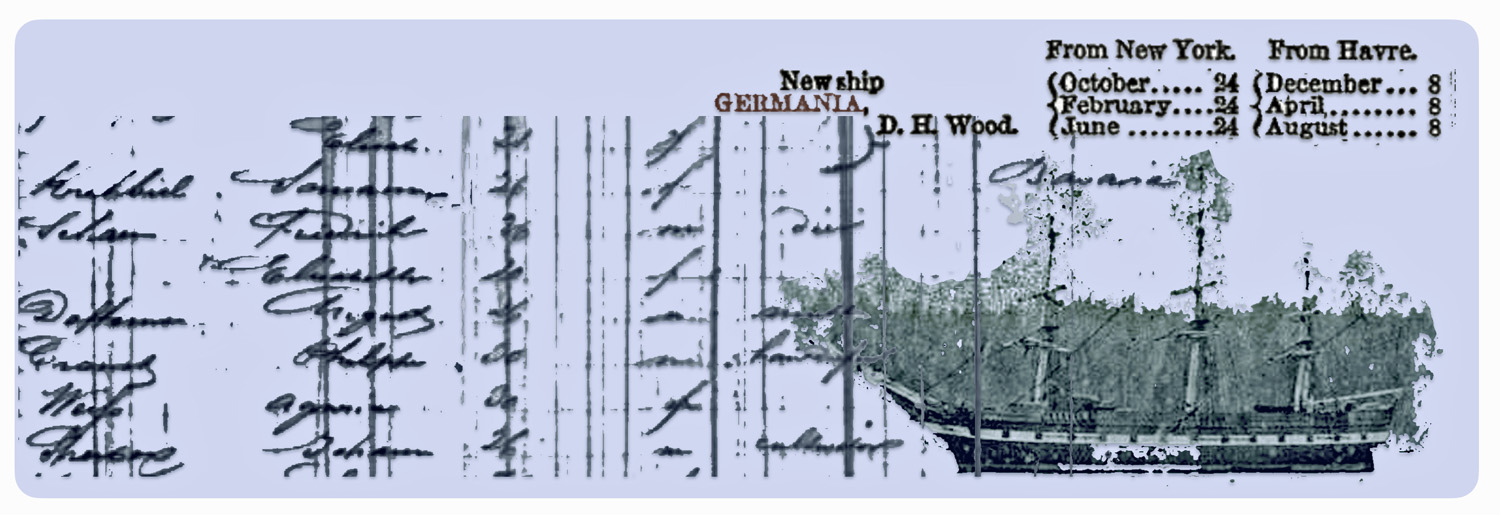

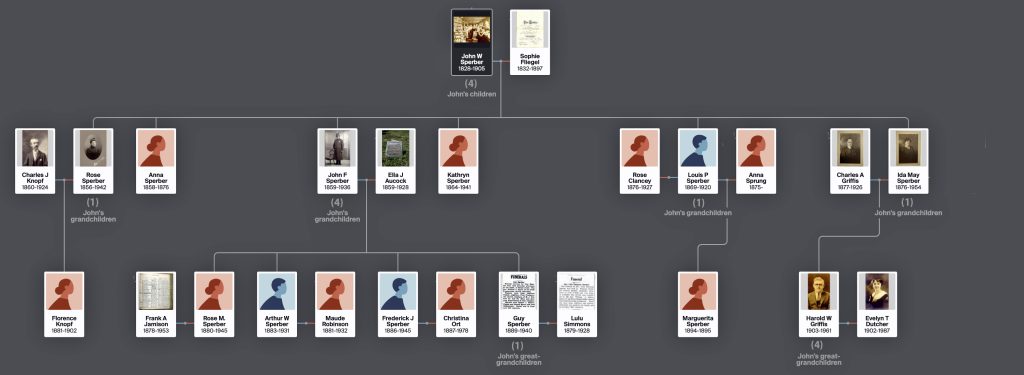

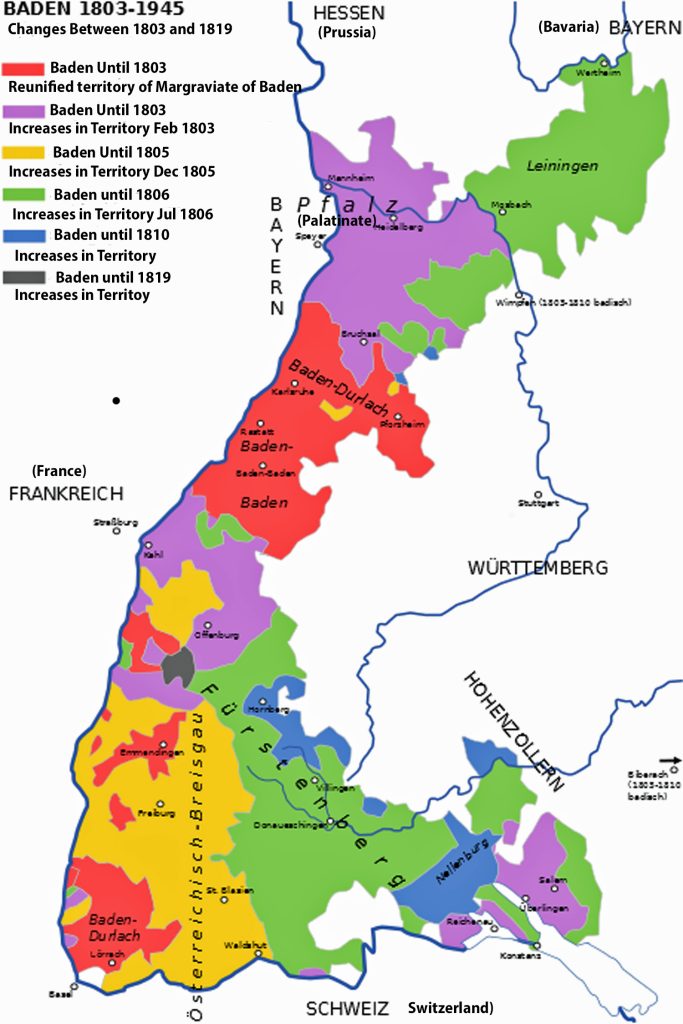

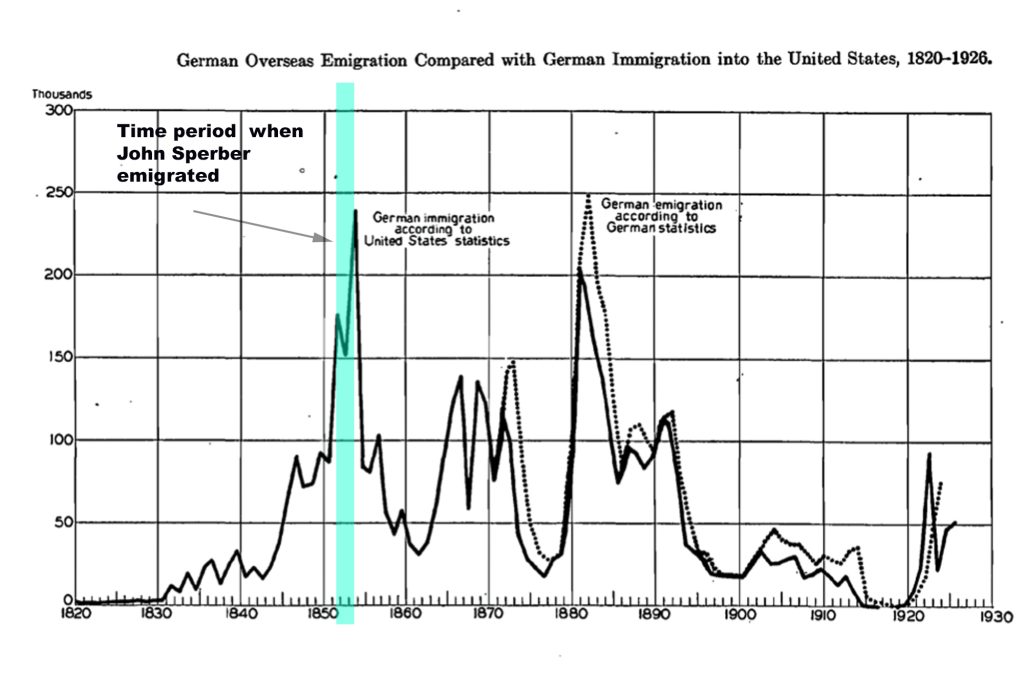

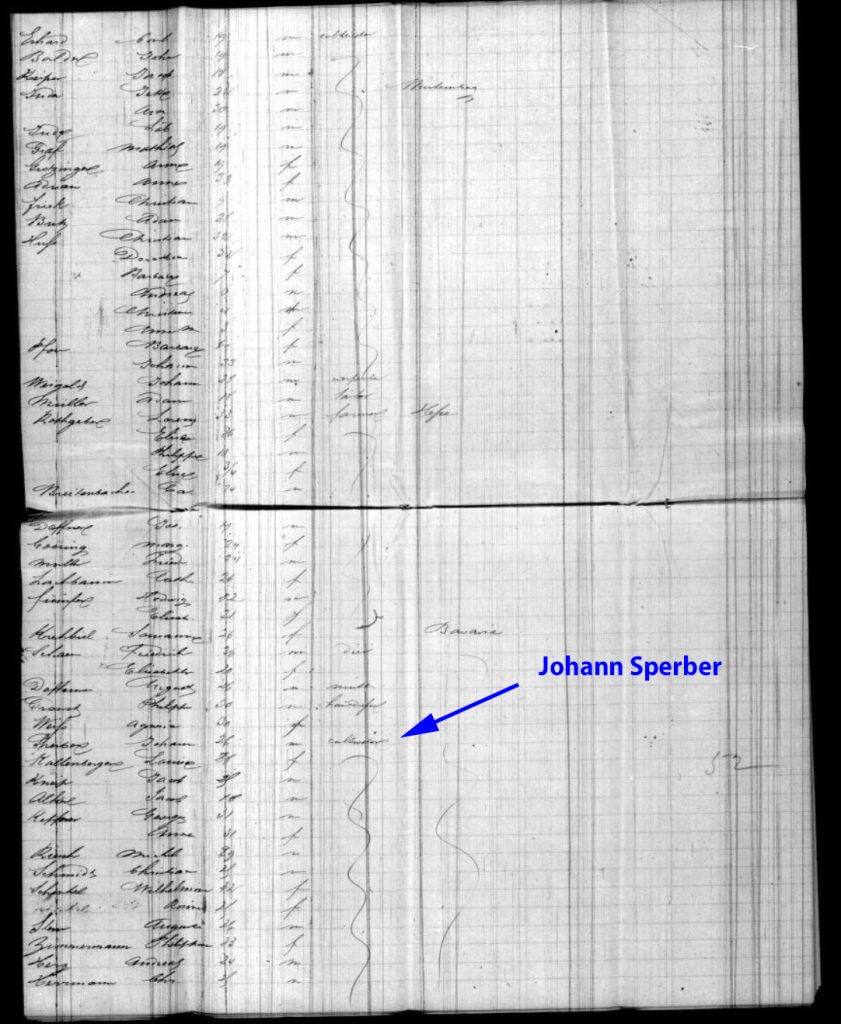

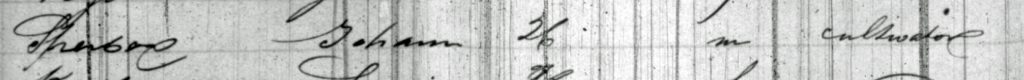

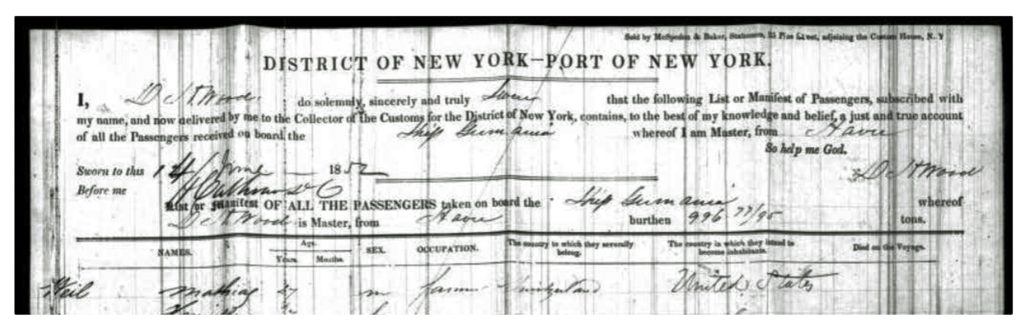

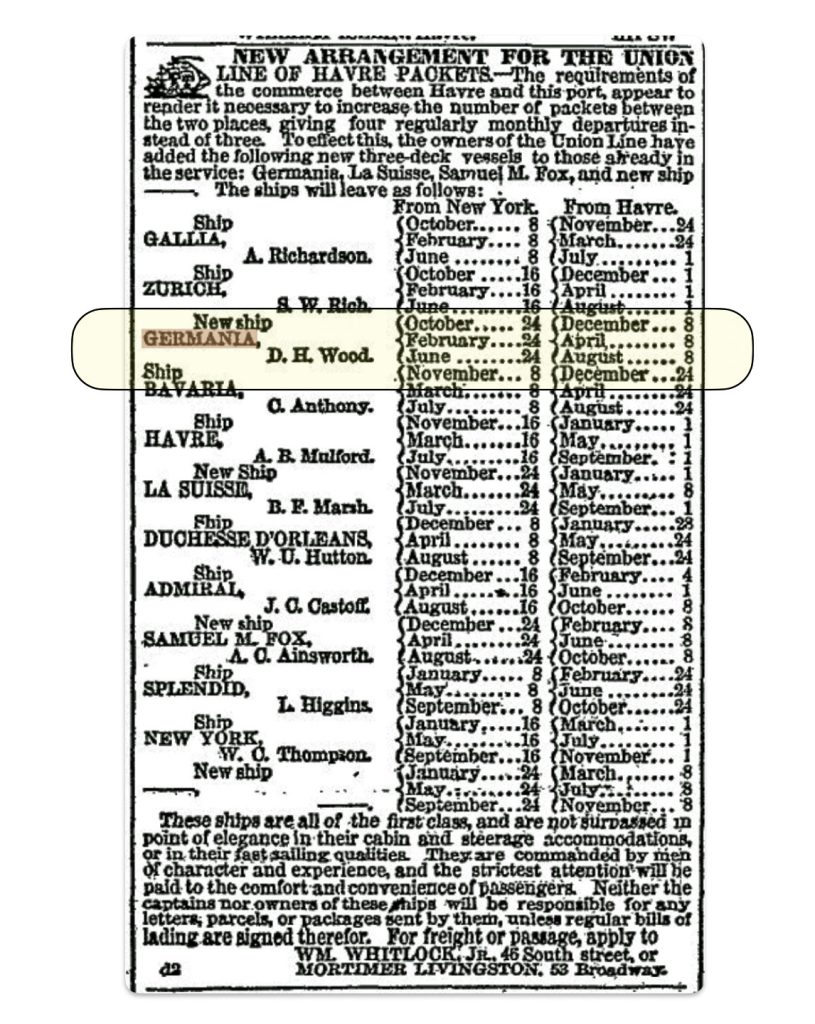

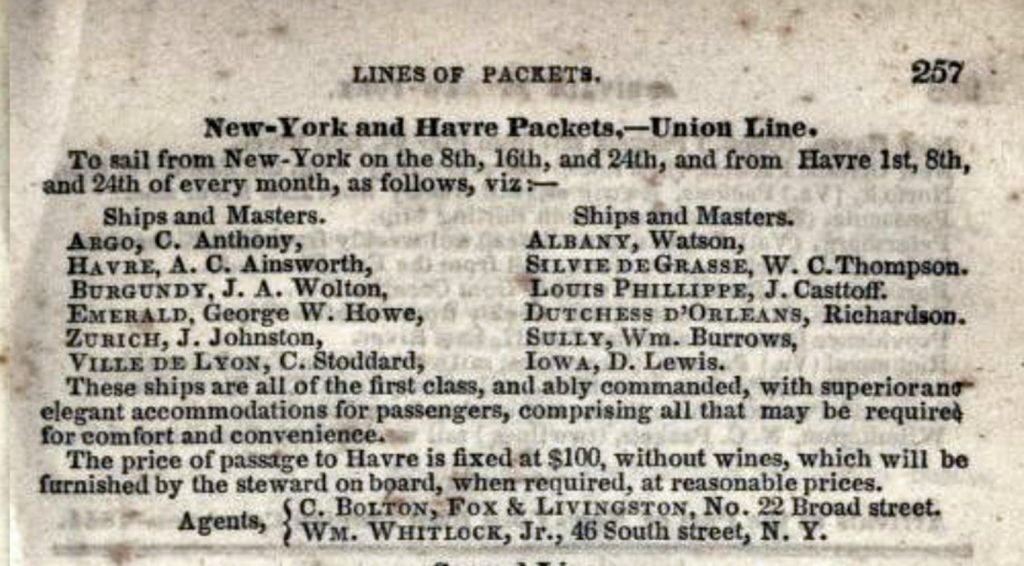

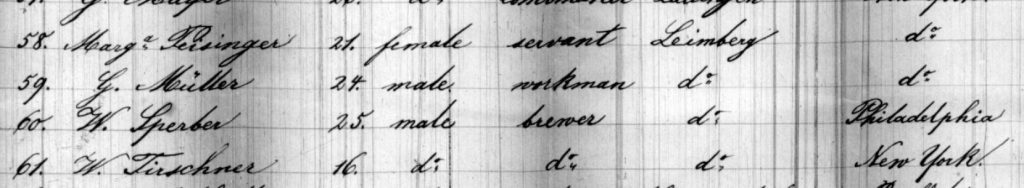

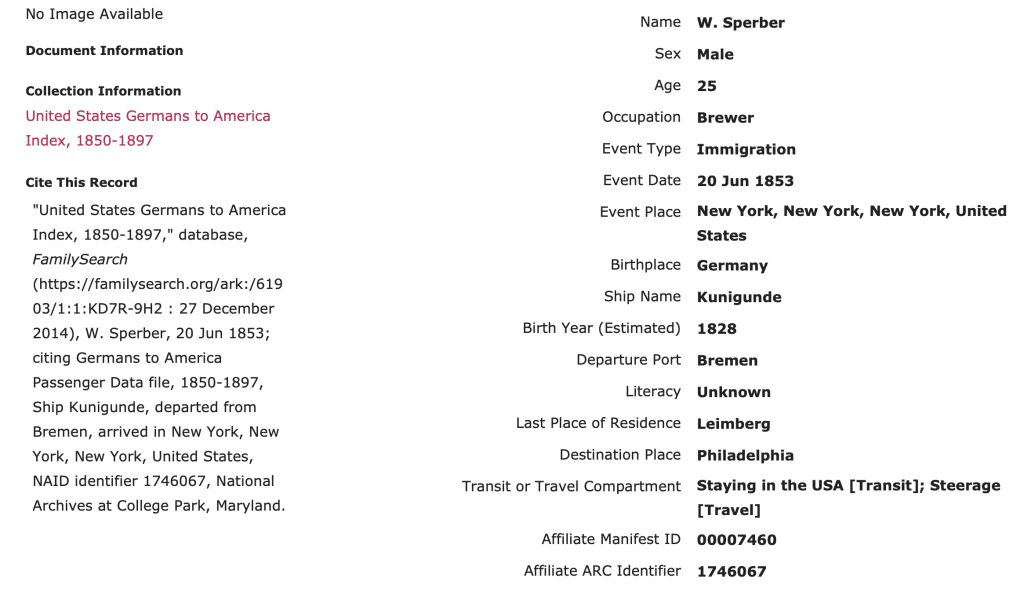

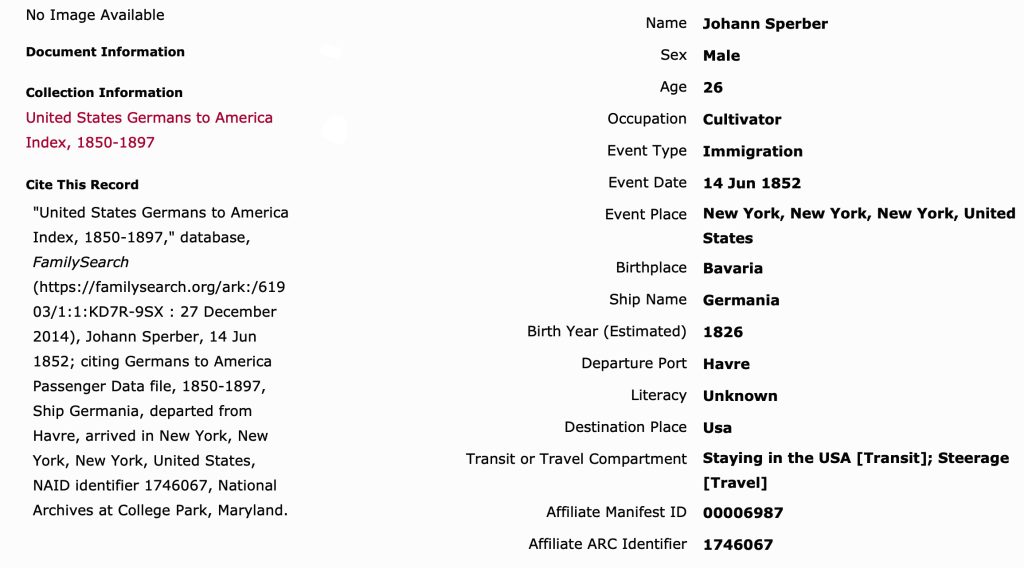

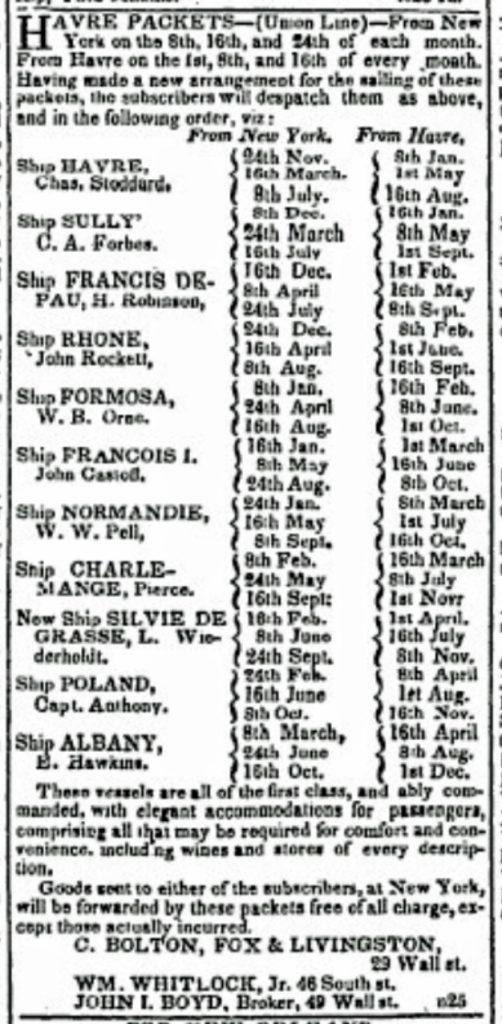

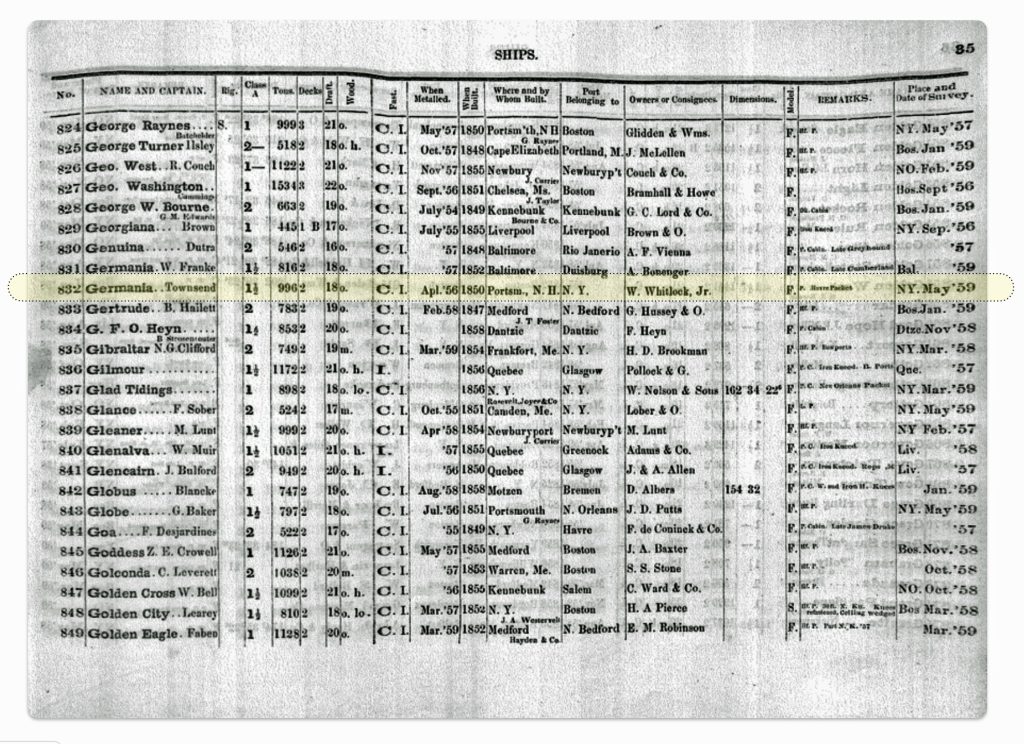

Based on the first part of this story, I have concluded that John Wolfgang Sperber arrived in New York City on June 14, 1852 on the ship “Germania” from the Le Havre Port in France.

Since I am not 100 percent confident of the evidence associated with his immigration to America, I have researched the other available inland European routes to major ports that he may have considered for his journey to move to America. My further research into the other possible routes that John Sperber may have taken for his journey to his new homeland gives me more confidence that he departed from Havre, France.

Based on my historical research on the transportation infrastructure in the mid 1800s in the German states and France, the following provides a narrative of John Sperber’s journey from the Grand Duchy of Baden to the port of Le Havre, France.

This story is part two of a five part story.

