This two-part story is sandwiched in between a number of immigration stories related to the Fliegel and Sperber branches of the Griffis family. What prompted these family descendants? What made them use a specific European port to begin their journey to the United States? Once they got to the United States, with so many possibilities, what prompted them to head beyond New York City to an inland destination? For our family, why did they end up in the Gloversville, New York area to establish a home base?

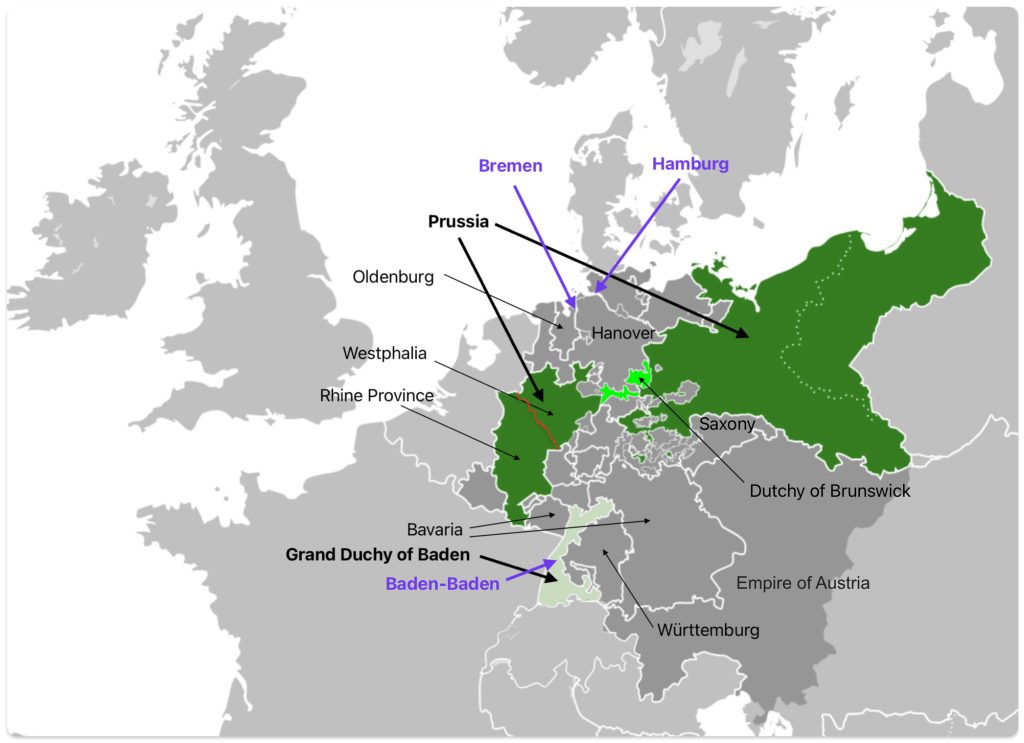

These are fundamental questions associated with understanding the lives of the German descendants of the Griffis family that emigrated in the mid 1850s from the Grand Duchy of Baden. [1] While we do not have direct evidence that answers these questions, historical evidence and analysis of the past history of German immigration from the Baden area can provide an appreciation of what influenced their decisions.

This story takes a look at the following possible historical influences associated with German immigration from Baden in the mid 1800s:

- Learning from the past: local influences their local communities in Baden and knowledge about past generation’s migration strategies to America;

- The price of migration: how the cost of travel impacted their decisions;

- Influence of the State: Baden subsidized emigration to reduce the agricultural pressures experienced the 1850s; and

- the Influence of Chain Migration: utilizing practical information gleaned from other emigrants or relatives that made the trip.

The second part of this story looks at:

- Travel Agents & Brokers: the influence of travel agents on facilitating travel; and

- Travel literature: the information contained in emigration maps, newspaper, and books as a reflection of accumulated knowledge of migration.

It is not known if these specific contextual factors were major influences in the decisions of the Fliegel family and John Sperber to move to America. The historical information on the above mentioned influences, however, provides an added dimension of what they, in general, possibly experienced or what informed their strategies when coming to their new homeland.

There were many factors that influenced John Sperber and the Fliegel family to immigrate to the United States in the late 1840s and early 1850s.

Table One: Arrival Dates of Fliegel and Sperber Family Members to United States

| Arrival Date | Departing Port | Arriving Port | Family Member |

|---|---|---|---|

| May 1848 | Havre | New York | Catherine Fliegel |

| Jun 1852 | Havre | New York | John Sperber |

| Jan 1855 | Havre | New York | Remainder of Fliegel Family (Christoph, Juliani, Phillipp, Rosina, Sophie) |

With an understanding of the historical facts associated with mid eighteenth century German immigration, there are four things that can be gleaned from the information in table one about the Fliegels and John Sperber coming to America.

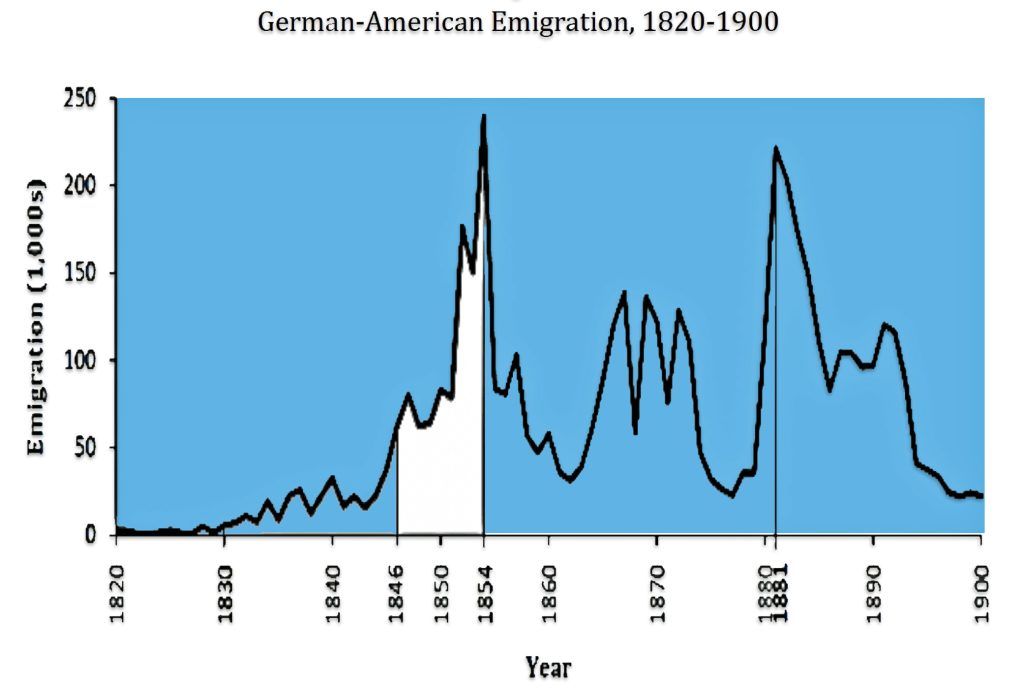

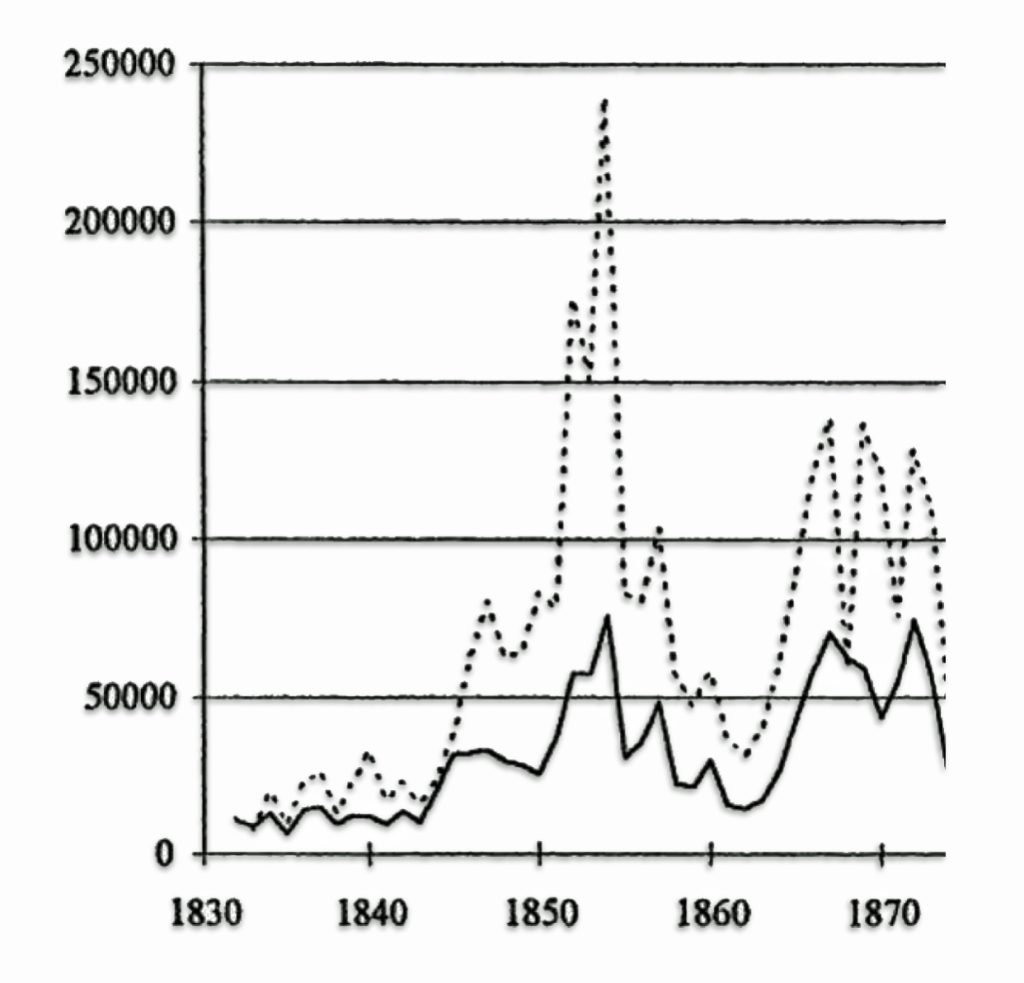

The Fliegel family and John Sperber immigrated between 1848 and 1855. It was a period that witnessed the greatest number of Germans immigrating to the United States. It also was a period of immigration largely represented by Germans emigrating from the south western German states.

“Between 1849 and 1854 emigration from Württemberg, Baden, the Bavarian Palatinate and Main regions, and from the Grand Duchy of Hesse totaled nearly 350,000 individuals, around 60% of the entire German total. Württemberg led with over 140,000 migrants, the Palatinate and Franconian Main regions sent 80,000, Baden over 62,000, and the Grand Duchy of Hesse over 50,000 . Emigration from the South West had evolved from a movement generated by anti-competitive measures in the wage economy, to a larger movement that had come to affect entire communities unable to support themselves on small-scale agriculture, to a mass phenomenon which affected the entire region with great force in the face of widespread economic collapse.” [2]

