For about hundred years, between 1853 and 1954, there were four generations of one of our family branches in America: the Sperber Family. Then there were no more Sperbers.

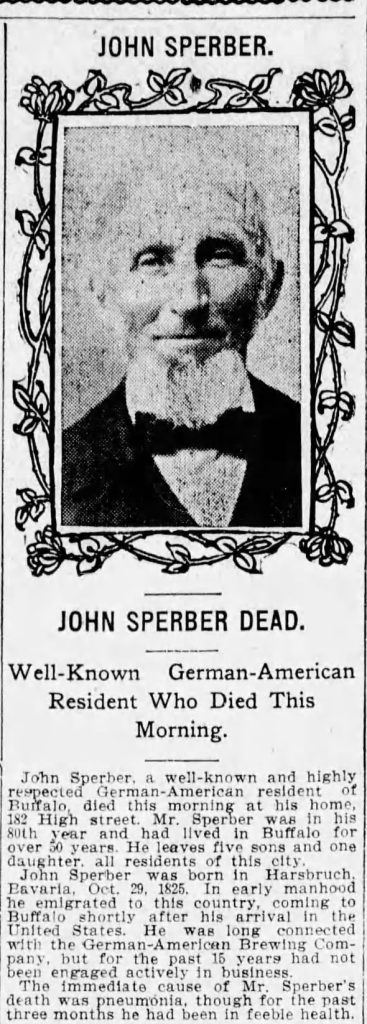

This story is about the man, Johann Wolfgang Sperber, who established this family in America in the mid 1800s. Johann or John Sperber was common man. There are no landmarks named after him. You cannot find any reference to him in a newspaper. We have relatively little documentation about Johann or John Sperber.

Johann left his homeland, traveling from the Rhine Valley to a port on the English Channel. He then endured the journey across the Atlantic in a packet ship. He married a German lady with a child who experienced the same journey from Baden, Germany. They established their roots in the fast growing twin cities of Johnstown and Gloversville, New York. Johann became a glover and eventually worked in one of the largest glove making manufacturing firms in the county. A firm that was run by one of Teddy Roosevelt’s college roommates.

While his life story mirrors the lives of many German immigrants in the mid 1800s, it is still an unusual and unique life story of a common man. He was swept up in the wave of Germans who came to the United States in the mid 1800s. He may have planned as best as possible his journey to a new land but he undoubtably encountered life experiences he could never fully anticipate.

My further research into the other possible routes that John Sperber may have taken for his journey to his new homeland gives me more confidence that he departed from Havre, France. This story provides some of the research associated with my process of ‘confirming’ his journey.

John Wolfgang Sperber: A Five Part Story

The first part of the story provides an overview of the family legacy John Sperber established in his new homeland, an historical background on where John was from in Baden, Germany, the influences on his migration to the United States, and the historical evidence of his departure and arival to America.

The second part of John Sperber’s story describes his journey from Baden-Baden to Le Havre based on historical evidence and historical accounts.

The third part of the story assesses the three major inland pathways to European ports that John had options to consider. Since it is not absolutely certain that John sailed on the Germania from Le Havre, I have provided historical background on the relative accessibility of the three major routes John may have taken to make his voyage to the United States.

The fourth part of the story discusses the possible influences that drew Johann Sperber to Fulton County, New York.

The fifth part of the story discussed his travel to New York City and his options for travel northward to the Mohawk Valley.

The sixth part of John Sperber’s story is about his establishing a new life and family in the Johnstown and Gloversville, New York area in the 1850s and 1860s.

The seventh part of the story is about the John’s Family in the context of Gloversville’s development in the 1870s and 1880s and John’s career in the glove making industry.

The eighth part of the story is about the Sperber family in the 1890’s and the twilight of John’s life after the turn of the twentieth century

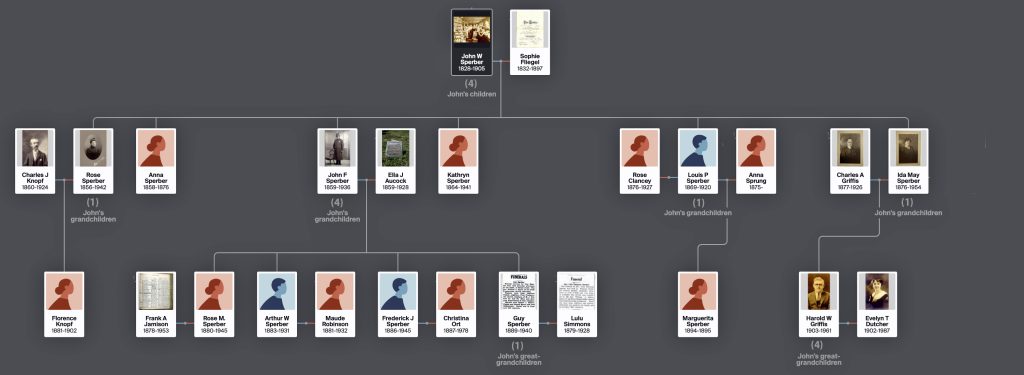

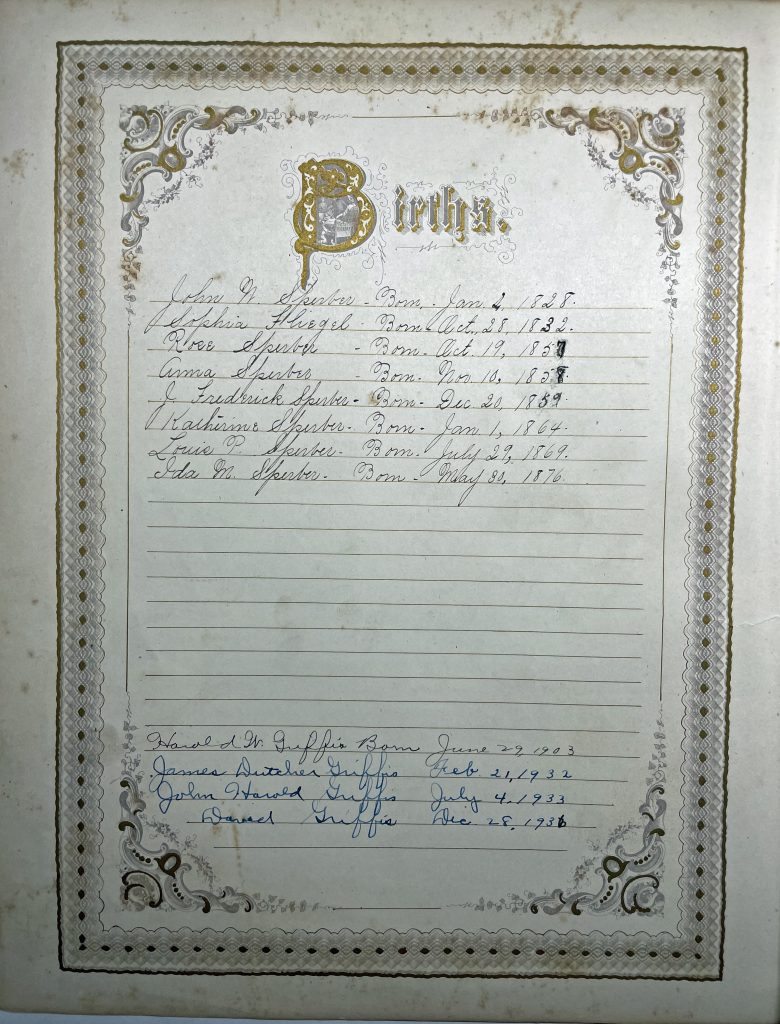

John Sperber’s Family

John Wolfgang Sperber, the Pater Familias of the Sperber family in America, is one of my great, great grandfathers. Compared with the other major family branches in the family, the Sperbers were relatively recent newcomers to America. The Speber family is part of the maternal branch of Harold Griffis‘ family. Harold’s mother was Ida Sperber.

Ida Sperber (Griffis)

Ida Sperber, (30 May 1876 – 14 Aug 1954) the youngest daughter of John Sperber and Sophia (Fliegel) Sperber. This portrait was taken around 1920 – 1925 when she was in her late 40s. Her son, Harold Griffis, was in college at the time of the photograph..

Source: Family Collection | Click for Larger View

John Sperber was part of a huge wave of German immigrants that came to the United States in the mid 1800s. Based on the review and assessment of historical sources, John immigrated to the United States around 1852 – 1853. His future sister-in-law Catherine immigrated in 1848 and his wife and the remaining in-laws migrated from Germany in 1855. As far as we know, John Sperber was the only member of his family to make the journey to America.

Family Tree of the Sperber Family

John Wolfgang Sperber and his wife, Sophia Fliegel, had six children; seven grandchildren; and five great grand children. They had two sons, John Frederick Sperber and Louis P Sperber (see the story Sperber Brothers: The Policeman in Gloversville). Louis did not have any sons. John Frederick, however, had three sons: Arthur J Sperber, Frederick John Sperber, and Guy Sperber. None of the three grandsons had any sons to carry the Sperber name forward.

John had one namesake: a great grand child through his grandson Guy Sperber. Guy’s only child was Winfield Sperber. Unfortunately Winfield was stillborn on October 18, 1916. [1] Of the remaining Sperbers, Ida Sperber was the last member of the Sperber family. Ida died in 1954.

Despite the surname not continuing through future generations, the remaining descendants of John Sperber are represented through his grandson Harold Griffis. Through Harold Griffis, he has four great grandchildren, eight great2 grandchildren, fourteen great3 grandchildren, and seven great4 grandchildren.

Surname Extinctions and Implications for Y-DNA

In 1939, a statistician named Alfred Lotka analyzed the 1920 U.S. Census and concluded that 82% of American surnames were bound to disappear. [2]

This statement sounds crazy! But there a statistical basis to anticipate the probability of a surname to go extinct. Since surnames in many Western European societies are historically associated with the surname of the male in marriage, the extinction of a family name is tied to the extinction of a Y chromosome lineages. Hence, surname extinction in Western culture and society matters to the genetic genealogist. [3]

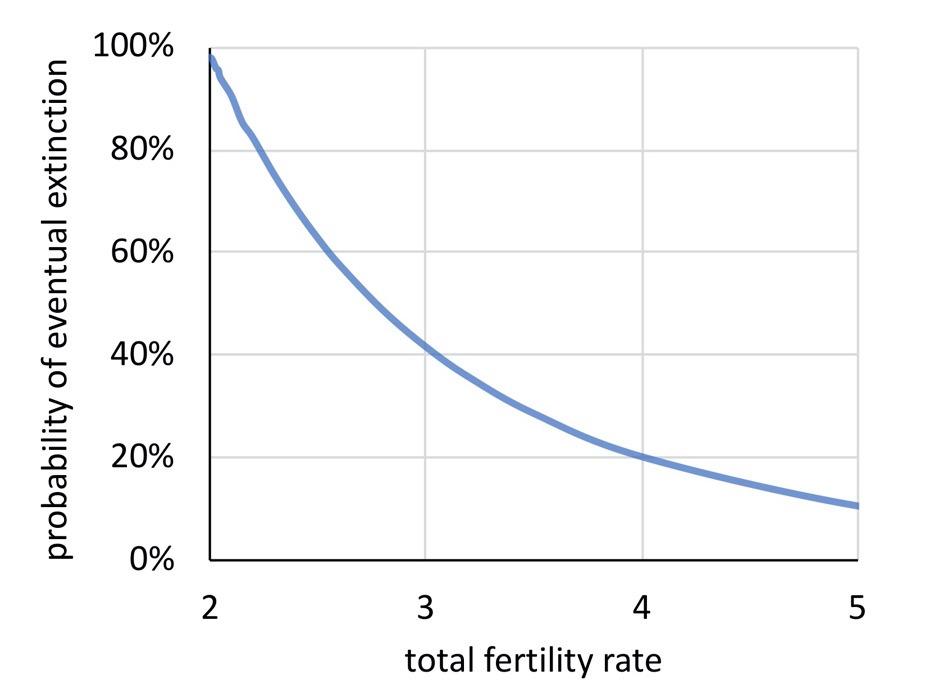

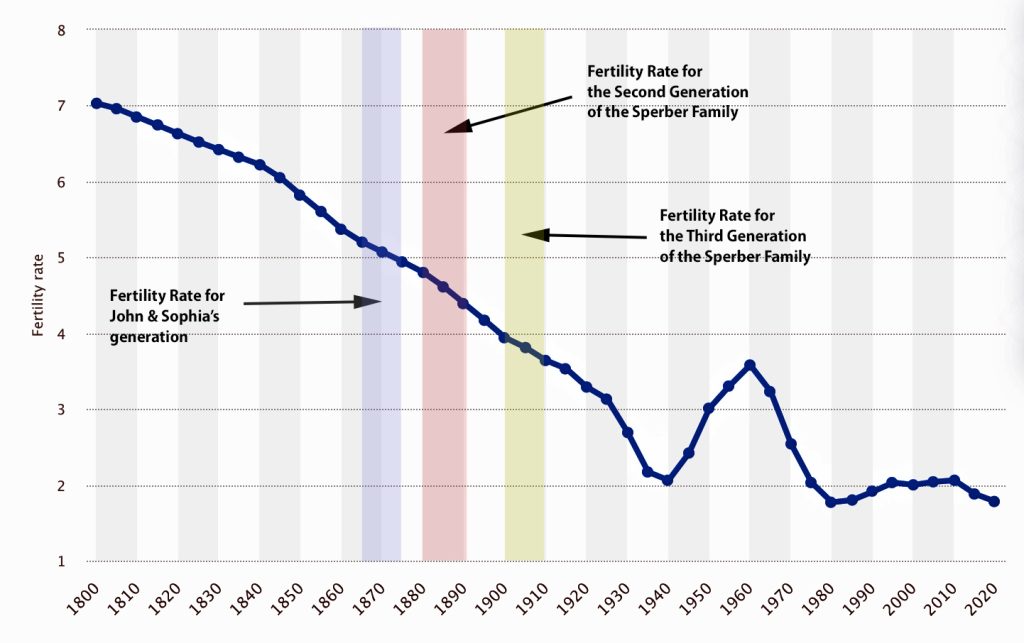

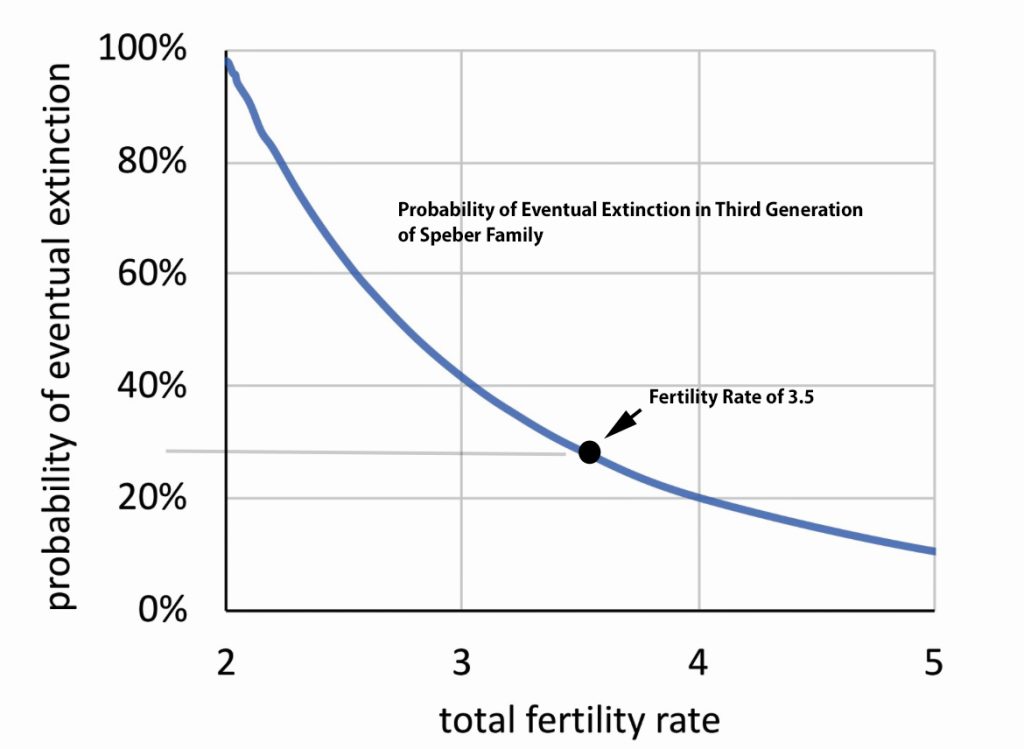

Chart One: Probability of Eventual Extinction

Based on the fertility rate at the time the third generation of Sperber’s would initially have had children (1900-1910), there was about a 30 percent chance for surname extinction.

