The story of the Fliegel and Sperber families immigrating to the United States reflects the influence of push and pull factors that affected the larger migratory patterns of Germans in the late 1840’s and the early to mid 1850’s. The Fliegel’s, migrated in 1848 and 1855. John Sperber, who married one of the Fliegel sisters, immigrated to the United States in 1852.

A note on Retracing Their Journey

“Concrete” facts about the journey of the Fliegel Family to the United States are only hinged on a ship manifest list of passengers, U.S. and New York State census documents, German marriage and birth documents and family trees that I have been able to reconstruct. Reading a list of facts is literally accurate but lifeless. We need details to help spark our imagination. Writing family history is challenging because we need both accuracy and imagination.

The bulk of reconstructing their story of immigrating to the United States is based on viewing their lives within various levels of historical context. Their unique, personal stories are limited to a few isolated historical documents. While the ultimate goal would be the ability to tell their unique story, we do not unfortunately have all the facts to reconstruct their lives.

Their stories of life, while unique, were lived within the parameters of broader levels of history: immigration trends and population movements, major historical events, push and pull factors of economic and social development, the development and the existence of rail and shipping lines and other structural and cultural parameters. While they had free will to choose unique and innovative solutions to the things they faced in life, it is highly probable that many of their decisions were influenced and limited to what they had on hand, the various historical, social and environmental forces that shaped their decisions and what they knew from their social networks.

Their stories are also perhaps similar to historical depictions of daily life in the mid 1800s of many of the German immigrants. While their stories might be similar to many of their fellow German immigrants, getting from point “A” to point “B” required “free will” in planning the logistics of their trip, managing their material resources, determination and drive, the ability to react to unforeseen situations and luck.

With the skeletal outline of facts regarding their basic points in life (birth, migration to America, residence in Johnstown, family structure, death and burial), I have tried to add historical context and content to create a meaningful explanation of their journey to America.

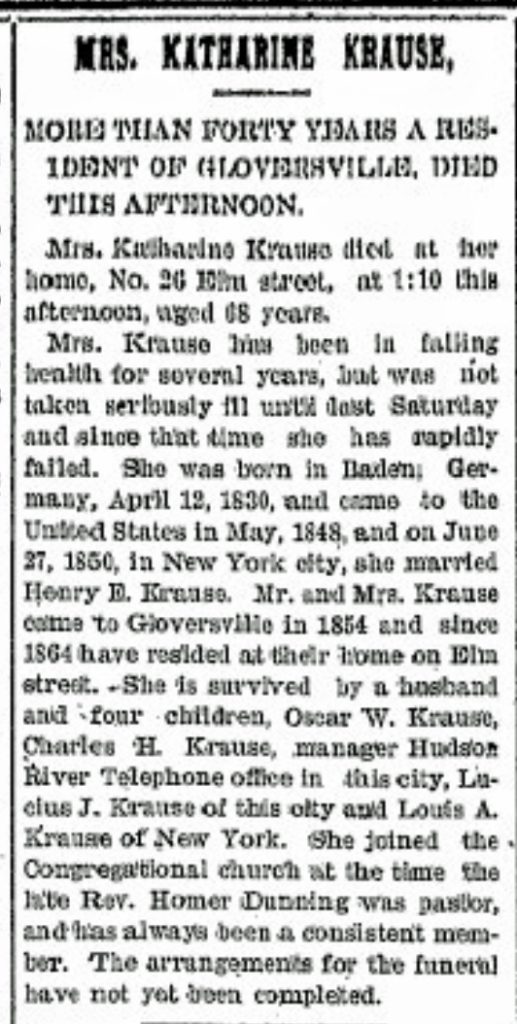

As indicated in the first story of this series, Harold Griffis’ maternal relatives were from the Baden Area of what is now Germany. Harold’s maternal grandfather was John Wolfgang Sperber and his maternal grandmother was Sophie Fliegel.

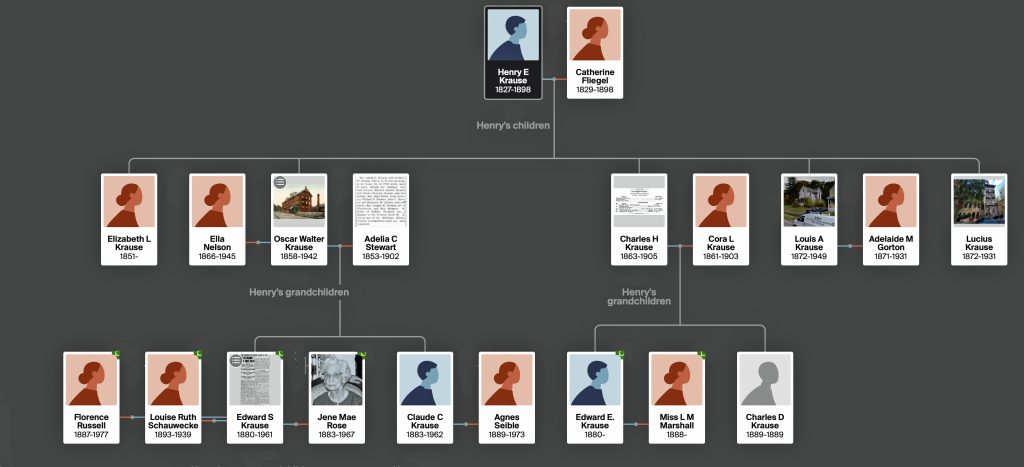

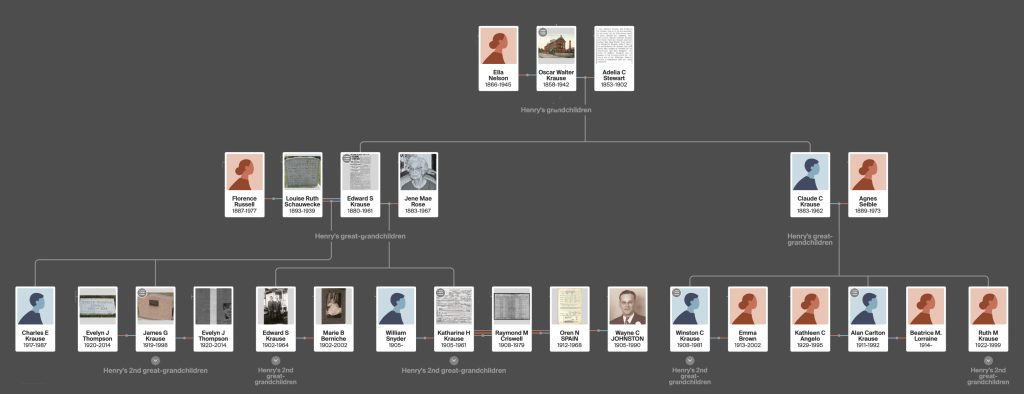

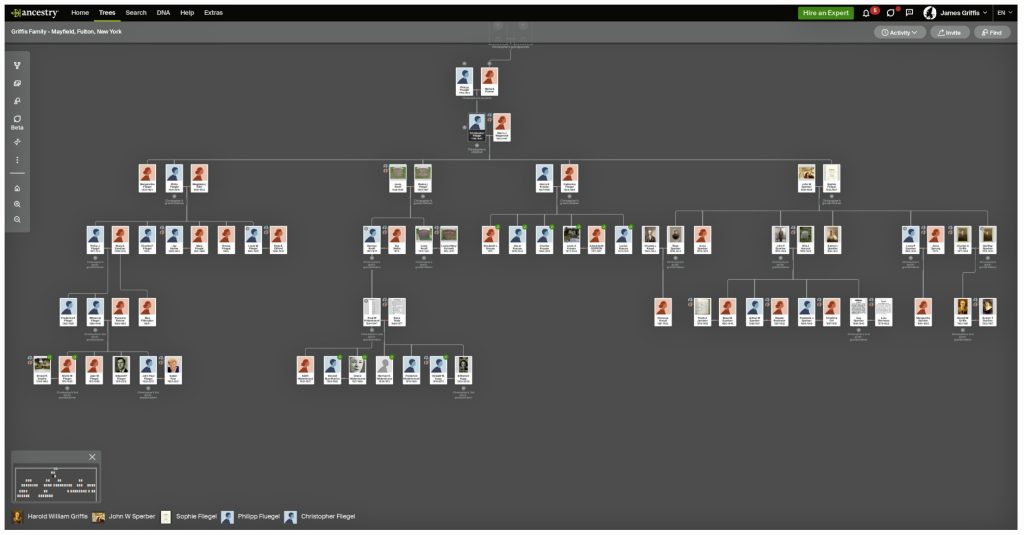

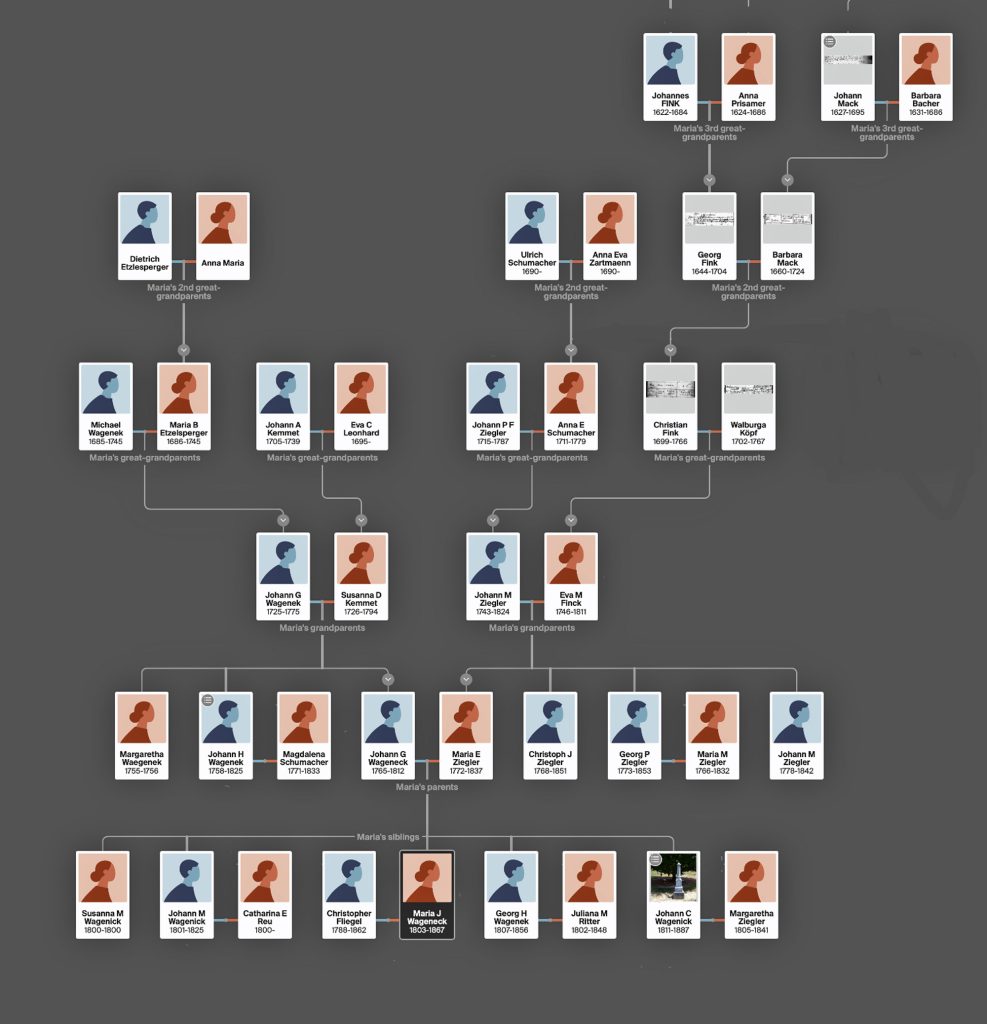

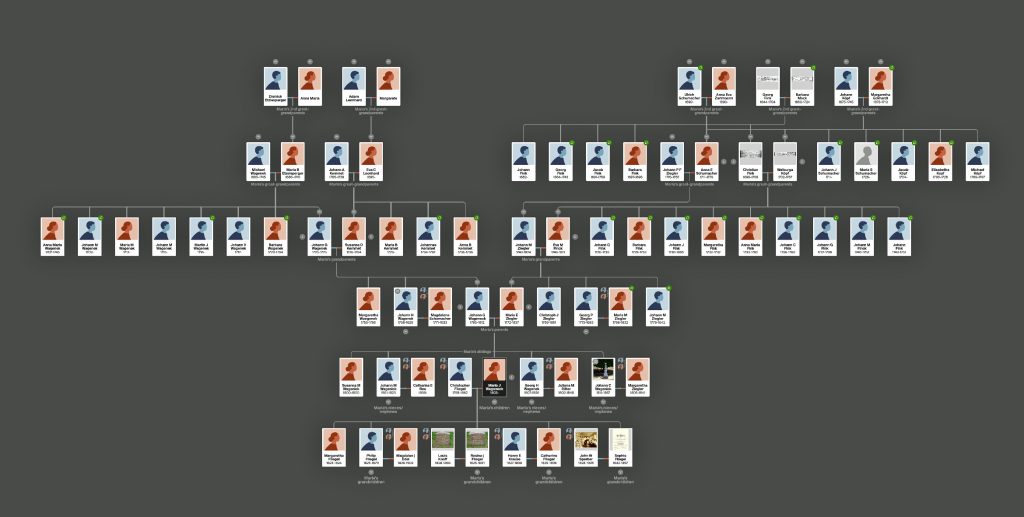

This story focuses on the arrival of the remaining five members of the Fliegel family. The family name of Fliegel is probably not a family name that many in my particular branch of the family will recognize. The four children of the Fliegel family have produced 16 grandchildren, 11 great grandchildren, and 14 great great grandchildren. and 16 great-great-great-grandchildren in the United States. The seventh generation has living members and, given privacy concerns, I do not have a firm fix on the number of members in this generations. However, I estimate that there are 23 members of the seventh generation that can trace their family lines back to Christopher and Julia Fliegel.

If I focus only on the direct family branch that stems from Christopher and Julia Fliegel through Harold Griffis, there are: 1 great grand child (Harold Griffis), 4 great2 grandchildren, 8 great3 grandchildren, 14 great4 grandchildren) and 7 living great5 grandchildren.

Since many of Christopher and Julia’s’ great-great-great grandchildren and their descendants are living, their generations are not listed in the following family tree.

Five Generations of the Fliegel Family

Related Stories and Pages

Click for larger view

See the related story “A German Influence” for more information on the immigration of the Speber, Fliegel and other families to the United States

See the first story on Catherine Fliegel leading the Way for her Family to immigrate to the United States

See an example of a steerage ticket and regulations governing steerage passage from Le Havre to New York City in 1854

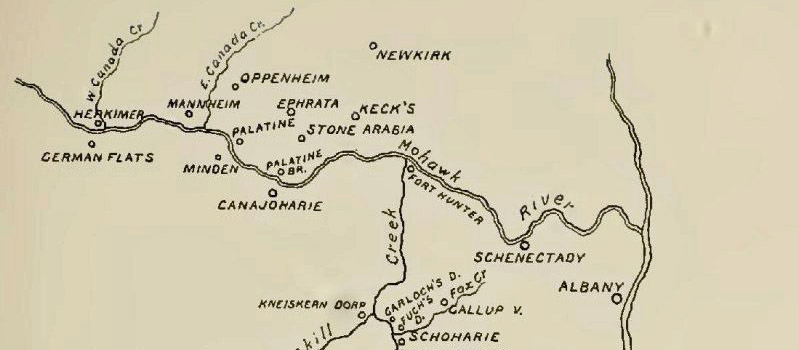

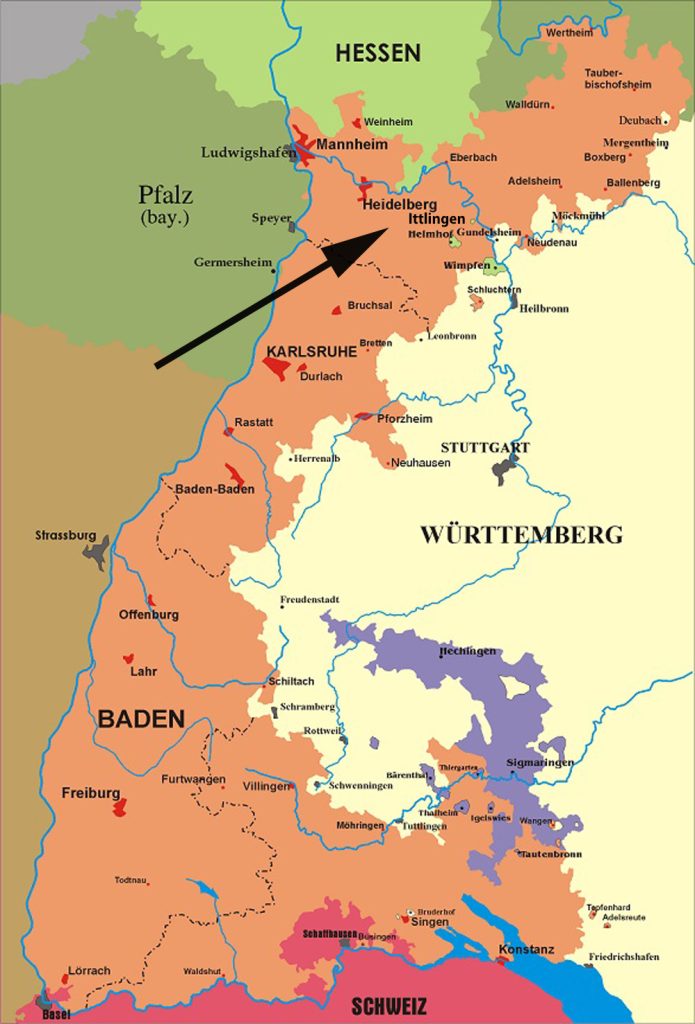

The Fliegel Family from Ittlingen, Heidelberg, Baden

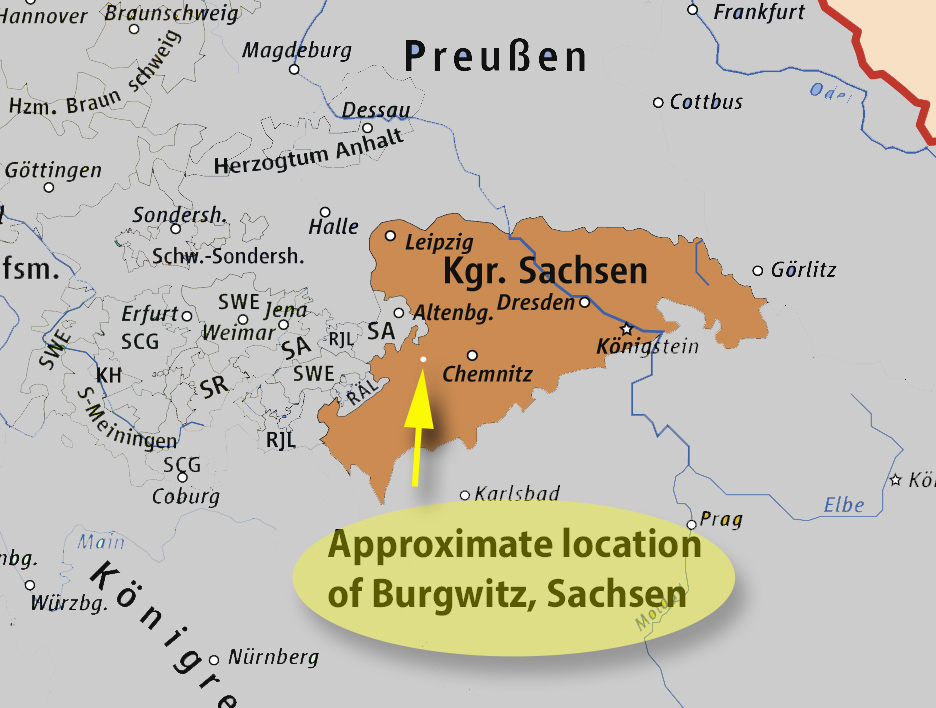

Christoph Fliegel (born May 26, 1789) and Maria Juliana Wageneck (born Dec 14, 1803) were married on July 16, 1818 in Evangelisch, Ittlingen, Heidelberg, Baden in a Lutheran ceremony. [2] Both were born and raised in the same town of Ittlingen.

Map of the Grand Duchy of Baden 1848 [3]

Both of their families had many prior generations that lived in Ittlingen and outlying areas of Heidelberg, Baden. Christoph’s family can only be traced back to his father. His father, Johan Philip Fluegel, lived in Bockschaft, Heilbronn, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

Maria Julia Wageneck’s family has a long documented history in the Baden area. Many of the relatives in the family tree depicted below were from the Ittlingen, Baden area. All of her known aunts and uncles and grandparents were from Ittlingen. Four of her eight great grandparents were from Ittlingen and the remaining were from nearby towns in Baden. Maria’s known great-great parents were also from Baden-Württenberg.

Six Generations of the Wageneck Family

I have also provided an expanded version of the Wageneck family tree that includes the siblings of Julia’s grandparents and prior generations of grandparents. It does not include the children of those siblings. Even so, it is a big family.

