The Sperber branch of the Griffis Family is the ‘most recent branch’ of the family tree to arrive in the United States. The Speber family is the maternal branch of Harold Griffis‘ family. Harold’s mother was Ida Sperber. Her father was John Wolfgang Sperber.

Between 1853 and 1954, there were four generations of the Sperbers in America. The last namesake of the family, Ida Mae Speber, the mother of Harold Griffis, died in 1954.

Ida Speber’s mother’s family, the Fliegel family, also immigrated from Germany at the same time. Descendants of the Fliegel family continue to exist into the 21st century. [1]

The story of the two families and their decisions to migrate to the United States reflects the influence of push and pull factors that affected the larger migratory patterns of Germans to the United States in the late 1840’s through the mid 1850’s.

| Date of Immigration | Harold Griffis’ Maternal Ancestors |

|---|---|

| 1848 | Catherine Fliegel & her husband Henry Krause were the first to arrive in the United States |

| 1852 | John Wolfgang Sperber arrived as a single male in the United States |

| 1855 | The remainder of the Fliegel family immigrated to the United States |

This story is the first part of a series of stories related to the Fliegel and Sperber Families. I have provided the social and historical context in which members of these two families immigrated to America and established families.

This story focuses on Catherine Fliegel’s journey to America, her starting a family and the legacy she left as reflected in subsequent generations of her family. She was the first of the two families to arrive in the United States. Subsequent stories focus on her parents and siblings immigrating to the United States.

See the story “A German Influence” for more high level narrative on the immigration of the Speber, Fliegel, Hartom and other Germanic family branches to the United States

At times I marvel at the ability to actually find historical information and documentation on a relative. It is amazing records have been kept for so many years and not destroyed or misplaced. It is amazing a knock on the door of a house by a census enumerator is answered and an individual who provides reliable information about the household inhabitants. There are times, however, where questions about ancestors remain unanswered .

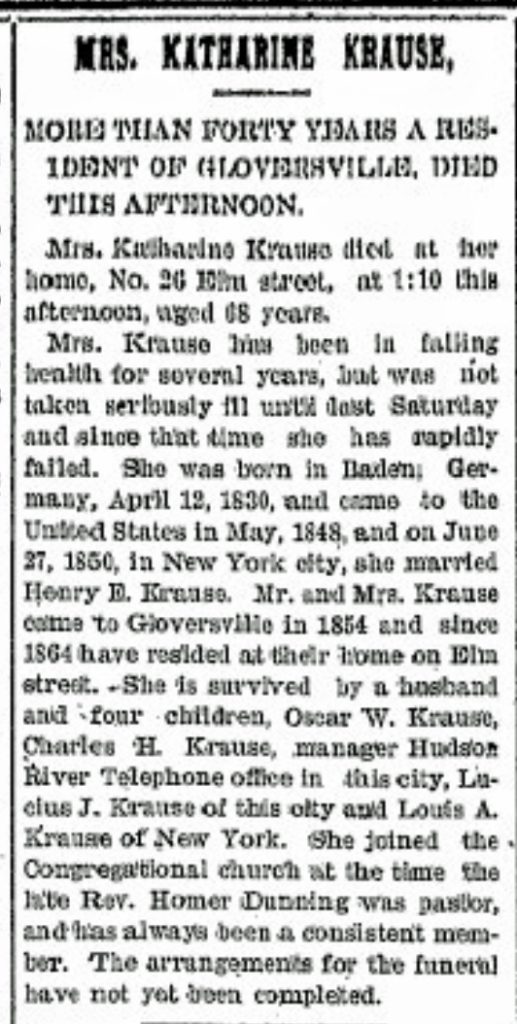

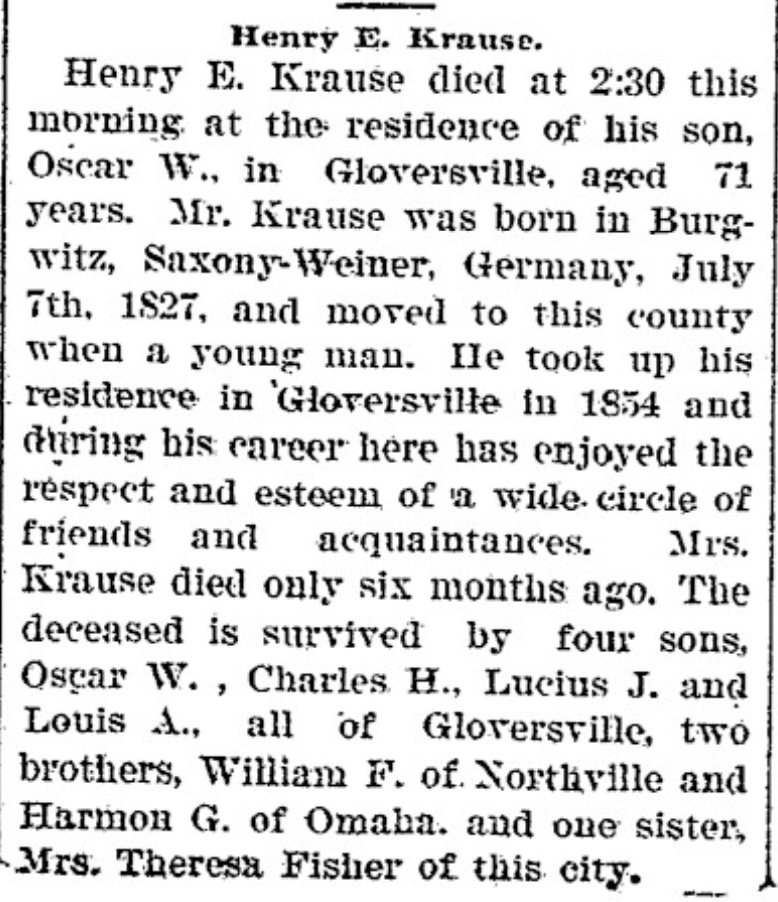

There are definitely gaps in documenting life story facts for Catherine Fleigel. However, Catherine or Katharine (Fliegel) Krause’s death announcement in a Gloversville, New York newspaper provides a wealth of information or promising leads regarding reported dates surrounding her birth, immigration to the United States, her marriage to Henry Krause and her children. The dates for some of these events are not entirely accurate nor are they corroborated by other sources. [2]

