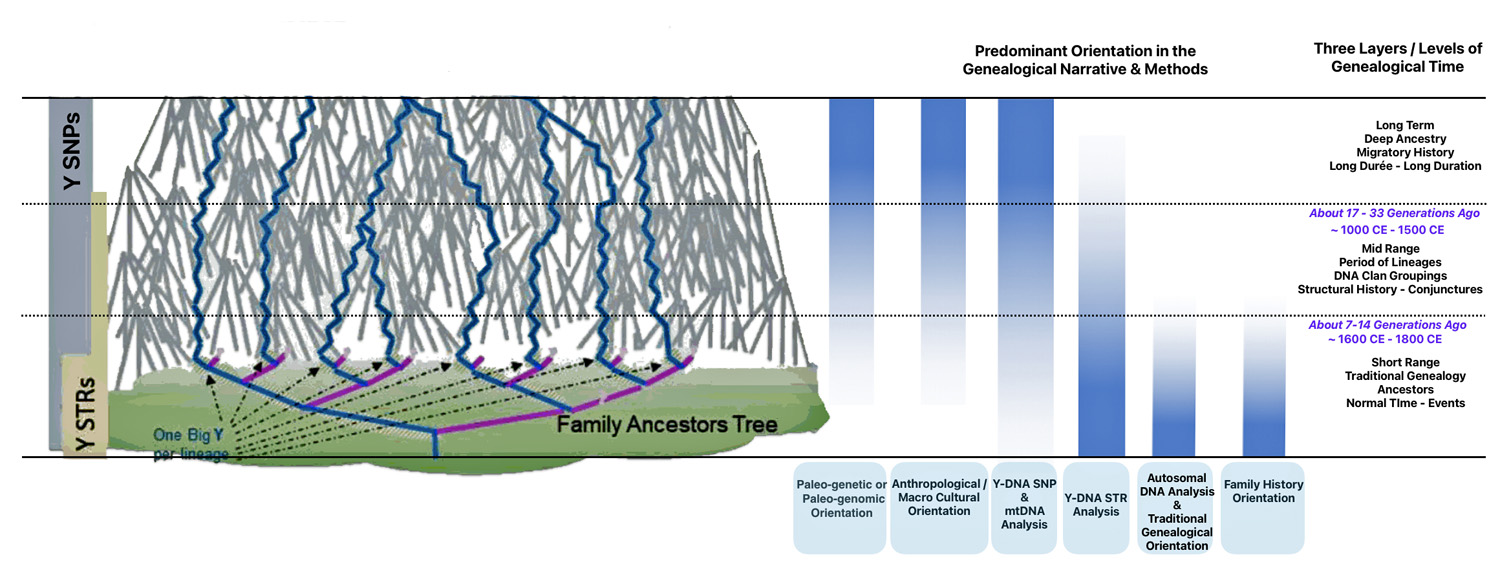

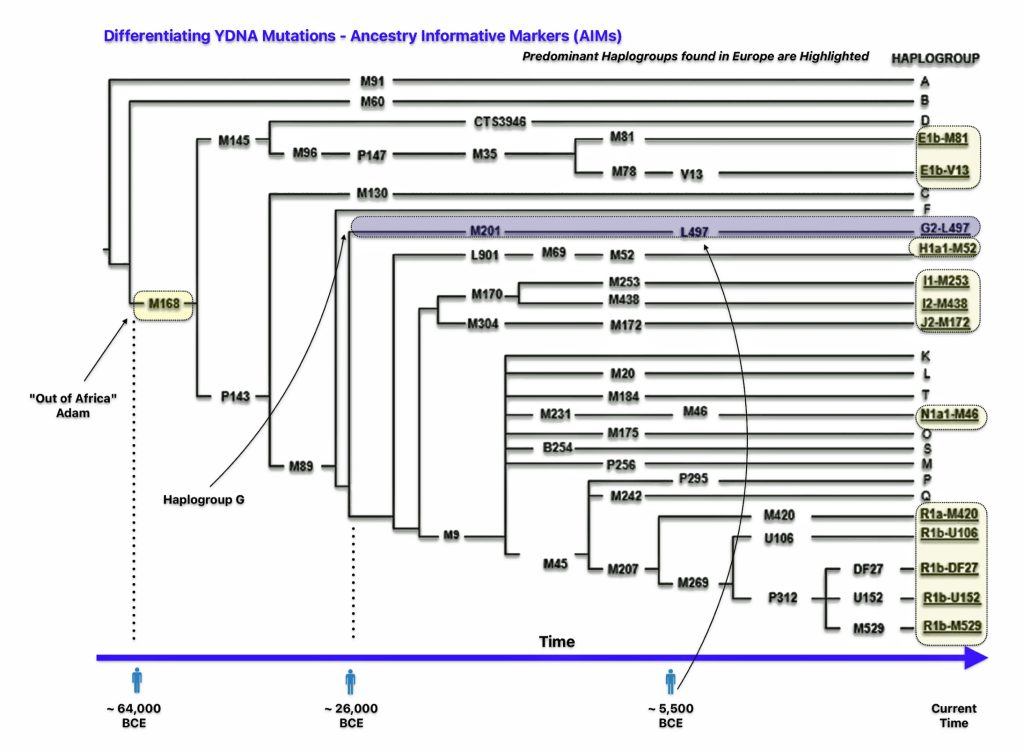

This story focuses on looking at the phylogenetic tree of the Griff(is)(es)ith) patrilineal line of descent and the migratory route of the Griffis family Y-DNA in the long term genealogical time layer.

Y-DNA phylogenetic trees provide an effective, graphic portrayal of human genetic history and genealogy. They offer insights into paternal lineage, population migrations and a complimentary image to discuss anthropological research and genealogical connections. Phylogenetic trees are also known as an evolutionary tree, cladogram, or tree of life. [1]

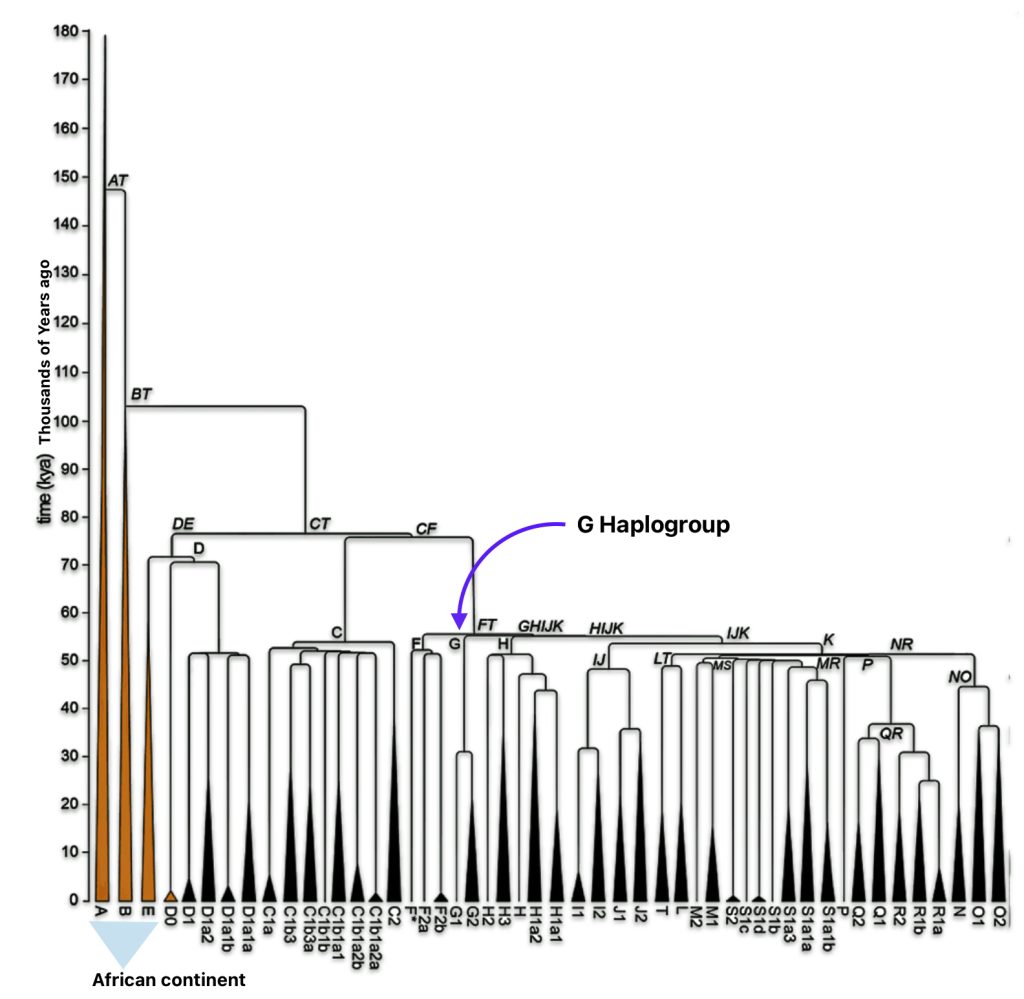

The use of phylogenetic trees provide a skeletal outline of the specific evolutionary path of the patrilineal genetic line of the Griff(is)(es)(ith) family. The family genetic patrilineal line is part of Haplogroup G. The G haplogrup is a Y-chromosomal lineage originating in the eastern Anatolian-Armenian-western Iranian region. From aproximately 10,000 BCE to 3,000 BCE it was a predominant YDNA haplogrup in Europe. Thereafter, it lost its predomance and became a minorty among YDNA haplogroups in Europe.

Looking Backward in Time: The Present European Y-DNA Phylogenetic Tree

In 2013 FamilyTreeDNA (FTDNA) released the advanced Big Y test and since then the company analyzed 32,000 Y chromosomes in ultra-high resolution. This has allowed the ability to identify hundreds of thousands of unique Y chromosome mutations. In 2019, the company created the Y-700 YDNA test and detected over 500,000 unique mutations in 32,000 Big Y testers. In May 2019, the Y-DNA haplotree passed 20,000 branches. The branches are defined by over 150,000 unique mutations. [2]

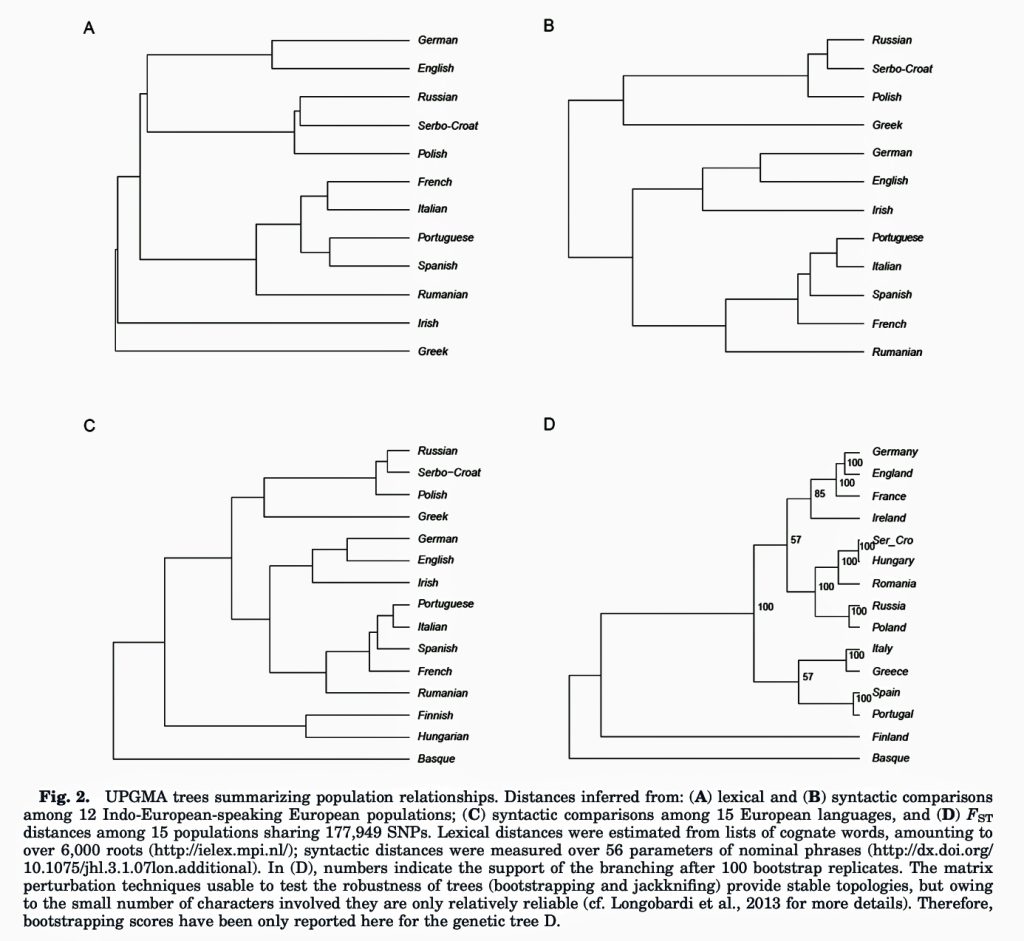

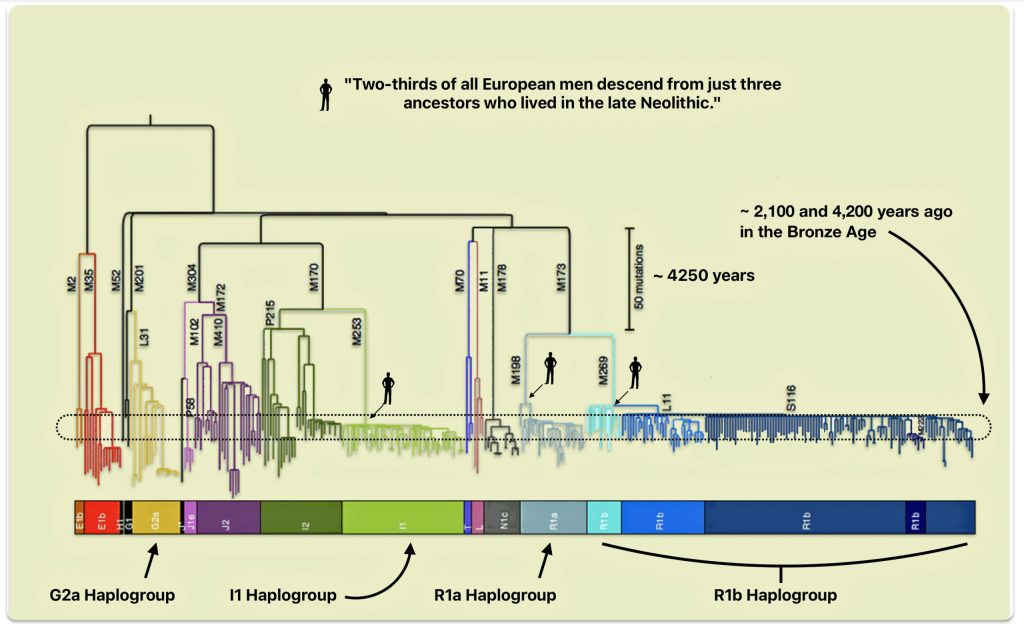

Illustration one below represents a circular phylogenetic Y-DNA haplogroup tree based on the testing results of FTDNA in 2019. It is a visual representation that shows evolutionary relationships between paternal lineages. The tree structure displays branches that represent genetic mutations and divergence over time. Time flows from the center outward, with older lineages near the center and younger ones at the periphery. Each branching point represents a most recent common ancestor – a genetic mutation (SNP) that created a new haplogroup. [3] Related haplogroups are grouped together in adjacent branches, showing their evolutionary relationship. Branch length indicates genetic distance or time between the genetic mutations.