Johann Wolfgang Sperber from the Grand Dutchy of Baden

Map One: Margraviate of Baden [4]

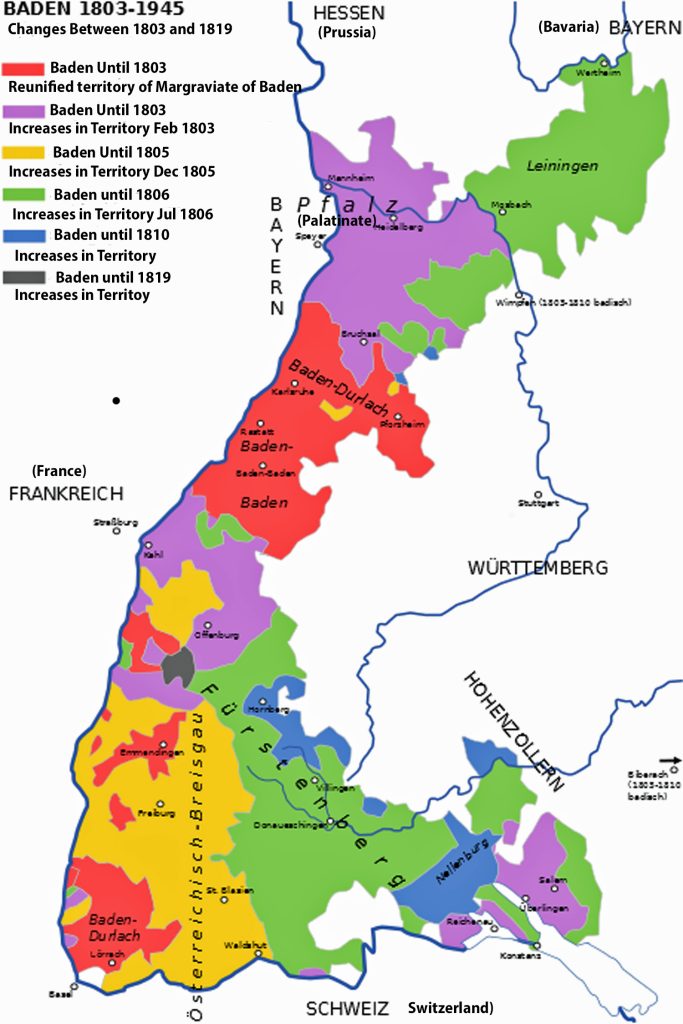

Map Two: Baden Until 1803 (Red) and Later Territorial Gains [5]

Based on census documentation, John or Johann indicated he was born in “Baden”, specifically the Baden-Baden area of the Grand Duchy of Baden. Its name and borders have changed over time, reflecting the shifting alliances and feudalist power struggles in the mid 1700s to early 1800s. The area has a rich history of cultural influences and shifting political strife and alliances since the fourth century BCA. [6]

During John Sperber’s time and during the prior generations of his father and grandfather, his birthplace was part of the Margraviate of Baden-Baden and then the Grand Duchy of Baden (Großherzogtum Baden), a state in south-west Germany on the east bank of the Rhine. The Margraviate of Baden (Markgrafschaft Baden) was, at one point, an historical territory of the Holy Roman Empire.

It was named a margraviate in 1112 and existed as such until 1535 when it was split into the two margraviates of Baden-Durlach and Baden-Baden. The two parts were reunited in 1771. The restored area became the Margraviate of Baden in 1803.

Between the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1792 and 1817 when Baden became a member of the German Confederation, Baden’s allegiance went back forth between French and German interests.

Between 1803 and 1806, it was the Electorate of Baden, receiving territorial additions. In 1806, Baden became the Grand Duchy of Baden. [7]

In earlier times Baden was considered to be on both sides of the Upper Rhine river, but after the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), it was considered as Baden only east of the Rhine. The Dutchy of Baden was bounded by Lake Constance on the south and by the Rhine river on the south and west.

Politically, the Duchy of Baden was surrounded by French and German states. To its west was the French historical region of Alsace, to its south was Switzerland, the Palatinate [8] to its northwest, Hesse or Hessen (9) to the north, and parts of Bavaria to the northeast. Its eastern border was shared with the region of Württemberg. [10]

Many fellow Germans who were born in the Grand Duchy of Baden and emigrated to the United States indicate their birthplace as ‘Baden’.

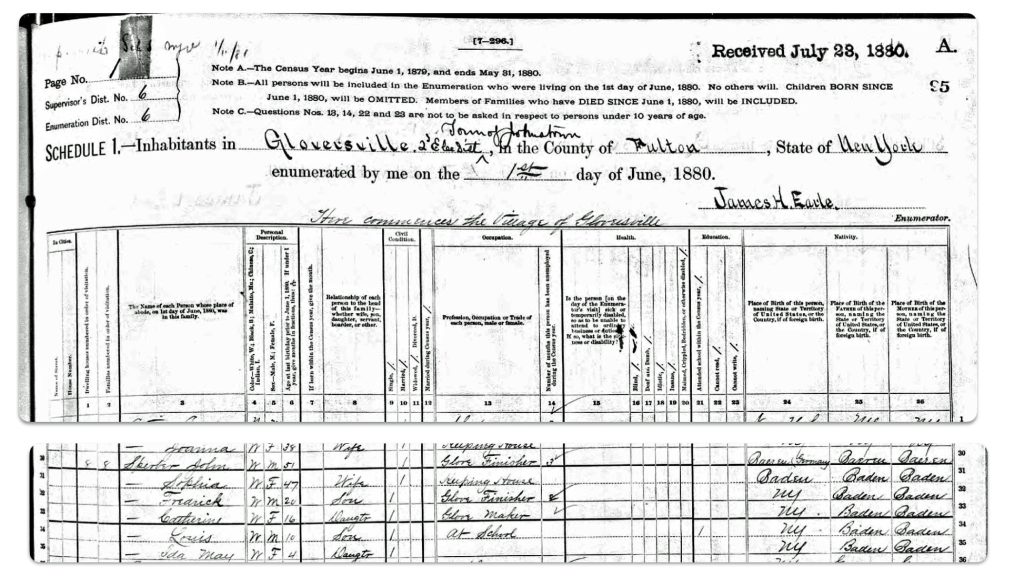

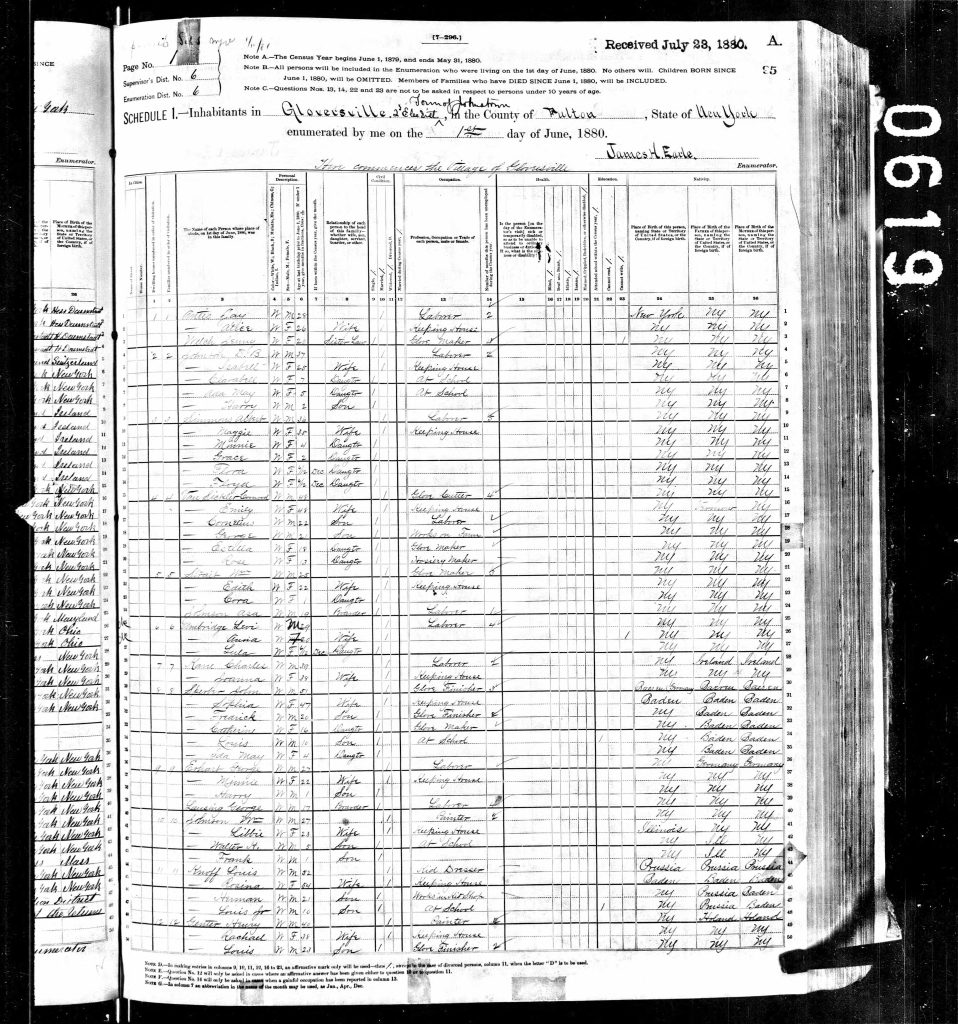

In the 1880 U.S. Census, John’s birthplace was listed as ‘Baeren’. This perhaps was due to how John answered the census enumerator’s questions or the result of what the enumerator “heard’ phonetically during the canvassing of the census. Perhaps John answered that he was a “Bauern” , a farmer in German.

Map Three: Map of the Grand Dutchy of Baden [11]

As reflected on line 30 of the U.S. Census page below, the census enumerator, James A. Earle, listed John Sperber’s birthplace as Baeren, Germany, as well as his parents. The birth place of Sophia, John’s wife, and her parents was listed as Baden. Their four of five children that were living in the household at the time were listed as having parents that were born in Baden.

1880 U.S. Census – Sperber Family

After the Napoleonic Wars Germany was a federation of thirty-nine states which varied considerably in size. It was not uncommon for enclaves of one state to be embedded in the territory of another state. There were two great powers – Prussia and Austria – and several medium-sized states, of which the most important were Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden, Hanover and Saxony. There were also numerous small territories and four Free Cities (Bremen, Frankfurt, Hamburg, and Lübeck). [12]

As reflected in map four, the mosaic map of the German states was particularly confusing in the center of the federation and in the Rhine valley. This part of the country was split up into a medley of medium-sized states (Saxony, Brunswick, Nassau, Hesse-Darmstadt, Hesse-Cassel) and tiny territories in Anhalt and Thuringia.

North of the River Main, Germany was dominated by Prussia. Prussia was divided into two groups of provinces separated by Hanover and Brunswick. The eastern and central provinces were Brandenburg, Pomerania, Posen, Silesia, East and West Prussia (united 1824-78) and the province of Saxony. The two western provinces were Westphalia and the Rhineland. South of the River Main lay Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden. Their territories were in one part except that Bavaria had an isolated province (the Palatinate), west of the Rhine River.

Map Four: The German Confederation (Der Deutsche Bund) [13]

All these states controlled their own economic and social affairs. For example, customs and excise taxes, communications, currency, banking, and artisan gilds were regulated by each state and not by the Confederation of German states.

In the context of this regional political, social and economic environment, John or Johann was reportedly born in Baden on January 2, 1828. [14] As reflected in various U.S. Federal censuses, both of his parents were from Baden area. Nothing is known about John’s family. [15]

John Sperber’s birth year varies depending on the historical source. His implied or actually stated birth year ranges from 1826 to 1838. As reflected in table one, based on available sources of information, it is highly likely that John was born on January 2, 1828. “(U)nless an age reported in the census can be corroborated with another source, it should not be considered totally reliable.” [16]

Table One: Reported Birth Year and Age of John Wolfgang Sperber by Source

| Implied Age | implied Birth Year | Source | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 26 | Implied 1826 | Germania Ship Manifest List | Manifest indicates his age as 26. This would imply he was born in 1826 |

| 35 | Implied 1830 | 1865 N.Y. State Census | Enumerator documented his age as 35. This would imply he was born in 1828 |

| 41 | Implied 1829 | 1870 Federal Census | Enumerator documented his age as 41. This would imply he was born in 1828 |

| 47 | Implied 1828 | 1875 N.Y. State Census | Enumerator documented his age as 47. This would imply he was born in 1828 |

| 51 | Implied 1829 | 1880 Federal Census | Enumerator documented his age as 51. This would imply he was born in 1829 |

| 72 | 1838 | 1900 Federal Census | Age and birth year are contradictory. Enumerator wrote his age as 72; his birth year as 1838. If he was 72, then his birth year would have been 1828. which would mean he was 62. 1900 U.S. Census. |

| 2 Jan 1828 | Family Document of Sperber Births | An handwritten page of family births for Sperber family members indicates that John Sperber was born on January 2nd, 1828. See footnote [14]. |

Why Did John Sperber Immigrate to the United States?

We do not know specifically why John Sperber immigrated to the United States. We do not know exactly why he ended up in Gloversville, New York. It appears that he immigrated alone at the young age of 24.

His individual decision and subsequent actions to immigrate to the United States were undoubtably influenced by a combination of larger social, political, economic, technical and environmental factors. He was part of a larger wave of fellow Germans from the Rhineland that migrated to the United States. Similar to his future in-laws, the Fliegel family, his decision to emigrate was undoubtably influenced by a combination of push and pull factors and enabling factors that had similar effects on many Germans. [17]

The “Push” and “Pull” Factors Affecting the German Immigration Experience are discussed in the following stories:

► The Fliegel Family: Their Journey to America October 10, 2023

► The Sperber & Fliegel Families in America: Catherine Fliegel the First to Arrive September 26, 2023

► A German Influence July 11, 2023

▶ See an example of a steerage ticket and regulations governing steerage passage from Le Havre to New York City in 1854

What motives caused John Sperber to emigrate cannot be determined by available documentation or by statistics. However, from the ebb and flow of emigration trends and patterns, it is possible to draw some conclusions about the effect of large scale political and economic trends and social conditions that existed in Baden when he came to America.

After every war in which the German states were involved there was a marked increase in emigration. The emigrant wished to avoid future wars, was economically impacted or was antagonized by post-war political conditions. Times of disorder and revolution also have been an influence. The upheavals in the 1930s and in 1848 grew out of dissatisfaction with domestic political conditions. These upheavals often owed their origin to economic and social needs and usually prepared the way for emigration. If the political hopes miscarried, as in the Germany states after 1830 and 1848, despondency and bitterness succeeded. In such a frame of mind, decisions to migrate to a land of ‘freedom and opportunity’ beyond the seas, was easily reached.

Perhaps the most important factors, however, were economic and social.

“Southwestern Germany (the Palatinate, Baden, Wurttemberg) is preeminently a region of small peasant holdings. Because of the unlimited division of the holdings and the great increase of population, the land was so subdivided that many of the small farms, even in good years, could hardly support a family. When the crops failed in successive years, as frequently happened, these petty farmers and their families suffered bitterly unless they could find other employment. Faced with the impossibility of satisfying their craving for land, for an adequate living, and for economic and social betterment, the inhabitants were ready to accept the invitations of foreign agents and emigrate en masse. If the first emigrants made a fortune “over there” or sent back favorable reports, then the more faint-hearted were ready to follow. “ [18]

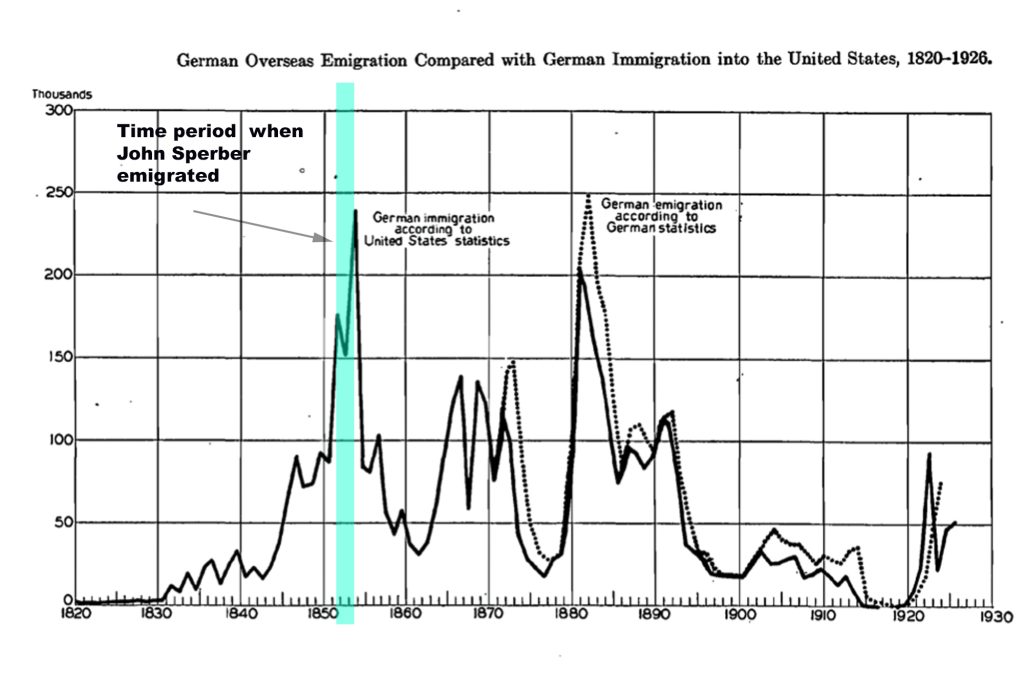

As reflected in chart one, John Sperber was one of many who were part of the first of the two major waves of German immigrants to migrate to the United States in the 1800s. German emigration reached its first crest in the southwest and western areas of the German states in the middle of the ’50’s, its second wave was represented by Germans in central Germany towards the end of the ’50’s, and its third in the east in the ’70’s and ’80’s.