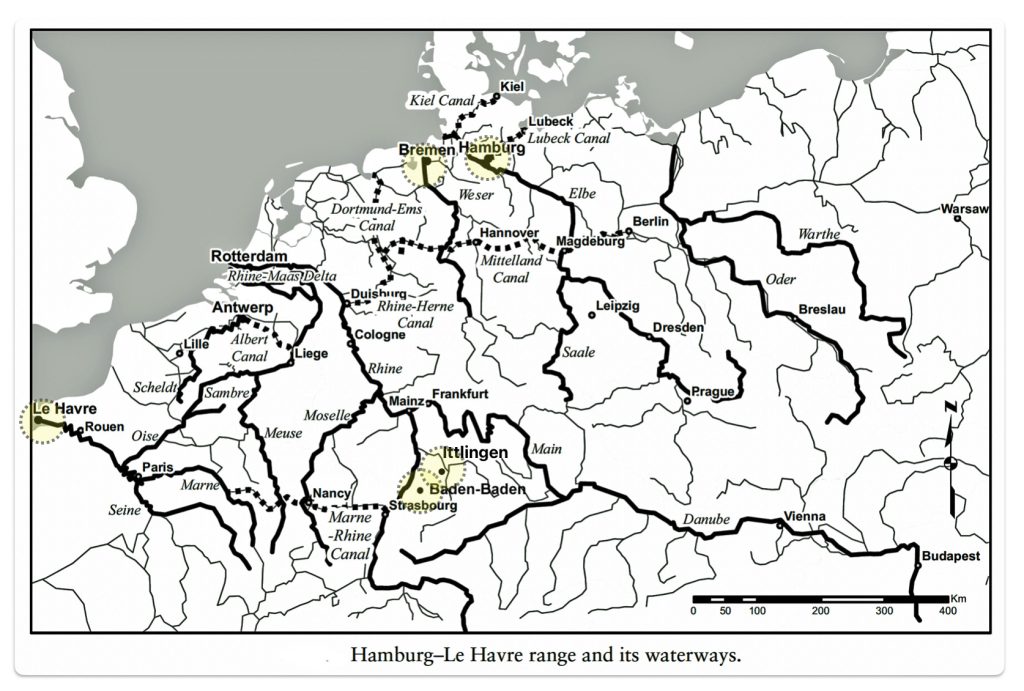

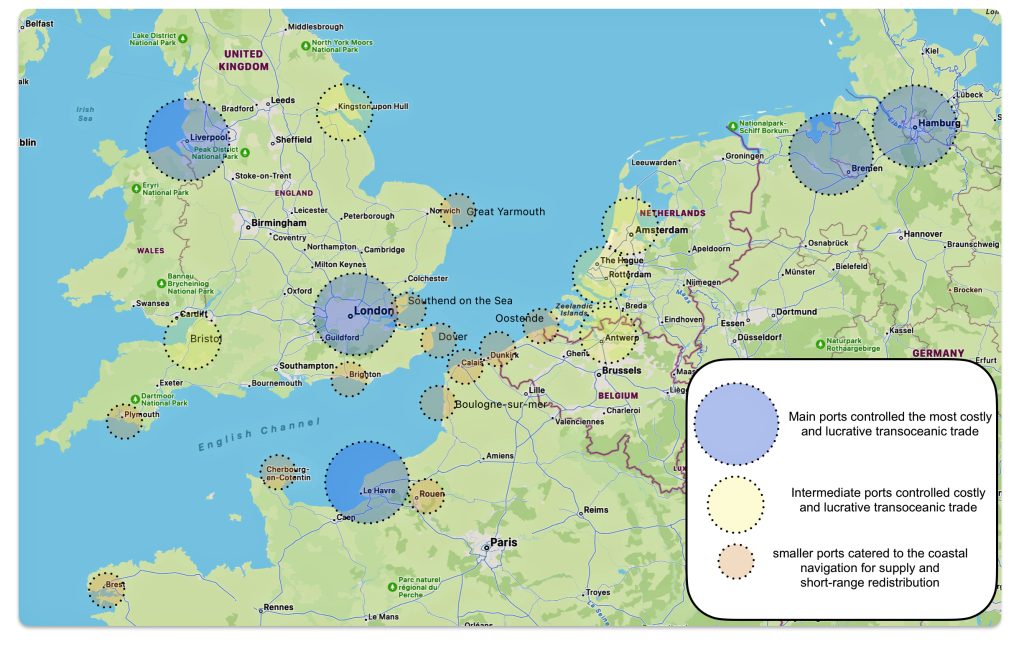

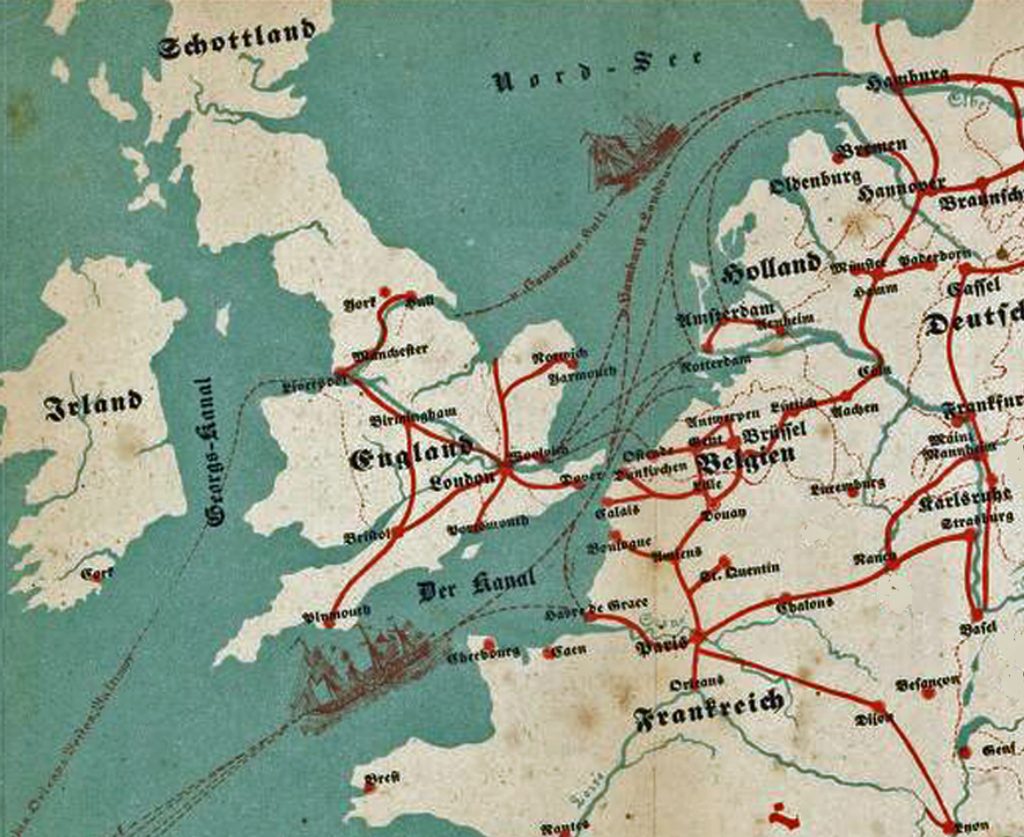

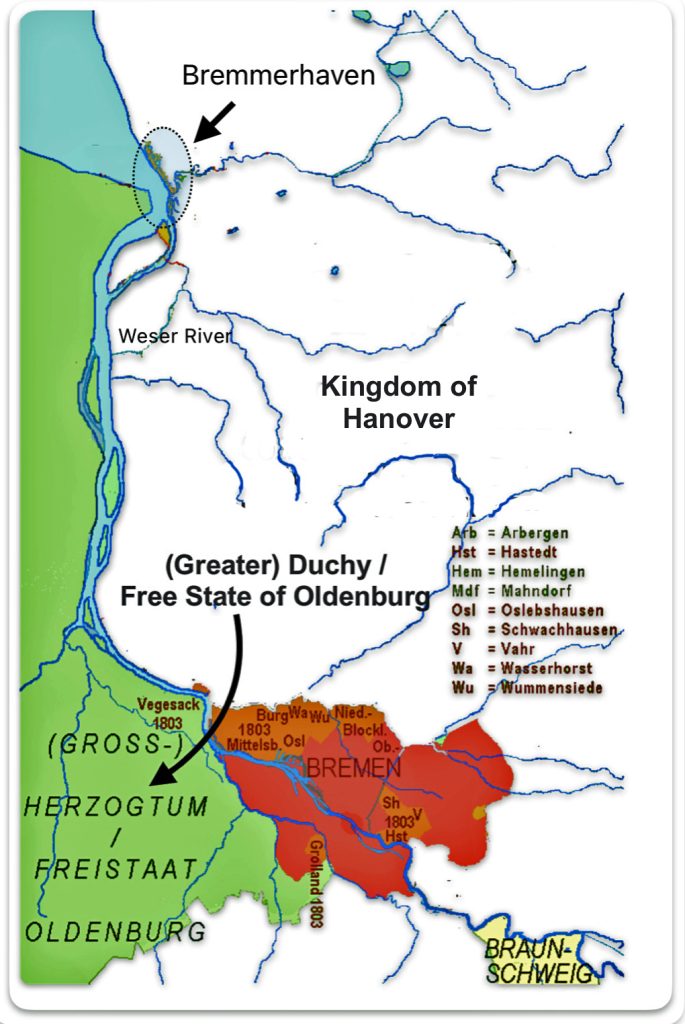

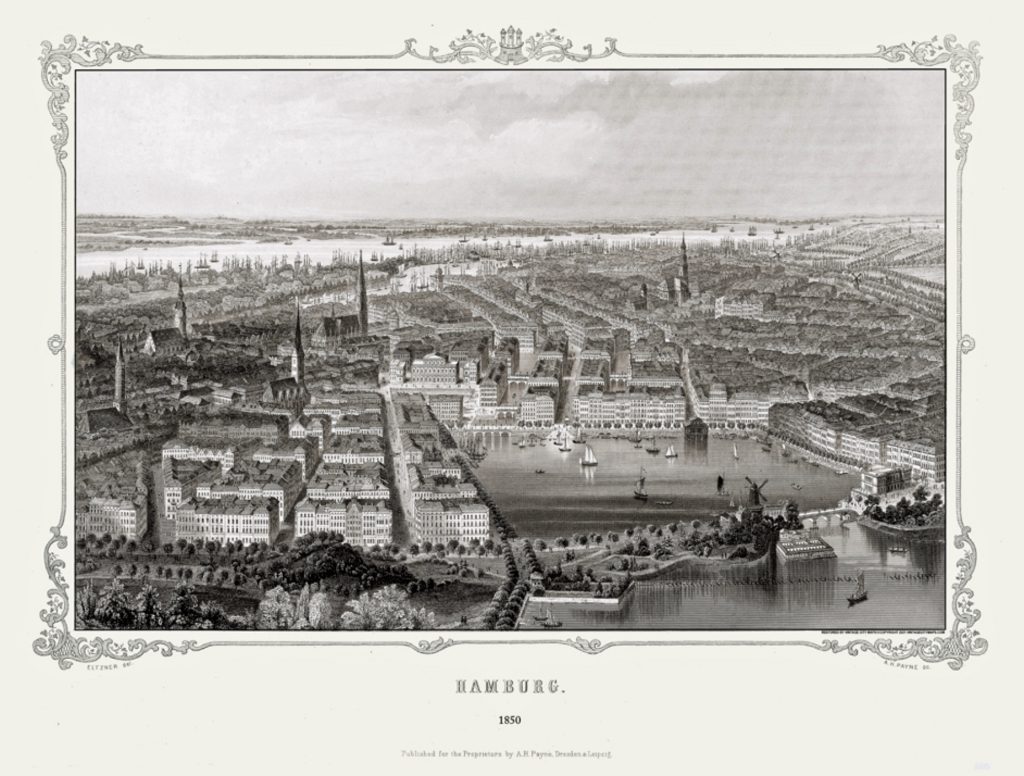

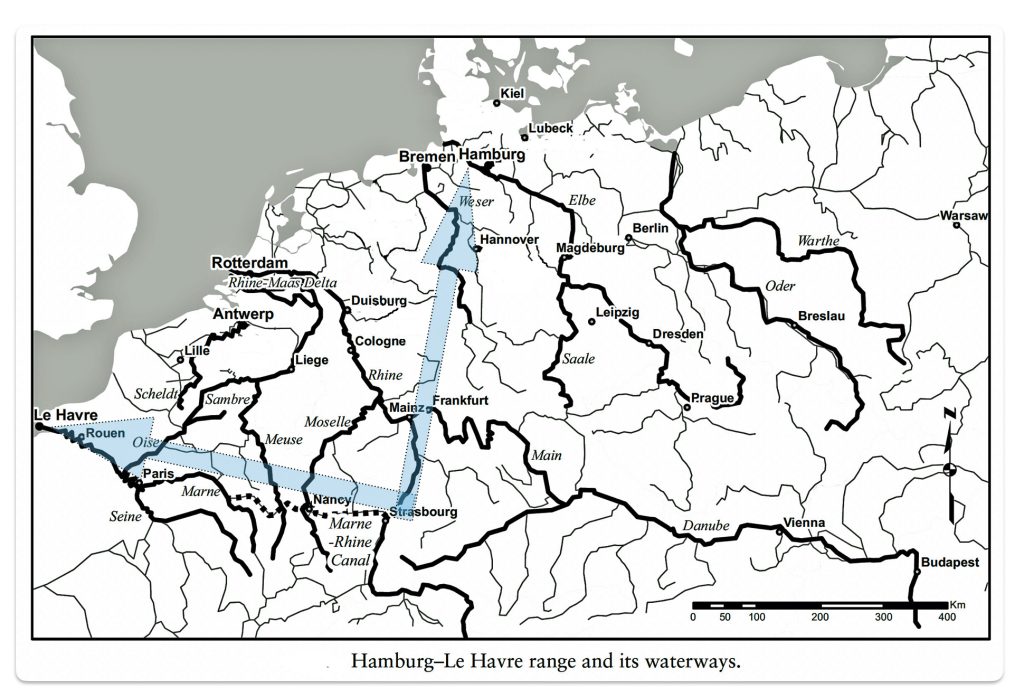

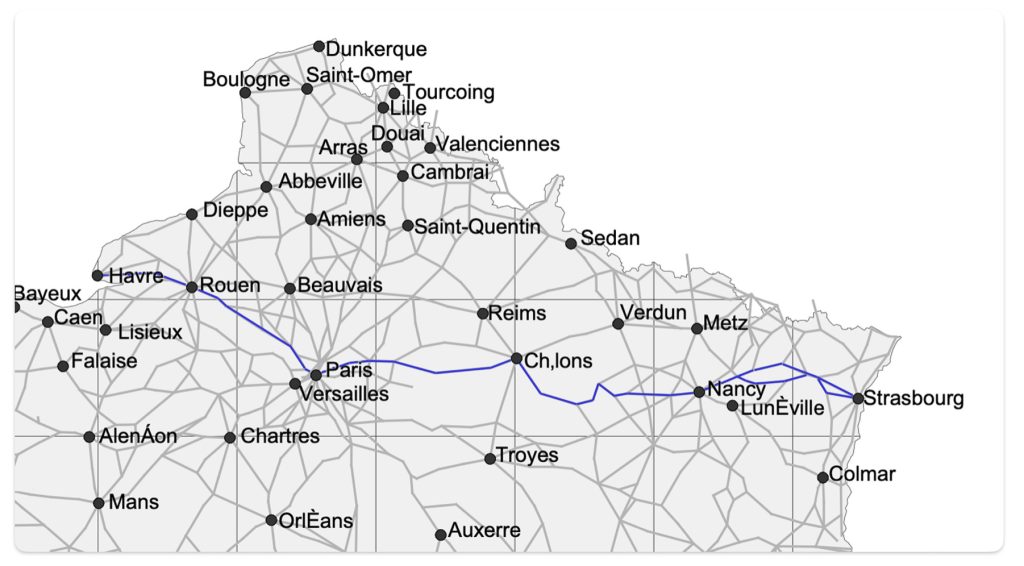

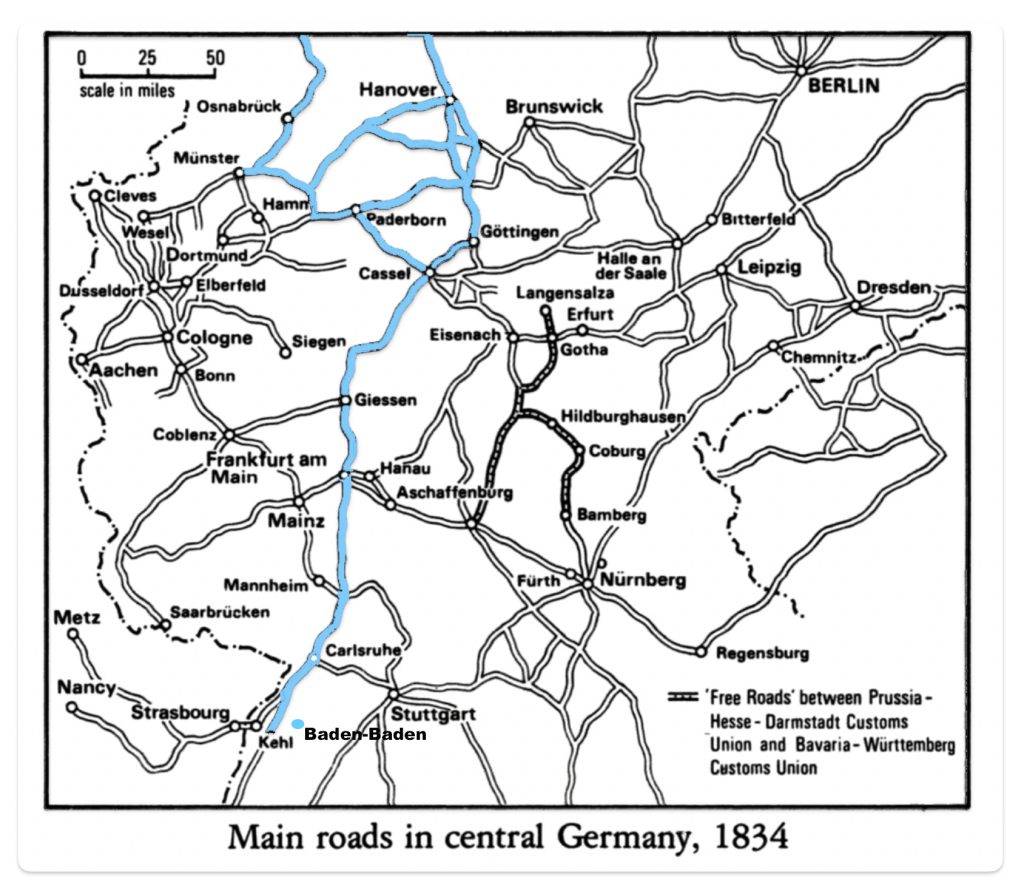

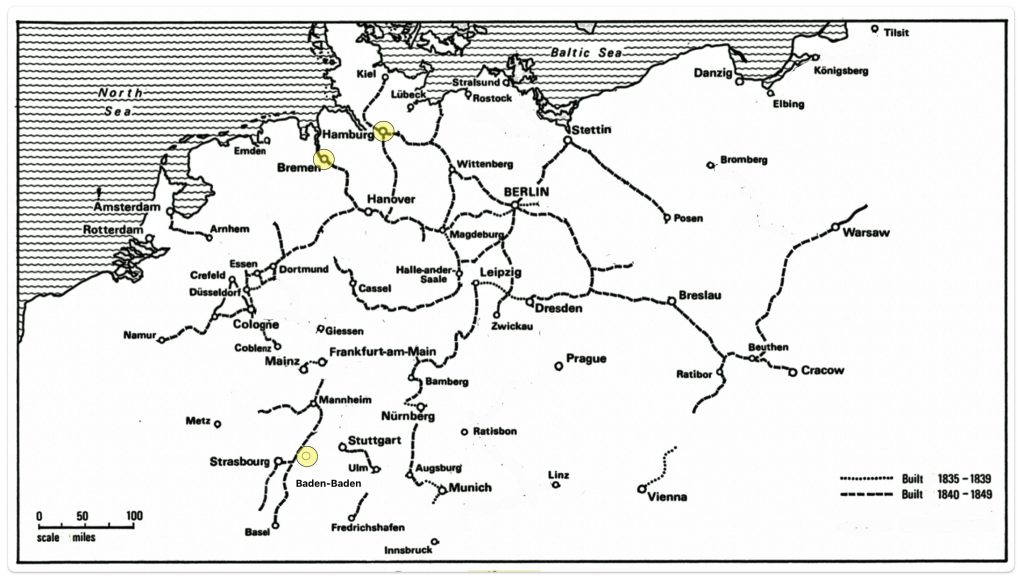

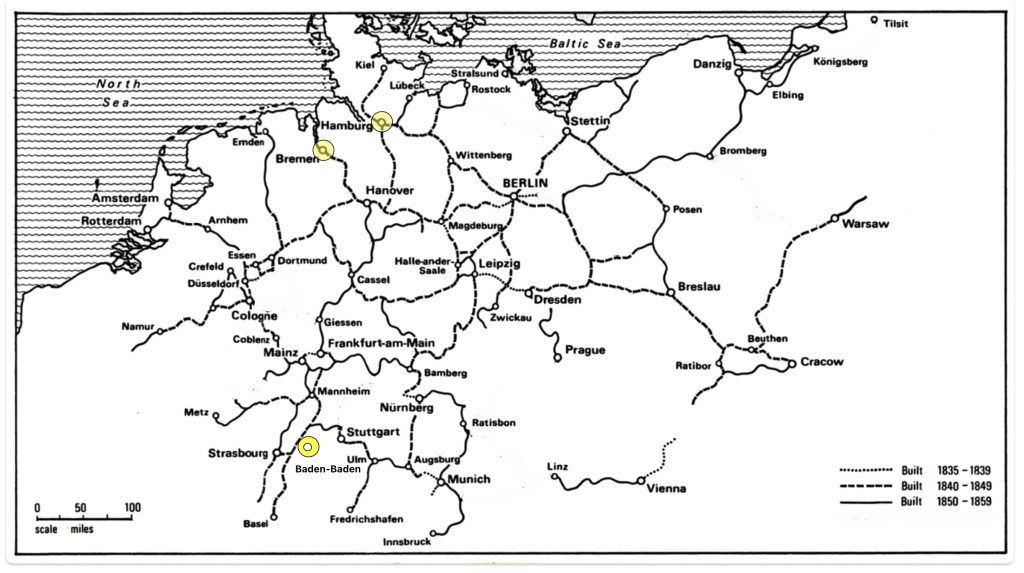

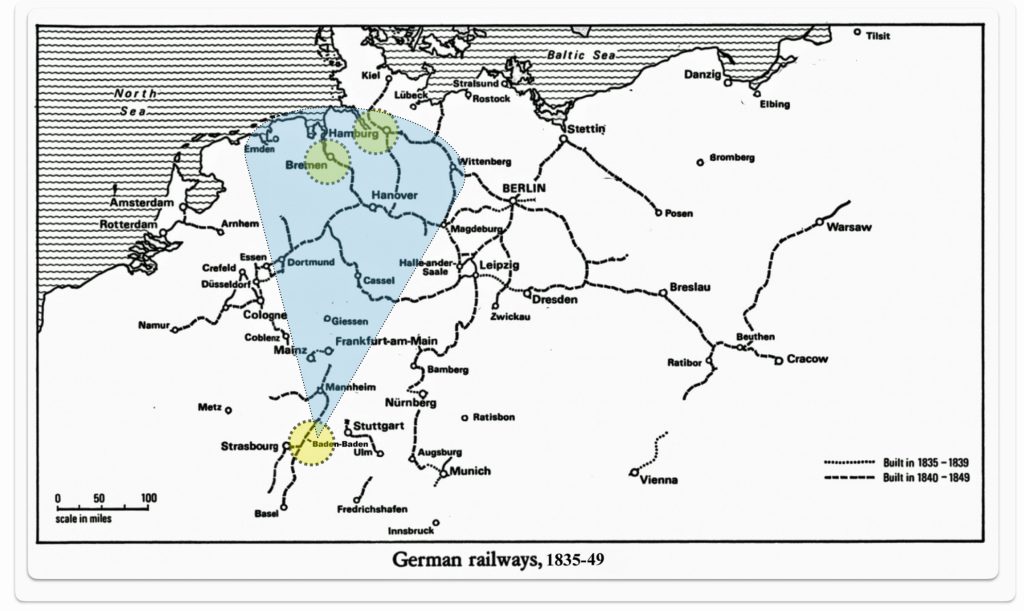

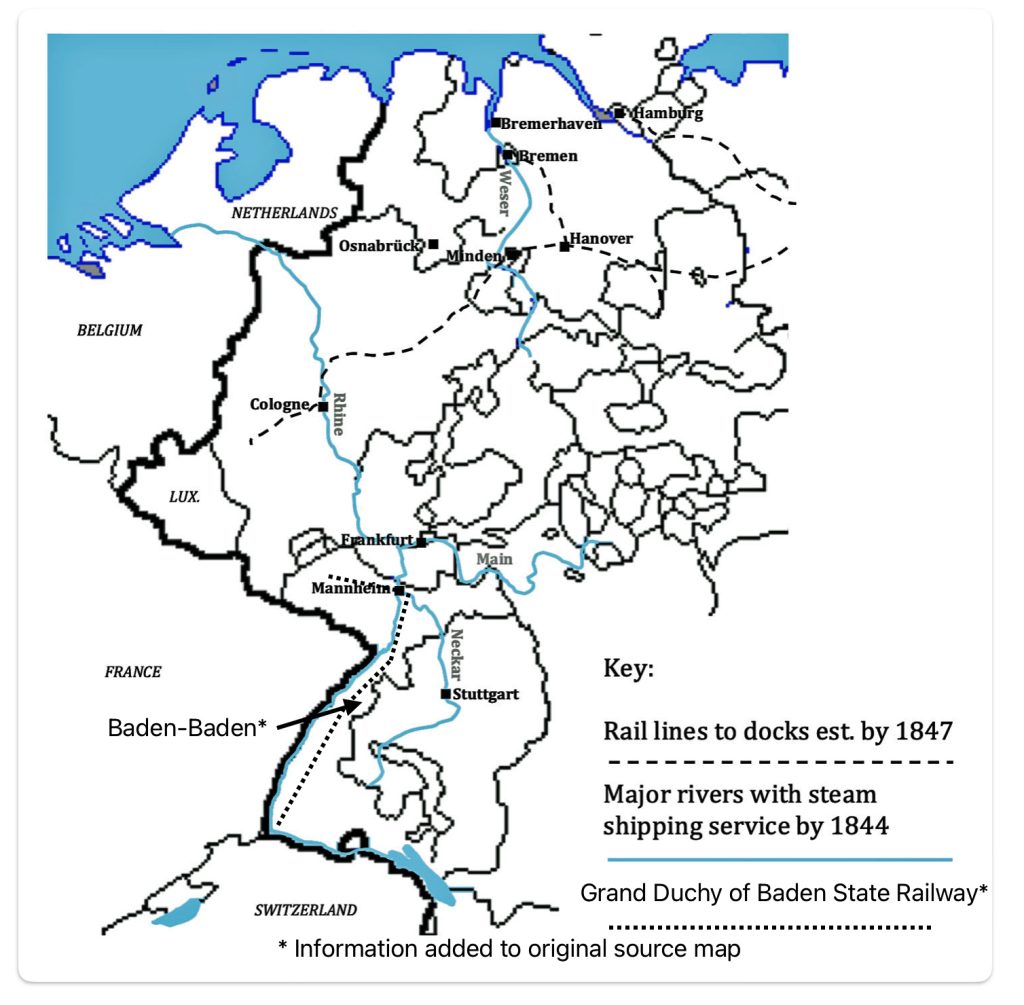

They all departed from Le Havre, France and arrived in New York City. This was one of the predominant paths for southwest Germans to emigrate from their homeland. It was an immigration route that was used by Germans from Baden since the 1830s.

Prior waves of immigrants from the south-western German states traveled downstream on the Rhine to Rotterdam. For a number of reasons, [3] after the 1820s, ports of embarkation changed. Le Havre, France became a major port for German emigrants from Baden.

“In their renewed search for passage in the 1830s, emigrants from the German South West initially found a convenient port of departure at Le Havre. The French harbour was an importer of raw American cotton, a material that was then forwarded on to the mills of Alsace. The freight made its way up the Seine by steamboat and barge to Paris, and then onward by coach to Strasbourg. This meant hundreds of empty wagons and barges returning along the same route, and emigrants from Baden and Württemberg either filled them, or followed them, meeting empty cotton ships at the coast, providing free-paying ballast for the shippers on their return leg to America.” [4]

The characteristics of the emigration patterns of the Fliegel family exhibit the classic description of chain migration. [5] Catherine Fliegel was the first of her family to establish a foothold in America in 1848. Seven years later, her adult siblings and her parents made the trek to where Catherine and her newly established family resided in the Gloversville-Johnstown area. John Sperber’s trek to America, on the other hand, fits the profile of young male Germans traveling alone. [6]

The seven year period in which the Fliegels and John Speber emigrated were notable years of economic and social hardship. The specific years in which they emigrated from Baden (e.g. 1848, 1852, and the winter of 1854/1855) were years that witnessed specific episodes of severe economic conditions that resulted in upticks of emigration.

Catherine Fliegel immigrated in the spring of 1848 to the United States just after a period of severe economic hardship and emerging political tensions.

“The winter of 1846-1847 was one of suffering, with food supplies short and speculators busy. Many factory districts were obliged to depend upon charity, and almost all but the most prosperous farmers felt the pinch of high prices when buying the food their fields had failed to yield.” [7]