Illustration One: FamilyTreeDNA Circular Phyogenetic YDNA Tree of Haplogroups Based on the Y-700 Test Results

A review of the ‘pie chart’ or circular phylogenetic tree in illustration one reveals the predominance of the R haplogroup. Haplogroup R represents about half the men who have completed FamilyTreeDNA Y-700 DNA tests and has several major subbranches. Haplogroups I and J present roughly one third of the men tested. The Griff(is)(es)(ith) family lineage is part of haplogroup G, which is an older haplogroup with fewer branches and fewer test results.

While this circular phylogenetic tree represents the 2019 population of FTDNA Y-700 DNA tests kits, it has a vague proportional resemblance of the YDNA composition of Europe.

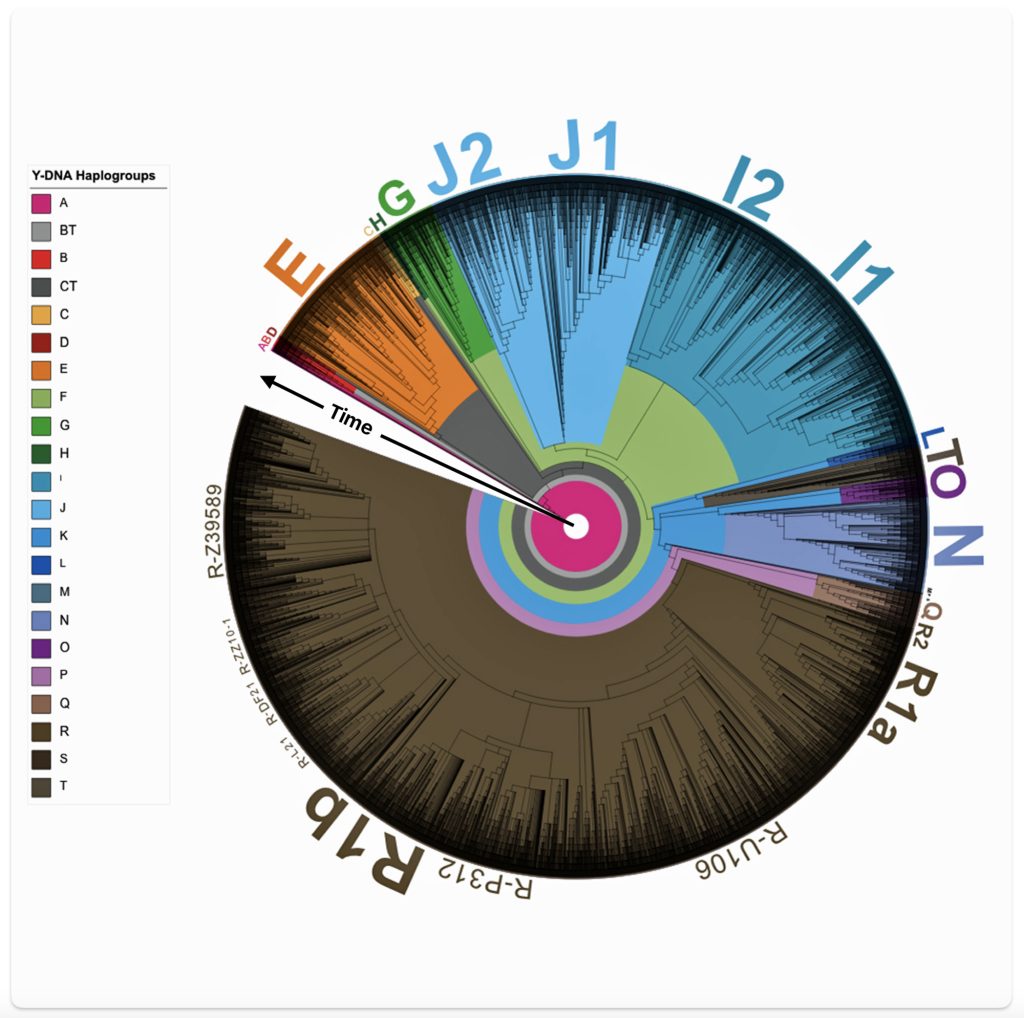

“We know that two-thirds of all European men descend from just three ancestors who lived in the late Neolithic.” [4]

This quote is an attention grabber. It has been quoted in a number of genealogical sources. In most regions of Europe, the Neolithic period generally ended around 3000 BCE, marking the transition to the Bronze Age. The exact time frame can vary depending on the geographical location with some areas seeing the Neolithic last until around 2000 BC. [5]

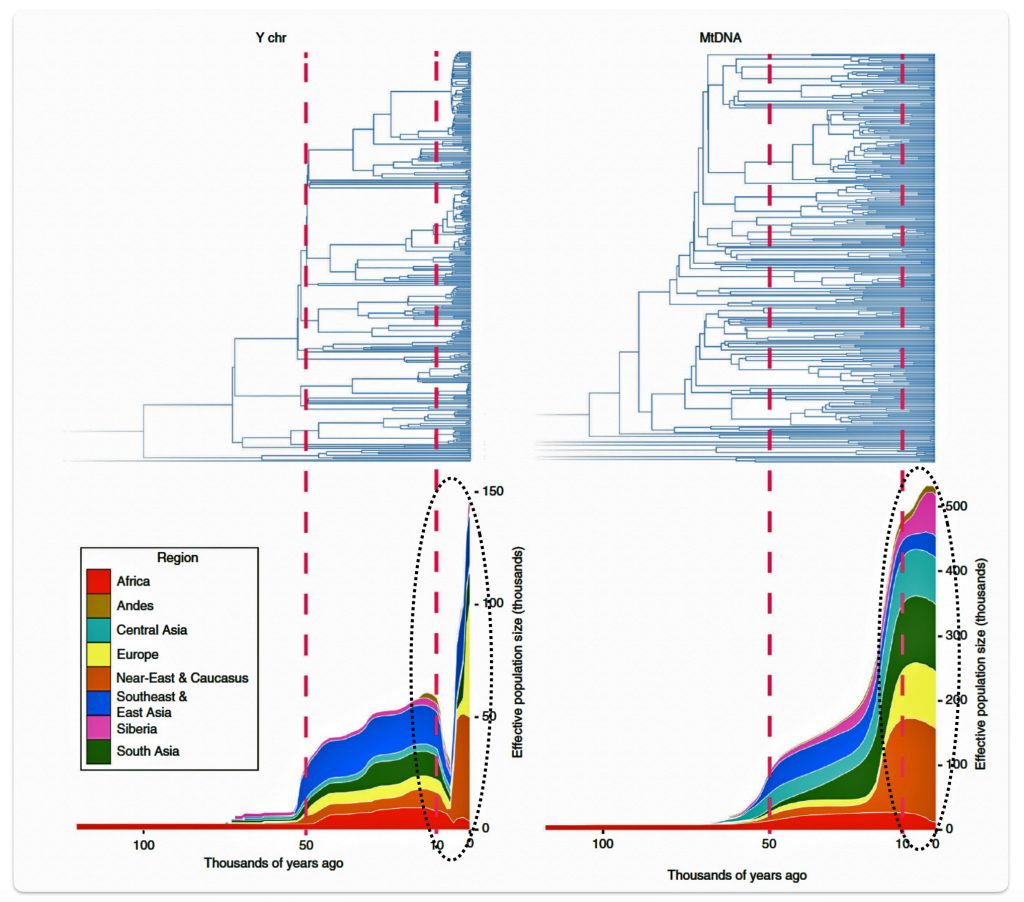

This remarkable genetic pattern emerged during a massive population explosion that occurred across Europe during the Bronze Age, spanning from the Balkans to the British Isles. The population expansion occurred between 2,000 and 4,000 years ago, particularly affecting males across a continuous region from Greece to Scandinavia. These dominant males, likely associated with Bronze Age cultures, established lineages that became prevalent throughout European populations. [6]

This YDNA genetic legacy differs from patterns seen in mitochondrial DNA which is passed down through mothers. Research of mtDNA genetic patterns shows much older population growth patterns, suggesting this was a male-specific phenomenon tied to Bronze Age social structures. [7]

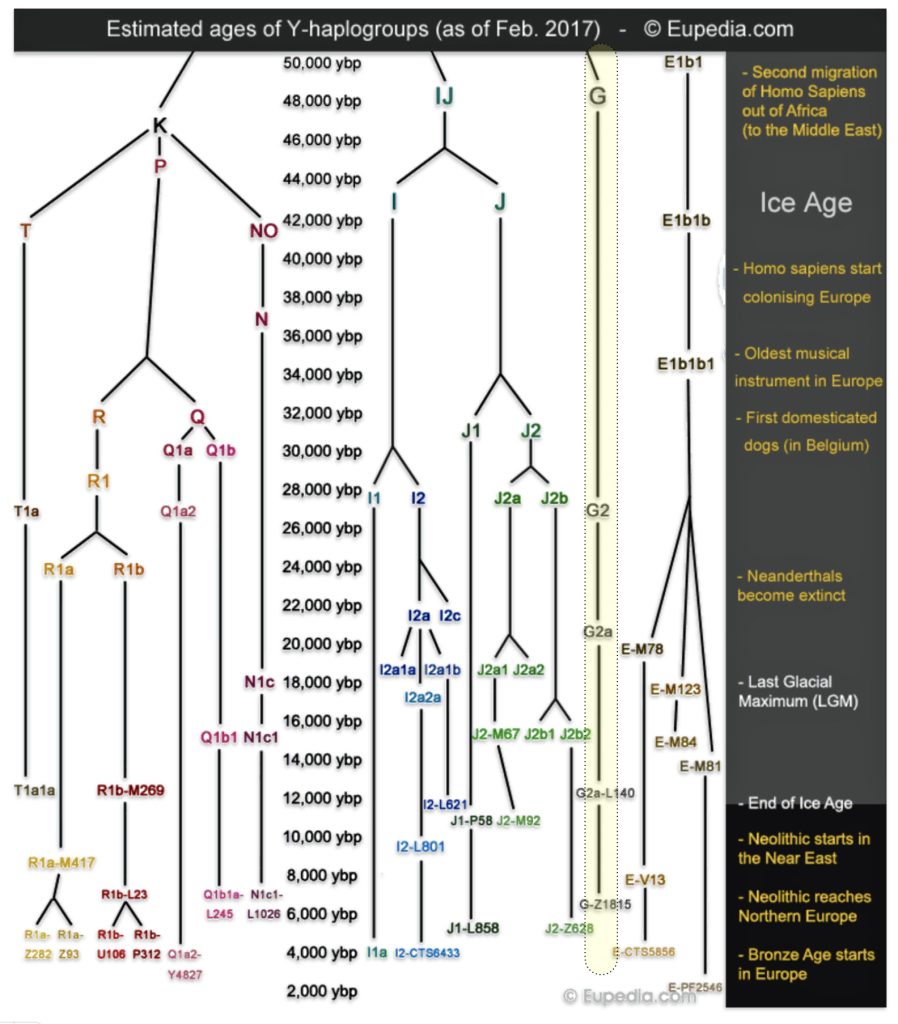

Going back to the original quote regarding those three ancestors, the statement requires some clarification. Genetic studies show that approximately sixty-four percent of European men can trace their Y-chromosome lineages back to just three male ancestors who lived between 3,500 and 7,300 years ago. These haplogroup lineages are identified as I1, R1a, and R1b and are identified in illustration five by three ‘standing male’ symbols. [8]

By counting the number of mutations that have accumulated within each branch over the generations, it is estimated that these three men lived at different times between 3,500 and 7,300 years ago. The lineages of each seem to have exploded in the centuries following their lifetimes to dominate Europe. The Bronze age is identified by a dotted elliptical circle in the illustration. Within that enclircled time era, the idenification of a proliferaion of lineages is evident in the I and R haplogroups.

Illustration Two: Phylogeny and Geographical Distribution of European Lineages

The spread of these Y-chromosome patterns depicted in illustration two may be linked to the influence of the Yamnaya people. They were nomadic, pastoral herders from the steppes of modern-day Ukraine and Russia. They entered Europe around 4,500 years ago. They brought with them technological innovations including horses, the use of wheel driven transportation, and distinctive burial practices. Dominant males linked with these cultures could be responsible for the Y chromosome patterns we see today. [9]

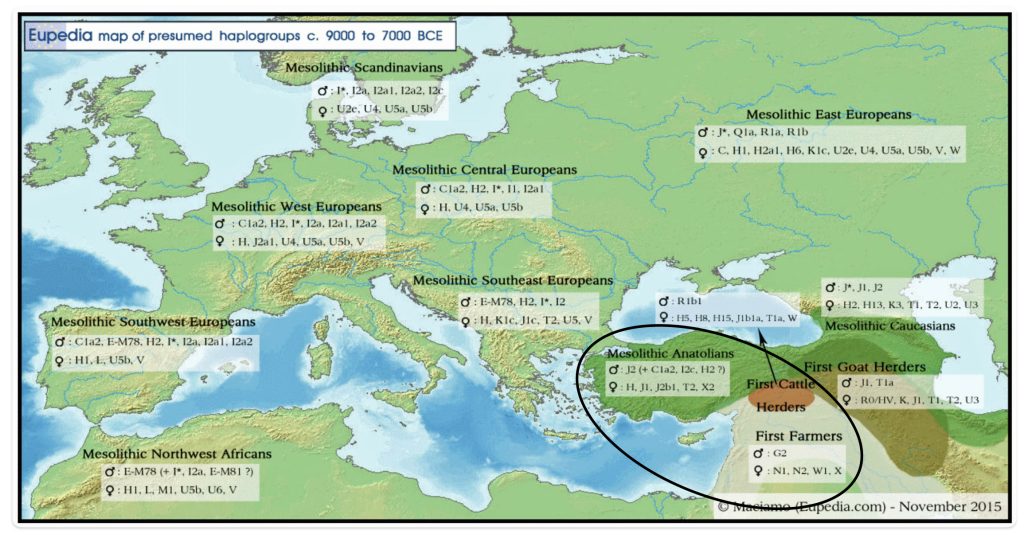

The complete genetic heritage of modern Europeans is complex, involving at least three distinct ancestral populations and represented by a number of YDNA and mtDNA Haplogroups: West European Hunter-Gatherers, Ancient North Eurasian and Early European Farmers. This genetic mixing occurred within the last 7,000 years, creating the modern European gene pool. [10]

Overview of the Migratory Path

As a background to discussing the patrilineal line of descent, the video below is an animated version of the estimated migratory path of the genetic Y-DNA descendants of the Griff(is)(es)(ith) family line. It is a singular path based on my Y-700 YDNA test results. It starts with the root Y-DNA source in Africa, often referred to as “Y-chromosomal Adam,” the most recent common ancestor of all living males. [11]

Animated Video of Estimated Migratory YDNA Path for the Griff(is)(es)(ith) Paternal Line