John Wolfgang Sperber: A Four Part Story

The first part of the story provides an overview of the family legacy John Sperber established in his new homeland, an historical background on where John was from in Baden, Germany, the influences on his migration to the United States, and the historical evidence of his departure and arival to America.

The second part of John Sperber’s story describes his journey from Baden-Baden to Le Havre based on historical evidence and historical accounts.

The third part of the story assesses the two other major inland pathways to European ports that John had options to consider. Since it is not absolutely certain that John sailed on the Germania from Le Havre, I have provided historical background on the relative accessibility of the three major routes John may have taken to make his voyage to the United States.

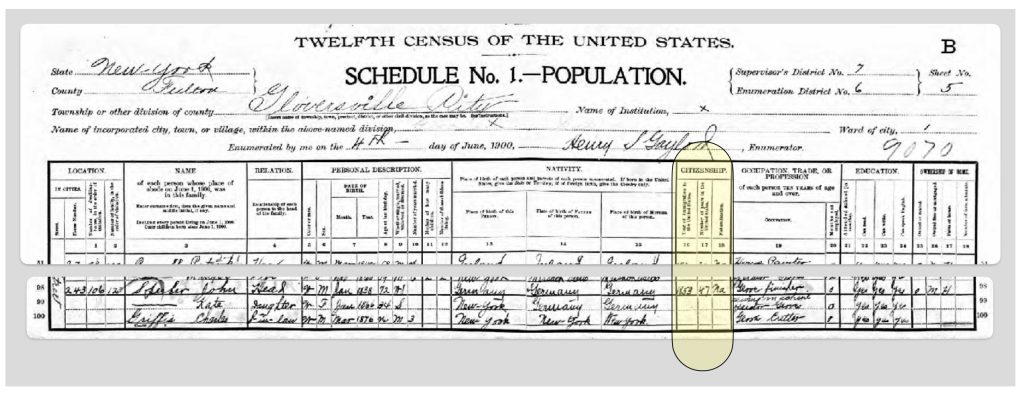

The fourth part of the story discusses the possible influences that drew Johann Sperber to Fulton County, New York.

The fifth part of the story discusses his travel to New York City and his options for travel up to the Mohawk Valley.

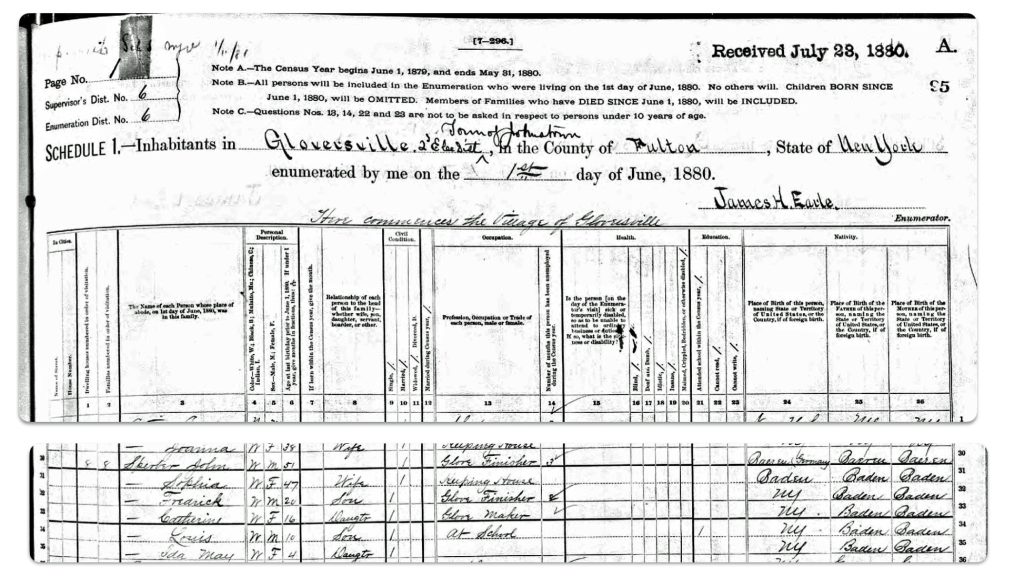

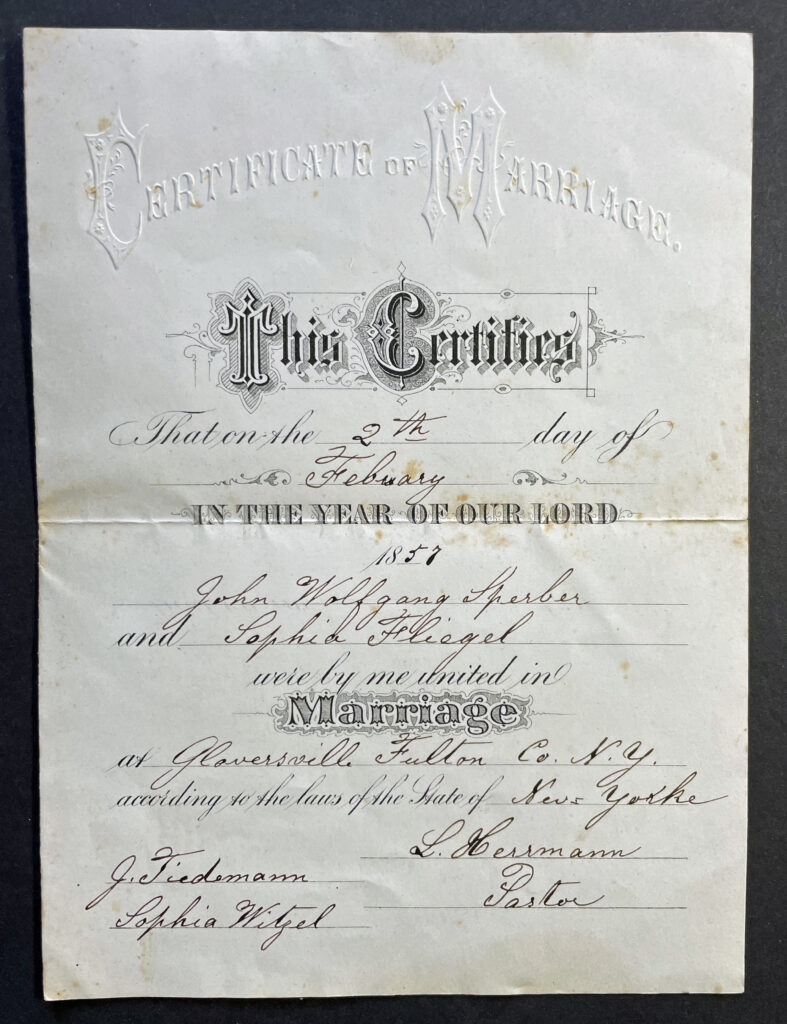

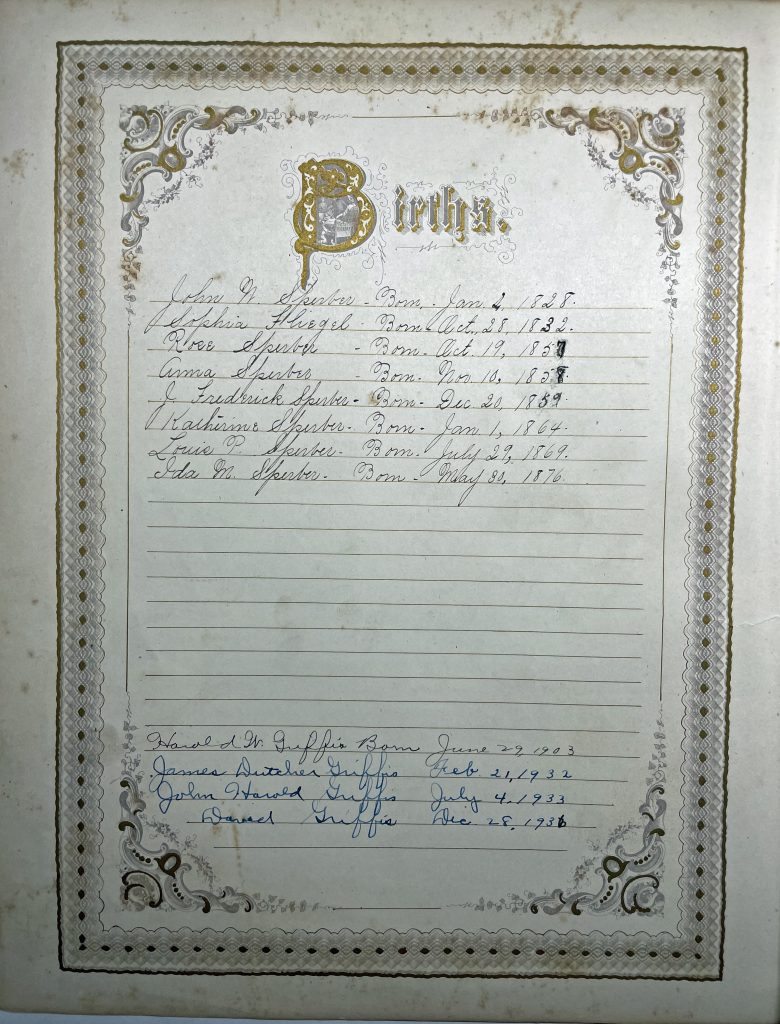

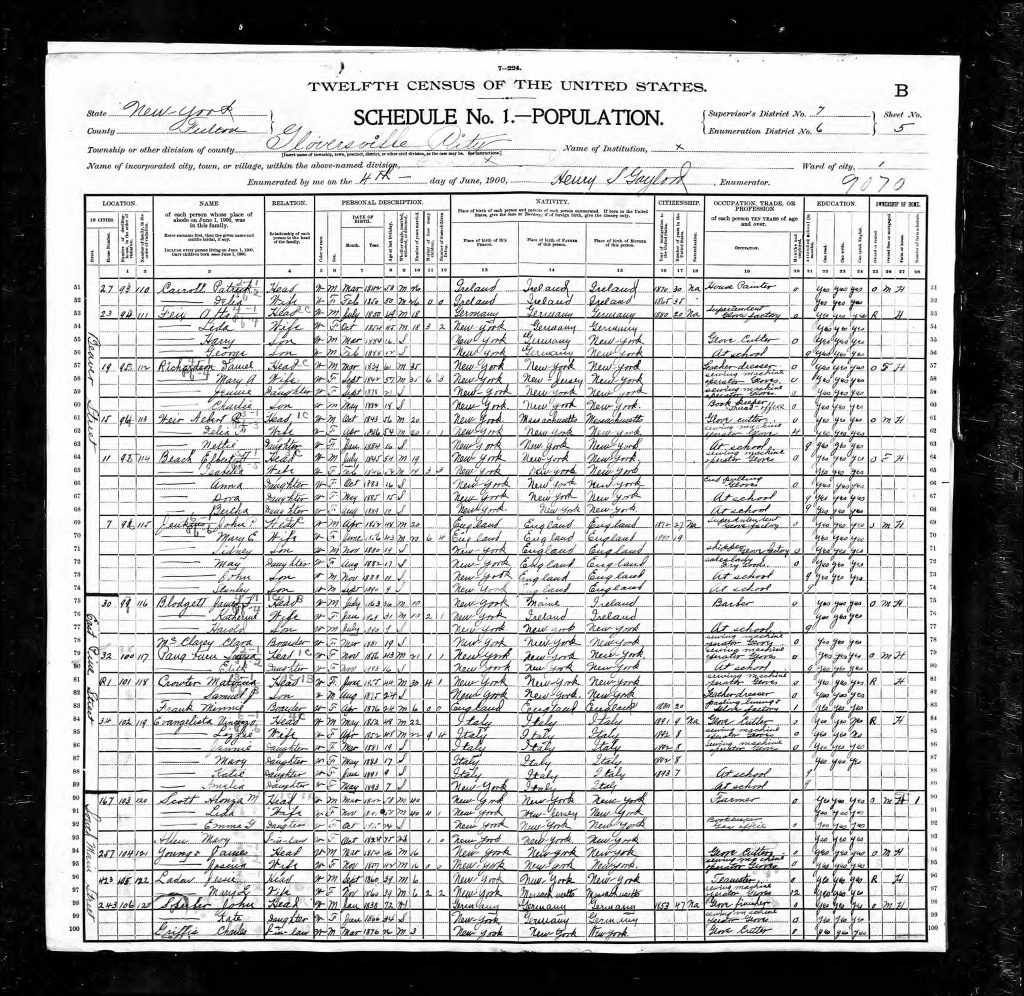

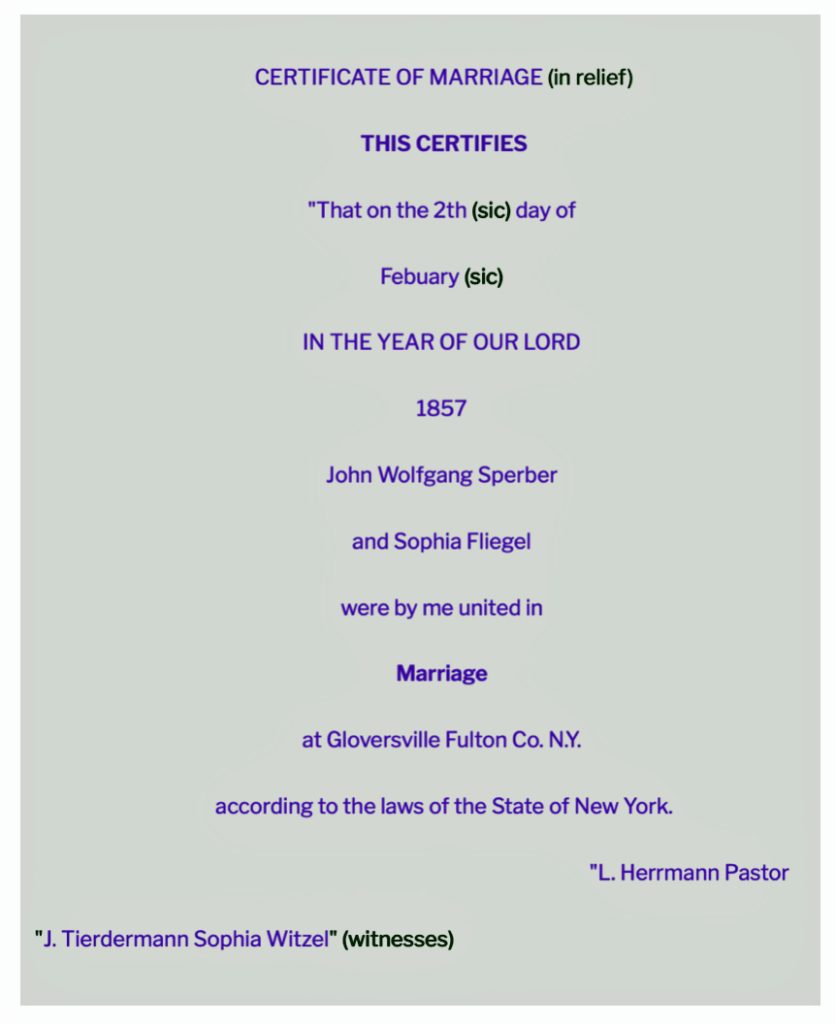

The sixth part of John Sperber’s story is about his establishing a new life and family in the Johnstown and Gloversville, New York area in the 1850s and 1860s.