Julia Wageneck’s Family Tree: Grandparents and Their Siblings

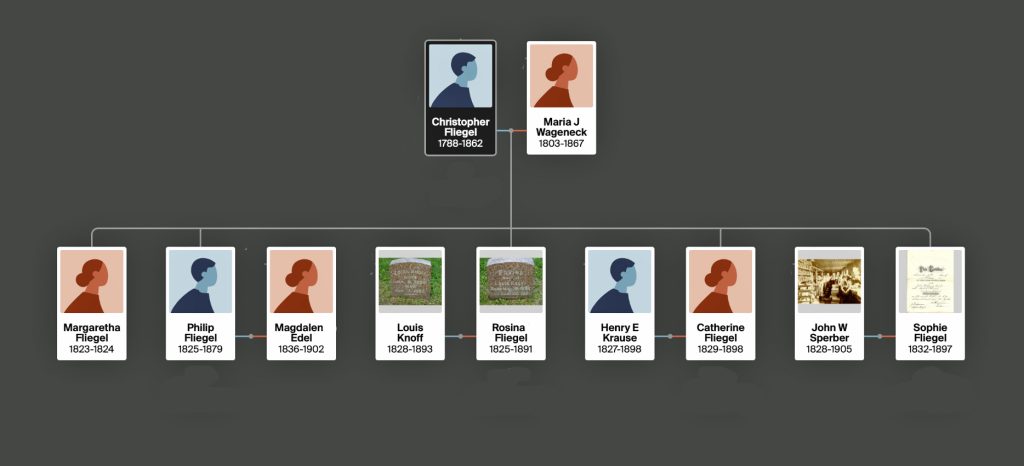

As reflected in the following family tree, Christopher Fliegel and Maria Julia Wageneck had five children. Their first child Margaretha, passed away before her first birthday (June 3, 1823 – May 19, 1824). The second child Rosina (Rose) was born on March 4, 1825. Their only son, Philip, was born shortly after Rose on December 22, 1825. Catherine was the next daughter, born on 12 April 1, 1829. Their fifth and youngest child, Sophie was born on October 28, 1832. [4]

The Fliegel Family from Ittlingen, Baden

Family Decisions to Immigrate to the United States

In 1855, Christopher (Christoph) Fliegel and his wife Maria Juliana Wageneck, along with their three remaining young adult children, made a major life altering decision to emigrate to the United States. This must have been a hard but perhaps rational decision to make for the entire family. They essentially left their lives, household possessions, and extended family in Baden-Württenberg to follow the migratory path that their daughter and sister, Catherine (Fliegel) Krause, had taken seven years prior.

As discussed in the previous stories referenced above,

“(f)or the typical working people in Germany, who were forced to endure land seizures, unemployment, increased competition from British goods, and the repercussions of the failed German Revolution of 1848, the economic and political prospects in the United States seemed bright. It also soon became easier to leave Germany, as restrictions on emigration were eased.” [5]

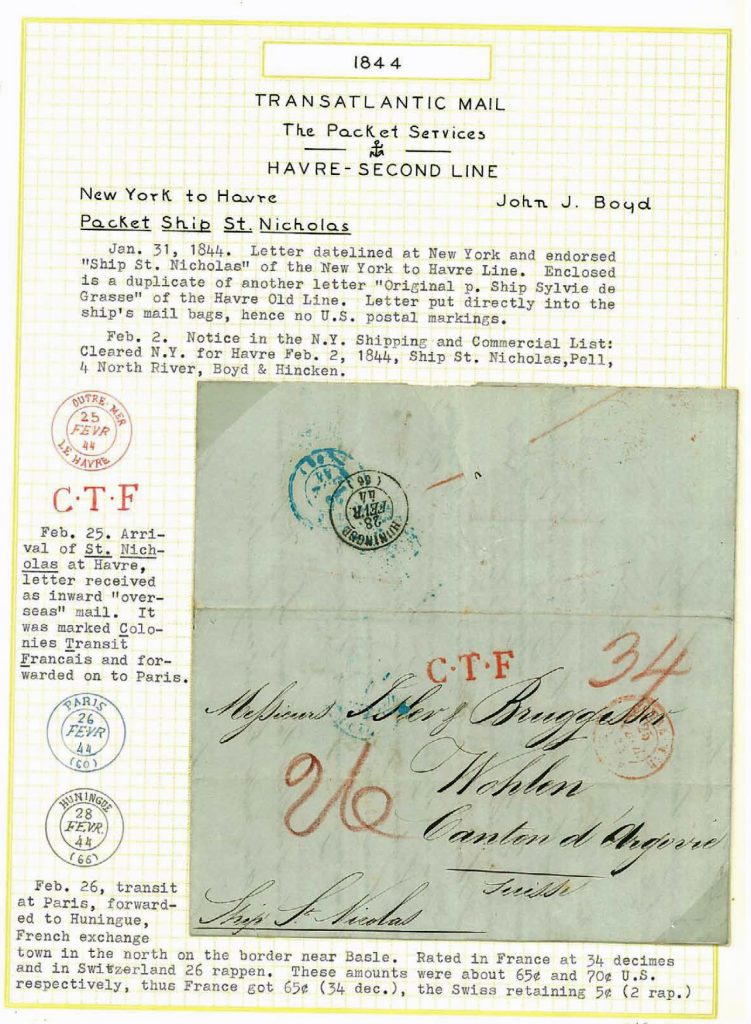

Transatlantic Mail in the Mid 1800’s

Samples of Transatlantic Mail Envelopes on Packet Ships 1825 – 1847 [6]

The narratives and date stamps associated with each of the envelopes reflects the precarious but reliable journey that transatlantic mail experienced in the mid 1800s.

“The transmission of an overseas letter can be described as a process, which is sliced into several independent parts: how long it took for the writer to send the letter after writing it, how long it took for the local system (coffee house, forwarding agent, post office) to forward it to an ocean going vessel (if overseas mail), how long it took before the ship was ready to leave from the port, how long the sea journey was, and how efficiently the letter was forwarded and finally delivered at the other end. Naturally, the duration of the whole process also depended on the frequency of the mail transport available. “ [7]

“After soldiers, immigrants produce the largest amount of letters. … (T)he letters don’t seem to be very concerned with documenting the world around them, they almost resemble a project serving an end.” [8]

Immigrant letters were focused on maintaining relationships with individuals that were important community ties and part of their identity from their old world. Immigrant letters often focused initially on their first project of material goals and establishing a life in the new world. Then they may moved on in their correspondence to the second project of continuity of service with their family and community: getting relatives or friends to join them by providing experienced advice on planning and occupational opportunities.

Perhaps Catherine’s positive experiences in the new land and the knowledge of the hardships her family faced at home were conveyed in letters to her family in Baden, similar to what many other German immigrants did after migrating to the United States. Sending letters back and forth between the United States and the German states was not as difficult as imagined.

“Bremen in effect became America’s continental post office. In 1848 the Ocean Line ships carried 80,000 letters to Bremen, and five years later the number had risen to 350,000.” [9]

While we do not have any letters between the family members to document this communication, it obviously is beyond coincidence that the remaining members of the Fliegel family would relocate seven years later to the Gloversville – Johnstown area.

“(German) immigrant identities are influenced less by the time they have spent in the receiving country than by critical political events that affect both the country of origin and that of destination. Such events can reactivate migrant’s identifications with their homeland. Immigrant networks filter this dual process in that they can facilitate migrants’ integration while also reminding them of people and places left behind.” [10]

“The German migration to America has often been referred to as a family migration, one in which entire families moved together to the New World (including older parents traveling along with several grown or nearly grown children).” [11]

The impetus for moving their entire family may have been influenced by the information the Fliegel family may have received in correspondence with Catherine Fliegel living initially in New York City and then in Gloversville, New Yorker. Her accounts and assessments of living in the United States coupled with the push factors they experienced in the Grand Duchy of Baden may have led to their collective decision to make the big move.

Christopher was 60 years old and Juliana was in her late fifties when embarked for America. This is a point in one’s life where one hopefully has made their mark in life and has the good fortune to enjoy what they are doing, being part of a community and the fruits of their working life. Their three children were in their 20’s and early 30’s, an age that one is attempting to find a place in the world and perhaps start a family.

While we have no historical knowledge of the personal economic well-being of the Fliegel family, their socio-economic profile probably reflected that of the majority of German immigrants coming from Baden at the time. The families with the highest emigration rates were those middle-class artisans or farmers who were more skilled than they were wealthy. The environment in the homeland did not provide adequate compensation and an adequate standard of living. They had a lot to gain from the move. The wealthiest and the poorest in Baden had low emigration rates, while the middle class had the highest representation. [12]

“Once established in their new home, these settlers wrote to family and friends in Europe describing the opportunities available in the U.S. These letters were circulated in German newspapers and books, prompting “chain migrations.” By 1832, more than 10,000 immigrants arrived in the U.S. from Germany. By 1854, that number had jumped to nearly 200,000 immigrants.” [13]

Except for the great leap of faith in crossing the ocean, German immigrants tried to minimize their risks by relying on information and resources that drew upon personal social ties and community resources on both sides of the ocean to ease their entry into a new society and economy. The Fliegel family’s planned exodus from Germany is a classic example of ‘chain migration’, relying on the prior experience of their daughter Catherine Fliegel. [14]

“Much more decisive for the migration process than agents, guidebooks, or emigration societies were families or lone individuals, sometimes accompanied by relatives, friends, or neighbors, but without a common treasury or any formal organizational framework. The risks involved in such an undertaking were greatly reduced through chain migration, which meant the immigrant had the choice of an initial destination where one already had personal contacts, family, and friends who could provide temporary lodgings, arrange a job, and generally ease the shock of confronting a new society, culture, and economy” [15]

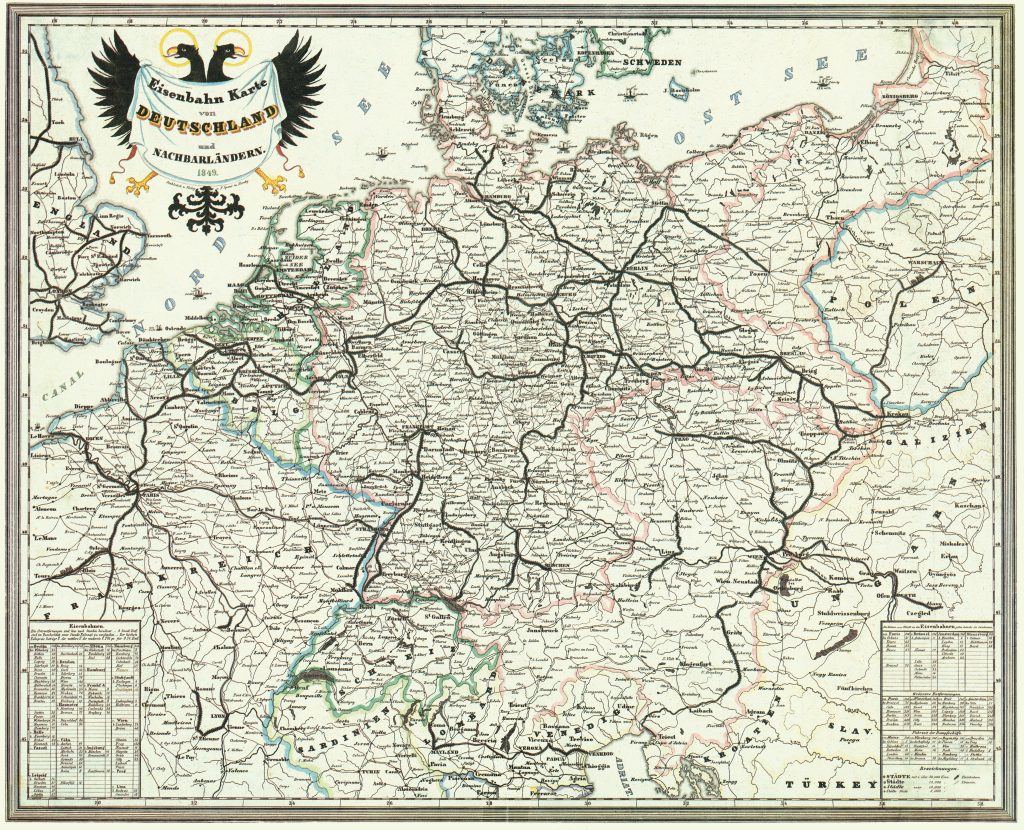

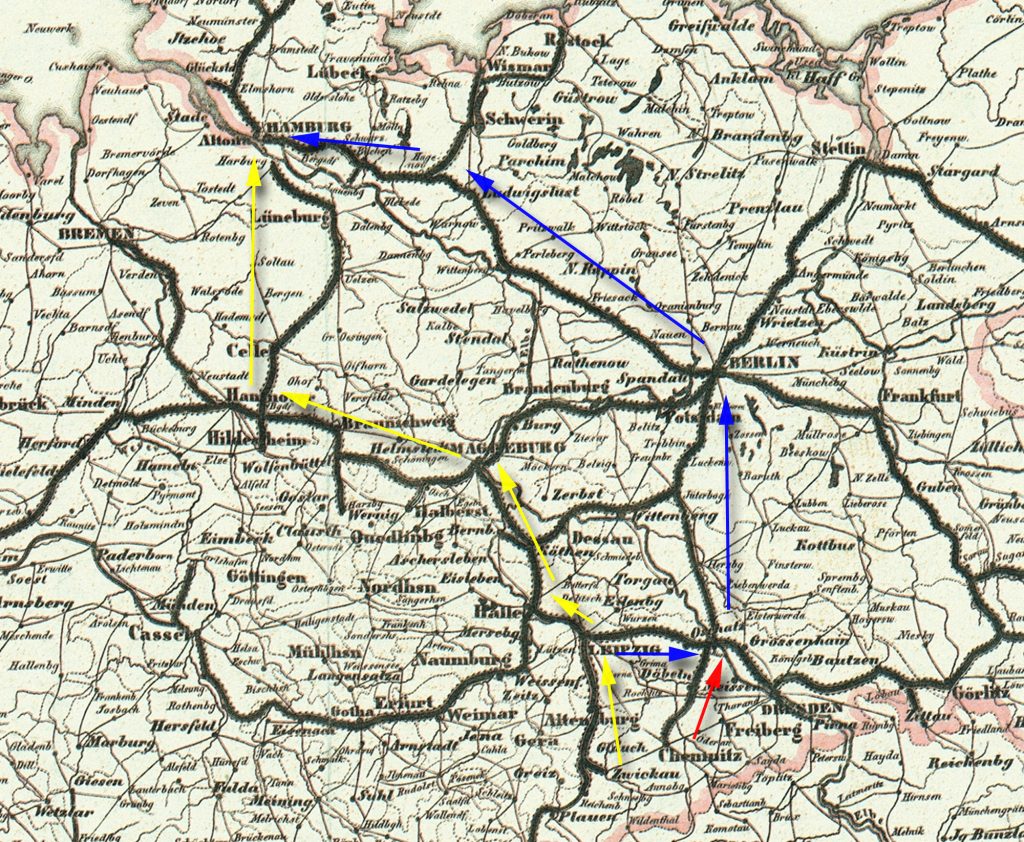

First half of the Immigration Journey: Reliance on Railways

In the first half of the 19th century, popular opinions, proposed strategies and technical specifications about the development of emerging railways in Germany were contested and varied widely. The political disunity of three dozen German states, a pervasive political wave of conservatism in governance, complicated negotiations on land ownership and the lack of agreement on the technical specifications of railway tracks and technology made it difficult to build railways. However, by the 1840s, trunk lines linked the major cities. Each German state was ostensibly responsible for the lines within its own borders. By the year 1845, there were already more than 2,000 kilometers (about 1,245 miles) of railway line in the three dozen states of Germany. Ten years later that number was above 8,000 (about 4,970 miles). [16]

“The railway was more than a new means of transportation with higher capacity. It opened new psychological, social, economic, political, and military dimensions, maybe comparable to the first flight across the Atlantic or the first landing on the moon. This new way of space-bridging and mobility led to a new perception of space, distances, speed and time. And this new means of transportation was not only something for big cities but could be used by everybody to go nearly everywhere and in all directions. The world shrank and the (German) multi-state system became an anachronism.” [17]

Initially, the family of five traveled probably traveled by wagon or carriage from Itlingen to the Heidelberg train station. It may have been approximately a 27 mile ride. It was the first stop of many along their way.

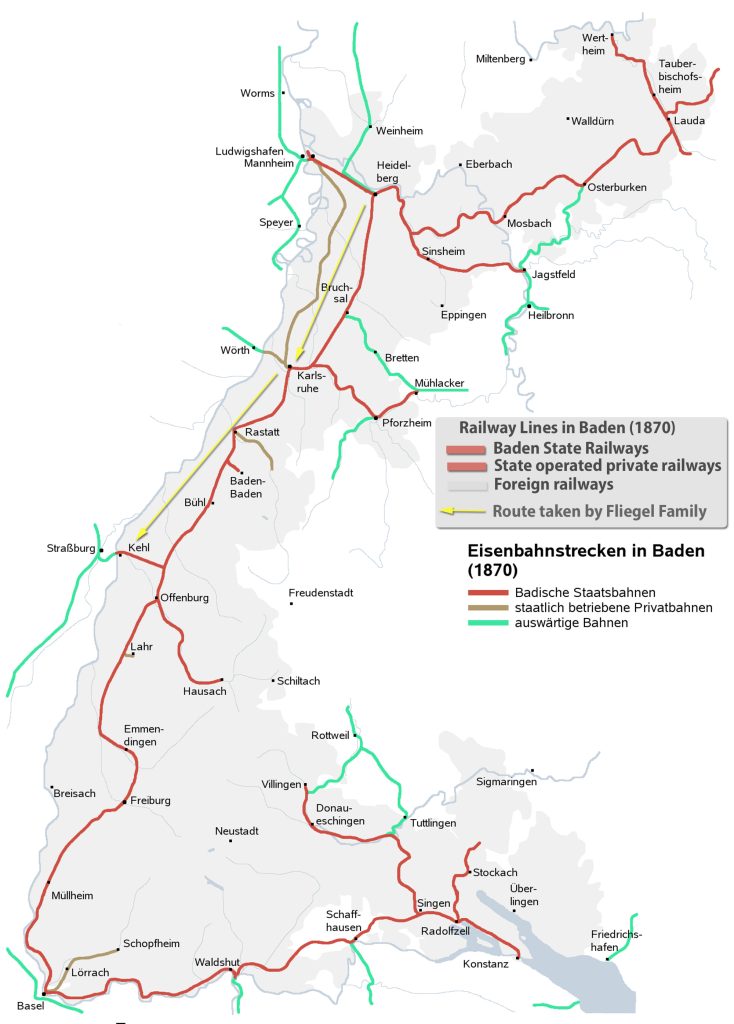

The family as well as their daughter Catherine were fortunate to have access to and enjoy the benefits of the fast growing Grand Duchy of Baden State Railway. It was a state owned railway founded 15 years before their journey in 1840. The Baden State Railway provided an all-important north–south transportation axis within Baden that connected areas along the Rhine River and connected with railways in France and neighboring German states. [18]

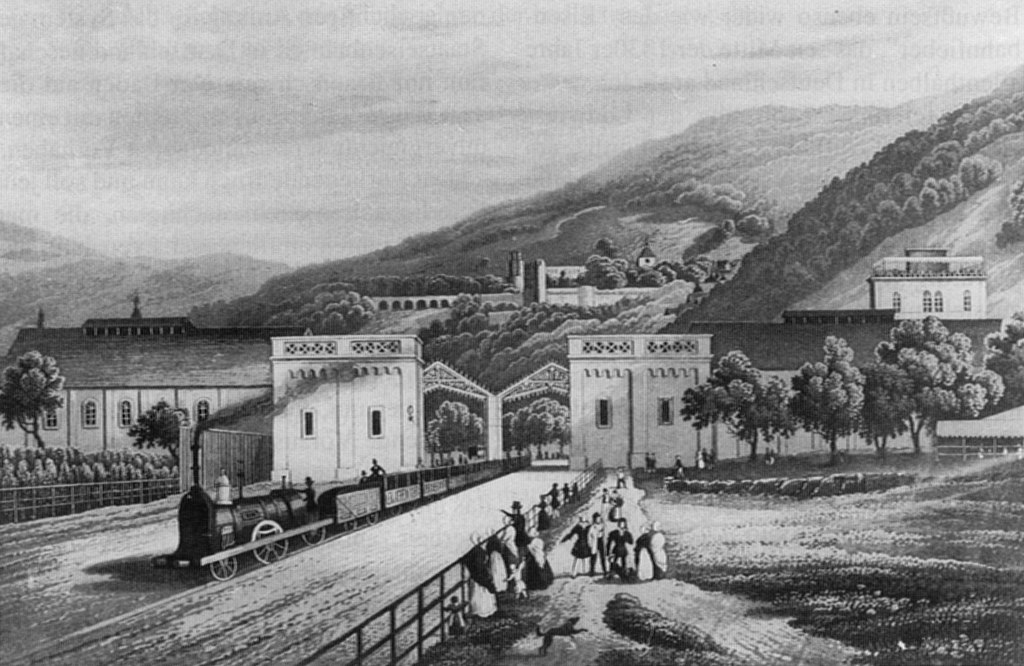

Heidelberg Rail Station 1840

It was the second German state after the Duchy of Brunswick to build and operate railways at state or government expense. In order to avoid the loss of trade routes to the neighboring French province of Alsace, the Duchy of Baden invoked legislation that laid the groundwork for the creation of a railway company to plan and construct a railway from Basle to Strasbourg in 1837. [19]

The first route, called the Baden Mainline, was built in sections between 1840 and 1863. All of the sections that Catherine and the remainder of her the Fliegel family required to travel to Strasbourg were completed by 1855. [20]

The first section between Mannheim and Heidelberg was put into service in September 1840. Other sections were completed in successive years. The section from Heidelberg to Karlsruhe was completed in 1843. Offenburg was linked to the railway system in the following year 1844. The rail branches to Kehl and Baden-Baden were opened in 1844 and 1845 respectively. Train track was added to Freiburg in 1845, to Schliengen in 1847, Efringen-Kirchen in 1848 and Haltingen in 1851. [21]

