This is the sixth part of a story about Johann Wolfgang Sperber immigrating to the United States. Due to its length, I have broken part six into two time periods: 1850 – 1868 and 1870 – 1905.

This is the sixth and final part of the story of Johan Wolfgang Sperber’s immigration to Gloversville, New York from the Grand Duchy of Baden.

The first of this story provided an overview of the family legacy John Sperber established in his new homeland, an historical background on where John was from in Baden, Germany, the influences on his migration to the United States, and the historical evidence of his departure and arrival to America.

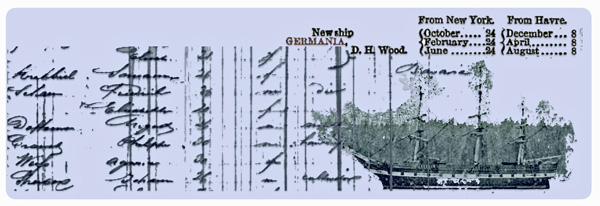

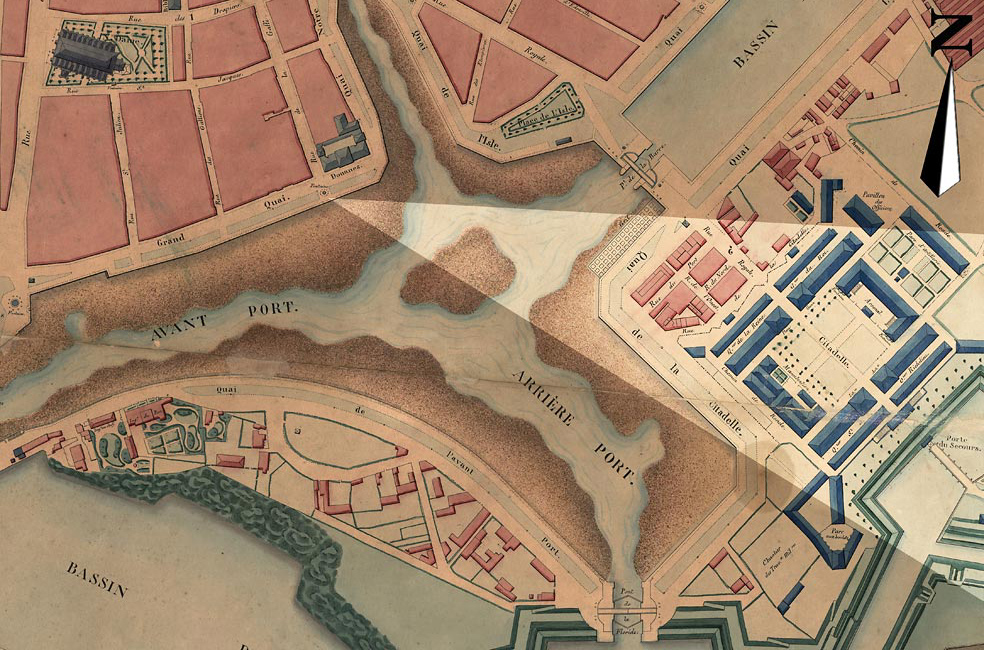

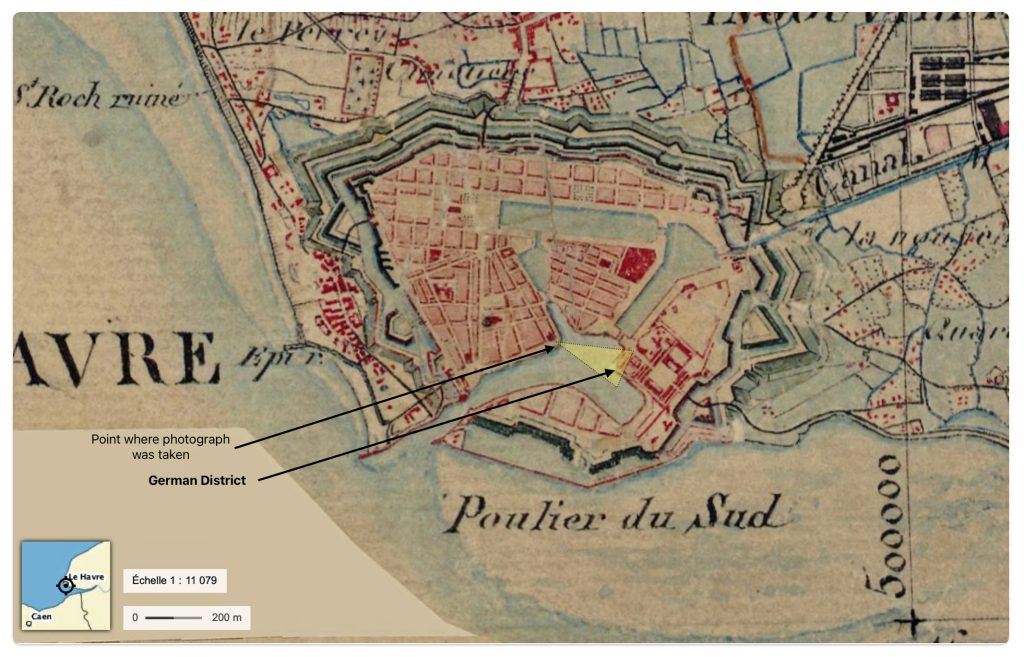

The second part of John Sperber’s story describes his journey from Baden-Baden to Le Havre based on historical evidence and historical accounts.

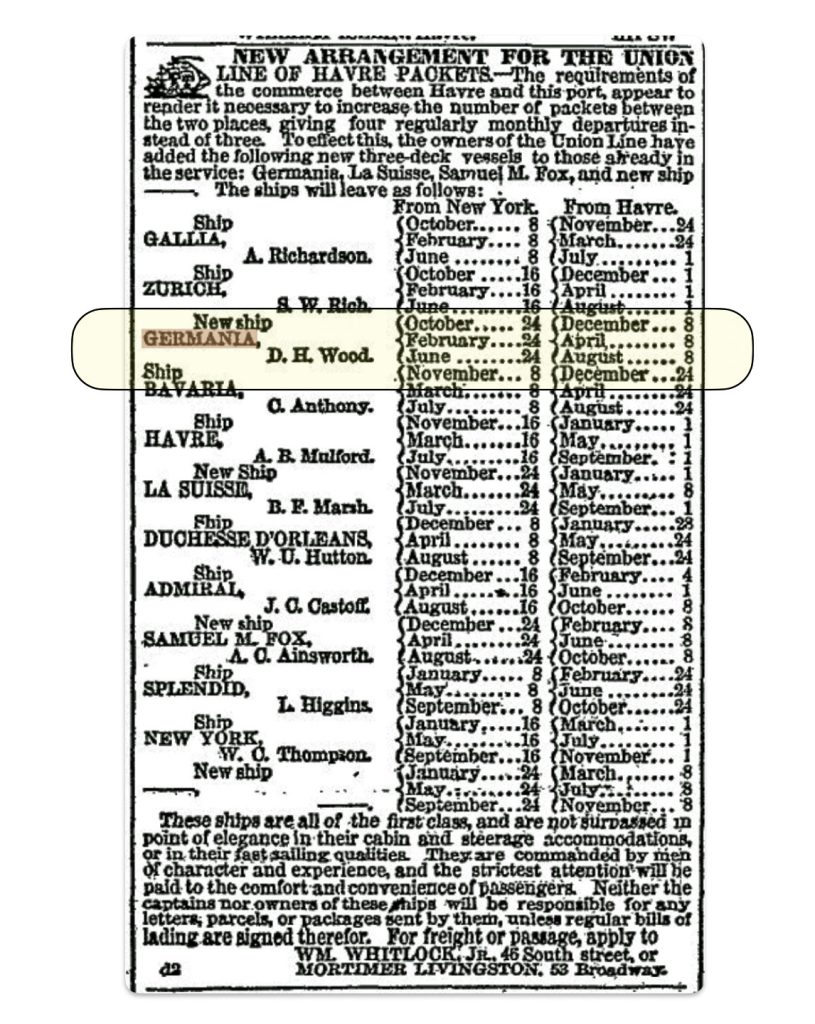

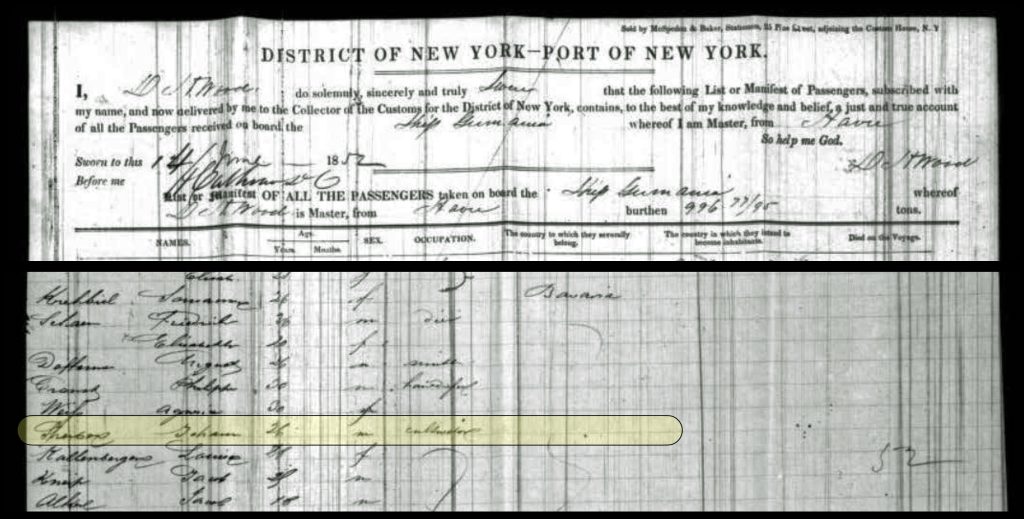

The third part of the story assesses the three major inland pathways to European ports that John had options to consider. Since it is not absolutely certain that John sailed on the Germania from Le Havre, I have provided historical background on the relative accessibility of the three major routes John may have taken to make his voyage to the United States.

The fourth part of the story provides possible explanations of why Johann ended up in Fulton County, New York working in the glove making industry.