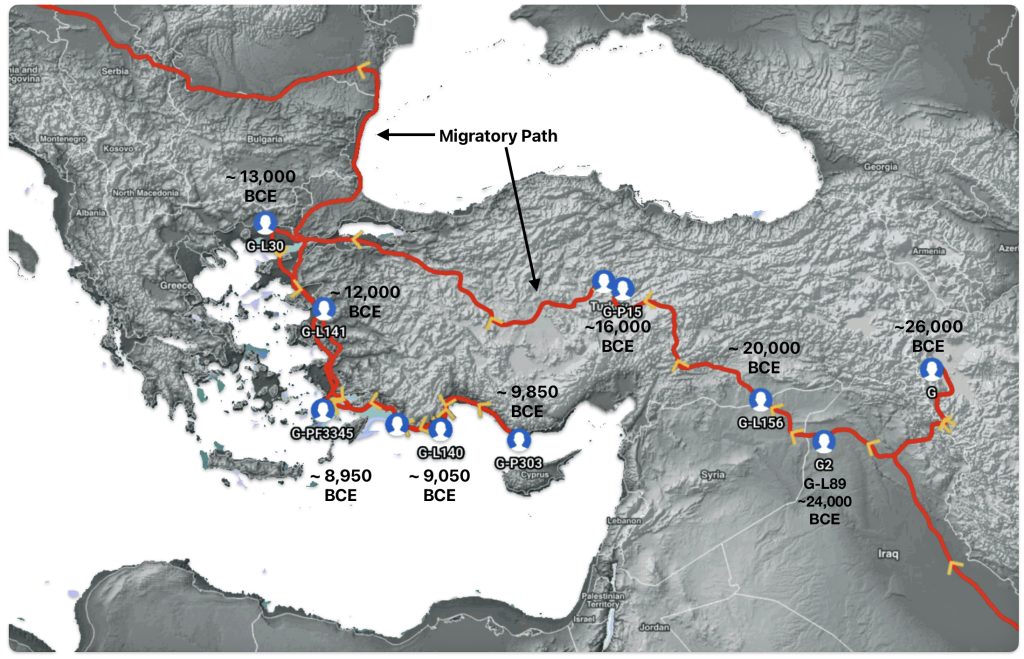

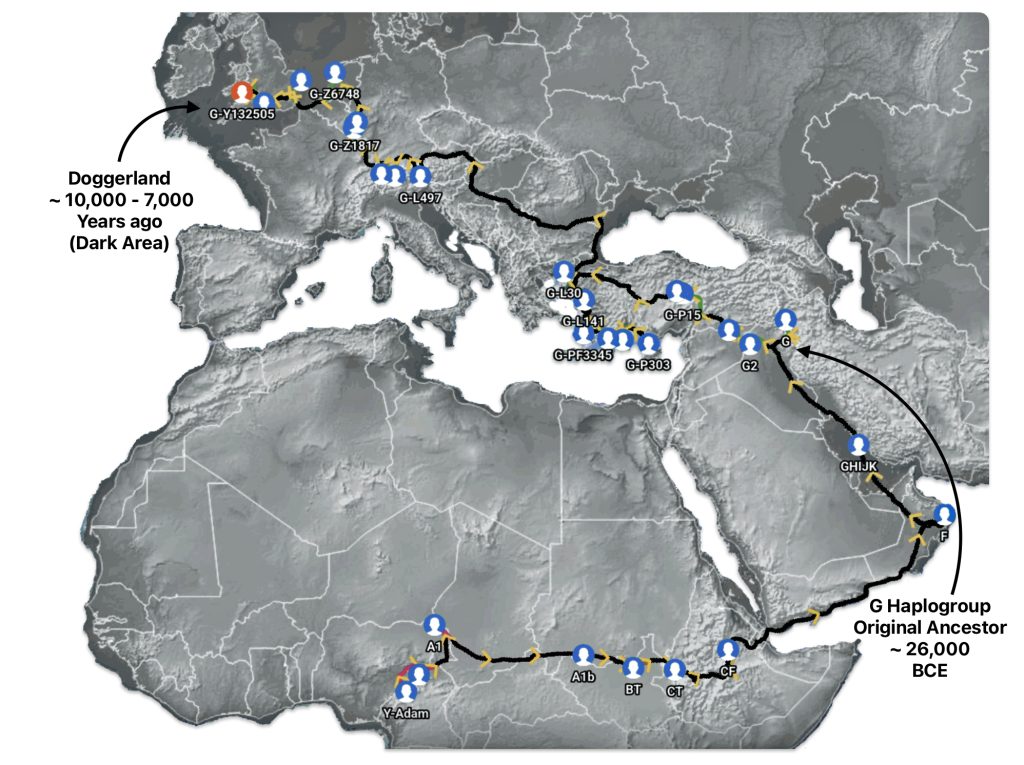

The animated video provides an inuitive rendition of over 200,000 years of the successive mutations in Y-DNA for the family paternal line. It provides a graphic portrayal of the general path of migration that ultimately led to the English Isle. The animation depicts lands that are now submerged (e.g. Doggerland [12] ) and the extent of the ice age in context of the migration. Illustration one below is a graphic portrayal the migratory path of the G haplogroup starting around 26,000 BCE.

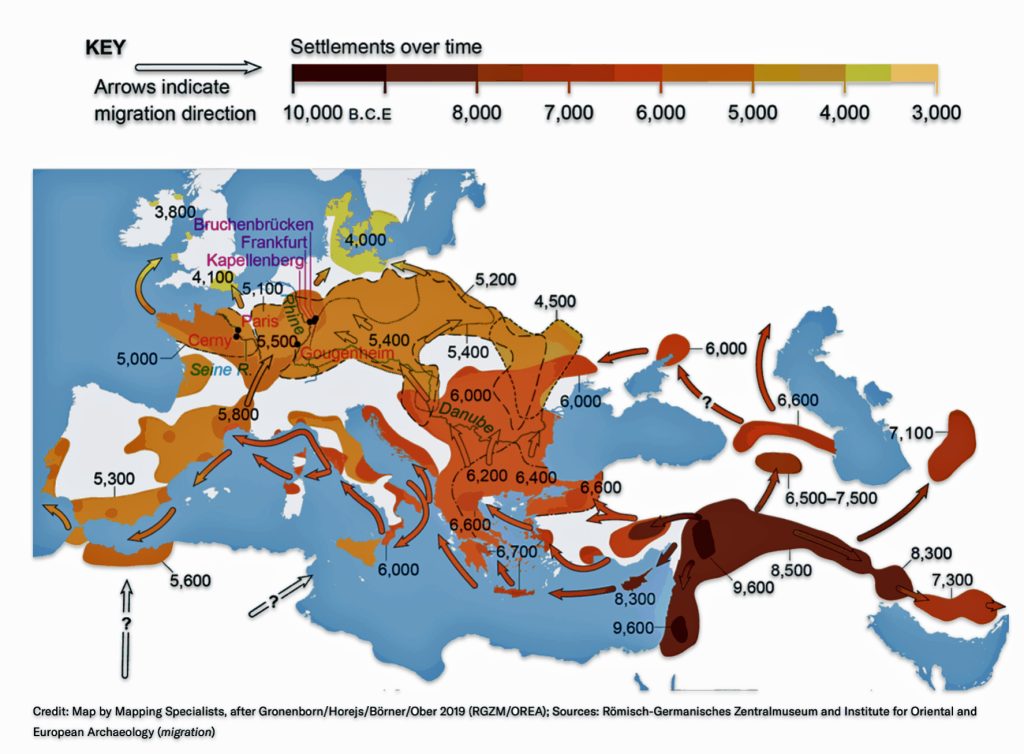

Illustration One: Snapshot of Migratory Path of G Haplogroup and Griff(is)(es)(ith) Family Descendants

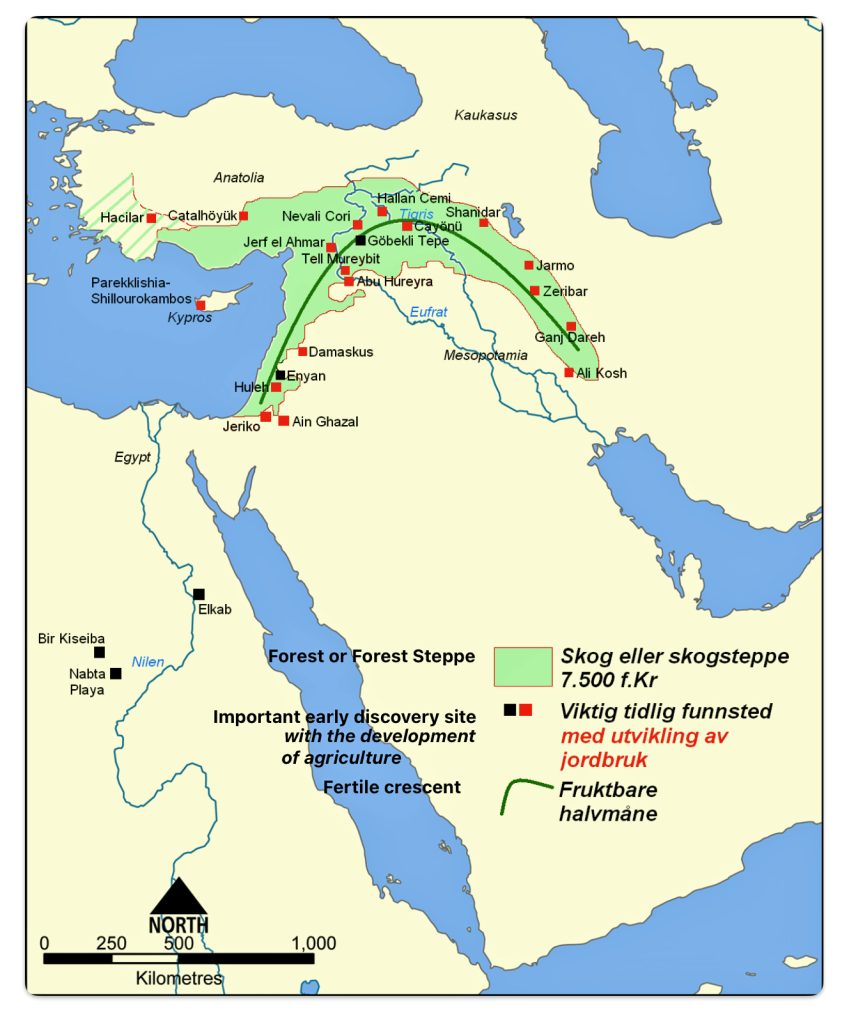

Haplogroup G-M201 likely originated in a region spanning eastern Anatolia, Armenia, and western Iran around 26,000 BCE.. The earliest G-M201 carriers were linked to pre-Neolithic populations, but its diversification in other subclades accelerated during the Neolithic transition (around 10,000 BCE). The G-P303 sub-clade, which accounts for the majority of European G lineages, diverged during this period, with sub-clades like G-L497 (Europe-specific) and G-U1 (Near Eastern/Caucasus) reflecting later regional adaptations. [13]. Haplogroups G2a and J-M172, which originated in Anatolia, spread westward alongside early farming communities. [14]

Haplogroup G2a spread across Europe primarily through the Neolithic agricultural expansion from the Near East (Anatolia) into Europe, roughly between 9,000 and 5,000 years ago. This migration involved early farming communities moving westward, introducing agriculture, domesticated animals, and pottery cultures into regions previously inhabited by hunter-gatherers. The Neolithic Revolution began in the Levant and Anatolia, where domestication of crops like wheat, barley, and legumes, alongside animals such as sheep and goats, laid the foundation for sedentary lifestyles. [15]

The Two Routes of G Haplogroup Migration

As depicted in illustation two below, the spread of the G haplogroup occurred via two main routes: the Mediterranean Coastal Route (“Maritime Route”) and the Central European Inland Route (“Danubian Route”).

Illustration Two: The Two Main Routes of Migration for Neolithic Farmers

The Mediterranean route took early Neolithic farmers carrying haplogroup G2a along the Mediterranean coastline, establishing settlements in Greece, Italy, southern France, Spain, and Portugal. This migration is associated with the Cardium Pottery culture, characterized by pottery decorated with shell impressions. Ancient DNA evidence from Neolithic sites in southern France (such as the Treilles group around 3000 BCE) confirms a high prevalence of G2a ( individuals who descended from populations originating in Anatolia or the Aegean region. [16]

Another major route was inland via the Danube River valley into Central Europe. This is the route that the Griff(is)(es)(ith Paternal genetic line of descent took in migranting westward in Europe. This dispersal is associated with the Linear Pottery culture (LBK) (approximately 5500–4500 BCE), which introduced agriculture to Central Europe. Ancient DNA analyses of LBK archaeological sites in Germany and Hungary show a high frequency of haplogroup G2a among early farmers. [17]

By 7000 BCE, these practices spread northwestward into southeastern Europe, marking the start of the Continental Route. The Starčevo culture (6000–5400 BCE) in present-day Serbia and Hungary served as the initial bridge between Anatolian farmers and the Danube Basin, establishing agro-pastoral communities that later influenced the LBK. [18]

The G haplogroup associated with this ‘Danbian route’ in central Europe shows a frequency peak in the Danube basin associated with the G-L497 haplogroup, aligning with the Linear Pottery Culture (LBK) expansion. [19] The European origin of G-L497 makes it particularly valuable for tracing secondary migration patterns, such as the Griff(is)(es)(ith) paternal line, and population movements within Europe following the initial Neolithic expansion.

G Haplogroup Decline, Absorption and Refuge

Despite its widespread initial distribution, along with the J Haplogroup, during Europe’s Neolithic period, haplogroup G2a significantly declined in frequency after 3000 BCE due to migrations of pastoralist populations from the Eurasian steppe (such as the Yamnaya culture), who carried different Y-DNA haplogroups like R1b and R1a. These migrations largely replaced or assimilated earlier farming populations. [20]

The R haplogroup pastoralists expanded through the Pontic-Caspian steppe corridor, moving westward into Europe from their eastern origins. These steppe populations were genetically distinct from both European hunter-gatherers and early farmers. The expansion of these pastoralist groups led to massive population turnover in Europe, with substantial genetic input from steppe populations arriving after 3000 BCE. [21]

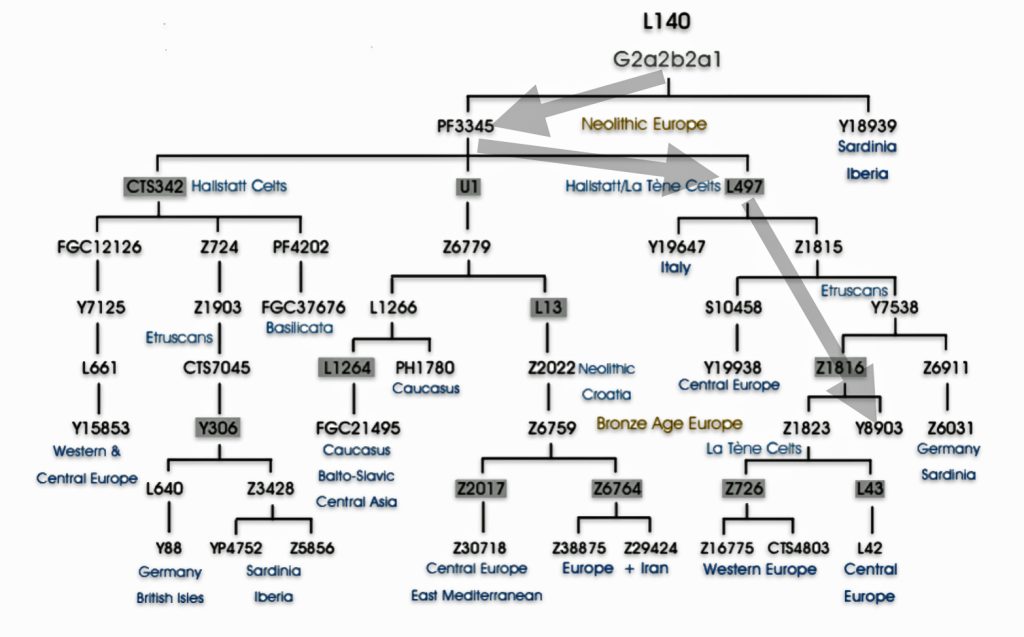

While many G2a lineages were largely replaced by Indo-European expansions, some G2a-L140 subclades appear to have been assimilated into Proto-Indo-European societies associated with the R haplogroups. These lineages, including certain L497-derived groups, joined R1b and R1a tribes in their subsequent migrations. This suggests a complex interaction between the descendants of Neolithic farmers and the expanding Indo-European populations rather than simple replacement. [22]

These “Indo-Europeanized G2a lineages”, such as the Griff(is)(es)(ith) line, belonged to deep clades of G2a-L140, including subclades like L13 and Z1816. While the original Neolithic G2a populations were dramatically reduced, some were incorporated into the expanding Indo-European groups, allowing certain G-L497 lineages to spread alongside R1a and R1b haplogroups during later migrations.