While the Baden Revolution, a regional uprising that occurred 1848/1849, was around the time of Catherine Fleigel’s emigration, the majority of German immigrants were not politically motivated. If there was any revolutionary activity in rural areas, it was not the major cause of emigration. We do not have direct evidence of whether or not Catherine Fliegel was involved with the political discontent. [8]

Distressed agricultural production , the inability to feed a growing population base, political unrest, the erosion of the cottage linen industry and economic depression, combined with a burgeoning press to spark unprecedented political mobilization in the late 1840s, created fertile conditions for emigrating.

Germany had escaped the catastrophe that ravaged Ireland in the mid 1800s because its economic structure relied on more than just potatoes. However, despite variations of cultivated crops, disease and pests, hailstorms and floods ruined whatever prospects they had. Prior to John Sperber’s journey to America, the winter of 1851 was notably harsh in its effects due to the shortage of grain and potatoes. [9]

While emigration began to pull on many of the local villages in Baden as a result of the crop failures of the late forties, during 1852, the year John Speber emigrated, the trickle of emigration from various villages of emigrants became a flood. By 1852, the rural situation in Baden was desperate. During what was known as the ‘winter of hunger’, the wine growing regions of Baden were impacted along with other food growing areas. [10]

The next few years Baden, as well as other German states, witnessed successive periods of downturns in agricultural production. It was during this period of time, the Fliegel family finally decided it was time to follow Catherine Fliegel to the America.

“The sequential failure of the potato crop, grain harvest and grape harvest completely collapsed the fragile rural economy. In villages where American emigration was already deeply entrenched and close connections with the New World and 1854 saw unprecedented departures. [11]

Grand Duchy of Baden: A Land with a Rich History of Internal and External Migration

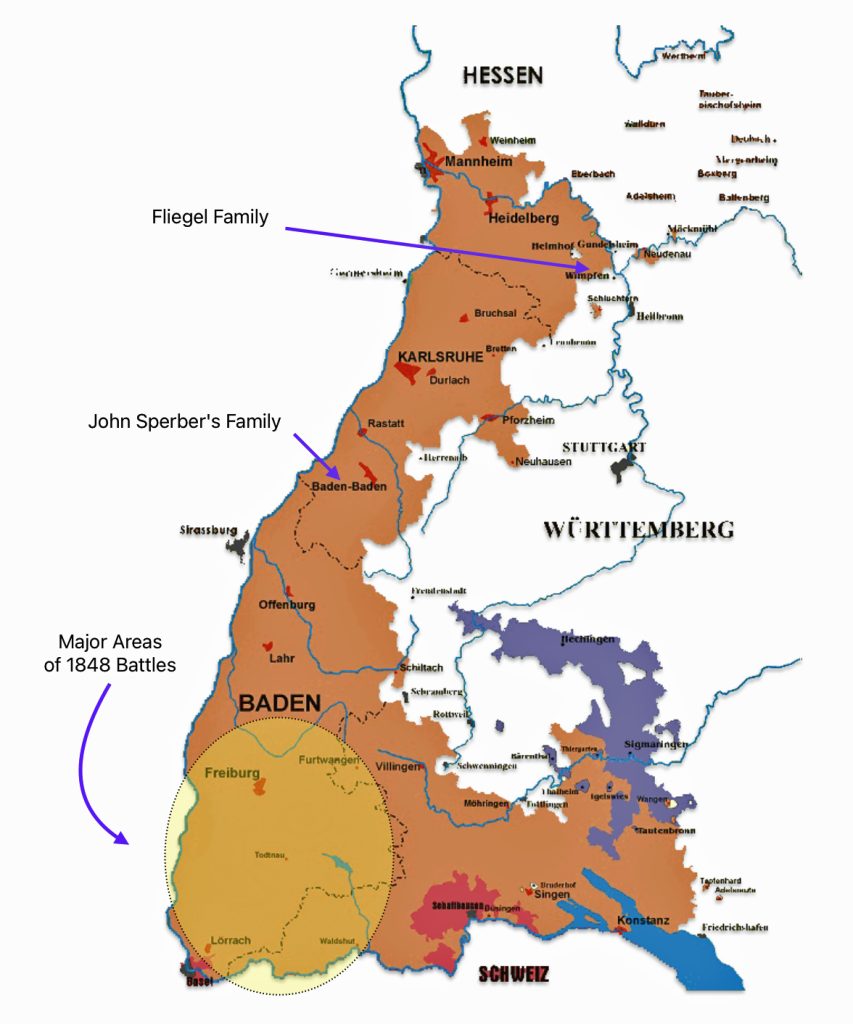

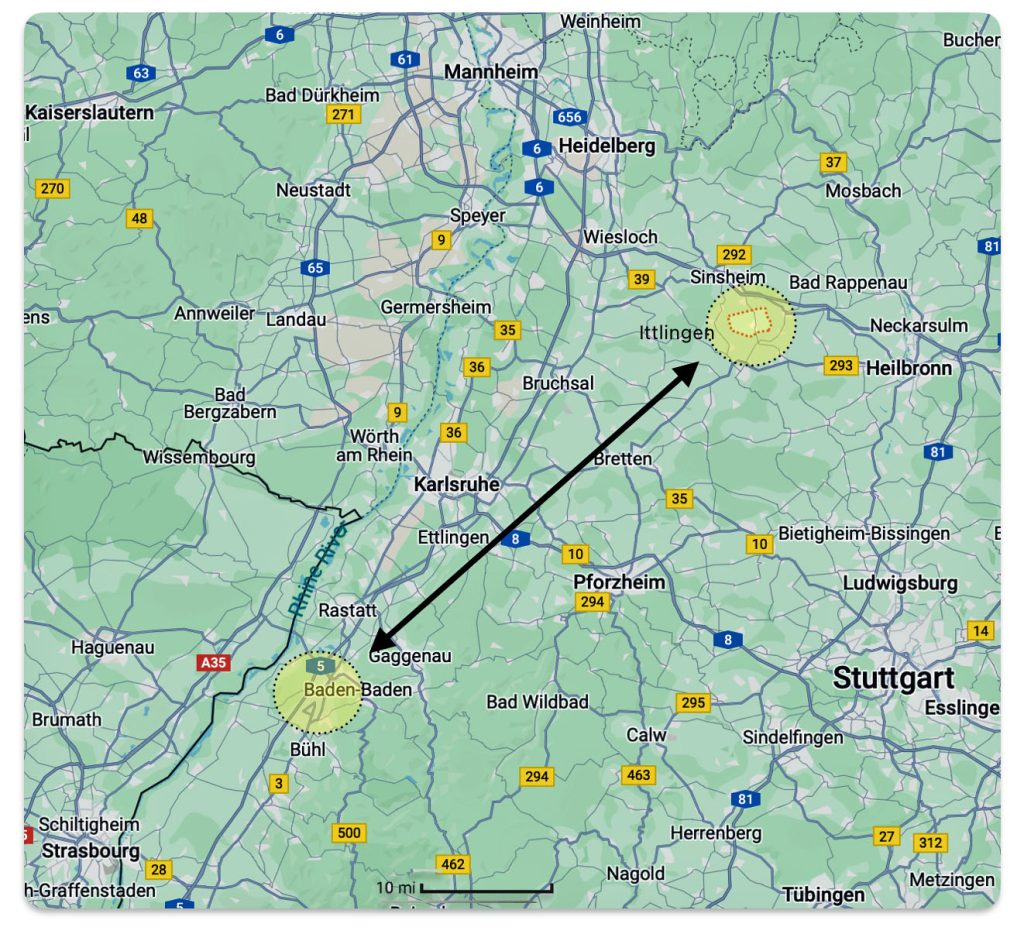

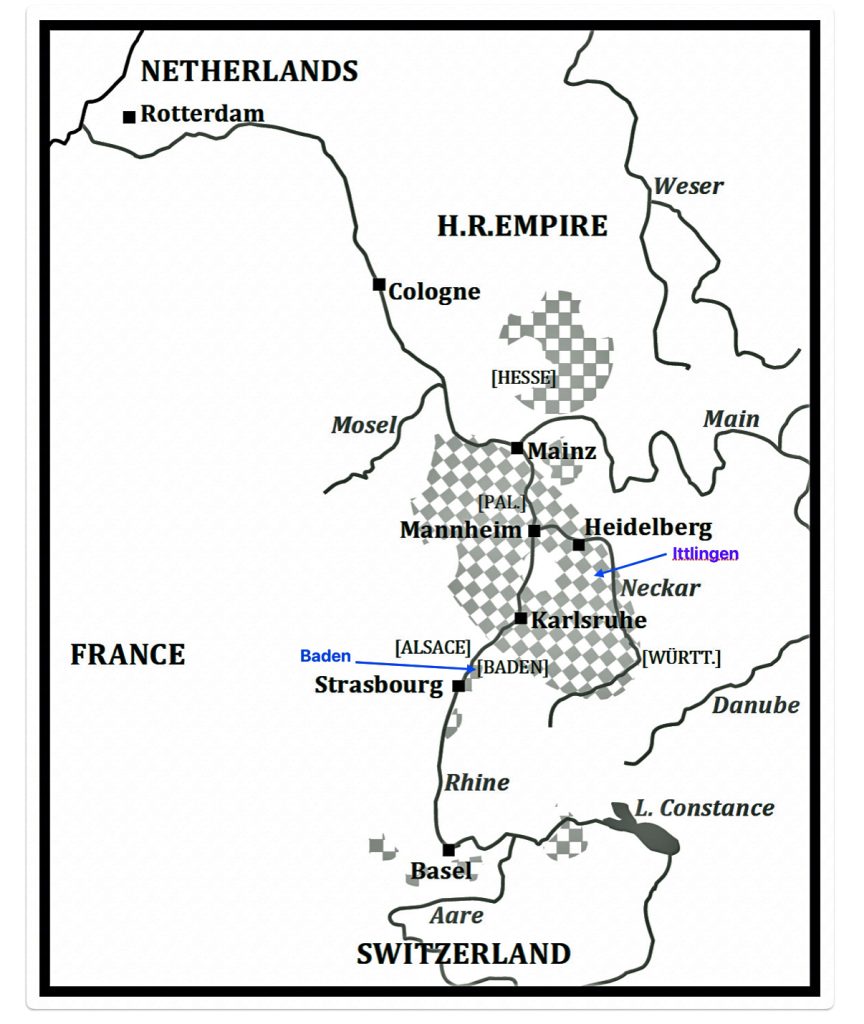

Each of these family branches of the Griffis family originated from areas in the Grand Duchy of Baden. The Sperber and Fliegel families were originally from the Baden and Ittlingen [12] areas of the Grand Duchy of Baden respectively (see Map One). [13]

Map One: A Portion of the Grand Duchy of Baden 1846

The distance between the two towns is approximately 103 kilometers or 64 miles based on current road networks in Germany. (see Map Two). While the Fliegel and Sperber families were about 65 miles away from each other, their families experienced similar socio-economic conditions and their prior generations were probably aware of the experiences of past generations of families that lives nearby that migrated to America.