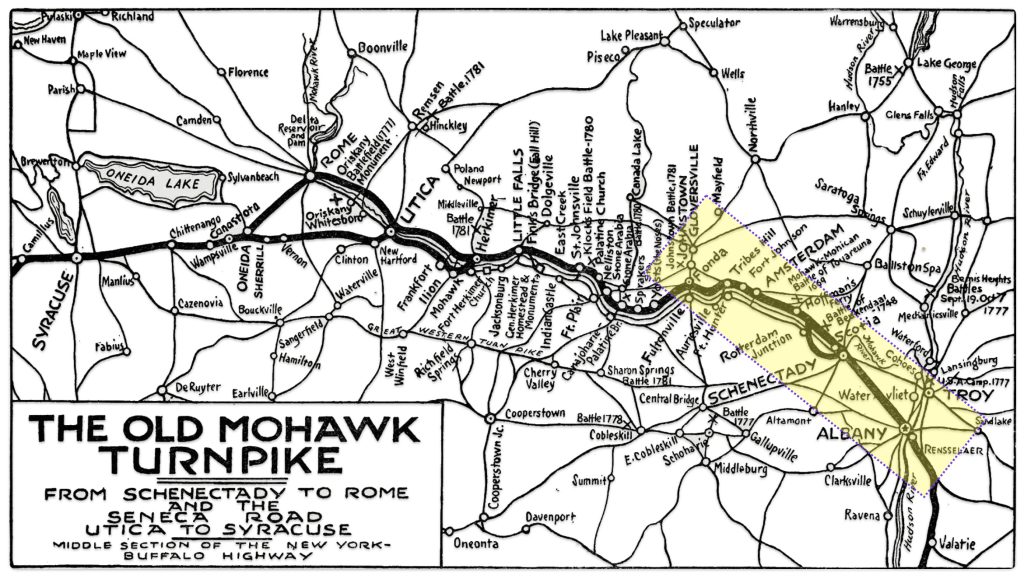

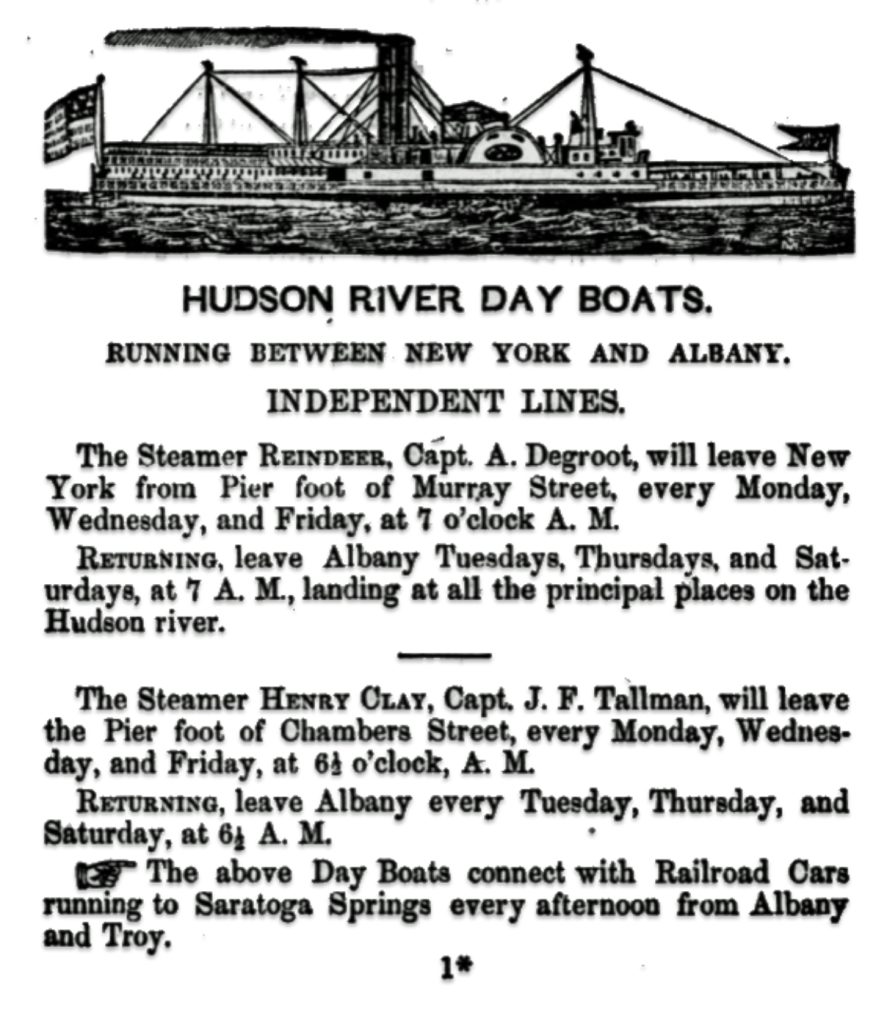

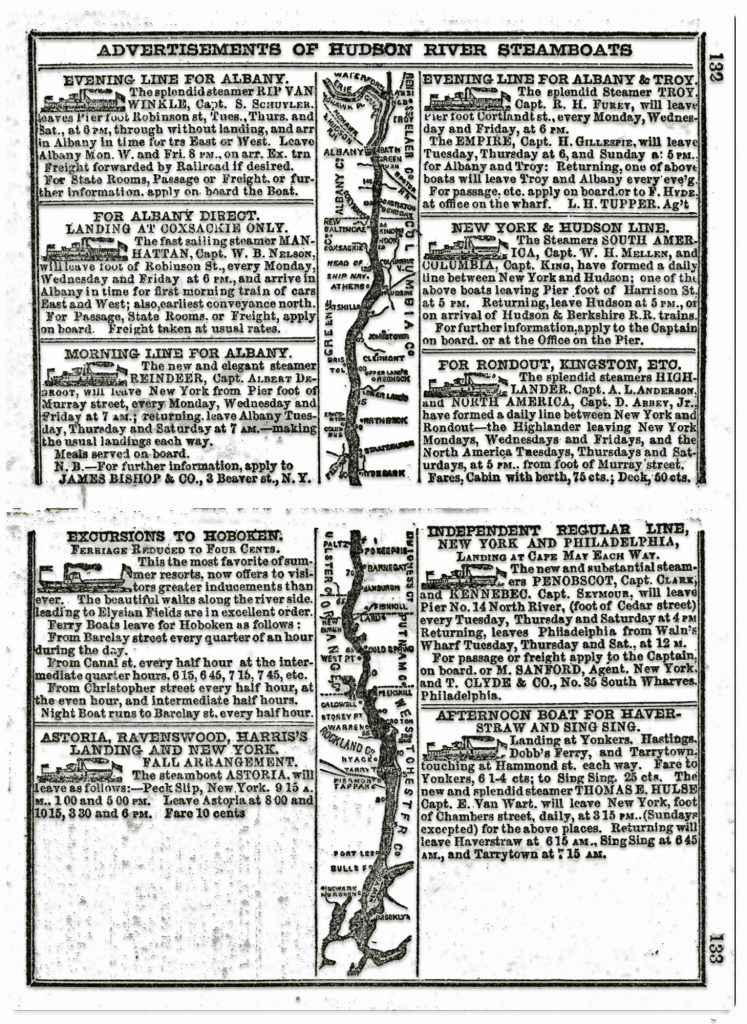

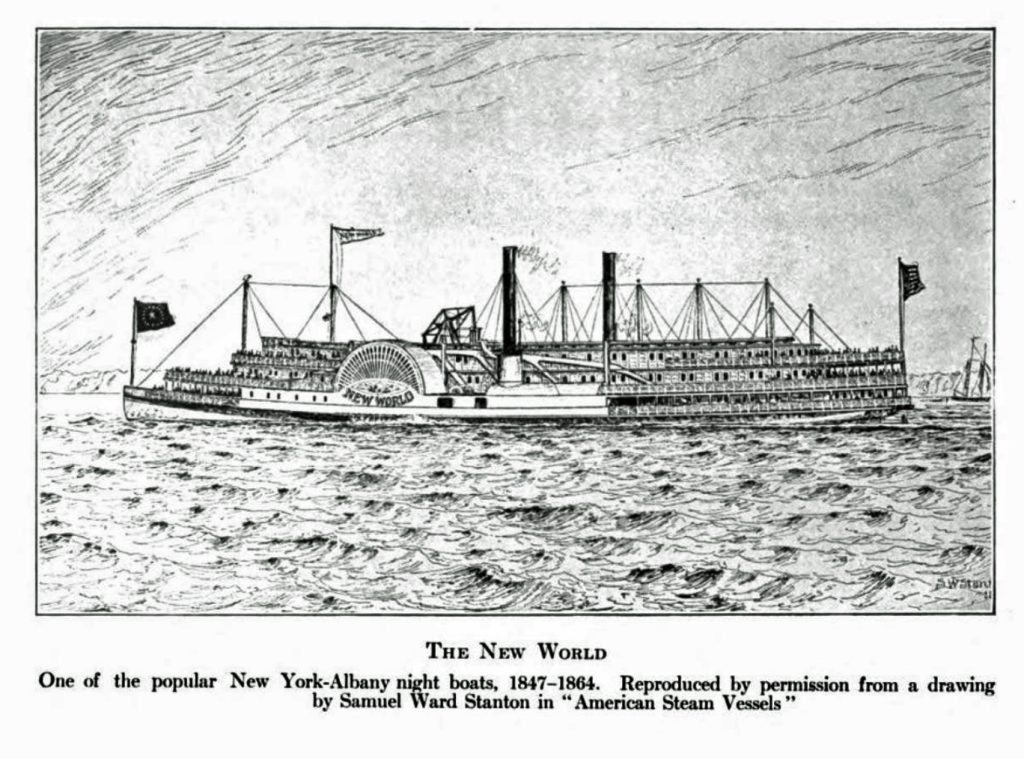

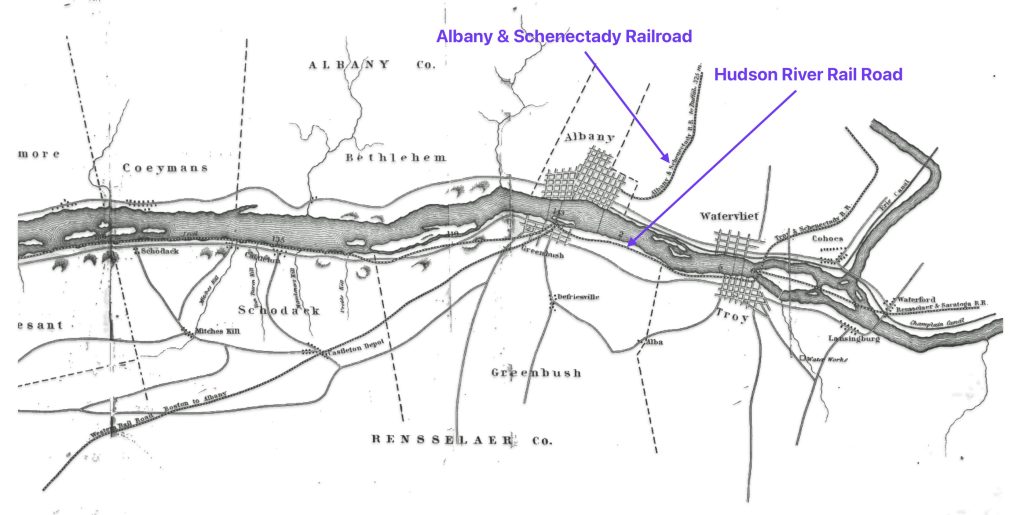

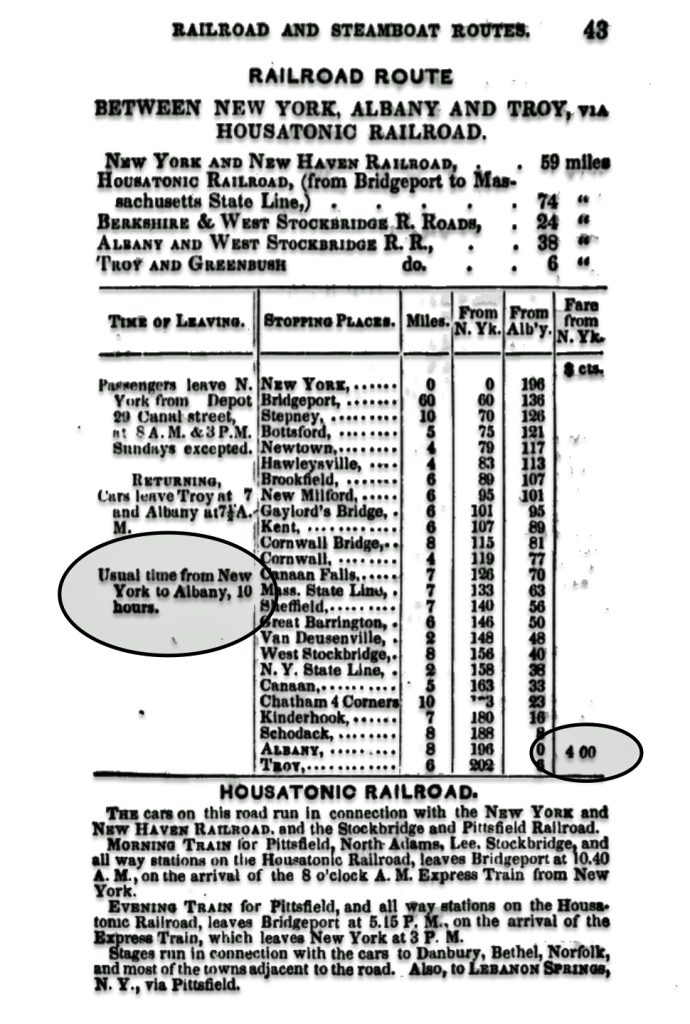

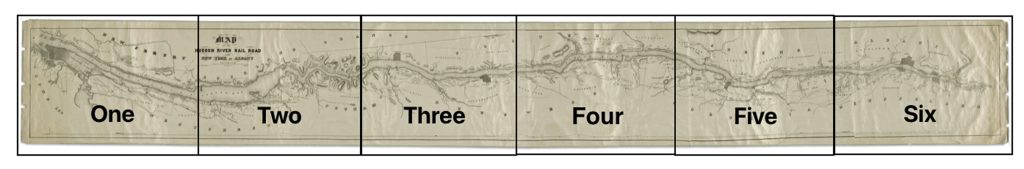

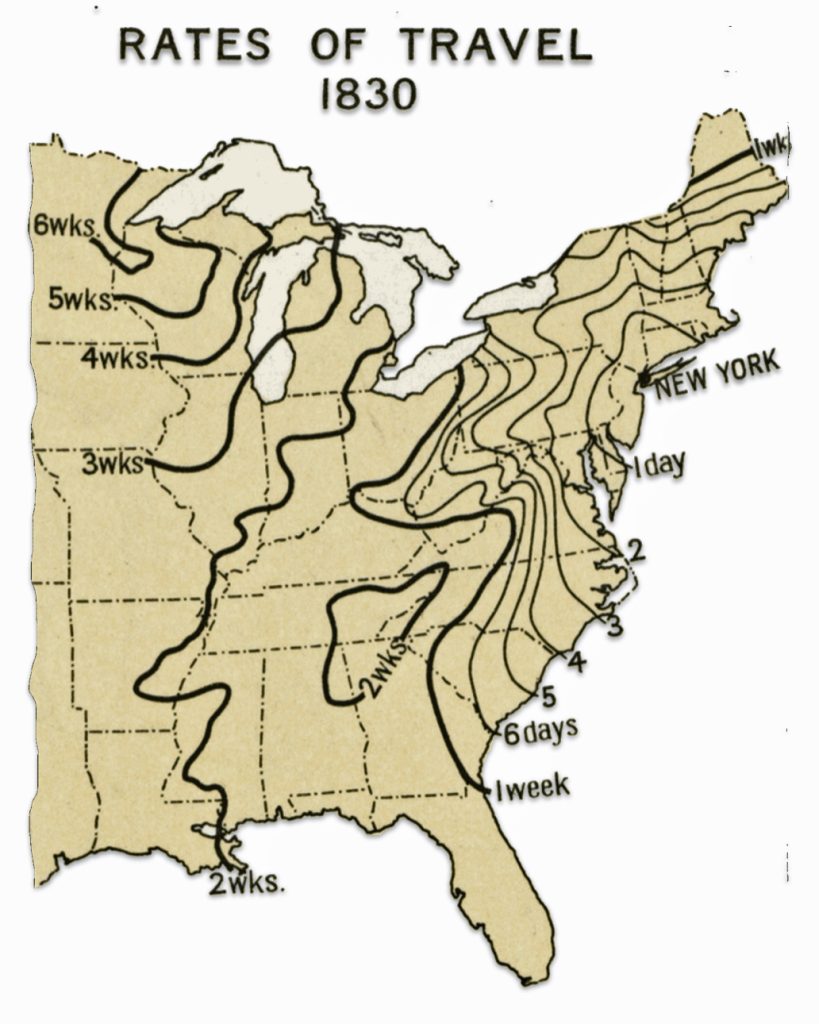

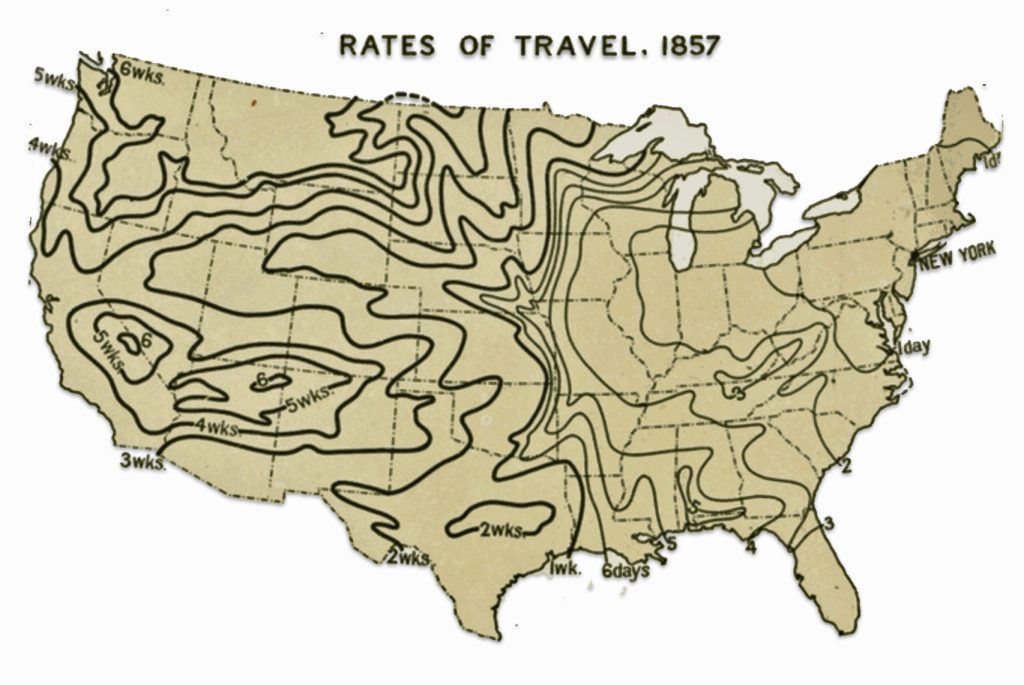

The fifth part of the story covers his travel to New York City and his options to travel to Gloversville, Fulton County, New York.

The sixth part of the story covers his establishing a new life and family in the Johnstown and Gloversville, New York area in the 1850s and 1860s.

The seventh part of the story is about the John’s Family in the context of Gloversville’s development in the 1870s and 1880s and John’s career in the glove making industry.

The eighth part of the story is about the Sperber family in the 1890’s and the twilight of John’s life after the turn of the twentieth century.