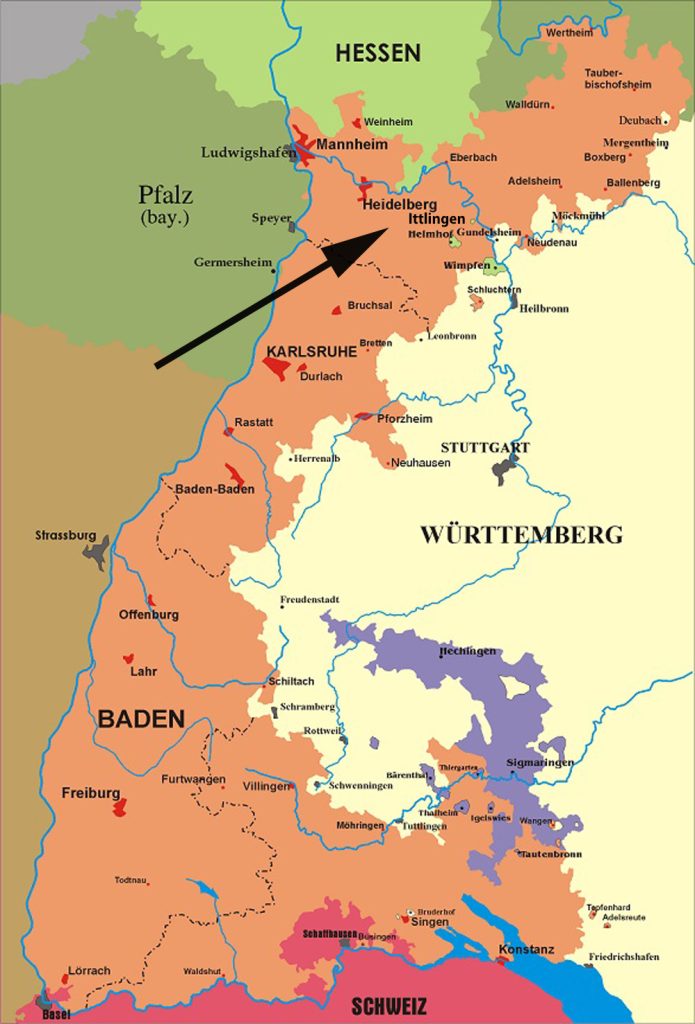

The death announcement indicates that Katherine Krause died at her home on 26 Elm Street, Gloversville, New York in the afternoon on January, 27, 1898. She was born in Baden, Germany, reportedly on April 12, 1930. Katharine came to the United States in May 1848. She married Henry E (Edward) Krause on June 27, 1850 in New York City. Henry and Katharine moved to Gloversville in 1854. They reportedly lived at 26 Elm Street since 1864. She was survived by her four children Oscar W. Krause, Charles H. Krause, Lucius J. Krause and Louis A. Krause.

Katherine (Sperber) Krause Death Announcement

This newspaper article provided a good start on piecing Katharine’s story together. Coupled with other information related to her brother, sisters and parents who also immigrated from Baden, Germany, a big question that surfaces is why a young lady at the age of 19 or 20 would leave her family for the United States. Subsequent questions are how and why did the remaining Fleigel family members follow Katharine to Gloversville.

Germans Immigrating to the United States between 1845 and 1855

The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 took a toll on Germany’s economy. [3] The two decades after the wars produced a combination of war debt, it created social structural and economic turbulence from the imperial occupation of the French, a drain on natural resources, trade crises and agriculture disaster. All of these factors led thousands of individuals from Baden and Württemberg to emigrate to America in the 1840s and 1850s. [4]

“After the end of the Napoleonic wars there was a burst of emigration, as the combination of trade crisis and agricultural disaster sent thousands from Baden and Württemberg onto the roads. While many returned home, about twenty thousand went on to the United States and another fifteen thousand went to Russia. It was noted at the time that artisans (who did not grow their own food) were especially vulnerable to famine and were therefore disproportionately numerous among the emigrants.” [5]

“Germany was in transition during the decade of the 1840s and subject to conflicting forces. The founding of the German Customs Union, which joined Prussia with the larger south German states in a “common market” and the beginning of railway construction in Prussia, Baden, Bavaria, Brunswick, and Saxony, created the essential conditions for economic unification and modern economic growth.

“Industrialization and railroads led to Germany’s first industrial boom, which ended with an agricultural depression … .” [6]

During the 1840s and 1850s, there was a collective feeling of hopelessness in Baden and Württemberg given economic hardships, political upheaval, and natural disasters. A shortage of the potato crop developed in 1842 and grain prices rose as a consequence. Grain prices increased by 250 to 300 percent in two years and potato prices rose 425 percent from 1845-47 [7] Severe weather conditions also contributed to bad harvests, causing food prices to surge. [8] The bankruptcy rate among craftsmen rose from one in 250 in the 1840s to tripling the rate to one in seventy-six in the 1850s. [9]

The scarcity of land in Germany during this time led many farmers to sell their land and immigrate to the United States. Small farmers encountered difficulty providing viable sizes of farmland to transfer to their sons. The Germanic rule of impartible inheritance was modified to include the division of land among all heirs in the Southwestern German states, the Hesse, and the Rhineland. [10]

Map of the Grand Duchy of Baden 1848 (indicating location of Ittlingen)

Source: Störfix, Map of the Grand Duchy of Baden (Germany), from 1819 to 1918, 3 Mar 2006, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_Baden_(1819-1945).png

Revolutions of 1848

Coupled with the economic and agricultural conditions, public unrest began to grow in the face of heavy taxation, political censorship and the growing dissatisfaction among citizens with the monarchies that ran their countries. Activism for liberal reforms spread through many of the German states, which had distinct revolutions. Sympathetic revolutions spread from France across Europe and soon reached Austria and Germany that began with the large demonstrations on March 13, 1848, in Vienna. [11]

The combination of the above mentioned vestiges of the Napoleonic war, trade crises, agriculture disasters, and political unrest led thousands of individuals from Baden and Württemberg to emigrate to the United States.

