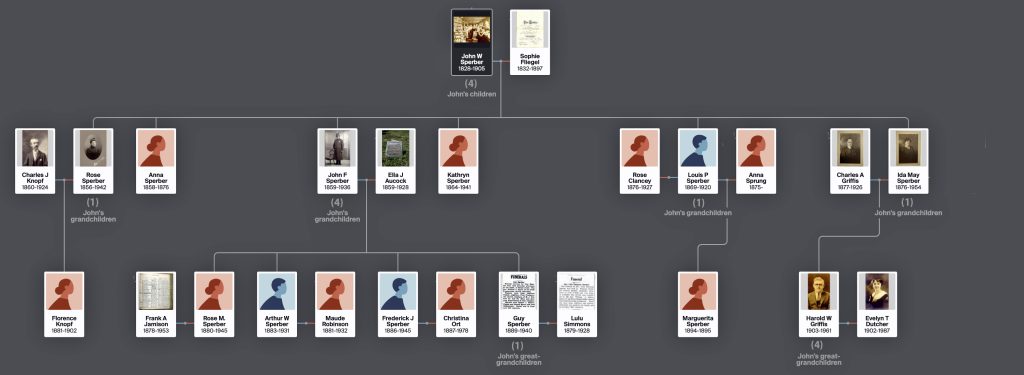

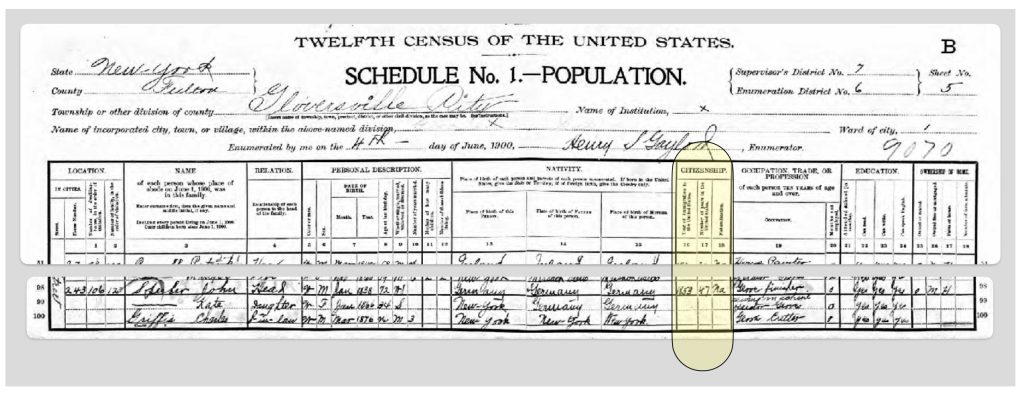

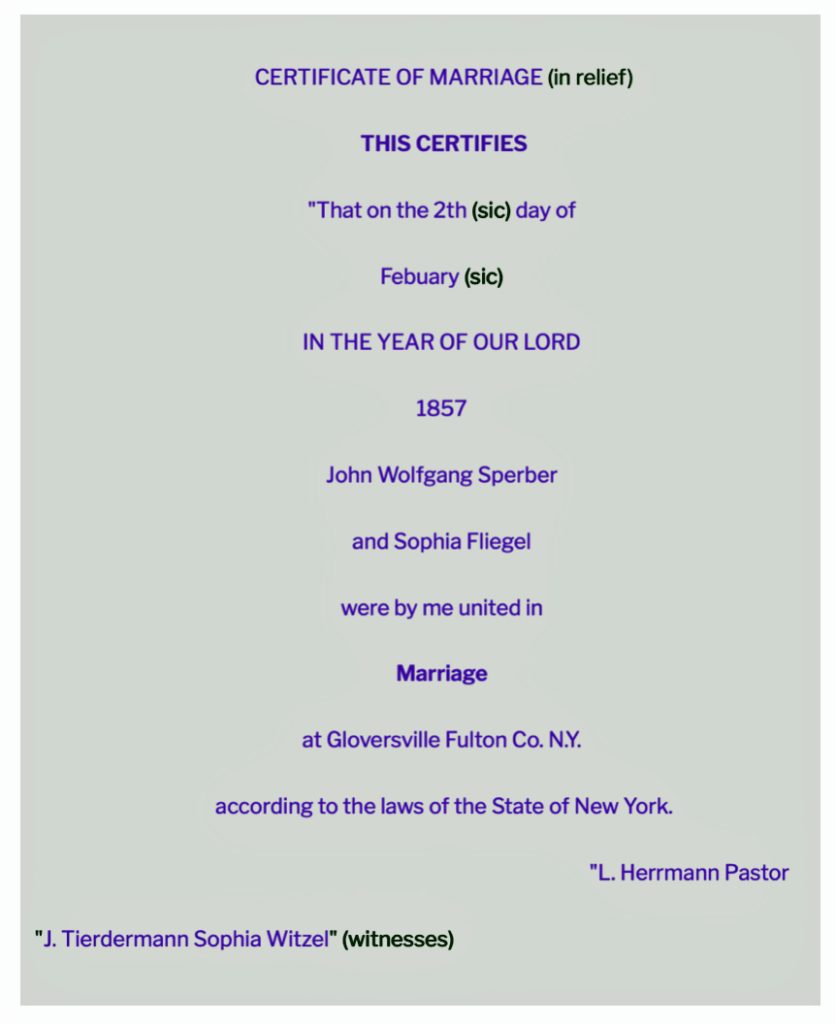

This is part four of a story about Johann Wolfgang Sperber immigrating to the United States. This part of the story discusses the possible influences that drew Johann Sperber to Fulton County, New York. We do not have direct evidence to explain why Johan Sperber ended up specifically in Gloversville, Fulton County, New York. However, we have indirect historical evidence that may offer clues as to why he ultimately chose Fulton county as his new home.

Six Part Story

The first of this story provides an overview of the family legacy John Sperber established in his new homeland, an historical background on where John was from in Baden, Germany, the influences on his migration to the United States, and the historical evidence of his departure and arrival to America.

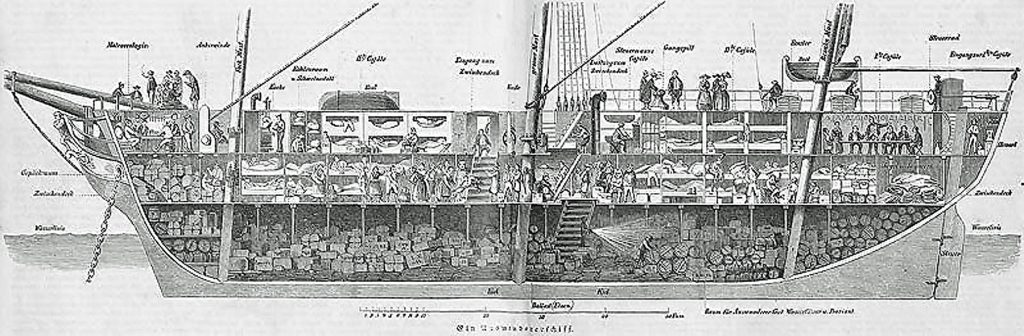

The second part of John Sperber’s story describes his journey from Baden-Baden to Le Havre based on historical evidence and historical accounts.

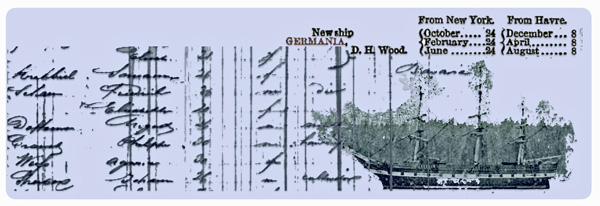

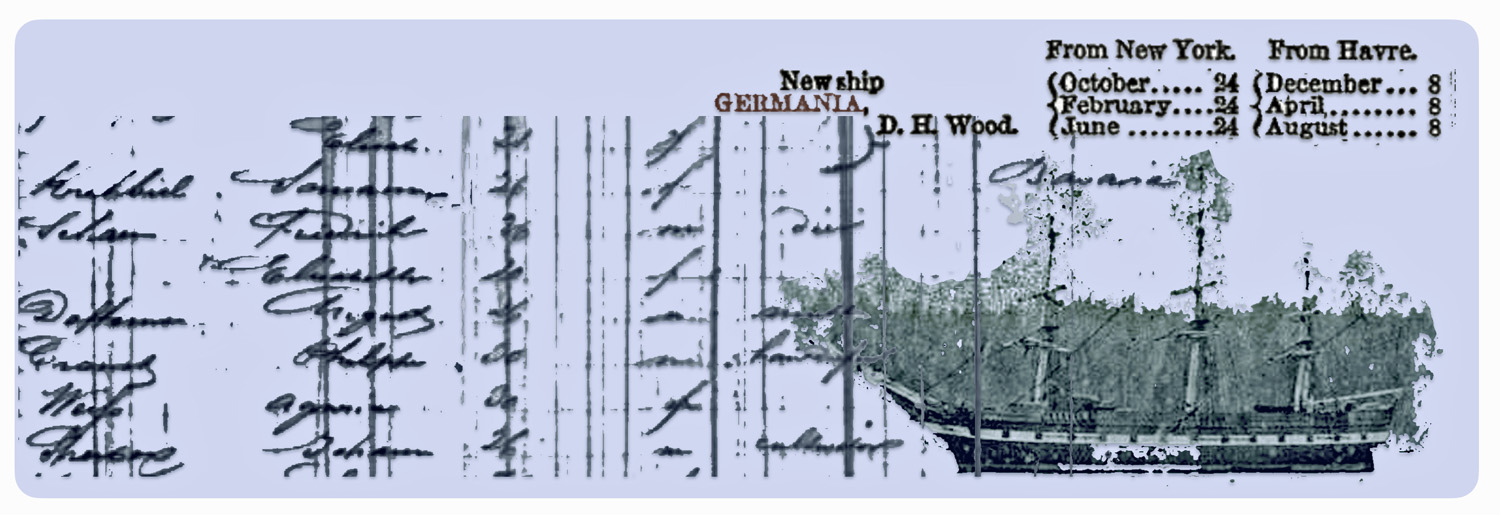

The third part of the story assesses the three major inland pathways to European ports that John had options to consider. Since it is not absolutely certain the ship manifest list for the Germania reflect our John Sperber, I have provided historical background on the relative accessibility of the three major routes John may have taken to make his voyage to the United States.

The fifth part of the story covers his travel to New York City and his options to travel to Gloversville, Fulton County, New York.

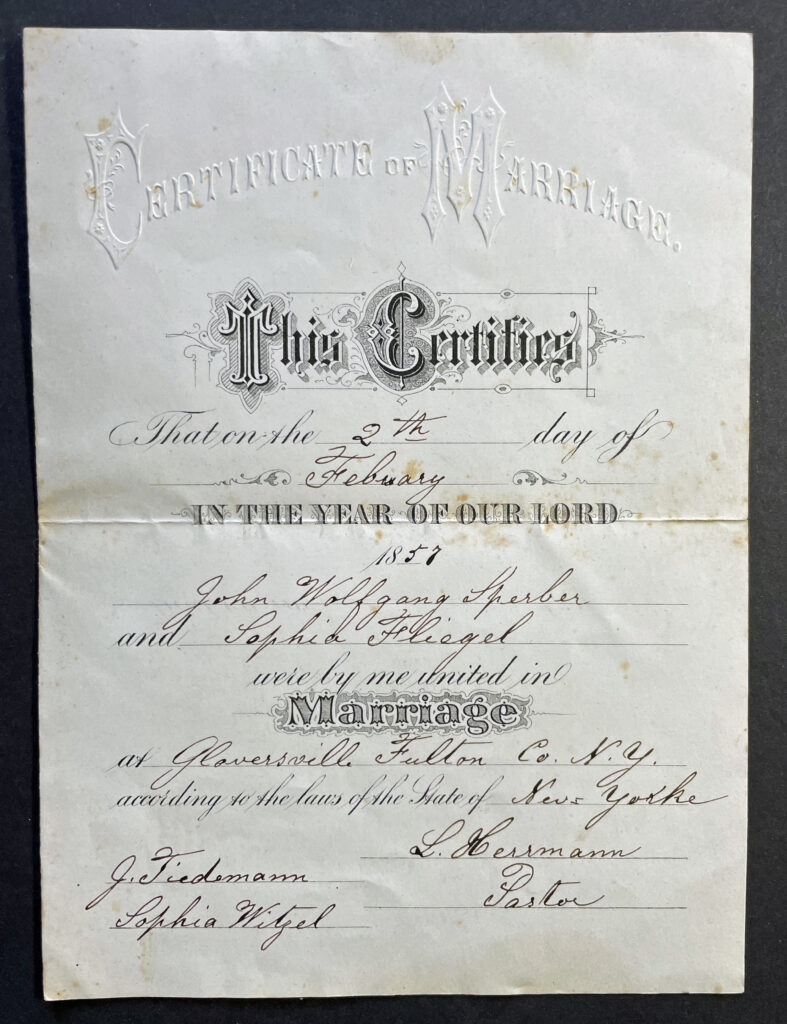

The sixth part of the story covers his establishing a new life and family in the Johnstown and Gloversville, New York area. This is the end of a rather long story that attempts to provide not only a discussion of the available ‘facts’ we have of Johann and his family but also provide a broader social and historical context in which he made this journey from Baden to New York state. Like a song, some of the ‘facts’ are a refrain from prior parts of the story.

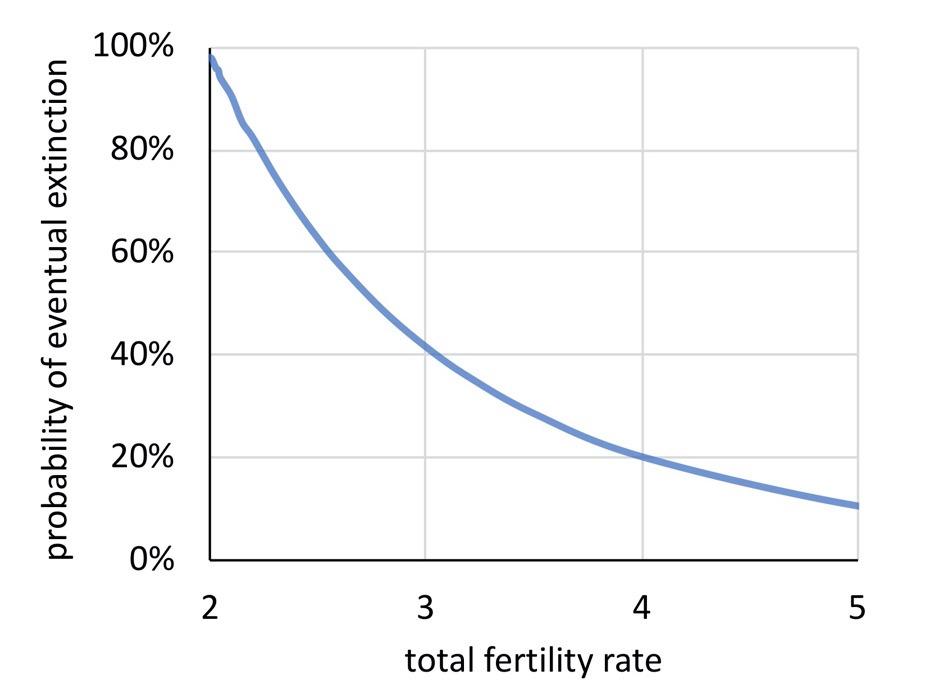

Why did Johann Sperber end up in Fulton County, in New York state? I have addressed general aspects of this question in prior parts of this story. We can specifically look at this question in terms of three nested questions that start from a general question to a regional question and then to a specific geographical question.

The first question is why Johann landed in New York City. The second question is why did he head to the Mohawk valley. The third question is why did he specifically end up in the Gloversville – Johnstown area in Fulton County