The Marriage of John and Sophie

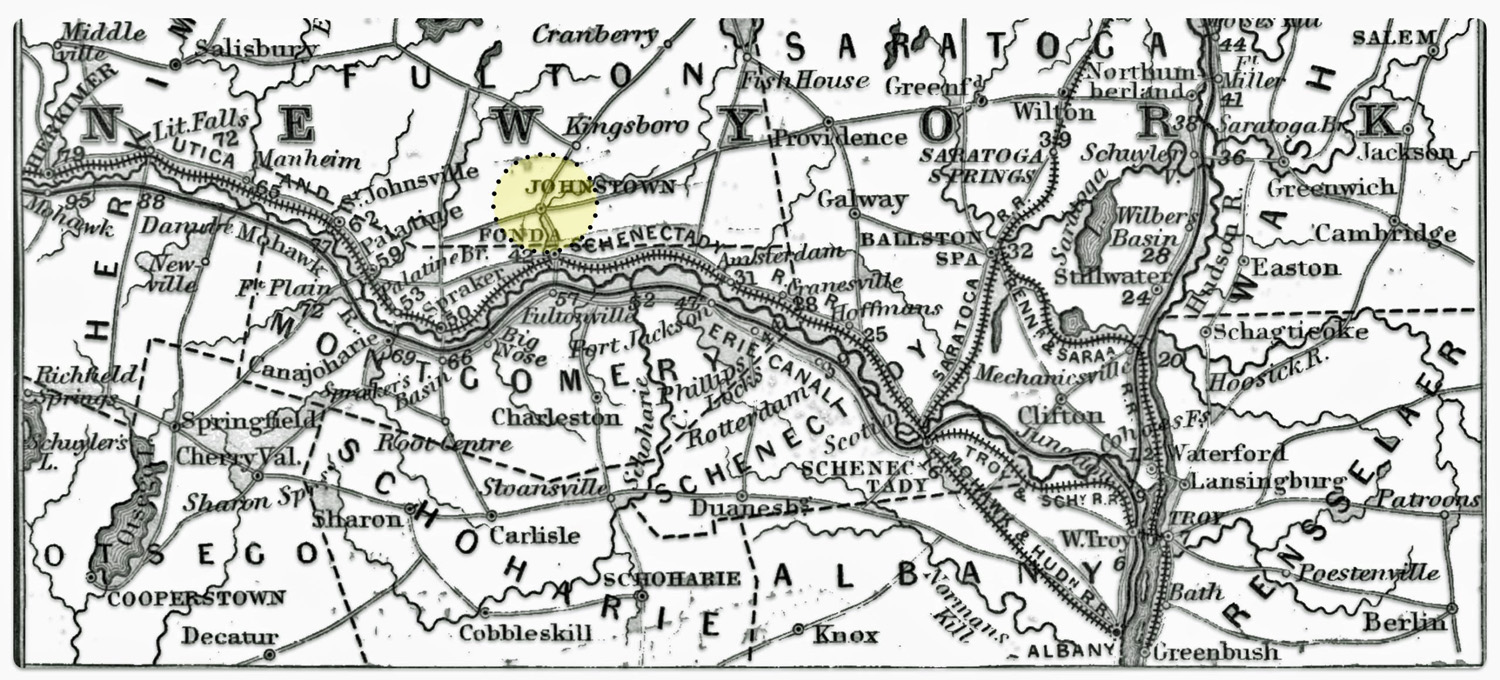

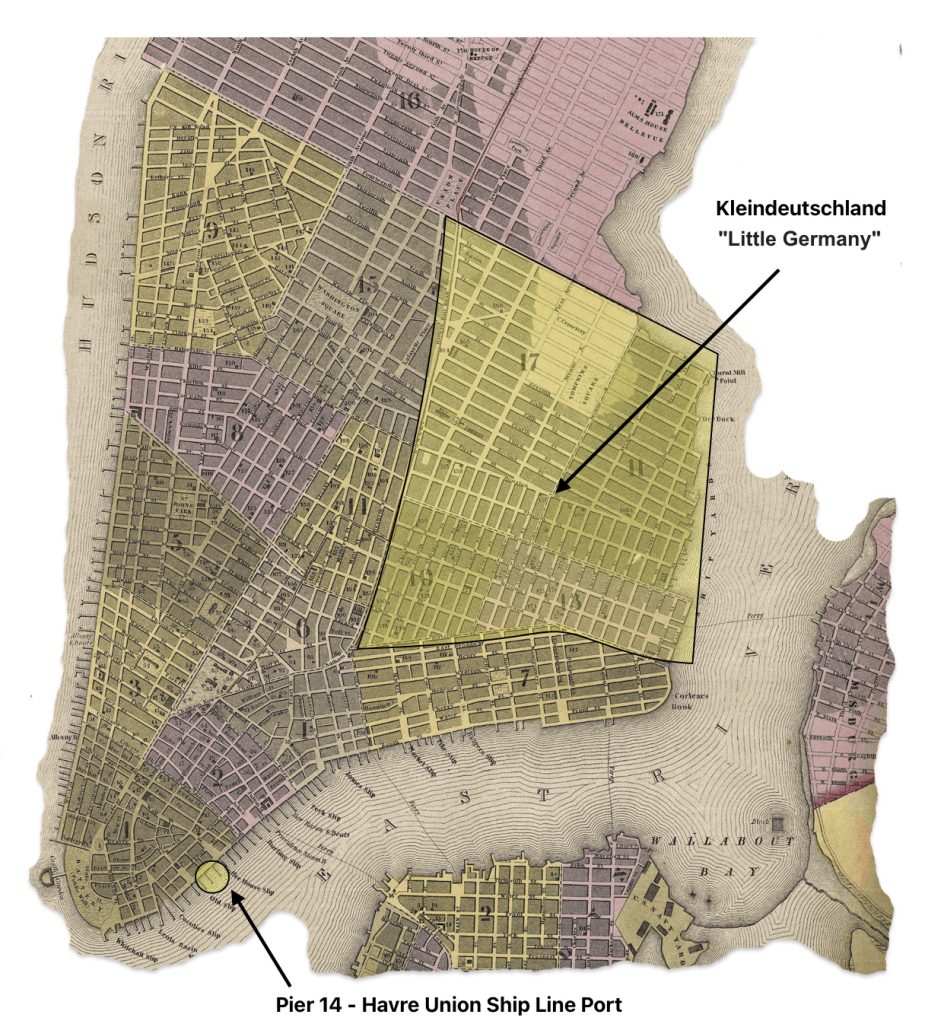

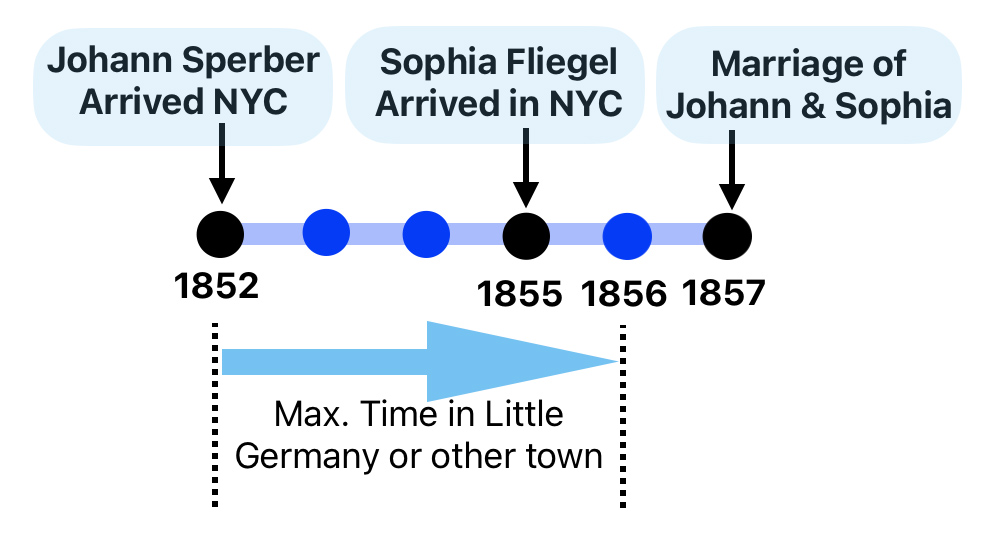

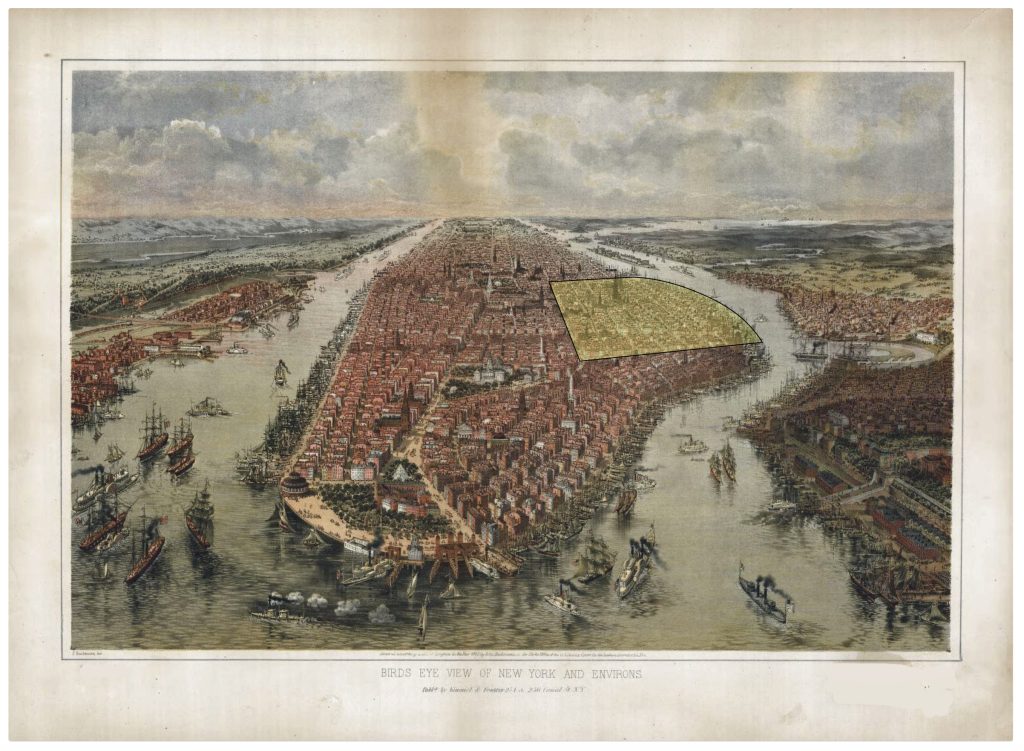

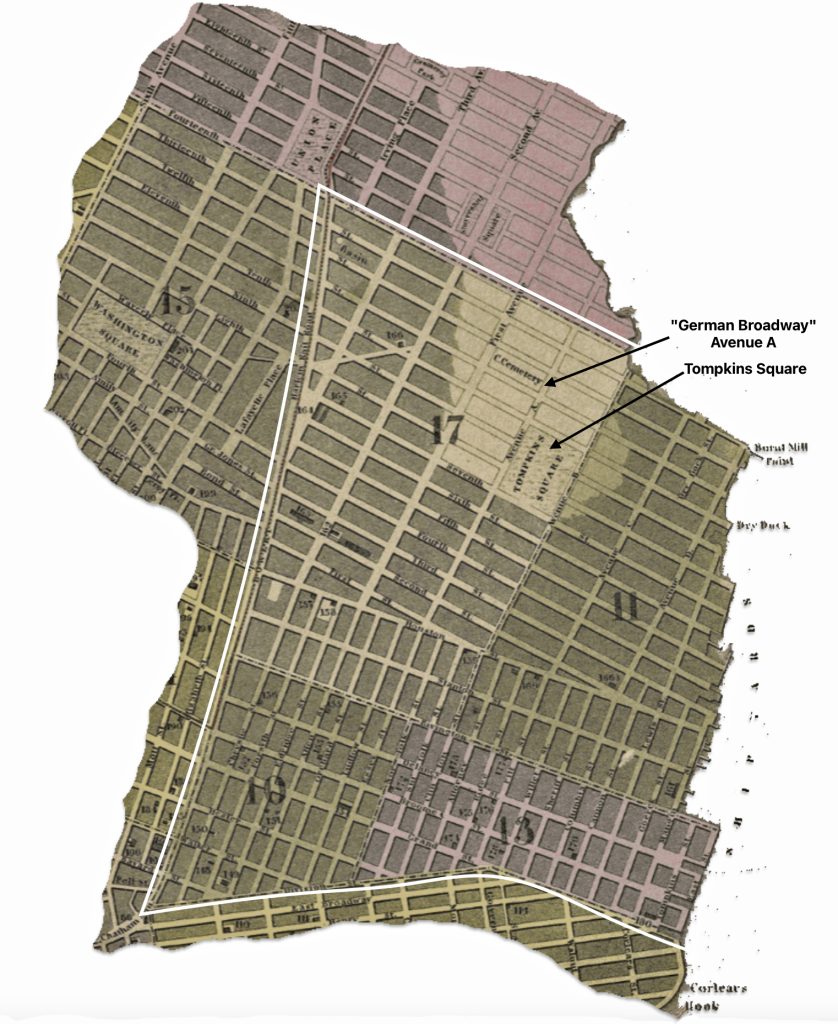

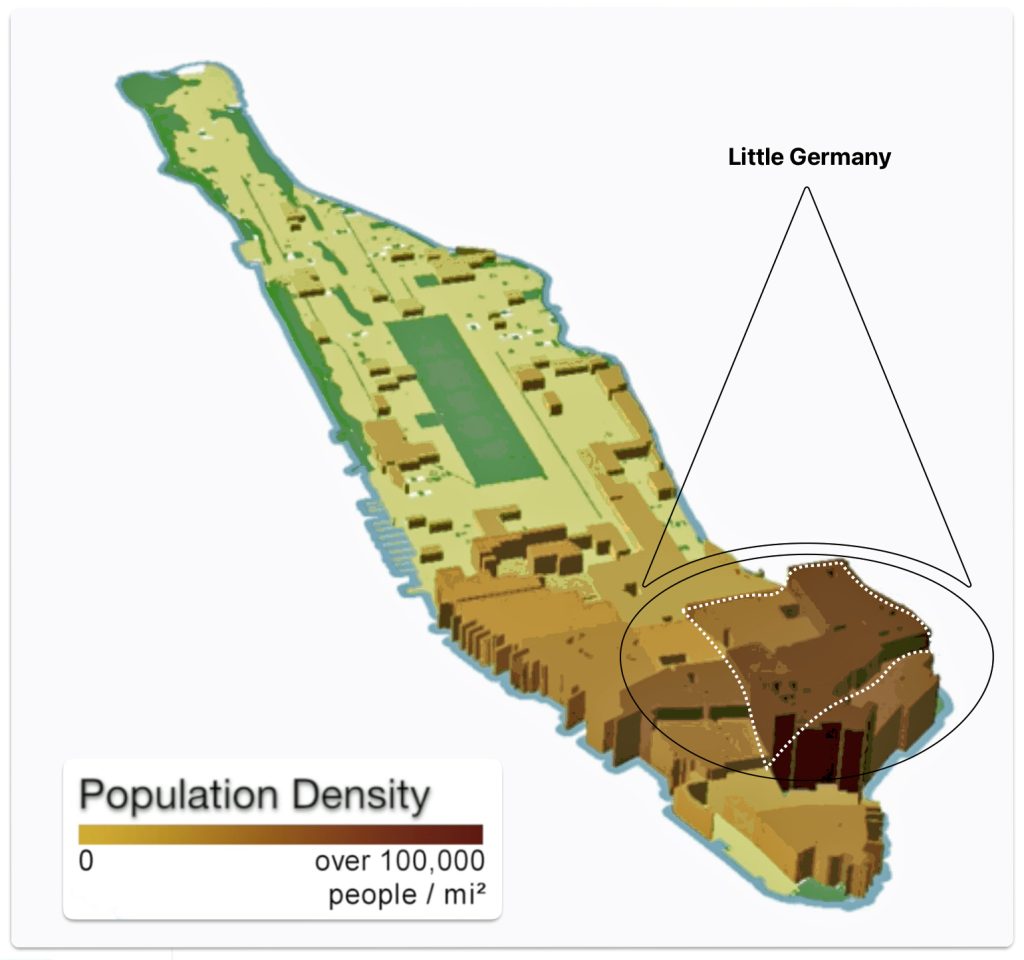

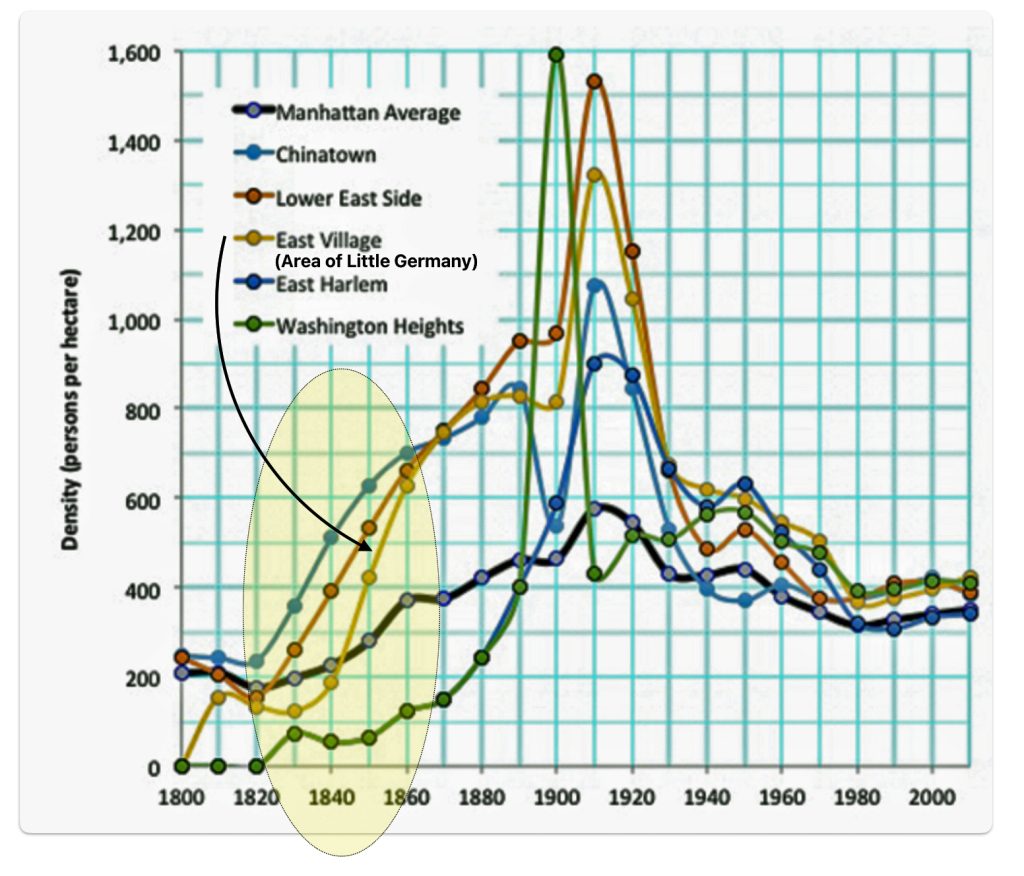

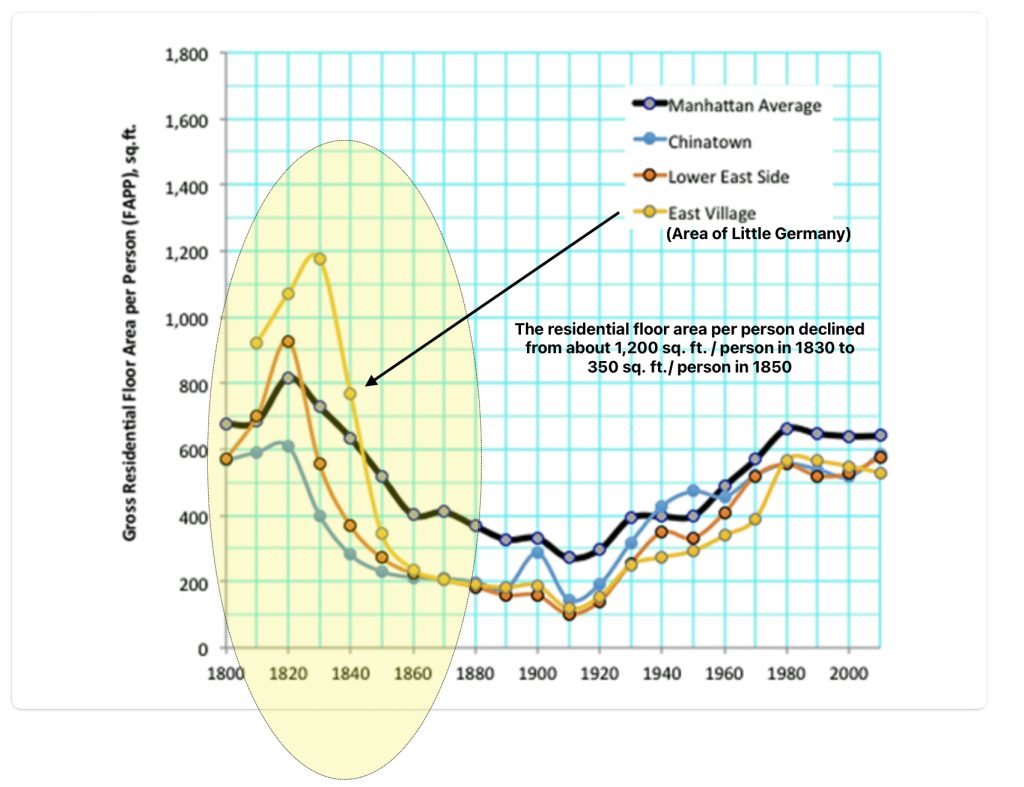

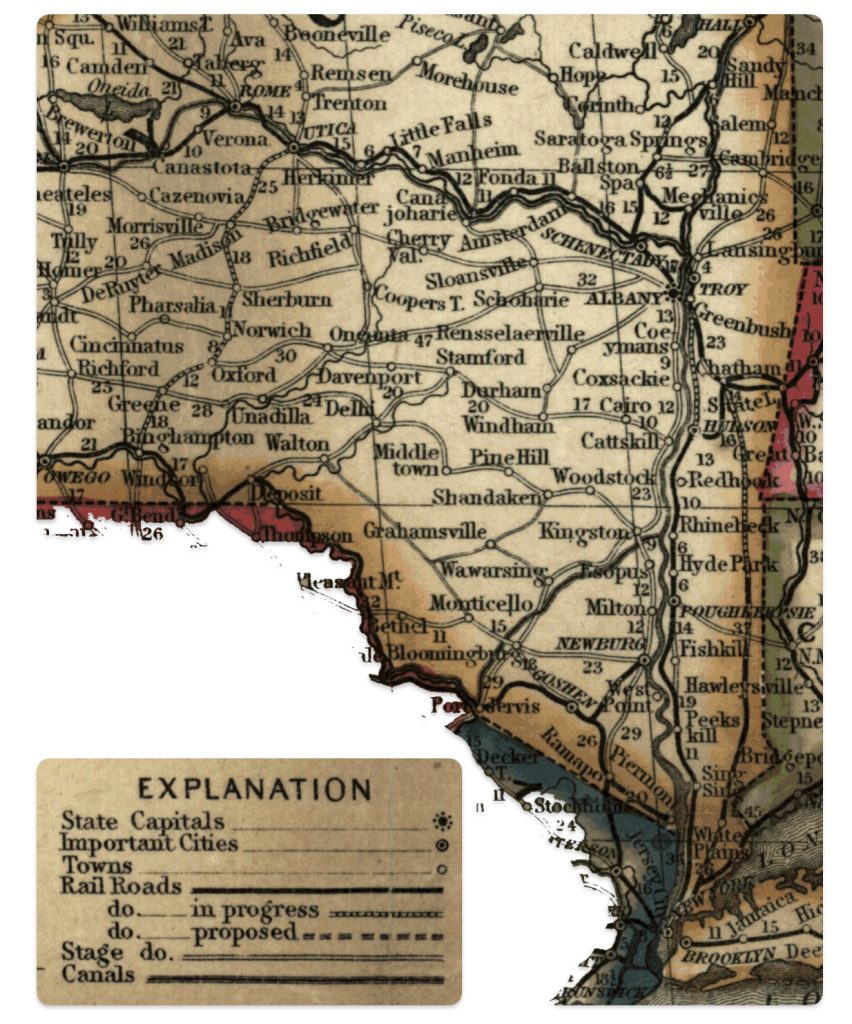

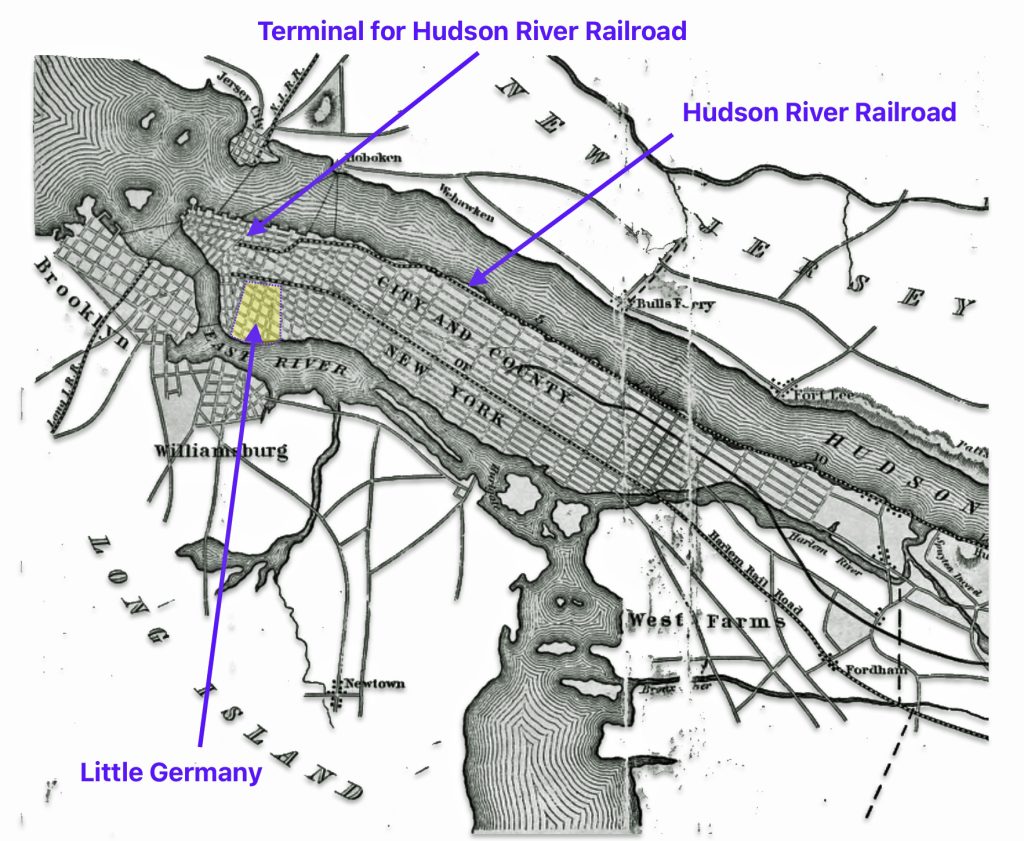

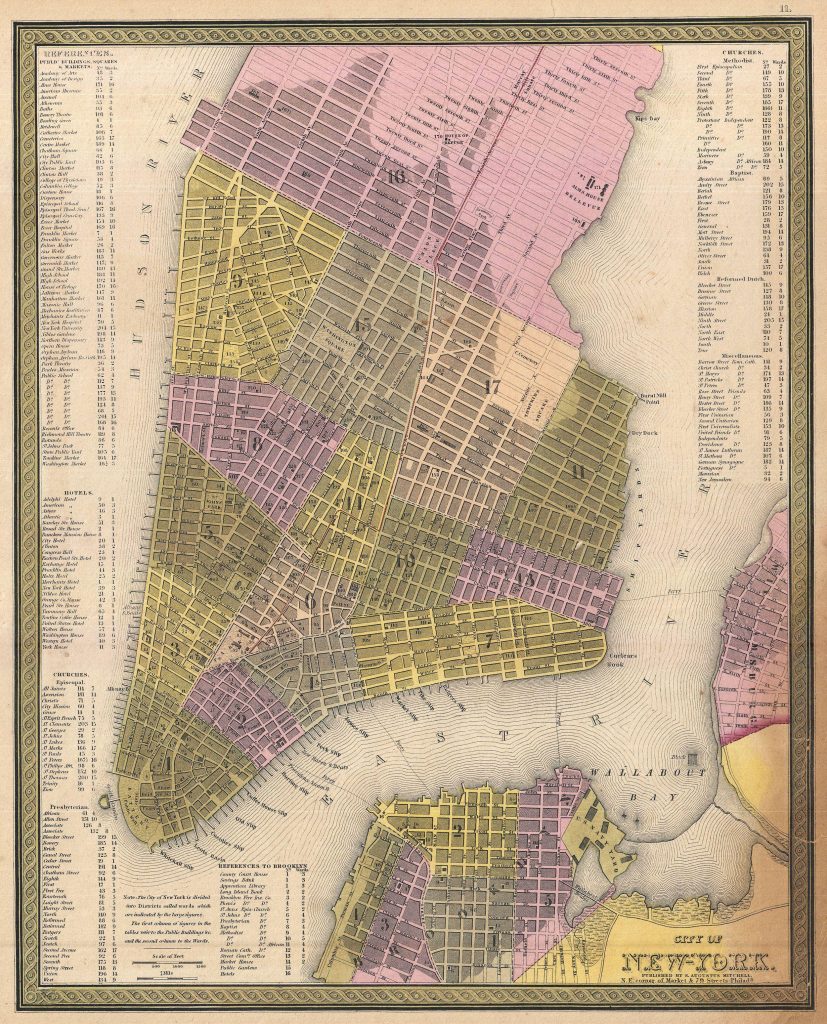

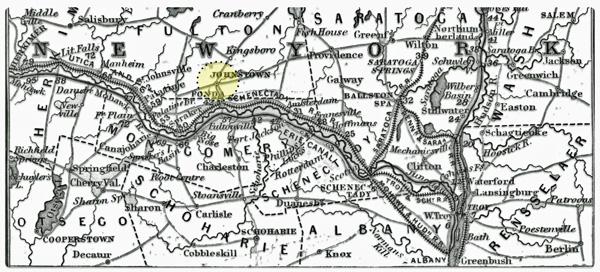

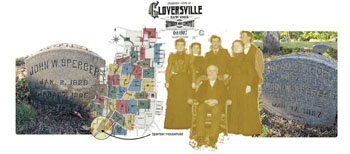

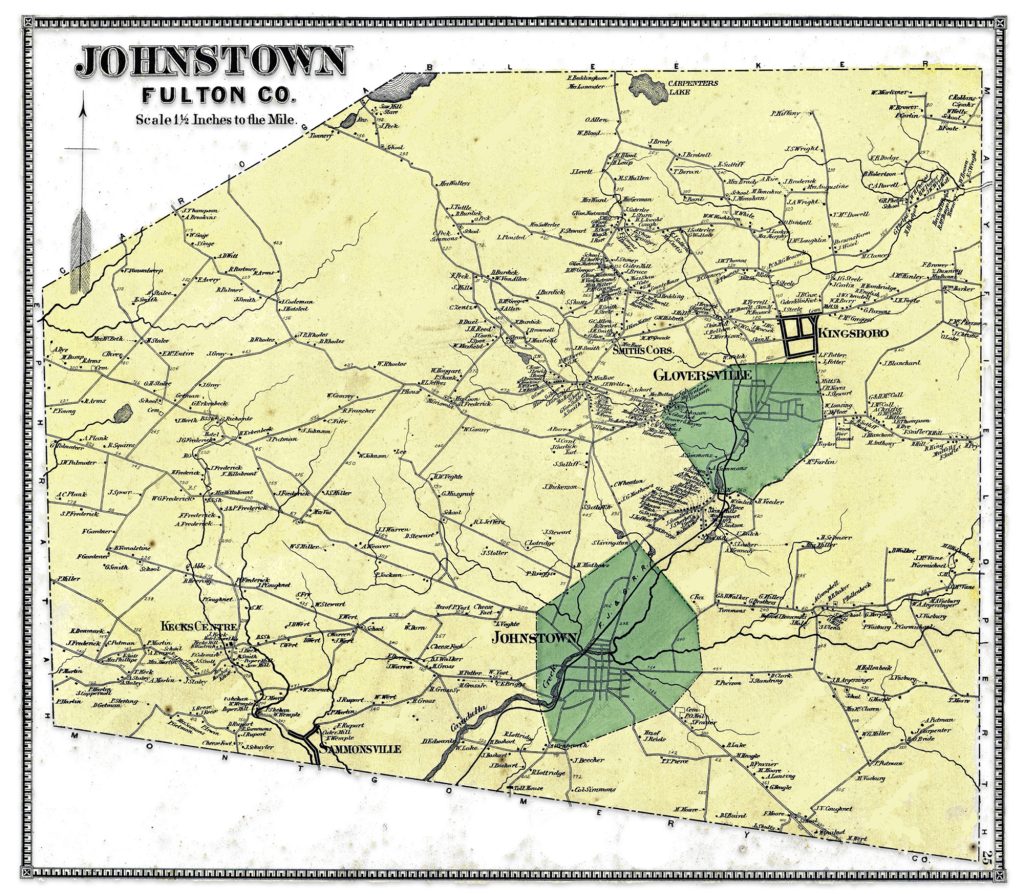

It was Sophie Fliegel’s sister, Catherine, that lead the way for the family and immigrated first to America in 1848. She married Henry Krause in two years of her arrival to America in Little Germany, New York City. They started a family and then moved north to the ‘Village of Gloversville’, which was part of the town of Johnstown in census records, as reflected in map one below. [1]

Map One: One of Nine Towns in Fulton County: Johnstown in 1868

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-6f08-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99/book?parent=29c2ee00-c5f8-012f-95c2-58d385a7bc34#page/1/mode/2up

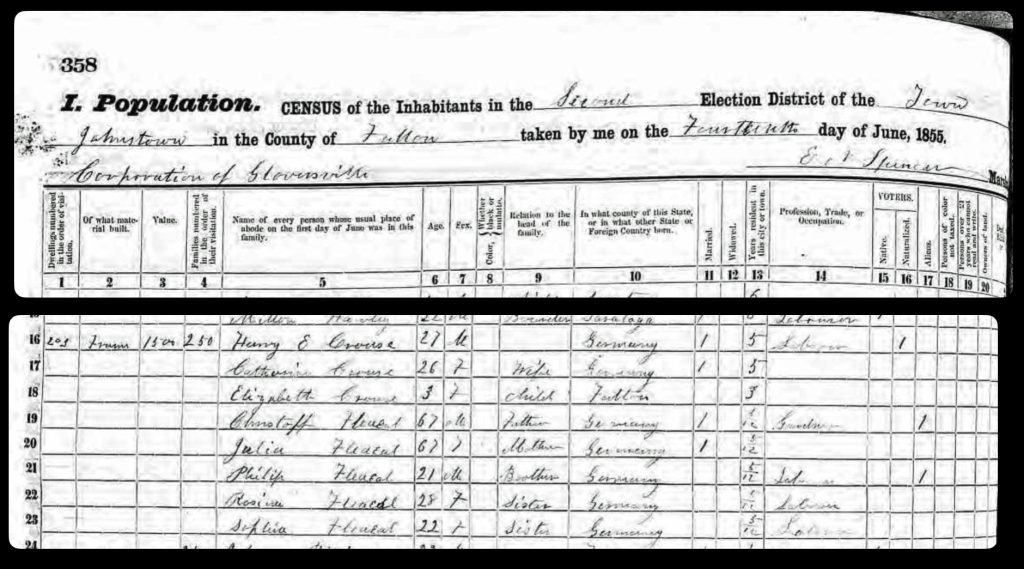

Based on information from the New York state census of 1855, after seven years the entire Fliegel family was reunited in the Gloversville. The parents as well as the three adult children were living with Catherine (Fliegel) Krause and her husband Henry Krause and their three year old daughter Elizabeth.

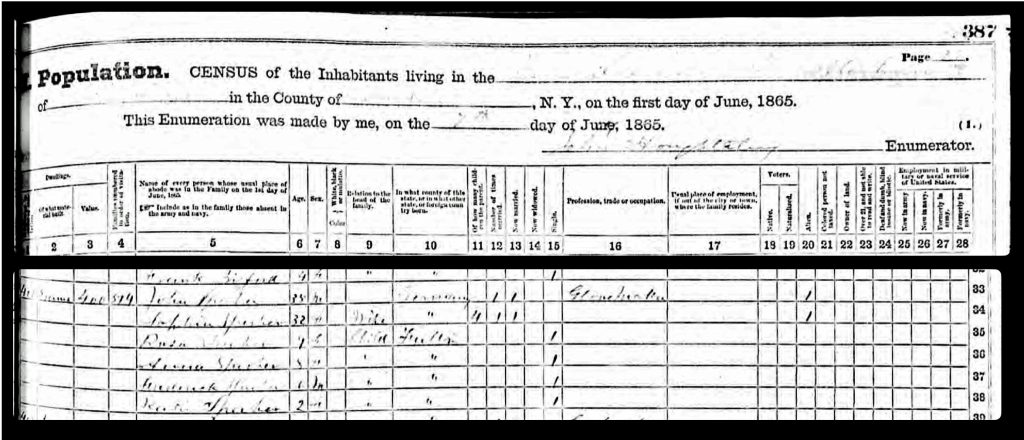

It is interesting to note that column 13 of the 1855 New York census asks how many years the individual lived in the city or town (see below). The information provided to the census enumerator corroborate when each of the family members came to Gloversville based on their migratory patterns.

For the members of the Fliegel family that recently immigrated and arrived in January of 1855, the census corroborates that they were living in Johnstown for five months. The census was taken on June 14th, 1855. Catherine and her family moved to Gloversville in 1850. This fact is also corrobrated in the census tabulation which states the Krause family have lived in Gloversville for five years.

