A letter from the U.S. Adjutant General’s Office, which tersely documents the military history of Daniel Griffis, succinctly states the theme of this story. [1]

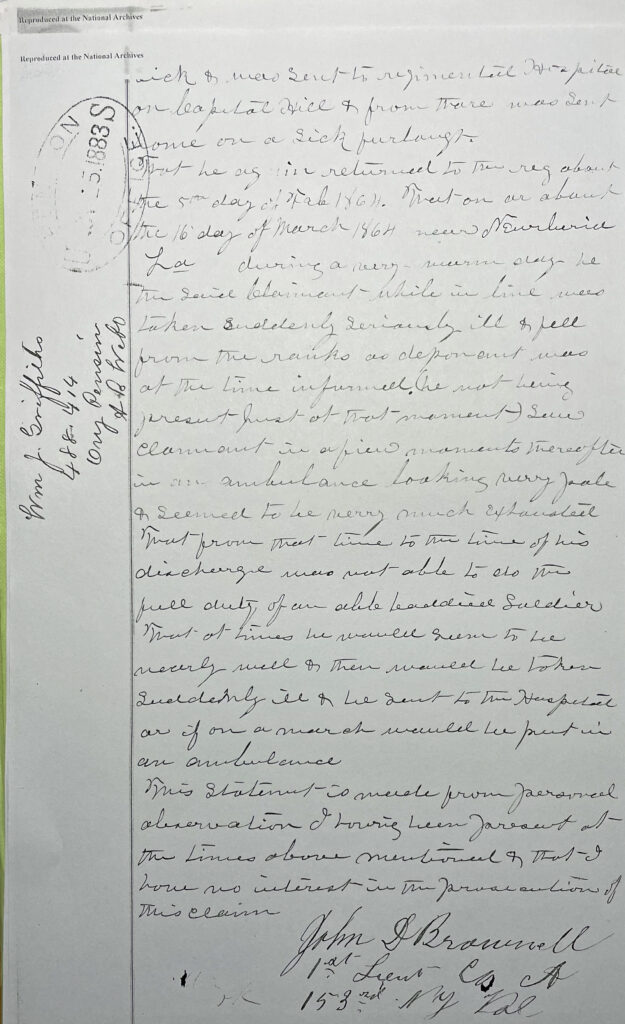

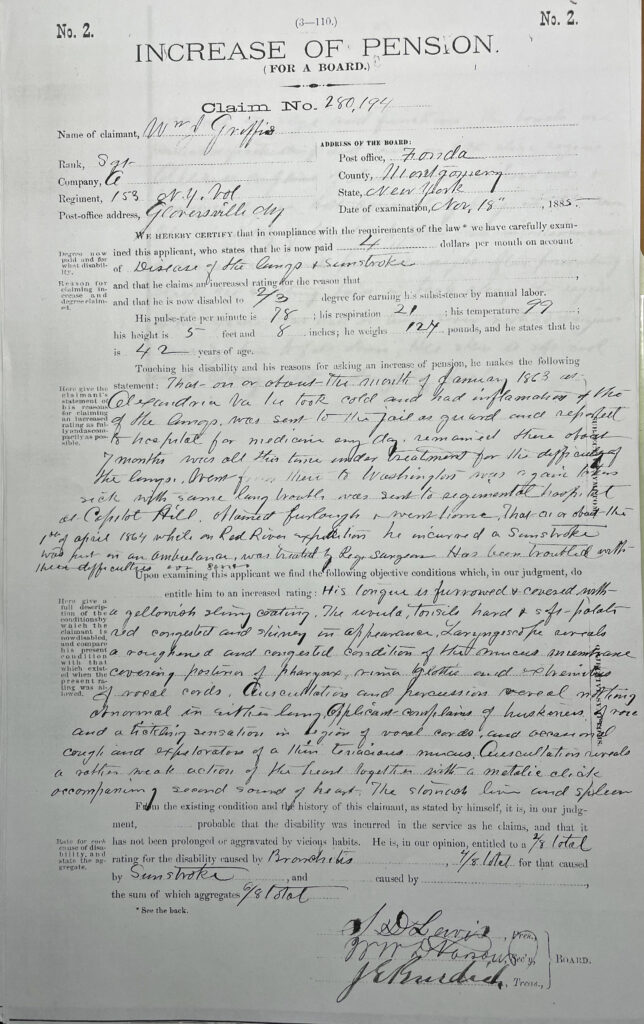

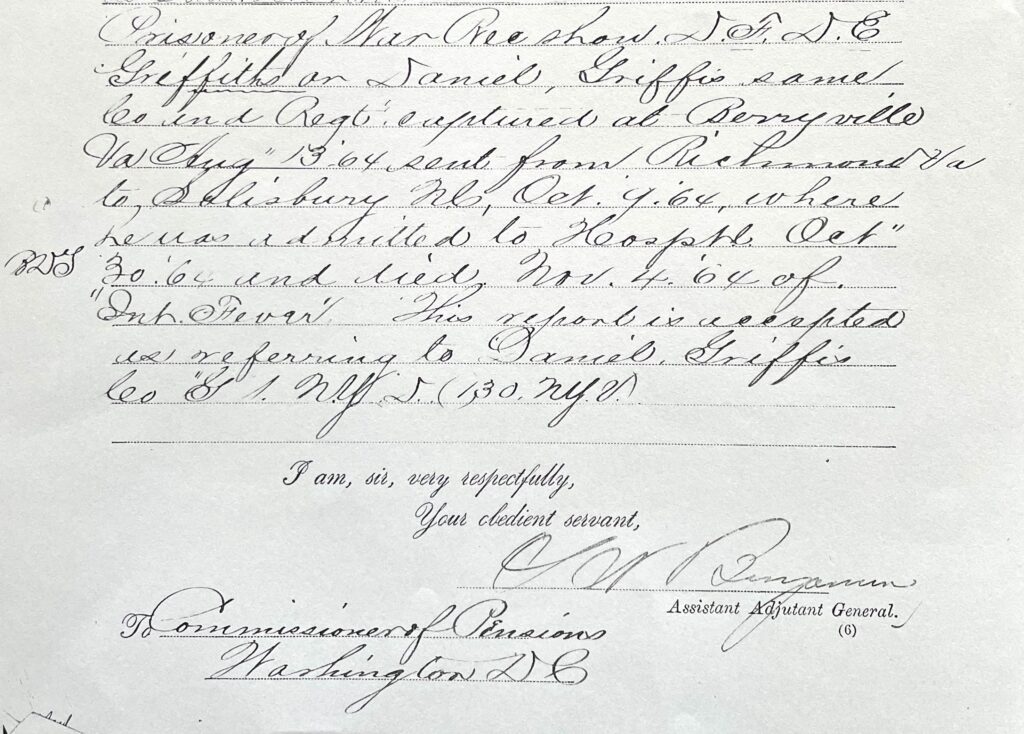

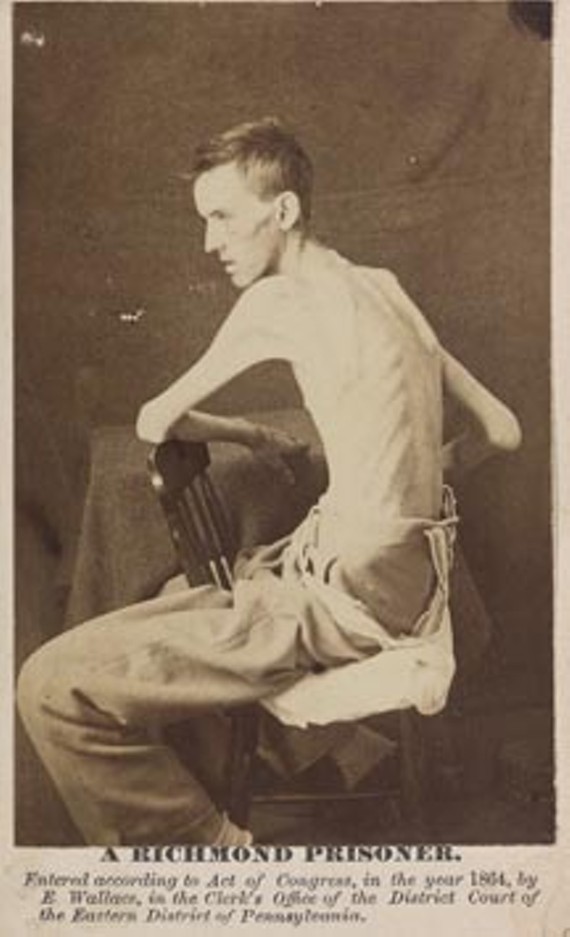

Prison of War Records show a D.F. or D.E. Griffiths or Daniel Griffis same Co. and Regiment Daniel Griffis, captured at Berryville, Virginia on August 13, 1864. He was transported to Richmond, Virginia and placed in a Confederate prison. He was then sent from Richmond, Virgina to Salisbury North Carolina on October 9, 1864. While in the Salisbury Prison, he was admitted to the prison hospital October 30, 1984 and died November 4, 1864 of “Int. fever”. “Int” or “intermittent fever” in Civil War medical parlance usually referred to recurring fevers. “Intermittent fevers” was a term that was used for a variety of illnesses, notably malaria. [2] The Adjutant General Office’s letter indicates that Confederate prison records misspelled Daniel’s name as “D.F. D.E. Griffiths”. [3]

This story follows the lead up to and capture of Daniel Griffis by Mosby’s Raiders, his imprisonment in Richmond, Virginia and his subsequent transfer to the Salisbury Confederate Prison.

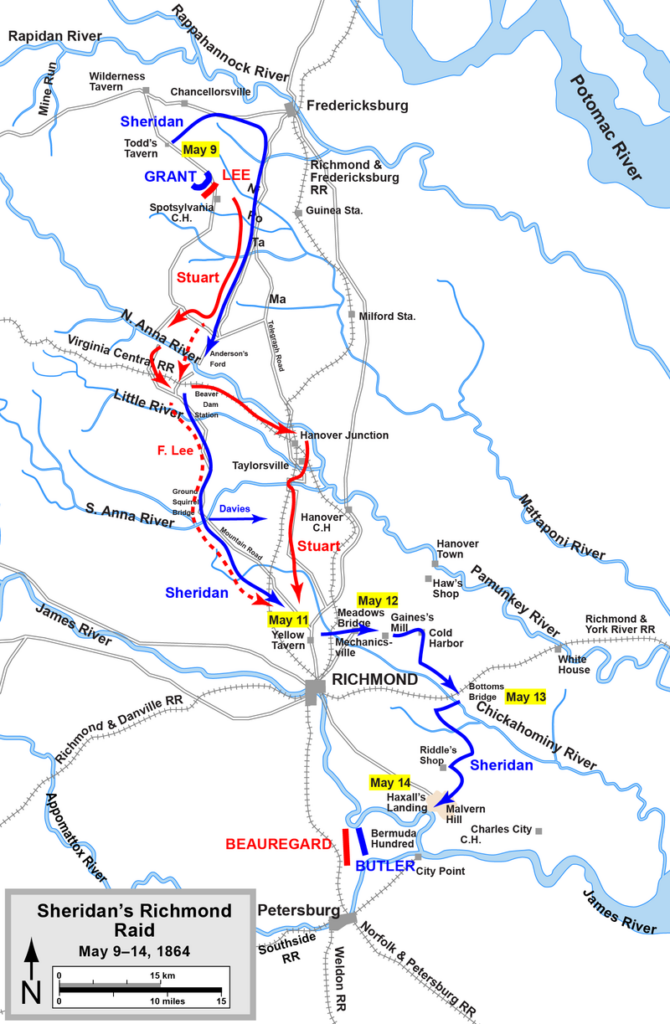

First Dragoons with Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley

Daniel Griffis was a private in the First New York Dragoons. He was an infantryman for the first year of his three year tour of duty as part of the 130th infantry regiment of the New York Volunteers. Then the regiment was transformed into a calvary unit and he became a wagon master at the end of 1863. Read More about the First Dragoons.