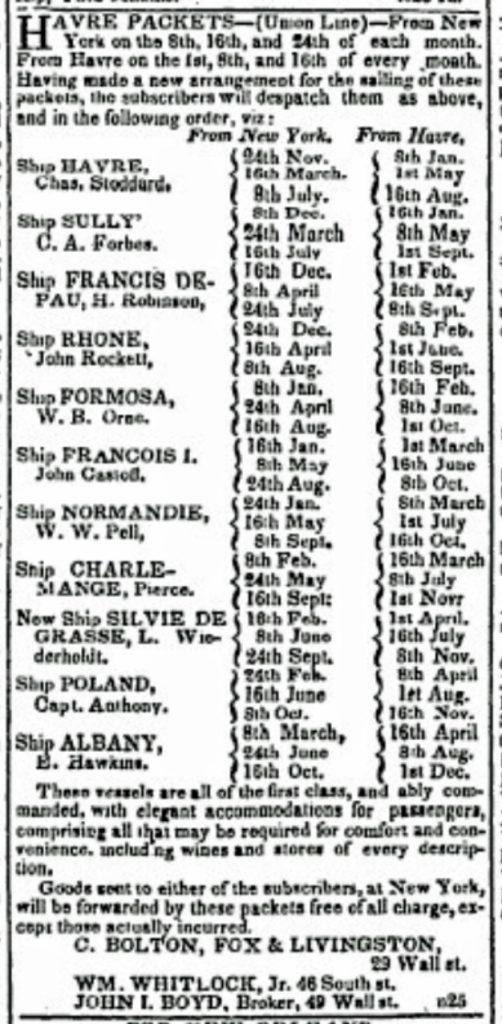

Le Havre to New York City

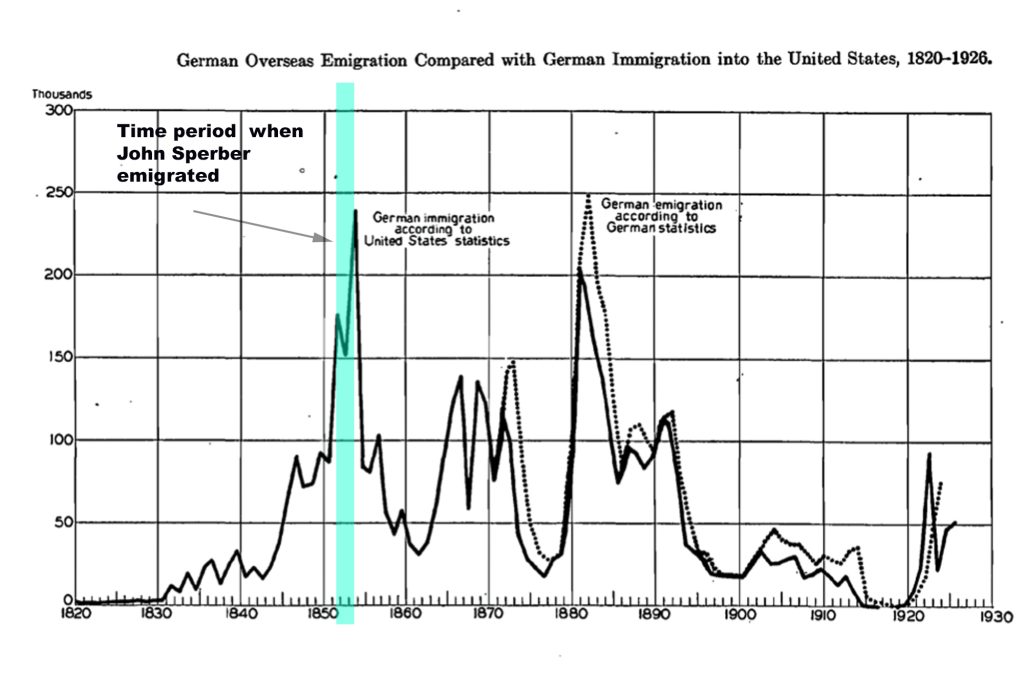

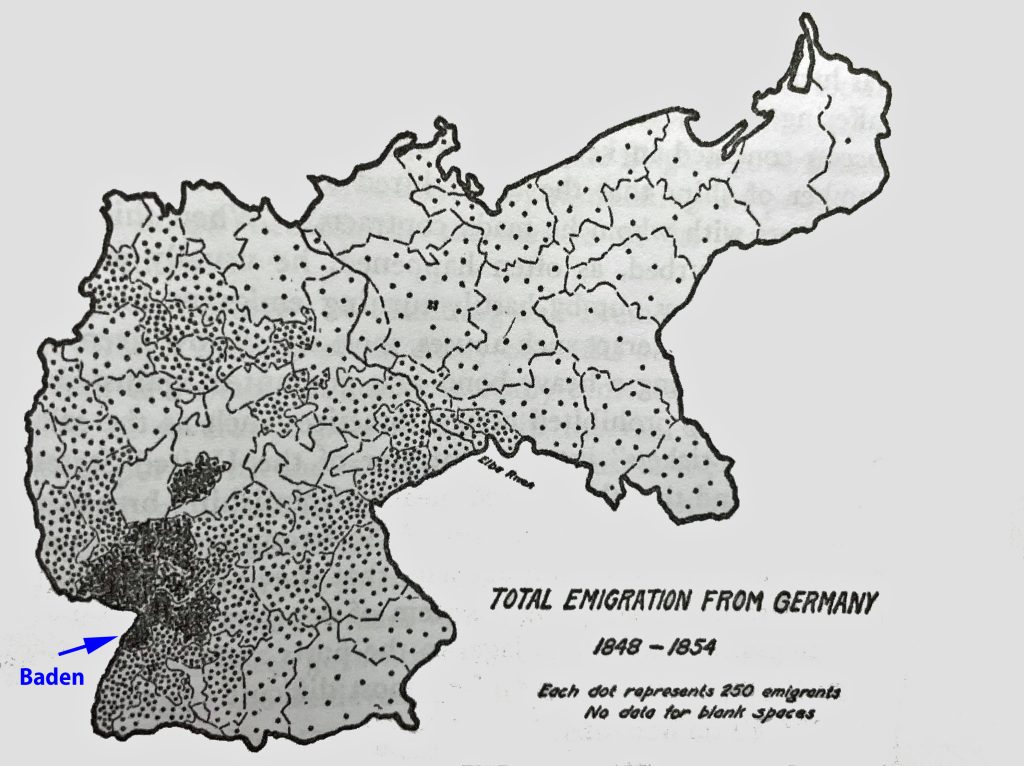

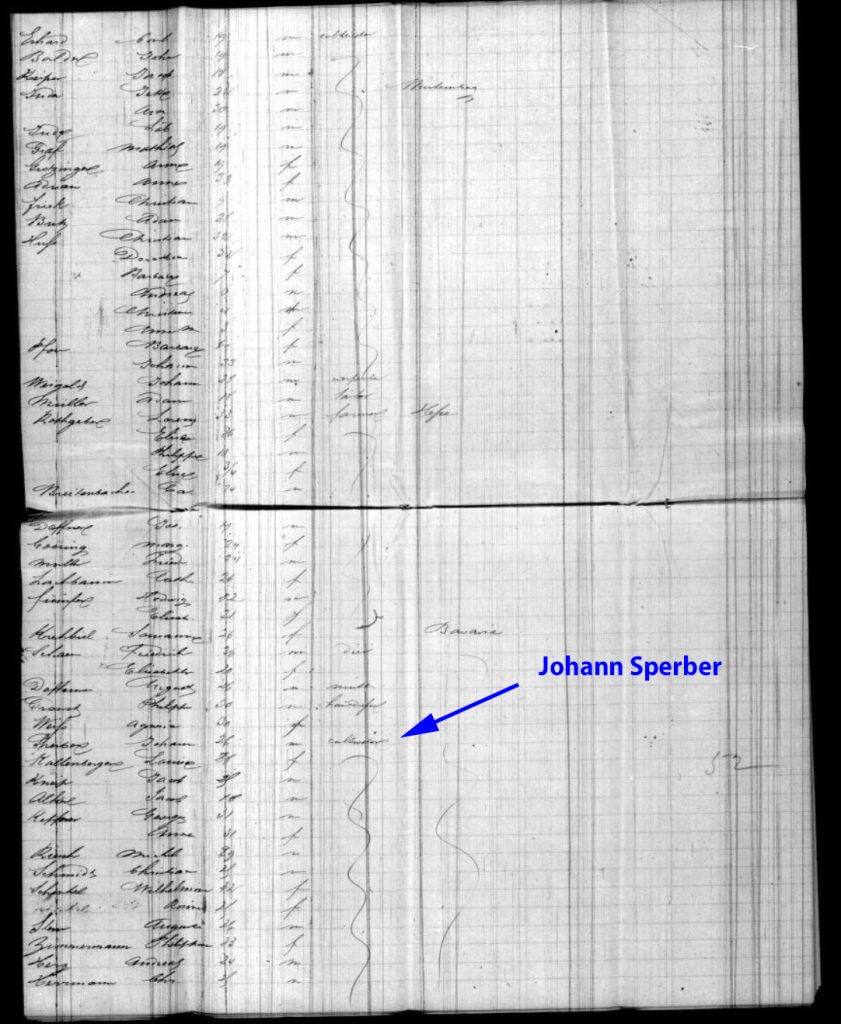

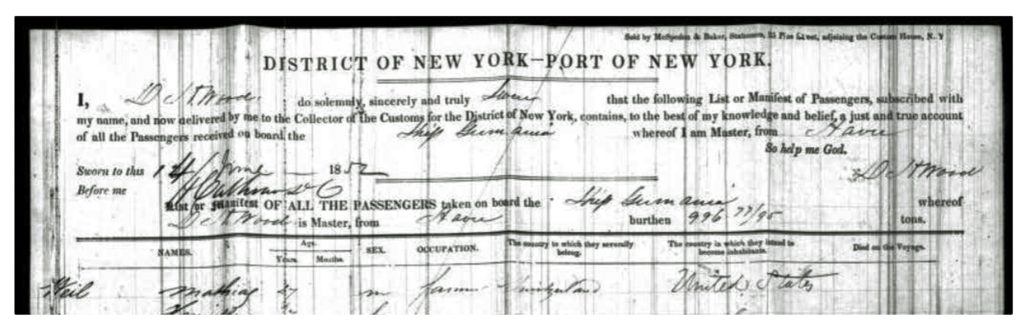

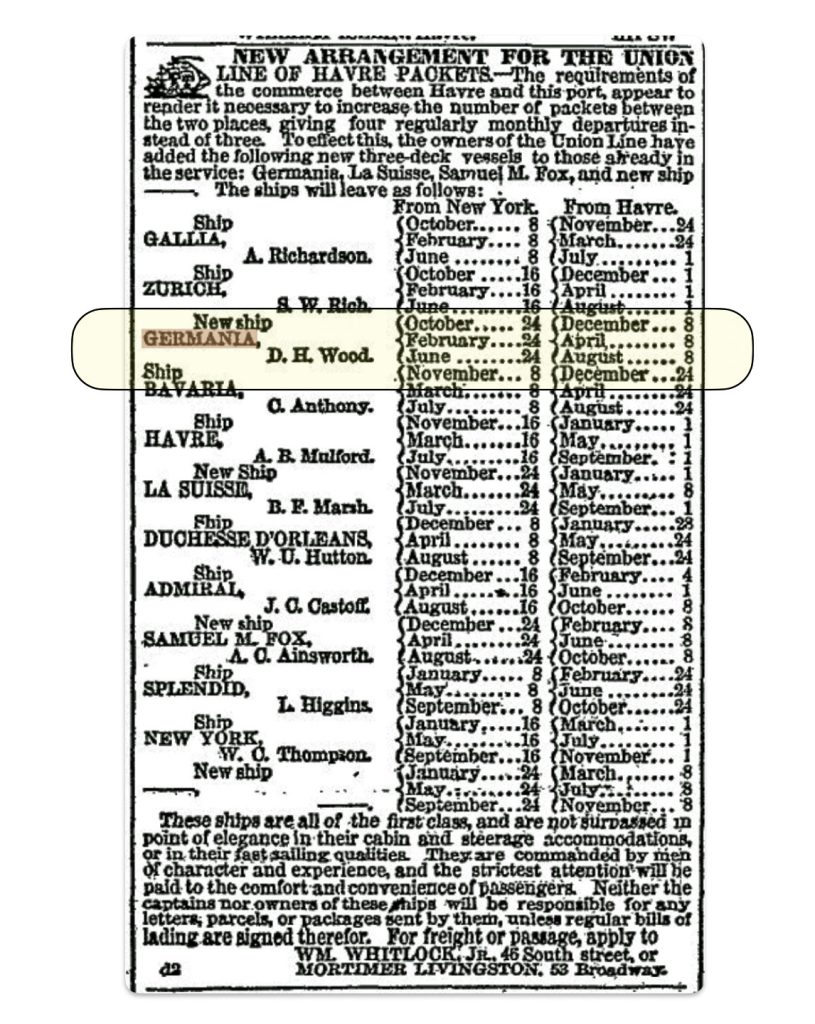

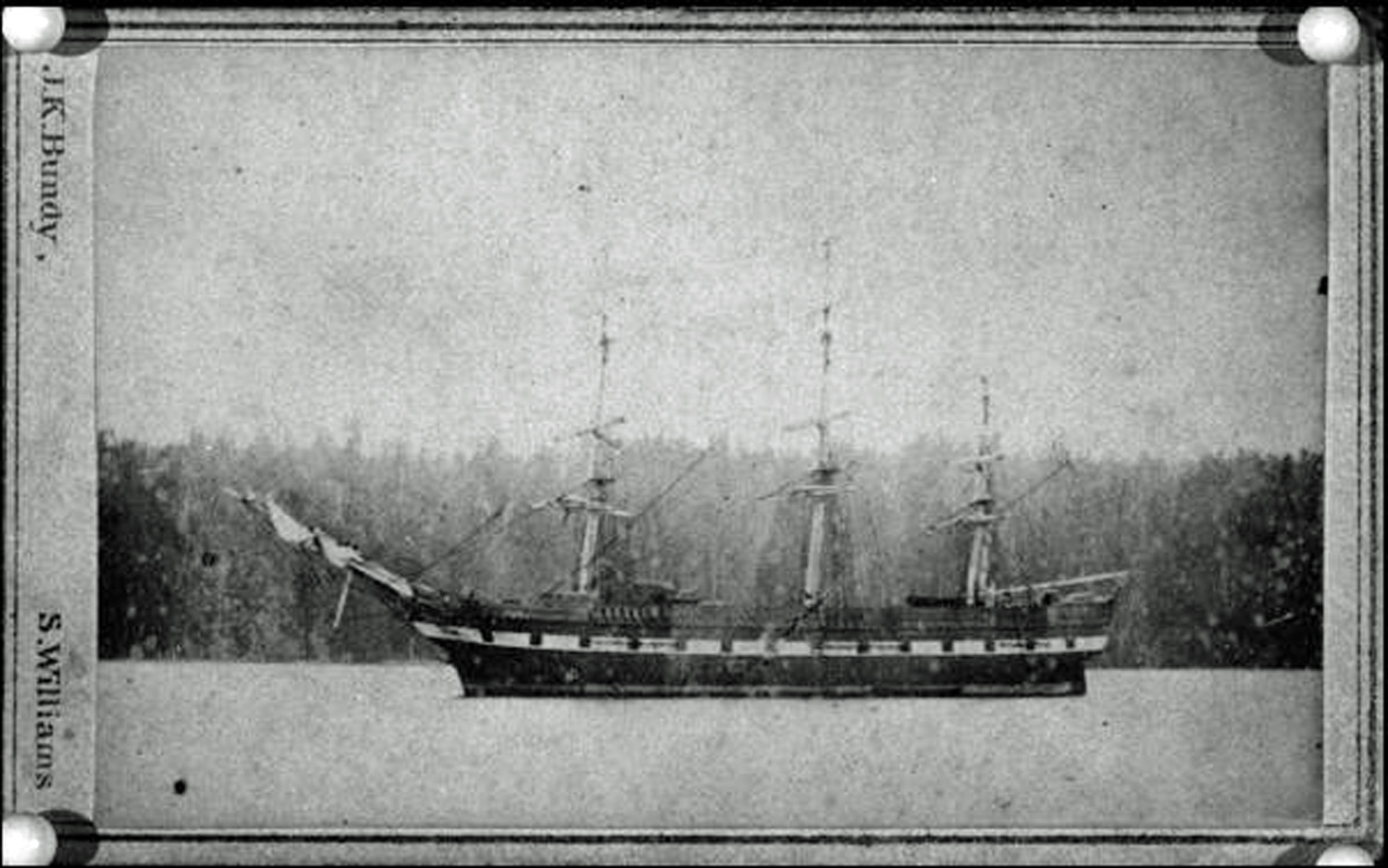

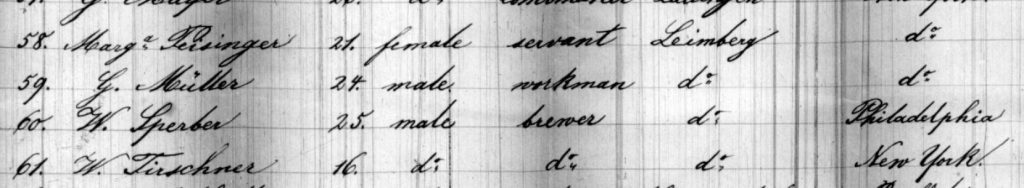

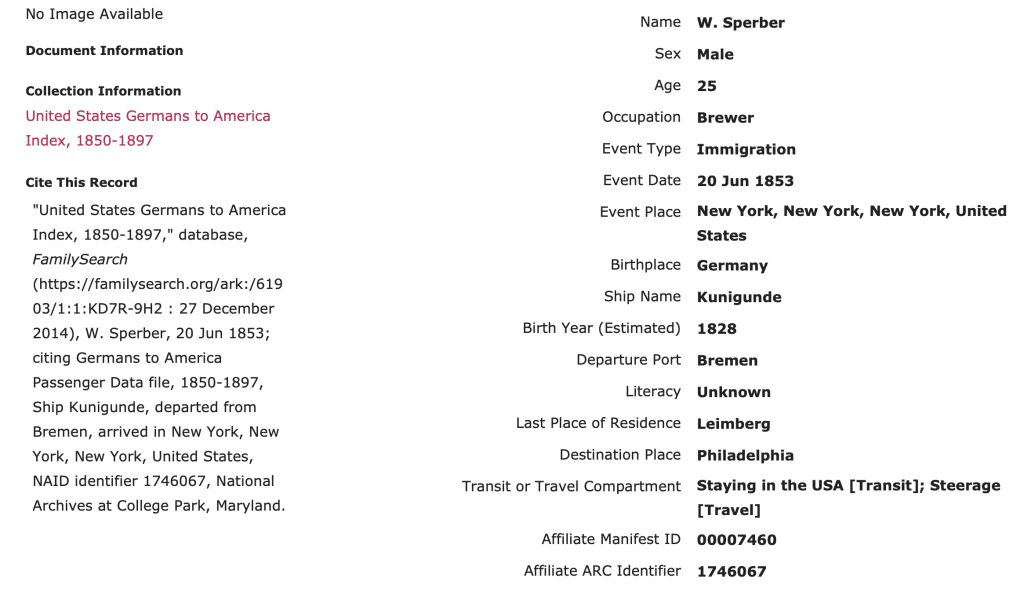

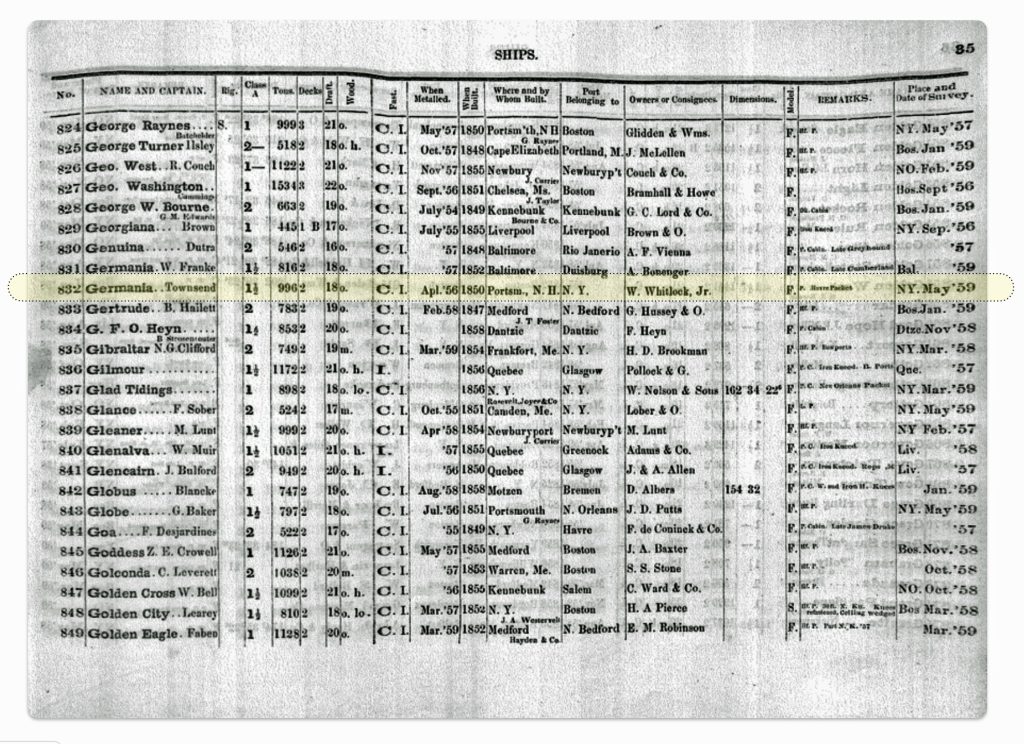

Johann’s arrival in New York city is substantiated by information found on the Germania ship manifest . In previous parts to this story, it was also substantiated with historical facts that Germans from the Grand Duchy of Baden had a long history of migrating to the Mohawk valley in New York state. In addition, since 1830 New York city was “the gateway of the nation” for the vast majority of Germans immigrating to America.

“New York City served as the gateway not only to the Empire State but to an entire region. Included in its hinterland was northern Ohio, which was mainly settled by the Erie canal and Great Lakes route… .” [1]

“The most important ports of arrival in the United States were New York, from which the immigrants dispersed via Albany and Troy throughout the western part of the country, and Baltimore and New Orleans, from which they reached the Mississippi.” (emphasis added) [2]

“(New York city’s) connection with the interior was a prime cause of New York’s commercial supremacy,. … In the middle of the century Buffalo, Cleveland, and Milwaukee were the distributing points for those bound to the Northwest, and to reach these cities the Erie Canal and, after 1846, the railroad from New York to Buffalo were by far the quickest and the cheapest routes.” [3]

Johann was one of many Germans who sailed to New York city in 1852. If we were to look at the place of origin of male individuals arriving in the United States the year Johann arrived (see table one), German males from the various German states represented one of the two largest groups to migrated to American in 1852. Men from Ireland and Germany represented almost three quarters of all males entering the United States in 1852.

Table One: Place of Birth of Males Arriving in the United States 1852

| Place of Birth | Number | Percentage | Cumulative Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ireland | 85715 | 36.6 | 36.6 |

| German States | 84,205 | 35.9 | 72.5 |

| England | 17,311 | 7.4 | 79.9 |

| Scotland | 4,733 | 2.0 | 81.9 |

| France | 2,571 | 1.1 | 83.0 |

| Returning Americans | 23,053 | 9.8 | 92.8 |

| Other Countries | 16,847 | 7.2 | |

| Total | 234,435 | 100.0 |

New York City to the Mohawk Valley

Why did Johann gravitate to the Mohawk valley rather than simply stay in New York city or migrate to Ohio or other locations in America? Johann’s journey to the Mohawk valley is perhaps due to the influences of the migration decisions of past generations and his contemporaries in Baden, the contours of transportation networks in New York state and the economic prospects of the time.

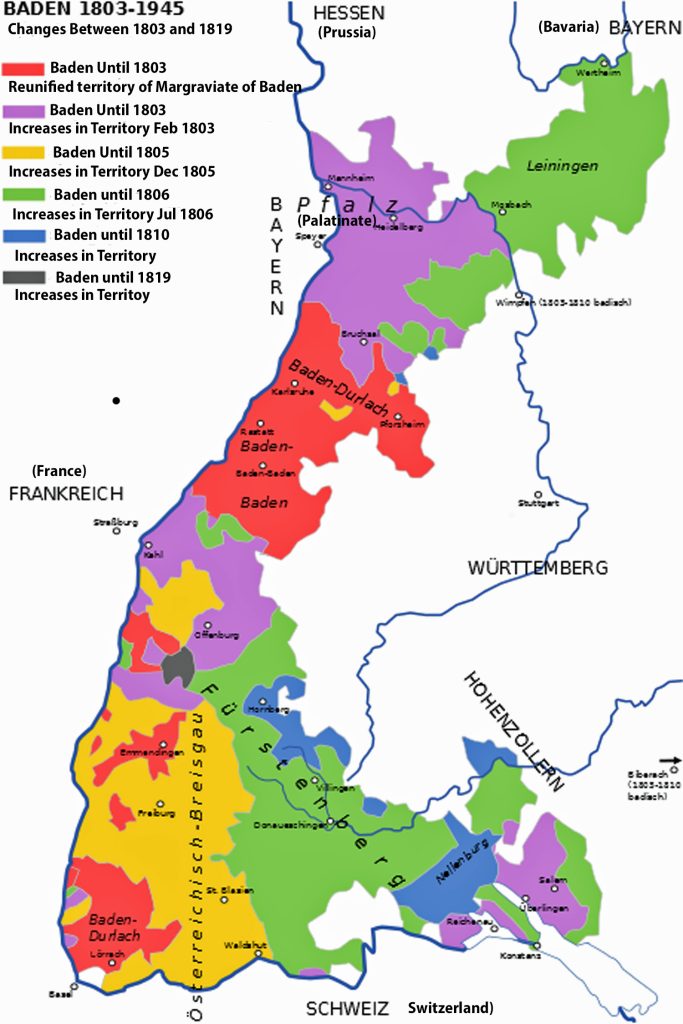

The Baden area, from where Johann lived, had a rich and long history of migration to the Mohawk valley in New York state. This intergenerational tradition reaches back into the late 1600s and 1700s.