1855 New York Census – Krause and Fliegel Household

As Johann became adapted to American ways of life, he is referred to as John in census records. It is not known if John knew of the Fliegel family prior to his emigrating to the United States. However, only two years after Sophie Fliegel arrived in January 1855 and started a new life with her family in Gloversville, she and John found each other and they married.

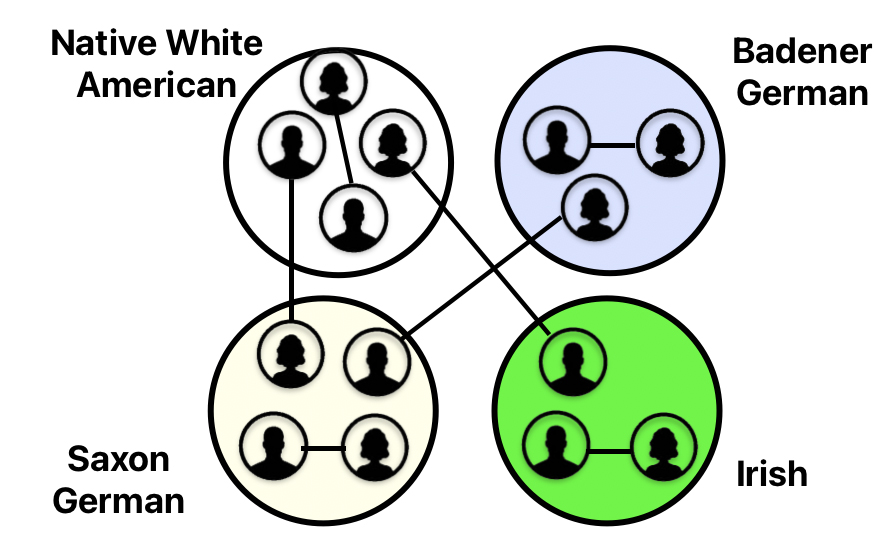

“Selecting a spouse was a far from random matter, even from the point of view of a disinterested observer. Who married whom reveals a good deal about the values of those who immigrated … . First of all, they married their “own kind.”” [2]

Marriage Practices Among German Immigrants

Endogamy is the cultural practice of marrying within a specific social group, religious denomination, or ethnic group.

Exogamy is the cultural practice of marrying outside a specific social group, religious denomination, or ethnic group [3]

Only a severe shortage of suitable candidates within their ranks drove some German immigrants to seek spouses elsewhere.

Social scientists have long used intermarriage as an indicator of adaptation and assimilation of immigrants into the destination country. Various historical and social science studies have found low rates of exogamous marriage (marrying outside of a given ethnic group) among first-generation immigrants but higher rates among their U.S. born children, which has been interpreted as the weakening of cultural or ethnic ties and declining ethic group cohesion among the second generation. [4]

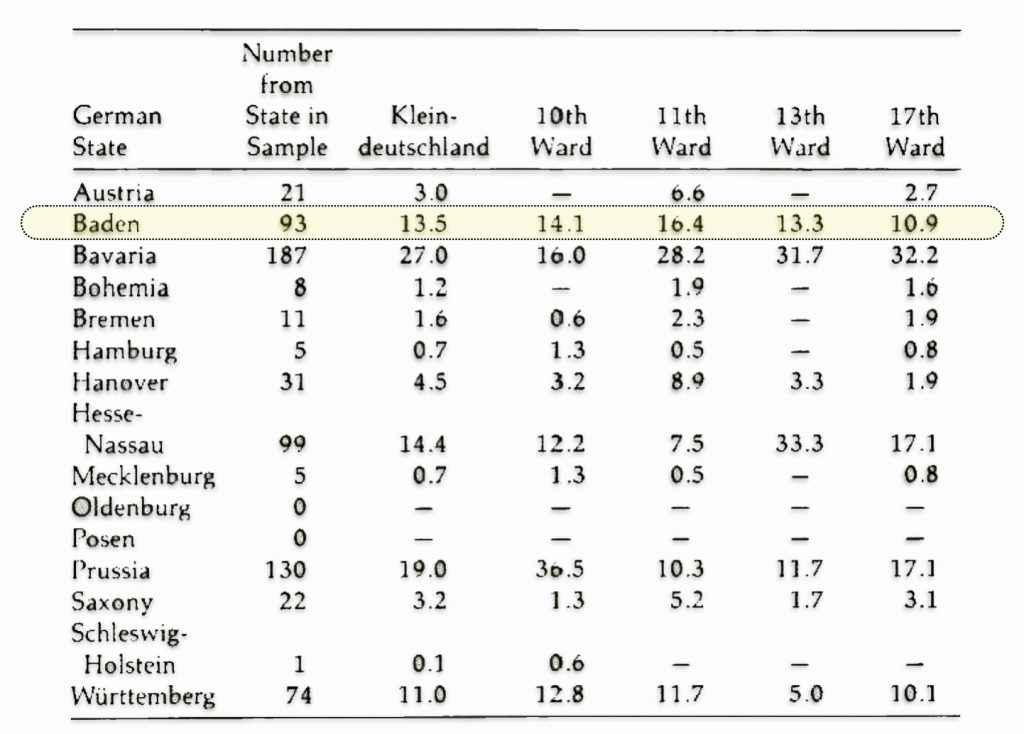

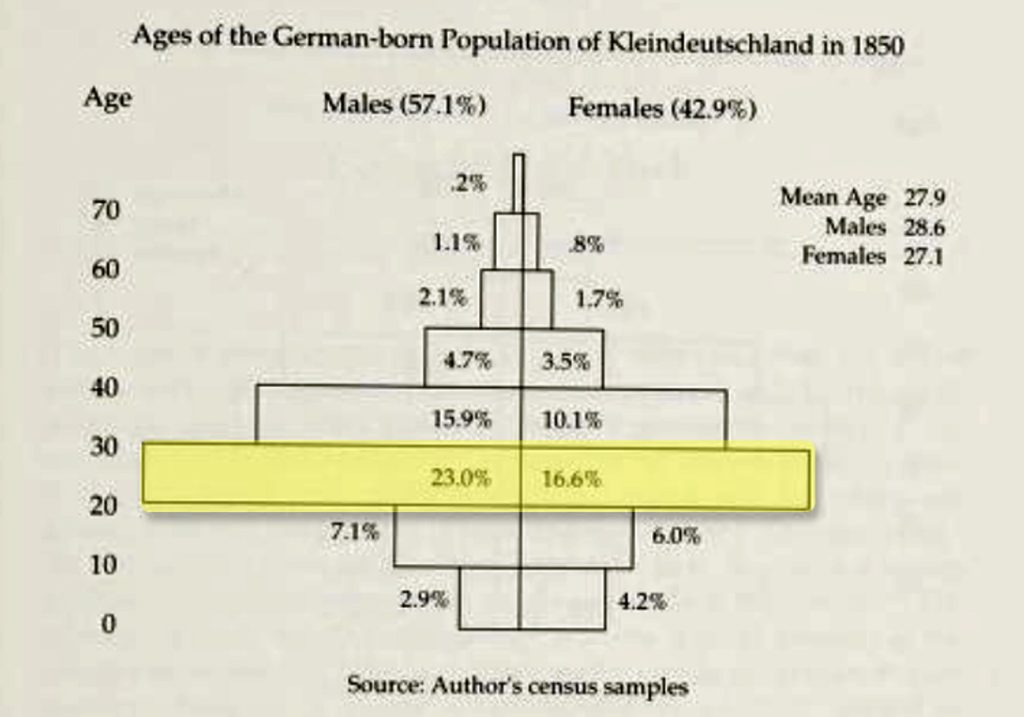

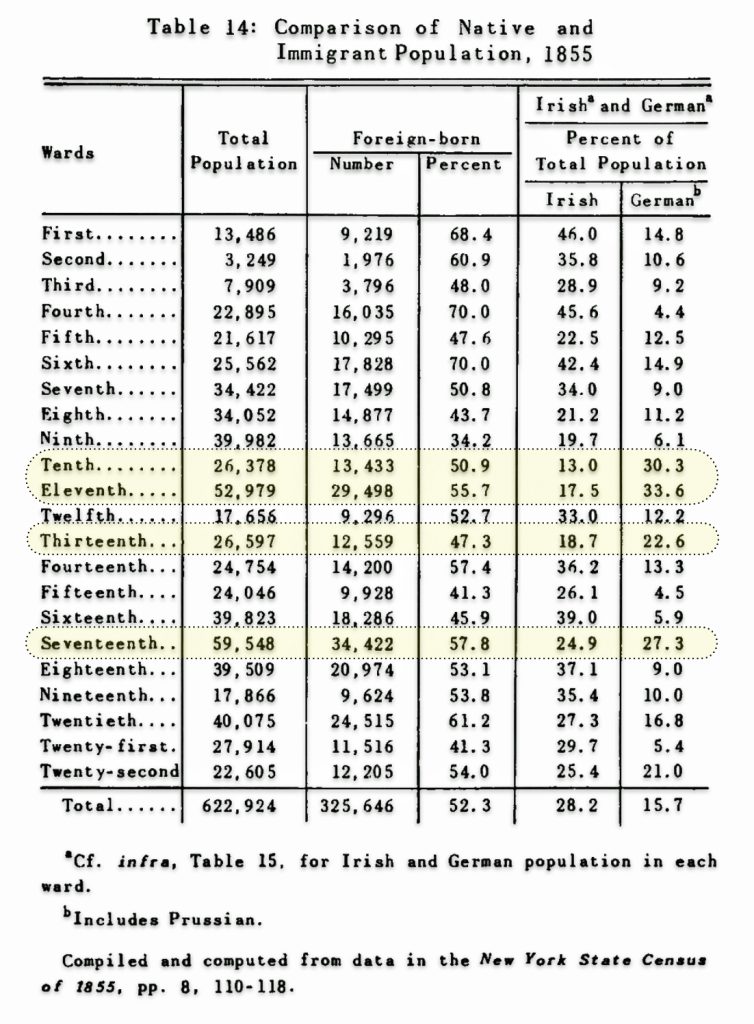

Nadel’s study of marriage patterns in Little Germany between 1840 – 1880 indicated a lower endogamy rate among Germans from Baden. Only 24 percent married other individuals from Baden. However, they had a high endogamy rate of 76 percent of individuals marrying spouses from other German states. [5]

