As recent as 2022, it was found that most Americans value living close to their families. In general, over half of adults in America live within an hour’s drive of some of their extended family members. This trend is affected by a variety of factors such as income status, ethnicity, gender, age, urban or rural areas, and education levels. [1]

Living next to or near siblings or other family members while raising a family has been a common practice through time. While it was not uncommon for families of the same extended family to live close to each other in the 1800’s, it is a delight to find such a discovery in the 1800s through family research.

This is a story of two families, connected by two sisters and perhaps connected also by the occupations of their husbands in the glove making business. They lived close to each other on South Main Street in Gloversville, New York in the late 1800s while their families were growing up.

The Two Sisters: Rosa and Sophie Fliegels’ Marriages

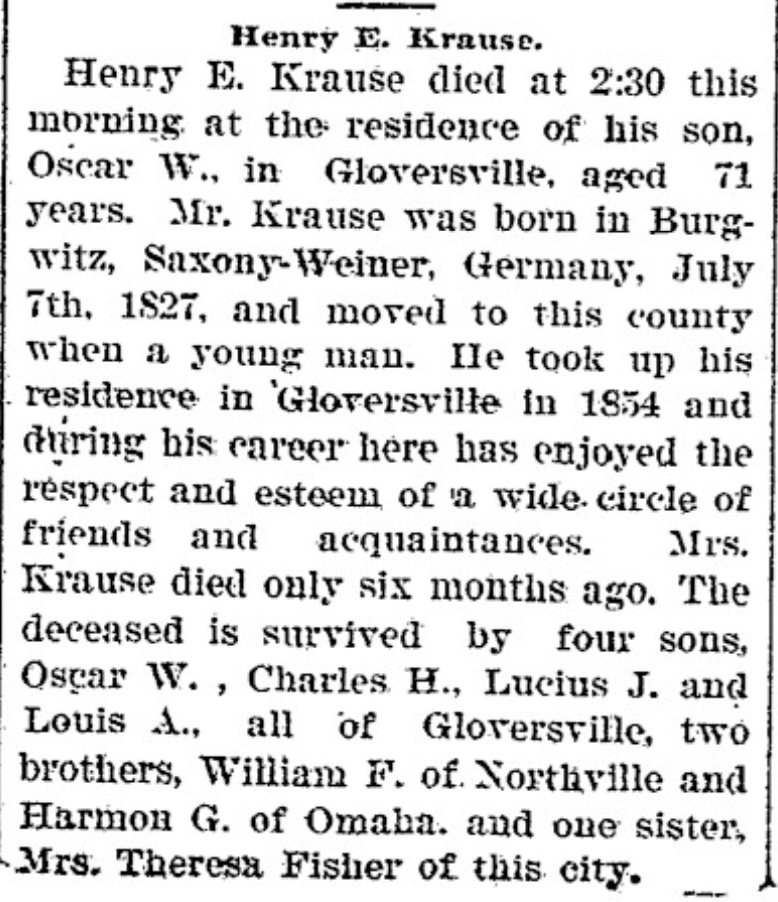

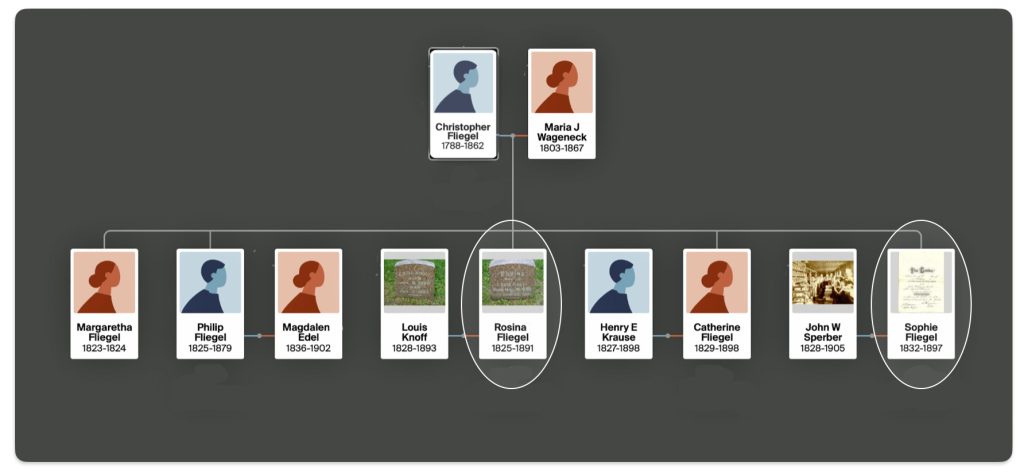

The two sisters in question are Rosa (Rosina) Fliegel and Sophie Fliegel. The two sisters were part of the second generation of the Fliegel family that established roots in the Gloversville area in the mid 1800s. Following the footsteps of their sister Catherine, both sisters immigrated to the United States with their parents and their brother Philip.

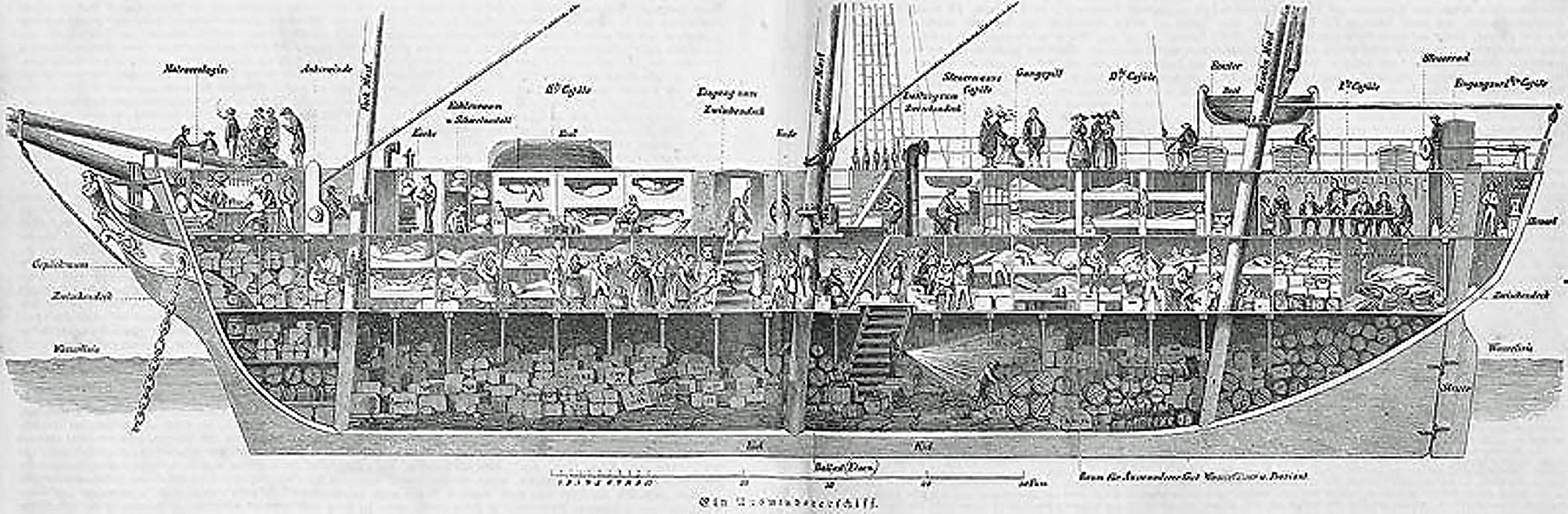

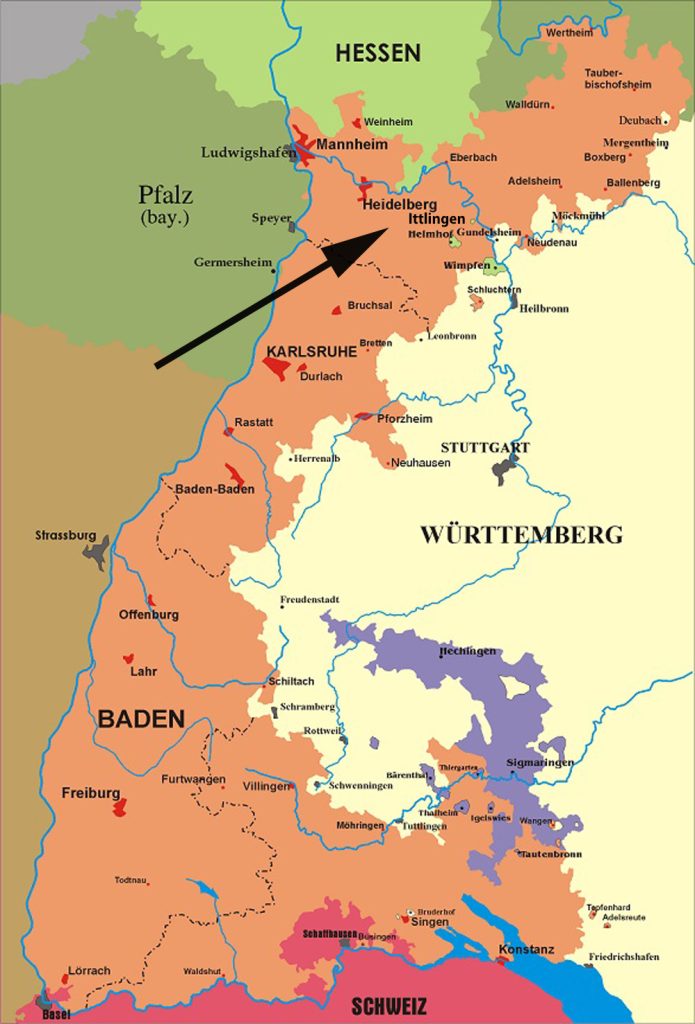

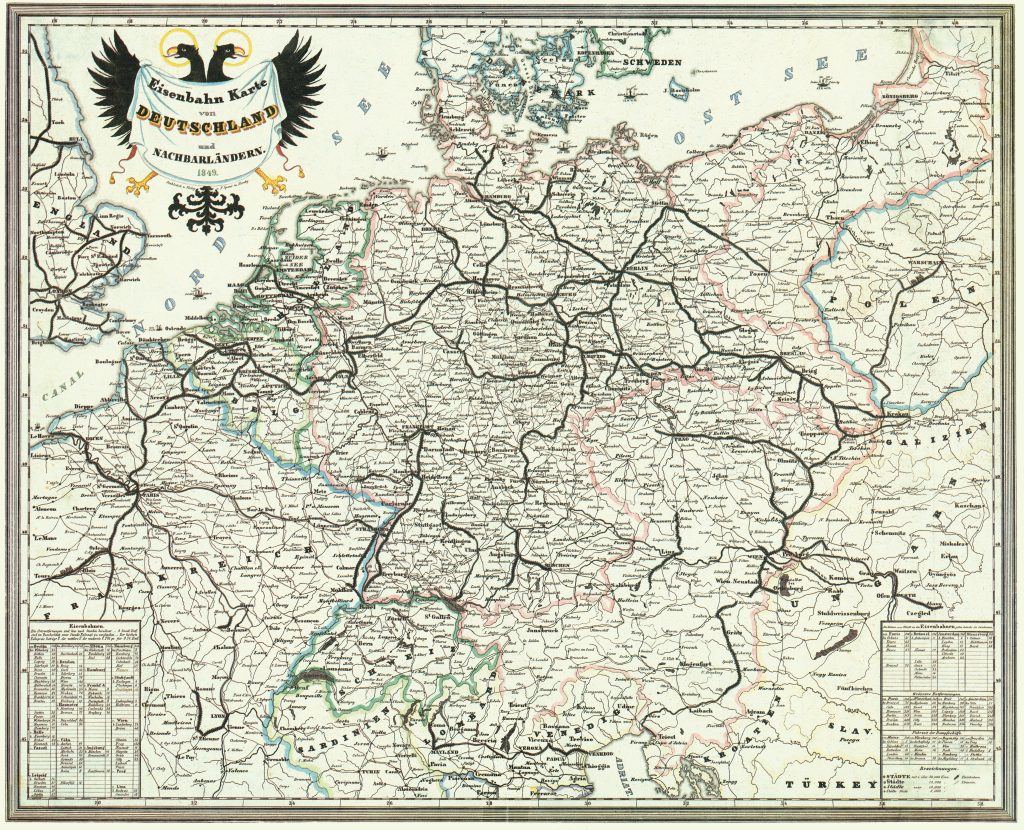

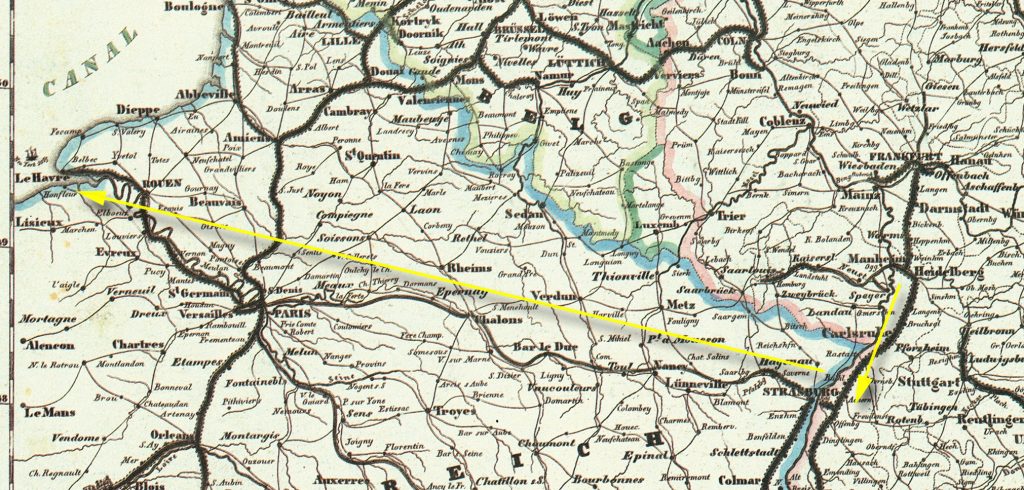

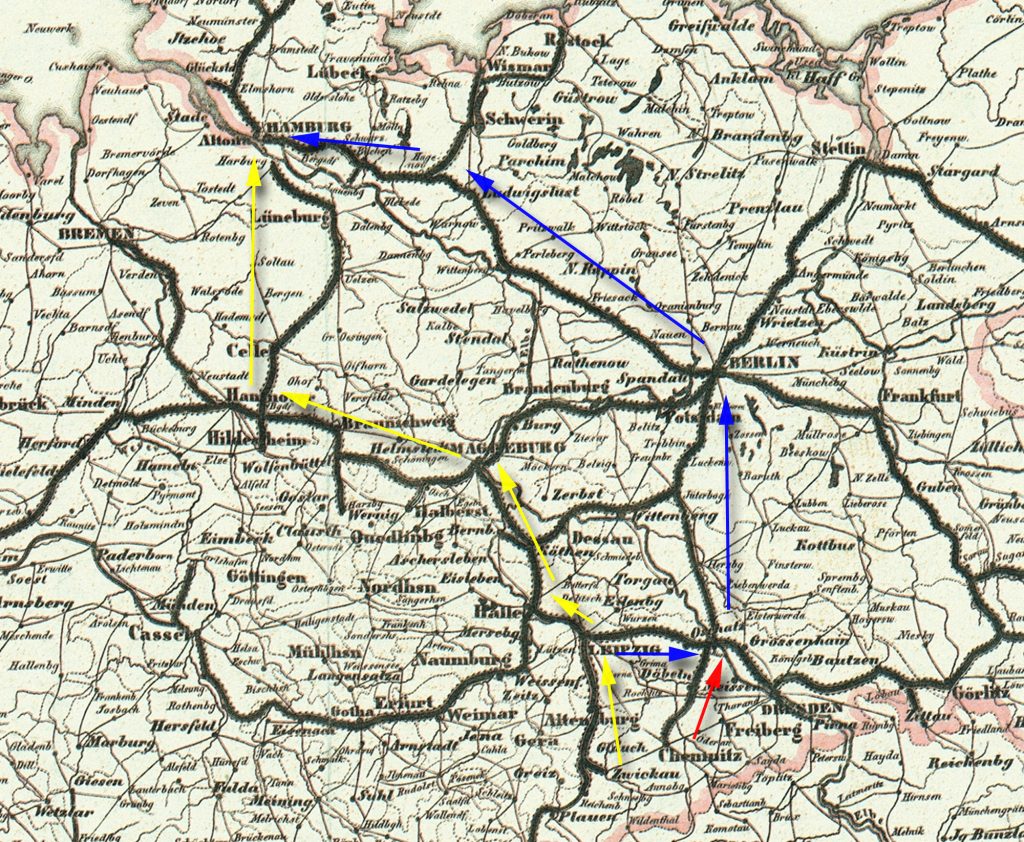

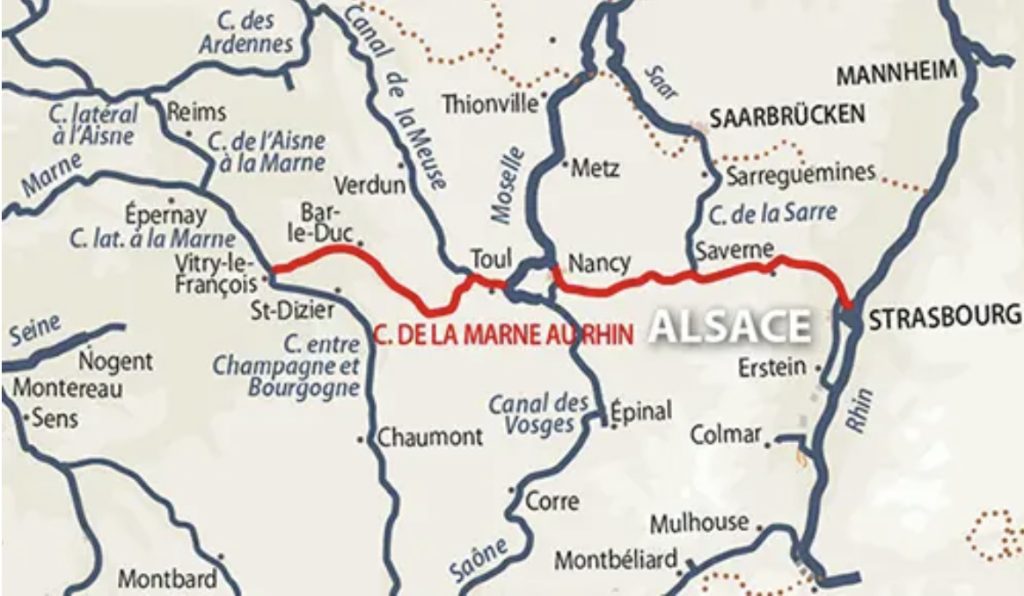

The Fliegel family emigated from the Ittlingen, which is about 27 miles southwest of Heidelberg, in the Grand Duchy of Baden in 1854. The family followed the migratory path of Catherine who arrived in America in 1848. [2]

The First and Second Generation of the Fliegel Family from Ittlingen, Baden

John Wolfgang Sperber came to America on his own from Baden in 1852. Similar to the Fliegel family, he ended up in the Gloversville area. [3]

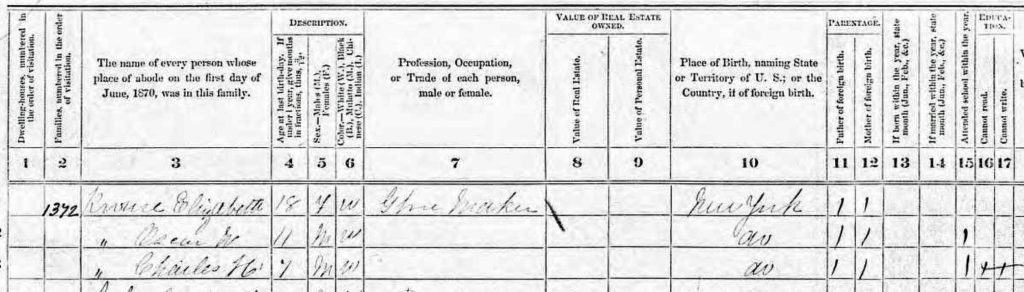

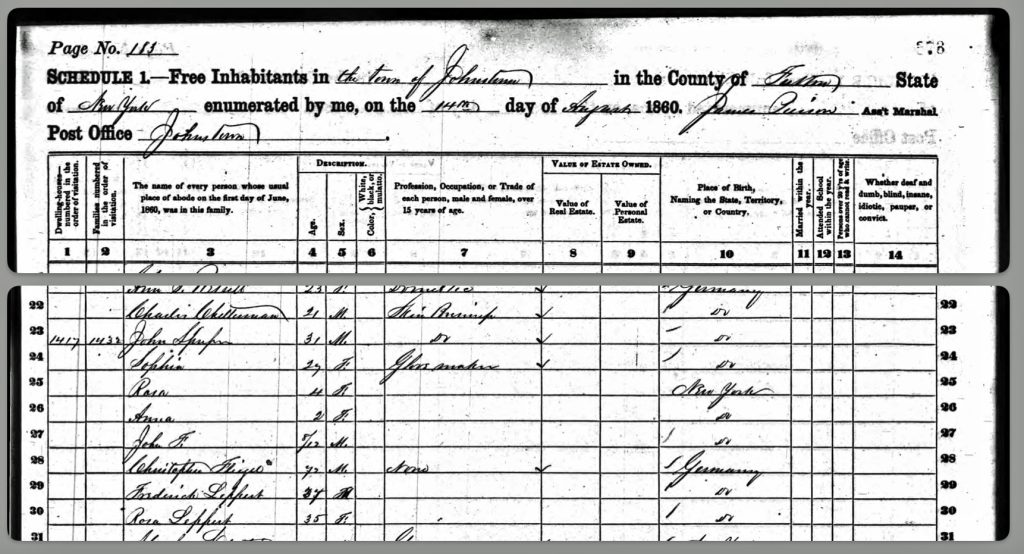

Sophie Fliegel married Johann Wolfgang Sperber in February 1857. They would be the maternal grandparents of Harold Griffis 46 years later. John and Sophie Sperber quickly started a family. Three years after their marriage, their young family consisted of Rose (age 4), Anna (age 2), and John Frederick (8 months). They also had Sophia’s father, Christoph, living with them as well as two boarders. [4]