“In the eighteenth century, more than 100,000 migrants left the south-west German regions of the Electoral Palatinate, Kraichgau, Baden-Durlach, and Duchy of Württemberg, as well as neighbouring Alsace and the Swiss cantons, in order to cross the Atlantic.” (emphasis is mine) [4]

The Kraichgau region and Baden Durlach were areas in the eighteenth century where generations of the Fliegel and Sperber families possibly resided. Individuals from these areas along the Rhine River, migrated to the Mohawk valley in the 1700s. While the route getting to America may have been different, there may have been a strong likelihood to follow the ‘guiding star’ of tradition (oral or written) that lead him to the ‘Palatine’ area along the Mohawk River in New York state.

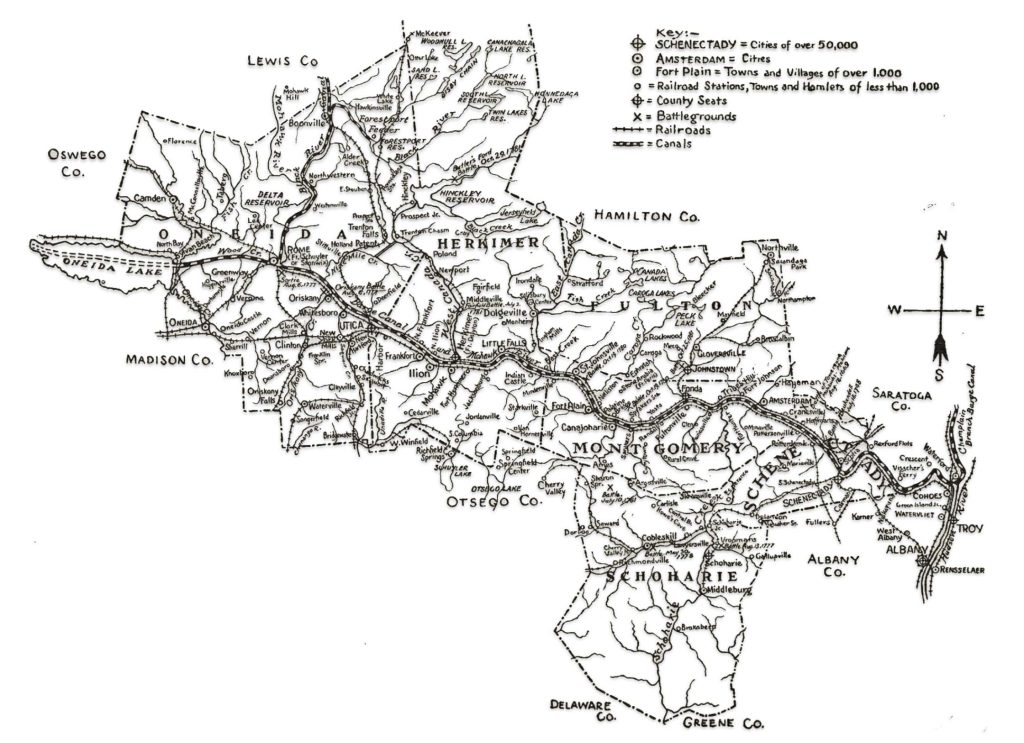

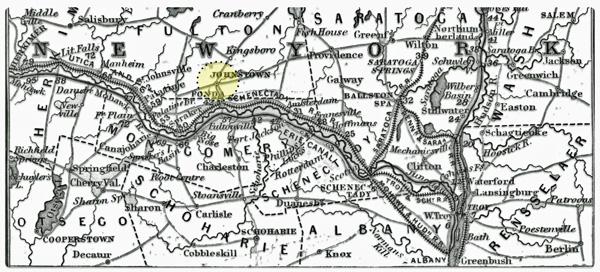

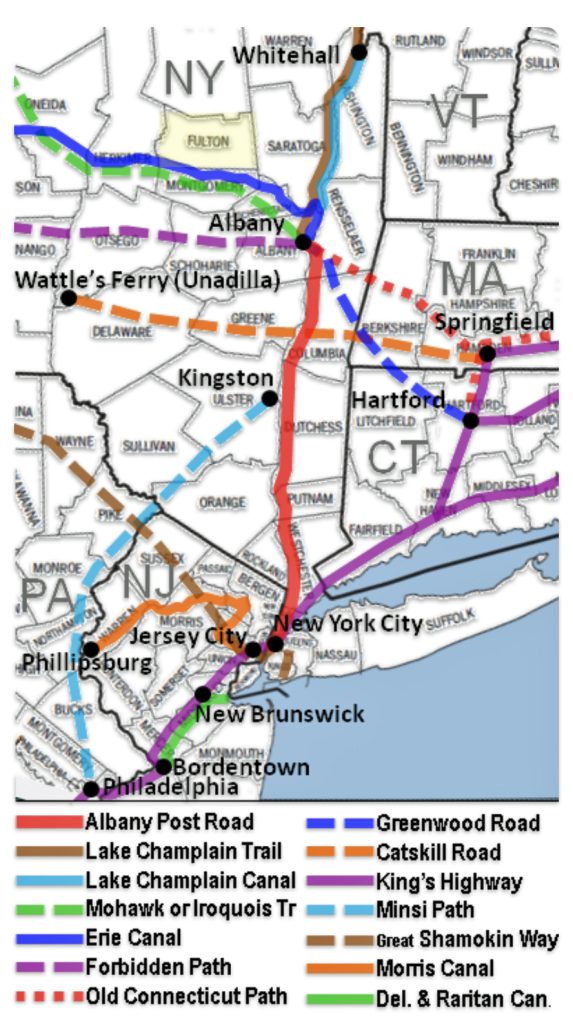

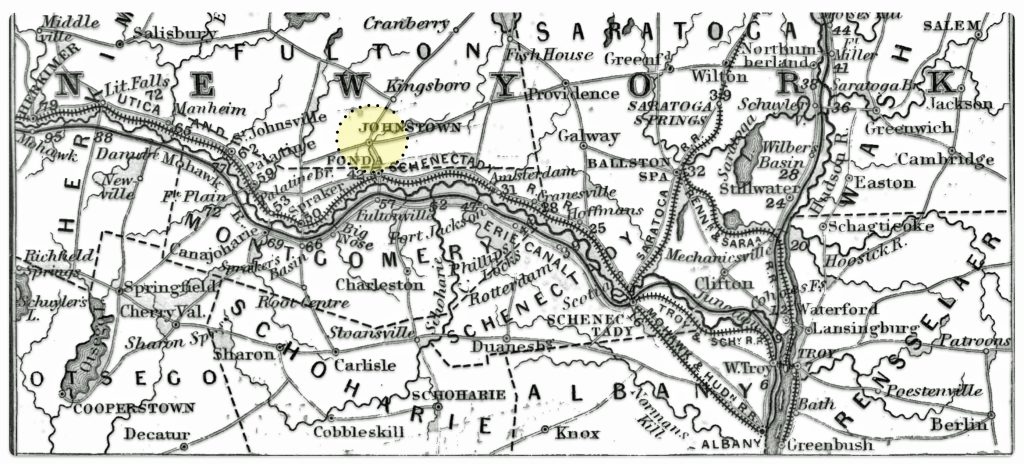

The inland flow and direction of migration patterns of German migration in New York state were largely determined by the natural topological contours of the state. The natural path between New York city and Albany and westward from Albany had been firmly established since the early 1700s, (see map one). The Hudson river valley provided a natural topographical pathway between New York city and the Albany – Schenectady area. The Mohawk River Valley, running east and west, cuts a natural path between the Catskill Mountains to the south and the Adirondack Mountains to the north.

Map One: Topological Map of New York State

While a few rough roads existed, the Hudson and Mohawk Rivers were the primary transportation arteries in the 1700s. Along with the two waterways, major roads following the two rivers were established in the 1600s based on Indian pathways. They continued to be used and upgraded through the time that Johann arrived: the Albany Post Road and the Mohawk Turnpike. Another road that paralleled the Mohawk Turnpike was on the southern side of the Mohawk river. There was also the was the Great Western Turnpike. [5]

Map Two: Travel By Road: Albany Post Road & Mohawk Trail (Fulton County Highlighted)

The Albany Post Road, also known as the “Queen’s Road,” and later the “King’s Road” existed since 1669. The road connected the colonial seaport of New York City (then called New Amsterdam) with the fur trading outpost, and, at that time, the second-largest city of Albany (Beverwijck). Each end of the road at New York City and Albany was a nexus of other significant migration routes. (see map two). The Albany Post Road followed along the east side of the Hudson River and was about 150 miles (241 km) long. However, in 1806 competing turnpike routes lessened the traffic on the old route. By 1850 railroads had made the Albany Post Road obsolete and stagecoach service stopped. [6]

“A private company built the Highlands Turnpike to the west, in more level country, and opened it in 1806. This diverted traffic away from the section north of Peekskill through Continental Village and past the lakes. Iron mining at Hopper Lake in the 1820s partially replaced it, and the stage route was not changed. The old road fell into further disuse when the turnpike became a public highway in 1833 and it was no longer needed as a shunpike. The completion of the Hudson River Railroad to Albany in 1850 made the road obsolete as a commercial and postal artery, and stage service ended.” [7]

As a main artery through the Mohawk Valley, the Mohawk Turnpike was critical in facilitating the massive westward migration of settlers in the early nineteenth century before canals and railroads took over the bulk of long-distance transportation. The turnpike ran about 95 miles from Schenectady to Rome, NY, paralleling the Mohawk River and providing an overland route through the Mohawk Valley. [8]

The turnpike developed from old Mohawk Indian trails and was also known as part of the Iroquois Trail that ran from Albany to Buffalo. Its improvement in the early 1800s made it the favored route for westward travel. In 1811, stagecoach lines ran day and night over the turnpike from Albany to Buffalo, completing the trip in just 3 days with frequent horse changes. This enabled more rapid migration. Traffic on the turnpike began to diminish after the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, but it continued to be used heavily in the winter months when the canal was closed. [9]

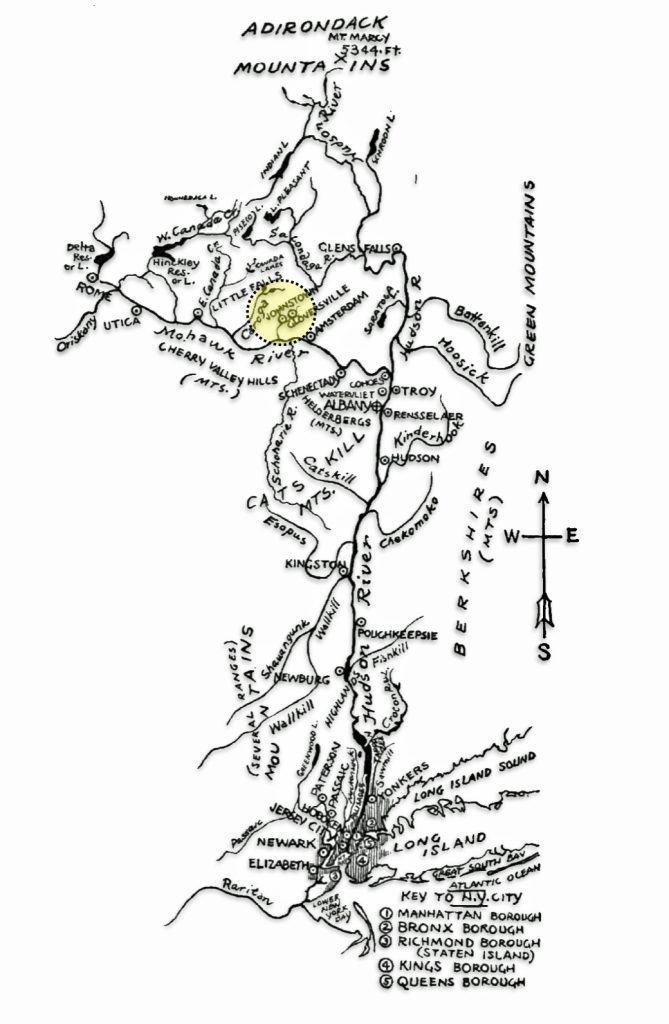

Map three illustrates the network of waterways from New York city to the Johnstown-Gloversville area (highlighted in yellow). From a transportation infrastructure perspective, Johann took the same route as did those from Baden before him. Except he had three avenues of travel: road, water and rail. Immigrants in the early 1800s would have traveled by steamboat up the Hudson River or traveled on roads along the river from New York City to Albany. By the 1830s-1850s, railroads and turnpikes became the preferred modes of travel as transportation infrastructure rapidly improved during the transportation revolution of the nineteenth century.

Once in the ‘capital city area’ of Albany, Schenectady, and Troy, the confluence of roadways heading north and south and west were critical in facilitating the massive westward migration of settlers in the early nineteenth century before canals and railroads took over the bulk of long-distance transportation. The improvements of the roadways enabled hundreds of thousands to more easily make the journey from the eastern seaboard into the Great Lakes region and beyond.

Map Three: The Hudson and Mohawk River Valleys – Johnstown-Gloversville Area

The map: “Showing also the rivers of northeast New Jersey, which empty into the mouth of the Hudson, and towns over 50,000 on these streams. The mountains bordering the Hudson valley are also indicated. Only New York state towns having city charters, lying in the Hudson valley, the Mohawk being the chief tributary of the Hudson.” [10]

The Origins of Fulton County

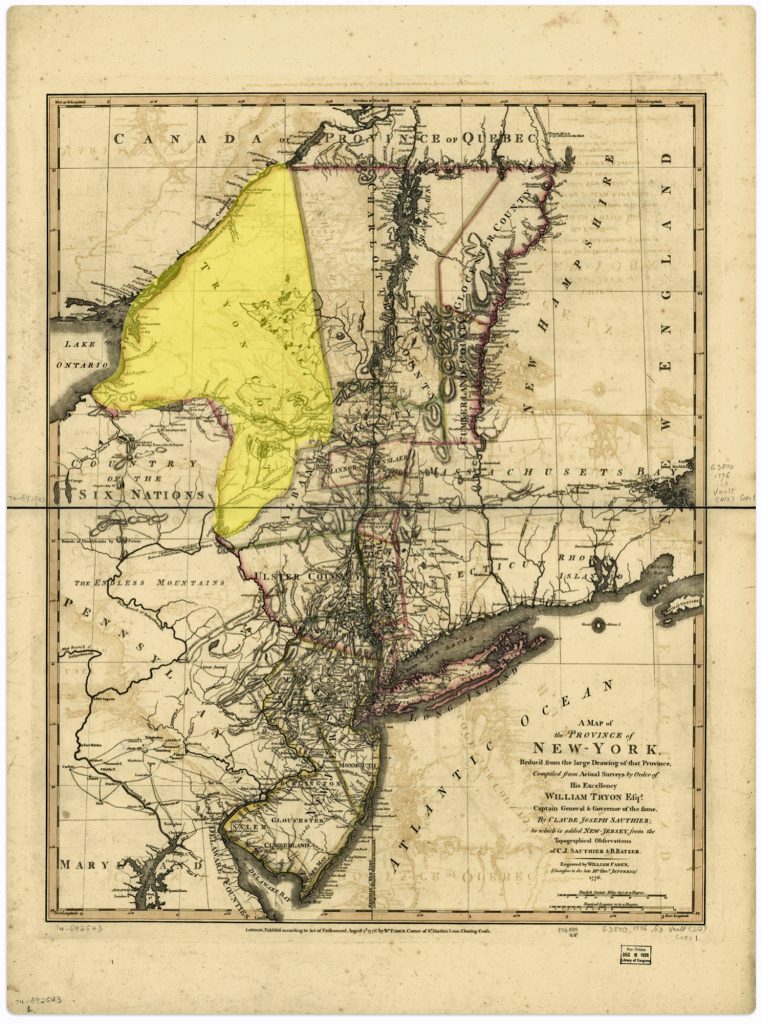

Map Four: Mohawk River and Settlements in 1777 – Tryon County, Province of New York

Source: Blown up section of Sauthier, Claude Joseph, Bernard Ratzer, and William Faden. A map of the Province of New-York, reduc’d from the large drawing of that Province, compiled from actual surveys by order of His Excellency William Tryon, Esqr., Captain General & Governor of the same, by Claude Joseph Sauthier; to which is added New-Jersey London, Wm. Faden, 1776. Map.

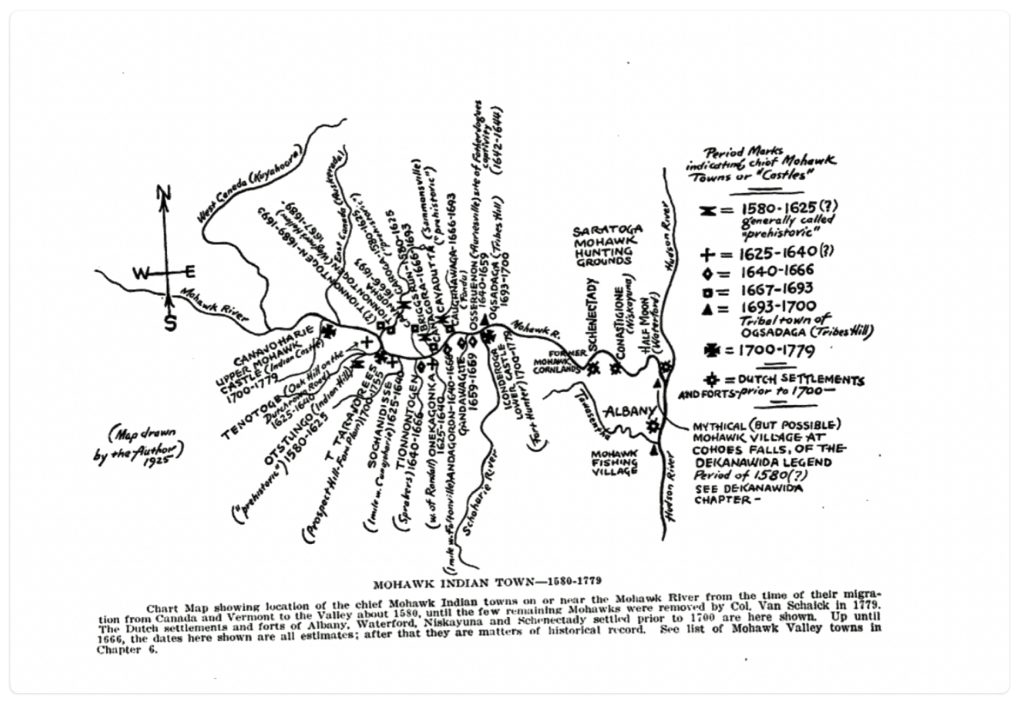

Prior to the eighteenth century, the lands that would become Fulton County were used by the Mohawk Indians as hunting and fishing grounds. In the early 1700s, the first European settlers, mostly German Palatines, started arriving and tilling the rich soil in the western regions. [11]

Map Five: Mohawk Indian Towns 1580 – 1779

Map Six: Tryon County (Highlighted) 1777

. London, Wm. Faden, 1776. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/74692643/

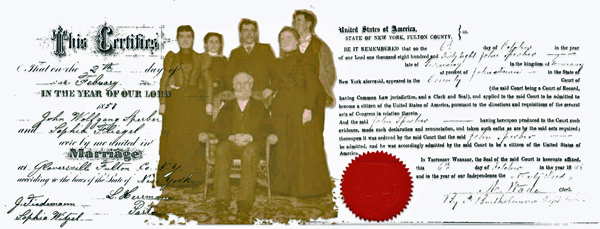

In 1753, the Kingsborough Patent [12] , containing parts of present-day Johnstown, Mayfield and Ephratah, was purchased by Sir William Johnson, a prominent British colonial official. It was originally part of Albany County, a county in the colonial province of New York in the British American colonies. In 1772, at Johnson’s urging, this area became part of the newly formed Tryon County, with Johnstown as the county seat. After the American Revolution, Tryon County was renamed Montgomery County in 1784. (See maps five and six). [13]

As western migration took place, this large Montgomery County soon became sub divided into new counties with their own county seats. In 1789, Ontario County was split off from Montgomery. The area of the new county was much larger than the present Ontario County, as it included the present Allegany, Cattaraugus, Chautauqua, Erie, Genesee, Livingston, Monroe, Niagara, Orleans, Steuben, Wyoming, Yates, and part of Schuyler and Wayne counties. In 1791, Herkimer, Otsego, and Tioga counties were split off from Montgomery. In 1802, portions of Clinton, Herkimer, and Montgomery counties were combined to form St. Lawrence County. In 1816, Hamilton County was split off from Montgomery county.