Today, haplogroup G2a descendants remain present at lower frequencies throughout Europe but have higher concentrations in isolated regions like Sardinia and parts of the Caucasus, reflecting remnants of these ancient Neolithic expansions. The Griffis)(es)(ith) paternal line is part of this minorty haplogroup in modern times.

Haplogroups and Phylogenetic Trees

Y-DNA haplogroups serve as markers of historical population movements. A haplogroup is a group of people who share a common ancestor and similar genetic markers. The Y chromosome’s lack of recombination allows SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) to accumulate linearly over generations, making them valuable markers for tracing paternal lineages.

Human phylogenetics is the study of evolutionary relationships between ancient and present humans based on their genetic material, specifically through DNA and RNA sequencing. Phylogenetic relationships are typically visualized through phylogenetic trees, which use branches and nodes to show the chronology of genetic mutations. These trees can be either rooted, showing a hypothetical common ancestor, or unrooted, making no assumptions about ancestral lines. [23]

“Classifying the accumulated SNPs generation by generation make it possible to retrace the genealogical tree of humanity with great accuracy, to detect patterns in the distribution of shared historical lineages and to retrace historical migrations of male lineages.” [24]

Y-DNA phylogenetic trees are visual representations of the evolutionary relationships between different paternal lineages in human populations based on mutations in the Y chromosome. These trees illustrate the hierarchical structure of Y-DNA haplogroups, which are groups of men sharing specific mutations on their Y chromosome inherited from common paternal ancestors.

“Paleolithic lineages that underwent serious population bottlenecks for thousands of years sometimes have a series of over one hundred defining SNPs or SNP variants (e.g. haplogroups G and I1 each have over 300 defining SNPs). Generally speaking the number of accumulated SNPs between a haplogroup and its direct subclade correlates roughly to the number of generations elapsed.” [25]

The average number of years between Y-chromosomal SNP mutations is a parameter for estimating timelines in genetic genealogy, population genetics, and anthropological studies. Based on current research and commercial testing methodologies, this interval typically ranges from 83 to 144 years per SNP, depending on the sequencing technology, genomic regions analyzed, and mutation rate calculations. [26]

Branch lengths in a YDNA phylogenetic tree can be interpreted as measures of time, but there is significant scientific debate about the exact temporal relationships. [27] In phylogenetic studies (the study of evolutionary relationships between human remains or tests based on genetic material), branch lengths are considered proportional to time when evolution rates are uniform across lineages. [28] For Y-chromosomes, this has allowed researchers to create phylogenies where branch lengths can be used to estimate the timing of population divergences. [29]

Y-DNA Phylogenetic Trees

The phylogenetic tree starts with a root, often referred to as “Y-chromosomal Adam” [30], the most recent common ancestor of all living males. Haplogroups are labeled with letters A through T, with further subclades denoted by numbers and lowercase letters. The Y Chromosome Consortium (YCC) developed a naming system for major haplogroups and their subclades. [31]

Illustration Three: Major Clades of Y-DNA Phylogenetic Tree

Phylogenetic trees contextualize these haplogroups within historical and geographical frameworks, revealing how subclades diverged during key migratory periods. The combination of Y-DNA trees with archaeological findings has clarified debates over human migratory patterns. Each branch represents a distinct lineage defined by specific single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The tree’s depth indicates the time since divergence with deeper branches representing older lineages. New mutations are continually discovered, leading to regular updates and the increased resolution of the tree. [32]

Illustration Four: Chronological Development of Main Western Eurasian Y-DNA Haplogroup Subclades from the Late Paleolithic to the Iron Age

Y-DNA phylogenetic trees provide a number of advantages for genealogical studies, forensic applications and population genetics. They can resolve paternal lineages and surname correlations, validate and extend surname clusters, enhance foresensc and kinship analysis, advance methodological innovations, and reconstruct ancient migrations and population histories. [33]

These trees can integrate short tandem repeats (STRs) and SNPs to resolve relationships across both recent, mid range and deep historical time scales. By dating branch points using mutation rates, researchers estimate the timing of population splits. Classiying SNPs and STRs into a genealogical order is known as phylogenentics. [34]

Y-DNA phylogenetic trees excel in connecting individuals who share recent common ancestors through STR markers, which mutate relatively quickly, and deeper ancestral links through slower-mutating SNPs. For example, STR-based clusters (e.g., 37-marker or 111-marker STR haplotypes) can identify related individuals within a genealogical timeframe in the last 500 years, while SNP-defined haplogroups (for example, the G-L497 haplogroup) trace lineage splits dating to the Neolithic or Bronze Age. This dual resolution allows surname projects to corroborate paper trails with genetic evidence, particularly for patrilineal lines where records are sparse in the short term and mid range genealogical time layers. [35]

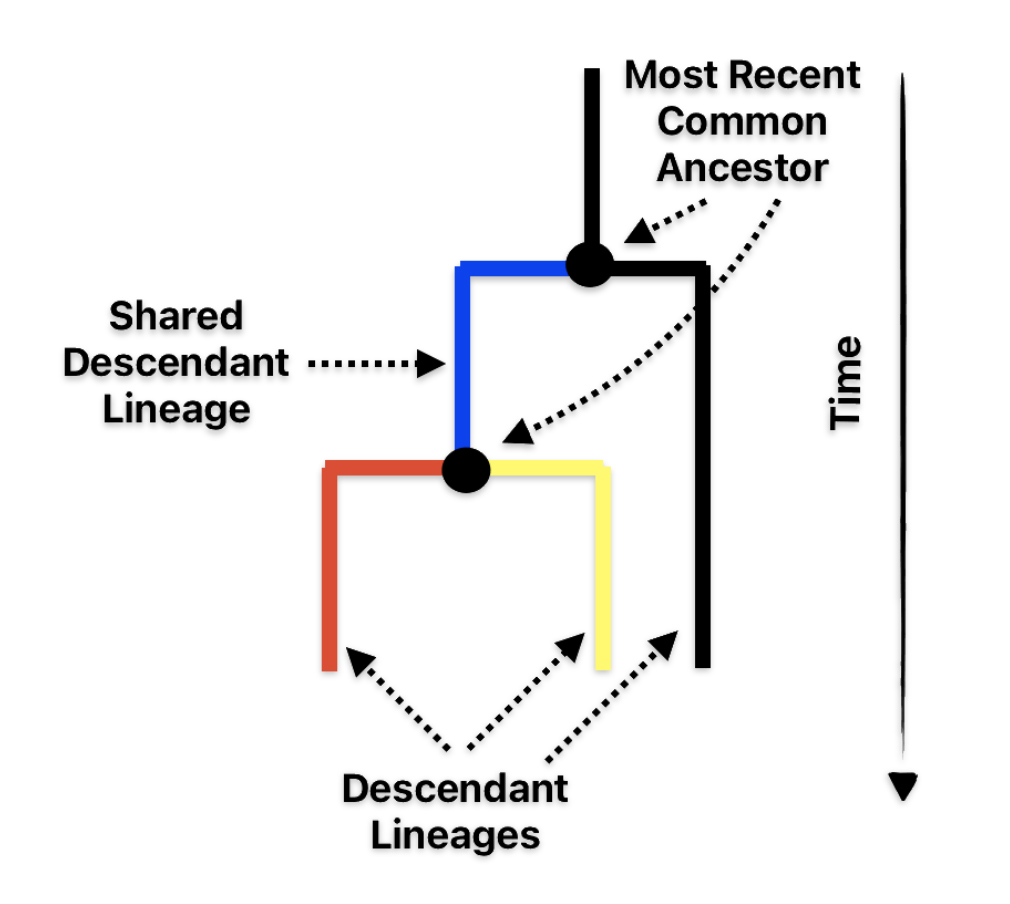

The Most Recent Common Ancestor and Phylogenetic Trees

The ‘nodes’ in phylogenetic trees represent estimated birth dates of the most recent common ancestors for subsequent lineages. The ages of the most recent common ancestors (tMRCA) in Y-DNA phylogenetic trees are calculated primarily through statistical methods that incorporate genetic data and historical information.

Rather than focus on the order of the branch tips on a phylogenetc tree (i.e., which lineage goes to the right and which goes to the left), this ordering is not meaningful at all. Instead, the key to understanding genetic relationships in phylogenetic trees is common ancestry. Common ancestry refers to the fact that distinct descendent lineages have the same ancestral lineage in common with one another, as shown in illustration five.

Determining the dates of tMRCA for Y-DNA haplogroups involves several steps and assumptions, which also come with certain limitations. While SNP-based calculations provide a powerful tool for estimating tMRCA dates, they are subject to limitations related to mutation rate variability, data quality, and the assumptions underlying the models used to estimated their respective dates.

Illustration Five: the Most Recent Common Ancestor

Variability of tMRCA Estimates

Current calculations for TMRCA in Y-DNA phylogenetic trees rely on counting genetic mutations (SNPs and STRs), using probabilistic models that integrate multiple data types, and adjusting results based on historical context and demographic factors. [36]

As with any historical calculations, there are a number of inherent limitations associated with the estimation process. The mutation rate is not perfectly uniform and can vary between different parts of the Y chromosome. This variability can lead to inaccuracies in MRCA date estimates. [37] Random mutations can skew results, especially when comparing individual Big Y results. Anomalies in variant counts can lead to discrepancies in estimated dates. [38]

The calculations rely on assumptions about mutation rates and the models used. Different models or assumptions can yield different estimates, and there is ongoing debate about the most accurate methods. [39] Historical events like bottlenecks or gene flow can affect the genetic diversity of Y-DNA haplogroups, potentially altering the apparent MRCA date. [40]

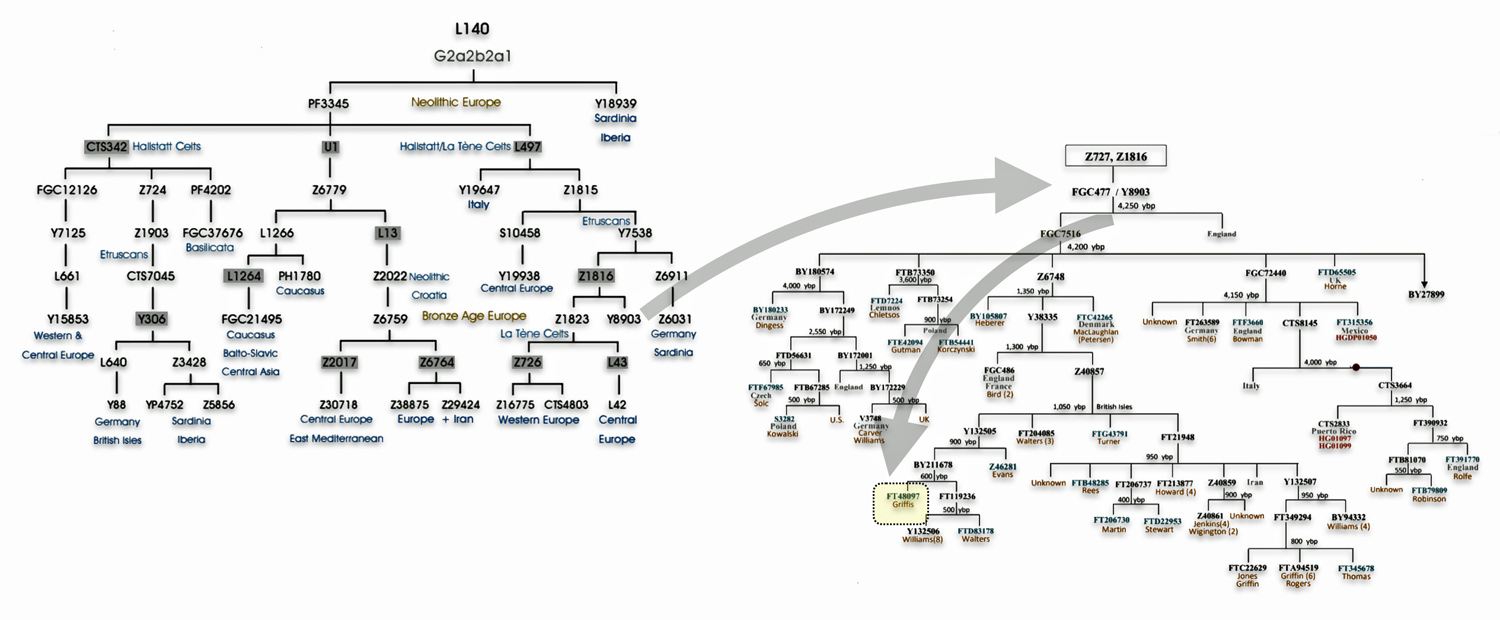

An example of the variability associated with establishing estimated dates for MRCAs is provided below. Illustration six depicts an high level phylogenetic tree that covers part of my Y-DNA ancestral genetic path. Some of my intermediate MRCAs are not shown in the tree. The tree starts with haplogroup G-L140. The shaded arrow in the illustration depicts the path of my YDNA genetic mutations from haplogroup G-L140 to haplogrop G-Y8903.

Illustration Six: A Philogenetic Tree of haplgroup G2a-L140

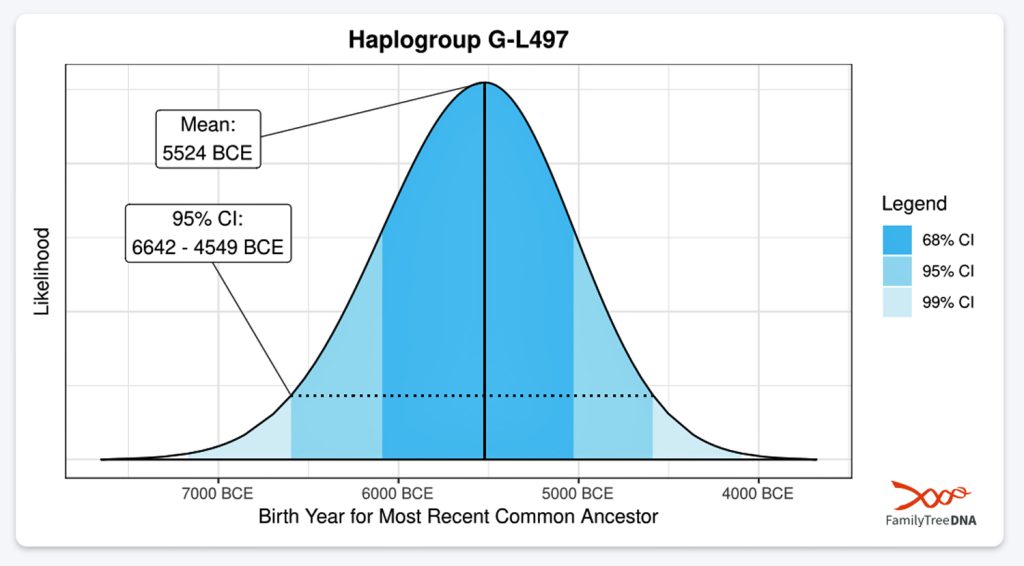

Based on the genetic path of haplogroup group mutations shown in the phylogenetic tree, I have chosen four MRCAs shown in table one. The table provides an estimated birth date of each of the MRCAs associated with the unique Y-DNA mutations. Based on the calucations used by FamilyTreeDNA, the table also provides statistical confidence ranges or intervals of the 99, 95 and 68 percent likelihood of the birth dates to fall within a given time range.