Nearly one million German immigrants entered the United States in the 1850’s. The German immigrants arriving in the 1850’s represented almost 18 percent of the total number of German immigrants arriving to the United States between 1820 and 1920. In the 1850’s German immigrants represented a little over a third of all immigrants coming to the United States. [19]

Chart One: German Overseas Emigration and German Immigration to United States

Annotated chart from F. Burgdorfer, Diagram 11, Chapter XII Migration Across the Frontiers of Germany, Walter F. Wilcox, ed, International Migrations, Volume II, Interpretations, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), 1931, pages 338, https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c5114/c5114.pdf

Economic and social conditions in the Grand Duchy of Baden were particularly less favorable for the farming population as well as the artisans and mechanics in the late 1940s and the early 1850s. Self-employed farmers, artisans, and tertiary sector workers (workers providing services rather than products) from the southwest, began migrating between the 1840s and 1860s. The winter of 1851 was notably harsh due to shortages of both grain and potatoes in Germany. [20]

“(T)he credit of small farmers cracked under the strain, and the financial ruin harried them out of Germany. … In the first place, many of them are involved in mortgages from the years before 1845 when an abundance of capital and low rates of interest had encouraged extensive and often reckless improvements. In the second place, many farmers in the hard times between 1845 and 1847 had saved themselves only by piling up debts which they found impossible to shake off before greater disaster overcame them in 1851-1852. Finally, the annual payments they had assumed after 1848 in order to free themselves from feudal obligations were no less a threat because due to the government.” [21]

Similar to the plight of the Irish tenants defaulting on payment for rent during the potato blight in Ireland during the same time period, the German peasant could not meet his economic obligations. Fathers in the Rhineland could not longer provide land for their sons. The twin attitudes of despair in Europe and hope in America overcame any lingering doubts and uncertainties to immigrate to the United States.

Emigration from the German states can be regarded as a loss or a gain according to one’s the point of view. It was frequently regarded as an advantage by those who were left behind. This point of view was manifested in governmental efforts to assist the distressed population. Given the distressed nature of farming, the inability to offer functional sizes of land as inheritance, and farm debt, economic aid was given to emigrants to reduce overpopulation, ease the strain on farming, and possibly free up economic opportunities and demands for those that stayed. For example, it was noted in 1852 that the Grand Duchy of Baden developed a system of state, local and individual cooperation which assisted in the annual departure of emigrants to the United States. In the period 1840 to 1889, approximately four million marks were spent from the public funds, state and communal level, in Baden in the form of grants in aid of emigration. [22]

In addition to subsidizing emigrants to America, the Grand Duchy of Baden also sent prisoners. In 1850, fifty people were selected and financed to find a new home in America.Between 1850 and 1852, inmates were released from Pforzheim police custody and sent to America. [23]

“The natural unwillingness to leave one’s fatherland was mitigated by the fact that, in any case, old bonds of association were loosening. The common fields were being divided, and the feudal system with its joint obligations were being modernized, changes which entailed a weakening of sentimental ties as well. ” [24]

German Emigration between 1848 and 1855

This “Great Migration” experienced a rush of Europeans to the United States between 1848 and 1855, the time in which John and his in-laws, the Fliegels, immigrated to the United States. Between 1850 and 1860 around 2.6 million immigrants came into the United States and foreign born inhabitants increased from roughly 2.5 million to over 4 million. From 1850 to 1860 the rate of growth of the foreign born was nearly three times that of the native population. [25]

The German immigrants arriving in the 1850’s represented almost 18 percent of the total number of German immigrants arriving to the United States between 1820 – 1920. [26]

As indicated in the table two, during this time period, there was not much of an inward flow of population into the German federated states. Despite a healthy natural net increase of population growth (more births than deaths), the natural increases were offset by the number of Germans emigrating to other countries, notably to the United States. The net loss through emigration was especially large between 1847 and 1855, when crop failure and famine impaired living conditions among a largely agricultural population. Political discord and ferment also quickened the migratory flow out of the area. [27]

Immigrant vs Emigrant [28]

An immigrant is a person who has immigrated—“moved to another country, usually for permanent residence.” An emigrant, on the other hand, is “someone who leaves a country or region.”

The terms immigration and emigration refer to the act in relation to place, but they can also refer to a group or number of such people moving to and from places..

The difference is that emigration is leaving and immigration is coming—an emigrant is someone who moves away, while an immigrant is someone who moves in. Emigrant and immigrant can refer to the same person—people who are emigrating are also immigrating (if they leave, they have to go somewhere).

In some parts of Germany (Württemburg, Baden, and Palatinate) noted for their large emigration rates, it became so heavy that the population actually declined.

“In Baden, despite a large excess of births between 1847 and 1855, emigration caused a continuous decline in population. On the average it amounted to 0.11 per 1000 in 1846-48, 0.14 in 49-52 and 1.04 in 1853 – 55.” [29]

Table Two: Estimated Balance Between Immigration and Emigration for German States Between 1847 – 1855 (in Thousands)

| Time | Annual Increase Population | Excess Births Over Deaths | Excess Immigration (+) Emigration (-) | Total Increase (Rate per 1000) | Natural Increase (Rate per 1000) | Immigration (+) Emigration(-) (Rate per 1000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1847- 1849 | 134 | 236 | – 102 | 3.83 | 6.74 | – 2.92 |

| 1850- 1852 | 261 | 359 | – 192 | 7.35 | 10.11 | – 2.76 |

| 1853- 1855 | 64 | 222 | – 158 | 1.78 | 6.16 | – 4.38 |

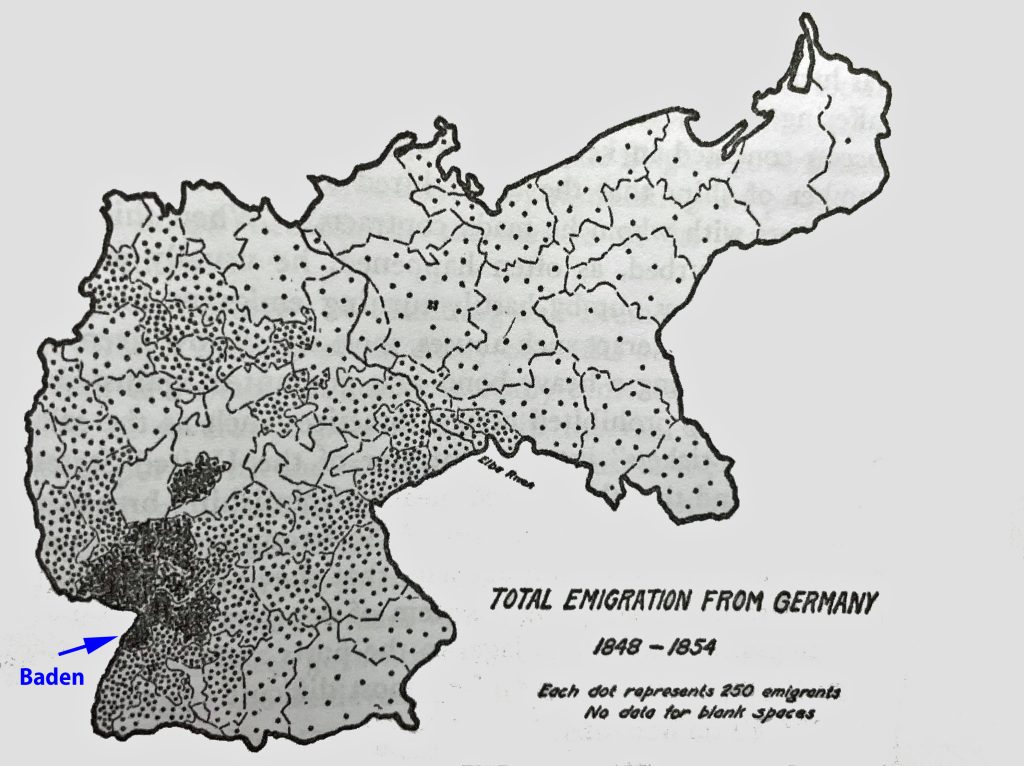

As reflected in map five below, a large proportion of the German émigrés were from the Baden area. The map provides a graphic depiction of the relative density of the location of emigrants in the German federated states between 1848 and 1854.

Map Five: Immigration from Germany 1848 – 1854 [30]

As indicated in the table three, between 1846 and 1851 German emigration from foreign ports exceeded the number of Germans leaving from German ports. It was not until 1851 that Bremen and Hamburg (and to a lesser extent Stettin, Swinemünde, Geestemünde and Lübeck) caught up with foreign ports of embarkation, notably Le Havre.

Table Three: German Emigration Through German and Foreign Ports 1846 – 1851 (in Thousands)

| Year | Total Number in Year | German Ports (Number of Emigrants) | Percent of Year | Foreign Ports (Number of Emigrants) | Percent of Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1846 | 94,581 | 38,058 | 40% | 56,523 | 60% |

| 1847 | 109,529 | 42,382 | 39% | 67,147 | 61% |

| 1848 | 81,900 | 37,532 | 46% | 44,368 | 54% |

| 1849 | 89,101 | 36,249 | 41% | 52,852 | 59% |

| 1850 | 82,404 | 37,061 | 45% | 45,343 | 55% |

| 1851 | 112,547 | 56,070 | 50% | 56,477 | 50% |

| ’46-’51 | 570,062 | 247,352 | 43% | 322,710 | 57% |

Prior to the 1850’s, the major port of embarkation for German emigrants to the United States was the French port of Le Havre; it was not until 1852 that Bremen first superseded Le Havre as the major port for the emigration of German nationals,. Even after 1852, Le Havre remained the port of choice for ethnic Germans along the southwest area of the Rhine valley.

This general pattern may suggest that John Sperber had a more equal chance of emigrating from a German or foreign port by the time 1852 or 1853 rolled around. However, each of the ports of embarkation had unique characteristics that attracted German émigrés from different areas of the confederated states.

“German emigrants left from different regions of Germany and generally favored different ports of embarkation. The Dutch ports (Antwerp and Amsterdam) declined in popularity in the 1800s because of high fares and the difficulty of finding return freights to fill the ships to make the round trips profitable. Bremen was accessible to migrants from the northwest via the Weser River. Hamburg was favorable to German emigrants from the Prussian provinces east of the Elbe River. Le Havre was more accessible to the southwest German regions (such a Baden where John Sperber resided).” [31]

Technical Advancements Related to Trans-Atlantic Commerce

While there were a number of push and pull factors that influenced the migration of Germans to the United States, technological developments associated with seamanship during the 1820-1840s facilitated the movement of cargo and people. The development of the “Admiralty Compass” and the chronometer allowed maritime navigation to be so accurate that by the 1830s ships could navigate around the earth and target their destinations within an error of a mile. [32]

In addition to the improvement of navigation instruments, competition to produce ships for efficient commercial trade produced faster, sturdier ships. “The American transadantic sailing packets were in operation from 1818 to 1881, but the era of potency was the period 1818-1858.” [33].

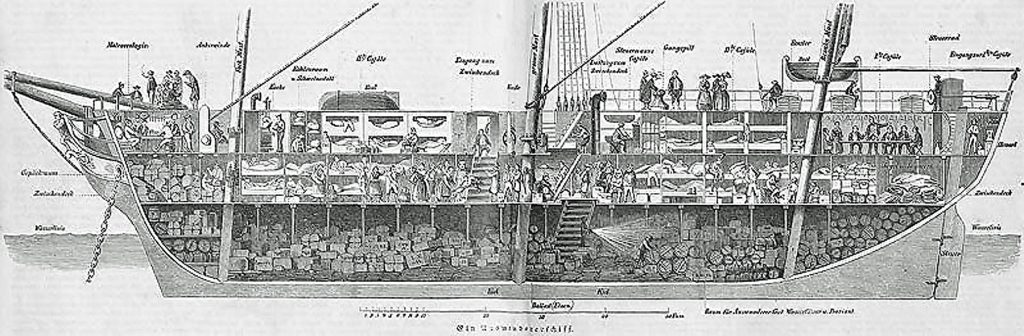

The term packet ship was used to describe a vessel that featured regularly scheduled service on a specific point-to-point line. Usually, the individual ship operated exclusively for a specific shipping line. Packet ships were sail vessels that could accommodate mail, cargo, and people. They brought raw commodities from America to Europe and on their return run, transported immigrants to America. [34]

Inside a Packet Ship 1854

“In all the history of merchant ships under sail, there was probably no sturdier group than the NewYork packets on the North .Atlantic run, nor any group better adapted to the work at hand. Their builders knew how to fashion faster vessels, but the owners did not want to sacrifice cargo space to speed. . . . Consequently, the packets were given stout hulls, tough enough to bear the strains in winter seas and roomy enough to carry profitable cargoes. Then, with potential speed deliberately reduced in construction, the owners expected the officers and men to make up the deficiency as far as possible by constant driving.” [35]

From the inception of the use of American packet ships in 1818 through about 45 years of service leading up the impact of the Civil War, the United States dominated the north transatlantic carrying trade. The packet ship was structurally suitable for the steady month after month pounding in the North Atlantic trade. The packets were used for relatively quick turn around runs. They were built with fuller models, less top hamper, and sturdier construction that did not sacrificed weight or speed. The packet “stayed with it, punching valiantly back and forth across the Western Ocean.” The packets, with well-balanced hulls and rigging plan, was driven hard hour after hour, day after day, with never a minute of letup. [36]

“Generally, during this period, a good deal of cotton moved eastward (from the United States), and with such cargo-and but few passengers—the ships rode light and made fast runs. On the return, or westward, passage, the cargoes normally consisted of such heavy articles as iron, coal, salt, machinery, manufactured goods, copper, etc., which worked in well, for the ‘tween decks were generally occupied by passengers to near capacity.” [37]

Transatlantic sailing packet lines operated between many American ports but the New York lines from the onset outclassed all others and throughout the entire era of packet sail. The New York transatlantic packet lines so dominated the Atlantic “ferry” to Liverpool and Havre that they quickly ‘killed off or wore down’ all competition, both domestic and foreign. The service record of American packets in the Atlantic “shuttle” (New York-Liverpool, London, or Havre) is remarkable, considering the seas and winds encountered. [38]

“During the forties (i.e. 1840s), the number of passengers entering the United States by East Coast ports increased nearly three-and-a-half-fold per year. In 1854 the number of arrivals was in excess of four hundred sixty thousand, and during the nine year period ending with 1854 the annual average was 271,867.” [39]

“The report of the British Select Committee on Merchant Shipping in 1844 acknowledged the fine quality and great prestige of American sailing packets and stated that much of the good reputation won and held, with the freely expressed preference of shippers that the United States lines enjoyed, was due to the superiority in design and construction of American ships, to prompt sailings as per advertised schedules, to able commanders, and to both the driving and maintenance of the ships, which resulted in fast passages and the discharge of cargoes in excellent condition, all of which added to prestige as well as to revenue.” [40]

Improvements were also made to ensure safer travel to various ports. Improvements were made in lighthouse design, illumination and construction. Coastal charts were updated with more detail on shoal formations. These technical innovations occurred in France, England and the United States. England centralized control over the management of lighthouses in 1836. The French government adopted uniform requirements for lighthouse construction in 1825. The United States had only 55 lighthouses on the east coast in 1820. By 1842, there were 256 lighthouses on the coast, along with 30 light boats and 1,000 buoys. The introduction of maritime insurance and life saving crews and local patrols mitigated the loss of ships and cargo. [41]

Immigrating to the United States: From Where and When?