The operation of the new Erie Canal and the building of new roads along the river attracted new settlements to the Mohawk Valley and population growth soared in that area of the county south and southwest of Johnstown.

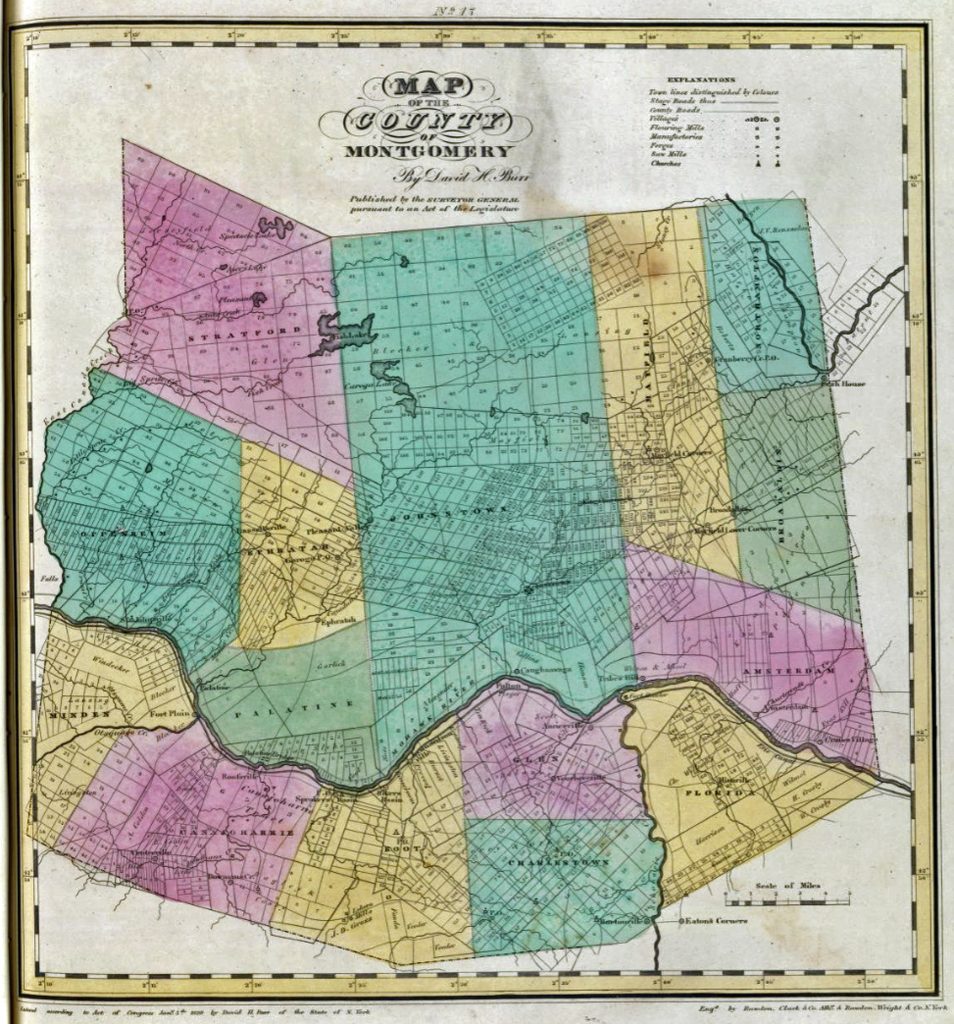

Map Seven: Montgomery County 1829

Because of this shift in the population center, the people in the Mohawk Valley area petitioned the New York State Legislature to have the county seat of Montgomery County transferred to Fonda, New York This was approved in 1836.

The relocation of the county seat from Johnstown to Fonda created a groundswell of resentment from citizens living in Johnstown area and on the north side of the Mohawk river. A petition was made to the New York Legislature to have the county divided into two counties. On April 18, 1838, this request was approved and the northern half of the divided county was named Fulton County after Robert Fulton of steamship and Erie Canal fame and Johnstown once again became a county seat. [14]

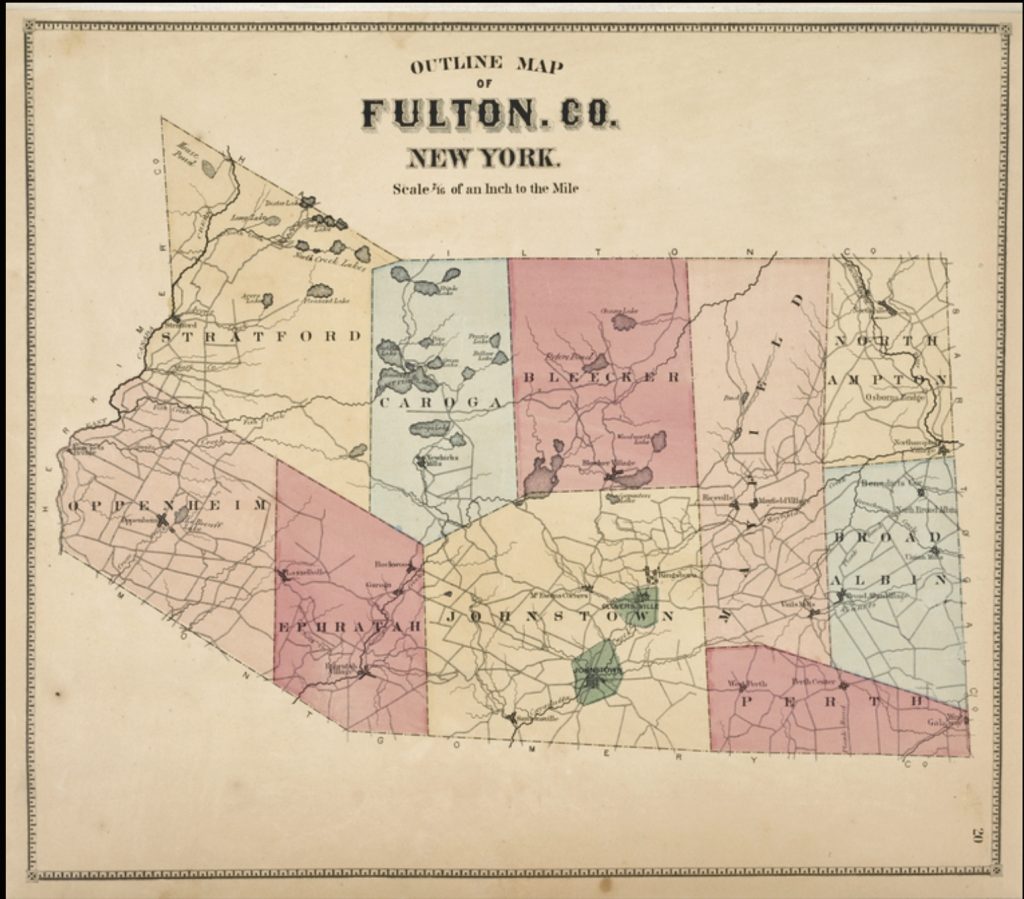

Map seven depicts the town boundaries within Fulton county after the split. The county was composed of nine towns: Stratford, Oppenheim, Carugao, Ephrayah, Blecker, Johnstown, Mayfield, North Ampton, Broadalbin and Perth.

Map Seven: Fulton County New York

Heading to the Gloversville – Johnstown Area

The third leg of the journey, Johann Sperber’s decision to migrate specifically to Fulton County, is an open research question. It is a question that may never have a definitive answer.

One general observation is that Johann’s intended destination may have been one of the major settlement areas of the Palatine area and not necessarily Fulton county. As indicated above, the historical subdivisions of Montgomery county resulted in a number of different counties. Johann may have been focused on getting to a particular town or general area rather than a particular county.

There are plausible explanations of why he settled in the Gloversville-Johnstown area. Johann may have had contacts that settled in what was now called Fulton county. The Fulton County area may have offered economic opportunities among the towns and cities within the old ‘Palatine” area along the Mohawk River. The lingering question is what did this particular area have that was different from other towns along the river that also experienced growth and opportunity.

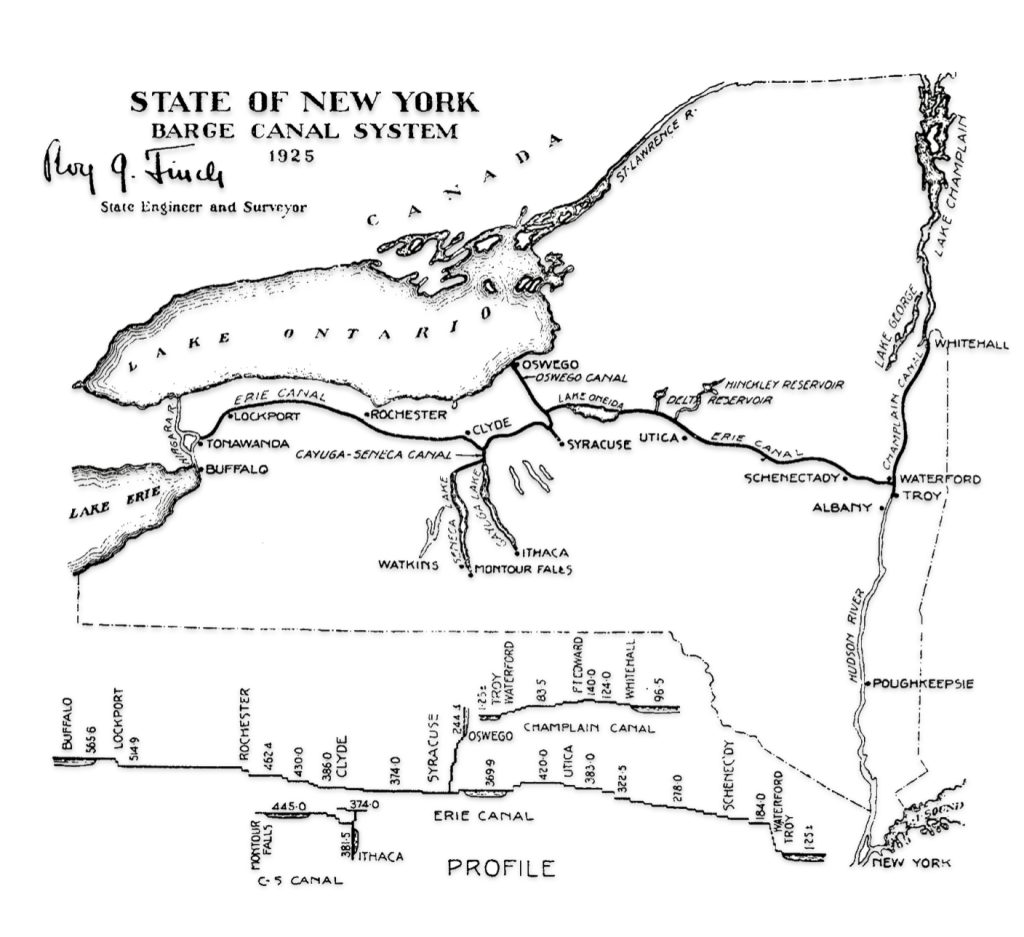

The 1850s saw the Mohawk Valley transitioning to a manufacturing based economy enabled by transportation developments, while still maintaining agricultural roots especially in the dairy industry. The Erie Canal, completed in 1825, facilitated the development of large villages in the Mohawk Valley and provided a means to transport goods east and west. (see map eight) [15]

Map Eight: The Erie Canal and the New York Barge Canal System

“The Erie Canal had a tremendous impact on the economic growth of the Albany area and points further west. The first railroad in the ‘Capital Region’ ironically was built as a way to circumvent the slow down of barge traffic at Cohoes Falls. It was among the first railroads in the country and helped herald in a new age of transportation. Soon after the success of this early pioneer line, other railroads soon followed and the Capital District became a hotbed of economic growth and a leader in railroad transportation.” [16]

There were 29 railroads in New York already built or under construction by 1850. Troy and Schenectady became a hub for the emerging railway system in New York state. Within the ‘Capital region’ railroads such as the Mohawk & Hudson Railroad (1831), Troy and Greenbush Railroad (1845), Utica and Schenectady Railroad (1833), Syracuse and Utica Railroad (1839) ,the Rensselaer and Saratoga Railroad (1836), and Saratoga and Schenectady Railroad (1832) enabled further industrial growth and movement of people. [17]

The Hudson River Railroad connected New York city to the ‘Capital Region’ (New York to Greenbush, now renamed Rensselaer, opposite Albany). It was opened a year prior to Johann’s arrival in 1851. The Troy and Greenbush Railroad became part of this greater Hudson River Railroad in 1851.

As reflected in map nine, Johann had many options to travel up to the Capital area and through the Mohawk valley area. One observation to note is the absence of a connected rail line to Johnstown from the Utica and Schenectady Rail Line that followed the contour of the Mohawk River in the 1850s. Compared to the other towns and cities in the Mohawk Valley, Johnstown was not directly on the bank of the Mohawk River. Depending on what side of the Mohawk River one traveled on, traveling to Johnstown could be accomplished by taking the road north from Fultonville to Johnstown (if you were on the south side of the river). If you were traveling west from the Capital area on the north side of the river, you could take the road or train to Fonda and then the road north from Fonda to Johnstown, which is only abut five miles.

Map Nine: Water, Road and Rail Connections in the Capital Area and Mohawk Valley 1850

By the 1850s, the Mohawk valley had a significant manufacturing presence, with industries such as textiles, furniture, heavy machinery, and lumber. Specific examples include the the emerging Remington Arms company in Herkimer County which was a major employer, and textile mills in Utica. Specific industries emerged in certain areas, such as glove and leather manufacturing starting in Fulton County. Smaller towns specialized in certain products, such as food packing in Canajoharie, knit goods in Fort Plain and St. Johnsville, and felt shoes in Dolgeville. Overall, the period saw a diversification of manufacturing, the rise and fall of certain industries like dairy and textiles, the emergence of new industries enabled by technological developments, and the growth of factories as major employers. [18]

Map Ten – The Mohawk Valley [19]

Map ten depicts the Mohawk valley and the six New York state counties that are part of ‘the valley’. The map shows all places that had over 200 in population in 1920 as well as smaller places that had historic significance. It should be noted the map shows a rail connection between Fonda and Johnstown that did not exist when Johann Sperber was migrating to Johnstown.

Two years prior to Johann’s arrival in the United States, of the six counties in the Mohawk valley, Fulton county was second smallest county based on population size in 1850. (see table two). Oneida county was the largest of the Mohawk valley counties, constituting 41 percent of the total Mohawk valley population. Oneida’s size was attributable to the presence of two towns: Utica and Rome.

Both cities were located along major transportation routes. Utica was situated on a shallow spot of the Mohawk River, while Rome was positioned at an important early land bridge between main waterways. Both cities flourished as canal towns, with the flow of raw materials, finished goods and settlers. [20]

This made them key points for the movement of people and goods. Utica underwent significant industrial growth in the mid-1800s, becoming a major center for manufacturing, especially in the textile industry. It was known as the “Manchester of America” for its booming textile mills. [21]

Table Two: Population of the Six Counties of the Mohawk Valley 1850

| County | Population | Percentage of Mohawk Valley |

|---|---|---|

| Oneida | 99,566 | 40.9 % |

| Herkimer | 38,244 | 15.7 % |

| Schoharie | 33,584 | 13.8 % |

| Montgomery | 31,992 | 13.1 % |

| Fulton | 20,171 | 8.3 % |

| Schenectady | 20,054 | 8.2 % |

| Total | 243,611 | 100.0 % |

https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1850/1850a/1850a-22.pdf

Table three provides examples of principal industries in which the majority of the wage earners of the valley were engaged prior to and up to when Johann Sperber migrated to the area. Grist mills, saw mills, tanneries, blacksmith shops, fulling and carding mills, and asheries were built at nearly all Mohawk valley centers in the settlement period, from 1813 to 1852, the year Johann arrived.

Table Three: Principal Industries in Mohawk Valley Counties 1813-1852

| Date | Description of Manufacturing Development | County |

|---|---|---|

| 1813 | Pottery Works started in Rome | Oneida |

| 1820 | Manufacture of plows began in Utica. | Oneida |

| 1822 | Ephraim Hart foundry started in Utica. | Oneida |

| 1823 | Grist mill and an iron foundry opened in Utica. | Oeida |

| 1823 | Worthington hat factory opened in Rome. | Oneida |

| 1826 | Pottery works opened in Utica. | Oneida |

| 1839 | Harry Burrell of Salisbury makes first shipment of cheese to England. | Herkimer |

| 1831 | Remington opens forge for manufacture of gun barrels and firearms in Ilion. | Herkimer |

| 1832 | Manufacture of knit goods began in Cohoes. | Schenectady |

| 1836 | Manufacture of axes and other edge tools began in Cohoes. | Schenectady |

| 1836 | Manufacture of ready-made clothing began in Utica. | Oneida |

| 1836 | Manufacture of cotton cloth (white goods) introduced in Cohoes, Harmony Mills Company. | Schenectady |

| 1840 | Threshing machine invented by George Westinghouse, ,Central Bridge. | Schoharie |

| 1840 | Manufacture of ingrain carpets began in Amsterdam. | Montgomery |

| 1842 | Manufacture of woolen goods began in Little Falls. | Herkimer |

| 1842 | Stove and furnace manufacture began in Utica. | Oneida |

| 1842 | Carpet mill at Hagamans rmoved to Amsterdam. | Montgomery |

| 1844 | Manufacture of matches started in Frankfort. | Herkimer |

| 1845 | Manufacture of yarn begun in Little Falls. | Herkimer |

| 1845 | Manufacture of railroad steam locomotives began in Schenectady. | Schenectady |

| 1846 | First kid glove factory of Johnstown established. Gloves continued to be made in the homes of Johnstown and Gloversville. | Fulton |

| 1847 | Manufacture of woolens began in Utica. | Oneida |

| 1848 | Manufacture of linseed oil began in Amsterdam. | Montgomery |

| 1848 | Manufacture of linseed oil begun at Amsterdam. | Montgomery |

| 1848 | Manufacture of cotton cloth (white goods) began in Utica. | Oneida |

| 1850 | First solid steel gun barrel made in the Remington works at Ilion. | Herkimer |

| 1851 | Manufacture of locomotive headlights started int Utica. | Oneida |

| 1852 | Iron works started at Utica. | Oneida |

“(E)ven in cities with large numbers of unskilled German workers, substantial numbers of skilled Germans tended to dominate the same trades (especially clothing, shoe, and furniture making). … (S)killed German-American artisans and workers either migrated to and stayed in the major manufacturing centers where there was employment for their skills or they settled in smaller centers to the extent that there was employment available in their trades.” [22]

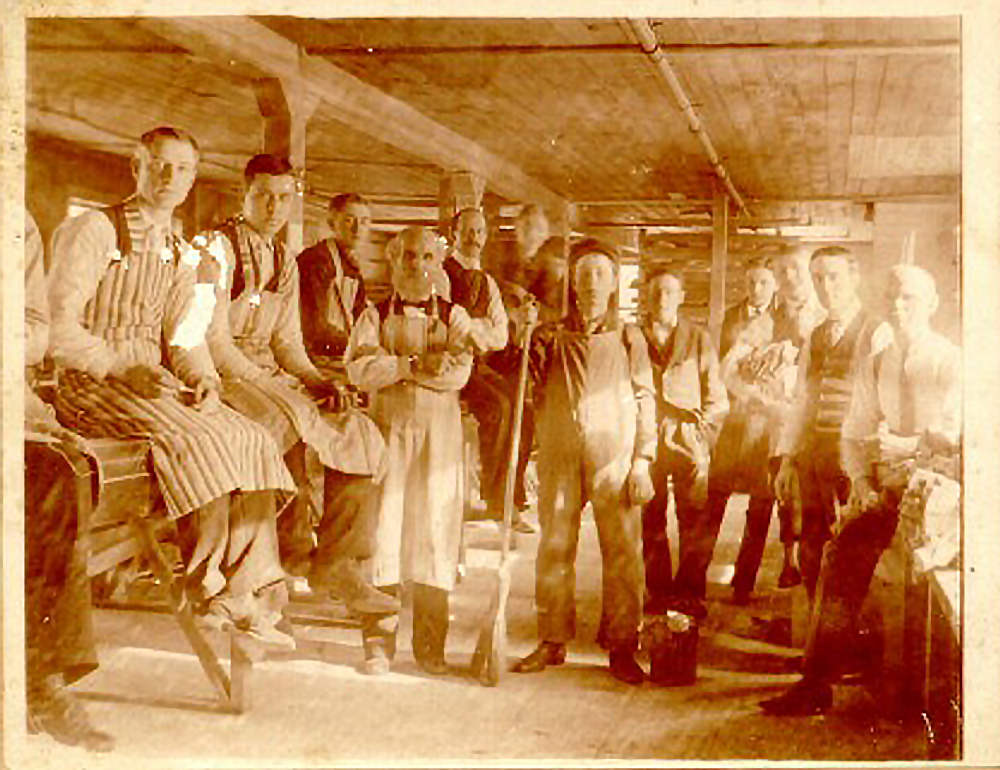

Despite other Mohawk valley counties that were larger and perhaps had larger sized employers in various manufacturing industries, Johann ended up in Gloversville, Fulton county. The key question is what drew Johann to the Johnstown – Gloversville area. Did he have contacts in the area? Did he have experience with glove making? Why did he end up working in the glove making business?