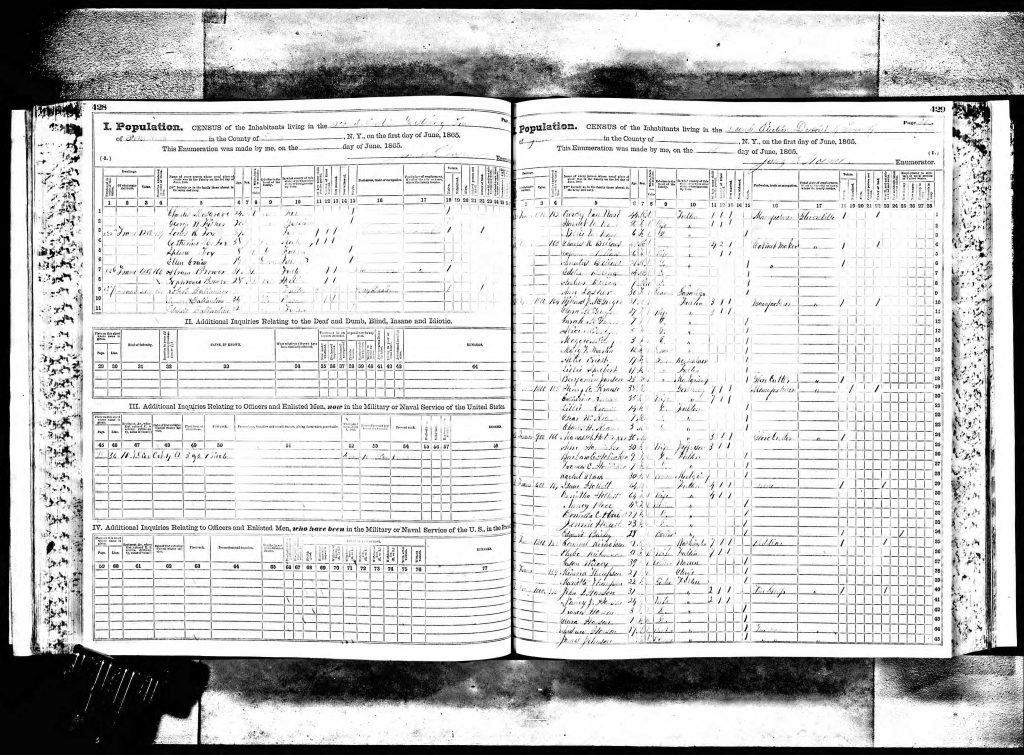

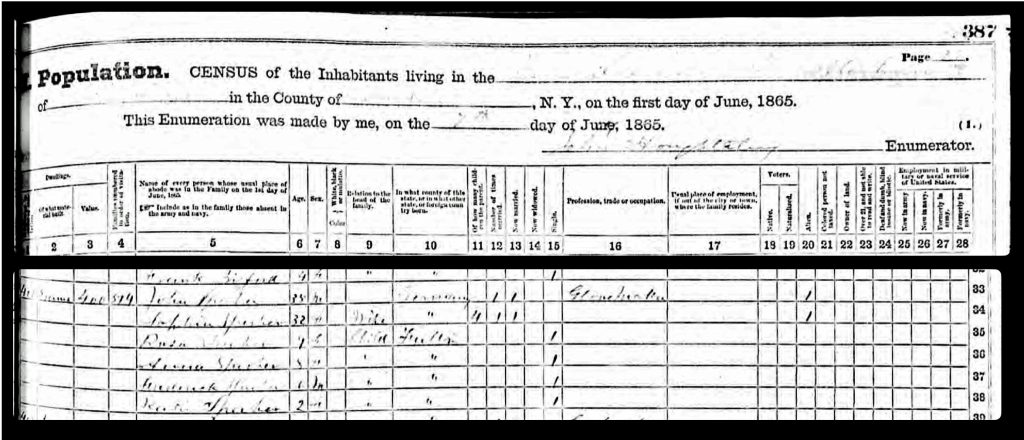

In 1865, John is reported to be 35 years old and his wife Sophie is 32. Four of their children were living at the time: Rosa (Rose) at 9 years of age, Anna at 8, (John) Frederick at 6 and Katie or Kathryn at 2 years of age. Other records indicate that Kate Sperber was born on January 1, 1864. [5]

While they are found in the 1860 Federal census and the 1865 New York state census, specific addresses for the households were not documented. It is not known specifically where John and Sophia lived between 1857 and 1868. In 1868, the family moved to South Main Street.

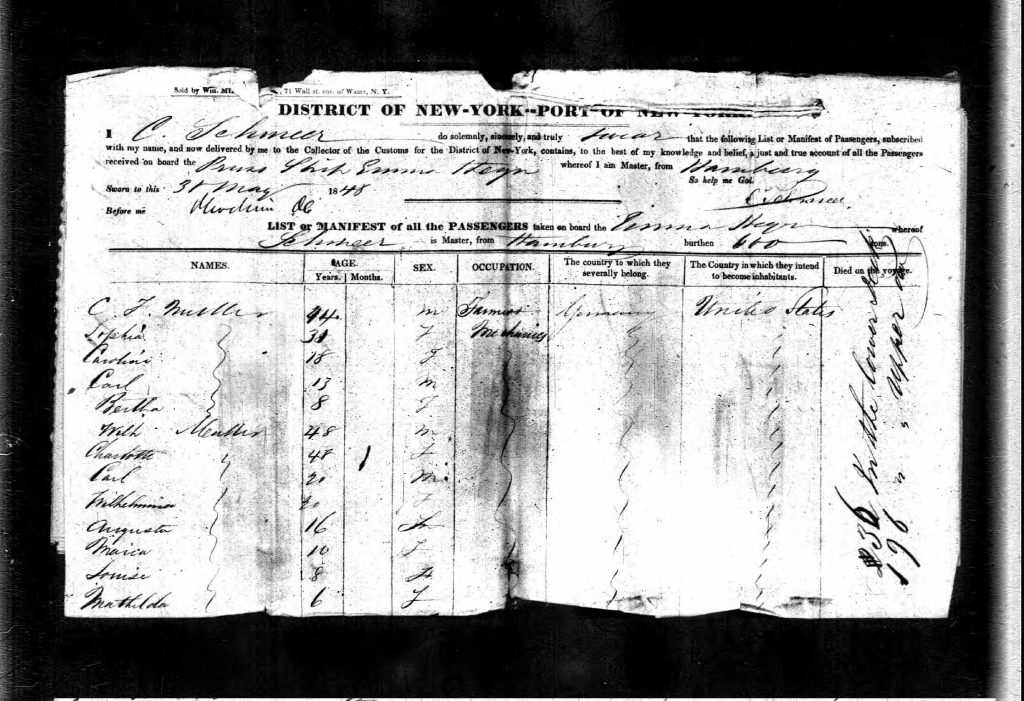

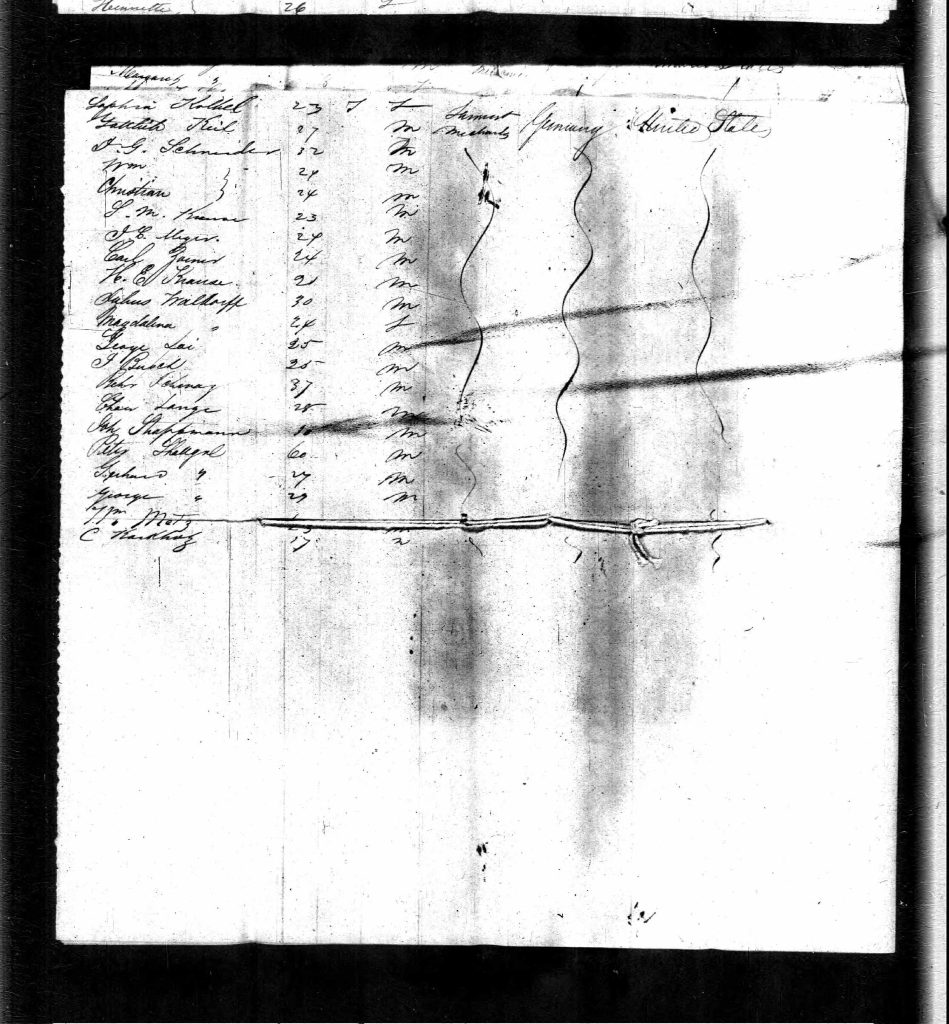

Rosa Fliegel was the oldest living child of Christopher and Maria Fliegel. Based on available historical records, not much is known about Rose or Rosina Fliegel. Ship manifest records [6], indicate Rose was 28 when she arrived in January of 1855 to the United States. Birth records indicate she was born in March 4th 1825 which suggests that she was 30 when she arrived in January of 1855. [7] No records have been found of her residence in Gloversville until 1870 when she appears in the U.S. Federal Census.

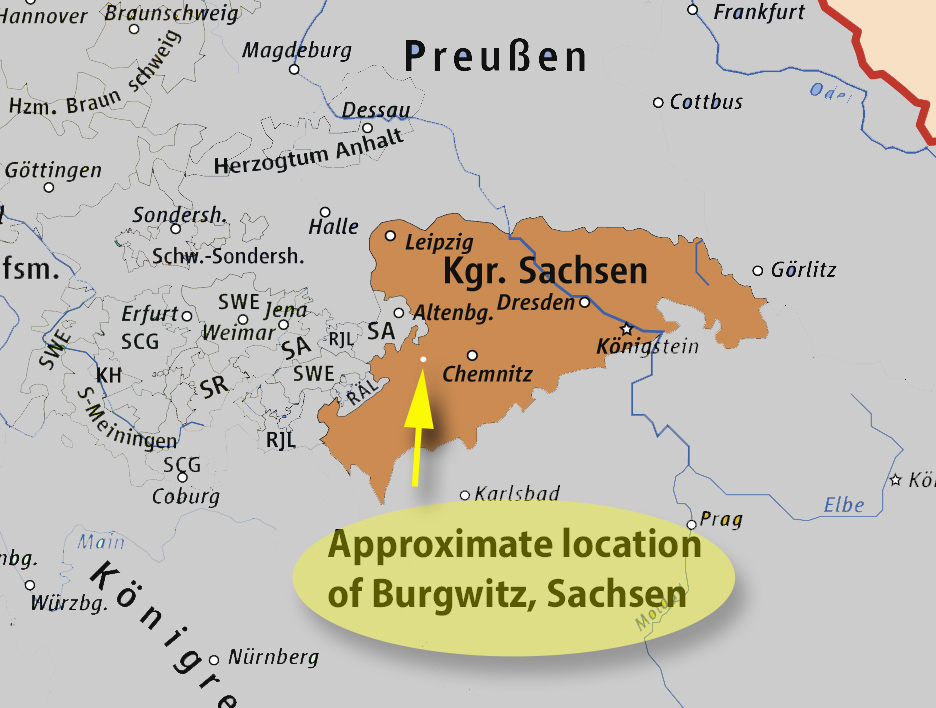

Rose married relatively late in life at the age of 40 or 41. She married Louis Knoff. At the time Louis was a widower with one son named Herman. Louis was born on January 8, 1828 in Bernstadt, Schlesien, Prussia. [8] As reflected in Map One below, Bernstadt was part of the Prussian Province of Silesia and was a province of Prussia from 1815 to 1919. [9]

Map One: Birthplaces of Louis Knoff and Rosina Fliegel [10]

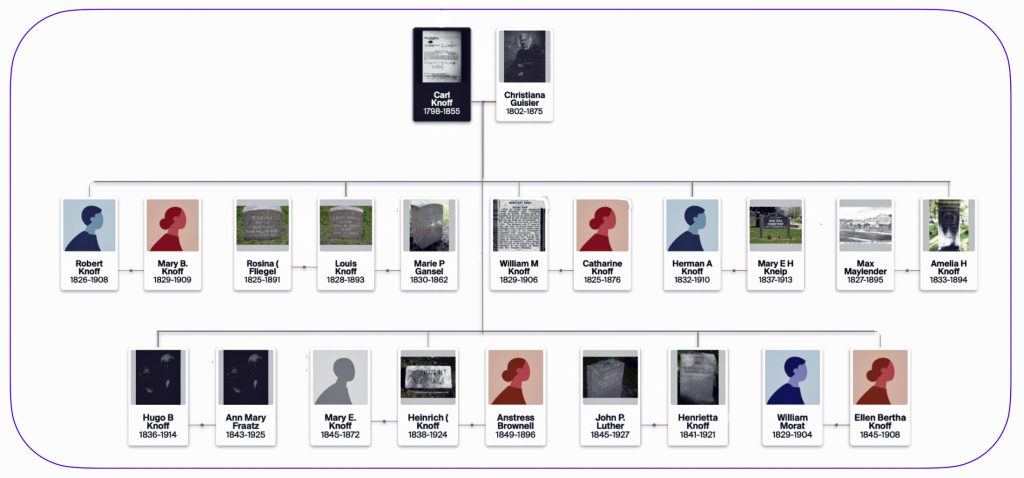

Louis Knoff came from a large family of nine brothers and sisters. All of the family members immigrated to the United States but at different times. Moreover, they all settled in different areas. Louis Knoff was the second oldest sibling in the family. He came to the United States in 1849. [11]

Louis Knoff learned his trade in the leather tanning trade in Breslau, Prussia. He apparently came directly to Gloversville to apply his trade. He started working in tanning shops in Johnstown. He eventually started his own business in Gloversville in 1861 which flourished. The tanning mill was near the railroad station. He then built a factory and tannery in 1865 on South Main Street. He became a “prominent manufacturer” in Gloversville. [12]

Louis Knoff originally married Pauline Hansel in 1856. Similar to her husband, Pauline also emigrated from Prussia in 1849 at the reported age of 19. She was from Landsberg, Prussia . [13]

Louis and Pauline had one son, Herman Knoff, within the following year of their marriage. [14] Pauline however died at the young age of 31 in 1862. Louis remarried four years later in 1866, a year after he started his tanning factory, to Rosa Fliegel. They had a son Louis Jr. in 1870. [15]