When did John Sperber actually immigrate to the United States? Which European port did be depart from to sail to the United States? Why and how did he end up in Gloversville, New York?

These are questions that are subject to debate. The answers depend on one’s conclusions from judging the trustworthiness of conflicting sources of available information, the absence of specific information and placing those sources and blank spaces of information in the context of the broader historical patterns of immigration.

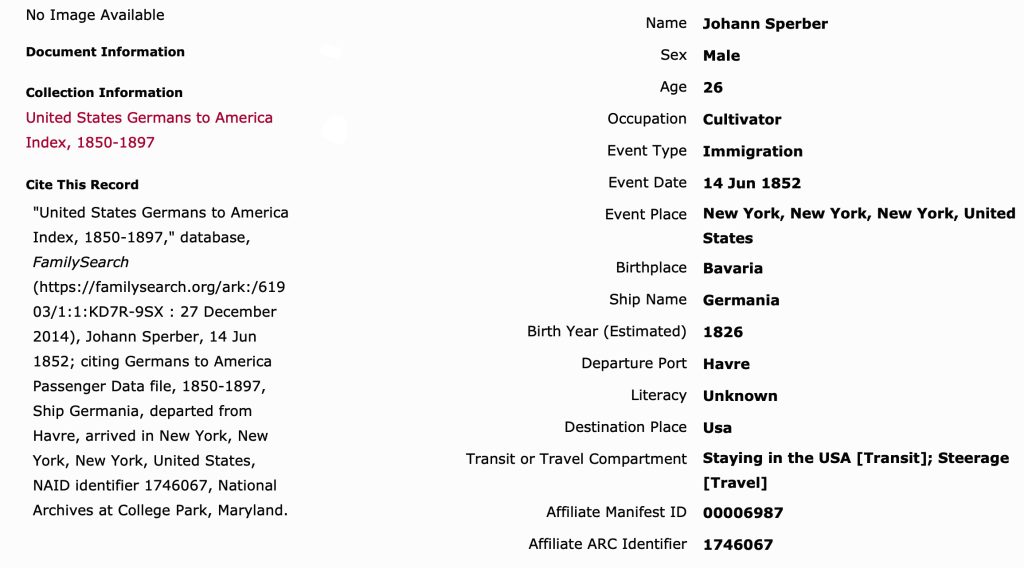

I believe it is “more than likely” that the Johann, John, Wolfgang Sperber arrived in New York City on June 14, 1852 on the ship “Germania” from the Le Havre Port in France.

I have couched my statement with “more than likely” based on:

- historical documentation on immigration patterns;

- secondary sources on the historical analysis of of the German immigration experience in the mid 1800s;

- historical documentation on the nature and conditions of roadways, waterways and railways in France and Germany in 1850 – 1853;

- a review of available ship manifest lists of German immigrants to America;

- locating a Johann Sperber in a ship manifest in June 14, 1852 on the ship Germania; and

- the comparison of conflicting information between census documents.

Historical Evidence Related to John Sperber’s Departure and Arrival

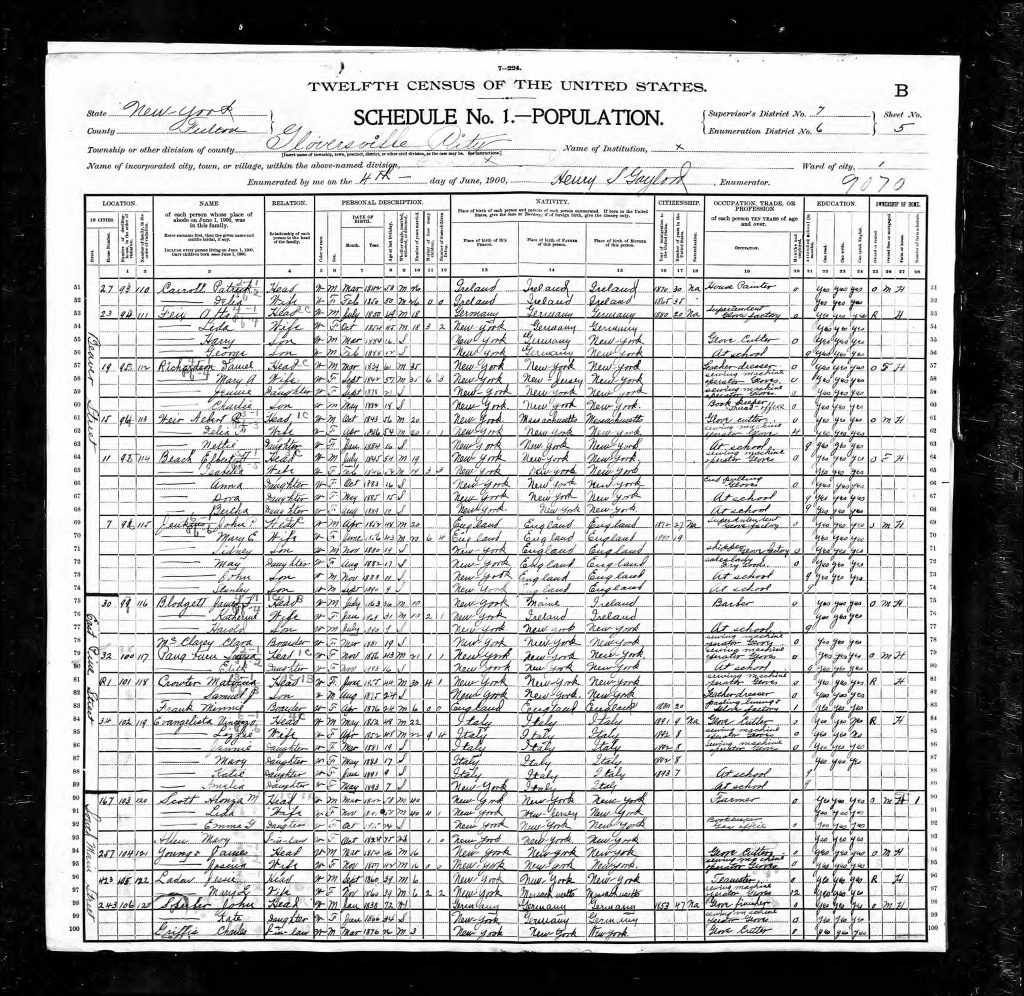

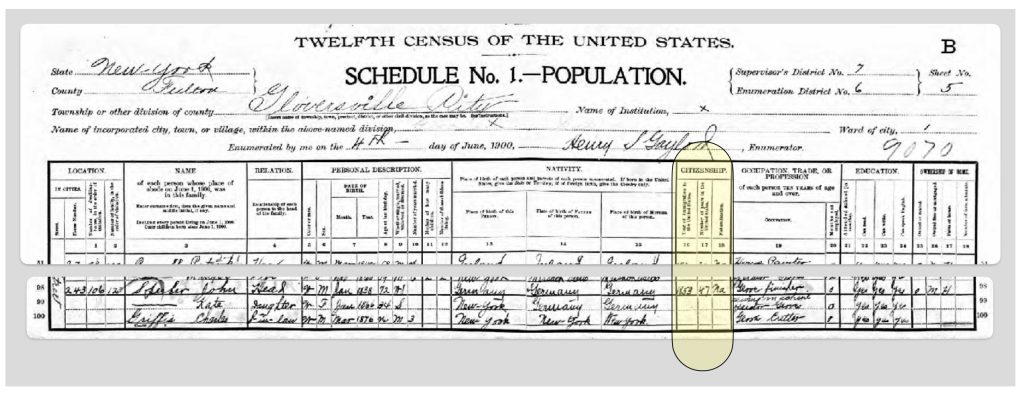

In 1900, the United States census asked questions regarding immigration dates and questions regarding country of origin. The Federal census questionnaires have changed every decade.

“In most cases the changes involved requesting more detailed information, but sometimes the modifications simply reflected prevailing social and political currents.” [42]

When John Sperber was around 72 years old, a census enumerator named Henry Gaylord recorded that John and his parents were born in Germany. The enumerator also documented that John had immigrated to the United States in 1853 and he had been in the United States for 47 years and was a naturalized citizen. [43]

John Sperber’s Reported Date of Immigration in 1900 U.S. Census [44]

Assuming John was the respondent to the census questions, despite being in his early 70’s at the time of the 1900 census, it might be expected that his recollection of when he arrived in the United States would be fairly accurate. For most immigrants, I imagine that the journey to America was not an easy one and it left an indelible memory of many experiences (e.g. leaving one’s homeland; the psychological, social and economic demands and uncertainties of emigrating; getting to the port; the travel on the ship; establishing a new home, etc). Emigrating from the homeland was perhaps one of the major milestones in any immigrant’s life.

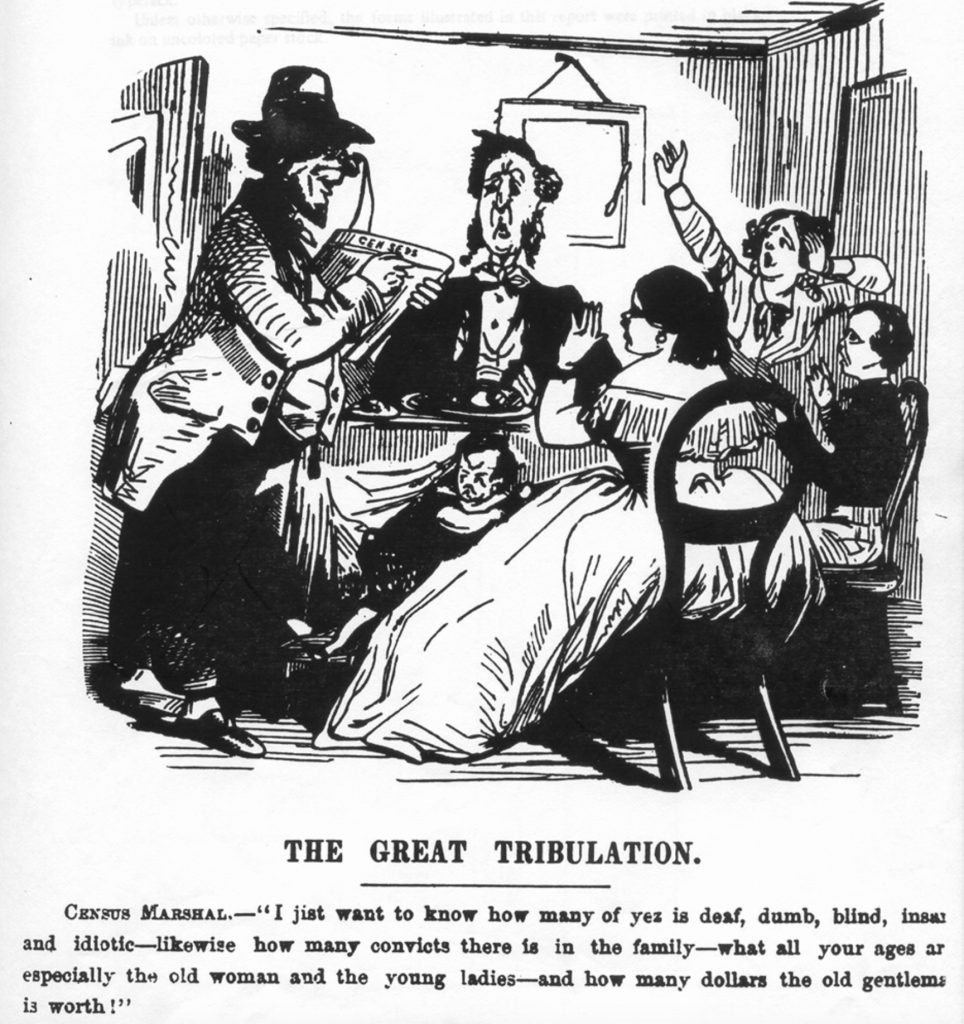

Cartoon about a crass enumerator asking questions for the 1860 U.S. Federal census. [45]

However, we do not know who interacted with Henry Gaylord, the enumerator. It is possible that John misspoke and stated the wrong year of his arrival. Perhaps the enumerator did not to talk to John but to another member of the household.

Census taking is not an exact science. Having information from alternative sources or other census years can provide a firmer basis to make a statement of fact about an ancestor. [46]

“Use census information with caution, since the information may have been given to a census taker by any member of the family, or by a neighbor. Some information may have been incorrect or deliberately falsified. Compare, contrast, and correlate each census population schedule with those of other census years, and with non-census documents to get the most accurate picture of the family history.” [47]

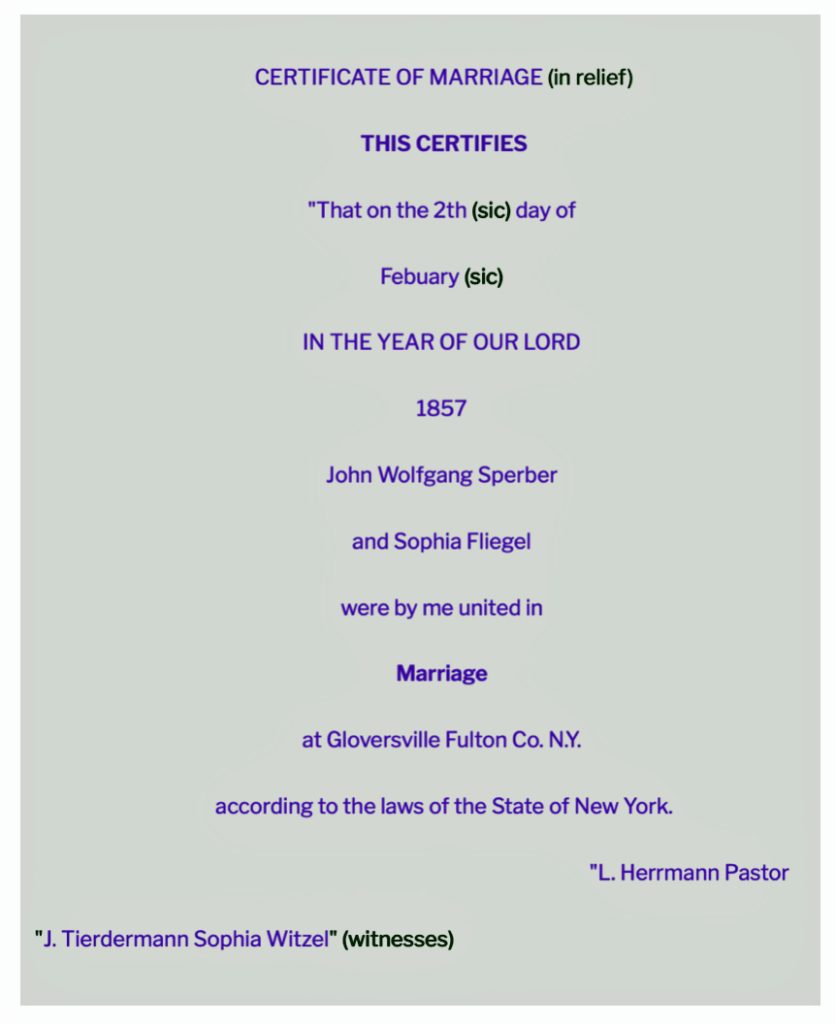

Despite the possible errors or misstatements of facts that might be found in the New York State or Federal censuses, I would not rule out the veracity of ‘facts’ written down by Mr. Gaylord on June 4th, 1900. We know John Sperber arrived in the United States in 1852-1853 or ‘around that time‘. We know John Sperber was in the United States before his marriage to Sophia Fliegel in February 1857. He did not travel with the Fliegel family to the United States in 1854. So it is highly likely that John Sperber immigrated to America between 1848 to 1856.