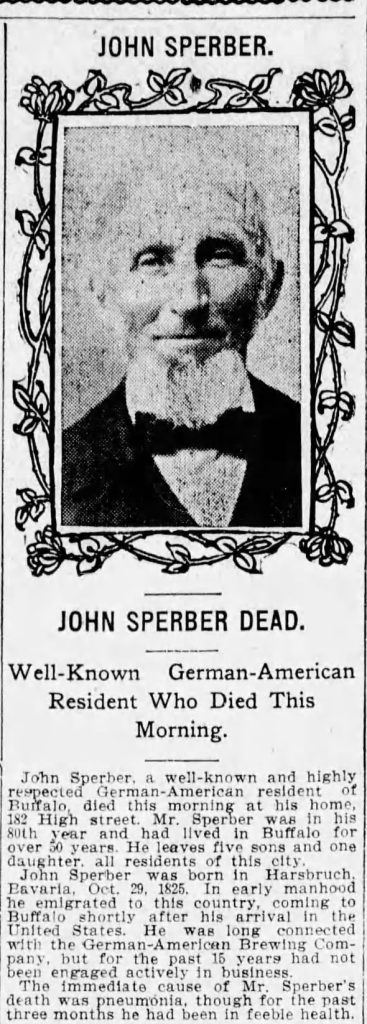

“The Littauer Laying Off Room” – An older John Sperber in the Middle Foreground with Arms Folded circa 1890s

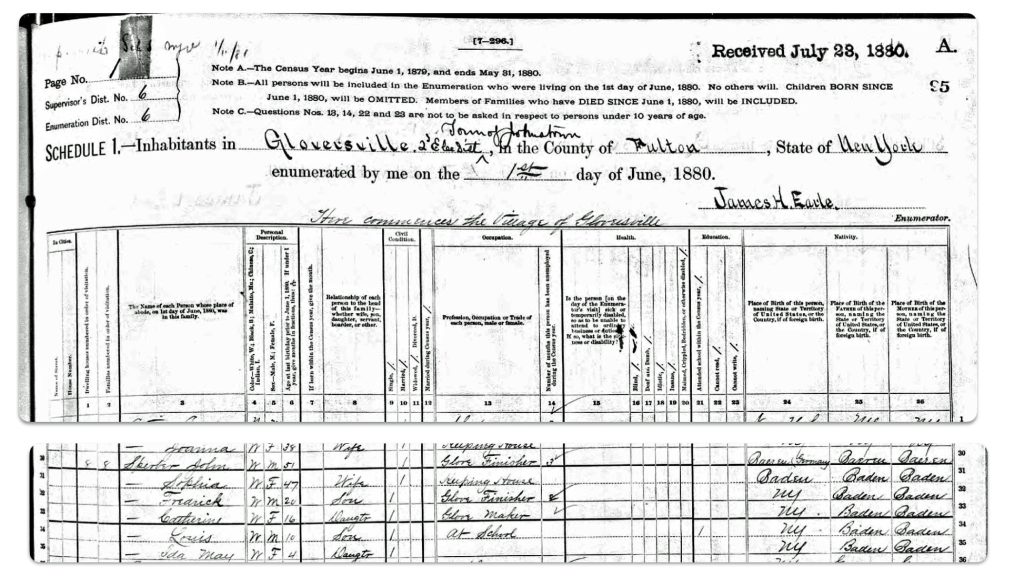

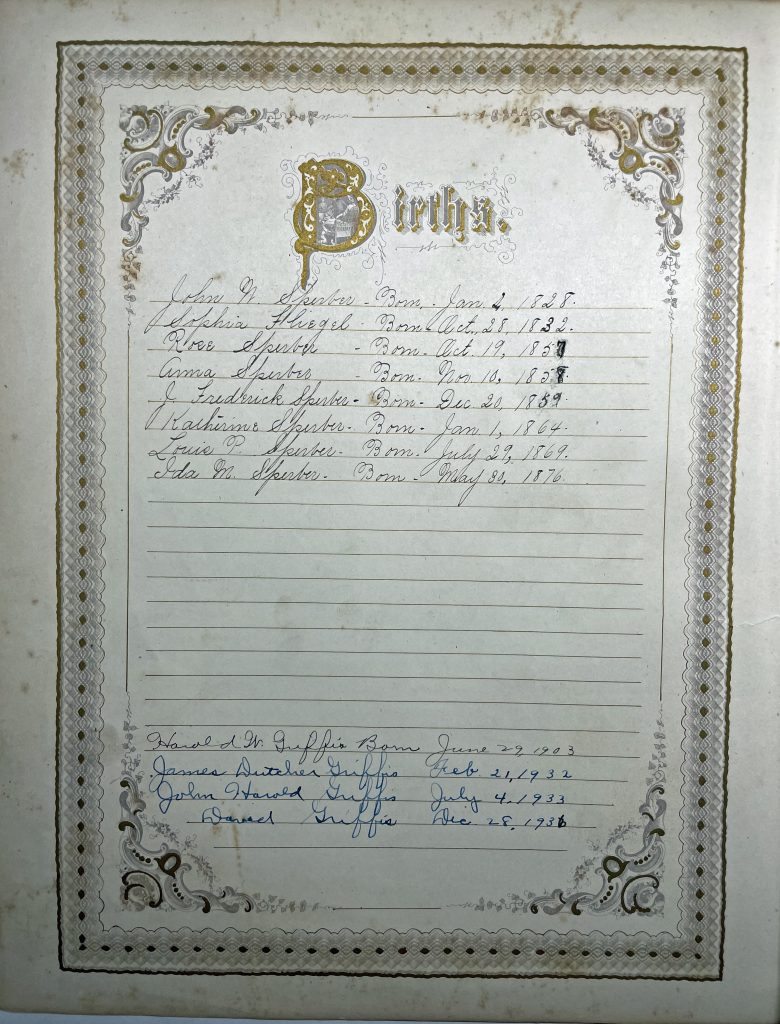

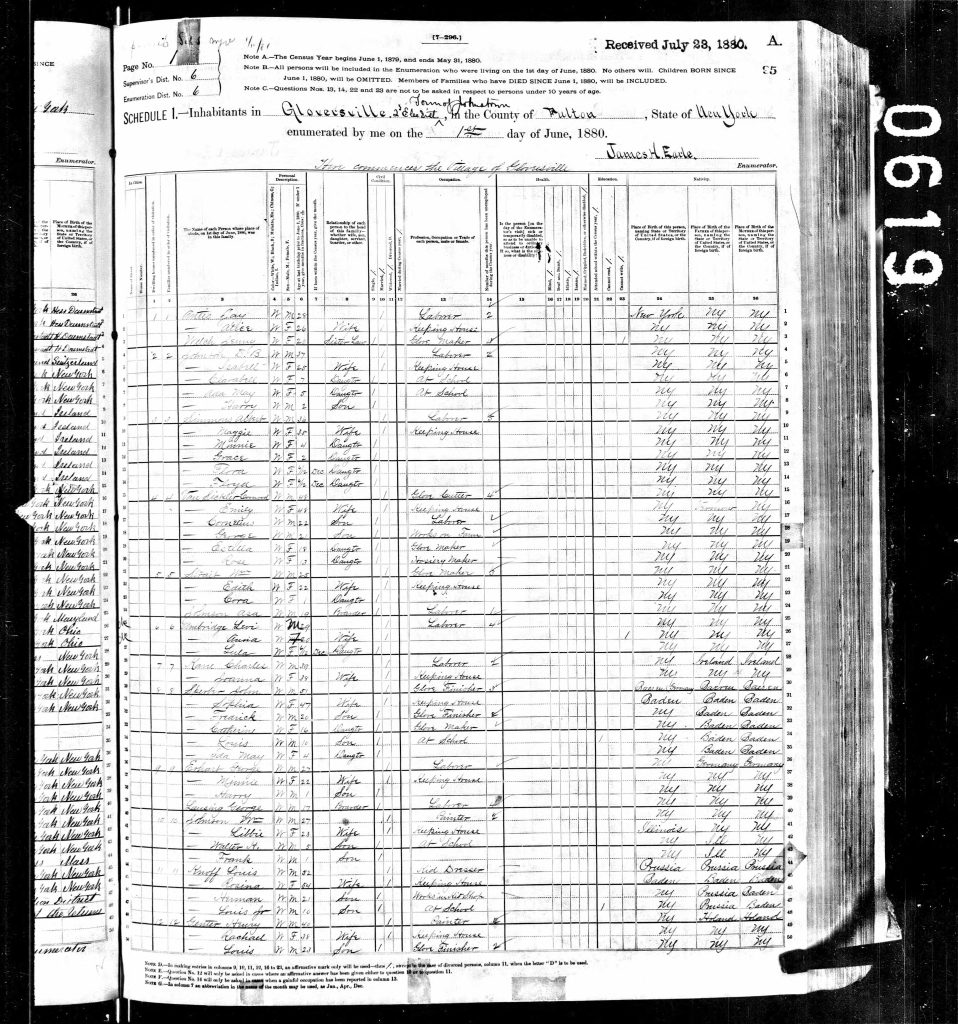

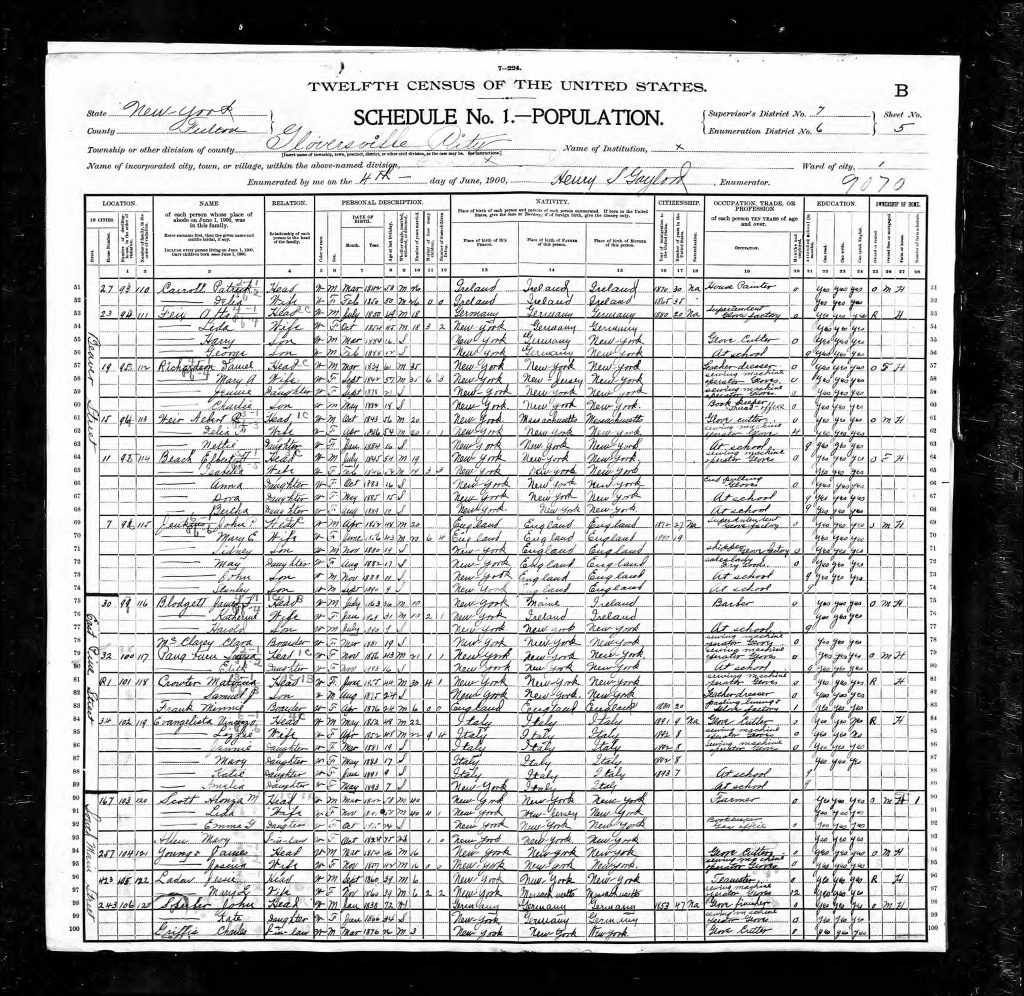

Based on family photographs and information in state and Federal census enumerations, we do know Johann Sperber was a glove maker between 1860 and 1900 when he established roots and raised a family in Fulton County, New York area. However, it is not known if:

- he was drawn to the Glove trade because of prior work experience or knowledge of glove making in the Baden-Baden area;

- he was aware of leather and glove making jobs through knowledge from correspondence from immigrants that settled in Fulton county;

- he obtained information or work experience once he landed and visited “Little Germany” in New York City on the Glove making trade in Fulton county;

- he had friends or acquaintances that migrated earlier to Fulton county; or

- he simply went to Fulton county based on other reasons and found a paying job in the burgeoning glove making market in Gloversville and Johnstown.

Leather Tanning and Leather Products in New York City

If Johan was ‘introduced’ to glove making shortly after he landed in Little Germany, New York City, it is not known how many German immigrants were possibly employed as glove makers in Little Germany in the mid 1850s. New York City likely had some small-scale glove making operations but they were associated with custom work and repairing. [23]

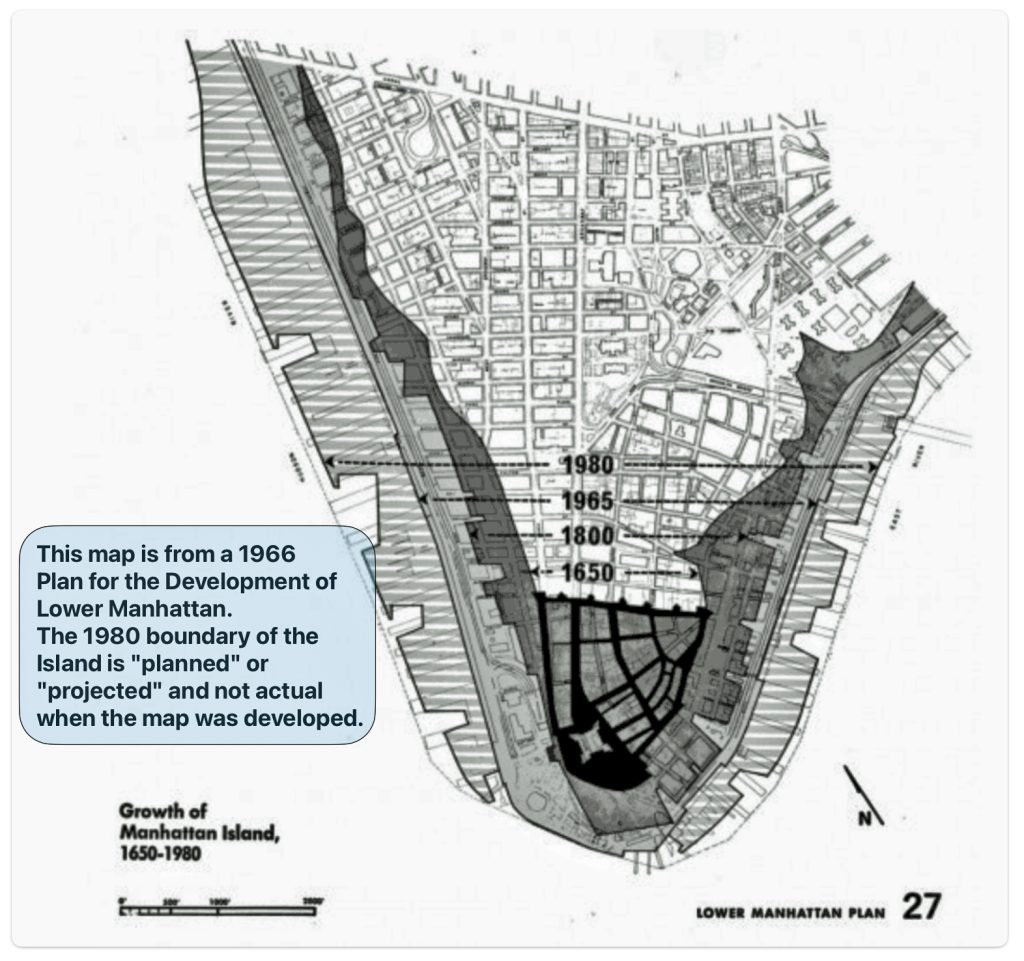

Map Eleven: Manhattan in Late 1700’s – New York Made and Swamp Land

While related, leather tanning and glove making are two distinct work processes and associated with different skill sets and occupations. The leather tanning industry had a long history in lower Manhattan. However, the industry was devoted to boot and shoe making and not glove making. Moreover, the areas conducive to leather tanning were originally near marsh and swamp land. (see map ten)

“New York City had its own leather tannery district called ‘the swamp’. During the colonial period, tanners plied their trade along Ferry, Frankfort, Gold Jacob, and Spruce Sts. in Manhattan’s swamp. The also made leather along the margins of Collect Pond. … Manhattan’s Swamp became the financial hub of the American leather industry. Tanners-turned merchants contracted with tanners through New York State, Pennsylvania and beyond to tan hides the merchants owned and to return the leather to New York City for sale.” [24]

In the early colonial days of New Amsterdam in the 1600s, much of Lower Manhattan consisted of swamps, streams, and wetlands. Tanneries were some of the first industries to be established around the swamps, such as the Collect Pond. Over the centuries, roughly eighty-five percent of Manhattan’s coastal wetlands and virtually all of its freshwater wetlands were lost as the island was developed. From the late 1600s through the early 1800s, Manhattan’s shoreline gradually expanded into the East River through deliberate landfilling. [25]

Maps from the 1600s through the 1700s show how the original coastline of Lower Manhattan, which corresponded to present-day Pearl Street, was extended several blocks into the East River, turning former swamps and wetlands into new made land. Much of the swamp land in Manhattan was eventually drained and filled, as reflected in maps eleven and twelve.

Map Twelve: Growth of Manhattan Island

https://ia804709.us.archive.org/6/items/lowermanhattanpl00wall/lowermanhattanpl00wall.pdf

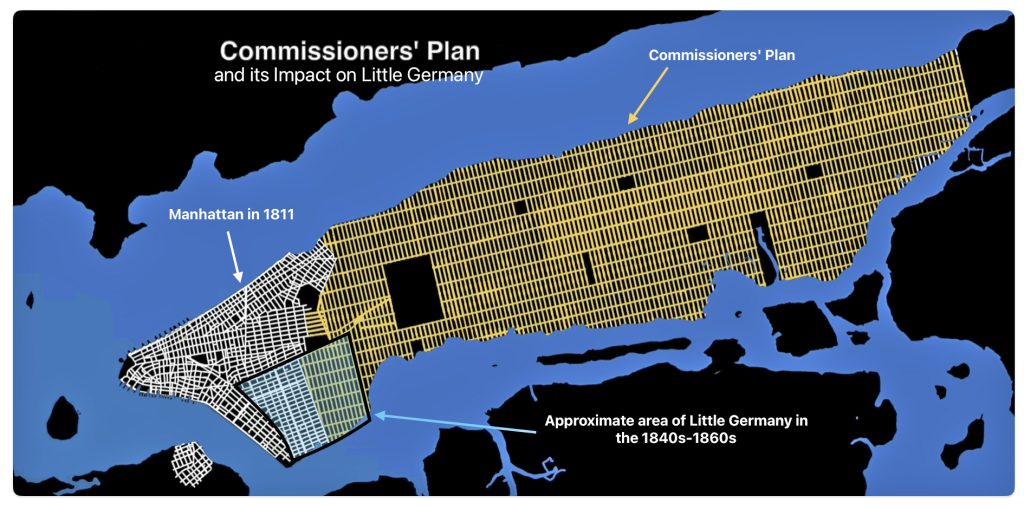

Impact of 1811 Commissioners’ Plan – New York City

Many of the tannery businesses that existed before Johann Sperber’s arrival to America also were affected by the implementation of the 1811 Commissioners’ Plan which reduced the acreage of swamp and marsh land.