Rosa and Louis Knoff Move to South Main Street

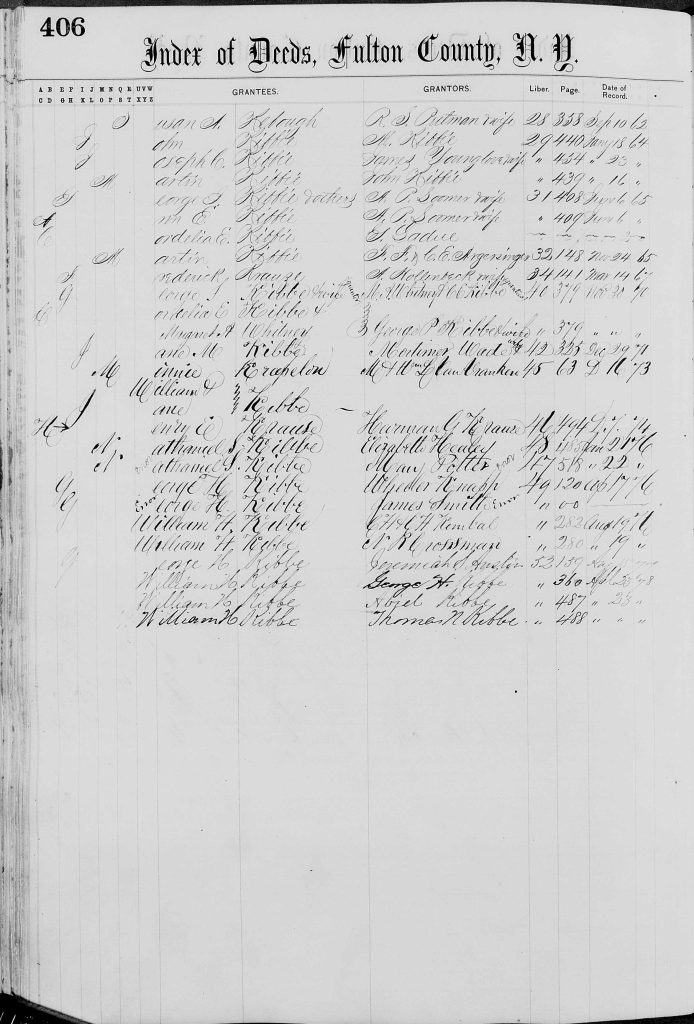

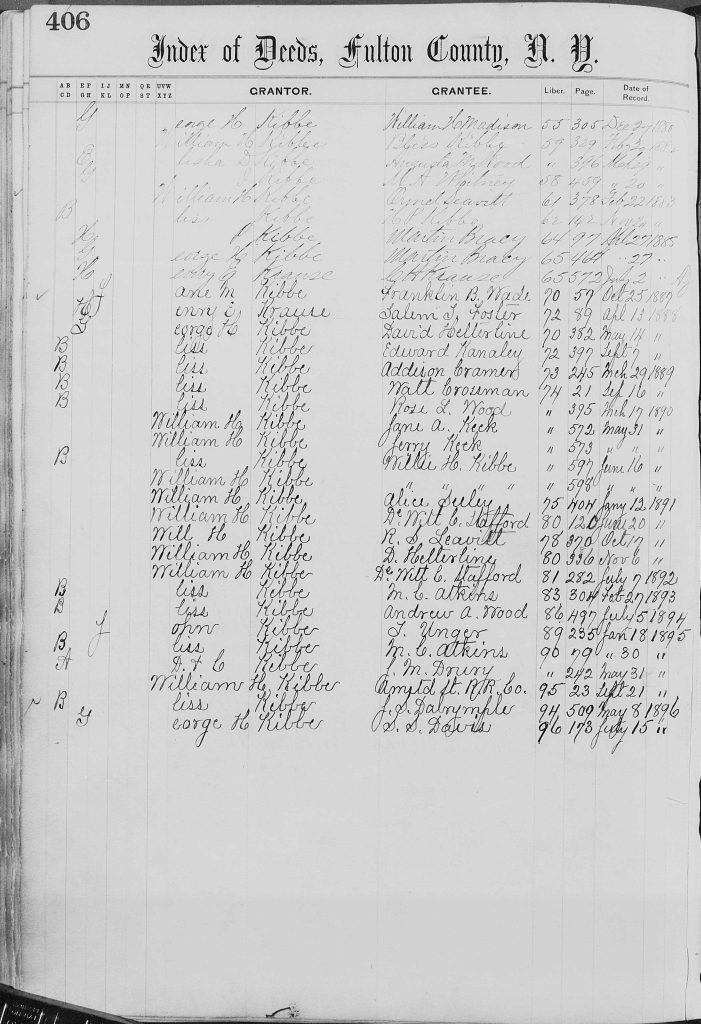

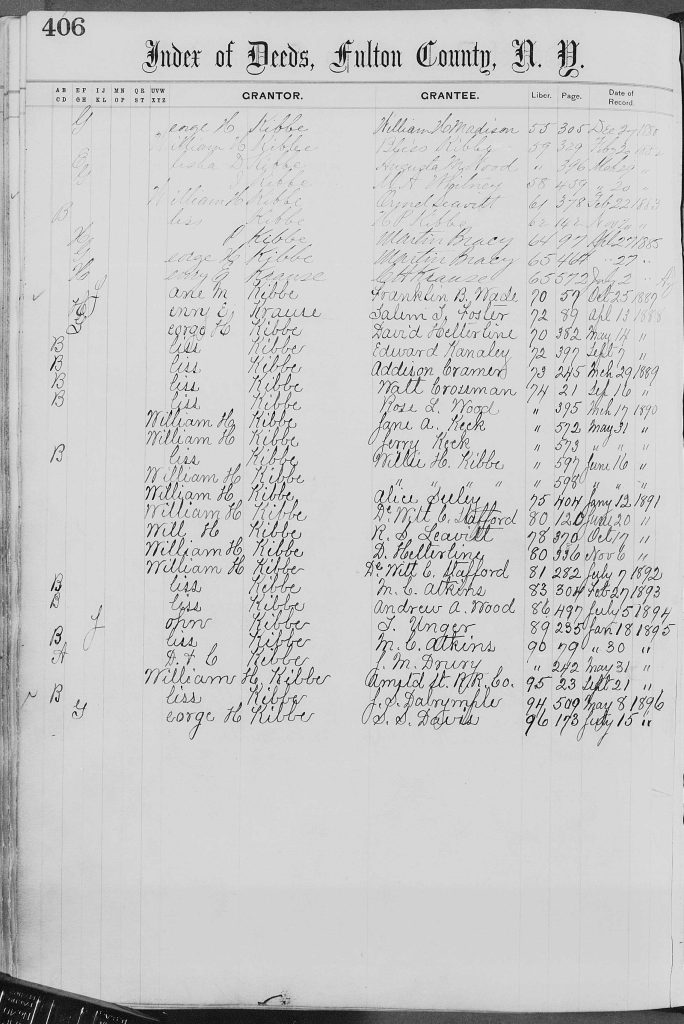

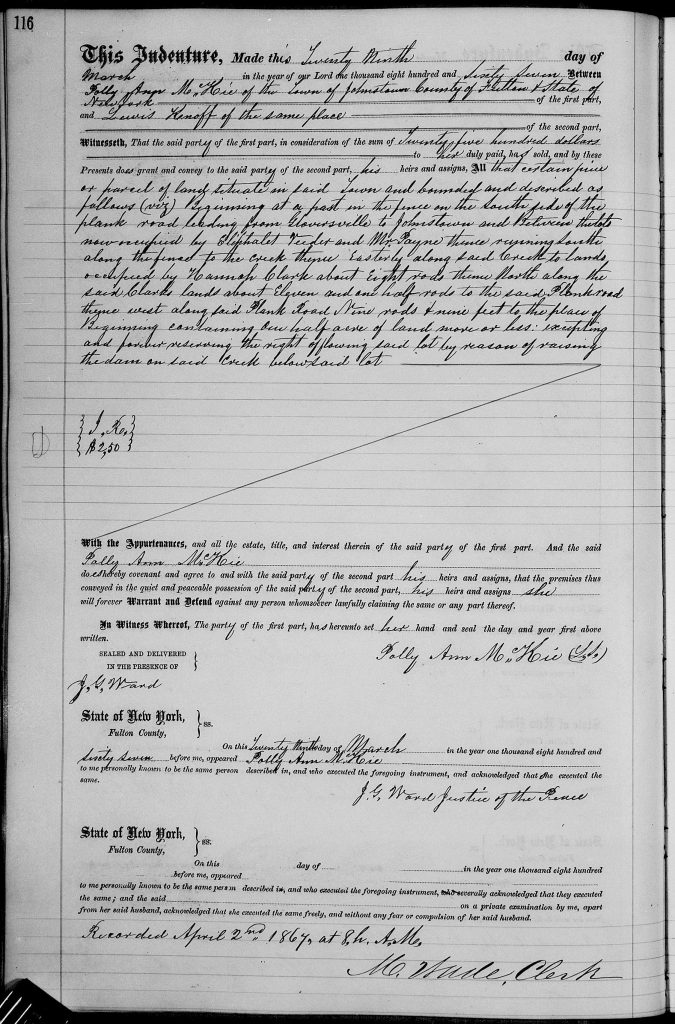

A review of land records indicate that Louis Knoff purchased a tract of land on South Main Street along the Cayadutta Creek in 1867. [16] While the information in Louis Knoff’s obituary indicated he built a factory and tannery on South Main Street in 1865, I have not found any land deeds in 1864 or 1865 for Louis Knoff.

The land indenture was made on March 29, 1867. Louis purchased the land from Polly Ann M. McKie of Johnston, Fulton County for the sum of $2,500 dollars. $2,500 in 1867 is equivalent in purchasing power to about $53,131.76 today. [17]

The half acre of land was described as follows: “Beginning at a post in the fence on the South side of the plank road leading from Gloversville to Johnstown and between the lots now occupied by Eliphalet Veeder and Mr. Payne thence running South along the fence to the creek thence Easterly along said creek to lands occupied by Hannah Clark about Eight rods thence North along the said Clarks lands about Eleven and one half rods to the said Plank road thence west along said Plank Road Nine rods & nine feet to the place of Beginning containing one half acre of land more or less: excepting and forever reserving the right of flowing said lot by reason of raising the dam on said creek below said lot…”

I attempted to find the location of the property based on locating the Veeder and Payne households that are referenced in the deed in the 1865 New York state census. I found an ‘Eliphalet Veeder in the 1865 census but did not find a Payne household nearby. [18]

Land Indenture for Louis Knoff – March 29, 1867

“United States, New York Land Records, 1630-1975.”Database with images. FamilySearch. https://FamilySearch.org : 14 June 2024. Multiple county courthouses, New York.

The deed refers to “Plank Road” that was between Gloversville and Johnstown, next to the Cadayutta Creek. In Gloversville, this was South Main Street. Plank roads were wooden roads that were very popular in New York in the 1840s and 1850s before the widespread adoption of railroads and paved roads. The roads typically consisted of hemlock planks that were eight to nine feet wide and two to four inches thick, covering one lane while the other lane was often left unpaved. Loaded wagons would take the planked lane, while empty wagons used the dirt lane. Ditches were dug on each side for drainage. [19]

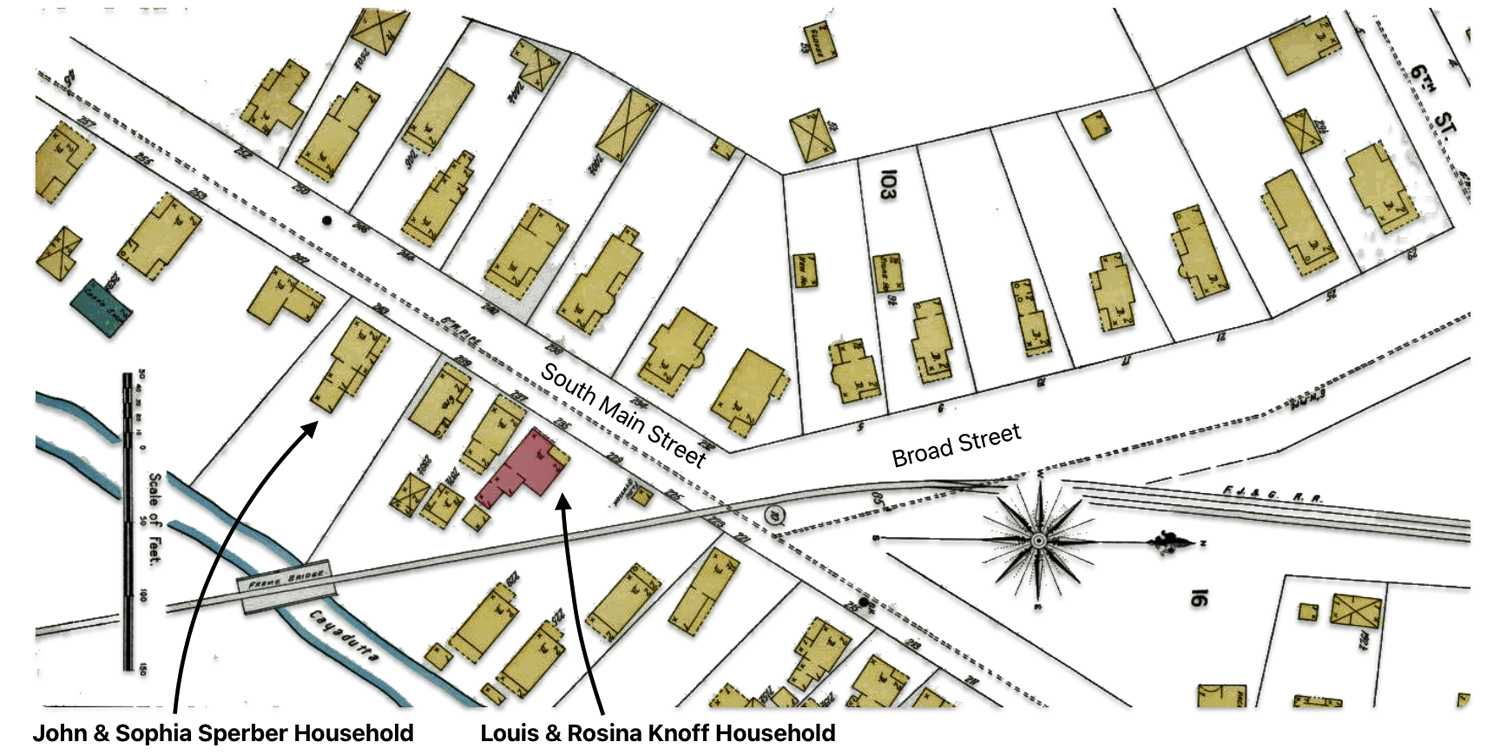

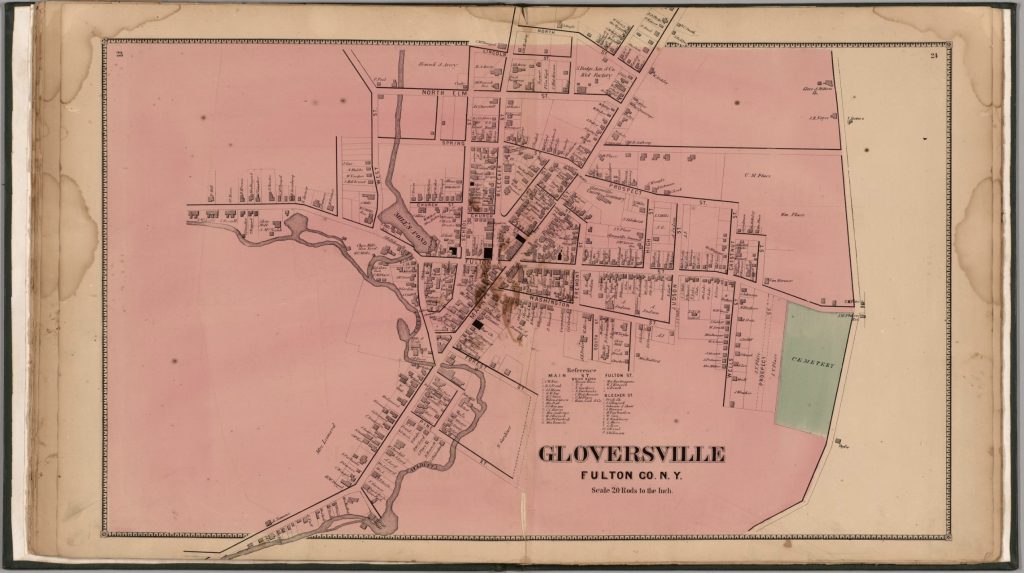

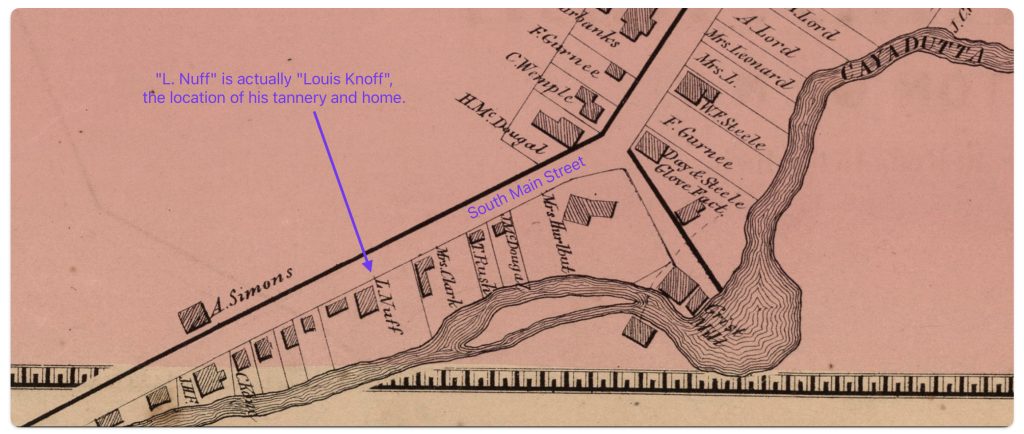

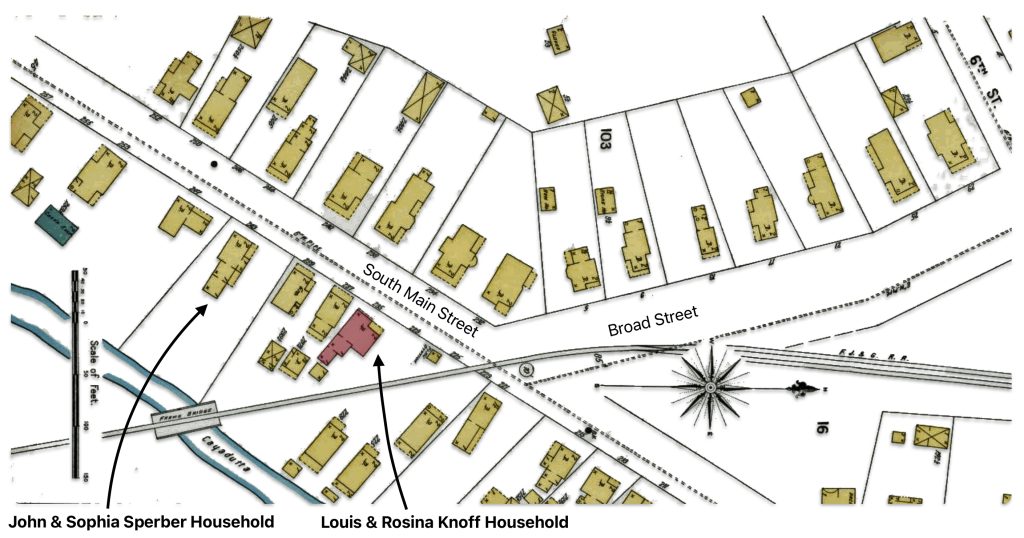

An 1868 map below (map two) provides an approximate location of Louis Knoff’s tannery on South Main Street, Gloversville, New York once he established his business in 1865. Louis Knoff’s tannery and residence is indicated In the lower left portion of the map where it appears to go outside the map boundary.

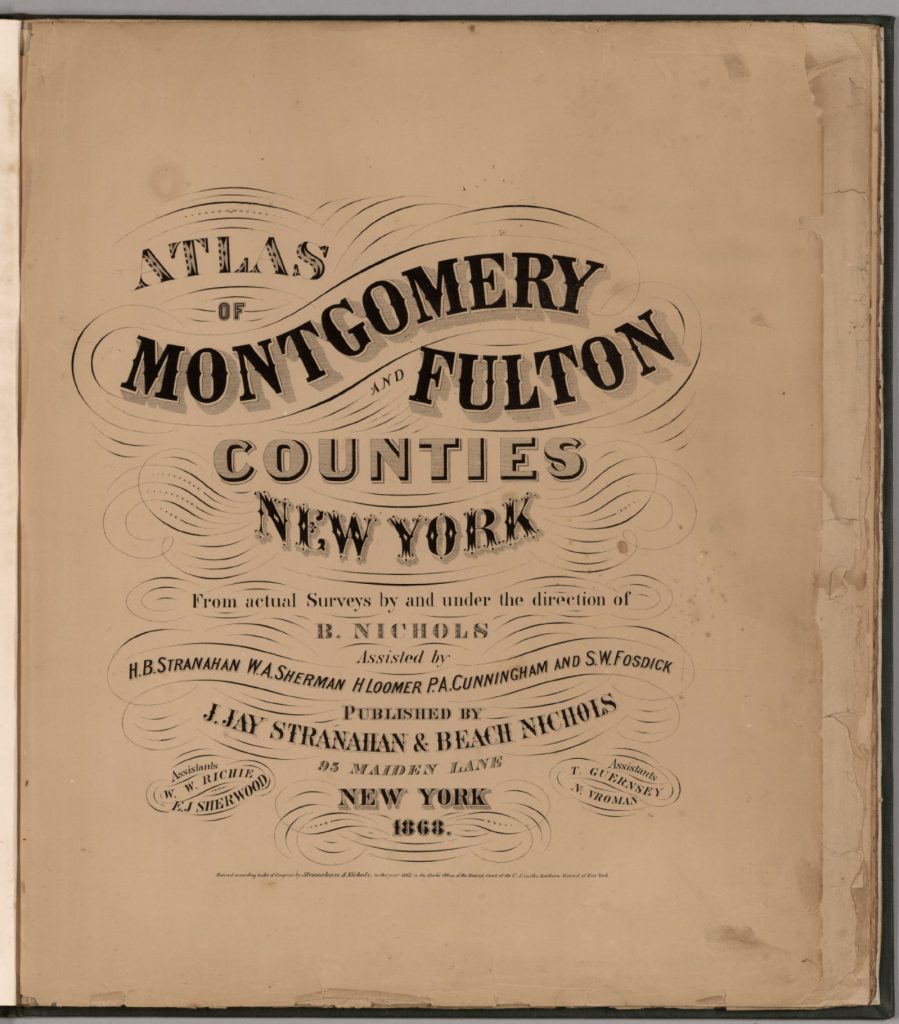

Map Two: The Nichols Stanahan Map of Gloversville 1868 [20]

As indicated in map two, Louis Knoff’s property is identified on the bottom of the map. Map three is a blown up portion of the South Main Street. Louis Knoff is identified in the map as “N.Nuff”. It is possible that one of Stranahan and Nichols staff obtained information from Knoff or a neighbor and phonetically documented his name when surveying South Main Street.

Map Three: Blow Up View of a Portion of the 1868 Map with Louis Knoff’s Property Location

The map is part of an atlas of Montgomery and Fulton Counties, New York. It was published in 1868 by J. Jay Stranahan and Beach Nichols. It contains maps of the towns and cities in the two counties based on actual surveys conducted under the direction of Nichols. The atlas is 28 leaves in length.. One of the distinctive qualities of the map is the high level of detail for the time period, including land owners, rivers, rail lines, streets and major businesses, making the map a valuable resource for genealogists and those researching family histories in Gloversville.

Are there Different Versions of the Stranahan & Nichols Map of Gloversville in 1868

The Stranahan & Nichols Map of Gloversville in 1868 (map two) was part of a local atlas of Fulton and Montgomery counties that also listed businesses and individuals on city maps.

The Stranahan & Nichols Map of Gloversville in 1868 is used in this and other stories to locate family relatives in the city of Gloversville in the 1860s.

In my research, I have found ‘three’ versions of the map of Gloversville, New York. Each are identified as ‘the 1868 atlas’. The three versions are largely the same with at the maximum eight notable differences.

These differences suggest that two of the versions of the atlas were actually published simultaneously or after the initial publication.