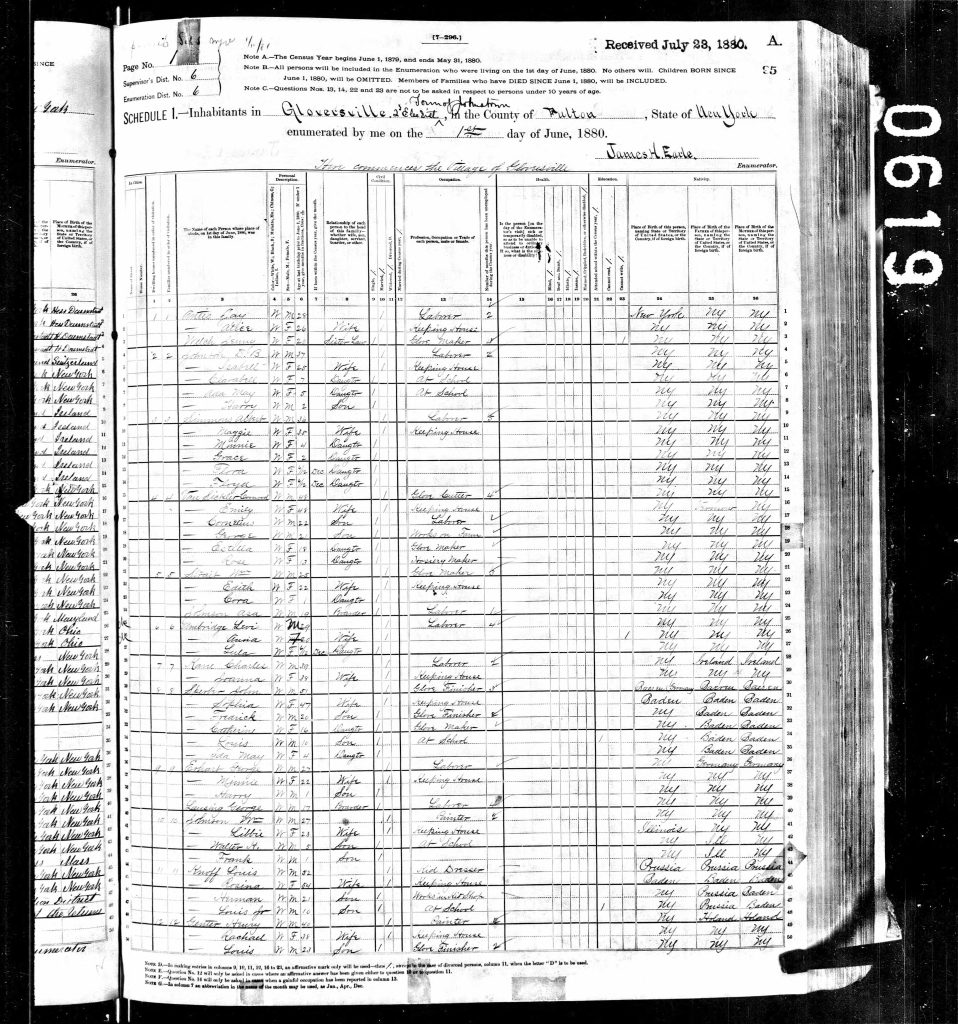

The seventh part of the story is about the John’s Family in the context of Gloversville’s development in the 1870s and 1880s and John’s career in the glove making industry.

The eighth part of the story is about the Sperber family in the 1890’s and the twilight of John’s life after the turn of the twentieth century

John Sperber’s Start of His Inland Journey to Strasbourg

Assuming John Sperber started his journey in the spring of 1852, he either utilized the established Baden Main Line train network or he used a carriage or wagon transport on Baden roads to get to Strasbourg, France. The distance between Baden-Baden and Strasbourg is roughly 57 kilometers or about 35 and a half miles.

“Advantageously located in Germany’s southwestern corner, Baden could not avoid a dual role in the nation’s railway affairs. First, of course, it oversaw the entry from Switzerland to the right bank of the Rhine and thus the most active north-south trade route in Europe. Second Baden’s proximity to France placed it at the railheads of both Strasbourg and Mulhouse, through which commerce was sure to pass from Paris and the French plains to Southern Germany.” [1]

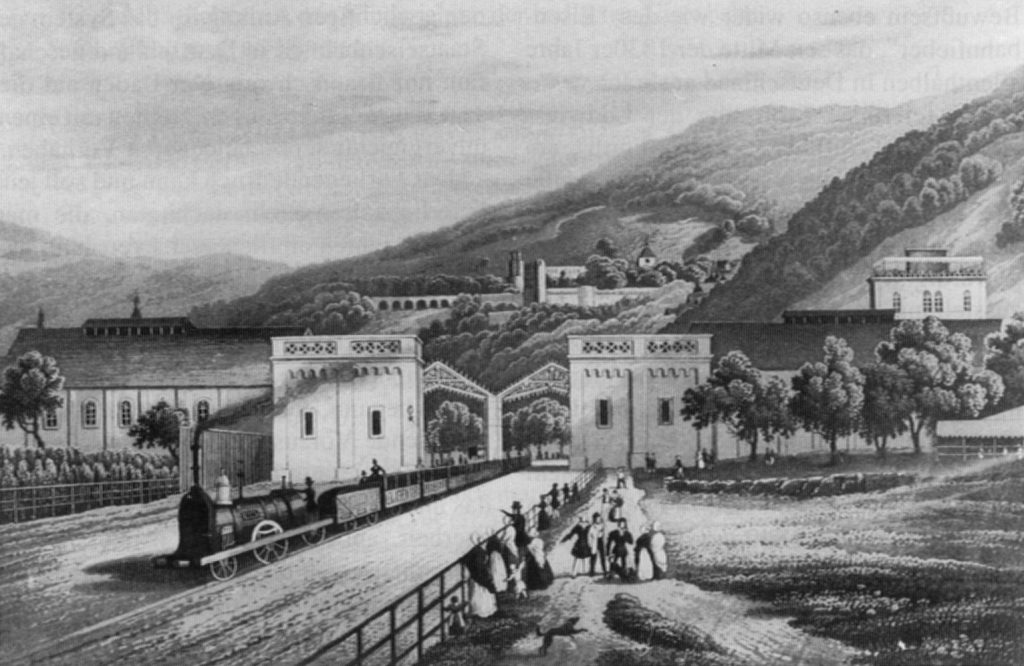

Train leaves the Station of Heidelberg in the Year 1840 [2]

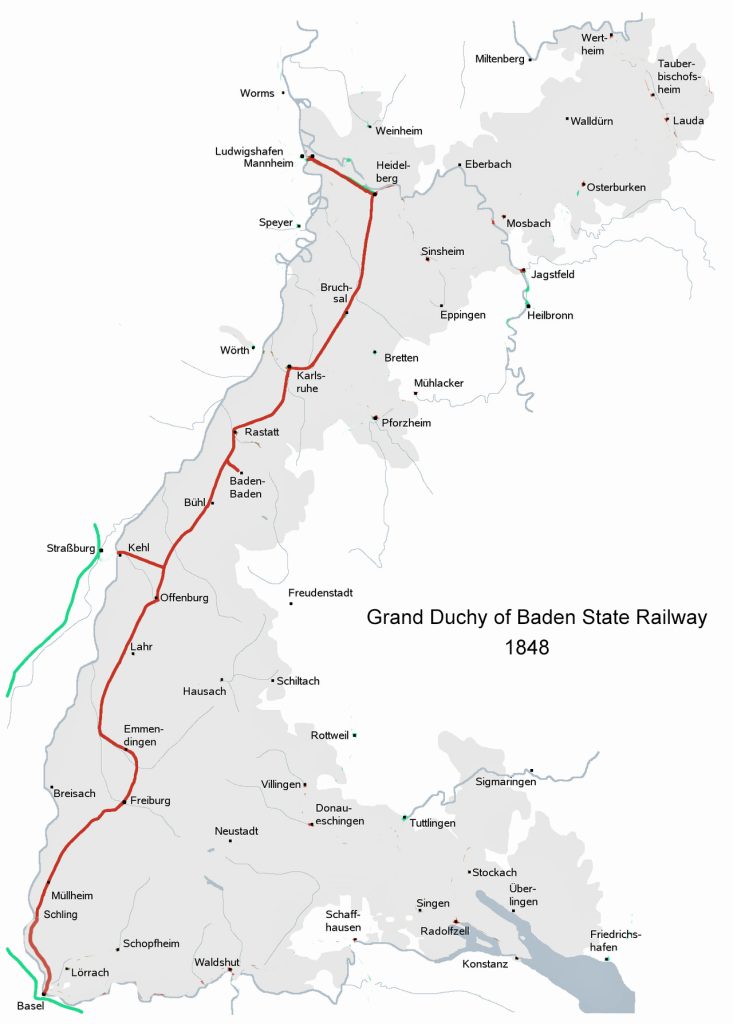

The Grand Duchy of Baden was the second German state after the Duchy of Brunswick to build and operate railways at state expense. Planning for the railway did not commence until the foundation of a railway company in the neighboring French province of Alsace for the construction of a line from Basle to Strasbourg in 1837. The Baden legislature passed three laws in one day to start plans (on March 29th, 1838) for the construction of the first route between Mannheim and the Swiss border at Basle, as well as a stub line to Baden-Baden and a branch to Strasbourg. [3]

Map One: The Grand Duchy of Baden Railway System 1848 [4]

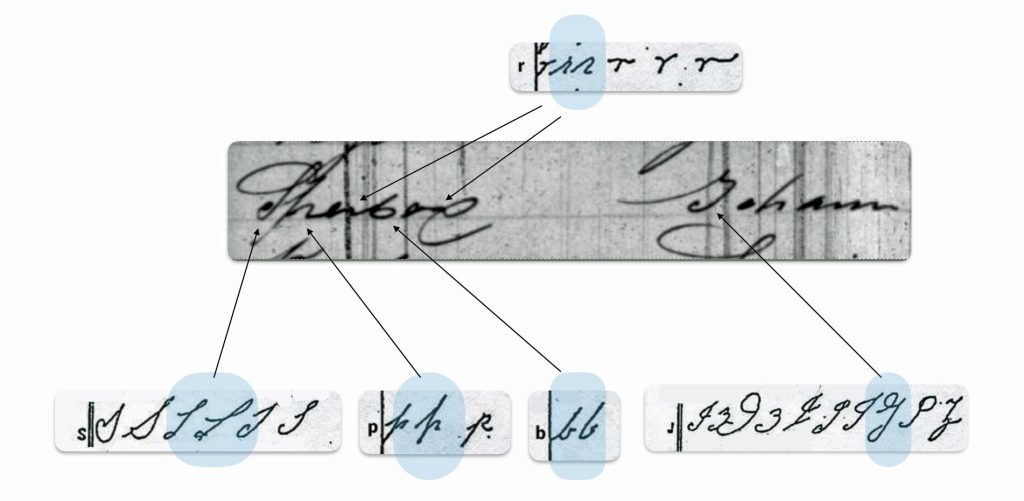

As indicated in map one above, based on the current state of the Grand Duchy of Baden Railway System in the early 1850’s, John Sperber could have taken the train from the extension of the rail line from Badin-Baden to Baden-0os. Baden-Oos was a stop on the main line. The train line headed south to the Kehl extension. The short branch line from Baden-Oos to Baden-Baden was opened on July, 27, 1845. Strasburg was across the border from Kehl on the Rhine River. [5] Since there was no railway bridge in 1852 over the Rhine from Kehl, John Sperber probably took a boat across the Rhine to reach Strasbourg. [6]

Another option for John Sperber was to travel by road to Kehl and then by boat across the Rhine River to Strasbourg.

The Legacy and Impact of French Postal Roads and German Immigration

From Strasbourg, John Sperber had a few but limited options based on what he could afford for inland travel and the configuration of the current transportation infrastructure in 1852. Since he was a young man traveling alone, I imagine he was more concerned with economy of travel, safety and dependability; and not necessarily concerned with speed and comfort of travel. John could have utilized a combination of travel approaches to Le Havre from Strasbourg. The approximate distance between Strasbourg and Le Havre is 610 kilometers (about 379 miles) when traveling by road.

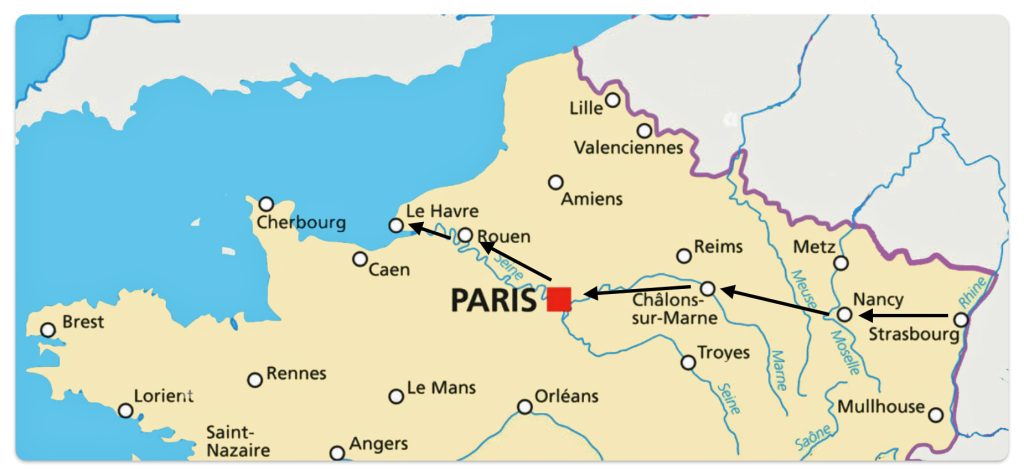

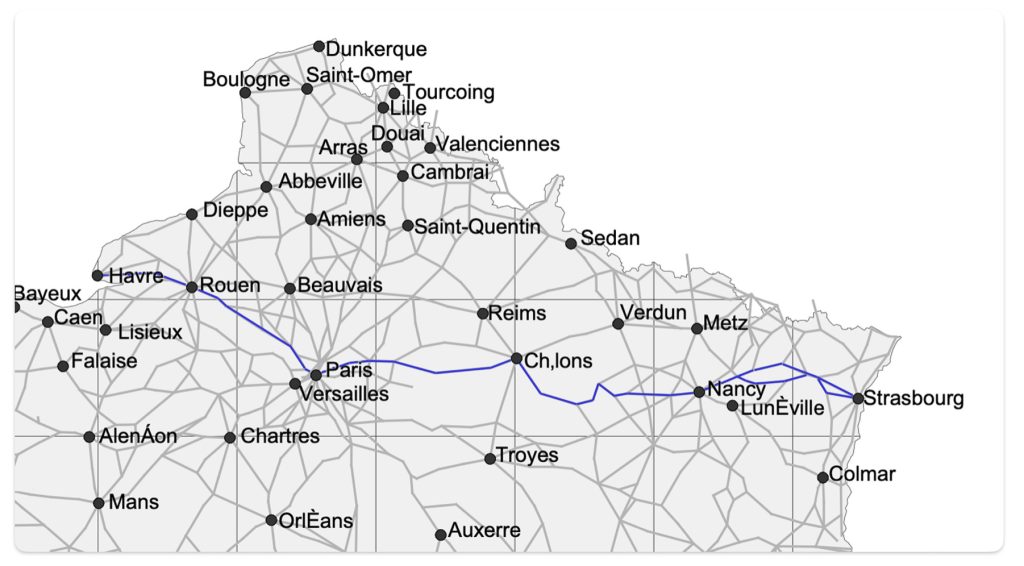

As reflected in map two below, his journey to the port of Le Havre could be viewed in terms of the major towns or cities that he had to travel through based on existing roadways, railways and waterways. The journey could be viewed in terms of five segments: Strasbourg to Nancy, Nancy to Châlons-sur-Marne [7], Châlons-sur-Marne to Paris, Paris to Rouen, and Rouen to Havre.

Map Two: The Basic Route from Strasbourg to Havre

In terms of distance, table one provides approximate distances for each of the five segments of John Sperber’s inland journey.

Table One: Approximate Distances for Each Segment of Sperber’s Inland Journey

| Segment | Kilometers | Miles |

|---|---|---|

| Strasbourg – Nancy | 160 | 100 |

| Nancy – Châlons-sur-Marne | 137 | 85 |

| Châlons-sur-Marne – Paris | 187 | 116 |

| Paris – Rouen | 135 | 84 |

| Rouen – Havre | 90 | 60 |

| Total Strasbourg – Havre* | 700 | 435 |

The journey between each of these segments in northern France contains a diverse terrain of mountains, plains, and rolling hills. Map three provides an overall representation of the topography of John Sperber’s journey across France. The roughly 700 kilometer journey was not on flat terrain.

Map Three: Topographical Map of Northern France [8]

If we look closer at each segment of his journey using maps of the current roads in France, it is readily apparent that the roads contain noticeable gradients in ‘hilly’ areas. An argument could be made that using contemporary maps to describe possible roadways that John Sperber used for his journey might be misleading since roads certainly have changed since 1852. While it is true that many of the French roads have changed in terms of their surface and infrastructure and they have been improved and rebuilt, many of the major contemporary road arteries in France follow the routes of royal postal roads that were originally built in the 1700s.

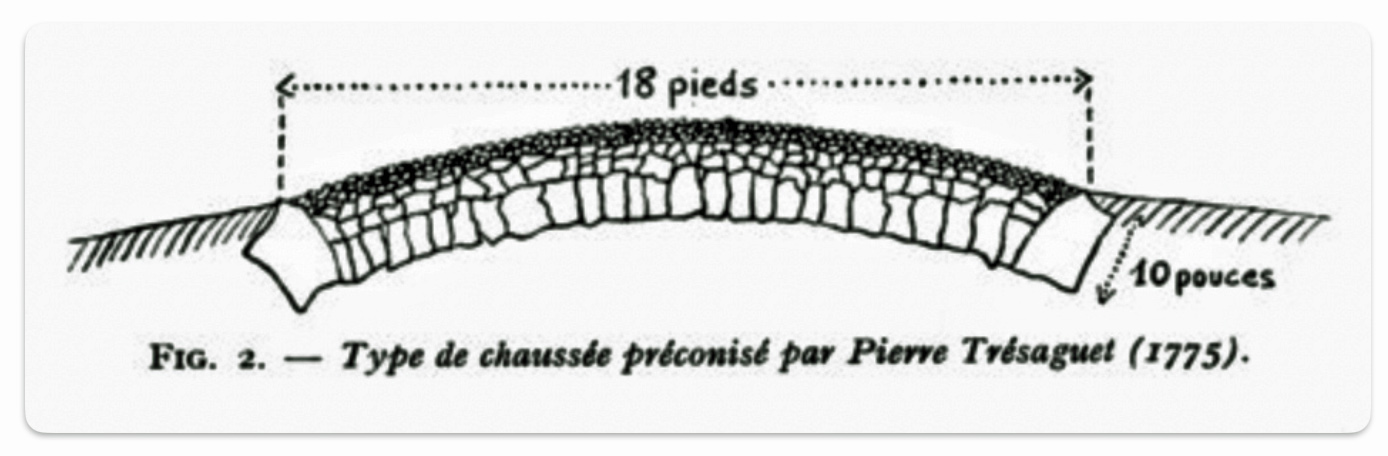

The French postal roads of the 1700s were innovative in their design and construction. The engineers replaced the old zigzagging roads by redesigning straight lined roads which reduced travelling time, made the roads safer, and technically easier to maintain. Roadways through mountainous areas were constructed to minimize the gradients of the road. Where it is was possible many of the mountainous or hilly areas were constructed with the goal of having seven percent gradients. The network of many of these roads created by the monarchy remained untouched by the following regimes and still represent the blueprint of the French road system in the twenty-first century. [9]

“Straightening or even completely neglecting the windings of ancient roads and seeking, thereby, to rediscover the straightness of Roman roads, the engineers of the 18th century always chose the shortest traces as far as possible. … But the route most often avoided villages, or even certain small towns which would have forced it to make an unnecessary detour. A junction is then sufficient to serve them. In the mountains on the other hand, while trying to maintain long rectilinear sections, we looked for traces adapted to the requirements of the relief in such a way that the ramps could only very exceptionally exceed 5 inches per toise (i.e. approximately 7%). “ [10]

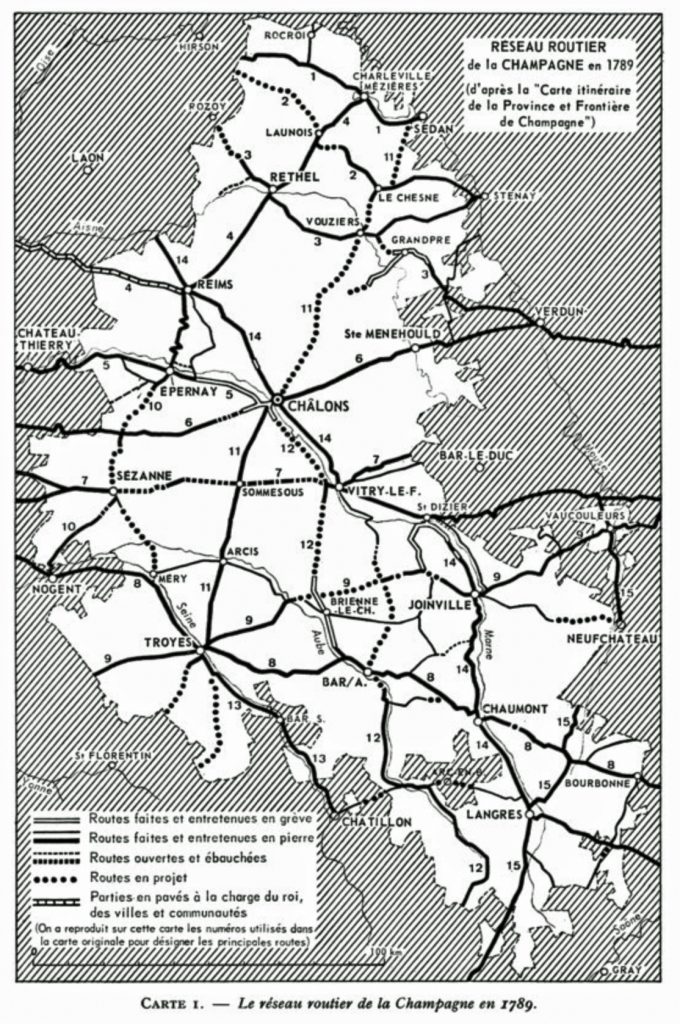

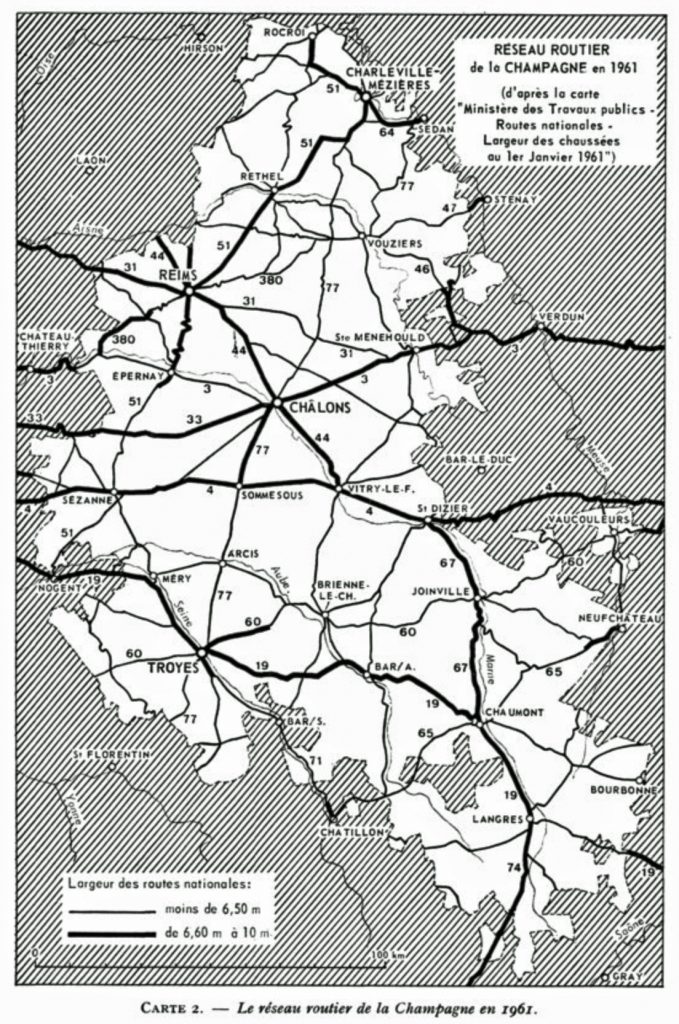

For example, one of the major towns John Sperber probably traveled near or through was Châlons-sur-Marne which was a viticultural area that has a long history of producing grapes for champaign production. [11] Châlons-sur-Marne was also one of the major towns that were roadway hubs that were originally part of the legacy of French Postal Roads that were established in the 1700’s and fanned out from Paris.

The French Postal Roads and the “Corps des Ponts et Chaussées”

The creation of the French royal postal routes was a gradual process that evolved over several centuries, with significant contributions from various monarchs and the influence of existing postal systems.

Under Louis XIV, who reigned from 1643 to 1715, centralization increased, and the king sought to exercise greater control over the postal service for political and financial reasons. In 1672, he created the Ferme générale des Postes (General postal farm), which marked the beginning of taxation on postal services.

The origin of the department of Bridges and Roads in eighteenth century France, known as the “Corps des Ponts et Chaussées,” can be traced back to the early eighteenth century. This department was formally organized in 1716 during the reign of Louis XIV. The establishment of this department marked a significant development in the administration and construction of road and bridge infrastructure in France.

The Corps des Ponts et Chaussées was responsible for overseeing the construction and maintenance of roads and bridges across the country. This organization played a crucial role in the systematic development of transportation infrastructure, which was essential for economic and military purposes. The creation of this department was part of a broader movement towards rationalizing and centralizing the administration of public works in France, reflecting the state’s increasing involvement in economic development and infrastructure management during this period.

The department’s establishment was influenced by the need to improve the existing road systems, which were inadequate for the demands of the time, particularly due to the growth in commerce and the mobility needs of the military. The Corps des Ponts et Chaussées not only handled the technical aspects of construction but also engaged in the planning and regulatory oversight necessary to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of transportation networks across France. [12]

Looking at maps four and five of the major roadways surrounding Châlons-sur-Marne underscore the similarity of major French roadways over time. [13]

Maps Four and Five: Example of Major French Roads in the Châlons-sur-Marne Area in the 1789 and the 1961

Road network of Champagne in 1789 (according to “Itinerary map of the Province and Border of Champagne”)

Legend:

– Roads made and maintained on strike

– Roads made and maintained in stone

– Projected roads

– Cobblestone parts at the expense of the king, towns and communities

(The numbers used in the original map to designate the main roads have been reproduced on this page)

Champagne road network in 1961 (according to the map “Ministry of Public Works – National Roads – Width of roads as of January 1, 1961”)

Legend:

Width of national roads: ‘6.50 m hand ‘ and ‘ from 6.60 m to 10 m’

Many of the these postal routes survived and became the major roadways in France. In fact, all of the roadways along the route from Strasbourg to Le Havre are part of the old postal route system.

Map six below depicts the postal roads in northern France that linked major towns and cities in France in 1833. The creation of the map is the result of analyzing the changes over time of the expansion of postal routes in France through time. I have highlighted the postal roads that followed the possible route that John Sperber had taken to reach the post of Le Havre.

“Although the mounted mail made increasing use of the paved or cobblestone roads built by the engineers of the department of Bridges and Roads in the 18th century, it was the aggregate of relay stations and not the sections of roadway that were managed by the institution, since the itinerary that connected one nucleus to another could change over time. But this fluidity is also a characteristic of the stations themselves, … between 1632 and 1850, less than half of the relay stations remained the same. In this sense, the impression of permanence and longevity gives way to the notion of change and chance. ” [14]

Map Six: French Postal Roads and Main Cities and Towns in 1833 and the Highlighted Possible Route of John Sperber from Strasbourg to Le Havre [15]

“The evolution of the mapping of the postal network sheds light on various territorial choices stemming from political or economic requirements. This postal network was the first exchange system managed by the French monarchy within the boundaries of the territory of France. With the Edict of Luxies in 1464, Louis XI created relais de poste (roadhouse postal offices) and divided the horseback couriers of the king’s stables into two groups: the courriers du cabinet, who were in charge of royal mail, and the postes assises, who later would become post masters, in charge of providing the horses. Depending on the roads, terrain, and topographical demands, the offices were between four and five leagues apart (16 to 20 kilometers). The network was made available to travelers in 1506 during the reign of Louis XII. Under Louis XIV, king of France in 1643-1715, centralization increased and the king sought to exercise greater control over the postal service for political and financial reasons. In 1672 he created the Ferme Générale des Postes (General postal farm). The speed of the postal service was about seven kilometers per hour at the beginning of the 18th century. The relais de poste were done away with in 1873.”[16]

The Geographical Terrain Across Northern France

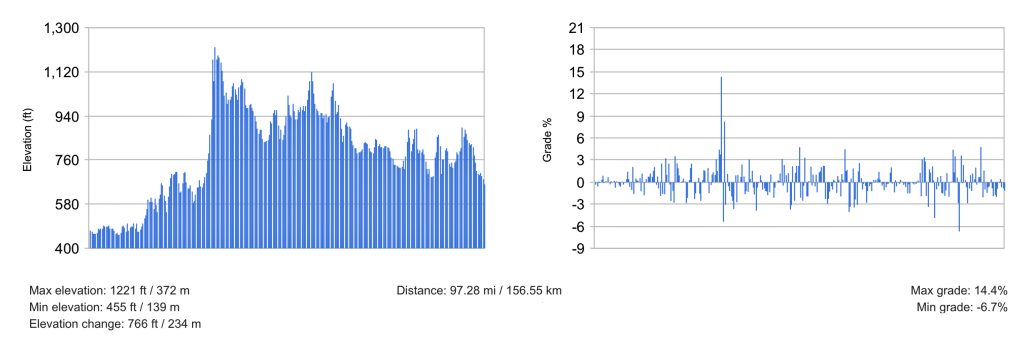

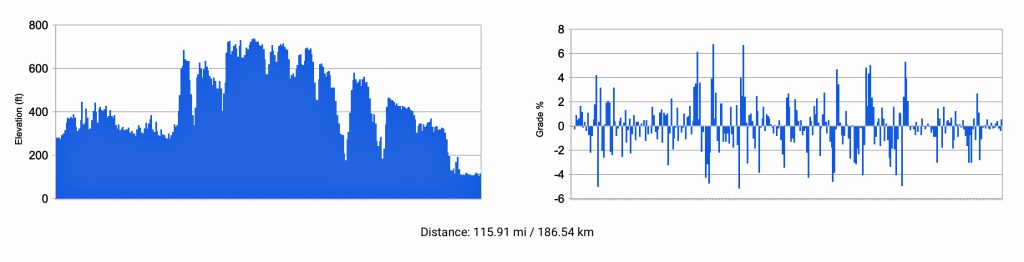

The initial segment of travel between Strasbourg and Nancy contains steep terrain, as evidenced in the elevation graphs associated with map seven below. None of the approximate 100 miles is flat.

The area between Strasbourg and Nancy is characterized by a diverse geographical landscape that includes the upper ridge of the Vosges Mountains and the plains of Alsace and Lorraine. Strasbourg is part of the Alsace region. This area is known for its flat plains which are conducive to agriculture and viticulture. Some of the gradients on the road, as reflected in the graphs, are above 14 percent. [17]

Map Seven with Graphs: Elevation and contemporary Roadway Gradients between Strasbourg and Nancy

Nancy, on the other hand, is situated on the left bank of the Meurthe River, approximately 10 kilometers upstream from its confluence with the Moselle River. The city is surrounded by hills that are about 150 meters higher than the city center, which itself is situated at 200 meters above sea level. The geography around Nancy includes these elevated areas, providing a contrast to the flatter regions closer to Strasbourg.

The Vosges Mountains, which lie to the west of this corridor, are a significant geographical feature. They create a natural barrier and have historically been a strategic region in defining political boundaries. The mountains slope down into the foothills and then transition into the plains of Alsace to the east and Lorraine to the west, which are more conducive to human settlement and agriculture.

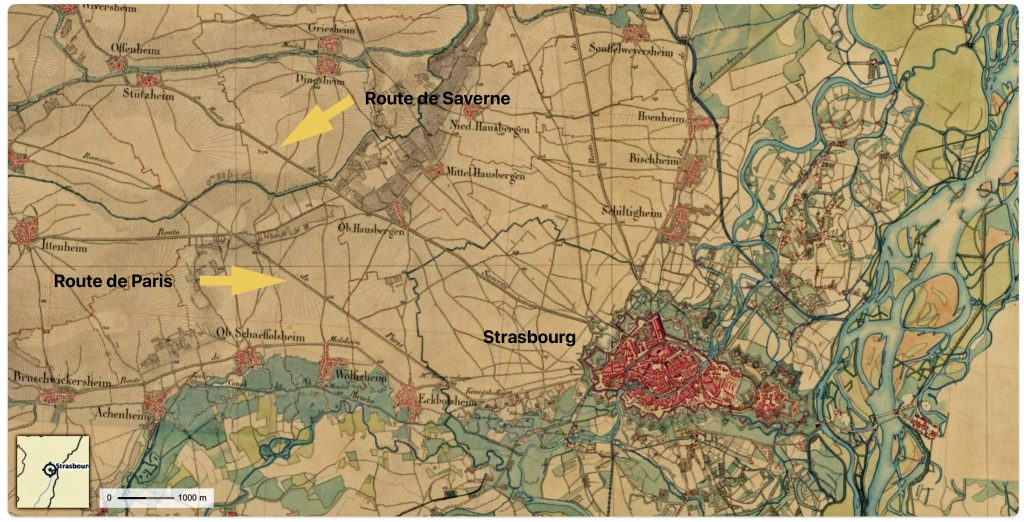

As reflected in map two below, there were two established postal roadways leading out of Strasbourg to Paris.

Map Eight: Section of the Carte D’ETAT-MAJOR 1820-1866 of Strasbourg [18]

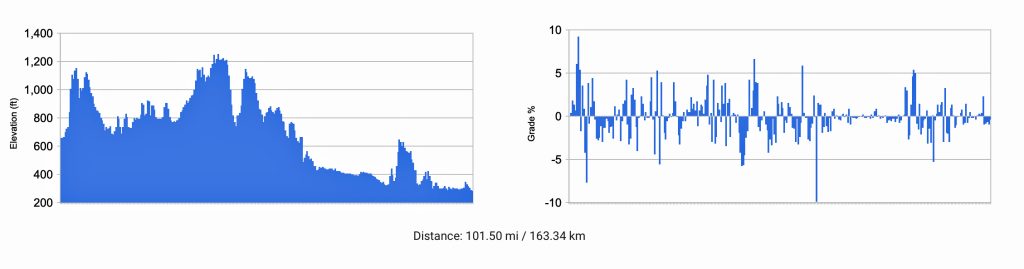

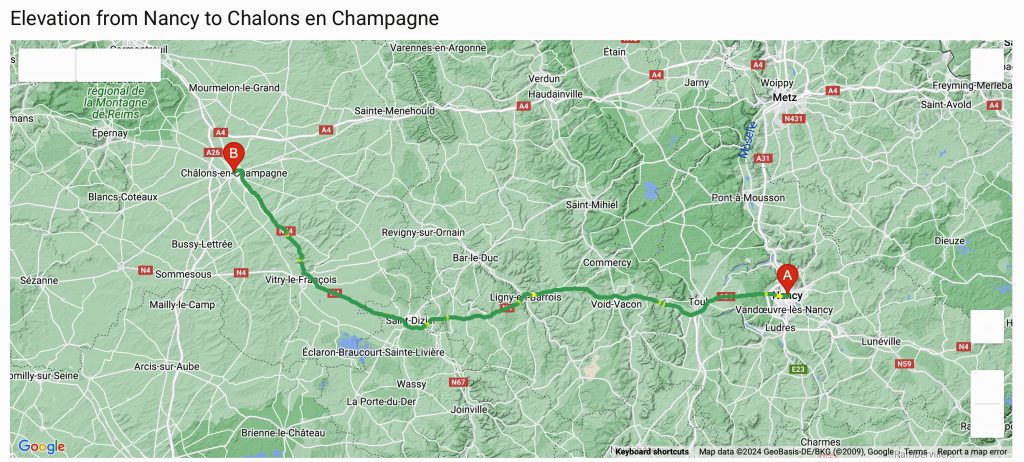

John’s 85 mile journey from Nancy to Châlons-sur-Marne contained undulating terrain with average gradients between two to five percent on the hills. Some of the climbs hit 9 percent and seven percent. Châlons-sur-Marne, now known as Châlons-en-Champagne, is situated in the Champagne region, and is known for its rolling plains and large agricultural areas, especially vineyards. The Marne river flows through this region. The distance between Nancy and Châlons-sur-Marne is approximately 150 kilometers (about 93 miles), and the terrain between these two cities includes a mix of river valleys, agricultural land, and forested areas. The route would have traversed the regions of Lorraine and Champagne, with their respective geographical characteristics.

Map Nine with Graphs: Elevation and Contemporary Roadway Gradients between Nancy and Châlons-sur-Marne

In the 1800s, the terrain between Châlons-sur-Marne (now known as Châlons-en-Champagne) and Paris was characterized by a mix of agricultural landscapes, forests, and small villages. This region is predominantly flat with gently rolling plains.

Traveling towards Paris, the landscape would transition from the open plains of Champagne to the more hillier, wooded and forested areas surrounding Paris. Historical accounts and maps from the era often depict this region as less densely populated than today, with numerous small villages dotting the landscape. These villages would typically center around a church or a market square, serving as community hubs for the surrounding rural areas.

The road networks in the 19th century, while improved from medieval times, were still developing. Prior to the development of railways in the late 1840s and 1850s, major routes like the one from Châlons-sur-Marne to Paris was vital for the transport of goods and people.

The roads between Châlons-sur-Marne and Paris had a number of areas where there were sharp steep climbs and descents. Some of the gradient changes were above 5 percent..

Map Ten with Graphs: and Contemporary Roadway Gradients between Châlons-sur-Marne and Paris

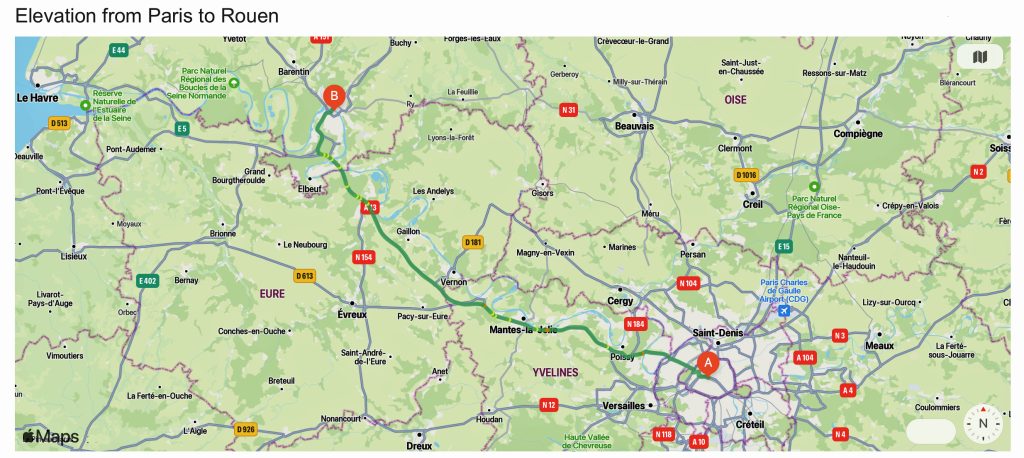

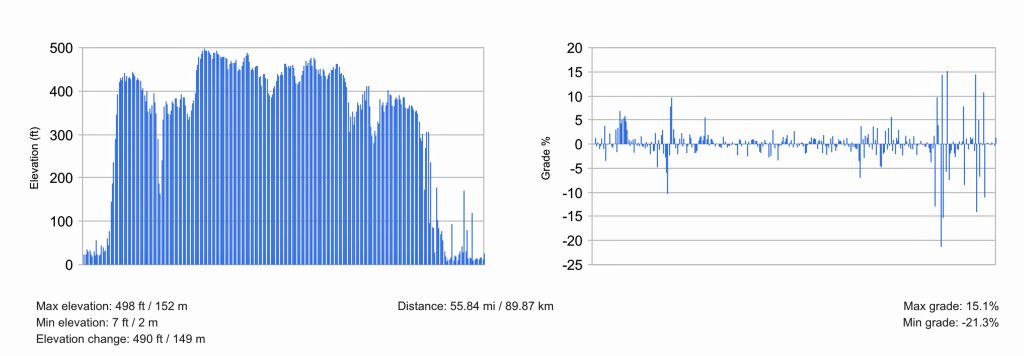

The journey from Paris to Rouen moves through a part of the Paris Basin, which is a geological lowland area. See map ten. The terrain has rolling, hills following the winding Seine River. When approaching Rouen, there are some steep gradients and hills that reach 14 or more percent.

“The main road along the Seine from LeHavre through Rouen to Paris was the Route Royale 14. From Rouen to Paris, where it was called the route d’en haut (the less-used Route Royal 13 was called the route d’en bas), it had existed for some time, though like most roads, in rudimentary form until early in the eighteenth century.” [19]

“Even good roads required considerable effort and expense to maintain their viability. The soil and climate along much of the route made maintenance difficult. The effects of rain could be very destructive on the chaulky Normandy plateaux where good foundations and drainage were not easily obtained. With any more than a thin layer of mud, ruts began to form, and the going became very heavy.” [20]

Map Eleven with Graphs: and Contemporary Roadway Gradients between Paris and Rouen

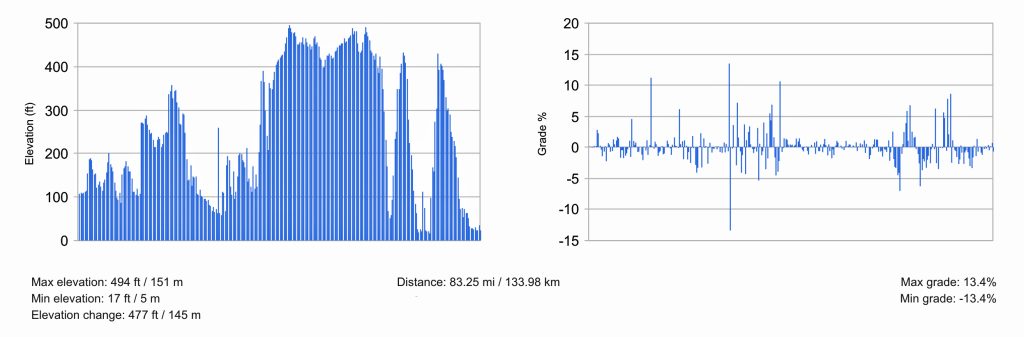

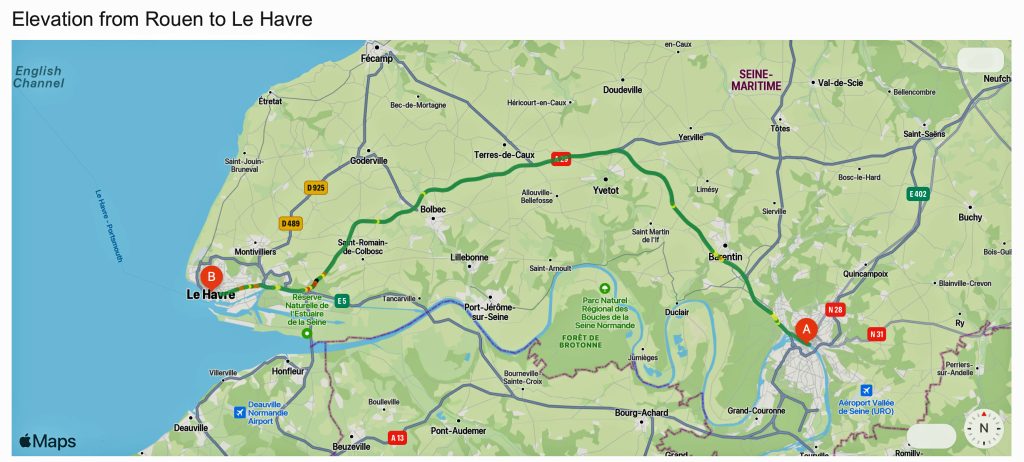

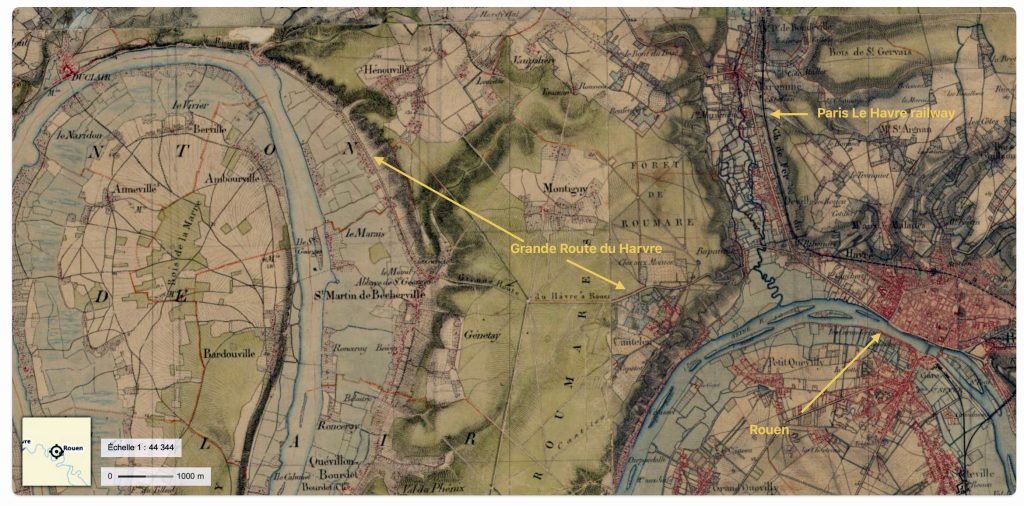

While the roadway terrain between Rouen and Le Havre in the 1850s would have been quite different from what modern travelers experience today, it essentially following the old Fench postal routes. During the mid-19th century, the region of Normandy, where both Rouen and Le Havre are located, was characterized by a variety of landscapes, including dramatic coastlines with chalky cliffs in the eastern part, and wide stretches of sand and pebble beaches to the west. The inland terrain was largely an open plateau with gentle hills, suited for agriculture, including small fields, orchards, and pastures.

The road network in France during the 18th and 19th centuries was undergoing significant changes, with the expansion of postal routes and the improvement of road conditions. By the 1850s, the economic situation had impacted the maintenance of the road network, but main routes, such as the one between Rouen and Le Havre, were likely to have been kept in better condition to facilitate trade and travel. [21]

In the 1850s, the main mode of transportation between Rouen and Le Havre was horse-drawn vehicles such as utility wagons, carriage and stagecoaches, on roads. This period predates the establishment of the tramway system in Le Havre, which began in 1874 [22]. The widespread use of steam-powered river transport, which started to be effectively applied in 1826, was initially limited to tugboats operating between Le Havre and Rouen. [23]

Map ten below is a portion of an original French map that shows Rouen in context of the major route to Havre as well as the Paris Le Havre railway. [24]

Map Twelve: Section of the Carte D’ETAT-MAJOR 1820-1866 of Rouen Showing the Railway and Major Roadway to Havre

Travel between the two cities would have typically been by horse-drawn vehicles on roads that followed the sinewed curves of the Seine River. The roads would have varied, with some sections possibly paved with cobblestones or similar materials, while others might have been simple dirt road that could become muddy and difficult to traverse in bad weather.

Map Thirteen with Graphs: and Contemporary Roadway Gradients between Rouen and Le Havre

Traveling Optons Across Northern France

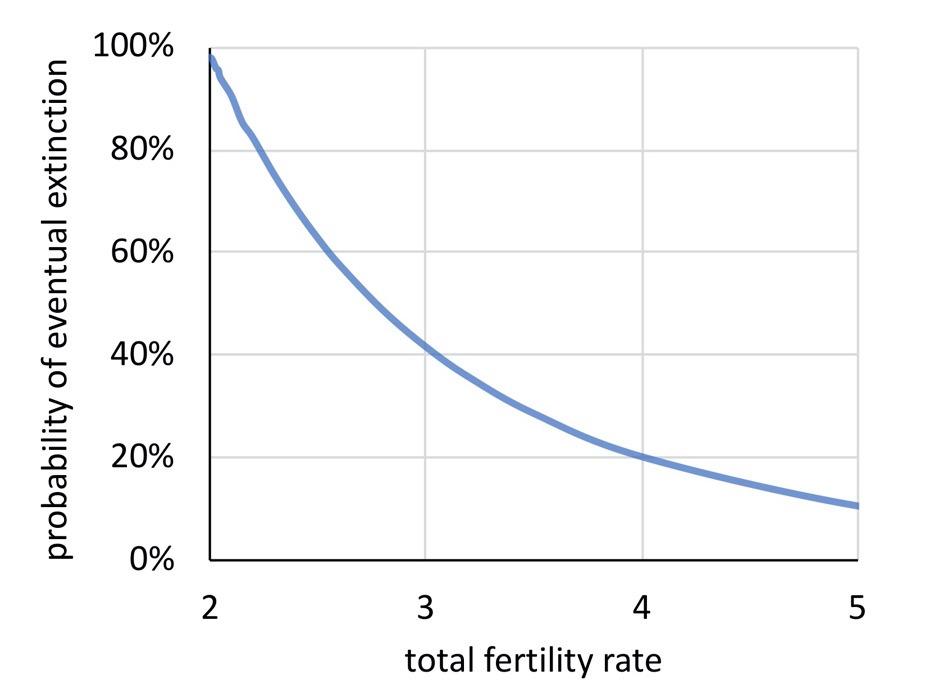

It is highly likely John Sperber, a young single male, traveled through France by French roadways. This option would have been the slowest and perhaps least expensive way, not withstanding the added costs of food and quarters along the way, to get to the port of Le Havre.

It is possible John Sperber used a combination of road and railway travel. The railway system in France in the early 1850s was growing but not complete across northern France. In 1852, completed sections of railway systems were increasingly available as John made his way west across France. The use of waterways via rivers was an available option once he arrived in Paris; and he could have considered traveling on barges up the Seine to Le Havre.

Table Two: Travel Options Traveling from Strasbourg to Le Havre in 1852

| Travel Segment | Road | Railway | Waterway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strasbourg to Nancy | Available | – – – | – – – |

| Nancy to Châlons-sur-Marne | Available | – – – | – – – |

| Châlons-sur-Marne to Paris | Available | Available | – – – |

| Paris to Rouen | Available | Available | Available |

| Rouen to Le Havre | Available | Available | Available |

Specifically, John Sperber had the following options or combination of options to reach the port of Le Havre for his voyage to the United States:

- French Roadways: As indicated, the roadways of France provided a fairly direct route from Strasbourg to Le Havre. It was the predominate mode of travel for German immigrants traveling to the port of Le Havre. While the slowest means of travel. John possibly hitched a ride with another immigrant family who were traveling on their farm wagon and horse team. He could have paid to ride on one of the returning commercial wagons that were returning to Havre. He also had the option to utilize stagecoaches that were faster but more costly. Walking beside immigrant family wagons was the predominant and cheapest means of traveling the Strasbourg to Havre route. [25]

- French Railway: Parts of the westward journey to Paris could have been made on segments of the emerging Paris-Est–Strasbourg-Ville railway in France. However, the railway between Paris and Strasbourg was not complete at the time of John’s travels. [26] In addition, John could have used the Paris–Le Havre railway to finish his inland journey to Havre. [27] The development of the railway system, particularly the completion of the Paris-Le Havre railway line in 1847, significantly facilitated the movement of people, including immigrants, between these two cities. This railway connection allowed for faster and more efficient travel compared to river barges, which were generally used for cargo rather than passenger transportation during this time. [28]

- River Barges: While traveling by road or rail may have been more prevalent, John could have also utilized barges on the Seine River once he made it to Paris to finish his journey to Le Havre. [29] “In continuing the journey the majority embarked upon steamboats on the Seine, or traveled as deck passengers upon the barges that these steamboats towed to the port. Three times a day stages sets out for Le Havre, but such a conveyance was usually too expensive.” [30]

- Canals: The use of rivers and canals were not useful or available for John Sperber’s travel to Le Havre in 1852. The Marne–Rhine Canal was built concurrently with parts of the Paris-Est–Strasbourg-Ville railway and by the same administration, from 1839 to 1855. Their course is parallel. However, it was not complete when John was traveling eastward to Le Havre. [31]

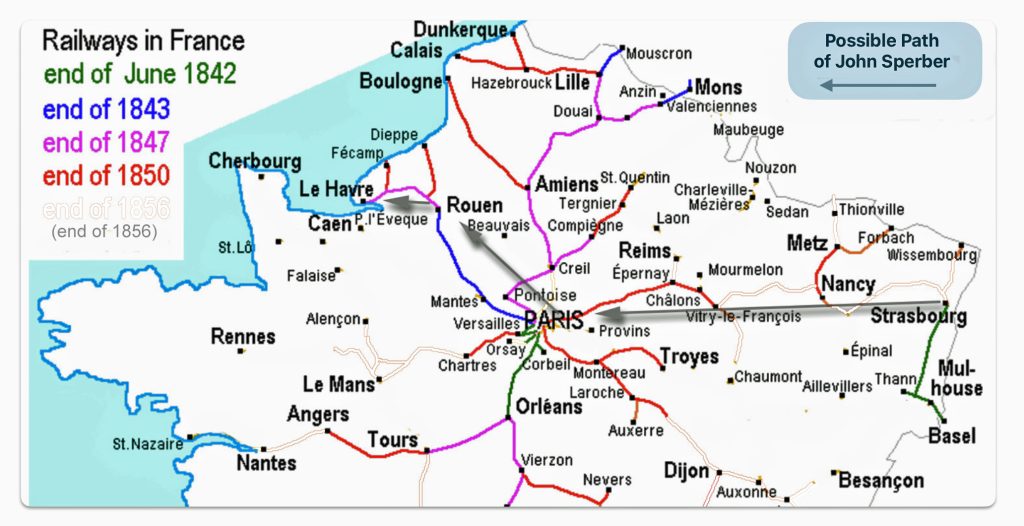

The Emergence of Railways in mid 1800 France

If John traveled by railway, his options were limited. The rail line between Paris and Strasbourg was built and operated by the Compagnie du chemin de fer de Paris à Strasbourg, which later became part of the Chemins de fer de l’Est This railway line between Paris and Strasbourg was complete after John arrived to the United States. It was not available for him when he emigrated to the United States. in 1852.

The first section of the French railway line between Le Havre and Strasbourg was opened in 1849. This first section connected Paris to Châlons-sur-Marne (see map thirteen below). In 1850 a line from Nancy to Frouard and a line from Châlons to Vitry-le-François were completed. In the following year, a line from Vitry-le-François to Commercy as well as a line from Sarrebourg to Strasbourg were completed. Finally, in 1852, the year John Sperber emigrated, the sections between Commercy and Frouard, and the line between Nancy and Sarrebourg were opened. The 1852 sections were probably open after John’s voyage in June 1852. [32]

During this period, railway technology and infrastructure were rapidly developing. As reflected in map fourteen, I have modified and removed from the original source map all of the rail lines that were built between 1850 and 1856. You can see, however, remnants of removed lines for the railways completed in this six year period. John may not have been able to travel by rail between Strasbourg, Nancy and Vitry-le-François. Even if he was able to travel by train, his journey would have been interrupted and punctuated with the need to travel by roadways where the train line was under construction. [33]

Map Fourteen: French Railway System 1842 – 1850

Once John Sperber reached Paris, he may have continued the final leg to Le havre by train on the 142 mile long Paris–Le Havre railway. Conversely he may have continued his journey on barges or steamboats on the Seine River as a deck passenger. If both of these two alternatives were outside his budget, he may have traveled on wagons to Le Havre. [34]

The stretch of railway between Paris and Le Havre was among the first railway lines in France. The section from Paris to Rouen opened on May 9, 1843, followed by the section from Rouen to Le Havre that opened on March 22, 1847. [35]

Type of Road Transport in France

As discussed above, the typical method for traveling by road was the use of established overland freight wagon commerce routes to Paris. These roads were well established and used for over one hundred years. Due to their value to the French military and commercial business interests, they were, compared to other roads in France, in better condition.

The cotton industry relied heavily on the roads between Le Havre and Strasbourg for commercial freight transport to the Alsace region of France. Manufactured goods and immigrants were transported on the’ return trip’.

The major roads, such as those between Paris and Strasbourg, were noted back in the late 1700s:

“In France the great post-roads, the roads which make the communication between the principal towns of the kingdom, are in general kept in good order; and in some provinces are even a good deal superior to the greater part of the turnpike roads of England. But what we call cross-roads, that is, the far greater part of the roads in the country, are entirely neglected, and are in many places absolutely impassable for any heavy carriage.” [36]

John Sperber may have utilized a major road commerce route to Le Havre. Overland freight wagon commerce routes were developed and used in the 1830s and 1840s between Le Havre and Strasbourg .

“Freight wagons returning from Basel and Strasbourg to Le Havre carried passengers willing to travel the slow way, while persons with more means forwarded their heavy household belongings by the freighters and themselves used the more rapid stage lines. Most of the emigrants, however, started towards the west in the style of their American contemporaries – in covered wagons. The family carriage was arched with sailcloth and the interior packed with the women, children and baggage. The men and older boys walked outside, leading the horses. In this fashion long caravans set out from the German – French border, camping each evening by the wayside and frugally consuming the supply of food that was to support them across the Atlantic.” [37]

Based on a number of historical accounts and research on German immigration, German immigrants in the 1840s and 1850s possibly used a few different types of wagons to travel from Strasbourg to the port of Le Havre that were similar to the following:

- Freight wagons – Emigrants could obtain transport on freight wagons returning from the east of France after delivering goods from Le Havre. These wagons allowed immigrants to travel overland from places like Strasbourg to the port of Le Havre on their return trip back to Le Havre. [38]

- Conestoga wagons – German settlers in America designed and built the Conestoga wagon, which was used in opening up the American frontier. It is possible a similar designed sturdy covered wagon was used by immigrants in Europe to transport their belongings to port cities. [39] “The name came from an area along the Conestoga River Valley in Lancaster County. Some sources say at the confluence of the Conestoga River and the Little Conestoga Creek. Here, Pennsylvania German and Swiss wagon builders created the massive, sturdy wagons needed to ship farm products the sixty-four-mile journey to market in Philadelphia. A product of several influences, the wagon took shape over time.” [40]

- Prairie schooner – nineteenth century covered wagon popularly used by emigrants traveling to the American West. The name prairie schooner was derived from the wagon’s white canvas cover which gave it the appearance, from a distance, of the sailing ship. The prairie schooner was smaller and lighter than the Conestoga wagon and was more suitable for long-distance travel. Unlike the Conestoga, which had a body that angled up at each end and prevented cargo from tipping or falling out, the prairie schooner had a flat horizontal body. The sides of which were lower than those of the Conestoga. [41]

During the mid-19th century, the most common types of wagons used for long-distance travel and migration in Europe and America included the wagon similar to the Conestoga wagon and the prairie schooner. The Conestoga wagon, known for its large size and capacity, was primarily used in the United States for transporting goods over long distances. A smaller sized wagon, similar in design to the prairie schooner, was likely used by immigrants traveling from Strasbourg to Le Havre due to its size and the nature of European roads and travel conditions at the time. [42]

The Speed of Road Travel and Travel Time

“(The) dramatic acceleration in the pace of travel was perhaps the Ancien Régime’s most impressive domestic achievement. It was given its most durable visual tribute by Joseph Vernet, in his magnificent painting of 1774 entitled The construction of a highway (now in the Louvre). In the foreground a group of workmen are creating a broad paved road, supervised by a foreman who is pictured reporting to a group of engineers on horseback, dressed in smart blue uniforms with gold facings; the road winds its way along an embankment cut out of the side of a hill, towards a three-span bridge, itself under construction with the assistance of two large cranes; the ultimate destination is a hill-top town, overlooked by a large windmill. The entire painting speaks of hostile nature tamed by human ingenuity and labour.” [43]

Construction of a Large Road 1774, Oil Painting by Claude-Joseph Vernet

Travel by horse-drawn coach was the more traditional method during this period. The speed of horse-drawn coaches could vary significantly based on the condition of the roads, the weather, and the need for frequent stops to rest the horses and for passengers to eat and sleep. A typical speed for a horse-drawn coach could be around 3.5 to 5 miles per hour. Considering the direct distance between Strasbourg and Havre is approximately 500 miles, the journey could take roughly 100 to 142 hours of continuous travel. However, with necessary stops for rest and assuming only daylight travel, this could extend the travel time significantly, potentially making the journey last several days to a couple of weeks.

If John Sperber used part of the rail route that was completed in 1852, it would have likely reduced the travel time compared to solely using horse-drawn coaches or wagons. Trains could travel at speeds significantly higher than coaches, approximately 20-30 miles per hour by mid-century standards. Assuming a combination of rail and coach travel was utilized, the journey from Strasbourg to Havre in 1852 could have taken anywhere from several days to about a week. This estimate considers potential railway use for part of the journey and the slower pace of horse-drawn coaches for other segments, along with stops for overnight rest and other delays.

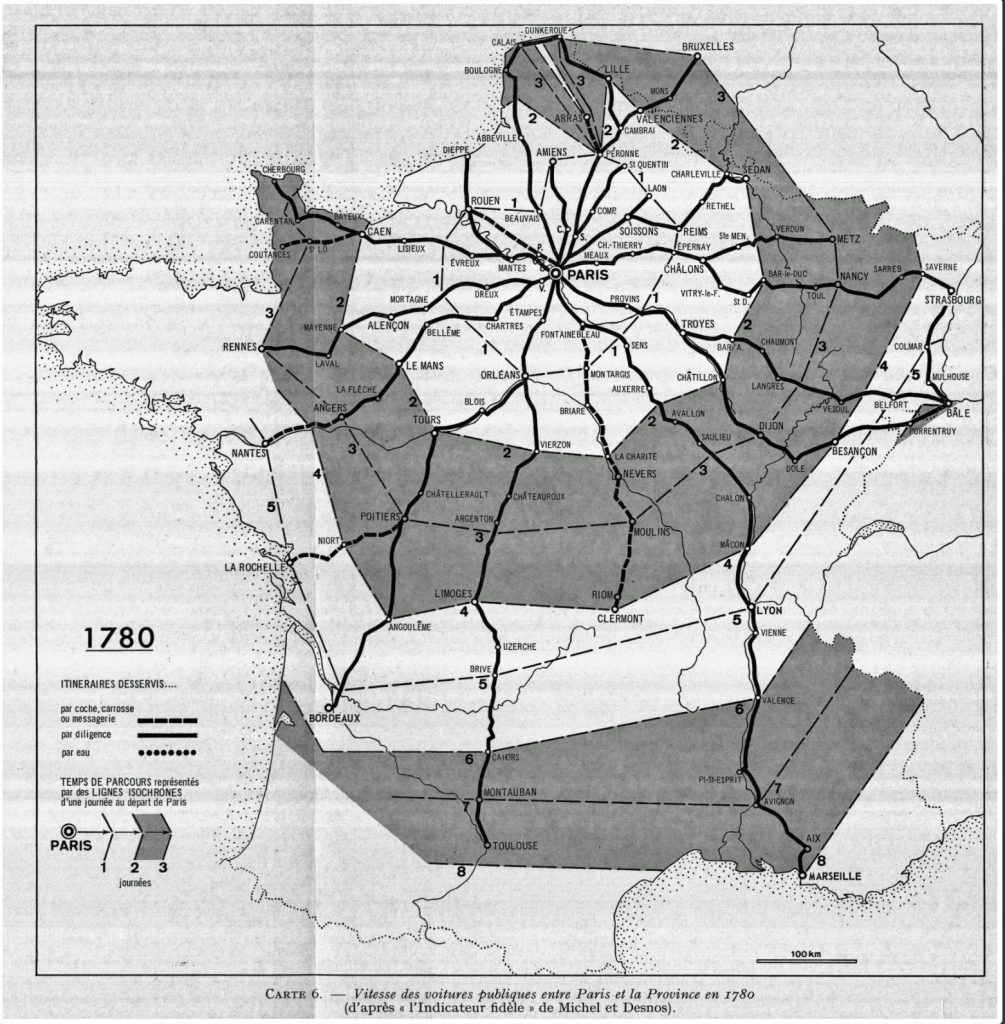

The following map fifteen reflects the “fastest” speeds of the day in 1780 traveling from Paris to other towns and cities in the country. Traveling by stage coach from Strasbourg to Rouen was estimated to take five days.

“Since the main roads have been resurfaced and relatively well maintained throughout the kingdom, traveling by car is no longer quite an adventure. Certainly, its high cost still makes it the mode of transport only for the wealthy classes, but, among them, it is becoming popularized in some way. … We are also witnessing a standardization of daily speeds which makes the map look like an almost regular spider’s web. Most of the cities which today form the “great crown” of Paris is only a day’s journey away in 1780.” [44]

Map Fifteen: Duration of Travel From Paris to Outlying Areas 1790

It is not known how fast German immigrants traveled by wagon. The duration of the journey was influenced by weather, the weight of the wagon, sickness of the travelers, and other factors. Table three provides a glimpse of various speeds of travel based on types of four wheeled vehicles and the conditions of roads at different time periods places.

While it is difficult to estimate how long the inland journey from Baden to Le Havre was for John Sperber, we can deduce a rough estimate of time. it might have taken one day for John Sperber to reach Strasbourg.

He may have made arrangements to travel with a family or individuals that were from his local town. If so, the estimate of time for the trip across northern France could vary depending on the type of vehicle he used to make the inland trip. If he traveled with others via wagon, the trip across France may have taken up to 26 days or a month. [45]

Table Three: Speed of Travel on French Roads Between Paris and Strasbourg

| Date | Type of Vehicle | Location | Days of Trip | Kilometers Per Day | Miles Per Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1765 1 | Coach | France | 11.5 | 42 | 26 |

| 1875 1 | Diligence [46] | France | 7.5 | 91 | 56.5 |

| ~1850 | Covered Wagon [47] | U.S. | – – | 13 – 32 | 8 – 19 |

| ~1850 | Prairie Schooner [48] | U.S. (Oregon Trail) | – – | 24-32 | 15 – 19 |

| ~1850 | Conestoga wagon [49] | U.S. | – – | 24 | 15 |

The photograph below depicts a conestoga wagon with a team of six horses in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania around 1910. [50]

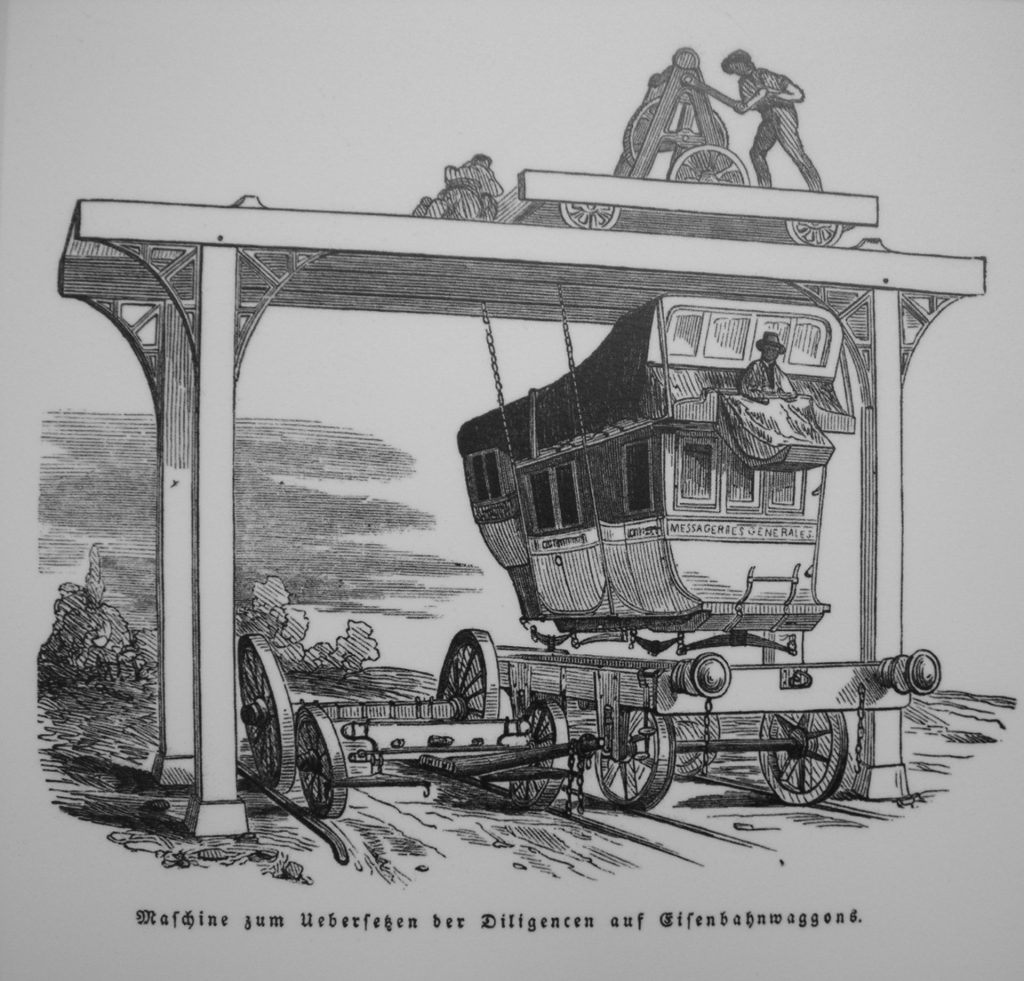

The drawing below portrays the body of a diligence being transferred to a railroad car with a simple gantry crane, an example of early intermodal freight transport by the French Mail, 1844. [51]

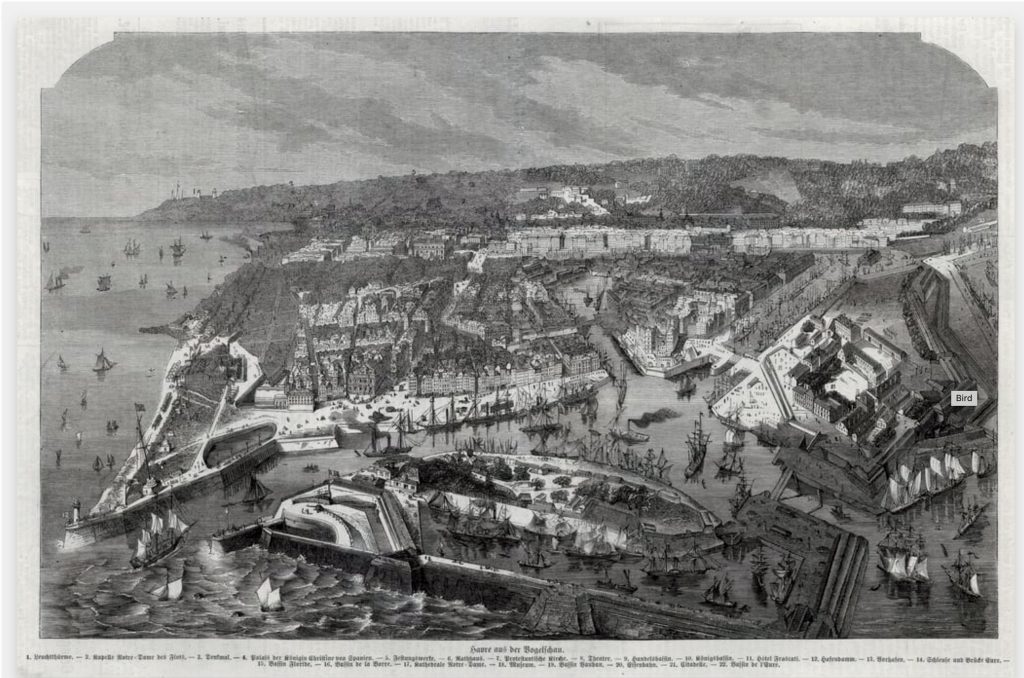

Le Havre “The Harbor”

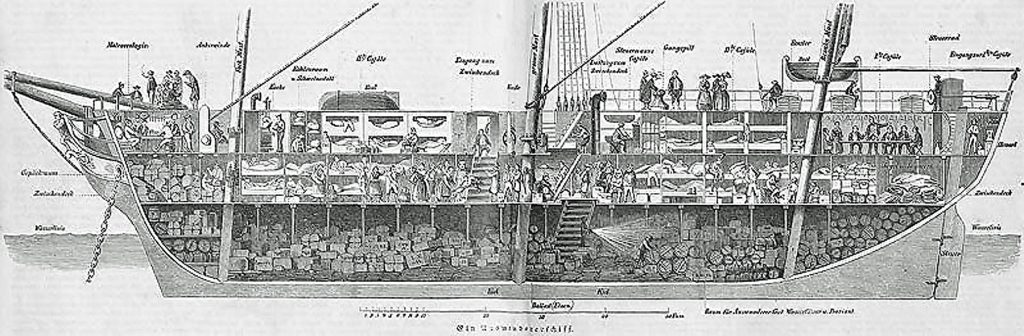

Once John Speber reached the port city of Le Havre, his journey was half way completed. He then anticipated the trials and tribulations of sea travel for up to 30 days on a boat.

“The city was, in fact, a child of America. Francis the First in 1519 had built at the mouth of the Seine :The Harbor” from which to send expeditions to the New World.” For three centuries explorers, privateers and colonists had set out from its quays.” [52]

Bird’s Eye View of Le Havre [53]

Relative to the German ports of Bremen and Hamburg, Le Havre first gained prominence in transporting Germans to America.

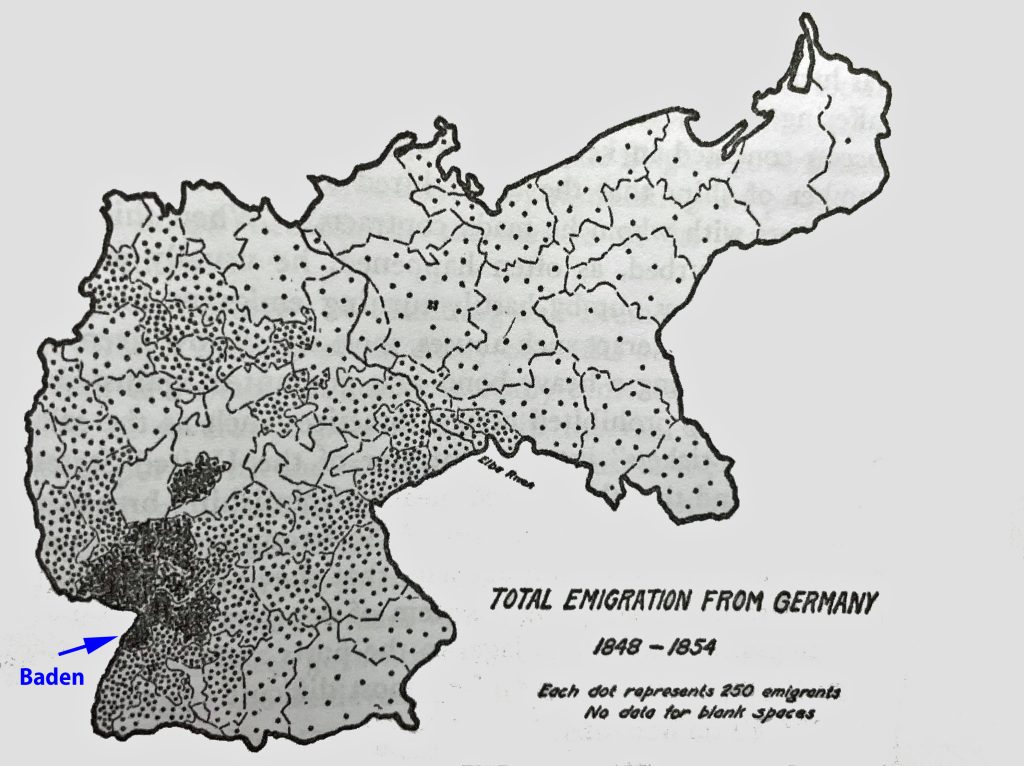

“In the first half of the 19th century, German emigrants came mainly from the southwest of Germany and were driven by the agrarian crisis of 1816-1817, the economic crisis of 1830 and the revolutionary wave of 1848, or rather its reflux, which caused the migratory flow to peak (240,000 departures in 1854).” [54]

The port’s prominence was established on the backbone of the cotton industry networks for transporting raw cotton to the textile manufacturing plants in the Alsace region in France. Le Havre became part of the cotton global trade network. “Imports of cotton into France’s most important cotton port, Le Havre, grew by nearly 13 times between 1815 and 1860.” [55]

It was noted in 1831 that “(t)he value of goods carried between Strasbourg and Le Havre surpassed five hundred million Frances annually with freight charges of almost fifty million.” [56]

The Alsace region had a long history of textile production. With the mechanization of the textile industry in the late 1700s and through the 1800s, it became one of France’s leading textile centers in the nineteenth century. Alsace is an historical region in north eastern France on the Rhine River plain. It borders Germany and Switzerland, Alsace has alternated between German and French control over the centuries. . [57]

Politics and costs associated with cotton transport determined the eventual course of transport. The Rhine River was a natural route to transport raw cotton from the United States from the port of Le Havre to Strasbourg and Mulhouse in the Alsace region. However, the tariffs levied by the various German states along the Rhine made it a costly endeavor to transport goods down the river. Consequently a cheaper, alternative inland route was found to ship imported raw cotton to textile manufacturing areas. Cotton imported through Le Havre was transported overland in France.

This overland commerce route also became a major transportation artery for German immigrants that utilized the ships returning to America.

“Le Havre in the 1840s imported cotton from the American south and sent “passagers d’entrepot” back to the United States. In the early 1840s and 1850s it was the main port for migrants from Baden, Bavaria, and Wurttemberg as well as from Switzerland and Alsace, as it was closer to these regions than German, Belgian, or Dutch ports. Although the overseas voyage to the United States was more expensive from Le Havre than from Antwerp, Rotterdam, Liverpool, or London, the Basel-Strasbourg-Paris-Le Havre Railway, completed in 1852, offered a more direct route. Le Havre was the major port for the day-laborers, farmers, merchants, and also iron and textile workers from Mulhouse and Guebwiller. In the 1840s and early 1850s more Germans left for the United States from Le Havre, Rotterdam, Antwerp, London, and Liverpool than from Bremen or Hamburg.” [58]

During the period in which John Sperber emigrated, Le Have experienced a population boom, between 1846 and 1851 the population grew almost 13 percent from 31,325 to 56,964. [59]

The port began to function as an emigration port at the end of the Napoleonic wars around 1815. Boarding passengers was a by-product of commercial shipments. As ship travel gained importance not only for commercial commerce but also for immigration, the docks at Le Havre were enlarged to accommodate the increased steamboat traffic from local ports. A German colony of innkeepers, shopkeepers and brokers subsequently developed to service the emigrant needs at the port. [60]

Largely due to the influx of German immigrants, Le Havre took on the appearance of a German town.

“During the active season there were always several thousand in the city awaiting the hour of departure. The delay might extend from one to six weeks or more if the winds were contrary or the congestion was great. In the meantime they lodged in the cheapest houses, sometimes several families to a room, cooking and washing and keeping as much as possible outdoors.” [61]

Map Eighteen: Section of the Carte D’ETAT-MAJOR 1820-1866 of Port Du Havre [62]

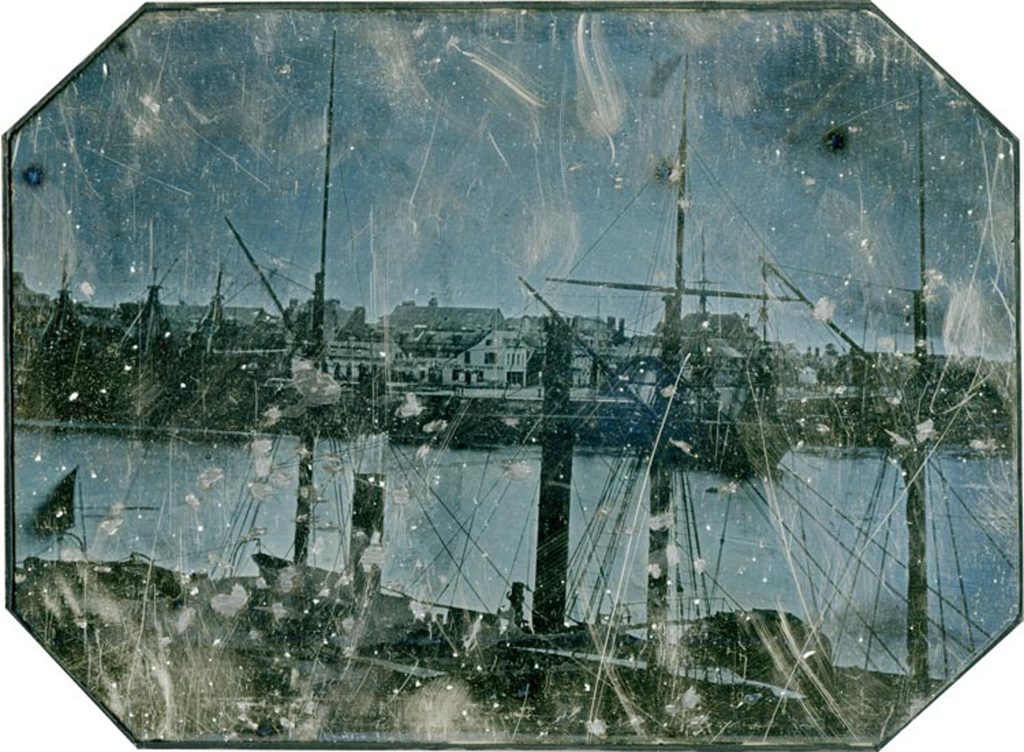

The Port of Le Havre – German District

(The) “Germain district, (photograph below) which can be clearly seen in the center of the image. This small port district of the old Le Havre (barely one hectare in area), built on the former north-western front of the citadel, remains unknown, or even ignored, no doubt because of its short existence (1816-1856). … (the Germain district was) wedged between the barracks of the old citadel and the quay of the same name. Five small streets crossed the quarter, some of which were lined with shops and stalls. The 300 inhabitants, for the most part of modest backgrounds, exercised professions as diverse as sailor, day laborer, grocer, shoemaker or liquor shopkeeper. [63]

While the reliability of the statistics is not certain, the predominance of Germans emigrating from the port of Havre is reflected in the following figures in table four for the years of 1852 and 1853, close to the time when John Sperber emigrated. Le Havre was a major port of departure for German émigrés from the southwestern region of the German states.

“In 1852 (the year that John Sperber emigrated), 63% of the 72,325 emigrants embarked at Le Havre were Germans. This figure even rises to 78.5%, or 54,000 emigrants Germans, in 1853. German emigration through the port of Le Havre then reached a peak which will never be surpassed.” [64]

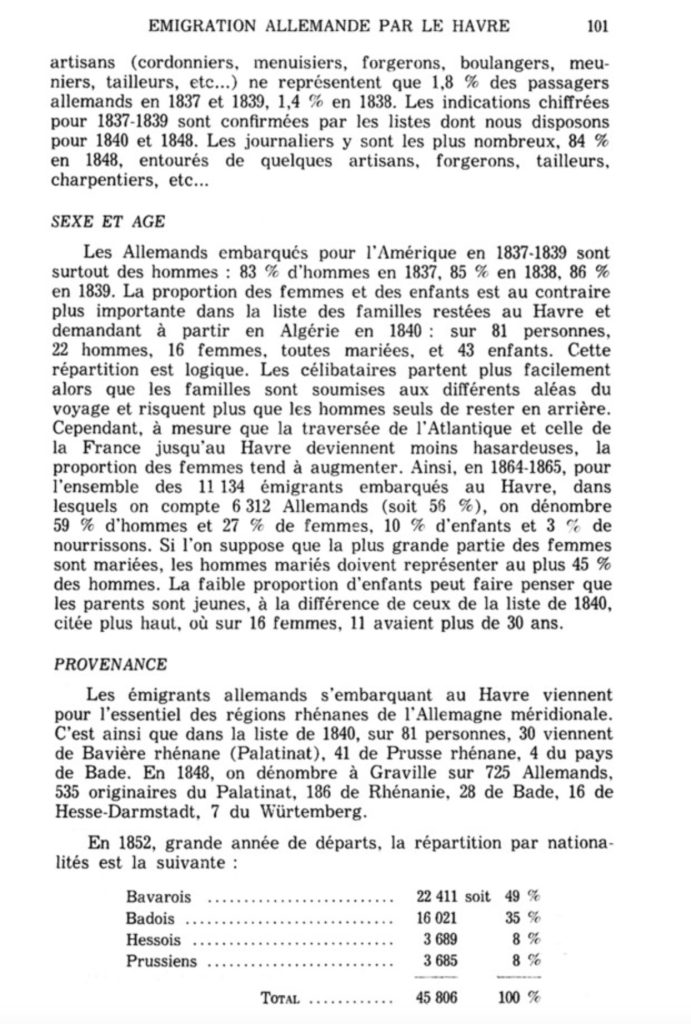

In 1852, the year John Sperber left for America, the distribution of German emigrants departing from Havre was as follows. [65]

Table Four: Number of German Emigrants Departing from Havre 1852 by German State Origin

| Reported German State of Origin | Number of Emigrants | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Bavarian | 22,411 | 49 % |

| Baden | 16,021 | 35 % |

| Hessian | 3,689 | 8 % |

| Prussian | 3,685 | 8 % |

| Total German Emigrants | 45,806 | 100 % |

As reflected in the table five, emigrants from Baden represented roughly one third of the total number of Germans departing from Havre in 1852. Almost fifty percent were from Bavaria.

An Inland Journey to Le Havre with a Rich Tradition

The path from Strasbourg to Havre was made by many German immigrants from the southwest German states and Switzerland. Despite the emergence of Bremen and Hamburg as competing ports for immigrating to the United States in the late 1840s and 1850s, the journey to the port of Le Havre from the Grand Duchy of Badin was a popular path to the United States partly based on tradition, geographical position and convenience. This tradition of departing from Le Havre began shortly after the Napoleonic era from 1815.

A review of statistics on the number of immigrants leaving from the Le Havre port between 1837 and 1859 underscore the predominance and intergenerational tradition of Germans using this port for their journey to the United States. As indicated in the table six below, Europeans embarking for the United States via Le Havre were predominately from German states between 1837 and 1856. John Speber’s journey was part of the height of this wave.

Table Five: German Immigrants Leaving from Le Havre for United States [66]

| Year | No. of German Immigrants | Percent of Total Immigrants | Total No. of Immigrants |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1837 | 5,527 | 66.5 | 8,311 |

| 1838 | 2,677 | 65.0 | 4,122 |

| 1839 | 7,800 | 77.0 | 10,110 |

| 1852 | 45,806 | 63.0 | 72,325 |

| 1853 | 54,000 | 78.5 | 68,836 |

| 1856 | 13,317 | 58.2 | 22,873 |

| 1857 | 18,425 | 47.0 | 38,700 |

| 1858 | 8,300 | 44.5 | 18,235 |

| 1859 | 6,500 | 44.5 | 15,393 |

During the 1830’s “(m)any still preferred the more logistically simple route of crossing the Rhine at Strasbourg, going on to Paris, then to Le Havre. There was an established tradition among emigrants who did not wish to pay for a ride in a cotton wagon to do the overland journey on their own horses, and then to sell the animals at Paris’ horse fairs in order to raise money before the final barge trip down the Seine. The route was long, but straightforward, and covered some of its own costs. During the 1830s Le Havre still benefitted from more regular transatlantic traffic than Bremen, another point that proved to be decisive for many migrants in the early days. A cost which had to be factored into the migrant’s journey was board in the port of departure.” [67]

John Wolfgang Sperber was no different than his Baden brethren when it came to choosing his course of action to immigrate to the United States.

Sources

Feature Photograph: The feature photograph is a portion of 1849 railway and roadway map of the German states and neighboring countries. It visually indicates the probably path the John Sperber undertook to travel to Le Havre to begin his trans-Atlantic voyage to the United Stages.

Source: Bahnkarte von Deutschland und Nachbarländern 1849. Dünne Linien sind Straßen (Railway map of Germany and neighboring countries 1849. Thin lines are roads), Source: Karten- und Luftbildstelle der DB Mainz (Map and aerial photography center of the DB Mainz), current version 17 Nov 2008, Wikimedia Commons,This page was last edited on 23 December 2023 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bahnkarte_Deutschland_1849.jpg

[1] Mitchell, Allan, The Great Train Race: Railways and the Franco-German Rivalry, 1815 – 1914, New York: Berghahn Books, 2000, Page 47 – 48

[2] Lithograph of J. Schütz, Train leaves the station of Heidelberg (Germany) in the year 1840 (Ausfahrt eines Zuges aus dem Heidelberger Bahnhof, 1840), 1842 , This page was last edited on 17 September 2023 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Heidelberg_Station_1840.jpg

[3] Grand Duchy of Baden State Railway, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 23 March 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Duchy_of_Baden_State_Railway

[4] This is a modified version of a map created by MCMC, Plan der Eisenbahnstrecken in Baden 1870, Wikimedia Commons, 15 January 2006, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baden_Railwaymap_1870.png

I have modified the map to conform with rail lines that werecompleted before John Speber embarked to America in 1852.

[5] Baden main line, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 28 November 2023, This page was last edited on 28 November 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baden_main_line

Grand Duchy of Baden State Railway, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 23 March 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Duchy_of_Baden_State_Railway

History of rail transport in Germany, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_rail_transport_in_Germany

[6] Rhine Bridge, Kehl, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 25 February 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhine_Bridge,_Kehl

Mitchell, Allan, The Great Train Race: Railways and the Franco-German Rivalry, 1815 – 1914, New York: Berghahn Books, 2000, Page 49

Kehl, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 11 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kehl

[7] Châlons-en-Champagne and Châlons-sur-Marne refer to the same city in France, but the name was officially changed from Châlons-sur-Marne to Châlons-en-Champagne in 1998. The renaming was part of a broader initiative to reflect the city’s historical and cultural connections to the Champagne region. The name “Châlons-sur-Marne” was used until 1997, and the change to “Châlons-en-Champagne” was intended to strengthen the city’s identity linked to the prestigious Champagne appellation

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Châlons-en-Champagne”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 2 Jun. 2017, https://www.britannica.com/place/Chalons-en-Champagne

[8] I have overlayed map two onto a topographical map. The original topographical map was created by Frank Ramspott, Aug 1 2017, France Country 3D Render Topographic Map Border , fineartamerica, https://fineartamerica.com/featured/france-country-3d-render-topographic-map-border-frank-ramspott.html

[9] Anonymous, Abelor G. (1973) The great alteration of the French roads in the 18th century, Economic History Blog, April 19, 2008, https://premodeconhist.wordpress.com/2008/04/20/abelor-g-1973-the-great-alteration-of-the-french-roads-in-the-18th-century/

Arbellot Guy (1973) “La grande mutation des routes de France au XVIIIe siècle”, Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, 28/3. 1973, Pages 769, https://www.persee.fr/doc/ahess_0395-2649_1973_num_28_3_293381

[10] “Redressant ou meme négligeant totalement les sinuosités des anciennes routes et cherchant, par la, a retrouver la rectitude des voies romaines, les ingénieurs du xv111e siècle choisirent toujours les traces les plus courts autant qu’il était possible. … Mais a route evitait le plus souvent les villages, voire certaines petites villes qui l’auraient contrainte a un detour inutile. Un embranchement suffi.sait alors a les desservir. Dans les montagnes par contre, tout en essayant de conserver de longues sections rectilignes, on recherchait des traces adaptes aux exigences du relief de telle manière que les rampes ne puissent dépasser que tres exceptionnellement 5 pouces par toise (soit environ 7 %).”

Arbellot Guy (1973) “La grande mutation des routes de France au XVIIIe siècle”, Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, 28/3. 1973, Pages 769, https://www.persee.fr/doc/ahess_0395-2649_1973_num_28_3_293381

[11] History of Champagne, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 30 March 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Champagne

Robinson (ed). The Oxford Companion to Wine, Third Edition. pp 150–153. Oxford University Press, 2006.