“What made the grid plan, formally called the Commissioners’ Map and Survey of Manhattan Island, so farsighted was that in 1811 a vast majority of New York City’s population lived below what became Houston Street — tellingly named North Street then. … Yet while largely exempting the existing village of Greenwich, the visionary commissioners imposed their 2,000-block matrix on the forests, farms, salt marshes, country estates and common lands that extended north for nearly eight miles to what would become 155th Street, and expanded the city’s plotted land area by nearly fivefold.” [26]

Video: The Evolution of Manhattan 1811 – 1857

The 1811 Commissioners’ plan not only impacted the tanning industry, it had had an impact on all facets of urban life and growth in Manhattan. The area where many Germans settled in Manhattan between 1830 and 1860, Little Germany, was affected by the planned northward growth of New York, as informed by the Commissioners’ plan.

Map Thirteen: 1811 Commissions’ Plan and its Impact on the Growth of Little Germany

The Commissioners’ plan established Manhattan’s iconic rectangular street grid from Houston Street to 155th Street. It had a profound influence on the growth of Manhattan’s population. The Commissioners’ Plan provided a framework for Manhattan to grow from a city of 100,000 in 1811 to over 10 times that a century later. The grid was a catalyst for the real estate development, housing construction, and neighborhood formation that enabled Manhattan to absorb wave after wave of new residents in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. [27]

Glove Making in Upstate New York

The historical evidence suggests glove manufacturing in the early to mid-1800s was concentrated further upstate in Fulton County which became the undisputed center of the American glove making industry in the nineteenth and first third of the twentieth centuries. [28]

The rise of glove manufacturing from its humble origins in the early 1800s to a booming industry by the turn of the 20th century was the primary driver of Gloversville and Johnstown’s growth and prosperity for over one hundred and fifty years. It provided employment for a significant portion of the population, spurred development of supporting industries, and shaped the economic and social fabric of the community, establishing Fulton county as a major manufacturing center.

Johann Sperber may have obtained information on the economic experiences and opportunities in the Gloversville and Johnstown areas before he departed from Baden. He may have heard or read about these opportunities in letters from immigrants who started new lives in Fulton county.

Initially, most of Fulton county’s German population were descendants of Palatines who settled in the Mohawk Valley in the 1700s. Some of their descendants moved into Gloversville and Johnstown in the 1840s and 1850s to find work in the glove industry. [29]

“Fulton County became a polyglot community. Palatines from Germany had joined the Scots and English in early days , working as farmers through the county. In the early nineteenth century, English, Scots, and later a few French-trained glove makers made their way to the area along with New England Yankees. They were joined by a new wave of Germans, some trained as glovers and tanners … . “ [30]

“… (G)loves and mittens were first manufactured in the United States in what is now Fulton county. As the industry became of commercial importance the number of families that depended upon it for a livelihood increased, until nearly every man, woman, and child in the surrounding country became proficient in the making of some special part of the glove or mitten. Foreign cutters coming to this country naturally settled in Fulton county.” [31]

Influence of an Agricultural and Artisanal Background

It might not have been a ‘long stretch’ for Johann to consider working in various trades when he came to America. It is possible that Johann was familiar with or aware of other trades, such as glove making or textile production when he was in Baden.

As previously mentioned, Johann indicated to the Germania ship captain that his occupation in Baden was a cultivator, a farmer. Being a farmer may conjure various meanings of what is it to be a farmer. Being a farmer in Baden in the 1800s was different than a farmer in the United States.

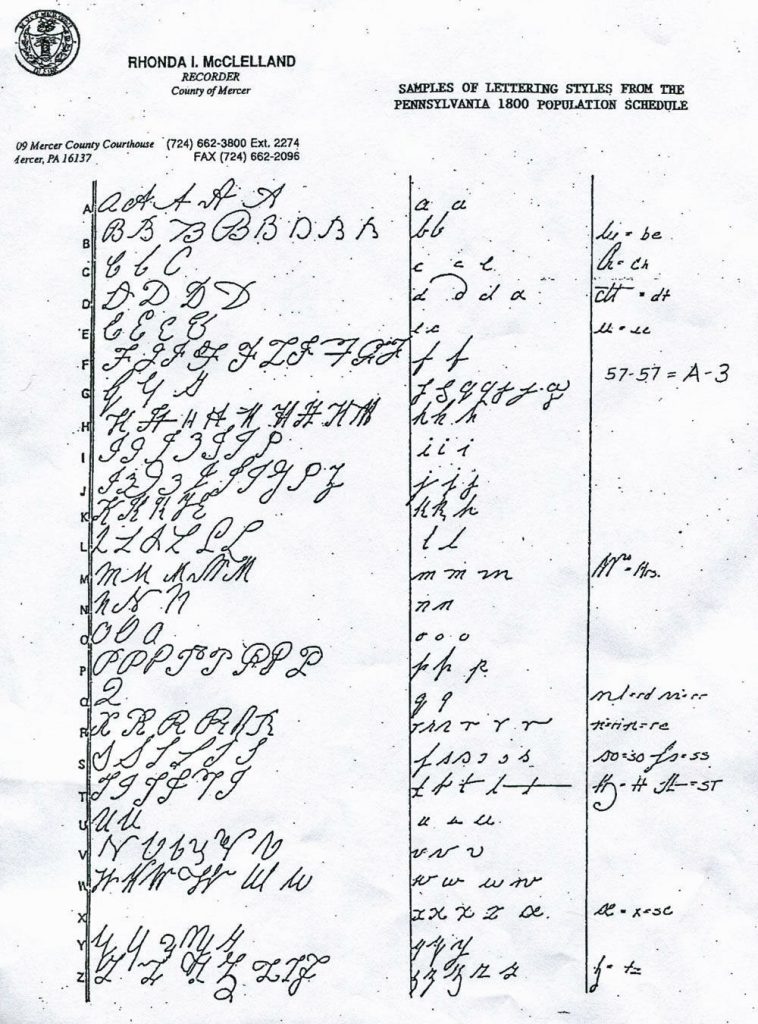

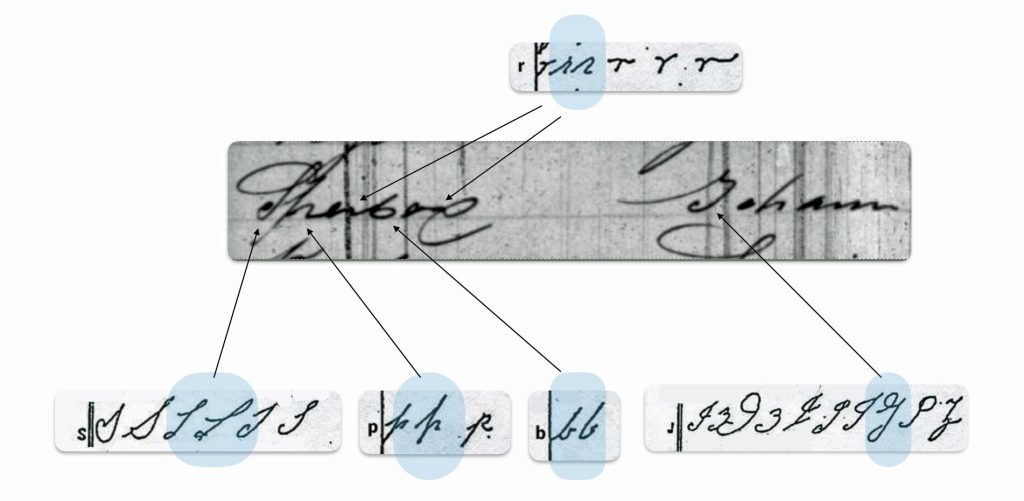

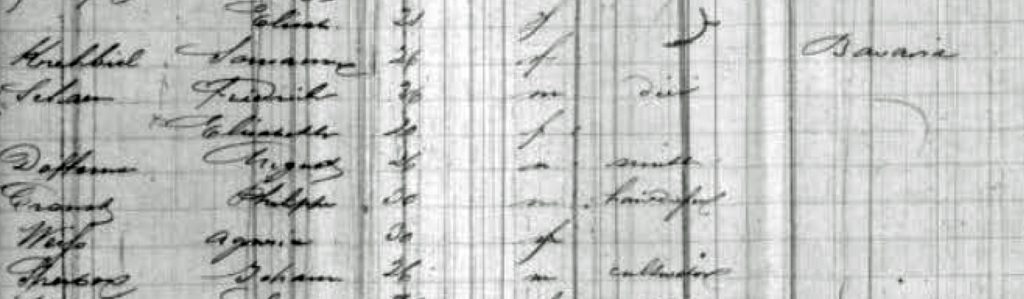

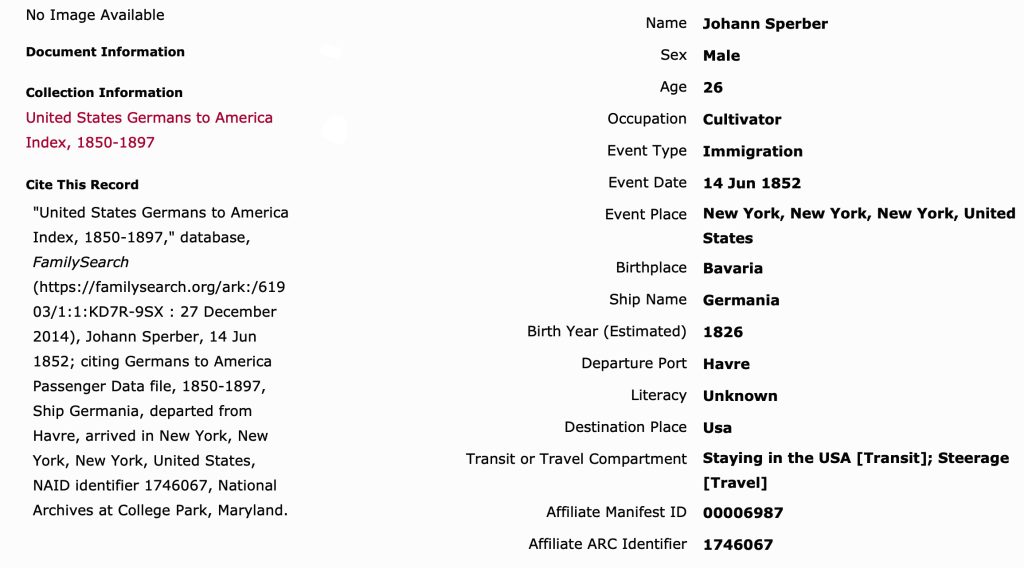

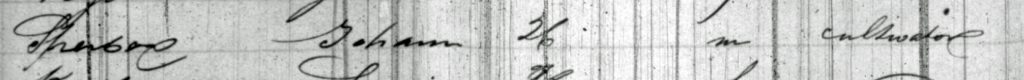

Blow Up of “Johann Sperber” – Germania Ship Manifest June 14 1852 Page 6 Line 13

Baden in the 1800s was a region of agricultural villages rather than scattered agricultural farmsteads that consisted of large tracts of land. The tracts of land for farmers in Baden were typically smaller than those found in America. While there was likely some variation, the typical Baden farm in the 1800s was quite small by American standards, averaging only around 8 hectares or 20 acres or less in size. The small scale farming suited the hilly terrain and fragmented land ownership patterns that existed in Baden during this period of the nineteenth century. [32]

In the early nineteenth century, Baden was a margraviate with an area of only about 1,300 square miles and a population of 210,000. The small population and territory likely contributed to the prevalence of small farms. The practice of partible inheritance, where land was divided equally among heirs, was prevalent in Baden during the nineteenth century. This led to the fragmentation of farm holdings into smaller parcels over generations.

The small farm sizes sometimes became problematic, as some farm sizes had become so small that they no longer could support a family in the 1830s-1840s. The growth of cottage industries and manufacturing in some areas of Baden provided alternative livelihoods, possibly reducing pressure to subdivide farms in those localities. But agriculture remained the main occupation for most. [33]

Agriculture was closely intertwined with artisanal trades. [34] Farmers often supplemented their income with home based cottage industry trades such as handloom linen or wool production. Based on data in 1861, Baden was second in the entire Zollverein (Confederation of German states) in the number of master weavers, with 54 per 10,000 inhabitants. [35]

The structure of the working environment of the glove making industry in Fulton county was vaguely similar to the proto-industrial work patterns in the western and central German states in the nineteenth century.. Proto-industrial work patterns involved the expansion of small-scale, home-based manufacturing of goods like textiles, ironware, pottery, and other products by peasant families. This cottage industry production was done alongside traditional agricultural work.

Glove making in Fulton county was similar to the proto-industrial patterns in Germany in terms of the ability to work from home or have a small shop behind the house. A major exception was that it was a primary occupation and not a supplemental work activity to agricultural pursuits. Workers could live a life solely on the wages of leather work, tanning or glove making in America while working from home.

“From the 1860s to as late as the 1930s, a man cutting gloves at home, with a wife and one other female relative to sew, constituted a glove shop. Their products were made under contract for larger shops or combined with the gloves of several small shops with sales handled by a common agent. Few of these shops advertised or are counted in the Census; almost none show up in the city directories.” [36]

Gloves and the Glove Trade in Europe

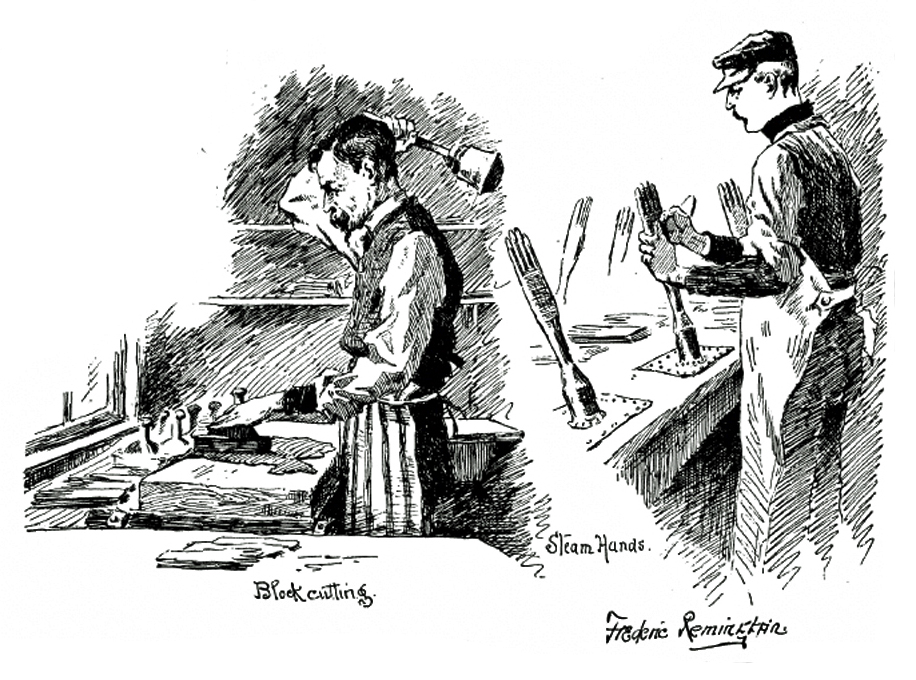

Glove Making

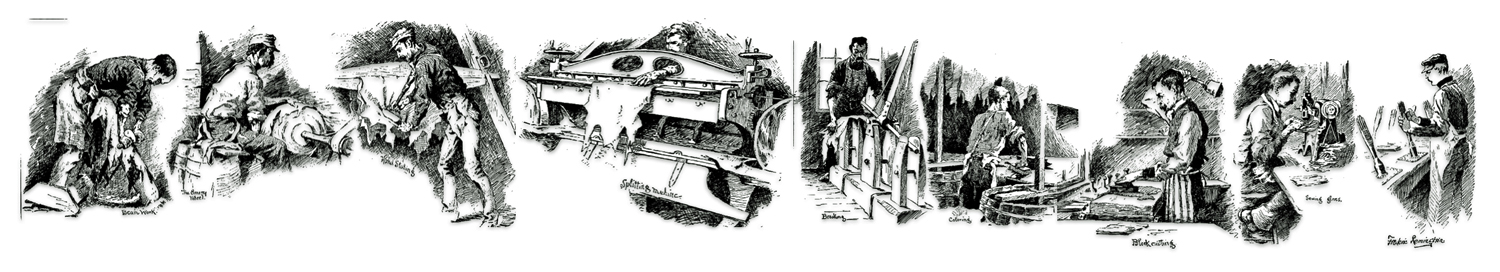

Source: This part of an illustration of the various facets of glove making by Fredrick Remington, for an article in the Harper’s Bazar: Glove Making in Fulton County, Harper’s Bazaar, Volume XX, Number 21, May 21, 1887, New York: Hearst Corporation, http://reader.library.cornell.edu/docviewer/digital?id=hearth4732809_1454_021#page/10/mode/1up

“(I)f an old adage is to be believed, for it used to be said : a glove to be good three realms must have contributed to it, Spain to prepare the skin, France to cut it, and England to sew it.” [37]

While glove making was not a major occupation, trade or craft, it had its roots in France, England, Germany, Spain and other countries.

“Gloving … enjoys an established claim to rank among the oldest of handicraft industries, and although machinery now enters very largely into all operations which the making of gloves involves, there are yet some processes calling for the exercise of mental intuition in association with manipulative expertness rather than for what one may term mere mechanical dexterity. Such is particularly true of glove-cutting.” [38]

Guilds for glove makers emerged in Europe as early as the 11th century. While the exact origins are unclear, there is evidence of glove makers’ guilds existing in major European cities like Paris from the eleventh century onward and with the London guild being formally established by the mid-fourteenth century.

The first Glovers’ Guild in Britain was established at Perth. The Perth glovers received a charter in 1165. Worchester, England established a glove making guild in 1571. The glovers of Grenoble, renowned for their glove making, organized themselves into Corporation des Gantiers in 1691. Nicot and Montpelier, France also had a long history of glove making. These guilds became increasingly prominent in the following centuries as the glove industry expanded. [39]

At the turn of the 1700s many of the trained glove makers from Grenoble and other towns of France, such as Blois, Vendome, and Grasse, migrated to Germany, Holland, and other countries due to religious persecution. They brought their glove making skills to other countires. In addition, protestant benefactors who supported the glove making industry brought their capital to these countries. [40] “Many of those who served their apprenticeship in Grenoble, and the master glovers holding the secrets of her art, probably became rivals, in other lands, of the city they once called their own.” [41]

“In the early part of the seventeenth century the manufacturers of gloves reached Germany, being brought there by French refugees from Grenoble, who introduced the art to Erlangen, Haberstadt, and Magdeburg.” [42]

Map fourteen gives sense of where the Grenoble refugee glove makers relocated in the German states. The map does not depict the political boundaries in the early seventeenth century. It is a 1850 map that depicts the locations of where the Glove makers from Grenoble relocated in Germany in relation to where Johann’s family from Baden. It gives a geographical sense of where the Grenoble refugees relocated.

Map Fourteen: Locations of French Refugees from Grenoble in German States [43]

In the seventeenth century, Paris and Grenoble enjoyed a monopoly of the glove markets in Europe. During the eighteenth century, however, these cities began to cope with Germany, Italy, Austria, and Russia in glove making. [44]

Tariffs and other trade practices, as early as the mid 1400s, impacted the growth and contraction of the glove making industry through the centuries. Commercial rivalries between various European countries and technological changes in the glove making process in the 1800s resulted in glovers migrating to the United States. In 1825, the lifting of the ban on the importation of French gloves into England had devastating economic effects on the glove makers in England and Ireland. Major glove making centers in Worcester, Woodstock, York, Hexham, Leominster, Yeovil, Limerick, Dublin, Cork, were decimated. [45]

Some say the word “glove” comes from the German Handschuh, meaning “hand-shoe”. [46] While there may be some merit to this view of the English derivation of the word, glove making did not originate in Germany. Nevertheless, the tanning of leather and glove making was not a foreign work process in Germany or to Germans.