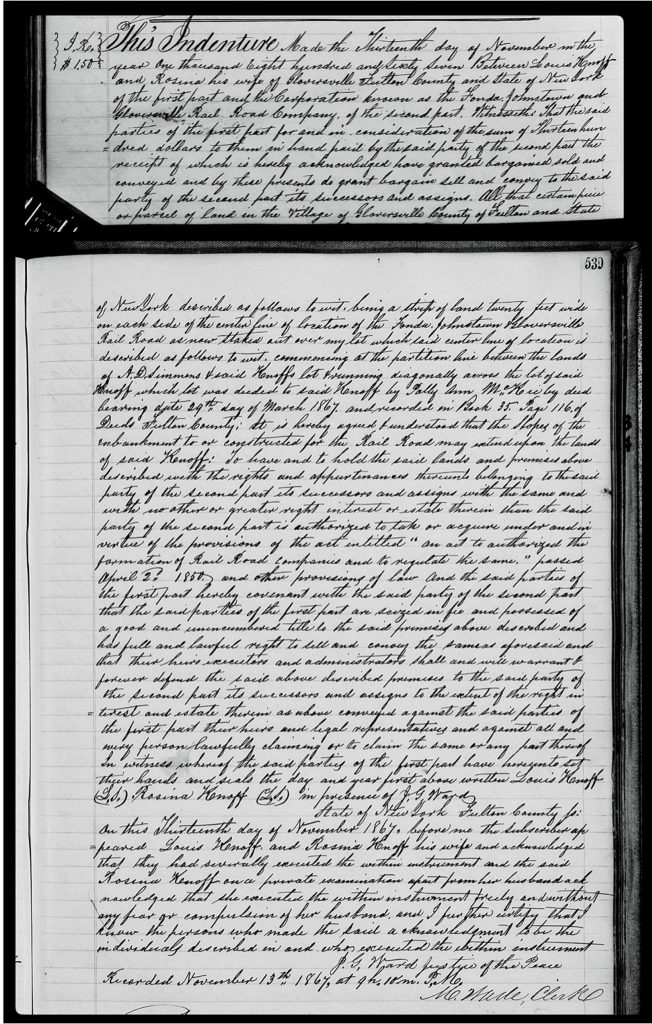

About eight months after the Louis Knoff purchased the property on South Main Street, the Fonda, Johnstown & Gloversville Railroad (FJ&G) company was purchasing portions of land for the construction of a rail line that connected from Fonda through Johnstown to Gloverstown. A November 13th 1867 land deed between Louis and his wife Rosina and the FJ&G company describes a portion of Knoff’s land that was conveyed to the Rail Company by law. [21] While the lawful imposition of slicing a band of land right through the Knoff’s property had a profound and substantial impact on the use of the land, Louis and Rosina received $1,300 dollars from the rail company. [22]

Land Deed between the Knoff Family and the FJ&G Rail Company

The deed described the acquired land by the railroad as “…being a strip of land twenty feet wide on each side of the center line of location of the Fonda, Johnstown Gloversville Rail Road as now staked out over my lot which said center line of location is described as follow to wit, commencing at the partition line between the lands of A.D. Simmons and said Knoffs lot running diagonally across the lot of said Knoff which lot has deeded to said Knoff by Polly Ann McKie by deed bearing date 29th day of March 1867 and recorded in Book 35 Page 116 of Deeds Fulton County; it is hereby agreed & understood that the Slopes of the embankment to or constructed for the Rail Road may extend upon the land of said Knoff … the said party of the second part is authorized to take or acquire under and in virtue of the provisions of the act entitled “an act to authorized the formation of Rail Companies and to regulate the same.” passed April 2nd 1850 and other provisions of law and the said parties of the first part hereby covenant with the said party of the second part.” (emphasis is mine)

The compensation for each of the properties taken by the railroad was determined through court action. In Fulton County, each property was described and a decision on what was to be taken by the railroad was rendered in a court case entitled “In the matter of the Petition of the Fonda, Johnstown and Gloversville railroad Company for the Appointment of Commissioners of Appraisal of Lands in the County of Fulton Lake and Others”. [23]

John and Sophie Sperber Move to South Main Street

A year after Louis and Rosina had purchased their property on South Main Street, John and Sophie Sperber followed their footsteps and also purchased property on South Main Street in 1868.

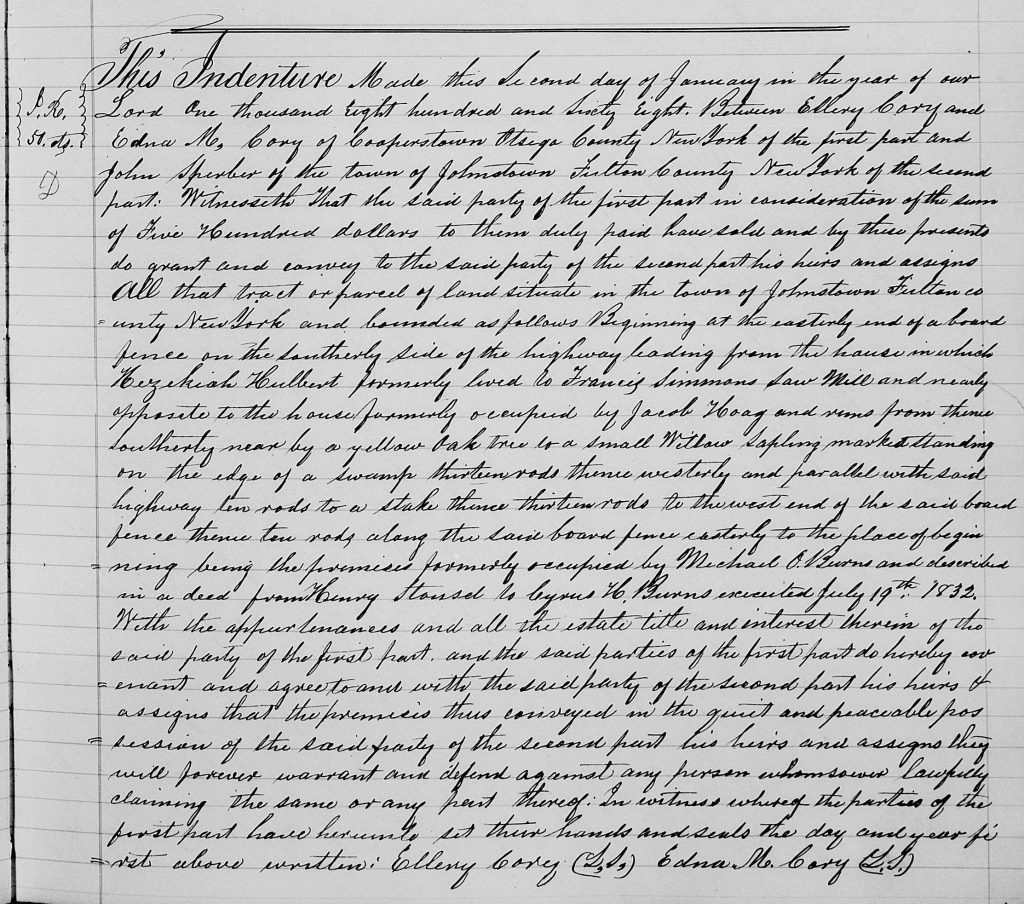

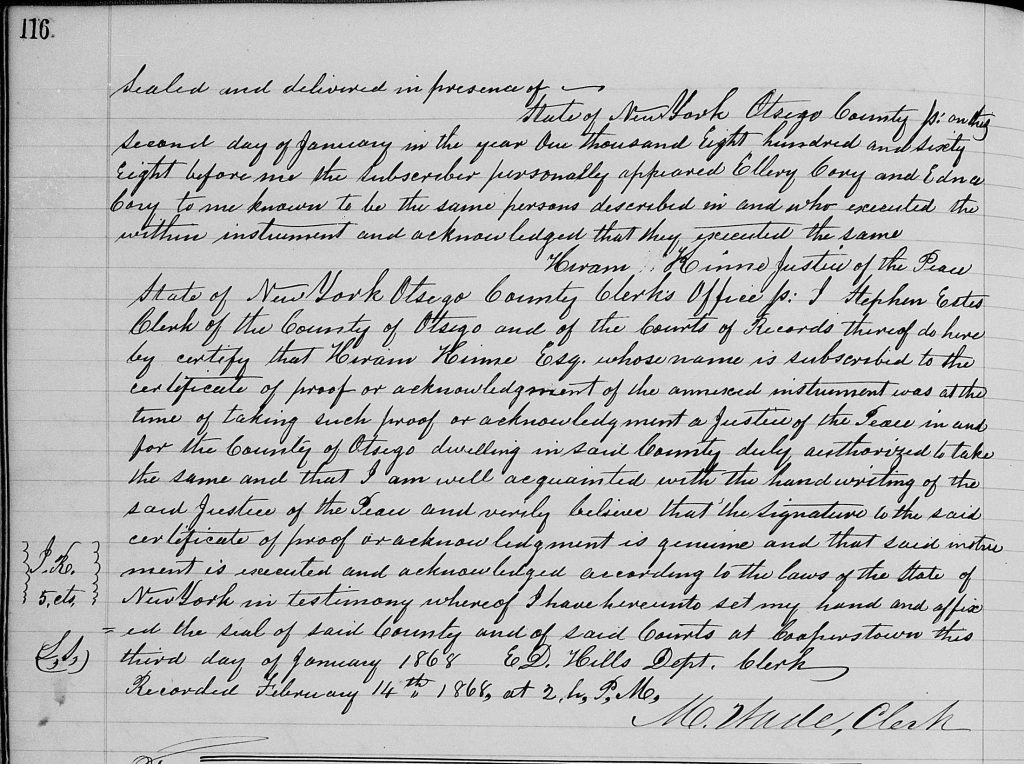

The recorded deed to the house indicates that John purchased the house from Ellery and Edna Cory, who were from Cooperstown, Otsego County, New York on January 2, 1868. John purchased the house for the sum of five hundred dollars. [24]

The Deed to John Sperber’s House 1868

Page One of the Deed

Source John Sperber, Grantee, Ellery R. Corey, Grantor, 14 Feb 1868, Entry Number 36, Page Number 115

Page Two of the Deed

Source: John Sperber, Grantee, Ellery R. Corey, Grantor, 14 Feb 1868, Entry Number 36, Page Number 116

The description of the property indicated:

“All that tract or parcel of land … bounded as follows Beginning at the eastern end of a board fence on the Southerly side of the highway leading from the house in which Hezekiah Hulbent formerly lived to Francis Simmons Saw Mill and nearly opposite to the house formerly occupied by Jack Hoag and runs from thence Southerly near by a Yellow oak tree to a small Willow Sapling marked standing on the edge of a swamp thirteen rods thence westerly and parallel with said highway ten rods to a stake thence thirteen rods to the west end of the said board fence thence ten rods along the said board fence easterly to the place of beginning being the premises formerly occupied by Michael O. Burns and described in a deed from Henry Stassel to Ivers H Burns executed July 19th 1832.”

Based on the deed’s description of the location of the property, it is difficult to determine exactly where the parcel of land is located. As indicated in a prior story it is believed that the property purchased by the Sperbers was next to the Knoff property.

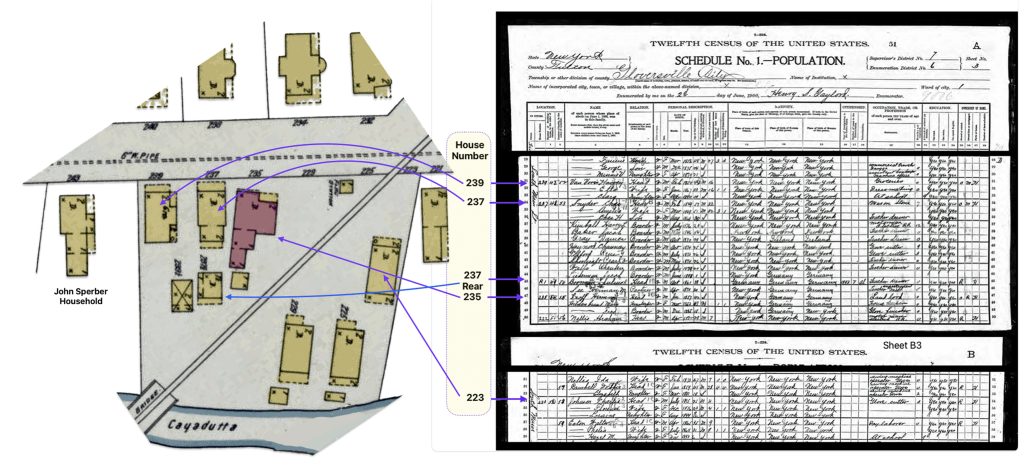

A 1902 map of Gloversville appears to confirm that the properties owned by the Sperbers and the Knoffs in the late 1860s are the same properties identified in a 1903 map of Gloversville. The 1903 map also reflects that the properties were contiguous. The Knoffs had a number of buildings on their property. The two households had two other households in between them. [25]

Map Four: Map 22 of Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from 1902 Gloversville [26]

Sisters as Neighbors on South Main Street in the 70s

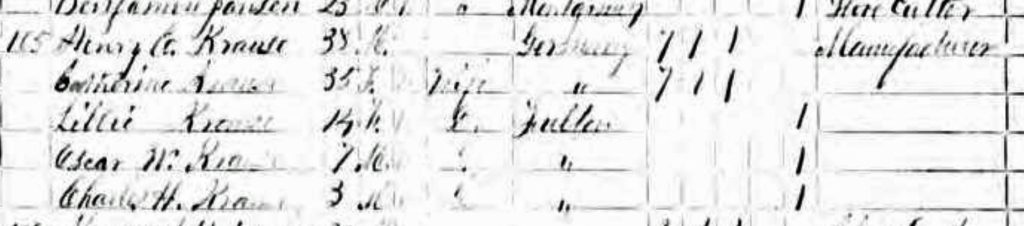

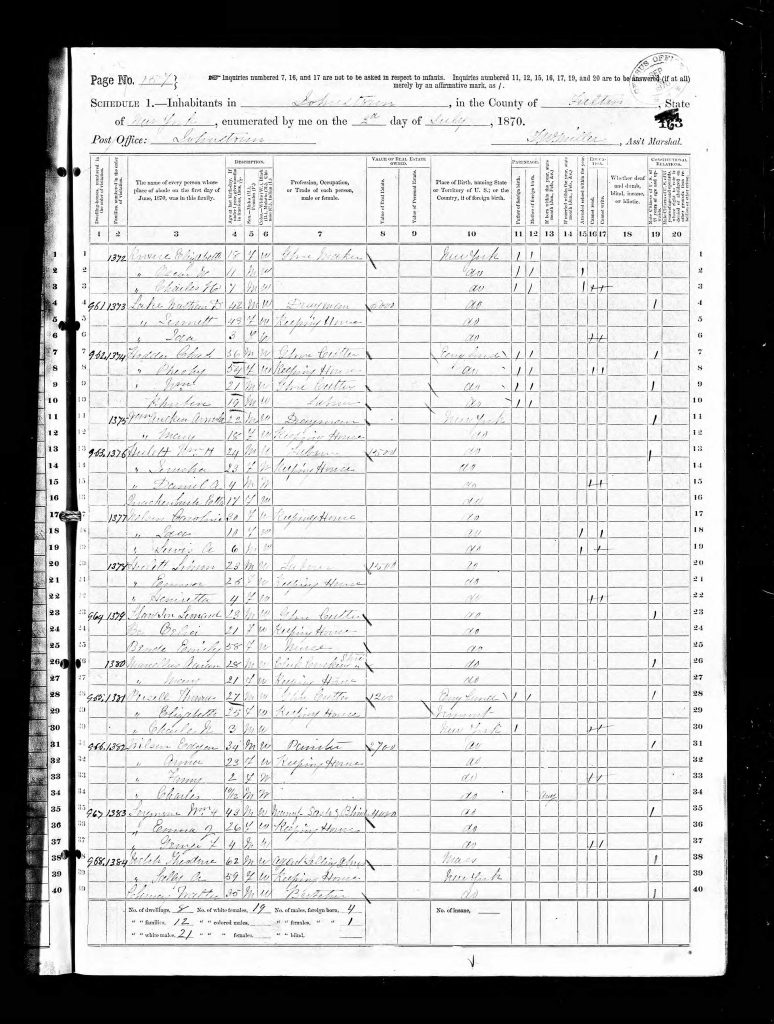

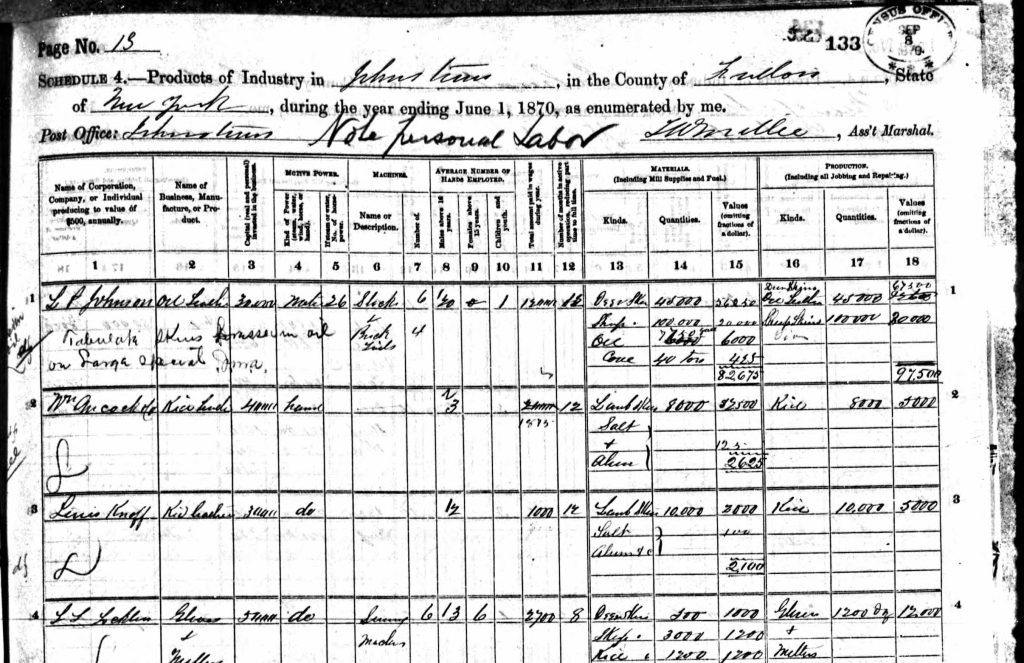

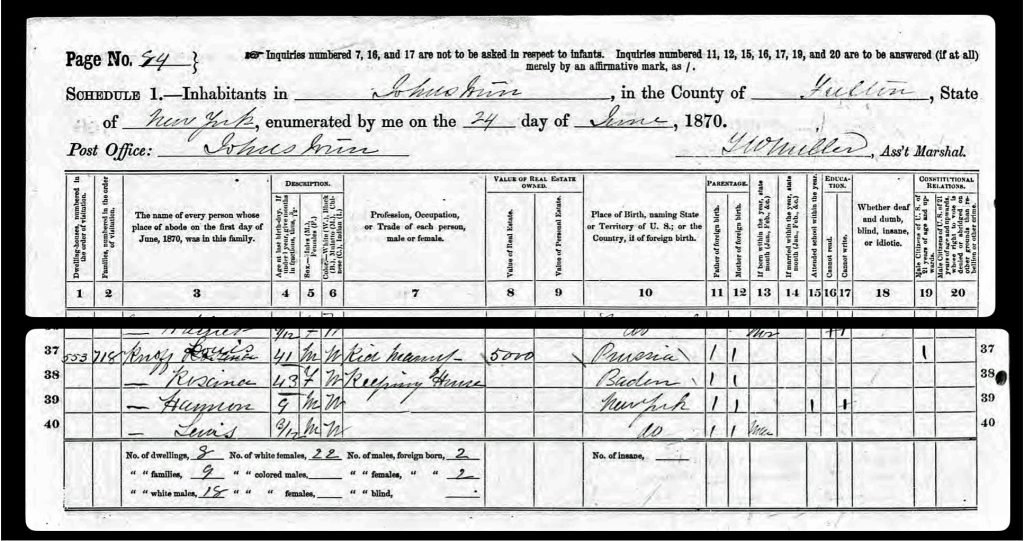

As noted in the 1870 U.S. Census (below), Louis Knoff is reported to be 41 years old. His occupation is listed as a “kid manufacturer” which refers to a type of leather. Kidskin or kid leather is a type of soft, thin leather that is traditionally used for high end gloves. Kidskin is leather made from the skin of young goats or “kids”. It is known for being ultra-soft, thin, lightweight yet durable. [27]

The census document indicates that Louis utilized lambskins, salt and alum as the major kinds of material used in his business. Kids skins were alum tanned. In tanning, alum acts as a preservative to prevent hide spoilage. It fixes tannins into the hide’s protein structure to make it stronger yet supple. [28]

“Alum tanning was devised for soft-finished leather… . A paste of egg yokes, flour , salt and alum was used to tan … kidskins… . It was a laborious and time consuming process in which the paste had to be worked into the skins in a series of operations that involved as many as 30 steps.” [29]

Census Document One: 1870 Schedule 4 – Non Population Schedule

The Schedule 4 of the Non-Population 1870 census captured information on Louis Knoff’s skin tanning business. Based on the information recorded by the enumerator, the business produced kid leather for mens and ladies gloves. The capital worth (real and personal) invested in the business was $30,000. It was a hand powered business. In addition to himself, he had two employees. He paid $1,000 in wages between the beginning of the year and up to June when the census was taken. Louis used 8,000 lamb skins worth $25,000 to produce 8,000 pairs of gloves worth $5,000.

His birthplace in the 1870 Federal population census is reported as Prussia. The family’s residence is reported to be worth. $5,000 dollars. Rosina was 43 and keeping house. Her birthplace is reported to be Baden, Germany. Herman, Louis’ first son, was 9 years old and he was in school. Louis Junior was born that year in March. The census was taken on June 24, 1870.