Map Two: Contemporary Location of Baden-Baden and Ittlingen in Germany

Source: Google Maps https://www.google.com/maps/place/74930+Ittlingen,+Germany/

“The Rhine lands shared many fundamental characteristics, but they were not a political entity. The many major and minor states and principalities involved were all pulled together by the Rhine River and its tributaries, especially the Main, Neckar, and Mosel. This riverine network was one of the chief arterial systems of Europe along which coursed traffic, trade, communication, and population movements. The Rhine bound many different places together: poor mountainous areas and rich valleys; scattered farms, hamlets, and compact villages; and many towns and several cities. A patchwork of more than 350 distinct territories (lehensrechtliche Herrschaften) made up the greater Rhine valley, only some of which were part of larger political units.” [14]

The lower Rhinelands has a rich history of change and movement of people despite being an agrarian society in the 1600’s through the mid 1800’s. Given the geographical importance of this ‘riverine network’, the German Rhine lands and, in particular the Baden area, repeatedly became the center of population change due to the vagaries and influence of the weather on an agrarian economy, the effects of war and the feudal structure of of the agrarian society.

Wars had a significant impact on Baden during the sixteenth, seventeenth, and early eighteenth centuries. Some periods of conflict include:

- The Effects of the Reformation: The Reformation caused upheaval in Baden, leading to a split between Catholic and Protestant regions. By the early 17th century, much of the north had become Protestant, while the south remained Catholic. [15]

- Thirty Years’ War: This devastating conflict from 1618 to 1648 had enormous consequences for the area that eventually became the Grand Duchy of Baden. Marauding armies ravaged the countryside, leading to a significant loss of population and destruction of many towns. [16]

- War of Palatine Succession (1688-1697): Baden suffered heavily during this war, which was part of the broader European conflicts of the time. During this war, French troops under Louis XIV ravaged the Rhenish Palatinate, Baden and Würtemburg, causing significant devastation and leading to many Germans emigrating from the region. The French aimed to deny enemy troops local resources and prevent them from invading French territory, resulting in widespread destruction in the region. [17]

These wars and other conflicts in the 1700s resulted in population loss, destruction of towns, religious divisions and the migration of people within and out of the Baden region. The conflicts reshaped the religious and political landscape of the region, leaving lasting impacts on its society, the movement of people and governance of the area. [18]

Southwestern Germany emerged both as a region of substantial and recurring immigration and as the origin of repeated significant emigration streams. For these reasons, the Rhine lands were an area in which the migration tradition ran strong.

“What remains is something of a culturally defined, rather homogenous zone, a lowland farming region that spread through the river valleys of Baden, Württemberg, the Palatinate and Hesse, within which many communities built the substantial American migratory chains of the first half of the nineteenth century, whilst their neighbours looked on.” [19]

The Grand Dutchy of Baden during the early nineteenth century had a reputation as one of Germany’s most progressive political societies. At the same time it was a Beamtenstaat, a bureaucratic state. It was dominated by a centralized administrative system with career civil servants. From the 1830s it was a liberal German state transitioning from agrarian state comprised mainly of small towns and villages. Since its unification of Baden-Durlach and Baden-Baden, free trade and agrarian reform was fostered as well as education and religious tolerance. [20]

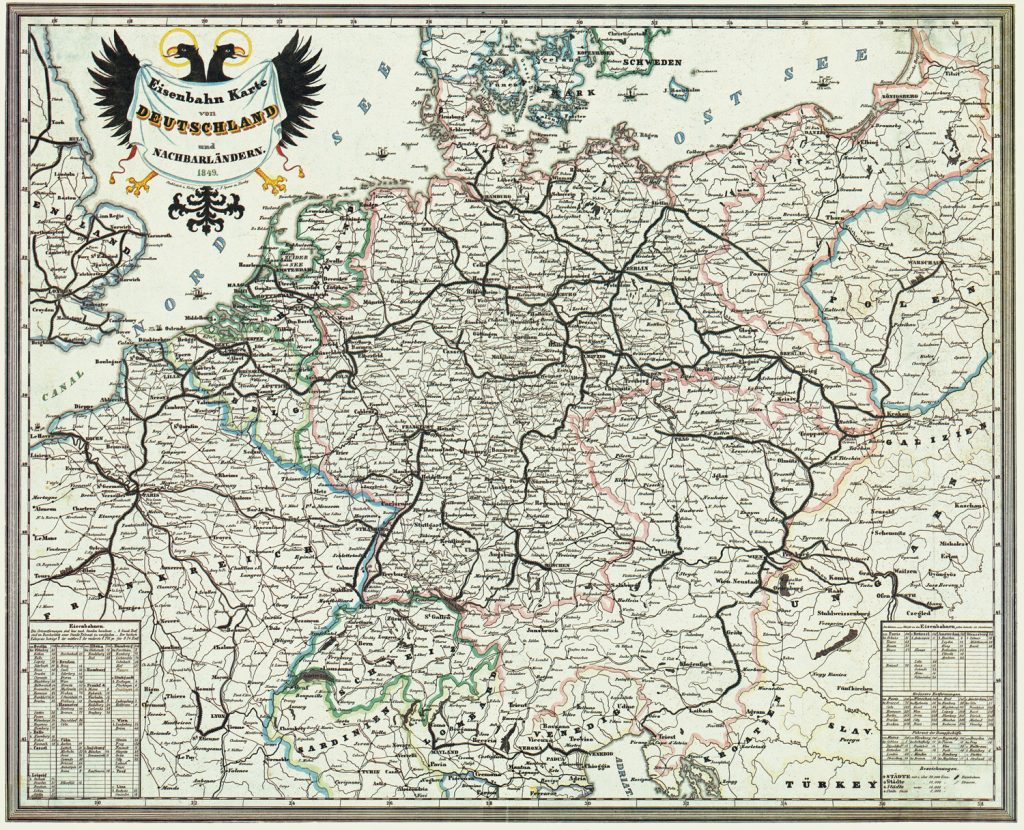

Prior to the 1840s, only a very small fraction of the population lived in places with more than 2,000 inhabitants There was little difference in the growth rates of urban and rural places in the nineteenth century. It was only after the 1850s, the period where the Fliegel’s and John Sperber emigrated, that small cities (e.g. 1,000 to 5,000 in size) started to slightly grow due to the growth of large scale industry and the expansion of the rail system. [21]

Table Two: Percent Distribution of Communities By Size in Baden [22]

| Population Size of Community | 1825 | 1875 | 1900 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under 500 | 48.1 | 42.6 | 43.3 |

| 500 – 999 | 33.2 | 31.4 | 30.2 |

| 1,000 – 4,999 | 18.1 | 25.0 | 25.0 |

| 5,000 – 9,999 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| 10,000 & over | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| Total Number | 1,550 | 1,555 | 1,555 |

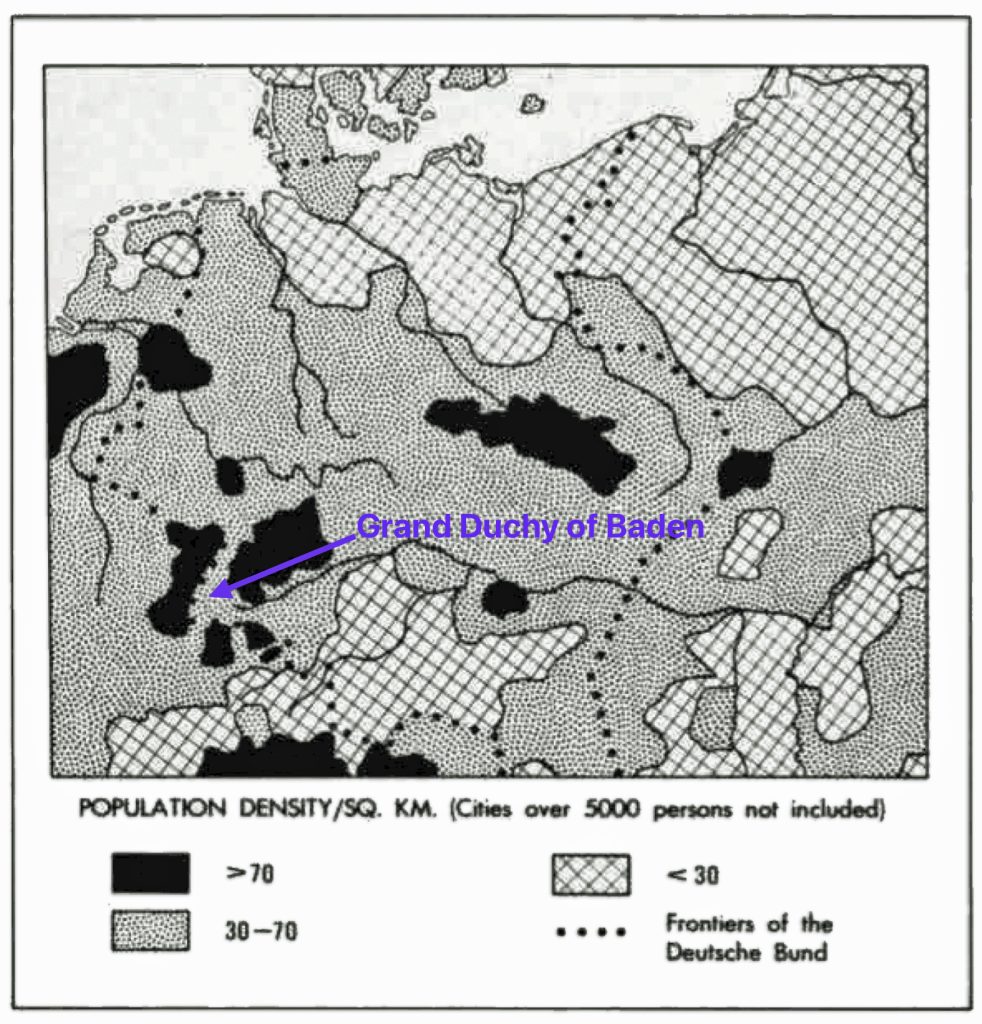

Baden was a more heavily rural area throughout the nineteenth century than were several of the more northern and western states of Germany. As reflected in table two, roughly three quarters of the communities in Baden were smaller than 1,000 inhabitants between 1825 and 1900. In 1825, only 10% of its population was living in places with 5,000 or more inhabitants. The state’s four largest cities (Mannheim, Karlsruhe, Heidelberg, and Freiburg) increased their share of the total population from 7% in 1825 to 20% in 1900. While Baden was for the most part a rural German state with small villages, the population density of the Grand Duchy of Baden was about 60 people per square kilometer (see Map Three) and was similar to most of the states in the Deutsche Bund. [23]

Map Three: Population Density of the German Confederation the Beginning of Nineteenth Century [24]

Baden: A ‘Long Eighteenth Century‘ of American Emigration

The choice of ports to depart and places to settle in America were, to a large extent, the result of relying on knowledge of past migratory practices of relatives, friends, or local villagers. Information gleaned from family and local communities created migration paths over time. John Sperber and the Fliegel’s undoubtably knew from oral history where prior generations of their community migrated to in the Mohawk Valley and to the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania area. [25]

“Following the lead of successful local pioneers, certain areas in the Rhine lands exhibited distinct preferences for a particular American colony or settlement.” [26]

In a society dominated by small towns and villages, horizons were narrow, local sentiments strong and information passed between generations and those you knew. The decisions made by Fliegel family members and John Sperber were not made in a vacuum. Local and regional socio-economic and political factors created a set of unique ‘push’ factors for them to consider emigrating from Baden. Their subsequent journey to American was also influenced by information they may have garnered from local community members who had descendants who migrated to America in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s. Travel agents and brokers, and German publications also provided information that may have facilitated their decisions to emigrate.

“…(W)hen these communities entered serious difficulty, it was the pathways established by their neighbours, by other villages in their districts and parishes, and by members of extended family, that made America the obvious response. The destinations which they sought out were far from coincidental, guided by local knowledge and others leaving from the long-affected emigration communities.” [27]

“German migrants were the only individuals outside of the British Isles that were heavily represented in American migration from colonial times to the close of the nineteenth century, and even at the earliest of stages, in the colonial era, the migration was defined by structural insufficiency in the affected German regions. Rather than being an incidental movement of the religiously persecuted, the early migrants were largely the product of worsening socio-economic conditions interacting with migratory heritage in the German South West. A ‘long eighteenth century’ of American emigration from 1683 to 1817 thus saw substantial links established between that region and the North Atlantic World.“ (emphasis is mine) [28]

The influence of local community factors undoubtedly played a part in the Sperber and Fliegel family’s consideration to emigrate and, particularly, to emigrate to regions of New York state. To name a few:

- the economic and social conditions in surrounding communities where John Sperber and the Fliegel family grew up;

- the previous migratory patterns of individuals from their respective communities;

- the locations in the United states where prior generations and current members of their community settled; and

- their historically preferred modes of inland transportation were all perhaps considered when John Sperber and the Fliegel family migrated to the United States.

“Most ordinary people living in the Rhine lands had to cope with political fragmentation, government regulation in the secular and religious spheres of life, and intermittent periods of economic and demographic instability, but some territories underwent more upheaval than others. … (T)he German Rhine lands repeatedly became involved in war, since their geographic location between hostile parties put them in a difficult and insecure position.” [29]

Their leaving the Grand Dutchy of Baden was undoubtably influenced by the past experiences of German emigrants in the Upper Rhineland area. [30]

Migration, internal, external, and seasonal, was an integral and regular part of a relatively stable social and economic order for Germans in the 1600s through the 1700s, years before the Fliegel family and John Sperber emigrated in the mid 1800s. [31] The Baden area had a rich history of migration reaching back into the late 1600s and 1700s. During periods of war between the French and German states, neutral Switzerland acted as a supplier of goods to the Rhine lands farther north. In peacetime, Swiss laborers and settlers migrated to the war-torn and rebuilding regions of southwestern Germany.

Estimates of the number of Germans who may have immigrated in the 1700’s range from about 65,000 to about 100,000. There are notable years of mass migration of Germans to the North American Colonies in the eighteenth century (1749 to 1752, 1757, 1759 and 1782). At the time of the American Revolution, approximately 225,000 Germans made up about 8 to 9 percent of the total population of the country. According to the first U.S. census in 1790, about a twelfth of the total population was from Germany. [32]

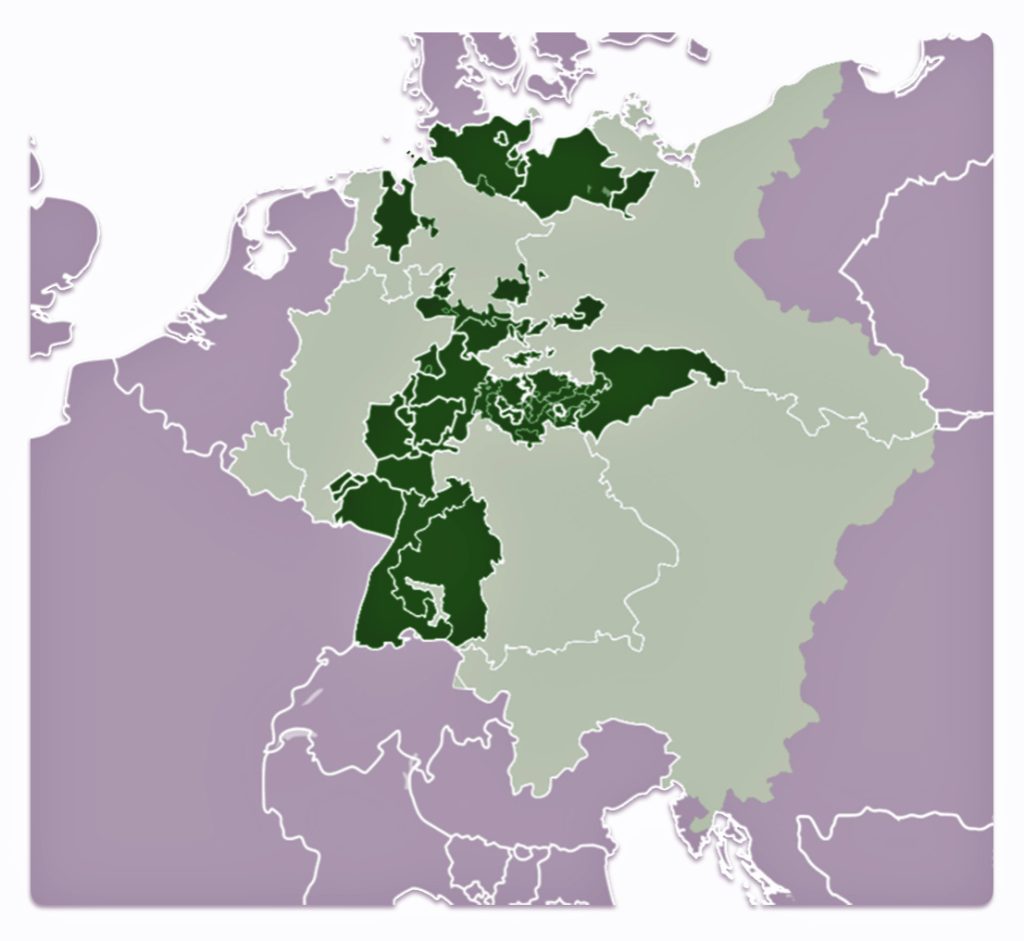

“In the eighteenth century, more than 100,000 migrants left the south-west German regions of the Electoral Palatinate, Kraichgau, Baden-Durlach, and Duchy of Württemberg, as well as neighbouring Alsace and the Swiss cantons, in order to cross the Atlantic.” [33]