Glove Making in America and the European Influence

Leather tanning became a prominent local industry in the area that became Fulton county due to the purity and abundance of water and the availability of hemlock bark as a source of tannin. [47]

“Unlike tanning in other regions of New York State, this was not hemlock bark tanning of cowhides for shoes and boots, but deer-skin tanning using other organic materials and manufacturing into gloves and clothing. It began with the first glove and mitten shops in Johnstown in 1808 and in what became Gloversville in 1810. “ [48]

The European influence of glove making and leather tanning in the area purportedly began with Sir William Johnson bringing 60 tanners and glove makers from Perth in Scotland in 1760.

“The manufacture of gloves and mittens in the United States dates from about the year 1760, when Sir William Johnson, chief agent of King George with the North American Indians, brought over from Scotland many families as settlers on his grants. Several families came from Perthshire and settled in the eastern part of what is now Fulton county, N. Y., calling the town Perth. Many of these settlers had been glove makers and members of the glove guild in Scotland, and brought with them glove patterns and the proper needles and threads for glove making.” [49]

There are some who argue that Johnson’s bringing glove makers from Scotland is a myth. “In 1895, the local newspaper was exuberantly extolled the town’s growth and industry in a historical review celebrating the centennial of the town’s founding. …The paper, following earlier historians, …erred in stating that Johnson brought the first glovemakers. No trained glovemakers arrived until well after his death… .” [50]

Notwithstanding the facts on both sides of the argument, immigrants of Scottish origin have been documented in living in Perth, New York. It is possible they had knowledge of glove making. Whether they had brought with them glove patterns and the proper needles and threads for glove making is an open question. [51]

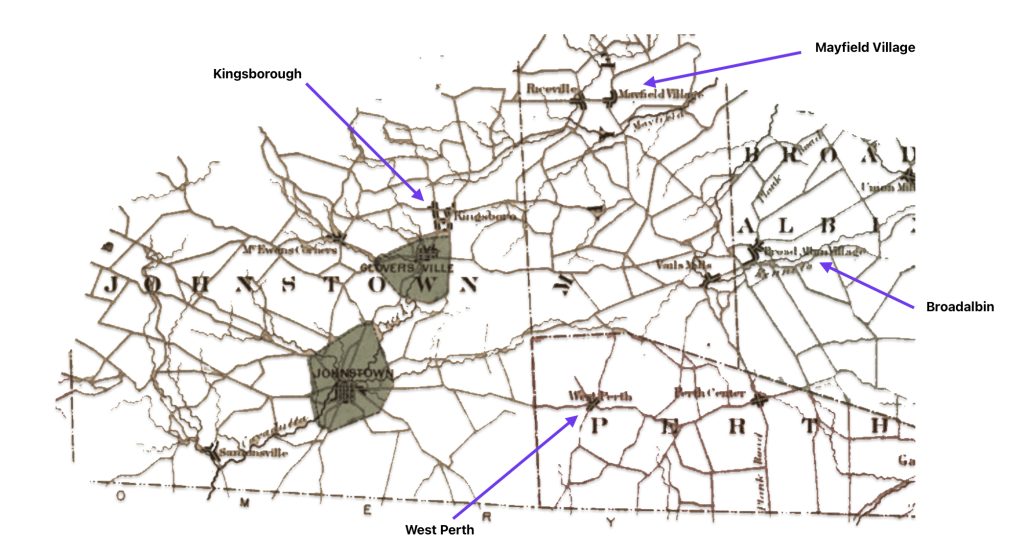

As reflected in map fifteen, an area north of Johnstown had a settlement called Kingsboro. Before the Revolutionary War, it was at the crossroads where settlers traded with farmers in Broadalbin and Mayfield. Kingsboro was populated by immigrants from Perthshire Scotland who brought their leather making skills to America. As mentioned when discussing glove making in Europe, Perthshire had a long tradition of glove making.

Map Fifteen: Locations of Broadalbin, Mayfield Village, Perth, Kingsborough, Gloversville and Johnstown

There were a number of documented European immigrants who settled in Gloversville and Johnstown in the mid nineteenth century came from glove making centers in Europe, bringing their skills and traditions with them. Several European countries had significant influence on the glove making industry in Fulton County, New York

“The first trained leatherworkers to come from France were two brothers, Lucien and Theophilus Bertrand. They arrived from Millau around 1840. They began tanning kidskins (the skins of young goats) in Johnstown. This may have marked the beginning of the production of finer grades of men’s gloves. “ [52]

“The Bertrands’ glove shop was the first of five manufacturing concerns established by trained French glovemen in Johnstown before the Civil War. The others were established by LouisJeannisson, Ferdinand Vassier, Jean Joseph Riton from Strasburg (his sons Charles J. and Eugene later formed the Riton Brothers glove concern), and by the father of Emile Julien. ” [53]

In Fulton County, New York, the leather tanning and glove making industries were growing in the 1840s and 1850s. Low overhead encouraged the proliferation of small glove making shops. They were as productive as the larger sized shops. For the small amount of funds required to set up a shop, the risk and investment resided in the purchase of leather. [54]

The 1840s marked the beginning of specialization in the industry. Separate parts of shops were established to accommodate the division of leather-making and glove-making operations. During the 1840s, as glovemen built separate structures for glove making and tanning or dressing of skins, these buildings became known as glove shops or a skin mill. [55]

However, despite the emerging specialization of leather tanning and glove making and the specialization of various roles of the glove making process (as depicted in the illustration at the top of this story), the smallest shops continued to be attached to the owners’ homes, as did most of those who produced leather and not gloves. The tradition of one manufacturer dressing deerskins and producing gloves continued through the next three decades along with the trend toward specialization an larger glove making firms.

“By 1850, the products of the industry had begun to change. Finer grades of men’s gloves were produced by the Bertrands with their imported kidskins. In the decade before 1860, others began to import kidskins for gloves, but the sturdy work gloves remained the bulk of the production along with deerskin mittens.” [56]

No longer were most of the gloves designed for ‘rough’ work, glove makers started to produce fine dress gloves for gentlemen and women. For example, Harry S. Cole, a glover who had worked for two prestigious firms in London, Fownes and Dents, came to Gloversville in 1857 to produce fine gloves made of calf skin. . [57]

“As the industry became of commercial importance the number of families that depended upon it for a livelihood increased, until nearly every man, woman, and child in the surrounding country became proficient in the making of some special part of the glove or mitten. Foreign cutters coming to this country naturally settled in Fulton county.” (Emphasis is mine) [58]

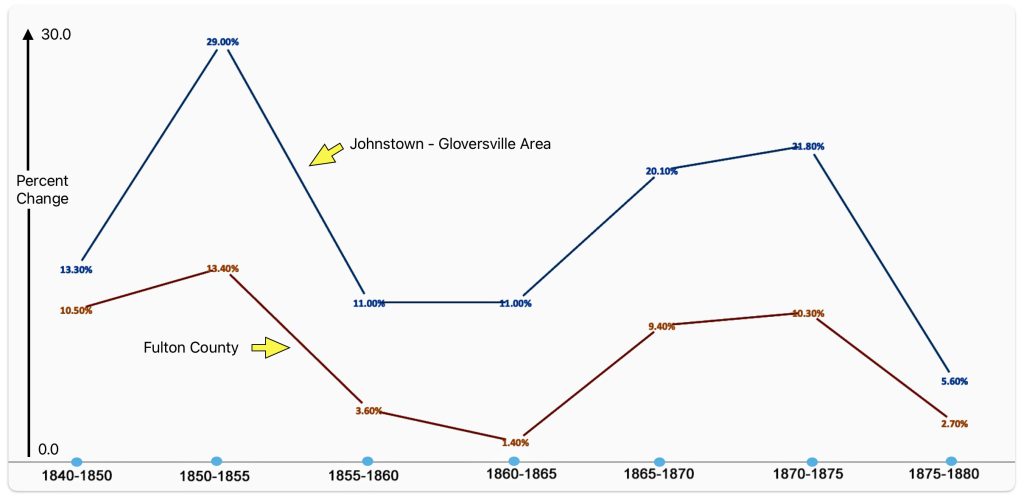

As indicated in table four, when Johan Sperber arrived in the Johnstown – Gloversville area in the mid 1800’s, he witnessed an area that had explosive growth which was largely attributed to glove making. The population in the county as well as the Johnstown – Gloversville area witnessed substantial growth between 1840 and 1880. The two towns increased in population in forty years by two hundred percent.

Depending on when Johan arrived in the area, Gloversville and Johnstown increased in size by a whopping 29 percent between 1850 and 1855; and by 11 percent between 1855 and 1860. Fulton county in general also witnessed substantial growth between 1850 and 1855. After the Civil War, Johnstown and Gloversville also experienced twenty percent population increases between 1865 and 1875.

Table Four: Population Size of Johnstown – Gloversville, NY

| Year | Population of Johnstown – Gloversville | Percent Change | Population of Fulton County | Percent Change | Johnstown- Gloversville as % of Fulton County |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 5,409 | 18,049 | |||

| 1850 | 6,131 | 13.3 % | 20,171 | 10.5 % | 30.4 % |

| 1855 | 7,912 | 29.0 % | 23,284 | 13.4 % | 34.0 % |

| 1860 | 8,811 | 11.0 % | 24,162 | 3.6 % | 36.5 % |

| 1865 | 9,805 | 11.0 % | 24,512 | 1.4 % | 40.0 % |

| 1870 | 12,273 | 20.1 % | 27,064 | 9.4 % | 45.3 % |

| 1875 | 15,689 | 21.8 % | 30,155 | 10.3 % | 52.0 % |

| 1880 | 16,626 | 5.6 % | 30,985 | 2.7 % | 53.7 % |

| 1840 – 1880 | 207.4 % | 71.6 % |

“Gloversville and Kingsboro remained part of the Town of Johnstown and census records lumped the two together until the 1880 Census, giving the appearance that Johnston was the more important.” [59]

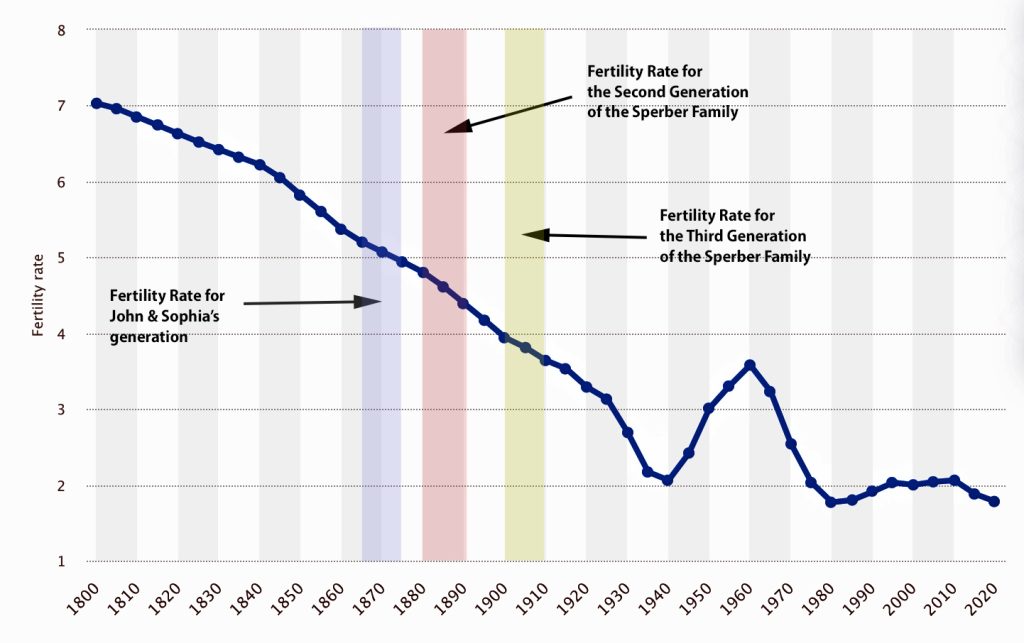

Chart one depicts the change rates found in table four. The chart visually depicts the similarity of the population changes between the Johnstown and Gloversville area and the entire county. Both areas experienced similar ups and downs but the magnitude of change was greater for the Johnstown and Gloversville area.

Chart One: Population Change Rates for the Johnstown-Gloversville Area and Fulton County Between 1840 and 1880

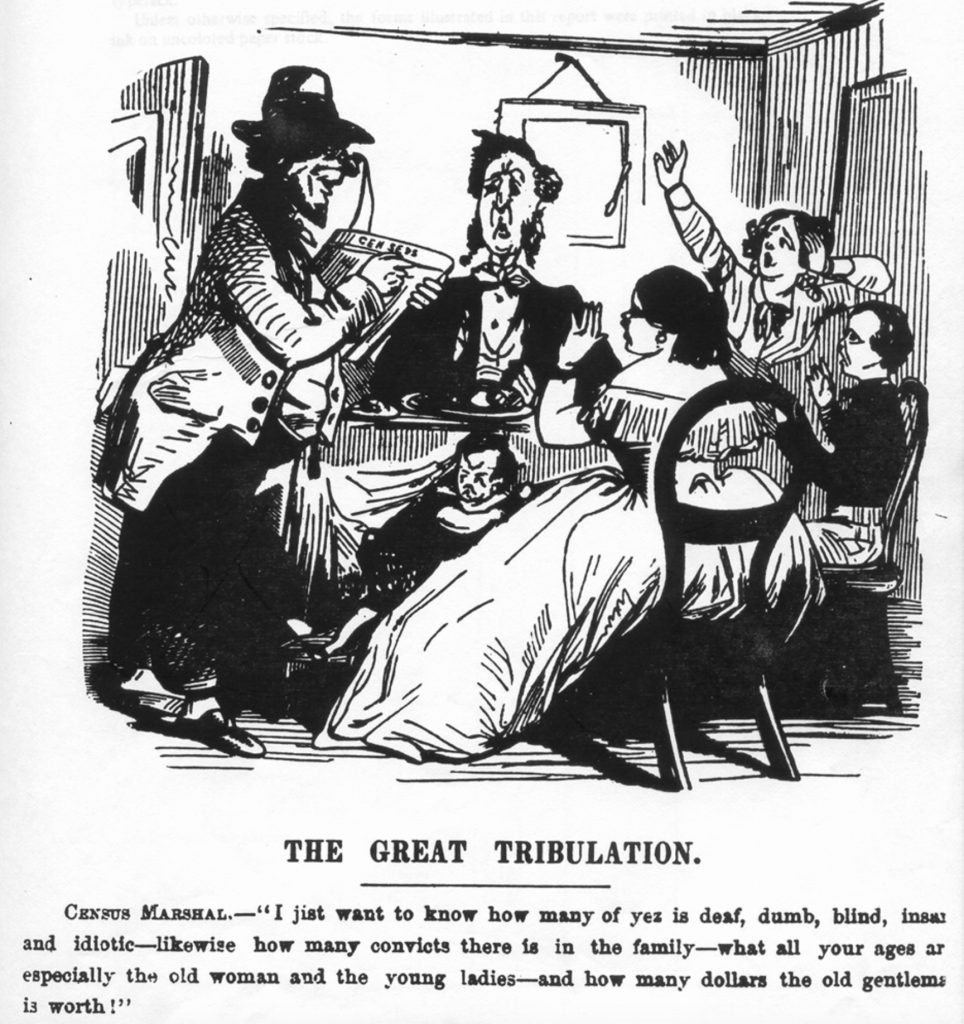

It is impossible to present comparative statistics on the glove making industry until the 1900 U.S. Federal census. Unfortunately, this hampers our understanding of Johann’s experiences when he started his family in the late 1850s and established a home in the 1860s. While the Civil War years were static with a sharp reduction of in new glove shops and a retrenchment of existing shops as people left to serve in the military, the war effort required the production of gloves.

Moreover, it is important to note that the reporting of ‘glove manufacturers’ was severely undercounted by due to the definition of manufacturing establishments and the nature of the work process and industry. [60]

Documenting the number of glove making establishments are probably undercounted and possibly misleading. It was observed in 1900 that “a great majority of the persons employed in this industry are pieceworkers ... . The making (of gloves) by “home workers” is an important and interesting phase o:f their manufacture, and since the inception of the industry much of the glove making· has been done at the homes of families, the members of which were unable, on account of various household duties, to take employment in a factory. Many of the large glove and mitten manufacturers of Gloversville and Johnstown, N. Y., employ delivery teams to distribute and collect the work of the home.” [61]

New York state and specifically Fulton county was the center of the glove making industry in America, starting in the early 1800s through the early 1900s. For example, New York state represented sixty-four percent of the total number of glove making establishments in 1900.

“In 1901, gloves were manufactured in 27 states, but, outside of Fulton county, N. Y., the product was mostly of the coarser and cheaper grades, as it is impossible to· induce the expert labor to emigrate to another section of the country.” [62]

Table five below provides quantitative data on the dominance of Gloversville and Johnstown, Fulton County and New York state on the production of gloves in 1900. For example, eighty-eight percent of all reported glove manufacturers were in New York state. Roughly seventy percent of all capital invested, wages, and workers were in New York state. Almost sixty percent of the products were also from New York state. Fulton country represented sixty percent of all glover workers in the nation. Gloversville represented sixty percent of all glove works in the nation and sixty-five percent of all glove workers within Fulton county.

Table Five: Comparative Summary of Statistics for Glove Making Enterprises in Futlon County, New York State and the United States: 1900

| Area | No. of Establish- ments | Capital Invested | Wages | Ave. No. Wage Earners | Dozens of pairs of gloves |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Total | 381 | 9,004,427 | 4,151,126 | 14,180 | 2,895,661 |

| New York State | 248 | 6,219,647 | 2,723,702 | 9,907 | 1,721,831 |

| % of U.S. | 88.3 | 69.1 | 65.6 | 70.0 | 59.5 |

| Fulton County | 166 | 5,517,850 | 2, 381,160 | 7,931 | 1,484,579 |

| % of U.S. | 43.6 | 61.3 | 57.4 | 60.0 | 51.3 |

| Gloversville | 101 | 3,660,383 | 1,695,035 | 5,183 | 925,440 |

| % of county | 60.8 | 66.3 | 71.2 | 65.4 | 62.3 |

| Johnstown | 49 | 1,686,604 | 580,146 | 2,316 | 398,657 |

| % of county | 29.5 | 30.6 | 24.4 | 29.2 | 26.9 |

| Outside of cities | 16 | 170,863 | 105,979 | 432 | 160,482 |

| % of county | 9.6 | 3.1 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 10.8 |

Although the manufacture of gloves was of commercial importance since the early 1800s, the 1850 census was the first time where statistics were available on glove making firms for analysis. Table six bellow provides a high level view of the size of the glove making industry in the United States for the last half of the nineteenth century. The increase between 1860 and 1870 was attributable to the demand for gloves during the Civil War.

Table Six: Glove Making Establishments in the United States 1850 – 1900 [63]

| Census Year | Number of Glove Making Establishments | Percent Increase |

|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 110 | |

| 1860 | 126 | 14.5 |

| 1870 | 221 | 75.4 |

| 1880 | 300 | 35.7 |

| 1890 | 224 | 8.0 |

| 1900 | 397 | 22.5 |

The ability to drill down into the data is limited. Data for the earlier census years was not as detailed as found in the 1900 U.S. census. While the data is fifty years after Johan’s arrival to the United States, it is interesting to note that of the total number of glove making ‘establishments’ reported in 1900 is rather small compared to other categories of manufacturing.

Of the 397 establishments making gloves in 1900, 222 of the ‘establishments’, or 56 per cent, were operated by individuals. The remaining· 125 were what we commonly think of as commercial establishments. They were limited partnerships or incorporated companies. Also 96 percent of the establishments in 1900 were producers of leather gloves.

It is noteworthy that “over 60 per cent of the glove and mitten establishments of Fulton county were located in Gloversville. This localization of the industry is not due to economic conditions, such as low price of coal or to advantageous freight rates, but it may be attributed to the nature of the industry itself, and to the circumstances connected with its inception in the United States. …”As the industry became of commercial importance the number of families that depended upon it for a livelihood increased, until nearly every man, woman, and child in the surrounding country became proficient in the making of some special part of the glove or mitten. Foreign cutters coming to this country naturally settled in Fulton county.” (Emphasis is mine), [64]

So Why Did Johan Sperber End His Journey in Gloversville?

There were a number of possible influences that led Johann Sperber to the Gloversville, New York area. An overarching migratory influence was knowledge of past generations from his home area in Baden that came to the Mohawk Valley. This influence may have provided a general vague influence of where to go in America. He may have had contemporary personal contacts that came to the Mohawk Valley, providing information on employment opportunities.

Johann may have stopped and stayed in New York City when getting off the boat. He may have stayed in Little Germany to get his bearings, earn some money, and gain a better understanding of job prospects in the Mohawk Valley. He may have learned on the economic prospects of the glove making trade while in New York City.