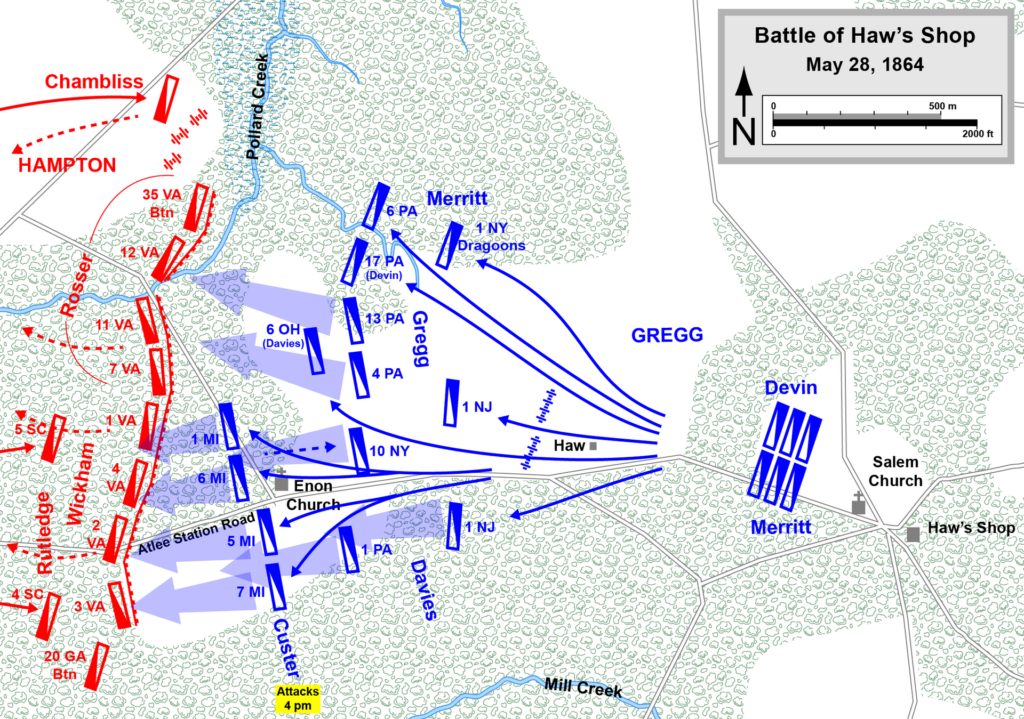

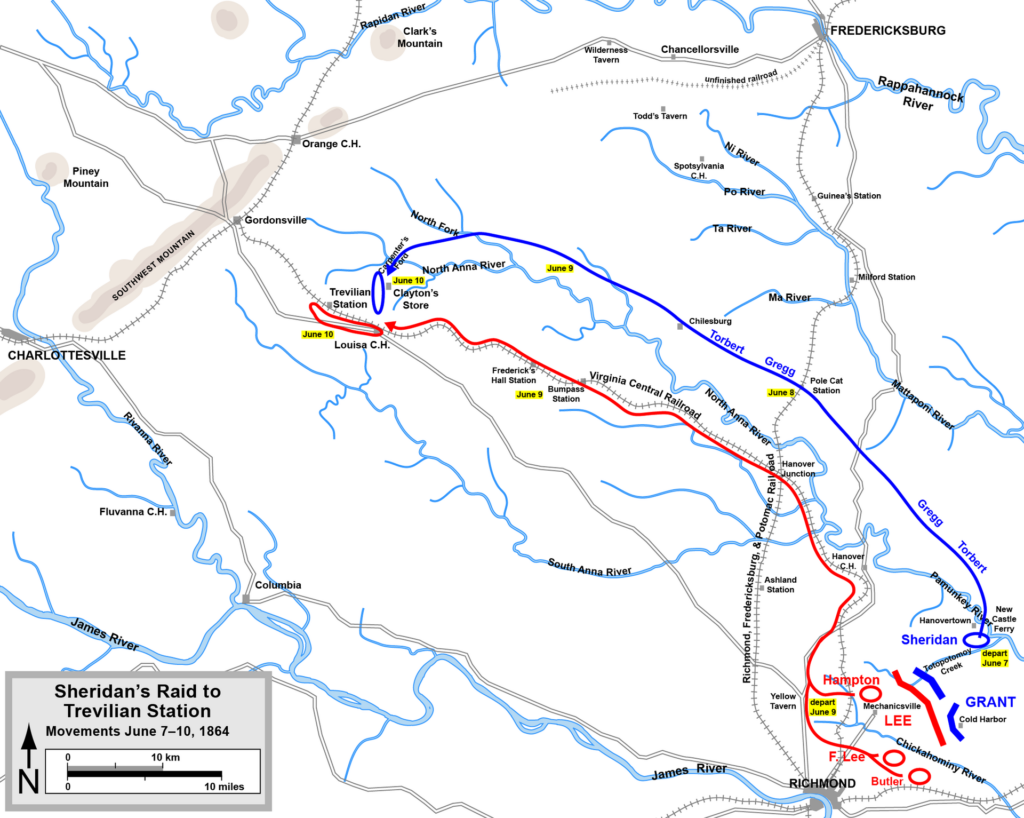

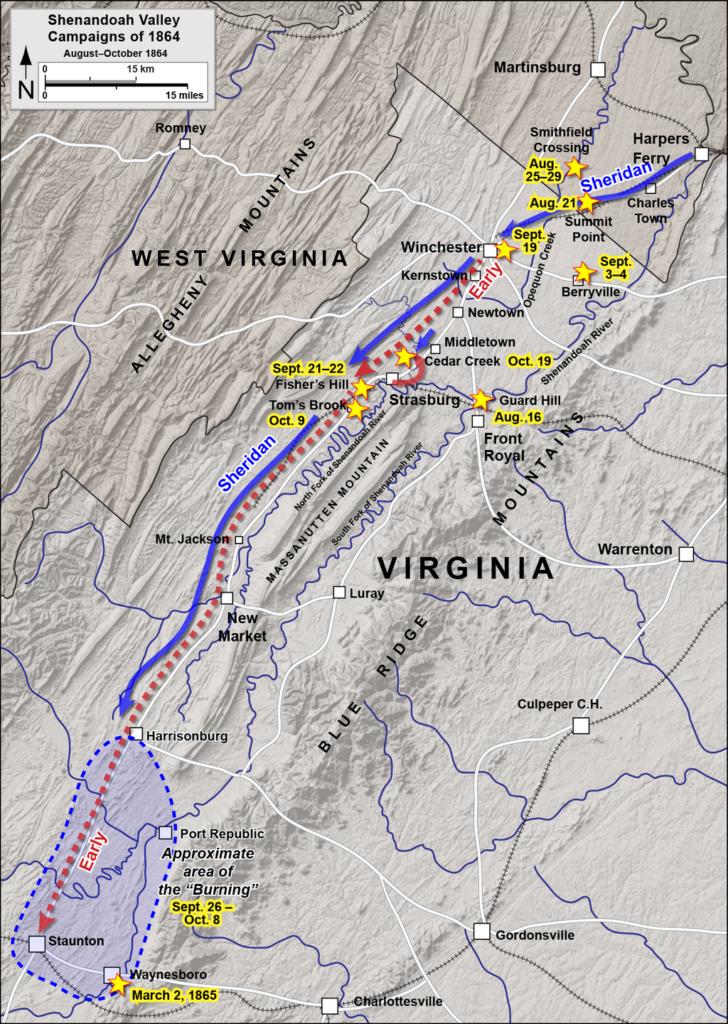

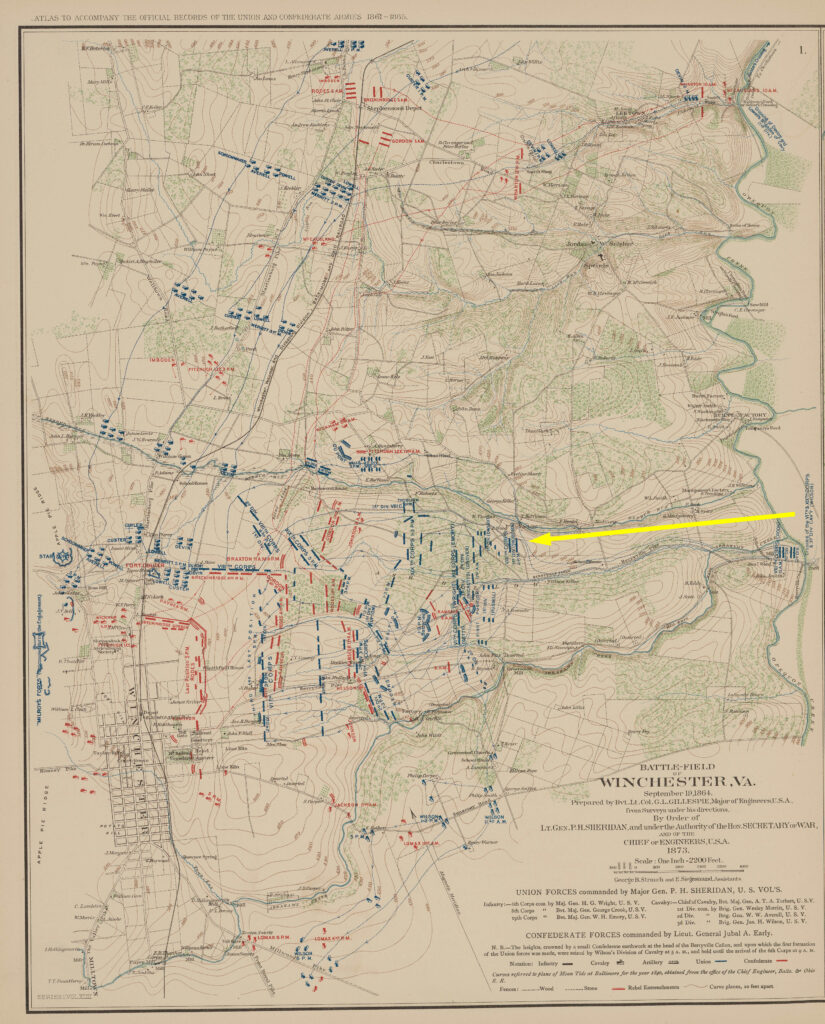

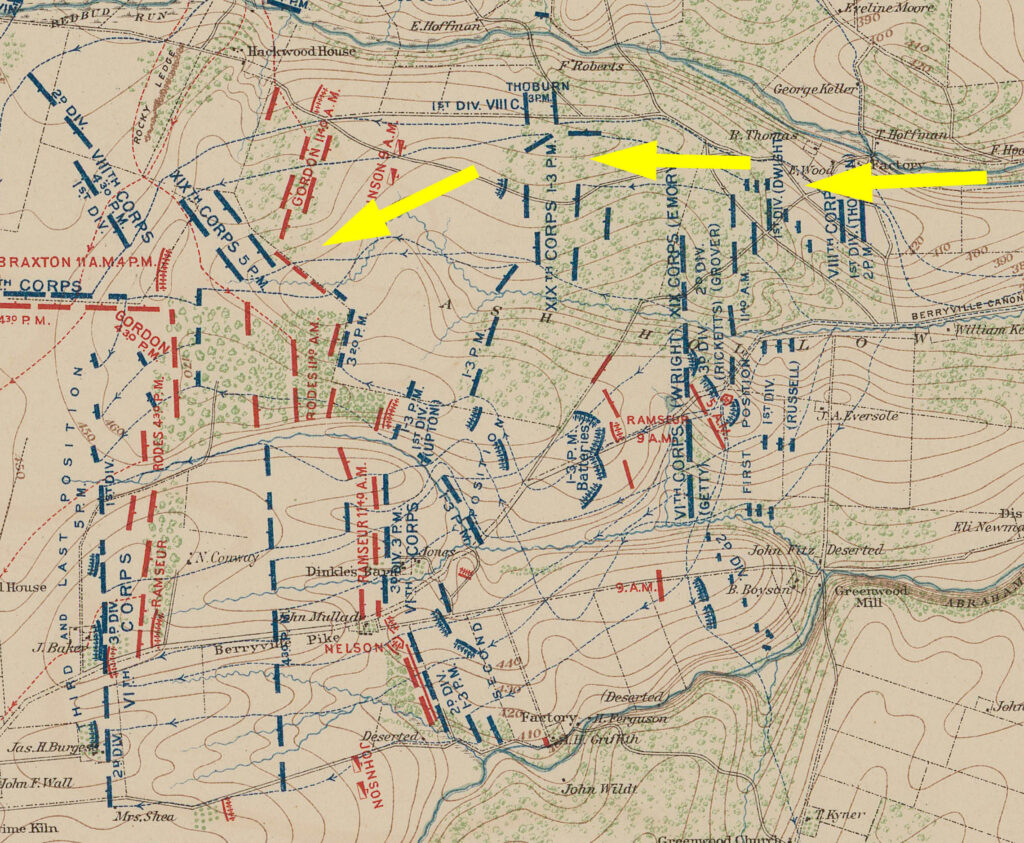

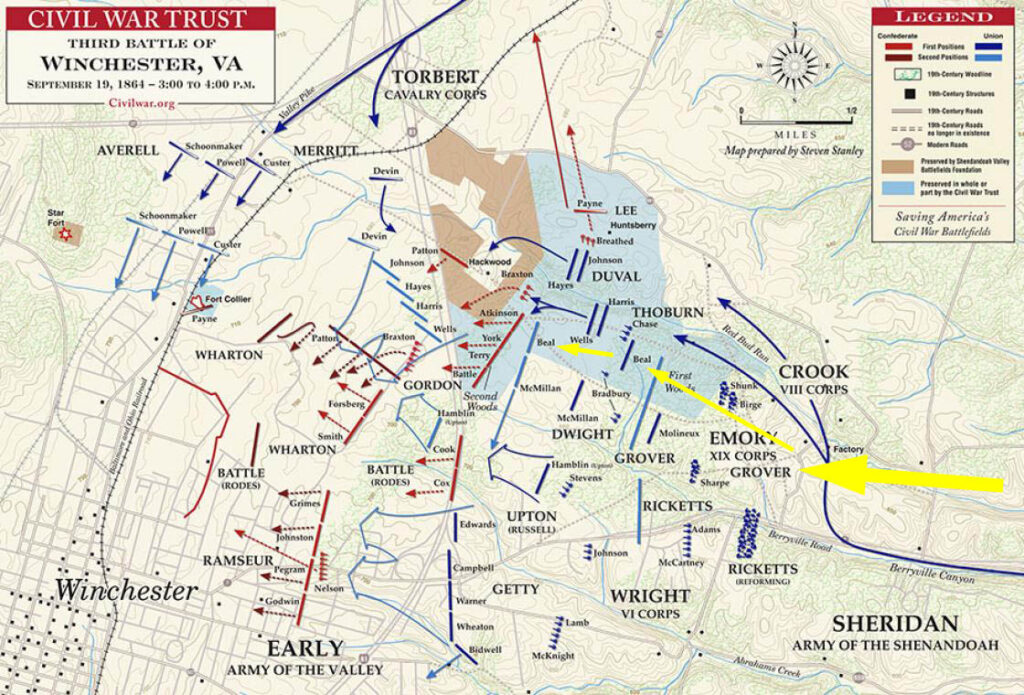

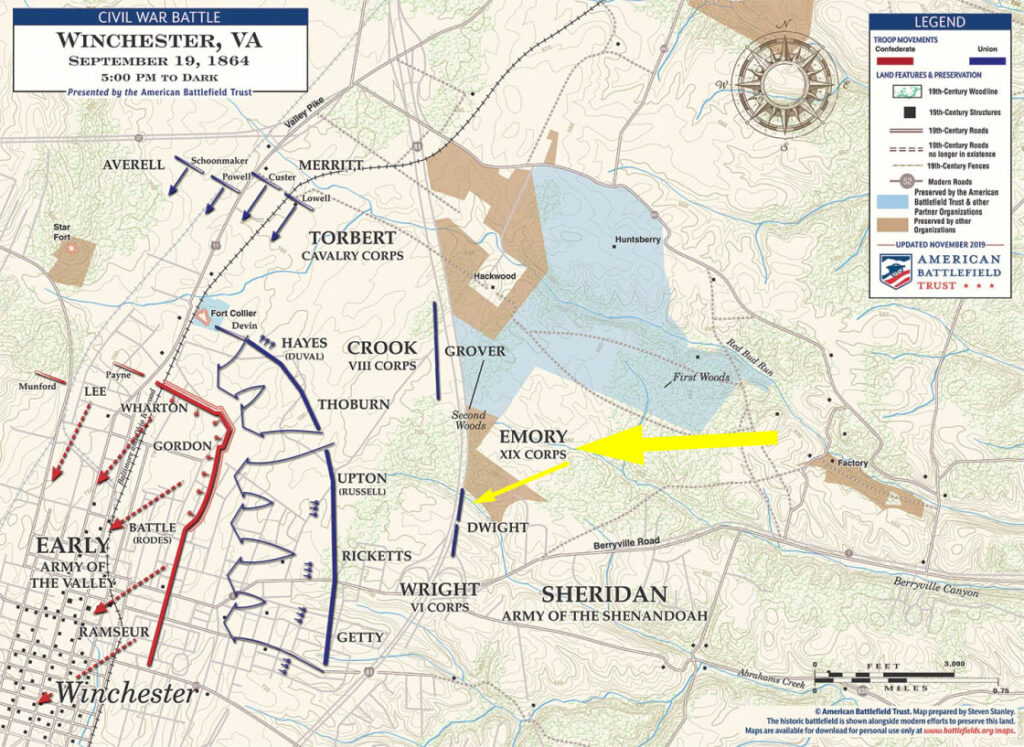

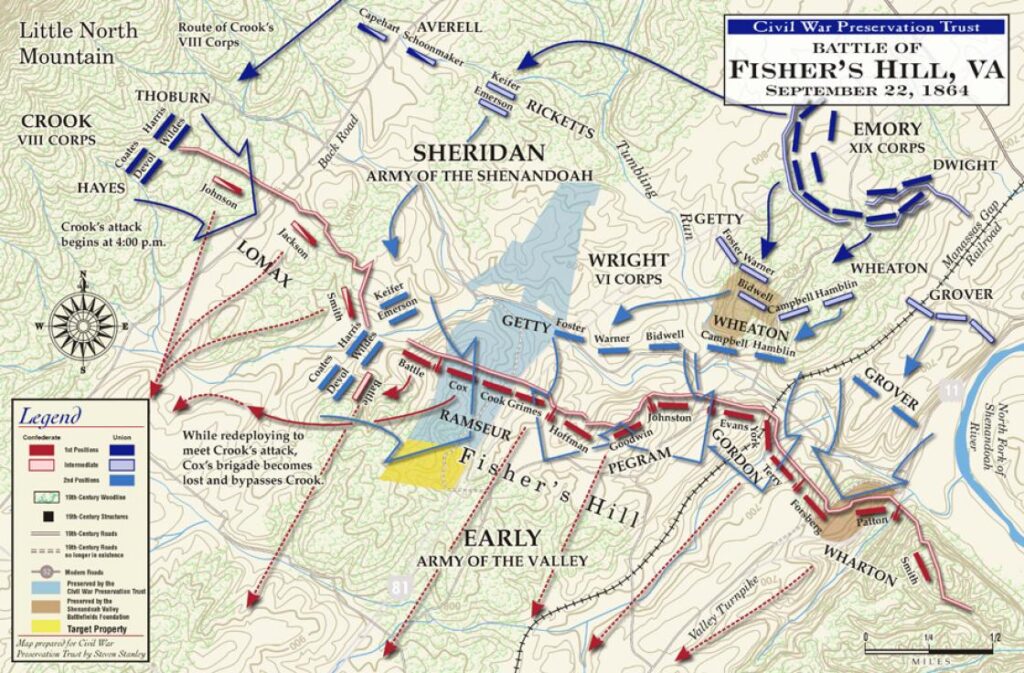

Daniel Griffis’ capture was at the beginning of General Sheridan’s Army of the Shenandoah campaigns that took place from August to October 1864. Leading up to his capture, Daniel’s regiment, the First New York Dragoons, was heavily involved in major battles and skirmishes at the front end of Sheridan’s campaigns in 1864 in the Shenandoah valley.

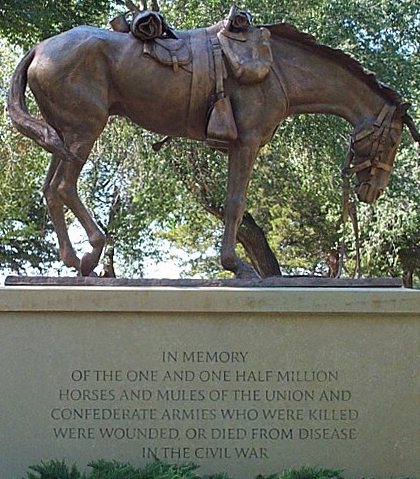

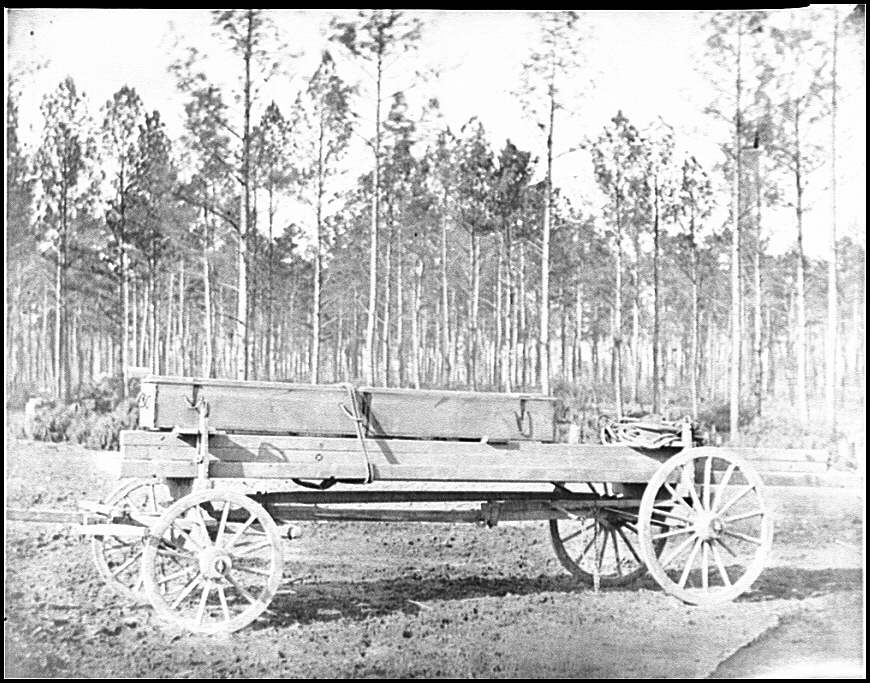

All throughout these campaigns, as part of the First New York Dragoons regiment, Daniel Griffis was driving a team of mules on a supply, ammunition, or ambulance wagon. Depending on the strategic circumstances of battle, he may have been part of a company, regimental, brigade, division or corps wagon train.

The days were undoubtably long and labor intensive when in action. Daniel’s marching orders were determined by whether the troops were approaching or retiring from the Confederates. His wagon train was placed to be as far as possible or practical from danger but close enough to the calvary and infantry to provide ammunition, supplies or assistance for the wounded. If he was driving a munitions or ambulance wagon, he was expected to go back and forth as safely as possible to resupply troops or pick up wounded soldiers.

At the end of a given day, under the command of a quartermaster, the wagons were parked in fields to avoid obstructing roads. Supplies were dispensed, wagons were repaired, attention was given to the care of the mules. Fences were torn down and ditches were filled in to facilitate their early start the next day.

Delays in long marches would tire the mule teams . Operational orders of the Union army underscored the need to feed and water the mules during those delays to keep them ‘in good heart’.

As General Ulysses Grant recalled:

“There never was a corps better organized than was the quartermaster’s corps with the Army of the Potomac in 1864. With a wagon-train that would have extended from the Rapidan to Richmond, stretched along in single file and separated as the teams necessarily would be when moving, we could still carry only about three days forage and about ten day to twelve days rations, besides a supply of ammunition. To overcome all difficulties, the chief quartermaster, General Rufus Ingalls, had marked on each wagon the corps badge with the division color and the number of the brigade. At a glance, the particular brigade to which any wagon belonged could be told. The wagons were also marked to note the contents: if ammunition, whether for artillery or infantry; if forage, whether grain or hay; if rations, whether bread, pork, beans, rice, sugar, coffee or whatever it might be. Empty wagons were never allowed to follow the army or stay in camp. As soon as a wagon was empty it would return to the base of supply for a load of precisely the same article that had been taken from it. Empty trains were obliged to leave the road free for loaded ones. Arriving near the army they would be parked in fields nearest to the brigades they belonged to. Issues, except of ammunition, were made at night in all cases. By this system the hauling of forage for the supply train was almost wholly dispensed with. They consumed theirs at the depot.” [4]

Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley campaign (August–October 1864)