“Linguistic compatibility may have been at least as important in the selection of a spouse, given the relative lack of mutual intelligibility between nineteenth-century German dialects. After all, a couple might want to be able to relax at home and use their native speech.” [6]

The predilection of marrying someone from the same German state or other German states was influenced by a number of contextual factors, such as the relative size and sex ratio (number of males to females) of Germans with in a city or area, how diverse was the population in the area, the share of the native-born white population in the area, and the proportion of life that immigrants spent in the United State. [7]

The marriage patterns of the Fliegel family siblings, based on the ethnic background of their spouses, reflect the general patterns associated with first generation German immigrants in America. Both Johann and Sophie were from Baden. While the spouses of Sophie’s siblings were not from Baden, they were German born in other German states, as reflected in table four.

Table One: Marriages of Fliegel Family Members that were First Generation German Born

| Date of Marriage | Family Member | German State Origin | Spouse | German State Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1866 | Rosina Fliegel | Baden | Louis Knopf | Prussia |

| 1856 | Philip Fliegel | Baden | Magdalen Edel | Würtemberg |

| 1850 | Catherine Fliegel | Baden | Henry Krause | Saxony |

| 1857 | Sophie Fliegel | Baden | Johan Speber | Baden |

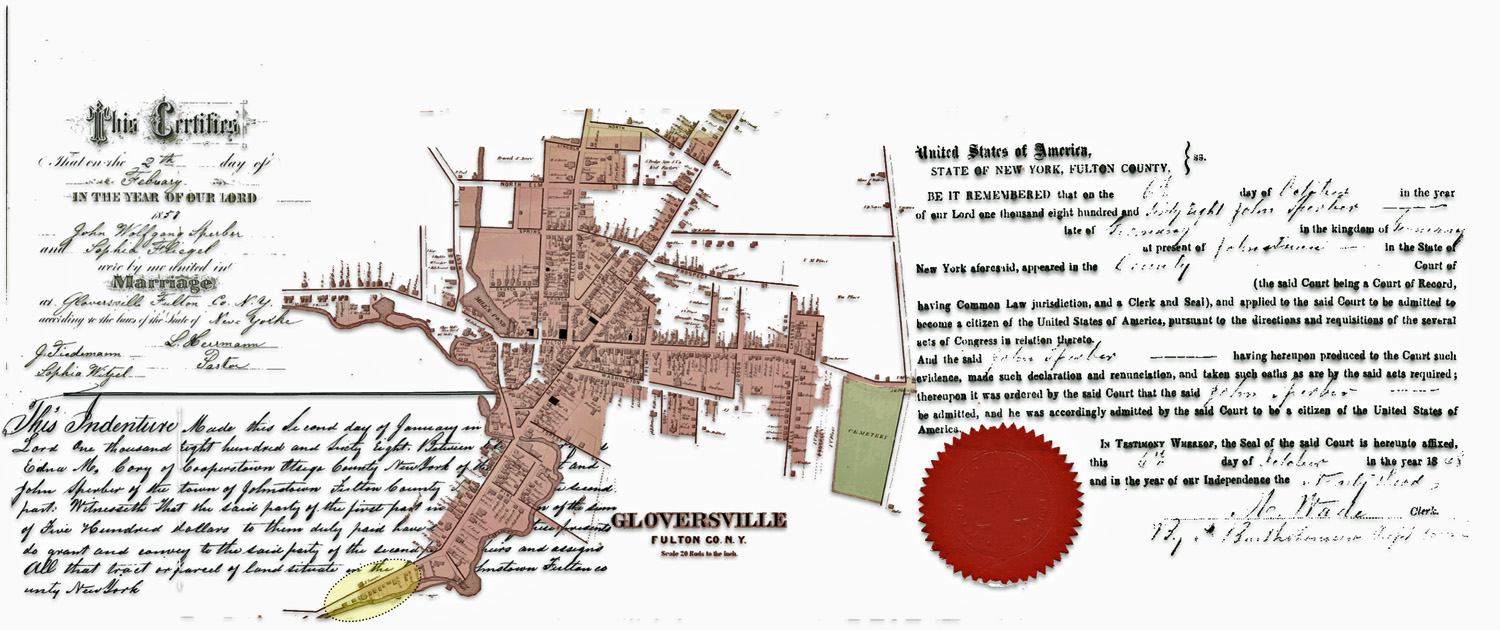

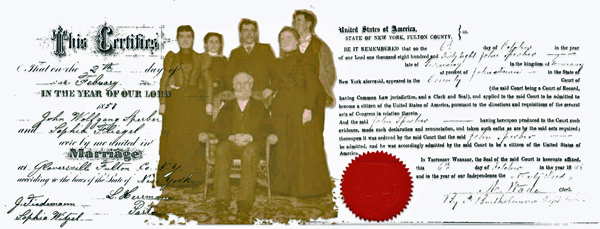

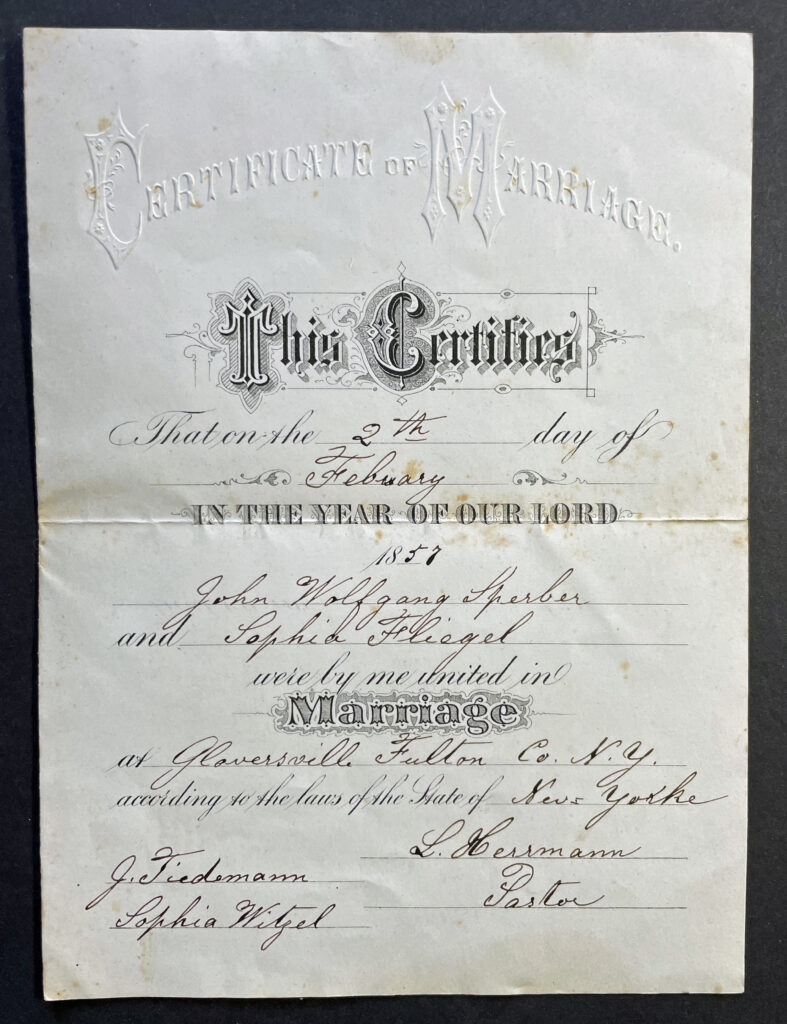

John and Sophie’s Certificate of Marriage (below) indicates that they married on the second day of February 1857 in Gloversville, New York. The certificate has no identifying features that suggest a church or religious affiliation. It is not known if they were married in a church or had a religious ceremony in a home. A pastor, “L. Herrmann”, officiated the ceremony.

Original Certificate of Marriage February 2, 1857

I have been unable to find any information on the pastor “L. Herrmann”. I have possible leads regarding the two witnesses, “J. Tiedemann’ and ‘Sophie Witzel’.

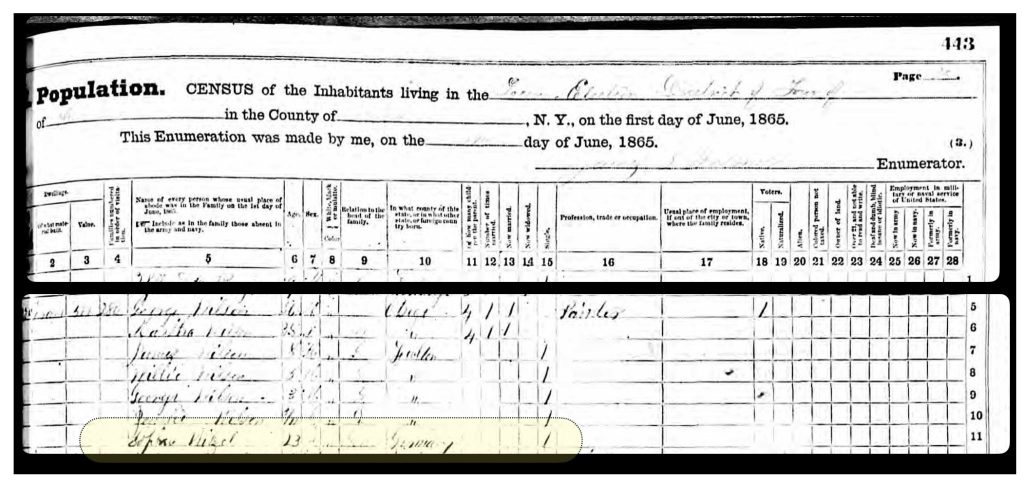

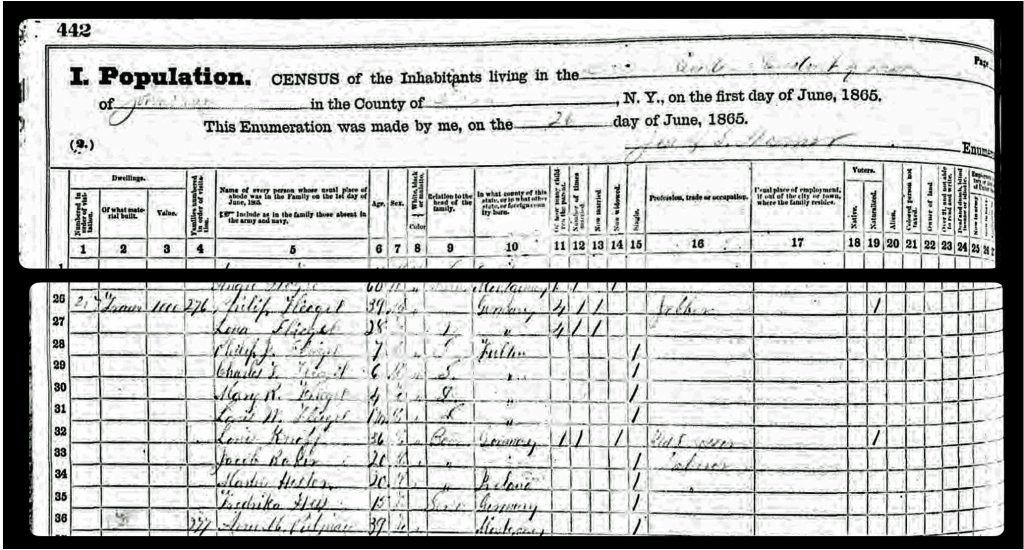

There is a remote possibility that I found Sophie Witzel in the 1865 New York State census. However, this ‘Sophie Witzel’ would have been 15 at the time of the wedding. In 1865 Sophia Witzel was 23 years old in 1865 and was a servant living with George and Martha Wilson who had four children ranging in age from 8 to less than a year. The census Indicates she was born in Germany. in 1865, eight years after the wedding, Sophia Witzel lived close to Philip Fliegel’s household. Based on the census enumerator’s path, the Wilson househld was the 280th house canvassed. Philip Fliegel’s house was the 276th household, four houses away. They essentially were neighbors. [8]

I also found a “J Tiedemann” who was a boarder on a farm in Grand Island, Erie County, in the 1855 New York census. Grand Island is right on the Canadian border near Buffalo and is roughly 255 miles from Gloversville. Due to the distance between the two towns, it is unlikely that this J Tidemann is the witness at Johna and Sophie’s wedding in 1857. [9]

Religious Affiliation of John and Sophie

It is not known if Sophie and John were associated with a specific religious community in the Gloversville area. Johann and Sophia’s families came from northern areas of the Grand Duchy of Baden that were largely associated with the Protestant faith. Their religious affiliation is reflected in the characteristics of prior generations of German immigrants that were from their area of Baden. The first wave of Palatine immigrants in the early 1700s that settled along the Mohawk River were mostly Lutheran. [10]

The German states were far from homogeneous in religious beliefs and practices. The southern areas of the Grand Dutchy of Baden were largely associated with the Catholic faith while the central and northern areas were mostly Protestant. Most of the Protestant Germans belonged to the Lutheran sect with a very minor fraction identifying themselves as Calvinist.

The historical strife in the German states in the seventeenth and eighteen centuries prevented Catholicism or Protestantism to establish itself as a sole religion in a state.

“(E)ach german state established the religion of its ruling house but this sometimes left large portions of the population disaffected and alienated from the state religion. … This religious turmoil often weakened all religious ties in many parts of Germany and hastened the spread of secularization in the nineteenth century. … What especially distinguished German New York from many other immigrant communities was the overwhelming predominance of its secular subcommunities over its religious ones. ” [11]

As early as 1801 there was a German church in the Gloversville area, The Reformed Protestant German Lutheran Church of the Western Allotment of Kingsboro. The church was reincorporated and named the German Lutheran Church of Johnstown in 1810. The Lutherans having no church edifice of their own, were granted the privilege of using St. John’s church until they erected a church in the Gloversville village in 1815. The name of the church eventually changed to the St. Paul’s Church, Johnstown, N.Y. in 1826. I have not found the name ‘Herrmann’ associated with St. Paul’s church. [12]

While it was reported “(i)n 1856, Fulton County contained 3,717 horses, 7 asses and mules, 7,416 milk cows, 1,420 working oxen, 13,484 sheep, 8,239 swine, and 30 churches”, I have been unable to locate evidence of a church that provided marriage services to John and Sophia. [13]

Some churches in the 1850s did not have their own dedicated buildings. It was not uncommon for some churches to worship in houses or other non-church buildings. The 1851 census of churches in the U.S. counted both churches with dedicated buildings as well as those without. It found 38,061 total churches, of which 3,130 (8.2%) were “halls, schoolhouses, private houses, etc.” used for worship in the absence of a church edifice.

“A church to deserve notice in the census must have something of the character of an institution. It must be known in the community in which it is located. There must be something permanent and tangible to substantiate its title to recognition. No one test, it is true, can be devised that will apply in all cases … . It will not do to say that a church without a church building of its own is, therefore, not a church; that a church without a pastor is not a church; nor even that a church without membership is not achurch. There are churches properly cognizable in the census which are without edifices and pastors, and, in rare instances, without a professed membership. Something makes them churches in spite of all their deficiencies. They are known and recognized in the community as churches, and are properly to be returned as such in the census.