Table One: Selected Most Recent Common Ancestors and Estimated Births

| MRCA Estimated Birth (Mean) | Estimated Birth Date | 99 % Confidence Interval (CI) of when MRCA was born (Calendar Date) | 95 % CI Calendar Date Range | 65 % CI Calendar Date Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L140 | 4,587 BCE | 3615 – 1650 BCE | 3256 – 1958 BCE | 2913 – 2255 BCE |

| L497 | 7,549 BCE | 7220 – 4051 BCE | 6642 – 4549 BCE | 6090 – 5028 BCE |

| Z1817 | 5,133 BCE | 4279 – 2094 BCE | 3880 – 2437 BCE | 3499 – 2766 BCE |

| Y8903 / FGC477 | 4,279 BCE | 3374 – 1307 BCE | 2989 – 1625 BCE | 2624 – 1933 BCE |

The wide variations associated with each estimate of birth for the MRCAs underscore the wide variation of age estimates.

A graphic portrayal of the confidence intervals for estimating the birthdate for the MRCA associated with the G-L497 haplogroup is provided in illustration eight. The common ancestor associated with G-L497 is likely to have been born around the year 5524 BCE, but there is a significant range of his estimated birth. There is a 99 percent change that this person could have been born anywhere between around 7220 BCE and 4051 BCE, a variance of 3,169 years. Narrower bands of probability of when this person was born are provided for 95 percent and 68 percent chances.

Illustration Eight: Confidence Interval Ranges for Estimating Birth Date for MRCA for Haplogroup G-L497

What Do Patterns of Subclades in Phylogenetic Trees Tell Us

Different haplogroup clades or sub-branches within the Y-chromosome phylogeneic trees show distinct patterns. The G haplogroup has experienced both the expansion and contraction of subclades through its westward European migratory path.

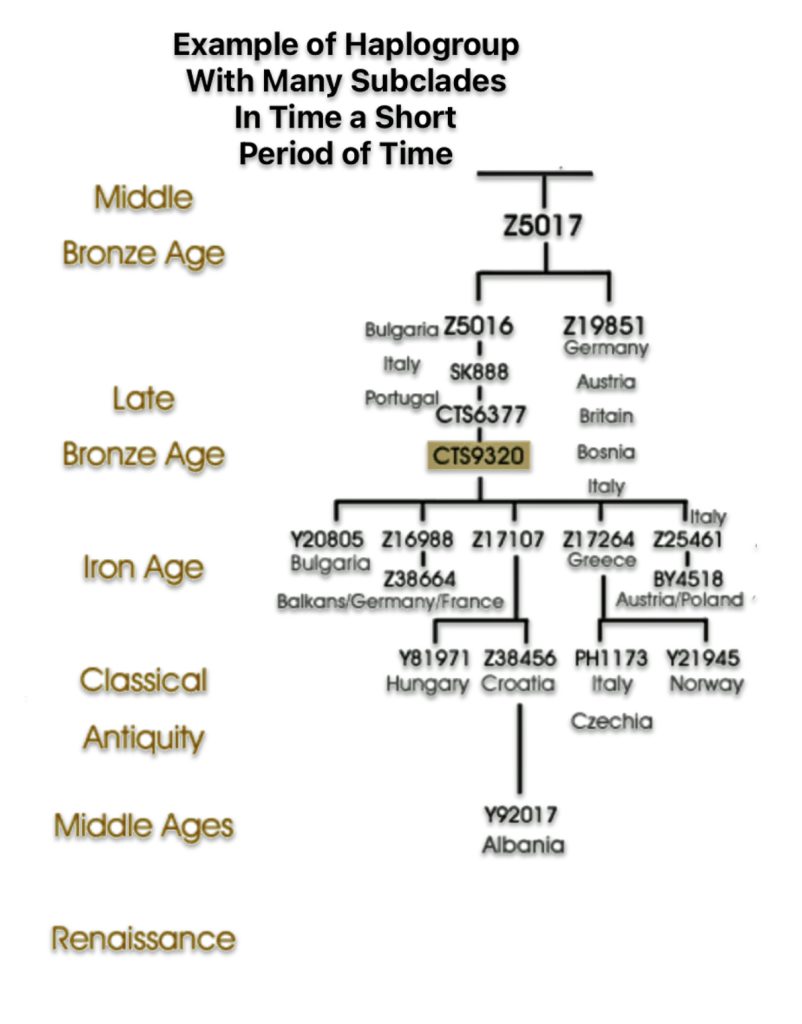

Illustration Nine

A haplotree with many subclades occurring in a short time period typically indicates a period of rapid population growth. When a Y-DNA phylogenetic tree displays numerous subclades emerging within a short timeframe, this pattern reveals important insights about our ancestral history. This phenomenon, known as a “rapid radiation” or “burst” of lineages, represents a significant demographic event that can tell us much about historical population dynamics and human migrations.

Illustration nine provides an example of this expansion in an E haplogroup branch.

These rapid diversification events often coincide with favorable historical conditions that supported population growth, such as:

- Technological innovations that improved survival rates;

- Expansion into new, resource-rich territories;

- Climate changes that created more favorable living conditions;

- Periods of relative peace and prosperity;

- Agricultural developments supporting larger populations; and

- Many rapid subclade formations correlate with important cultural transitions, such as the adoption of agriculture, metallurgy, or other technological advances that enabled population growth.

The biological mechanism behind rapid subclade formation involves multiple male lineages successfully reproducing around the same time period. Since Y-DNA mutations occur at relatively slow rates, a cluster of branches occurring closely together in evolutionary time suggests numerous male lineages were simultaneously successful in passing on their Y chromosomes. [41]

Typically, approximately every third or fourth generation, a son is born with a SNP that makes him unique and slightly different from his father”. When many such lineages survive in a short time period, it creates a characteristic ‘star-like pattern’ in the phylogenetic tree, with numerous branches emanating from a single ancestral node or MRCA.

This pattern creates an imbalance where larger ‘child’ clades or haplogroup branches receive statistically more mutations than smaller child clades. The mutations occurring early in the expansion become defining features of the larger subsequent subclades. [42]

This clustering of subclades in time can sometimes cause statistical challenges in dating the exact age of these closely-spaced subclades as there may be too few mutations separating parent clades from child clades to establish precise timing of the most recent common ancestor.

This statistical artifact of clustering subclades is evident when looking at the Griff(is)(es)(ith) family lineage in Table Two below. I have noted this by annotating the time passed between subclades in red.

Illustration Ten

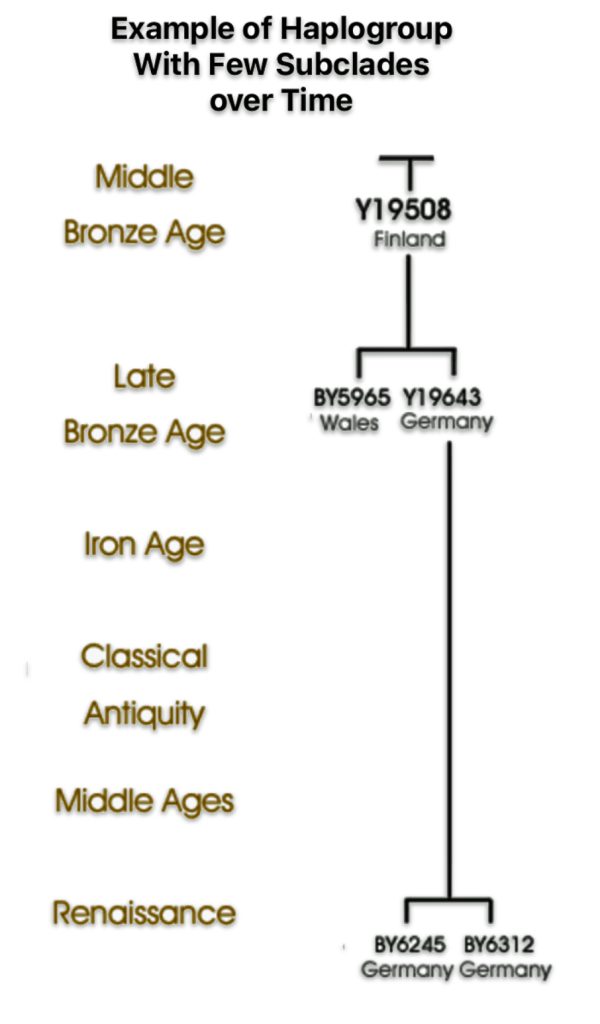

Periods of rapid subclade formation stand in stark contrast to periods of slower diversification. When a phylogenetic tree shows a long branch with many accumulated mutations before diversification occurs, this suggests a lineage survived through challenging conditions before eventually flourishing. When a Y-DNA phylogenetic tree displays few subclades over a long stretch of time, this pattern represents what geneticists call a “long branch” – a significant period where little apparent diversification occurred in the paternal lineage. This phenomenon has several important biological, demographic, and methodological implications.

A haplotree with few subclades is provided in illustration ten. Haplogroup E-Y19508 a major branch that has the same most recent common ancestor that is associated with the branch in E-Z5017 in illustration nine. However, the phylogenetic tree associated with the E-Y19508 branch is long and narrow. This is an example of an E haplogroup branch spread over a long time period. This typically indicates slower population growth and more stable demographic conditions.

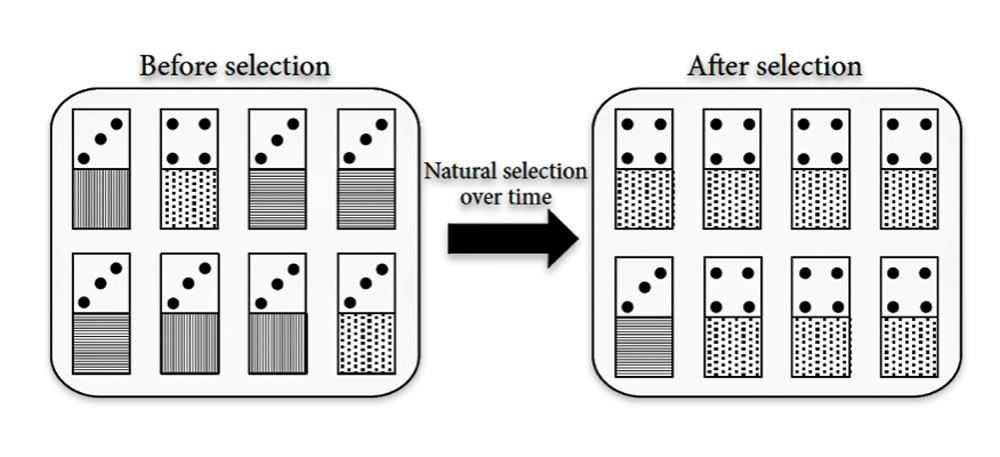

A primary explanation for long branches with minimal subclade formation is a severe reduction in male effective population size. Studies have documented a pronounced decline in male effective population sizes worldwide around 3000-5000 years ago that was not observed in female lineages. This genetic bottleneck would naturally result in the elimination of many Y-chromosome lineages, leaving fewer surviving male lines to develop subclades. [43]

Geographic isolation and natural barriers can contribute to this pattern by creating separate, isolated populations with limited genetic exchange. The slow accumulation of branches can also result from limited population growth, reduced genetic diversity, or selective pressures affecting Y-chromosome variation. [44]

Long branches with few subclades may also reflect cultural practices that influenced male reproductive success. In segmentary patrilineal systems, closely related males cluster together in descent groups. Combined with variance in reproductive success between groups, this can substantially reduce Y-chromosome diversity without requiring violence between groups. [45] In some societies, particularly after the development of agriculture and herding, a small number of males may have had disproportionate reproductive success, limiting the diversity of Y lineages. [46]

When interpreting long branches in the Y-DNA tree, several technical factors must be considered. Long branches may be dueto sampling limitations. Current phylogenetic trees are based on available samples which may not represent all historical populations. For example, the R haplogroup shows 16 times more branching than the G haplogroup despite G being almost twice as old. This could be partly due to sampling biases in European populations. [47] There is a phylogenetic artifact, long branch attraction, where distantly related lineages with significant accumulated changes (YDNA variant mutations) appear to be closely related when they are not. This can create false relationships in analyses of long branches. [48]

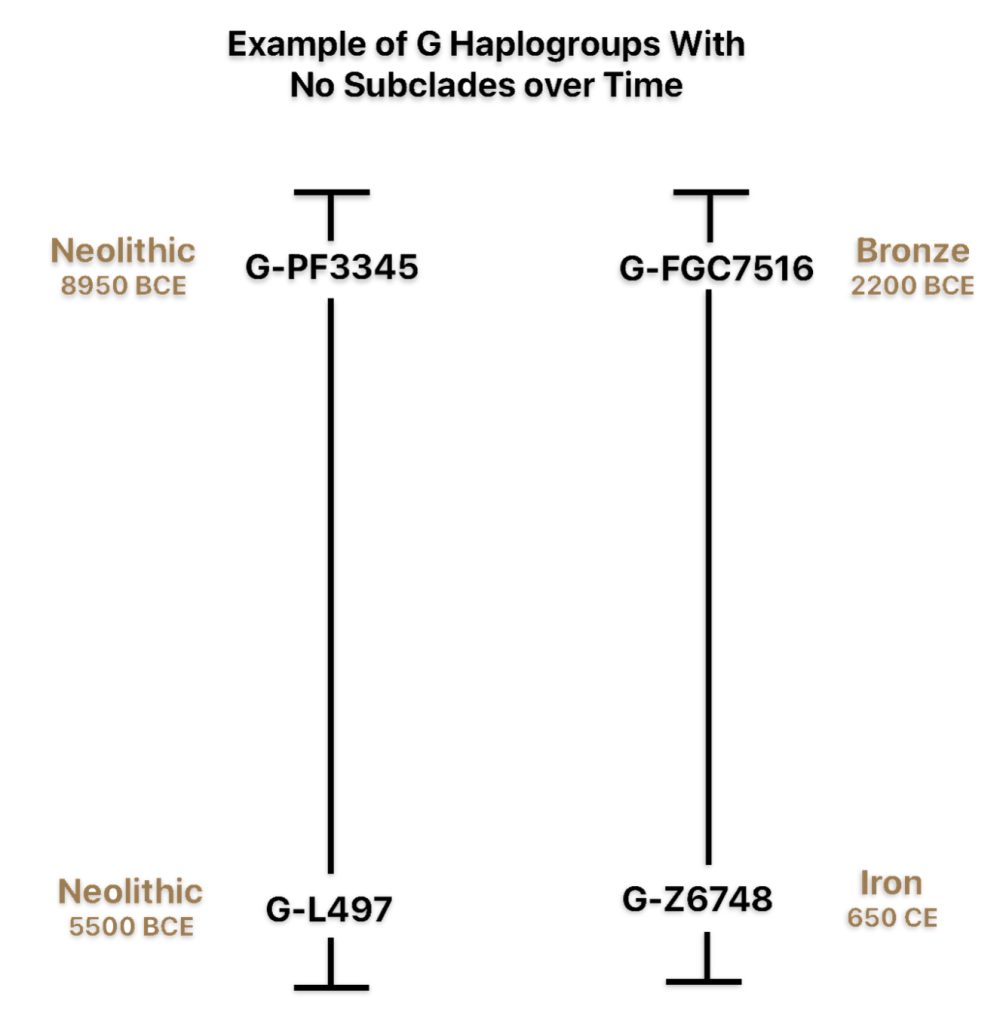

Some branches of its subclades have long branches and deep-rooting nodes (ancestors). This is reflected in in two notable historic periods that are associated with my Y-DNA lineage, such as the G-PF3345 and G-FGC7515 haplogroups (see illustration elevin).

Illustration Elevin: G Haplogroups with Long Branches

The expansion and contraction of Y-chromosomal subclades across Europe reflect a complex interplay of demographic migrations, cultural transitions, and genetic drift. Over millennia, paternal lineages associated with haplogroups such as G2a, R1b, R1a, I2a, and N1c1 underwent rapid geographical expansion due to founder effects, male-mediated population movements, and technological innovations. These expansions were often tied to transformative periods in European prehistory, including post-glacial recolonization, the Neolithic Revolution, and Bronze Age pastoralist migrations.

