collected. The entire cost of the site, building and furniture was $6,199.84. The church was enlarged in 1860, accommodating two hundred more people. The building was then rededicated by the Rev. Bishop Matthew Simpson. Two years later, the Sunday school rooms were enlarged at a cost of $600. In 1880, the church was renovated and the corner towers were added along with other architectural features, at a cost of $14,084.94. The building was rededicated December 28, 1880. [5]

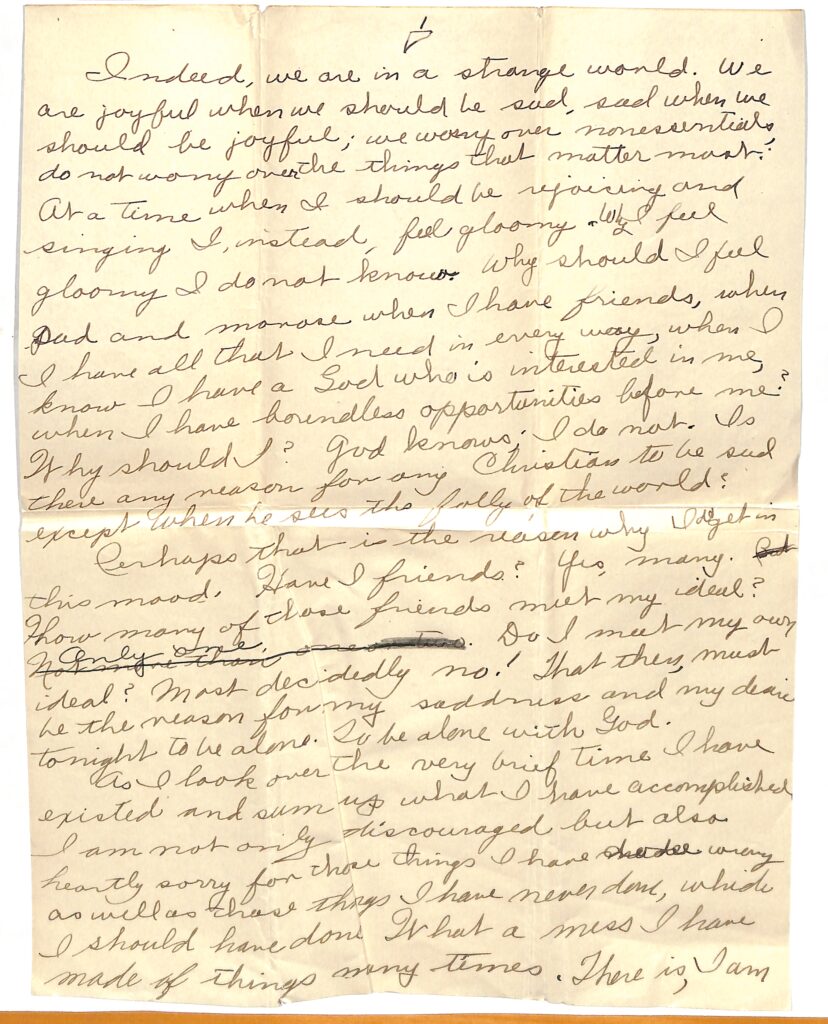