The Kraichgau region and Baden Durlach were areas in the eighteenth century where the Fliegel and Sperber familes resided. The Fliegel family lived in the Kraichgau region. [34]

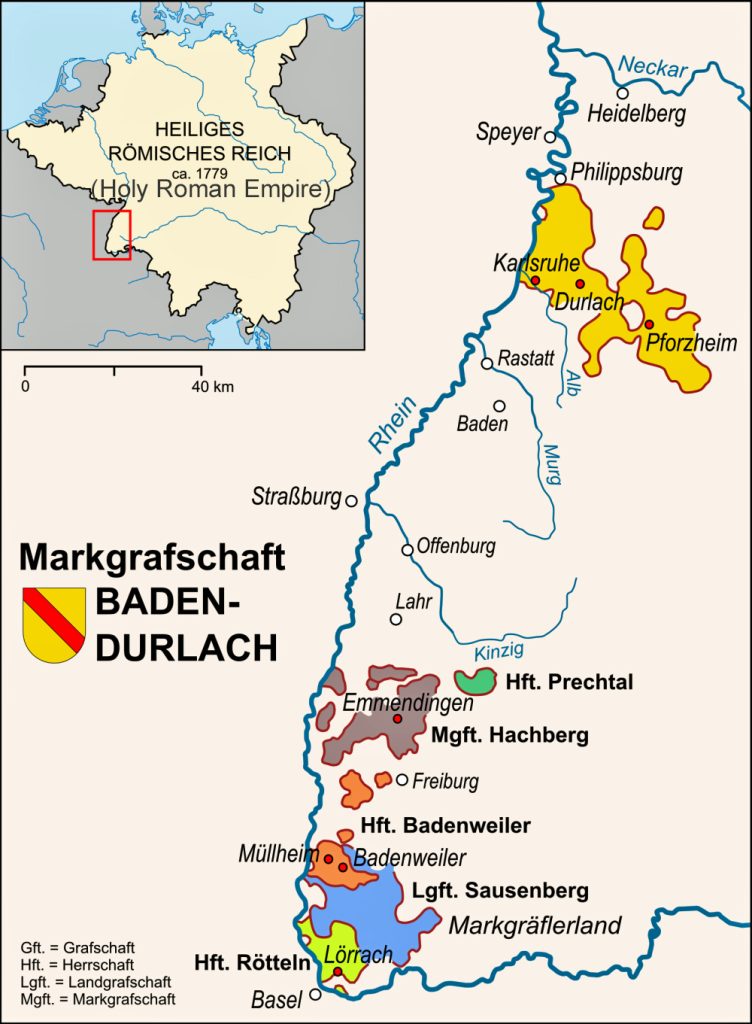

The Margraviate of Baden-Durlach (see maps four and five) was in between the geographical areas where generations of the Fliegel and Sperber families lived. Baden is only about 30 miles southwest from what was the capital of Baden Margraviate Durlach and close to Pfozheim. The Fliegel family lived northeast of Pfozheim, about the same distance of 30 miles.

The movement of the initial wave of German immigrants, the so-called ‘Palantines’, was the result of the British government sending roughly 2,800 – 3,000 German immigrants in the early 1700’s (1709-1710) to the colonies. The Germans from the Rhineland initially immigrated to England on rumors that Britain would provide passage to the American Colonies. In a quandary as to what to do with these German immigrants, the immigrants were sent by the English to the colonies on the proviso that they would be indentured laborers for the production of ‘naval stores’ (the production of tar and pitch in the pine forests of the Hudson valley).

While the term “Palatines” primarily refered to emigrants from the Palatinate region, the actual origins of these eighteenth century migrants encompass a wider array of territories within the Holy Roman Empire. The term was used indiscriminately by the Dutch and English for all emigrants of German tongue. The ‘Palantines’ were Germans from a number of socially and culturally different areas. Many came from surrounding imperial states such as Palatinate-Zweibrücken and Nassau-Saarbrücken, the Margraviate of Baden, the Hessian Landgraviates (Hesse-Darmstadt, Hesse-Homburg, Hesse-Kassel), the Archbishoprics of Trier and Mainz, and various minor counties like Nassau, Sayn, Solms, Wied, and Isenburg. [35]

The Changing Boundaries of Baden

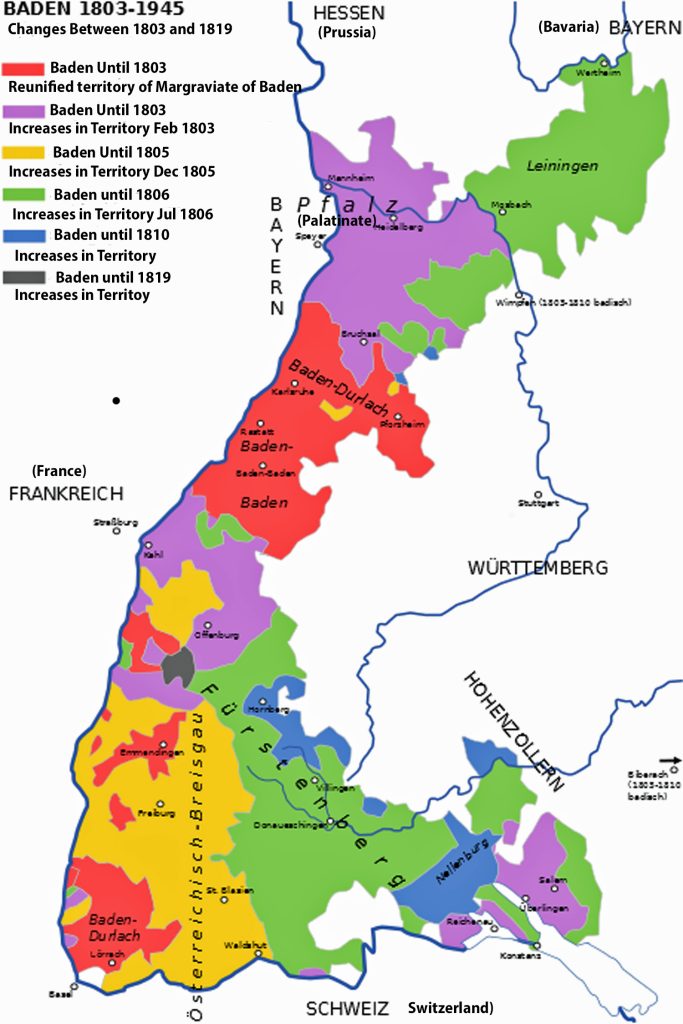

Map Four: Baden Durlach 1789

Map Five: The territorial gains of Baden between 1803 and 1819

The Margraviate of Baden-Durlach (1535-1771) was a territory of the Holy Roman Empire, in the upper Rhine valley. It was formed when the Margraviate of Baden was split was named for its capital, Durlach. The other half of the territory became the Margraviate of Baden-Baden, located between the two halves of Baden-Durlach. Following the extinction of the Baden-Baden line in 1771, the Baden-Durlach inherited their territories and reunited the Margraviate of Baden. The reunified territory was caught up in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, emerging in 1806 as the Grand Duchy of Baden. [36]

Once they got to the colonies, they refused to an agreement to be indentured laborers for the production of naval stores. The English did not enforce their original contract. As a result, the German immigrants settled on the Hudson River, some moved to New York City and New Jersey and others settled to scarcely settled areas of the New York frontier. [37]

Many of these ‘scarcely settled’ areas would eventually be areas that various branches of the Griffis family would settle in the Mohawk valley. Close to 850 families settled in the Hudson River Valley, primarily in what are now Germantown and Saugerties, New York.

By 1745, more than 40,000 Germans lived in the colony, with many settling in towns and villages across New York State. Because of the concentration of Palatine refugees in New York, the term “Palatine” became associated with German. [38]

Emergence of the Redemptioner System

After the 1709-10 “Palatine” movement, the German Atlantic migration quickly developed into a large scale labor migration movement. “By the early 1720s, British captains operating out of Rotterdam found demand for labour in the colonies to be so great that ‘Palatines’ could be taken to America on credit.” [39]

Germans from Baden had a long tradition of migrating to America through the eighteen century and in the nineteenth century. However, the nature and type of immigration patterns for Germans in the eighteenth century were different from those in the 1830s – 1850s.

As reflected in map six, the principal regional sources of eighteenth century German migration were areas that included Ittlingen and Baden.

Map Six: Principal Regions of Eighteen Century South Western German Immigration [40]

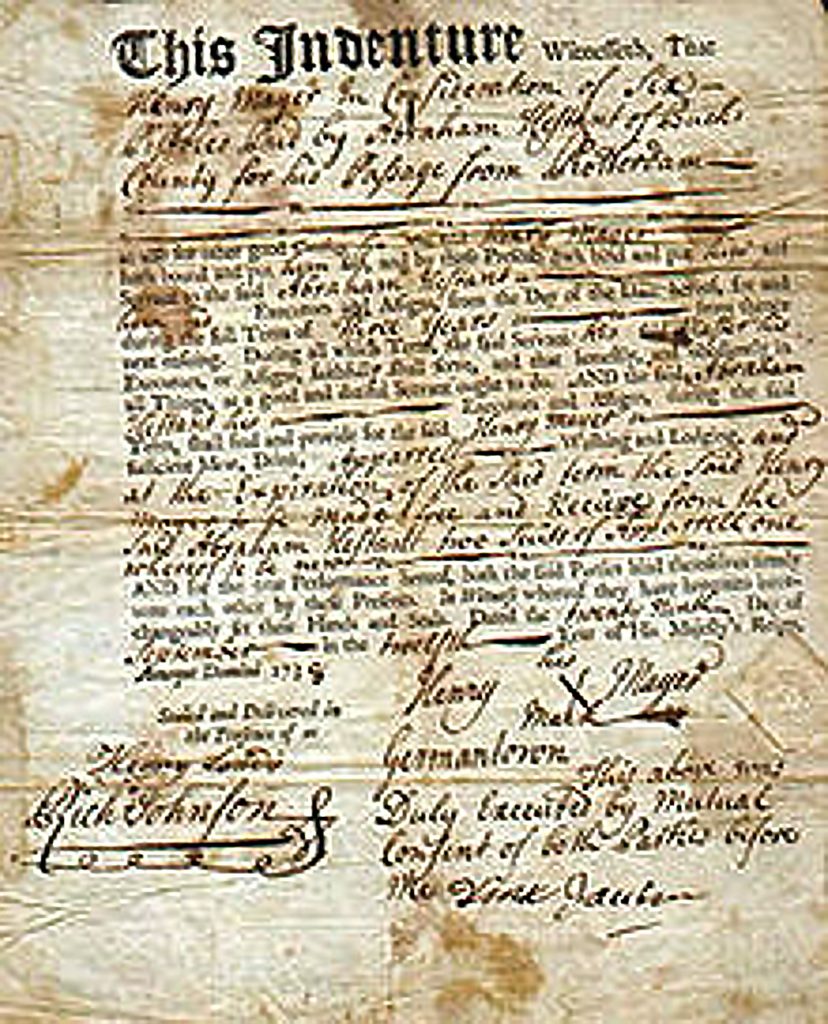

Many of the German immigrants in the eighteenth century and early part of the nineteenth century were part of the ‘redemptioner‘ system. One half to two-thirds of the German immigrants to British Northern America were “Redemptioners” in the eighteenth century. The redemptioner system can be traced from 1728 through the American Revolution and into the 1820s. [41]

The Redemptioner System

An indenture signed by Henry Mayer, with an “X”, in 1738. This contract bound Mayer to Abraham Hestant of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, who had paid for Mayer to travel from Europe. [42]

The redemptioner system was a form of indentured servitude in the American Colonies. The early United States Redemptioners were European immigrants, mostly German, who sold themselves into indentured servitude to pay back the shipping company that funded their transatlantic voyage. They negotiated their indentures upon arrival in America. [43]

Redemptioners typically worked for a period of three to seven years to pay off their debt. The system allowed immigrants to gain passage to America if they could not afford the costs of travel by booking passage on a ship on credit. They were to pay off the credit by entering into a term of service for room and board which generally lasted from the terms of the contract. Their debt was ‘redeemed’ under their contracts and as such, the migrants were known as ‘redemptioners’. [44]

Redemptioners faced challenges such as abuse during the voyage, over charging leading to debt upon arrival, and potential exploitation by ship agents. The redemptioner system was part of a broader group of indentured servitude in the colonies and then early United States. Also included in this group of indentured servants were ‘free-willers’ and King’s passengers (convict servants). The German immigrants largely were part of the ‘free-willers’. Free willers were individuals, also known as free-willers or free-will servants, who voluntarily entered into servitude in the American colonies.

The system involved various regulations and laws to protect redemptioners, such as limiting the term of service based on age and ensuring approved contracts by magistrates. [45]

“The ‘redemptioner’ service quickly became a significant commercial operation. Merchants in Rotterdam provided payloads of German ‘freights’ to ship owners and their captains, who sold the passage costs of redemptioners at a mark-up price in the New World.” [46]

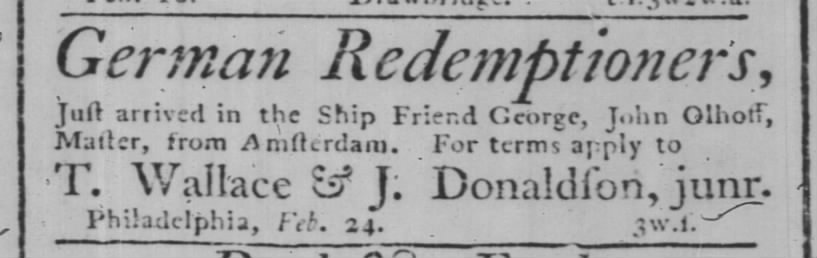

Philadelphia Advertisement for Sale of German Redemptioner

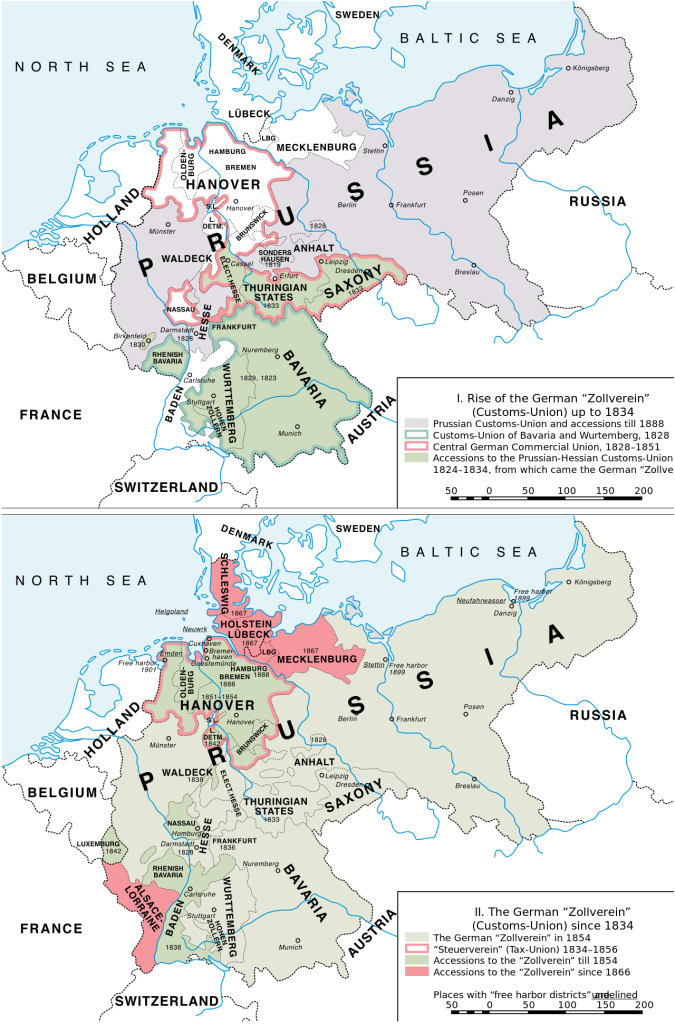

The German redemptioner trade largely ended between 1817-19 during the Rhine Crisis of 1817. The Rhine Crises of 1816 and 1817 refers to a significant migration event where tens of thousands of German migrants traveled down the Rhine River, to European ports at the mouth of the river, in an attempt to reach the United States. Many of these immigrants were poor. [47]

“The critical difference between 1816/17 and the peak of the redemptioner trade between the 1730s and 1760s was that the final episode was entirely ad-hoc, and lacked the organisational oversight of large scale commercial brokers.” [48]

The movement peaked in 1817, with approximately 15,000 immigrants arriving in the U.S. during that year. However, the migration surge eventually ceased by the end of 1819 due to a variety of factors like improved harvests, changes in shipping practices, and legislation that restricted the movement of poorer migrants. Dutch and Prussian legislation enforced in June 1817 played a crucial role in halting the exodus of Germans by requiring migrants to have valid contracts and sufficient cash to gain entry at the border to continue to the Dutch port of embarkation. [49]

In 1816 and 1817, whilst some merchants and boatmen offered to bring passengers directly to a waiting vessel, many recruiters and Rhine river shippers simply offered to take people into the Netherlands, where they might then try their luck in seeking passage with any captain who would take them. Some recruiters offered tickets for vessels in Amsterdam that didn’t even exist. Because the border enforcement and legal framework of transit migration had atrophied in the intervening generations, this speculative approach ‘worked’ (at least for Rhine boatmen) until active measures were taken in June 1817. [50]

European states that had ports of embarkation to America instituted transit laws to make it difficult for insolvent or poor emigrants to reach port cities. American conditions in immigrant trade in 1818–19 made it a commercial risk to receive the immigrants. The timing of border legislation in mid-June 1817 appears to be the most immediate cause for the cessation of departures out of Baden and Württemberg, [51]

“The aftermath of the 1816/17 migration of Germans to Philadelphia fundamentally re-shaped the future of migration between German Europe, indeed continental Europe, and the United States. It was this episode that brought an abrupt end to the redemptioner system of migration between the German states and North America, and which ultimately paved the way for competitive passenger systems of the 19th century.” [52]

Post 1819, the cost of travel to the United States was a key determinator to even consider the ability or possibility to emigrate. Cost also was a major factor concerning what port to embark and where to end up in America. After the demise of the redemptioner system of paying the costs of immigration, there was no incentive for ship brokers, to carry redemptioner labor.