Phylogenetic Comparisons Between European Haplogroups

Phylogenetic resolution refers to how accurately and specifically a phylogenetic tree depicts the evolutionary relationships between tMRCAs. A ‘fully resolved’ tree shows clear, bifurcating relationships with each internal node (most recent common ancestor) having two descendants, while a tree with polytomies (multiple branches emerging from a single node) indicates unresolved relationships. [49]

The phylogenetic resolution of haplogroup G is relatively limited compared to other major European Y-DNA haplogroups, such as haplogroups I and R1a, primarily due to differences in demographic history, geographic dispersal patterns, and population dynamics. Haplogroup G had fewer subclades and limited branching, localized pockets of distribution, strong founder effects and limited genetic diversity, and cultural isolation or assmilation into other cultures through time.

Table Two: Comparison of Phylogenetic Characeristics between Haplogroups G, I and R1a

| Aspect | Haplogroup G | Haplogroup I | Haplogroup R1a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Resolution | Moderate to low; fewer subclades identified, limited branching complexity [50] | High; clearly defined subclades with distinct geographic distributions [51] | High; extensive branching and detailed substructure characterized [52] |

| Geographic Distribution | Localized pockets (e.g., Alps, Sardinia, Crete); isolated populations with limited gene flow [53] | Widespread across Europe, multiple geographically distinct subclades (e.g., Scandinavia vs. Balkins). [54] | Widely dispersed across Europe and Asia; clear regional substructure (e.g., Z280 in Europe, Z93 in Asia) [55] |

| Founder Effects / Bottlenecks | Strong founder effects due to Neolithic agricultural expansions from Near East into Europe; limited initial genetic diversity carried forward [56] | Postglacial recolonization from multiple refuge areas; distinct expansions from diverse source populations. [57] | Multiple expansions from Near East/Central Asia; diversification events well-documented through ancient migrations. [58] |

| Geographic Distribution | Concentrated pockets e.g., Tyrol, Sardinia, Crete; limited clinal patterns; indicative of isolation by distance. [59] | Clear geographic gradients and distinct regional peaks (Scandinavia, Dinaric Alps); clinal patterns evident. [60] | Extensive geographic distribution with clear regional differentiation; basal branches found primarily in Iran/Turkey region. [61] |

| Cultural/ Demographic Factors | Strongly associated with early Neolithic agricultural expansions; founder effects and cultural isolation restricted diversification. [62] | Associated with postglacial recolonization events and subsequent demographic expansions; multiple regional founder effects created distinct branches. [63] | Associated with Bronze Age Indo-European migrations; rapid expansions from small founder populations allowed clear substructure development [64] . |

Limitations Associated with the Use and Interpretation of Y-DNA Phylogenetic Trees

The reconstruction of Y-DNA phylogenetic trees has revolutionized our understanding of paternal lineage evolution, population migrations, and historical demographic processes. However, these analyses are constrained by several technical, methodological, and biological limitations. Y-DNA phylogenies must be interpreted with caution, acknowledging their inherent uncertainties and contextualizing findings within broader genomic and historical frameworks.

Key challenges include variability in mutation rates across haplogroups, biases in sequencing and sampling, limitations of analytical models, and the inherent complexities of the Y chromosome’s non-recombining structure. Additionally, factors such as homoplasy in short tandem repeats (STRs) [65] , evolving nomenclature systems, and population-specific historical events further complicate the interpretation of Y-DNA phylogenies.

A foundational assumption in Y-DNA phylogenetic dating is that mutation rates remain constant across lineages. However, empirical evidence demonstrates significant inter-haplogroup variation in mutation rates. For instance, studies analyzing whole-genome sequences from over 1,700 males revealed up to an 83 percent difference in somatic mutation rates between haplogroups, correlating with phylogenetic branch length heterogeneity. [66] These discrepancies distort time to most recent common ancestor (TMRCA) estimates, as branches with slower mutation rates appear artificially elongated, while rapidly mutating lineages seem younger than their true age. [67]

The reliance on “evolutionary rates” derived from population data or pedigree studies introduces additional uncertainty. [68] This is exacerbated by the tendency of certain STRs to undergo backmutations, which obscure true phylogenetic relationships and inflate TMRCA estimates. [69]

Most Y-DNA data derive from modern populations, with limited ancient DNA representation. This temporal gap complicates efforts to resolve historical migration events or validate putative branching orders. For example, the coalescence time of R1a-M417 (approiximately 5,800 years ago) relies heavily on modern sequences, which may not capture extinct subclades that diversified during the Neolithic or Bronze Age. [70] This may be the case with many of the haplogrous associated with the Griff(is)(es)(ith) patrlineal genetic line.

Source:

Feature Banner: The banner at the top of the story is a portrayal of two phylogenetic trees that depict portions of the G haplogroup migratory route for my terminal haplogroup in Wales.

The phylogenetic tree on the left hand side reflects the phylogenetic tree of Haplogroup G2a-L140. The haplgroup G2a-L140 is most commonly found in Europe, particularly in northern and western regions. The haplogroup is believed to have entered Europe during the Neolithic period, associated with the spread of agriculture. The upstream mutations include M201 > L89 > P15 > L1259 > L30 > L141 > P303 > L140. See Hay, Maciamo, Phylogeny of G2a, Haplogroup G2a, July 2023, Eupedia, https://www.eupedia.com/europe/Haplogroup_G2a_Y-DNA.shtml

The hylogenetic tree on the right is a continuation of the haplogroups linked from one of the common ancestors associated with haplogroup G-Y8903 / FGC477 that is indicated in the phylogenetic tree on the left. The descendant asociated with this haplogroup was born around 2250 BCE. The tree on the right is based on YDNA FamilyTreeDNA test kit results. Names that appear on this chart indicate persons whose YDNA testing results identified a new branch. These SNP branches are hundreds or thousands of years old and each may include many other surnames besides those shown in the chart. Source: Rolf Langland and Mauricio Catelli, Haplogroup G –L497 Chart D: FGC477 Branch, 30 Jan 2025, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1iizSCGkw_8x2cAqm2Evv-b_ZSxY40E1j/view

It is noted that my Y-700 DNA test results identified a new branch, as reflected in the phylogenetic tree. Click here for larger version of the banner image

[1] Zou Y, Zhang Z, Zeng Y, Hu H, Hao Y, Huang S, Li B. Common Methods for Phylogenetic Tree Construction and Their Implementation in R. Bioengineering (Basel). 2024 May 11;11(5):480. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering11050480. PMID: 38790347; PMCID: PMC11117635, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11117635/

Understanding phylogenies, Understanding Evolution, Evolution 101, University of California Berkley https://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolution-101/the-history-of-life-looking-at-the-patterns/understanding-phylogenies/

Phylogenetic tree, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 26 February 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phylogenetic_tree

Boudreau, Sarah, What’s the difference between a cladogram and a phylogenetic tree?, 28 Apr 2023, Visible Body, https://www.visiblebody.com/blog/phylogenetic-trees-cladograms-and-how-to-read-them

[2] Big Y-700: The Forefront of y Chromosome, 7 Jun 2019, FamilyTreeDNA Blog, https://blog.familytreedna.com/human-y-chromosome-testing-milestones/

Caleb Davis, Michael Sager, Göran Runfeldt, Elliott Greenspan, Arjan Bormans, Bennett Greenspan, and Connie Bormans, Big Y-700 White Paper, 22 Mar 2019, https://blog.familytreedna.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/big-y-700-white-paper_compressed.pdf

[3] A most recent common ancestor (MRCA) is the closest individual from whom all members of a specified group of people are directly descended. In genetic genealogy, this concept applies to both biological organisms and groups of genes (haplotypes).

Estes, Roberta, What Does MCRA (MRCA) Really Mean??, 6 Aug 2012, DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy, https://dna-explained.com/2012/08/06/what-does-mcra-really-mean/

Most recent common ancestor, International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki, This page was last edited on 31 January 2017,https://isogg.org/wiki/Most_recent_common_ancestor

Most common recent ancestor, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 12 February 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Most_recent_common_ancestor

[4] Spencer, Rob, Data Source and SNP Dates, Discussion, SNP Tracker, https://scaledinnovation.com/gg/snpTracker.html

Batini, C., Hallast, P., Zadik, D., Maisano Delser, P., Benazzo, A., Ghirotto, S., Arroyo-Pardo, E., Cavalleri, G.L., de Knijff, P., Myhre Dupuy, B., Eriksen, H.A, King, T.E., López de Munain, A., López-Parra, A.M., Loutradis, A., Milasin, J., Novelletto, A., Pamjav, H., Sajantila, A., Tolun, A., Winney, B., and JOBLING, M.A. (2015) Large-scale recent expansion of European patrilineages shown by population resequencing. Nature Comm., 6, 7152. doi:10.1038/ncomms8152, (PubMed) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25988751/

Hallast, P., Batini, C., Zadik, D., Maisano Delser, P., Wetton, J.H., Arroyo-Pardo, E., Cavalleri, G.L., de Knijff, P., Destro Bisol, G., Myhre Dupuy, B., Eriksen, H.A, Jorde, L.B., King, T.E., Larmuseau, M.H., López de Munain, A., López-Parra, A.M., Loutradis, A., Milasin, J., Novelletto, A., Pamjav, H., Sajantila, A., Schempp, W., Sears, M., Tolun, A., Tyler-Smith, Van Geystelen, A., Watkins, S., Winney, B., and JOBLING, M.A. (2015) The Y-chromosome tree bursts into leaf: 13,000 high-confidence SNPs covering the majority of known clades. Mol. Biol. Evol., 32, 661–673. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu327 , (PubMed). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25988751/

Zeng, T.C., Aw, A.J. and Feldman, M.W., 2018. Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck. Nature communications, 9(1), p.2077.

[5] Violatti, Christian Neolithic Period , World History Encyclopedia, 2 Apr 2018 https://www.worldhistory.org/Neolithic/

[6] Zeng, T.C., Aw, A.J. & Feldman, M.W. Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck. Nat Commun 9, 2077 (2018), page1, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04375-6

[7] Ibid

[8] Miller, Mark, Most European Men are Descended from just Three Bronze Age Warlords, New Study Reveals, 25 may 2015, Ancient Origins, https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-evolution-human-origins/most-european-men-are-descended-just-three-bronze-age-warlords-new-020361

Batini, C., Hallast, P., Zadik, D. et al. Large-scale recent expansion of European patrilineages shown by population resequencing. Nat Commun 6, 7152 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8152

[9] Abrams, Joel, A handful of Bronze-Age men could have fathered two thirds of Europeans, 21 May 2015, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/a-handful-of-bronze-age-men-could-have-fathered-two-thirds-of-europeans-42079

Curry, Andrew, The First Europeans Weren’t Who Your Might Think, National Geographic Magazine, August 2019, online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/first-europeans-immigrants-genetic-testing-feature

[10] Hay, Maciamo, Phylogenetic trees of Y-chromosomal haplogroups, May 2017, Eupedia, https://www.eupedia.com/genetics/phylogenetic_trees_Y-DNA_haplogroups.shtml

Curry, Andrew, The First Europeans Weren’t Who Your Might Think, National Geographic Magazine, August 2019, online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/first-europeans-immigrants-genetic-testing-feature

Howard III, William and Frederic R. Schwab, Dating Y-DNA Haplotypes on a Phylogentic Tree: Tying the Genealogy of Pedigrees and Surname Clusters into Genetic Time Scales, Journal of Genetic Genealogy, Volume 7, Number 1 (Fall 2011) Reference Number: 71.005, https://jogg.info/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/71.005.pdf

[11] The animation was produced by a FamilyTreeDNA (FTDNA) online program called Globetrekker TM. It is a specialized mapping tool developed by FTDNA as an exclusive feature for their Big Y-DNA test customers. It visualizes ancestral migration paths on a global scale, tracing paternal lineage journeys from “Y-Adam” (the earliest common paternal ancestor, approximately 200,000 years ago) to the most recent known locations of direct paternal ancestors. Globetrekker employs phylogenetic algorithms that factor in geographical topography, historical sea levels, land elevations, and ice age glaciation patterns to determine likely ancestral migration routes.

The following are key features of the Globetrekker program:

Integrated Phylogenetic Tree Browser: An integrated tree browser allows the use to view specific migratory paths based on a chosen terminal haplogroup.

Extensive Data: Globetrekker utilizes the largest Y-DNA tree and a comprehensive database of high-resolution DNA samples, including detailed paternal ancestral information.

Advanced Algorithms: It employs sophisticated phylogenetic algorithms that incorporate topographical data, historical global sea levels, land elevation, and ice age glaciation to accurately reconstruct ancient migration routes.

Historical Maps: The tool provides interactive world maps depicting ancient sea levels and landforms, such as Doggerland during the Last Glacial Maximum.

Personalized Animation: Users receive a customized animation illustrating 200,000 years of their paternal lineage history.

Extensive Migration Paths: Globetrekker currently includes over 48,000 paternal line migration paths covering every populated continent, with new paths regularly added.

Globetrekker’s main limitation is the relatively small number of available Big Y-DNA samples. As more individuals participate in Big Y testing, the accuracy and granularity of migration paths are expected to improve significantly over time. The video is based on the migration mapping for the terminal haplogroup for G-Y132505.

Estes, Roberta, Globetrekker – A New Feature for Big Y Customers from FamilyTreeDNA, 4 Aug 2023, DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy, https://dna-explained.com/2023/08/04/globetrekker-a-new-feature-for-big-y-customers-from-familytreedna/

Runfeldt, Goran , Globertrekker, Part 1: A NewFamilyTreeDNA Discover™ Report that Puts Big Y on the Map, 31 Jul 2023, FamilyTreeDNA Blog, https://blog.familytreedna.com/globetrekker-discover-report/

Maier, Paul, Globetrekker, Part 2: Advancing the Science of Phylogeography, 15 Aug 2023, FamilyTreeDNA Blog, https://blog.familytreedna.com/globetrekker-analysis/

Vilar, Miguel, Globetrekker, Part 3: We Are Making History, 26 Sep 2023, FamilyTreeDNA Blog, https://blog.familytreedna.com/globetrekker-history/

[12] Doggerland was a vast landmass that once connected the British Isles to mainland Europe, encompassing areas now submerged beneath the North Sea and the English Channel. Named after Dogger Bank, a submerged sandbank frequented by Dutch fishing vessels known as “doggers,” Doggerland existed primarily during the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene periods, approximately 10,000 to 6,500 years ago.