Census Document Two: 1870 U.S. Federal Census: The Knoff Family

Page 84, Lines 37 – 40

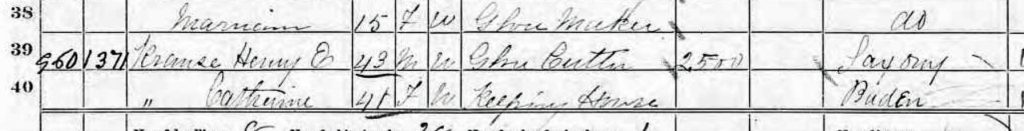

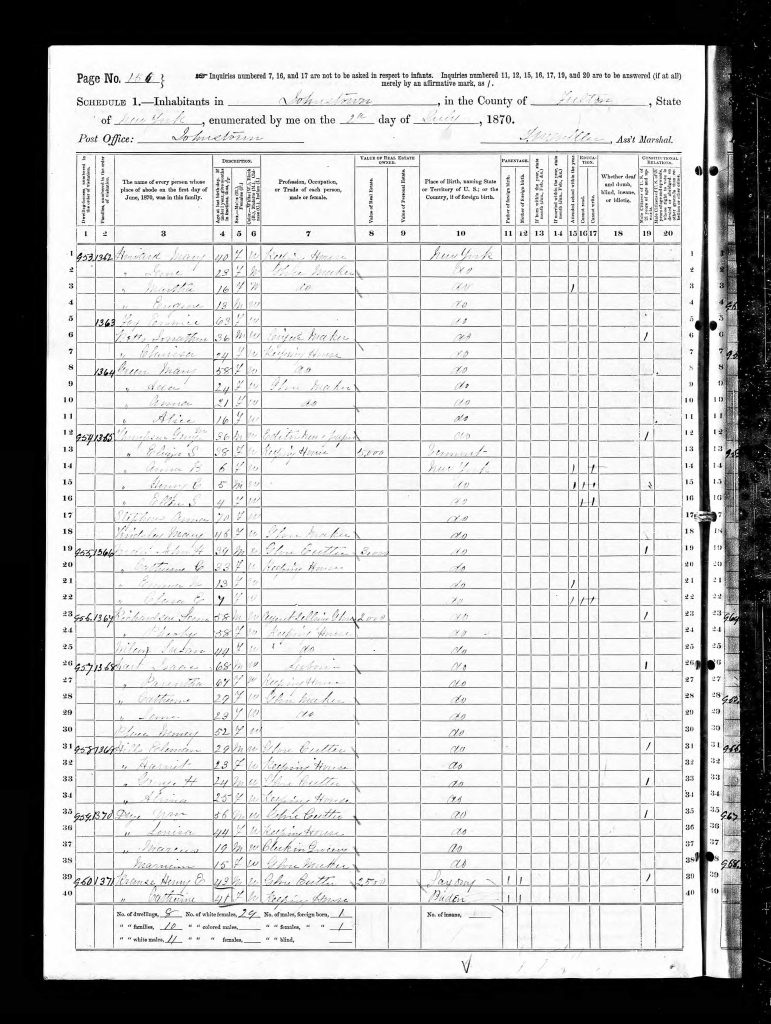

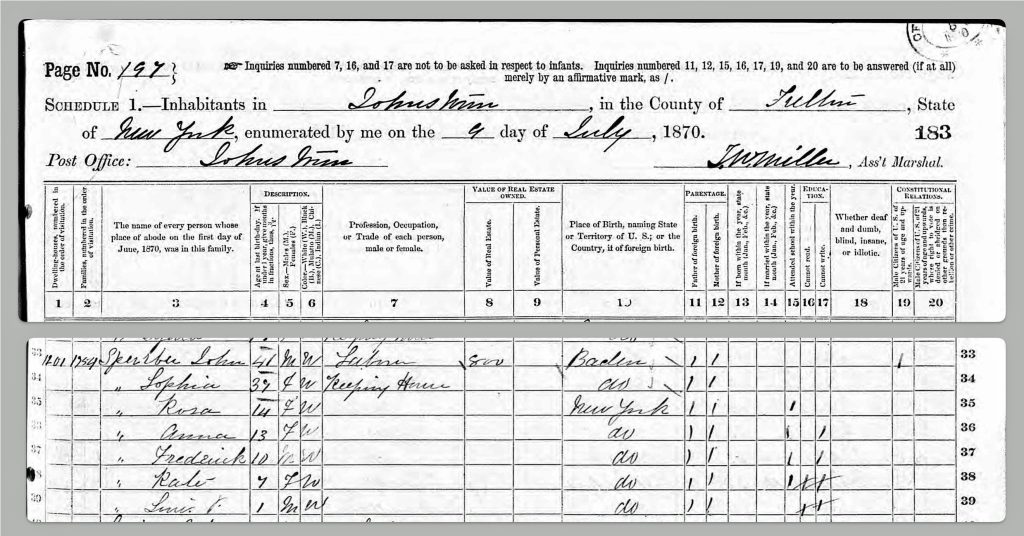

In 1870, the Sperber’s recently purchased house was valued at $800.00. The family now included John and Sophie and their five children. Rose and Anna were teenagers, 14 and 13 respectively. Frederick is 10 and Kate, who was born on January 1st, 1864, is 7. Their fifth child, Louis Sperber, was one year old. The census enumerator indicated that Rosa, Anna and Frederick were in school. He indicated that Anna and Frederick could not write and Kate could not read nor write. John’s occupation is listed as ‘laborer’.

Census Document Three: Sperber Family in the U.S. 1870 Census

Source: 1870 U.S. Federal census, New York State, Fulton County, Johnstown, Page 197, Lines 33 -39

While both families are found in the 1870 census, based on the census enumerators tabulations it is not apparent that the families lived next to each other. The Knoff family is found on page 84 and was the 553rd swelling canvassed. The Sperber family was found on page 197 and was the 1201st dwelling canvassed.

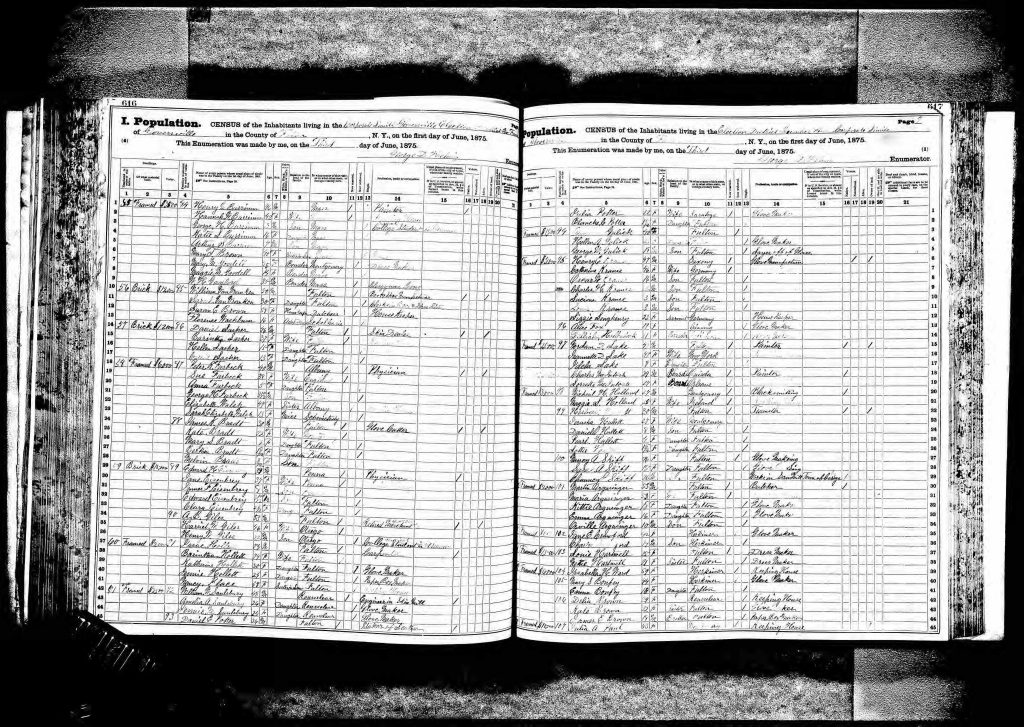

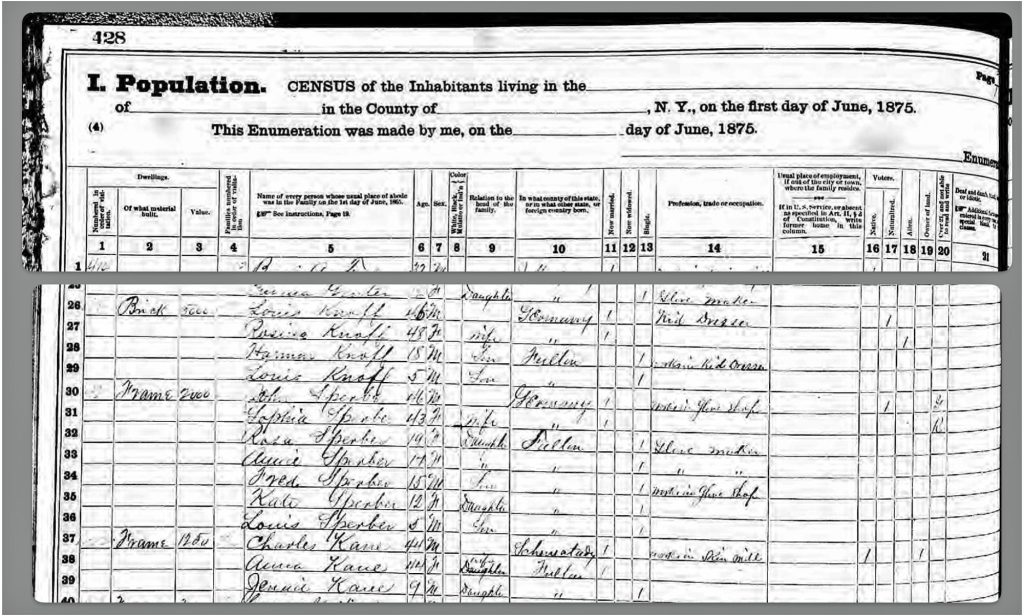

It is apparent in the 1875 census (below) that the Knoffs and Sperbers were ‘next door’ neighbors. The Knoff family lived in a brick house. John Sperber’s house was wooden frame house. Adjacent to or across the street from the Sperber’s household was the household of Charles Kane. The census enumerator canvassed the Kane household after he had canvassed the Sperber household.

Census Document Four: The Sperber and Knoff Families in 1875

The 1875 census reflects two related families that had similar demographic and occupational characteristics. Both families were similar in terms of their ‘station of life’. The parents were similar in age. They also experienced the same life experienced of immigrating to the United States from either the Duchy of Baden or Prussia.

While the Sperbers had a larger family, the two families had working teenagers and young sons. Each family was involved with the glove making business. The Knoffs were involved in the initial stages with skin dressing while the Sperbers were involved in the later stages of glove making.

Table One: 1875 New York Census: “Next Door” Neighbors – The Knoff & Sperber Families

| Family Member | Family Relation | Age | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|

| John Sperber | Father | 46 | Glove Finisher |

| Sophia Sperber | Mother | 43 | Keeping House |

| Rosa Sperber | Daughter | 19 | Glove Maker |

| Anna Sperber | Daughter | 17 | Glove Maker |

| Frederick Sperber | Son | 15 | Working in Glove Shop |

| Louis Sperber | Son | 5 | At home |

| Louis Knoff | Father | 46 | Kid Dresser |

| Rosina Knoff | Mother | 48 | Keeping House |

| Herman Knoff | Son | 18 | Works in Kid Shop |

| Louis Jr Knoff | Son | 5 | At home |

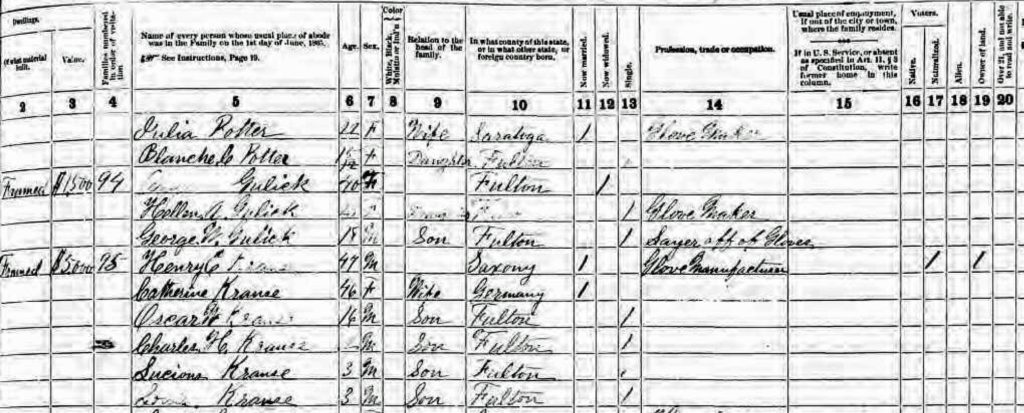

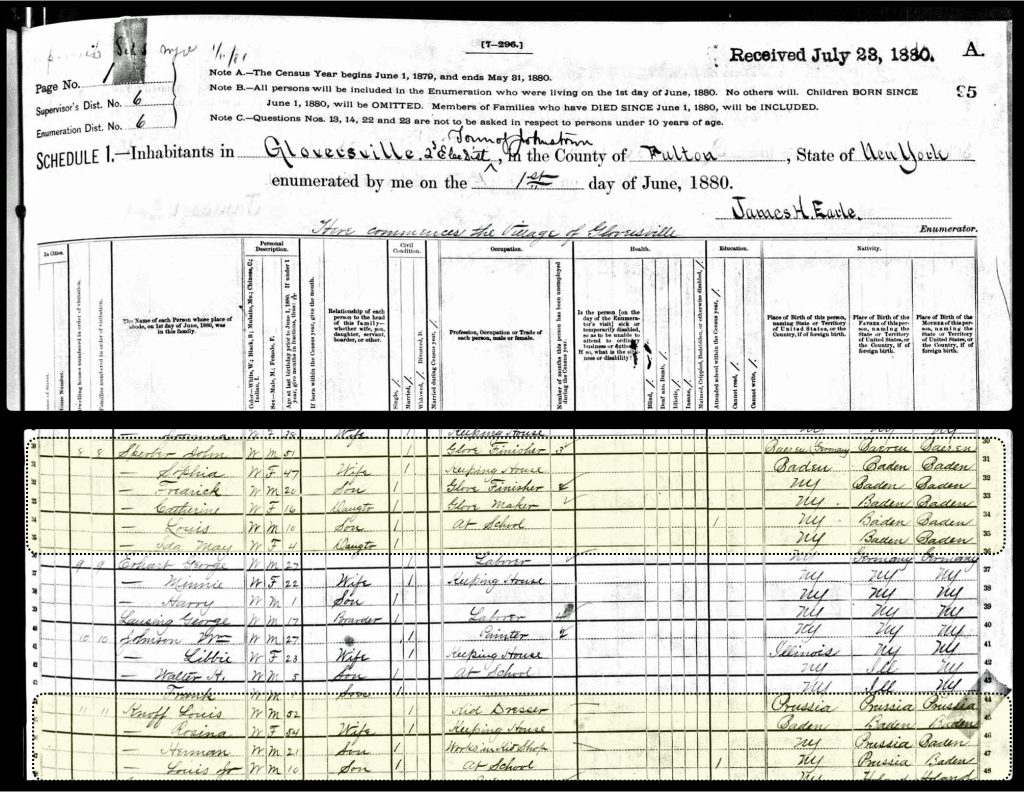

In five years, the family structure of both families changed slightly in 1880. The composition of their respective families were similar. They each had young adult sons living at home and working and young sons in school.

Census Document Five: 1880 U.S. Federal Census: “Next Door” Neighbors – The Knoff & Sperber Families

John Sperber was probably a ‘glove finisher’ at the Littauer Glove factory. His brother-in-law, Louis Knoff, owned a leather tannery with his son was working for his father. Louis indicated his occupation was a ‘Kid Dresser”. Both wives, the Fliegel sisters, were “keeping house”.

Table Two: Two Related “Next Door Neighbor” Families in Gloversville 1880

| Family Member | Family Relation | Age | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|

| John Sperber | Father | 51 | Glove Finisher |

| Sophia Sperber | Mother | 47 | Keeping House |

| Frederick Sperber | Son | 20 | Glove Finisher |

| Catherine Sperber | Daughter | 16 | Glove Maker |

| Louis Sperber | Son | 10 | At School |

| Ida Sperber | Daughter | 4 | – – |

| Louis Knoff | Father | 52 | Kid Dresser |

| Rosa Knoff | Mother | 54 | Keeping House |

| Herman Knoff | Son | 21 | Works in Kid Shop |

| Louis Jr Knoff | Son | 10 | At School |

Knoff Families in the 1890s

We do not have access of census material to glean a snapshot of the composition of the Sperber and Knoffs’ households between 1885 and 1900. However, city directories provide clues as to where family members possibly resided and what were their stated occupations. Comparing family member information from the directories can provide a basis to determine the locations of family members within the city. [30]

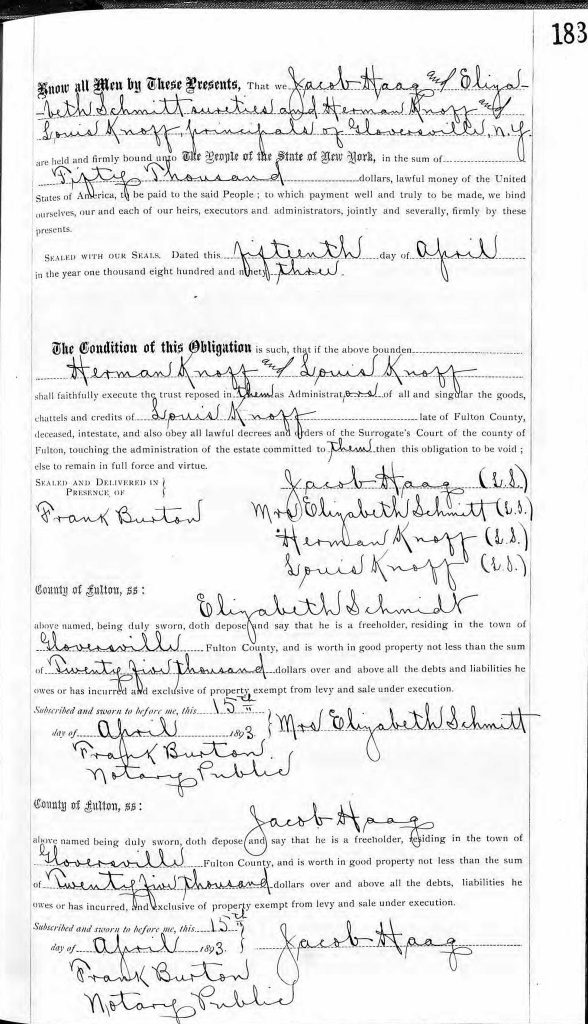

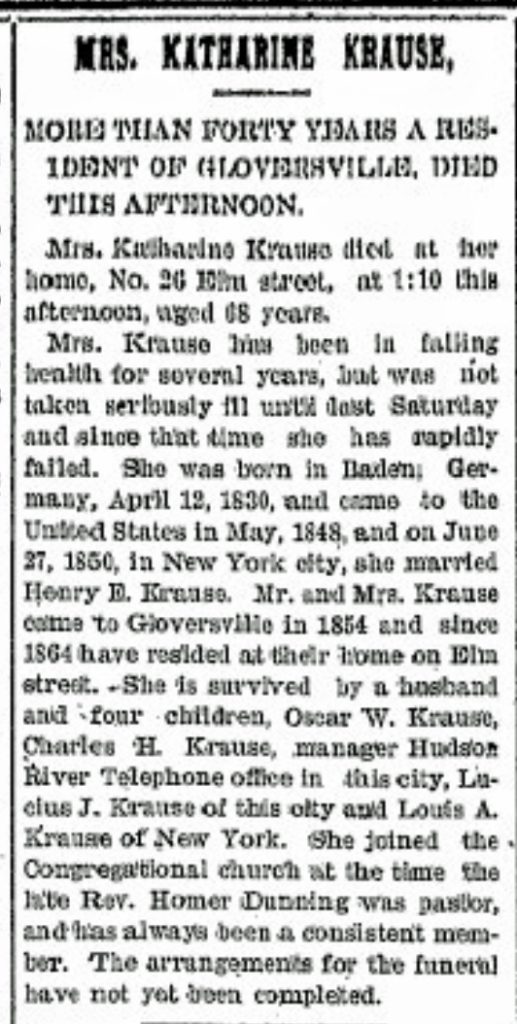

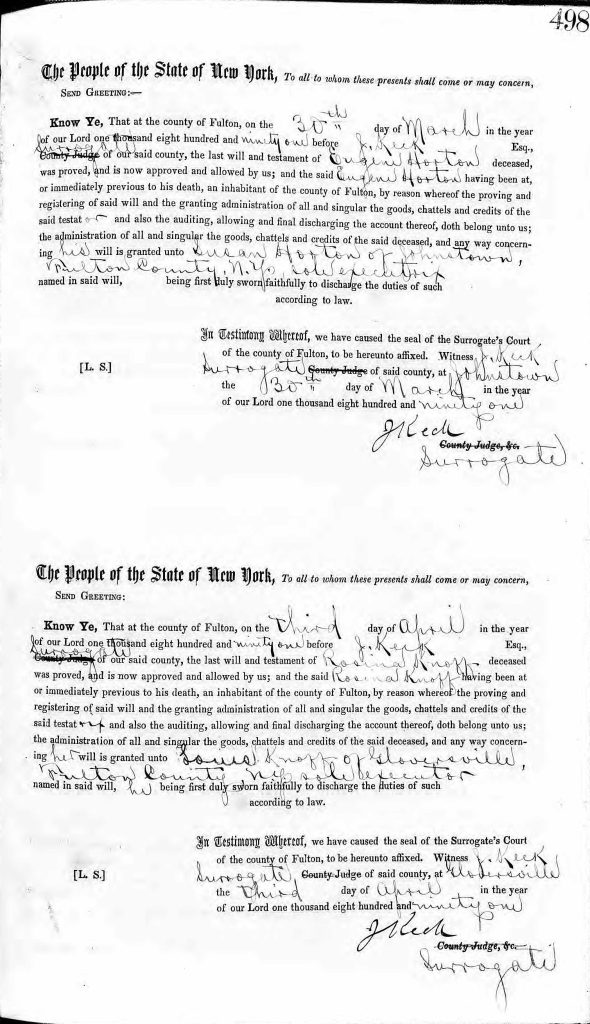

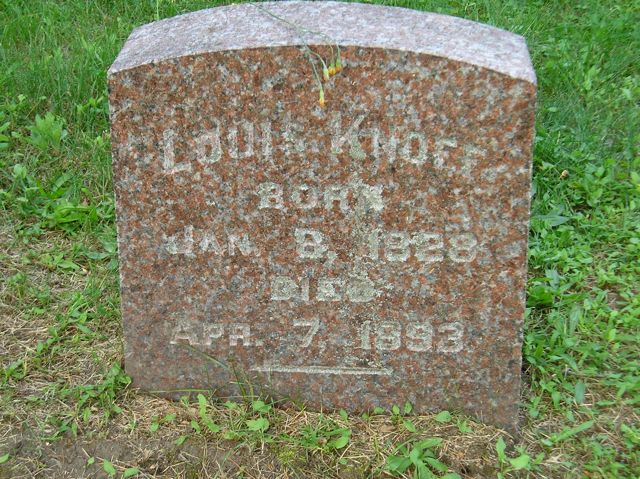

The 1890s was a decade of change for the two families of South Main Street. during the 1890’s, three of the four parents passed away and the adult children chartered new courses in their adult lives. Both parents in the Knoff family passed away in the early 1890s. Rosina passed away on March 22nd, 1891 at the age of 64. [31] Louis passed away two years later on April 7th, 1893. Louis was 65. [32] His business continued to be managed by his estate and had less than 10 employees.