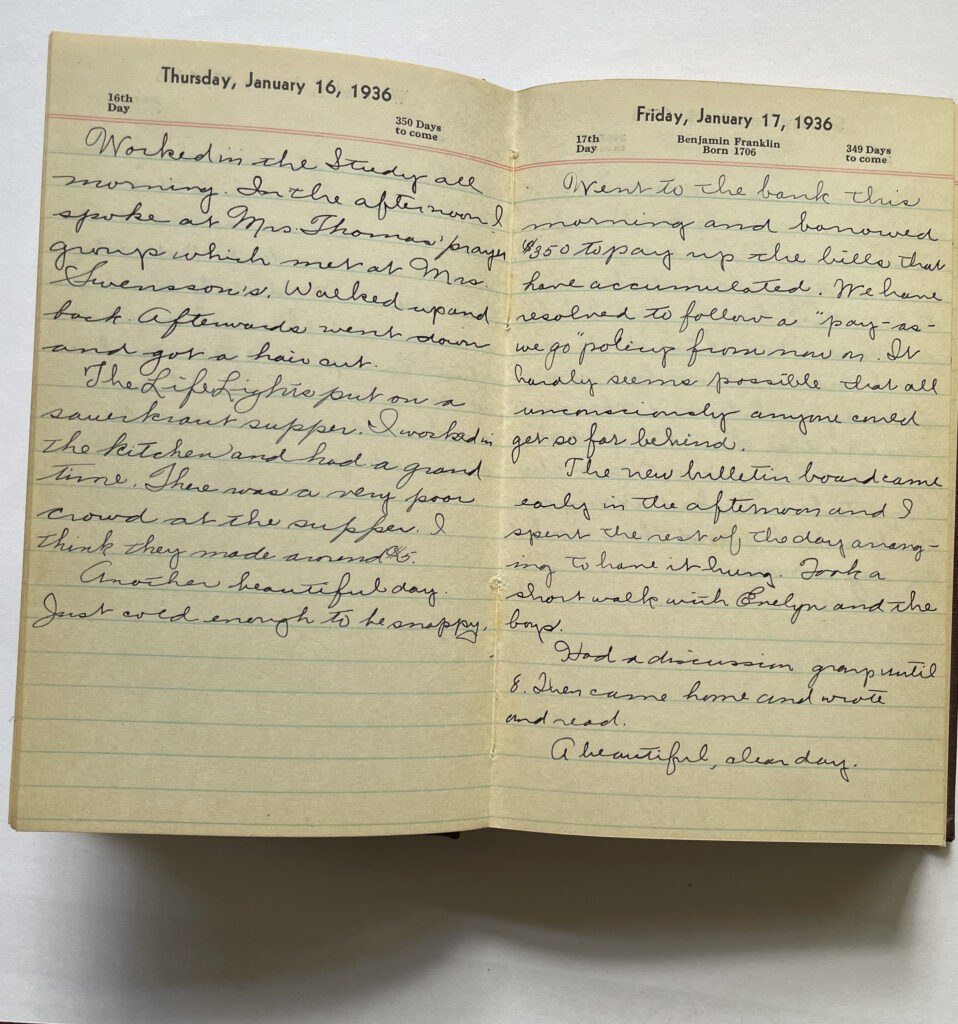

Harold’s Diary

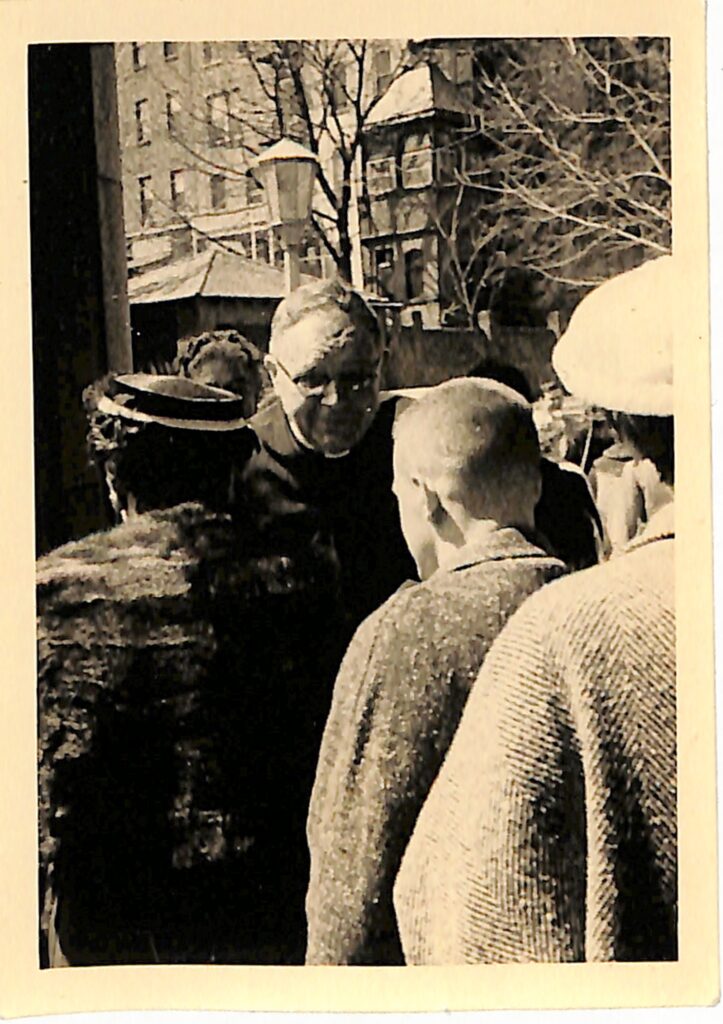

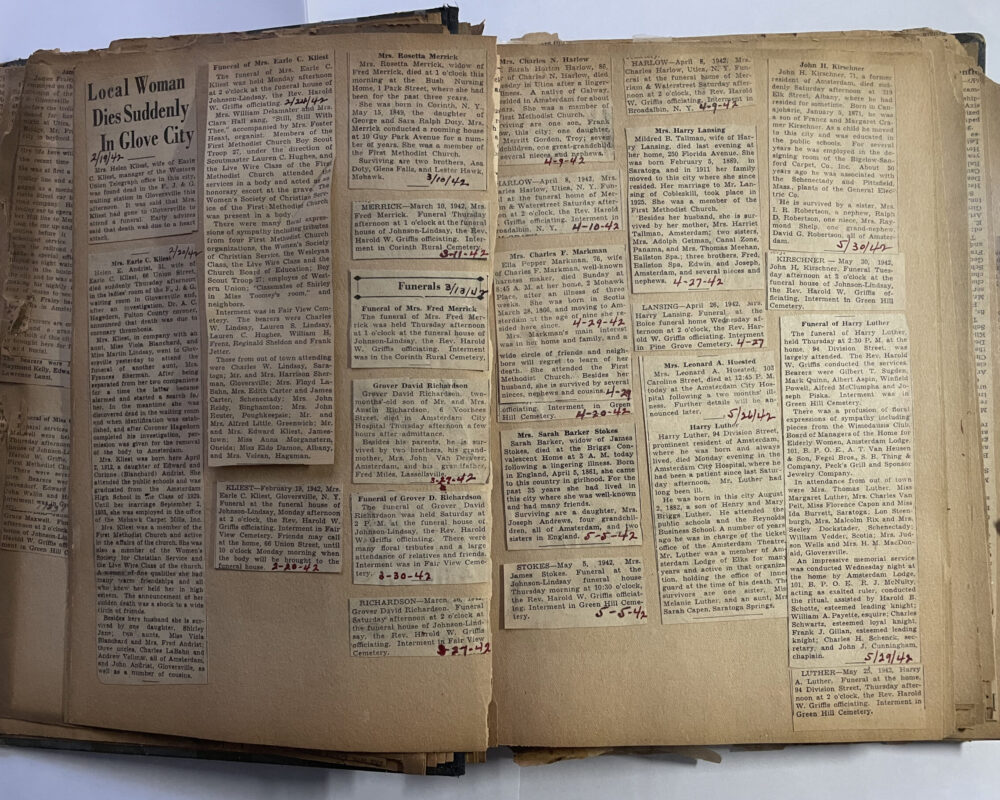

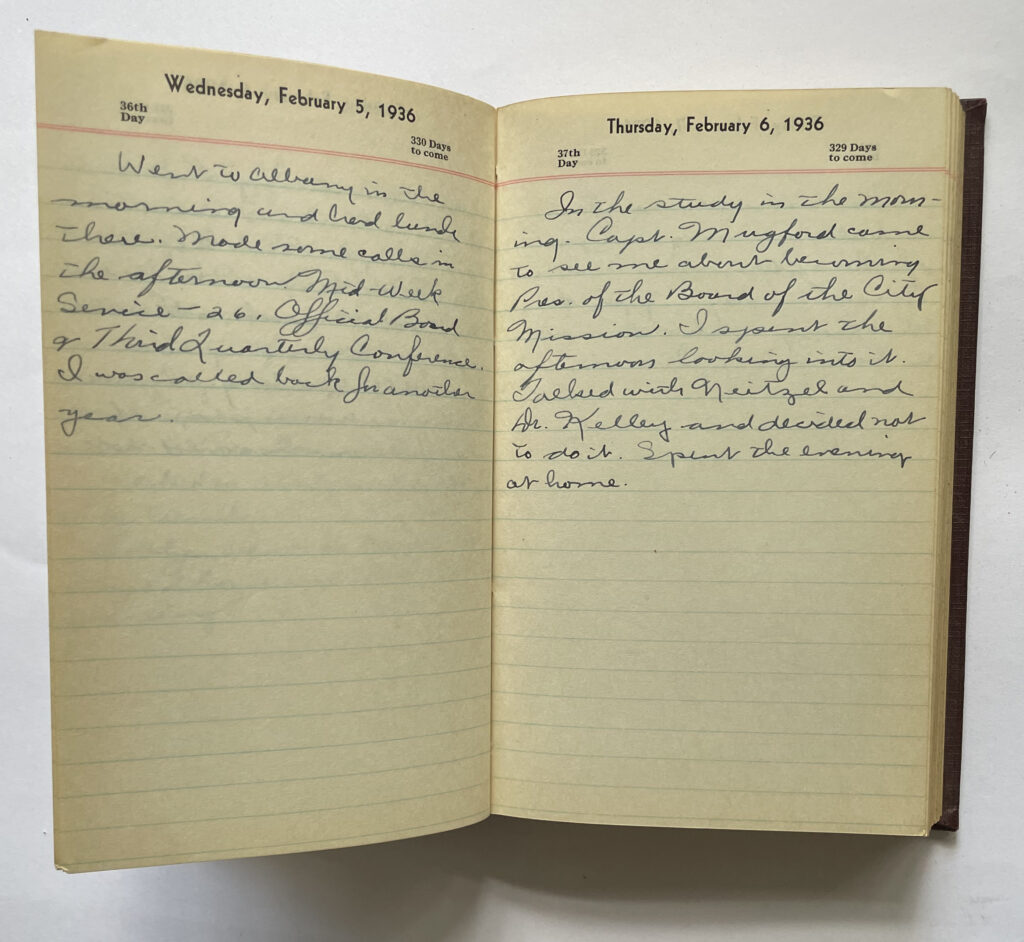

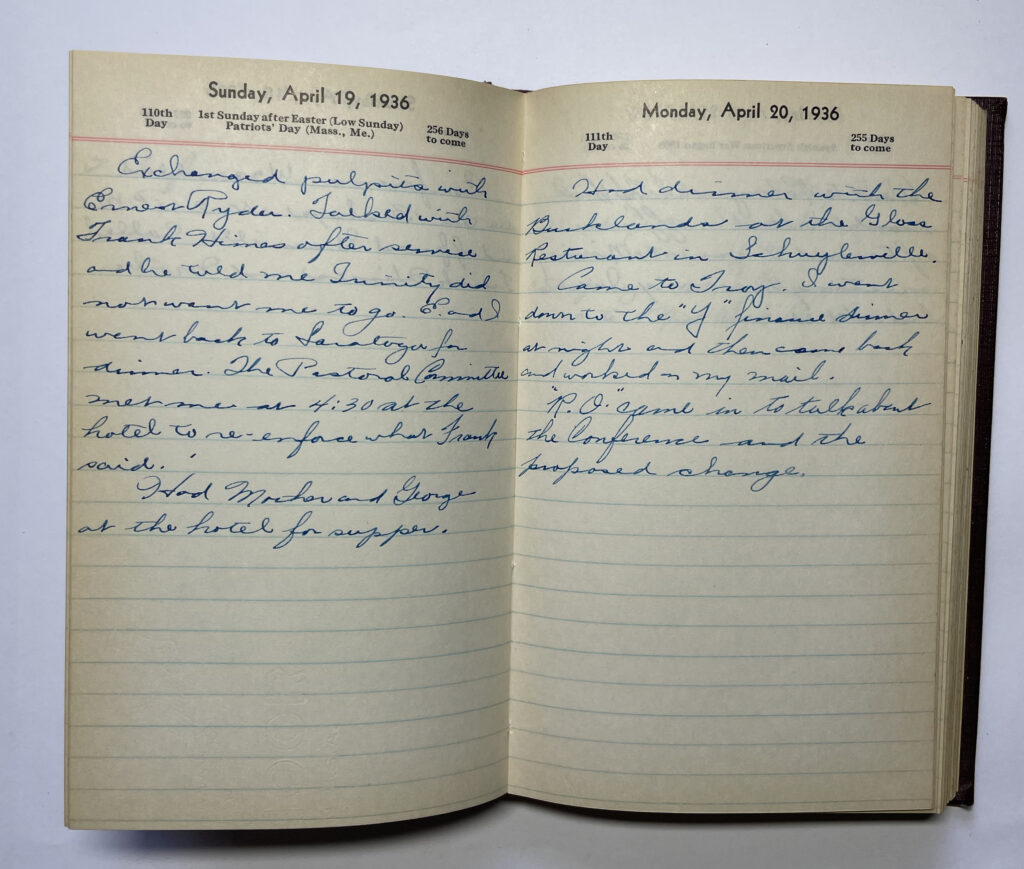

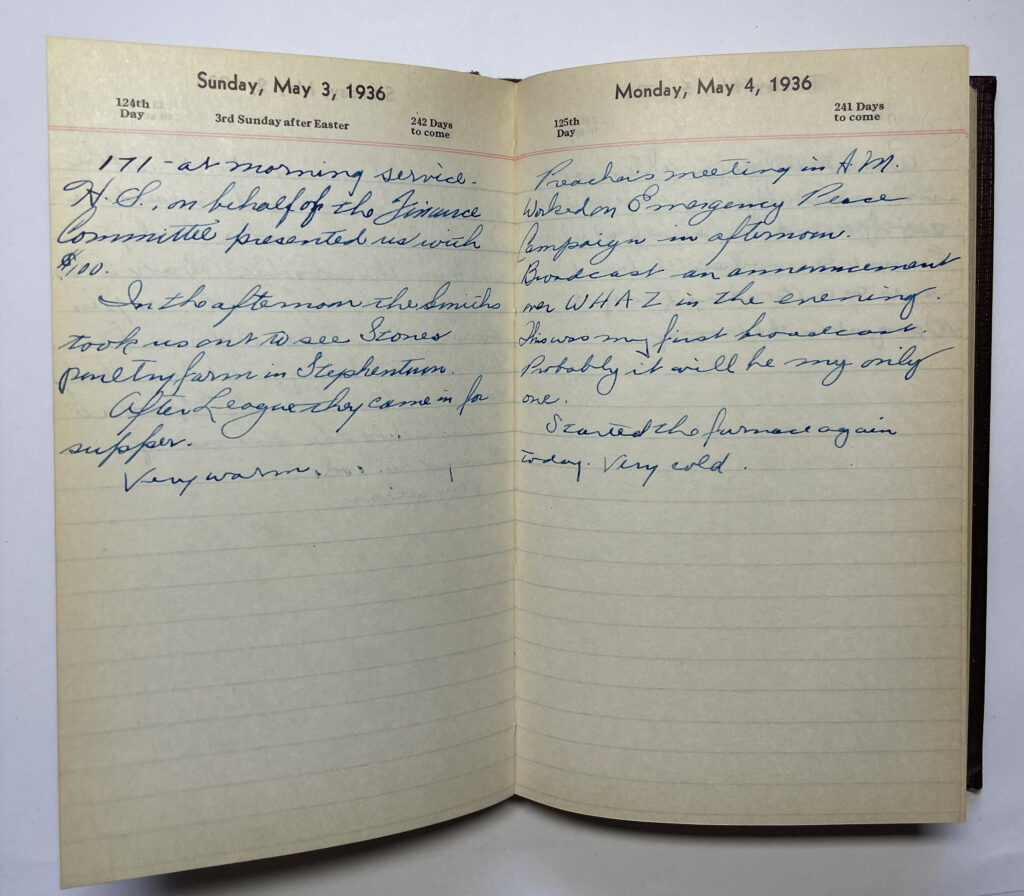

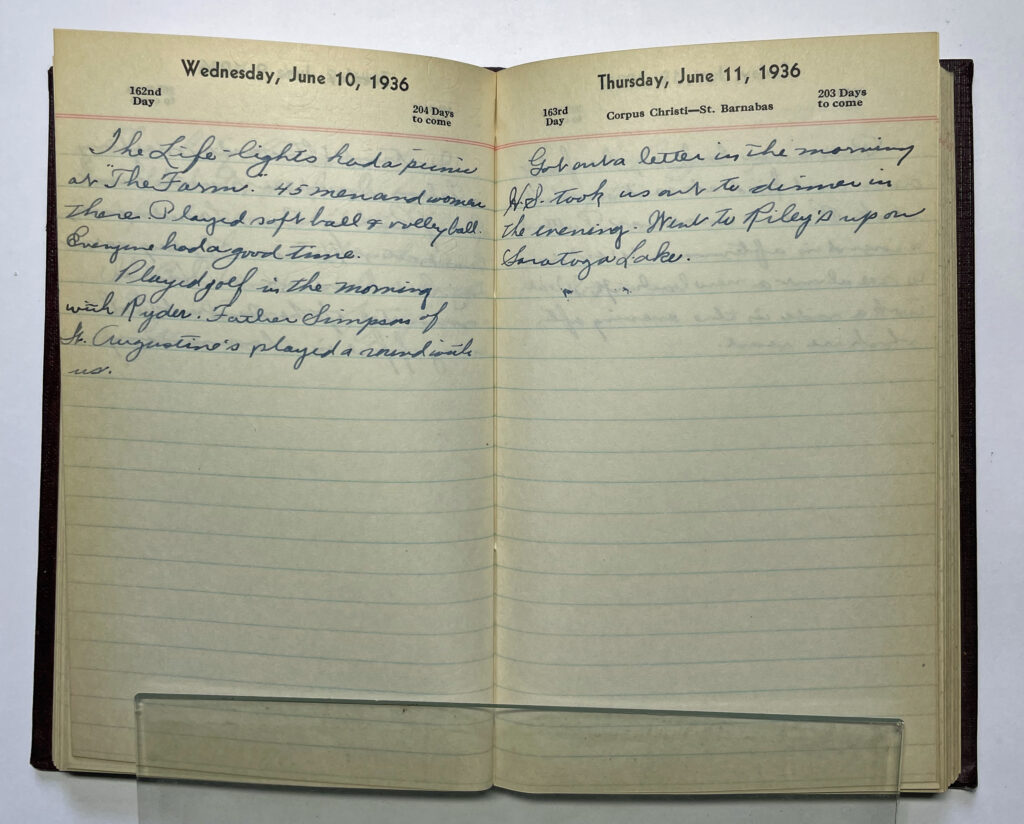

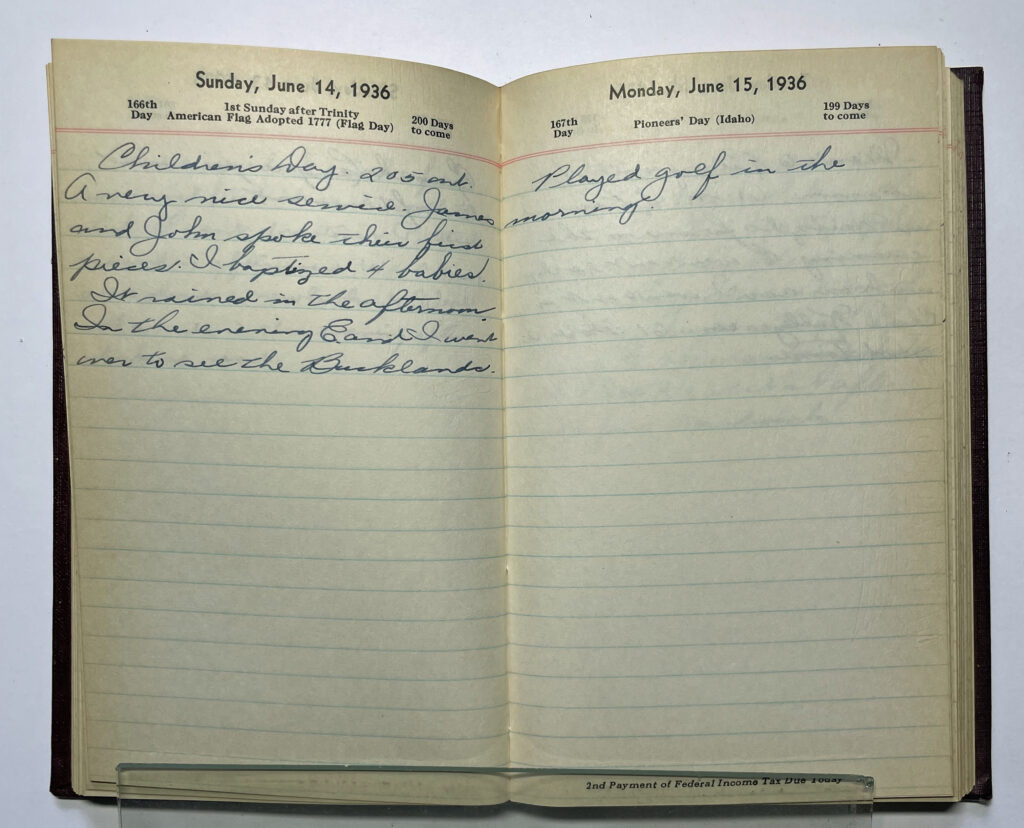

The photographs below are pages from Harold’s personal diary book of 1936 when he was pastor at Trinity Church. They reflect ‘days in the life of a