“On the other hand, there are hundreds of churches borne on the rolls of religious sects having botb. a, legal title to an edifice ancl a nominal membership, wbich never gather a congregation togetber, support no ministry, and conduct none of the services of religion.”[14]

Starting Their Family

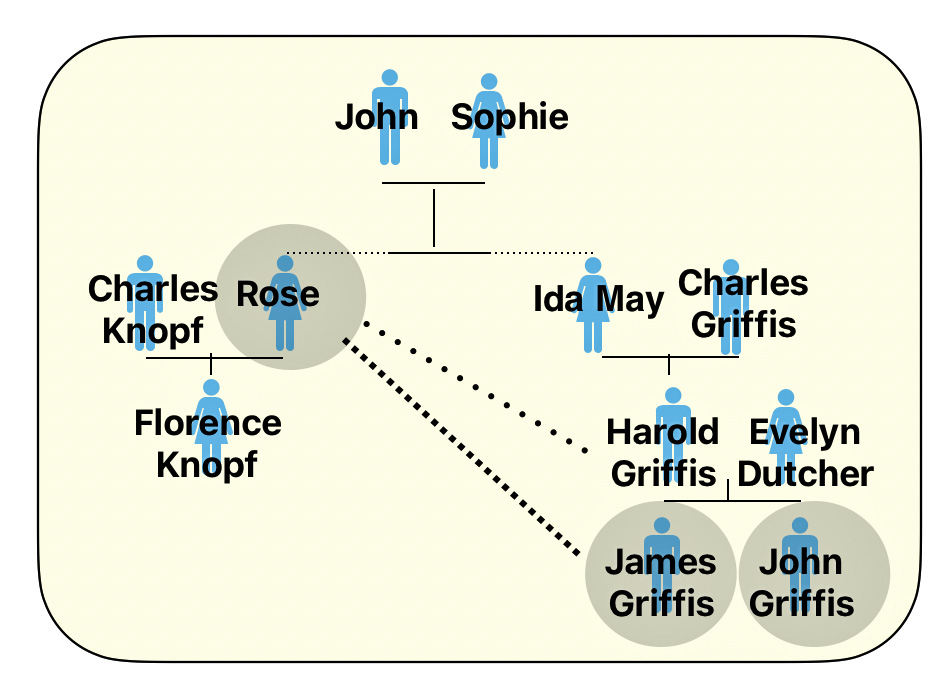

An interesting fact about the start of John and Sophies’ family involves ‘their’ first child Rose Sperber.

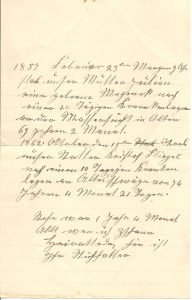

Rose was born in October 1855. This implies that Sophie was pregnant when she was traveling to the United States. There are no records to suggest that Sophie was married at the time of her departure from Europe.

Rose was born out of wedlock and her biological father is not known. In a personal note written by Sophie after both of her parents had passed away, she mentioned that “Rose was one year and four months when I got married to Johann, he is her stepfather.”

It appears that Rose Sperber was conceived around the time of Sophie Fliegel’s arrival to the United States, at the beginning of 1855. [15] Sophie arrived in the United States from Germany with the family on January 26, 1855. There is no mention of an infant or a child under one year old on the ship manifest list. It is not evident that Sophie had a prior marriage. She still had her maiden name when she married John Sperber in 1857.

Regardless of the sensitivity of out of wedlock births, Sophie and John lived within a time period where illegitimacy rates were high and in many communities out of wedlock children were accepted and treated equally. The reason for the increased illegitimacy rates in Europe and the United States are subject to academic debate but they nevertheless existed. [16]

“The illegitimate fertility rate soared between 1750 and 1850, from one end of Europe to another.. In all but a handful of villages and cities for which data are available, illegitimacy rose, departing from modest plateaus of one to three percent of all baptisms, to often ten or fifteen per cent. Also prebridal pregnancy, women who are already pregnant when they marry, climbed dramatically. The percentage of first children born less than eight months after marriage in parish register data also rose along with illegitimacy in most places.” [17]

Rose’s biological father is not known. It is assumed that Sophie lived with her daughter in her father’s home prior to marriage. Within a year, she met and had a short courtship with John, they fell in love, they were married and started their family. Rose was accepted as John’s own daughter.

The First Child of the Sperber Family in America: Rose Sperber

To provide some historical context of who was Rose Sperber, according to oral family history and personal correspondence, Rose (Sperber) Knopf had a close relationship with her nephew Harold Griffis. When he was in college, Harold corresponded with his Aunt Rose. She was very proud of her nephew’s accomplishments.

Based on oral family history, Rose was a ‘favorite’ great aunt of James and John Griffis, sons of Harold and Evelyn Griffis. In the 1940s, both young James and John eagerly anticipated aunt Rose’s visits from New York City. As a married adult, Rose lived in New York City and she would visit the young boys living in Gloversville and Troy. The young boys were always excited to have Rose come to town. She would take them to movies, bring gifts from the big city of New York, and create wonderful memories with her grand-nephews.

Portrait of Rose Sperber Knopf

Source: Family Archives, photograph circa 1920’s

Establishing a home in the late 1850s & into the 1860s

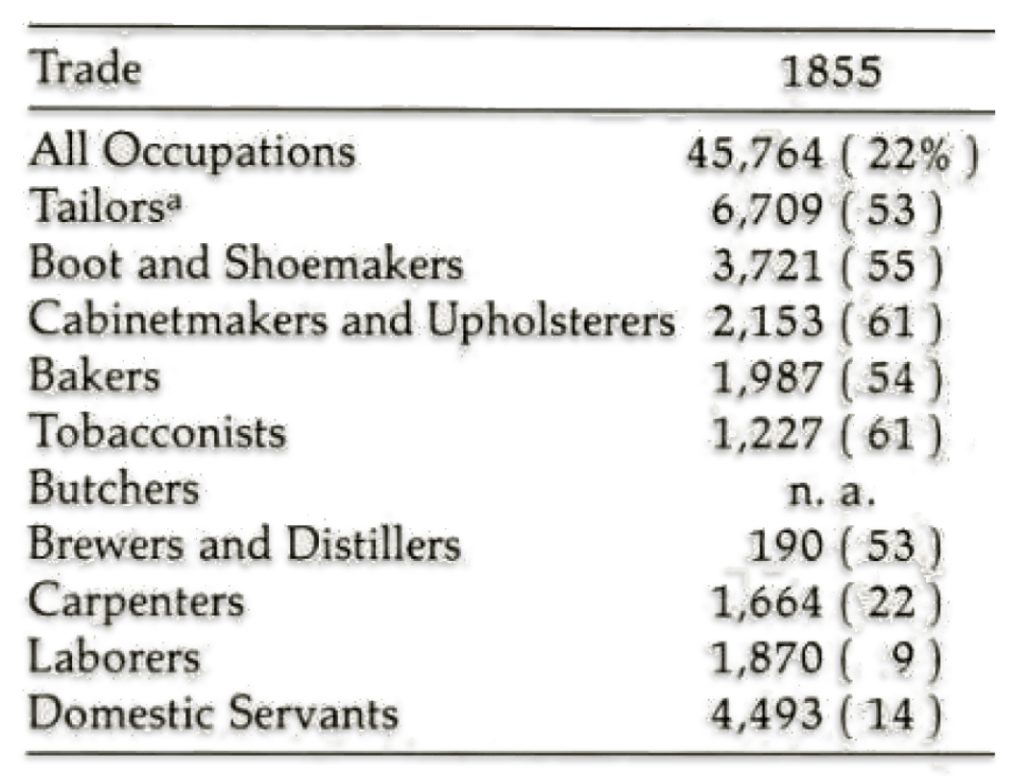

When Sophie FliegeI and Johann Sperber arrived in the Gloversville – Johnstown area in the mid-nineteenth century, Gloversville was becoming a major center for leather tanning and glove manufacturing, industries that would dominate its economy for the next century. The village of Gloversville incorporated in 1853 as the glove industry expanded. Local business directories from 1856 show a variety of merchants in dry goods, groceries, drugs, clothing, and other goods and services catering to the growing population. [18]

By 1859, four-fifths of Gloversville’s inhabitants were directly or indirectly involved in the glove trade. Over $500,000 in capital was invested in the industry. Large tanneries and glove shops employed a significant portion of Gloversville’s workforce. Despite the growth of larger glove making shops, home workers and shops continued to sew the gloves from leather cut in the factories. Related businesses like box makers, sewing machine repair, and thread dealers emerged to support the glove industry. [19]

“(T)he manufacture of gloves never became one of mass production. The creation of each pair of leather gloves was the work of an individual craftsman. “The Glove Cutter” was personally responsible for the quality of his product. A middle management level was never developed in the glove industry. Each owner of any one of dozens of glove companies, both large and small, had a personal relationship with his “cutters” and sewers or “makers”.” [20]

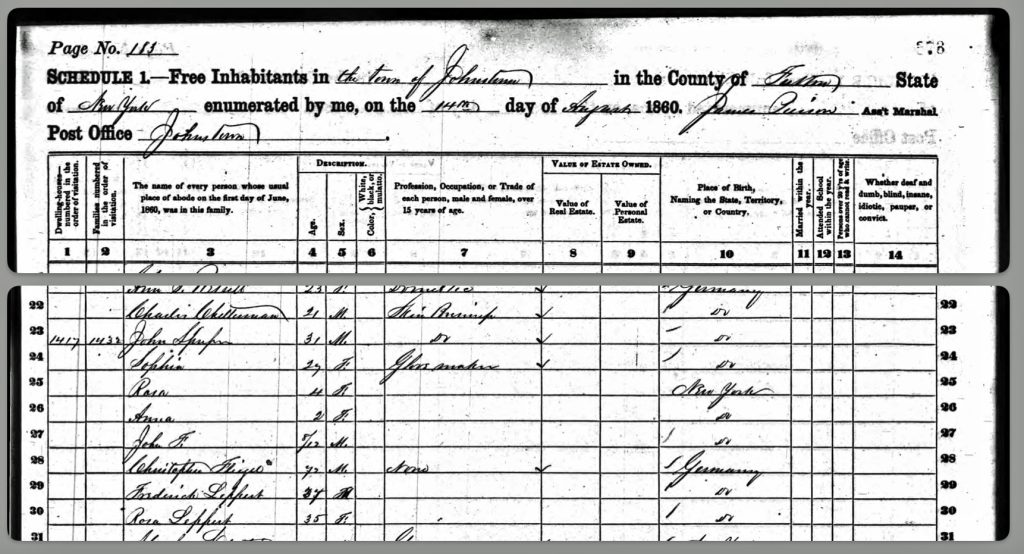

The 1860 U.S. Federal Census captured a snapshot of the young family of John and Sophie Sperber (see below). John is listed as 31 years old and Sophie is 29. Rose is reported to be 4 years old and their second child, Anna, is 2 years old. John Frederick Sperber, their first of two sons, is reported to be 8 months old in August 1860. John indicated his occupation was in the ‘skin business’ and Sophie was a glove maker.

It is also interesting to note that John’s father-in-law Christopher Fliegel, age 72, is living with the young couple. The household also has two boarders living with them: Frederick and Rosa Leppert who are in their mid 30s. Both of the boarders were also born in Germany.

1860 U.S. Federal Census – Sperber Household

Source U.S. Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Johnstown, Page 183 Lines 23 -28

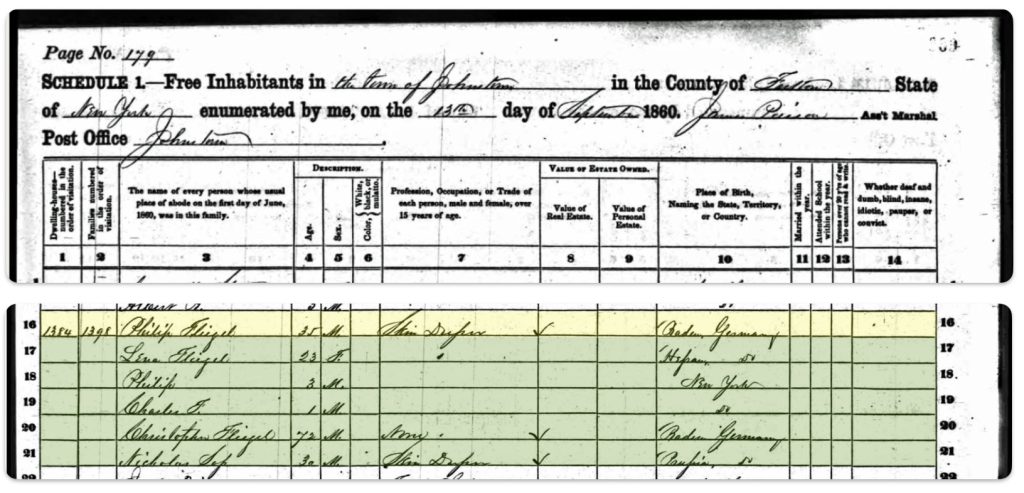

An interesting observation in the 1860 census is the comparison of John Sperber’s household with the household composition of Philip Fliegel’s family, Sophie’s brother. The father, Christopher Fliegel, is listed in both households! (See line line 28 in the 1860 Federal Census above and line 28 in the Federal census below.)

It is difficult to determine how close each household was located to each other since street names are not provided. John’s household was the 1,432nd household canvassed by the census enumerator. Philip’s household was the 1,398th household canvassed by the census taker. The difference of 34 households is not much given the size of Johnstown – Gloversville. The two households were probably two or three streets between each other. It appeared that Philip Fliegel may have stayed at either of the households.

1860 U.S. Federal Census – Philip Fliegel Household

Christopher Fliegel was a widower in 1860. Five years prior, he and his wife immigrated to American with his wife and three adult children. As discussed above, he ended up living with their daughter Catherine and his family. After the death of this wife, Juliana, in 1867, he lived with the households of either his son Philip or daughter Sophia – both multi – generational households.

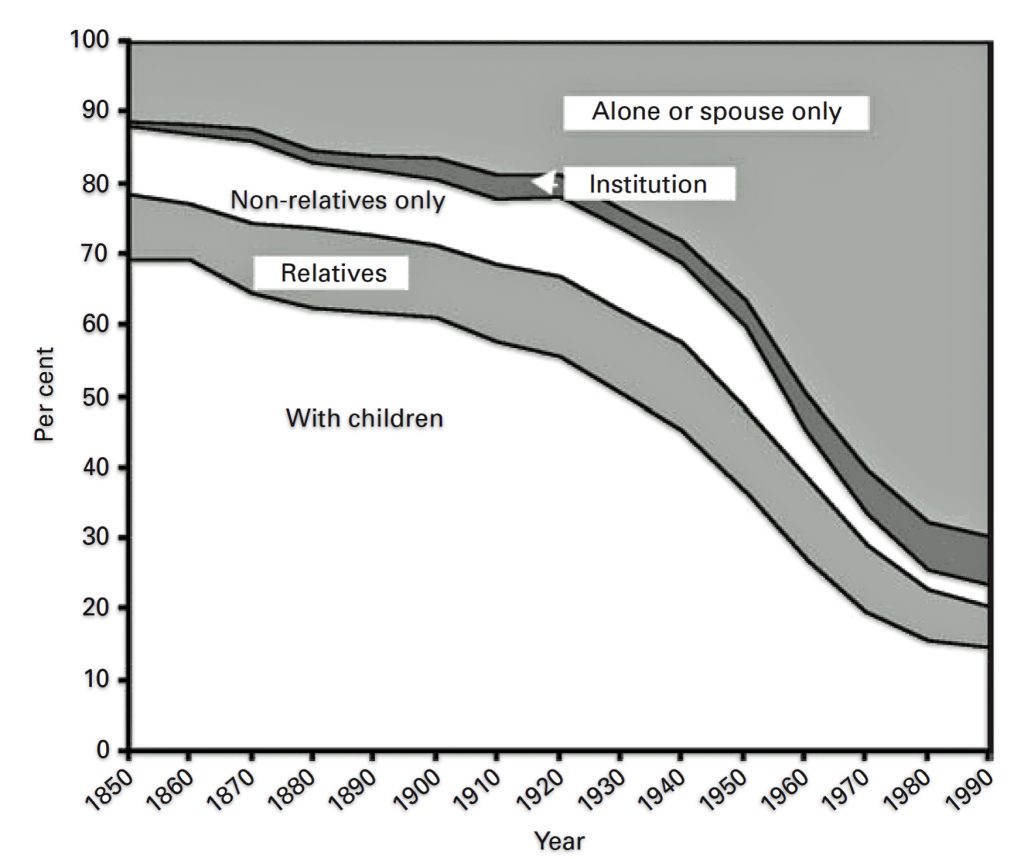

Distribution of living arrangements of white individuals and couples aged 65

or older, United States, 1850–1990

or older, United States, 1850–1990 in Multigenerational Families in Nineteenth-Century America. Continuity and Change. 18. Pages 139 – 165. 10.1017/S0268416003004466 https://users.pop.umn.edu/~ruggl001/multigenerational.pdf

Multigenerational Families in the Mid-Nineteenth Century America

For most of American history, multi – generational living has been the norm, not the exception. This is especially true in rural areas where the economy of a farm household relied on support of two or three generations of family members. This is also true for areas in the mid-nineteenth century that witnessed population growth in urbanized areas.

A multi – generational household is characterized by adults from two or more generations, and potentially their minor children or grandchildren, all living together under one roof. The specific composition can vary but it goes beyond the “nuclear family” of just parents and minor children living together. [21]

In the United States overall, multi – generational living arrangements were very common in the 1850s through the turn of the century. Around seventy percent of elderly Americans aged 65 and over lived with their adult children or children-in-law in 1850. Only about eleven percent of the elderly lived alone or with just a spouse at that time. [22]

As reflected by the Sperber and Fliegel households in various Federal and state census , German immigrants were more likely than some other groups to live in nuclear family arrangements, at least when first arriving, while still maintaining connections to extended family. But overall, multi – generational households were still the norm for most Americans in the 1850s. The Germans’ greater propensity for independent living likely stemmed from factors like their occupational skills, cultural values, and the staggered migration of families. [23]

Multi – generational families were almost universal among the aged population of the mid-nineteenth century. Moreover, under the pre- industrial economic system, multi – generational living arrangements offered social and economic benefits to both the older and the younger generation. The great majority of families went through a multi – generational phase if the parents lived long enough. According to this interpretation, the multi generational family was a normal stage of the pre-industrial family cycle. Families were typically multigenerational only for a brief period after the younger generation reached adulthood and before the older generation died. [24]

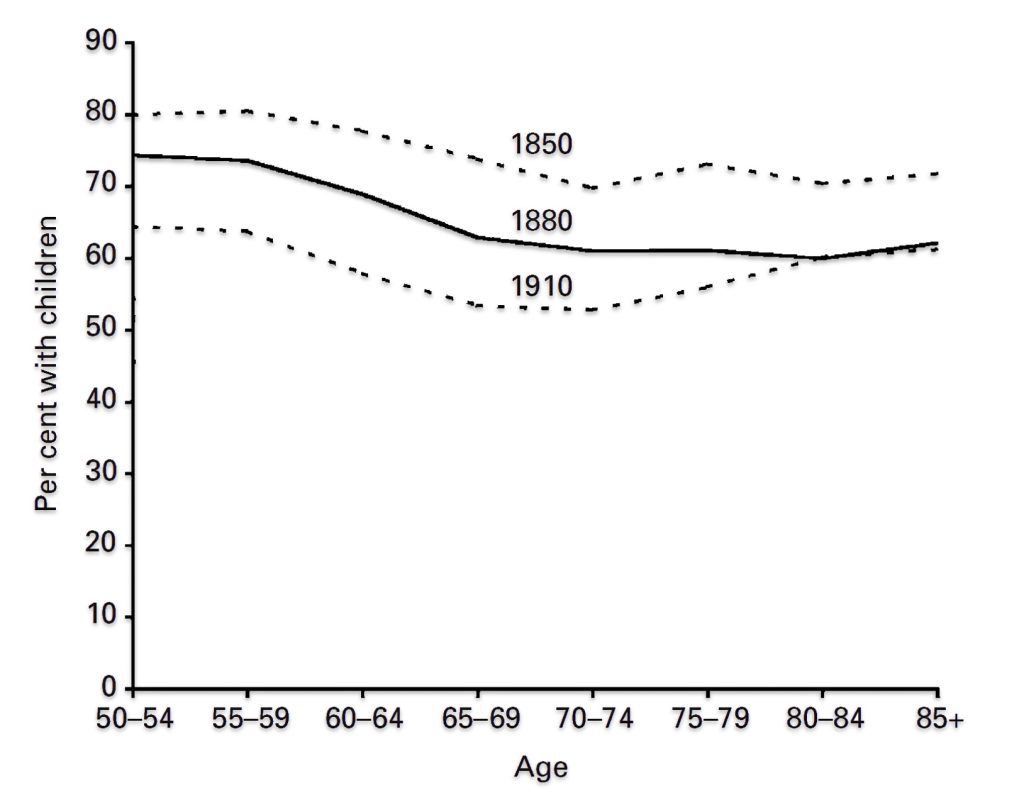

As reflected in the graph below, between 1850 and 1910 there was no substantial increase in co-residence with increasing age of persons residing with one of their children. The average percentage of individuals living with their children declined. This finding is consistent with the interpretation that the elderly did not typically move in with their children for support – instead the children never moved out.