Doggerland, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 10 March 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doggerland

James Walker, Vincent Gaffney, Simon Fitch, Merle Muru, Andrew Fraser, Martin Bates and Richard Bates, A great wave: the Storegga tsunami and the end of Doggerland?, Antiquity , Volume 94 , Issue 378 , December 2020 , pp. 1409 – 1425 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.49 , https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/great-wave-the-storegga-tsunami-and-the-end-of-doggerland/CB2E132445086D868BF508041CC1B827#article

Urbanus, Jason, Mapping a Vanished Landscape, Archaelogy magazine, March/April 2022, https://archaeology.org/issues/march-april-2022/letters-from/doggerland-mesolithic-submerged-landscape/

De Abreu, Kristine, Exploration Mysteries: Doggerland, 13 Feb 2024, Explorersweb, https://explorersweb.com/exploration-mysteries-doggerland/

[13] Balaresque P, Bowden GR, Adams SM, Leung HY, King TE, Rosser ZH, Goodwin J, Moisan JP, Richard C, Millward A, Demaine AG, Barbujani G, Previderè C, Wilson IJ, Tyler-Smith C, Jobling MA. A predominantly neolithic origin for European paternal lineages. PLoS Biol. 2010 Jan 19;8(1):e1000285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000285. PMID: 20087410; PMCID: PMC2799514, PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8228294/

Semino O, Magri C, Benuzzi G, Lin AA, Al-Zahery N, Battaglia V, Maccioni L, Triantaphyllidis C, Shen P, Oefner PJ, Zhivotovsky LA, King R, Torroni A, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Underhill PA, Santachiara-Benerecetti AS. Origin, diffusion, and differentiation of Y-chromosome haplogroups E and J: inferences on the neolithization of Europe and later migratory events in the Mediterranean area. Am J Hum Genet. 2004 May;74(5):1023-34. doi: 10.1086/386295. Epub 2004 Apr 6. PMID: 15069642; PMCID: PMC1181965, (PubMed)https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1181965

Genetic history of Europe, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 24 February 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genetic_history_of_Europe

Rootsi, S., Myres, N., Lin, A. et al. Distinguishing the co-ancestries of haplogroup G Y-chromosomes in the populations of Europe and the Caucasus. Eur J Hum Genet 20, 1275–1282 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.86

E.K. Khusnutdinova, N.V. Ekomasova, M.A. Dzhaubermezov, L.R. Gabidullina, Z.R. Sufianova1, I.M. Khidiyatova, A.V. Kazantseva, S.S. Litvinov, A.Kh. Nurgalieva, D.S. Prokofieva, Distribution of Haplogroup G-P15 of the Y-chromosome Among Representatives of Ancient cultures and Modern Populations of Northern Eurasia, Opera Med Physiol. 2023. Vol. 10 (4), 57-72, doi: 10.24412/2500-2295-2023-4-57-72, https://operamedphys.org/system/tdf/pdf/06_DISTRIBUTION%20OF%20HAPLOGROUP%20G-P15_0.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=555&force=0

Maciamo, Hay, Phylogeny of G2a, Haplogroup G2a, July 2023, Eupedia, https://www.eupedia.com/europe/Haplogroup_G2a_Y-DNA.shtml

[14] The Neolithic agricultural expansion, also known as the Neolithic Revolution, was a pivotal period in human history marked by the transition from hunter-gatherer lifestyles to settled agricultural communities, starting around 10,000 years ago. Agricultural and husbandry practices originated 10,000 years ago in a region of the Near East known as the Fertile Crescent. According to the archaeological record this phenomenon, known as “Neolithic”, rapidly expanded from these territories into Europe.

Main Archaeological Sites of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period, BCE c. 7500, in the “Fertile Crescent”

Source: Neolithic Revolution, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 1 March 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neolithic_Revolution

Mesolithic Tribes and the Origins of Agriculture in the Near East (9000-7000 BCE)

[15] Neolithic, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 18 March 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neolithic

[16] Ancient DNA from the Treilles group in southern France (c. 3000 BCE) revealed that nintey percent of male remains belonged to G2a, with mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) showing affinity to Neolithic Aegean populations. This genetic profile supports a maritime migration route linking Anatolia to Iberia via Crete and the Adriatic. Notably, the absence of the N1a mtDNA haplogroup—common in Central European Neolithic groups—in Treilles samples underscores the genetic distinctiveness of Mediterranean versus Danubian Neolithic expansions.

M. Lacan, C. Keyser, F. Ricaut, N. Brucato, F. Duranthon, J. Guilaine, E. Crubézy, & B. Ludes, Ancient DNA reveals male diffusion through the Neolithic Mediterranean route, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 (24) 9788-9791,https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1100723108 (2011)

Fort, J., Pérez-Losada, J. Interbreeding between farmers and hunter-gatherers along the inland and Mediterranean routes of Neolithic spread in Europe. Nat Commun 15, 7032 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51335-4

Anna Szécsényi-Nagy , Guido Brandt , Wolfgang Haak , Victoria Keerl , János Jakucs , Sabine Möller-Rieker , Kitti Köhler , Balázs Gusztáv Mende , Krisztián Oross , Tibor Marton , Anett Osztás , Viktória Kiss , Marc Fecher , György Pálfi , Erika Molnár , et al, Tracing the genetic origin of Europe’s first farmers reveals insights into their social organization, 22 Apr 2015, Volume 282, Issue 1805, Proceedings of the royal Society Biological Sciences, https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2015.0339

[17] Fort, J., Pérez-Losada, J. Interbreeding between farmers and hunter-gatherers along the inland and Mediterranean routes of Neolithic spread in Europe. Nat Commun 15, 7032 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51335-4

Anna Szécsényi-Nagy , Guido Brandt , Wolfgang Haak , Victoria Keerl , János Jakucs , Sabine Möller-Rieker , Kitti Köhler , Balázs Gusztáv Mende , Krisztián Oross , Tibor Marton , Anett Osztás , Viktória Kiss , Marc Fecher , György Pálfi , Erika Molnár , et al, Tracing the genetic origin of Europe’s first farmers reveals insights into their social organization, 22 Apr 2015, Volume 282, Issue 1805, Proceedings of the royal Society Biological Sciences, https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2015.0339

Myres NM, Rootsi S, Lin AA, Järve M, King RJ, Kutuev I, Cabrera VM, Khusnutdinova EK, Pshenichnov A, Yunusbayev B, Balanovsky O, Balanovska E, Rudan P, Baldovic M, Herrera RJ, Chiaroni J, Di Cristofaro J, Villems R, Kivisild T, Underhill PA. A major Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b Holocene era founder effect in Central and Western Europe. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011 Jan;19(1):95-101. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.146. Epub 2010 Aug 25. PMID: 20736979; PMCID: PMC3039512, (PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3039512/

[18] Szécsényi-Nagy A, Brandt G, Haak W, Keerl V, Jakucs J, Möller-Rieker S, Köhler K, Mende BG, Oross K, Marton T, Osztás A, Kiss V, Fecher M, Pálfi G, Molnár E, Sebők K, Czene A, Paluch T, Šlaus M, Novak M, Pećina-Šlaus N, Ősz B, Voicsek V, Somogyi K, Tóth G, Kromer B, Bánffy E, Alt KW. Tracing the genetic origin of Europe’s first farmers reveals insights into their social organization. Proc Biol Sci. 2015 Apr 22;282(1805):20150339. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.0339. PMID: 25808890; PMCID: PMC4389623, PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4389623/

[19] Myres NM, Rootsi S, Lin AA, Järve M, King RJ, Kutuev I, Cabrera VM, Khusnutdinova EK, Pshenichnov A, Yunusbayev B, Balanovsky O, Balanovska E, Rudan P, Baldovic M, Herrera RJ, Chiaroni J, Di Cristofaro J, Villems R, Kivisild T, Underhill PA. A major Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b Holocene era founder effect in Central and Western Europe. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011 Jan;19(1):95-101. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.146. Epub 2010 Aug 25. PMID: 20736979; PMCID: PMC3039512, (PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3039512/

Hay, Maciamo, Haplogroup G2a (Y-DNA), July 2023, Eupeda, https://www.eupedia.com/europe/Haplogroup_G2a_Y-DNA.shtml

[20] Chiaroni J, Underhill PA, Cavalli-Sforza LL. Y chromosome diversity, human expansion, drift, and cultural evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Dec 1;106(48):20174-9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910803106. Epub 2009 Nov 17. Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Jul 27;107(30):13556. PMID: 19920170; PMCID: PMC2787129, PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2787129/

Myres NM, Rootsi S, Lin AA, et al, A major Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b Holocene era founder effect in Central and Western Europe. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011 Jan;19(1):95-101. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.146. Epub 2010 Aug 25. PMID: 20736979; PMCID: PMC3039512, (PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3039512/

[21] Penske, S., Rohrlach, A.B., Childebayeva, A. et al. Early contact between late farming and pastoralist societies in southeastern Europe. Nature 620, 358–365 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06334-8

Haak W, Lazaridis I, Patterson N, Rohland N, Mallick S, Llamas B, Brandt G, Nordenfelt S, Harney E, Stewardson K, Fu Q, Mittnik A, Bánffy E, Economou C, Francken M, Friederich S, Pena RG, Hallgren F, Khartanovich V, Khokhlov A, Kunst M, Kuznetsov P, Meller H, Mochalov O, Moiseyev V, Nicklisch N, Pichler SL, Risch R, Rojo Guerra MA, Roth C, Szécsényi-Nagy A, Wahl J, Meyer M, Krause J, Brown D, Anthony D, Cooper A, Alt KW, Reich D. Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature. 2015 Jun 11;522(7555):207-11. doi: 10.1038/nature14317. Epub 2015 Mar 2. PMID: 25731166; PMCID: PMC5048219, (PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5048219/

[22] Hay, Maciamo, Haplogroup G2a (Y-DNA), Jul 2023, Eupedia, https://www.eupedia.com/europe/Haplogroup_G2a_Y-DNA.shtml

Lamnidis, T.C., Majander, K., Jeong, C. et al. Ancient Fennoscandian genomes reveal origin and spread of Siberian ancestry in Europe. Nat Commun 9, 5018 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07483-5

[23] Hay, Maciamo, Phylogenetic trees of Y-chromosomal haplogroups, May 2017, Eupedia, https://www.eupedia.com/genetics/phylogenetic_trees_Y-DNA_haplogroups.shtml#IntroductionHuman Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 31 December 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_Y-chromosome_DNA_haplogroup

Dunn, Casey W., Chapter 9 Phylogenies and time, Phylogenetic Biology, 28 Oct 2024, Text for course, Phylogenetic Biology (Yale EEB354), licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. It is available to read online for free at https://dunnlab.org/phylogenetic_biology/phylogenies.html#trees-branch-lengths

Hay, Maciamo, Phylogenetic trees of Y-chromosomal haplogroups, May 2017, Eupedia, https://www.eupedia.com/genetics/phylogenetic_trees_Y-DNA_haplogroups.shtml#Introduction

[24] Batini, C., Hallast, P., Zadik, D. et al. Large-scale recent expansion of European patrilineages shown by population resequencing. Nat Commun 6, 7152 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8152

[25] Hay, Maciamo, Phylogenetic trees of Y-chromosomal haplogroups, May 2017, Eupedia, https://www.eupedia.com/genetics/phylogenetic_trees_Y-DNA_haplogroups.shtml#IntroductionHuman Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 31 December 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_Y-chromosome_DNA_haplogroup

[26] These estimates derive from large-scale sequencing datasets, pedigree studies, and comparative analyses of haplogroup differentiations. Key factors influencing this range include the coverage of the male-specific Y chromosome (MSY) region, the mutation rate per base pair, and the statistical models used to account for uncertainties in SNP counting and temporal calibration. [26a]

Mutation rate estimates differ across sequencing technologies. There are three notable testing platforms. The FamilyTreeDNA (FTDNA) Big Y-700 test analyzes approximately 14.6 million base pairs, yielding an average mutation rate of 83–85 years per SNP. This estimate, derived from YDNA Warehouse data, reflects high-coverage regions deemed reliable for genealogical applications. [26b] The FTDNA BigY-500 test covers 9.3 million base pairs, resulting in a slower rate of 131 years per SNP due to reduced coverage compared to BigY-700. [26c] The YFull (ComBed) coverage test uses 8.5 million base pairs and reports 144 years per SNP, prioritizing conservative regions (comBED) to minimize false positives. [26d]

Based on academic and ‘consensus’ estimates, evolutionary rates, calibrated using ancient DNA or historical events, suggest 0.75–0.89 substitutions per billion base pairs per year (equivalent to 83–89 years/SNP for typical sequencing lengths). Genealogical (pedigree) rates, observed in father-son studies, are slightly faster due to shorter generational intervals. Iain McDonald’s analysis of 15 million base pairs estimates 83–186 years per SNP, with higher values reflecting conservative adjustments for regions with variable coverage. [26e]

[26a] Irvine, James M., Y-DNA SNP-Based TMRCA Calculations for Surname Project Administrators, Journal of Genetic Genealogy, Volume 9, Number 1 (Fall 2021), Reference Number: 91.007, https://jogg.info/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/91.007-Article.pdf

SNP Dating, Genomic Genealogy Research, University of Strathclyde Glasgow, https://www.strath.ac.uk/studywithus/centreforlifelonglearning/genealogy/geneticgenealogyresearch/snpdating/

Balanovsky O. Toward a consensus on SNP and STR mutation rates on the human Y-chromosome. Hum Genet. 2017 May;136(5):575-590. doi: 10.1007/s00439-017-1805-8. Epub 2017 Apr 28. PMID: 28455625, (PubMed) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28455625/

[26b] SNP Dating, Genomic Genealogy Research, University of Strathclyde Glasgow, https://www.strath.ac.uk/studywithus/centreforlifelonglearning/genealogy/geneticgenealogyresearch/snpdating/

[26c] McDonald, Ian, SNP-based age analysis methodology: a summary

Summarised description of the age analysis pipeline, June 2017, https://www.jb.man.ac.uk/~mcdonald/genetics/pipeline-summary.pdf

[26d] Ibid

[26e] Balanovsky O. Toward a consensus on SNP and STR mutation rates on the human Y-chromosome. Hum Genet. 2017 May;136(5):575-590. doi: 10.1007/s00439-017-1805-8. Epub 2017 Apr 28. PMID: 28455625, (PubMed) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28455625/

McDonald, Ian, SNP-based age analysis methodology: a summary, Summarised description of the age analysis pipeline, June 2017, https://www.jb.man.ac.uk/~mcdonald/genetics/pipeline-summary.pdf

[27] The interpretation of branch lengths depends heavily on mutation rate calculations. The standard deviation in branch lengths from high-coverage sequences is relatively low (around 4 percent). This allows for precise temporal estimates. High-coverage DNA sequencing has identified mutation rates of approximately 2-3 base pairs per generation.

Jeanson, Nathaniel, 4 Dec, 2019, Answers Research Journal (ARJ), 12: 405-423, https://answersresearchjournal.org/human-y-chromosome-molecular-clock/

There is ongoing disagreement about the temporal interpretation of Y-chromosome branch lengths. Some researchers argue for a longer timescale of 120-156 thousand years to the most recent common ancestor while others propose much shorter timescales of just a few thousand years. See:

Jeanson, Nathaniel, 4 Dec, 2019, Answers Research Journal (ARJ), 12: 405-423, https://answersresearchjournal.org/human-y-chromosome-molecular-clock/

Poznik GD, Henn BM, Yee MC, Sliwerska E, Euskirchen GM, Lin AA, Snyder M, Quintana-Murci L, Kidd JM, Underhill PA, Bustamante CD. Sequencing Y chromosomes resolves discrepancy in time to common ancestor of males versus females. Science. 2013 Aug 2;341(6145):562-5. doi: 10.1126/science.1237619. PMID: 23908239; PMCID: PMC4032117, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4032117/

[28] Dunn, Casey W., Chapter 9 Phylogenies and time, Phylogenetic Biology, 28 Oct 2024, Text for course, Phylogenetic Biology (Yale EEB354), licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. It is available to read online for free at http://dunnlab.org/phylogenetic_biology/

[29] Poznik GD, et al, Sequencing Y chromosomes resolves discrepancy in time to common ancestor of males versus females. Science. 2013 Aug 2;341(6145):562-5. doi: 10.1126/science.1237619. PMID: 23908239; PMCID: PMC4032117, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4032117/

[30] Cruciani F, Trombetta B, Massaia A, Destro-Bisol G, Sellitto D, Scozzari R. A revised root for the human Y chromosomal phylogenetic tree: the origin of patrilineal diversity in Africa. Am J Hum Genet. 2011 Jun 10;88(6):814-818. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.002. Epub 2011 May 27. PMID: 21601174; PMCID: PMC3113241, (PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3113241/

[31] Y Chromosome Consortium. A nomenclature system for the tree of human Y-chromosomal binary haplogroups. Genome Res. 2002 Feb;12(2):339-48. doi: 10.1101/gr.217602. PMID: 11827954; PMCID: PMC155271, 9PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC155271/

Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 31 December 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_Y-chromosome_DNA_haplogroup

[32] Hay, Maciamo, Phylogenetic trees of Y-chromosomal haplogroups, May 2017, Eupedia, https://www.eupedia.com/genetics/phylogenetic_trees_Y-DNA_haplogroups.shtml#Introduction

[33] Tunde I. Huszar, Mark A. Jobling, Jon H. Wetton,

A phylogenetic framework facilitates Y-STR variant discovery and classification via massively parallel sequencing, Forensic Science International: Genetics, Volume 35, 2018, Pages 97-106, ISSN 1872-4973, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2018.03.012.