pastor’, what he typically experienced and did on a daily basis as a pastor. He visited parisoners at home, in hospitals, and at his office at the church. He also provided sermons not only at his church but at other churches within and outside of the Methodist Episcopal circle and provided prayers and talks at business gatherings. He also met with various community groups and organizations.

Thursday, January 16, 1938: Worked in the study all morning. In the afternoon I spoke at Mrs. Thomas’ prayer group which met at Mrs. Swensson’s. Walked up and back. Afterwards went down and got a haircut.

The Life Lights put on a sauerkraught supper. I worked in the kitchen and had a grand time. There was a very poor crowd at the supper. I think they made around $5. Another beautiful day. Just cold enough to be snappy.

Friday, January 17, 1938: Went to the bank this morning and borrowed $350 to pay up the bills that have accumulated. We have resolved to follow a ‘pay-as-you-go” policy from now on. It hardly seems possible that all unconsciously anyone would get so far behind.

The new bulletin came early in the afternoon and I spent the rest of the day arranging to have it hung. Took a short walk with Evelyn and the boys.

Had a discussion group until 8. Then came home and wrote and read.

A beautiful, clear day.

February 5, 1936: Went to Albany in the morning and had lunch there. Made some calls in afternoon. Mid-week service – 26 (attended). Official Board & third Quarterly Conference. I was called back for another year.