The Baden railway lines were initially laid to the 1,600 mm (5 ft 3 in) width track. After it turned out that all the neighboring German states had opted for 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 .5 in) standard gauge rail, the Baden State Railways rebuilt all their existing routes and rail stock to standard gauge within just one year during 1854 and 1855. [22]

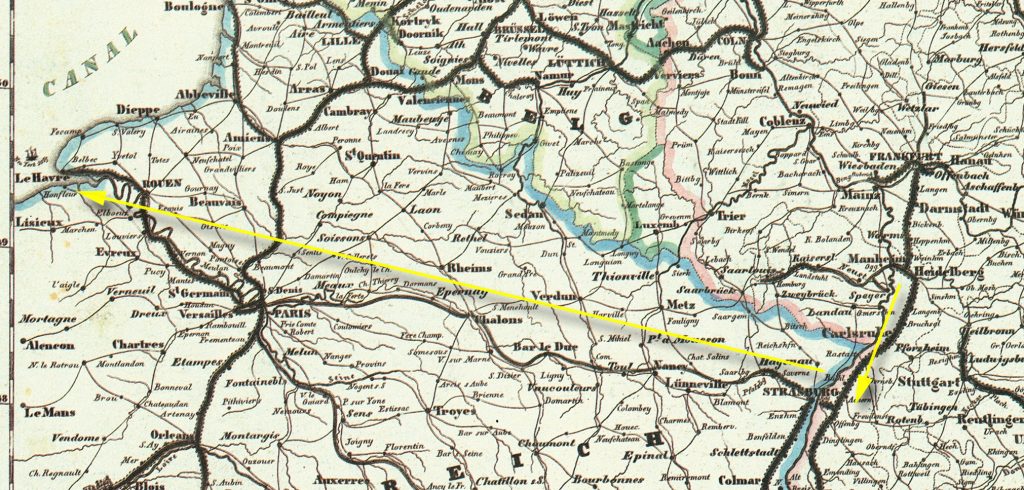

The Fliegels probably traveled on the Baden Mainline from Heidelberg to the Kehl spur. (see map below). Since there was no railway bridge in 1855 over the Rhine to Strasbourg in France, they probably took a boat across the Rhine to the Strasbourg train station. [23]

The Grand Duchy of Baden Railway System in 1870

Click for Larger View

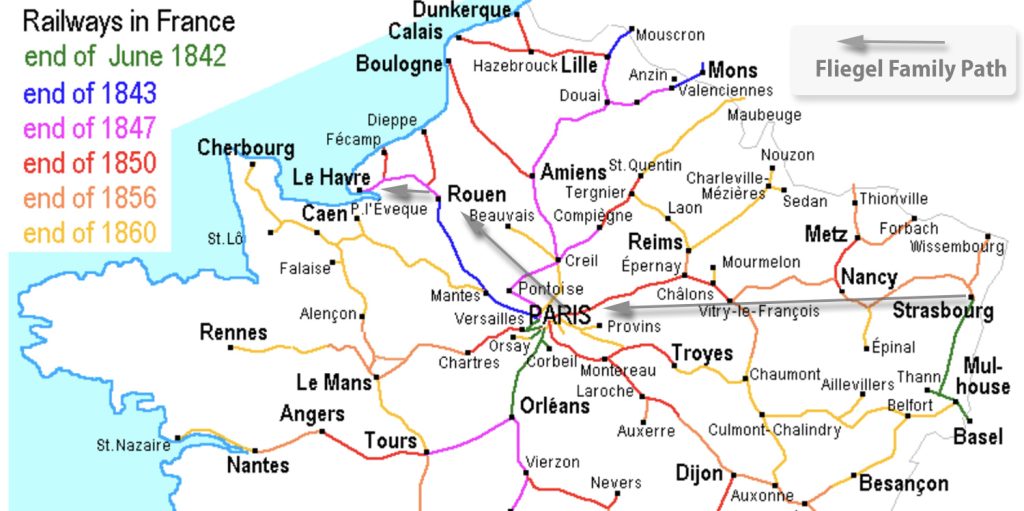

The Fliegel family’s journey from Heidelberg to Le Havre may not have been as demanding as Catherine Fliegel’s experience in 1848. Depending on their saved wealth as a family to afford rail travel, the family was able to enjoy the benefits and efficiency of two French rail lines to complete their journey to the Le Havre port. As early as 1854, trains travelled at a commercial speed of about 37 miles per hour, as compared to four miles per hour for the stage coaches of 1840. [24]

While the railway from the Paris–Strasbourg rail line had already been planned in 1833 and its route had been identified in 1844, the first section of the railway line was finally opened in 1849, a year after Catherine’s voyage. This first section connected Paris to Châlons-sur-Marne (see map below). In 1850 a line from Nancy to Frouard and a line from Châlons to Vitry-le-François were completed. In the following year, a line from Vitry-le-François to Commercy was built as well as a line from Sarrebourg to Strasbourg was completed. Finally, in 1852 the sections between Commercy and Frouard, and the line between Nancy and Sarrebourg were opened. [25]

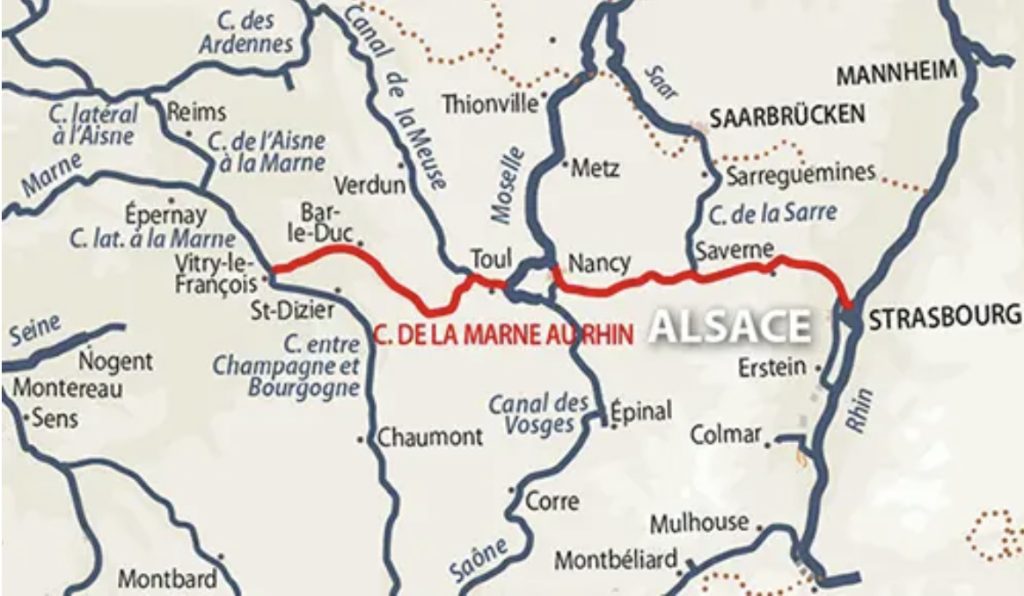

Rail Lines Between Le Havre and Strasbourg France 1855 [26]

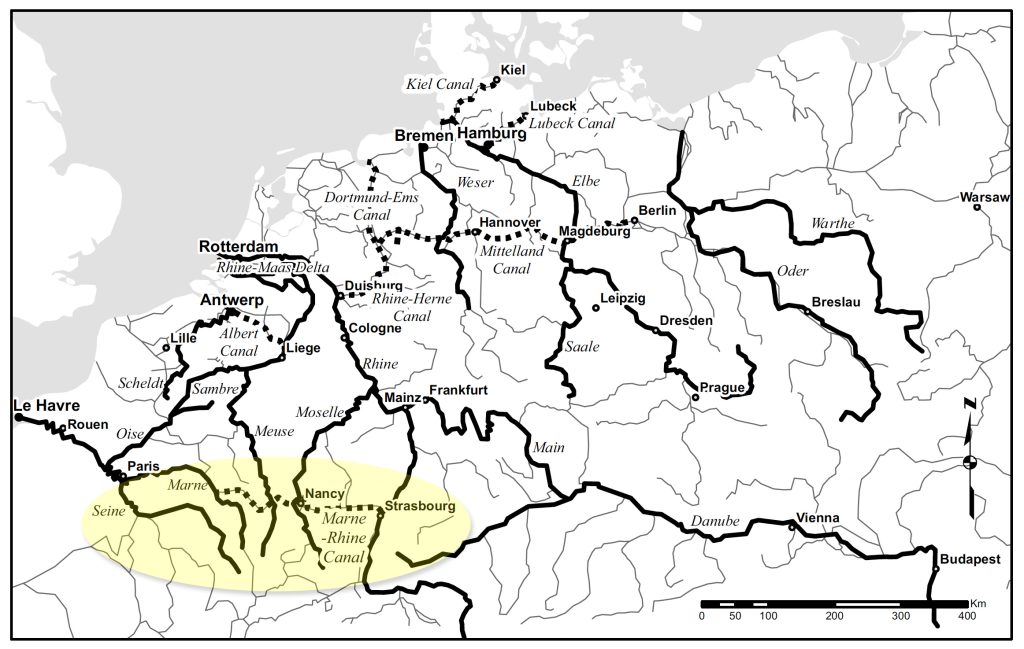

The train from Strasbourg to Paris also paralleled the newly created Marne – Rhine Canal system. The Canal de la Marne au Rhin was completed in 1855 as a vital waterway link between Paris and Alsace and Germany. Inland waterways offered opportunities to increase the economic influence of maritime ports. Combining main rivers with tributaries and canals, “Europe’s water networks resembled vast circulatory systems through which coursed the lifeblood of trade. “ [27]

“This canal was built concurrently with the railway line and by the same administration, from 1839 to 1855. Their course is parallel, with characteristic S-bends under railway bridges, especially in the descent through the Vosges. The locks were built to dimensions half way between the Becquey and Freycinet standards” [28]

Hamburg and Le Havre Ports: Range and Its Waterways [29]

If railway travel was too expensive for the family, they may have utilized the empty freight wagons that transported cotton and other good from Le Havre to Strasbourg. These wagons carried passengers will to travel the slow way to Le Havre. Another alternative was to use more rapid stage lines. [29a]

Once the family reached Paris, they may have continued their final train portion of their journey on the 142 mile long Paris–Le Havre railway. Conversely they may have continued their journey on barges or steamboats on the Seine River as deck passengers. If this was too expensive, they may have travels in wagons to Le Havre.

The stretch of railway between Paris and Le Havre was among the first railway lines in France. The section from Paris to Rouen opened on May 9, 1843, followed by the section from Rouen to Le Havre that opened on March 22, 1847.

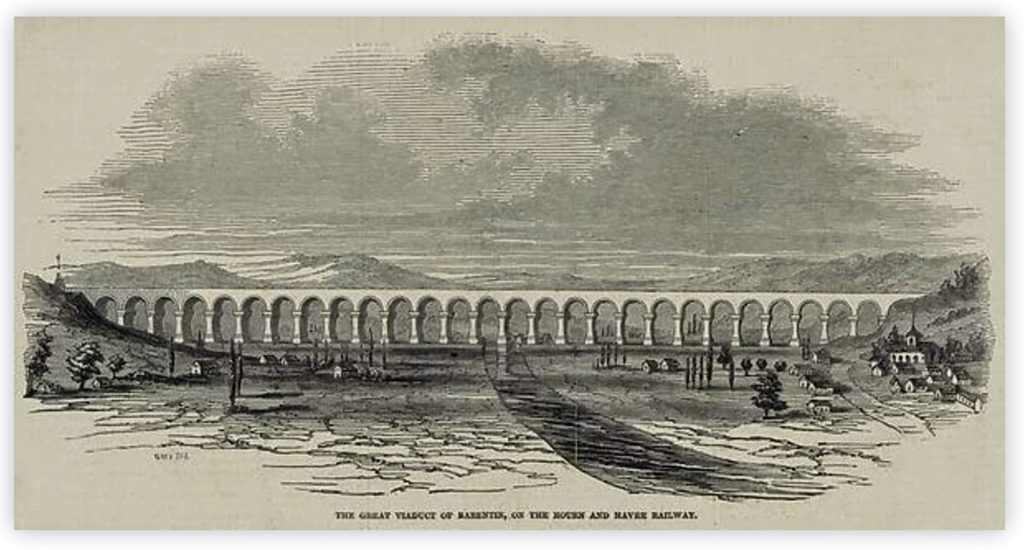

The latter section of their rail journey included the 100 feet high viaduct that crosses the Austreberthe River. The viaduct still stands. The original viaduct collapsed in January 1846. The reason for the collapse was never established. However, a possible cause was the nature of the local lime used to make the mortar which was required by the contract. The collapse occurred after a few days of heavy rain. The contractors Thomas Brassey and William MacKenzie, rebuilt the viaduct at their own expense, using lime of his own choice. [30]

The Barentin Viaduct [31]

The Fliegel family’s journey via the rapidly growing rail system in France and Germany reflects a larger transformation that was occurring in the watershed areas that serviced the northwestern ports of Western Europe.

“In the nineteenth century, steam power and railways caused a transport revolution. Not only did investments in railways push industrialization as the demand for coal, iron, and steel rocketed with their development, but the railways also connected industrial centres with markets, raw material producing areas, and seaports. Inland transport became possible on a previously unknown scale. Indeed, in the period 1840–70, the train became the dominant mode of transport, with inland navigation losing its leading position. A rapidly growing rail network was able to solve most transport problems of the developing industry, including that in the Ruhr area. This region built one of the densest rail networks in Europe, with numerous national and international connections. By 1870, most transport in the Rhine basin took place by rail.” [32]

Emigrating Through the Port of Le Havre

After traveling almost 500 miles on two major French railways, from Strasbourg to Le Havre, the Fliegel family arrived in Le Havre. Their ship was scheduled to depart on December 10, 1854. They arrived in a port city that was experiencing the economic benefits of international shipping as well as the attendant growth pains of overcrowding, poverty, urban disease, and other social conditions. In addition to the immigrants, Le Havre contained In addition to the working population that were from the area, there was a sizable group of horsains, “outsiders”, a term designating people not from Le Havre, including poor people, beggars, street vendors, emigrants unable to pay their ticket, and reputedly deserters and ex-criminals. [33] German immigrants arriving to the port city undoubtably exacerbated the strain on the capabilities of the city.

“In 1840, the “Revue du Havre” wrote that “the city is crowded with the poorest Bavarian immigrants … . The floating population began to camp out on the ramparts of the east. They take shelter under the elms; excavations in the thickness of slope ditches serve as their home … Those who have two francs a day, can find accommodation among innkeepers of St. Francis and Our Lady, who specialize in taking care of immigrants. ” [34]

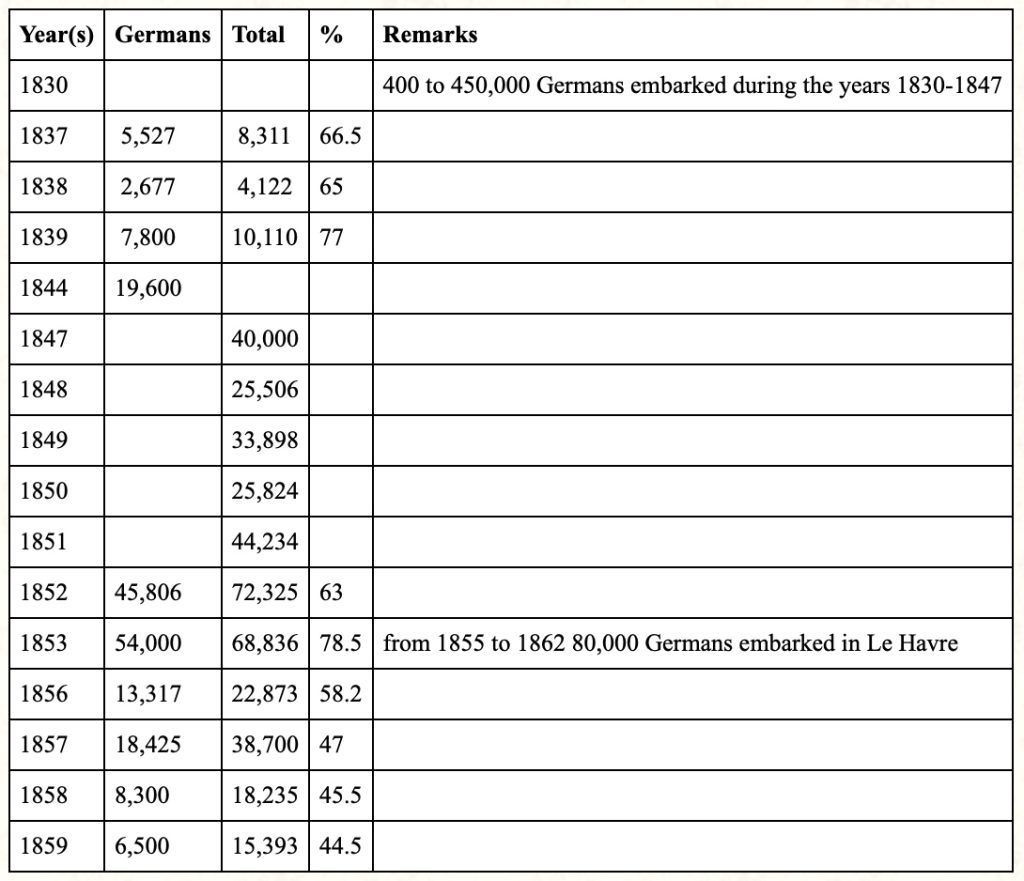

Fifteen years later after this observation in the Revue de Havre, the conditions for German immigrants to find temporary lodging for scheduled ship departures may have improved for the Fliegel Family. However, the number of immigrants embarking from Le Havre between 1839 and 1853 increased 6 fold (see table one below). Even with the presence of a “German District” in Le Havre, obtaining temporary lodging may have been challenge in 1854.

In the nineteenth century, Le Havre was the primary seaport of Paris and France’s gateway to the world across the Atlantic. Its location on the English Channel and its proximity to the French capital at the mouth of the Seine made it a major port. The gradual improvement of its port facilities since its founding in 1517 made Le Havre a leading point of transit for passengers, raw materials, and manufactured goods entering and leaving France.

“During this period, although transatlantic passenger traffic loomed large, the main activity was buying, selling, and redistributing goods… . Traders imported and bought and sold relatively expensive raw materials, mainly of tropical origin. Outgoing ships carried luxury and manufactured goods. Le Havre was the leading forward market for cotton and coffee… . Le Havre was not the first French port in terms of tonnage in this period, but it was number one in terms of the value of the goods passing through its harbor. Moreover, most cargo was not carried on French ships.” [35]

Like Paris, Le Havre experienced rapid and dramatic population growth during the mid-nineteenth century. A city of fewer than 27,000 inhabitants in 1823, it doubled in size by 1846. It was a port city of extreme wealth and poverty. [36]

“As in Paris, the sudden pressure exerted by this growth on the city’s physical and social structures caused considerable anxiety among political leaders. The concentration of so many people in the close quarters of the central city—especially working people confronting the contradictions of dire poverty in the midst of great mercantile and industrial wealth—gave a troubling immediacy to the prospect of disease and unrest; on the heels of two cholera epidemics and two revolutions in France during the 1830s and 1840s, few could ignore the threat posed by the nation’s increasingly pathological cities. A perceived penchant for drink and depravity among the “dangerous classes” only exacerbated the fears of local and national elites.” [37]

The port began to function as an emigration port at the end of the Napoleonic wars around 1815. Boarding passengers was a by-product of commercial shipments. As ship travel gained importance not only for commercial commerce but also for immigration, the docks at Le Havre were enlarged to accommodate the increased steamboat traffic from local ports. A German colony of innkeepers, shopkeepers and brokers subsequently developed to service the emigrant needs at the port. [38]

Largely due to the influx of German immigrants, Le Havre took on the appearance of a German town.