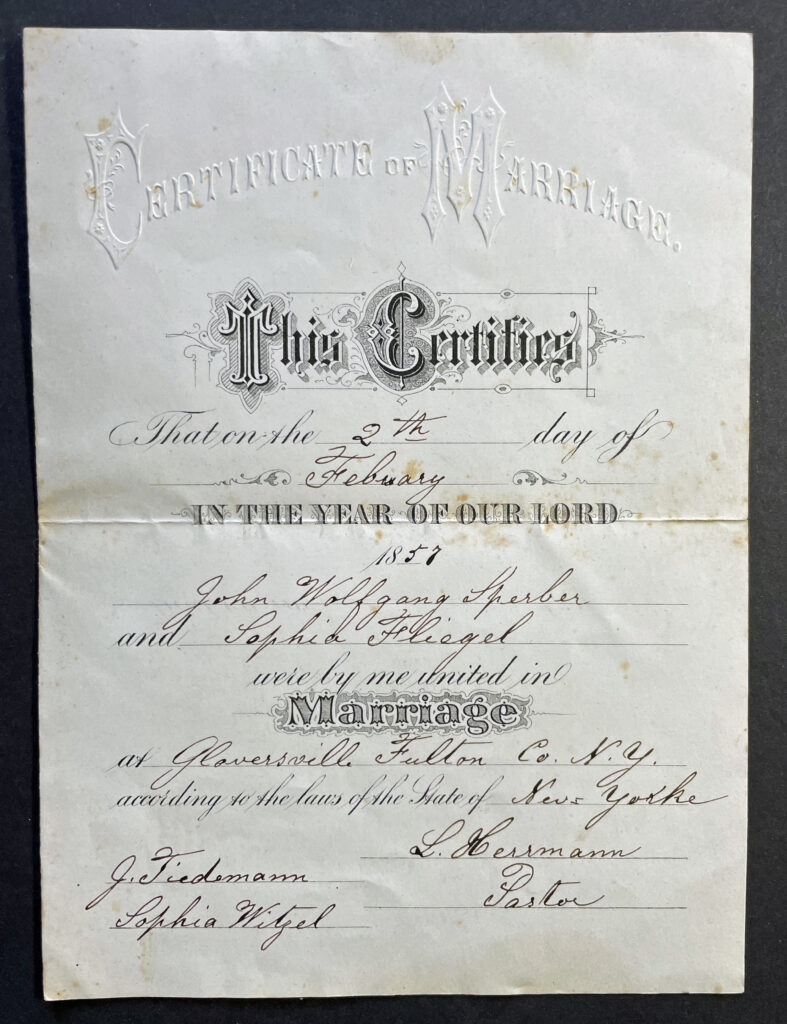

The following is a photograph of the original marriage certificate for John Sperber and Sophia Fliegel. [48]

Original Certificate of Marriage February 2, 1857

Review of Ship Manifest Lists

In my attempts to correlate census data with possible ship manifest lists, I have combed through manifest lists of ships that arrived in the United States from Northern Europe. I also have reviewed secondary data base sources of German Immigrants from a variety of sources. [49] I have also inspected microfiche copies of original ship manifests that are handwritten by captains or members of the ship’s crew that have sailed from Bremen, Hamburg, Rotterdam, Antwerp, Cologne, Liverpool, and Havre between 1850 and 1856. [50]

“Generally speaking the captains’ lists have the least value, as far as the spelling of the names is concerned. They were in most cases written by men who had no knowledge of German and to whom German surnames were a mystery they could not fathom. They wrote down the names as they were pronounced to them, spelling them as they would spell English names. As a result there are hundreds of names that have such fantastic forms that they are unrecognizable.” [51]

Discovering a passenger list with a name of a relative is often the result of patience, tenacity, focus and luck. Based on the zeal of discovering an ancestor’s name in a ship manifest, you constantly need to remind yourself of avoiding the pitfall of ‘forcing’ what you see into something that is not really there (e.g. your relative on a manifest list).

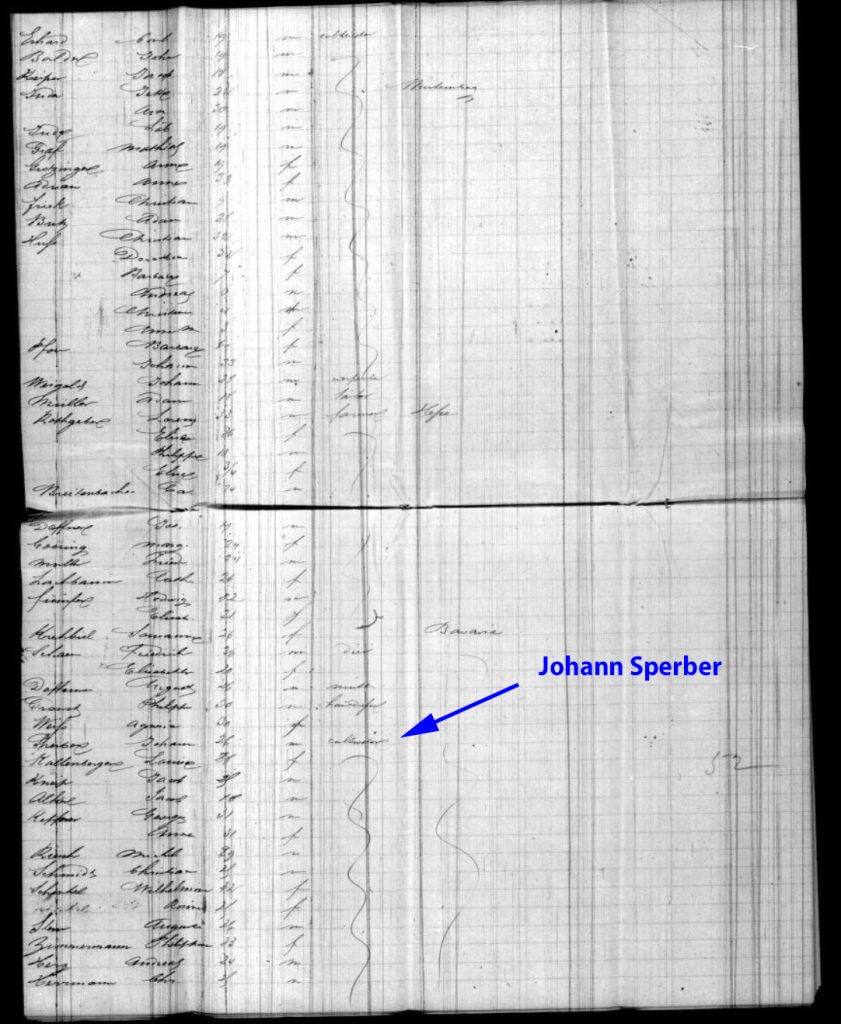

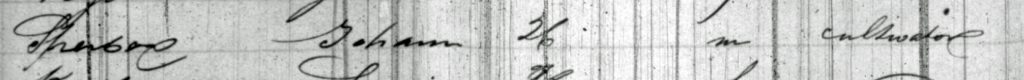

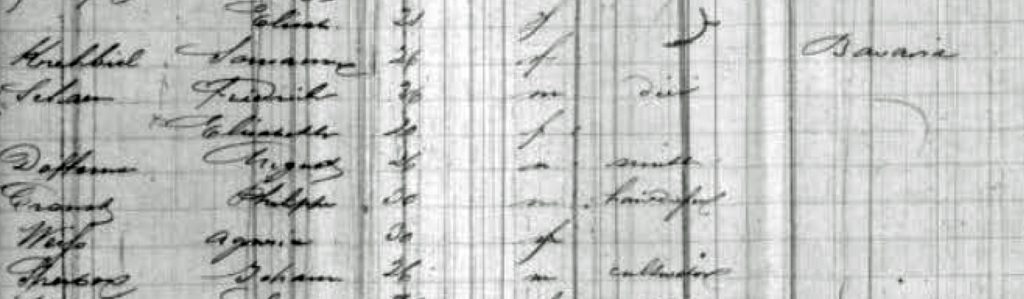

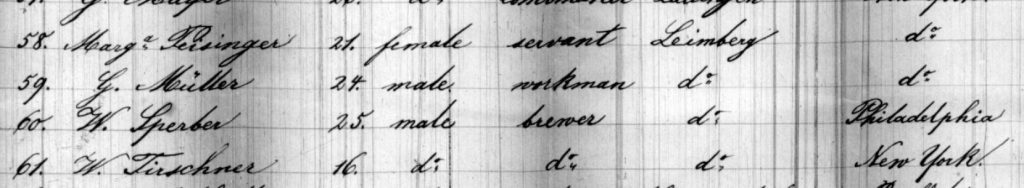

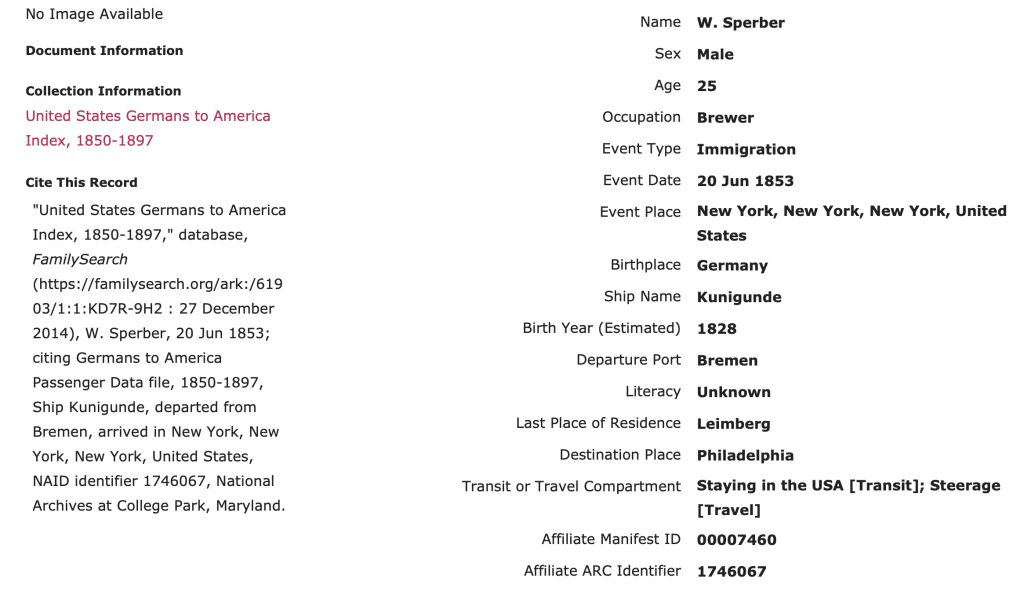

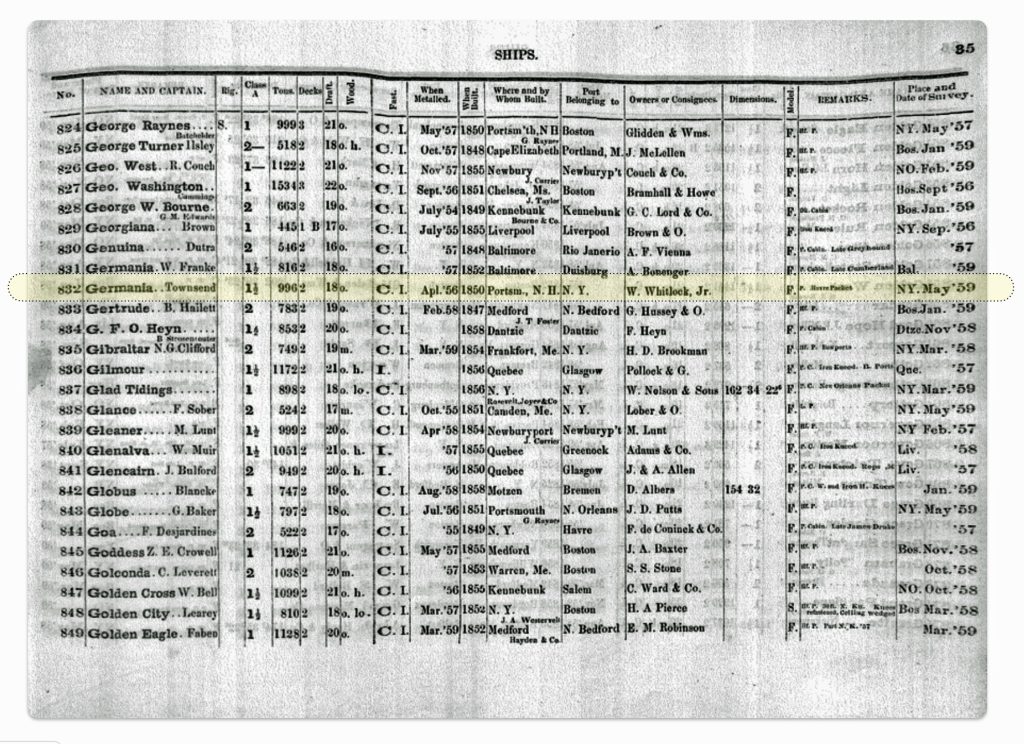

After reviewing available ship manifest sources, four records appeared to point to a John or ‘Johann Sperber’. [52] After a review of those records, I have, with reservation, concluded that John Sperber arrived in New York City on June 14, 1852 on the Ship Germania. [53]

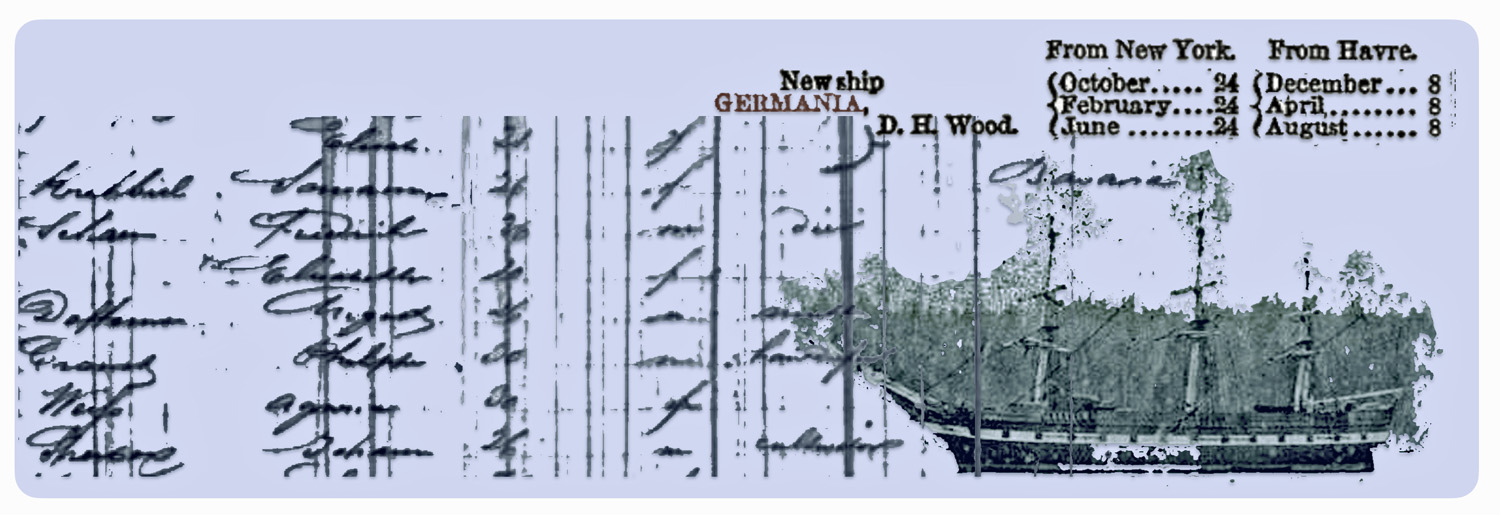

The following are pages five and six of the ship manifest. Johann Sperber is noted on the sixth page. The entire ship manifest list came be accessed as a PDF file.

Manifest of Ship Germania – Pages Five and Six – Line 13 of Page Six

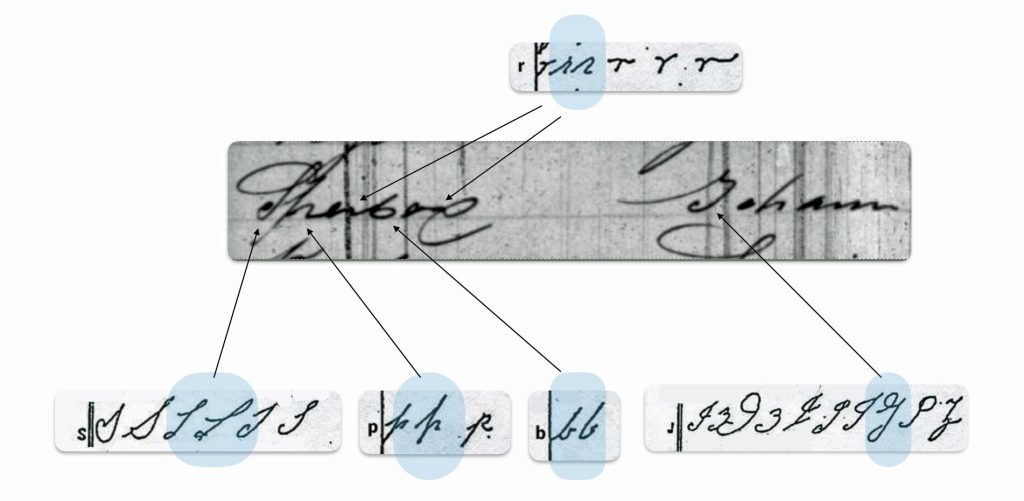

At first, it was not immediately apparent that the captain’s writing reflected the name ‘Johann Sperber’ on page six. Based on a blow-up view of line 13 below, initially the last name looks like a jumbled string of scribbling. Based on a rudimentary understanding of cursive writing in the 1800s, Johann can vaguely be made out. The “J” looks like a modern cursive variant of a “G”. The number “26” is decypherable. A word “cultivator” at the end of the line, describing his occupation, can be discerned. [54]

“The cultivateur, or cultivator, was a person who cultivated and exploited the land in order to get a crop.