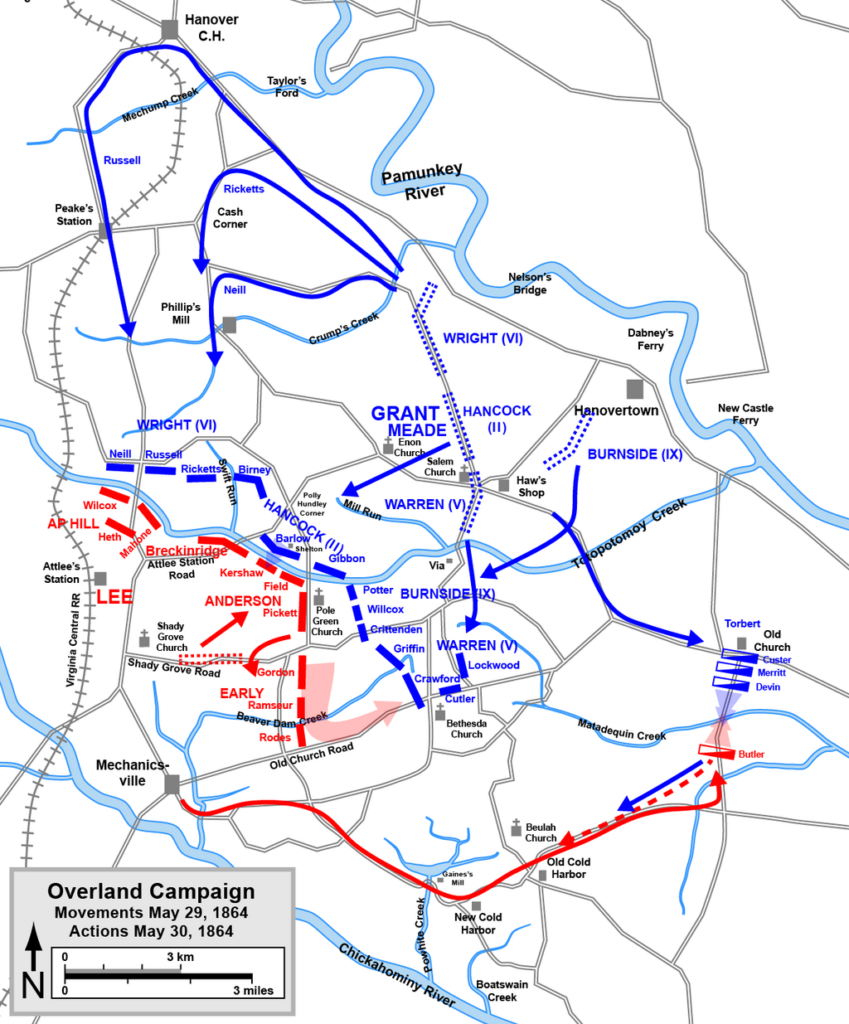

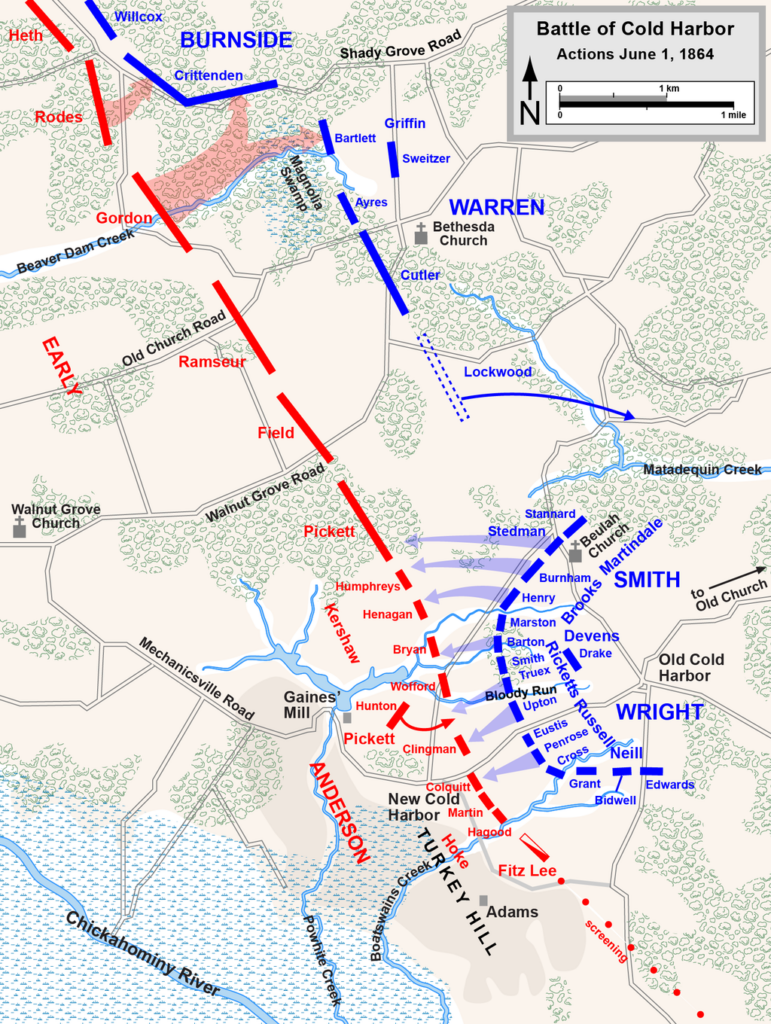

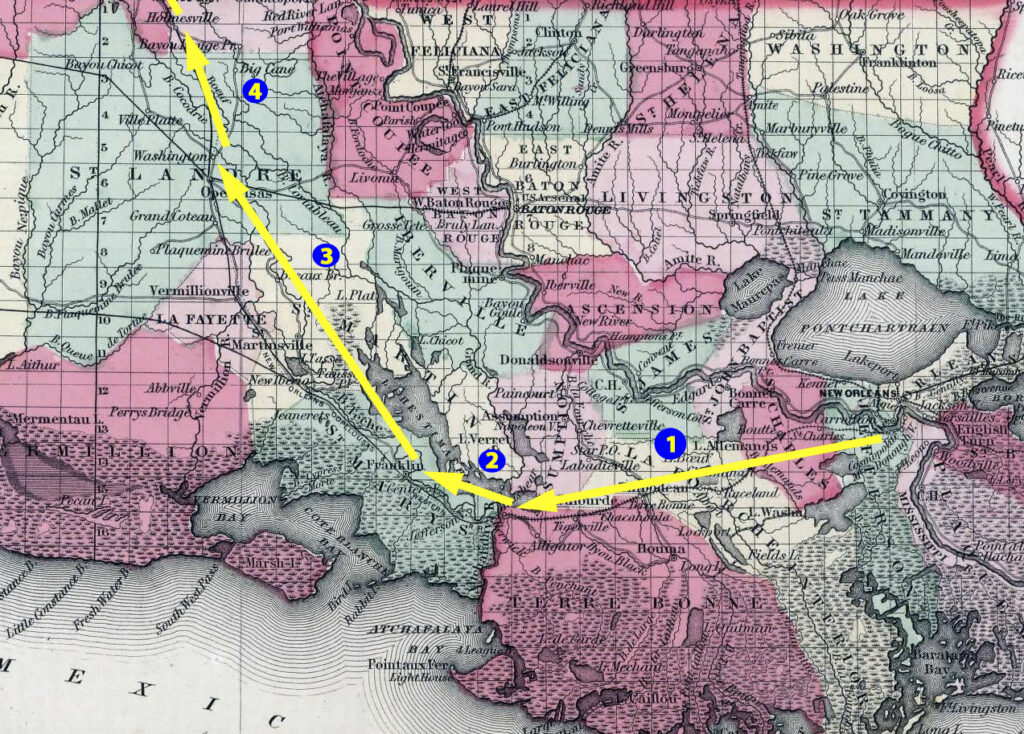

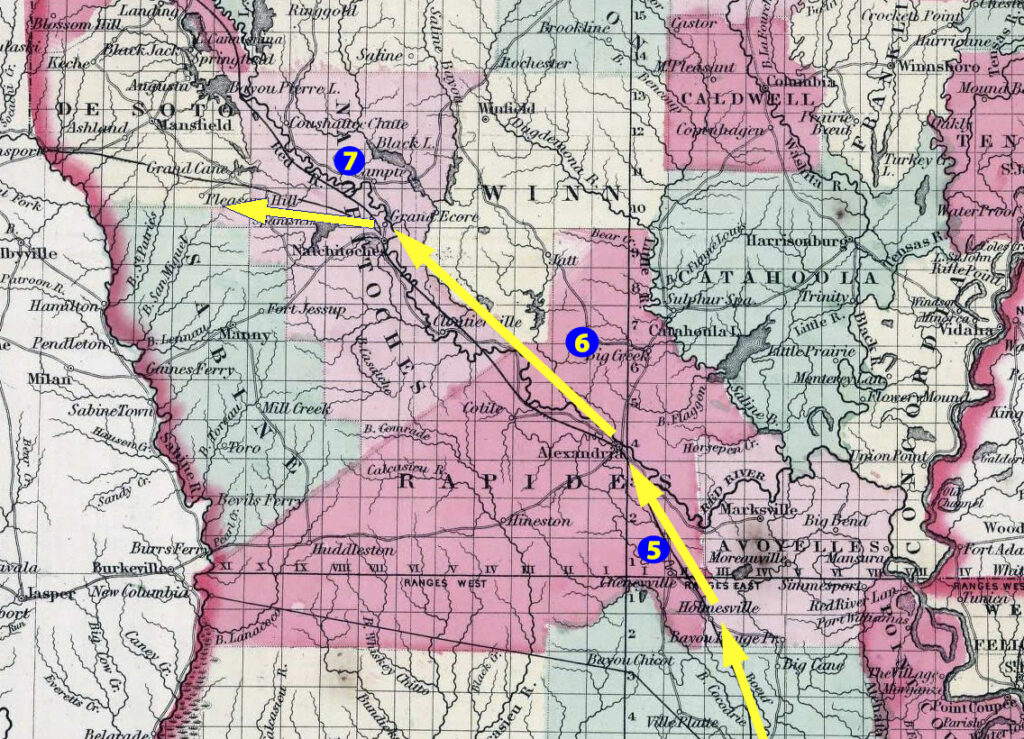

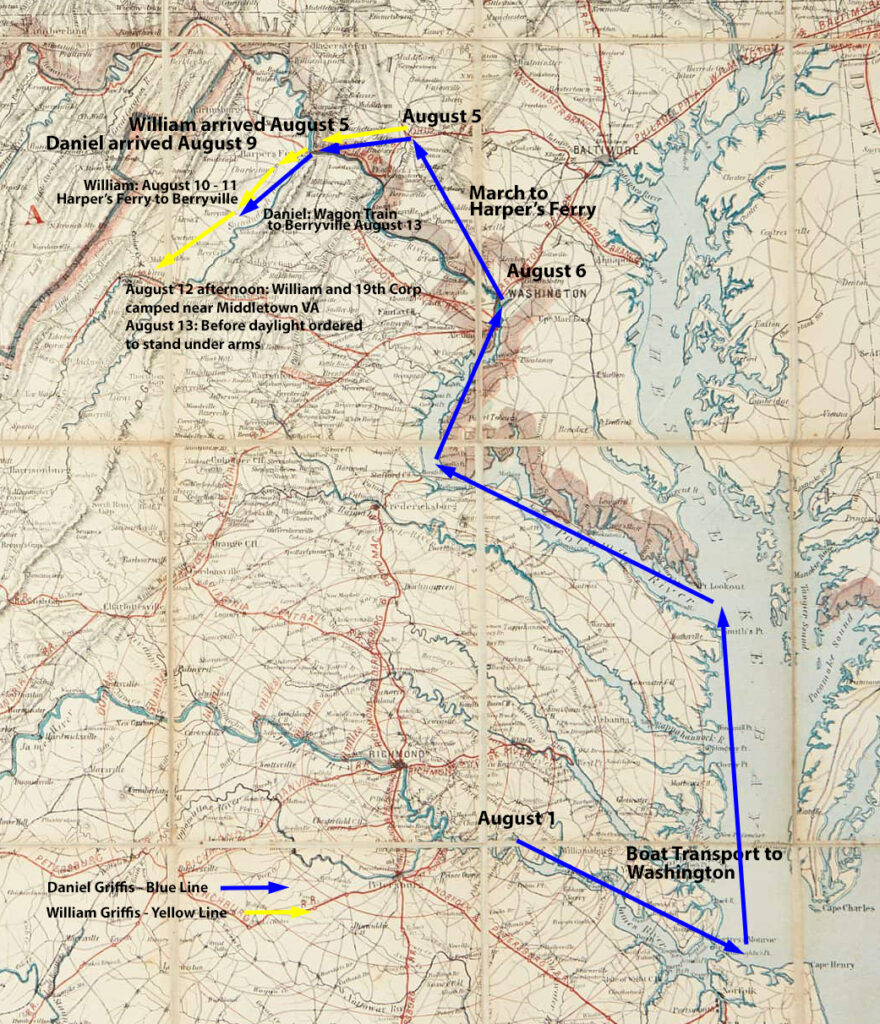

In early August, 1864, Grant directed the consolidation of Federal forces in the Maryland, West Virginia, and northern Virginia areas into a new Middle Military Division and placed General Philip H. Sheridan in command. The 6th and 19th Corps (Daniel’s brother William Griffis was a soldier in the 19th), were returned to the Valley as part of this force. Units previously assigned to the area were consolidated into the 8th Corps. The local cavalry division was joined by two horse divisions from the Army of the Potomac to create a cavalry corps for this powerful new force. The First New York Dragoons were part of this initiative. Sheridan was instructed by Grant to end Confederate military power in the Valley and to destroy the Valley as an economic asset. [5]

Sheridan started preparations for his campaign at Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia. Harper’s Ferry was a key supply depot for the Union Army. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers with access to boats, having rail access with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and access to the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, Harper’s Ferry was strategically important to both sides during the war. The town changed hands eight times but remained under control of the Union for 80 percent of the war. [6]

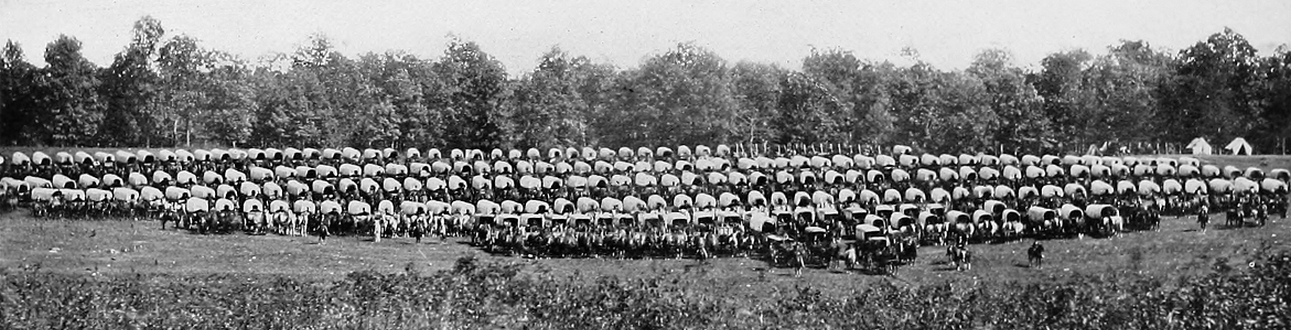

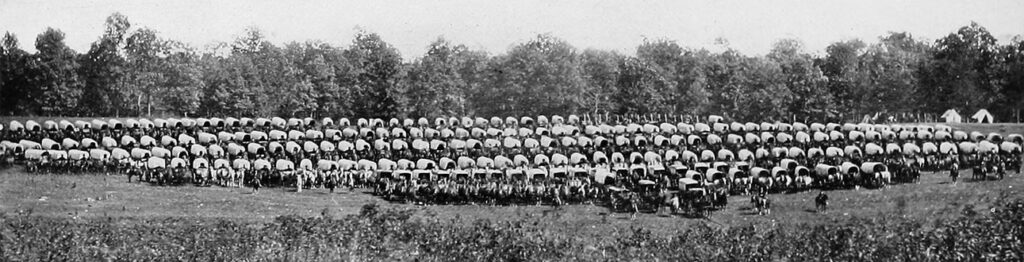

Given the size of the army, the amount and range of supplies required to support the troops and the number of mules required for the wagons, the brigade wagon trains were massive. The photograph below and featured at the top of this story illustrates the size of a wagon train required to follow a military corps or brigade.

Supply trains of the great armies numbered thousands of six-mule teams and during the march the wagon train would stretch for several miles.

Filled with critical provisions such as food, clothing, medicine, munitions, equipment required for maintenance and spare parts, horse saddles and other paraphernalia, compressed bales of hay and oats for horses and mules, the supply train was a necessary lifeline of the army. While the railroad was also vital in the rapid movement of troops and provisions, the trains were limited by the scarce routes of the era. Although trains would often move much needed ammunition rapidly near the front, it was the mule and horse that often hauled it to troops.

The mobility of the army depended on the carrying capacity of its wagons. Toward the end of the war, the Army of the Potomac carried ten days of rations and ordnance stores for an entire campaign. The number of wagons per regiment varied depending on circumstances and military campaigns and there are a variety of Union military General Orders that qualified the use and deployment of wagons. [7]

Supply trains left for the “front” regularly, always under threat of attack. To protect wagon trains from guerrilla Confederate cavalry, it was standard Union military operational procedure to park wagon trains on the outskirts where troops were situated, protected in the flank and guarded behind the Union lines. Supply trains of the great armies numbered thousands of six-mule teams and during the march the wagon train would stretch for several miles. [8]

In addition to standardized security procedures for managing wagon trains, the Union Army initiated the use of “100 day men” to guard wagon trains. Hundred Day Men was the nickname applied to a series of volunteer regiments raised in 1864 for 100-day service in the Union Army during the height of the American Civil War. These short-term, lightly trained troops freed veteran units from routine duty to allow them to go to the front lines for combat purposes.

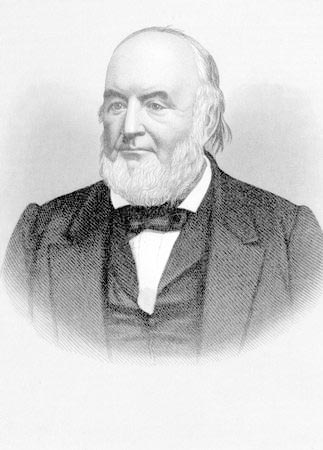

As the Civil War entered its fourth year, troops were increasingly difficult to raise in both the North and the South. In the North, substantial bounties were offered to induce enlistment and the unpopular draft and the substitute system was used to meet quotas. The governor of Ohio, John Brough proposed to enlist the state militia into federal service for a period of 100 days to provide short-term troops that would serve as guards, laborers, and rear echelon soldiers to free more veteran units for combat duty. Brough expanded the idea and enlisted the support of the governors of Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Wisconsin, and New Jersey to raise 100,000 men to offer the Lincoln Administration. The governors submitted their suggestion to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who placed the proposal before President Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln immediately approved the plan. [9]

Two Ohio regiments, attached to General Kenley’s Independent Brigade, part of the 8th Corps, were responsible for protecting the reserve brigade wagon train that Daniel Griffis was a wagon master. The 144th and 149th Ohio Infantry Regiments were guards for the wagon train. [10]

Reproduction of an engraved copper portrait of Ohio Governor John Brough. He was elected in 1864 during the Civil War and pledged to continue military support for the Union cause. Brough died in 1865 and did not complete his two year term. [11]

“The transportation of supplies is limited by the ability of the Government to provide (wagon ) trains, and by the ability of the army to protect them; for large trains create large drafts on the troops for teamsters, pioneers, guards, etc. An army train, upon the most limited allowance compatible with freedom of operations for a few days, away from the depots, is an immense affair. Under the existing allowance in the Army of the Potomac, a corps of thirty thousand infantry has about seven hundred wagons, drawn by four thousand two hundred mules; the horses of the officers and of the artillery will bring the total of animals to be provided for up to about seven thousand. On the march it is calculated that each wagon will occupy eighty feet – in bad roads even more; consequently a train of seven hundred wagons will cover fifty-six hundred feet of road – or over ten miles; the ambulances of a corps will occupy about a mile, and the batteries about three miles; thirty thousand troops need six miles to march in, if they form but one column; the total length of the marching column of a corps is therefore twenty miles, even without including the cattle herds and trains of bridge material.” [12]

The Berryville Wagon Raid – August 13, 1864

As indicated in a prior story (A Tale of Two Brothers – Part Three) on August 7th, 1864 Sheridan arrived and took command of the army. On August 10th at 5 in the morning, Sheridan started his entire army from its secure camp on Bolivar Heights near Harper’s Ferry for the Shenandoah Valley Campaign.

At 9 in the morning they reached Charlestown. Beyond the town, the 8th Corps was sent to the left of the pike, the 6th Corps to the right and the 19th Corps (William Griffis’ Corps) in the center of the road. All moved in parallel columns. The wagon train, pursuant to Army Orders and procedures probably delayed their start and were probably not immediately behind the 6th, 8th and 19th army Corps, guarded by 100 day men. After an 18 mile march the troops camped near Berryville at 5 pm. The wagon train may have been a few miles behind.

On August 11th William and his comrades marched left of the road in open country guided by compass and camped near Newtown, Virginia. They marched by the flank, slowly feeling their way southward. They could hear cannon towards the front, signifying that the calvary was engaged with the Confederates.

On the 12th the troops marched to the valley pike. The army moved alongside the pike in parallel columns through the adjoining fields while the advance portions of the army kept up a continual fire on the rebel rear guard. In the afternoon of August 12th the army passed through the village of Middletown, Virginia and camped in an open, level field.

As George Perkins, who was a soldier in the 149th Ohio volunteer infantry (one hundred day’s men) who provided guard duty for the wagon train, observed:

“On the 12th of August Sheridan moved up the valley, passing along the road near our camp. The General and his staff rode at the head of the column. The cavalry came next riding in columns of four, followed by the Sixth and Nineteenth Corps, the army of West Virginia and the Artillery. Our brigade was detailed to guard the wagon train. Brigadier John C. Kenley’s independent brigade consisted of the 144th and 149th Ohio, the 3d Maryland Infantry, and Alexander’s battery of Light Artillery.”

” … it took an entire day to pass our camp, the Cavalry and Infantry in column of fours, (giving) some idea may be had of the grandeur of this army.” [13]

Consistent with Army procedures and regulations, the army Corps wagon train that Daniel Griffis was assigned camped near Berryville after picking up their supplies at Harper’s Ferry. His wagon train was part of the reserve brigade wagon train. They probably prepared the night camp for rapid departure in the morning of August 13th. According to policy, they faced wagons so that they can be pulled in the direction of march without turning in a semi- circle. The day before, they removed fences and filled in ditches for a speedy morning departure.

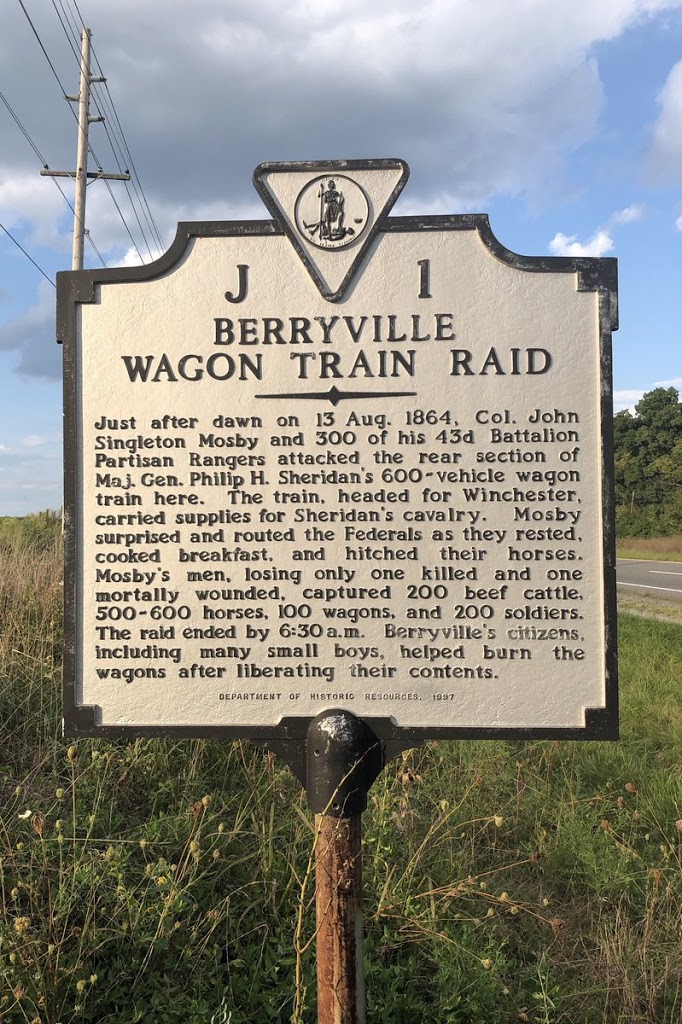

Roadside Plaque where the Berryville Wagon Train Raid occurred. Plaque is located on side of the Lord Fairfax Highway near the intersection of the Harry Byrd Highway, source: Read the Plaque

It is interesting to note the facts pertaining to the raid on the roadside plaque as compared with how the event was described in the newspaper stories of the event.

The Corps or brigade level wagon trains were organized by division. Each brigade train was guarded by ‘100 day men’, or 300 guards per division train and would prevent stragglers from joining the relative safety of the trains. [14] During the convoy on August 13th, the wagon train probably shortened the column length during breaks by forming wagons in column of twos. If a wagon had problems or a broken wheel, the train continued on and left the disabled wagon with an escort. Troops or artillery pass wagons on the left; keeping trains closed up; and trains must not be cut by other trains. The wagon trains were given a five minute rest period at the end of every hour.