When European emigration began to surge again in the 1830s, American and European laws ensured that there would be no opportunity to carry passengers on credit. This tightened access to major ports to those emigrants that had the ability to pay for their emigration at the point of departure .

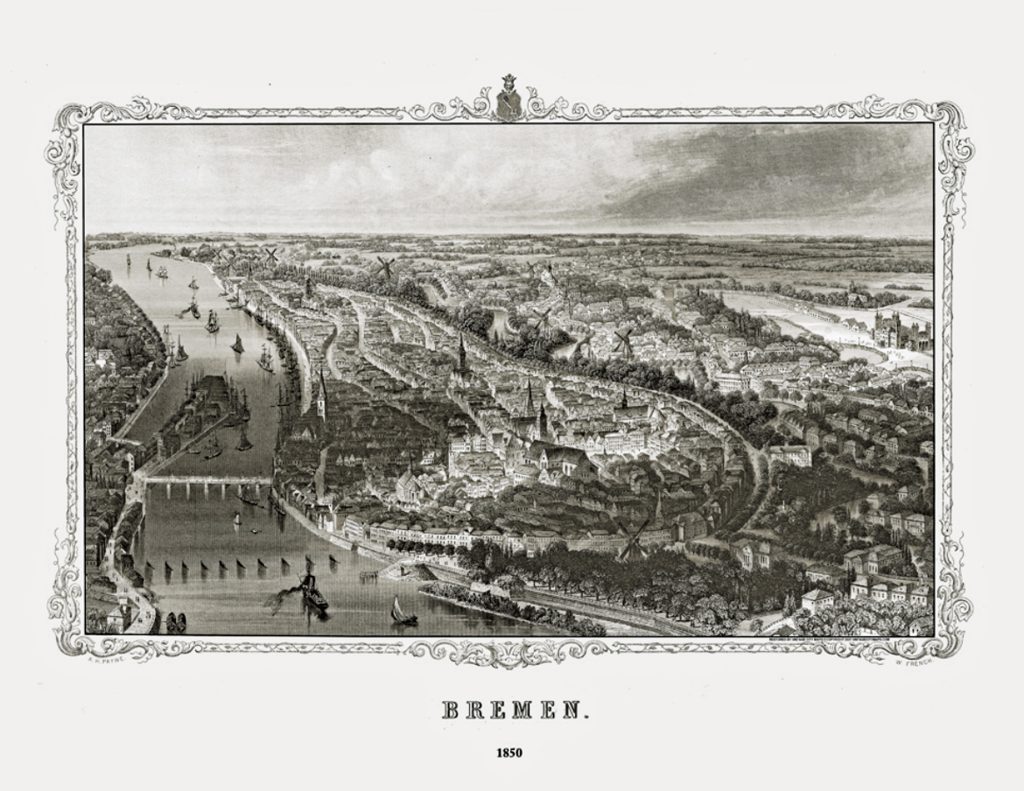

“Ending the supply of poorer migrants, and thus redemptioners, was the first and most instantly notable effect. The permanency of this change would be ensured by wider developments in US-European shipping. Regulation of poorer migrants (pursued in Hamburg, as well as the Low Countries, after 1817), alongside commercial developments in the Atlantic during the 1820s, diverted future migrants to alternative points of departure, and into a separate model of migration. Key to that model was an increased frequency of departure to the United States from other European ports, whose regular trade in bulk commodities allowed the introduction of the packet line, and a regular timetable of departures. This increased frequency led to a lower price for passage fares. Prices remained high enough to keep the poorest migrants excluded from migration, but low enough that when emigration again became economically desirable, small peasants and artisans could find passage from ports such as Le Havre, which traded with the United States in cottons, and Bremen, which had cultivated a strong trade in American tobacco.”[53]

The Cost of Travel

“If legal parameters (of European states and the United States) made sure that only paying customers could begin the migration process, the onus for business became the sale of valid tickets in the hinterland, at or near the point of departure – a critical model in 19th century emigrant shipping.” [54]

Moving to the United States was not a cheap endeavor for Germans during the middle of the nineteenth century. Few Germans could afford to emigrate anywhere beyond the east coast. Fares to ports more distant than the east or south coasts of the United States were

much larger. The technology of ocean travel was not sufficiently advanced to reduce fares to other ports to an affordable level for most individuals. [55]

The most common destination for German emigrants was New York City. Getting there was expensive for many Germans. “(T)he further west one traveled-and thus the longer the voyage-the higher the fare. New Orleans was two to five Thalers more expensive, Galveston another three Thalers … .”[56]

“Most German emigrants had incomes no lower than those earned by the lower middle class, creating an emigrant population from German states that was positively self selected in the 1840s and 1850.” [57]

The fares were generally higher fares from Le Havre, Antwerp, and Rotterdam than from Hamburg or Bremen. German newspaper listings in the mid 1800s for the fares from the non-German cities included the cost of getting from a city in the interior of Germany to the port city. [58]

“The cost of the voyage fluctuated greatly. Until the middle of the century the German ships were alone in furnishing steerage passengers with the necessities of life; on all other ships they were required to provide themselves with everything except fire and water, so that the price paid to the master of the vessel was not the largest part of the emigrant’s expenses.” [59]

For those who could come close to raising the required funds, paying for the trip to the port and the voyage was easier if they had an inheritance or could liquidate all their goods and property before leaving the continent. Even for individuals that were relatively well off, paying for just one transatlantic fare would have cost between one-third and one-half of a yearly income. While individuals could afford to emigrate at these prices, it was near the limit of what was affordable. [60]

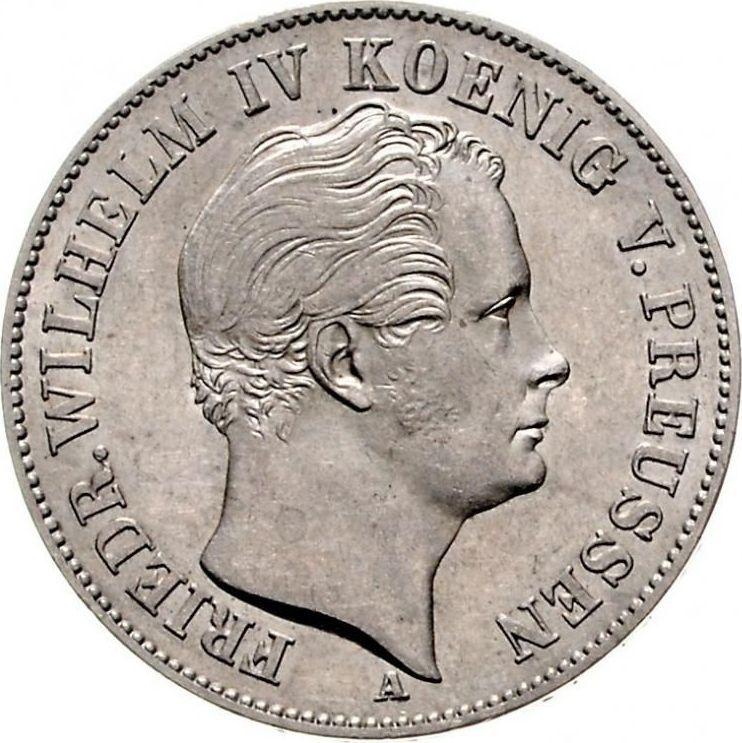

A Thaler was worth approximately $0.70. Historical exchange rates for this time period indicate 5 francs were equivalent to 1 US dollar. [61]

“For an adult traveling in steerage on a sailing ship, the average fare was 33 to 35 (Prussian) Thalers, about 23 dollars. … These fares explain why most of the Germans who emigrated were positively self selected, that is, they were not poor farm laborers or servants but were somewhat better off. … Around 1850, even a master farm laborer in the Rhine area earned only about 60 Thalers per year in cash in addition lo various in-kind goods, worth probably at least another 20 Thaler.” [62]

“(In 1845) the charge was twenty dollars from Bremen, twenty-three from Hamburg, including food from both ports; and thirteen or fourteen without food from Antwerp, Rotterdam, and Havre. In i856 it had risen to thirty dollars from the German cities.” [63]

The fares do not include the costs of getting to a port of embarkation and other related costs of travel. These additional costs would make it even more difficult for poorer Germans to emigrate. Due the average cost of travel, most of the Germans who emigrated during John Sperber and the Fliegel family’s time were not poor, destitute farm laborers, artisans or servants but were somewhat better off.

A Prussian Thaler

The Prussian Thaler (sometimes referred to as the Prussian Reichsthaler) was the currency of the Kingdom of Prussia until 1857. [vv] Images of the coin are from Thaler 1850 A (Prussia, Frederick William IV), Coinstrail, Photo by: Emporium Hamburg Münzhandelsgesellschaft mbH https://coinstrail.com/catalog/prussia/frederick-william-iv/silver-thaler/6491aea9311f1fbf0920e4ef

“According to a tabulation of the financial resources of immigrants arriving at New York during the last five months of 1855, … Bavarians with $76, were somewhat above average , and the natives of Baden and Hesse both slightly surpassed the Prussian average of $61 per capita. Thus it hardly appears that southwest Germans are stranded in the ports because of poverty.” [64]

Government Subsidized Emigration

In the early 1850s, the Grand Duchy of Baden experienced instances of state-subsidized emigration. Baden saw subsidized emigration as a way to alleviate social pressures and prevent uprisings by reducing the number of poor people in the country. This policy was also seen as a way to save on welfare costs.

While emigration began to pull on many of the local villages in Baden as a result of the crop failures of the late forties, during 1852, the trickle from various villages of emigrants became a flood. By 1852, the rural situation in Baden was desperate. During what was known as the ‘winter of hunger’ in late 1851, the wine growing regions of Baden were impacted along with other food growing areas. Local village councils as well as the state began to support and fund emigration to America to alleviate the economic pressures on the Baden economy. [65]

The agrarian crisis of mid-century proved to be specifically acute in the southwest region Because of the density with which American migratory chains were laid across the region from the past, the resulting movement was huge. [66]

“Subsidized emigration reached its greatest extent in Baden where it evolved from a popular strategy of relieving local welfare costs to an attempted strategy of social management. Given the particularly virulent nature of the uprising in Baden in 1848, indeed, the Grand Duchy might arguably be regarded as the core of events, state authorities were favourable to the idea of thinning the population to take pressure off the land, and to ensure lasting social and economic peace. In 1850 54,090 Gulden was spent in Baden to help subsidize emigration. By 1854 the amount had risen to 516,688 Gulden, although only a tenth of that came directly from the government, its contributions having crested and fallen in just a five-year window. … At its mid-century peak, subsidies may have supported around 20% of the emigration from Baden.” [67]

Chain Migration: Influence of Family and Acquaintances

Chain migration refers to the process where immigrants from a particular town or region follow others from that area to a specific destination, often based on family or community ties. The definition of the term can vary. Its narrowest definition would describe the movement of different family or community members within a specific geographical area of origin to a specific destination. This movement was based on information obtained from family or community members at the destination or from past generations that made the trek to the destination. This pattern of migration was particularly prominent among German immigrants to the United States in the 19th century.

“Except for the great leap of faith in crossing the ocean, German immigrants tried to minimize risk by drawing upon personal ties and community resources to cushion their entry into a new society and economy.” [68]

“It is clear that immigrants from Germany and other parts of Europe did not scatter randomly across the American continent. Instead they formed very pronounced ethnic concentrations in certain areas.” [69]

The configuration of the American transportation infrastructure played a major role in where immigrants would likely settle. In addition, social networks that developed between previous immigrants and potential immigrants were an important factor in immigration. Wherever a group of German immigrants established roots in America, a concentration of immigrants usually persisted for several generations. [70]

Information from previous migrants or the prospect of migrating to where other family members had migrated could change in economic terms how a potential migrant viewed the expected return and risk associated with economic prospects in America. [71]

“Much more decisive for the migration process than agents, guidebooks, or emigration societies were families or lone individuals, sometimes accompanied by relatives, friends, or neighbors, but without a common treasury or any formal organizational framework. The risks involved in such an undertaking were greatly reduced through chain migration, which meant the immigrant had the choice of an initial destination where one already had personal contacts, family, and friends who could provide temporary lodgings, arrange a job, and generally ease the shock of confronting a new society, culture, and economy” [72]

Perhaps Catherine Fliegel’s positive experiences in the new land and the knowledge of the hardships her family faced at home were conveyed in letters to her family back in the Grand Duchy of Baden, similar to what many other German immigrants did after migrating to the United States. Sending letters back and forth between the United States and the German states was not as difficult as imagined.

“With millions of letters arriving every year, modernised transportation networks conveying people cheaply across the Atlantic in days, and with every German region and locality knowing friends, neighbours and relatives who had set the precedent, the decision to migrate in the second half of the century was not what it had been in the first.” [73]

Immigrant letters were focused on maintaining relationships with individuals that were important community ties and part of their identity from their old world. Immigrant letters often focused initially on their first project of material goals and establishing a life in the new world. Then they may moved on in their correspondence to the second project of continuity of service with their family and community: getting relatives or friends to join them by providing experienced advice on planning and occupational opportunities.

When American immigration authorities in the early twentieth century began to pose the question of whether arriving immigrants were coming to join relatives or friends, only 6 percent of all newcomers said no. Over one third of all Germans during this era traveled on ship’s passages that had been prepaid by someone in America.

“Whether one does immigration history by the numbers or by the letters, the results show a striking congruence. The decision to emigrate was very much a bottom-up decision. Private sources of information, above all immigrant letters, were much more influential than any public sources, be they guidebooks or state immigration agencies, in determining immigrants’ destinations.” [74]

As stated previously, the Fliegel family’s planned exodus from Germany is a classic example of ‘chain migration’, relying on the prior experience of their daughter Catherine Fliegel. While we do not have any letters between the Fliegel family members to document this communication. It obviously is beyond coincidence that the remaining members of the Fliegel family would relocate seven years later to the Gloversville – Johnstown area.

For John Sperber, the reasons why he ended up in Gloversville are harder to explain. The lack of evidence to the contrary, John Sperber traveled alone to America. It is possible that he ‘took off for unknown opportunities’ with no information from relatives, friends, or hearsay from his local community. It is possible but not likely.

As stated, Germans from his specific geographical area in Baden had a long tradition of migrating to America through the eighteen century and in the nineteenth century. While the route getting to America may have been different, there may have been a strong likelihood to follow a ‘guiding star’ of tradition (oral or written) that lead John Speber to the ‘Palantine’ area along the Mohawk River in New York state.