“During the active season there were always several thousand in the city awaiting the hour of departure. The delay might extend from one to six weeks or more if the winds were contrary or the congestion was great. IN the meantime they lodged in the cheapest houses, sometimes several families to a room, cooking and washing and keeping as much as possible outdoors.” [38b]

Le Havre: Child of America and Home of German Emigrants

“The combined influence of the (American) cotton and emigrant trade drew to it not only representatives of the larger commercial houses, but also a host of German innkeepers, small merchants and ship agents. The emigrants themselves sometimes went no further. … Every season left some to live upon the charity of the French, or to find a way back to their former home.” [39a]

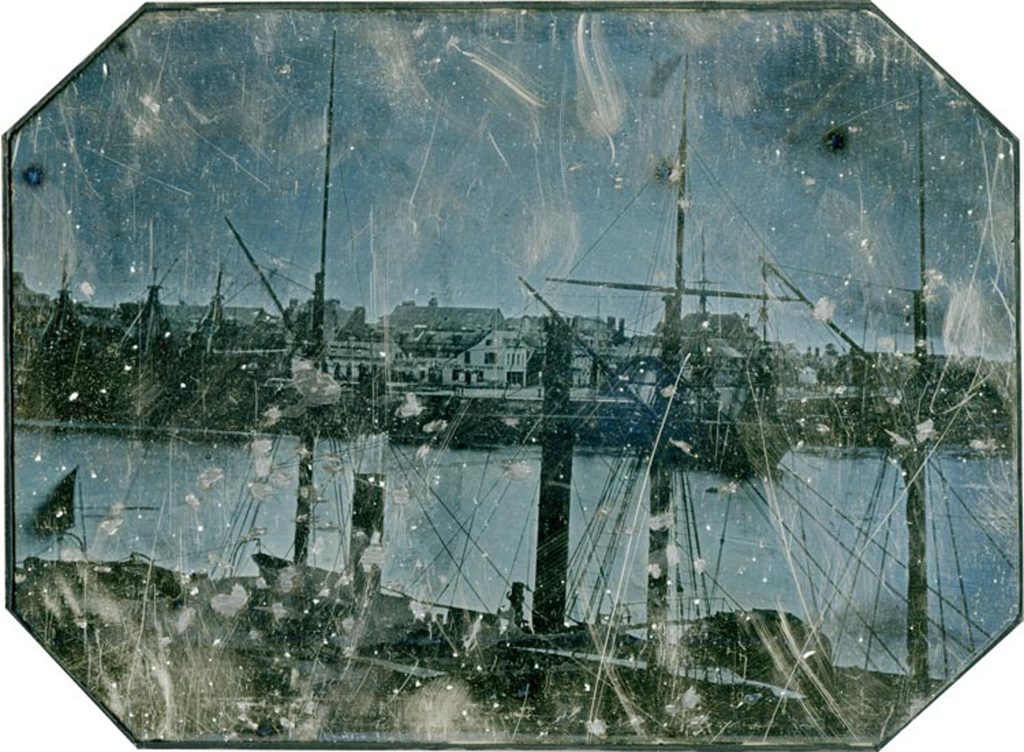

The Port of Le Havre – German District

(The) “Germain district, (in this photograph) which can be clearly seen in the center of the image. This small port district of the old Le Havre (barely one hectare in area), built on the former north-western front of the citadel, remains unknown, or even ignored, no doubt because of its short existence (1816-1856). … (the Germain district was) wedged between the barracks of the old citadel and the quay of the same name. Five small streets crossed the quarter, some of which were lined with shops and stalls. The 300 inhabitants, for the most part of modest backgrounds, exercised professions as diverse as sailor, day laborer, grocer, shoemaker or liquor shopkeeper. [39]

In 1837, the French government required Germans to present a valid ticket at the French border, severely limiting their entry and business at the port. As such, local offices began opening in Switzerland and the German states. Previously, the only document required to cross the border had been a passport. [40] However, the regulations were not strictly enforced. French authorities recognized the beneficial effects of immigrant traffic in promoting French commerce. [40a]

“Le Havre in the 1840s imported cotton from the American south and sent “passagers d’entrepot” back to the United States. In the early 1840s and 1850s it was the main port for migrants from Baden, Bavaria, and Wurttemberg as well as from Switzerland and Alsace, as it was closer to these regions than German, Belgian, or Dutch ports. Although the overseas voyage to the United States was more expensive from Le Havre than from Antwerp, Rotterdam, Liverpool, or London, the Basel-Strasbourg-Paris-Le Havre Railway, completed in 1852, offered a more direct route. Le Havre was the major port for the day-laborers, farmers, merchants, and also iron and textile workers from Mulhouse and Guebwiller. In the 1840s and early 1850s more Germans left for the United States from Le Havre, Rotterdam, Antwerp, London, and Liverpool than from Bremen or Hamburg.” [41]

A review of statistics on the number of immigrants leaving from the Le Havre port between 1837 and 1859 underscore the predominance of Germans using this port for their journey to the United States. As indicated in the table below, Europeans embarking for the United States via Le Havre were predominately from German states between 1837 and 1856. The Fliegel family were part of the tail end of this wave.

Table One: German Immigrants Leaving from Le Havre for United States [42]

| Year | No. of German Immigrants | Percent of Total Immigrants | Total No. of Immigrants |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1837 | 5,527 | 66.5 | 8,311 |

| 1838 | 2,677 | 65.0 | 4,122 |

| 1839 | 7,800 | 77.0 | 10,110 |

| 1852 | 45,806 | 63.0 | 72,325 |

| 1853 | 54,000 | 78.5 | 68,836 |

| 1856 | 13,317 | 58.2 | 22,873 |

| 1857 | 18,425 | 47.0 | 38,700 |

| 1858 | 8,300 | 44.5 | 18,235 |

| 1859 | 6,500 | 44.5 | 15,393 |

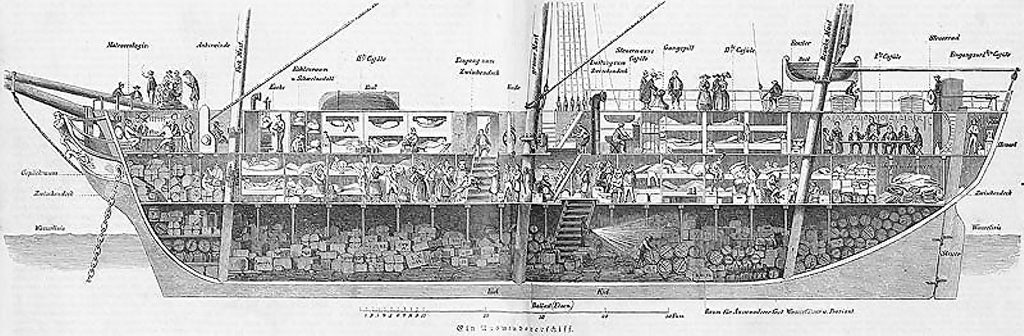

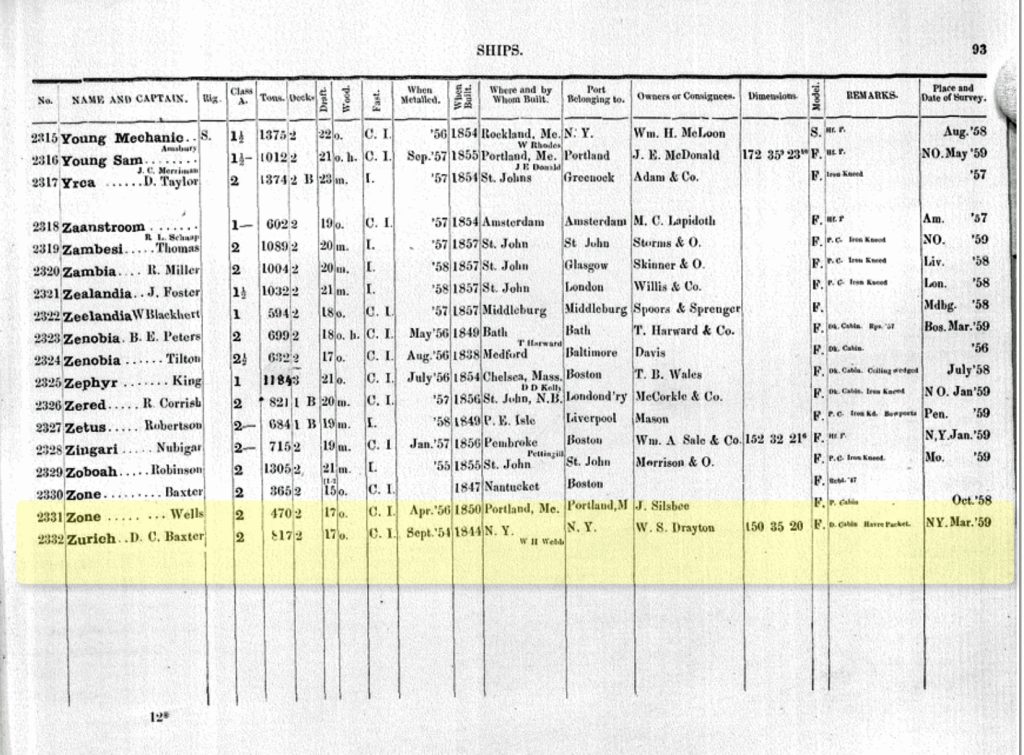

Sailing on the Ship Zurich of the Harvre Union Line

From the port of Le Havre, France, the family embarked on the packet ship, Zurich, run by the Havre-Union Line to New York City. The term ‘packet ship‘ was used to describe a vessel that featured regularly scheduled service on a specific point-to-point line. Usually, the individual ship operated exclusively for the line. Four characteristics of a packet service were:

- a regular line between ports;

- ships operating exclusively in the service;

- common ownership of the operating ships and associated facilities by individuals, a partnership, or a corporation; and

- regular sailing on a specified day of a certain month. [43]

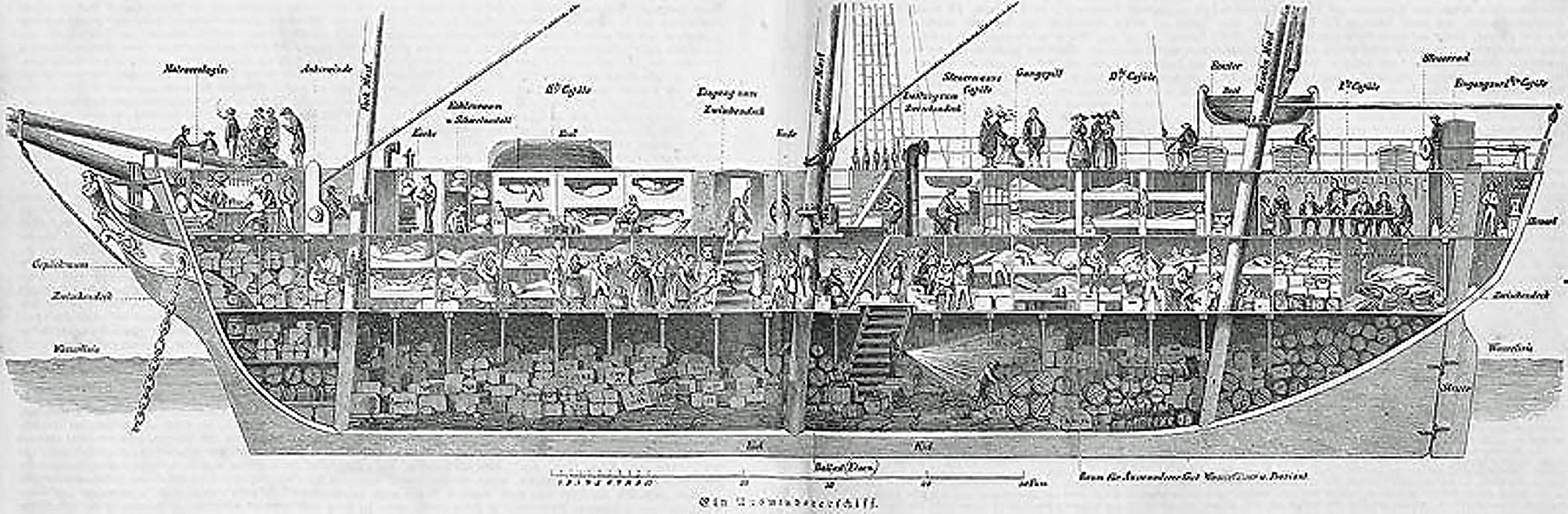

“Packet Ships were sturdy vessels designed to sail the rough north Atlantic at the cost of speed. They measured about 200 feet long with three masts and a blunt, broad and flat bow. They could travel about 200 miles per day if the conditions were right. Their trans-Atlantic voyages averaged 23 days to go east, and 40 days to go west.” [44]

The first American packet line, the Black Ball Line began operating in 1818. The shipping line employed four ships and offered a monthly service between New York and Liverpool, England. [45]

“The Black Ball Line established the modern era of liners. The packet ships were contracted by governments to carry mail and also carried passengers and timely items such as newspapers. Up to this point there were no regular passages advertised by sailing ships. They arrived at port when they could, dependent on the wind, and left when they were loaded, frequently visiting other ports to complete their cargo. The Black Ball Line undertook to leave New York on a fixed day of the month irrespective of cargo or passengers.” [46]

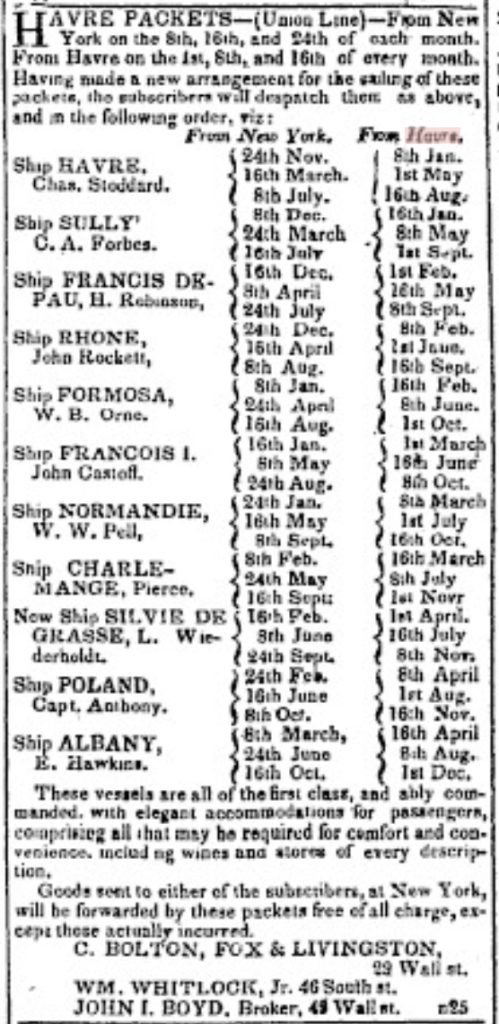

Source: The Evening Post, Page One, 17 March 1835, New York City

The success of the Black Ball packet line encouraged the organization of packet service between New York and Le Havre, France. Four years after the inception of the Back Ball Line, three packet lines were organized between New York and Le Havre, France in 1822 and 1823. The three Havre Lines eventually evolved into one line, the Havre Union Line. [47]

In 1835, the New York Evening Post contained an announcement that “Havre Packets” on the “Union Line” departed “from New York on the 8th, 16th, and 24th of every month,” while returning ships departed “from Havre on the 1st, 8th, and 16th of every month.”

Departure dates and captains were given for each of eleven ships. The list included eight vessels from the Havre Old Line and three vessels from the Havre Whitlock Line.

This schedule of departures and arrivals between the two ports generally continued into the 1840s and 1850’s with some exceptions.

Notwithstanding the advertised schedule of departures, delays of ships embarking to their destinations may have extended from one to six weeks if the winds were contrary or the congestion was great. [47a]

“In the meantime they lodged in the cheapest houses, sometimes several families to a room, cooking and washing and keeping as much as possible outdoors.” [47b]

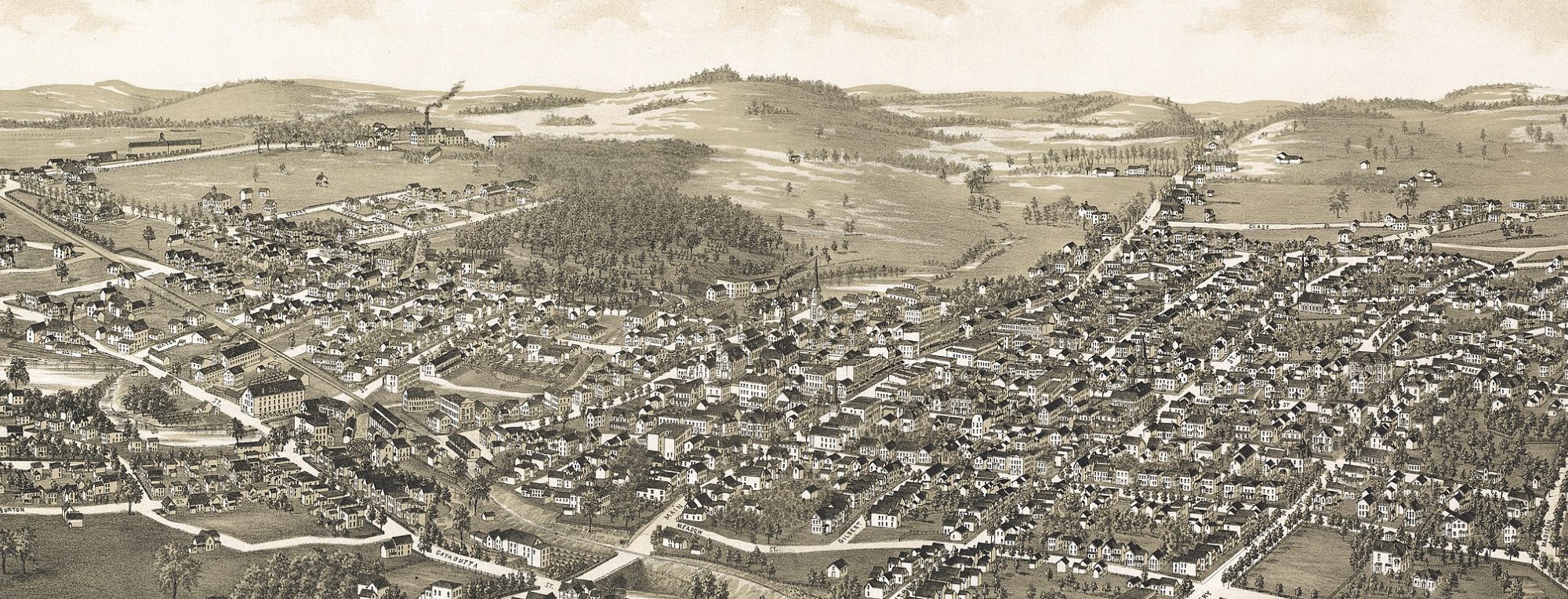

The costs and traveling conditions for the Fliegel family’s voyage to the United States are not known. However, there are remnants of historical documents of steerage passenger contracts for voyages between Le Havre and New York during this time period that probably reflect the standard conditions that immigrants encountered.

Front of Steerage Passage Contract from 1854, Le Havre to New York

➤ Read More on standardized terms and conditions that were probably utilized by various packet ship and steamship companies for most of the steerage travel from Le Havre, France. See: Contract & Regulations Governing Steerage Passage in 1854

The example on the left is a contract for steerage passage on a ship from Le Havre to New York City in 1854. [48]

“The cost of the voyage fluctuated greatly. Until the middle of the century the German ships were alone in furnishing steerage passengers with the necessities of life; on all other ships they were required to provide themselves with everything except fire and water, so that the price paid to the master of the vessel was not the largest part of the emigrant’s expenses.” [49]

“The charge for transportation from the continental ports seems to have been subject to more extreme fluctuations than from the ports of Great Britain. Thus in the summer of 1835 passengers from Bremen paid only sixteen dollars, and were provided with good food on the voyage. Ten years later the charge was twenty dollars from Bremen, twenty-three from Hamburg, including food from both ports; and thirteen or fourteen without food from Antwerp, Rotterdam, and Havre. In 1856 it had risen to thirty dollars from the German cities.” [50]

The Fliegel family may have experienced many of the requirements on their journey on the Ship Zurich that are delineated in the example of a steerage contract mentioned above.

If they missed the ship, they would have lost their right of passage on the ship. Passengers were required to be on board two hours before departure time. Passengers were also required to have their passports stamped by the police.

Basically, the family was required to provide their bedding, cooking utensils and supply their own food. The Captain provided water, wood, access to a kitchen, and unfurnished cabin space and medicines in case of illness. The fresh water was only for drinking and for preparing food; and not be used for washing. boarding the ship, each member of the family may have been required to load the following food and were advised to bring fresh bread for five or six days.

- 40 pounds of biscuits.

- 1 hectoliter (= 2 bushels or 140 lb.) of potatoes or 30 pounds of dry vegetables.

- 5 pounds of Rice.

- 5 pounds of Flour.

- 4 pounds of butter.

- 14 pounds of smoked ham.

- 2 pounds of salt.

- 2 liters of Vinegar.

If they did not have these quantities on board twelve hours before the fixed departure time, they were subject to removal from the list of passengers and would not have been be able to travel with the departing ship.

Everyone was expected to keep their steerage space clean as well as the area in the front of their quarters every morning, otherwise they would not be allowed to cook. Their physical belongings, biscuits, potatoes and wine were not kept in living quarters but stored in the hold and accessible at specific times of the day. If they had any trunks, crates, or bags, they were to be clearly marked on the top with the number of the designated cabin steerage space. They were expected to load and unload their own baggage and food. If they had large trunks and crates, they were lowered in the hold. At sea, the hold would be opened at necessary times for passengers to access their food. The stern of the ship was reserved for the captain.

They were required to abide by a number of safety and security measures. No weapons were allowed on the ship nor could anyone smoke on the ship or to burn candles while the vessel is at dock. At sea, smoking was permitted, but only on the deck and with covered pipes. Captain’s permission was required to light a lantern in the steerage, and it was strictly forbidden to carry chemical matches on board. It was forbidden to give wine or spirits to drink to the crew. Signs of drunkenness would result in having their wine seized until the arrival in the United States.

When the ship was out of the dock, all passengers were required to get on deck at a specified time and meet by family together with all members for roll call. All would then be dismissed to go back to the steerage at the end of the call.