“1848 is historically famous for the wave of revolutions, a series of widespread struggles for more liberal governments, which broke out from Brazil to Hungary; although most failed in their immediate aims, they significantly altered the political and philosophical landscape and had major ramifications throughout the rest of the century.” [12]

On March 15, 1848, the subjects of Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia vented their political opinions through violent rioting in Berlin. The demands Germany made were for an elected representative government and for unification of all the various political entities in the German region. To preserve their status, the princes and rulers, including Wilhelm, conceded in the demand for reform.

The unrest began to reach Baden, the Speber and Fleigels’ homeland, in the ensuing month. The government began to increase its army and sought assistance from neighboring states. To suppress the revolts, they arrested Joseph Fickler, the leader of the Baden democrats. The arrests resulted in outrage and protests. A full-scale revolt broke out on April 12, 1848. The revolution in Baden was suppressed mainly by Prussian troops. [13]

“During the Revolutions of 1848 in the German states, Baden was a center of revolutionist activities. In 1849, in the course of the Baden Revolution, it was the only German state that became a republic for a short while, under the leadership of Lorenzo Brentano.” [14]

The uprisings in Baden and the Rhenish Palatinate (Pfalz) were in essence part of the same phenomenon, given the nationalist sentiments of the participants, and occurring in adjacent territories along the Rhine.

While the revolt was temporarily suppressed, a resurgence appeared the next year. During the Palatine Uprising in May 1849, provisional governments were declared in both the Palatinate and Baden. While the government was supported by its citizens, the Palatinate army received no aid. The new Palatinate government had no organized state or funding.

The revolution collapsed because of the divisions between the various factions in Frankfurt, the caution for aggressive action of the liberals, the failure of the left to gather popular support, and the superiority of the monarchist forces. When order was restored, the king of Prussia, having refused the title of emperor offered to him by the Frankfurt Assembly, aimed to achieve German unity by the union between the various German princes.

Individuals and families from all over the Germanic region left their homelands. The Rhineland represented the main highway out of Germany to the New World.

“The net loss through emigration was especially large between 1847 and 1855, when crop failure and famine impaired living conditions among a population still mainly agricultural. Political discontent and ferment also quickened the migratory impulse. in the three years, 1853-55, almost half a million people…left Germany annually.“

“In Baden, (an area where the Sperber and Fliegel families lived) despite a large excess of births between 1847 and 1855, emigration caused a continuous decline in population. … . “ [15]

Nearly one million German immigrants entered the United States in the 1850s. This included thousands of refugees from the 1848 revolutions in Europe and the Sperber and Fliegel families.

“For the typical working people in Germany, who were forced to endure land seizures, unemployment, increased competition from British goods, and the repercussions of the failed German Revolution of 1848, the economic and political prospects in the United States seemed bright. It also soon became easier to leave Germany, as restrictions on emigration were eased. As steamships replaced sailing ships, the transatlantic journey became more accessible and more tolerable.” [16]

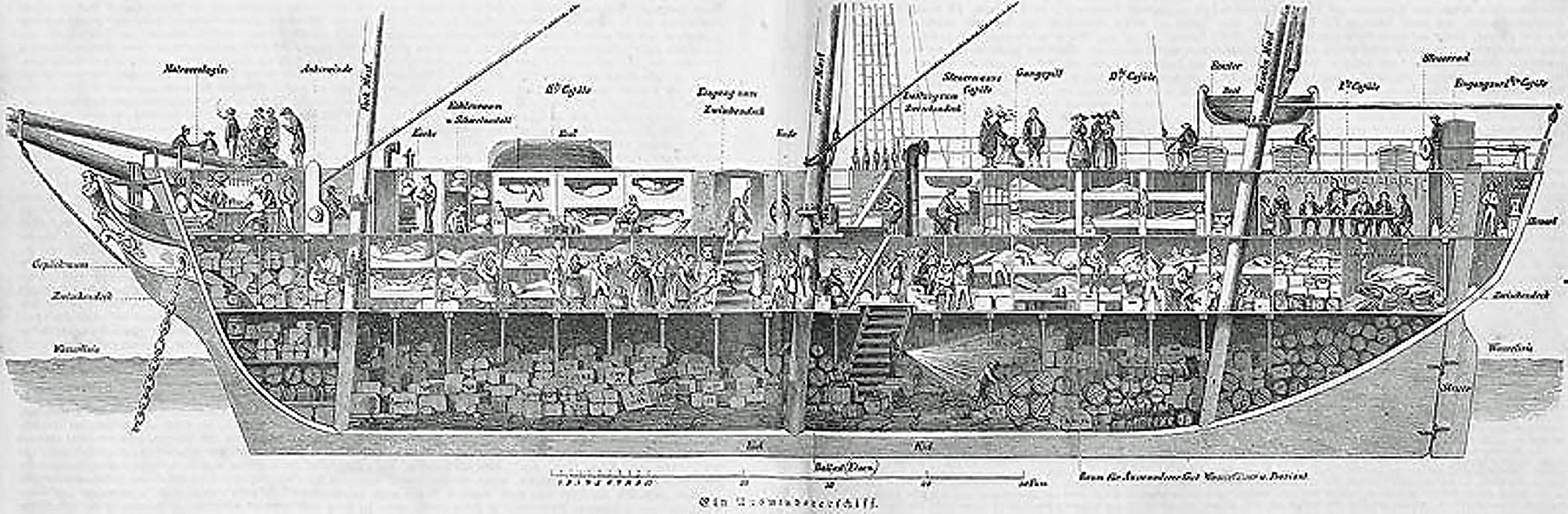

The Initial Journey on Rail and Wagons to Embark on Packet Ships

Most of the immigrants crossed the Atlantic in the steerage area of transatlantic vessels known as packet ships. Conditions varied from ship to ship, but steerage was normally crowded, dark, and damp. [17] While. the trip for immigrants was much shorter than those experienced in the 1700’s, the Atlantic crossing was still fraught with dangers ranging from shipwreck, overcrowded quarters, meager food rations, theft, disease and death.