“The Rhine and the Hudson ! The historic river of Europe and the historic river of America! How closely associated are they in the minds of those who dwell in the lovely valley in which we are met today !” [75]

Sources

Feature banner: An amalgam of (1) a painting by Johann Jakob Aschmann, Ansicht von Baden, Staatsarchiv des Kantons Aargau , Wikimedia Commons, 1848 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aschmann_Baden_1800.jpg ; (2) an 1846 Map of Baden: Radefeld, Carl Christian Franz,, Gross Herzogthum Baden. Na(c)h den bessten Quellen entw. u. gez. vom Hauptm. Radefeld. 1846. Stich, Druk und Verlag des Bibliographischen Instituts zu Hildburghausen, (1860) Page 38 (see below); and (3) an 1850 letter from a German Immigrant to his family From Jakob Sternberger’s first letter home to family and friends, pp. 6-7, Nov. 1850 [Transcription of entire letter, Nov. 1850] Examples of Letters and Old German Script, Max Kade Institute for German-American Studies, University of Wisconsin–Madison https://mki.wisc.edu/library-archive/scanned-images-from-the-mki-archives/examples-of-letters-and-old-german-script/

[1] While many in America and Canada can trace their ancestry from family members that emigrated from Ireland or Germany in the mid 1800s or Italy and Eastern European countries in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the major works of a number of historians who wrote about immigration during this time period remain essential reading to gain an understanding of European immigration.

What is exciting to witness is the emergence of scholarly historical studies that analyze macroscopic historical trends with microscopic or local historical data that is similar to genealological approaches.

See the following for a good overview of the various approaches used to understanding German immigration.

Rudolph Vecoli, European Americans: From Immigrants to Ethnics, Section I : Immigrants, Ethnics, Americans, Cleveland Ethnic Heritage Studies, Press Books, Cleveland State University 1976. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/ethnicity/chapter/european-americans-from-immigrants-to-ethnics/

James Boyd in his Introduction to his PhD Dissertation , The Limits to Structural Explanation, provides a good overview of the historical approaches that have been used for explaining German migration to America, see:

James D. Boyd, An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

Helbich, Wolfgang. “German Research on German Migration to the United States.” Amerikastudien / American Studies, vol. 54, no. 3, 2009, pp. 383–404. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41158447

Günter Moltmann, “Migrations from Germany to North America: New Perspectives.” Reviews in American History, vol. 14, no. 4, 1986, pp. 580–96. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2702202

[2] James D. Boyd, An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, Page 159 https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

[3] “The Atlantic migration … (after 1816/1817)… was conducted by different models and networks than in the previous century. … (T)he majority departed from ports such as Le Havre, Bremen, Liverpool, and latterly Hamburg. New logistical networks, migration laws, and pronounced subsistence crises quickly brought more German regions into this newly expansive Atlantic migration.” See the following for an explanation

James Boyd, The Rhine Exodus of 1816/1817 within the Developing German Atlantic World, The Historical Journal, vol. 59, no. 1, 2016, Page 105. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24809839

[4] James D. Boyd, An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, Page 114 – 115 https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

[5] A common definition of chain migration is the social process by which immigrants from a particular area follow others from that area to a particular destination. The destination may be in another country or in a new location within the same country.

MacDonald, John S.; MacDonald, Leatrice D. (1964). “Chain Migration Ethnic Neighborhood Formation and Social Networks”. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 42 (1): 82–97. doi:10.2307/3348581

Wegge, Simone A. “Chain Migration and Information Networks: Evidence from Nineteenth-Century Hesse-Cassel.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 58, no. 4, 1998, pp. 957–86. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2566846 .

[6] Walter Kamphoefner posited a list of what he called ‘tendencies’ that reflect the characteristics of individualist versus chain migrant.

Kamphoefner’s Migration Typology

| ‘ Characteristics ‘ (This is My Description ) | Individualistic | Chain Migrants |

|---|---|---|

| Migratory Influence | Pull influences | Push influences |

| Family unit of migration | Single | Family |

| Age Demographic | Young | Broader Age Distribution |

| Sex Demographic | Male Predominance | More Balanced Sex Ratio |

| Destination | Urban | Rural |

| Period of Migration | More in Areas & Times of Light Emigration | More in Areas & Times of Heavy Emigration |

| Socio-Economic Status | Higher Wealth; Education | Lower Wealth; Education |

| Ease of Assimilation | Anglo-Conformity; Assimilation | Cultural Pluralism; Acculturation |

Source: Walter D. Kamphoefner, The Westfalians: From Germany to Missouri, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press 1987, Page 1989-193

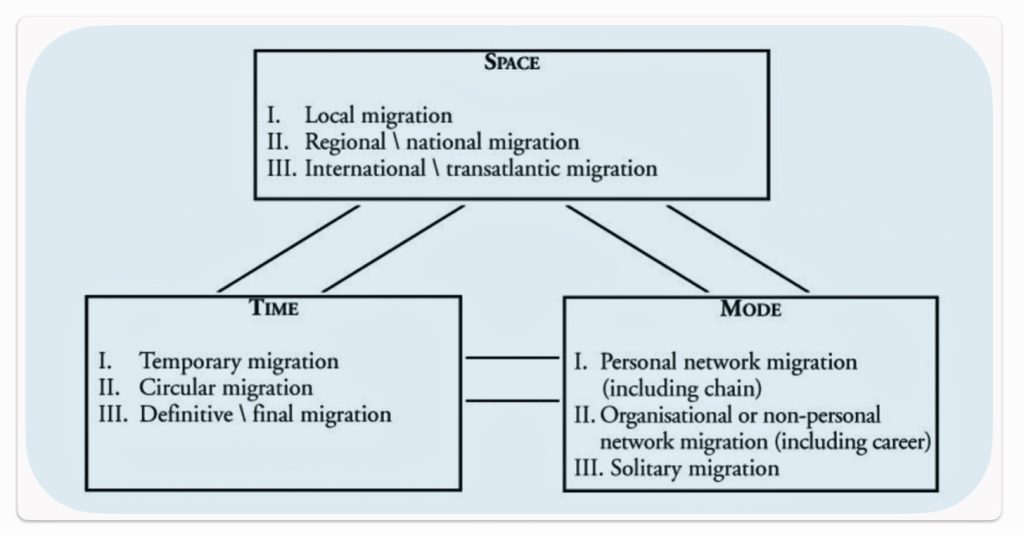

A more recent study has posited a typology of migration in general. The researchers propose to distinguish between at least three separate but interrelated dimensions of migration, each with its own typology.

Lesger, Lucassen, and Schrover Typology of Migration

In their topology of defining migration, they clarify mode of migration. “Personal network migration is primarily based on personal contacts, whether they are shaped as a chain or as a web, or whether they are forged at the level of the family, the village or the region. In all cases people move because they are informed (and often helped) by people they know or know of. Organisational migration (or non-personal network migration) resembles Tilly’s definition of career migration, but our typology is not restricted to elites or (highly) skilled immigrants. Artisans, journeymen and unskilled workers, who move within a guild-like tramping system also fit into this category. Organisational migration includes German journeymen bakers in Amsterdam and apprentices in crafts and trade. Non-network migration refers to immigrants (and their families) who have only a general knowledge of the opportunity structure in a certain destination, upon which they make their decision to move, without having personal contacts at their destination. Information about their distant destination will in most cases be transferred at the personal level, but in contrast to (personal and non-personal) network migration, the decision to move does not primarily depend on the expected support of specific social and professional networks. Typical examples of this type are unskilled workers in the transport sector, or female domestics, who tried their luck in Rotterdam, because it was common knowledge that this large port city offered ample opportunities for employment. Neither organisational nor non-network migration normally lead to massive out-migration from specific places or to concentrated ethnic settlement at specific destinations.”

Lesger, Clé, Leo Lucassen, et Marlou Schrover., Is there life outside the migrant network? German immigrants in XIXth century Netherlands and the need for a more balanced migration typology, Annales de démographie historique, vol. no 104, no. 2, 2002, pp. 29-50. https://www.cairn.info/revue-annales-de-demographie-historique-2002-2-page-29.htm?contenu=bibliographie

[7] Marcus Lee .Hansen, The Atlantic Migration 1607-1860. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, Page 252

[8] The political uprisings in 1848 in Baden were largely in the southern region of the Grand Duchy of Baden. The Fliegel family resided in the northeastern part of the state. John Sperber’s family lived in the central portion of the state.

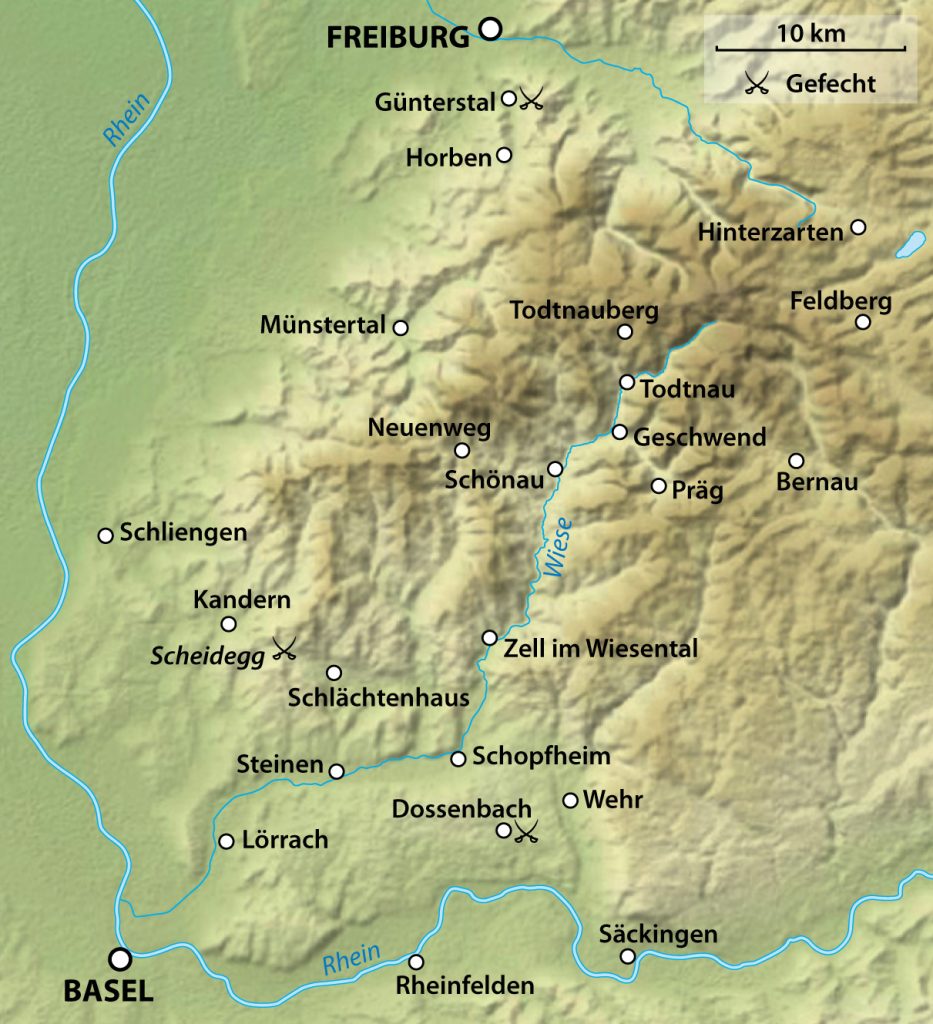

Location of Sperber and Freigel families in relation to the 1848 Political Uprisings

It was in the extreme south of Baden, where Friedrich Hecker was to launch his 1849 coup attempt. “It was this abortive putsch, it is observed, which created the irreparable breach between the government and the democratic opposition in Baden, culminating in May 1849 in the flight of the monarchy and the establishment of a short-lived republican regime.”

Ralph C. Canevali. “The ‘False French Alarm’: Revolutionary Panic in Baden, 1848.” Central European History, vol. 18, no. 2, 1985, pp. 119–42. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4546040

Map Showing Important Places in 1848/49 Revolution in Baden

See also:

Baden revolution, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 9 June 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baden_Revolution

Lee, Loyd E. “Baden between Revolutions: State-Building and Citizenship, 1800-1848.” Central European History, vol. 24, no. 3, 1991, pp. 248–67. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4546213

W. D. Kamphoefner, The Westfalians: From Germany to Missouri, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press 1987, Page 16-18; 59

[9] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Page 284 – 285

[10] James D. Boyd, An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, Page 157 https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

[11] James D. Boyd, An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, Page 156 https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

[12] “From 1355, Ittlingen was a possession of the Lordship of Gemmingen [de]. Their rule ended in 1806, when the Gemmingens’ properties were mediatized to the Grand Duchy of Baden. Ittlingen was assigned on 22 June 1807 to Oberamt Gochsheim [de], the only such district in Baden. On 24 July 1813, Ittlingen was assigned to the district of Eppingen. “

Ittlingen, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 8 February 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ittlingen

[13] The map is from an 1846 Map of Baden: Radefeld, Carl Christian Franz,, Gross Herzogthum Baden. Na(c)h den bessten Quellen entw. u. gez. vom Hauptm. Radefeld. 1846. Stich, Druk und Verlag des Bibliographischen Instituts zu Hildburghausen, (1860) Page 38

[14] Marianne S. Wokeck, Trade in Strangers: The Beginnings of Mass Migration to North America, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999, Page 28

[15] Baden History, FamilySearch,Wiki, FamilySearch, This page was last edited on 14 June 2022, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Baden_History

[16] Baden History, FamilySearch Wiki, FamilySearch, This page was last edited on 14 June 2022, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Baden_History

Baden Military History, FamilySearch Wiki, FamilySearch, This page was last edited on 8 December 2022, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Baden_Military_History

[17] Baden History, FamilySearch Wiki, FamilySearch, This page was last edited on 14 June 2022, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Baden_History

Baden Military History, FamilySearch Wiki, FamilySearch, This page was last edited on 8 December 2022, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Baden_Military_History

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Palatinate”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 18 Jul. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Palatinate

[18] “The War of Spanish Succession (1701–14) hindered recovery from the invasion of Louis XIV’s troops into the Rhine lands. The severe winters of 1708/ 9 and 1709/ 10, which destroyed many of the fruit trees and vines, brought famine and showed that the economic base in the German Rhine lands had been eroded so much that people had little hope for recovery—a decline that contributed to mass emigration. The 1730s saw the War of Polish Succession (1733–38), the end of which was marked by two bad years that culminated in European-wide famine (1740–41). During the War of Austrian Succession (1741–48), Switzerland reported bad harvests in 1745 and 1749.”

Marianne S. Wokeck, Trade in Strangers: The Beginnings of Mass Migration to North America, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999, Page 38 (Kindle version)

Otterness, Philip, Becoming German: The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004, Pages 9 – 18

[19] Boyd, James D., An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf Page 191

[20] Lee, Loyd E. “Baden between Revolutions: State-Building and Citizenship, 1800-1848.” Central European History, vol. 24, no. 3, 1991, Pages 248–49. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4546213 .

[21] Goldstein, Alice. “Urbanization in Baden, Germany: Focus on the Jews, 1825-1925.” Social Science History, vol. 8, no. 1, 1984, pp. 44. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1170980

Reulecke, Jürgen and Jürgen Reuleke. “Population Growth and Urbanization in Germany in the 19th Century.” Urbanism Past & Present, no. 4, 1977, pp. 21–32. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44403540

[22] Statistics were obtained from Table 1 in Goldstein, Alice, Page 50

[23] Goldstein, Alice, Page 44

[24] Map is from Figure 1 from Jürgen and Jürgen Reuleke. “Population Growth and Urbanization in Germany in the 19th Century.” Urbanism Past & Present, no. 4, 1977, pp. 21–32. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44403540 . Page 22

[25] There are a number of scholars that have taken a different historical look at the various immigration waves of Germans in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Rather than treat each immigration wave as separate areas of analysis, they have viewed the interrelatedness of the immigration waves at the regional or national levels. They have also incorporated local geographical levels of historical evidence (village level data) to demonstrate the existence of ‘chains’ of migration.

“The conditions in specific communities from which migrants came; the previous migratory patterns of those communities; how, why and where their migrants came to settle; the skills and work the migrants performed, and even their preferred transportation, needed to be examined collectively, in order to explain their actions and truly understand migratory phenomena.”

“Understanding the German emigration to America in the nineteenth century requires an understanding of particular conditions at the local level, and how these conditions related to a wider German context. … closely examine micro-level conditions, and place those conditions into a wider context.”