The American Ship Zurich was built in New York by William Henry Webb, an American shipbuilder in Manhattan in 1844. [51] It was a class A2 ship of 817 tons with 2 decks. The ship was made of white oak and the hull was medalled in September 1854. During its lifetime (1844 – 1863) it sailed from the New York port and principally sailed to Havre, France. The ship’s average voyages were 35 days from Le Havre to New York City. [52] It was one of twenty-five packet ships that were part of what was called the Havre Old Line. [53]

“The average length of a westbound journey was 34 days, but it varied very much from one journey to another. Even though there were slower and faster vessels, one and the same ship could make a westbound trip in 41 days and the following one in 22. It was not unusual that the vessels arrived in another order than they had left from the port of departure, even if there was one or two weeks difference between the sailing dates. Though it was true that winter sailings were harder and often longer than those of the spring or autumn (summer sailings often suffered from fog on the North American coast), even the winters were variable.” [54]

Model of American Packet Ship Zurich [55]

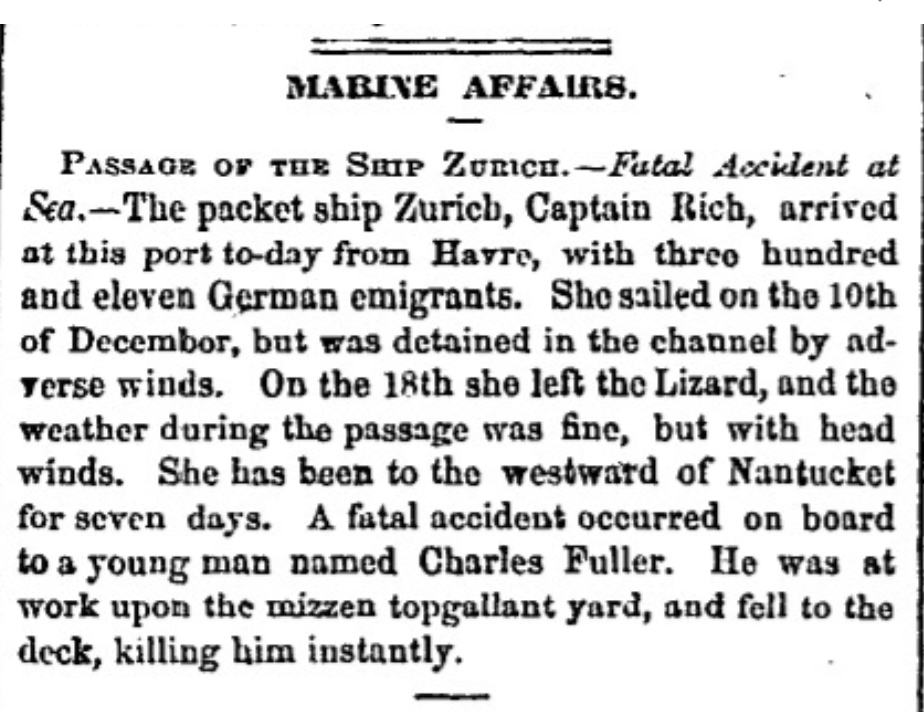

The arrival and brief description of the voyage of the packet ship Zurich from Le Havre to New York was mentioned in the New York Evening Post on January 6, 1855. It provides an interesting set of facts and events. Evidently, the voyage had a few unique events. Weather delayed the voyage at the front end of the trip and the tail end of the trip. The average length of a westbound journey of a packet ship was 34 days,. Adverse winds extended the length of the voyage to 47 days. In addition, one of the ship staff had a fatal accident.

The newspaper article indicates that the voyage initially experienced adverse winds in the English Channel. While the ship departed on December 10th, the ship was detained at the Lizard and was unable to leave the channel until December 18th. The ship also encountered stiff headwinds at the end of their journey near Nantucket which added seven days to the length of the trip.

“The Lizard” refers to Lizard Point. Lizard Point is in Cornwall, England and is at the southern tip of the Lizard Peninsula. For many ships coming from Northwestern European ports, such as La Havre, the Lizard was the starting point of their ocean passage and a well known shipping hazard. [56]

Lizard Point and Le Havre on the English Channel

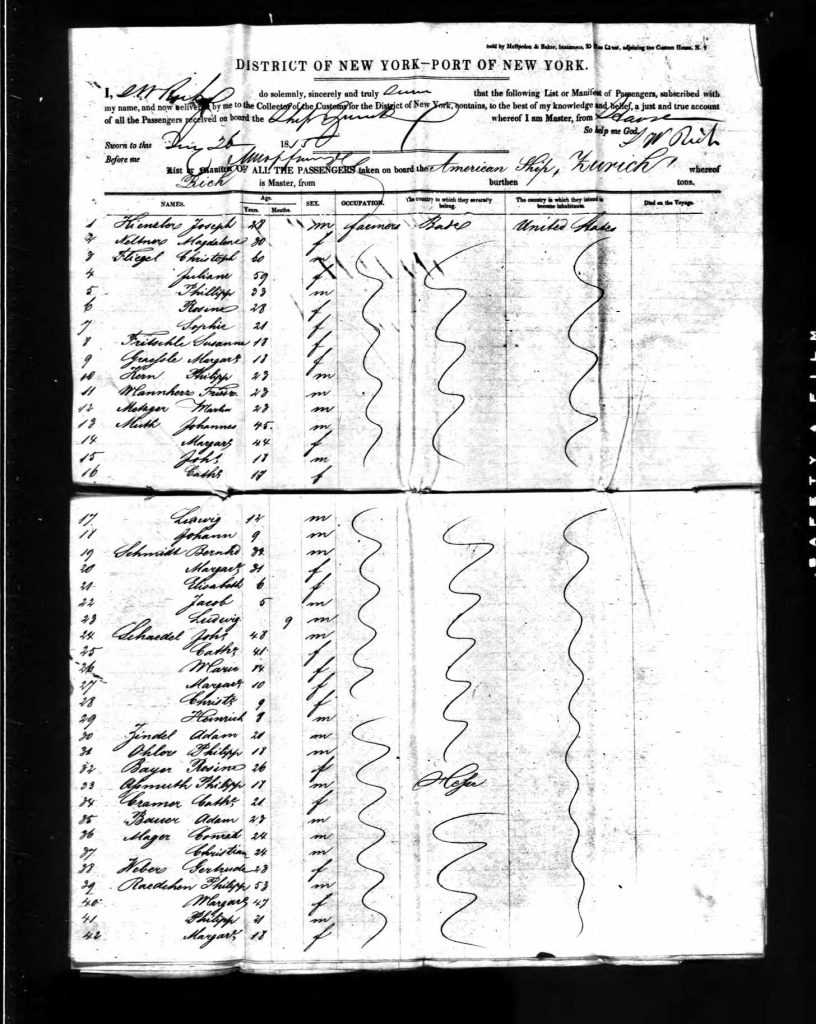

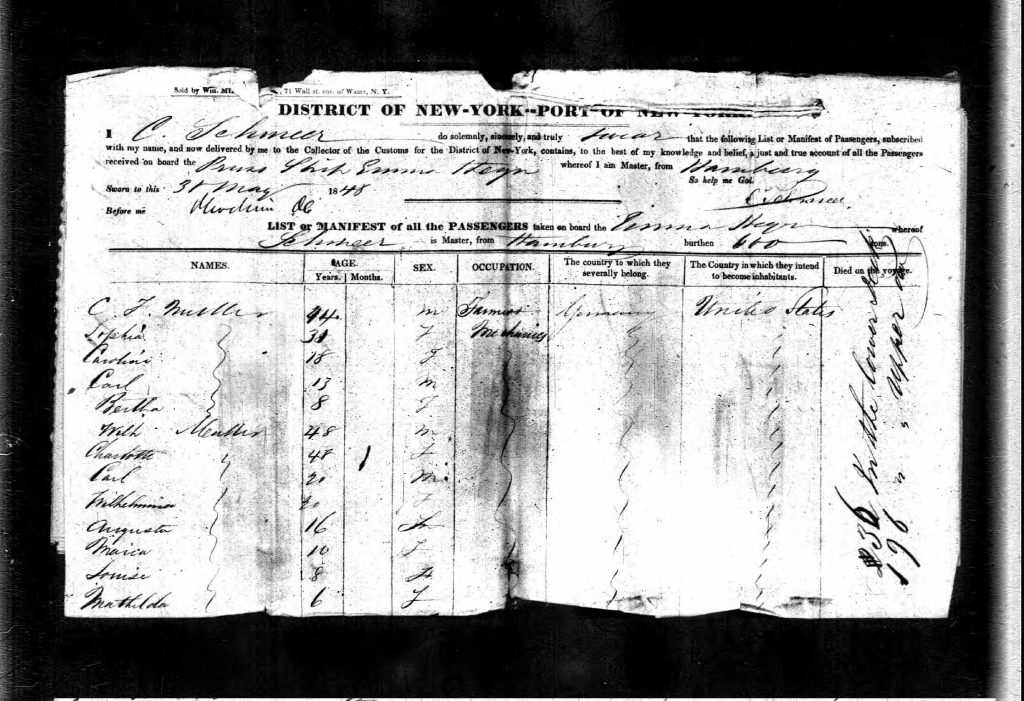

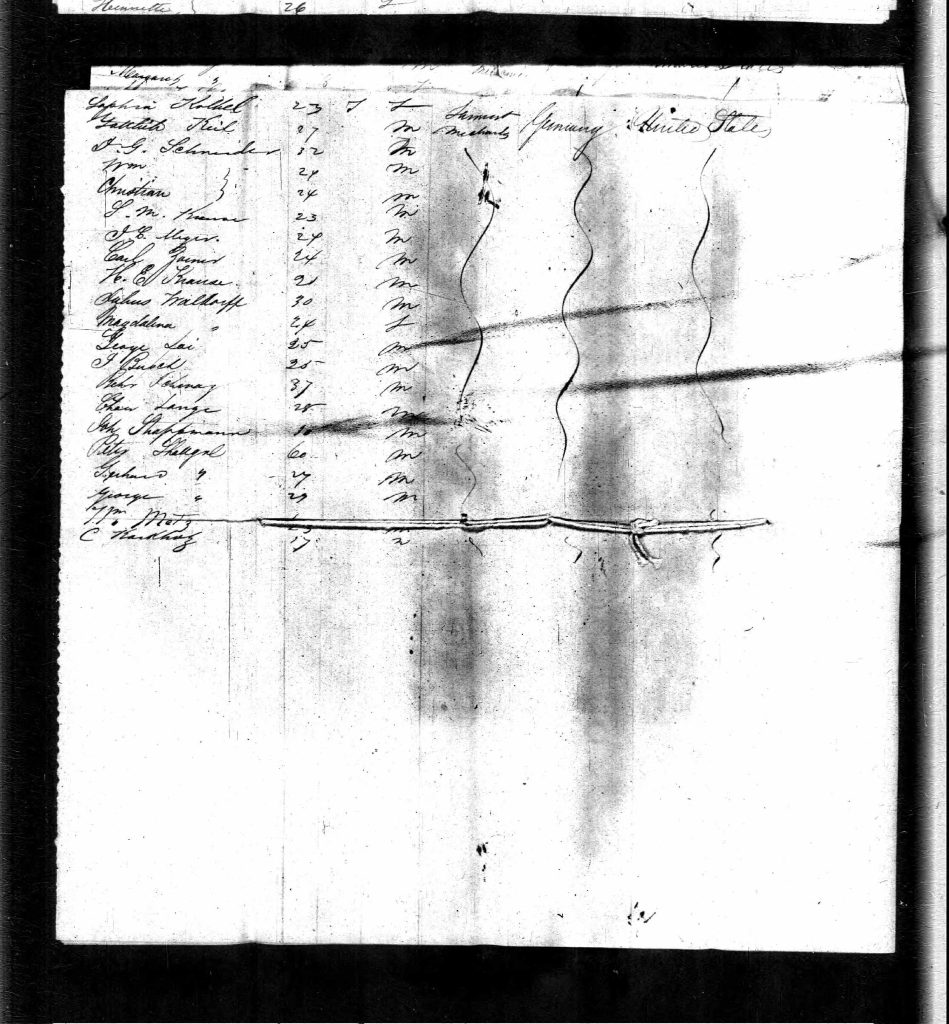

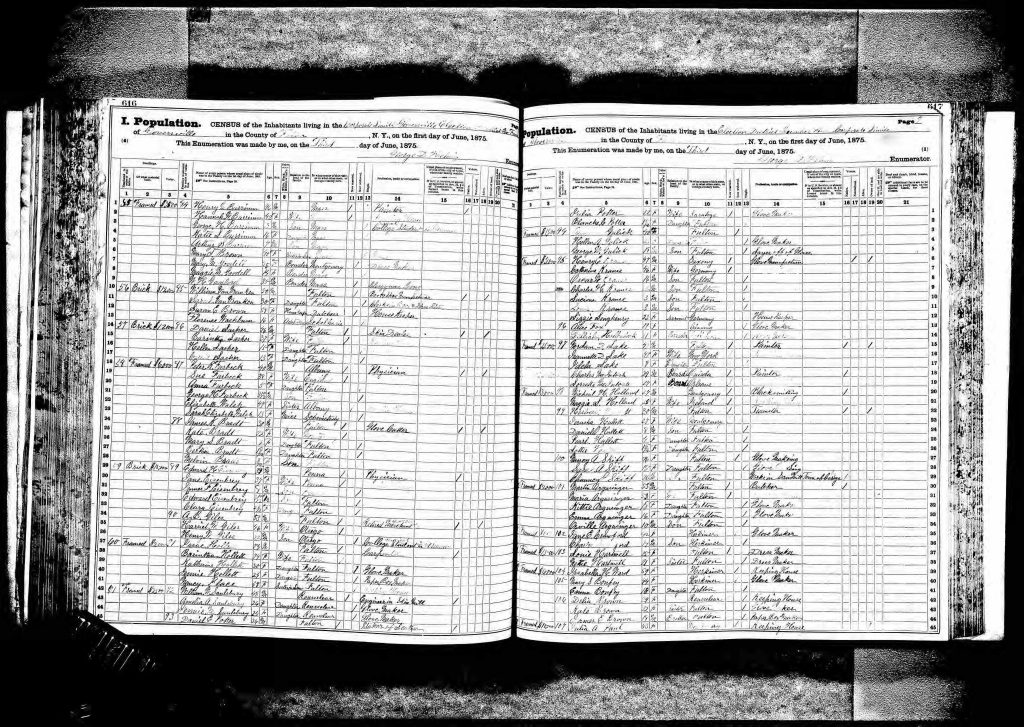

The manifest list for the ship, Zurich, listed the following members of the Fliegel family (lines 3 – 7): Christoph Fliegel (age 60), Juliani (59), Phillipp (33), Rosina (28) and Sophie (21) from Baden Germany. The reported birth years do not jibe with other sources for their respective birth years. However, I imagine each family member was required to provide documentation from the Grand Duchy of Baden to board the ship and the reported ages would correspond to their documents.

The occupation for all of the family members was listed as ‘farmer‘. [57] While the newspaper story indicates 311 German emigrants, the manifest lists 303 individuals who sailed on the ship ‘Zurich‘ and arrived in New York City on January 26, 1855. [58]

Ship Zurich Manifest List: Fliegel Family (Lines 3 – 7)

View of Shipping Piers on the East River from Fulton Market with Brooklyn in the Distance [59]

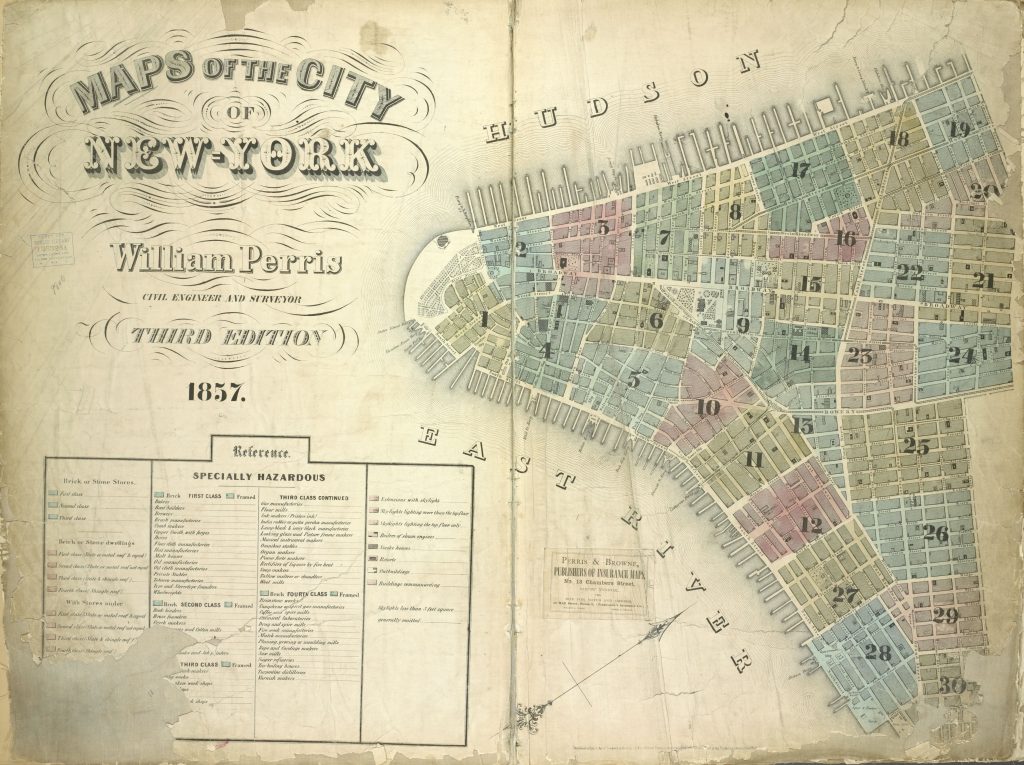

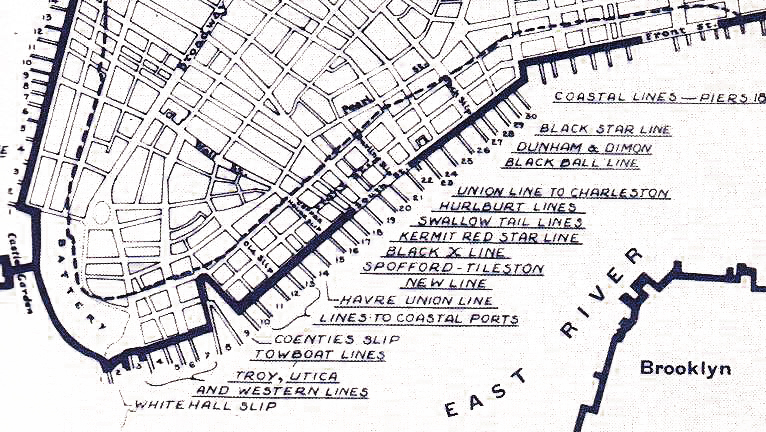

Havre Union Shipping Line – Pier 14 Port of New York, New York City 1851

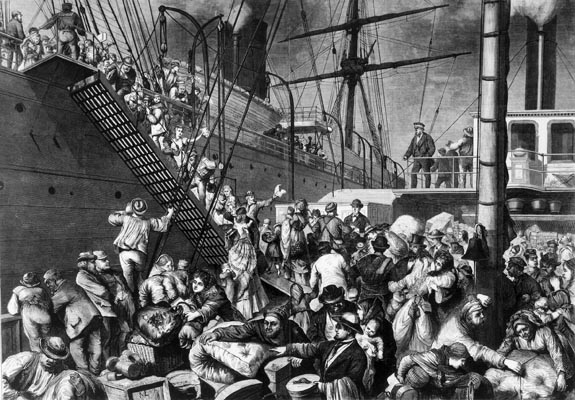

Prior to August 1855, New York did not have an immigrant processing center. Passengers simply got off the ship onto whatever wharf they had landed on in Manhattan and went their way. There was no central processing center. They were recorded on ship passenger lists beginning in 1820. [60] Havre Union Lines packet ships arrived at dock 14 in Manhattan on the East River, as indicated in the map below.

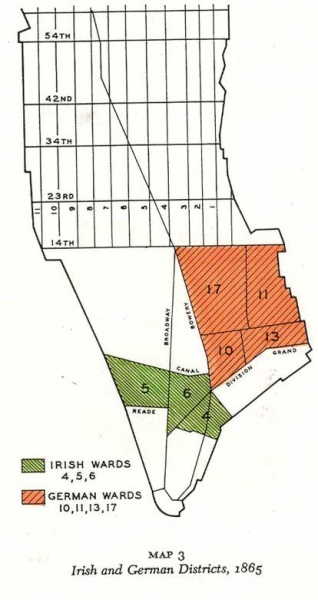

Little Germany and Onward to Johnstown, New York

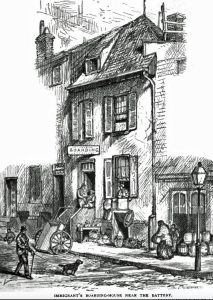

“The trials of the immigrant were by no means ended when he reached shore, for wherever he landed he was liable to fall a prey to the spoiler. Without the aid of friends who knew the snares that were set for him and understood the arts and wiles of the “bunco” men that lay in wait, he was fortunate if the first few weeks of residence in the land of hope and freedom were passed without the loss of a great part of his possessions including his health and freedom.” [61]

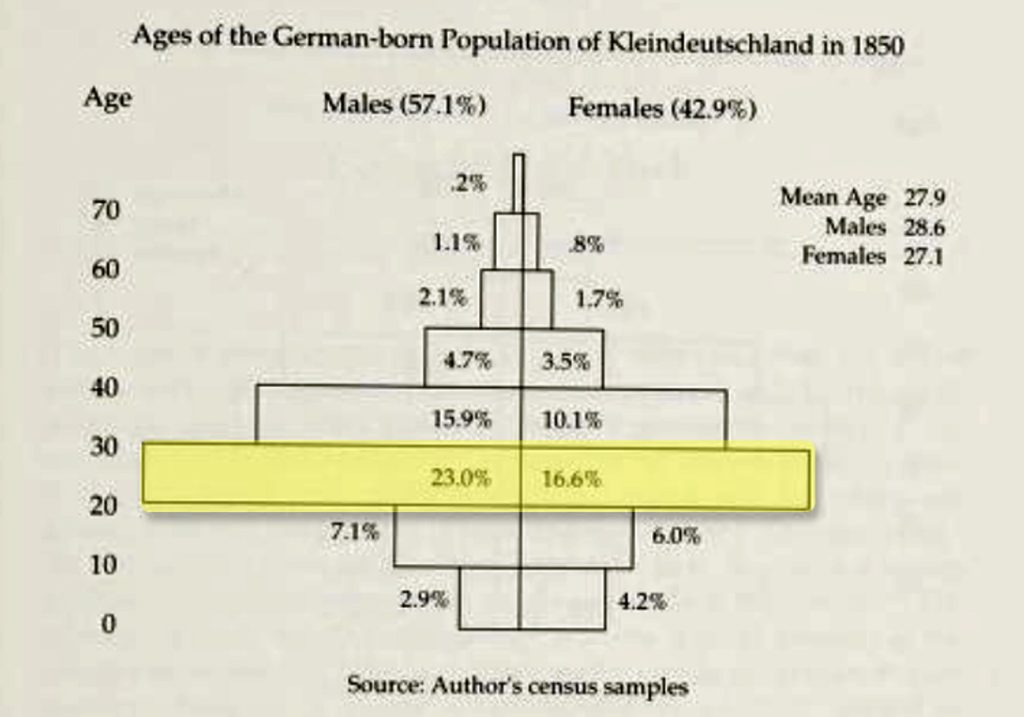

It is not known if the Fliegel family had perhaps a network of German immigrants they relied upon in Little Germany, the Kleindeutschland, to assist them when they landed. They may have obtained lodging in little Germany for a night or two and then proceeded to Johnstown, New York via train and road travel. Many of the German immigrants who came to New York City during this time period settled down to live their lives on the Lower East Side of New York City. Other German immigrants, notably the Fliegel family, probably used this geographical ethnic enclave as a launching or staging area to continue to a planned destination in the United States.