“He may have been the proprietor of his own parcel(s) of land. He could, depending on the land size, have employed other agricultural workers. If he didn’t own the land, he was called a tenant farmer.“ [54]

Blow Up of “Johann Sperber” – Germania Ship Manifest June 14 1852 Page 6 Line 13

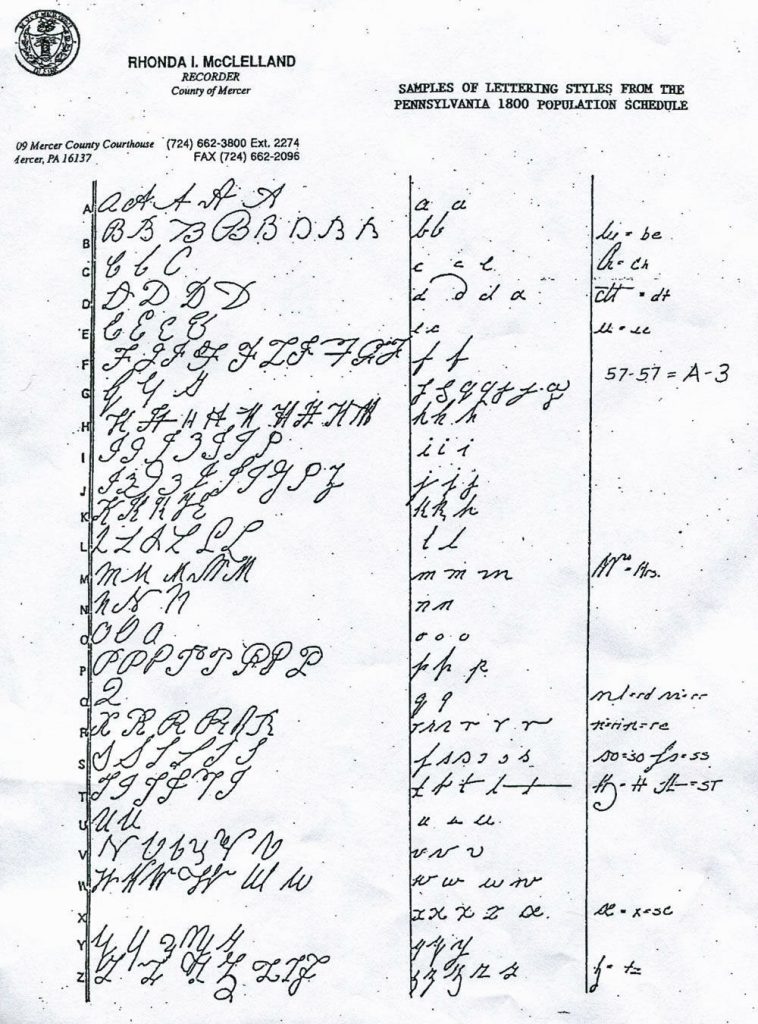

There is the inherent challenge conducting historical research associated with deciphering what was written on paper and being able to read what was written. Different styles of cursive writing in the United States as well as in the German states evolved concurrently through out the 1800s. Different styles of cursive writing can be found on documents in the mid 1800s that represent styles of writing that evolved in the late 1700s. In addition, everyone has their own style when it comes to penmanship. In fact, one could say that handwriting is as unique as fingerprints.

Within the context of the particular historical styles of cursive writing that was common in the mid 1800s, the handwriting of some ship captains looked so impeccable it almost looked like it was professionally printed. Others had handwriting that is hardly decipherable.

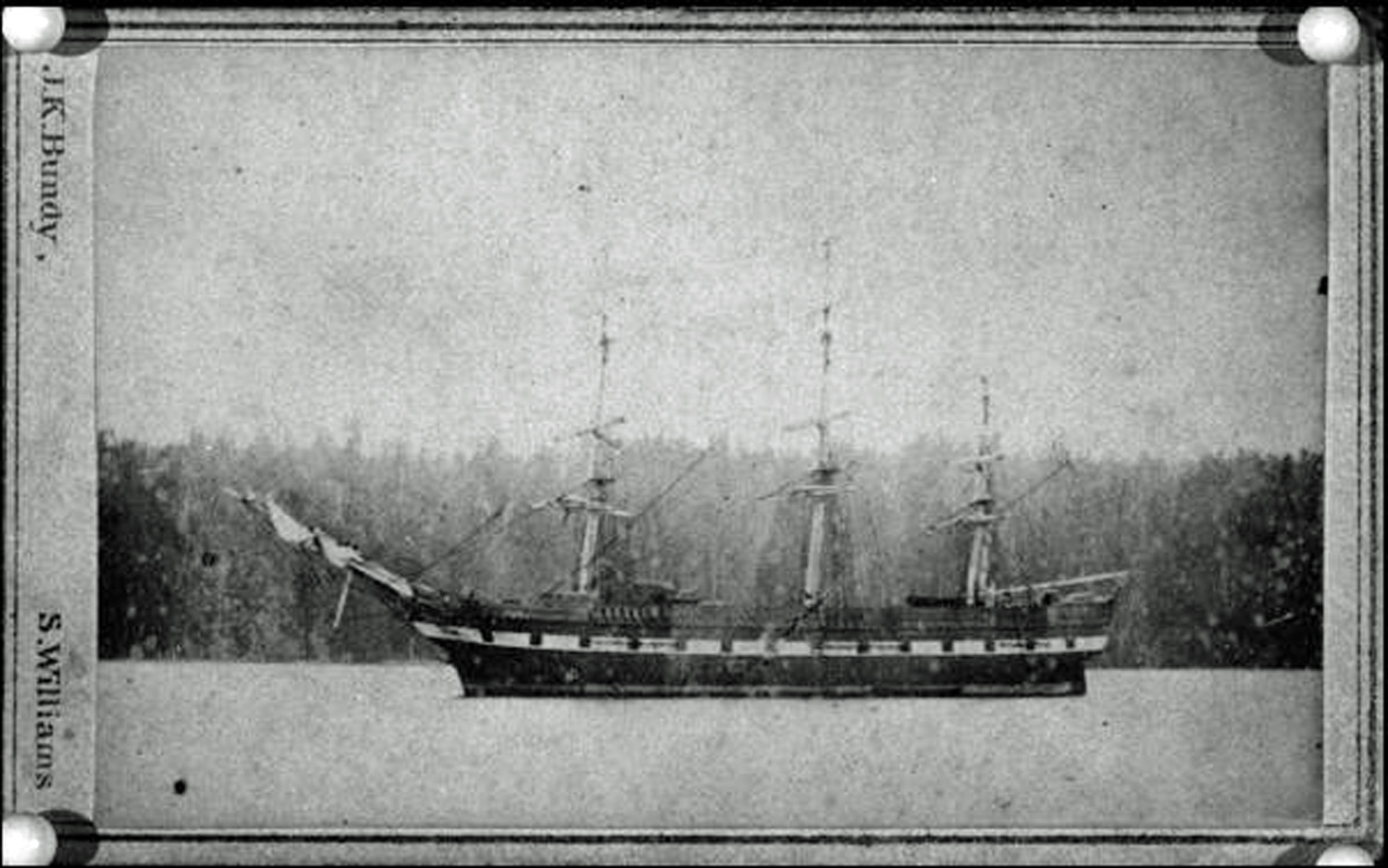

Ship GERMANIA at pier, Le Havre, France [55]

The ship Germania, was part of the American New York based Havre Whitlock Line. It was a shipping line that was prominent on the New York to Le Havre Atlantic shipping route.

“Unlike other American packet lines, Whitlock was the sole owner and operator of his ships. Usually the agents, builders, and captains of the individual ships were part owners of the vessels. Ships, each with a variety of owners, were then controlled and managed by the line in strict conformity with a general plan. “ [56]

Consistent with how the Havre Whitlock packet ship line was managed, it is presumed that the ship captain of the Germania, D. H. Wood, was an American. His penmanship was rather crude. The hand writing contained vestiges of an older style of American or English penmanship. In my research I found an example of various cursive versions of upper and lower case letters that were found in the 1800 census population schedule in Pennsylvania. [57}

An analysis of Captain Wood’s writing style found in the ship manifest list suggests the name on line 13 of page six is “Sperber Johann . . . 26. . . . m . . . cultivator” . There is a column after occupation that lists place of origin. It appears that the manifest list indicates “Bavaria” above John’s name, suggesting he and others were purportedly from Bavaria.

The following close up view of the hand written name on the ship manifest suggests that the name is Johann Sperber.

Close Up Analysis of Cursive Writing : “Sperber Johann”

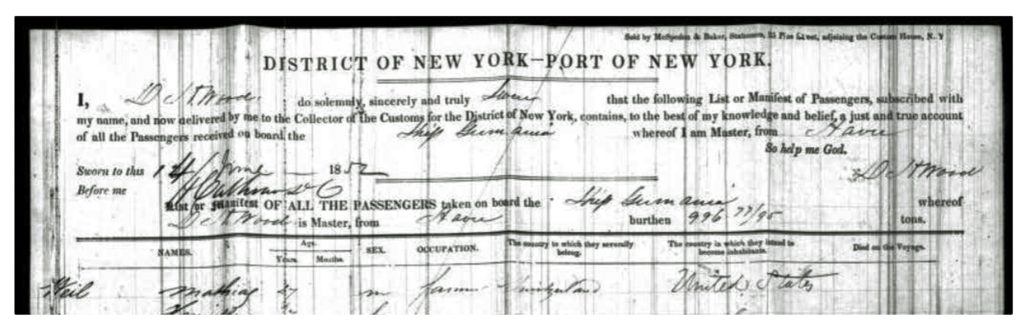

The following is the heading on the ship manifest for the voyage. The ship captain was D.H Wood.

Heading of Ship Manifest

The top of the manifest states:

I, D. H. Wood do solemnly, sincerely and truly swear that the following List or Manifest of Passengers, subscribed with my name, and now delivered by me to the Collector of Customs for the District of New York, contains, to the best of my knowledge and belief, a just and true account of all the Passengers received on board the Ship Germania whereof I am Master, from Havre. So help my God.

Sworn to this 14 June 1852 D H Wood.

List or Manifest OF ALL THE PASSENGERS taken on board the Ship Germania whereof D H Wood is Master, from Havre burthen 996 77/95 tons.

John Sperber’s Voyage to the United States On the Ship Germania

To summarize what has been found on a ship’s manifest, Johann Sperber traveled on the packet ship named Germania and departed from Havre, France. Based on the ship manifest records, Johan’s birth date was 1826. Johann Sperber was 26 years old when he came to America. His birth place was listed as ‘Bavaria‘. He stayed in the steerage area of the ship. The manifest indicates his occupation as a ‘cultivator‘, a farmer.

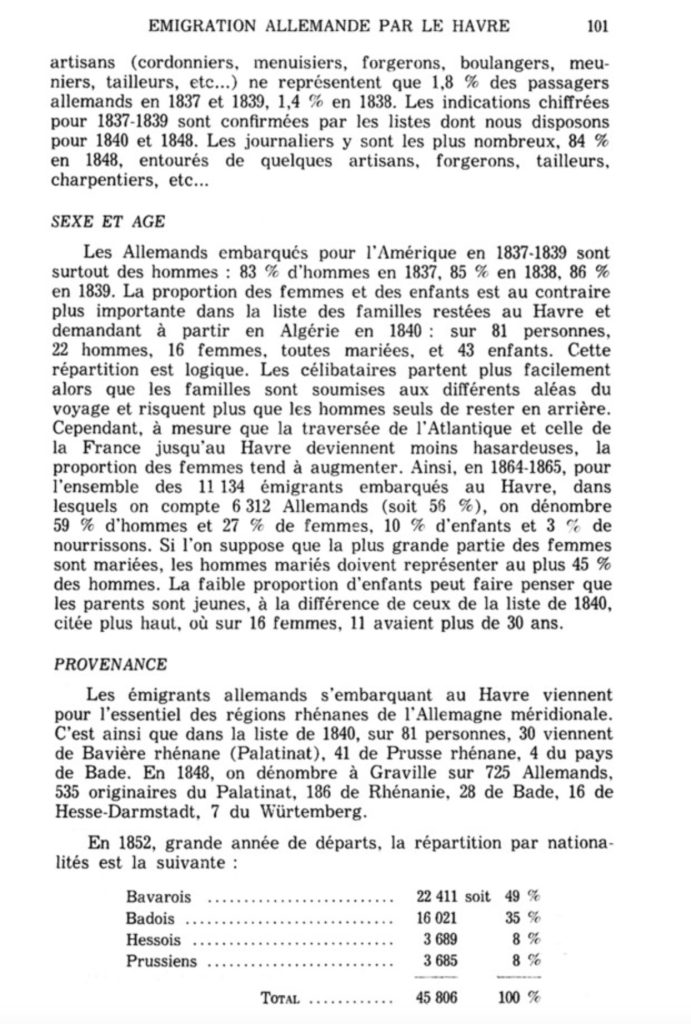

While ‘John Sperber’ was listed as being from Bavaria on the ship’s manifest, it is possible he was lumped in with the rest of the Germans on the ship. In 1852, German immigrants departing from Havre are. largely from Bavaria and Baden.

Table Four: Distribution of Nationalities Departing from Havre in 1852 [57a]

| Nationality | Number of Immigrants | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Bavaria | 22,411 | 49 % |