Mosby’s Raiders

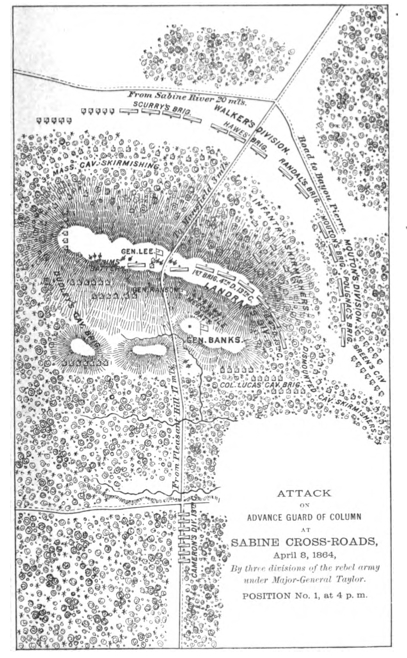

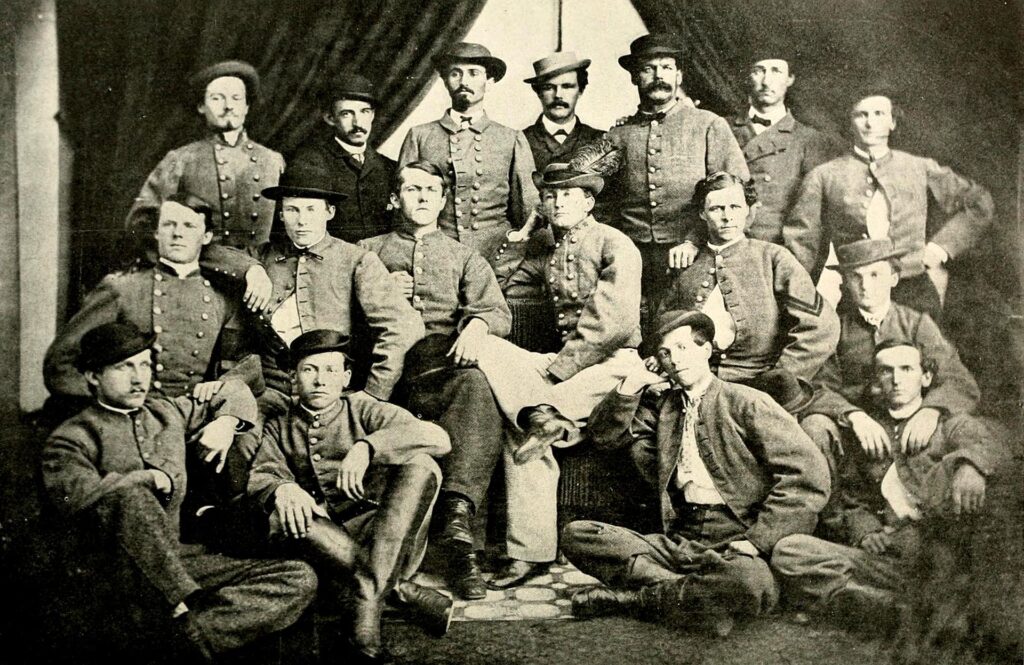

Daniel’s wagon train was in an area of northern Virginia, known as ‘Mosby’s Confederacy’. John Singleton Mosby (December 6, 1833 – May 30, 1916), also known by his nickname, the “Gray Ghost”, commanded the 43rd Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, also known as Mosby’s Rangers, Mosby’s Raiders, or Mosby’s Men. Mosby’s area of operations was Northern Virginia from the Shenandoah Valley to the west, along the Potomac River to Alexandria to the east, bounded on the south by the Rappahannock River, with most of his operations centered in or near Fauquier and Loudoun counties. [15]

Noted for their lightning strike raids on Union targets and their ability to consistently elude pursuit, Mosby’s Rangers disrupted Union communications and supply lines throughout the war. The calvary unit’s typical strategy involved executing small raids with 20 to 80 calvary behind Union lines. They would enter the area undetected, quickly execute their mission, and then rapidly withdraw, dispersing their bounty to Confederate troops and blend in among local southern sympathizers. The calvary members typically had more than one horse on their raids. One horse would be replaced by another to maintain speed and allude capture. [16]

Top row (Left to Right): Lee Herverson, Ben Palmer, John Puryear, Tom Booker, Norman Randolph, Frank Raham. Second row: Robert Blanks Parrott, John Troop, John W. Munson, John S. Mosby, Newell, Neely, Quarles. Third row: Walter Gosden, Harry T. Sinnott, Butler, Gentry Source: Francis Trevelyn Mill, Editor in Chief & Robert Lanier Managing Editor, The Photographic History of The Civil War in Ten Volumes: Volume Four, The Cavalry. The Review of Reviews Co., New York. 1911. p. 171.

There are different accounts of what happened on August 13th, 1864. James Riley Bowen in his regimental history of the First New York Dragoons, stated that:

“Early in the morning of August 13, the entire reserve brigade wagon train was captured by the guerrilla Mosby. It had been moved out from Harper’s Ferry, and was in park near Berryville. The train was guarded mostly by one hundred day men, who threw down their arms and ran like sheep at the first sight of the coming guerrillas. We lost all our regimental records, besides much valuable private property. Mosby destroyed seventy-five wagons, and ran off two hundred prisoners, with a loss of but two men, killed by Than Marr and another Dragoon, who stood their ground and were captured. Than had $100, which he quickly hid beneath a large stone. Escaping on the road to Richmond, he returned and secured his money. In this affair, we lost two week’s mail.” [17]

George Perkins, who was assigned to guarding the wagon train, recalled the Berryville raid in his written experiences with the 149th Ohio volunteer infantry:

“Our brigade (the 149th Ohio Volunteer infantry) was distributed through the length of the train, each company in charge of thirty wagons. … Soon after dark, in spite of warning from the officers, the men began to straggle, dropping out of ranks; some were getting into wagons, others climbing the fences and sleeping in the fields, expecting to overtake their command by morning. My chum, James Ghormley, and myself, after marching until eleven o’clock at night, concluded that we were too tired to go any longer that night, and that a good sleep was just what we needed. We were within two miles of Berryville when this notion entered our heads. When we awoke daylight was just visible, and we hurried on to overtake our Regiment, expecting to boil coffee at the first fire we came to. We walked on and soon came to where the train had ”parked,” that is, had encamped for the night, and were just pulling out. It has been said that this stop was made without orders from our officers, but that the rebels, riding along during the night dressed in our uniform, saying they were aids, had given these orders, their object being to cut off the train and attack it for plunder.

“Our little squad soon came to where a company of the 144th Ohio (the other division of 100 days men that were charged with guarding the wagon train) were cooking breakfast. We asked permission to boil coffee at their fire. We stacked arms, and our coffee had just come to a boil when “bang! bang!” came two artillery shots at us, scattering the limbs of the trees above our heads. These shots were followed by a volley from a clump of woods. Then they charged, yelling as they came.

“…We grasped our guns, leveled them over the stone wall, gave them one volley, when the Captain in command gave the order to scatter and save ourselves. Well, we ran.” [18]

In response to the firing behind stone walls, Confederate Raider Munson recalled:

“Before the attack he (Mosby) expressed the hope and the belief that his men wold give (General) Kenly the worse whipping any of Sheridan’s men ever got, and it delighted him to see the work progressing so satisfactorily. At several points along the line Kenly’s men made stands behind stone fences, and poured volleys into us but, when charged, they invariably retreated from their positions.” [19]

From the Confederate perspective, John W. Munson, one of Mosby’s Raider’s, provided an in depth perspective of the Berryville encounter, 42 years (1906) after the event in a personal history of the Mosby Raiders. Colonel Mosby took 300 men from Upperville, Virginia, the largest he ever had for a single engagement, over into the valley. They went into camp around midnight near Berryville. Scouts were sent out and they returned with information about a Union wagon train moving down the pike. Mosby, Munson and a few more of the calvary took off to learn more about the wagon train.

“We struck out in the direction whence, in the stillness of the night, came the rumbling echoes of the heavily laden wagons. In olden times, when the stages were run up and down the valley turnpike, it was said that the rumbling of the coach on the hard, rocky road could be heard for miles a’ still night and, on the quiet August night of which I am writing, we heard the wagon train long before we came in sight of it, which we did in an hour after Russell (John Russell, a prominent valley scout of Mosby’s) reported to the Colonel.” [20]

Mosby and his scouting party split up and individually rode up to the wagon train and blended in. “We rode among the drivers and guards, looking the stock over and chatting with the men in a friendly way.” It was too dark for the Union guards and wagon drivers to distinguish Mosby’s men. Through their friendly chats, Munson indicated in his history of the Raiders that Mosby’s men determined that there were 150 wagons in the train, with more than 1,000 head of horses, mules and cattle guarded by 2,000 men from two Ohio regiments and one Maryland regiment, with calvary dispersed along the entire line.

At a certain point in the night, confident of their knowledge of the wagon train, Mosby withdrew his men from the line, one by one, to avoid detection. He ordered Munsen to go back to camp and wake the troops up to meet Mosby on the turnpike further down the road. At day break the whole command of three hundred men along with two pieces of light artillery (12 pound cannons) met Mosby. They set up the cannon on top of a small hill and waited for the train to appear. Mason indicated that Mosby’s main concern was keeping the three hundred calvary in line to avoid charging before he was ready. ‘Three hundred over two thousand meant being careful’.

Mosby ordered the artillery to fire on the wagon train, two shots exploded in the train.

“The whole train stopped and writhed in its centre as if a wound had been opened its vitals. … What on earth ever possessed them I am unable even to this date to say. Two thousand infantry and a force of calvary all at sea, but, as with one mind, and without making the least concerted resistance, the train began to retreat. Then we rushed them, the whole Command charging from the slope, not in columns, but spread out all over creation, each man doing his best to outsell his comrade and emptying revolvers, when we got among them, right and left.

“The whole wagon train was thrown into panic. Teamsters wheeled their horses and mules into the road and, plying their black-snake whips, sent the animals galloping madly down the pike, crashing into other teams which, in turn, ran away. Infantry stampeded in every direction. Calvary, uncertain from which point the attack came, bolted backward and forward without any definite plan, Wounded animals all along the train were neighing and braying, adding to the confusion. Pistols and rifles were cracking singly and in volleys.” [21]

The conflict was strung out over a mile and a half which was the length of the wagon train. The effects of the surprise attack and resulting pandemonium had union troops and guards fleeing. Mosby gave orders to unhitch all teams that did not run away and burn the wagons. By eight in the morning the fight was over.

Similar to other accounts of this raid, Munson’s account may not be entirely valid and given the passage of time between the actual event and the publication of his book in 1906. The recollection of events and facts may have changed. Maryland did not have 100 day soldiers but Ohio had 42 regiments of 100 day men regiments. [22] Based on a newspaper article on the raid, the escort of the train was made up of 100 day’s men of the 144th and 149th Ohio regiments, whose time in service was to expire the very next day after the raid! [23]

One of the more reliable news stories reported by the Washington City National Republican indicated that the reserve brigade train had approximately 70 wagons. According to their news source, the 6th Corps left their wagon trains behind when they were transported from Louisiana to Washington City after the Red River Campaign and were furnished new wagons for the Shenandoah Campaign. Purportedly the original wagons caught up with the regiment in Washington and a quartermaster under ‘misperceived’ orders put together the reserve brigade wagon train and attempted to follow the division to the front.

Among the troops that were part of the reserve brigade wagon train was a Major Sawyer, paymaster, who was ordered to pay off Colonel Devine’s brigade of calvary. He purportedly had $100,000 in greenbacks for payroll in his possession. According to the writer of the newspaper story:

“At five ‘clock, a.m. the rebels, posted in the woods on the road began firing with pistols, and the guards skedaddled, threw down their guns and vamoosed. This left the long train at the mercy of the guerrillas, and there was a good deal of scrambling.”[24]

As reported in the newspaper article and in Munson’s recollections with the Mosby’s Raiders, Major W.E. Beardsley, commanding the 6th New York Calvary, was with the wagon train and immediately ‘put himself in fighting order‘ when Mosby attacked the wagon train. He had a galloping duel with a rebel officer and two other skirmishes with Mosby’s men. He moved upon four men who were attempting to rob the Paymaster’s wagon. “As the Major’s regiment was particularly interested in the greenbacks there deposited, it may naturally be supposed that he neglected no chance for rescuing the devious deposits.” [25]

Beardsley dispersed the four guerrillas from the wagon and although the brigade mail had been captured and carried off, the greenbacks were untouched.

John Munson, one of Mosby’s men, told a different tale:

“Among the wagons burned was one containing a safe in which an army pay-master had his greenbacks, said to be over one hundred thousand dollars. We overlooked it, unfortunately, and it was recovered the next day by the enemy, as we always supposed; but there is a story afloat in the town of Berryville that a shoemaker who lived there at the time of the fight got hold of something very valuable among the wreckage of our raid and suddenly blossomed out into a man of means, marrying later into one of the best families of the valley. He never would tell what his new-found treasure was. Maybe he got the safe and greenbacks.” [26]

George Perkins also ‘recalled’ a different story about the incident with the greenbacks:

“The paymaster was shrewd; he had packed the money in a cracker box and placed it in a wagon, keeping his strong box in his own vehicle. During the fight this cracker box was tumbled down the banks of a little creek that ran through the field. I saw it lying there and after the skirmish the paymaster came back and got it.” [27]

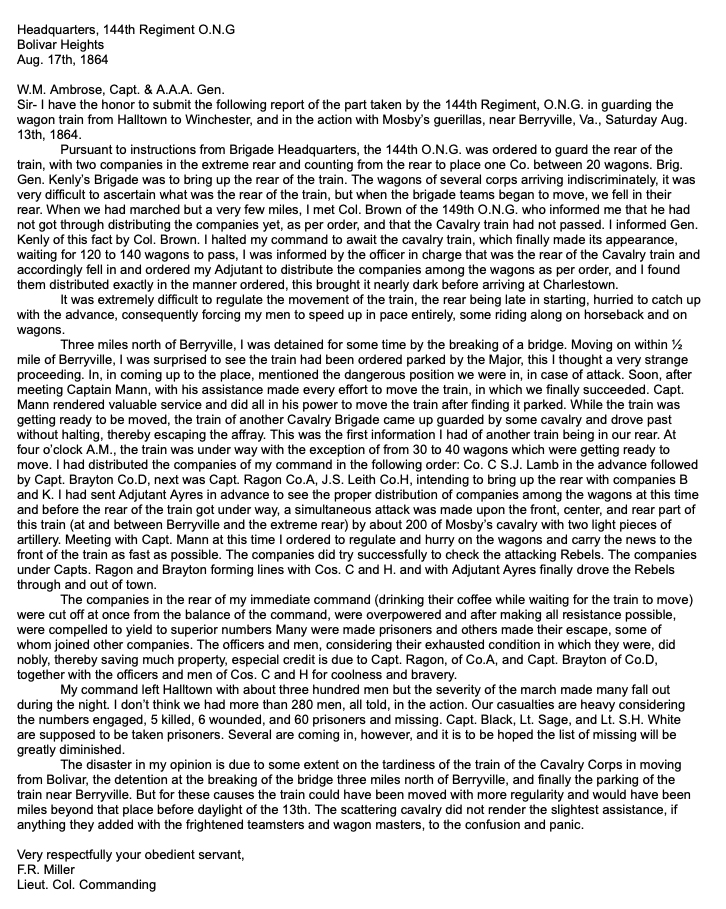

A report by Lieutenant Colonel Frederick R. Miller, officer of the 144th Ohio National Guard, which does not appear in the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (O.R.) but was published in the September 2, 1864 edition of the Upper Sandusky Wyandot Pioneer newspaper, attributed the success of the raid to some extent on the delay of the train of the Cavalry Corps in moving from Bolivar (Harper’s Ferry), the wagon training being stalled by the breaking of the bridge three miles north of Berryville, and finally the parking of the train near Berryville. [28]

Despite differing stories about the Berryville Wagon Train raid, it was nevertheless a major event. Not only did Mosby disrupt a major supply chain for Sheridan’s campaign, it captured union soldiers (one of which was Daniel Griffis), livestock, horses and mules, supplies, documents and mail, and ammunition.

What Really Happened on August 13, 1864?

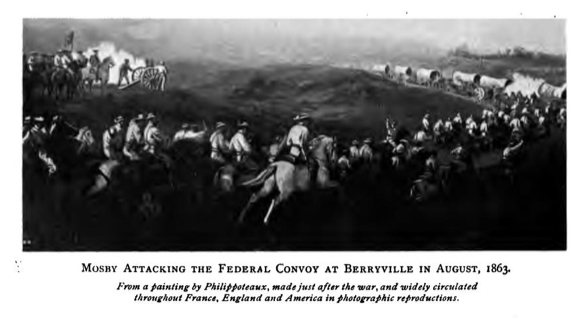

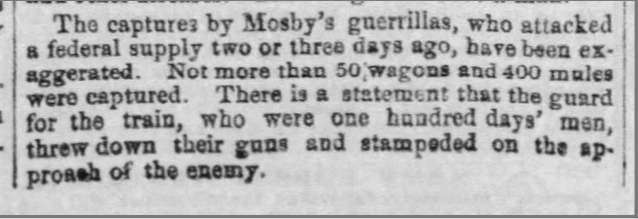

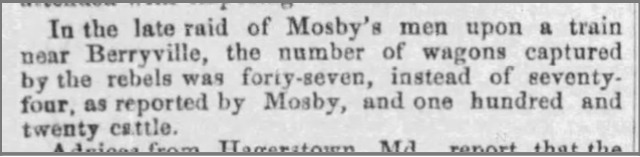

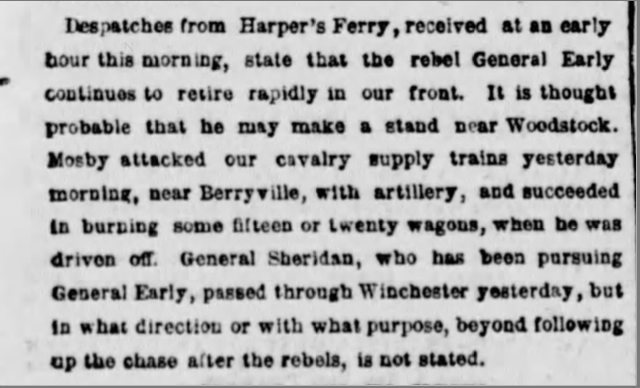

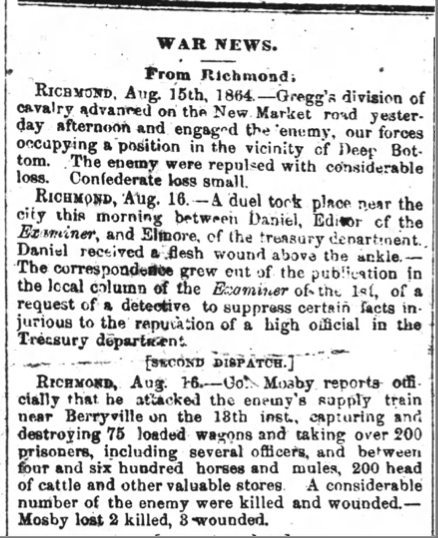

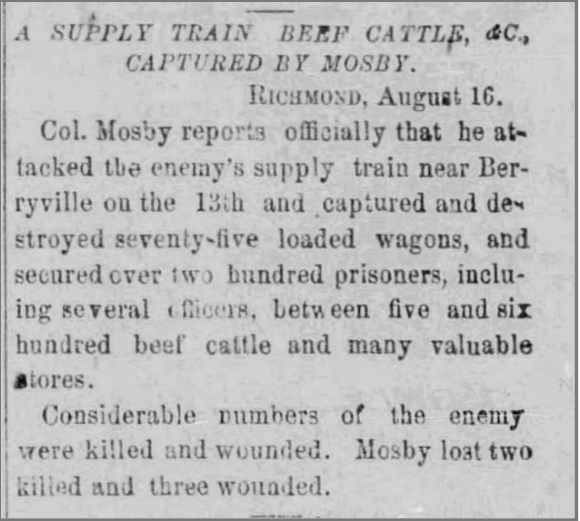

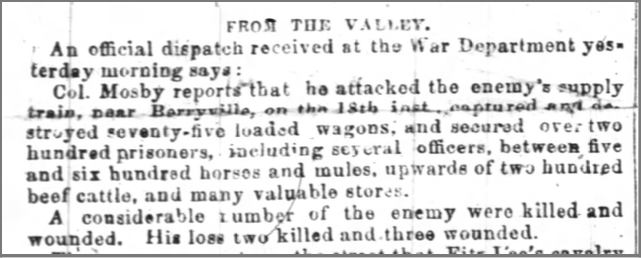

Depending on what news source a newspaper obtained their information on the raid, the facts and figures varied considerably in regard to the number of prisoners captured, the number of livestock and equine stock was confiscated, and the number of wagons burned. With few exceptions, the Union based newspapers relied on a terse telegraph message from Secretary of War Stanton who quoted General Sheridan’s comments that the result of the raid was exaggerated by Mosby.

The following provide an illustrative example of the range of differences in newspaper reporting across the Republic and the Confederacy. Blue background reflects Union oriented newspapers and grey back ground reflects Confederate oriented newspapers. This is not a representative sample of newspapers reporting the incident. Of the few articles that are referenced, the article from the National Republican (Washington City) · 22 Aug 1864, appears to have the most information about the wagon raid.

Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut) · 19 Aug 1864, Fri · Page 2:

“50 wagons and 400 mules captured“

Hartford Courant (Hartford, CT) · 23 August 23, 1864, Page 2

“47 wagons captured and 120 cattle”

New York Daily Herald (New York, New York) · 14 Aug 1864, Sun · Page 4

“15-20 wagons burned”

Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) · 17 Aug 1864, Wed · Page 1

“The story of plunder taken from me by rebels, is humbug;”

New York Daily Herald (New York, New York) · 17 Aug 1864, Wed · Page 4

“Stories about accumulated plunder untrue”

Fort Wayne Daily Gazette (Fort Wayne, Indiana) · 17 Aug 1864, Wed · Page 2

“Stories of plunder is humbug”

National Republican (Washington, District of Columbia) · 19 Aug 1864, Friday · Page 2

“losses will amount to about 50 wagons, 400 mules, 200 head of cattle, and from 150 to 170 men…”

Bangor Daily Whig and Courier (Bangor, Maine) · 19 Aug 1864, Fri · Page 1

“The attack upon the supply train proves our losses to be 50 wagons, 400 mules and 150 men. The 100 days men became panic stricken, threw down their arms, and fled like sheep.”