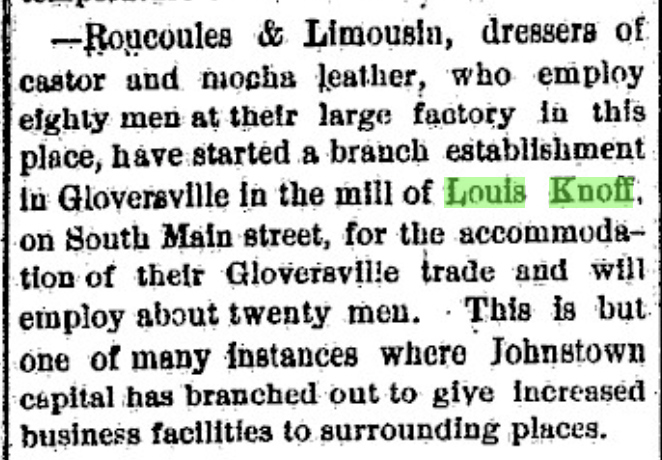

Louis Knoff’s tanning mill business was prosperous in the late 1880s and early 90s. A year before his death, the following newspaper article indicated his successful collaborative efforts with a leather tanning business in neighboring Johnstown.

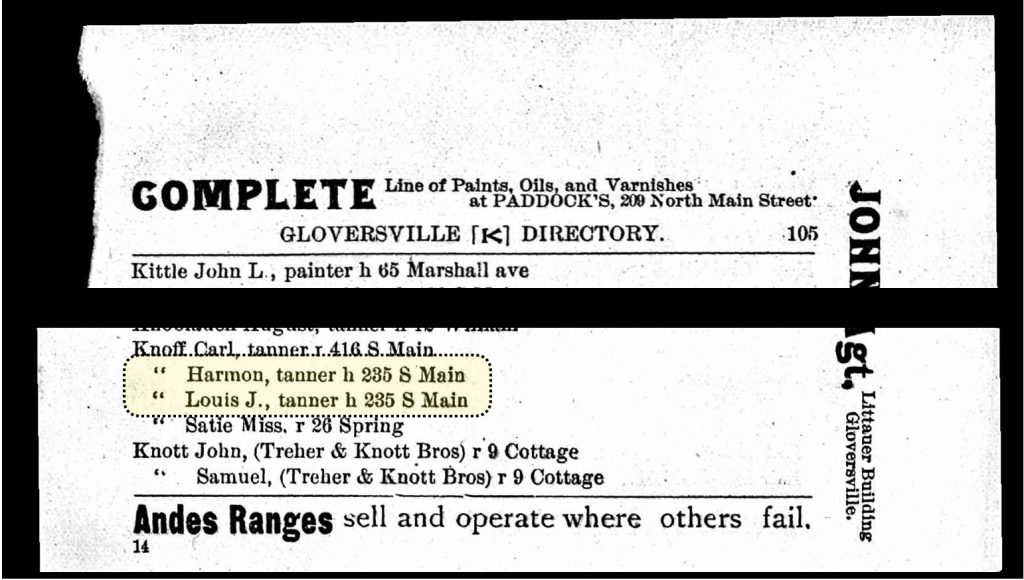

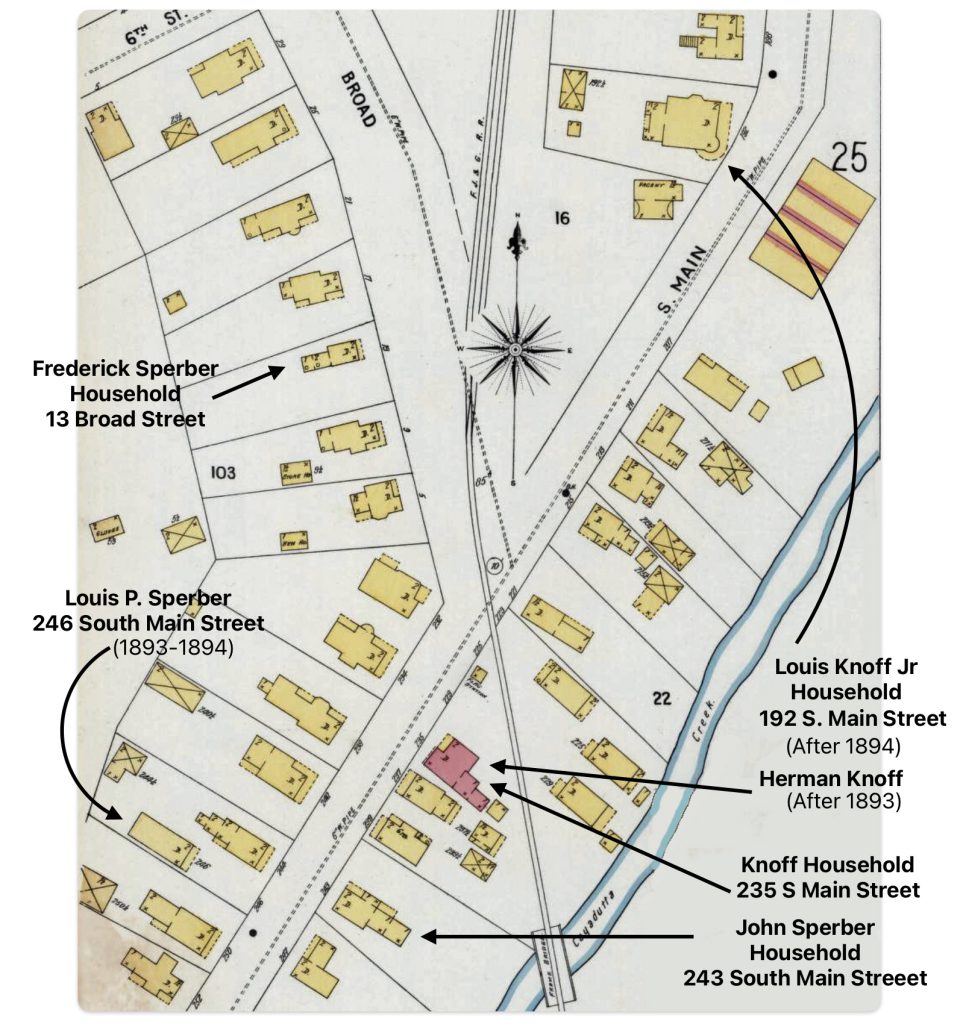

The two Knoff brothers Herman and Louis Jr. were working for their father in the year that Louis senior passed away, as reflected in their 1894 listing in the Gloversville city directory below, they continued with the business with their homes listed as 235 South Main Street. There is also a Karl Knoff listed as a tanner in the 1893 directory. It is not known if he is related to Herman or Louis. [33]

Gloversville City Directory 1894

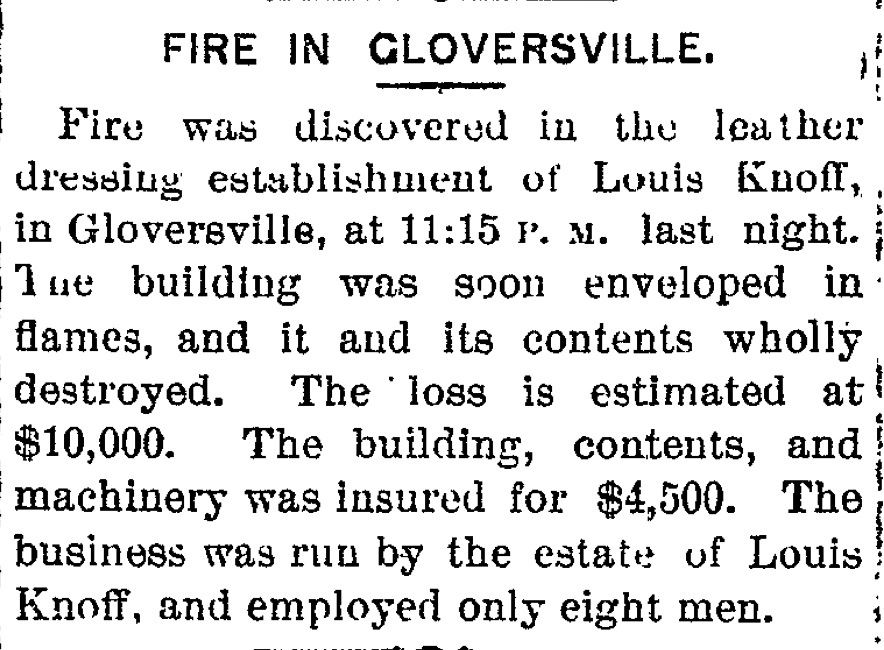

What would appear to be more than coincidence, three months after Louis Knoff’s death on April 11th, a fire destroyed the leather tanning building on July 7th. The building and its contents were valued at $10,000 and was insured at $4,000.

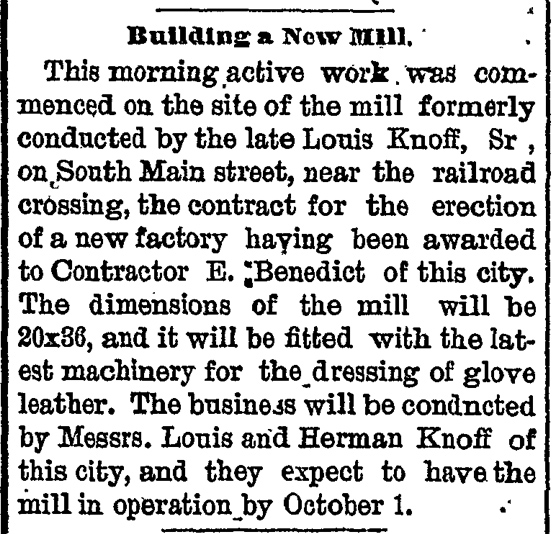

Two years after the fire, the Knoff brothers established plans to rebuild the leather tanning business with a new building and “the latest machinery for the dressing of glove leather”.

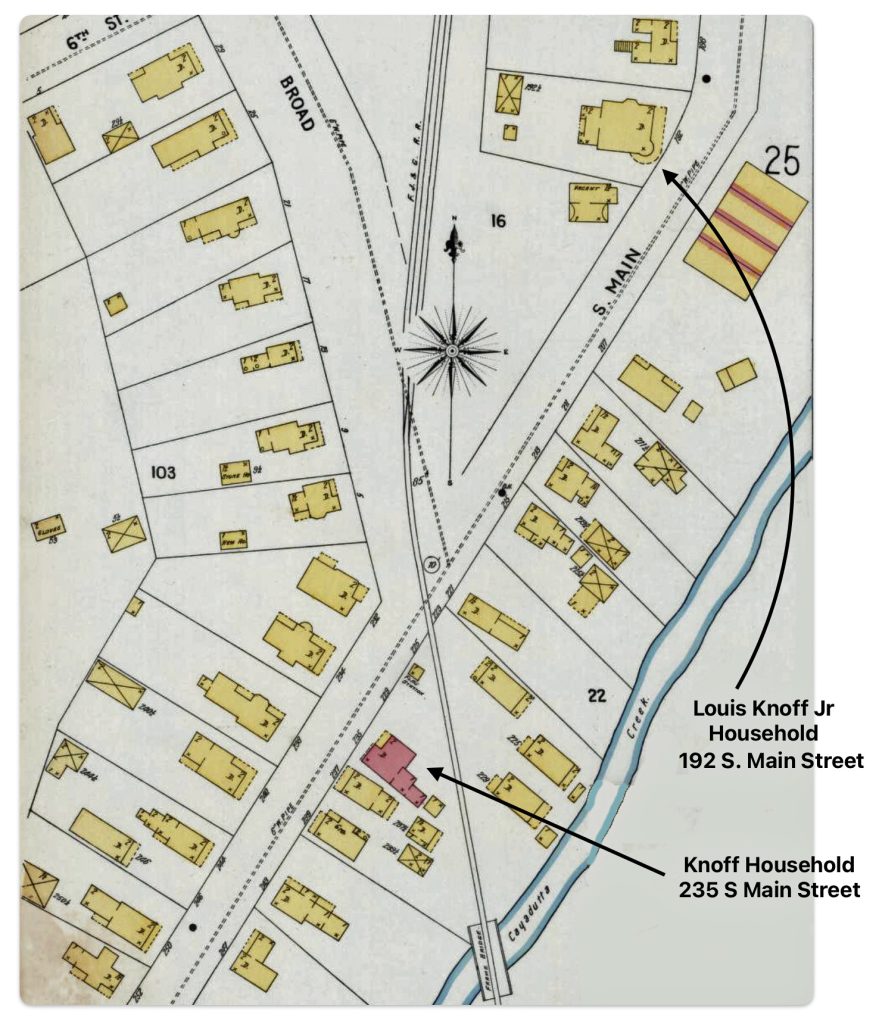

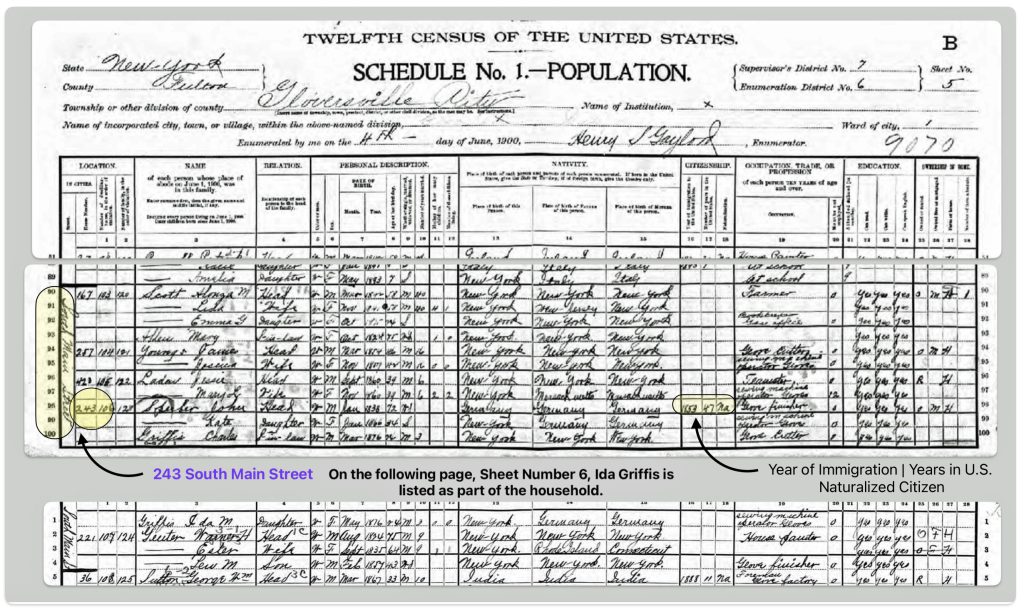

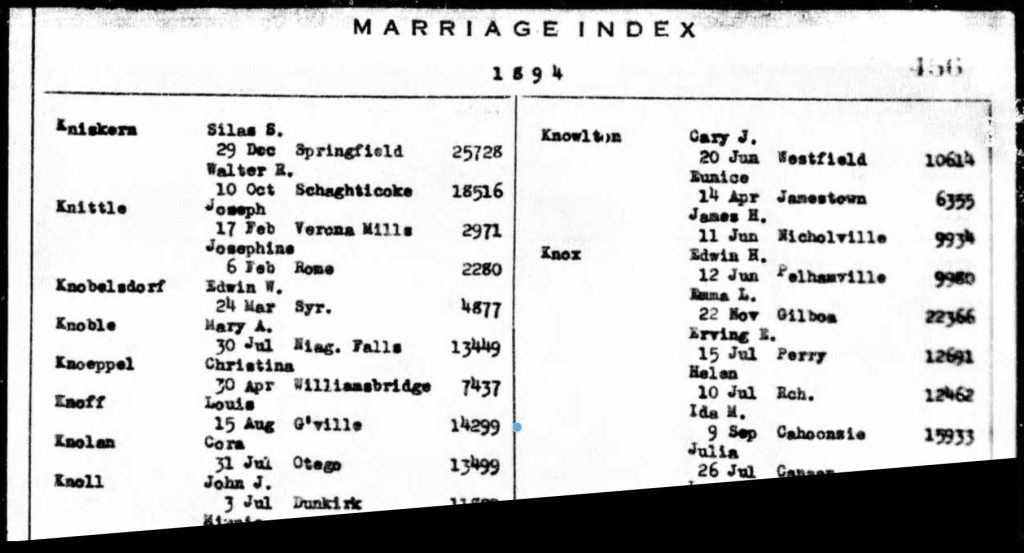

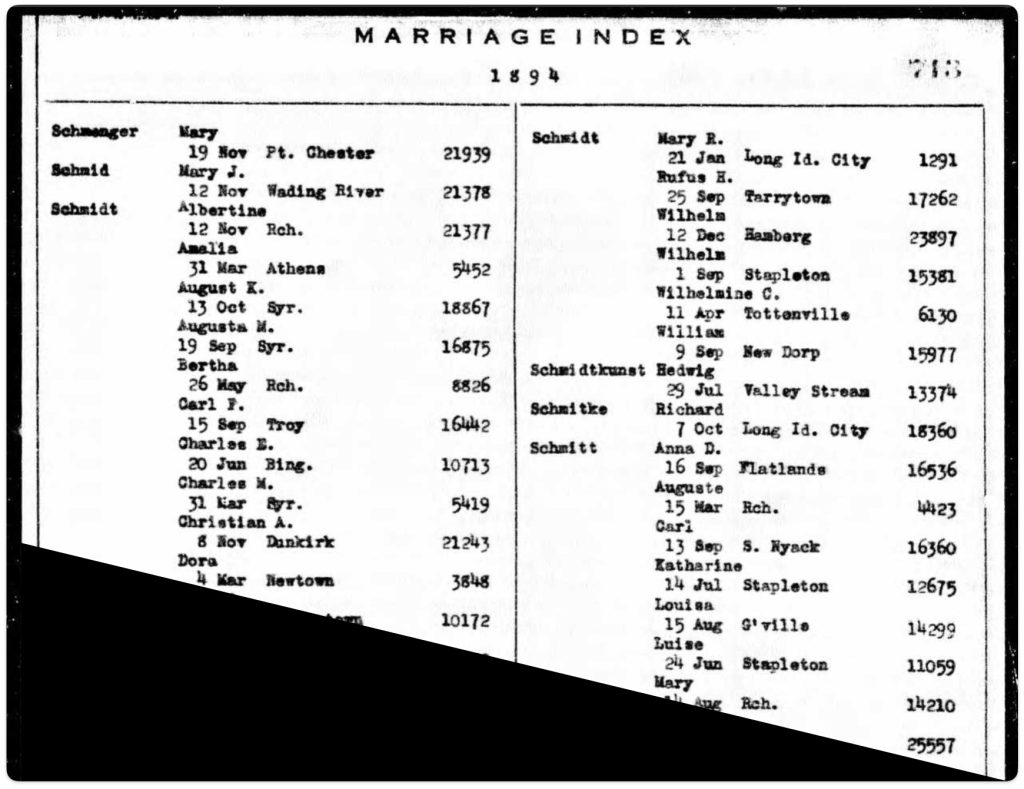

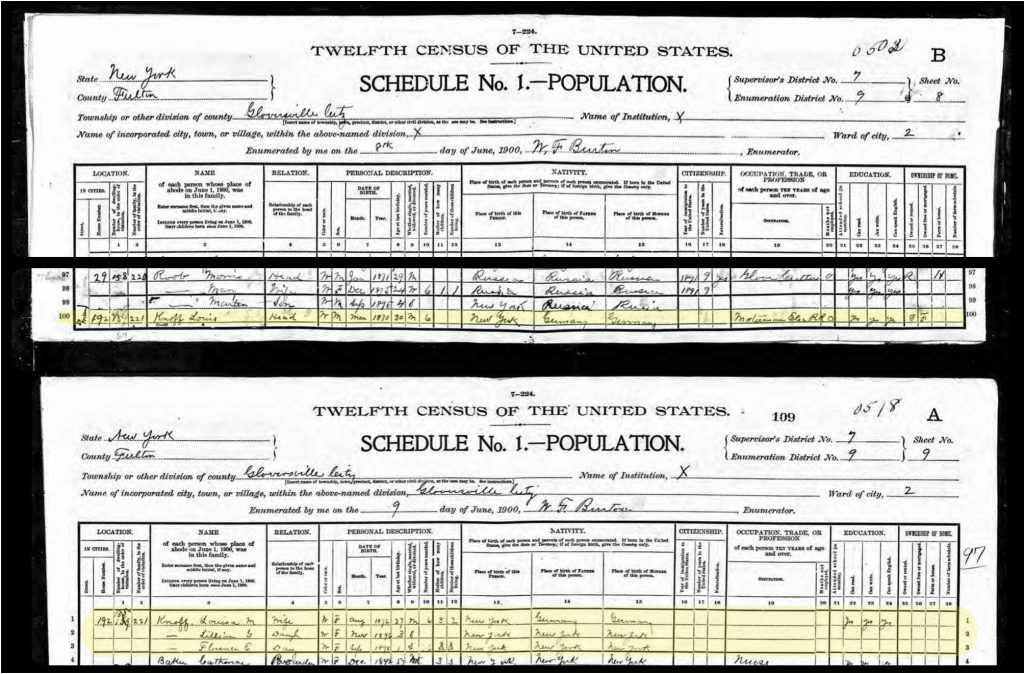

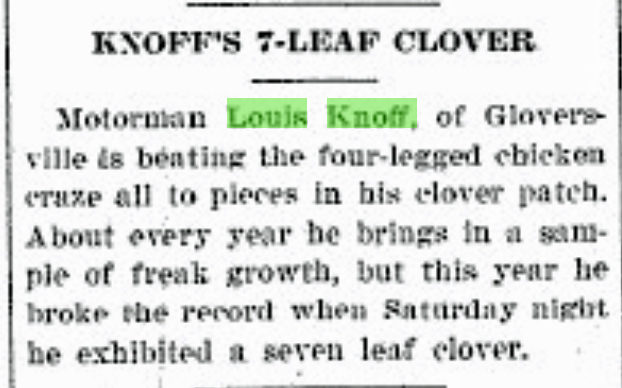

Louis Knoff Junior married a year after his father’s death on August 15th, 1894 at the age of 24. [34] He married Louisa Schmidtt who was reportedly 19 at the time their marriage. [35] He left the South Main Street Neighborhood and lived a few houses north on Main Street with his wife at 192 South Main Street. [36] As indicated in the 1900 population census, Louis Jr left the tanning business and became a motorman on the electric rail in Gloversville. [37]

Map Five: Household Location of Louis Knoff Jr – 192 South Main Street 1900

Louis and Louisa quickly started a family. In 1896, they had their first child, Lillian Rosina Knoff. Sadly, she only lived for four days. In 1896. Their second daughter, Lillian Gertrude, was born and in 1898 and their third daughter Marian Augusta was born. Their fourth and final child, Marian Augusta, was born in 1906. [38]

At the end of the century, Herman Knoff is still living in his father’s home. His occupation is listed as ‘landlord’. A ‘housekeeper’ Mary Hildenbrand was living in the household along with her son Fred. It appeared that Mary Hildebrand was Herman’s wife. No records of the marraige can be found. Mary’s maiden name was Bender and her first husband was Frederick Hildenbrand.