February 6, 1936: In the study in the morning. Capt. Mugford came to see me about becoming Pres. of the Board of the City Mission. I spent the afternoon looking into it. Talked with Neitzel and Dr. Kelley and decided not to do it. Spent the evening at home.

Sunday May 3rd: 171 – at morning service. H.S. on behalf of the Finance Committee presented us with $100. In the afternoon the Smiths took us out to see Stones poultry farm in Stephentown. After League they came in for supper. Very warm …

Monday May 4th: Preacher’s meeting in AM. Worked on emergency Peace Campaign in afternoon. Broadcast an announcement over WHAZ in the evening. This was my first broadcast. Probably it will be my only one. Started furnace again today. Very cold.

The right hand photograph, taken from the same 1936 year diary, contains two pages for Sunday, April 19, 1936 and Monday, April 20, 1936.

Sunday April 19: Exchanged pulpits with Ernest Ryder. Talked with Frank Hines after service and he told me Trinity did not want me to go. E. And I went back to Saratoga for dinner. The Pastoral Committee met me at 4:30 at the hotel to re-enforce what Frank said. Had Mother and George at the hotel for supper.

Monday April 20: Had dinner with the Bucklands at the Gloss Restaurant in Schuylerville. Came to Troy. I went down to the “Y” finance dinner at night and then came back and worked on my mail. “R.O.” came in to talk about the Conference and the proposed change.

The two photographs below also depict activities in Harold’s daily life in 1936. The left hand photograph provides his activities on June 14th and 15th. The right hand photograph provides his observations on his activities on June

Sunday June 14: Children’s Day. 205 att. A very nice service. James and John spoke their first pieces. I baptized four babies. It rained in the afternoon. In the evening E and I went over to see the Bucklands.

Monday, June 15: Played golf in the morning

Wednesday, June 10: The Life-lights had a picnic at the Farm 45 men and women there. Played softball and volleyball. Everyone had a good time. Played golf in the morning with Ryder. Father Simpson of St. Augustine’s played a round with us.

Thursday, June 11: Got out a letter in the morning. H.S. took us out to dinner in the evening. Went to Riley’s up on Saratoga Lake.

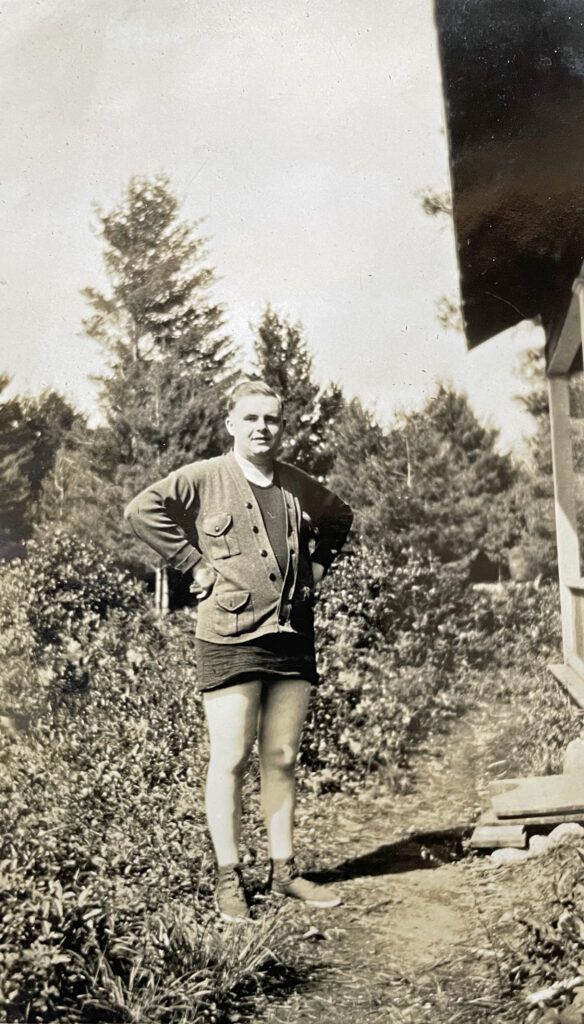

The following photograph was taken in 1934. Harold and Evelyn was dressed for a formal event.