National Republican (Washington, District of Columbia) · 22 Aug 1864, Mon · Page 2 Part One

National Republican (Washington, District of Columbia) · 22 Aug 1864, Mon · Page 2 Part Two

“By this raid, the rebels captured forty-seven wagons, all but ten of which were burned, and one hundred and twenty head of cattle.”

News story from the Charlotte NC Democrat, 23 August, 1864, Page 2

“…captured and destroyed seventy-five loaded wagons and secured over two hundred prisoners, including several officers, between five and six hundred horses and mules, upwards of two hundred beef cattle, and many valuable stores.”

The Weekly Standard (Raleigh, NC) · 24 Aug 1864, Wed · Page 1

“…capturing and destroying 75 loaded wagons and taking over 200 prisoners, including several officers, and between four and six hundred horses and mules, 200 head of cattle and other valuable stores.”

The Daily Selma Reporter (Selma, Alabama) · 17 Aug 1864, Wed · Page 2

“…capturing and destroying 75 loaded wagons and taking over 200 prisoners, including several officers, and between five and dsix hundred beef cattle and many valuable stores.”

The Daily Conservative (Raleigh, North Carolina) · 20 Aug 1864, Sat · Page 1

“…captured and destroyed seventy-five loaded wagons and secured over 200 prisoner, including several officers, between five and six hundred horses and mules, upwards of 200 head of cattle and other valuable stores.”

From Berryville to Richmond: A long Journey for the Prisoners

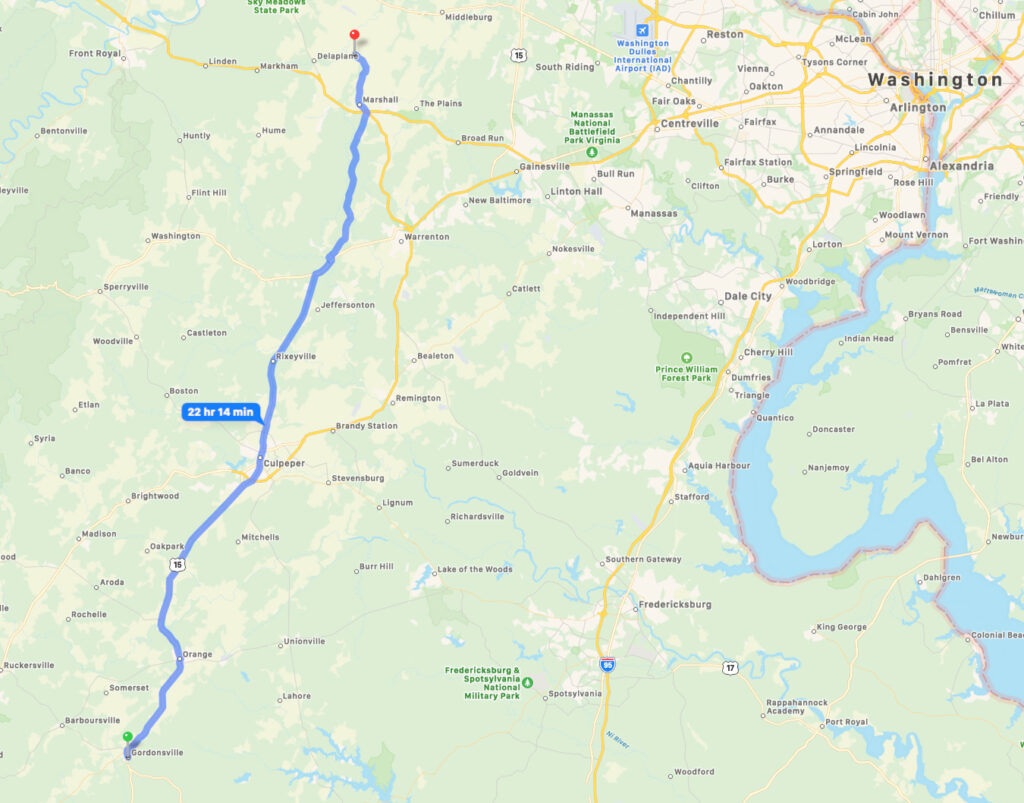

After the raid, Mosby’s attention turned to the immediate needs of removing “three hundred prisoners, nearly nine hundred head of captured stock and other spoils out of Sheridan’s country“. Their decision was to take the prisoners, the animal stock and booty to Rectortown, Virginia which was twenty-five miles south and over the mountain ridge in Fauquier county. Mosby ordered his men to unhitch all the teams that had not run away and to set fire to the wagons. They fastened loose harnesses on the animals and starting hoarding them into one drove down the pike towards the Shenandoah River. Some of the Raiders decked themselves out with officer uniforms found in the baggage of the wagons. From one of the wagons, some of the raiders found musical instruments and “the leaders of the mounted vanguard made the morning hideous with attempts to play plantation melodies on tuneless fiddles.” [29]

They crossed the Shenandoah River and began their ascent of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

“Down the turnpike into the rushing Shenandoah, regardless of ford or pass, dashed the whole cavalcade; some swimming, some wading, others finding ferriage at the tail of a horse or steer.” [30]

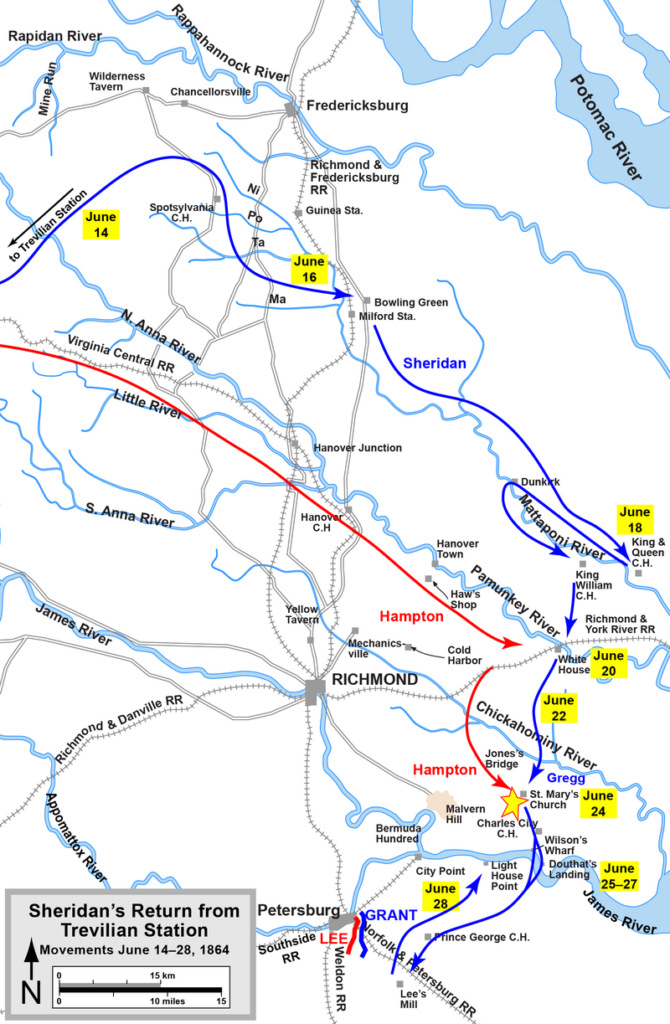

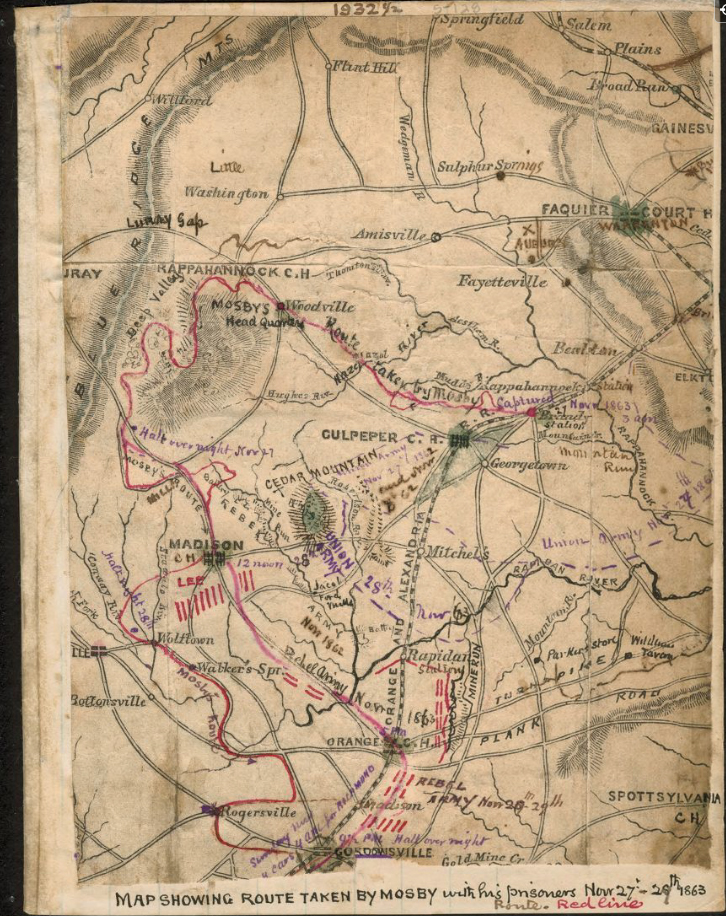

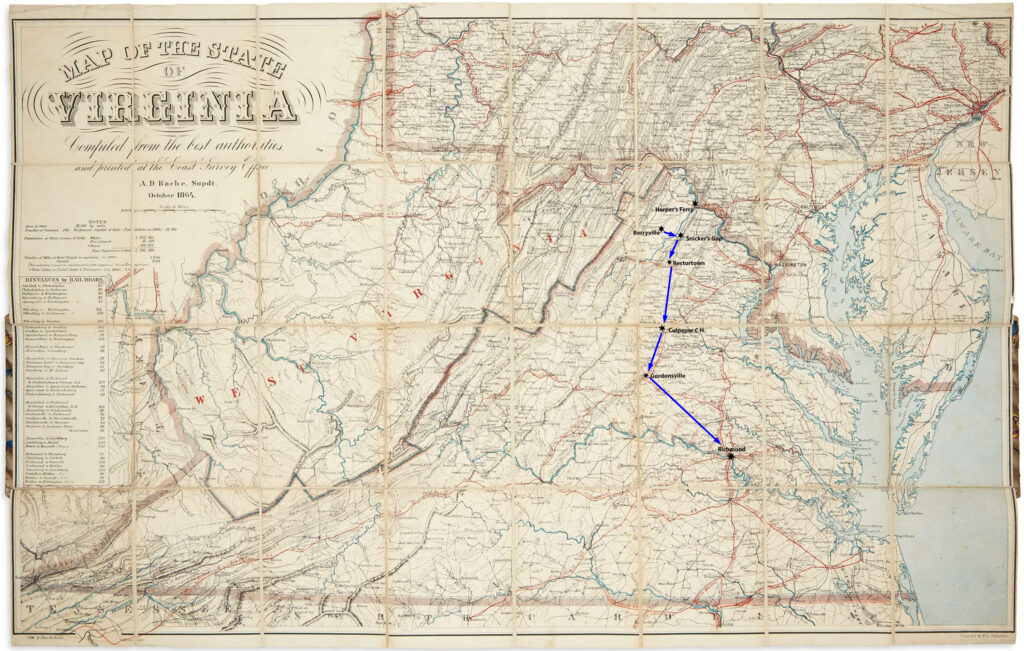

It is not known which mountain ‘gap’ pass they crossed. It could have been Snicker’s Gap or Ashley’s Gap. They arrived in Rectortown at 4 p.m. in the afternoon, the same day of the raid. After dividing the horses and plunder among the Raiders, they sent the mules and the cattle to General Robert E. Lee for the use in the Army of Virginia. The animals were driven through Fauquier, Rappahannock, Culpepper and Orange counties as far south as Gordonville, Virginia. Guards were detailed to also take the prisoners to Gordonsville. [31]

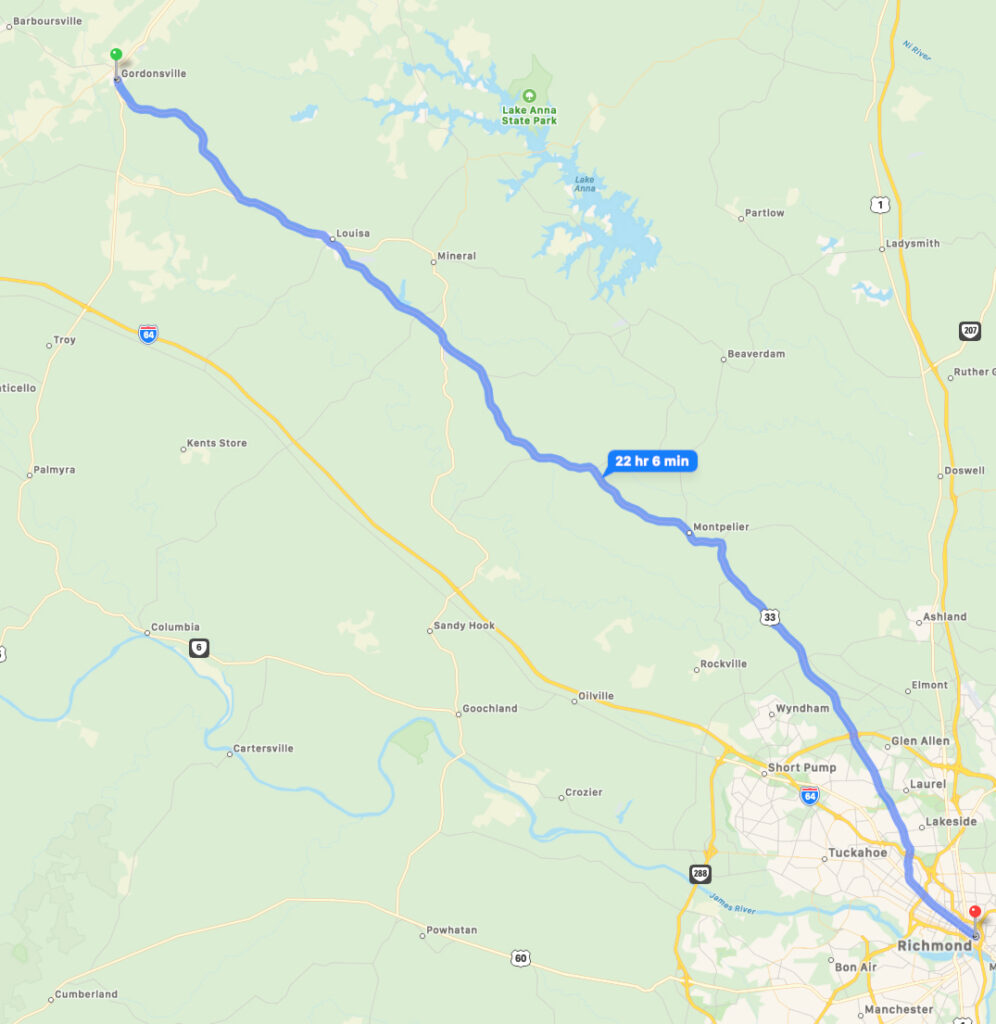

The trek from Rectortown to Gordonsville is 64 miles and would take approximately 22 and a quarter hours to walk.

Among the Union prisoners, including Daniel Griffis, was William McCommon, a member of Company “A” of the 149th Ohio Volunteer Infantry “100 day men” troops. McCommon wrote about his experiences of being captured during the Berryville Wagon Raid and his subsequent prison life in a letter. [32] While it is not entirely certain that his experiences are identical with Daniel Griffis’ experiences, it is highly likely that his path from Berryville to Richmond, Virgina and then to Salisbury Prison, North Carolina were similar if not identical to Daniel Griffis.

McCommon indicated they crossed the Shenandoah River after their immediate capture and marched on the first day for thirty miles, probably to Rectortown, Virginia. It appeared that the guards ordered many of the prisoners to ride the mules that were also captured. The next day’s ride took them to Culpepper Court House, Virginia. On the map above, that is approximately half way to Gordonsville, Virginia, the location mentioned in Munson’s memoir.

However, at the end of the third day McCommon indicated that they reached Lynchburg, Virginia where they were placed in an old tobacco warehouse. He indicated that there were three hundred prisoners in the warehouse when they arrived. The distance between Gordonsville, Virginia and Lynchburg is 87 miles and would take approximately 30 hours to walk. If the prisoners were escorted to Lynchburg, then McCommon’s story is factually incorrect since it is unlikely that they marched 87 miles in one day on their third day of their forced movement. It is conceivable that they marched to Gordonsville, which was a day’s march away) and were placed in an old tobacco warehouse in Gordonsville.

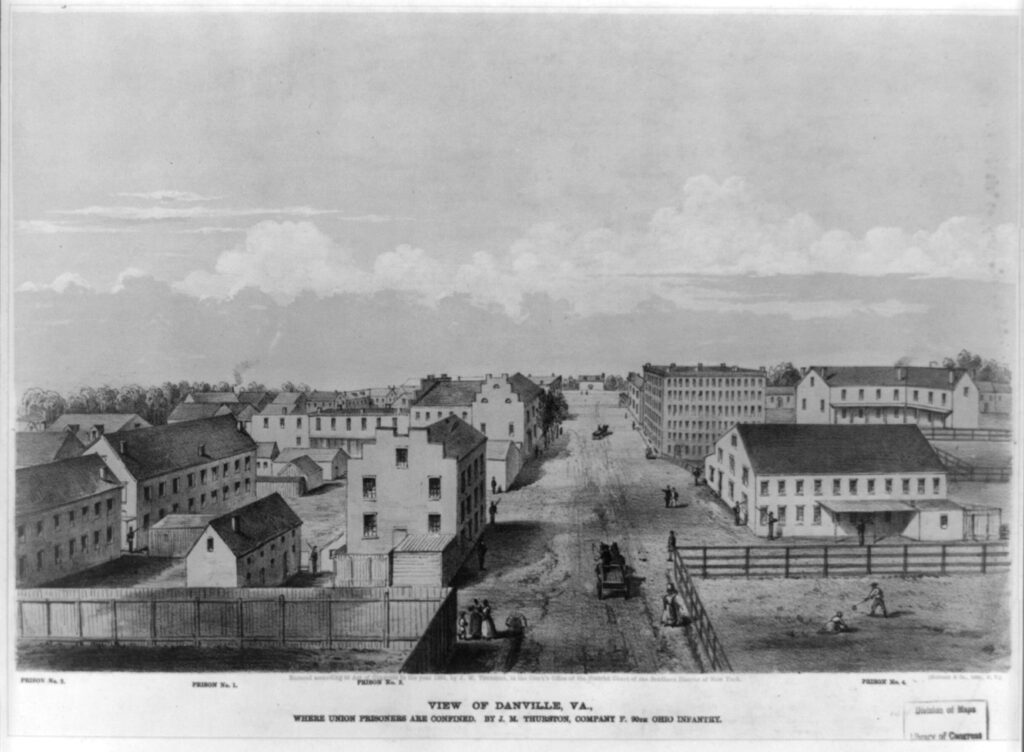

McCommon’s reference to Lynchburg and tobacco warehouses suggest that the prisoners were incarcerated at Danville Prison. During the Civil War, six Danville, Virginia tobacco warehouses were converted to use as prisons for captured Union soldiers. The brick or wooden structures were stripped of all furnishings, including chairs and lamps. During the fifteen months, between December 1863 and February 1865, Danville housed Federal prisoners. The prisoners faced brutally cold weather in the winter and sweltering heat in the summer.

“We were quartered on the dirty floor, covered with tobacco dust. You could hear the men sneeze in all languages. Our fare was still one loaf of bread for two men. “ [34]

While McCommon’s writing suggests that the soldiers captured in the Berryville Wagon Raid were marched as far south as the Danville Prison in Lynchburg, I am led to believe that the prisoners were actually incarcerated in Gordonsville as Munson indicated in his book.

The likelihood that the prisoners were brought to Gordonsville is also substantiated by the past practices of Mosby’s Raiders in managing prisoners. The Raiders brought prisoners from their raids to Gordonsville in the past.