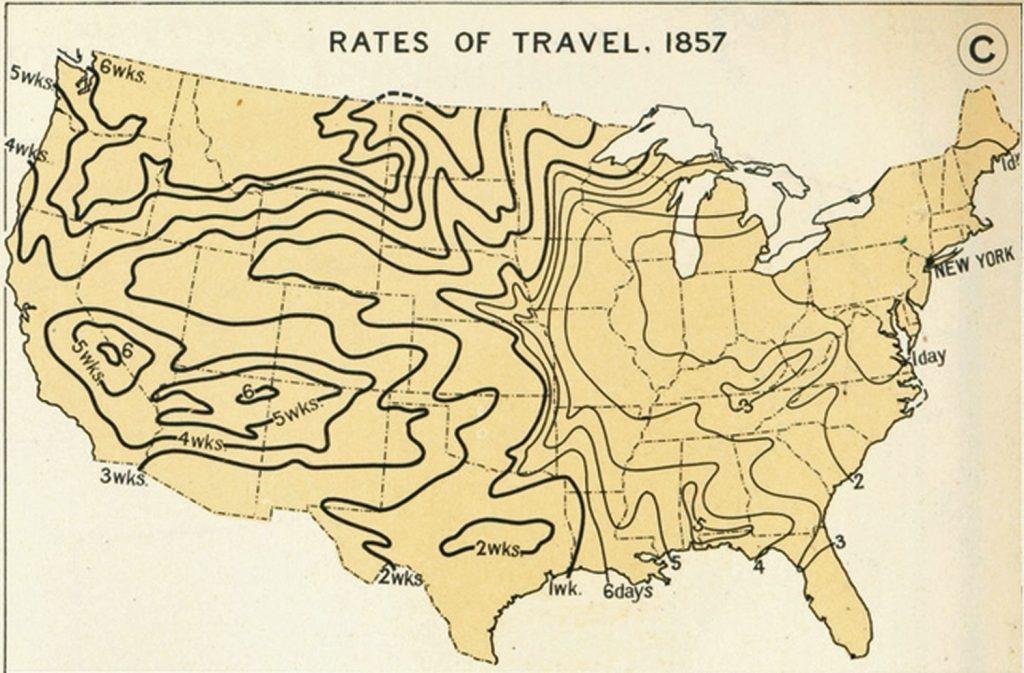

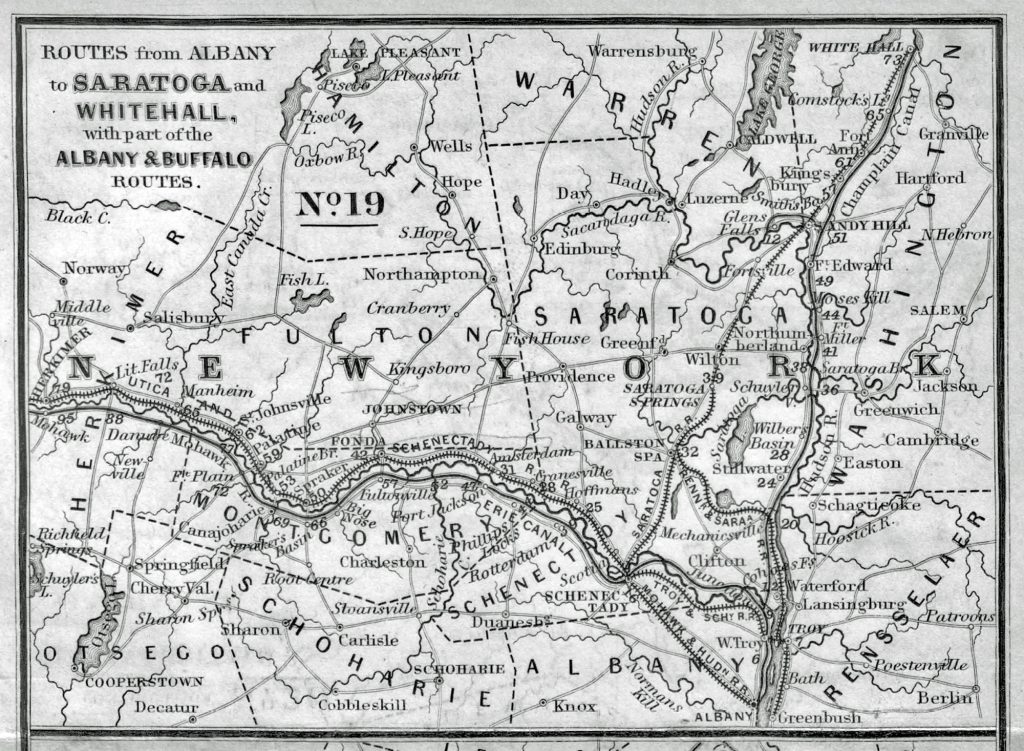

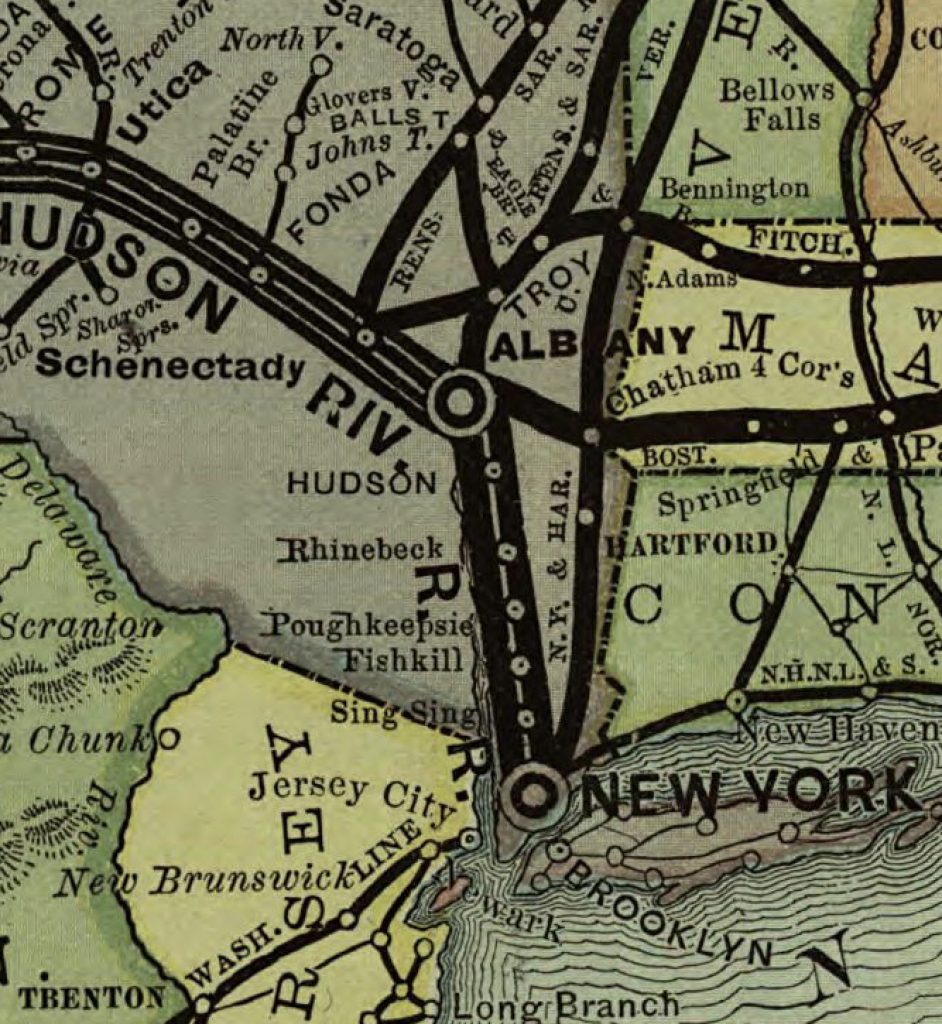

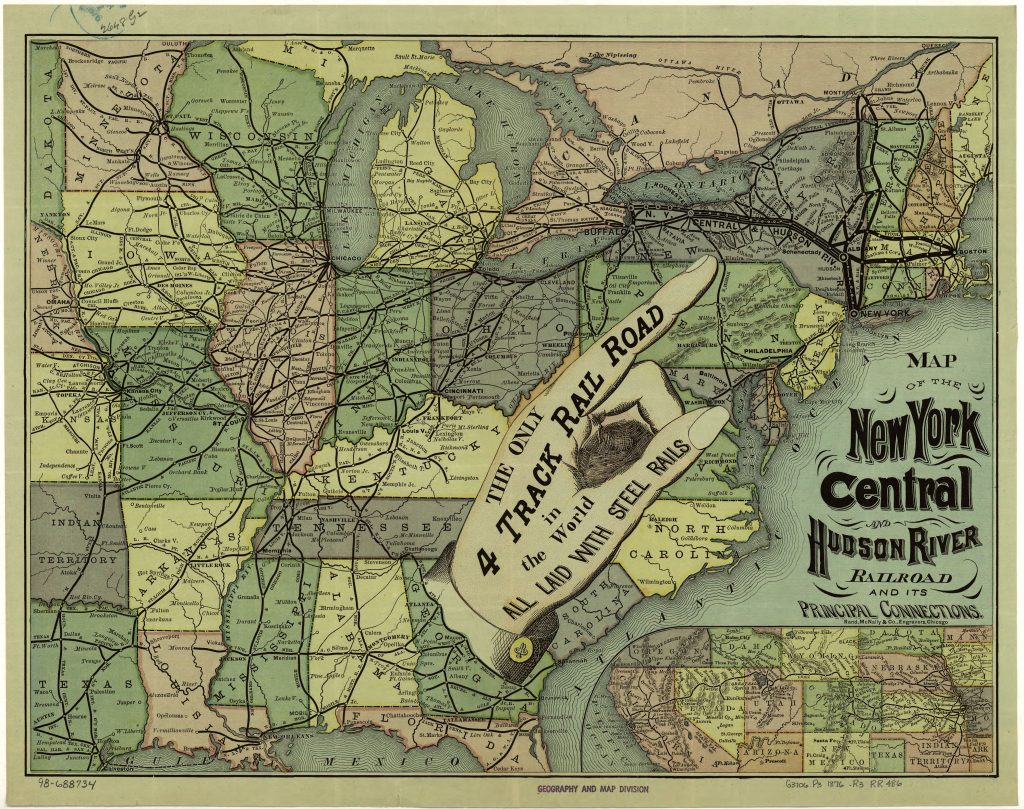

At the time of their arrival to New York City, it was possible for the Fliegel family to utilize rail service from New York City to Albany New York or continue on to Fonda, New York. Albany is about 45 miles from Johnstown. The other option was continuing rail service to Fonda, New York and then take a stagecoach to Johnstown The distance between Fonda and Johnstown is only 4.6 miles.

By the mid 1850’s the railway system in New York State enabled travel to many parts of the state within one day.

Travel Times in days & Weeks from New York City in 1857 [63]

The New York Central Railroad was established in 1853, consolidating several existing railroad companies. [63] The area around Albany, Troy and Schenectady had a long history of developing segments of railway that were absorbed in the 1853 merger. The Erie Canal, opened in 1825 between Albany and Buffalo and followed the Hudson and Mohawk rivers between Albany and Schenectady. The 40-mile Albany–Schenectady water route included several locks and was slow. Stagecoaches traveled the 17-mile direct route between the cities. In 1826 the Mohawk & Hudson Rail Road was incorporated to replace the canal stages between Albany and Schenectady. The Mohawk & Hudson Railway opened in 1831 [64]

“One by one, railroads were incorporated, built, and opened westward from the end of the Mohawk & Hudson: Utica & Schenectady, Syracuse & Utica, Auburn & Syracuse, Auburn & Rochester, Tonawanda (Rochester to Attica via Batavia), and Attica & Buffalo. By 1841 it was possible to travel between Albany and Buffalo by train in just 25 hours, lightning speed compared with the canal packets. Ten years later the trip took a little over 12 hours. In 1851 the state passed an act freeing the railroads from the need to pay tolls to the Erie Canal, with which they competed. That same year the Hudson River Railroad opened from New York to East Albany.” [65]

As reflected in the map of railways in the Albany and Schenectady area below, the rail spur from Fonda, New York to Johnstown, New York was not yet built. The Fliegel family probably met their daughter / sister at the rail station or took a stage coach for about 5 or 6 miles to Johnstown, ending what was a long journey.

“In the mid-19th century virtually every town and city of any size was hoping to be served by the rapidly growing, and sprawling, railroad industry.

“One of these communities was Johnstown, which thought for sure it was soon to gain rail access when Fonda to the south along the Mohawk River was reached by the Mohawk & Hudson Railroad on August 1, 1836.

“Unfortunately, residents had to wait for more than 30 years until trains finally reached their community. … Beginning in October of 1872 the Gloversville & Northville Railroad began construction of a 17-mile extension to link its namesake towns, which was completed by the summer of 1876.” [66]

Albany & Schenectady Railroad System Map, Circa 1847 [67]

The map below was made in in 1874 and accurately depicts the existence of a railway that branches off from Fonda, New York to Johnstown and then to Gloversville. [68]