“Packet Ships were sturdy vessels designed to sail the rough north Atlantic at the cost of speed. They measured about 200 feet long with three masts and a blunt, broad and flat bow. They could travel about 200 miles per day if the conditions were right. Their trans-Atlantic voyages averaged 23 days to go east, and 40 days to go west.” [18]

Getting and navigating to European ports was a challenge for most emigrants, many of whom had never ventured very far from their home village. Advertisements in German newspapers frequently gave information about where where to stay in ports, when the cost of staying in the ports was included in the passage price, and how to survive cheaply before setting sail.

“For an adult traveling in steerage on a sailing ship, the average fare was 33 to 35 (Prussian) Thalers, about 23 dollars. These fares explain why most of the Germans who emigrated were positively self selected, that is, they were not poor farm laborers or servants but were somewhat better off. Around 1850, even a master farm laborer in the Rhine area earned only about 60 Thalers per year in cash in addition lo various in-kind goods, worth probably at least another 20 Thaler.” [19]

The most common destination for German emigrants was New York City. Getting to New York City was expensive for many Germans. Moving to the United States was not a cheap endeavor for Germans during the middle of the nineteenth century. The fares were generally higher from Le Havre, Antwerp, and Rotterdam than from Hamburg or Bremen. The reason is that the listings for the fares from these cities included the cost of getting from a city in the interior of Germany to the port city. For example a listing might be “Koeln – Havre – New York”. [20]

“German emigrants left from different regions of Germany and favored different ports of embarkation. The Dutch ports, important in the eighteenth century, declined in the nineteenth because of high fares and the difficulty of finding return freights. Bremen was accessible to migrants from the northwest via the Weser (River). Hamburg was favorably situated with respect to Prussian provinces east of the Elbe (River), and Le Havre was more accessible to the southwest German regions.” [21]

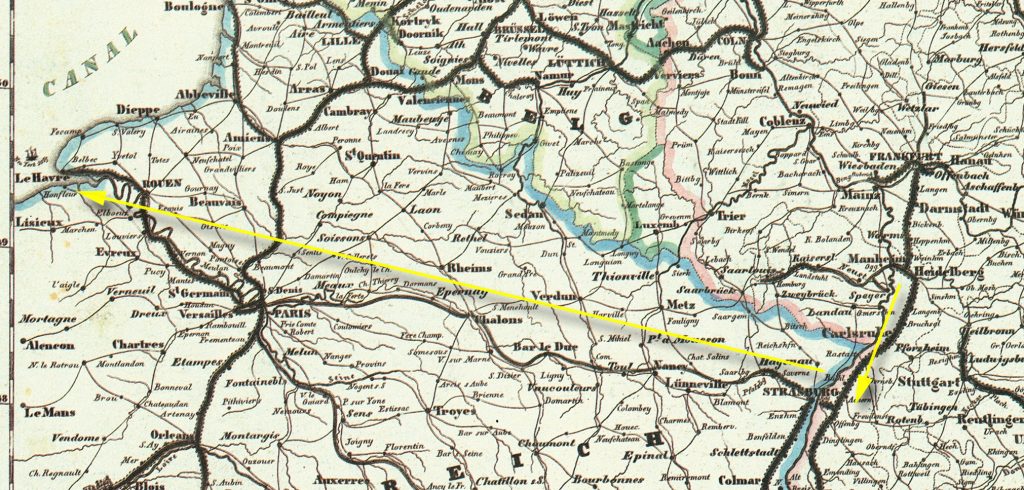

Catherine Fliegel probably traveled from her home of Ittlingen, Baden to the port of Le Havre, France. “From the crossing of the Rhine until the waters of The Atlantic were sighted required a journey of several weeks.” [21a] There is documentation to suggest that her future husband Henry Krause traveled from Hamburg.