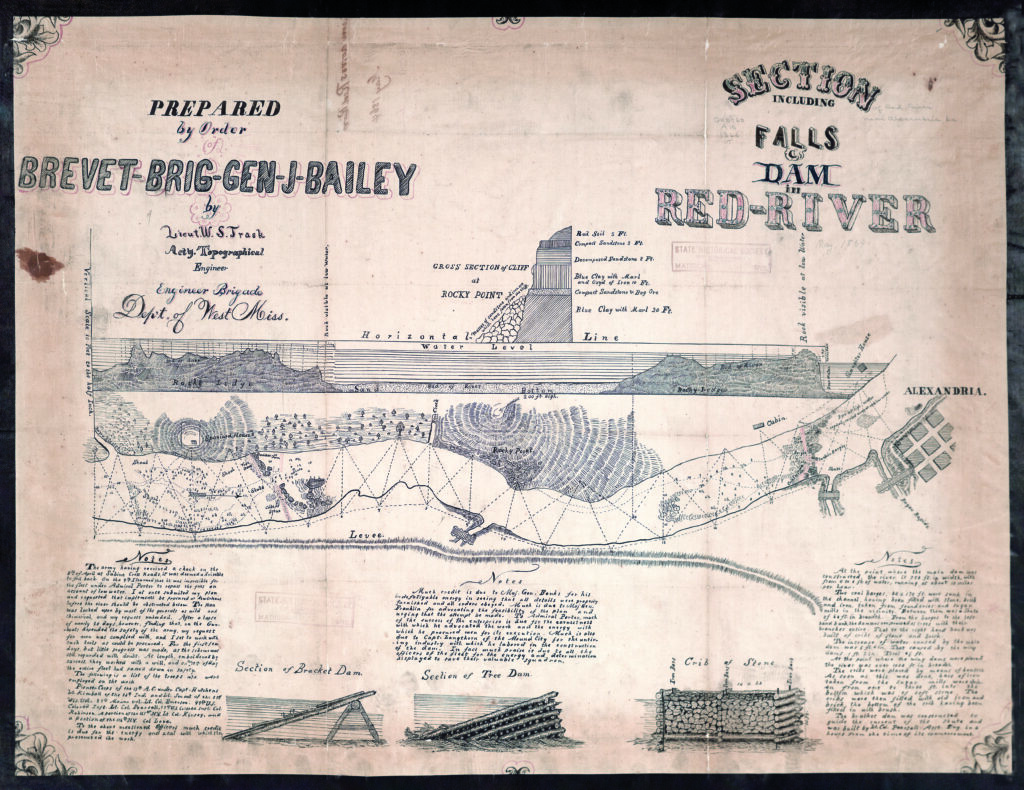

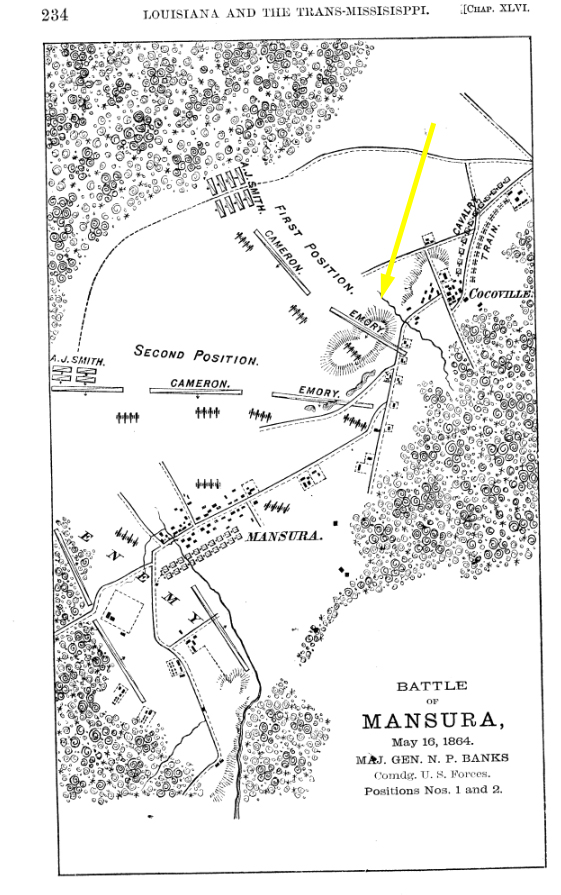

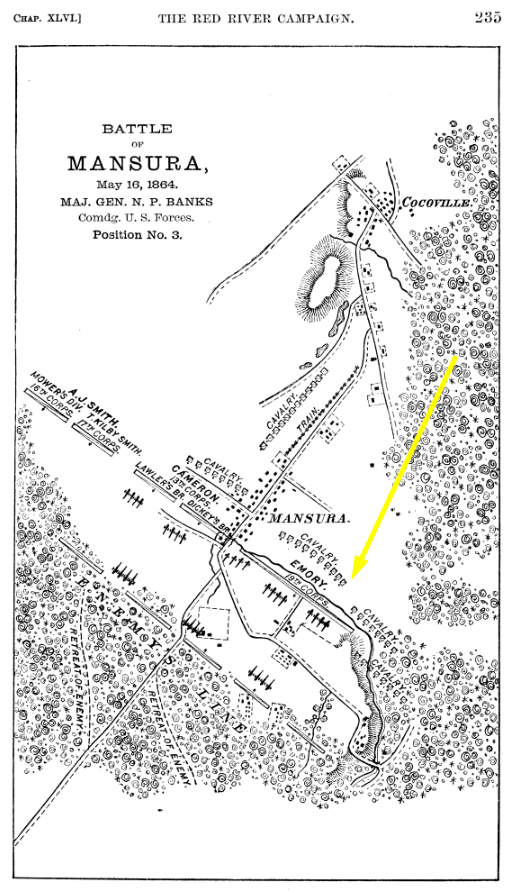

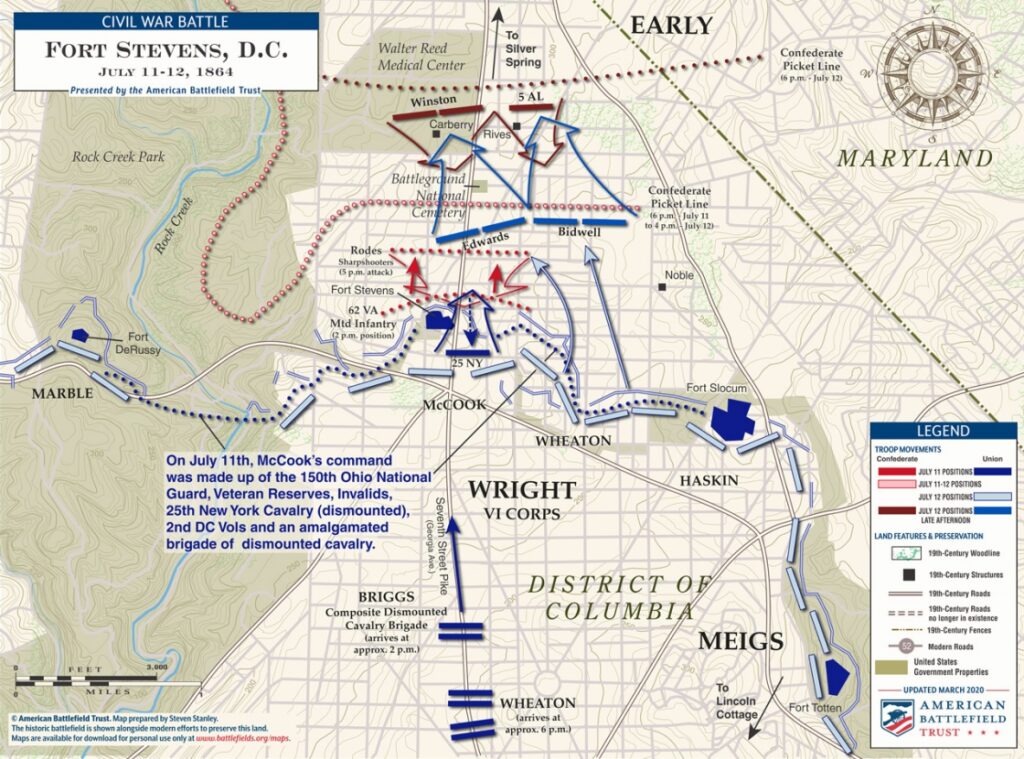

In this detailed map (above) from an unidentified printed map, Union soldier Robert Sneden traced the circuitous route he and other prisoners, captured by Mosby’s Guerillas during the Mine Run Campaign, followed from near Rappahannock Station, Virgina, to Woodville, down the Blue Ridge Valley, through Madison Court House and on to Gordonsville. Sneden has annotated the map with the names and locations of many of the small communities through which he passed.

Gordonsville, Virgina was a critical crossroads in the Civil War, as key supply lines funneled through the town by rail and road. Gordonsville also was home to the Exchange Hotel Civil War Receiving Hospital, treating more than 23,000 sick and wounded between June 1, 1863 and May 5, 1864. [36]

The Confederates kept the prisoners in Gordonsville (or Danville) for four weeks and then moved them to Richmond, Virgina. It is not known if they were transported via rail or marched to Richmond. If they marched, it would have taken them approximately 22 hours.

They remained in Richmond, Virginia for one night and then the prisoners were moved across the river to Belle Isle Prison.

During the Civil War more than 400,000 soldiers and thousands of civilians were imprisoned and about 56,000 died in captivity. When someone was in captivity, timing of being captured mattered. Union prisoners captured before July 1863 died at a rate of 4 percent and those captured after that month died at a rate of 27 percent. [37]

Lacking means for managing large numbers of captured troops early in the war, both sides relied on the traditional European system of parole and exchange of prisoners. A prisoner who was on parole promised not to fight again until his name was “exchanged” for a similar man on the other side. Then both of them could rejoin their units. While awaiting exchange, prisoners were briefly confined to permanent camps. The exchange system broke down in mid 1863 when, after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Lincoln, the Confederacy refused to treat captured black prisoners as equal to white prisoners. The prison populations on both sides then soared. [38]

Captives moved like flotsam from capture to prison and then often from one type of prison to another. [39] For example, when the Confederates placed Hiram Eddy, a captured regimental chaplain in an abandoned tobacco factory in Richmond on July 28, 1861, it was just the start of his journey. He spent three nights in September on a prison train to Charleston where he was moved back and forth between the city jail and the Castle Pickney prison. Then on January 1, 1862, he was transported to Columbia, South Carolina and remained there for two months before returning to the original tobacco factory and then Libby Prison in Richmond. With the union army moving up the peninsula close to Richmond, he was moved to the Salisbury Prison, North Carolina. After a year, three states, six prisons and 1,400 miles, in July 1862, he returned to the nation’s capital. [40]

Richmond Prisons and Belle Isle Prison

Throughout the Civil War there were 25 locations in Richmond, Virginia that housed Civil War prisoners. [41] As the capital of the Confederacy and a major rail hub, Richmond was a center of activity during the war, including the management and transportation of prisoners. Numerous prisons were established in and around the city to accommodate the large influx of Union prisoners from both the Eastern and Western theaters of the Civil War. Libby Prison, Castle Thunder, Castle Lightning, and Belle Isle are representative of the prisons in the Richmond area. [42]

While Libby Prison housed captured Union officers, the majority of common soldiers and noncommissioned officers were incarcerated at Belle Isle Prison. During the 18 months the prison was operating, more than 20,000 prisoners were received at various times. Estimates have the death total at nearly 1,000 men.

Belle Isle is a 54-acre island in the city of Richmond, Virginia and lies within the James River. It was a popular recreational area in the 1800’s for the citizens of the city. It was converted into a training sight for new recruits at the beginning of the Civil War. By the second summer of the war, however, Belle Isle opened as a prisoner of war camp to ease overcrowding at Libby Prison. The island prison was meant to be a temporary solution, and no structures were actually built to house prisoners. Three-foot-high earthworks enclosed a 6-acre space which was sufficient for a ‘wall’ since the surrounding rapids in the river served as a good deterrent against escape. Prisoners lived in flimsy pole tents—10 men to a tent—without adequate shelter from rain or cold. Officers and guards did have proper quarters nearby.

The site was technically able to hold 3,000 prisoners, and reached its capacity within 2 weeks after opening. In mid-July 1862, there were 5,000 prisoners on the island. The prisoner-exchange program helped reduce the prisoner count in the prison. Prisoners were processed from Belle Isle through Libby Prison until the prison was nearly vacant. By September 23, 1862, the prison was closed. However, the breakdown of the prisoner exchange made the space on Belle Isle needed once again, and the prison was reactivated in May 1863.

In January 17, 1863, the prison was re-opened then closed until May, when it was opened again. By November, the prison population reached 6,300 prisoners. When the prison was reopened in 1863, the earthworks were increased to 5 feet high with ditches running along both sides. The inside of the prison was marked off with 60 streets radiating from a central avenue. The streets were lined with tents for the prisoners, with about 14 to 15 men per tent.

Although its intended capacity was 3,000, there were only 300 prisoner tents for shelter. Prisoners outside of a tent were on their own for survival. At its peak, there were 10,000 prisoners on Belle Isle, and many prisoners suffered from lack of shelter. During the cold winter of 1863, up to fourteen people would freeze to death each night. [44]

The lack of shelter the elements were not the only threat in camp. Diseases such as dysentery, typhoid, pneumonia, and small pox raged through Richmond and the prisons. Sick inmates on Belle Isle were treated in the nearby hospital tents, with severe cases being sent to a hospital in the city. The limited and inconsistent supply of food was not sufficient to sustain the prisoners. Prisoners resorted to stealing among themselves and the prison guards. Hungry soldiers were known to steal the guards’ pets, such as chickens and dogs for food.

“It was a bleak spot, bare of trees. Some of the prisoners had tattered tents, the majority had none. It rained every day we were there and the fog was so thick you could almost cut it until about noon. We had no protection whatever from this weather, and we would walk around in the night in the rain until we fell asleep on the muddy ground. We would lie there until awakened by the intense cold, to get up and walk again. Here they fed us on wild pea soup… . the meals were never on time, as it took the cooks an hour or more to skim the maggots off the soup… . “ [45]

In February 1864, the Belle Isle prisoners were moved to Anderson prison in Georgia. On February 7, prisoners began leaving in groups of 400 men via train to Georgia.

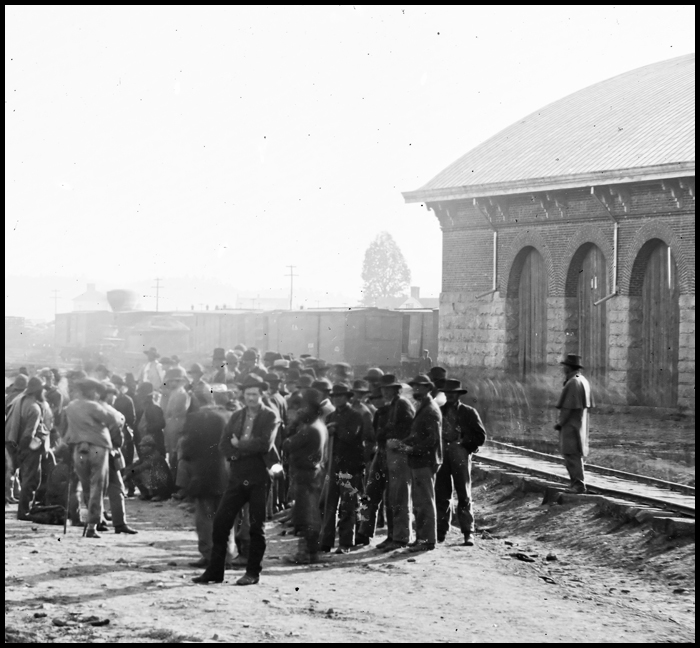

“In February, 1864, the Bureau arranged the initial shipment of Federal prisoners from Virginia to the new and soon to be notorious camp at Anderson, Georgia. The captives numbered more than twelve thousand. To minimize congestion, Sims (Frederick William Sims was Military Superintendent of Railroads of the the Confederacy) limited departures to a single daily trainload of four hundred. To discourage escape they were routed inland via Petersburg, Gaston, Charlotte, Columbia and Augusta. Though the prisoners were crammed into half-ruined boxcars which afforded little protection from the weather, the journey probably was a lesser ordeal than their subsequent confinement. … Late in June, as the enemy closed in upon Richmond and Petersburg, a particularly heavy mass was dispatched from Virginia, this time by the new Piedmont road (rail line) .” [47]

By March 1864, the last group of prisoners left Belle Isle. In June, 6,000 men were confined here but they were all transferred out to Danville Prison and Salisbury Prison by late October. Daniel Griffis was one of those ‘last wave’ of prisoners that were housed at Belle Isle and then transferred on October 9, 1864. As McCommon wrote:

“We remained for seven weeks on Belle Isle, when we were sent to Salisbury, N.C. We thought Belle Island was awful, but this place, no man can describe it, only an ex-prisoner of war.” [48]

Daniel Griffis and his fellow prisoners were among a large contingent of prisoners moved from Belle Isle to Salisbury Prison due to the fall of Atlanta and the ongoing siege of Richmond which made it easier for the Union army to potentially rescue its Union prisoners. Salisbury received some of the Richmond prisoners, and after October 1864, the majority of newly captured Union prisoners. [49]

Prisoner Transport From Richmond to Salisbury

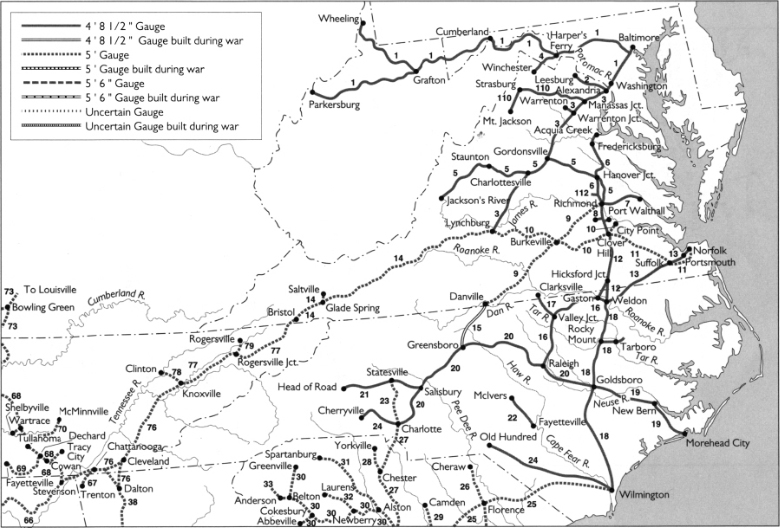

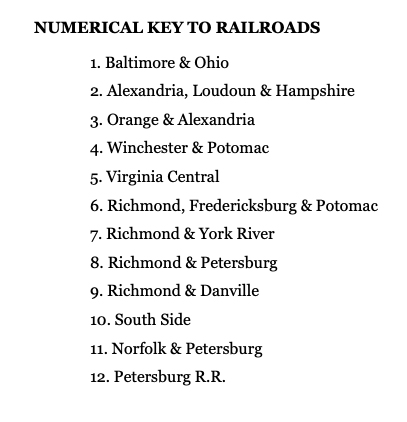

It is not known how Daniel Griffis was transported from Richmond, Virgina to Salisbury Prison in Salisbury, North Carolina. There were a number of possible rail routes, depending on the condition of railroad for various lines.

By September 1863, the Southern railroads were in bad shape. They had begun to deteriorate very soon after the outset of the war, when many of the railroad employees headed north to join the Union war efforts. Few of the 100 railroads that existed in the South prior to 1861 were more than 100 miles in length. [50] The Confederate railroad lacked sufficient rail mileage. There were gaps between key rail lines. There was a general inability to repair and maintain tracks and rolling stock . The Confederate rail system had differences of gauge between the various rail companies. The Confederacy witnessed a general failure to build badly needed new lines which ultimately hurt the infrastructure of the government and commerce. [51]

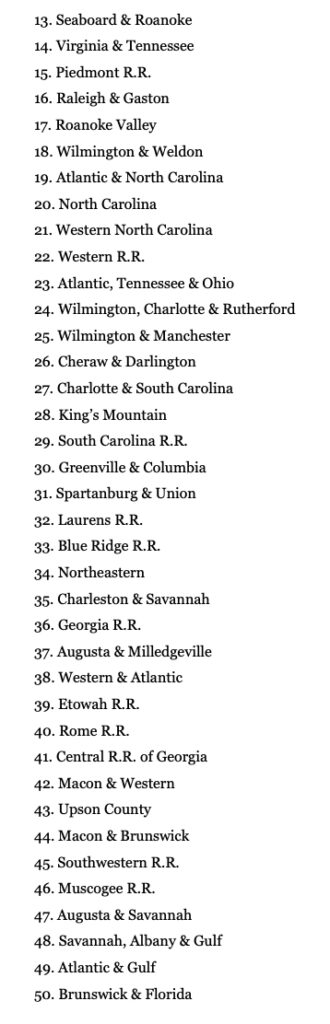

Anderson Prison in Georgia was further south than the Salisbury Prison in North Carolina. Logistically, transporting Union prisoners from Richmond to Anderson required a number of stops and transferring prisoners between rail lines that possibly had different gauge track. The “new Piedmont road” was an addition of railroad track built by the Piedmont Railroad during the war between Danville and Greensboro. On the map above it is numbered as ‘9’. This new rail connected the Richmond and Danville railroad line (number 9 on the map) with the Piedmont Railroad (number 15) and the North Carolina Railroad (number 20 on the map). All three rail lines had identical rail gauge of four feet and eight and a half inches and effectively provided a line for continuous travel or rail transportation between Richmond and Salisbury.

Chattanooga, Tennessee: Confederate prisoners at railroad depot. source unknown

Given the Union army’s push toward Richmond in October 1864 and the improved rail line to Salisbury, it is likely that Daniel Griffis, among many other Union prisoners, were transported on prisoner train lines directly from Richmond to Salisbury.