Percentages of White Persons Residing with One of Their Own Children by Age

Source: Figure 10. Percentages of white persons residing with one of their own children, by age, United States, 1850–1990. (Source: IPUMS.) in Ruggles, Steven. (2003) in Multigenerational Families in Nineteenth-Century America. Continuity and Change. 18. Pages 139 – 165. https://users.pop.umn.edu/~ruggl001/multigenerational.pdf

“Even though most households did not include multiple generations at any given moment, the great majority of families went through a multigenerational phase if the parents lived long enough. According to this interpretation, the multi generational family was a normal stage of the pre-industrial family cycle. Families were typically multigenerational only for a brief period after the younger generation reached adulthood and before the older generation died.” [25]

It has been suggested that the decline of the multigenerational family in the twentieth century is connected to the rise of wage labor and the diminishing importance of agricultural and occupational inheritance. [26]

“External forces shaped the way the (glove) industry grew in the decade of the 1860s. The newly invented sewing machines were improved enough to be adopted by glove-makers. The invention of dies revolutionized (glove) cutting. County manufacturers began making dies, adding to one of the many industries spawned by glove-making. The Civil War had an impact in creased demands for gloves for the infantry and calvary, but shortages of both leathers and workers limited increased production. The burgeoning industry felt the aftermath of war much more strongly than the war years. Numerous factories sprang up and the county began producing fine gloves. Marking post-war growth, a railroad finally reached the county in the last years of the decade.” [27]

East Fulton Street (from the Four Corners), Gloversville (1860)

In the 1865 New York State census for the Gloversville – Johnstown area, the value of John Sperber’s home was $400.00. This is equivalent in purchasing power to about $7,707.21 today. [28]

John is reported to be 35 years old and his wife Sophie is 32. Four of their children were living at the time: Rosa (Rose) at 9 years of age, Anna at 8, Frederick at 6 and Katie or Kathryn at 2 years of age. Other records indicate that Kate Sperber was born on January 1, 1864. The enumerator evidently rounded up Kate’s age. [29] John Sperber’s occupation is listed as a “glove maker”.

1865 New York State Census – Household of John Sperber

1868: The Sperber Family and the American Dream

Roughly 16 years after arriving in the United States, the year 1868 was a notable year for John Sperber. It was a year some would say he was realizing the American Dream. John had a growing family in a vibrant community. He had steady work in the glove making industry. 1868 was also a year that he purchased a home and became an American citizen.

The American Dream is a national ethos and set of ideals in the United States that suggests anyone, regardless of their background or circumstances of birth, can attain their own. [30]

While the phrase “American Dream” was popularized by historian James Truslow Adams in his 1931 book “The Epic of America” during the Great Depression, the ethos and ideals of what would later be called the “American Dream” can be found in various writings and movements of the nineteenth century, even if the exact phrase was not yet used. Throughout the 1800s, waves of immigrants came to America in pursuit of opportunity, upward mobility, and a better life for their families – the essence of the American Dream. This immigrant perspective shaped the understanding of the concept. [31]

Truslow described it as “that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement.”

The roots of the American Dream lie in the Declaration of Independence, which states that “all men are created equal” and have the right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The idea evolved over time, shifting from an emphasis on democracy, liberty and equality to a focus on achieving material wealth and upward mobility. While the existence and reality of this dream being real or and an illusion has been argued over time, the key aspects of this ethos is:

- Freedom and opportunity for prosperity and success;

- Upward social mobility for the family and children, achieved through hard work;

- Belief that the United States is a land of opportunity that allows people to rise above the stations of their births; and

- Owning a home and having a successful career as traditional markers of the Dream.

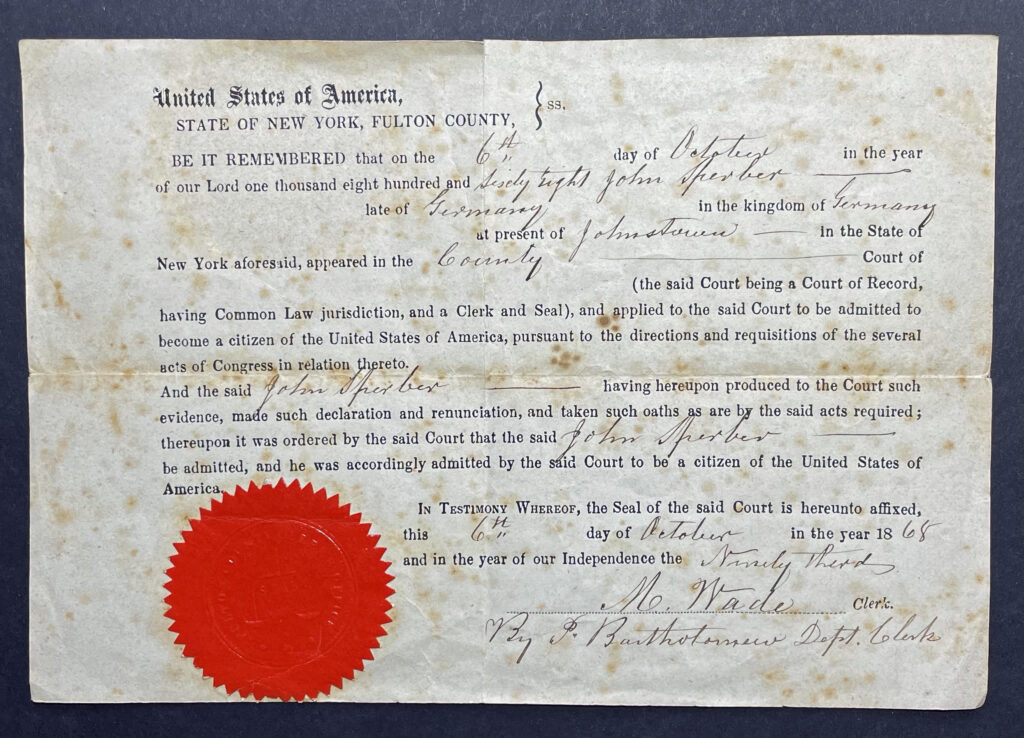

John Sperber became an American citizen in the fall on October 6, 1868, as reflected in the document of naturalization below.

Naturalization Document for John Sperber

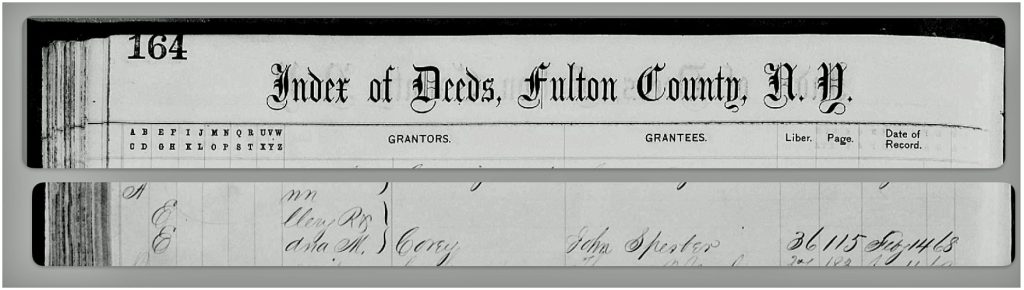

Earlier in the same year, John Sperber purchased a home in Gloversville – Johnstown, cementing his stakes in his new homeland. The following is documentation in the Fulton County Index of Deeds, reflecting the purchase of property from Ellery and Edna Cory. The Index of Deeds for Fulton county noted the transaction on February 14, 1868.

Index of Deeds 1868 – John Sperber Grantee

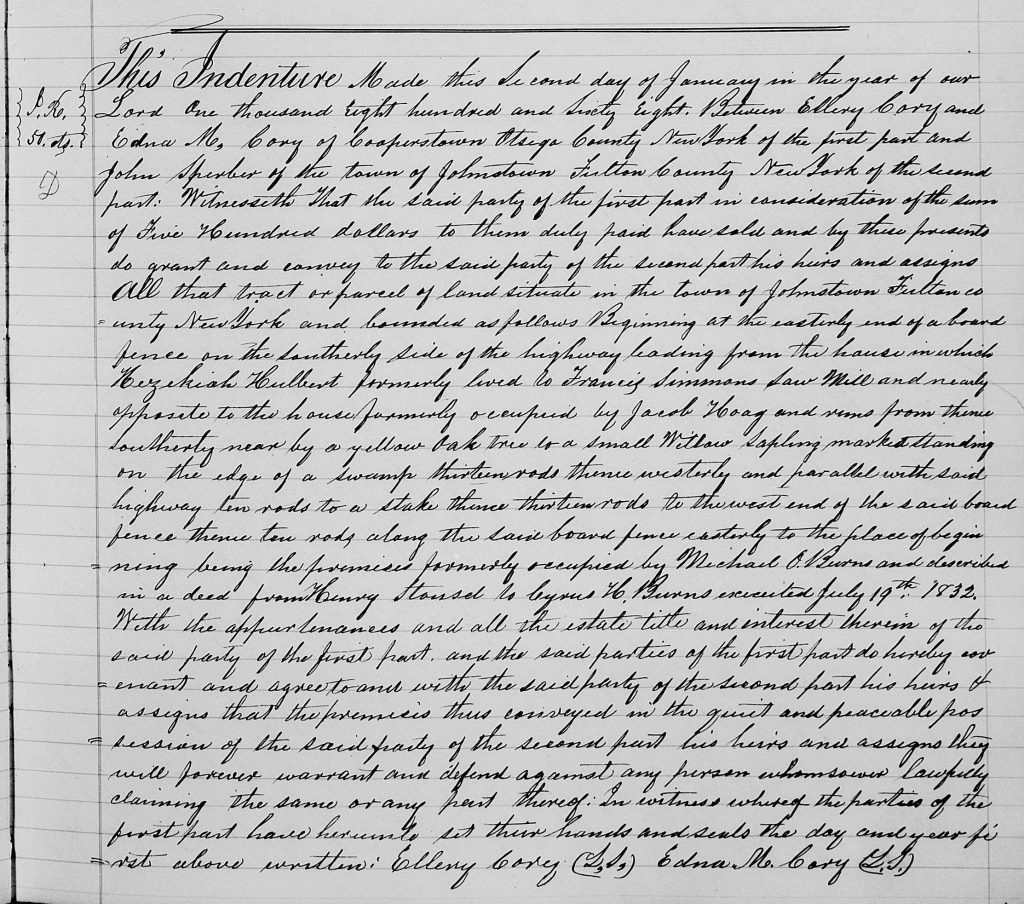

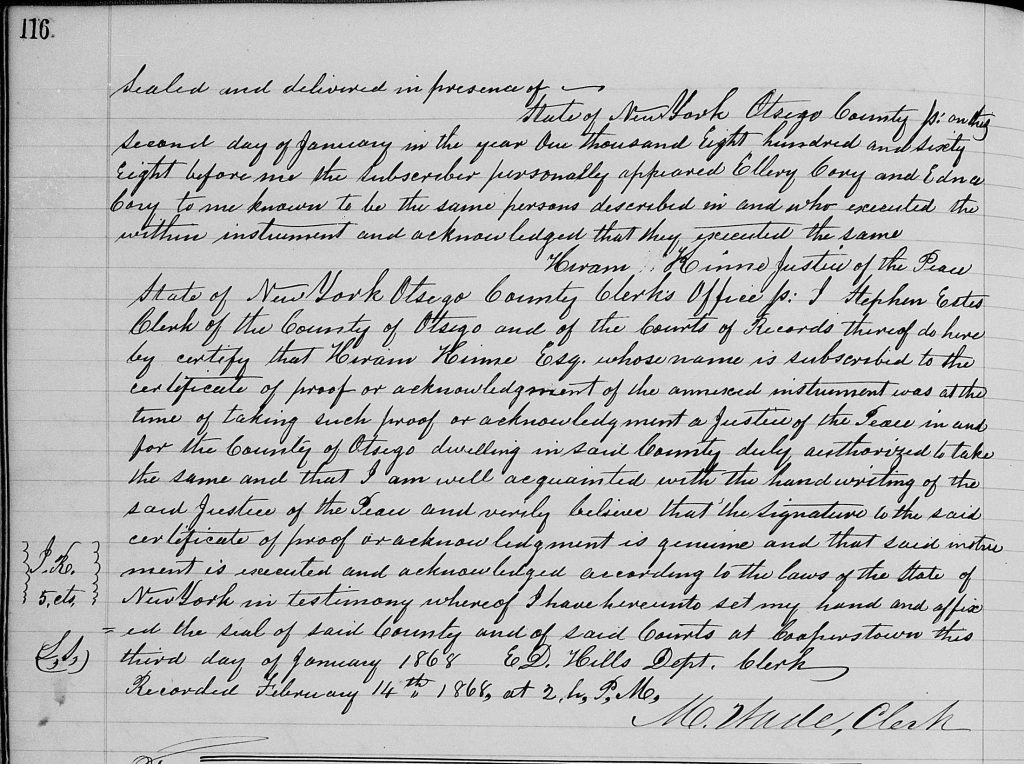

The recorded deed to the house indicates that John purchased the house from Ellery and Edna Cory, who were from Cooperstown, Otsego County, New York on January 2, 1868. John purchased the house for the sum of five hundred dollars. [32]

The description of the property indicated:

“All that tract or parcel of land situate in the town of Johnstown Fulton county and bounded as follows Beginning at the eastern end of a board fence on the Southerly side of the highway leading from the house in which Hezekiah Hulbent formerly lived to Francis Simmons Saw Mill and nearly opposite to the house formerly occupied by Jack Hoag and runs from thence Southerly near by a Yellow oak tree to a small Willow Sapling marked standing on the edge of a swamp thirteen rods thence westerly and parallel with said highway ten rods to a stake thence thirteen rods to the west end of the said board fence thence ten rods along the said board fence easterly to the place of beginning being the premises formerly occupied by Michael O. Burns and described in a deed from Henry Stassel to Ivers H Burns executed July 19th 1832.”

The Deed to John Sperber’s House 1868

Page One of the Deed

Source John Sperber, Grantee, Ellery R. Corey, Grantor, 14 Feb 1868, Entry Number 36, Page Number 115

Page Two of the Deed

Source: John Sperber, Grantee, Ellery R. Corey, Grantor, 14 Feb 1868, Entry Number 36, Page Number 116

To be honest, I would have a difficult time finding this piece of property based on the ‘legal’ description of the deed. I imagine the board fence described in the deed above is gone and the cast of property owners mentioned had already left the area.

Perhaps the Simmons saw mill referenced in the deed would provide historical and geographical context to locate John and Sophie’s home.. The saw mill referenced in the deed was one of many enterprises originally created by Francis Simmons.

“Andrew Dye (Simmons), eldest child of Francis and Elizabeth (Dye) Simmons, … grew up on the home farm and engaged with his father in farming and milling operations. Upon his succession to the property and business, he converted the old mill into a modern one, and engaged extensively in lumbering and manufactured lumber. His mill was equipped with modern woodworking machinery, and supplied his section with sashes, blinds, doors, etc., used in the erection of private and public buildings.” [33]

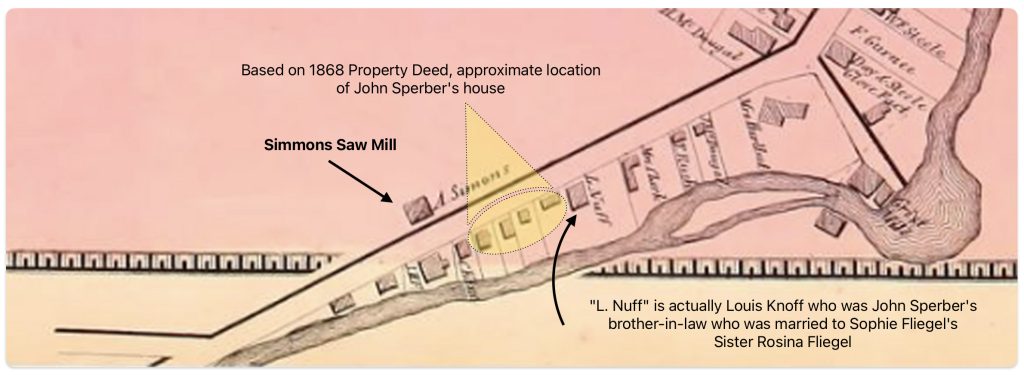

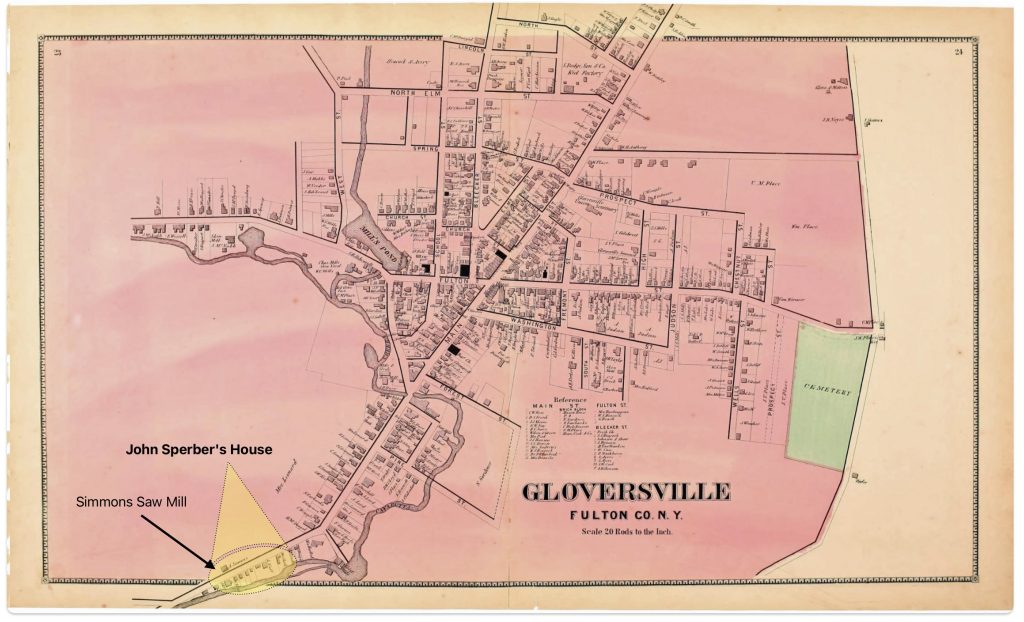

The Simmons saw mill was southwest of John Sperber’s property, as reflected in the portion of an 1868 map of Gloversville below.