Railway from New York City to Fonda, New York After the Fliegel Family Arrived

The Fliegel Family in Johnstown, New York

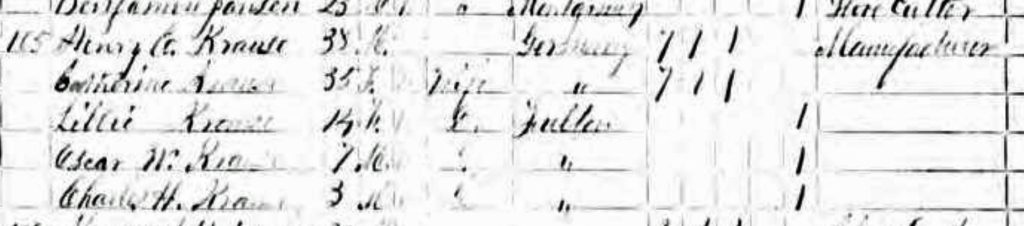

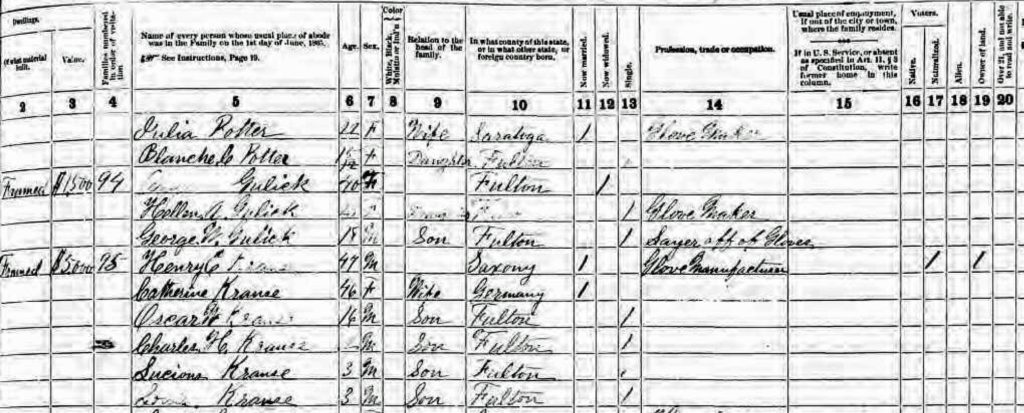

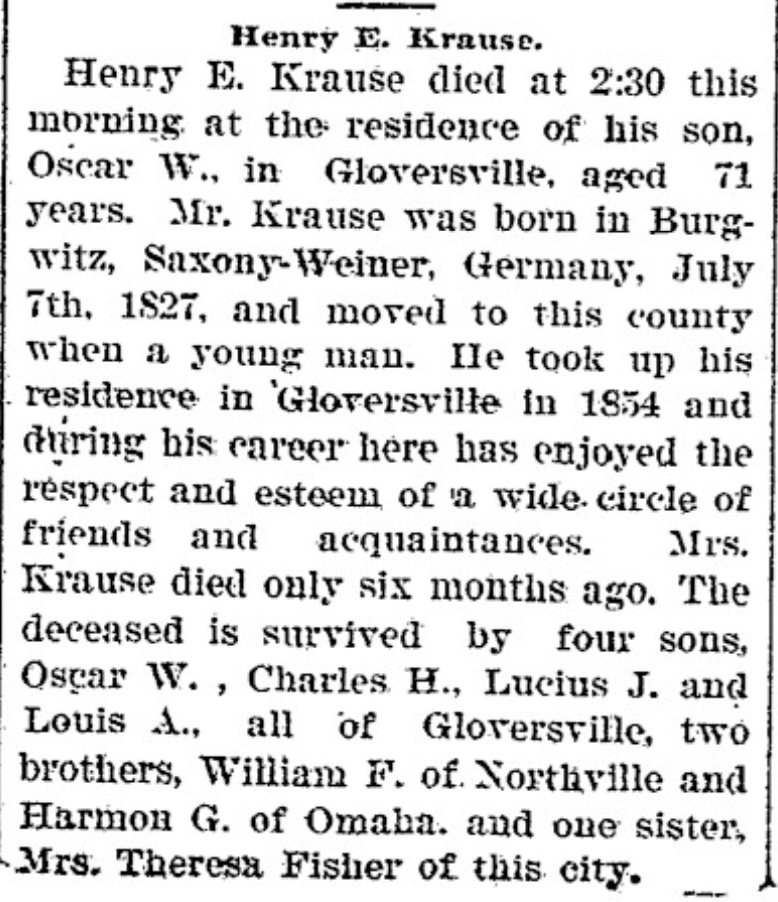

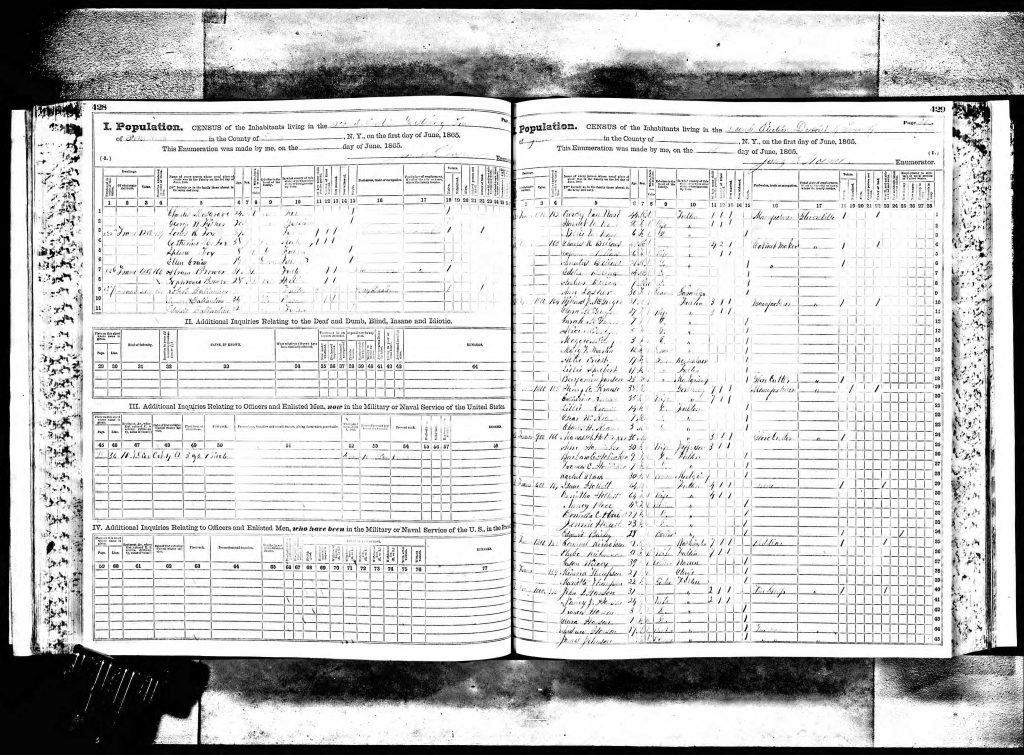

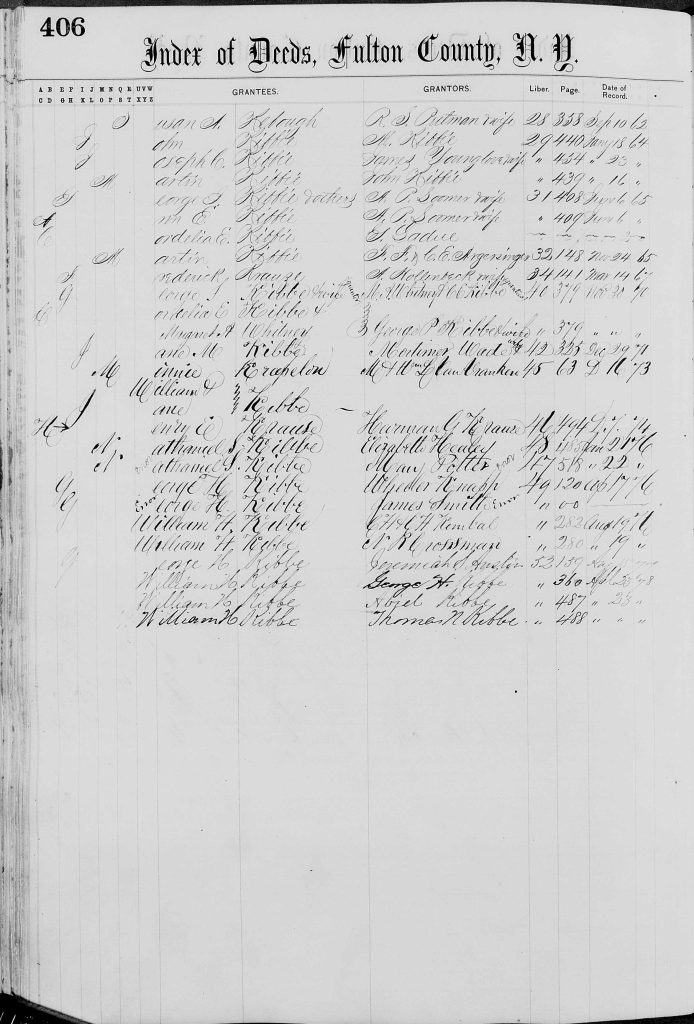

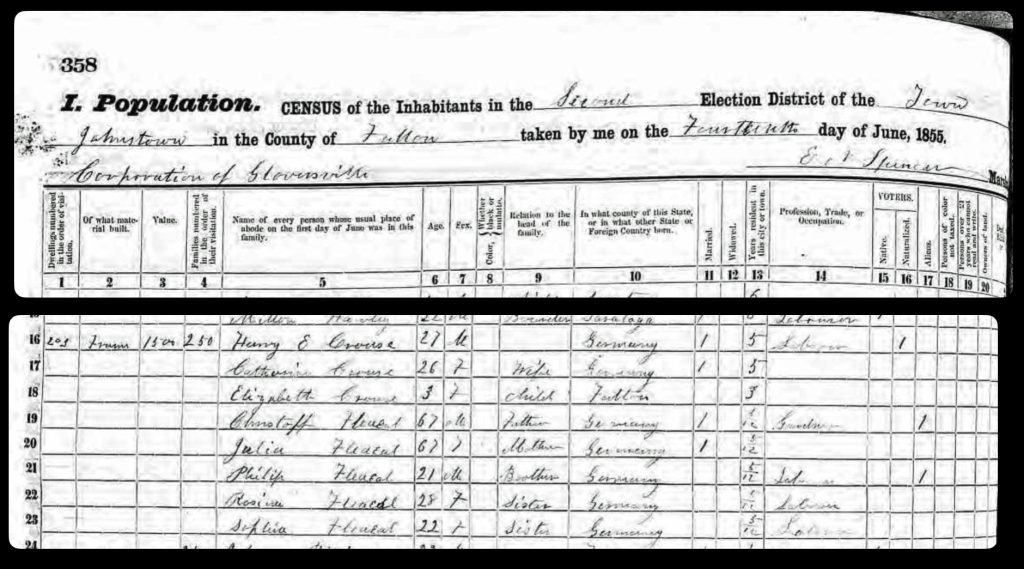

Based on information from the New York state census of 1855, the entire Fliegel family was reunited. The parents as well as the three adult children were living with Catherine (Fliegel) Krause and her husband Henry Krause and their three year old daughter Elizabeth. It is interesting to note that column 13 of the census asks how many years the individual lived in the city or town. For the members of the Fliegel family that immigrated and arrived in January of 1885, it indicates that they were living in Johnstown for five months. The census was taken on June 14th, 1855.

1855 New York Census – Krause and Fliegel Household

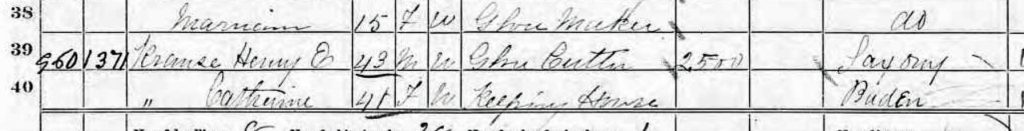

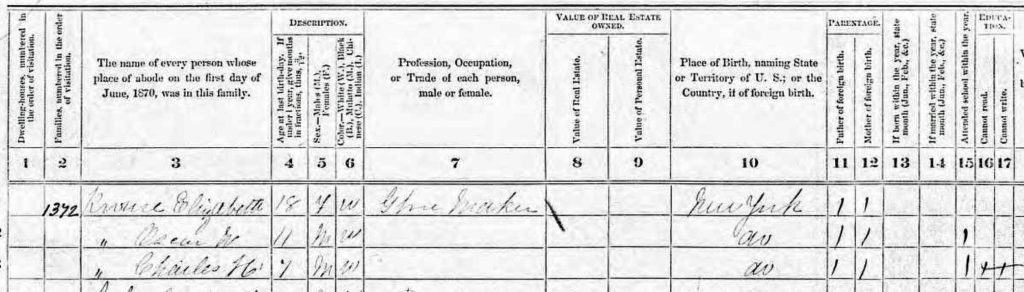

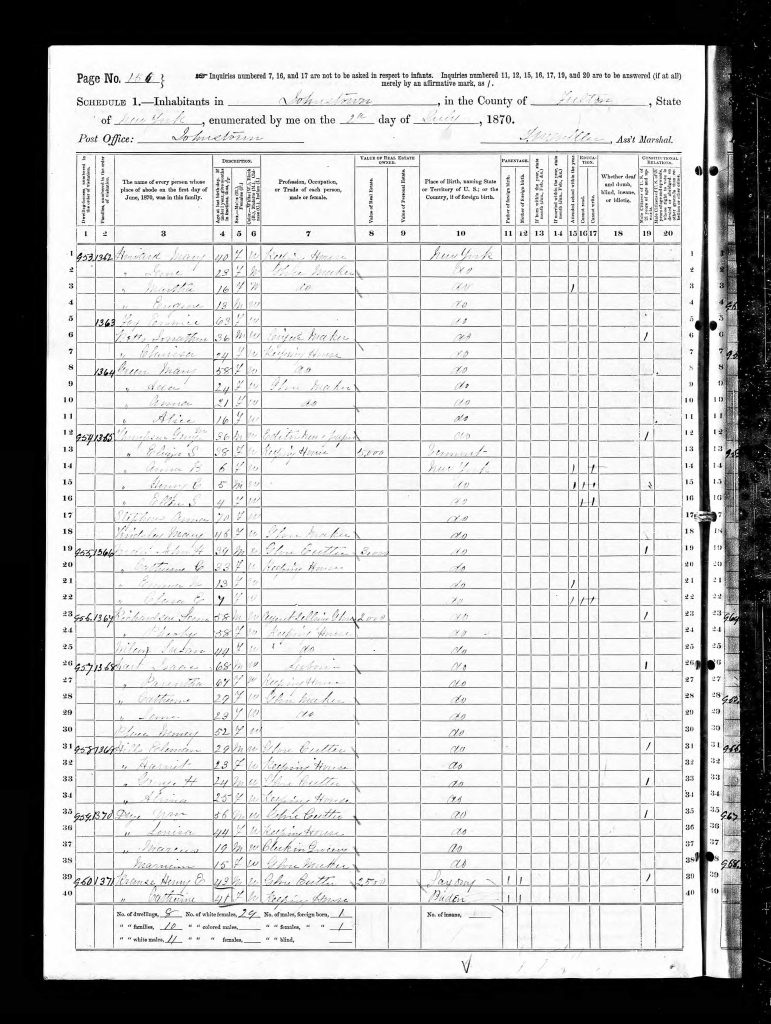

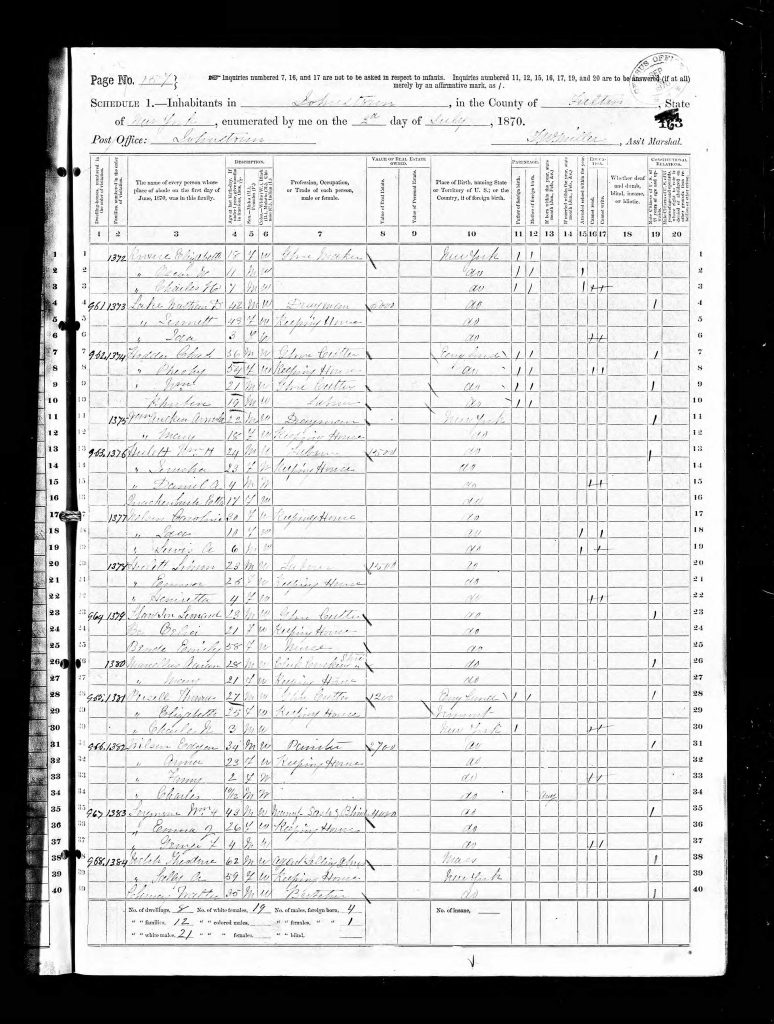

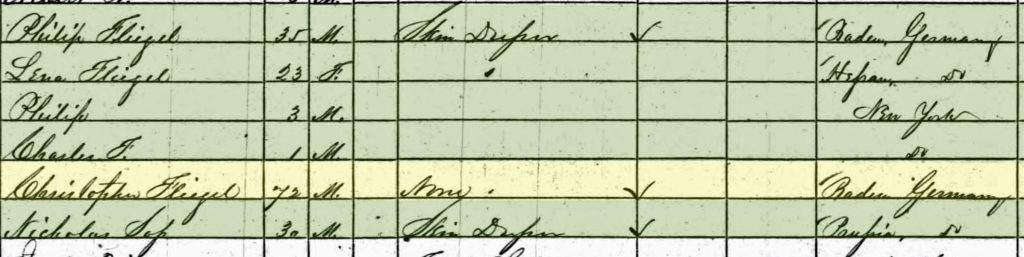

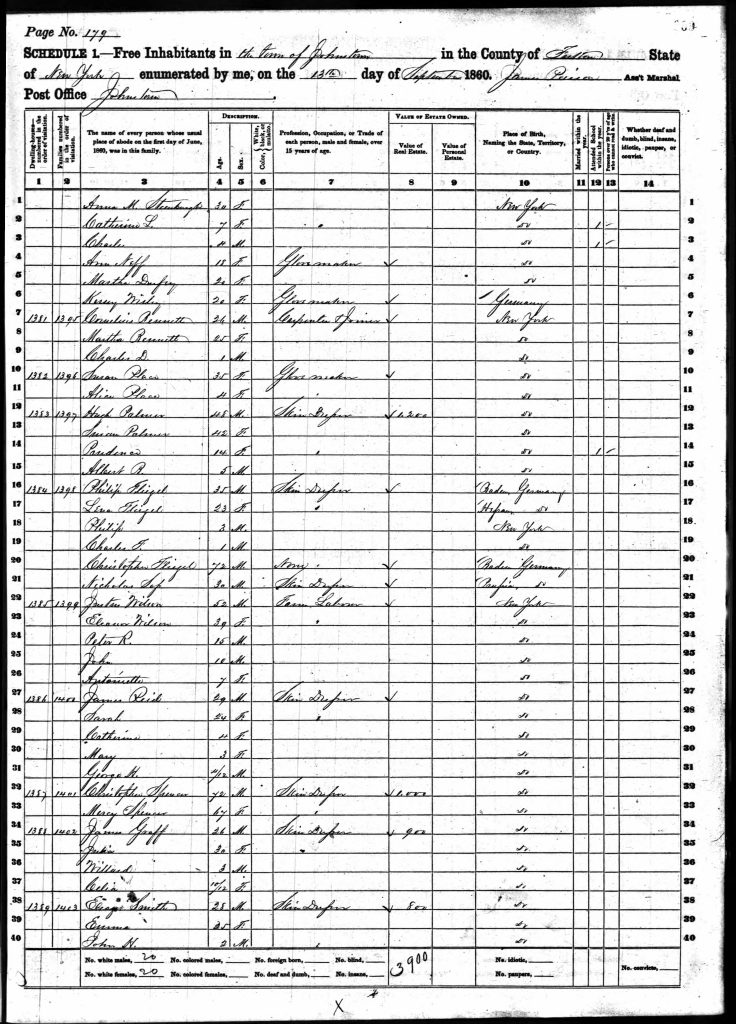

In five years after their arrival to the United States, the U.S. Federal Census captured a snapshot of the family in 1860. [69] Christopher, age 72, is living with this son Philip’s family. Philip’s occupation is listed as a “Skin Dresser”. [70]

Fliegel Household in Johnstown, NY 1860

As with all census enumerations, it provides a snapshot of the family’s unique configuration in time. By 1860, Christopher Flieger is reported as 72 years old. He is living with his son Philip Fliegel (age 35) and his young family. Maria Juliana (Wageneck) Fliegel is not listed in the census. Philip’s wife, Magdalen ‘Lena” (Edel) Fliegel was reported as 23 years old and they had two children Philip (age 3) and Charles F (age 1). It is not known when Philip and his wife Lena were married.

Christoph Fliegel lived long enough to see his family settled in the United States. He passed away at the reported age of 74 on October 15, 1862, which would have been only seven years after his arrival to the new land. “Christopher immigrated with his family to America in 1855. “Christopher was 73 years, 4 months and 19 days old.” [71] It is not known but doubtful if Christopher worked when he arrived in the United States or simply lived with his son. It is not known where Juliana lived after Christoph passed away.

His wife Juliana died at the reported age of 63 on February 23, 1867. [72]

With the exception of Catherine, Julia was able to witness the marriage of all of their children. At the end of their lives they were able to have the satisfaction of knowing their children had landed upright and were able to to start families of their own in a new country that provided a future.

Dates of Marriage

| Family Member | Date of Marriage | Spouse |

|---|---|---|

| Rosina Fliegel | 1866 | Louis Knoff |

| Philip Fliegel | 1856 | Magdalen Edel |

| Catherine Fliegel | 1850 | Henry Krause |

| Sophie Fliegel | 1857 | John Sperber |

A brief outline of the Fliegel family in America can be found in Cuyler Reynold’s Hudson-Mohawk Genealogical and Family Memoirs. [73]

Sources

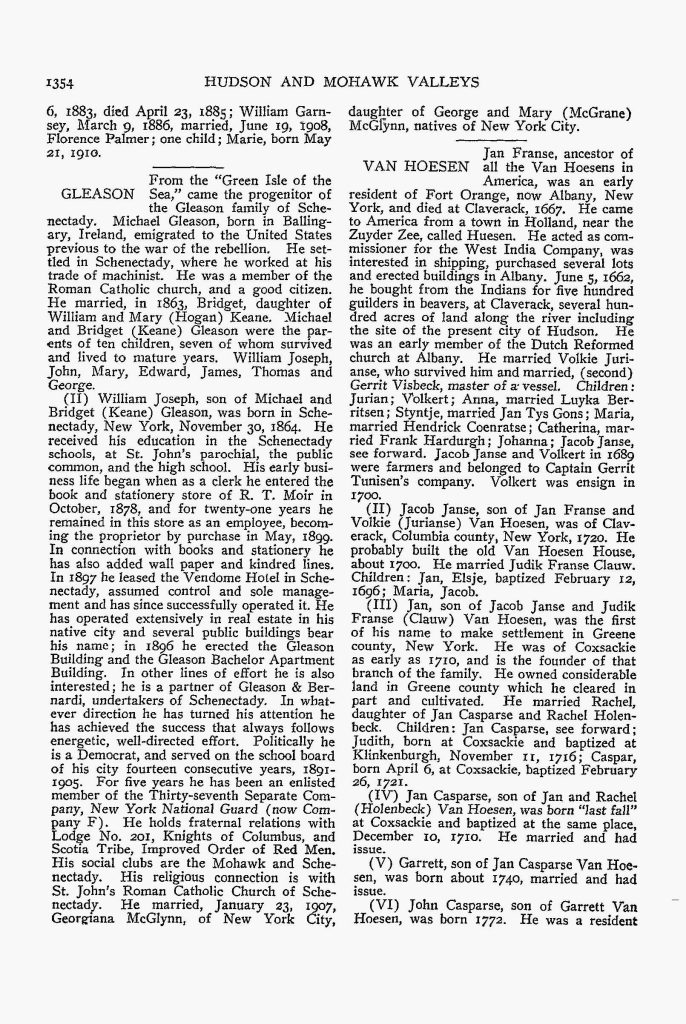

Feature Photograph: A portion of the Perspective map of Johnstown from 1888 by L.R. Burleigh with list of landmarks, Burleigh, L. R. (Lucien R.); Burleigh Litho; Burleigh, L. R., Johnstown, N.Y. 1888, Perspective map not drawn to scale. Bird’s-eye view. LC Panoramic maps (2nd ed.), 577 Available also through the Library of Congress Web site as a raster image. Includes illustration and index to points of interest. AACR2, From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository https://www.loc.gov/item/75694787/

[1] Six generations of the Fliegel family have lived in the United States since their head of the family and his four children immigrated in the mid 1800s. See the following PDF file of the Fliegel family tree. The PDF format allows the viewers to zoom in and out to view the family tree. For reasons of privacy I have not included the current relatives living the United States. The rendering of the family tree is based on the intellectual property rights of ancestry.com. See Fliegel family tree

[2] Chistoph Fluegel, birth date: 26 Mai 1788, baptism: 27 Mai 1788, Baptism place: Evangelisch, Ittlingen, Heidelberg, Baden, residence: Ittlingen, Heidelberg, Baden, father:Phillippe Fluegel, mother: Maria Elisabeth Poebeler, FHL Film Number: 1189133

Christoph Fluegel, marriage, 16 Jul 1818, Evangelisch, Ittlingen, Heidelberg, Baden, father: Philipp Flügel, Source: Juliana Wageneck, FHL Film Number 1272378, reference ID 2:w1T5SD

Maria Juliana Wageneck, birth: 14 Dez 1803 (14 Dec 1803), baptism 15 Dez 1803 (15 Dec 1803), baptism place Evangelisch, Ittlingen, Heidelberg, Baden, resdence: Ittlingen, Heidelberg, Baden, father: Johann Georg Wageneck, mother: Maria Elizabetha Zeigler, Film Number: 1189133

[3] Map Source: Störfix, Map of the Grand Duchy of Baden (Germany), from 1819 to 1918, 3 Mar 2006, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_Baden_(1819-1945).png

[4] Ancestry.com. Germany, Select Births and Baptisms, 1558-1898 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.Original data: Germany, Births and Baptisms, 1558-1898. Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 2013.

[5] Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: A New Surge of Growth, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/german/new-surge-of-growth/

[6] An example of transatlantic mail transported on a packet ship in 1844. Robert A. Siegel Auction galleries, Inc, 21 West 38th St, NY https://siegelauctions.com; Items up for auction – transatlantic mail packages. Thefllowing PDF is a copy of a series of peces of transatlantic mail that were being auctioned 26 Sep 2013. https://griffis.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/transatlantic-mail-1800s.pdf

[7] Seija-Riitta Laakso, Across the Oceans, Development of Overseas Business Information Transmission, 1815-1875, Helsinki: Helsinki University Printing House, 2006 https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7bea/f11c96cf9797721fd4aafafca8f334414c3a.pdf.

Regarding the amount of time it took for mail to travel from Europe to the United States:

“The average length of a westbound journey (of a packet ship with mail) was 34 days, but it varied very much from one journey to another. Even though there were slower and faster vessels, one and the same ship could make a westbound trip in 41 days and the following one in 22. It was not unusual that the vessels arrived in another order than they had left from the port of departure, even if there was one or two weeks difference between the sailing dates. Though it was true that winter sailings were harder and often longer than those of the spring or autumn (summer sailings often suffered from fog on the North American coast), even the winters were variable.” Page 50

Mail traveling from the United States to Europe was generally faster due to the prevailing ocean currents.