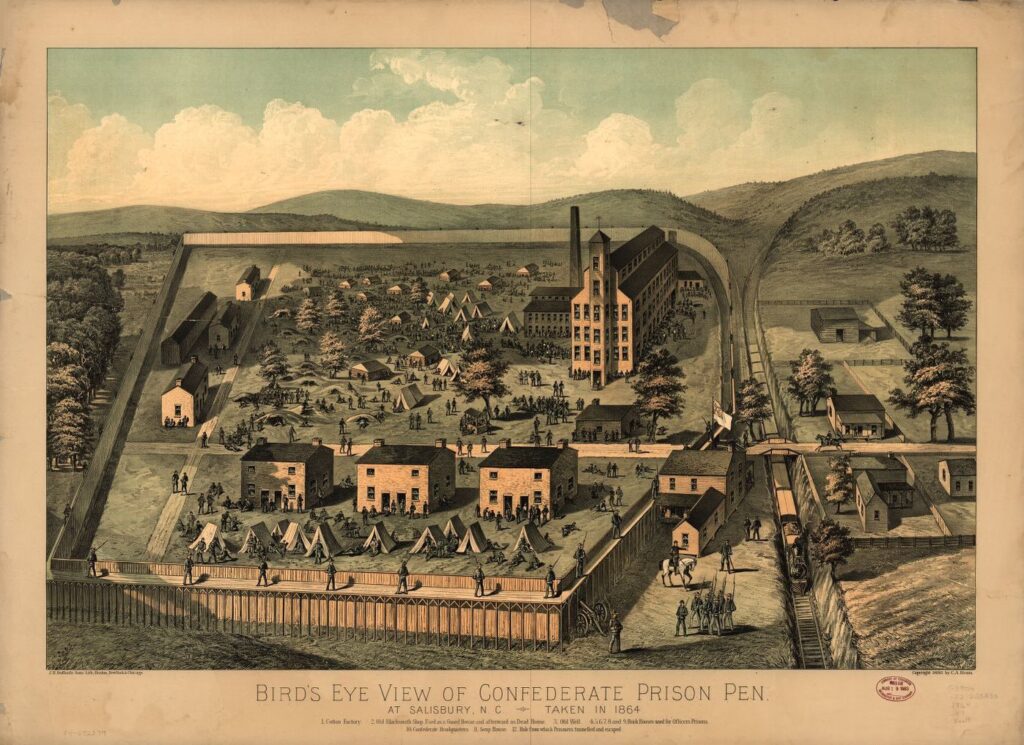

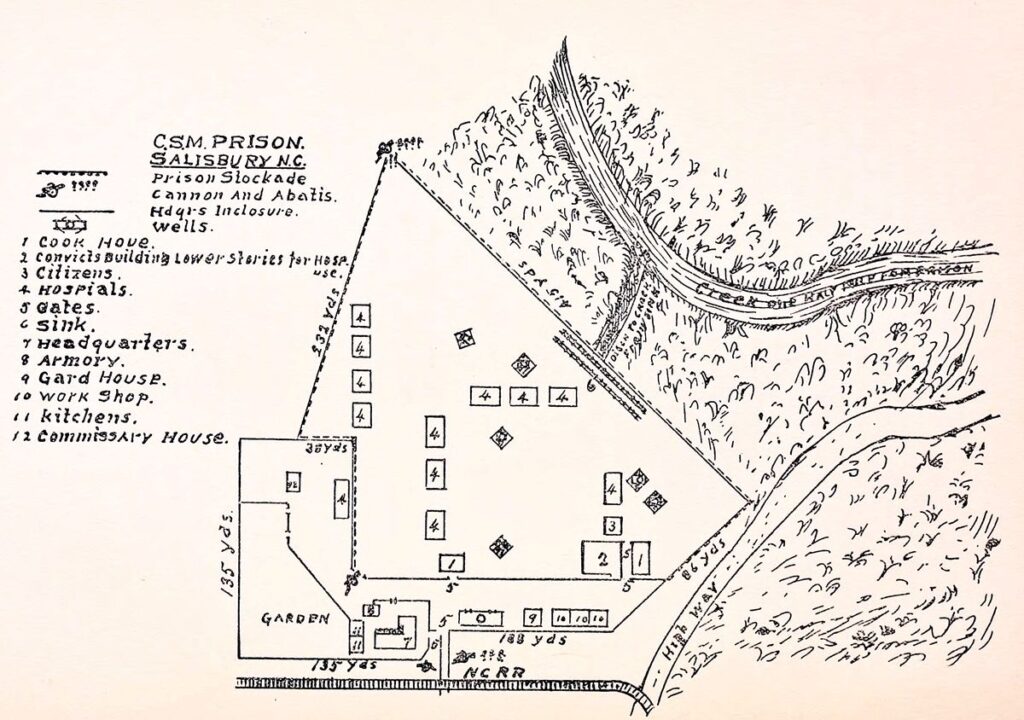

Salisbury Prison

At the beginning of the Civil War, the Confederacy was unprepared to manage Union deserters, prisoners of war and Southern deserters and dissenters. Initially these individuals were placed in jails and abandoned buildings in major urban areas. In July 1861 the Confederate government appealed to the Confederate states for a prison. North Carolina, the only state to offer a prison, suggested the site of a former cotton factory in Salisbury. [54] Its location on a rail line would facilitate prisoner movement. The main structure, a four-story brick factory, and accompanying wooden buildings would sufficiently house the anticipated two thousand inmates. [55]

On November 2, 1861, the Confederate government purchased the sixteen-acre site for $15,000. Guards were hired, and repairs and modifications to the site were made. On December 9, 1861, depending on which historical sources is referenced, between 100 to 120 Union prisoners arrived. By May 1862 Salisbury Prison held more than fourteen hundred inmates. [56]

From December 1861, when Salisbury Prison opened, through September 1864, the prison experienced a 2 percent death rate. Between October 1864 and February 1865, the rate dramatically increased to 28 percent. An estimated 4,000 prisoners died at the prison during its existence, for an overall death rate of 26 percent. Bodies were collected daily at the “dead house” and hauled in a one-horse wagon to trenches in a nearby “old cornfield.” [57]

As McCommon described one aspect of death at Salisbury:

The last time I saw Armstrong and Ghormley (fellow soldiers of his regiment) they were piled on the dead wagon that came twice a day to collect the dead. The corpses were piled in, one on top of the other like so many logs, taken out and buried in trenches. [58]

“The prison was enclosed by an 8-foot high fence with a parapet about 4-feet high running along the outside for guards to patrol along. The entrance was guarded by 2 cannon wit other cannon positioned along the portholes in the fence, with a full sweep of the inside of the compound. The prison headquarters was on the north side of the entrance gates, outside of the compound. The main building was located toward the southeast corner of the compound. The cottages were located in groups of 3 at right angles a short distance from the main building, toward the center of the compound. there was a blacksmith shop toward the front gate and later served as the “deadhouse”.” [59]

In late May 1862 prisoner exchange negotiations between the Union and Confederacy resulted in the parole of about fourteen hundred prisoners of war that were incarcerated in Salisbury. Salisbury Prison held few inmates until October 1864, the same time that Daniel Griffis was transferred from Belle Isle Prison to Salisbury Prison, when thousands of captives began arriving and when more were diving each day at the prison. As stated, timing of when one was captured and where one was incarcerated was the key for survival. Unfortunately for Daniel Griffis, he was captured and housed at Belle Isle and Salisbury Prison during the worse time for Union prisoners.

In the fall of 1864, escape from Salisbury Prison was considered almost necessary to save one’s life. At the beginning of November 1864, the prison held up to 10,000 inmates (figures vary based on source of information), the largest number at any one time and far more than the 2,500 for which it was designed. Conditions quickly deteriorated. Inmates faced overcrowding, poor sanitation, limited availability of food and water, vermin, inadequate medical care, and lack of warm clothing and heating fuel. Sewage was worse than inadequate. Pervasive filth brought rampant disease. Tents and dugouts in the ground served as makeshift shelters as buildings were converted to hospitals for the growing number of sick. With only thin, lice-infested rags for clothes, the vast majority of prisoners were forced to live outside on the ground as late-fall overnight temperatures dropped near freezing. Up to twenty men a day died in the fall of 1864 owing to these harsh conditions. [60]

Many prisoners had to dig dugouts in the ground to escape the rain and cold. The food ration was inadequate to sustain a prisoner even if he was healthy, well-clothed and sheltered, which most were not. Food rations, if handed out, might consist of half a loaf of bread and a pint of rice soup with a layer of bugs swimming on top. One prisoner claimed he lost 95 pounds in less than three months, ending up at 87 pounds. [59]

When the prison was flooded with new captives in October, the guards were expected to control thousands of prisoners living unrestrained in the open prison yard. The guards marked a “dead line” six feet inside the wall and dared prisoners to cross it. Any inmate who even got close was shot. A few prisoners deliberately walked up to the line seeking relief from their miserable lives.

“Guard duty at the Prison was not popular. In 1861 the pay for a volunteer was $10 a month with a bounty of $11. By June 1862 the bounty had increased to $100 and guards were taken as young as 16 years of age. In July 1863 guard duty at the Prison was organized into a service known as the Home Guard with men between the ages of 18-50. The Senior Reserves took over the guarding of the Prison by the summer of 1864 and they were composed of men above 45 years old. These guards who came from various regiments including Gibbs Prison Guards, Howard’s Guards, Captain Henry Allen’s Company and Freeman’s Battalion oversaw approximately 15,000 prisoners from December 9, 1862 to February 22, 1865.” [61]

A new commandant, Major John Gee, was assigned to the Salisbury Prison late in the summer of 1864, about the same time the senior reserve guards arrived. Prisoners judged Gee to be “cold-blooded” and “brutal and avaricious, void of all sense of honor.” [62]

One of those prisoners who died in these harrowing times was Daniel Griffis. He arrived at Salisbury Prison on October 9, 1864, during a time when the prison was at its breaking point in terms of managing the prisoner population. After only three weeks at the prison, he was admitted to the prison hospital on October 30, 1984. He died a few days later on November 4, 1864 of “Int. fever”. [63] As stated at the beginning of this story, “Intermittent fevers” was a term that was used for a variety of illnesses, notably malaria. [64] After being a prisoner since August 13, 1863, 82 days as a prisoner during this ‘harrowing time’ undoubtably reduced his physical condition and health.

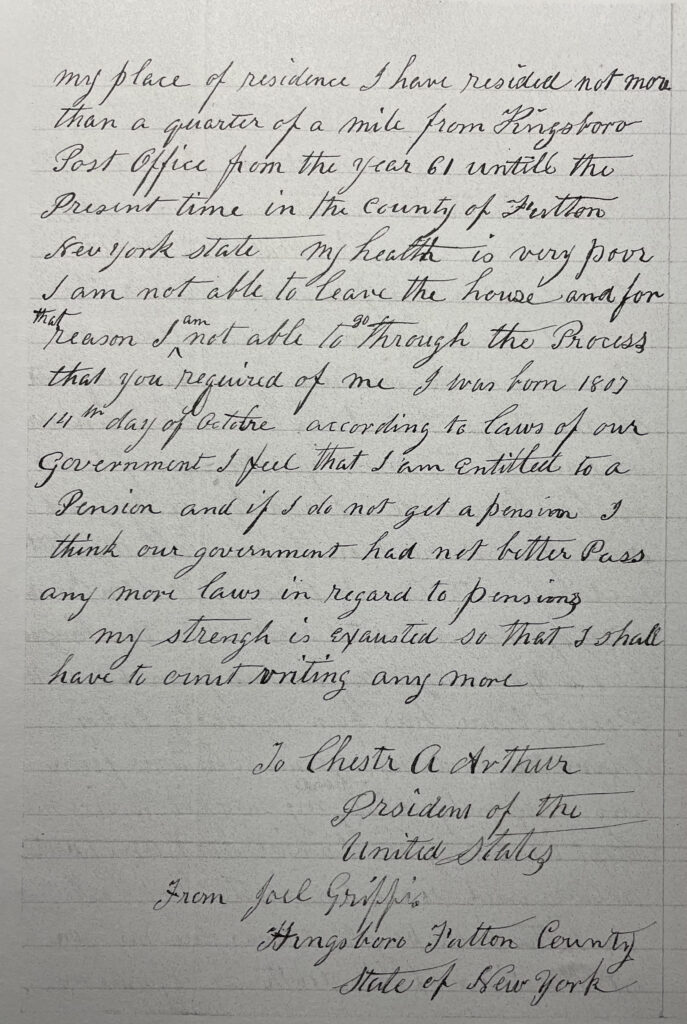

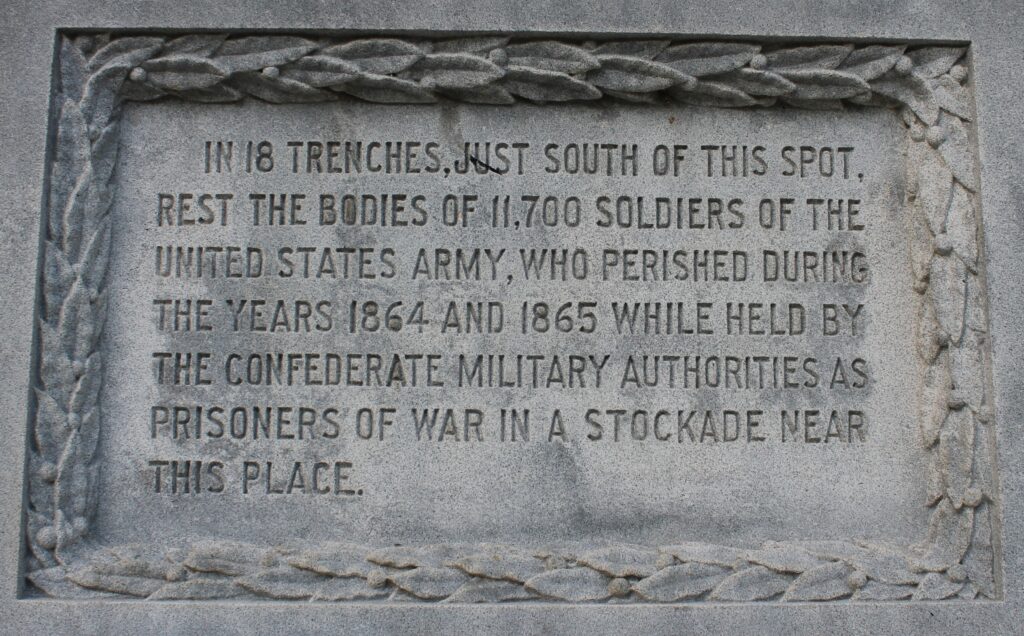

He was buried, as McCommon described seeing his deceased comrades of his Ohio regiment, in a trench with other prisoners. Many of the dead were buried in eighteen 240-foot-long trench graves without coffins in a former corn field. Exactly how many prisoners were buried in the trenches is not known. [65]

Shortly after he died, the most ambitious escape attempt by prisoners occurred on November 25, 1864, when captives rushed the prison gates, took guns from the guards, and tried to make a run into the woods. The guards fought back, firing a cannon three times and recaptured the men, who were weak from lack of food. About 250 men, including several guards, died in the desperate escape attempt. [66]

As a consequence of these conditions, Confederate authorities decided to remove the prisoners as soon as a safe place could be found for them. Out of the 10,000 or so prisoners, over 5,000 fell victim to starvation and disease. When it became apparent that the Confederacy was losing the war, the remaining Union prisoners were sent to Richmond, Virginia, and Wilmington, North Carolina.

February 1865, General Grant authorized a final prisoner exchange, and the Salisbury Prison was evacuated. By March 1865, all of the prisoners, except the infirm, had been evacuated.

“All POWs were transferred from Salisbury in February 1865, about six weeks before Maj. Gen. George H. Stoneman, on 12-13 Apr. 1865, destroyed the prison and other Confederate installations collectively known as the Salisbury Arsenal. In May Federal troops occupied the town, but in early September 1865 the Union commander turned over civil control of Salisbury to duly elected town officials. At the end of the war all Confederate property fell into Union hands and in September 1866 was sold at auction by the Freedmen’s Bureau to the Holmes brothers for $1,600.” [67]

In what became known as Stoneman’s Raid, Union General George Stoneman captured Salisbury and torched the prison April 12, 1865. Three days earlier, Confederate General Robert E. Lee had surrendered at Appomattox. Two days afterward, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated.

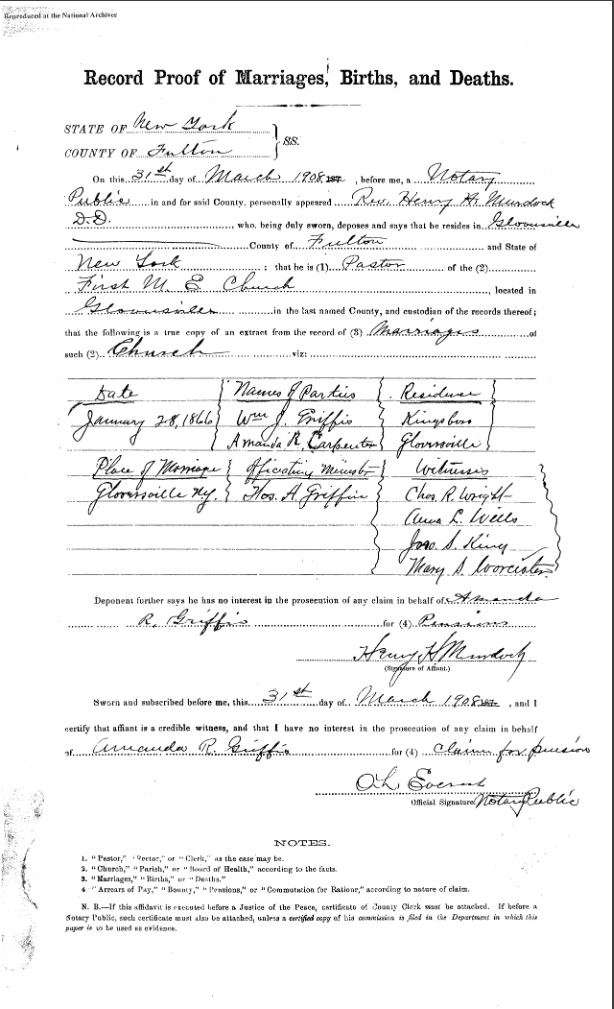

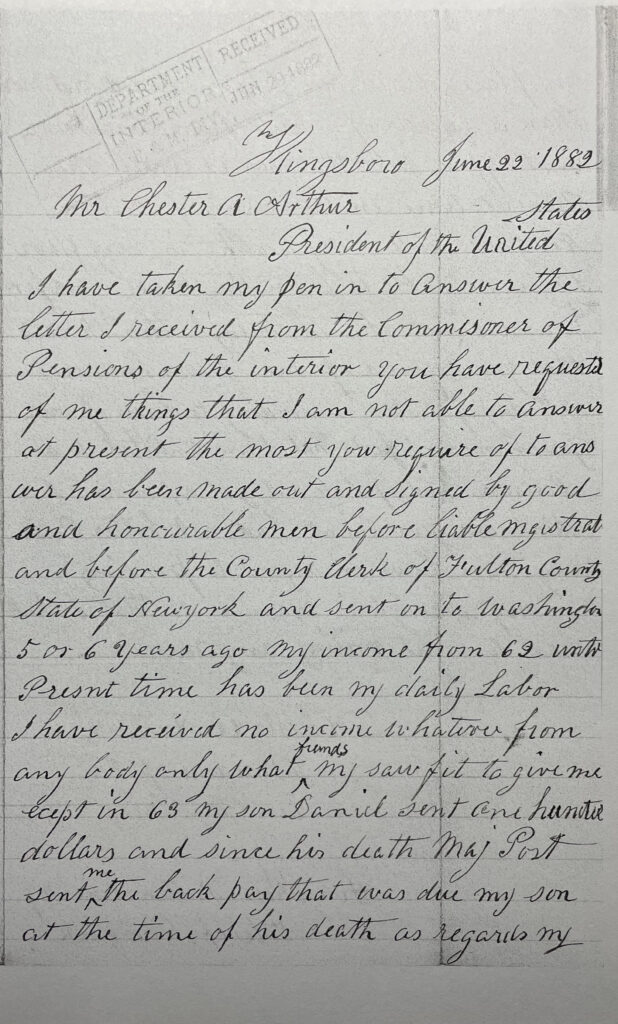

Aftermath of Daniel’s Death

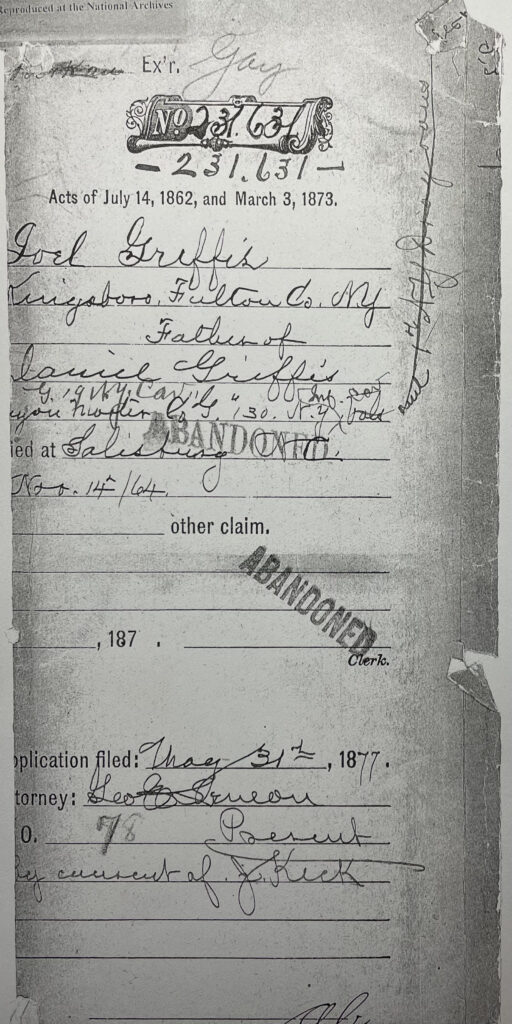

It is not known when William Griffis found out that his brother died in the Civil War. Nor do we know when his father Joel Griffis was advised of his son’s passing. We do know that Joel Griffis subsequently filed for a pension as a dependent of Daniel Griffis on May 31st, 1877. [68] After a long series of affidavits, requests for additional information, and correspondence, Joel abandoned his request for a dependency pension. Frustrated, demoralized and exhausted, he wrote a letter to President Chester Arthur on June 22, 1882.