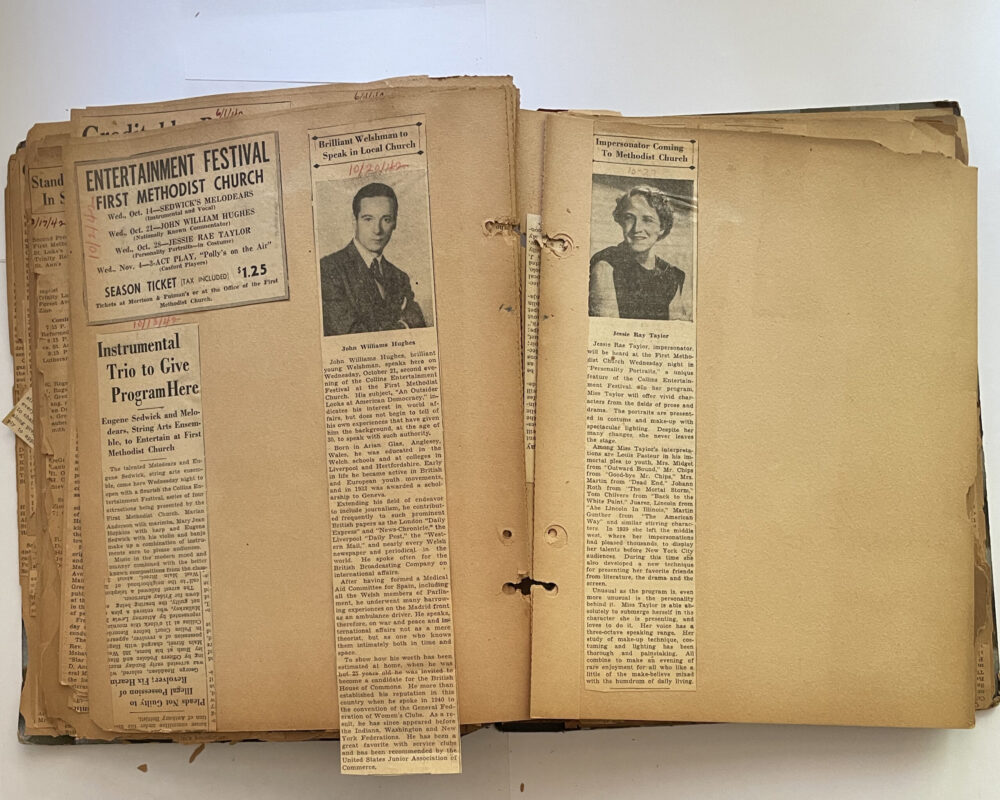

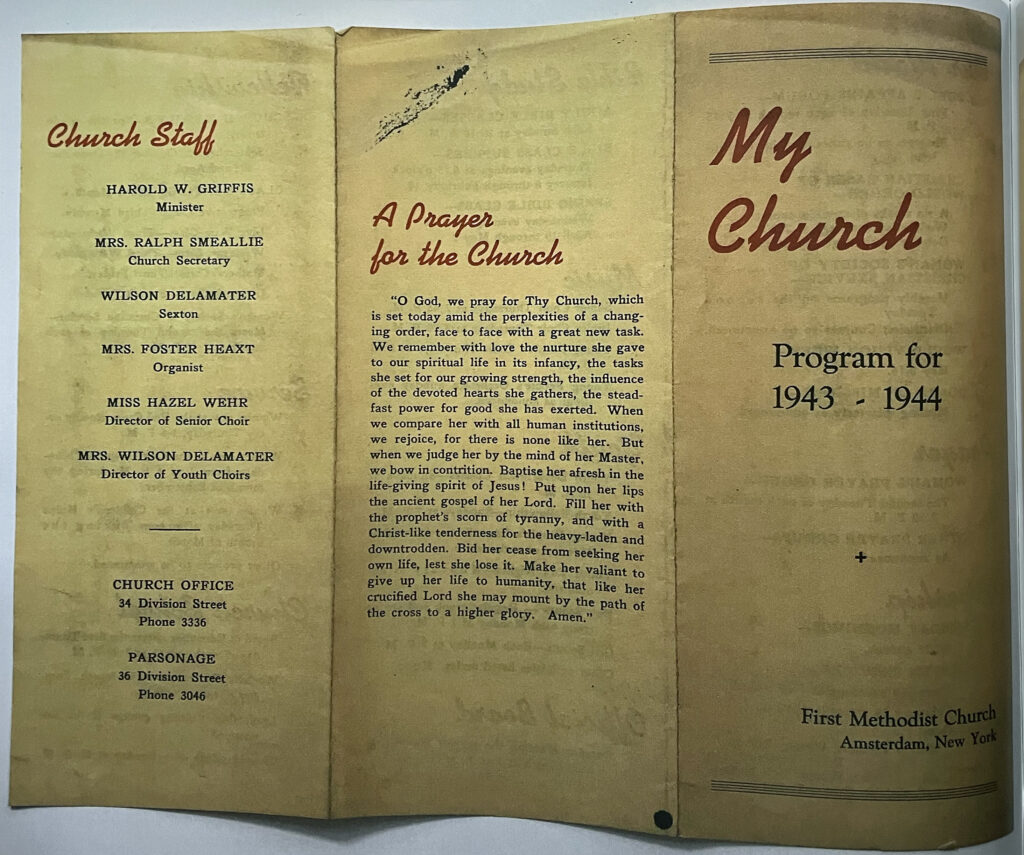

The following is a church program when Harold was pastor of the First Methodist Church.