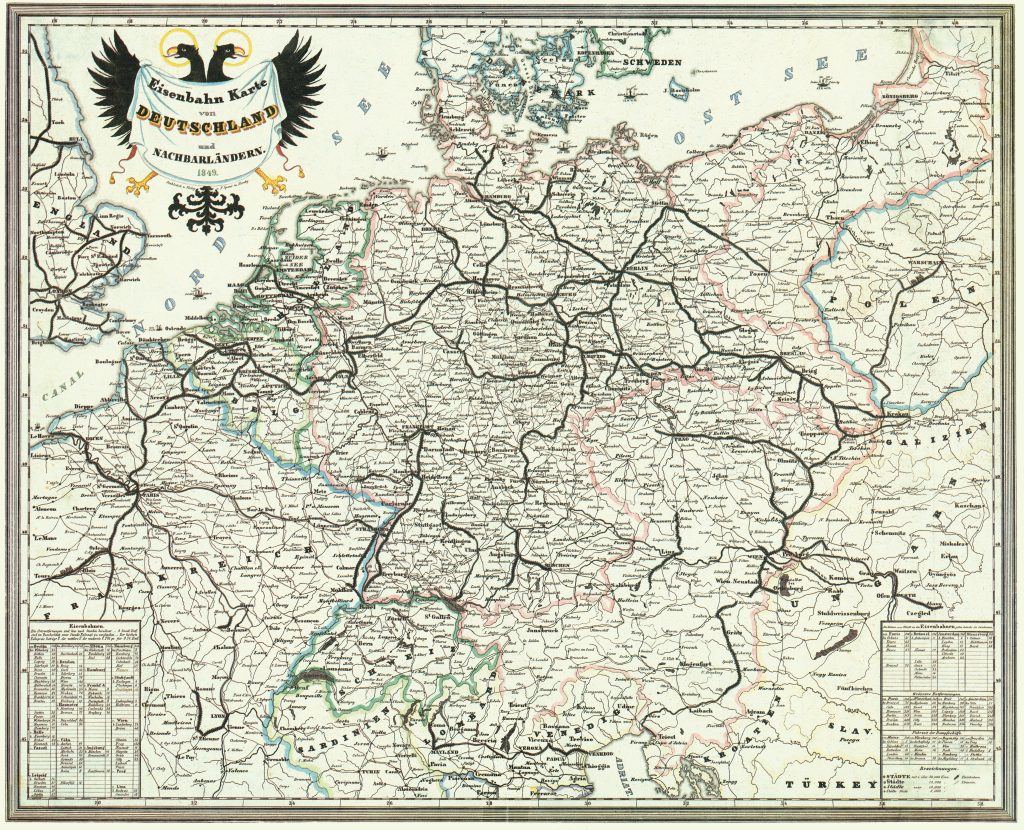

Both probably benefitted from the use of the emerging railways in the three dozen German states. Political disunity among the Germanic states made it difficult to build railways in the 1830s. However, by the 1840s, trunk lines linked the major cities. Each German state was responsible for the lines within its own borders. By the year 1845, there were already more than 2,000 km or about 1,245 miles of railway line across German states. [22]

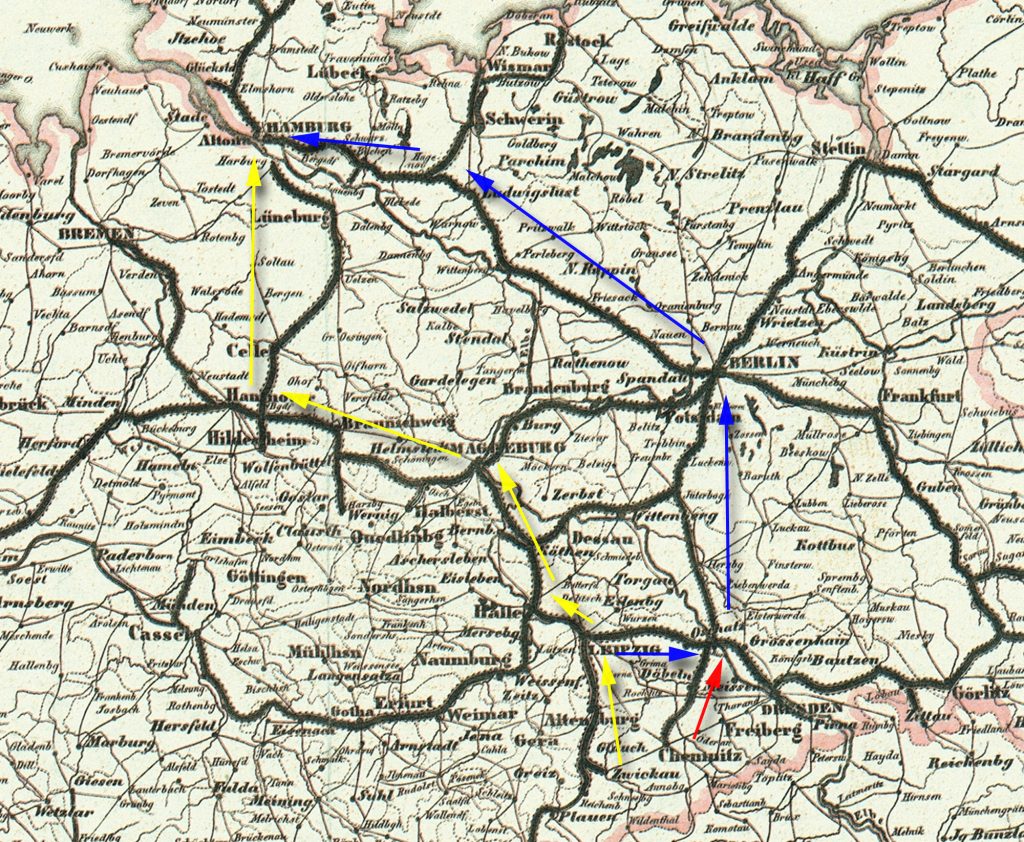

The European Railway Network in 1848 [23]

The development of rail lines in German states in the 1840s facilitated the transportation capabilities for German travel to the ports of Bremen, Hamburg, Antwerp and Amsterdam. To a limited extent, it also provided rail travel for Germans in the southwest to get to Strasbourg, France. The rail lines, however, were not continuous to each of these ports and to other cities within the German states. A close look at the above map will confirm that oftentimes immigrants would need to take wagons to catch another train line.

“Le Havre in the 1840s imported cotton from the American south and sent “passagers d’entrepot” back to the United States. In the early 1840s and 1850s it was the main port for migrants from Baden, Bavaria, and Wurttemberg as well as from Switzerland and Alsace, as it was closer to these regions than German, Belgian, or Dutch ports.”