James D. Boyd, An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, Page 157 and 209 https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

See the following for examples:

James Boyd, The Rhine Exodus of 1816/1817 within the Developing German Atlantic World, The Historical Journal, vol. 59, no. 1, 2016, pp. 99–123. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24809839

Marianne S. Wokeck, Trade in Strangers: The Beginnings of Mass Migration to North America, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999

Moltmann, Günter. “Migrations from Germany to North America: New Perspectives.” Reviews in American History, vol. 14, no. 4, 1986, pp. 580–96. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2702202

Helbich, Wolfgang. “German Research on German Migration to the United States.” Amerikastudien / American Studies, vol. 54, no. 3, 2009, pp. 383–404. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41158447

Kamphoefner, Walter D. “Immigrant Epistolary and Epistemology: On the Motivators and Mentality of Nineteenth-Century German Immigrants.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 28, no. 3, 2009, pp. 34–54. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40543427

Grubb, Farley. “German Immigration to Pennsylvania, 1709 to 1820.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 20, no. 3, 1990, pp. 417–36. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/204085

Bergquist, James M. “German Communities in American Cities: An Interpretation of the Nineteenth-Century Experience.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 4, no. 1, 1984, pp. 9–30. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27500350

Glaser, R., Himmelsbach, I., and Bösmeier, A.: Climate of migration? How climate triggered migration from southwest Germany to North America during the 19th century, Clim. Past, 13, 1573–1592, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-13-1573-2017 , 2017

Wegge, Simone A. “Chain Migration and Information Networks: Evidence from Nineteenth-Century Hesse-Cassel.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 58, no. 4, 1998, pp. 957–86. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2566846

Page, Thomas Walker. “The Causes of Earlier European Immigration to the United States.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 19, no. 8, 1911, pp. 676–93. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1819426

[26] Marianne S. Wokeck ,Trade in Strangers: The Beginnings of Mass Migration to North America, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999

[27] James D. Boyd, An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, Page 107 https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

[28] James D. Boyd, An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, Page 206 https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

[29] Trade in Strangers: The Beginnings of Mass Migration to North America by Marianne S. Wokeck, Page 28-29

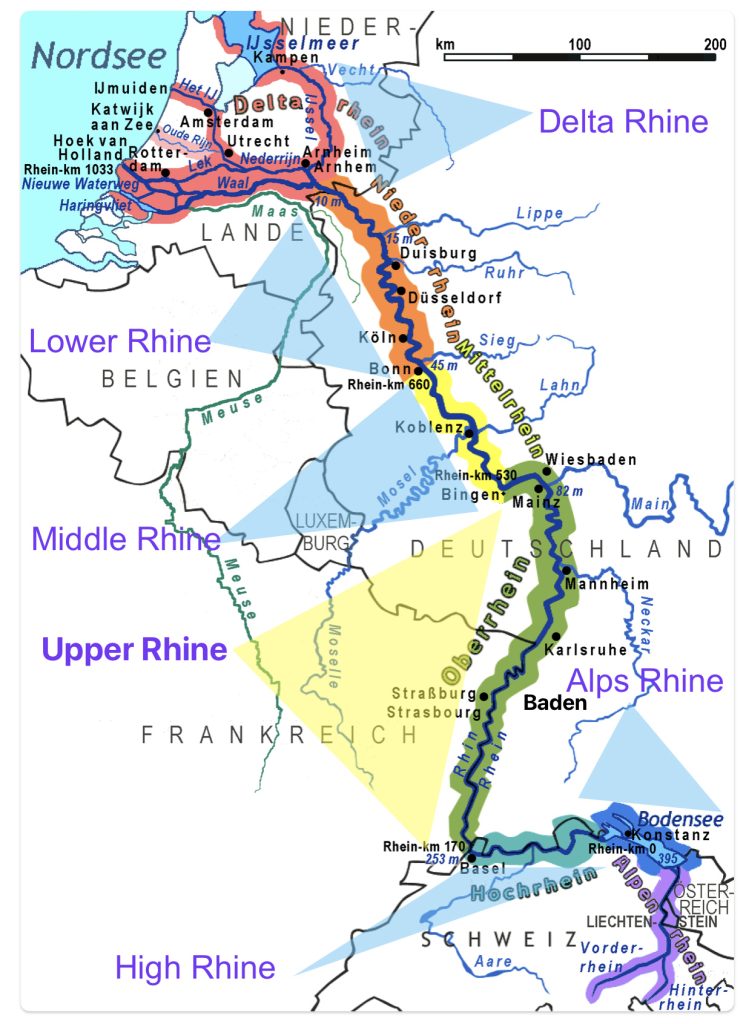

[30] The modern day countries and states along the “Upper Rhine” are Switzerland, France (Alsace) and the German states of Baden-Württemberg, Rhineland-Palatinate and Hesse.

Various Areas of the Rhine Valley

[31] Hochstadt, Steve. “Migration and Industrialization in Germany, 1815-1977.” Social Science History, vol. 5, no. 4, 1981, pp. 445–68. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/117082

Hochstadt, Steve. “Migration in Preindustrial Germany.” Central European History, vol. 16, no. 3, 1983, pp. 195–224. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4545987

[32] Bade, Klaus J. “From Emigration to Immigration: The German Experience in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.” Central European History, vol. 28, no. 4, 1995, page 510. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4546551 Page 510

Häberlein, Mark. “German Migrants in Colonial Pennsylvania: Resources, Opportunities, and Experience.” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 50, no. 3, 1993, pp. 555–74. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2947366

Marianne S. Wokeck, Trade in Strangers: The Beginnings of Mass Migration to North America, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999

[33] James Boyd, The Rhine Exodus of 1816/1817 within the Developing German Atlantic World, The Historical Journal, vol. 59, no. 1, 2016, page 102. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24809839

[34] The Kraichgau region is a hilly region in The Grand Dutchy of Baden, southwestern Germany. I indicated with a yellow dot in the map below, the Fliegel Family was from the Kraichgau area.Ittlingen is situated on the Elsenz River to the south of Sinsheim and to the north of Eppingen.

Physical map of Kraichgau (within brown line)

Map source: K. Jähne, Physische Karte des Kraichgaus, 19 June 2009, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Karte_Kraichgau_physisch.png

[35] German Palatine Emigration to America, FamilySearch Wiki, This page was last edited on 2 August 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Palatinate_%28Pfalz%29,_Rhineland,_Prussia,_Germany_Genealogy

Philip Otterness, Becoming German, The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York,Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004

[36] Source of Map One: Markgrafschaft Baden-Durlach, Wikimedia Commons, This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Markgrafschaft_Baden-Durlach.png

Source of Map Two:: The territorial gains of Baden between 1803 and 1819, Wikimedia Commons, This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baden-1803-1819.png

Margraviate of Baden-Durlach, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 1 November 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margraviate_of_Baden-Durlach

Margraviate of Baden, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 31 January 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margraviate_of_Baden

Margraviate of Baden-Baden, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 6 December 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margraviate_of_Baden-Baden

[37] The Palatine Germans, The National Park Service, Updated October 8, 2022 https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/the-palatine-germans.htm

Aaron Spencer Fogleman, Hopeful Journeys: German Immigration, Settlement and Political Culture in Colonial America, 1717-1775, Philadelphia: University of pennsylvania Press 1996

Philip Otterness, Becoming German, The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York,Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004

Cobb, Sanford Hoadley. The Story of the Palatines: An Episode in Colonial History. United Kingdom, G. P. Putnam’s sons, 1897. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Story_of_the_Palatines/eUgjAAAAMAAJ?hl=en

Brink, Benjamin Myer. “The Palatine Settlements” Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association, vol. 11, 1912, pp. 136–43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42889955. Accessed 27 May 2023.

Ellsworth, Wolcott Webster. “The Palatines in the Mohawk Valley.” Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association, vol. 14, 1915, pp. 295–311. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42890044. Accessed 27 May 2023.

Diefendorf, Mary Riggs. The Historic Mohawk. United Kingdom, Putnam, 1910. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Historic_Mohawk/ziIVAAAAYAAJ?hl=en

Benton, Nathaniel Soley. A History of Herkimer County: Including the Upper Mohawk Valley, from the Earliest Period to the Present Time ; with a Brief Notice of the Iroquois Indians, the Early German Tribes, the Palatine Immigrations Into the Colony of New York, and Biographical Sketches of the Palatine Families, the Patentees of Burnetsfield in the Year 1725 ; and Also Biographical Notices of the Most Prominent Public Men of the County ; with Important Statistical Information. United States, J. Munsell, 1856. https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_History_of_Herkimer_County/G1IOAAAAIAAJ?hl=en

Fogleman, Aaron. “Migrations to the Thirteen British North American Colonies, 1700-1775: New Estimates.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 22, no. 4, 1992, pp. 691–709. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/205241

Grabbe, Hans-Jürgen. “European Immigration to the United States in the Early National Period, 1783-1820.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 133, no. 2, 1989, pp. 190–214. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/987050

Otterness, Philip. “The 1709 Palatine Migration and the Formation of German Immigrant Identity in London and New York.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, vol. 66, 1999, pp. 8–23. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27774234

[38] German Palatine Emigration to America, FamilySearch Wiki, This page was last edited on 2 August 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Palatinate_%28Pfalz%29,_Rhineland,_Prussia,_Germany_Genealogy

Palatine migration to New York and Pennsylvania, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 6 March 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palatines

Cobb, Sanford Hoadley. The Story of the Palatines: An Episode in Colonial History. United Kingdom, G. P. Putnam’s sons, 1897. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Story_of_the_Palatines/eUgjAAAAMAAJ?hl=en

The Palatine Germans, The National Park Service, Updated October 8, 2022 https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/the-palatine-germans.htm

Philip Otterness, Becoming German, The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York,Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004

[39] James Boyd, The Rhine Exodus of 1816/1817 within the Developing German Atlantic World, The Historical Journal, vol. 59, no. 1, 2016, pp. 102-103. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24809839

[40] The map is an annotated version of a map that points out where Ittlingen and Baden are located in context of 18th century sources of German migration. The original version of the map is Map 1 Page 37 in James D. Boyd, An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

[41] James Boyd, The Rhine Exodus of 1816/1817 within the Developing German Atlantic World, The Historical Journal, vol. 59, no. 1, 2016, pp. 103. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24809839

Grubb, Farley. “The Auction of Redemptioner Servants, Philadelphia, 1771-1804: An Ecnomic Analysis.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 48, no. 3, 1988, pp. 583. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2121539

[42] The copy of the redemptioner contract is from Indentured servitude in British America, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 15 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indentured_servitude_in_British_America

[43] Grubb, Farley. “The Auction of Redemptioner Servants, Philadelphia, 1771-1804: An Ecnomic Analysis.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 48, no. 3, 1988, pp. 583–603. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2121539

Klepp, Farley Grubb, Anne Pfaelzer de Ortiz, Susan E (2006). Souls for Sale: Two German Redemptioners Come to Revolutionary America. Pennsylvania State University Press.

Herrick, Cheesman Abiah (2011). White Servitude in Pennsylvania: Indentured and Redemption Labor in Colony and Commonwealth. New York: Negro Universities Press 1969,

Galenson, David W. “The Rise and Fall of Indentured Servitude in the Americas: An Economic Analysis.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 44, no. 1, 1984, pp. 1–26. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2120553

[44] Klepp, Farley Grubb, Anne Pfaelzer de Ortiz, Susan E (2006). Souls for Sale: Two German Redemptioners Come to Revolutionary America. Pennsylvania State University Press.

Diffenderffer, Frank Ried (1977). The German immigration into Pennsylvania through the port of Philadelphia from 1700 to 1775 and The Redemptioners. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co.

Redemptioner, German Marylanders, https://www.germanmarylanders.org/miscellaneous-a-to-z/redemptioner

Matthew A. Mcintosh, Indentured Servitude in Colonial British America from the 17th to 18th Centuries, December 12, 2022, Bewminate, https://brewminate.com/indentured-servitude-in-colonial-british-america-from-the-17th-to-18th-centuries/

Indentured Servitude in British America, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 15 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indentured_servitude_in_British_America

Donoghue, John. “Indentured Servitude in the 17th Century English Atlantic: A Brief Survey of the Literature,” History Compass (October 6, 2013) 11#10 pp. 893–902,https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/hic3.12088

[45] Hans-Jürgen Grabbe, The Phasing-Out of 18th-Century Patterns of German Migration to the United States after 1817, American Studies Journal, No 62, 2013, DOI 10.18422/62-02, http://www.asjournal.org/62-2017/phasing-18th-century-patterns-german-migration-united-states-1817/#

See also: James D. Boyd, The Crisis of 1816/17: Replacing Redemption’s with Passengers on the Atlantic, YGAS Supplemental Issue 5 (2019), Pages 53 – 65, https://journals.ku.edu/ygas/article/view/18735/16756

[46] Boyd, James D., The Rhine Exodus of 1816/1817 within the Developing German Atlantic World, The Historical Journal. 2016; 59 (1): Pages 99-123. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X15000035

Hartmut Bickelmann, Günter Moltmann, and others “Germans to America: 300 Years of German Emigration to North America,” Stuttgart : Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations, 19821982, page 9

[47] Boyd, James D. “The Rhine Exodus of 1816/1817 within the Developing German Atlantic World, The Historical Journal 59, 2015, Page 118 http://www.jstor.org/stable/24809839

James Boyd, Merchants of Migration: Keeping the German Atlantic Connected in America’s Early National Period, Immigrant Entrepreneurship 1720 to the Present, German Historical Institute, February 6, 2015,, Undated August 22, 2018, http://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entries/merchants-of-migration-keeping-the-german-atlantic-connected-in-americas-early-national-period/

James D. Boyd, The Crisis of 1816/17: Replacing Redemptioners with Passengers on the Atlantic, YGAS Supplemental Issue 5 (2019) , 53- 65

Bade, Klaus J. “From Emigration to Immigration: The German Experience in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.” Central European History, vol. 28, no. 4, 1995, pp. 507–35. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4546551. Accessed 10 Mar. 2024.

Post, John D. “The Economic Crisis of 1816-1817 and Its Social and Political Consequences.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 30, no. 1, 1970, pp. 248–50. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2116738

Skeen, C. Edward. “‘The Year without a Summer’: A Historical View.” Journal of the Early Republic, vol. 1, no. 1, 1981, pp. 51–67. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3122774

Rothbard, Murray N. “The Panic of 1819: Contemporary Opinion and Policy.” The Journal of Finance, vol. 15, no. 3, 1960, pp. 420–21. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2326184

[48] James Boyd. “The Rhine Exodus of 1816/1817 within the Developing German Atlantic World, The Historical Journal, vol. 59, no. 1, 2016, pp. 55. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24809839

[49] James D. Boyd, The Crisis of 1816/17: Replacing Redemptioners with Passengers on the Atlantic, YGAS Supplemental Issue 5 (2019) , Page 55

[50] James D. Boyd, The Crisis of 1816/17: Replacing Redemptioners with Passengers on the Atlantic, YGAS Supplemental Issue 5 (2019) , Page 55

[51] Ibd , Page 54

[52] Ibid , Page 53

See also:

Moltmann, G. (1986). The migration of German redemptioners to North America, 1720–1820. In: Emmer, P.C. (eds) Colonialism and Migration; Indentured Labour Before and After Slavery. Comparative Studies in Overseas History, vol 7. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-4354-4_6

Grabbe, Hans-Jürgen. “The Phasing-Out of 18th-Century Patterns of German Migration to the United States after 1817.” American Studies Journal 62 (2017) http://www.asjournal.org/62-2017/phasing-18th-century-patterns-german-migration-united-states-1817/

Bade, Klaus J. “From Emigration to Immigration: The German Experience in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.” Central European History, vol. 28, no. 4, 1995, page. 510. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4546551 .

[53] James Boyd, The Rhine Exodus of 1816/1817 within the Developing German Atlantic World, The Historical Journal, vol. 59, no. 1, 2016, Page 118. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24809839

James D. Boyd, The Crisis of 1816/17: Replacing Redemption’s with Passengers on the Atlantic, YGAS Supplemental Issue 5 (2019), Pages 53 – 65 https://journals.ku.edu/ygas/article/view/18735/16756

[54] Boyd, James D. The Crisis of 1816/17: Replacing Redemptioners with Passengers on the Atlantic, YGAS Supplemental Issue 5 (2019) , Page 57

[55] Cohn, Raymond L., and Simone A. Wegge. “Overseas Passenger Fares and Emigration from Germany in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Social Science History, vol. 41, no. 3, 2017, Pages. 394, 402, 412. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/90017919

[56] Ibid, Page 404

[57] Ibid, Page 412

[58] Ibid, Page 405

[59] Page, Thomas W. “The Transportation of Immigrants and Reception Arrangements in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 19, no. 9, 1911, pp. 737. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1820349

[60] Cohn, Raymond L., and Simone A. Wegge. “Overseas Passenger Fares and Emigration from Germany in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Social Science History, vol. 41, no. 3, 2017, pp. 403. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/90017919

[61] Shannon Selin, Currency, Exchange Rates & Costs in the 19th Century , Imagining the Bounds of History, Page accessed Jan 23, 2024, https://shannonselin.com/2021/06/currency-exchange-rates-costs-19th-century/

Cohn, Raymond L., and Simone A. Wegge. “Overseas Passenger Fares and Emigration from Germany in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Social Science History, vol. 41, no. 3, 2017, pp. 399. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/90017919

[62] Cohn, Raymond L., and Simone A. Wegge. “Overseas Passenger Fares and Emigration from Germany in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Social Science History, vol. 41, no. 3, 2017, pp. 401-402. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/90017919

[63] Page, Thomas W. “The Transportation of Immigrants and Reception Arrangements in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 19, no. 9, 1911, pp. 738. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1820349

[64] Walter D. Kamphoefner, The Westfalians: From Germany to Missouri, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press 1987, Page 81 footnote 17.

[65] James D. Boyd, An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, Page 156 https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

[66] James D. Boyd, An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, Page 155 https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

See also Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration 1607-1860. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, Page 287 – 288

[67] James D. Boyd, An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, Page 158 https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf