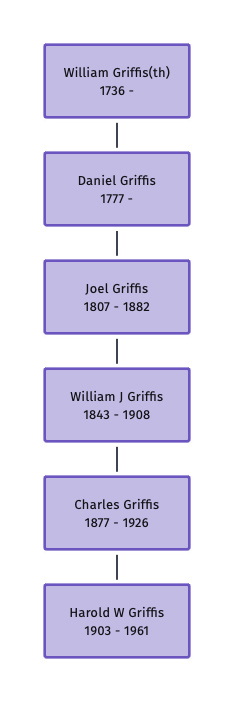

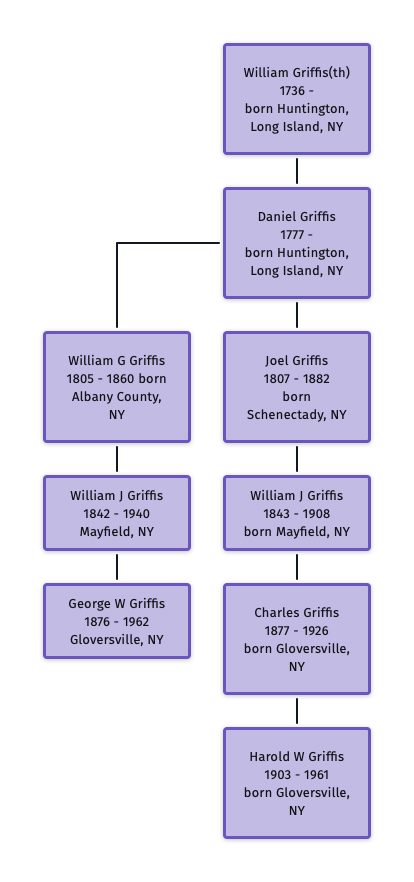

This second part of a four part story will provide a narrative of my discovery process of tracing the Griffis surname for the Griffis Family that originated from Huntington, Long Island back from William James Griffis, who fought in the Civil War, to William Griffis in Huntington, New York. For this part of the story, I am focused on tracing the existence of Griffis surname backwards from the mid 19th century to the 18th century.

As indicated in part one of this story, I was able to push our knowledge of the Griffis surname back an additional three generations from our Civil War veteran, William James Griffis, through his father Joel Griffis, and through his grandfather Daniel Griffis.

“Although it is well known that the majority of the surnames held by Welsh people are of patronymic origin and that relatively few such names are in use by a high proportion of the the population … (t)here is no reason why those researching Welsh families should not share the universal fascination with surnames, though – as with all genealogical research – we must accept that the history of a name does not always throw light on the history of an individual family. For the latter, nothing can replace working systematically backwards, proving links all the way.” [1]

While I do provide a picture of what this Griffis family looks like through time, I also try to provide the reader with a path of discovery that I went through discovering bits and pieces of information and encountering dead ends. The story also provides the frustration one experiences when trying to reconstruct a family tree. Sometimes this does not happen and you are left with unsolved pieces of the puzzle. It is a messy process but in the end, more information is discovered, promising leads are either validated or proven false and a better picture of the past is gained. There is always the possibility of discovering new facts and sources of information to make our view of the family clearer.

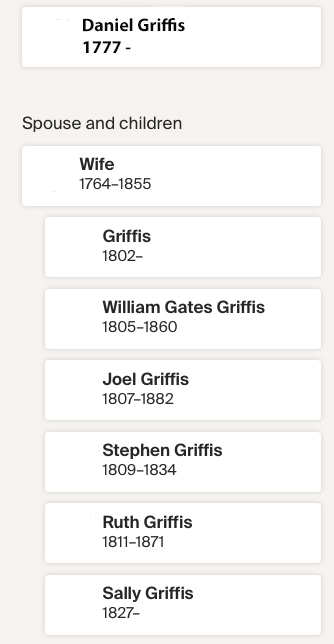

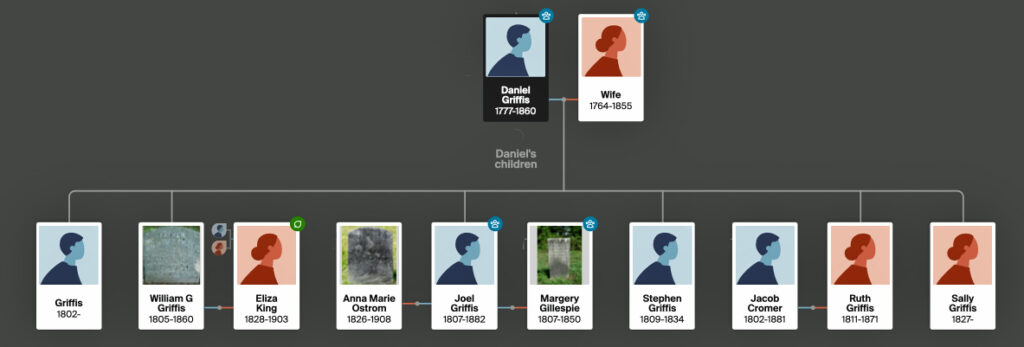

While I am able to establish connections between Harold Griffis, his father Charles, his grandfather William, his great grandfather Joel and his great great grandfather Daniel, and his great great great grandfather William, not much is known of the family of Daniel Griffis. Current research points to his having four sons and an unknown daughter. There is strong evidence that Joel Griffis and William Gates Griffis were two of his sons.

Synopsis

A number of facts pertaining to (1) Daniel Griffis; (2) his older brother Nathaniel Griffes (he spelled the surname differently); (3) Daniel’s son William G. Griffis; (4) Daniel and Nathaniel’s uncle Stephen Gates and his son Stephen Gates Jr. and grandsons; and Stephen Griffith (An older brother of Nathaniel and Daniel) who married a Gates cousin appear to provide supporting evidence of a family connection with the Griffis Mayfield families and the William Griffis Family in Huntington, New York:

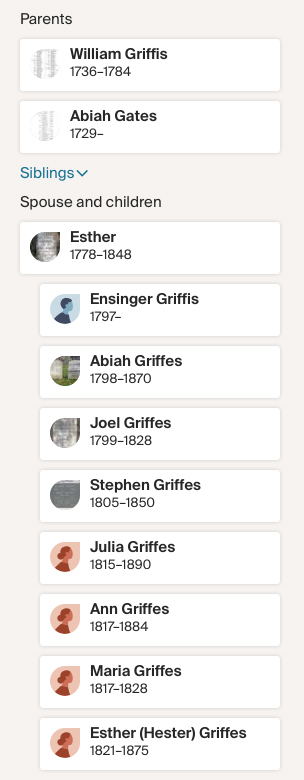

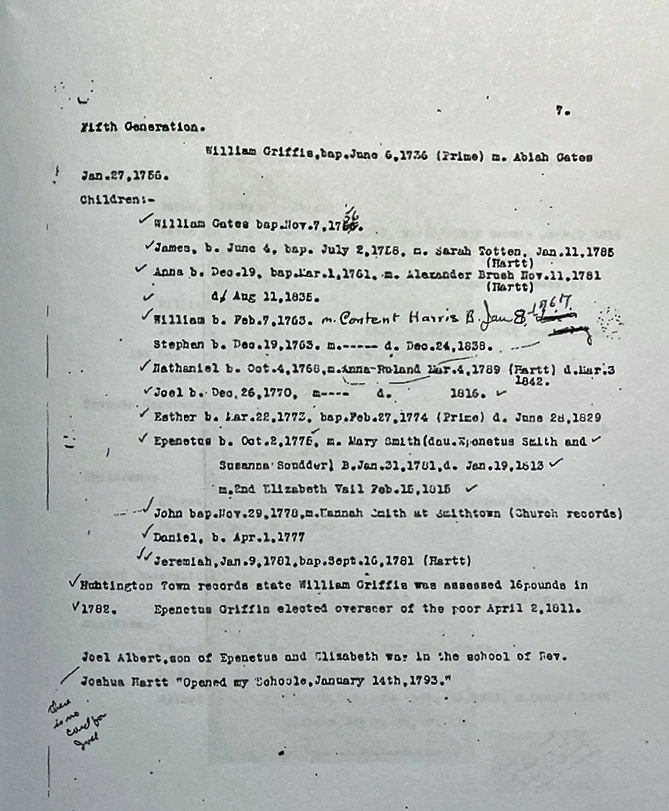

- A family manuscript, the “Peets-Welsh manuscript”, and a manuscript by Martha K Hall, Griffith Genealogy: Wales, Flushing, Huntington, referenced in part one of this story, indicate that Daniel was a son of William Griffis and Abiah (Gates) Griffis and was born April 1, 1777 in Huntington, Suffolk county, Long Island. Both manuscripts also list the twelve children of William and Abiah Gates Griffis. One of Daniel’s brothers was Nathaniel Griffes. The manuscripts lack specific documentation on facts pertaining to the family but provide an initial starting point to corroborate the family trees that are depicted in the manuscripts.

- A family manuscript, the “Peets-Welsh manuscript”, and a manuscript by Martha K Hall, Griffith Genealogy: Wales, Flushing, Huntington, referenced in part one of this story, indicate that Daniel was a son of William Griffis and Abiah (Gates) Griffis and was born April 1, 1777 in Huntington, Suffolk county, Long Island. Both manuscripts also list the twelve children of William and Abiah Gates Griffis. One of Daniel’s brothers was Nathaniel Griffes, spelled ‘Griffith’ in the manuscripts.

- A review of the Federal and New York state census from 1810 through 1855 indicate that Daniel Griffis had six children: four sons and two daughters. Joel Griffis (1807) and William Gates Griffis (1807) were two of the three sons. The two other sons are not known. The two names of the daughters are Ruth and Sally.

- An Ensign (Ensinger) Griffis is found in various United States census in Mayfield and the Schenectady area. Based on the Will of Nathaniel Griffes, it is assumed he is his son.

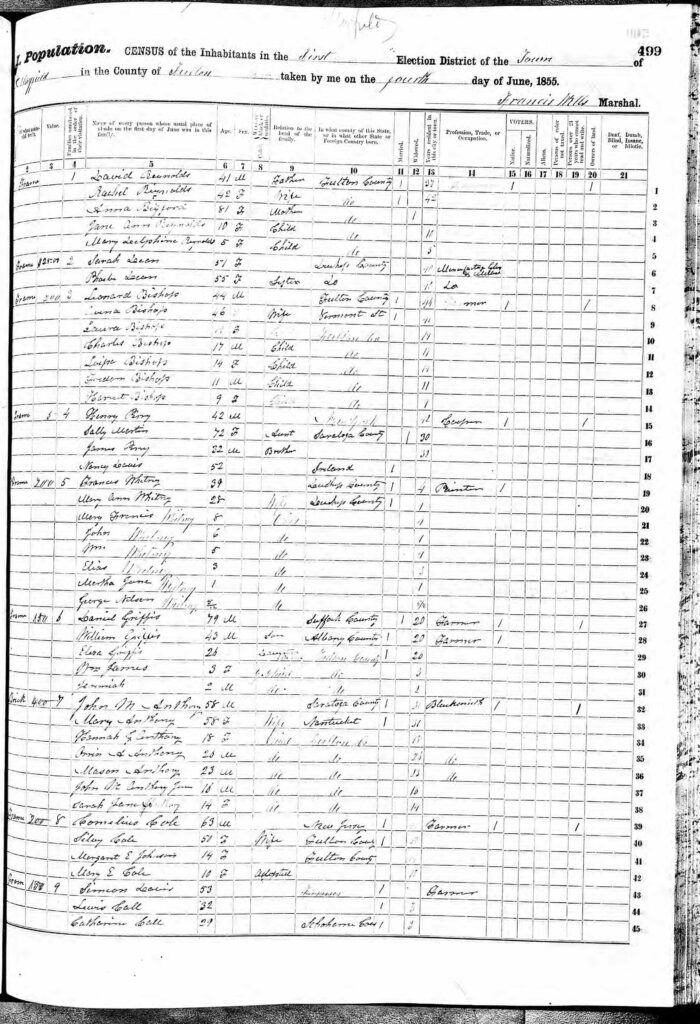

- In the 1855 New York state census, Daniel Griffis reported that he was born in Suffolk County in 1776, based on a reported age of 79. This is where William Griffis and Abiah Gates Griffis lived. In the same 1850 census, Daniel indicated he lived in Mayfield for 20 years.

- In the same 1855 census for the small town of Mayfield, New York, William G. Griffis and Joel Griffis indicate that they both were born in Albany county and had lived in the Mayfield, New York area for 20 years. This implies that Daniel, William and Joel moved to Mayfield about 1835 from the Albany-Schenectady area.

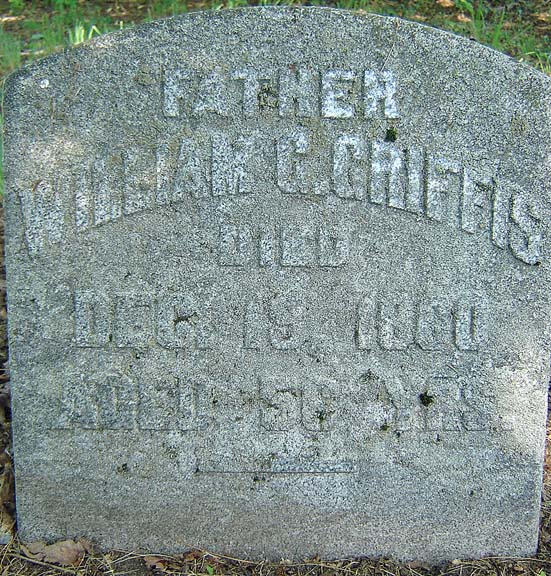

- William Griffis’ headstone in the Mayfield Riceville cemetery indicates his middle initial was “G”. I believe the “G” stood for Gates, a reference to his grandmother’s maiden name.

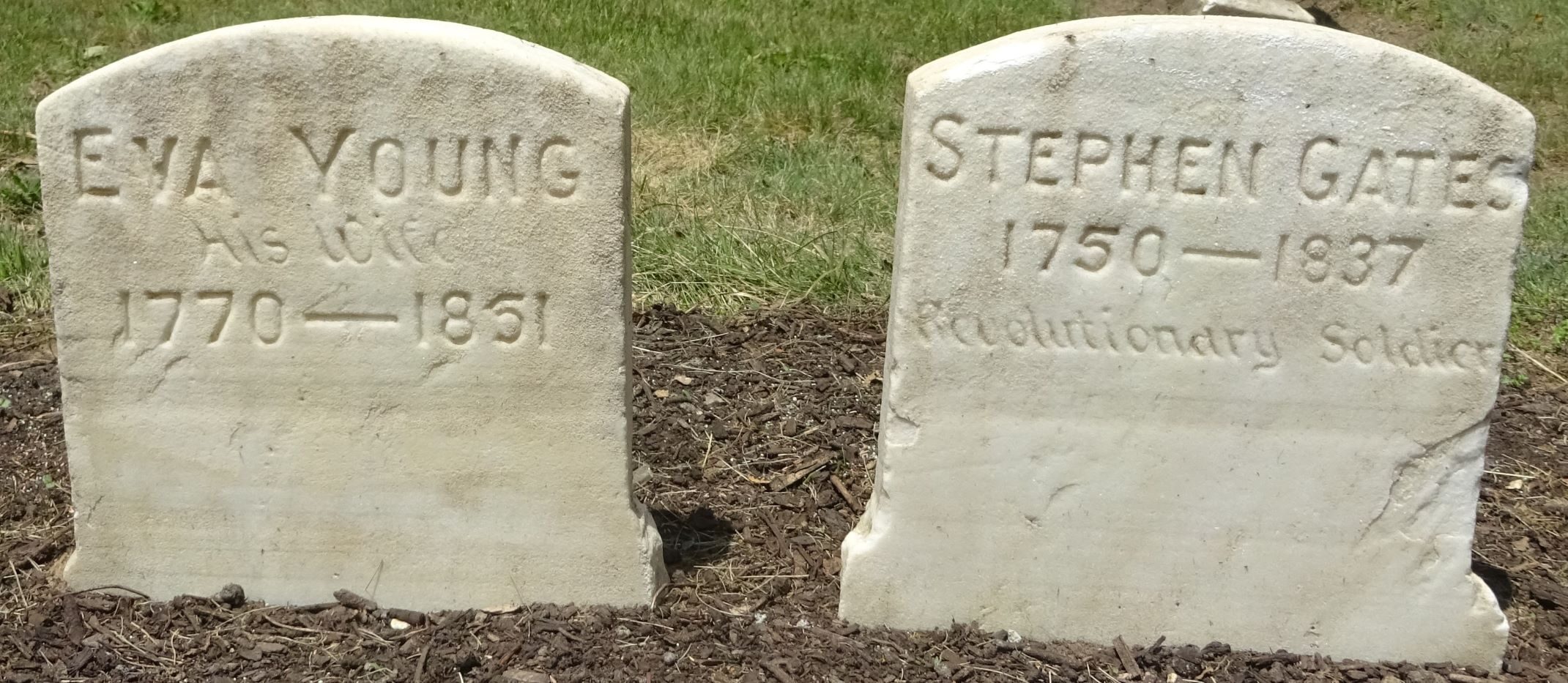

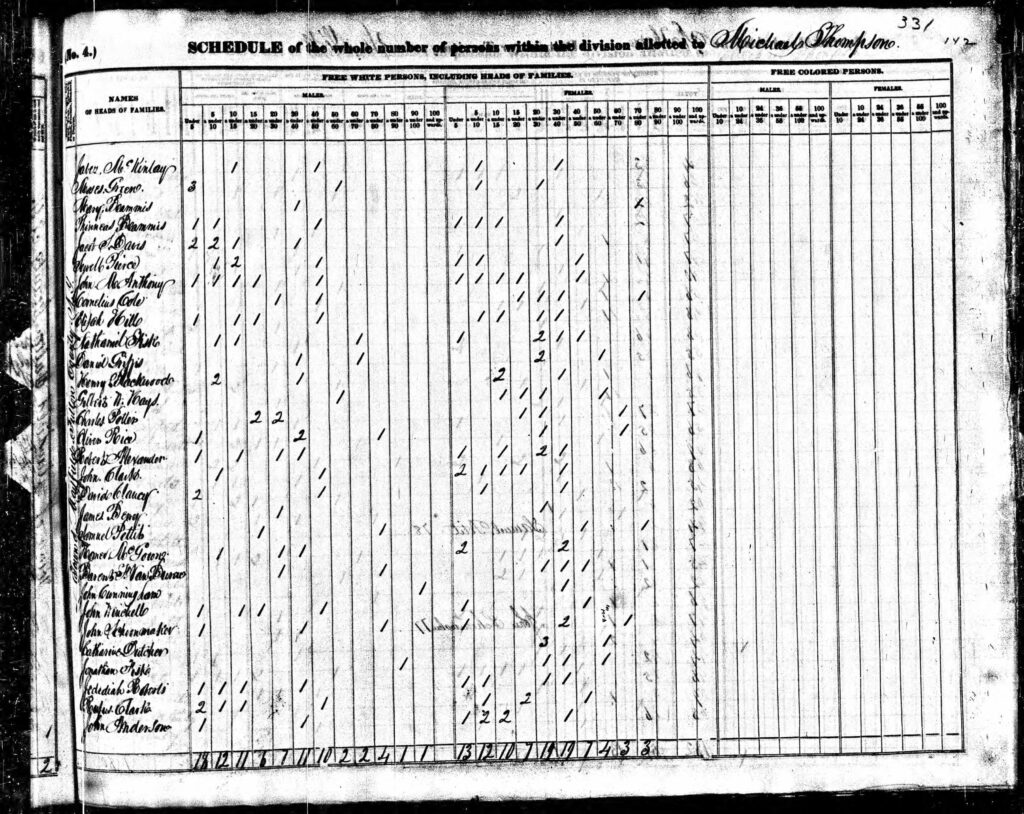

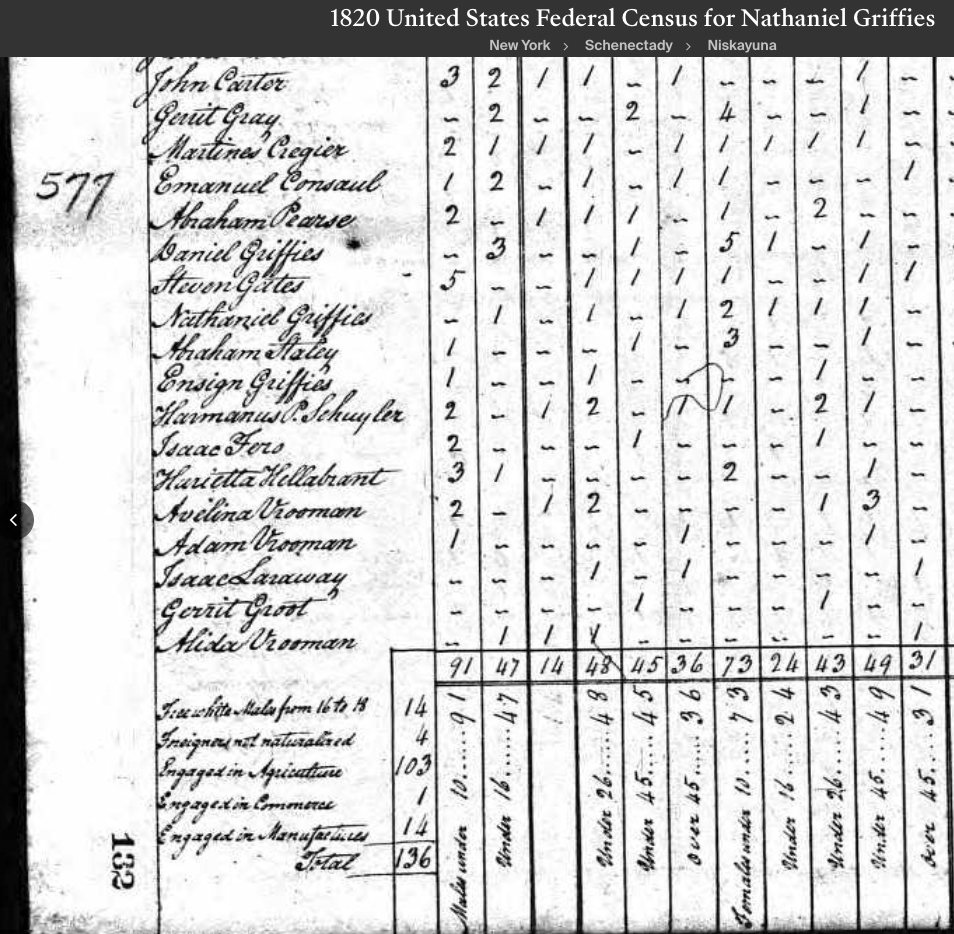

- The 1820 Federal Census for Niskayuna, Schenectady County, lists three ‘Griffies’ families in close proximity based on the census taker’s enumeration path. They were virtually next door neighbors. It is assumed the census enumerator misspelled their names. In addition, between two of the the ‘Griffies’ households, one headed by Daniel and another headed by Nathaniel, is a household headed by Steven Gates. Steven Gates (b. 1750 d. 1837) was Abiah Gates’ brother. Stephen Gates is Daniel and Nathaniel’s maternal uncle. Stephen Gates is found living in this area in the Federal Census in 1790 through 1830. There is also a household one house away from Nathaniel’s that is headed by an Ensign Griffies.

- The five families (households of Nathaniel Griffies, Daniel Griffis, Stephen Gates, Stephen’s son also named Stephen Gates, and Ensign Griffis) lived close to each other in the Niskayuna, Schenectady area in the early 1800’s. The snapshots of the census reveal an older Gates family, headed by Stephen Gates, surrounded by younger Griffis families and one of Stephen’s son, Stephen Gates. Nathaniel Griffes was about midway in age between Stephen Gates and his sons, Stephen Gates and Daniel W. Gates.

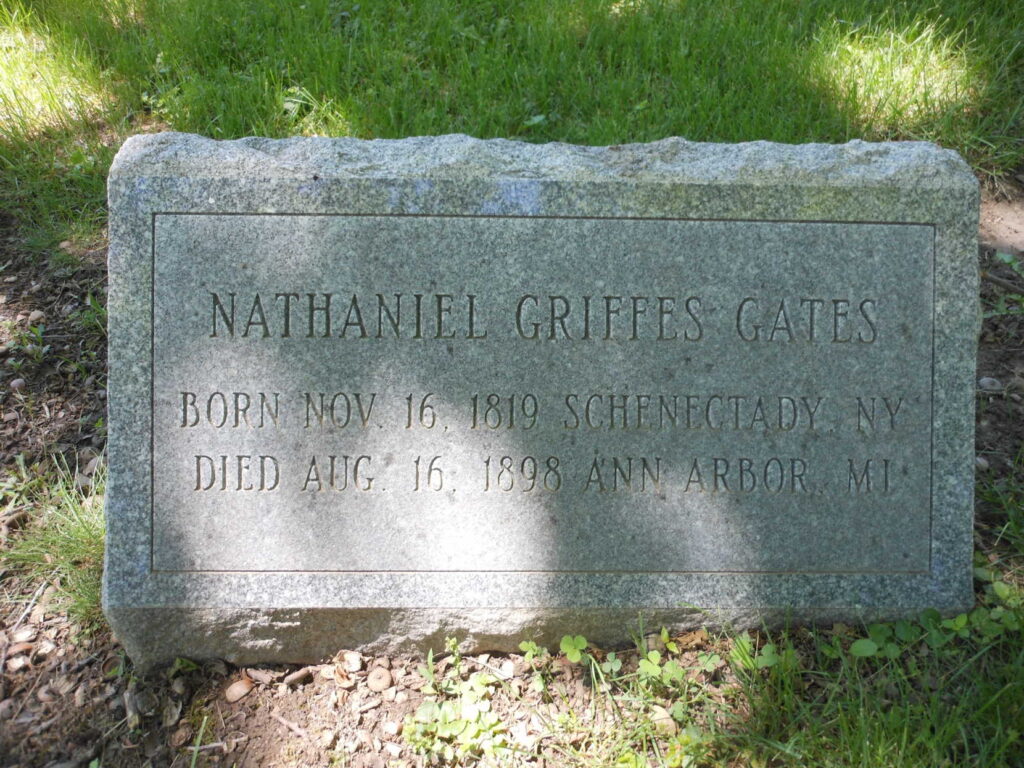

- The younger Stephen Gates named a son in honor of Nathaniel: Nathaniel Griffes Gates. Nathaniel Griffes named another son of Stephen Gates, Daniel W. Gates, as one of his executors of his will.

- Stephen Griffith, one of Nathaniel and Daniel’s older brothers, married Anna Ruland, who was a maternal first cousin. Anna Ruland’s mother was Naomi Gates, sister of Abiah Gates.

- The connections between Nathaniel Griffes, Stephen Gates, and Daniel Gates were obviously based on mutual trust and affection between family members. Both families have many of their respective descendants buried in the Vale cemetery in Schenectady, New York.

The Griffis(es) and Gates Families of Niscayuna and Mayfield New York

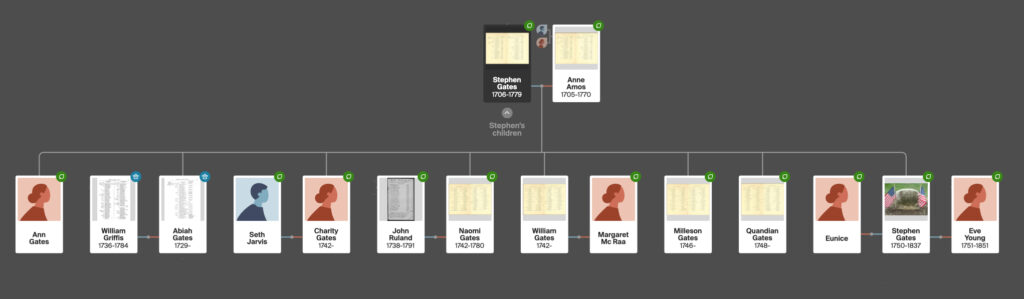

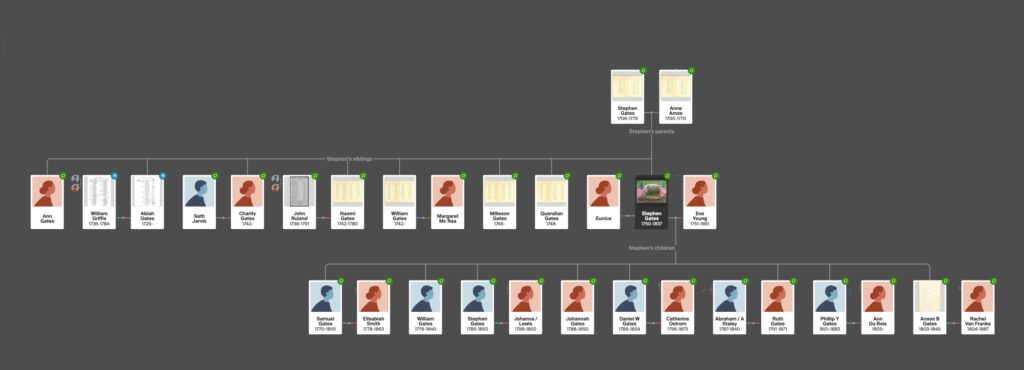

The path of discovery associated with reconstructing the Griffis(es) family was full of fits and starts, dead ends, recent discoveries, and continued unanswered questions. The following represent the family trees of the key families that can be traced back to William Griffis(th) who lived in Huntington, Long Island in the 1700’s.

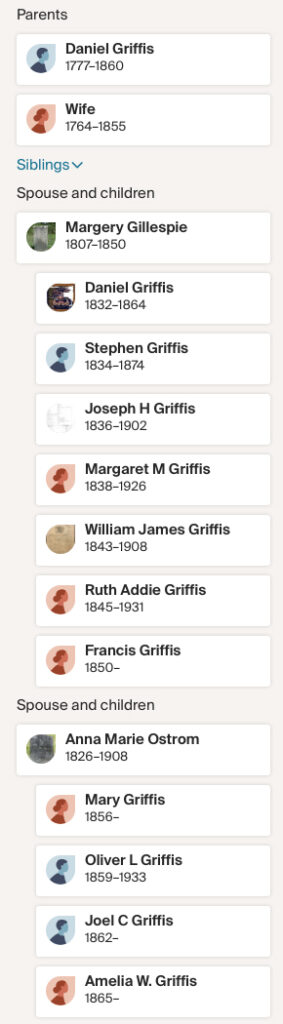

Based on a review of available historical records, Daniel Griffis, the great grand father of Harold Griffis, had four sons and two daughters. Two sons are not known but documented in the household in U.S. censuses.

It appears that Daniel had one older son and three sons that were closer in age. He had a daughter, Ruth, that was born close in age to the oldest son and a younger daughter that was born when the rest of the siblings were older. See the family tree below (click the image for larger view).

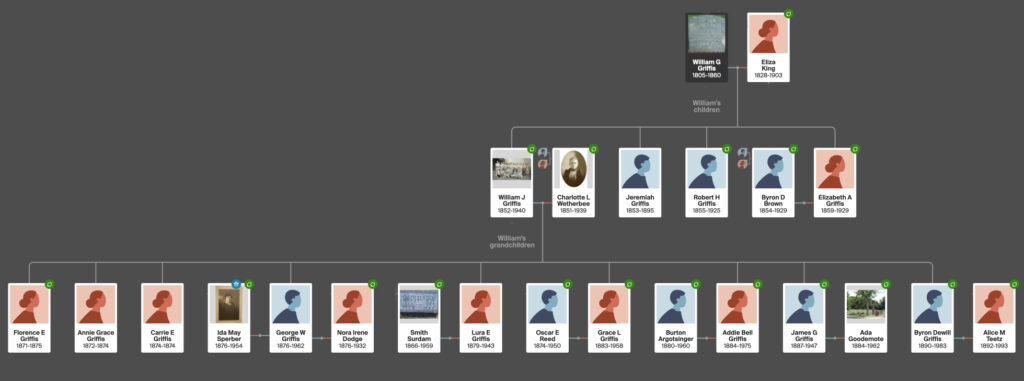

One of the two sons of Daniel Griffis that can be identified is William G. Griffis (1805 – 1860) William had four children. The oldest was William James Griffis (1852 – 1940). See family tree below (click on image for larger view).

William J. Griffis had a large family of nine children. His three oldest children, Florence (4 years old), Annie (age 2) and Carrie ( less then 1), tragically died of an illness, possibly Cholera. [2] His fourth oldest, George William Griffis (1872 – 1960), had one child, Edith Mae Griffis. George’s wife, Nora Irene Dodge (1901 – 1950), died in 1932. A widower, George married his second cousin’s wife who was a widow, Ida Mae Sperber Griffis. Ida originally married Charles Arther Griffis (1877- 1926) who was the father of Harold Griffis. Hence, an interesting connection between the family lines of William G Griffis and Joel Griffis.

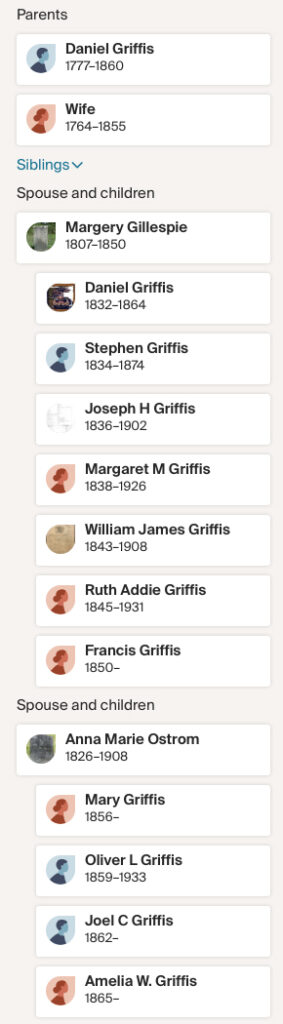

The other son of Daniel Griffis, Joel Griffis (1807 – 1882), had seven children with his first wife who died in 1850. He married a second time and had four additional children. In his first family, he had four sons and three daughters. One of the sons, William James Griffis (1843 – 1908), is the father of Charles Griffis and the grandfather of Harold Griffis.

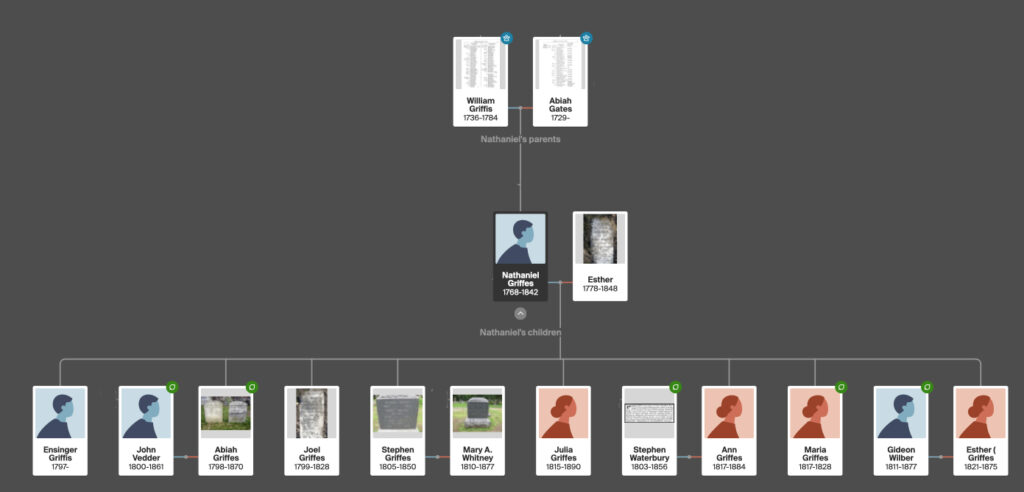

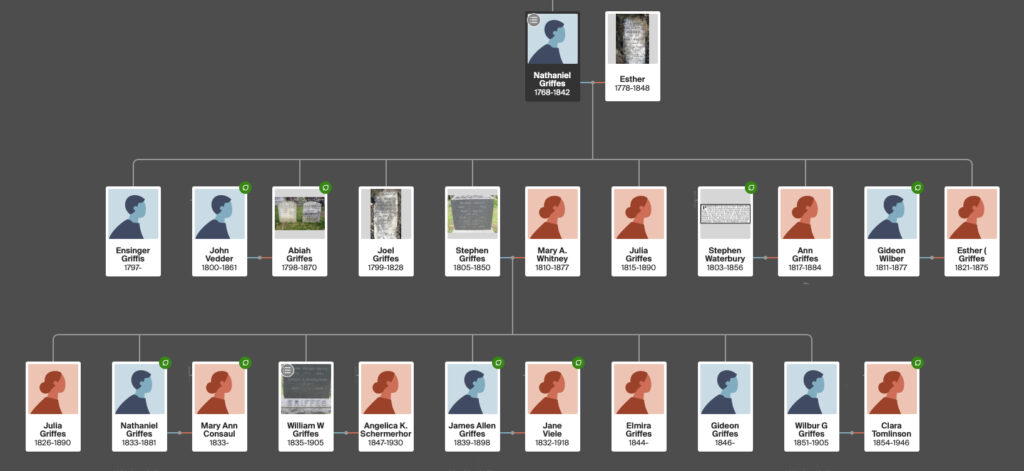

As indicated in the first part of this story, Daniel Griffis had 11 siblings. One of Daniel’s brothers was Nathaniel Griffes. While his name was spelled differently in various sources, Nathaniel’s grave and Will have his surname spelled as ‘Griffes’. Nathaniel Griffes was the sixth child of William Griffis. Nathaniel spent most of his life in the Schenectady, Niscayuna, Watervliet area of New York. In the early years of his life, Daniel Griffis also spent time in this area near his brother and their uncle Stephen Gates.

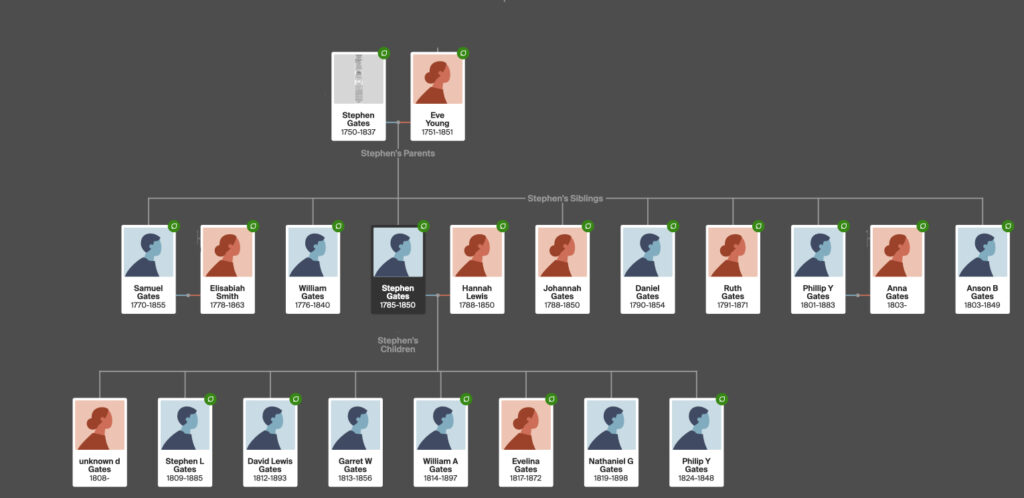

The following is a depiction of the family tree for Nathaniel Griffes (click image for larger view).

The following is a list of individuals in Nathaniel’s family.

Another important family that provides additional corroborating documentation of the linkage between Daniel Griffis and his father William Griffis is the Gates family. Nathaniel and Daniels’ mother, Abiah Gates had seven siblings. See the family tree below (click on image for larger view). Two of those siblings provide corroborating evidence of the ties between the two families. Abiah’s younger sister, Naomi Gates, married John Ruland. They had nine children, the seventh child Nancy (Anna) Ruland married Nathaniel and Daniel’s brother Stephen Griffith. The other is Stephen Gates Junior, the youngest of the eight siblings. After fighting in the revolutionary war, Stephen settled in the Niscayuna, New York area and lived the remainder of this life in the area.

During the 1820’s and 1830’s, the families of Daniel Griffis, Nathaniel Griffes, Ensign Griffis, Stephen Gates Junior lived close to each other. In addition, Stephen Gates’ sons Stephen and Daniel W. Gates were close family friends to Nathaniel Griffes. The following family tree depicts the family of Stephen Gates and his brothers and sisters (click on image for larger view).

Tracing Back to William Griffis in Huntington, New York

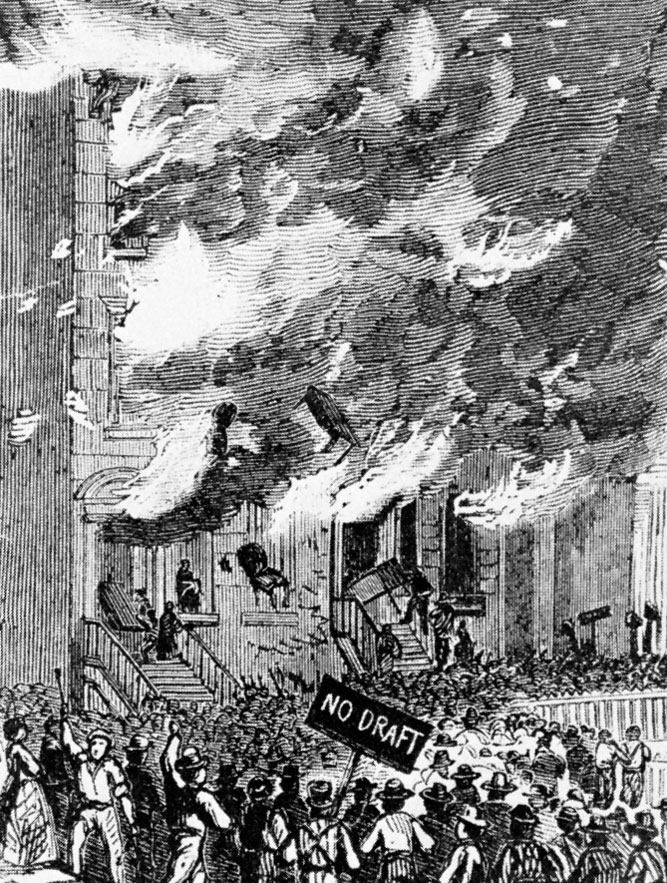

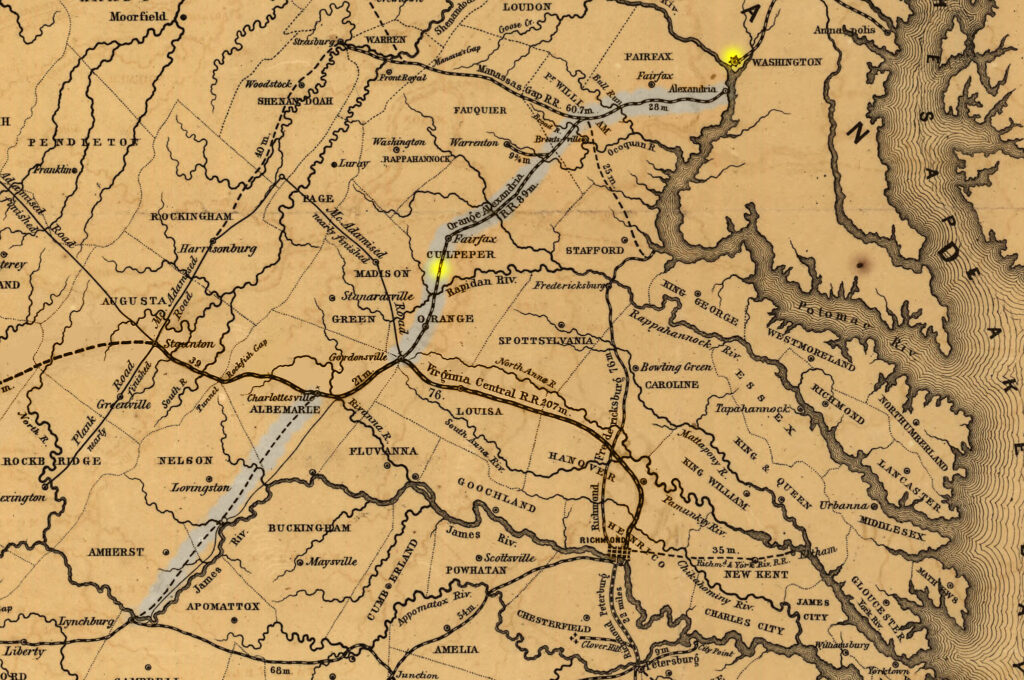

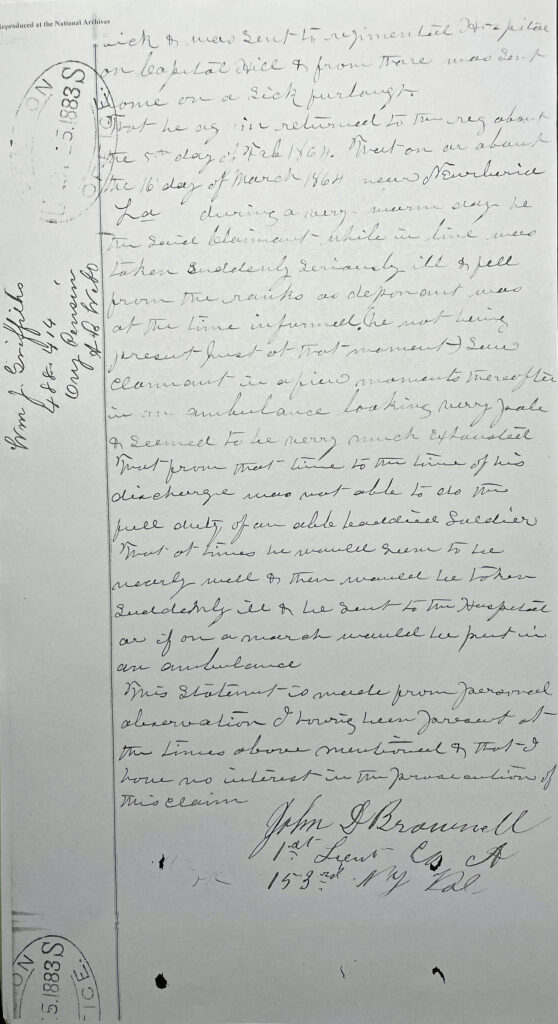

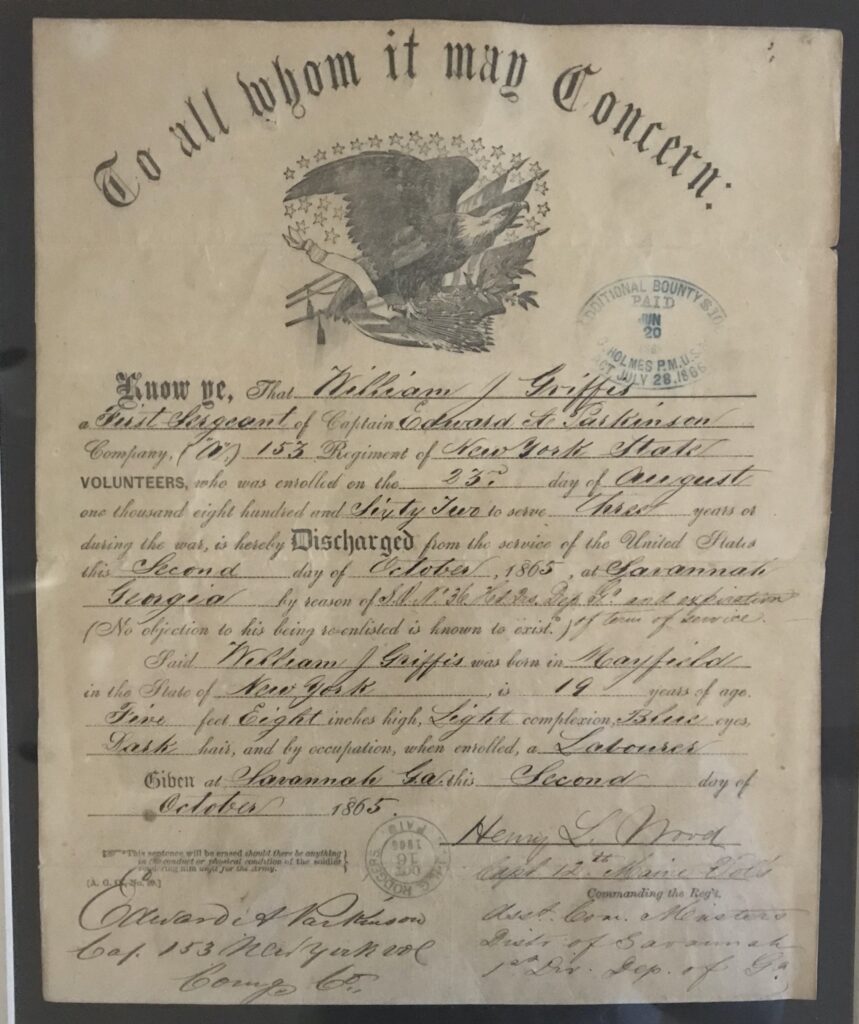

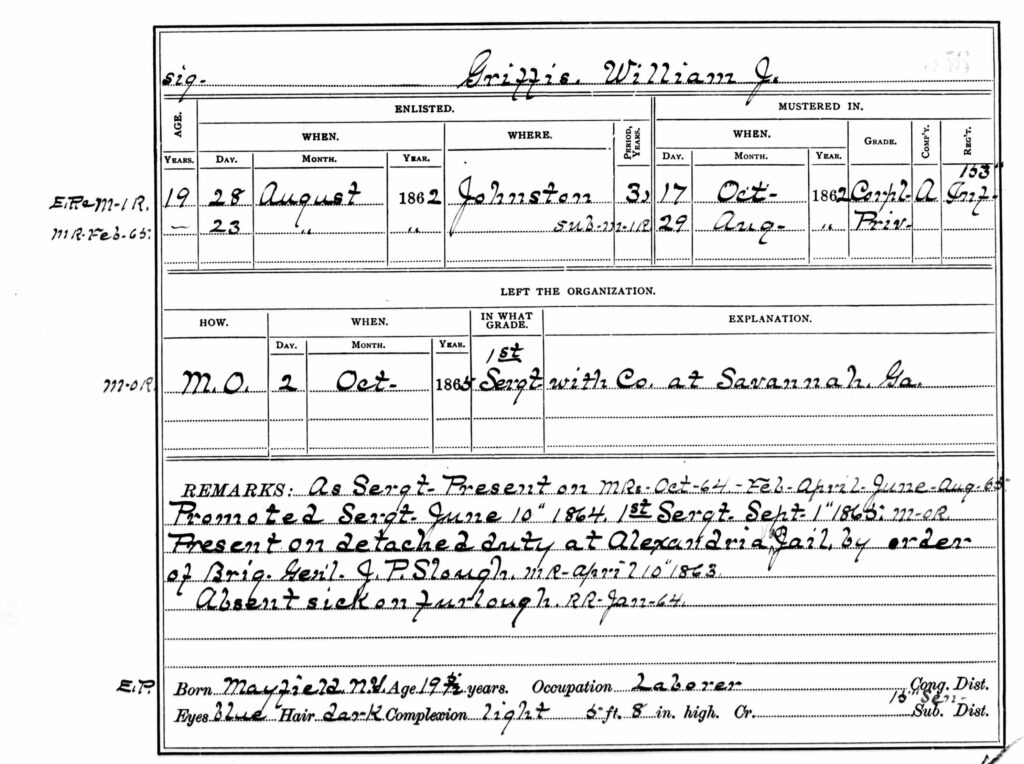

My path to discovering William Griffis(th) of Huntington, New York started in the small town of Mayfield, New York. Our family had the original copy of the one page discharge paper for William James Griffis from the Civil War (image below). The one page document indicated that he was born in Mayfield, New York. He was purportedly 19 years old at the time of his discharge which implied he was born around 1846.

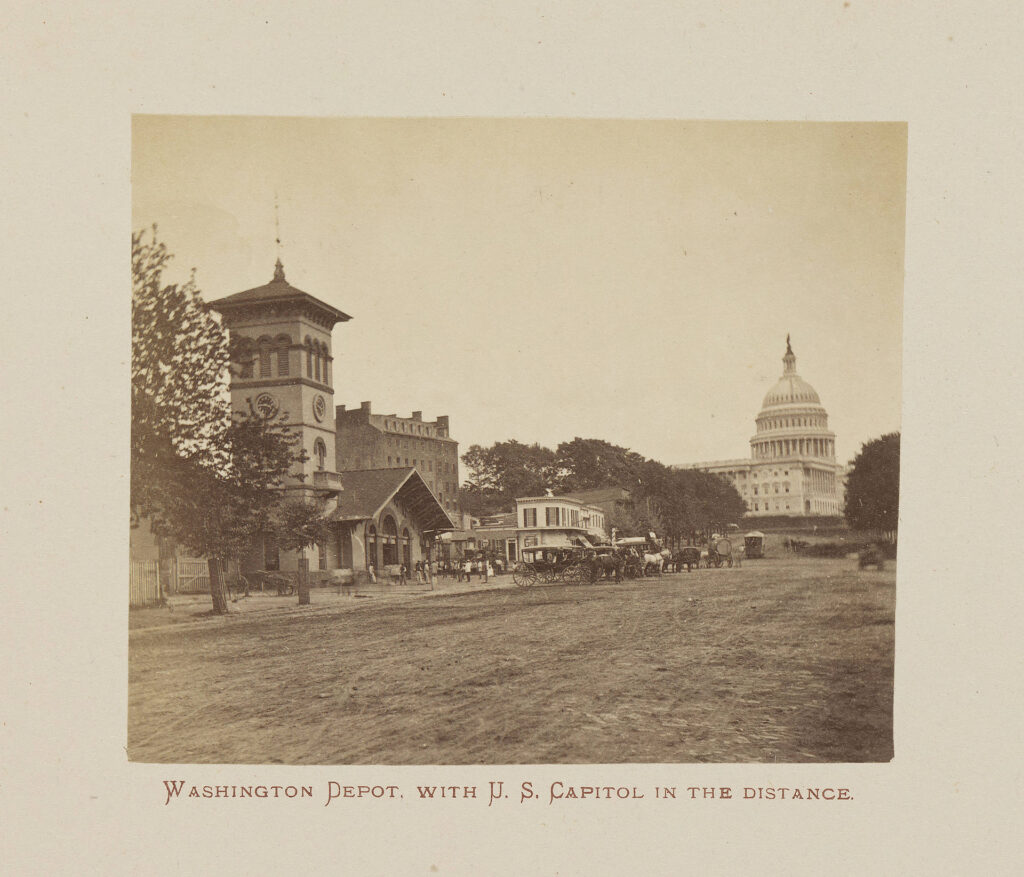

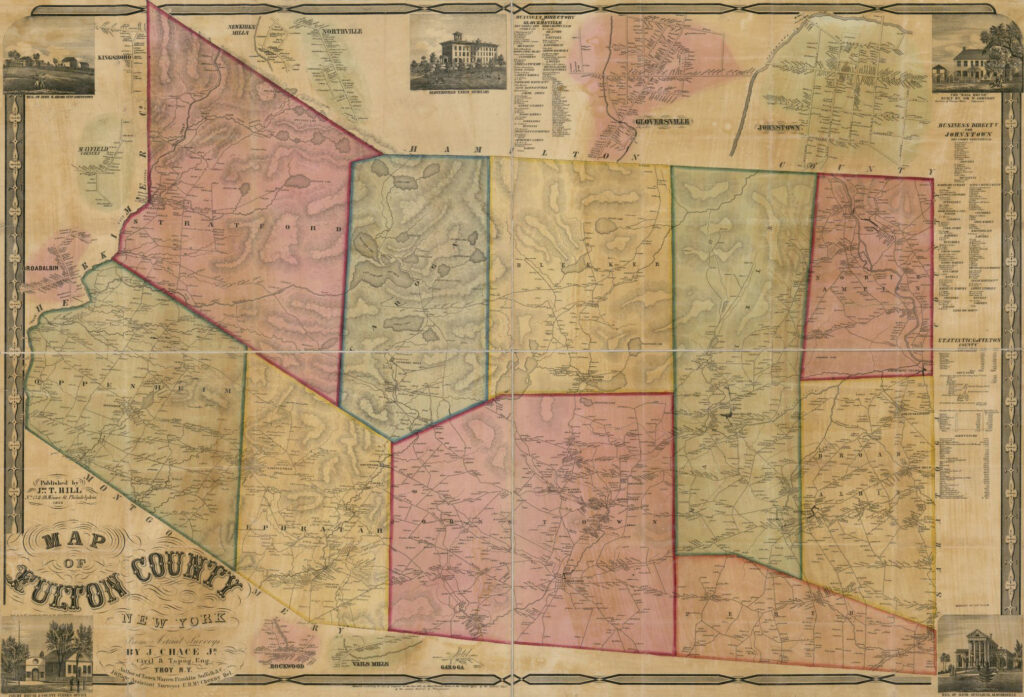

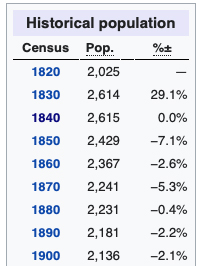

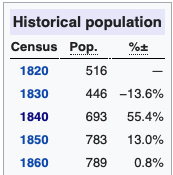

The land that is now the town of Mayfield was part of the Mayfield Patent of 1770. The town was established in 1793 from the town of Caughnawaga in Montgomery County before the formation of Fulton County in 1838. It was one of the first three such towns formed in the county. [3] [4]

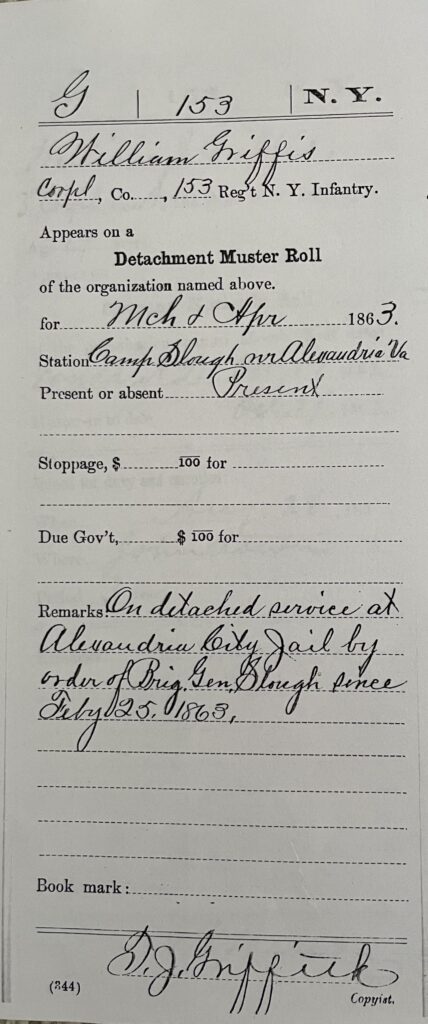

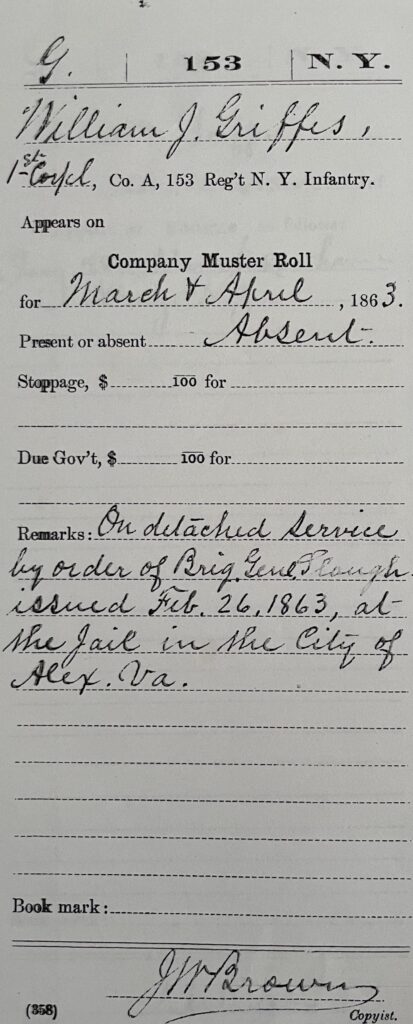

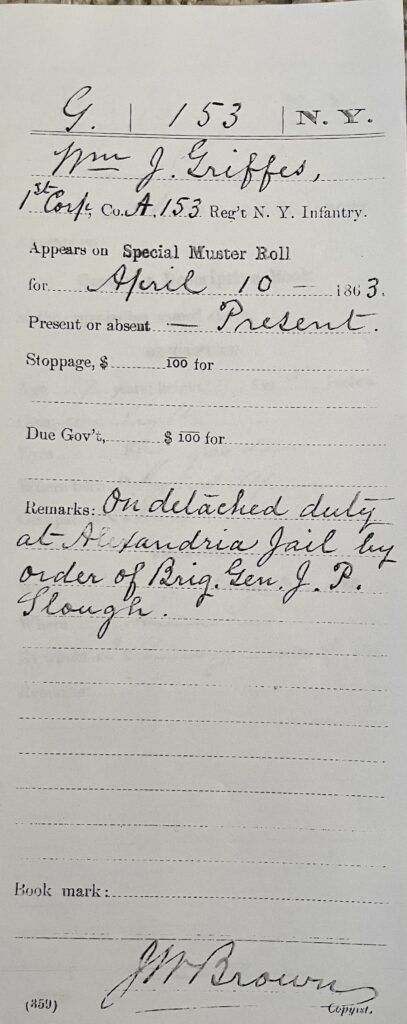

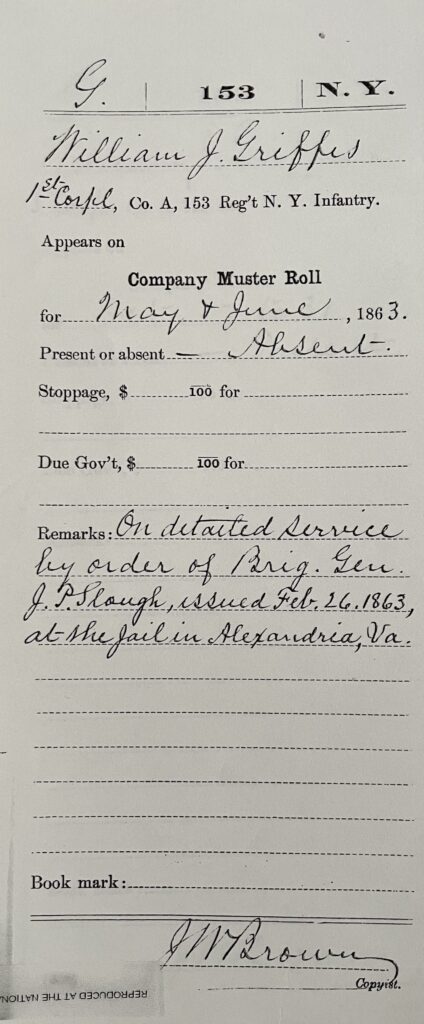

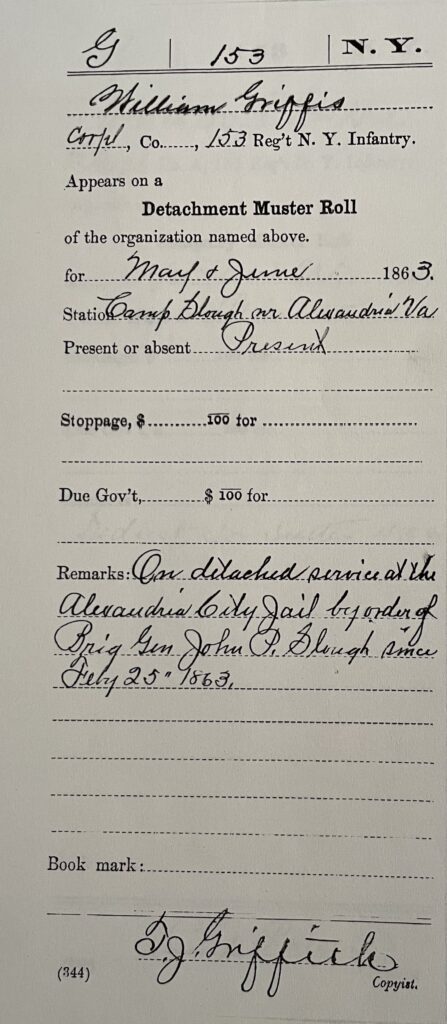

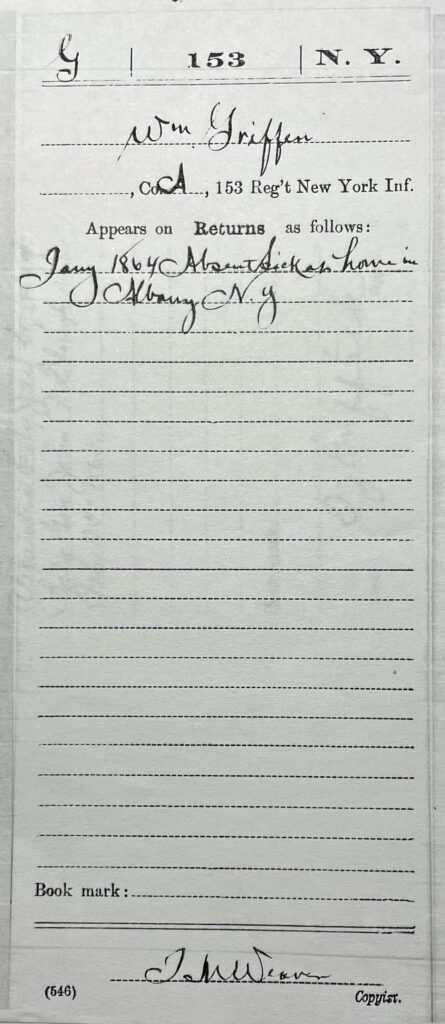

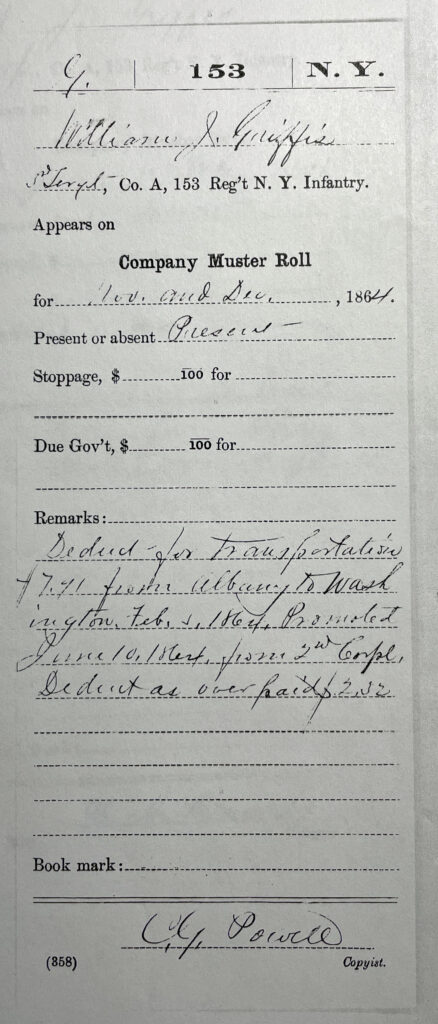

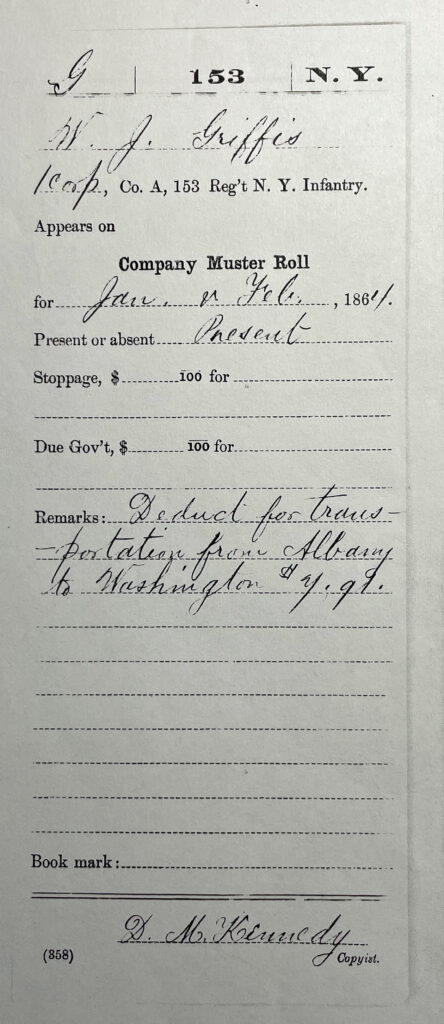

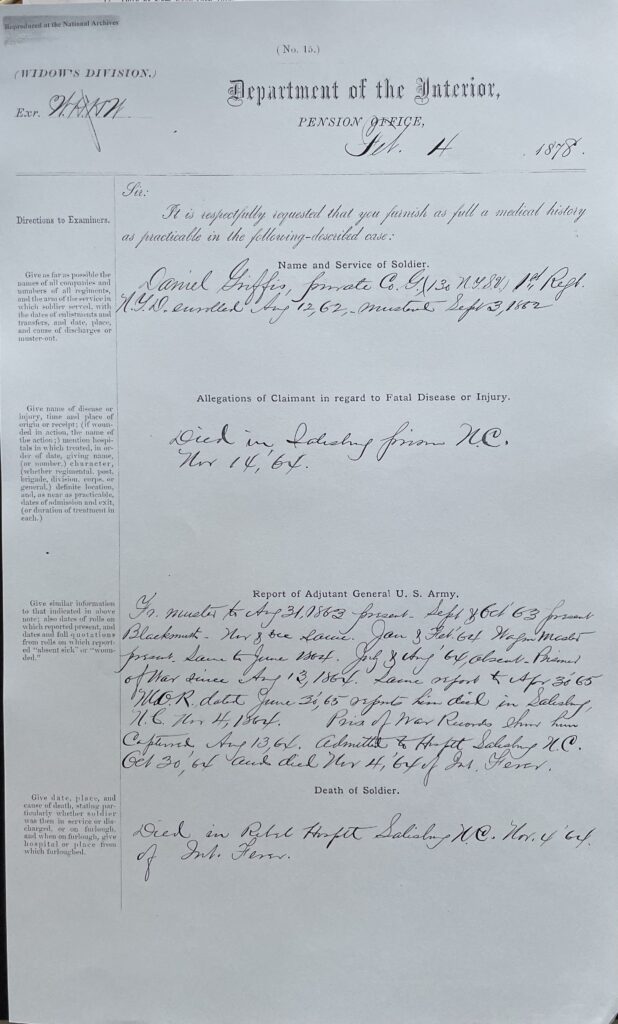

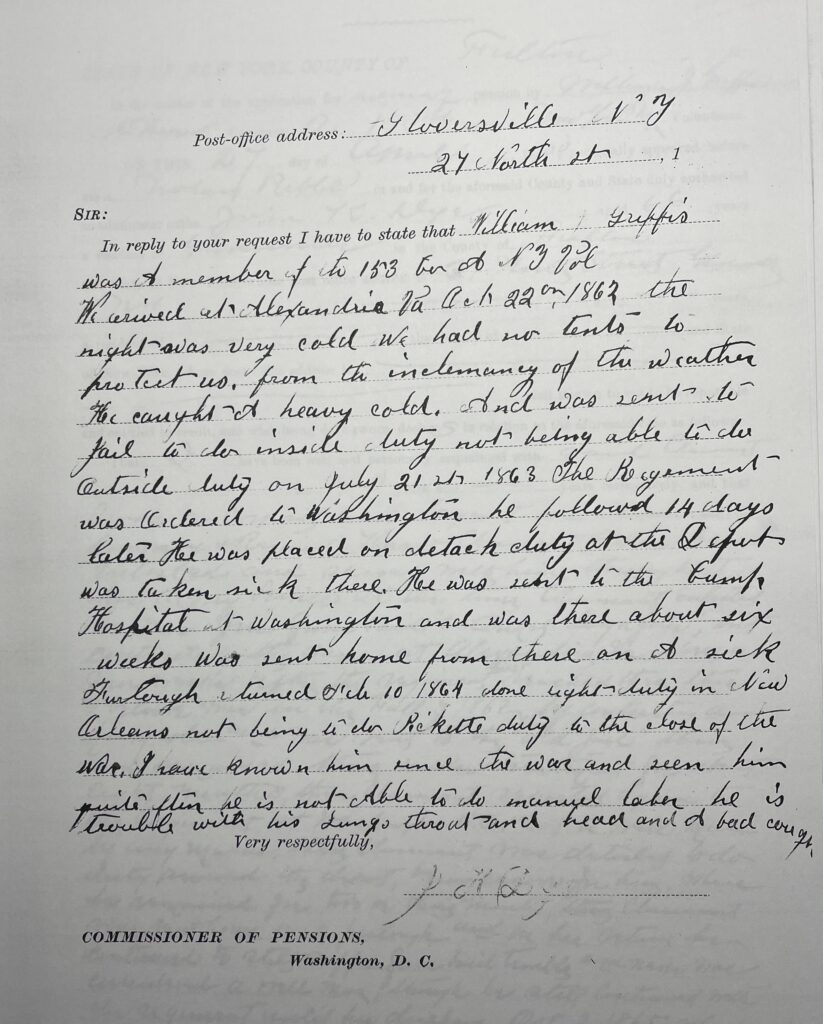

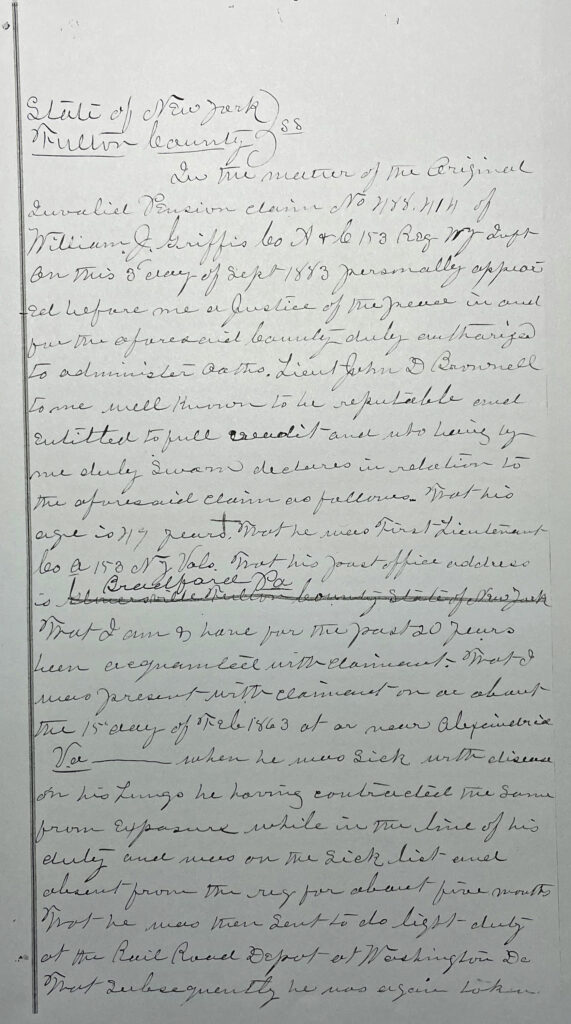

My subsequent research on William J Griffis revealed he may have been 22 when he was discharged from the war. William mustered into service in Johnstown, New York, a short distance to the west of Mayfield, October 17, 1862 for the ‘standard’ three year enlistment term in the New York 153rd Infantry Volunteers, Company “A”. His age was listed as 19 in 1862 (Image 2 below). If he was 19 at the time of his discharge, he would have been 16 at the time of his enlistment. Correlating information from military and pension files, William’s birth date was March 14, 1843. William as actually 19 at the time he enlisted. [6]

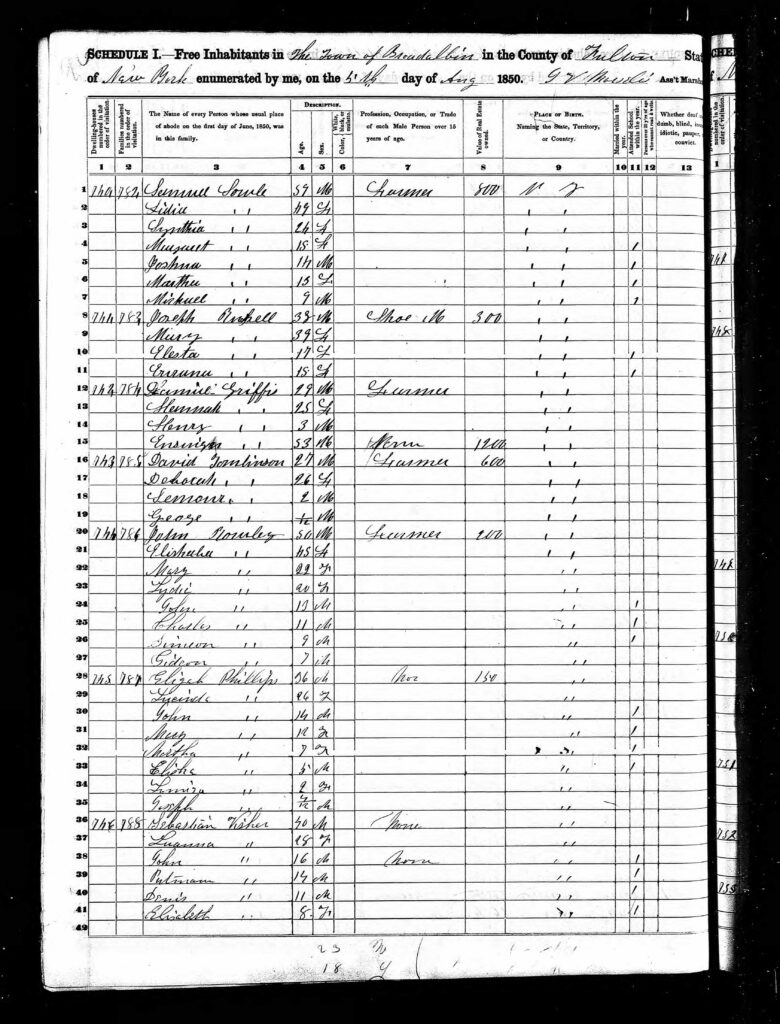

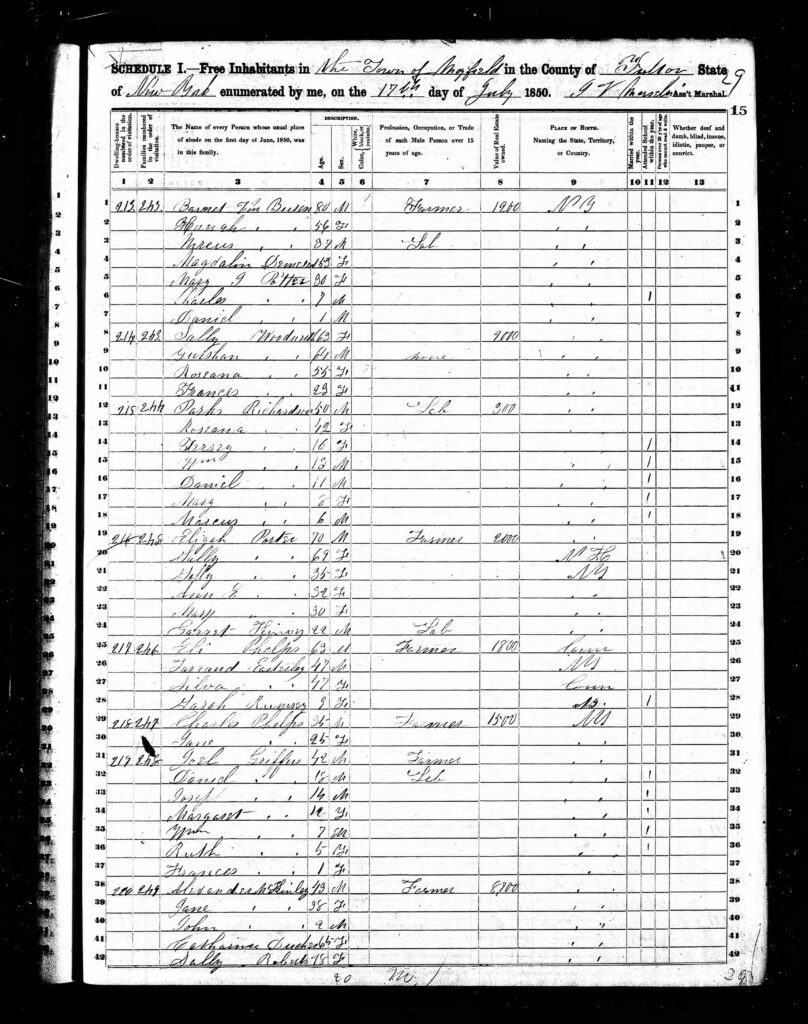

Based on researching local New York county records, the original New York Census [7] and reviewing Federal census documents, I was able to locate four Griffis families that lived in the Mayfield / Broadalbin, New York area starting in the 1840’s through the turn of the 18th century and onward. The heads of the four family households were Daniel Griffis, William Griffis, Joel Griffis and Ensinger Griffis. Depending on the year and type of census, these four individuals were reported in various family settings as described below.

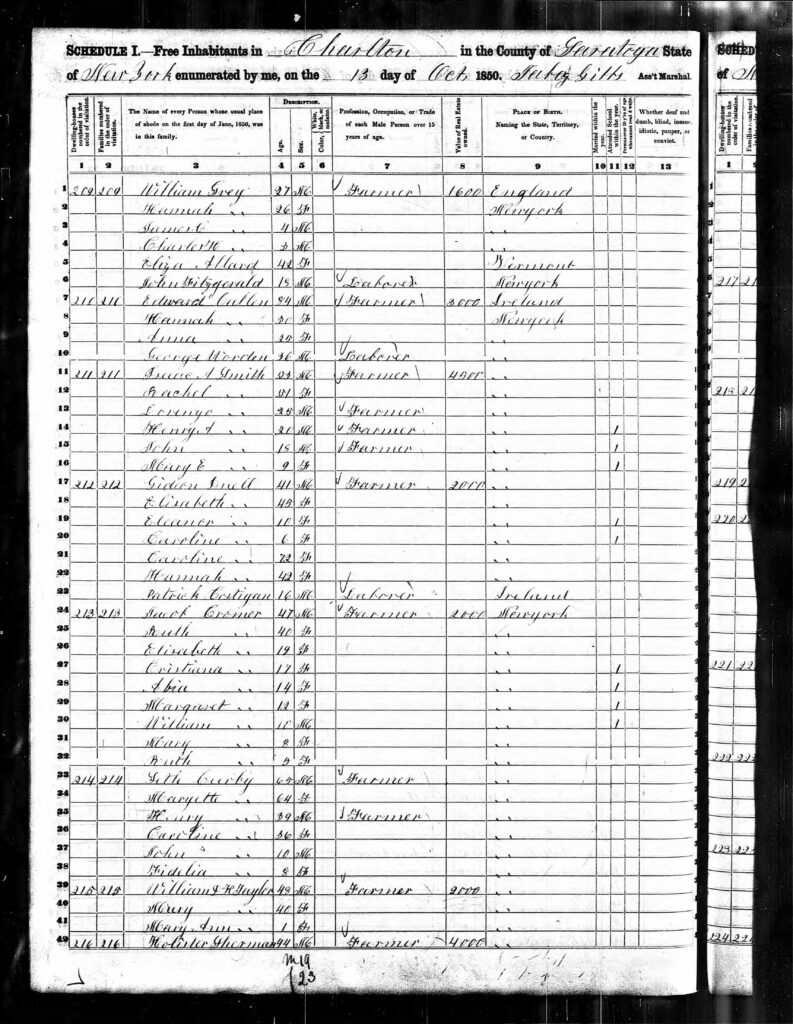

In the 1855 New York State Census (table one below), I was able to locate William in the household of Daniel Griffis.

Given the small size of Mayfield, it is highly likely that these four Griffis families were related. I had no direct corroboration but it gave me promising leads and, to date, unanswered questions about the exact configurations of each of the respective families over time. As stated in part one of this story, the Griffis name was an unusual spelling of the Griff(ith)(ths)(in)(ing)(ies) surname. I figured, based on corroborating information, they might be part of the same extended family.

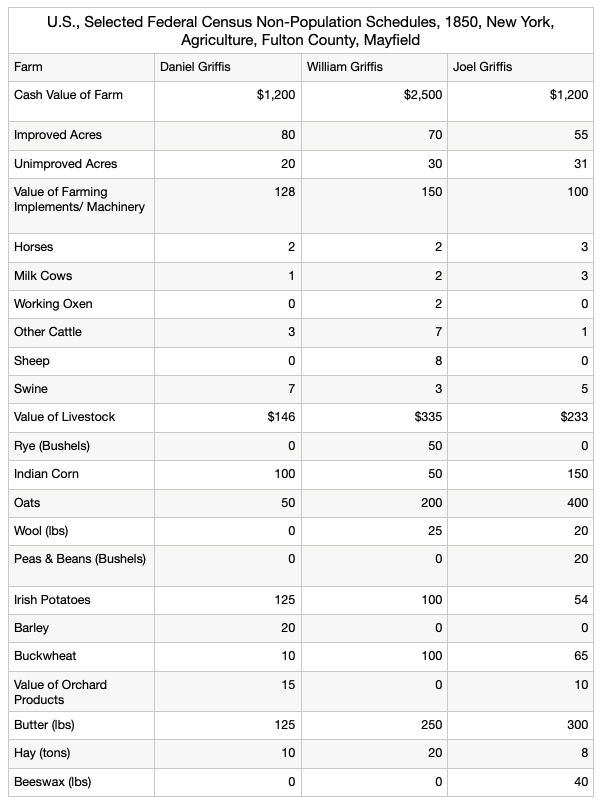

In 1850 the following three farms were found in the Agricultural Non-Population census for the Broadalbin and Mayfield, New York areas. The farms were not on contiguous parcels of land. They were fairly sizable farms, ranging from 80 to 100 acres. It is not known if each of the Griffis men owned the land or were managing the land. Based on how the census taker made his rounds, William and Joel’s farms were closer to each other in Mayfield. Information on their farms were ostensibly one page apart in the census (the number of columns of information associated with the agricultural census took up two pages to record) and were taken respectively on July 18th and 19th, 1850. Daniel’s farm was a bit further off in Broadalbin. The information on his farm was found on page 223-224 and the census taker visited his farm on August 3rd, 1850. Evidently, the census taker missed capturing information on Ensinger Griffis’ farm in Broadalbin.

Ensinger (born 1797) appears in the 1850 census as head of a household along with his son Samuel Griffis (born 1821), Samuel’s wife Hannah Griffis (born 1825), and his grandson Henry Griffis (born 1857). The census lists the value of the real estate next to Ensinger’s name, who owned the farmland, at $1,200. [8] Given the similar value of his farm compared with farms of Daniel and Joel (above), it is conceivable he had a similar sized farm. Depending on the census, the households were located in Mayfield or Broadalbin, which is contiguous to and east of Mayfield.

“Broadalbin was created from the towns of Johnstown and Mayfield in 1793, before Fulton County was formed. In 1799, part of Broadalbin was used to form the town of Northampton. Broadalbin lost the southern part of the town in 1842 to form Perth. When the Great Sacandaga Lake was created in 1930, some of the town’s land was covered with water, including the Sacondaga Vlaie, a broad expanse of marshy land.” [9]

Census Taking and Farm Households in the 1800’s

One must recognize and appreciate the act of taking a census when researching family history. From a simple behavioral viewpoint, the act of census taking is a social process similar to a salesperson knocking on a door. It involves an element of chance and the probability of getting answers, reliable answers. Presumably, census takers were known in their respective communities, increasing the likelihood of gaining acceptance and obtaining reliable information based on trust. It involves the dynamic of an individual moving up and down rural roads, knocking on doors, having people hopefully coming to the door or meeting the census taker on the farm property and receptively allowing the census taker to ask intrusive questions, taking precious time from the farmer to provide information to simple direct questions. The active process of census taking also brought to bear the issues of writing what one heard when asking questions and recording information in the best penmanship they have and hopefully accurately transcribing what they heard.

“The decennial census has always required a large workforce to visit and collect data from households. Between 1790 to 1870, the duty of collecting census data fell upon the U.S. Marshals. A March 3, 1879 act replaced the U.S. Marshals with specially hired and trained census-takers to conduct the 1880 and subsequent censuses.

“During the early censuses, U.S. Marshalls (sic) received little training or instruction on how to collect census data. In fact, it was not until 1830 that marshals even received printed schedules on which to record households’ responses. The marshalls (sic) often received limited instruction from the census acts passed prior to each census.“[10]

While each census had their specific list of questions to be answered, its reference point was a domicile, a home, a farm. It descriptively chronicles who lived in that domicile without regard to family kinship. By virtue of the census being purely descriptive, it can provide puzzling results when one is viewing a house or farm through the lens of a perceived family structure. Sometimes things do not line up in terms of what one anticipates seeing in terms of family structure.

Coupled with the social process of census taking, viewing the composition of a given family in a rural community needs to be viewed in a social and historical context of what families faced as farmers in the 1800’s.

Family relationships in the farm have important implications on production decisions, such as the choice of crops, the organization of family labour and its allocation to different tasks, management of farm land and other assets, and questions of inheritance. …(T)he nature of the farm business cannot be understood without reference to the family that operates it. Factors such as number, age and gender composition of the household play an important role in labour divisions and management decisions. [11]

The composition of a farm household may change due to the economic demands of farm production and the ability of family members being able to work. As family members get older, a younger generation of family members may move from one home or farm to another to assume different roles of managing the farm. I believe that this happened with the Griffis families in the Mayfield area and the Griffis, Griffes, and Gates families in the Niscayuna area of New York state.

By visually scanning the rows of families tabulated in the census pages of the state and Federal censuses, you could trace the census takers route in documenting farms and homes within the town’s boundaries and determine the proximity of family members in separate households. In specific time periods, the Griffis families lived next to each other.

Each of the Federal and New York state censuses between 1830 and 1860 asked different questions and were taken at different time periods of the year. The New York state based census was taken in 1825, 1835, 1845, 1855, 1865, 1875, 1892, 1905, 1915, and 1925. The Federal census was taken every ten years, beginning in 1790 and onward. [12]

The information in the 1855 New York state based census is noteworthy. The information contained in the 1855 New York census helped with my tracing the Griffis families back from Mayfield to the Schenectady, New York area in the early 1800’s. It was the first to record the names of every individual in the household. It also asked about the relationship of each family member to the head of the household, something that was not asked in the federal census until 1880. The 1855 New York state census also provides the length of time that people had lived in their towns or cities as well as their state or country of origin—this is particularly helpful for tracing immigrant ancestors. If born in New York State, the county of birth was noted, which is helpful for tracing migration within New York State.

In the 1855 New York State census, the census enumerator documented that Daniel Griffis lived in Fulton country for 20 years and was born in Suffolk County around 1777 which corroborates information found in Griffith Family manuscripts on the Griffith(s) family from Huntington, New York. [13]

The Griffis Families in 1850’s

While the 1850 agricultural census listed three farms under the Griffis name, the 1855 census only lists two Griffis households in the Mayfield area. Comparing the census data between 1850 and 1855 perhaps reflects the impact of the changing age and composition of individuals in the respective households based on the demands of managing farms. As Daniel was getting on in age, his sons Joel and William assisted Daniel in managing his farm. Joel’s children assisted Daniel at one point in 1850. In 1855, it appears that William, his son, may have consolidated his farm with Daniel’s or moved onto Daniel’s farm to assist.

One of the two Griffis households in the New York state census for Mayfield in 1855 contained the following individuals and related information. [14]

Table 1: Household of Daniel Griffis 1855

| Name | Age | Birth Year | Relation | County of Birth | Yrs Resident in Town |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel Griffis | 79 | 1776 | Head | Suffolk | 20 |

| William Griffis | 43 | 1812 | Son | Albany | 20 |

| Eliza Griffis | 26 | 1829 | Dau in Law | Fulton | 20 |

| William James Griffis | 3 | 1852 | Grandchild | Fulton | 3 |

| Jeremiah Griffis | 2 | 1853 | Grandchild | Fulton | 2 |

This is five years after the Federal agricultural census was taken. A lot can happen in five years. Table One reflects Daniel Griffis at almost 80 years old as the head of the household and his son, William, and his family residing with him. Daniel’s wife is not present. There is a grandson, William J Griffis, in the household but he is much younger than the Civil War veteran who would have been 12 at the time. Hence, there were two cousins named William James Griffis.

Nearly 80 years old, Daniel may have been involved with performing limited farm duties. He may also have had title to the land and therefore was considered as head of household. However, it would be logical to assume that William, his son, assumed the bulk of responsibilities in managing the farm.

Another Griffis household in the New York census of 1855 in Mayfield captured a snapshot of the household of Joel Griffis at a pivotal time in the life of his family (see Table Two). The census links William J. Griffis (born 1843) to his father, Joel Griffis, and to brothers and sisters. Joel’s wife is not present in the household.

There is a good chance that William Griffis, who is living with Daniel (Table One above) is Joel’s brother given the closeness of their ages. Also it is interesting to note that Daniel, his son William (Table One above), Eliza (William’s wife), Joel and Stephen (Joel’s son) all were resident’s in Mayfield for 20 years and were born in other counties which suggests that they moved from Albany County approximately in 1835. [15] Daniel the elder of the family was born in Suffolk county. [16]

Table 2: Household of Joel Griffis 1855

| Name | Age | Birth Year | Relation | County of Birth | Yrs Resident in Town |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joel Griffis | 47 | 1808 | Head | Albany | 20 |

| Stephen Griffis | 21 | 1834 | Child | Albany | 20 |

| Joseph H Griffis | 19 | 1836 | Child | Fulton | 19 |

| Margaret M Griffis | 17 | 1838 | Child | Fulton | 17 |

| William J Griffis | 12 | 1843 | Child | Fulton | 12 |

| Ruth A Griffis | 9 | 1846 | Child | Fulton | 9 |

Going back five years to 1850, we see a different picture. Reviewing the 1850 New York state Federal census in Mayfield revealed a puzzling composition for Daniel Griffis’ household. [17]

Table 3: Household of Daniel Griffis 1850

| Name | Age | Birth Year |

|---|---|---|

| Esther Griffis | 86 | 1764 |

| Daniel Griffis | 73 | 1777 |

| Sally Griffis | 24 | 1826 |

| Stephen Griffis | 16 | 1834 |

| Wm Griffis | — | — |

Daniel is still listed as the head of the household at the age of 73. He reported is birth year as 1777. There is an Esther Griffis, age 86 in the household. While is it possible on face value that this is Daniel’s wife, based on information in the 1840 Federal census (see below in the story), his wife would have been in her 60’s at this time. Daniel’s wife’s name is not known and presumably she died between 1840 and 1850. The 1850 state census did not list relation of family nor county of birth. Based on information in Griffith family manuscripts [18], Daniel had a sister named Esther who was born in 1773 and purportedly died in 1829. This Esther might have been his sister, if so, the Griffith manuscripts have an erroneous date of death for his sister.

What is equally puzzling are other Griffis family members listed in the household. There is a Sally Griffis (age 24) and Stephen Griffis (age 16) and a “Wm” Griffis with no age given.

Similar to the challenges of tracing female family members, Sally Griffis is an enigma. Prior to the twentieth century, it is typically difficult to locate and trace a woman. Most historical records have been created for and are about men, making it more challenging to research the women in a family. For example, property was usually listed under the man’s name, and men ran the majority of the businesses and controlled the government. Also, it was the man’s surname that was carried to the next generation by the children. In addition, few women left diaries or letters.[19]

Sally Griffis shows up only once in my research. I do not know who her parents are nor do I know if she got married. However, it appears that Sally was providing a helping hand in Daniel’s household. Based on the reporting of a census taker, we are given a ‘fact’ that she was born in 1826 and lived with Daniel Griffis along with Stephen Griffis in 1850. Sally could have been a daughter of Daniel. Daniel would have been been 49 when Sally was born. Sally could have possibly been a daughter of William if he was married before he married Eliza as a second wife. However, there is no evidence of this supposition. Another possibility is that Sally might have been a daughter of Joel Griffis. Joel would have been 18 when she was born. However, as indicated below, her birth would have been before he married his first wife, which could have happened but is unlikely. For the moment, I am assuming Sally was a daughter of Daniel Griffis.

The comparison of information related to Stephen Griffis (age 16) mentioned in Daniel’s household between the 1850 and 1855 New York census appear to corroborate that Stephen was a grandson, a son of Joel’s, and was living with his grandfather in 1850 to help on the farm and in 1855 returned to his father Joel’s household. The ‘Wm’ Griffis presumably is William Griffis, Daniel’s son. William’s son William James Griffis and son Jeremiah Griffis were born respectively in 1852 and 1853 (Table One) after the 1850 census.

The second Griffis family in the Federal census of 1950 reflects the household of Joel Griffis (see Table Four below). In 1855 (Table Two above) it appeared that Joel had five children with no wife listed: Stephen (born 1834), Joseph (b 1836), Margaret (b 1838), William (b 1843), and Ruth (1846).

The 1850 census revealed an older son Daniel (1832) who apparently left the household by 1855. the 1850 census also indicates the absence of a wife and the presence of another daughter Francis (born 1849). [20] It is believed that Francis passed away from a childhood illness since she is not found in the 1855 state census nor in the 1860 Federal census.

Table 4: Household of Joel Griffis 1850

| Name | Age | Birth Year |

|---|---|---|

| Joel Griffis | 42 | 1808 |

| Daniel Griffis | 18 | 1832 |

| Joseph Griffis | 14 | 1836 |

| Margaret Griffis | 12 | 1838 |

| Wm Griffis | 7 | 1843 |

| Ruth Griffis | 5 | 1845 |

| Francis Griffis | 1 | 1849 |

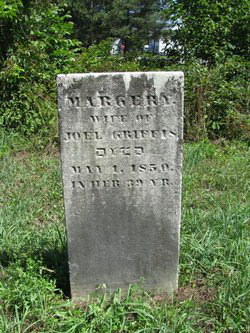

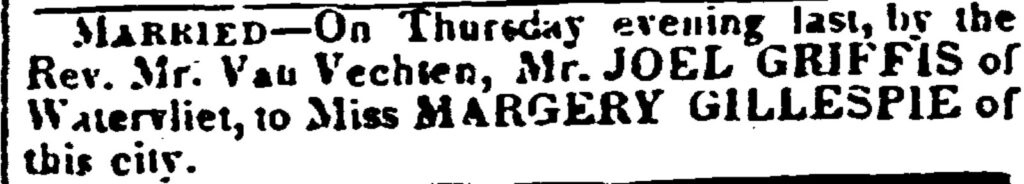

A review of available records associated with grave sites in the area indicate that at the age of 39, Margery, Joel’s wife, passed away on May 1st in 1850 [21]. It is not known what was the cause of death. Her youngest child, Francis, was born in 1849.

It is important to note that the census taker compiled the information on Joel’s house on July 17th, 1850. At that time, Joel, a recent widower of less than two months, undoubtably had his hands full with a household of six children ranging from Daniel at 18 to Francis at one year of age. All but Stephen were living with Joel. Stephen, at the age of 16, was living with his uncle William and grandfather. In the next five years before the 1855 census was taken, it appears that young Francis passed away.

Joel and Margery were married in Watervliet, New York in 1831. [22] This is consistent with the census reporting that Joel migrated from Schenectady /Albany County area to Fulton county around 1835. Also Joel and Margery had two sons prior to their move to Mayfield.

Before Margery passed away at the young age of 39, they had seven children: four sons and two daughters. Daniel was the oldest (born 1832), followed by Stephen (1834), Joseph H. (1836), Margaret Mary (1838), William James (1843), Ruth Addie (1845) and Francis (1850). Based on the birth locations of the children, it appears the family moved from the Schenectady, New York area to Mayfield, New York around 1835. This is based on statements to the census enumerator that they lived in Fulton county for 20 years in 1855. The two older sons were born in the Watervliet – Albany New York area while the remaining children were born in Fulton County where Mayfield is located. It appears that Joel and Margery along with other Griffis family members, notably his father Daniel Griffis (1777 – ), and brother William Griffis (1805- 1860) migrated westward from the Albany Schenectady area to the rural areas of Mayfield in 1835 to live life initially as farmers.

Joel Griffis married Anna Marie Ostrom after Margery Gillespie Griffis’ death, sometime before the birth of his eighth child, Mary Griffis, in 1856. Joel had three additional children with Marie. [23]

Although we are primarily tracing Daniel Griffis backward through various Federal and state census documents for the purpose of tracing the family surname, two other pieces of information are pertinent for tracing and linking the family surname. William Griffis died December 19, 1860 and was 56 years old. He was buried in the same cemetery as Joel’s wife Margery in Rice Cemetery, in Mayfield. [24] While the census documents did not indicate his date of birth, the headstone for William Griffis provides documentation of an approximate birth. In addition it provides his middle initial “G”. This is a corroborating clue of William’s connection to William and Abiah (Gates) Griffis. As indicated in the first part of the story, Gates is the surname of Daniel’s mother. I believe the middle name of William G. Griffis, who died in 1860, was Gates.

It is not absolutely certain that Joel and William are brothers. They could possibly be cousins. I am willing to hedge a bet that they were indeed brothers. If William was born around 1805, Joel was born around 1807, they conceivably could be brothers. Their proximity to each other in the Mayfield Broadalbin area, their help in managing farms in the 1850’s, and their collectively movement to Fulton county in the mid 1830’s also lends credence to their being siblings. In addition, Joel along with William’s wife Eliza, were executors in the probate process of William G. Griffis’ will when he died. [25]

The Griffis(es) families in the 1840’s: A Period of Change

The ability to trace family members in Federal and New York state census documents prior to the 1855 face an inherent challenge. While the New York state census provided more detailed information than the Federal census, the first three state censuses for New York (1825, 1835, and 1845) are difficult to access and largely unavailable online. Most records have been lost due to a 1911 fire in the Albany state capital. County clerks maintained duplicate copies for their counties and in some cases counties maintained copies of records from these first three censuses. Prior to 1880, the Federal census only recorded the name of the head of household. Individual members of a given household were counted in ordinal age categories (e.g. male aged 10 – 14, etc.).

I was able to rely on New York state census material in the 1850’s to locate individuals in the Griffis(es) family. However, working backward in time in the 1840’s, 1830’s, 1820’s, 1810’s, 1800’s and 1790’s, I was limited by finding heads of households and age group categories that changed every ten years. If one knew the birth dates of given family members from other sources, then one could compare the age distribution of family members within a given household to determine if specific individuals reflected the distribution of individuals within specific age group categories in a given census. [26]

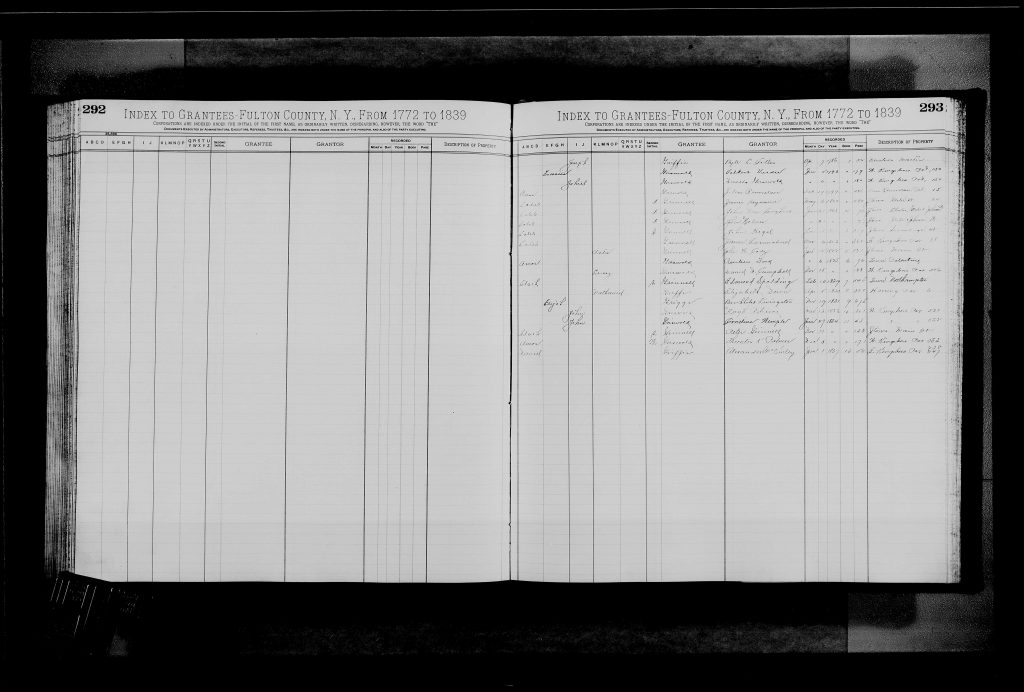

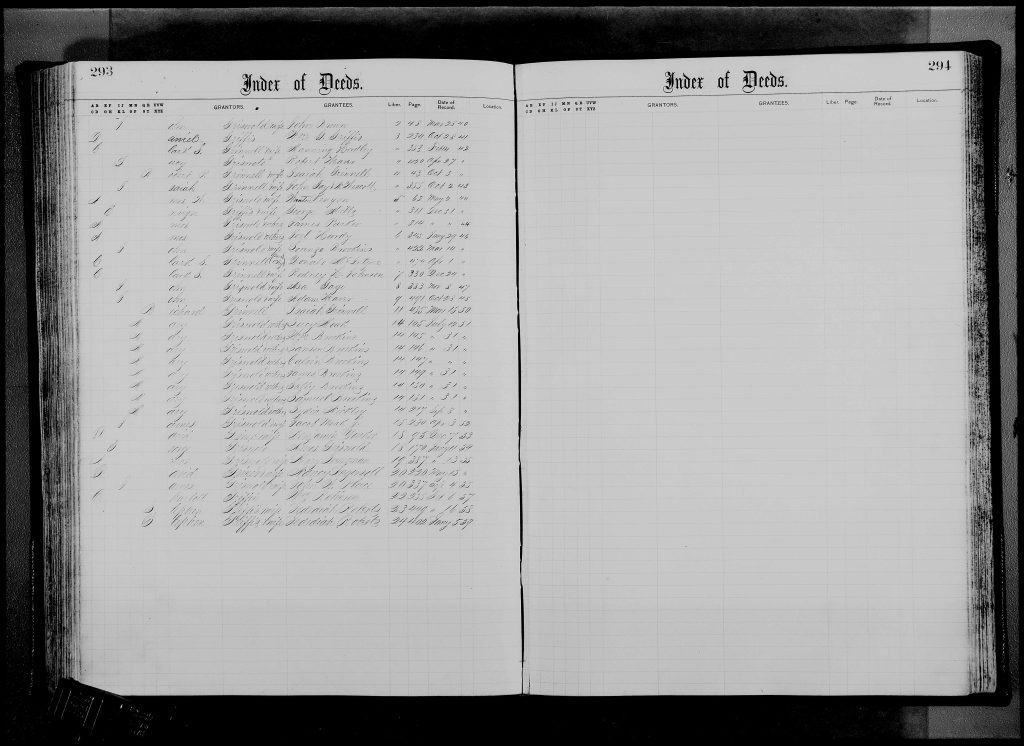

Based on the recent addition of digital land and property records from the New York Land Office and county courthouses [26a], records of a land acquisition by Daniel Griffis were discovered. The records include land grants, patents, deeds, and mortgages. This collection includes all counties except Franklin, Nassau, and Queens. A land assessment record was discovered that indicated Daniel Griffis acquired Land from Alexander M. McKinley on January 1, 1837 in Fulton County, New York. [26b] The land he acquired was in East Kingsboro, and consisted of two parcels: 238 and 247. We now know that Daniel owned land in Fulton in 1837. In 1841 Daniel transferred a parcel of land to his son William G. Griffis. [26c] It is interesting to note that on the same page of the Index to Deeds, it is recorded that the wife of Stephen Griffis transferred two parcels of land to Jedediah Robersons on February 6 1857 and Feb 16, 1858.

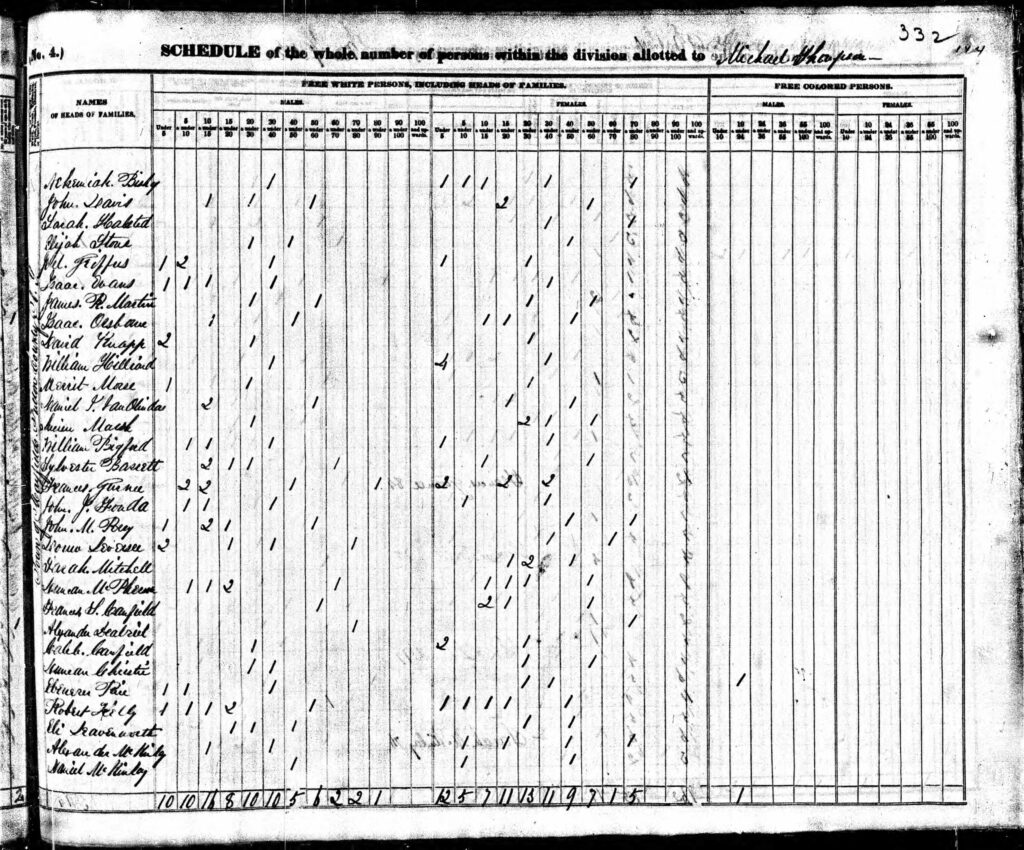

Based on a review of 1840 Federal census information, Daniel and his sons Joel and William moved away from the Schenectady, New York area and were living in Fulton County, New York. Ensign Griffes moved away to Carlton and is found in Saratoga County. Daniel’s older brother Nathaniel and his family as well as their maternal uncle’s family (Stephen Gates) continue to reside in Niscayuna, Schenectady county.

The following table summarizes the configuration of each household of Griffis(es) families based on the age group distributions found in the 1840 census. I have attempted to place names of known ancestors in various census categories. As you can see from reviewing the information in Table 5, there are a few inconsistencies.

Table 5: 1840 United States Census and Griffis(es) Households

| Head of Household | Age Category | No. | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nathaniel Griffes | Male 5-9 (Nathaniel 7 son of Stephen Griffes?) | 1 | Niscayuna, Schenectady, NY |

| Male 30-39 (son Stephen?) | 1 | ||

| Male 70-79 (Nathaniel Griffes) | 1 | ||

| Female 20-29 (Stephen’s wife Mary Witney?) | 1 | ||

| Female 60-69 (Esther Griffes) | 1 | ||

| Stephen Griffes? | Male < 5 (William 5, James 1) | 2 | |

| Male 20-29 (Stephen Griffes would have been 35) | 1 | ||

| Female 5-9 (Julia was born after 1826) | 1 | ||

| Female 20-29 (Stephen’s wife Mary Witney) | 1 | ||

| Ensign Griffis | Male 15-19 (son Samuel) | 1 | Charlton, Saratoga, NY |

| Make 40-49 (Ensign) | 1 | ||

| Female 15-19 (unknown daughter) | 1 | ||

| Female 40-49 (Ensigns Wife) | 1 | ||

| Daniel Griffis | Male 30-39 (son William) | 1 | Mayfield, Fulton, NY |

| Male 60-69 (Daniel) | 1 | ||

| Female 20-29 (unknown possibly a wife of son and a daughter) | 2 | ||

| Female 50-59 (Daniel’s wife) | 1 | ||

| Joel Griffis | Male < 5 (son Joseph Griffis) | 1 | Mayfield, Fulton, NY |

| Male 5-9 (sons Daniel Griffis & Stephen Griffis) | 2 | ||

| Male 30-39 (Joel) | 1 | ||

| Female < 5 (daughter Margaret) | 1 | ||

| Female 30-39 (Joel’s wife) | 1 |

In the Federal 1840 census, Joel and Margery’s family of six had four individuals engaged in agricultural work. There was one male under 5 (Joseph), two males 5 through 9 (Daniel and Stephen) and another male 30-39 (Joel)in the household. There was one female under 5 (daughter Margaret), 1 female between the ages of 20-29 (Margerie his first wife). [27]

Daniel Griffis is also found in the 1840 Federal Census in Mayfield. His household had five individuals, all were reported as being employed in agriculture. The household had one male between the ages of 30-40 (presumably William Griffis), a male between the ages of 60-70 (presumably Daniel), two females between the ages of 20-30 (not certain as to who they are which again raises the issue regarding Sally Griffis), and a female between the age of 50-60 (presumably Daniel’s wife). [28] It appears that William Griffis lived with his father on and off between 1840 and 1855. Without access to land ownership records, it is difficult to tease out the specific relationships between father and son and the management of the farms in Fulton county.

While Daniel and his family were residing in Fulton county, New York, his older brother Nathaniel and his family were in Niskayuna, Schenectady county. Nathaniel Griffes was 72 in 1840. The 1840 Federal Census lists a Nathaniel Griffes who was between the ages of 70-79. Within his household a female between the ages or 60-69 (his wife Esther, yes another Esther born 1778), a male between 30-39 (his son Stephen) and a female between 20-29 ( possibly his daughter Julia Griffes born 1815). [29]

The household documented next to Nathaniel’s, identified as the household of Stephen Griffes, does not reflect what would be the family configuration of his family in 1840. The census enumerator has recorded Stephen’s household as having two males under 5 (Stephen did not have two sons at that age in 1840), a female between 5-9 (Stephen’s daughter was born after 1840), and a male and female between 20-29 (Stephen and his wife Mary would have been in her 30’s). would be expected . Stephen was just starting his family. He and his wife (Mary Whiteney) and their first of three children, James A Griffes (born 1839) lived with or either next to his father. [30]

In addition to the Griffes families in Niscayuna, Ensign Griffis and his wife and son (aged 15-19) and two daughters (aged 20-29) resided in Saratoga county. [31]

A review of local newspapers in Schenectady County revealed a marriage announcement for Esther Griffis. Esther was one of Nathaniel’s daughters. She married Gideon Wilber on 5 October 1843.

A “Hector N Griffis” and William A. Gates are also mentioned in the local newspaper on November 1843 as having mail left at the local post office. I have no idea who is Hector Griffis! This is a simple declarative sentence but it reflects ‘a few hours’ of research that carries a heavy weight because I have researched this name and I come up with nothing.

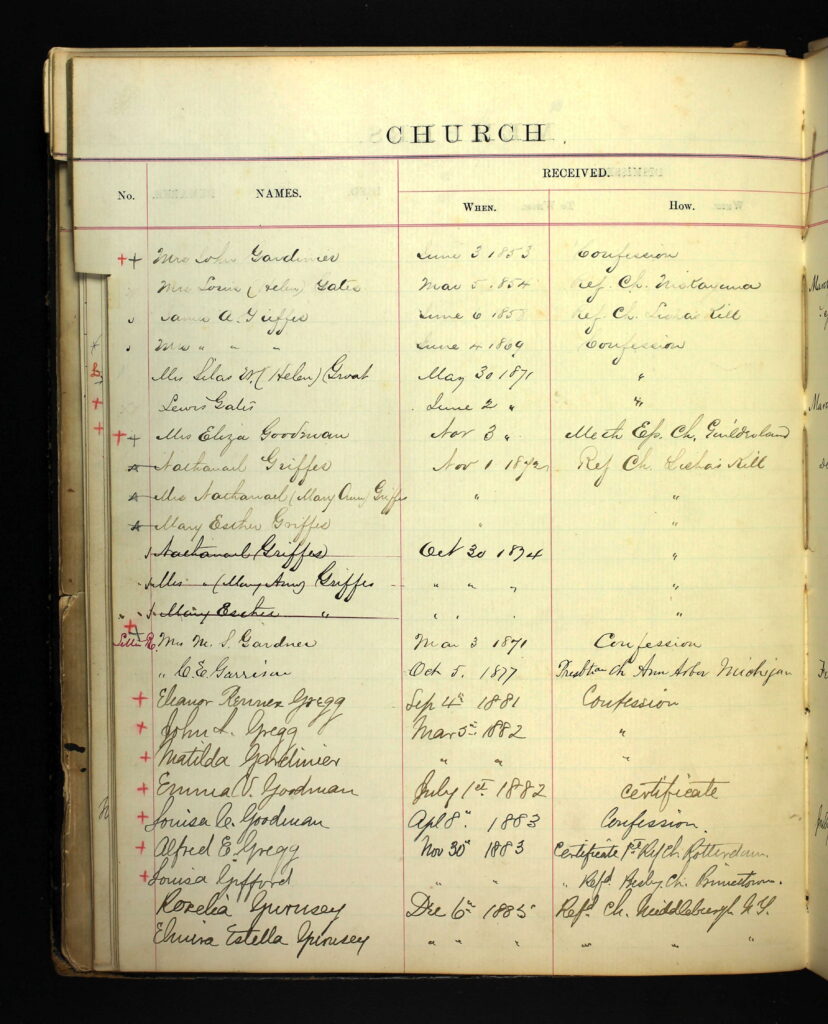

Nathaniel Griffes and family were members of the Dutch Reformed Church in Schenectady, New York. The church records indicate that Nathaniel Griffes and his wife Mary Ann Griffes, and Mary Esther Griffes became a members in 30 October 1834. The three are listed again as being received into the church on 1 November 1842. Nathaniel’s son James A. Griffis was received into the church congregation on 6 June 1853. His wife was received by ‘confession’ on 4 June 1869.

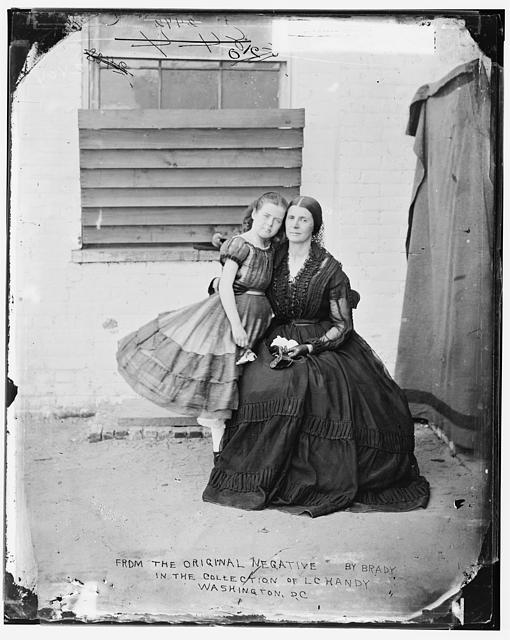

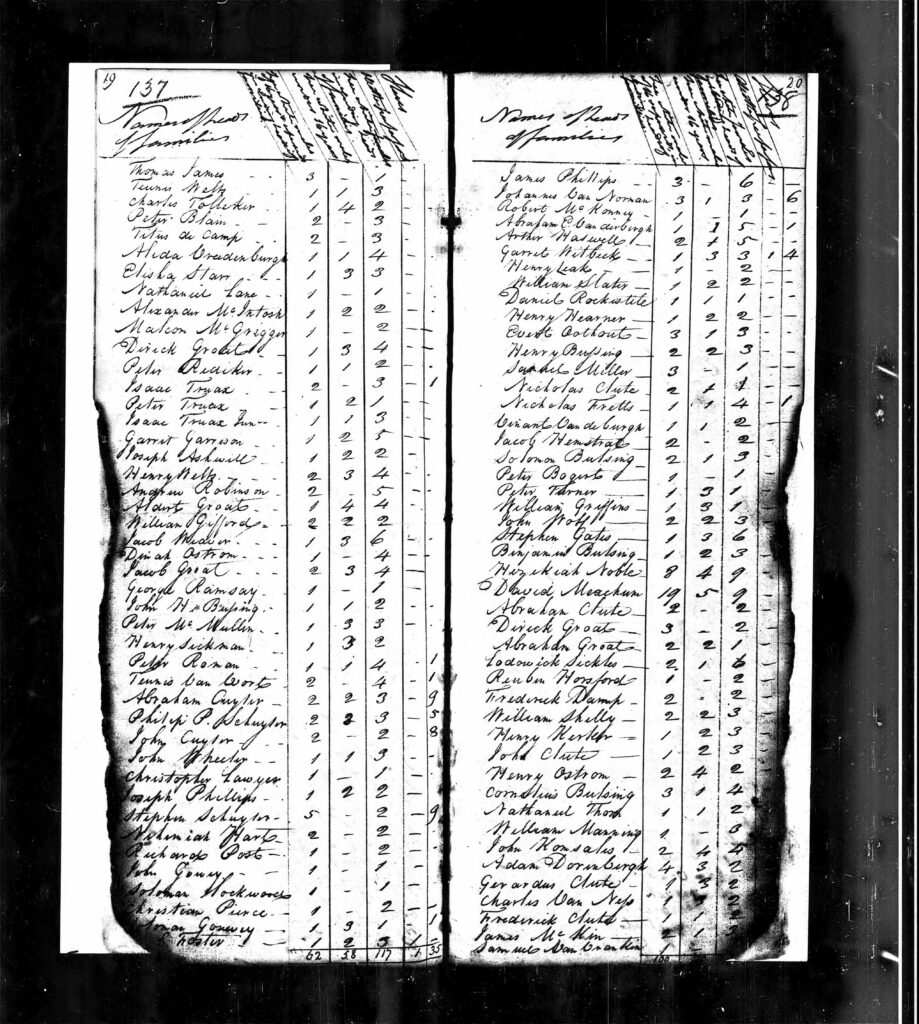

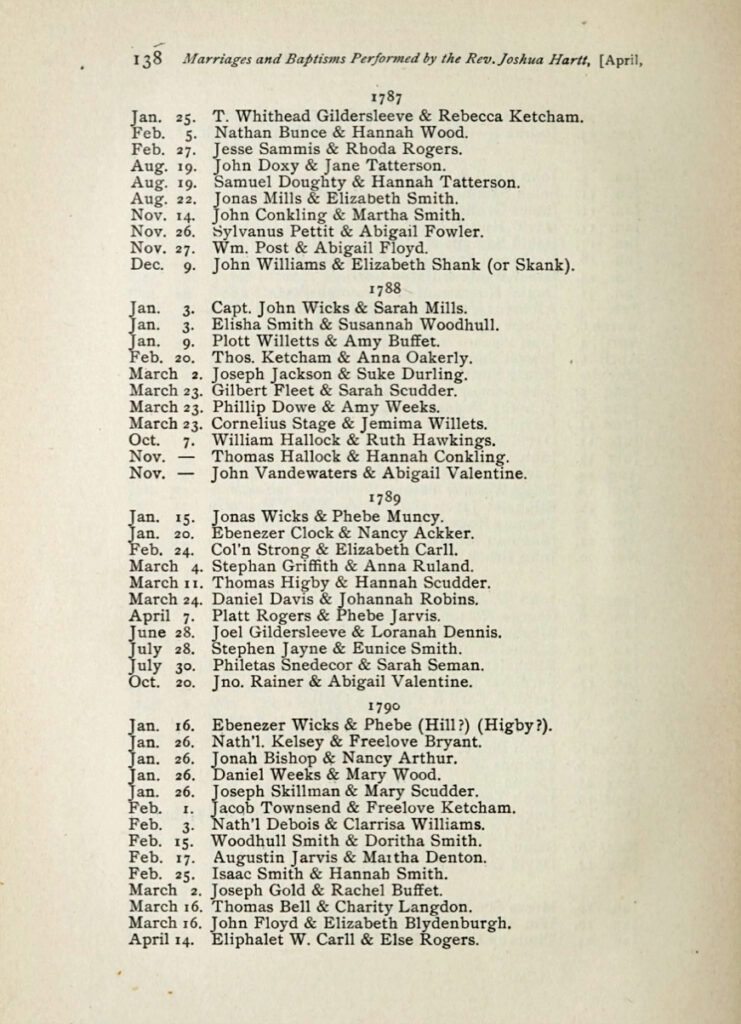

Click for larger view of left had photo | Click for larger view of right hand photo.

Griff(es)(is) family and Gates Family Households in Niscayuna and Watervliet: A Close Connection Between Families

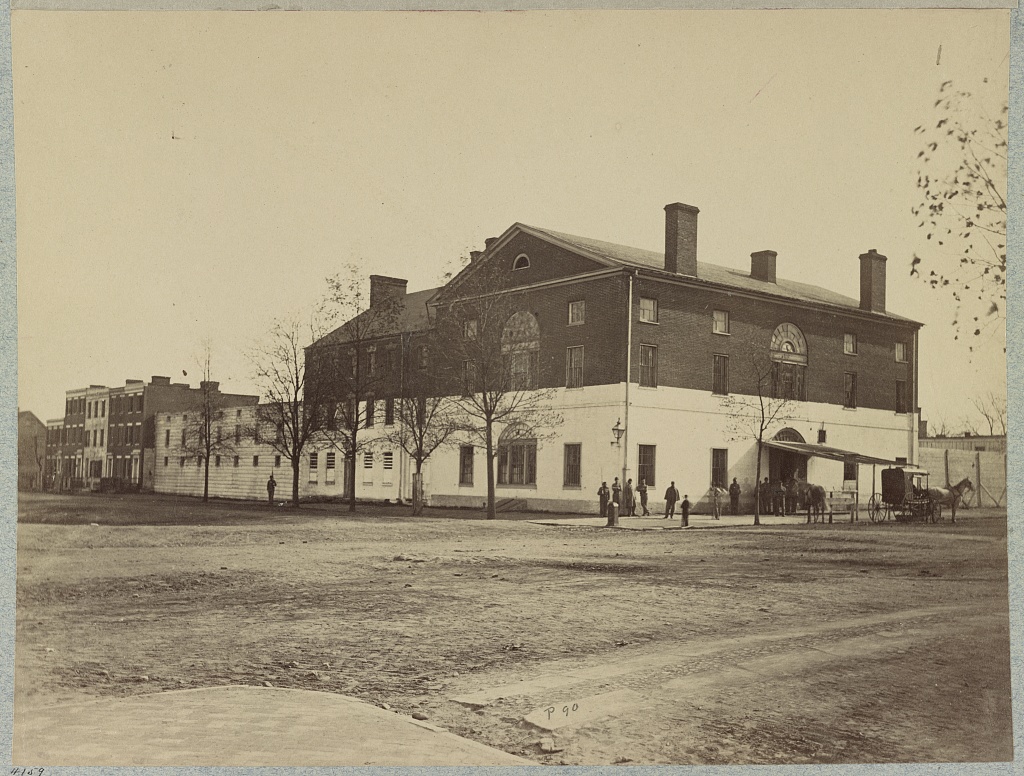

The Town of Niskayuna, New York was created on March 7, 1809 from the town of Watervliet, with an initial population of 681. The name of town was derived from early patents to Dutch settlers: Nis-ti-go-wo-ne or Co-nis-tig-i-one, both derived from the Mohawk language. [32]

It is noteworthy that there are only four pages of census for the town of Niskayuna. There were 111 Niscayuna family households documented in the census on August 7, 1820.

Daniel and at least two of his children, Joel and William moved from the Niscayuna / Watervliet area in the mid 1830’s to Mayfield. It appears that Ensign Griffis and his family also moved from the Niscayuna area to Saratoga County and then to Fulton county to be near his uncle and cousins.

Prior to his time, the Griffis families of Daniel, Joel, William and Ensign lived in close proximity to Daniel’s older brother Nathaniel and the family members of their maternal uncle, Stephen Gates Jr. and a first cousin, Stephen Gates. Two first cousins were named Joel (Joel Griffes 1799-1828 and Joel Griffis (1807-1882). Joel Griffis named one of his sons Stephen, perhaps in honor of his uncle or his first cousin. Below is a diagram of the families of Nathaniel Griffes and his son Stephen Griffes.

Since the 1850 census listed names of individual family members, at this point in my research on Nathaniel and Stephen Griffes, I went back to this census year to determine if I could discover more of children of Nathaniel Griffes and Stephen Gates

Stephen Gates, Nathaniel and Daniel’s maternal uncle, had eight children. His fourth oldest child, Stephen Gates, must have been close to his cousin Nathaniel Griffes despite being Nathaniel’s junior by 17 years. (See Family tree below). Stephen also had eight children. His sixth child was named Nathan Griffes Gates.

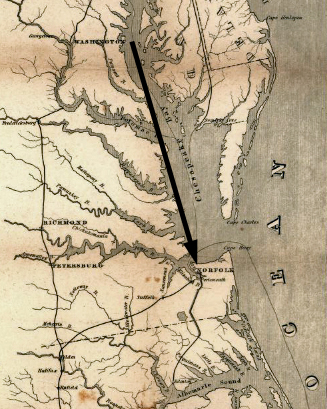

The Griffis(es) and Gates families were close and appeared to follow each other in various relocations from Huntington, Long Island to Watervliet, New York and to Niscayuna, New York. In 1810 both the Gates and Griffis(es) families lived in Watervliet, Albany County. By 1820, both either moved to Niskayuna, Schenectady County.

Stephen Gates, the ‘pater families‘ of the Gates family in the Watervliet / Schenectady / Niscayuna area was a younger brother of Abiah Gates, grandmother of Daniel and Nathaniel. Stephen Gates is found living in this area in the Federal Census in 1790 through 1830. [33] He died in 1837 and was buried in Vale Cemetery. [34] Vale Cemetery is located in Schenectady, New York.

His memorial on the Find a Grave website follows:

“Stephen Gates was born at Huntington, Long Island in 1750. He was married first to Eunice. After her death, he married Eve Young. Stephen Gates was a veteran of the revolutionary war, having been a member of the Albany County Militia, 13th Regiment in addition to serving under other officers. One of his homes was 3 miles west of Bemis Heights, Saratoga. He served as a volunteer guide to the scouting portion of the Continental Army under General Horatio Gates. He also served in other capacities during the war. He also lived in Dutchess County, New York and Schenectady, New York. He died in 1837. His remains were removed to Vale Cemetery after 1857.“

The reference to Stephen Gate’s first marriage to “Eunice” is not documented.

Many generations of both families lived their lives in this area. There are 47 individuals buried in the Vale cemetery with the Gates surname. There are 15 individuals buried at Vale Cemetery with the Griffes surname. [35]

The connections between the Gates and Griffis(th)(es) families were obviously based on one mutual familial trust and affection. [36] This is substantiated by a number of facts surrounding the families. The composition of the four families that live close to each other reveal an older Gates family surrounded by younger Griffis(es) families. Nathaniel was about midway in age between Stephen and his sons, Stephen Jr. and Daniel W. Gates.

- Stephen Griffith, an older brother of Nathaniel and Daniel, married Anna Ruland. Anna was a maternal first cousin of the brothers. Anna’s mother was Naomi Gates, a sister of Nathaniel’s maternal grandmother Abiah Gates. [37]

- The son of Stephen Gates, also named Stephen, named one of his sons Nathaniel Griffes Gates. Obviously in honor or his older cousin Nathaniel.

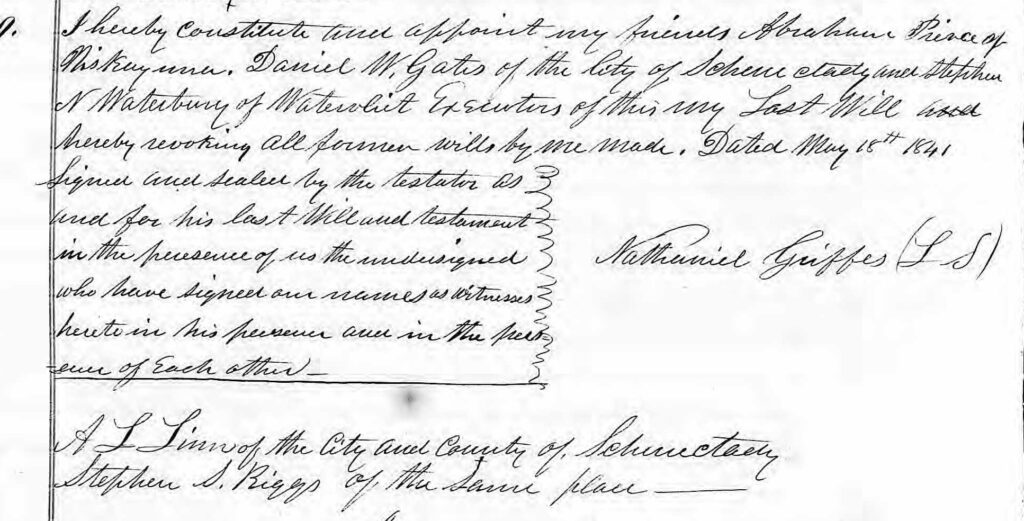

- Nathaniel Griffes named one of Stephen Gates’ sons, Daniel W. Gates, as one of his executors of his will.

Below is the Headstone for Nathaniel Griffes Gates.

Below is an excerpt of the will of Nathaniel Griffes. It reflects Nathaniel’s decision to name one of Stephen Gates’ sons, Daniel W. Gates, as one of his executors of his will.

Nathaniel’s Will reveals a number of discoveries surrounding his family. Many facts that are not discovered through the Federal and New York state census. [38] The will identifies the following individuals in Nathaniel’s family:

- The will identifies his son Stephen.

- The Will mentions his wife ‘Hester’. Hester is a variant of Esther [39]

- Four daughters, two of whom are married are identified in the will: Anna Griffes, wife of Stephen N Waterbury; Abiah Griffes, wife of John Vedder, Julia Griffes and Hester Griffes.

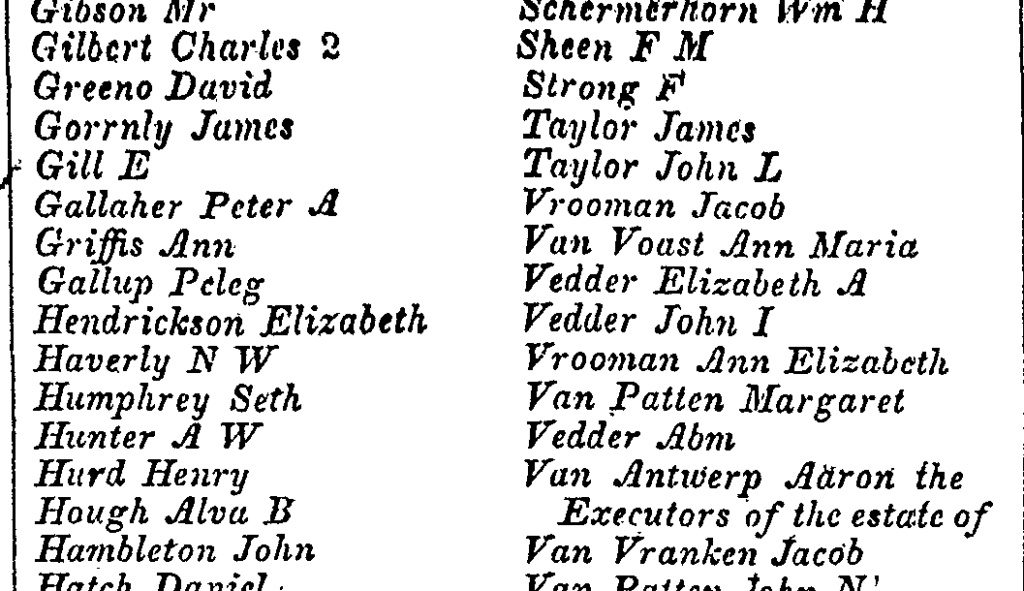

Ann Griffis is mentioned as having letters left at the post office in a local newspaper in 1842 on numerous occasions:

The table below reflects the household composition for the families of Daniel Griffis, Daniel’s uncle Stephen Gates and the son of Stephen Gates, Stephen. Daniel’s brother, Nathaniel Griffes, is not found in the 1830 United states census. Nathaniel would have been 62 years old.

Table 6: 1830 Federal Census: Niskayuna, Schenectady County

| Census Category | Name | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Census Category | Daniel Griffis | Stephen Gates (First Cousin) |

| Male under 5 | 1 (Philip Gates would have been 6) | |

| Male 5-9 | 1 (Possibly Nathaniel G Gates age 11) | |

| Male 10-14 | ||

| Male 15-19 | ||

| Male 20-29 | 1 (One of three sons – possibly a Stephen Griffis age 21) | |

| Male 30-39 | 1 (Stephen was 45 in 1830) | |

| Male 40-49 | ||

| Male 50-59 | 1 (Daniel at age 53) | |

| Female under 5 | 1 (unknown) | |

| Female 5-9 | 1 (Sally Griffis age 3) | 1 (unknown) |

| Female 10-14 | 2 (Evelina would have been 15) | |

| Female 15-19 | ||

| Female 20-29 | ||

| Female 30-39 | 1 (Wife Hanna / Johanna would have been 42) | |

| Female 40-49 | (Daniel’s wife) |

As reflected in Table 6 above, Daniel’s household is very small. It contains a male between the ages of 50-59 (Daniel would have been 53 at the time), A male between 20-29( this could have been William, Joel, or the other unknown brother), a female between 5 – 9 (this could be Sally Griffis at age 3) and a female between 40-49 (presumably Daniel’s wife). [40]

The death of a Stephen Griffis from Schenectady was found in a data collection of Newspaper Extractions from the Northeast, 1704-1930 [41]. It states: “At Schenectady, on Tuesday (May 13m, 1834) of last week Mr. Stephen Griffis (died), aged about 25 years.” Based on an interpolation of facts based on census age distribution tabulations for the household of Daniel Griffis over time, it is assumed Daniel had a sone that was possibly born around 1809. It this was the case, this Stephen Griffis could very well have been Daniel’s son.

During this decade, a review of Newspaper announcements in the Watervliet area revealed the marriage of a Ruth Griffis on the 20th of March, 1830. This was the first occurrence of Ruth Griffis in my research.

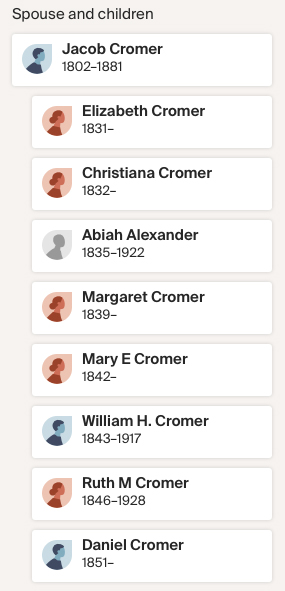

With nothing else to corroborate her relationship with the Griffis family, I researched the past of her husband, Jacob Cromar (Cromer). I went back to the 1850 census which listed individual names and was able to work backward, documenting the family of Ruth Griffis. In 1850, Ruth and her family lived in Charlton, New York. A town the Ensign Griffis lived prior to his moving to Mayfield / Broadalbin. Ruth possibly was the daughter of Ensign Griffis or Daniel Griffis. While I do not have absolute proof, the structure of the respective family households of Ensigner and Daniel over time suggest that Ruth was Daniel’s daughter.

Ruth and Jacob had 7 children as documented in 1850 Federal Census. Ruth was 40 at the time of the 1850 census. A review of Federal and New York state census documented their movement from Charlton, to Mayfield (1860). They probably worked a farm close to Ensign, Daniel, William and Joel. As their family aged, they probably sold the farm and moved to nearby Johnstown. In 1865 Jacob and Ruth lived in Johnstown, New York with their son Daniel. [42]

Nathaniel and Daniel’s cousin Stephen Gates had eight children, as reflected in the family trie diagram at the beginning of the story. Given the census enumerator’s tally of his household in 1830, it is difficult to figure out who could have lived there. [43]

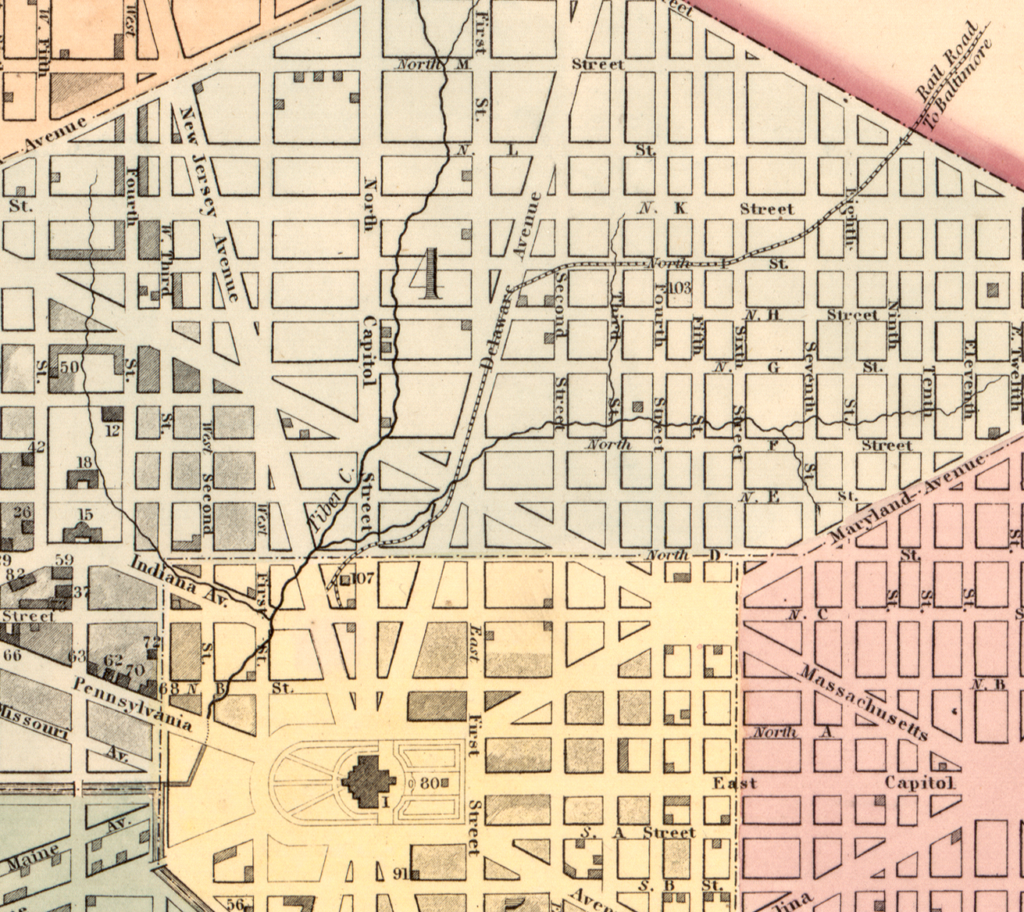

1820 Federal Census in the Niscayuna New York Area

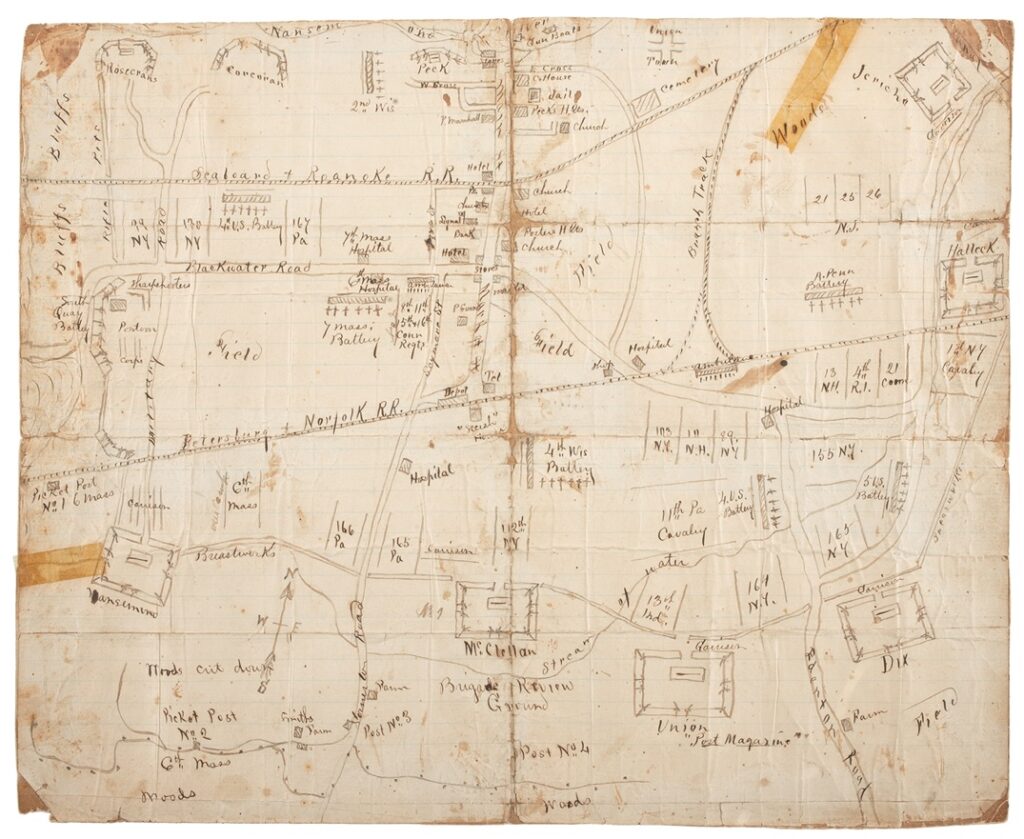

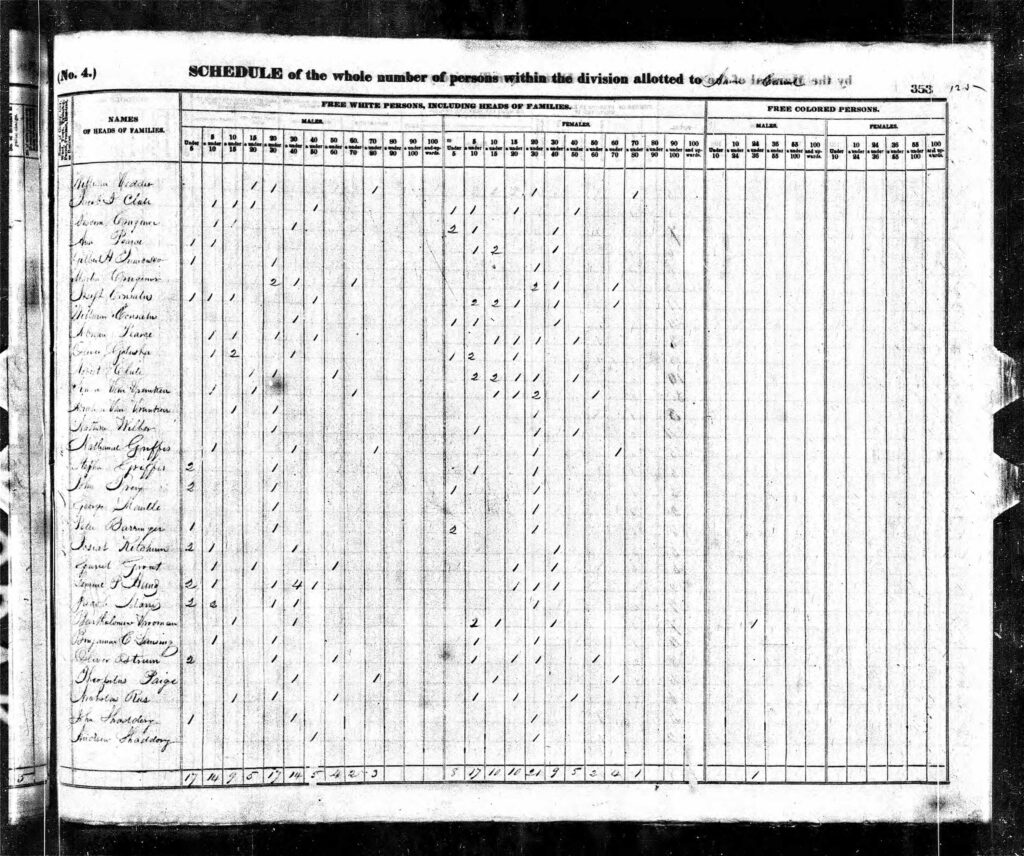

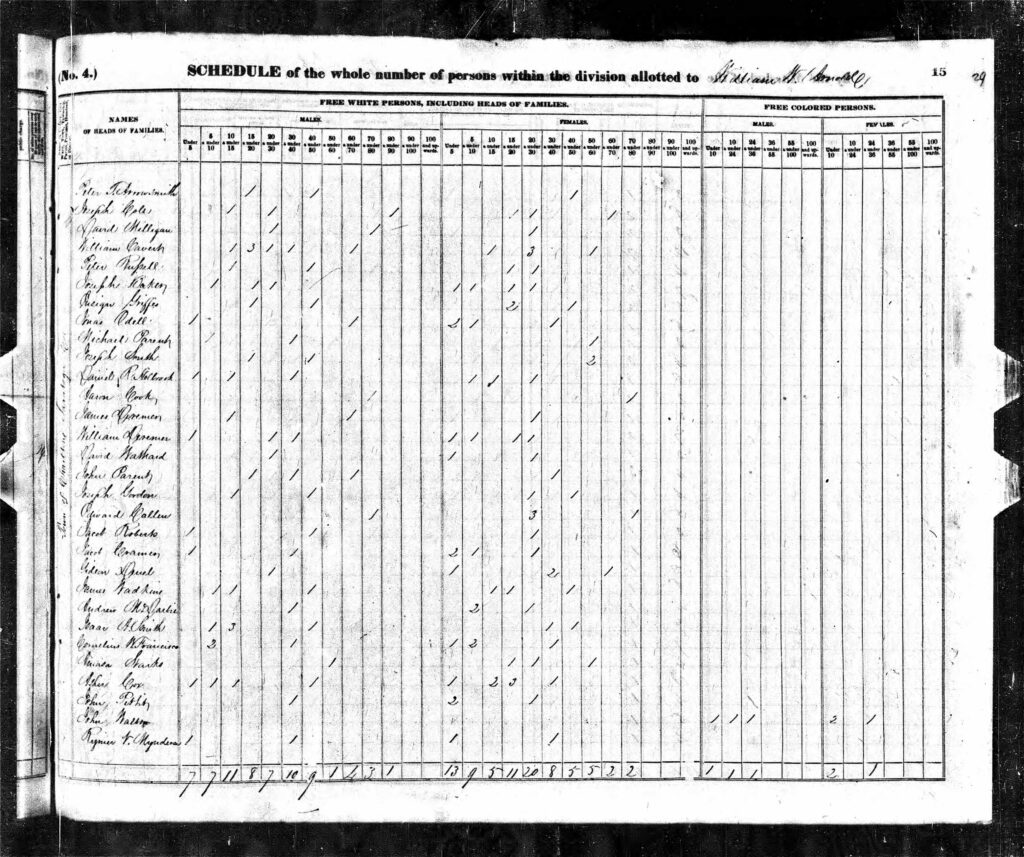

The 1820 Federal Census for Niskayuna, Schenectady County, lists three ‘Griffies’ families in close proximity based on the census taker’s enumeration path and a Gates family household of an uncle (Stephen Gates Jr.) and first cousin (Stephen Gates). It is assumed the census enumerator misspelled their names and based the spelling on phonetics.

This page number 577 from the 1820 United States census provides a graphic portrayal of this extended family.

Between two of the the ‘Griffies’ households, one headed by Daniel and another headed by Nathaniel, is a household headed by Steven Gates. It is assumed that this is the elder Steven Gates (b. 1750 d. 1837). He was Abiah Gates’ brother and Nathaniel and Daniel’s’ maternal uncle. There is also a household one house away from Nathaniel’s that is headed by an Ensign Griffies. Presumably, as stated earlier, Ensign is Nathaniel’s son who is just starting a new family with is wife and son, Samuel, age one.

Table 7: 1820 Federal Census: Niskayuna, Schenectady County

| Census Category | Daniel Griffis | Nathaniel Griffes | Stephen Gates | Ensign Griffis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male <10 | 5 | 1 (Samuel) | ||

| Male 10-15 | 3 (Joel & William) | 1 (Stephen) | ||

| Male 16-25 | 1 | 1 | 1 (Ensign) | |

| Male <45 | 1 (Daniel) | 1 (Stephen) | ||

| Male >45 | 1 (Nathaniel) | |||

| Female <10 | 5 (unknown) | 2 (Ann) | 1 | |

| Female <16 | 1 | |||

| Female <26 | 1 | 1 | 1 (wife) | |

| Female <45 | 1 (wife) | 1 (Esther) | 1 |

While part of the family composition depicted in the 1820 Federal Census of Daniel’s family fits the growth of his family, it is difficult to explain the sudden emergence of 5 unknown females under the age of 10 in his household. In census data after 1820, the household composition of Daniel Griffis does not contain five males in this age growing older. It is not known if the census enumerator made a mistake, if Daniel actually had five additional daughters under the age of 10, or the household had children from the other Griffis and Gates families running about.

A review of Newspapers in Schenectady County during this time period revealed a few occurrences of Nathaniel Griffes(is) in local newspapers, notably for mail left at the local post office:

1810 Federal Census in the Watervliet, New York Area

The 1810 census only lists the head of household and summary data on the distribution of males and females in the household. Based on the reported counties of birth for William G Griffis and Joel Griffis (Albany County), a Daniel Griffis is found living in Watervliet, Albany County. [44] The household of Daniel Griffis contained a 3 males between the ages of 1-9. Presumably the three sons under 10 included Joel (2 at the time) and William (age 6). The name of the third male under 10 is not known. There also is an unknown third son between the ages of 11 and 15. Daniel’s household also included a male between the age of 26-44. Daniel would have been 33 at the time. His household also included one female under the age of 10 (this could be Ruth Griffis based on age), and a female between the age of 26-44 (presumably Daniel’s wife).

There is also another Daniel Griffis listed in the 1810 census in Albany. However, given the proximity of Daniel’s brother, Nathaniel, and two Gates relatives from his mother’s side of the family in Watervliet, it is assumed Daniel lived in the Watervliet /Schenectady area in 1810.

Table 6: 1810 Federal Census: Watervliet, Albany County

| Household | Male < 10 | Male < 16 | Male < 26 | Make < 45 | Female < 10 | Female < 16 | Female < 26 | Female < 45 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stephen Gates Jr. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Daniel Griffis | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Steven Gates | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Nathaniel Griffis | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

In 1800, Daniel would have been 23 years old. Daniel is not documented as a head of a household in 1800. It is not known where Daniel lived in 1800.

Conclusion

This three part story not only attempts to impart knowledge about the Griffis family surname but also discusses through my research what is, and what is not, genealogical “proof“.

Tracing one’s surname back in name is not necessarily an easy process. As one gets into the detail, the ‘facts’ become less certain and oftentimes confusing. By relying on a variety of sources to substantiate facts, one’s certainty of a fact or relationship increases. Sources of facts, evidence, may vary and could be personal knowledge (someone you knew within your lifetime), a Bible, a will, a deed, an obituary, death certificate, a church baptismal document, a pension application, census records, etc. The ability to find a number of corroborating facts increases the likelihood that you are headed in the right direction.

In genealogy, evidence includes many of the sources mentioned above. It does not include a family tree posted on an ancestry website, nor does it include published or unpublished compiled family histories, unless they contain specific historical references to evidence or facts.

A genealogist with a law background has cogently addressed this subject in the context of drawing a distinction between “proof” and “evidence,” and the amount of evidence that is needed to produce a certain standard of proof. There are parallels in family history research and law. [45]

“Evidence is anything that is offered to prove the existence or nonexistence of a fact. … evidence is what supports a belief that a fact is proved (or disproved).” [46]

In law there are different standards of proof, from “beyond a reasonable doubt” (criminal cases) to “preponderance of the evidence” (civil cases). In between these two standards is “great weight and preponderance of the evidence”.

What this might operationally mean for genealogy research is:

- Beyond a reasonable doubt: at least 95% of the facts compel a certain conclusion, conclusive proof;

- Great weight and preponderance: 65-85% of the evidence supports a solid conclusion, probably true, appears to be true, most likely true;

- Preponderance of the evidence: a conclusion is more likely than not – it has enough weight more than a flip of the coin that it is solid, probably true.

Basically, these principles have guided my research. Hopefully, my results have revealed ‘family facts’ as well as interesting stories about distant relatives. It is a process and, no doubt, the stories may change for the better as time goes on.

Sources

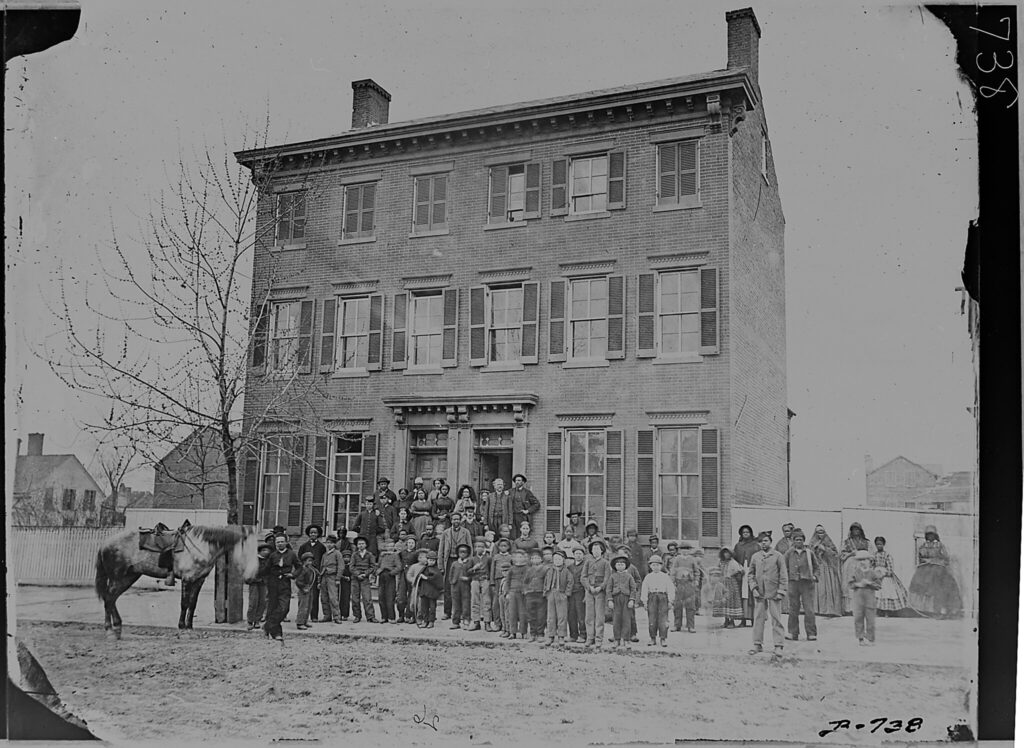

The feature image at the top of this story is a photograph taken on July 16, 1935, entitled “Griffis Family Reunion’. It is a photograph that is in one of the photograph albums of Evelyn Griffis. Click here for a larger view of the photograph. The patriarch and matriarch of the Griffis family in the photograph are in the center of the photograph. William James Griffis and his wife Charlotte (“Lottie”) Wetherbee Griffis. William J. Griffis’ father was William G. Griffis who is mentioned in this story. William G. Griffis was a son of Daniel Griffis.

[1] Shiela Rowlands, Sources for Surname Studies, in Pages 147 – 160, quote Page 147.

[2] Ely McClellan, John Peters, John Billings, Surgeon General’s Office of the Army, Cholera epidemic of 1873, War Department, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1875

[3] For historical background of Mayfield, New York, see: History of Mayfield, NY from History of Fulton County, Revised and Edited by Washington Frothingham, published by D. Mason & Co. Syracuse, NY 1892 https://books.google.cm/books?id=LIYaAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=fr&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

G. F. Pyle, The Diffusion of Cholera in the United States in the Nineteenth Century, Geographical Analysis, Published on behalf of the Department of Geography, The Ohio State University, Jan 1969, Pages 59-75 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1538-4632.1969.tb00605.x;

alternative link: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1538-4632.1969.tb00605.x

Lorraine Frasier, Mayfield History, visitsacadanga.com , page accessed 17 Nov 2021.

Fulton County was created on April 18, 1838 from Montgomery County. Montgomery County was created on March 12, 1772 from Albany County originally called Tryon County and renamed in 1784. This particular county was originally named after Tryon County after colonial governor William Tryon (1729–1788), renamed after the American Revolutionary War general Richard Montgomery (1738–1775) in 1784 .

For an excellent source that provides New York county maps over time, see: Interactive Map of New York County Formation History, MapsofUS.org, Page accessed 5 May 2019.

See also Mayfield, New York, Wikipedia, Page last updated 31 October 2021, page accessed 11 Nov 2021.

Smith, Robert Pearsall, 1827-1898, Map of Fulton County, U.S. Library of Congress, New York : from actual surveys, Created / Published Philadelphia : Published by Jno. T. Hill, 1856. Digital Id http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3803f.la000497

Beach Nichols, Atlas of Montgomery and Fulton Counties, New York : from actual surveys, New York : Stranahan & Nichols, 1868

[4] Chace, J., Smith, Robert Pearsall, Map of Fulton County, New York : from actual surveys, Philadelphia : Published by Jno. T. Hill, 1856. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3803f.la000497

[5] Among the various sources that were used to determine William J Griffis’ birth date:

- New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900, 153rd Infantry, Page 257;

- U.S. Department of Interior, Bureau of Pensions, Certificate Number 662.205, Amanda Griffis (Carpenter), Declaration of a Widow for Original Pension, February 7, 1908. The latter source indicates the actual birth date of William J Griffis as March 14th, 1843. See image of original document.

[6] The information in the 1855 New York state census is noteworthy. It was the first to record the names of every individual in the household. It also asked about the relationship of each family member to the head of the household, something that was not asked in the federal census until 1880. The 1855 New York state census also provides the length of time that people had lived in their towns or cities as well as their state or country of origin. This is particularly helpful for tracing ancestors that may have moved to the specific area. If born in New York State, the county of birth was noted, which is helpful for tracing migration within New York State.

Information collected in this census includes:

- Name (of each household member)

- Age, gender, race

- Relation to the head of the household

- Birthplace (country, U.S. state, or New York county)

- Marital status

- Length of residence in current municipality

- Occupation, citizenship status, and if a landowner

- Literacy status, and if deaf, dumb, or blind

[7] Joel Griffis : U.S., Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules, 1850, New York, Agriculture, Fulton County, Mayfield, Page 211-12, Line 28, 18 Jul 1850

Daniel Griffis: U.S., Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules, 1850, New York, Agriculture, Fulton County, Mayfield, Page 223-224, Line 19, 3 Aug 1850

William Griffis: U.S., Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules, 1850, New York, Agriculture, Fulton County, Mayfield, Page 213-214, Line 17, 19 Jul 1850

[8] Ensinger Griffis, U.S., Federal Census, 1850, New York, Fulton County, Broadalbin, Page 49, Lines 12-15, Enumeration date 5 Aug 1850. See larger view of page of census depicted below.

[9] Broadalbin, Wikipedia, this page was last edited on 1 Nov 2021 and accessed on 29 Dec 2021.

See also: Washington Frothingham, History of Fulton County, Syracuse, NY: D. Mason & Co, 1892, Pages 59-61

[10] Census History, Staff, Census Instructions, United States Census Bureau, Page updated December 09, 2021, page accessed 4 Jan 2022. https://www.census.gov/history/www/through_the_decades/census_instructions/

[11] Elizabeth Garner and Ana Paula de la O Campos, Identifying the “Family Farm”: An informal discussion of the concepts and definitions, ESA Working Paper No. 14-10 December 2014, Agricultural Development Economics Division, Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Page 11

[12] Census History, Staff, State Cenuses, United States Census Bureau, Page updated December 09, 2021, page accessed 4 Jan 2022. https://www.census.gov/history/www/genealogy/other_resources/state_censuses.html

See also Instructions for taking the New York state 1855 census : Elias Leavenworth, Secretary of State, Instructions for Taking the Census of the State of New York in the Year 1855, Albany: Weed, Parsons & Co., Printers, 1855. Page 10 https://nysl.ptfs.com/knowvation/app/consolidatedSearch/#search/v=list,c=1,q=field11%3D%5B992790%5D%2CqueryType%3D%5B16%5D,sm=s,l=library1_lib%2Clibrary4_lib%2Clibrary5_lib

“It is made the duty of the town clerks, and the clerks of the common council of cities,to receive from the office of the county clerk, the blanks for the marshal or marshals appointed for taking the census of town and cities, and to deliver them to the latter, whose duty it will be to apply for the same. Where more than one marshalis appointed in a town or ward, the clerk should divide the blanks between them, as nearly proportioned to the population in the several election districts, as possible. The intimate knowledge which these clerks are presumed to have of the relative population and wants of their several election districts, led to their being designated as proper persons to receive and subdivide the blanks. As a general rule, there will be one marshal appointed to each election district ; but in some cases, where the whole population does not exceed three thousand, one person only will be appointed in the town. In all such cases the commissions of the marshals will specify the fact, and be sufficient authority to the clerk for delivering over, upon application, the whole amount of blanks received for such districts.

“The marshals, being appointed, will receive with their commissions, a copy of these instructions, and should lose no time in becoming familiar with the details therein contained, and in learning, if necessary, by inquiry at the town clerk’s office, or of the clerk of the common council, the boundaries of their districts. They should also apply for the requisite quantity of blanks from the town clerk’s office ; or, if in a city, from the office of the clerk of the common council, and make arrangements to begin their labors on the first Monday of June.“

[13] In the 1855 New York state census, Daniel Griffis reported that he was born in Suffolk County in 1776 based on a reported age of 79. He lived in Fulton county for 20 years which implies he moved to Fulton county around 1835.

Page 7 of the Hall Manuscript indicates Daniel Griffis’ birth date:

Source: M.K. Hall, Griffith Genealogy: Wales, Flushing, Huntington, Unpublished Manuscript 1929, originally published 1937. It has been reproduced for commercial access by a variety of publishers. The copy I accessed was published by Creative Media Partners, LLC, Sep 10, 2021. This work is in the public domain in the United States of America. A PDF copy of the book can be found here.

[14] 1855 New York Census, Fulton County, Mayfield, Election District 1, Page 499, Household 6, Lines 27-31. Click to see image of page.

[15] 1855 New York Census, Fulton County, Mayfield, Election District 1, Page 503, Household 33, Lines 15-16. Click to see image of page.

[16] 1850 United States Federal Census, Mayfield, Fulton County, New York, National Archives and Administration, page 28, lines 31-37

[17] 1850 United States Federal Census, Mayfield, Fulton County, New York, National Archives and Administration, page 38, lines 6-10

[18] The two manuscripts are

Mildred Griffith Peets, Griffith Family History in Wales 1485–1635 in America from 1635 Giving Descendants of James Griffis (Griffith) b. 1758 in Huntington, Long Island, New York, compiled by Capitola Griffis Welch, 1972 . PDF copy of the manuscript can be found here.

M.K. Hall, Griffith Genealogy: Wales, Flushing, Huntington, Unpublished Manuscript 1929, originally published 1937. It has been reproduced for commercial access by a variety of publishers. The copy I accessed was published by Creative Media Partners, LLC, Sep 10, 2021. This work is in the public domain in the United States of America. A PDF copy of the book can be found here.

[19] Alice Plouchard Stelzer, Having Trouble Researching Your Female Ancestors? Here’s Some Help, Family History daily, Originally published Feb 2013, Updated Feb 2017

Introduction to Tracing Women (National Institute), FamilySearch.org,Page was last edited on 10 October 2015, Page accessed 01 Mar 2022.

Leland Meitzler, Tracing Your Female Ancestors, Genealogy Blog, 22 April 2013, Page accessed 11 Nov 2019

Melisa Johnson, Methodology for Elusive Female Ancestors, National Genealogical Society NGS Monthly, Accessed 14 Dec 2021

Bibliography of Research sources for Finding Your Female Ancestors Workshop, State Library of North Carolina and State Archives of North Carolina 23 August 2014

Find Your Female Ancestors, Family Tree Magazine

Finding Elusive Female Ancestors: 8 Essential Tips | Findmypast Masterclass, 15 Mar 2018

[20] Joel Griffis Household, 1850 United States Census, New York, Fulton County, Mayfield, Page 29, Lines 31-37, Enmerated on 17 July 1850.

[21] Headstone Inscription: “WIFE OF JOEL GRIFFIS” “IN HER 39 YR” Burial: Riceville Cemetery Mayfield Fulton County New York, USA Created by: Katherine MacIntyre Record added: Aug 08, 2012 Find A Grave Memorial# 95024757

The website, findagrave.com, lists the following Griffis members in the Riceville cemetery in Mayfield, New York.

- A E Griffis, dates unknown

- Augusta C Griffis, Inscription: “WIFE OF DANIEL GRIFFIS” “AGE 27”

- E A Griffis or F A Griffis, Birth and Death dates Unknown – This might be Ensinger Griffis.

- Margery Griffis, – 1 May 1850

- William G Griffis 1804 – 19 Dec 1850

[22] Newspaper announcement: The Schenectady Cabinet, Marriage and Engagement Notices, 2 Mar 1831.

Joel Griffis was born October 14, 1807 in Albany , NY and died 18 October, 1882 in Gloversville, NY; Margery Gillespie was born 30 Jan 1897 in Schenectady, NY and died 01 May 1850 in Mayfield, NY.

[23] The following represents the family of Joel Griffis. Joel had a second family after his first wife, Margery, passed away.

[24] William G Griffis – Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/28262391/william-g-griffis : accessed 04 January 2022), memorial page for William G Griffis (1804–19 Dec 1860), Find a Grave Memorial ID by Thomas Dunne 28262391, citing Riceville Cemetery, Mayfield, Fulton County, New York, USA ; Maintained by Jim Griffis (contributor 47396794) .

[25] Present John Stewart county judge in the matter of the administration of there goods, chattel accounts of William G. Griffis, decd., January 7, 1861 Probate Date, New York Wills and Probate Records , Fulton County, Minutes, Volume 0003-004, 1856-1873, pages 229-230, image 148, See original document.

[26] Enumerators of the 1840 census were asked to include the following categories in the census: name of head of household; number of free white males and females in age categories: 0 to 5, 5 to 10, 10 to 15, 15 to 20, 20 to 30, 30 to 40, 40 to 50, 50 to 60, 60 to 70, 70 to 80, 80 to 90, 90 to 100, over 100; the name of a slave owner and the number of slaves owned by that person; the number of male and female slaves and free “colored” persons by age categories; the number of foreigners (not naturalized) in a household; the number of deaf, dumb, and blind persons within a household; and town or district, and county of residence.

The 1840 census also asked for the first time, the ages of revolutionary war pensioners and the number of individuals engaged in mining, agriculture, commerce, manufacturing and trade, navigation of the ocean, navigation of canals, lakes and rivers, learned professions and engineers; number in school, number in family over age twenty-one who could not read and write, and the number of insane.

Taken from Chapter 5: Research in Census Records, The Source: A Guidebook of American Genealogy by Loretto Dennis Szucs; edited by Loretto Dennis Szucs and Sandra Hargreaves Luebking (Salt Lake City, UT: Ancestry Incorporated, 1997).

Although the 1840 census asked for the ages of revolutionary war pensioners, many revolutionary war veterans may not have received a pension or were not documented. I have reviewed the published list and find many of the Griffis(th) and Gates revolutionary war veterans are not documented in this special publication.

See: Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services with their Names, Ages, and Places of Residence, Published by Authority of an Act of Congress Under the Direction of the Secretary of State, Washington: Blair and Rives 1841.

The following table depicts key individuals that were used to link various Griffis family members together in the 1840 and earlier censuses. It indicates their respective birth dates and ages when Federal census data was captured. I used this as a base to compare the family configurations recorded by census takers at specific times for each of the earlier censuses.

Key Family Members Used to Link Griffis Families in Census Prior to 1840

| Person | Birth Date | Age 1840 | Age 1830 | Age 1820 | Age 1810 | Age 1800 | Age 1790 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nathaniel Griffes | 1768 | 72 | 62 | 52 | 42 | 32 | 22 |

| Stephen Griffes | 1805 | 35 | 25 | 15 | 5 | ||

| Joel Griffes | 1799 | 41 | 31 | 21 | 11 | 1 | |

| Julia Griffes | 1815 | 25 | 15 | 5 | |||

| Stephen Gates Jr | 1750 | 90 | 80 | 70 | 60 | 50 | 40 |

| Stephen Gates | 1785 | 55 | 45 | 35 | 25 | 15 | 5 |

| Daniel Griffis | 1777 | 63 | 53 | 43 | 33 | 23 | 13 |

| Ensinger Griffis | 1797 | 43 | 33 | 23 | 13 | 3 | |

| Son of Daniel | 1801- 1809 | 39-31 | 29-21 | 19-11 | 9-1 | ||

| Dau of Daniel | 1801- 1809 | 39-31 | 29-21 | 19-11 | 9-1 | ||

| William G Griffis | 1805 | 35 | 25 | 15 | 5 | ||

| Joel Griffis | 1807 | 33 | 23 | 13 | 3 | ||

| Sally Griffis | 1826 | 14 | 4 |

William Dollarhide, The Census Book: A Genealogist’s Guide to Federal Census Facts, Schedules and Indexes, Heritage Quest: Bountiful, UT, 2000.

[26a] Land and property records from the New York Land Office and county courthouses were digitalized and made accessible by Familysearch.org . The records include land grants, patents, deeds, and mortgages. This collection includes all counties except Franklin, Nassau, and Queens. Researchers should note that the Oneida County records will be found with the Herkimer County records.

United States, New York Land Records, 1630-1975.”Database with images. FamilySearch. https://FamilySearch.org : 17 February 2023. Multiple county courthouses, New York. https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/2078654

[26b] Daniel Griffis, Grantee of Property United States, New York Land Records, 1630-1975.”Database with images. FamilySearch. https://FamilySearch.org : 17 February 2023. Multiple county courthouses, New York. Date : 1 Jan 1837, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:H59Y-MJ3Z

[26c] William G. Griffis, Grantee of Property United States, New York Land Records, 1630-1975.”Index of Deeds, Line 2, Page 293, Database with images. FamilySearch. https://FamilySearch.org : 17 February 2023. Multiple county courthouses, New York. Date Ocober 28, 1841, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6N73-61SR

[27] 1840 United States Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Mayfield, page 332, Line 5, image 14 of 29 filmstrip. See copy of census page.

1840 United States Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Mayfield, page 331, Line 12, image 14 of 29 filmstrip.

1840 United States Federal Census, Mayfield, Fulton County, New York, National Archives and Administration, image 14 of 29 filmstrip.

[28] Joel Griffis household, 1840 United States census, New York, Fulton County, Mayfield, Page 144, Line 5

[29] Daniel Griffis household, 1840 United States census, New York, Fulton County, Mayfield, Page 142, Line 11

[30] Nathaniel Griffes and Stephen Griffes households, 1840 United States census, New York, Schenectady County, Niscayuna, Page 125, Lines 15 and 16

[31] Ensign Griffis household, 1840 United States census, New York, Saratoga County, Carlton, Page 29, Line 7. The Ensign Griffis family household is noted as having one male between the ages of 16 – 19 (which correlates with his son Samuel’s age of 19, born 1821), a male between the ages of 440-49 (which would be Ensign age 43, born in 1797), a female between the ages of 40-49, and two unknown daughters between the ages of 15-19.

[32] Austin Yates, Schenectady County New York, Its History to the Close of the Nineteenth Century, New York; New York History Company 1902

Niskayuna, New York, Wikipedia, Page updated 22 February 2022, Page accessed 27 Feb 2022

Horatio Gates Spafford, LL.D. A Gazetteer of the State of New-York, Embracing an Ample Survey and Description of Its Counties, Towns, Cities, Villages, Canals, Mountains, Lakes, Rivers, Creeks and Natural Topography. Arranged in One Series, Alphabetically: With an Appendix… (1824), at Schenectady Digital History Archives, selected extracts, accessed 27 Feb 2022

George Rogers Howell and John H. Munsell (1886). “History of the Township of Niskayuna”. History of the County of Schenectady, N.Y., from 1662 to 1886. New York City, NY: W.W. Munsell.

[33] Stephen Gates, 1790 United States Federal Census, New York, Albany, Watervliet, Line 23, Page 138. On line 21 there is a William Griffins. The household of Stephen Gates included 3 white males under 16 and one white male over 16 (Stephen Gates), and 6 white females.

Enumerators of the 1790 census were asked to include the following categories in the census: name of head of household, number of free white males of sixteen years and older, number of free white males under sixteen years, number of free white females, number of all other free persons, number of slaves, and sometimes town or district of residence. The categories allowed Congress to determine persons residing in the United States for collection of taxes and the appropriation of seats in the House of Representatives. This first United States census schedules differs in format from later census material, as each enumerator was expected to make his own copies on whatever paper he could find. Unlike later census schedules an enumerator could arrange the records as he pleased.

The 1790 census of the original thirteen states canvassed an area of seventeen present states. Schedules survive for eleven of the thirteen original states: Connecticut, Maine (part of Massachusetts at the time), Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Vermont. (Vermont became the fourteenth state early in 1791 and was included in the census schedules).

Enumerators were only required to make one copy of the census schedules to be held by the clerk of the district court in their respective area. In 1830, Congress passed a law requiring the return of all decennial censuses from 1790-1830. At this point it was discovered that many of the 1790 schedules had been lost or destroyed, about two-thirds of the original census from the time period. The 1790 census suffered district losses of Delaware, Georgia, Kentucky, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Virginia. However, some of the schedules for these states have been re-created using tax lists and other records. Virginia was eventually reconstructed from tax lists as well as some counties from North Carolina and Maryland.

Taken from Chapter 5: Research in Census Records, The Source: A Guidebook of American Genealogy by Loretto Dennis Szucs; edited by Loretto Dennis Szucs and Sandra Hargreaves Luebking (Salt Lake City, UT: Ancestry Incorporated, 1997).

[34] Nathaniel Griffes Gates, Find a Grave, memorial 8743987, Birth 16 Nov 1819, Schenectady, Schenectady County, New York, Death 16 Aug1898 (age 78), Buried in Forest Hill Cemetery, Ann Arbor, Washtenaw County, Michigan, Plot: Block 21 Lot 1.

[35] The following individuals are buried in Vale cemetery:

Griffes Family Buried in Vale Cemetery Schenectady New York

| Name | Dates | Plot Information | Tombstone Photo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angelica K Schermerhorn Griffes | 1847 – 1930 | Section H | Photo |

| Anna R Griffes | 4 Feb 1861 – 6 Nov 1885 | Section M-3 | Photo |

| Esther Griffes | 1778 – 3 Jun 1848 | Photo | |

| James A Griffis | 3 Dec 1839 – 18 Jan 1898 | Section M-3 | Photo |

| Jane Viele Griffes | 24 Oct 1832 – 25 Jul 1918 | Section M-30 | Photo |

| Joel Griffes | 10 May 1799 – 24 Oct 1828 | Photo | |

| Julia Griffes | |||

| Julia A Griffes | 10 Dec 1838 – 25 Sep 1864 | Section M-3 | Photo |