“Le Havre was the major port for the day-laborers, farmers, merchants, and also iron and textile workers from Mulhouse and Guebwiller. In the 1840s and early 1850s more Germans left for the United States from Le Havre, Rotterdam, Antwerp, London, and Liverpool than from Bremen or Hamburg. ” [23a]

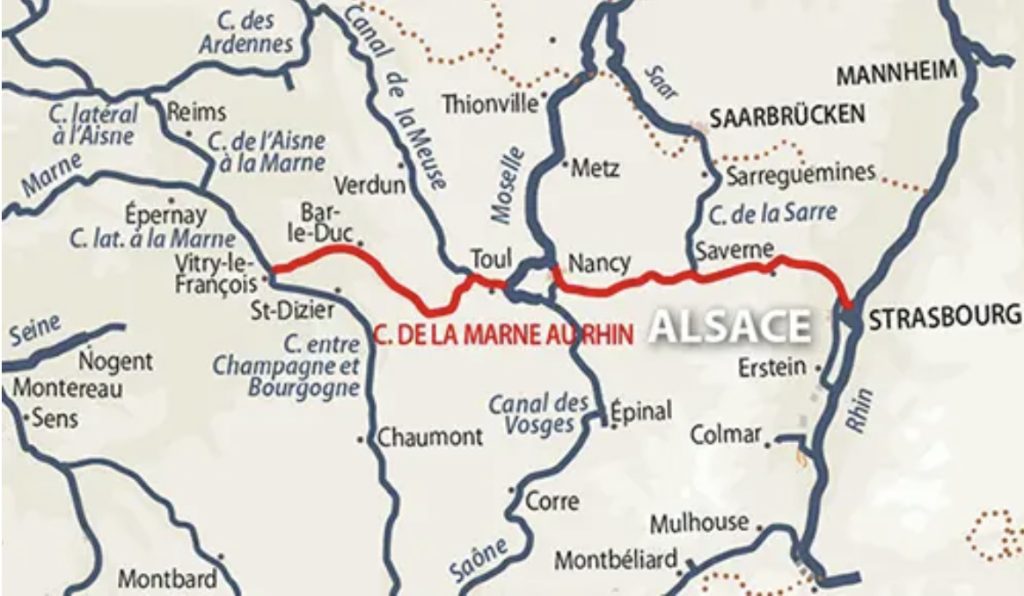

While Le Havre was the most direct access port for Catherine Fliegel in the late 1840’s, the railroad infrastructure in France at the time substantially lagged behind the railway development in the Dutchy of Baden. Consequently, her rail journey was punctuated with travel by wagon or ferry.

“Like most emigrants from their region, they would have started their travel from the German-French border with other families in long caravans of covered wagons. These wagons would probably have been arched with sailcloth and inside would be the women, children, and baggage while the men and older boys would lead the horses by walking outside the wagons. At night they would have probably camped and sparingly consumed the supply of food they brought to support them across the Atlantic. Most would travel by road directly to LeHavre and others may stop in communities along the way where they would rest up in preparation for the long traumatic experience that lay ahead. Once at LeHavre, the reality of what was happening became more certain. Some families may have sold their wagons along the way to obtain extra money for travel expenses and possibly a little start in their new life.” [23b]

The most direct route for Catherine to reach the Port of Le Havre was to:

- Take a wagon or carriage from Itlingen to Heidelberg

- Take the train from Heidelberg south to the rail branch to Kehl which is across the Rhine River from Strausbourg, France.

- A rail bridge between Kehl and Strasbourg was not built until May 1861. She would need to take a ferry and/ or carriage ride to the Strasbourg. [23c]

- From Strasbourg to Paris, Catherine probably required the services of a wagon, perhaps riding with another German family for approximately 310 miles to Paris. [23d]

- Catherine either continued her journey by wagon to Le Havre or used the railway to Rouen and then to Le Havre.

“Freight Wagons returning from Basel and Strasbourg to Le Havre carried passengers will to travel the slow way, while persons with more means forwarded their heavy household belongings by the freighters, and themselves used the more rapid stage lines.” [23e]

“At Paris a wait of ten days or so occurred. … In continuing the journey, the majority embarked upon the steamboats on he Seine, or traveled as deck passengers upon the barges that these steamboats towed to the port. Three times a day stages set out for Le Havre, but such conveyance was usually too expensive. … To be sure, some caravans avoided Paris entirely, traveling by road directly to Le Havre.” [23f]

French Railways 1842 – 1860

Seven years later her family probably took the same route but benefitted from the completion of the rail route between Paris and Strasbourg.

I increased the size of portions of the above map to indicate possible rail routes that Catherine and Henry used to get from their home towns to their respective ports of departure (La Havre and Hamburg)

Rail and Road Routes from Heidelberg to La Havre – Probable Routes of Catherine

Henry Krause may have taken wagon transport either from the Burgwitz to Zwickau (about 55 kilometers) or a 64 kilometer wagon ride from Burgwitz to Chenwitz (to start his train journey to Hamburg. From Zwickau, he had two possible routes. One route went north to Leipzig and continued north to Magdeburg then on to Hanover and Hamburg. The other route continued either from Leipzig and traveled east to Oschatz or started from Chenwitz directly to Oschatz and then to Berlin and Hamburg.

Probable Rail Routes of Henry Krause to Hamburg

The German migration to America has often been characterized as a family migration pattern, one in which entire families moved together to the the United States, including older parents traveling along with several grown or nearly grown children. [24] This is an accurate depiction of the remaining Fliegel family who came to the United States in 1855 (more on that in a later story).