Sources

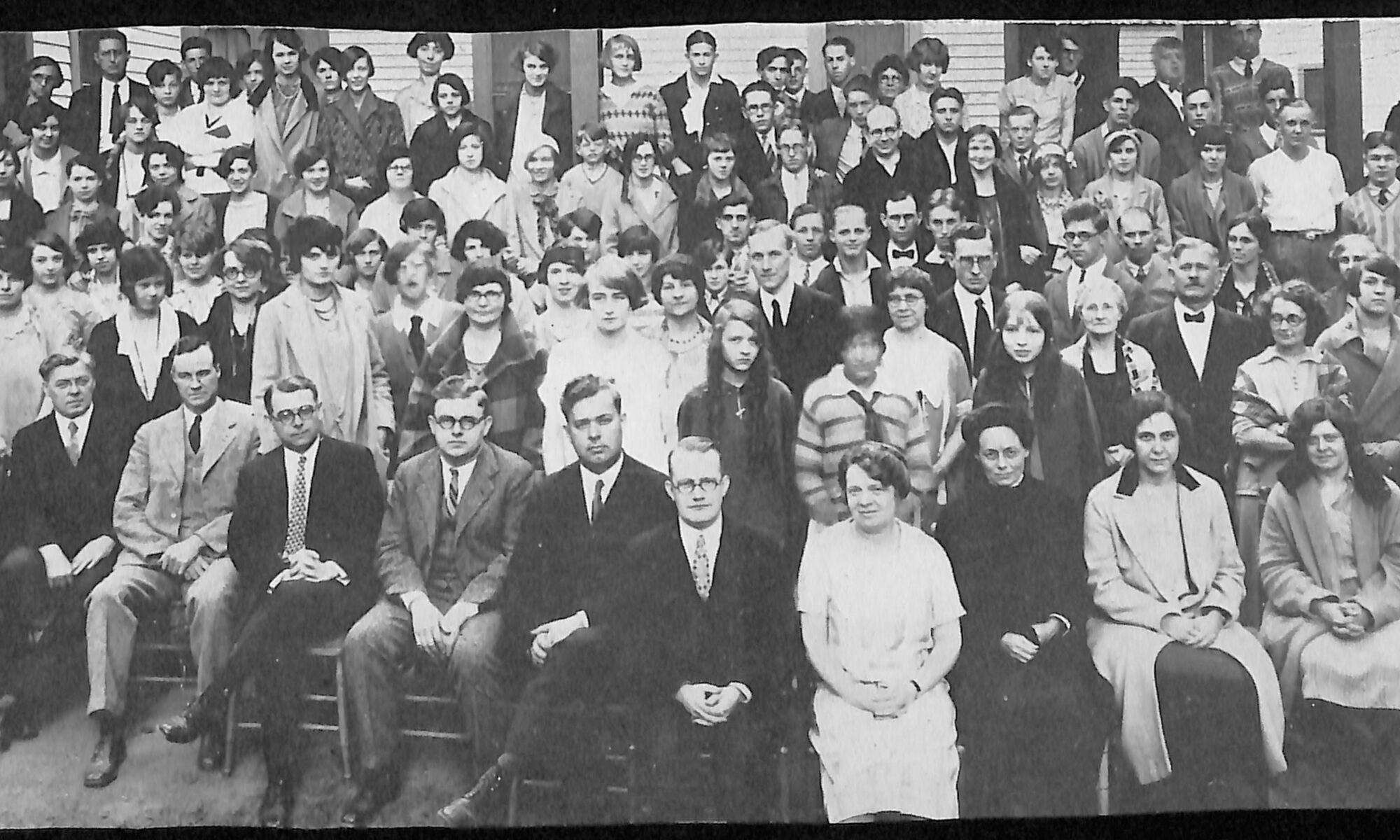

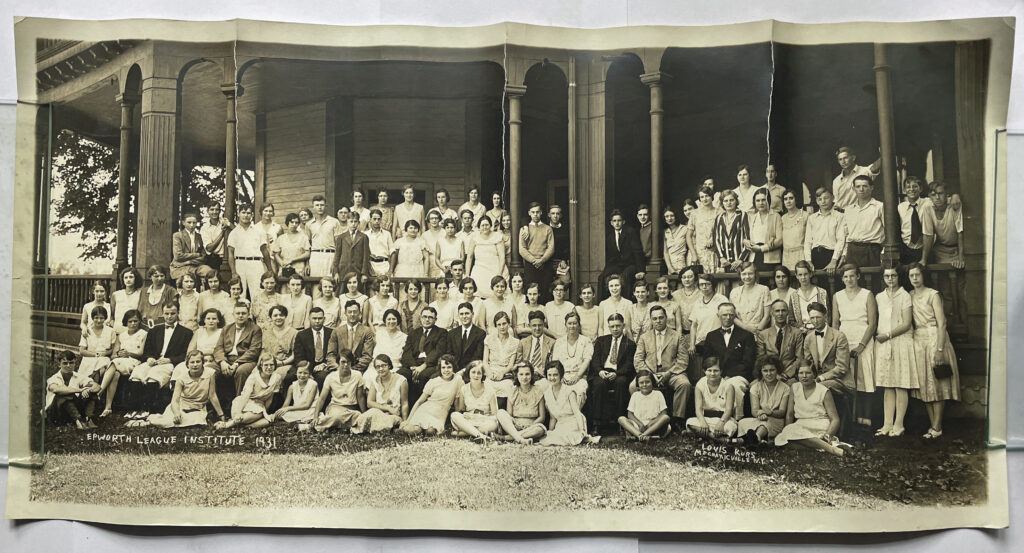

Featured Image at top of story: Group photograph of Epworth League participants and faculty win 1930. Harold Griffis, Dean, in the center of the front Row. Evelyn is also in the photograph in the top row fourth from the left. Click for larger view.

This story is partly based on material from a book originally published on the life of Harold Griffis as a Methodist minister, see James F. Griffis (Ed.), Sermons, Notes and Letters of Harold William Griffis, Self published, Blurb: Oct, 2018

[1] Phyllis McGuire, Williamstown Methodists Reflect on Church’s History, iBerskshires.com, November 28, 2010

[2] Harold Griffis, Dean of Pultney Institute, Epworth League, The Granville Sentinel., December 28, 1928, Page 6

[3] Rev. James A. Fenimore, A Church on the Edge of an Apocalypse, Term Paper, December 30, 1998 referenced at Christ Church UMC, Troy, New York website. Page 5-6

See also: Hillman, Joseph, The History of Methodism in Troy, N.Y. NewYork: Moss Engraving Company, 1888

[4] Hillman, Joseph, The History of Methodism in Troy, N.Y. NewYork: Moss Engraving Company, 1888, Page 102

[5] Hillman, Joseph, The History of Methodism in Troy, N.Y. NewYork: Moss Engraving Company, 1888, Page 102

History of Trinity United Methodist Church, website, accessed 8 Jun 2021