John Sperber’s House in Relation to Simmons Saw Mill [34]

An interesting fact that is reflected in the above map. While the map is obviously not to scale, there is a property identified as “L. Nuff” which was close to John and Sophies’ property. The map of Gloversville on page 23 in the 1868 atlas of Montgomery and Fulton counties actually refers to the property of Louis Knoff. “Knuff” appears to be a phonetic pronunciation of Knoff. Louis Knoff was John Sperber’s brother-in-law who was married to Sophie’s sister Rosina (Rose) Fliegel.

Louis Knoff learned his trade in the leather tanning trade in Breslau, Prussia. He apparently came directly to Gloversville to apply his trade. He started working in tanning shops in Johnstown. He eventually started his own business in Gloversville in 1861 which flourished and then built a factory and tannery in 1865 on South Main Street. Knoff was a widower with a son, Herman, when he remarried Rosa Fliegel in 1866. [35]

The general context of where John Sperber’s new house was in the village of Gloversville in 1868 can be viewed in the map below. John’s new home was on South Main street, “on the Southerly side of the highway”, as stated in the deed, on the lower end of the village along the Cayadutta Creek. His home was on the southern outskirts of town along the Cayadutta Creek.

John Sperber’s House in Context of the the Village of Gloversville [36]

“Almost every city and village is situated on a stream or body of water which has been the determining factor in its location. Johnstown and Gloversville has such a stream, the Cayadutta creek. It is a small stream but it has had a great influence on Fulton county history.” [37]

The name “Cayadutta” comes from the Iroquois language and means “rippling waters” or “shallow water running over stones”. By the time that John Sperber lived by the creek, its original name did not reflect the actual conditions of the creek. The creek provided water power that enabled the early leather tanning and glove making industries to develop in Gloversville in the early nineteenth century.

One hundred years later from the time Johann Sperber lived near Cayadutta creek, leather tanning processes did not significantly change and the effects it had on the creek which runs through Gloversville and Johnstown. The creek ran rainbow colors from the materials and chemicals being dumped into it by tanneries.

“There were about a dozen really big tanneries. And the creek ran different colors. Sometimes it was blue, and sometimes it was yellow and Sulphur-stenching, and sometimes it was a burgundy red color, but mostly it was just sort of a gray brown sludge. … The blue is chromium – that’s the tanning solution – and so the hides would come out bright blue. And then when they were done with tanning those hides, they would just dump that right in the creek, and the creek would run blue.” [38]

There were multiple tanneries and leather manufacturing operations, some quite large in scale, located along the Cayadutta Creek in Gloversville during the early-to-mid 1800s as the area became a major center for leather and glove production. The creek provided the necessary water power for operating the mills. By the 1860s, Gloversville was a growing village with about 500 houses and nearly 3,000 people. Leather tanning and glove making, centered along the Cayadutta Creek, were the dominant industries. [39]

The 1868 purchase of property was the first of five documented land indentures that I have discovered in the Fulton county land records that involved the Sperber family (see table below). First four involve John and Sophia and the fifth is associated with their son J. Frederick Sperber. Ella J. Sperber was Frederick’s wife.

New York Land Records of the Sperber Family

| Date | Grantor | Grantee | Fulton County Deeds |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 Feb 1868 | Ellery Corey & Wife | John Sperber | Vol 36 Page 115-116 |

| 08 Feb 1871 | John & Sophia Sperber | Michael Kennedy | Vol 39 Page 412 |

| 25 Feb 1874 | John & Sopia Sperber | G & KSRR Co. | Vol 45 Page 478 |

| 28 Jun 1882 | A. D. Simmons & Wife | Sophia Sperber | Vol 59 Page 548 |

| 28 Nov 1886 | A. D. Simmons & Wife | Ella J Sperber | Vol 68 Page 287 |

The next section of this story discusses the above mentioned land deeds associated with the Sperber family in the 1870s and 1880s as well as the family’s life into the twentieth century.

Sources

Feature Photograph: This is an amalgam of a cut out of an 1868 map of Gloversville in the center. Highlighted in yellow is the approximate location of John and Sophia’s house that they purchased in 1868. In the upper left hand corner is a cut out is John Sperber’s Marriage certificate to Sophia Fliegel. Below the marriage certificate is a portion of the Land Indenture that was the legal document for the sale of their new home. John’s naturalization paper, signifying his becoming an American citizen, is on the right hand portion of the banner..

[1] Gloversville was incorporated as a village in 1853 and as a city in 1890. In the state of New York, Villages are municipal corporations voluntarily formed by residents within one or more towns to provide additional services. A village remains part of the town(s) it is located in, and village residents are still residents and taxpayers of the town(s). In contrast, towns encompass all territory in the state outside of cities and Indian reservations. Villages have their own local governments separate from the town(s) they are located in. Towns are direct subdivisions of counties and have their own town governments.

Village Government, New York Local Government Handbook, https://video.dos.ny.gov/lg/handbook/html/village_government.html

Town Government, New York State Handbook, https://video.dos.ny.gov/lg/handbook/html/town_government.html

Gloversville, NY, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gloversville,_New_York

Johnstow, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johnstown,_New_York

Administrative divisions of New York (state), Wiipedia, This page was last edited on 2 June 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Administrative_divisions_of_New_York_(state)

[2] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City 1845-80, (Urbana:University of Illinois Press, 1990), Page 48, https://archive.org/details/littlegermanyeth0000nade

[3] Endogamy, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 4 January 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endogamy

[4] See for example:

Xu, Dafeng, Ethnic Endogamy after Settling Down for Several Generations: Evidence from the 1930 U.S. Census, The Conference Exchangehttps://paa.confex.com › mediafile › Paper18830

Angrist, Josh, Consequences of Imbalanced Sex Ratios: Evidence from America’s Second Generation, Working Paper 8042, Dec 2000, National Bureau of Economic Research, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w8042/w8042.pdf

Jimenez, Tomas R., Immigrants in the United States: How Well Are They Integrating into Society?, May 2011, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, Migration Policy Institute, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/integration-Jimenez.pdf

Martin D, David Hacker J, Francesco S. Becoming American: Intermarriage during the Great Migration to the United States. Journal of Interdisciplinary History 2018 Fall; 49(2):189-218. doi: 10.1162/jinh_a_01266. Epub 2018 Aug 31. PMID: 31527926; PMCID: PMC6746435. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6746435/

Logan, John R. and Hyoung-jin Shin, Immigrant Incorporation in American Cities: The Case of German and Irish Intermarriage in 1880, https://paa2009.populationassociation.org/papers/91494

Logan John R. and Weiwei Zhang,White Ethnic Residential Segregation in Historical Perspective: U.S. Cities in 1880, https://paa2010.populationassociation.org/papers/101466

[5] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City 1845-80, (Urbana:University of Illinois Press, 1990), Page 48 – 61, https://archive.org/details/littlegermanyeth0000nade

[6] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City 1845-80, (Urbana:University of Illinois Press, 1990), Page 50, https://archive.org/details/littlegermanyeth0000nade

[7] Martin, Dribe, J. David Hacker, Scalone Francesco, Becoming American: Intermarriage during the Great Migration to the United States, Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 2018 ; 49(2): 189–218. doi:10.1162/jinh_a_01266 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6746435/

[8] A Sophie Witzel was found in the 1865 New York State census. She was 23 years old and was a servant in a household.

Sophie Witzel Documented in 1865 New York Census in Gloversville

The preceding census page lists the house of Philip Fliegel:

Philip Fliegel Household in the 1865 New York Census

[9] 1855 New York Census, Erie County, Grand Island, page 18 Line 10.

[10] “All three of the officially sanctioned German churches were represented among the migrants. Reformed parishioners were most numerous, making up 39 percent of the group. Lutherans made up 31 percent, and Catholics 29 percent. The remaining 1 percent were Baptists or Mennonites.”

Otterness, Philip, Becoming German: The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004, Page 21

[11] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City 1845-80, (Urbana:University of Illinois Press, 1990), Page 91, https://archive.org/details/littlegermanyeth0000nade

See also Menear, Peggy and Jeanette Shiel , History of Gloversville, Copied from from The Gloversville Daily Leader, of the Date of Saturday, October 28, 1899, 13 May 2008, Fulton County NYGenWeb, https://fulton.nygenweb.net/history/glovshistory.html

[12] Frothingham, Washington, History of Fulton County, Syracuse: D. Mason & Co. 1892, Pages 262 – 263 https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_of_Fulton_County/3QNIAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

[13] The Gloversville Daily Leader, Saturday, October 28, 1899, Gloversville New York, page 15;

[14] Table XVII – (A) and (B) Statistics of the Churches in the United States at the Censuses of 1870, 1860, and 1850, Pages 500 – 526, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1870/population/1870a-48.pdf

[15] New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island, 1820-1957, The National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, D.C.; Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010; January 26, 1855 arrival, Ship: Zurich, Lines 3-7.

[16] See for example:

Lee, W. R. “Bastardy and the Socioeconomic Structure of South Germany.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 7, no. 3, 1977, pp. 403–25. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/202573. Accessed 3 July 2023.

Shorter, Edward. “Illegitimacy, Sexual Revolution, and Social Change in Modern Europe.”The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 2, no. 2, 1971, pp. 237–72. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/202844. Accessed 4 July 2023.

Shorter, Edward. “Female Emancipation, Birth Control, and Fertility in European History.”The American Historical Review, vol. 78, no. 3, 1973, pp. 605–40. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1847657. Accessed 4 July 2023.

[17] Shorter, Edward, et al. “The Decline of Non-Marital Fertility in Europe, 1880-1940.” Population Studies, vol. 25, no. 3, 1971, pp. 375–93. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2173074 .

[18] The Gloversville Daily Leader, Saturday, October 28, 1899, Gloversville New York, pages pages 12 – and 13;

See also Menear, Peggy and Jeanette Shiel , History of Gloversville, Copied from from The Gloversville Daily Leader, of the Date of Saturday, October 28, 1899, 13 May 2008, Fulton County NYGenWeb, https://fulton.nygenweb.net/history/glovshistory.html

[19] Gloversville, New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gloversville,_New_York

The Gloversville Daily Leader, Oct 28, 1899, Page 12 https://fulton.nygenweb.net/history/glovshistory.html

[20] Morrison, James, City Historian, City of Gloversville, https://cityofgloversville.com/residents/city-historian/

[21] The U.S. Census Bureau defines a multigenerational household as including three or more generations, such as grandparents, parents, and children. Pew Research Center defines multigenerational households as including two or more adult generations (with adults mainly ages 25 or older) or a “skipped generation” consisting of grandparents and grandchildren younger than 25.

Ruggles, Steven, Reconsidering the Northwest European Family System: Living Arrangements of the Aged in Comparative Historical Perspective, Volume 35, Issue 2, 12 June 200, Pages 249 – 273, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2009.00275.x

[22] Ruggles, Steven, Multigenerational Families in Nineteenth-Century America. Continuity and Change. 18. 2003 ,Pages 139 – 165. 10.1017/S0268416003004466 https://users.pop.umn.edu/~ruggl001/multigenerational.pdf

[23] Liu, Philip, German Immigrant Family Structures, 13 May 2009, People of New York City, https://eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/seminars/drabik09/articles/g/e/r/German_Immigrant_Family_Structures_c5bf.html#cite_note-1

Nadel, Stanley . Little Germany: ethnicity, religion, and class in New York City, 1845-80. Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1990

[24] Ruggles, Steven, Multigenerational Families in Nineteenth-Century America. Continuity and Change. 18. 2003 ,Pages 142. 10.1017/S0268416003004466 https://users.pop.umn.edu/~ruggl001/multigenerational.pdf

[25] Ruggles, Steven, Multigenerational Families in Nineteenth-Century America. Continuity and Change. 18. 2003 ,Pages 153. 10.1017/S0268416003004466 https://users.pop.umn.edu/~ruggl001/multigenerational.pdf

[26] Ruggles, Steven, Multigenerational Families in Nineteenth-Century America. Continuity and Change. 18. 2003 ,Pages 139 – 165. 10.1017/S0268416003004466 https://users.pop.umn.edu/~ruggl001/multigenerational.pdf

[27] Barbara McMartin, The Glove Cities: How A People and Their Craft Built Two Cities, NY: Lake View Press, 1999, Page 24

[28] Value of $400 from 1865 to 2024, CPI Inflation calculator, https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1865?amount=400

[29] Kathryn Sperber, Born 1 Jan 1 1864, Died 17 May 1941; Age 77, funeral was 20 May 1941 in Gloversville, cause of death: carcinoma of cecum, Undertaker: Walrath & Bushouer.

Prospect Hill Cemetery Gloversville, Fulton County, New York, USA, Section 8, Memorial ID: 114576667 https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/114576667/catherine-sperber

Social Security Index / Application lists her birthday as 1 Jan 1864, U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007

[30] Adams, James Truslow, The Epic of America, Boston: Little, Brown & Co, 1931, https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.262385/page/n1/mode/2uphttps://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.262385

American Dream Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 3 June 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Dream

Investomedia Team, Reviewed by Somer Anderson, Fact checked by Suzanne Kvilhaug, What is the American Dream? Examples and How to Measure It, July 2, 2024, Investpedia, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/american-dream.asp

“The American dream.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, 22 Jun 2024, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/the%20American%20dream .

Gibson, Kate, Pew finds nation divided on whether the American Dream is still possible, July 2, 2024, Moneywatch, CBS News, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/american-dream-is-still-possible-pew/

Defining the Dream: The American Dream, Penn State Behrend,

Maciag, Drew, The American Dream: Is That All There Is? Is That All There Was?, Jan 30, 2024, Society for U.S. Intellectual History, Blog, https://s-usih.org/2024/01/the-american-dream-is-that-all-there-is-is-that-all-there-was/

Leonhardt, David, The American Dream, Quantified at Last, Dec 8 2016, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/08/opinion/the-american-dream-quantified-at-last.html

Anonymous, Review: The Epic of America by James Truslow Adams, World Affairs, Vol. 95, No. 2 (September, 1932) , p. 131, Published by: World Affairs Institute

Wills, Mathew, James Truslow Adams: Dreaming up the American Dream, May 18, 2015, JSTOR Daily, https://daily.jstor.org/james-truslow-adams-dreaming-american-dream/

[31] The ethos and ideals of what would later be called the “American Dream” can be found in various writings and movements of the 19th century, even if the exact phrase was not yet used:

- The concept of “rugged individualism” emerged as Americans pushed westward to explore and settle the frontier. This independent spirit was a key aspect of the American Dream.

- The Transcendentalist movement in the mid-1800s, led by writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, emphasized self-reliance, non-conformity, and the importance of the individual. These ideas align with the American Dream of forging one’s own path.

The American Dream In The Nineteenth Century, “The American Dream in the Nineteenth Century .” Literary Themes for Students: The American Dream. Encyclopedia.com. 14 Jun. 2024 https://www.encyclopedia.com/education/educational-magazines/american-dream-nineteenth-century

Transcendentalism, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 14 June 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism, Sep 12, 2023, Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/transcendentalism/

Brodrick, Michael, American Transcendentalism, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy,

“The American Dream in the Nineteenth Century .” Literary Themes for Students: The American Dream. . Encyclopedia.com. (June 14, 2024). https://www.encyclopedia.com/education/educational-magazines/american-dream-nineteenth-century

Chandan A., American Creed, Writing Our Future, National Writing Project, https://writingourfuture.nwp.org/americancreed/responses/1270-the-immigrant-dream

[32] John Sperber, Grantee, Ellery R. Corey, Grantor, 14 Feb 1868, Entry Number 36, Page Number 115, “United States, New York Land Records, 1630-1975”, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:62ST-8C2T : Sun Mar 10 17:41:25 UTC 2024), Entry for Ellery R Corey and John Sperber, 14 Feb 1868.

John Sperber, New York Land Records, 1630 – 1975, Fulton County, Deeds 1867 – 1869 vol 35 -36, images 433 and 434, “United States, New York Land Records, 1630-1975,” database with images, FamilySearch, Fulton > Deeds 1867-1869 vol 35-36 > image 434 of 677; Fulton County, New York

[33] Greene, Nelson, Chapter 103: Mohawk Manufacturing Statistics, History of the Mohawk Valley: Gateway to the West 1614 – 1925, Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1925, Volume 3, Pages 1263-1264 https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/qOApAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj93vfQneOGAxWp8MkDHQfDDNEQ7_IDegQIDxAF

[34] The enhanced version of this map was originally from Atlas of Montgomery and Fulton counties, New York : from actual surveys, New York: Stranahan & Nichols, 1868, National Archive, https://archive.org/details/atlasofmontgomer00nich/page/n53/mode/2up

However, the enhanced map is different from the map in the original referenced Stranahan & Nichols. The enhanced map contains a directory list of firms on the map.

[35] Louis Knoff Obituary, The Gloversville Daily Leader, 8 April 1893, Page 8

[36] This map was originally from Atlas of Montgomery and Fulton counties, New York : from actual surveys, New York: Stranahan & Nichols, 1868, National Archive, https://archive.org/details/atlasofmontgomer00nich/page/n53/mode/2up

[37] Palmer, R.M., Fulton County Historian, Without Cayadutta Creek Gloversville Would Now Be Section of Kingsborough, 1949 https://fulton.nygenweb.net/history/glovcayadutta.html

[38] Amy Feiereisel, North Country at Work: Tanning and Glove-Making in Johnstown and Gloversville, North Country Public Radio, Nov 28, 2018, https://www.northcountrypublicradio.org/news/story/37491/20181128/north-country-at-work-tanning-and-glove-making-in-johnstown-and-gloversville

[39] Cayadutta Creek, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 18 August 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cayadutta_Creek

Morrison, James, City Historian, City of Gloversville, https://cityofgloversville.com/residents/city-historian/

Greene, Nelson, Chapter 103: Mohawk Manufacturing Statistics, History of the Mohawk Valley: Gateway to the West 1614 – 1925, Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1925

Volume 2: Chapter 120, The City of Gloversville, Pages 1656 – 1670 https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_of_the_Mohawk_Valley_Gateway_to_/aOApAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj93vfQneOGAxWp8MkDHQfDDNEQiqUDegQIDhAG