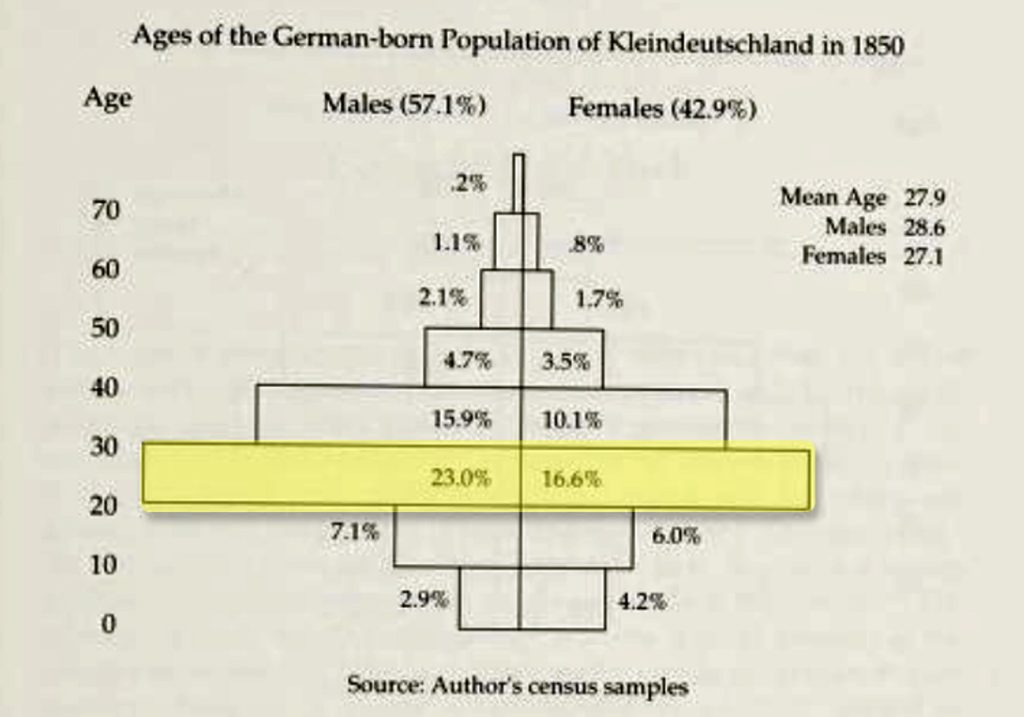

However, the demography of the New York immigrants in the late 1840’s and early 1850’s provides a very different picture. In 1850, 66 percent of the German immigrants were in their twenties and thirties, as reflected in the distribution chart below. In addition, the ratio was 61:39 (male:female) in 1850, indicating a heavy predominance of single males. [25]

Both Henry and Catherine were single and were in their early 20’s when they can to the United States.

Catherine Fliegel Arriving in New York City

There were strong push factors for Johan Wolfgang Sperber and the Fliegel family to immigrate from Baden to the United States. Catherine Fliegel, born April 12, 1829 [26], a future sister-in-law to John Wolfgang Sperber, left just prior to the eruption of the 1848 revolution in her homeland of Baden.

We do not know why, as a young lady at the age of 19 or 20, she traveled alone and would leave her family and homeland for America. However, she was not the exception. Both the life experiences of Catherine and her future husband Henry were examples of larger demographic migratory trends of young Germans migrating in the 1840s and 1850s.

“(D)ifferent streams of migration followed channels established by early immigrants as they flowed into the labor pools of America. Social networks of information, contacts, and kinship guided each migrant’s choice of a place to settle. People tended to settle in groups: national, regional, and local. On these bases, they chose one city over another, one neighborhood over another, one block or street or house over another…. .

“Within the constraints established by the labor market, immigrants frequently chose to live among kin, fellow townsmen, fellow provincials, or fellow nationals whenever possible. This preference, in turn, influenced the nature and structure of the settlements of German immigrants in the United States.” [27]

Based on information in her obituary, Catherine Fliegel purportedly arrived in New York City in May 1848. A review of various ship manifest sources however have no lead me to solid leads on which ship she sailed on to the United States. It is highly probably she sailed on a packet ship from Le Havre. [27a]

It is not known what Catherine did while she lived in New York City or where she lived in New York City for seven years. She is not found in the 1850 U.S. Federal Census in New York City.

Within two years of her arrival, she married Henry Edward Krause who was from the Kingdom of Saxony. They purportedly married on June 27, 1850, in New York City. It is likely but not certain that they were married in one of the German Lutheran churches in Little Germany. [28]

Henry Edward Krause Immigrating from the Kingdom of Saxony

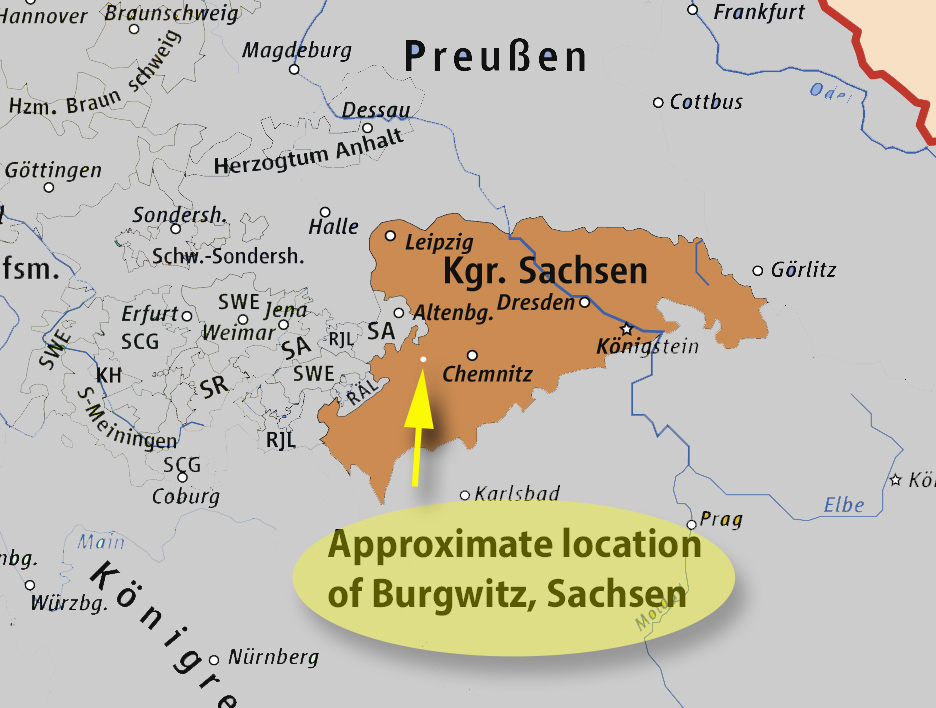

Henry Edward Krause was born in July 7, 1827 in Burgwitz, Sachsen or Saxony. Not much is known about Henry’s parents or ancestors. [29] Similar to many of the kingdoms and principalities of Germany, Saxony has a rich history of changes in its boundaries and rulers. Saxony has a long history as a duchy, an electorate of the Holy Roman Empire, and finally as a kingdom. Henry’s home town of Burgwitz is about 70 kilometers west of Chemnitz, Saxony.