The other properties on the lot are largely populated by lodgers who are working as tanners.

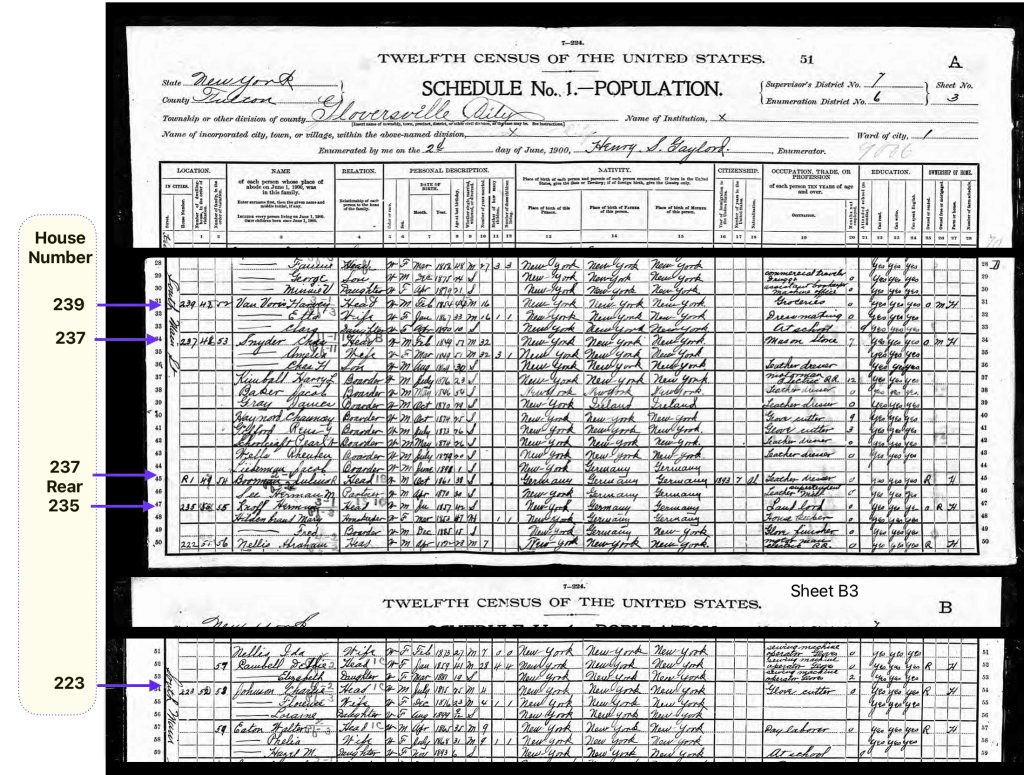

Census Document Six: 1900 U.S. Federal Census – Knoff Properties

A correlation of the 1900 census data associated with each of the addresses of households on South Main Street with the 1902 Sanborn map that depicts the physical buildings at those street addresses provides a picture of the Knoff properties at the turn of the century.

Knoff Properties on South Main Street as Documented in a 1902 Sanborn Map of Gloversville and 1900 Population Census Click for Larger Presentation

The Sperber Family in the 1890s

Sophia Sperber and her family continued to be neighbors to her sister Rosina’s family after she passed away in 1891. During the 1890s, the household size of Sophia and John’s family reduced to their daughters Kate and Ida.

Their eldest son Frederick married in September 1878. Frederick Sperber’s family was living on Broad Street since 1886. Based on Fulton county land deed documents, Frederick and Ella purchased property on Broad Street in Ella Sperber’s name from Andrew D. & Mary C. Simmons. [39]

During the 1890s, Frederick, who was the Chief of Police for Gloversville, and his wife Ella had a family of teenagers and toddlers. By the end of the decade Rose, their oldest was 19 years old. Rose was living with her parents and was a pocket book maker. Arthur and Frederick John Sperber were teenagers. Arthur was a glove finisher and his brother was still in school. [40]

Louis P. Sperber, John and Sophia’s second son, resided lived with his father and mother. During his first two years of marriage (1893 – 1894), he and his wife Anna lived across the street from his parents at 246 South Main Street. The house was a wooden frame one room house with a porch.

Sophia passed away on March 17, 1897. [41] Eights days after her passing, Sophia’s youngest daughter, Ida Sperber, married Charles Griffis on March 25, 1987 in Gloversville. [42]

In 1900, John Sperber was around 72 years old, widowed; and living other family members at 243 South Main Street, Gloversville, New York. The household consisted of John along with his daughter Kate and his youngest daughter Ida and her husband Charles Griffis.

Census Document Seven: John Sperber Household in 1900

While each family witnessed many changes in the 1890s, the two families continued to have family members in the general area of South Main Street.

Map Six: Sperber and Knoff Families in the South Main Street Area of Gloversville

The Legacies of the Two Sisters: Different Generations But Still Close Together

At the age of 75, John Sperber was still listed in the Gloversville Directory as a glover, living in the same house he raised his family since the late 1860s. [43] His nephew Herman Knoff was living two doors down in his parent’s house.. His other Nephew Louis Knoff was up a few blocks on South Main Street with his family. His son Frederick was around the corner on Broad Street.

John was the last surviving parent who moved their families to the southern border of the city of Gloversville on South Main Street. John Wolfgang Sperber passed away on January 27th, 1905, twenty-five days after his 77th birthday. Harold Griffis was born in John’s house on South Main Street. He was one year and a half years old when his grandfather passed away.

Members of the second and third generation of the families continued to live in the neighborhood they grew up in. The strong tradition of intergenerational families and interdependence meant that most people in the late 1800s lived very close to parents, adult children, and other relatives. Family togetherness was an economic and social necessity. While nuclear families became more prevalent in cities, they still often lived near extended kin.

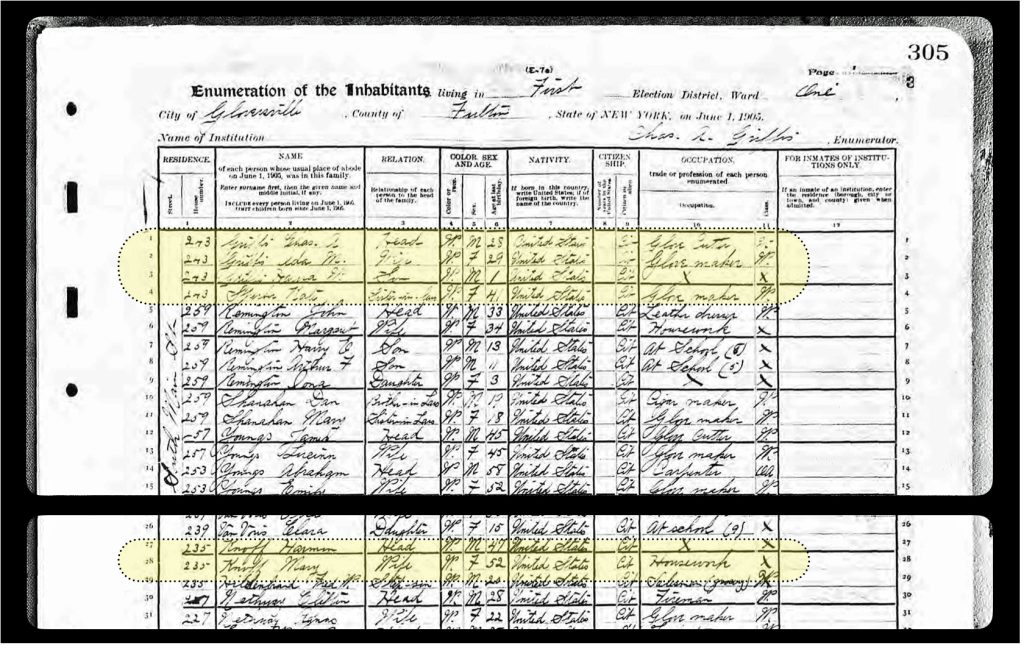

Census Document Eight: 1905 – The Griffis/Sperber Household and the Knoff Household

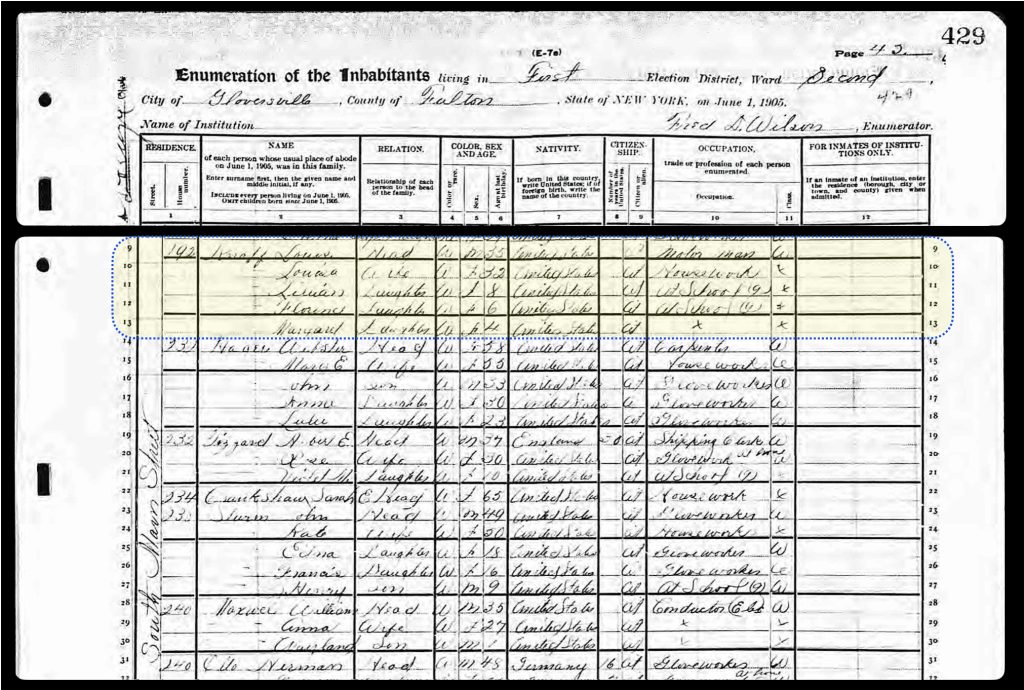

Census Document Nine: 1905 – Louis Knoff on South Main Street

Sources

Feature Banner of the story is part of a Sanborn map 22 of a series of maps of Gloversville in 1902 that shows the location of the Sperber and Knoff households.

The Sanborn Map Company was a prominent American publisher of detailed fire insurance maps from 1867 to the late 20th century. The maps provided detailed information about the size, shape, construction materials and function of buildings in urban areas. They also included details like street names and widths, property boundaries, building use, and the location of water mains, fire alarms and fire hydrants and the exact street numbers of buildings.

Founded in 1867 by Daniel Alfred Sanborn, the company created richly detailed maps of approximately 12,000 cities and towns across the United States, Canada, and Mexico.Sanborn maps were originally designed to assist fire insurance companies in assessing the risk associated with insuring a particular property.

The Sanborn Company sent out legions, or to use the collective group term of surveyors, ‘chains’, of surveyors to map building footprints and collect urban data. At its peak in the 1920s, the company employed about 700 people, including 300 field surveyors and 400 cartographers, printers and managers. Sanborn held a virtual monopoly over fire insurance maps for much of the 20th century after acquiring its last major competitor in 1916.

While originally created for insurance purposes, Sanborn maps have become invaluable historic resources. They allow researchers to trace urban development and changes over time, providing unparalleled detail about the built environment of American cities from the late 1800s through the mid-1900s. The Library of Congress holds the largest collection of Sanborn maps, which are widely used by historians, architects, genealogists and others.

Sanborn Maps, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 1 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanborn_maps

Sanborn Maps, About This Collection, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/sanborn-maps/about-this-collection/

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Gloversville, Fulton County, New York., Sanborn Map Company, Published Oct 1902, Digital Id http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3804gm.g3804gm_g059511902

Coons, Alana, Let’s Talk about Sanborn Maps, University Heights Historical Society, https://www.uhhs-uhcdc.org/blog/lets-talk-sanborn-maps

Introduction to the Collection, Sanborn Maps Collection, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/sanborn-maps/articles-and-essays/introduction-to-the-collection/

Interpreting Sanborn Maps, Fire Insurance Maps at the Library of Congress: A Resource Guide, Library of Congress, https://guides.loc.gov/fire-insurance-maps/sanborn-interpreting

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map: How to Read Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, The Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia , https://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/collections/maps/sanborn/web/details.html

How to: Use Sanborn Maps City Archives & Special Collections, New Orleans Public Library, https://nolacityarchives.org/2024/01/08/how-to-use-sanborn-maps/

[1] Hurst, Kelly, More than half of Americans live within an hour of extended family, May 18, 2022, Pew Research Center, https://pewrsr.ch/3yKn2ms

[2] See the stories of their journey: “The Fliegel Family: Their Journey to America” and “The Sperber & Fliegel Families in America: Catherine Fliegel the First to Arrive“.)

[3] See an eight part series of stories on his journey to America for specific facts about John and Sophia Sperber.

Marriage document of John Wolfgang Sperber and Sophia Fliegel, Source: Original Document from Family Collection, Click for access to document

[4] John and Sophia Sperber Household, 1860 U.S. Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Johnstown, Page 183 Lines 23 -28

Source U.S. Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Johnstown, Page 183 Lines 23 -28

[5] 1865 New York State Census, Fulton County, Johnstown, Page 387, Lines 33 – 38

[6] Rosina Flügel, Taufe (Baptism), Birth Date 04 Mär 1825, 03 Apr 1825, Ittlingen, PreuBen, Baden, Father Christoph Flügel, Juliaa Flügel, Pages 130-131; Birth and baptism records in Baden and Hesse Germany, Lutheran Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials, 1502-1985, Ancestry.com. Germany, Select Births and Baptisms, 1558-1898 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.Original data: Germany, Births and Baptisms, 1558-1898. Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 2013.

Reynolds, Cuyler, ed., Hudson-Mohawk Genealogical and Family Memoirs, Vol. III , Pages 1353-1354 ,https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101030753469&seq=7

[7] New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957, Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Microfilm Publication T715, 8892 rolls. NAI: 300346. https://griffis.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/NYM237_150-0080.jpg

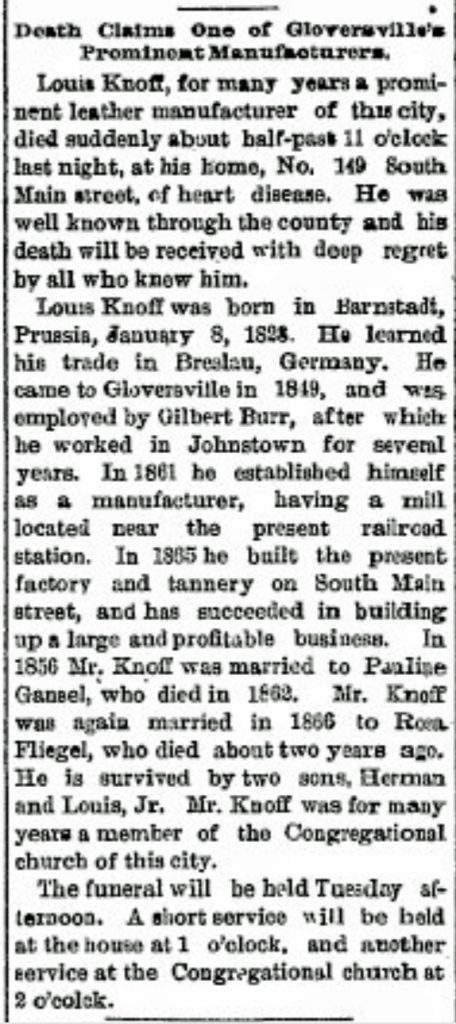

[8] The obituary for Louis Knoff provides a wealth of biographical information on Louis and on his marriage to Rosa Fliegel. The obituary indicates:

- He passed away, primarily due to heart disease, on April 7th, 1893 at 11:30 pm;

- At the time f his death, he lived at 149 South Main Street;

- He was born in Barnstadt, Prussia on January 8, 1828;

- He learned the trade of tanning of leathers in Breslau, Prussia;

- He came to Gloversvlle in 1849 and was employed Gilbert Burr and worked in Johnstown for several years;

- In 1861 he established his own tanning business and had a tanning mill near the railroad station;

- In 1865 he built a factory and tannery on South Main Street;

- He married Pauline Gansel in 1856;

- Pauline died in 1862;

- He remarried Rosa Fliegel in 1866;

- Rosa died in 1891;

- He was survived by two sons Herman and Louis Junior; and

- Louis was a member of the Congregational Curch in Gloversville.

Louis Knoff Obituary, The Gloversville Daily Leader, 8 April 1893, Page 8

The obituary is also found in the Fulton County Republican, 13 April 1893, Page 3.

[9] The Duchy of Bernstadt (German: Herzogtum Bernstadt, Polish: Księstwo bierutowskie, Czech: Bernštatské knížectví) was a Silesian duchy centered on the city of Bernstadt, present-day Bierutów in Lower Silesia, currently located in now in Poland.

Silesia (Schlesien), Prussia, German Empire Genealogy, FamilySearch, This page was last edited on 2 August 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Silesia_(Schlesien),_Prussia,_German_Empire_Genealogy

Duchy of Bernstadt, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 20 February 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duchy_of_Bernstadt

[10] States of the German Confederation, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 16 April 2023, Map of German states 1815-1866, by Ziegelbrenner, from Wikipedia, Karte des Deutschen Bundes 1815–1866 / Map of German Confederation 1815–1866, 19 Jan 2008, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/States_of_the_German_Confederation

[11] The family of Louis Knoff:

- Robert (1826–1908)

- Louis (1828–1893)

- William Morris (1829–1906)

- Herman Alexander (1832–1910)

- Amelia Henrietta (1833–1894)

- Hugo Berthold (1836–1914)

- Heinrich (Henry) (1838–1924)

- Henrietta (1841–1921)

- Ellen Bertha (1845–1908)

Source: Ancestry.com family trees and Gerald Everett, Are There Any Knoffs Here? An Inquiry and Some Answers. United States: Gateway Press, 1984.

One must critically evaluate information posted in ancestry.com trees. I have culled information on the family of Louis Knoff through five family trees and from Gerald Everett’s book. Here are some key points about Ancestry Family trees:

Accuracy depends on the owner of the tree

- Ancestry trees are user-submitted, so their accuracy depends on the research and sources of each individual user.