While many towns and cities along the Mohawk Valley offered economic opportunities, many of those opportunities were in emerging industries in manufacturing. Johann may have been drawn to the working arrangements associated with the glove making practices in Gloversville. The glove making industry retained a semblance of the characteristics of cottage industries in Baden. [65]

“What is particularly remarkable is that even during its height, the manufacture of gloves never became one of mass production. The creation of each pair of leather gloves was the work of an individual craftsman. “The Glove Cutter” was personally responsible for the quality of his product. A middle management level was never developed in the glove industry. Each owner of any one of dozens of glove companies, both large and small, had a personal relationship with his “cutters” and sewers or “makers”. Quality was a matter of personal pride.” [66]

“What is amazing is the number of men who set up glove shops and skin mills. This great number of entrepreneurs distinguishes glove-making throughout its entire tenure in Fulton county. Large shops arose, and they, too, were numerous, but no single man or family ever dominated local industry.

“The smallest shops continued to be attached to the owners’ homes, as did most of those who produced leather and not gloves. However, the tradition of one manufacturer dressing deerskins and producing gloves continued through the next three decades along with the trend toward specialization.” [67]

Perhaps Johann was attracted to Gloversville due to tradition, to the economic prospects of the future in glove making and to the comfort of past experiences and working relationships that were reminiscent of the homeland. [68]

Sources

Feature Photograph: This is ‘rearrangement’ of an illustration of the various facets of glove making that was done by Fredrick Remington, for an article in the Harper’s Bazar: Glove Making in Fulton County, Harper’s Bazaar, Volume XX, Number 21, May 21, 1887, New York: Hearst Corporation, http://reader.library.cornell.edu/docviewer/digital?id=hearth4732809_1454_021#page/10/mode/1up

Frederic Sackrider Remington (1857-1926) was a painter, illustrator, and sculptor who specialized in depicting the Old West. Frederic Remington and his wife Eva Adele Canton were both born in Canton, New York. Eva grew up in Gloversville and the couple got married after Eva’s father finally accepted Frederic’s second request for her hand in marriage in Gloversville on October 1st, 1884. Aside from his paintings, Remington also produced more than 3,000 drawings, 22 bronze sculptures, a Broadway play, and more than 100 articles.

Nicole Todd, Love Stories: Frederic and Eva Remington, 14 Feb 2017,Buffalo Bill Center of the West, https://centerofthewest.org/2017/02/14/love-stories-frederic-eva-remington/

Frederic Remington, Timeline, Carter Museum, https://www.cartermuseum.org/artists/frederic-remington/frederic-remington-timeline

Remington also completed a drawing of the tanning process. See “A Day in the Tannery”, Harper’s Weekly, January 25, 1890, Vol 34, No. 1727, New York: Harbor & Bros., P72 & 74 https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015011446161&view=1up&seq=92

[1] Kamphoefner, Walter D., The Westfalians: From Germany to Missouri, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987, Page 81

Two years prior to Johann’s arrival, in 1850, New York State had the largest ‘base’ of first generation Germans reported by the Federal census. This reflected the effects of German migration in the prior twenty years. Ohio was closely behind New York state. This reflected the migration patterns from New York city up the Hudson river and across the state to Buffalo and onward to the great lakes region.

As the quote from Kamphoefner indicates, New York City was the gateway to America and the Erie canal and developing railways in New York facilitated migration to Ohio, Indiana and Illinois and Wisconsin.

Similar to New York State, Pennsylvania, particularly Philadelphia and its outlying areas, also had a long history of German migration in the 1700s and 1800s. Germans sailing to New Orleans settled in Lousiana.

Foreign Born in Germany by State 1850

| State Rank (Territory) | State | Foreign Born German | Percentage of Total in United States | Cumulative Pecentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | New York | 118,398 | 20.7 | 20.7 |

| 2 | Ohio | 111,257 | 19.4 | 40.1 |

| 3 | Pennsylvania | 78,592 | 13.7 | 53.8 |

| 4 | Missouri | 44,353 | 7.7 | 61.5 |

| 5 | Illinois | 38,160 | 6.7 | 68.2 |

| 6 | Maryland | 26,936 | 4.7 | 72.9 |

| 7 | Indiana | 25,584 | 4.5 | 77.4 |

| 8 | Louisiana | 17,507 | 3.1 | 80.5 |

| 9 | Kentucky | 13,697 | 2.4 | 82.9 |

| 10 | New Jersey | 10,686 | 1.9 | 84.8 |

| 11-32 | Remaining states | 88,055 | 15.3 | |

| (4) | Territories | 561 | 1.0 | |

| Total | 573,225 | 100.00* |

[2] Ira Glazier, Ed., Germans to America Series II: Lists of Passengers Arriving at U.S. ports in the 1840s, Volume 6 April 1848 – October 1848, Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc 2003, Page xiv Page xiv

[3] Page, Thomas W. “The Transportation of Immigrants and Reception Arrangements in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 19, no. 9, 1911, pp. 736. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1820349

[4] James Boyd, The Rhine Exodus of 1816/1817 within the Developing German Atlantic World, The Historical Journal, vol. 59, no. 1, 2016, page 102. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24809839

[5] The Great Western Turnpike ran along the south side of the Mohawk River, while the Mohawk Turnpike ran along the north side. In modern times, NY Route 5 follows the path of the old Mohawk Turnpike along the northern bank of the Mohawk River, while NY Route 5S follows the path of the old Great Western Turnpike along the southern bank.

Green, Nelson, ed, History of the Mohawk Valley: Gateway to the West 1614-1925, Chapter 101: The Mohawk Turnpike and Valley Highway System, Chicago: S.J. Clark Pub. Co., 1925, PP 1465 – 1480, https://www.schenectadyhistory.org/resources/mvgw/history/101.html

Green, Nelson, The Old Mohawk Turnpike Book, Fort Plain: Nelson Green, 1924, https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Old_Mohawk_Turnpike_Book/fT9KAAAAMAAJ?hl=en

Mohawk or Iroquois Trail, FamilySearch Wiki, FamilySearch,This page was last edited on 24 October 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Mohawk_or_Iroquois_Trail

[6] Albany Post Road, Research Wiki, This page was last edited on 5 December 2022, FamilySearch, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Albany_Post_Road

Dollarhide, William, Map Guide to American Routes, 1735-1815, Utah: AGLL, Inc, 1997,Pages 2-4 & 7

Albany Post Road, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 20 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albany_Post_Road

Old Albany Post Road, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 14 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Albany_Post_Road

At the time of his arrival to New York City, it was possible to utilize rail service from New York City to Albany New York.

Capsule History of the Old Albany-New York Post Road, Old Road Society of Philipstown. Retrieved 23 May 2024, http://www.oldrdsoc.org/orshist.htm

A Short History of of the Origin and Development of the Public Works Concept in the State of New York, New York Public Works, 1965, Page 7, https://www.dot.ny.gov/programs/dot-40th-anniversary/repository/A%20Short%20History.pdf

List of turnpikes in New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 8 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_turnpikes_in_New_York

New York Turnpikes, Research Wiki, FamilySearch, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/New_York_Turnpikes

[7] Old Albany Post Road, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 14 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Albany_Post_Road

[8] History of Albany, New York (1784–1860), Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 24 August 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Albany,_New_York_%281784–1860%29

[9] Green, Nelson, ed, History of the Mohawk Valley: Gateway to the West 1614-1925, Chapter 101: The Mohawk Turnpike and Valley Highway System, Chicago: S.J. Clark Pub. Co., 1925, PP 1465 – 1480, https://www.schenectadyhistory.org/resources/mvgw/history/101.html

Green, Nelson, The Old Mohawk Turnpike Book, Fort Plain: Nelson Green, 1924, https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Old_Mohawk_Turnpike_Book/fT9KAAAAMAAJ?hl=en

[10] Map and description of map from:

Greene, Nelson, History of the Mohawk Valley: Gateway to the West 1614 – 1925, Volume I, Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1925, Page 19, https://www.schenectadyhistory.org/resources/mvgw/maps/hudson_valley_map.html

[11] Loveday Jr.,William G. The Evolution of a County, Fulton County New York, Page Accessed Mar 6 2024, https://www.fultoncountyny.gov/evolution-county

[12] The Kingsborough Patent was a land grant in colonial New York during the 18th century. The patent contained parts of the current towns of Johnstown, Mayfield, and Ephratah in present-day Fulton County, New York, including the cities of Johnstown and Gloversville.

Map of Kingsborough, comprehending the Patents of James Stewart and A. Stevens. Map #72, New York State Archives, Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/objects/36596

Thomas Cowperthwait & Co., A New Map of Germany, 1850, American made map of Germany, published in Philadelphia for the New Universal Atlas of the World of 1852, https://nwcartographic.com/products/1850-a-new-map-of-germany?variant=675778261

History of Fulton County, Fulton County New York, Page accessed Mar 6 2024, https://www.fultoncountyny.gov/brief-history-fulton-county

Fulton County, New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 9 June 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fulton_County,_New_York

[13] History of Fulton County, Fulton County New York, Page accessed Mar 6 2024, https://www.fultoncountyny.gov/brief-history-fulton-county

[14] Loveday Jr.,William G. The Evolution of a County, Fulton County New York, Page Accessed Mar 6 2024, https://www.fultoncountyny.gov/evolution-county

History of Fulton County, Fulton County New York, Page accessed Mar 6 2024, https://www.fultoncountyny.gov/brief-history-fulton-county

Fulton County, New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 9 June 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fulton_County,_New_York

Montgomery County, New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 12 June 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Montgomery_County,_New_York

Tryon County, New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 26 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tryon_County,_New_York

Lisa Slaski, Lisa,History, Fulton County MyGenWeb, https://fulton.nygenweb.net/history/index.html

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Fulton”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 24 Aug. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Fulton-county-New-York

[15] Canal History, New York State, https://www.canals.ny.gov/history/history.html ,

Finch, Roy, The Story of the New York State Canals, https://www.canals.ny.gov/history/finch_history.pdf

Canal History, New York State, https://www.canals.ny.gov/history/history.html

Klein, Christopher, 8 Ways the Erie Canal changed America, July 19, 2016, updated Oct 25, 2023, History, https://www.history.com/news/8-ways-the-erie-canal-changed-america

North, Edward P. “The Erie Canal and Transportation.” The North American Review, vol. 170, no. 518, 1900, pp. 121–33. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25104942

Bahret, James L. “Growth of New York and Suburbs Since 1790.” The Scientific Monthly, vol. 11, no. 5, 1920, pp. 404–18. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/6415

Erie Canal, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 2 June 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erie_Canal

Keene, Michael, The Psychic Highway: How the Erie Canal Changed America. Fredericksburg, Va.: Willow Manor Publishing 2016

[16] The Growth of Railroads in the Capital District, https://vizettes.com/kt/rr/cd-rr-history/index.htm

[17] Drake, Ira S, and Cowperthwait & Co Thomas. Mitchell’s new traveller’s guide through the United States, showing the rail roads, canals, stage roads &c. with distances from place to place. Philadelphia, Thomas, Cowperthwait & Co., 1853, created 1848. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/gm70005367/

Drake, Ira S., Mitchell’s new traveller’s guide through the United States, showing the rail roads, canals, stage roads &c. with distances from place to place, Philadelphia, Thomas, Cowperthwait & Co., published 1853, created 1848.

Albany and Schenectady Railroad, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 13 December 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albany_and_Schenectady_Railroad. The railroad was incorporated on April 17, 1826, as the Mohawk & Hudson Company and opened for public service on August 9, 1831. On April 19, 1847, the company name was changed to the Albany & Schenectady Railroad. The railroad was consolidated into the New York Central Railroad on May 17, 1853.

Saratoga and Schenectady Railroad, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 11 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saratoga_and_Schenectady_Railroad. The line was opened from Schenectady to Ballston Spa on July 12, 1832, and extended to Saratoga Springs in 1833 for a total of 20.8 miles (33.5 km).

Troy & Schenectady Railroad, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 3 March 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Troy_%26_Schenectady_Railroad The building of the road began in 1841, and trains began running from Schenectady to Troy, New York in the fall of 1841 (21.0 miles)

Rensselaer and Saratoga Railroad, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 7 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rensselaer_and_Saratoga_Railroad. It completed 25.2 miles (40.6 km) between Troy and Ballston Spa on March 19, 1836.

Troy and Boston Railroad, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 7 November 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Troy_and_Boston_Railroad. (1852)It completed a railroad from Troy, New York to the Vermont state line (35 miles) in 1852.

Boston and Albany Railroad, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 17 March 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boston_and_Albany_Railroad

Palmer, Richard, Three Rivers Hudson~Mohawk~Schoharie, http://threerivershms.com/utica-schenRR.htm

Greene, Nelson, ed, History of the Mohawk Valley: Gateway to the West 1614-1925 Volume II, Chapter 87: History of the New York Central Railroad and Other Valley Lines, Chicago: S.J. Clark Pub. Co. 1925, PP 1288-1306, https://www.schenectadyhistory.org/resources/mvgw/history/087.html

Larkin, F. Daniel, Historical Context: The Railroads and New York’s Canals, Consider the Source New York, Page accessed May, 3, 2024, https://considerthesourceny.org/using-primary-sources/erie-canal-new-yorks-gift-nation/chapter-9-other-new-york-canals/historical-context-railroads-and-new-yorks-canals

[18] Greene, Nelson, Chapter 103: Mohawk Manufacturing Statistics, History of the Mohawk Valley: Gateway to the West 1614 – 1925, Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1925, Pages 1502 – 1504, https://www.schenectadyhistory.org/resources/mvgw/history/103.html also https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89077224962&view=1up&seq=11

Grist mills, saw mills, tanneries, blacksmith shops, fulling and carding mills, asheries, etc., were built at nearly all Valley centers, in the settlement period, from 1661 to 1800. The following are examples of principal industries, in which the great majority of the wage earners of the valley were engaged prior to and up to when Johann Sperber migrated to the area.

See also:

Utica, New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 15 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utica,_New_York

Johnstown, New York, Wikipeadia, This page was last edited on 5 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johnstown,_New_York

Gloversville, New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gloversville,_New_York

Utica, New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 15 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utica,_New_York

Amsterdam, New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 15 March 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amsterdam,_New_York

Little Falls, New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 4 March 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Falls,_New_York

[19] Greene, Nelson, Chapter 103: Mohawk Manufacturing Statistics, History of the Mohawk Valley: Gateway to the West 1614 – 1925, Volume II, Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1925, Page 20

[20] Utica, New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 9 June 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utica,_New_York

Koch, Daniel, Land of the Oneidas: Central New York State and the Creation of America, From Prehistory to the Present. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2023

Rome, New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 16 March 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rome,_New_York

[21] Utica, New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 9 June 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utica,_New_York

[22] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany: Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City 1845-80, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990, Page 64

[23] Hunt, Arthur L., Twelfth Census of the United States, Census Bulletin No. 175, Washington D.C. May 24, 1902, Manufactures: Gloves and Mittens – Leather, Data from Table One, Page 10. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1900/bulletins/manufacturing/175-manufactures-gloves-mittens-leather.pdf

F. W. Beers, F.W. , History of Montgomery and Fulton counties, N.Y. : with illustrations and portraits of old pioneers and prominent residents, New York : F.W. Beers & co., 1878, Pa https://archive.org/details/historyofmontgom00beer/page/n459/mode/2up

Barbara McMartin, The Glove Cities: How A People and Their Craft Built Two Cities, NY: Lake View Press, 1999

Gloversville, New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 21 May 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gloversville,_New_York#:~:text=The%20city%20would%20become%20the,official%20name%20of%20the%20community.

Twelfth Census of the United States, Census Bulletin No. 175, Washington D.C. May 24, 1902, Manufactures: Gloves and Mittens – Leather, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1900/bulletins/manufacturing/175-manufactures-gloves-mittens-leather.pdf

Washington Frothingham, History of Fulton County : embracing early discoveries, the advance of civilization, the labors and triumphs of Sir William Johnson, the inception and development of the glove industry; with town and local records, also military achievements of Fulton county patriots, Syracuse, N.Y. : D. Mason, 1892, Chapter XVI, The Glove Industry, Pages 154 – 170 https://archive.org/details/cu31924083983951/page/n173/mode/2up

[24] Eisenstadt, Peter, ed, , Tanning Industry, The Encyclopedia of New York State, Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2005, Page 1526 – 1527

[25] Schifman, Joathan, Water, Water Everywhere, and Not a Drop to Drink, Smithsonian Magazine, Nov 25 2019, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-new-york-city-found-clean-water-180973571/

Great Swamp (New York), Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 25 October 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Swamp_%28New_York%29

Young, Michelle, Fun Maps: The Slips and Swamps of Early NYC, untapped new york, https://untappedcities.com/2015/08/20/fun-maps-the-slips-and-swamps-of-early-nyc/

Johnson, Amy, The Saw-Kill and the Making of Dutch Colonial Manhattan, Sawkill Lumber Co. ,https://www.sawkill.nyc/history-new-york-city/

History of Manhattan, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 10 April 2024, History_of_Manhattan

Norcross, Frank W., A History of the New York Swamp, New York: The Chiswick Press, 1901, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/98/A_history_of_the_New_York_Swamp_%28IA_cu31924030127181%29.pdf

Urbanus, Jason, New York’s Original Seaport, Archaelogy Magazine, Sep / Oct 2015, https://archaeology.org/issues/online/collection/new-york-original-seaport/

[26] Roberts, Sam, 200th Birthday for the Map That Made New York, Mar 20, 2011, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/21/nyregion/21grid.html

[27] Gannon, Devin, On this day in 1811, the Manhattan Street Grid became official, Mar 22 2017, 6sqft, https://www.6sqft.com/204-years-ago-today-the-manhattan-street-grid-became-official/

Commissioner’s Plan of 1811, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 4 June 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commissioners%27_Plan_of_1811

The 1811 Plan, The Greatest Grid: The Master Plan of Manhattan 1811 – Now, Museum of the City of New York, https://thegreatestgrid.mcny.org/greatest-grid/making-the-plan

Yu, Kerry, The Greatest Grid: History of the Mater Plan of Manhattan, Feb 7, 2019, Information Visualization, Student Work at the School of Information, Pratt Institute, https://studentwork.prattsi.org/infovis/labs/the-greatest-grid-history-of-the-master-plan-of-manhattan/

McQuilkin, Alexander, The Rise and Fall of Manhattan’s Density, Urban Omnibus, Pblication of the Architectual League of New York, https://urbanomnibus.net/2014/10/the-rise-and-fall-of-manhattans-density/

Howe, Richard, Notes On The Commissioners’ Future City, Nov 9, 2013, The Gothan Center for New York City. History, https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/notes-on-the-commissioners-future-city

Roberts, Sam, 200th Birthday for the Map That Made New York, Mar 20, 2011, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/21/nyregion/21grid.html

Jaffe, Eric, Nov 21, 2011, A Visual History of Manhattan’s Grid, Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2011-11-21/a-visual-history-of-manhattan-s-grid

Panero, James,The Greatness of the Grid, Mar 23, 2012, City Journal, https://www.city-journal.org/article/the-greatness-of-the-grid

Kimmelman, Michael, The Grid at 200: Lines That Shaped Manhattan, Jan 2 2012, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/03/arts/design/manhattan-street-grid-at-museum-of-city-of-new-york.html

Barr, Jason and Gerard Koeppel, The Manhattan Street Grid Plan: Misconceptions And Corrections, Dec 4 2016, The Gothan Center for New York City History, https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/gridplanmain

Holloway, Marguerite, How Manhattan Got Its Street Grid, Feb 15, 2013, Scientific American, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-manhattan-got-its-street-grid/

Wright, Artis Q., Designing the City of New York: The Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, New York Public Library Blog, Jul 3 2010, https://www.nypl.org/blog/2010/07/30/designing-city-new-york-commissioners-plan-1811

[28] Barbara McMartin and W. Alec Reid, The Glove Cities, Caroga, NY: Lake View Press, 1999 Page 74

[29] Barbara McMartin and W. Alec Reid, The Glove Cities, Caroga, NY: Lake View Press, 1999 Page 8

[30] Barbara McMartin and W. Alec Reid, The Glove Cities, Caroga, NY: Lake View Press, 1999 Page 2

[31] Hunt, Arthur, Twelfth Census of the United States, Census Bulletin No. 175, Washington D.C. May 24, 1902, Manufactures: Gloves and Mittens – Leather, Page 10 https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1900/bulletins/manufacturing/175-manufactures-gloves-mittens-leather.pdf

[32] Grand Duchy of Baden, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 25 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Duchy_of_Baden

Lambert, Audrey M. “Farm Consolidation in Western Europe.” Geography, vol. 48, no. 1, 1963, pp. 31–48. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40565503