[12] William Baranès, William, update: M.L. Cohen, La Poste, Updated June 27, 2018, Encyclodi.com, https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences-and-law/economics-business-and-labor/businesses-and-occupations/la-poste#2840900166

La Poste (France), Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 9 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Poste_%28France%29

Cordier, Louis, Died 1711 Engraver, and Alexis-Hubert Jaillot. Map of France’s Post Offices. Paris: Alexis Hubert Jaillot, 1690. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2021668595/

Willis, John, The Scales of Postal Communications in New France in Context, PP 143 – 170, in Le Roux, Muriel, Editor, Post Offices of Europe 18th – 21st Century: A Comparative History, Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang S.A., 2014, https://www.peterlang.com/document/1053838#

Bretagnolie, Anne & Nicholas Verdier, Expanding the Network of Postal Routes in France 1708-1833 PP 183 – 202 in Le Roux, Muriel, Editor, Post Offices of Europe 18th – 21st Century: A Comparative History, Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang S.A., 2014, https://www.peterlang.com/document/1053838#

Conchon, Anne, Cost Economies of Carrying the Mail by Postal Services and Messageries in France (Mid-17th Century – Late 18th Century) PP 253 – 268 in Le Roux, Muriel, Editor, Post Offices of Europe 18th – 21st Century: A Comparative History, Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang S.A., 2014, https://www.peterlang.com/document/1053838#

Conchon, Anne, Roads construction in the eighteenth century France”, Cambridge, Queen’s college (29th March-2nd April 2006), Proceedings of the Second International Congress on Construction History, 2006, vol. 1, p. 791-797 , https://www.arct.cam.ac.uk/system/files/documents/vol-1-791-798-conchon.pdf

Bataillé, Olivier, European Influence on Postal Reform in 19th Century France, PP 415 – 429 in Le Roux, Muriel, Editor, Post Offices of Europe 18th – 21st Century: A Comparative History, Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang S.A., 2014, https://www.peterlang.com/document/1053838#

Le Roux, Muriel, Editor, Post Offices of Europe 18th – 21st Century: A Comparative History, Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang S.A., 2014, https://www.peterlang.com/document/1053838#

Le Roux, Muriel, Post Offices of Europe 18th – 21st Century: A Comparative History, 2014

Lay, Maxwell Gordon and Benson, Fred J.. “road”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 11 Aug. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/technology/road

Guy, Arbellot , “La grande mutation des routes de France au XVIIIe siècle”, Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, 28/3. 1973, Pages 776 – 777., 1973, https://www.persee.fr/doc/ahess_0395-2649_1973_num_28_3_293381

Verdier, Nicholas and Anne Bretagnolle. Expanding the Network of Postal Routes in France 1708-1833.. histoire des réseaux postaux en Europe du XVIIIe au XXIe siècle, May 2007, Paris, France. pp.159- 175. halshs-00144669, https://shs.hal.science/halshs-00144669/document

“Die Ingenieure des Corps des Ponts et Chaussées Von der Eroberung des nationalen Raumes zur Raumordnung”, in A. Grelon, H. Stück (dir.), Ingenieure in Frankreich, 1747- 1990, Francfort, New-York, Campus, 1994, pp. 77-99. French version: http://www.gsd.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/picon-corpsdespontsetchausseese.pdf

Antoine Picon, “La pensée sociale et politique des ingénieurs des Ponts et Chaussées”, in Pour mémoire, n°18, hiver 2016, pp. 24-32. https://www.academia.edu/36791831/Antoine_Picon_La_pensée_sociale_et_politique_des_ingénieurs_des_Ponts_et_Chaussées_in_Pour_mémoire_n_18_hiver_2016_pp_24_32?email_work_card=thumbnail

[13] Guy, Arbellot,“La grande mutation des routes de France au XVIIIe siècle”, Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, 28/3. 1973, Pages 776 – 777., 1973 https://www.persee.fr/doc/ahess_0395-2649_1973_num_28_3_293381

[14] Verdier, Nicholas and Anne Bretagnolle. Expanding the Network of Postal Routes in France 1708-1833.. histoire des réseaux postaux en Europe du XVIIIe au XXIe siècle, May 2007, Paris, France. pp.159- 175. halshs-00144669, https://shs.hal.science/halshs-00144669/document

[15] The map is a portion of the map: Figure 3-bis: Postal roads and main cities and towns in 1833 in Verdier, Micolas and Anne Bretagnolle. Expanding the Network of Postal Routes in France 1708-1833. histoire des réseaux postaux en Europe du XVIIIe au XXIe siècle, May 2007, Paris, France. pp.159 – 175. https://shs.hal.science/halshs-00144669/document

[16] Alexis-Hubert Jaillot and Cordier, Louis, Map of France’s Post Offices (Carte particulière des postes de France), Paris: Alexis Hubert Jaillot, 1690, Retrieved by the , control number 2021668595, Library of Congress, https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.wdl/wdl.14770

[17] The maps and graphs of elevation and gradients for the various segments of John Sperber’s journey were produced using FlattestRoute, https://www.flattestroute.com/

[18] This is one section of an amazing compilation of maps of the entire nation of France made between 1837- 1869. It is a survey map that was created by the military in the 19th century. Like the Cassini map that was made in the 1700s, it is very precise and covers the whole territory of France.

See: Dépôt de la guerre , [Carte de France de l’Etat-Major] / levée par les Officiers du Corps d’Etat-Major … gravée et publiée par le Dépôt de la Guerre. Paris: Dépôt de la Guerre 1837-1869 ; Found In: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library Yale University Library , https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/15831671

On the French Geoportail website, you can also find “la carte de l’état-major“. https://www.geoportail.gouv.fr

Map of Strasbourg 1842, d’apres le plan général dressé par J. N. Villot Architecte de la ville Strasbourg https://www.myfrenchroots.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Old-map-Strasbourg-19th-century.jpeg

[19] Affleck, Fred Norman, The Beginnings of Modern Transport in France: The Seine Valley, 1820 to 1860, PhD Thesis, London University, 1972, Page 30 https://www.academia.edu/78049678/The_beginnings_of_modern_transport_in_France_the_Seine_Valley_1820_to_1860

[20] Ibid, Page 32

[21] Verdier, Micolas and Anne Bretagnolle. Expanding the Network of Postal Routes in France 1708-1833. histoire des réseaux postaux en Europe du XVIIIe au XXIe siècle, May 2007, Paris, France. pp.159 – 175. https://shs.hal.science/halshs-00144669/document

[22] Le Havre’s old tramway, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 28 November 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le_Havre%27s_old_tramway

[23] Affleck, Fred Norman, The Beginnings of Modern Transport in France: The Seine Valley, 1820 to 1860, PhD Thesis, London University, 1972, Pages 43 – 93 https://www.academia.edu/78049678/The_beginnings_of_modern_transport_in_France_the_Seine_Valley_1820_to_1860

[24] The Service Géographique’s Carte de France refers to a detailed topographic map series produced by the French military’s geographical service, known as the Service Géographique de l’Armée. This map series, often referred to as the “Carte d’état-major,” was initiated in the early 19th century and played a crucial role in military and administrative planning in France.The Carte de France was notable for its scale and detail, typically at 1:80,000, which allowed for precise military and civil use.

The production of these maps was a significant undertaking, involving extensive surveys and cartographic expertise. The maps were highly regarded for their accuracy and detail, including topographical features like elevation contours, waterways, and urban layouts, which were essential for both military strategy and civil administration.

The Service Géographique de l’Armée was responsible for the creation and distribution of these maps until its dissolution in 1940. The maps produced by this service formed the basis for many modern cartographic efforts in France and were integral to the development of French geographic and cartographic capabilities.

En Ligne Carte de France de l’Etat-Major, Géoportal Maps, République Française , https://www.geoportail.gouv.fr/carte

Dépôt de la Guerre, [Carte de France de l’Etat-Major] / levée par les Officiers du Corps d’Etat-Major … gravée et publiée par le Dépôt de la Guerre, Published 1837-1869, Paris: Dépôt de la Guerre, Scale 1:80,000, https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/15831671

Carte D’Etat-Major 1820-1866, https://geocatalogue.apur.org/catalogue/srv/api/records/833fc566-cdbf-418e-8485-6fcd00af118b

Carte d’état-major, Wkiipédia, La dernière modification de cette page a été faite le 20 avril 2024, https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carte_d%27état-major

[25] Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Pages 186 – 187

[26] Paris-Est–Strasbourg-Ville railway, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris-Est–Strasbourg-Ville_railway

[27] Paris–Le Havre railway, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 25 January 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris–Le_Havre_railway

[28] Arbellot, Guy, “La grande mutation des routes de France au XVIIIe siècle”, Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, 28/3, 1973, Pages 776-777

[29] Affleck, Fred Norman, The Beginnings of Modern Transport in France: The Seine Valley, 1820 to 1860, PhD Thesis, London University, 1972 https://www.academia.edu/78049678/The_beginnings_of_modern_transport_in_France_the_Seine_Valley_1820_to_1860

[30] Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Pages 187

[31] Marne–Rhine Canal, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 28 February 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marne–Rhine_Canal ; May, David Edwards, Canal de la Marne au Rhin, French Waterways, https://www.french-waterways.com/waterways/north-east/marne-rhin/

[32] Paris-Est–Strasbourg-Ville railway, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 14 June 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris-Est–Strasbourg-Ville_railway

Direction Générale des Ponts et Chaussées et des Chemins de Fer, Statistique centrale des chemins de fer. Chemins de fer français. Situation au 31 décembre 1869 (in French). Paris: Ministère des Travaux Publics, 1869, pp. 146–160

[33] Modified version of Map originally from ULamm, France1860railways.png, 24 Aug 2009, Wikimedia Commons, This page was last edited on 8 June 2022 , https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:France1860railways.png

[34] Affleck, Fred Norman, The Beginnings of Modern Transport in France: The Seine Valley, 1820 to 1860, PhD Thesis, London University, 1972, https://www.academia.edu/78049678/The_beginnings_of_modern_transport_in_France_the_Seine_Valley_1820_to_1860, Pages 30-42

[35] Paris–Le Havre railway, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 25 January 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris–Le_Havre_railway

[36] Blanning, T.C.W., The Pursuit of Glory: The Five Revolutions that Made Modern Europe: 1648-1815, New York: The Penguin History of Europe, Page 8

https://a.co/6M2cl3v

See also:

Szostak, Rick, Role of Transportation in the Industrial Revolution: A Comparison of England and France. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1991. Pages 60 -90. Source: JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt8112c , also https://www.academia.edu/33825447/Rick_Szostak_The_Role_of_Transportation_in_the_Industrial_Revolution_A_Comparison_of_England_and_France

[37] Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Pages 186 – 187

[38] Kathi Gosz, A Look at Le Havre, a Less Known Port for German Emigrants, Oct 09, 2011, Village Life in Kreis Saarburg, Germany, Blog, http://19thcenturyrhinelandlive.blogspot.com/2011/10/look-at-le-havre-less-known-port-for.html?m=1 ;

Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Pages 186 – 187

[39] The Conestoga wagon , The Germans in America, European Reading Room, Prints and Photograph Division, The Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-24396.;

Jenny Ashcraft, Horse and Buggy: The Primary Means of Transportation in the 19th Century, July 17, 2019, Fishwrap: official blog of Newspapers.com, https://blog.newspapers.com/horse-and-buggy-the-primary-means-of-transportation-in-the-19th-century/ ;

Conestoga Wagon, National Museum of American History Behring center, The Smithsonian Institution, https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/nmah_842999 ; https://www.loc.gov/rr/european/imde/images/wagon.jpg ;

Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Pages 186 – 187

[40] Covered wagons and the American frontier, October 23, 2012, National Museum of American History, Behring Center, Smithsonian Institution, https://americanhistory.si.edu/explore/stories/covered-wagons-and-american-frontier

Boyd, James D., An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, Page 119 https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

[41] unchartedadam, Conestoga Wagon: Century Strong Ship of Inland Commerce, June 19, 2019, https://unchartedlancaster.com/2019/06/19/conestoga-wagon-century-strong-ship-of-inland-commerce/

Hill, William E.. “prairie schooner”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 23 May. 2013, https://www.britannica.com/technology/prairie-schooner

Stewart, George R., The Prairie Schooner Got Them There, American Heritage, Februar 1962, Vol 13, Issue 2, https://www.americanheritage.com/prairie-schooner-got-them-there

[42] What is the Difference between a Conestoga Wagon and a Prairie Schooner, The National Oregon / California Trail Center, https://oregontrailcenter.org/blog/what-is-the-difference-between-a-conestoga-wagon-and-a-prairie-schooner/

[43] Blanning, T.C.W., The Pursuit of Glory: The Five Revolutions that Made Modern Europe: 1648-1815, New York: The Penguin History of Europe, Page 8

https://a.co/6M2cl3v

[44] “Depuis que les grandes routes sont refaites et relativement bien entretenues dans toute l’etendue du royaume, le voyage en voiture n’y est plus tout a fait une aventure. Certes, son cout eleve en fait toujours le mode de transport des seules classes aisees, mais, au sein de celles-ci, ii se vulgarise en quelque sorte. … L’on assiste aussi a une uniformisation des vitesses journalières qui fait ressembler la carte a une toile d’araignée presque régulière. La plupart des villes qui fondent aujourd’hui la « grande couronne » de Paris ne sont plus qu’a une grande journée de voyage en 1780. “

Arbellot, Guy “La grande mutation des routes de France au XVIIIe siècle”, Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, 28/3. 1973, Pages 776 – 777., https://www.persee.fr/doc/ahess_0395-2649_1973_num_28_3_293381

[45] This estimate is based on the total length of the wagon trip being roughly 400 miles and assuming it took an average of 15 miles a day in a wagon.

[46] “The diligence, a solidly built stagecoach with four or more horses, was the French vehicle for public conveyance with minor varieties in Germany such as the Stellwagen and Eilwagen.”

Stagecoach, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 18 March 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stagecoach

Geri Walton, Diligence Coach: How People Traveled in It in France, Unique Histories from the 18th and 19th centuries, March 24, 2014, Blog, https://www.geriwalton.com/diligence-coac/

[47] Jenny Ashcraft, Horse and Buggy: The Primary Means of Transportation in the 19th Century, July 17, 2019, Fishwrap: official blog of Newspapers.com, https://blog.newspapers.com/horse-and-buggy-the-primary-means-of-transportation-in-the-19th-century/

[48] “The usual average rate of travel with such wagons on the Oregon Trail was about 2 miles (3.2 km) per hour, and the average distance covered each day was about 15 to 20 miles (24 to 32 km)”

Hill, William E.. “prairie schooner”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 23 May. 2013, https://www.britannica.com/technology/prairie-schooner

Hill, William E.. “prairie schooner”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 23 May. 2013, https://www.britannica.com/technology/prairie-schooner

Stewart, George R., The Prairie Schooner Got Them There, American Heritage, Februar 1962, Vol 13, Issue 2, https://www.americanheritage.com/prairie-schooner-got-them-there

[49] “The covered wagon made 8 to 20 miles per day depending upon weather, roadway conditions and the health of the travelers.”

Ricki Longfellow, Wagons West, June 27, 2017, Highway History, Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/back0307.cfm

“The average speed was about two miles an hour”

Covered Wagon Facts & History: Lesson for Kids, Study.com, https://study.com/academy/lesson/covered-wagon-facts-history-lesson-for-kids.html

“A Conestoga wagon, pulled by a team of six draft horses, averaged 15 miles a day. Trains were faster, smoother, and less expensive to ride than the stagecoach.”

Traveling on the National Road, Fort Necessity National Battlefield, Friendship Hill National Historic Site, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/national-road-travel.htm

[50] Source of photograph: unchartedadam, Conestoga Wagon: Century Strong Ship of Inland Commerce, June 19, 2019, https://unchartedlancaster.com/2019/06/19/conestoga-wagon-century-strong-ship-of-inland-commerce/

[51] Stagecoach – European , Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 18 March 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stagecoach

[52] Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Page 186

[53] “This engraving, titled “Birds eye view of Le Havre, France, ” takes us back to the 19th century and offers a glimpse into the rich history of this French town. The print showcases the bustling port of Le Havre, located in Normandy along the English Channel. The scene is filled with maritime activity as ships sail through the calm waters, while a tugboat guides them towards their destination. The basins and quays are teeming with boats engaged in trade and passenger transportation, highlighting Le Havre’s significance as a major hub for shipping. Amidst this vibrant coastal scenery stand magnificent churches and a grand cathedral that dominate the skyline. These architectural marvels serve as reminders of Le Havre’s cultural heritage and its deep-rooted connection to French culture.”

Source: reproduction of this engraving are found in various sources. For example : Birds eye view of Le Havre, France (engraving) by German School, 19th century; Private Collection; Illustration from Illustrierte Zeitung (Leipzig, 21 January 1871). Media Storehouse, https://www.mediastorehouse.com/fine-art-finder/artists/german-school/birds-eye-view-le-havre-france-engraving-22568876.html

[54] “Dans la premiere moitie du XIX siecle, les emigrants allemands viennent surtout du sud-ouest de I’ Allemagne et sont pousses par la crise agraire de 1816-1817, la crise economique de 1830 et la vague revolutionnaire de 1848, ou plutot son reflux, qui fait culminer le flux migratoire (240 000 departs en 1854).”

Braunstein, Jean, L’émigration allemande par le port du Havre au XIXe siècle (German Emigration through the Port of Le Havre in the 19th Century), Table: Emigrants Allemands Embarques Au Havre (1830 – 1870), Annales de Normandie, 1984, Page 96, https://www.persee.fr/doc/annor_0003-4134_1984_num_34_1_6382

[55] Beckert, Sven, Empire of Cotton: A Global History, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014, Page 205

[56] Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Page 186

[57] Glazier, Ira, Ed., Germans to America Series II: Lists of Passengers Arriving at U.S. ports in the 1840s, Volume 6 April 1848 – October 1848, Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc 2003, Page xii

[58] Des villages de Cassini aux communes d’aujourd’hui: Commune data sheet Le Havre, EHESS (in French). http://cassini.ehess.fr/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=16833

[59] Gregory Saillard, Discovery of an unknown daguerreotype from old Le Havre: “The quai de la Citadelle circa 1845-1848” , 11 Jan 2023, The Classic, https://theclassicphotomag.com/discovery-daguerreotype-le-havre/

Seaports – Sea Captains, The Maritime Heritage Project – San Francisco 1846 – 1899, Home Port, France: La Havre https://www.maritimeheritage.org/ports/France-Le-Havre.html

[60] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration 1607 – 1860. Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press, 1941, Page 188

[61] Gregory Saillard, Discovery of an unknown daguerreotype from old Le Havre: “The quai de la Citadelle circa 1845-1848” , 11 Jan 2023, The Classic, https://theclassicphotomag.com/discovery-daguerreotype-le-havre/

[62] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration 1607 – 1860. Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press, 1941, Page 187

[63] En Ligne Carte de France de l’Etat-Major, Géoportal Maps, République Française , https://www.geoportail.gouv.fr/carte

[64] Beckert, Sven, Empire of Cotton: A Global History, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014, Pages 95, 148, 202, 205, 211 – 212, 216

See also: Dunham, Arthur L. “The Development of the Cotton Industry in France and the Anglo-French Treaty of Commerce of 1860.” The Economic History Review, vol. 1, no. 2, 1928, pp. 281–307. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2590336

[65] “En 1852, 63 % des 72 325 emigrants embarques au Havre sont des Allemands. Ce chiffre s’eleve meme a 78,5 %, soit 54 000 emigrants allemands, en 1853. L’ emigration allemande par le port du Havre a atteint alors un sommet qui ne sera plus depasse.”

Braunstein, Jean, L’émigration allemande par le port du Havre au XIXe siècle, Table: Emigrants Allemands Embarques Au Havre (1830 – 1870), Annales de Normandie, 1984, Page 97, https://www.persee.fr/doc/annor_0003-4134_1984_num_34_1_6382

[66] Braunstein, Jean, L’émigration allemande par le port du Havre au XIXe siècle, Table: Emigrants Allemands Embarques Au Havre (1830 – 1870), Annales de Normandie, 1984, Page 101, https://www.persee.fr/doc/annor_0003-4134_1984_num_34_1_6382

[67] Boyd, James D., An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, Page 118, https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf ; Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Pages 187