“The effect of prevailing winds was easily noticed in the duration of sea voyages across the North Atlantic, where the westbound journeys were always more difficult and the duration of sailings could be several weeks longer than on the eastbound journeys. …

“In fact, a sailing vessel’s journey from Liverpool to New York was nearly 500 miles longer than a vessel’s journey from New York to Liverpool. This was due to the prevailing westerly winds. No sailing vessel could travel directly into the wind, and the extra 500 miles came from the tacking while the vessel tried to beat her way to the westward … .” Page 29

Packet ships played so much of a major role in the transportation of international mail that English, French and American government readily accepted their central role in international communications in the mid 1800s.

“The American sailing packets accepted letters from England to the United States at two-pence a letter, irrespective of the weight or number of enclosures. The packet line agents provided mail bags in their Liverpool and London offices, and the bags were sealed when the vessel was due to sail, and taken on board. The same procedure was usual at Havre and Bordeaux on the French side. In England the practice was widespread and used by the majority of merchants throughout the kingdom.

“…. In the late 1830s it was revealed by Roland Hill, the Secretary of the Post Office, when advocating his postal reform, that the American sailing packets carried some 4,000 letters each westbound voyage, none of which had passed through the Post Office.” Page 48

“From late 1849 the United States took advantage of the U.S.-British Postal Convention of 1848 to send closed mails via England to Bremen when regular Bremen packets were not available. … In 1852 there were no less than 34 extra mails to Bremen by other mail ships – mainly by the American contract lines the Collins Line and the Havre Line.” Page 106

See also an examination of tracing a single letter: John J. McCusker, “New York City and the Bristol Packet. A chapter in eighteenth-century postal history”, in John J. McCusker, Essays in the Economic History of the Atlantic World (London 1997), 177-189

[8] Walter D. Kamphoefner, “Immigrant Epistolary and Epistemology: On the Motivators and Mentality of Nineteenth-Century German Immigrants,” Journal of American Ethnic History 28, no. 3 (Spring 2009): 34

[9] Seija-Riitta Laakso, Across the Oceans, Development of Overseas Business Information Transmission, 1815-1875, Helsinki: Helsinki University Printing House, 2006 https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7bea/f11c96cf9797721fd4aafafca8f334414c3a.pdf. Page 106

[10] Félix Krawatzek and Gwendolyn Sasse, Integration and Identities: The Effects of Time, Migrant Networks, and Political Crises on Germans in the United States. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 60(4), June 2018, 1029-1065. doi:10.1017/S0010417518000373 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/comparative-studies-in-society-and-history/article/abs/integration-and-identities-the-effects-of-time-migrant-networks-and-political-crises-on-germans-in-the-united-states/A5B951CA7AEB2C2C33958799C40FDDA2

See also other work of Krawatzek and Sasse where they developed a computer-aided textual analysis of about 6,000 letters sent between the US and Germany between 1830 and 1970. Their contents allowed the researchers to trace how migrants’ identities and transnational ties changed over the decades.

See: Félix Krawatzek and Gwendolyn Sasse, Writing home: how German immigrants found their place in the US, February 18, 20016, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/writing-home-how-german-immigrants-found-their-place-in-the-us-53342

Félix Krawatzek, Gwendolyn Sasse, The simultaneity of feeling German and being American: Analyzing 150 years of private migrant correspondence, Migration Studies, Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2020, Pages 161–188 https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mny014

Félix Krawatzek and Gwendolyn Sasse, Deciphering Migrants’ Letters, November 28, 2018, comparative Studies in Society and History, https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/cssh/tag/krawatzek/

Walter D. Kamphoefner, Wolfgang Helbich, et al., Editors., News from the Land of Freedom: German Immigrants Write Home (Documents in American Social History) : Cornell University Press, 1991.

[11] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City 1845-80, Urbana:University of Illinois Press, 1990, page 24.

This assessment has been reflected in a number of studies on German immigrants in the mid 1800’s in addition to Nadel’s seminal book that has been quoted. See for example:

Kamphoefner, Walter D. “Immigrant Epistolary and Epistemology: On the Motivators and Mentality of Nineteenth-Century German Immigrants.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 28, no. 3, 2009, pp. 34–54. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40543427

“Most German emigrants had incomes no lower than those earned by the lower middle class, creating an emigrant population from German states that was positively self selected in the 1840s and 1850.”

Cohn, Raymond L., and Simone A. Wegge. “Overseas Passenger Fares and Emigration from Germany in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Social Science History 41, no. 3 (2017): 393–413. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90017919.

Karl Dargel, Tyler Hoerr, Petar Milijic, Economic Migration: Tracing Chain Migration through Migrant Letters in an Economic Framework, Global Histories, Special Issue (Feb 2019) Pages 19 -30

[12] Karl Dargel, Tyler Hoerr, Petar Milijic, Economic Migration: Tracing Chain Migration through Migrant Letters in an Economic Framework, Global Histories, Special Issue (Feb 2019) Pages 23

[13] Kamphoefner, Walter D. “Immigrant Epistolary and Epistemology: On the Motivators and Mentality of Nineteenth-Century German Immigrants.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 28, no. 3, 2009, pp. 34–54. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40543427 .Accessed 26 Sept. 2023. Page 35

See also:

Karl Dargel, Tyler Hoerr, Petar Milijic, Economic Migration: Tracing Chain Migration through Migrant Letters in an Economic Framework, Global Histories, Special Issue (Feb 2019) Pages 19 -30, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/GHSJ.2018.308

Bade, Klaus J. “From Emigration to Immigration: The German Experience in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.” Central European History, vol. 28, no. 4, 1995, pp. 507–35. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4546551 Accessed 26 Sept. 2023.

Bergquist, James M. “German Communities in American Cities: An Interpretation of the Nineteenth-Century Experience.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 4, no. 1, 1984, pp. 9–30. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27500350 . Accessed 26 Sept. 2023.

Moltmann, Günter. “Migrations from Germany to North America: New Perspectives.” Reviews in American History, vol. 14, no. 4, 1986, pp. 580–96. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2702202 Accessed 26 Sept. 2023.

Helbich, Wolfgang. “German Research on German Migration to the United States.” Amerikastudien / American Studies, vol. 54, no. 3, 2009, pp. 383–404. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41158447 Accessed 26 Sept. 2023.

Wittke, Carl. “German Immigrants and Their Children.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 223, 1942, pp. 85–91. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1023790 . Accessed 26 Sept. 2023.

[14] Kamphoefner, Walter D. “Immigrant Epistolary and Epistemology: On the Motivators and Mentality of Nineteenth-Century German Immigrants.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 28, no. 3, 2009, pp. 34–54. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40543427 .Accessed 26 Sept. 2023. Page 47.

See also:

Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: Germans – A New Surge of Growth, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/german/new-surge-of-growth/

“A common theme underlying German immigration to North America was chain migration, the process by which generations of immigrants moved between two locales over a period of decades, creating transatlantic kinship and place-specific linkages, which often resulted in the transplantation of whole communities overseas.”

Timothy G. Anderson Ohio University, David j Wishart, ed, Germans, Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, Paged accessed 22 Sep 2023, http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.ea.013.xml

Frizzell, Robert W. “Migration Chains to Illinois: The Evidence from German-American Church Records.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 7, no. 1, 1987, pp. 59–73. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27500562. Accessed 22 Sept. 2023.

Simone A. Wegge, . “Occupational Self-Selection of European Emigrants: Evidence from Nineteenth-Century Hesse-Cassel.” European Review of Economic History, vol. 6, no. 3, 2002, pp. 365–94. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41377929 . Accessed 23 Sept. 2023.

Wegge, S. (1998). Chain Migration and Information Networks: Evidence From Nineteenth-Century Hesse-Cassel. The Journal of Economic History, 58(4), 957-986

“Chain migration produces not only more migration but different migrants. Migrants from over 1,300 different German villages are classified as networked and non-networked. The most definitive results from comparing the two types of migrants are the figures on cash assets because they support the model’s prediction that socially networked migrants needed less cash than non-networked migrants to accomplish their migration goals.”

[15] Karl Dargel, Tyler Hoerr, and Peter Milijic, Economic Migration: Tracing Chain Migration through Migrant Letters in an Economic Framework, Global Histories: A Student Journal , Special Issue (February 2019), pp. 19–30 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/GHSJ.2018.308

[16] History of Rail Transport in Germany, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 11 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_rail_transport_in_Germany.

Baden main line, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 26 February 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baden_main_line

J.H. Clapham, The economic development of France and Germany, 1815-1914, Cambridge: University Press, 1921. Pages 140- 157, https://archive.org/details/cu31924013709641/mode/2up

[17] G. Wolfgang Heinze, Heinrich H. Kill, The Development of the German Railroad System, G. Wolfgang Heinze, Heinrich H. Kill (1988): The Development of the German Railroad System. In: Mayntz, R.; Hughes, T. P. (Eds.): The Development of Large Technical Systems. (Schriften des Max- Planck-Instituts für Gesellschaftsforschung Köln ; 2). Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag. pp. 108

[18] Grand Duchy of Baden State Railway, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 21 August 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Duchy_of_Baden_State_Railway

See also:

List of the first German railways to 1870, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 2 August 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_the_first_German_railways_to_1870

History of rail transport in Germany. Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 11 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_rail_transport_in_Germany

History of railways in Württemberg, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 26 February 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_railways_in_Württemberg.

J.H. Clapham, The economic development of France and Germany, 1815-1914, Cambridge: University Press, 1921. Pages 140- 157, https://archive.org/details/cu31924013709641/mode/2up

Patrick O’Brien, Transport and Economic Development in Europe, 1789–1914. In: O’Brien, P. (eds) Railways and the Economic Development of Western Europe, 1830–1914. St Antony’s/Macmillan Series. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 1983 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-06324-6_1

Patrick O’Brien, Patrick, ed. Railways and the Economic Development of Western Europe 1830–1914 Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 1983

G. Wolfgang Heinze, Heinrich H. Kill, The Development of the German Railroad System, G. Wolfgang Heinze, Heinrich H. Kill (1988): The Development of the German Railroad System. In: Mayntz, R.; Hughes, T. P. (Eds.): The Development of Large Technical Systems. (Schriften des Max- Planck-Instituts für Gesellschaftsforschung Köln ; 2). Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag. pp. 105-134. Also https://doi.org/10.14279/depositonce-7262

[19] Grand Duchy of Baden State Railway, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 21 August 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Duchy_of_Baden_State_Railway

Rhine Bridge, Kehl, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 25 February 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhine_Bridge,_Kehl#

[20] Baden Main Line, Wikipedia, Page was updated 23 Feb 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baden_main_line

[21] Grand Duchy of Baden State Railway, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 21 August 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Duchy_of_Baden_State_Railway

[22] Standard-gauge railway, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 20 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard-gauge_railway

Baden main line, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 26 February 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baden_main_line

[23] Rhine Bridge, Kehl, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 25 February 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhine_Bridge,_Kehl

[24] Nicolas, P, Brief History of Railway Speed progress, Jan 31, 1976, National Academies Sciences Engineering Medicine, https://trid.trb.org/view/13670

[25] History of rail transport in France, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 11 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_rail_transport_in_France

Paris-Est–Strasbourg-Ville railway, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 14 June 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris-Est–Strasbourg-Ville_railway

[26] Michael Mille, Europe and the Maritime World: A Twentieth-century History, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012, Page 25, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139170048.001

[27] Canal De La Marne Au Rhin, French Waterways, https://www.french-waterways.com/waterways/north-east/marne-rhin/

[28] Adaptation of a map originally created by Ulamm, Development of the French railway network up to 1860, 25 August 2009 Creative Commons License, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:France1860railways.png

[29] Map 1 Hamburg–Le Havre range and its waterways, from Michael Mille, Europe and the Maritime World: A Twentieth-century History, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012, Page 27, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139170048.001

[29a] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration 1607 – 1860. Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press, 1941, Page 186

[30] Paris–Le Havre railway, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 1 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris–Le_Havre_railway# [26]

[31] The Great Viaduct of Barentin, on the Rouen and Havre Railway Illustration for The Illustrated London News, 24 January 1846

[32] Hein A. M. Klemann & D.M. Koppenol, Port Competition within the Le Havre Hamburg Range (185- 2-13), Dec 2013, Page 1; In book: Smart Port Perspectives. Essays in honor of Hans SmitsChapter: Port Competition with the Le-Havre-Hamburg range (1850-2013)Publisher: Erasmus Smart at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259786016

History of Le Havre, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 29 May 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Le_Havre#cite_note-18

[33] Sam Davies, Colin Davis, David de Vries, Lex Heerma van Voss, Lidewij Hesselink and Klaus Weinhauer, Eds, Dock Workers: International Explorations in Comparative Labour History, 1790 – 1970, Volume 1, New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2000; Chapter Four: John Barzman, Dock Labour in Le Havre 1790 – 1970, Page 62

[34] Kathi Gosza, Look at Le Havre, a Less-Known Port for German Emigrants, Blog Post, Dec 9 2011, http://19thcenturyrhinelandlive.blogspot.com/2011/10/look-at-le-havre-less-known-port-for.html

GHS, Emigration Documents, Havre as Emigration Port (Part 1: 1817 – 1860), http://www.genhist.org/ghs_Havre_eng.htm

[35] Sam Davies, Colin davis, David de Vries, Lex Heerma van Voss, Lidewij Hesselink and Klaus Weinhauer, Eds, Dock Workers: International Explorations in Comparative Labour History, 1790 – 1970, Volume 1, New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2000; Chapter Four: John Barzman, Dock Labour in Le Havre 1790 – 1970, Page 73

[36] David S. Barnes, The Making of a Social Disease: Tuberculosis in Nineteenth-Century France. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1995 1995. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft8t1nb5rp/. Chapter 6: Le Havre, Tuberculosis Capital of the Nineteenth Century

[37] Ibid, David S. Barnes, The Making of a Social Disease, Chapter 6

[38] Gregory Saillard, Discovery of an unknown daguerreotype from old Le Havre: “The quai de la Citadelle circa 1845-1848” , 11 Jan 2023, The Classic, https://theclassicphotomag.com/discovery-daguerreotype-le-havre/

Seaports – Sea Captains, The Maritime Heritage Project – San Francisco 1846 – 1899, Home Port, France: La Havre https://www.maritimeheritage.org/ports/France-Le-Havre.html

[38b] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration 1607 – 1860. Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press, 1941, Page 188

[39] Gregory Saillard, Discovery of an unknown daguerreotype from old Le Havre: “The quai de la Citadelle circa 1845-1848” , 11 Jan 2023, The Classic, https://theclassicphotomag.com/discovery-daguerreotype-le-havre/

[39a] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration 1607 – 1860. Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press, 1941, Page 187

[40] The exact 1837 French legal requirement for a valid travel ticket for German immigrants traveling to the United States has not been located but it has been discussed in a number of internet based articles, for example:

Seaports – Sea Captains, The Maritime Heritage Project – San Francisco 1846 – 1899, Home Port, France: La Havre https://www.maritimeheritage.org/ports/France-Le-Havre.html

Kathi Gosza, Look at Le Havre, a Less-Known Port for German Emigrants, Blog Post, Dec 9 2011, http://19thcenturyrhinelandlive.blogspot.com/2011/10/look-at-le-havre-less-known-port-for.html

GHS, Emigration Documents, Havre as Emigration Port (Part 1: 1817 – 1860), http://www.genhist.org/ghs_Havre_eng.htm

[40a] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration 1607 – 1860. Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press, 1941, Page 188

[41] Ira Glazier, Ed., Germans to America Series II: Lists of Passengers Arriving at U.S. ports in the 1840s, Volume 6 April 1848 – October 1848, Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc 2003, Page xiii

[42] GHS, Emigration Documents, Havre as Emigration Port (Part 1: 1817 – 1860), http://www.genhist.org/ghs_Havre_eng.htm

The following table is an English translation of the French chart found in Jean Braunstein, Annales de Normandie , L’émigration allemande par le port du Havre au XIXe siècleAnnée , 1984 34-1 pp. 95-104

[43] Fairburn, William A. (1945a). Merchant sail, vol. 2. Center Lovell, Me: Fairburn Marine Educational Foundation. Page 1216

See also:

Packet boat, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 3 October 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Packet_boat.

Packet trade, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 24 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Packet_trade

Aboard a Packet, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian, https://americanhistory.si.edu/on-the-water/maritime-nation/enterprise-water/aboard-packet.

Robert McNamara, Packet ship Ships That Left Port On Schedule Were Revolutionary In the Early 1800s, ThoughtCo., 6 Mar 2017, Updated 29 Jan., 2020, https://www.thoughtco.com/packet-ship-definition-1773390

Robert Foley, The Charles Cooper: The Only Surviving American Packet Ship, Bridgeport History Center, https://bportlibrary.org/hc/business-and-commerce/the-charles-cooper-the-only-surviving-american-packet-ship/

Edward Sloan, Packet Boats, History of World Trade Since 1450, Encyclopedia.com, 18 Sep 2023, https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/packet-boats.

John A. Tilley, Packets, Sailing, Dictionary of American History, encyclopedia.com, 19 Sep 2023, https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/packets-sailing.

Cutler, Carl C. Queens of the Western Ocean: The Story of America’s Mail and Passenger Sailing Lines. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1961.

[44] Quote from: Genealogy Packet Boats, ships were backbone of U.S. Water travel, Tribune-Star, April 24, 2014, https://www.tribstar.com/features/history/genealogy-packet-boats-ships-were-backbone-of-u-s-water-travel/article_8033a7a5-947c-5e62-ba27-4ef854ca0343.html

[45] Black Ball Line (trans-Atlantic packet), Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 24 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Ball_Line_(trans-Atlantic_packet)

[46] Ibid.

[47] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Havre-Union_Line, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 24 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Havre-Union_Line

Havre Second Line, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 27 August 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Havre_Second_Line#CITEREFFairburn1945a

Havre-Union Line (trans-Atlantic packet), Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 17 May 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Havre-Union_Line_(trans-Atlantic_packet)

[47a] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration 1607 – 1860. Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press, 1941, Page 188

[47b] Ibid, Page 188

[48] Passage Contract – Le Havre to New York – 4 May 1854, Gjenvick Gjønvik Archives, https://www.ggarchives.com/Immigration/ImmigrantTickets/1854-05-09-SteeragePassageContract-LeHavreToNewYork.html

[49] Thomas W. Page, The Transportation of immigrants and Reception Arrangements in the Nineteenth Century. Journal of Political Economy, Volume 19, Issue 9 Nov., 1911, Pages 737 https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/epdfplus/10.1086/251922

[50] Ibid, Page 738.

[51] Immigration & Steamships, Mystic Seaport, the Museum of America and the Sea, https://research.mysticseaport.org/exhibits/immigration/.

William Henry Webb Shipyards, Shipbuilding History Mar 29 2012, http://shipbuildinghistory.com/shipyards/19thcentury/webb.htm

William H. Webb, Shipbuilder and Philanthropist, Webb Institute, https://www.webb.edu/about-webb-institute/william-webb/

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “William Henry Webb”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 15 Jun. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Henry-Webb

[52] American Lloyd’s Register of American and Foreign Shipping, New York: E & G.W. Blunt, Clayton & Ferris Printers, 1859, Page 93 https://research.mysticseaport.org/item/l0237571859/#29

[53] Havre-Union Line (trans-Atlantic packet), Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 17 May 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Havre-Union_Line_(trans-Atlantic_packet)

[54] Seija-Riitta Laakso, Across the Oceans, Development of Overseas Business Information Transmission, 1815-1875, Helsinki: Helsinki University Printing House, 2006 https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7bea/f11c96cf9797721fd4aafafca8f334414c3a.pdf. Page 50

[55] Model of American packet ship ZURICH, full model, marad; models, wood; metal; textile; Overall: 21 5/8 x 29 1/4 x 8 1/4 in., Rigged model of the American packet ship ZURICH. Green bottom, port painted, black trim. Collections and Research, Mystic Seaport Museum, http://mobius.mysticseaport.org/detail.php?module=objects&type=related&kv=182465

[56] Lizard Point, Cornwall, Wikipedia, Page last updated 22 Dec 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lizard_Point,_Cornwall

[57] Christoph Fliegel (age 60), Juliani (59), Phillipp (33), Rosina (28) and Sophie (21) from Baden Germany, Year: 1855; Arrival: New York, New York, USA; Microfilm Serial: M237, 1820-1897; Jan 26, 1855, Page One, Lines: 3-7; List Number: 53, Ship or Roll Number: Zurich

New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957, Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Microfilm Publication T715, 8892 rolls. NAI: 300346. Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service; National Archives at Washington, D.C. Supplemental Manifests of Alien Passengers and Crew Members Who Arrived on Vessels at New York, New York, Who Were Inspected for Admission, and Related Index, compiled 1887-1952. Microfilm Publication A3461, 21 rolls. NAI: 3887372. RG 85, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service; National Archives, Washington, D.C. Index to Alien Crewmen Who Were Discharged or Who Deserted at New York, New York, May 1917-Nov. 1957. Microfilm Publication A3417. NAI: 4497925. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Passenger Lists, 1962-1972, and Crew Lists, 1943-1972, of Vessels Arriving at Oswego, New York. Microfilm Publication A3426. NAI: 4441521. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7488/images/NYM237_150-0080?pId=1184419 ;

[58] See the full manifest list – PDF file

[59] “View of Shipping on the East River from Fulton Market, Brooklyn in the Distance” E. & H. T. Anthony & Co. USA, NY, New York 1860 paper 3-1/4 x 6-3/4 in. Stereograph; printed on label on back “ANTHONY’S INSTANTANEOUS VIEWS,/ No. 209./ VIEW OF SHIPPING ON THE EAST RIVER FROM FULTON MARKET, BROOKYN/ IN THE DISTANCE./ Published by E. Anthony, 501 Broadway, New-York.”; New York City, Black Ball Line packet ships, 1860, Fulton Market in foreground with stalls for fish merchants Comstock & Harris, Crocker & Haley, and Fowler & Pearsall. Mystic seaport Museum, http://mobius.mysticseaport.org/detail.php?module=objects&type=related&kv=58591