| Baden | 16,021 | 35 |

| Hesse | 3,689 | 8 |

| Prussia | 3,685 | 8 |

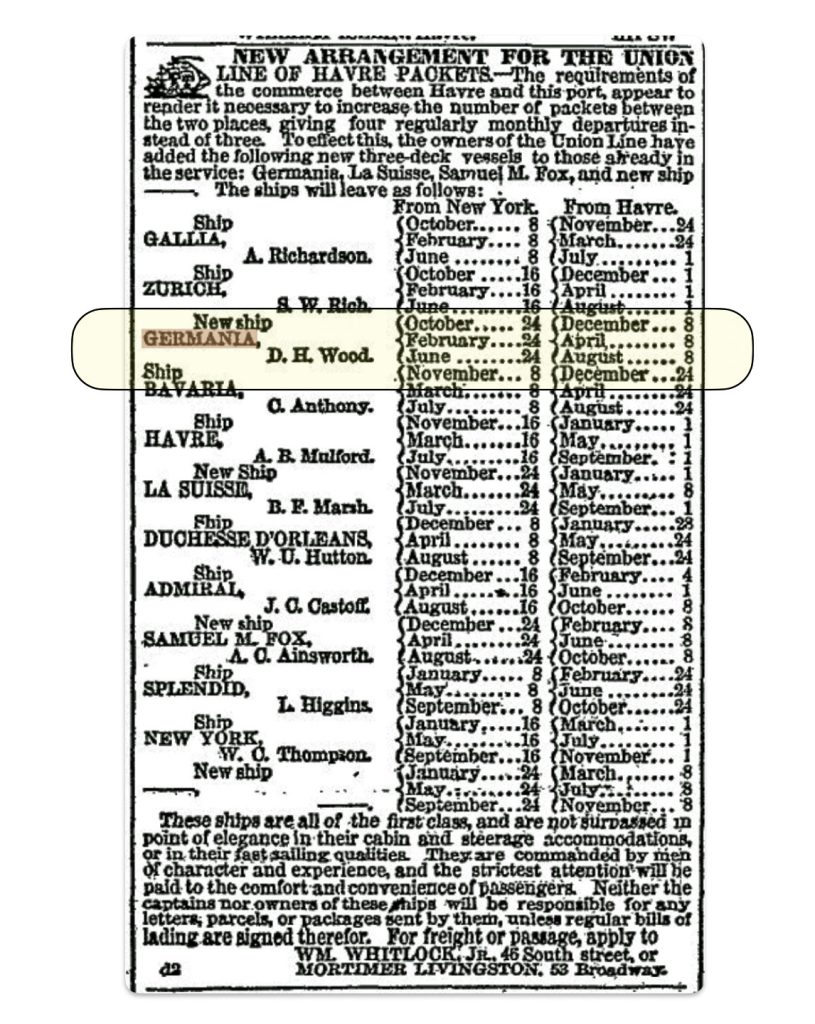

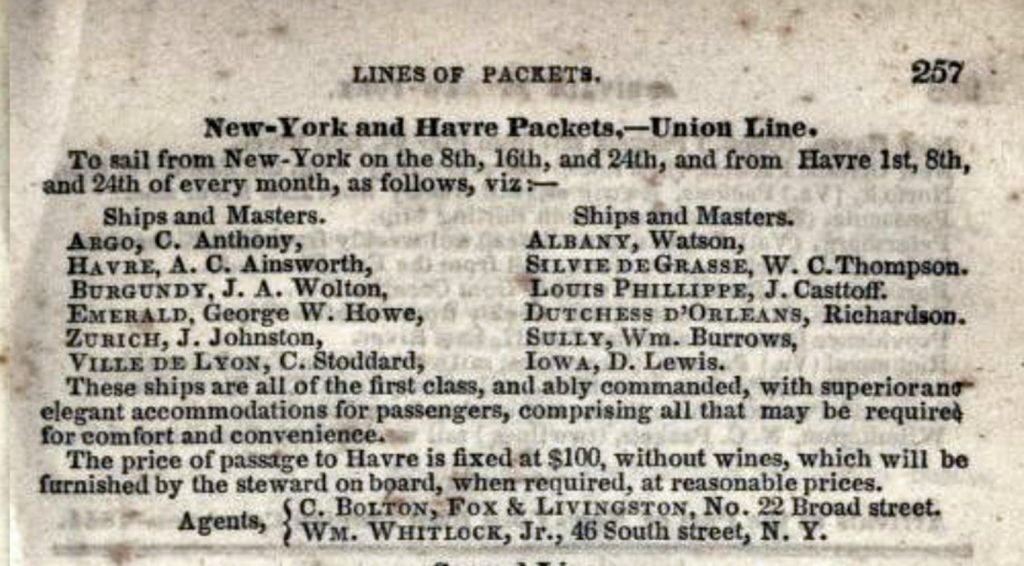

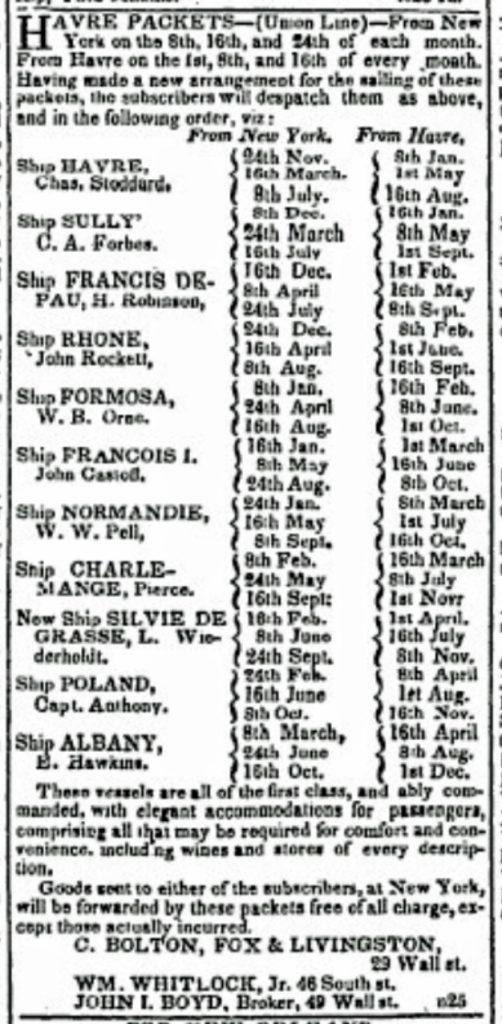

Assuming this manifest list includes our John Sperber, when John Sperber traveled from Le Havre to New York City, he utilized the services of the Union Line of Havre Packets for his voyage to America. At the time of his voyage, there were eleven ships that were making regularly scheduled round trip voyages between Le Havre and New York City for the Union Line of Havre.. At the time, the Germania was one of the newer ships in the Havre Whitlock Line.

As the advertisement for the shipping schedule for the Union Line in the semiweekly New York Evening Post indicates,

“The requirements of commerce between Havre and this port, appear to render it necessary to increase the number of packets between the two places, giving four regularly monthly departures instead of three. To effect this, the owners of the Union Line have added the following new three-deck vessels to those already in the service: Germania, La Suisse, Samuel M. Fox, and the new ship —– ….”

Advertisement for Union Line of Havre Packets between New York City and Le Havre 1850 [58]

This advertisement was posted without any revisions in the New York Evening Post between February 12, 1851 and August 10 1852. This implies that the monthly schedules for each of these ships were relatively stable, barring unforeseen changes in weather or other issues that might delay a scheduled departure date.

Based on the advertised schedule for the Union Line of Havre, the departure dates of the Germania are reflected in table five.

Table Five: Ship Germania Departure Schedule

| From NewYork | From Havre |

|---|---|

| October 24th | December 8th |

| February 24th | April 8th |

| June 24th | August 8th |

If John Sperber arrived in New York City on June 14, 1852 on the Germania, then based on the reliance of information found in the above advertised ship schedule, his ship was scheduled to depart from Le Havre on April 8th 1852. If the ship departed on time, this implies the journey took 64 days. However, as reflected in table six, records on the Westbound passages for the ship Germania indicate the longest trip was 52 days.

Table Six: Germania Westbound Passages in Days

| Service in Line | Shortest | Longest | Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 – 1863 (13 years) | 26 | 52 | 38 |

If we assume the advertisements in the Evening Post were accurate, then It would appear that the departure of John’s ship was delayed at the port of Le Havre. If the average westbound passage for the Germania was 33 days, then John’s voyage to Ameica may have started on or around May 8th, 1852.

A May 8th departure date would have been consistent with prior Union Line packet schedules since 1835. [59] In a March 1835 advertisement in the Evening Post, the Havre Union Line ship sailed from New York to Le Havre every month on the 8th, 16th, and 24th, and a ship sailed from Le Havre every month on the 1st, 8th, and 24th.

The New York State Register in 1845 also lists the packet schedule times for the Union Line of Havre in 1845 (see below). The same arrangements in 1835 existed ten years later. In 1845, The New York State Register identified the agents and ships that operated as the Havre Union Line. It announced that a Havre Union Line ship sailed from New York to Le Havre every month on the 8th, 16th, and 24th, and that a ship sailed from Le Havre every month on the 1st, 8th, and 24th.

New York and Havre Union Line Packets 1845 [60]

While the composition of the fleet of packet ships for the Union Line changes between 1845 and 1852 (the Germania was added to the the Union Line in 1850), the company may have had scheduled departures on the 8th of a given month despite what the company posted in the Evening Post.

The Havre Union Line was actually a ‘joint venture’ between the Havre Whitlock Line and the Havre Old Line. The Havre Union transatlantic packet line was organized in the 1830s from the joining of the Havre Old Line and the Havre Whitlock Line. Three of the ships listed in the 1850 advertisement were owned by William Whitlock: the Gallia, Germania and the Bavaria. [61]

The Germania was a three masted, square-rigged ship, built in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 1850. The ship weighed 996 tons. It was 170 ft 8 in length and 35 ft 6 in wide and 17 ft 8 in depth in the hold of the ship. The Germania had three decks and the draft was 20 feet. [62]

Ship GERMANIA at pier, Le Havre, France [63]

The Germania sailed in William Whitlock’s line as part of the stable of New York to Havre packet ships from 1850 until the end of the Line in 1863.

In 1853, the Captain D.H. Wood commissioned a painting of the ship in Havre. At the time of writing this story, the painting is available for sale for $10,000! [64]

Frederic Roux Oainting of the Germania Presented to Captain D. Wood

After 1863, the ship was a transient (the sailing equivalent to a tramp freighter) for Whitlock. [65] The Germania was advertised as sailing in the Ladd Line of New York-New Orleans packets in 1852, and in the Brigham Line of New York-New Orleans packets in 1854. [66]

Continuation of the Story

The second part of John Sperber’s story describes his journey from Baden-Baden to Le havre based on historical evidence and historical accounts.

Sources

Feature Photograph: This is a collage of images that are part of this story. The packet ship Germania is from a photograph of the ship taken in 1863. Long after Johann Speber sailed on the Germania, the photopgra was taken at the end of her active life in 1863 on the other side of the United States (see below). The portion of the handwritten ship manifest comprises most of the collage. Johann Speber’s name is written in the lower left hand corner. In the upper right hand corner is a portion of an advertisement in 1850 that provides the scheduled voyages of the Germania between New York City and Havre. It also lists D. H. Wood, the Ship Captain. The advertisement is mentioned in the story.

GERMANIA, built 1850, carte de visite

Feature Photograph: GERMANIA, built 1850, carte de visite, Bundy & Williams USA, WA, circa 1863; overall size of original photograph: 2 1/2 x 4 in., sepia tone.

The ship was anchored at Port Ludlow, Puget Sound, about 1863, Chas. H. Townsend was the Captain of the ship at this time.. On left margin was “J. K. Bundy, S. Williams”; on reverse “BUNDY & WILLIAMS/ 314 & 326 Chapel St./ NEW HAVEN, CT./…”; in pencil. Copied from negative given/ Chas. H. Townsend by a photographer/ at Port Ludlow, Puget Sound/ about 1863. Just as the ship anchored the photograph was taken. The ship was built in 1850 at Portsmouth, N. H. by Fernald & Pettigrew. The ship was 996 tons, 170.7 x 35.5 x 17.7 and was owned by the New York & Harve Union Line.

Photograph source: http://mobius.mysticseaport.org/media.php?module=objects&type=related&kv=197383&media=0

Carte de visite was a photographic format first produced in the 1850s, which became popular in the 1860s. It consisted of a small photographic print (typically an albumen print) mounted on card stock measuring approximately 2 1/2 x 4 1/4 inches. The modest and uniform size of the carte de visite made it, along with the stereographic postcards, relatively cheap to produce and helped to popularize photography in the late 19th century.

Carte de Visite Collection, Digital Commonwealth, Massachusetts Collections Online, Boston Public Library, https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/collections/commonwealth:44558j44c

Carte de visite, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 10 October, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carte_de_visite

The portion of the ship manifest in the feature photograph is from page 6 of the ship manifest that lists Johann Sperber:

[1] Winfield P. Sperber, Birth Date: 18 Oct 1916, Birth Place: Gloversville, New York, USA, Birth certificate Number: 84589, New York State Department of Health; Albany, NY, USA; New York State Birth IndexYear: 1916. Source: Ancestry.com. New York State, Birth Index, 1881-1942 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2018.

Original data: New York State Birth Index, New York State Department of Health, Albany, NY.

Winflied P Sperber, Death Date: 18 Oct 1916, Death Place: Gloversville, New York, USA, Death Certificate Number: 61202; New York Department of Health; Albany, NY; NY State Death Index Source Information: Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Death Index, 1852-1956 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2017.

Original data:NY State Death Index, New York Department of Health, Albany, NY.

“Premature birth; funeral was on October 19, 1916, undertaker was John J. Dingnan.”

Winfield Sperber, Cemetery: Prospect Hill Cemetery; Burial or Cremation Place: Gloversville, Fulton County, New York, United States of America, Find A Grave, Memorial ID: 114577146, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/114577146/winfield-sperber

[2] Alfred Lotka, A. 1931. The extinction of families, Journal Washington Academy Sciences Vol 31, 1931 pp. 377-380

Alfred J. Lotka, Sterility in American Marriages, Statistics, Volume 14, Statistics, 1928, talk given Nov 21 1927, Pages 99 – 109 https://www.pnas.org/doi/pdf/10.1073/pnas.14.1.99

[3] Rob Spencer, an authoritative source of Genealogical DNA research and innovative amateur DNA genealogist has produced a number of explorations on genetic genealogy and population genetics. One subject he has addressed is the subject of the probability of the extinction of a Y-DNA line. In Western societies, surnames usually follow the male line. Hence Y-DNA lines of extinctions mirror surname extinctions in Western Europe and America.

See: Rob Spencer, Extinctions and Bottlenecks, Tracking Back: a website for genetic genealogy tools, experimentation, and discussion, http://scaledinnovation.com/gg/gg.html?rr=gwatson

John and Sophia had children between 1858 and 1878. Their first child was born prior to their marriage. The fertility rate in the United States between 1865 and 1875 declined from 5.8 to 4.9. The fertility rate for their children’s generation was 4.0 (between 1880 and 1890). The fertility rate for the third generation (initial child bearing years between 1900 and 1910) was 3.49.

Chart from: Aaron O’Neill, Total fertility rate in the United States from 1800 to 2020, June 21, 2022, Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1033027/fertility-rate-us-1800-2020/#statisticContainer

Total fertility rates for the white population for these time periods are slightly lower.

| Year | Total Fertility Rate for White Population |

|---|---|

| 1850 | 5.42 |

| 1860 | 5.21 |

| 1870 | 4.55 |

| 1880 | 4.24 |

| 1890 | 3.87 |

| 1900 | 3.56 |

| 1910 | 3.42 |

Source: Haines, Michael. “Fertility and Mortality in the United States”. EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. March 19, 2008. URL https://eh.net/encyclopedia/fertility-and-mortality-in-the-united-states/

Based on Spencer’s calculations, an average fertility rate, using Haines’ figures, between 1900 and 1910 of roughly 3.5 would imply a probability rate of eventual extinction at 30 percent (below).

See also: Galton–Watson process, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 10 August 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galton–Watson_process

[4] Lencer, Karte der Markgrafschaft Baden-Baden mit allen Territorien von 1535 bis 1771 (Map of the Margraviate of Baden-Baden with all territories from 1535 to 1771), Wikicommons, Sep 2008, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Markgrafschaft_Baden-Baden.png

[5] TestTube-commonswiki, Die territorialen Zuwächse Badens zwischen 1803 und 18197 Dec 2013, (The territorial gains of Baden between 1803 and 1819), Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baden-1803-1819.png

This is a map that was in German and I have modified and simplified the explanation in English.

[6] Margraviate of Baden-Baden, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 26 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margraviate_of_Baden-Baden

Margraviate of Baden, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 28 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margraviate_of_Baden

Baden, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 16 July 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baden

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Baden, Grand Duchy of“. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 184–188. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclopædia_Britannica/Baden,_Grand_Duchy_of

Electorate of Baden, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electorate_of_Baden

Grand Duchy of Baden, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 16 October 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Duchy_of_Baden

Grand Duchy of Baden State Railway, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 21 August 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Duchy_of_Baden_State_Railway

Baden History, FamilySearch, This page was last edited on 14 June 2022, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Baden_History

[7] Margraviate of Baden, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 28 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margraviate_of_Baden

Margraviate of Baden-Durlach, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 13 January 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margraviate_of_Baden-Durlach

Margraviate of Baden-Baden, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 26 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margraviate_of_Baden-Baden

Margraviate of Baden-Hachberg, Wikipedia, his page was last edited on 24 December 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margraviate_of_Baden-Hachberg

Grand Duchy of Baden, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 16 October 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Duchy_of_Baden

[8] Electoral Palatinate, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 6 November 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electoral_Palatinate

[9] History of Hesse, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 August 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Hesse

Ingrao, Charles W. The Hessian mercenary state: ideas, institutions, and reform under Frederick II, 1760-1785 (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

[10] Grand Duchy of Baden, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 16 October 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Duchy_of_Baden

Selgert, Felix. (2013). The Implementation of Administrative and Legal Reforms in the German State of Baden during the 19th Century. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290431368_The_Implementation_of_Administrative_and_Legal_Reforms_in_the_German_State_of_Baden_during_the_19th_Century

[11] Störfix, Map of the Grand Duchy of Baden (Germany), from 1819 to 1918, Karte des Großherzogtums Baden von 1819 bis 1918 bzw. der Republik Baden bis 1945, Wikicommons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_Baden_(1819-1945).png

[12] Free imperial city, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 November 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_imperial_city

[13] States of the German Confederation, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 16 April 2023, Map of German states 1815-1866, by Ziegelbrenner, from Wikipedia, Karte des Deutschen Bundes 1815–1866 / Map of German Confederation 1815–1866, 19 Jan 2008, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/States_of_the_German_Confederation

[14] The source for John Sperber’s birth date are varied. However, the date of January 2nd, 1828 is found in two sources.

One source is found in a Find A Grave website record.

Vital statistics on John Sperber based on gravesite information: John Wolfgang Sperber, BIRTH: 2 Jan 1828, Baden-Württemberg, Germany; DEATH: 27 Jan 1905 (aged 77), Gloversville, Fulton County, New York, USA; BURIAL: Prospect Hill Cemetery, Gloversville, Fulton County, New York, USA; PLOT: Sec 8; MEMORIAL ID158839082 · View Source, Find A Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/158839082/john-wolfgang-sperber

The other source is an handwritten list of Sperber family members and their respective birthdates. The page is part of the remains of a book for documenting vital facts for Sperber family members: marriages, births and deaths. The book is in poor condition. The pages are not attached but the handwriting is very clear.