(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1872497318300279 )

Phylogenetics, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 12 February 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phylogenetics

[34] Rowe-Schurwanz, Katy, How Y-DNA Testing Works, 3 Jun 2024, FamilyTreeDNA Blog, https://blog.familytreedna.com/how-y-dna-testing-works/

Y chromosome DNA tests, International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki, This page was last edited on 6 September 2024, https://isogg.org/wiki/Y_chromosome_DNA_tests

[35] William E. Howard III and Frederic R. Schwab, Dating Y-DNA Haplotypes on a Phylogenetic Tree: Tying the Genealogy of Pedgrees and Surname Clusters into Genetic Time Scales, Journal of Genetic Genealogy, Volume 7, Number 1 (Fall 2011) Reference Number: 71.005, https://jogg.info/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/71.005.pdf

Köksal Z, Børsting C, Gusmão L, Pereira V. SNPtotree-Resolving the Phylogeny of SNPs on Non-Recombining DNA. Genes (Basel). 2023 Sep 22;14(10):1837. doi: 10.3390/genes14101837. PMID: 37895186; PMCID: PMC10606150, (PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10606150/

Tunde I. Huszar, Mark A. Jobling, Jon H. Wetton, A phylogenetic framework facilitates Y-STR variant discovery and classification via massively parallel sequencing, Forensic Science International: Genetics, Volume 35, 2018, Pages 97-106, ISSN 1872-4973,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2018.03.012

Hay, Maciamo, Phylogenetic trees of Y-chromosomal haplogroups, May 2017, Eupedia, https://www.eupedia.com/genetics/phylogenetic_trees_Y-DNA_haplogroups.shtml

[36] Determination of MRCA Dates”

Calculation Models: The coalescence age (time to MRCA) is calculated using probabilistic models that consider the number of mutations and the mutation rate. These models can be refined with more data and improved algorithms 14.

Mutation Rate: The process relies on the concept of a’ molecular clock’, which assumes that mutations occur at a relatively constant rate over time. This rate is typically measured in mutations per base pair per year. For Y-DNA, mutations are often counted as Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) 12.

SNP Counting: Full Y-DNA sequencing tests, such as those from Full Genomes Corp. or FamilyTreeDNA’s Big Y, identify novel SNPs. The number of these SNPs, combined with the mutation rate, helps estimate the time to the MRCA. Different tests may yield different mutation rates; for example, Full Genomes Corp. suggests a mutation every 88 years, while Big Y suggests one every 150 years2.

McDonald Ian. Improved Models of Coalescence Ages of Y-DNA Haplogroups. Genes (Basel). 2021 Jun 4;12(6):862. doi: 10.3390/genes12060862. PMID: 34200049; PMCID: PMC8228294, (PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8228294/

Irvine, James M., Y-DNA SNP-Based TMRCA Calculations for Surname Project Administrators, Journal of Genetic Genealogy, Volume 9, Number 1 (Fall 2021), Reference Number: 91.007, https://jogg.info/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/91.007-Article.pdf

FamilyTreeDNA Enhances TMRCA Estimates for Improved Family History Research, 9 Sep 2022, FamilyTreeDNA Blog, https://blog.familytreedna.com/tmrca-age-estimates-update/

Walsh B. Estimating the time to the most recent common ancestor for the Y chromosome or mitochondrial DNA for a pair of individuals. Genetics. 2001 Jun;158(2):897-912. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.2.897. PMID: 11404350; PMCID: PMC1461668, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1461668/

Cummings, Karen, Y-DNA: New Tools from FamilyTreeDNA, Professional family History, https://www.professionalfamilyhistory.co.uk/blog/new-y-dna-new-tools-from-familytreedna

Estes, Roberta, The Big Y-700 Test Marries Science to Genealogy, 11 Jul 2024, DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealology, https://dna-explained.com/category/mrca-most-recent-common-ancestor/

Karmin M, Saag L, Vicente M, Wilson Sayres MA, et all A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture. Genome Res. 2015 Apr;25(4):459-66. doi: 10.1101/gr.186684.114. Epub 2015 Mar 13. PMID: 25770088; PMCID: PMC4381518, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4381518/

Bruce Walsh, Estimating the Time to the Most Recent Common Ancestor for the Y chromosome or Mitochondrial DNA for a Pair of Individuals, Genetics, Volume 158, Issue 2, 1 June 2001, Pages 897–912, https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/158.2.897

Qian, X., Hou, J., Wang, Z. et al. Next Generation Sequencing Plus (NGS+) with Y-chromosomal Markers for Forensic Pedigree Searches. Sci Rep 7, 11324 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11955-x

[37] McDonald Ian. Improved Models of Coalescence Ages of Y-DNA Haplogroups. Genes (Basel). 2021 Jun 4;12(6):862. doi: 10.3390/genes12060862. PMID: 34200049; PMCID: PMC8228294, (PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8228294/

[38] McDonald Ian. Improved Models of Coalescence Ages of Y-DNA Haplogroups.

Irvine, James M., Y-DNA SNP-Based TMRCA Calculations for Surname Project Administrators, Journal of Genetic Genealogy, Volume 9, Number 1 (Fall 2021), Reference Number: 91.007, https://jogg.info/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/91.007-Article.pdf

[39] Poznik GD, Henn BM, Yee MC, Sliwerska E, Euskirchen GM, Lin AA, Snyder M, Quintana-Murci L, Kidd JM, Underhill PA, Bustamante CD. Sequencing Y chromosomes resolves discrepancy in time to common ancestor of males versus females. Science. 2013 Aug 2;341(6145):562-5. doi: 10.1126/science.1237619. PMID: 23908239; PMCID: PMC4032117, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4032117/

McDonald Ian. Improved Models of Coalescence Ages of Y-DNA Haplogroups. Genes (Basel). 2021 Jun 4;12(6):862. doi: 10.3390/genes12060862. PMID: 34200049; PMCID: PMC8228294, (PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8228294/

Irvine, James M., Y-DNA SNP-Based TMRCA Calculations for Surname Project Administrators, Journal of Genetic Genealogy, Volume 9, Number 1 (Fall 2021), Reference Number: 91.007, https://jogg.info/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/91.007-Article.pdf

[40] Batini, C., Hallast, P., Zadik, D. et al. Large-scale recent expansion of European patrilineages shown by population resequencing. Nat Commun 6, 7152 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8152

[41] Hodișan R, Zaha DC, Jurca CM, Petchesi CD, Bembea M. Genetic Diversity Based on Human Y Chromosome Analysis: A Bibliometric Review Between 2014 and 2023. Cureus. 2024 Apr 18;16(4):e58542. doi: 10.7759/cureus.58542. PMID: 38887511; PMCID: PMC11182565, PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11182565/

[42] McDonald I. Improved Models of Coalescence Ages of Y-DNA Haplogroups. Genes (Basel). 2021 Jun 4;12(6):862. doi: 10.3390/genes12060862. PMID: 34200049; PMCID: PMC8228294

[43] Guyon, L., Guez, J., Toupance, B. et al. Patrilineal segmentary systems provide a peaceful explanation for the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck. Nat Commun 15, 3243 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47618-5

Karmin M, Saag L, Vicente M, Wilson Sayres MA, et all A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture. Genome Res. 2015 Apr;25(4):459-66. doi: 10.1101/gr.186684.114. Epub 2015 Mar 13. PMID: 25770088; PMCID: PMC4381518, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4381518/

[44] Chiaroni J, Underhill PA, Cavalli-Sforza LL. Y chromosome diversity, human expansion, drift, and cultural evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Dec 1;106(48):20174-9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910803106. Epub 2009 Nov 17. Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Jul 27;107(30):13556. PMID: 19920170; PMCID: PMC2787129, (PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2787129/

McDonald I. Improved Models of Coalescence Ages of Y-DNA Haplogroups. Genes (Basel). 2021 Jun 4;12(6):862. doi: 10.3390/genes12060862. PMID: 34200049; PMCID: PMC8228294, (PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8228294/

Rootsi, S., Myres, N., Lin, A. et al. Distinguishing the co-ancestries of haplogroup G Y-chromosomes in the populations of Europe and the Caucasus. Eur J Hum Genet 20, 1275–1282 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.86

[45] Guyon, L., Guez, J., Toupance, B. et al. Patrilineal segmentary systems provide a peaceful explanation for the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck. Nat Commun 15, 3243 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47618-5

[46] Linda Hellborg, Hans Ellegren, Low Levels of Nucleotide Diversity in Mammalian Y Chromosomes, Molecular Biology and Evolution, Volume 21, Issue 1, January 2004, Pages 158–163, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msh008

[47] McDonald I. Improved Models of Coalescence Ages of Y-DNA Haplogroups. Genes (Basel). 2021 Jun 4;12(6):862. doi: 10.3390/genes12060862. PMID: 34200049; PMCID: PMC8228294, (PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8228294/

[48] Long branch attraction, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 9 March 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_branch_attraction

[49] Hoelzer, Gary A. and Don J. Meinick, Patterns of speciation and limits to phylogenetic resolution, Trends in Ecology & Evolution, Volume 9, Issue 3, 1994, Pages 104-107,

https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5347(94)90207-0 , https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0169534794902070

Swenson, Nathan, Phylogenetic Resolution and Quantifying the Phylogenetic Diversity and Dispersion of Communities, , PLoS ONE, February 2009, Volume 4, Issue 2, e4390, https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0004390

[50] Haplogroup G-M201, Wikipeda, This page was last edited on 24 January 2025 ,Haplogroup_G-M201

Rootsi, S., Myres, N., Lin, A. et al. Distinguishing the co-ancestries of haplogroup G Y-chromosomes in the populations of Europe and the Caucasus. Eur J Hum Genet 20, 1275–1282 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.86

Sims LM, Garvey D, Ballantyne J. Improved resolution haplogroup G phylogeny in the Y chromosome, revealed by a set of newly characterized SNPs. PLoS One. 2009 Jun 4;4(6):e5792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005792. PMID: 19495413; PMCID: PMC2686153

[51] Rootsi S, et al Phylogeography of Y-chromosome haplogroup I reveals distinct domains of prehistoric gene flow in europe. Am J Hum Genet. 2004 Jul;75(1):128-37. doi: 10.1086/422196. Epub 2004 May 25. PMID: 15162323; PMCID: PMC1181996, (PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1181996/

[52] Underhill, P., Poznik, G., Rootsi, S. et al. The phylogenetic and geographic structure of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a. Eur J Hum Genet 23, 124–131 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2014.50

[53] Haplogroup G-M201, Wikipeda, This page was last edited on 24 January 2025 ,Haplogroup_G-M201

Rootsi, S., Myres, N., Lin, A. et al. Distinguishing the co-ancestries of haplogroup G Y-chromosomes in the populations of Europe and the Caucasus. Eur J Hum Genet 20, 1275–1282 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.86

[54] Rootsi S, et al, Phylogeography of Y-chromosome haplogroup I reveals distinct domains of prehistoric gene flow in europe. Am J Hum Genet. 2004 Jul;75(1):128-37. doi: 10.1086/422196. Epub 2004 May 25. PMID: 15162323; PMCID: PMC1181996, (PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1181996/

[55] Underhill, P., Poznik, G., Rootsi, S. et al. The phylogenetic and geographic structure of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a. Eur J Hum Genet 23, 124–131 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2014.50

[56] Rootsi, S., Myres, N., Lin, A. et al. Distinguishing the co-ancestries of haplogroup G Y-chromosomes in the populations of Europe and the Caucasus. Eur J Hum Genet 20, 1275–1282 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.86

[57] Rootsi S, et al . Phylogeography of Y-chromosome haplogroup I reveals distinct domains of prehistoric gene flow in europe. Am J Hum Genet. 2004 Jul;75(1):128-37. doi: 10.1086/422196. Epub 2004 May 25. PMID: 15162323; PMCID: PMC1181996, PubMed)

[58] Underhill, P., Poznik, G., Rootsi, S. et al. The phylogenetic and geographic structure of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a. Eur J Hum Genet 23, 124–131 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2014.50

[59] Haplogroup G-M201, Wikipeda, This page was last edited on 24 January 2025 ,Haplogroup_G-M201

Rootsi, S., Myres, N., Lin, A. et al. Distinguishing the co-ancestries of haplogroup G Y-chromosomes in the populations of Europe and the Caucasus. Eur J Hum Genet 20, 1275–1282 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.86

[60] Rootsi S, et al . Phylogeography of Y-chromosome haplogroup I reveals distinct domains of prehistoric gene flow in europe. Am J Hum Genet. 2004 Jul;75(1):128-37. doi: 10.1086/422196. Epub 2004 May 25. PMID: 15162323; PMCID: PMC1181996, PubMed)

[61] Underhill, P., Poznik, G., Rootsi, S. et al. The phylogenetic and geographic structure of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a. Eur J Hum Genet 23, 124–131 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2014.50

[62] Rootsi, S., Myres, N., Lin, A. et al. Distinguishing the co-ancestries of haplogroup G Y-chromosomes in the populations of Europe and the Caucasus. Eur J Hum Genet 20, 1275–1282 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.86

Sims LM, Garvey D, Ballantyne J. Improved resolution haplogroup G phylogeny in the Y chromosome, revealed by a set of newly characterized SNPs. PLoS One. 2009 Jun 4;4(6):e5792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005792. PMID: 19495413; PMCID: PMC2686153, (PubMed) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2686153/

[63] Rootsi S, et al . Phylogeography of Y-chromosome haplogroup I reveals distinct domains of prehistoric gene flow in europe. Am J Hum Genet. 2004 Jul;75(1):128-37. doi: 10.1086/422196. Epub 2004 May 25. PMID: 15162323; PMCID: PMC1181996, PubMed)

[64] Underhill, P., Poznik, G., Rootsi, S. et al. The phylogenetic and geographic structure of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a. Eur J Hum Genet 23, 124–131 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2014.50

[65] In the context of short tandem repeats (STRs), homoplasy refers to the situation where identical STR genotypes (or haplotypes) arise independently, meaning they are not necessarily inherited from a common ancestor, but rather due to repeated mutations or other processes. STRs are highly polymorphic, meaning they vary significantly between individuals, making them useful for forensic and genealogical studies. However, the high rate of mutation and the potential for homoplasy can complicate the interpretation of STR data, especially when comparing populations that diverged in the distant past.

Bret A. Payseur, Asher D. Cutter, Integrating patterns of polymorphism at SNPs and STRs, Trends in Genetics, Volume 22, Issue 8, 2006, Pages 424-429, ISSN 0168-9525, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.009, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168952506001776

Boattini, A., Sarno, S., Mazzarisi, A.M. et al. Estimating Y-Str Mutation Rates and Tmrca Through Deep-Rooting Italian Pedigrees. Sci Rep 9, 9032 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45398-3

[66] Qiliang Ding, Ya Hu, Amnon Koren, Andrew G Clark, Mutation Rate Variability across Human Y-Chromosome Haplogroups, Molecular Biology and Evolution, Volume 38, Issue 3, March 2021, Pages 1000–1005, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa268

[67] Boattini, A., Sarno, S., Mazzarisi, A.M. et al. Estimating Y-Str Mutation Rates and Tmrca Through Deep-Rooting Italian Pedigrees. Sci Rep 9, 9032 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45398-3