- Some trees are very accurate with good documentation, while others contain many errors and unverified information.

Potential Issues with Ancestry trees

- Many online Ancestry trees contain inaccurate information.

- Users often copy information from other trees without verifying it themselves, propagating errors.

- It is common to find impossible facts in trees, like children born before parents.

- Some users intentionally include false information, fabricating famous ancestors or hiding “undesirable” ones.

Evaluating the reliability of a tree

- Check for citations: Trees with numerous citations to reliable records are more likely to be accurate. Avoid trees that only cite other trees.

- Look for impossible facts like parents born after children or people in two places at once.

- Compare to your existing research to spot discrepancies in names, dates, and locations.

Using Ancestry Trees responsibly

- Treat Ancestry trees as clues to guide further research, not as definitive sources.

- Avoid automatically copying information from other trees into your own, as this can introduce errors.

- Message tree owners politely if you spot errors in their tree.

While Ancestry trees can provide valuable clues and family history information, their accuracy is not guaranteed. It’s crucial to verify all information against primary sources and your own careful research before adding it to your tree.

Adams, Janine, How Accurate is Ancestry?, 9 Aug 2019, Organize your Family History, https://organizeyourfamilyhistory.com/how-accurate-is-ancestry/

Koch, Andrew, 7 Steps for Fact-Checking Online Family Trees, Familytree, https://familytreemagazine.com/strategies/fact-check-family-trees/

Should Your Ancestry Tree Be Public Or Private?, 3 Dec 2023, Family History Daily, https://familyhistorydaily.com/genealogy-help-and-how-to/ancestry-tree-public-private/

Martin, Andrew, How to easily mess-up your family tree with Ancestry, 29 April 2018, History Repeating, UK Family History and Genealogy Blog, https://historyrepeating.org.uk/2018/04/29/how-to-easily-mess-up-your-family-tree-with-ancestry/

Louis’ father and mother were Karl Knoff and Christina Guisler. The family story of Karl Knoff can be found in Gerald Everett. Are There Any Knoffs Here? An Inquiry and Some Answers. United States: Gateway Press, 1984.

“Carl Knoff was born in Festenberg, about 40 km northeast of Breslau (now Wroclaw, Poland), and he moved to nearby Bernstadt, Silesia, where, in 1825, Carl married Christiana Guisler. Carl was a tanner by trade. He and Christiana began to raise a family and they had six sons and three daughters while living in Bernstadt. Gerald E. Knoff considers various reasons for Carl’s decision to immigrate to America: 1) that he did not want his sons to have to serve in the Prussian army, 2) that he came under suspicion after the revolution of 1848, 3) to escape the food famine of the 1840s that affected all of Europe (Ireland the worst, but Scotland, Prussia and Belgium were especially devastated), and 4) to seek economic betterment in the New World. Whatever his reasons, Carl Knoff and son Moritz, age 18-19, left Bernstadt in 1848 and immigrated to Johnstown, New York. Within 3 years Christiana and most of the remaining children would follow.

“1848 — Carl Knoff’s passport was date 27 June 1848 and was issued by the Kingdom of Prussian States. The passport states that Carl would leave from Breslau and travel through Mecklenburg on his way to Hamburg. From this document we also learn that Carl was born in Festenburg, 3 October 1798, and that he lived in Bernstadt, Silesia. It also gives a detailed description of the man: “Religion, Evangelical; Age, Octo. 3, 1798; Height, 5 ft. 2 in.; Hair, Blond; Forehead, High; Eyebrows, Brown; Eyes, Grey; Nose, Strong; Mouth, Normal; Beard, Blond; Chin, Round; Face, Oval; Color, Healthy; Stature, Stocky; Other marks, None.” Carl’s son, Moritz Knoff, 18, was listed on the passport and travelled with him. (Knoff, p. 13)

“Carl Knoff and Moritz arrived on board the Frau Charlotte in New York from Hamburg on 15 September 1848. The age listed for Carl was 21 (30 years off), and 19 for Moritz. They were both listed as farmers.

“1852 — According to Carl Knoff’s Declaration of Intention to become a US citizen, he arrived in the US in September of 1848. The Declaration is dated 9 November 1852. No record has been found to show that Carl completed the citizenship process before he died.”

[12] Louis Knoff Obituary, The Gloversville Daily Leader, 8 April 1893, Page 8

[13] Marie Pauline Gansel, Age 19, Birth date about 1830, Travel date: 1849, Destination: Nord-Amerika, Place of Origin: Balz/Landsberg, Standing: Kind Von Ambrosius.

Source: Wolfert, Marion, comp. Brandenburg, Prussia Emigration Records [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006. Original data: Auswanderungskartei (emigration cards) located at Brandenburgishes Landeshauptarchiv in Potsdam, Germany or Family History Library microfiche #6109219-6109220 (54 total fiches).

This database is a collection of government records regarding persons emigrating from the province in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Each record generally includes the emigrant’s name, age, place of origin, destination, and year of emigration. Many records also include the individuals standing (occupation and/or relationship) and some include the birth date. The database contains the names of more than 61,000 persons.

“Beginning in the early 19th century, the Brandenburg provincial government kept records of people who requested permission to leave the county. Most emigrants went to North America (Nord-Amerika), but a few also went to Australia, the Netherlands, Austria, Russia, or elsewhere. Only those who received permission to leave were listed. ”

Brandenburg, Prussia Emigration Records, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/4121/

Pauline M. Gansel Knoff: BIRTH 1830, Germany; DEATH 28 Feb 1862 (aged 31–32), BURIAL Johnstown Cemetery Johnstown, Fulton County, New York, USA; PLOT Section O, Lot 515; MEMORIAL ID 32491379. Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/32491379/pauline-m.-knoff

[14] Herman Knoff, Birth: 9 Jun 1857, Death: 31 Jul 1915 (aged 58), Burial: Prospect Hill Cemetery, Gloversville, Plot: Sec 57 Knoff Lot, Memorial ID: 32297853, Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/32297853/herman-knoff

[15] Lewis Knoff, 1870 U.S. Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Johnstown, Page 84, Lines 37 – 40 ; Census was taken on June 24, 1870. The enumerator indicated that Louis Knoff Junior was three months old which implies he was born in March 1870

Louis Knoff Jr, Birth Date 20 Mar 1970, Death date: 11 Apr 1941, Burial Place: Prospect Hill Cemetery, Gloversville, Memorial ID: 32297861, Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/32297861/louis-knoff

1875 New York State census, Fulton County, Johnstown, Enumeration District 02, Page 428

1880 Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Gloversville, enumeration District 006, Page 95A

1900 Federal census, New York, Fulton County, Gloversville, Ward 2, Enumeration District 009, Page 8B

1905 New York State census, Fulton County, Gloversville Ward 02, Election District 01, Page 43

1910 Federal census, New York, Fulton County, Gloversville Ward 2, Enumeration District 0012, Page 10A

1915 New York State Census, Fulton County,

1920 Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Gloversville, Ward 1, Enumeration District 7, Page 11B

[16] New York Land Records, Fulton County, Deeds, 1867 – 1869, vol 35 -36, vol 35, page 116 “United States, New York Land Records, 1630-1975.”Database with images. FamilySearch. https://FamilySearch.org : 14 June 2024. Multiple county courthouses, New York.

[17] Webster, Ian, CPI Inflation calculator, $2,500 in 1867 → 2024 | Inflation Calculator.” Official Inflation Data, Alioth Finance, 21 Aug. 2024, https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1867?amount=2500

[18] Household of Eliphalet Veeder, New York States census, Fulton County, Johnstown, Page 492, Line 35

[19] Hayden, Martha, Plank Roads – A short Era in History, August 9, 2022, The Restless Viking, https://www.restless-viking.com/2022/08/09/plank-roads-a-short-era-in-history/

Heller, Dorothy, Plank Roads, December 30, 2020, Town of Clay, https://townofclay.org/departments/historian/history-mysteries/plank-roads

List of plank roads in New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on May 8, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_plank_roads_in_New_York

Blast from the Past: Old Plant Roads of Fulton County, May 7 2023, Daily Gazette, https://www.dailygazette.com/leader_herald/towns/fulton_county/blast-from-the-past-old-plank-roads-of-fulton-county/article_f7c89026-b43c-5e62-9546-1cd6864a0008.html

[20] Atlas of Montgomery and Fulton, Published by J. Jay Stranahan and Beach Nichols in 1868, digitalized by the David Ramsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries, https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~226773~5506920:Gloversville,-Fulton-County,-New-Yo

[21] New York Land Deeds, Fulton County, Volume 34. Pages 538 & 539, 13 Nov 1867, Grantor: Louis and Rosina Knoff, Grantee: Fonda, Johnstown & Gloversville Railroad (FJ&G) company

[22] The New York State Legislature passed an act on April 2, 1850 entitled “An Act to authorize the formation of railroad corporations and to regulate the same”. This law allowed railroad companies to acquire land and property under the provisions of the act in order to construct and operate their railroads. Specifically, Section 14 of the 1850 law stated that railroad corporations “may acquire under and in virtue of the provisions of this act” any real estate required for the construction and operation of the railroad, and all necessary lands.

The law empowered railroad companies to acquire property through eminent domain if needed for their rail lines. If the railroad was unable to obtain the land by contract or agreement, it was authorized to acquire the property “in the manner provided by law for the appropriation of private property for public use”.

This 1850 law was a key piece of legislation that facilitated the rapid growth of railroads in New York in the mid-19th century by granting them the legal authority to obtain the land required to build their routes. It was one of several important railroad laws enacted in New York State between 1850 and 1871

Railroad Laws of the State of New York From 1850 to 1971 inclusive, Albany: Weed, Parsons and Company, 1871, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Railroad_Laws_of_the_State_of_New_York_f/NEA1AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA1&printsec=frontcover

[23] Larner, Paul, Our Railroad: The History of the Fonda, Johnstown & Gloversville railroad (1867 – 1893), Bloomington, Anchor House, 2009, Page 26

[24] John Sperber, Grantee, Ellery R. Corey, Grantor, 14 Feb 1868, Fulton County Deeds, Volume Number 36, Page Number 115

[25] As indicated in a prior story, the house and business numbering system within Gloversville changed a number of times throughout Gloversville’s history. The numbering system appeared to remain constant between 1893 and 1903. Information in Gloversville City Directories in the ’90s confirm the Sperbers lived at 243 South Main Street and the Knoffs lived at 246 South Main Street.

[26] See Image 22 of Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from 1902 Gloversville, Fulton County, New York, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Gloversville, Fulton County, New York., Sanborn Map Company, Oct 1902, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3804gm.g3804gm_g059511902/?sp=22&st=image

Sanborn maps were distinguished in the 1800s by their highly detailed depictions of U.S. cities and towns for fire insurance purposes. Some key distinguishing features of Sanborn maps from this time period include:

Detailed building information: The maps outlined each building and included details like construction materials (indicated by color), number of windows and doors, and locations of fire walls. This allowed fire insurance companies to assess risks for individual properties.

Extensive coverage: By the late 1800s, Sanborn was mapping thousands of cities and towns across the U.S., making their maps the most comprehensive set of fire insurance maps available. Even small towns that may have been overlooked by other mapmakers were often covered by Sanborn.

Standardized symbols and colors: Sanborn developed a sophisticated and consistent set of symbols and colors to represent building features, allowing complex information to be conveyed clearly on the maps. For example, yellow always indicated a wooden structure while red indicated brick.

Large-scale, regularly updated maps: The maps were produced at a detailed scale of 50 feet per inch on large 21 by 25 inch sheets. For many towns, updated maps were released as often as every five years to reflect changes.

Dominance in Fire Insurance mapping: Although other companies produced fire insurance maps in the 1800s, by the early 1900s Sanborn had become so dominant that their name was synonymous with the industry. Their extensive, standardized, and frequently updated maps made them the leader in fire insurance mapping.

Sanborn Maps, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 1 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanborn_maps

Notes from the Field: Mapping History with Sanborn Maps, HAI Legal: The Factual Research and Analysis Consultancy, https://www.hailegal.com/sanborn-insurance-maps/

Wertz, Frederick, Fire Insurance Maps: Sanborns and Others, Dec 13, 2019, New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, https://www.newyorkfamilyhistory.org/blog/fire-insurance-maps-sanborns-and-others

What is a Fire Insurance Map, HistoryMosaic, https://historymosaic.com/resources/

Ristow, Walter W., Introduction to the Collection, Library of Congress, Fire Insurance Maps: in the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/sanborn-maps/articles-and-essays/introduction-to-the-collection/

How to Read Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, May 26 2000, Geostat, Charlottesville: University of Virginia, http://projects.mcah.columbia.edu/courses/newyork/pdf/SanbornMap_instruct.pdf

Introduction to the Collection, Sanborn Maps, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/sanborn-maps/articles-and-essays/introduction-to-the-collection/

[27] Kidskin, Wikilpedia, This page was last edited on 16 October 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kidskin

[28] Alum paste tanning involves applying a paste made of alum, salt, and water directly to the flesh side of the hide. The main types of alum include potassium alum (potash alum), sodium alum (soda alum), ammonium alum, and chrome alum.

The hide is then covered and left for several days. Alum paste can be scraped off and disposed of in a sealed bag, making cleanup easier since the alum doesn’t contaminate a large volume of water.

Invicta Flies – Tanning with Alum, https://invictaflies.tripod.com/id211.htm

Aluminum Sulfate Tanning, Van Dyke’s, https://www.vandykestaxidermy.com/Aluminum-Sulfate.aspx

Tawing with alum, Leather Dictionary, https://www.leather-dictionary.com/index.php/Tawing_with_alum

Roger Barlee, Aluminium Tannages, Volume 11, Spring 2001, J Hewit & Sons Ltd Leather Manufacturers, https://www.hewit.com/skin_deep/?volume=11&article=2

[29] Barbara McMartin, The Glove Cities: How A People and Their Craft Built Two Cities, NY: Lake View Press, 1999, page 50

[30] Due to a number of political and bureaucratic conflicts, no state census was taken in 1885. New York State coordinated a census in 1892, and skipped the census which should have occurred in 1895, and then resumed census-taking every ten years in the fifth year of each decade—1905, 1915, and 1925. Records for the 1992 census are not available for all counties. All but 13 New York counties are available for this census. Fulton county is not available.

Most of the 1890 Federal census records were badly damaged by a fire in the Commerce Department building in January 1921. Only fragments of the general population schedules for some states and D.C. survived. There are no records of Fulton county for the 1890 census.

New York State Census Records Online, New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, https://www.newyorkfamilyhistory.org/subject-guide/new-york-state-census-records-online

Availability of 1890 census, United States census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/history/www/genealogy/decennial_census_records/availability_of_1890_census.html#:~:text=Most%20of%20the%20census’%20population,in%20its%20Spring%201996%20Prologue.

U.S. Census Bureau History: 1890 Census Fire, January 10, 1921, https://www.census.gov/history/www/homepage_archive/2021/january_2021.html

Eleventh census of the United States, 1890. M407.3 rolls, National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/research/census/microfilm-catalog/1790-1890/part-08

1890 United States census, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 19 July 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1890_United_States_census

New York State Censuses, FamilySearch Wiki, Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/New_York_Census_State_Censuses

New York State Censuses, FamilySearch Wiki, Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/New_York_Census_State_Censuses

[31] Rosina (Fliegel) Knoff, Birth: 4 Mar 1826, Death: 22 Jan 1891 (aged 64), Burial: Prospect Hill cemetery, Gloversville, NY; Plot: Sec 57 Knoff Lot; Memorial ID: 32297870, Find A Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/32297870/rosina-knoff

Rosina Knoff, New York Wills and Probate Records, Letters Test, Volume 0002-0003, 1856 – 1901, Page 498

[32] Louis Knoff Obituary, The Gloversville Daily Leader, 8 April 1893, Page 8

Louis Knoff, Birth: 8 Jan 1828; Death: 7 Apr 1893; Burial: Prospect Hill Cemetery, Gloversville, NY; Plot: Sec 57 Knoff Lot; Memorial ID: 32297867; Find A Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/32297867/louis-knoff

Louis Knoff, Administrators Bonds, 1890 – 1899, Page 183

[33] A Carl Knoff is found in the 1900 Federal census but lives in Johnstown, N.Y. He was a boarder living on Burson Street in Johnstown. He was 36 years old, single, and was a leather finisher. It is not known if he was related to the Knoff brothers.

Carl Knoff, 1900 U.S. Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Johnstow Ward 01, District 0018, Page 8, Line 28.

He is also found in the 1910 U.S. Federal census at the age of 47. He is still a boarded but at a different address and is employed at a Leather Mill.

1910, U.S. Federal census, New York, Fulton County, Johnstown Ward 2, District 0027, Page 6, Line 43

[34] Louis Knoff, Birth 20 Mar 1870; Death 11 Apr 1941 (Aged 71), Burial: Prospect Hill Cemetery; Gloversville, Fulton County, NY; Memorial ID: 32297861, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/32297861/louis-knoff

Louis Knoff Junior, Marriage certificate 14299

[35] Louisa Schmidtt’s birth date is uncertain. Her gravestone indicates she was born in 1871.

Louisa M Schmitt wife of Louis Knoff Jr., Birth: 16 Aug 1871, Death: 27 Feb 1957 (Aged 85); Burial: Prospect Hill Cemetery; Plot Sec 57 Knoff Lott; Memorial ID: 32297862, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/32297862/louisa-m-knoff

However, her reported birth date in Federal and State census years varies. Her reported birth date in 1840 corresponds with the date that was inscribed on her headstone. Otherwise, another likely birth year is 1873.

Reported Birth Dates in Various Federal & State Census

| Year | Reported Age | Brith Year |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 27 | 1873 |

| 1910 | 37 | 1873 |

| 915 | 43 | 1872 |

| 1920 | 47 | 1873 |

| 1930 | 50 | 1880 |

| 1940 | 69 | 1871 |

| 1950 | 73 | 1877 |

Louisa Schmidtt, Marriage certificate 14299

[36] The address location for the household of Louis and Louisa Sperber is based on information in the 1990 census that indicates street number and street.

[37] Facts related to the births of Louis and Louisa Knoff’s children are based on information from Birth Index records and social security records.

The Children of Louis Knoff Jr. and Louisa Knoff

| Name | Birth date |

|---|---|

| Charlotte Rosina Knoff | 21 AUG 1895 |

| Lillian Gertrude Knoff | 23 NOV 1896 |

| Florence Elizabeth Knoff | 17 SEP 1898 |

| Marion Augusta Knoff | 22 JUL 1906 |

Charlotte Rosina Knoff, New York State Birth Index, 1881-1942, New York State Department of Health, 1895, Brith certificate No. 35361, Page 470

Charlotte Rosina Knoff, New York Death Index, New York State Department of health, 1895, Death Certificate No. 51565

Lillian G. Knoff, New York State Birth Index, 1881 – 1942, 1896, certificate No. 51462, Page 483

Florence Elizabeth Knoff Dutcher, Birth: 17 Sep 1898; Death: 28 Oct 2001 (aged 103), Burial: Prospect Hill Cemetery, Gloversville, NY; Memorial ID: 112660825, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/112660825/florence-elizabeth-dutcher

Florence K Dutcher, U.S. Social Security Applications and Clams Index, 1936 – 2007, Birth Date 17 Sep 1898, 20 Oct 2001, Claim Date: 7 Jun 1963, SSN: 097283041

Marion Augusta Selmser, Birth: 22 Jul 1906; Death: 19 Jan 2005; Burial: Prospect Hill cemetery, Gloversville, NY: Plot: Section 115; Memorial ID: 236510560, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/236510560/marion-augusta-selmser

Marion Selmser, U.S. Social Security Death Index, SSN: 086-2653; Birth Date: 22 Jul 1905, Issue Year: 1962; Death Date 19 Jan 2005

[38] In addition to occupational references in Federal population censuses, local Newspaper articles refer to Louis Knoff as a motorman. For example a human interest story about Louis finding a 7 leaf clover refers to him as a motorman.

He was also a witness in a state Supreme Court case involving personal injury to a woman riding the electric train in Gloversville. His testimony was related to his actions as the motorman in the rail car.

Source: The Johnstown Daily Republican, Wednesday, June 5, 1901, page 3: See article

[39] Ella Sperber, Grantee, Andrew D. Simmons, Grantor, 27 Nov 1886, Entry Number 68, page Number 287, Index of deeds, Fulton County, New York, page 689, line 9

New York Land Records, Fulton County, Deeds 1886 – 1887, Vol 68 , Page 287

[40] Frederick Sperber Household, 1900 Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Gloversville Ward 02, District 0009, Page 6, Lines 30 -35

[41] Sophia Sperber, Birth: 28 Oct 1832; Death: 17 Mar 1897 (aged 64); Burial: Prospect Hill cemetery; Plot: Sec 8; Memorial ID: 158847782; Find A Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/158847782/sophia-sperber. The Find A Grave source, incorrectly indicates Sophia was born in Baden Baden. She was born near Heidelberg, in Ittlingen.

[42] Ida M. Sperber, Marriage certificate 5207, 25 Mar 1897 Gloversville, New York State Department of Health; Albany, NY, USA; New York State Marriage Index, New York State Marriage Index, New York State Department of Health, Albany, NY.

Ancestry.com. New York State, Marriage Index, 1881-1967 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2017., 1987, Page 767, Marriage certificate 5207

[43] Gloversville City Directory 1903, O. .H. Bame & Co., Page 201