Salisbury National Cemetery

Salisbury National Cemetery was established by Confederate authorities to serve as the burial ground for captured Union soldiers incarcerated at the prison in Salisbury. Recent historical research has led to a dispute over how many men are believed to have died during the last year of the war and are buried in the cemetery. The dead were buried in 18 trenches measuring about 240 feet long, located at the southeast end of the cemetery. Surrounding the burial trenches are three burial sites of 412 soldiers of the Civil War who had been buried at Lexington, Charlotte, Morganton, and other places, and were transferred to the national cemetery in 1866. Most of the soldiers are unknown.

Colonel Oscar A. Mack, the inspector of cemeteries, said in his report of 1870-71, “The bodies were placed one above the other, and mostly without coffins. From the number of bodies exhumed from a given space, researchers estimated that the number buried in these trenches was 11,700. The number of burials from the prison pen cannot be accurately known.” The figure of 11,700 was generally accepted for many years. However, the actual number of that were buried is probably lower and it is doubtful the exact number will be known and verified. An estimated 3,000 to 4,000 soldiers were likely buried at Salisbury Prison. The federal government was unable to verify the number of dead or compile a credible list of interments to a degree that would have allowed them to inscribe names on a single memorial or on individual headstones. [69]

The most accurate government-issued document associated with these burials is found in the Roll of Honor, No. XIV, compiled by the U.S. Army Quartermaster General’s Office, and published in 1868. Daniel Griffis is incorrectly listed as D.E. Griffith [70].

The cemetery was designated a national cemetery in 1865, but the land was not acquired until the early 1870’s. [71] The cemetery was dedicated in 1874, a wall was built around the perimeter the following year and by 1876 the headstones and a monument were in place.

Salisbury National Cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1999. [72]

National Salibury Cemetery, Photos by Jenny Dené-Hotchkiss:

Sources

Featured image: O’Sullivan, Timothy H., 1840-1882, photographer, photograph from the main eastern theater of war, winter quarters at Brandy Station, December 1863-April 1864. Library of Congress Supply trains of the great armies numbered thousands of six-mule teams and during a campaign march the wagon train would stretch for several miles.

[1] May 31, 1877 letter from U.S. Adjutant General’s Office to the Bureau of Pensions, Department of Interior, Part of the file of Joel Griffis application for a military pension on behalf of Daniel Griffis, Pension File Application No. 231.631, National Archives, Civil War Pensions.

[2] Goellnitz, Jenny, Civil War Medical Terms, E-History, Department of History, Ohio State University, Page was accessed January 19, 2021

[3] D. H. Rucker, D.H., Acting Quartermaster General, Brevet Major General, Quartermaster General’s Office, General Orders No. 7, February 20, 1868. Names of Soldiers who in Deference of the American Union, Suffered Martyrdom in the Prison Pens Throughout the South, Washington, Government Printing Office, 1868, Page 44 of the linked version, Page 134 of the original version.

[4] Grant, General Ulysses S. , The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, Old Saybrook Ct: Konecky & Konecky. (1886 and 1992). Pages 449-450

[5] Gallagher, Gary W., ed. The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864. Military Campaigns of the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006; Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001, Page 482; Wittenberg, Eric J. Little Phil: A Reassessment of the Civil War Leadership of Gen. Philip H. Sheridan. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2002, Page 58-60; Morris, Roy, Jr. Sheridan: The Life and Wars of General Phil Sheridan. New York: Crown Publishing, 1992, Page 182-184; Philip Sheridan, Wikipedia, page access January 10, 2021; Shenandoah Valley Campaigns, Britania Sheridan’s Valley Campaign of 1864, Page accessed January 20, 2021 ; Editors of History.net, Shenandoah Valley Campaigns, History.net, Updated page August 21, 2018, Original page march 21, 2011, Accessed January 28, 2021; Showdown in the Shenandoah Valley: 1864 Valley Campaign, Cedar Creek and Belle Grove, National Park Service, Last updated: February 26, 2015; Gallagher, Gary, ed., The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864 (Military Campaigns of the Civil War) Chapel Hill: University of North carolina Press, 2009

[6] Harpers Ferry and the Civil War Chronology, Harper’s Ferry national Park, National Parks Service, Department of Interior, Last updated: July 24, 2019

[7] Lackey, Rodney C., Notes on Civil War Logistics: Facts and Stories, United States Army Transportation Corps and Transportation School, Fort Lee, Virginia, date accessed December 15, 2020.

[8] Hess, Earl J., Civil War Logistics, A Study of Military Transportation, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2017, Chapter 6

[9] Hundred Days Men, Wikipedia, page last edited on 9 Nov 2018, page accessed 4 Jan 2021; Leeke, Jim, A hundred days to Richmond: Ohio’s “hundred days” men in the Civil War, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999; One Hundred Days Men, Ohio History Central, Page accessed 4 Ja 2021

[10] The 144th Ohio Infantry Regiment was mustered in at Camp Chase, May 11th, 1864, as a Ohio National Guard unit with 834 men, Colonel Samuel H. Hunt, reported at Baltimore and assigned to guarding fortifications in Maryland and Delaware; May 18th moved to meet Early’s invasion – Companies B, G, and I in Monocacy Junction battle, losing fifty killed, wounded and captured; July 13th returned to Washington, then into Virginia; attacked while guarding a train near Berryville, by Moseby’s command, loss five killed, six wounded, sixty captured; mustered out at Camp Chase, August 31st, about 700 men, Colonel Hunt commanding; of its captured many starved to death in Andersonville and other prisons.

The 149th Ohio Infantry was organized at Camp Dennison near Cincinnati, Ohio, and mustered in as an Ohio National Guard unit for 100 days service on May 8, 1864, under the command of Colonel Allison L. Brown. The regiment was attached to Defenses of Baltimore, 8th Corps, Middle Department, to July 1864. 1st Separate Brigade, 8th Corps, to July 1864. Kenly’s Independent Brigade, 8th Corps, to August 1864. The 149th Ohio Infantry mustered out of service at Camp Dennison on August 30, 1864.

[11] Source: Hundred Days’ Men, Ohio History Central, Page accessed 8 Feb 2021; One Days Men, Wikipedia, Page accessed was updated on 9 November 2018

[12] Tolles, LTC C. W. , An Army: Its Organization and Movements, Second Paper, Continental Monthly, Volume 6, Issue 1, July, 1864, Page 3

[13] Perkins, George, A summer in Maryland and Virginia; or Campaigning with the 149th Ohio volunteer infantry, a sketch of events connected with the service of the regiment in Maryland and the Shenandoah Valley, Virginia; Chillicothe, Ohio: The Scholl printing company, 1911, Page 32

[14] O.R., Series 1, Volume 11, Part 3, Chapter XXIII, pp. 376-377 , General Order 155,” actually published as a circular, dated August 14, 1862, from S. Williams, Adjutant General, Army of the Potomac Point 10: To each brigade train the brigade commander will assign a guard of companies of 100 men. No other men will be permitted to go with the wagons. These companies will permit no straggler of any command whatever to join the train, compelling all such to join their own regiments or march as prisoners and assist the guard in giving aid to the wagons. The officers will exercise their cool judgment and energy to expedite the march and not wait to be asked for assistance. ; Rusling, Captain J. F. (1865). A Word for the Quartermaster‟s, appearing in the United States Service Magazine, Volume III. NY: Charles R. Richardson. Page 256

[15] 43rd Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 11 December 2020, This page was edited on 11 December 2020 and page was accessed January 17, 2021;

[16] John S. Mosby, Wikipedia, Page was last edited on 11 December 2020, Page accessed January 4, 2021; Alexander, John H, Mosby’s Men. New York: Neale Publishing Company, 1907; Williamson, James Joseph. Mosby’s Rangers: A Record of the Operations of the Forty-third Battalion Virginia Cavalry. New York: Ralph B. Kenyon, 1896; Munson, John W. Reminiscences of a Mosby Guerrilla. New York: Moffat, Yard, and Co., 1906

[17] James Riley Bowen, Regimental History of the First New York Dragoons: Originally the 130th N. Y. Vol; Infantry; During Three Years of Active Service in the Great Civil War, originally published by author 1900, Reprinted by Forgotten Books, 2012, Page 213

[18] Perkins, George, A summer in Maryland and Virginia, Pages 33-34

[19] Munson, John W. Reminiscences of a Mosby Guerrilla. New York: Moffat, Yard, and Co., 1906, Page 106

[20] Ibid, Page 102-103

[21] Ibid, Page 105

[22] One Days Men, Wikipedia, Page accessed was updated on 9 November 2018

[23] National Republican (Washington, District of Columbia) · 22 Aug 1864, Mon · Page 2

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Munson, John W. Reminiscences of a Mosby Guerrilla, Pages 106-107

[27] Perkins, George, A summer in Maryland and Virginia, Pages 34-35

[28] Miller,Lieutenant Colonel Frederick R., Letter to the newspaper, The Wyandot Pioneer., Upper Sandusky, Ohio, September 02, 1864, Page 1 https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87076863/

[29] Munson, John W. Reminiscences of a Mosby Guerrilla, Page 108

[30] Ibid, Page 108

[31] Ibid, Page 110

[32] McCommon, William, Company A, 149th Ohio Volunteers Infantry, My Capture and Prison Life, in Perkins, George, A summer in Maryland and Virginia, Pages 39-45

[33] Thurson, J. M., Drawing, Company F, 90th Ohio Vols., View of Danville, VA Where Union Prisoners are Confined, 1865, Library of Congress

[34] McCommon, William, Company A, 149th Ohio Volunteers Infantry, My Capture and Prison Life, in Perkins, George, A summer in Maryland and Virginia, Page 41

[35] Sneden, Robert Knox , Drawing on map, Map showing route taken by Mosby with his prisoners, Nov. 27th-29th, 1863., Library of Congress

[36] History of Gordonsville, Virginia, Welcome to the Town of Gordonsville. Page accessed 2 Mar 2021

[36a] This map was added after I published the story. I used an 1864 map of Virginia to track Daniel’s journey, as described in William McCommon’s letter, ‘My Capture and Prison Life’.

“(This map was) prepared by the Coast Survey for the Union Army in October 1864. The Civil War had turned decisively in favor of the Union, with Grant besieging Lee in Petersburg, Virginia since June and Sherman capturing Atlanta in September. This was the finest available map of the region, and copies would likely have been rushed to officers both at headquarters and in the field.

“At the outset of the Civil War, it became apparent to the Union leadership that there were few reliable maps available of the likely theatres of war in the Confederate states. As the Fedeal Government’s most sophisticated mapping agency the Coast Survey was quickly recruited into the war effort, tasked with compiling the best available information, and creating up-to-date maps of the southeastern United States. By the standards of their time, the resulting maps were superbly detailed, providing commanders with essential data about the natural and human geography of the regions in which they were operating.

“This map of Virginia and West Virginia is a fine example of the Coast Survey’s work. It is a compilation likely based on commercial and official sources including the Boye-Bucholtz map of Virginia (1859), the charting work conducted by the Coast Survey in the Chesapeake and on its tributary rivers, and field surveys conducted by Union engineers. The map places particular emphasis is placed on the transport networks essential to troop mobility and supply, with rivers and railroads highlighted with blue and red overprinting. Also of interest is West Virginia, admitted to the Union only in June 1863, its borders and name also highlighted in blue and red. Richmond, the ultimate target of Grant’s siege of Petersburg, is surrounded by concentric red circles at 10-mile intervals, fittingly placing it at the center of a massive bullseye.

“(This map) was first issued in 1862, though with significantly less interior detail and a somewhat different color scheme. It appeared again in 1863 and earlier in 1864, before this final edition appeared. All prior states of the map feature blue concentric distance circles around Washington, which have been removed from this edition.”

Map of the State of Virginia, issued by Bache and the Coast Survey in 1864, Compiled by W[alter] L. Nicholson / Lith. by Cha[rle]s G. Krebs, MAP OF THE STATE OF VIRGINIA Compiled from the best authorities and printed at the Coast Survey Office. Washington: United States Coast Survey, October 1864

[37] Costa Dora L. and Mathew Kahn, ” Surviving Andersonville: The Benefits of Social Networks in POW Camps”, American Economic Review 97, no. 4, September, 2007, Page 1468;

[38] American Civil War Prison Camps, Wikipedia, Page accessed January 28, 2021

[39] Kutzler, Evan, Living by Inches, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2019, Page 11

[40] Kutzler, Evan, Living by Inches, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2019, Page 10

[41] Richmond Prisons, Civil War Richmond, Page accessed 10 Oct 2020

[42] Prisoners in Richmond, National Parks Service, Richmond National Battlefield Park, Updated page 27 Sep 2017, accessed 15 Dec 2020

[43] Charles R. Rees, ca. 1863, Mounted photographic source: Valentine Richmond History Center; Belle Isle Prison, Encyclopedia Virgina

[44] Galuszka, Peter, A Deathly Island: Looking Back at Belle Isle’s Horrific Past, Style Weekly, 29 Oct, 2013, Page accessed 3 Mar 2021; Belle Isle Prisoner of War Camp, My Civil War, Page accessed 3 Mar 2021; Prisoners in Richmond, National Parks Service, Richmond National Battlefield Park, Updated page 27 Sep 2017, accessed 15 Dec 2020

[45] McCommon, William, Company A, 149th Ohio Volunteers Infantry, My Capture and Prison Life, in Perkins, George, A summer in Maryland and Virginia, Page 41-42

[46] A Richmond prisoner U.S. General Hospital, Div. No. 1, Annapolis, Md., Private Jackson O. Broshears [i.e. Brashears], Co. D, Indiana Mounted Infantry. On the back of the photograph: Age 20 years; height 6 feet 1 inch; weight when captured, 185 lbs.; was in rebel hands three and one-quarter months, 2 months of which were passed on Belle Isle. Under treatment in U.S. Hospital 8 weeks – constantly improving – now, May 19th, 1864, weighs 108-1/2 lbs., photographer not known, Albumen print, 1864

[47] Robert C. Black, Robert C., The Railroads of the Confederacy, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998. Page 361

[48] McCommon, William, Company A, 149th Ohio Volunteers Infantry, My Capture and Prison Life, in Perkins, George, A summer in Maryland and Virginia, Page 43

[49] Confederate Prison (Salisbury), NCpedia, 2006, Page accessed 3 Oct 2020

[50] Railroads of the Confederacy, American Battlefield Trust, internet page accessed January 28, 2021; Ramsdell, Charles, The Confederate Government and the Railroads, The American Historical Review, Vol. 22, No. 4 (July, 1917) pp. 794-810; Robert C. Black, Robert C., The Railroads of the Confederacy, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998

[51] Gallagher, Gary, Insight: Off the Tracks, History.net, June 2019

[52] Map from Robert C. Black, Robert C., The Railroads of the Confederacy, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998

[53 ]Kraus, C. A, and J.H. Bufford’S Sons Lith. Bird’s eye view of Confederate prison pen at Salisbury, N.C., taken in. Boston ; New York: J.H. Bufford’s Sons Lith, 1864. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/84692279/.

[54] Walker, Leroy Pope, Governor’s Correspondence: Letter Authorizing the Establishment of a Confederate Prison in Salisbury, N.C., North Carolina digital Collections, July 18, 1861

[55] Salisbury Prison, Anchor, North Carolina Online History Resource, Page accessed January 25, 2020; Brown, Louis A., Confederate Prison (Salisbury), from the Encyclopedia of North Carolina edited by William S. Powell. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006; Kutzler, Evan, Living by Inches, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2019, p 9

[56] Louis A. Brown, The Salisbury Prison: A Case Study of Confederate Military Prisons, 1861-1865 (1992); Sanders, Charles W., While in the Hands of the Enemy: Military Prisons of the Civil War, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University press, 2005; Brown, Louis A., Confederate Prison (Salisbury), from the Encyclopedia of North Carolina edited by William S. Powell. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006 ; Hesseltine, William B., ed., Civil War Prisons, Kent: Kent State University Press, 1977; Prison History, Salisbury Confederate Prison Association, Page accessed 15 Jan 2021; Annette Gee Ford, The Captive: Major John H. Gee, Commandant of the Confederate Prison at Salisbury, North Carolina, 1864-1865, North Carolina, manufacturer not identified, 2000; Joel R. Stegall, Salisbury Prison: North Carolina’s Andersonville, North Carolina History Center, : Civil War and Reconstruction, September 13, 2018, Page accessed 14 Jan 2021; Pike, Thomas, Salisbury prison was final stop for many, Post Bulletin PostBulletin.com , Rochester, NY, October 16, 2012

[57] McCommon, William, Company A, 149th Ohio Volunteers Infantry, My Capture and Prison Life, in Perkins, George, A summer in Maryland and Virginia, Page 43

[58] Salisbury Prison, The American Civil War, Page accessed 11 Feb 2021; Louis A. Brown, The Salisbury Prison: A Case Study of Confederate Military Prisons, 1861-1865 (1992); Brown, Louis A., Confederate Prison (Salisbury), from the Encyclopedia of North Carolina edited by William S. Powell. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006 ; Prison History, Salisbury Confederate Prison Association, Page accessed 15 Jan 2021; Annette Gee Ford, The Captive: Major John H. Gee, Commandant of the Confederate Prison at Salisbury, North Carolina, 1864-1865, North Carolina, manufacturer not identified, 2000; Joel R. Stegall, Salisbury Prison: North Carolina’s Andersonville, North Carolina History Center, : Civil War and Reconstruction, September 13, 2018, Page accessed 14 Jan 2021;

[59] Joel R. Stegall, Salisbury Prison: North Carolina’s Andersonville, North Carolina History Center, : Civil War and Reconstruction, September 13, 2018, Page accessed 14 Jan 2021

[60] Pike, Thomas, Salisbury prison was final stop for many, Post Bulletin PostBulletin.com , Rochester, NY, October 16, 2012

[61] Prison History, Salisbury Confederate Prison Association, Page accessed 15 Jan 2021

[62] Joel R. Stegall, Salisbury Prison: North Carolina’s Andersonville, North Carolina History Center, : Civil War and Reconstruction, September 13, 2018, Page accessed 14 Jan 2021; Springer, Paul J., and Robins, Glenn. Transforming Civil War Prisons: Lincoln, Lieber, and the Politics of Captivity, p. 112. London: Routledge, 2014.

[63] Daniel Griffis, Salisbury National Cemetery Memorial, Find A Grave. Page accessed 10 Mar 2021

[64] Goellnitz, Jenny, Civil War Medical Terms, E-History, Department of History, Ohio State University, Page was accessed January 19, 2021

[65] Salisbury National Cemetery, Wikipedia, Page was last edited on 13 February 2021, Page access 11 Mar 2021.

[66] Salibury Prison, Anchor, North Carolina OnLine History Resource, “Salisbury Prison.” Session 4: The War in North Carolina | NC Museum of History. Accessed June 05, 2019. https://www.ncmuseumofhistory.org/session-4-war-north-carolina.

[67] Brown, Louis, Confederate Prison (Salisbury), NCpedia, Page accessed 3 Oct 2020

[68] Application of Joel Griffis for Dependency Pension, Claim 231.631, May 31, 1877.

[69] Salisbury National Cemetery, Historical Information, National Cemetery Administration, U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, Page updated 20 May 2020, accessed 15 Jan 2021

[70] Drucker, D.H. Acting Quartermaster General, Quartermaster General’s Office, General Orders No. 7, February 20, 1868, Roll of Honor, No. XIV, Names of Soldiers who in Defense of the American Union Suffered Martyrdom in the Prison Pens Through Out the South, Washington: Government Printing Office, Page 134

[71] Therese T. Sammartino (February 1999). “Salisbury National Cemetery” (pdf). National Register of Historic Places – Nomination and Inventory. North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office. Sectrion 8 ,Page 12

[72] Salisbury National Cemetery, Wikipedia, Page accessed on 21 Feb 2021 was last modified on 13 February 2021