The names of John and Sophia Sperber and their children are listed at the top of the page. It is not known who wrote the list of the Sperber family.

In different handwriting, the names of Harold and Evelyn Griffis and their first three children are handwritten at the base of the page. The Griffis family births were obviously added to the list by another family member. Based on the handwriting, I believe it is the handwriting of Harold Griffis.

Birth Places Reported in Federal and State Censuses

| Reported Birthplace | Reported Parent’s Birthplace | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Baden | – – | Year: 1870; Census Place: Johnstown, Fulton, New York; Roll: M593_938; Page: 183A |

| Baeren | Baeren | Year: 1880; Census Place: Gloversville, Fulton, New York; Roll: 834; Page: 95A; Enumeration District: 006 Enumerator probably phonetically wrote what was heard. |

| Germany | – – | New York State Archives; Albany, New York, USA; Census of the State of New York, 1865 |

| Germany | – – | New York State Archives; Albany, NY, USA; Census of the State of New York, 1875 |

| Baden-Württemberg | – – | Find A Grave, Memorial ID: 158839082 |

[15] This is based on his reporting to a census enumerator in the 1880 census. Year: 1880; Census Place: Gloversville, Fulton, New York; Roll: 834; Page: 95A; Enumeration District: 006, Line 30

[16] Loretto Dennis Szucs and Mathew Wright, Overview of the U.S. Census, Rootsweb, This page was last edited on 24 April 2016, https://wiki.rootsweb.com/wiki/index.php/Overview_of_the_U.S._Census

[17] History of German-American Relations > 1683-1900 – History and Immigration, U.S. Diplomatic Mission to German, This page was updated June 2008, https://usa.usembassy.de/garelations8300.htm

Irish and German Immigration, U.S. History , https://www.ushistory.org/us/25f.asp

Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: The Call of Tolerance, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/german/call-of-tolerance/

Amanda A. Tagore, Irish and German Immigrants of the Nineteenth Century: Hardships, Improvements, and Success, Pace University: Pforzheimer Honors College, May 2014, https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1144&context=honorscollege_theses

[18] F. Burgdorfer, Chapter XII Migration Across the Frontiers of Germany, Walter F. Wilcox, ed, International Migrations, Volume II, Interpretations, NBER, 1931, pages 347, https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c5114/c5114.pdf

[19] United States. Department of Homeland Security. Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2008. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, 2009, Table 2, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Yearbook_Immigration_Statistics_2008.pdf

See also:

History of German-American Relations > 1683-1900 – History and Immigration, U.S. Diplomatic Mission to German, This page was updated June 2008, https://usa.usembassy.de/garelations8300.htm

Irish and German Immigration, U.S. History , https://www.ushistory.org/us/25f.asp

Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: The Call of Tolerance, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/german/call-of-tolerance/

Amanda A. Tagore, Irish and German Immigrants of the Nineteenth Century: Hardships, Improvements, and Success, Pace University: Pforzheimer Honors College, May 2014, https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1144&context=honorscollege_theses

[20] Ira Glazier, Ed., Germans to America Series II: Lists of Passengers Arriving at U.S. ports in the 1840s, Volume 6 April 1848 – October 1848, Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc 2003, Page xii

[21] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Page 286

[22] Ibid, Page 287;

Also: F. Burgdorfer, Chapter XII Migration Across the Frontiers of Germany, Walter F. Wilcox, ed, International Migrations, Volume II, Interpretations, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), 1931, pages 364, https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c5114/c5114.pdf

[23] Friedrich R. Wollmershäuser, Passengers Listed in the “Allgemeine Auswanderung – Zeitung”, 1848 – 1869, Masthof Press, 2014

Emigration of Prisoners from Baden, Baden Emigration and Immigration, FamilySearch Wiki, This page was last edited on 16 March 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Baden_Emigration_and_Immigration

[24] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Page 164

[25] Hansen, Page 280

William Dillingham, United States Immigration Commission (1907 – 1910) Statistical Review of Immigration 1820 -1910, U.S. Immigration Commission, Reports of the immigration Commission, Reports Volume III, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1911, Page 416 https://archive.org/details/reportsofimmigra03unitrich/page/416/mode/2up

[26] United States. Department of Homeland Security. Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2008. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, 2009, Table 2, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Yearbook_Immigration_Statistics_2008.pdf

[27] F. Burgdorfer, Chapter XII Migration Across the Frontiers of Germany, Walter F. Wilcox, ed, International Migrations, Volume II, Interpretations, NBER, 1931, pages 317, https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c5114/c5114.pdf

Ira Glazier, Ed., Germans to America Series II: Lists of Passengers Arriving at U.S. Ports in the 1840s, Volume 6 April 1848 – October 1848, Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc 2003, Page xiii

[28] Must an ‘Immigrant’ Also Be an ‘Emigrant’? And what’s an émigré?, Meriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/grammar/immigrant-emigrant-emigre-refugee-how-to-tell-the-difference

Shundalyn Allen, “Immigrate” vs. “Emigrate”—What’s the Difference?, Updated 27 Jun 2023, Grammerly, https://www.grammarly.com/blog/emigrate-immigrate/

What Is The Difference Between “Immigration” vs. “Emigration”?, Updated 3 October 2019, https://www.dictionary.com/e/immigrants-vs-emigrants-vs-migrants/

[29] F. Burgdorfer, Chapter XII Migration Across the Frontiers of Germany, Walter F. Wilcox, ed, International Migrations, Volume II, Interpretations, NBER, 1931, pages 317, https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c5114/c5114.pdf

[30] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Page 289

[31] Ira Glazier, Ed., Germans to America Series II: Lists of Passengers Arriving at U.S. Ports in the 1840s, Volume 6 April 1848 – October 1848, Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc 2003, Page xiii

[32] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Pages 174 – 178

Admiralty Compass Observatory, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 13 November 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Admiralty_Compass_Observatory Marine chronometer, Wikipedia, The Page was last edited on 23 Nov 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marine_chronometer

Henry Barrow & Co. Admiralty Standard Compass c.1845, Compass Library, https://www.compasslibrary.com/en-us/products/henry-barrow-admiralty-standard-compass-c-1845 In the event that the example of this type of compass has been sold subsequent to posting this story, see PDF version.

Jonathan D. Betts, Chronometer Timekeeping Device, Britanica, https://www.britannica.com/technology/chronometer Chronometer watch, Wikipedia,his page was last edited on 15 December 2023 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chronometer_watch

Marine chronometer, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 21 November 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marine_chronometer

The above photograph is of a marine chronometer by Charles Frodsham of London, shown turned upside down to reveal the movement. Source: Marine Chronometer #2299 made by Charles Frodsham of London, circa 1844 – 1860. From the Ladd Observatory collection. Frodsham chronometer mechanism, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Frodsham_chronometer_mechanism.jpg

The above photograph is a an antique small size English chronometer in mahogany box with brass mounts. By Widenhead London. ca. 1840. Source: Dutch Antiques, https://dutchtimepieces.com/product/antique-english-chronometer/

[33] Fairburn, William A. (1945). Merchant Sail, Volume II Center Lovell, ME: Fairburn Marine Educational Foundation. Page 1083 https://www.google.com/books/edition/Merchant_Sail/p3jVAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Havre+Whitlock+line&pg=PA1198&printsec=frontcoverPage 1083

[34] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Page 175 – 178

Robert McNamara, Packet Ship: Ships that Left Port on Schedule were Revolutionary In the Early 1800s, Mar 6, 2017, ThoughtCo., https://www.thoughtco.com/packet-ship-definition-1773390

“Packet Boats .” History of World Trade Since 1450. . Encyclopedia.com.(December 11, 2023). https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/packet-boats

[35] Robert Greenhaigh Albion, Square-riggers on schedule: the New York sailing packets to England, France, and the cotton ports. London: Princeton University Press, 1938. Page 77

[36] Fairburn, William A. (1945). Merchant Sail, Volume II Center Lovell, ME: Fairburn Marine Educational Foundation. Page 1078 https://www.google.com/books/edition/Merchant_Sail/p3jVAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Havre+Whitlock+line&pg=PA1198&printsec=frontcover

[37] Fairburn, Pages 1074-1075

[38] Fairburn, Page 1073

[39] Fairburn , Page 1073

[40] Fairburn, William , Page 1074

[41] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration, 1607 – 1860, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951, Page 17 – 1787

[42] Beth Jarosz, Continuity and Change in the U.S. Decennial Census, March 25, 2018, Population Reference Bureau (PRB) , https://www.prb.org/resources/continuity-and-change-in-the-u-s-decennial-census/

[43] The 1900 U.S. Federal Census asked six questions that were directly related to place of birth and whether the respondent had immigrated to the United States.

Questions from the 1900 U.S. Census

| Question Number | Question |

|---|---|

| 13 | What was the person’s place of birth? |

| 14 | What was the person’s father’s place of birth? |

| 15 | What was the peson’s mother’s place of birth? |

| 16 | What year did the person immigrate to the United States? |

| 17 | How many years has the person been in the United States? |

| 18 | Is the person naturalized? |

U.S. Census questions for 1900, General Population Schedule, United Stated Census, History, Index of Questions, https://www.census.gov/history/www/through_the_decades/index_of_questions/1900_1.html

Frederick G. Bohme, Twenty Censuses: Population and Housing Questions, 1790-1980, U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Census, Oct 1979, Washington: Government Printing Office, Page 34, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.319510030561275&seq=42

[44] John Sperber indicated to the census enumerator that he immigrated to the United States in 1853, See line 98 on the following U.S. census sheet.

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1900. T623, 1854 rolls. Year: 1900; Census Place: Gloversville Ward 1, Fulton, New York; Roll: 1036; Page: 5; Enumeration District: 0006, Bounded By Forest, Fremont, Steele Ave, City Limits, South Main , Page 5, Line 98.

[45] Frederick G. Bohme, Twenty Censuses: Population and Housing Questions, 1790-1980, U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Census, Oct 1979, Washington: Government Printing Office, Page 6, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.319510030561275&seq=14

[46] Claire Prechtel-Kluskens, Who Talked to the Census Taker, Oct/Nov/Dec 2005,NGC Magazine, National Archives, Pages 32 – 35 https://twelvekey.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/ngsmagazine2005-10.pdf

Diana L. Magnuson, History of Enumeration Procedures , 1790 – 1940, Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS USA), https://usa.ipums.org/usa/voliii/enumproc1.shtml

Magnuson and King, “Enumeration Procedures”, in Historical Methods, Volume 28, Number 1, Pages 27-32, Winter 1995.

Diana L. Magnuson, The Making of a Modern Census: the United States Census of Population, 1790-1940, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Minnesota, 1995.

Colby Gardner, Writing the United States Census, Nov 25, 2016, Dartmouth University, History 90.01: Topics in Digital History, U.S. History Through Census Data, https://journeys.dartmouth.edu/censushistory/2016/11/16/writing-the-united-states-census/

Ruggles, S. and Magnuson, D.L., “It’s None of Their Damn Business”: Privacy and Disclosure Control in the U.S. Census, 1790–2020. Population and Development Review, 49: 651-679, 2023 https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12580

Schor, Paul, ‘Introduction’, Counting Americans: How the US Census Classified the Nation (New York, 2017; online edn, Oxford Academic, 20 July 2017), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199917853.003.0001

[47] United States Census Accuracy, FamilySearch, Research Wiki, This page was last edited on 5 December 2022, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/United_States_Census_Accuracy

[48] The following is a transcription of the marriage certificate:

Transcription of Marriage Certificate

[49] There are a number of research sources for German immigrants to the United States in the 1800s. One notable source is:

“Germans to America,” (GTA) compiled and edited by Ira A. Glazier and P. William Filby, is a series of books which indexes passenger arrival records of ships carrying Germans to the U.S. ports of Baltimore, Boston, New Orleans, New York, and Philadelphia. It presently covers the records of over 4 million passengers during the period January 1850 through Jun 1897. Due to its inclusion criteria, this series is considered to be an incomplete—though fairly thorough—index to German passengers arriving in America during this period.

✍ Kimberley Powell, Germans to America, Lists of German Passengers Arriving at U.S. Ports, Thought Co., January 27, 2019, https://www.thoughtco.com/germans-to-america-1421984

Volumes one through 9 of Glazer and Filbys’ the “Germans to America” series indexed only passenger lists of ships that contained at least 80 percent German passengers. Thus, a number of Germans who came over on ships from 1850–1855 were not included.

It is not clear how the data compiled in the Germans to America, 1850–1897 database referenced in footnote 20 below relates directly to the Glazier and Filby published volumes. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) staff have found that there are ship manifests included in the database that are not included in the respective published volumes, and that there is also a difference in the covered time periods.

✍ Supplementary User Note 2, Balch Institute June 2003 Transfer: Germans to America, 1850 – 1897; Italians to America, 1855 – 1900; Russians to America, 1834 – 1897, NN3-CIR-98-001, National Archives and Records Administration, https://aad.archives.gov/aad/content/aad_docs/dmg_cir_immigrant_supp_user_note_2.pdf

Ira Glazier states in his introduction to volume 1, GTA includes only those lists containing a minimum of 80 percent German surnames [note 21].. This requirement in fact consists of two separate criteria: (1) the ethnic affiliation of each passenger as indicated by his/her surname, and (2) the percentage of passengers of a specific ethnic affiliation (viz., German) a ship passenger manifest must contain to qualify for publication.

“(T)o make available the names of approximately 544,000 German immigrants to the United States between the years 1850 and 1855 is an impressive achievement, and certainly those researchers who find the immigration records of their ancestors in GTA will have no reason to fault it. Nevertheless, its size, GTA contains the names of only about three-fourths of the approximately 725,000 Germans who immigrated to the United States between 1850 and 1855, and many researchers will discover to their dismay that their ancestors are among the approximately 181,000 German immigrants during this period whose names do not appear in GTA. In fact, records of many of these German immigrants do exist among the very records utilized by GTA. An objective selection criterion, a more reasonable percent requirement, and expanding the base of potential records to include manifests for ships arriving at miscellaneous ports as well as passenger lists that only survive as microfilm copies would have enabled GTA to capture a significant number of these missing names.”

See: Michel P. Palmer, Published Passenger Lists: A Review of German Immigrants and Germans to America, Volumes 1-9 (1850-1855),26-Jul-1996, http://robertlamping.com/genea/branches/gta-revu.htm An earlier version of this article was published in German Genealogical Society of America Bulletin, vol. 4, No. 3/4 (May/August 1990), 69, 71-90. https://www.genealogienetz.de/misc/emig/gta-revu6.html

Below is a list of indexes and finding aids for New York passenger lists for 1820 to the 1890s.

- New York Passenger Lists Online Index and Images, 1820-1957 at Ancestry/requires payment; includes digitized images of the passenger lists from the National Archives microfilm; covers the Castle Garden, Barge Office and Ellis Island years

- New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1891 at FamilySearch (free with registration) includes index and images of the passenger lists

- New York, New York, Index to Passenger Lists, 1820-1846 at FamilySearch (free with registration) index only

- New York, New York, Index to Passengers Lists of Vessels, 1897-1902 at FamilySearch (free with registration) index only

- Germans to America, 1850-1897 (books and online database)

- Germans to America, 1840-1849 (books)

- German Immigrants: Lists of Passengers Bound from Bremen to New York 1847-1871 (books – these do not include every ship, only a small percentage)

- ISTG Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild LLC, Passenger Manifest Lists and Other

- Edited by Ira A. Glazier and P. William Filby, authors: Glazier, Ira A. (Main Author), Filby, P. William (Percy William), 1911-2002 (Added Author). Germans to America : lists of passengers arriving at U.S. ports, Wilmington, [Delaware] : Scholarly Resources Inc., 1988-2002

- Edited by Ira A. Glazier, Germans to America – series II : lists of passengers arriving at U.S. ports in the 1840s, Lanham, Maryland : Scarecrow Press, c2004

- Gary J. Zimmerman and Marion Wolfert, German immigrants : lists of passengers bound from Bremen to New York, with places of origin, Baltimore, Maryland : Genealogical Publishing Company, 1985-1993

- ISTG Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild , Ships Manifests Departing from Germany, Ports of departure include: Altona, Bremen, Bremerhaven, Cuxhaven, Geestemunde, Hamburg, Stettin, Swinemunde (currently Swinoujscie, Poland), German Unspecified Ports, https://immigrantships.net/bremenproj/bremenproject.html

[50] I have researched a number of microfiche copies of original ship manifests for Johan Wolfgang Sperber, some of which are listed below.