Burgwitz in Context of the Kingdom of Saxony

Napoleon conquered Saxony in 1806 and made it a kingdom. It was one of his most loyal allies. After Napoleon’s overthrow, its territory was greatly reduced by the Congress of Vienna (1814–15). Prussia acquired Wittenberg, Torgau, northern Thuringia, and most of Lusatia, which became the Prussian province of Saxony; the truncated kingdom of Saxony became a member of the German Confederation, Der Deutsche Bund. [30]

Kingdom of Saxony – Part of the German Confederation 1815 – 1866 [31]

In the 1830s to 1840s, Saxony was one of the centers of non-guild artisan production, particularly in textiles. They initially lost ground in world markets during the disorders of the Napoleonic period. When peace returned, they attempted to continue to compete on the basis of hand production.[32]

Several factors led to the decline of linen and in general textile manufacturing in Saxony and their close neighbors to the east: Silesia. The demand for textile products dropped as it faced increased competition from the development of linen industries in Ireland and Scotland. English cotton also became a popular and cheap alternative to linen products. German producers found it increasingly difficult to compete with the mechanized factory production systems in the British textile industry. The innovations associated with the textile work processes, such as the power loom and moving the work process to centralized factories were still rare in German areas.

The persistence of ”feudal’ social and economic arrangements prevented the development of more efficient systems of production. Domestic weavers, who bought the raw materials from merchants and sold back the finished product back to merchants, generally worked in their homes or in small workshops. The export of German textiles declined rapidly in the 1830s and 1840s, and the economy of the region stagnated.

This competition with the newly mechanized British textile industry led to a steady degradation of the German artisans’ standard of living. As the merchants had a monopoly on access to the markets for the weavers’ work, the weavers had no choice but to accept the prices that they were offered. The weavers also had the additional economic pressure of feudal obligations, being still forced to pay seignorial dues in many places. Some weavers were forced into debt, having to borrow money in order to buy the raw materials with which they worked. These economic conditions led to periodic local uprisings.

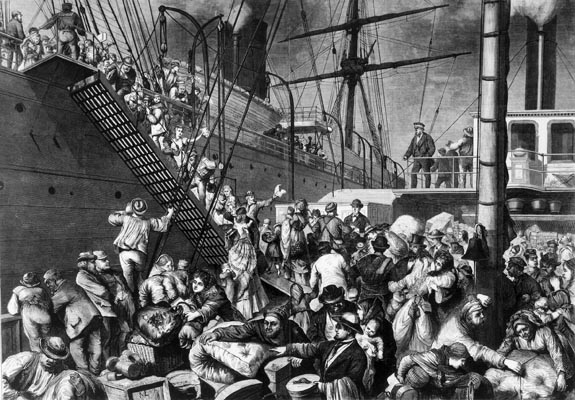

German emigrants headed for New York board a steamer in Hamburg

Coupled with the stagnation of the textile economy in Saxony, similar to the Baden area where Catherine was from, small farmers were also experiencing the brunt of economic impacts. In addition, a severe famine occurred. in 1847. During the 1848–49, constitutionalist revolutions in Germany, Saxony became a hotbed of revolutionaries, in 1849. [33]

For those with resources, immigration to America was a popular option during this period. Henry Edward Krause’s actions to immigrate to the United States in 1848 were undoubtedly influenced by all of these ‘push’ factors.

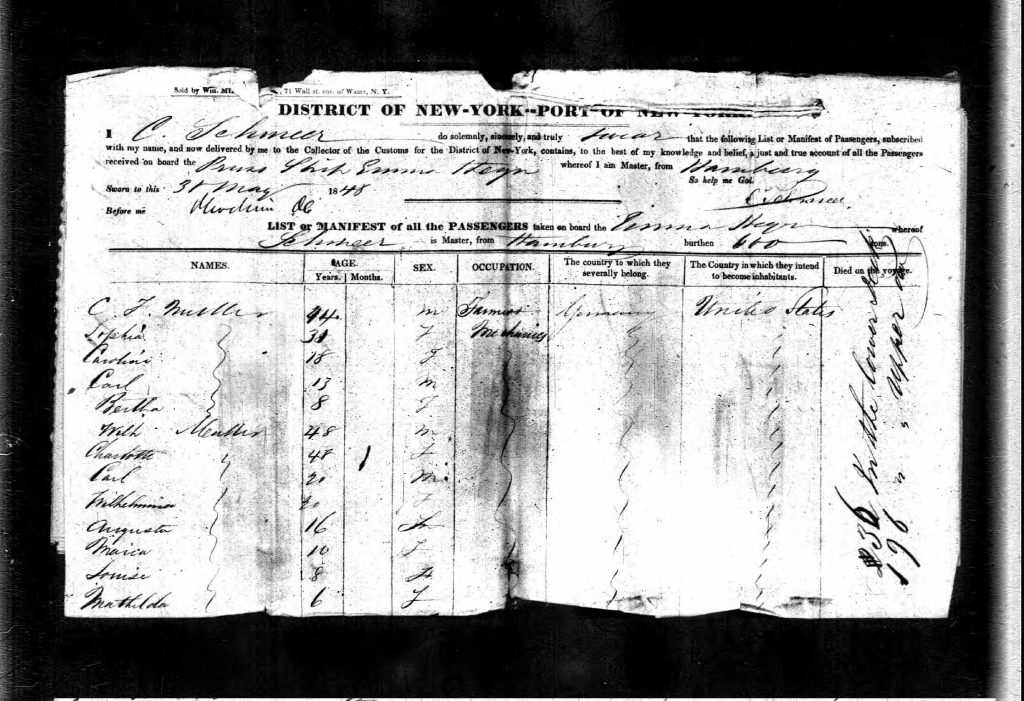

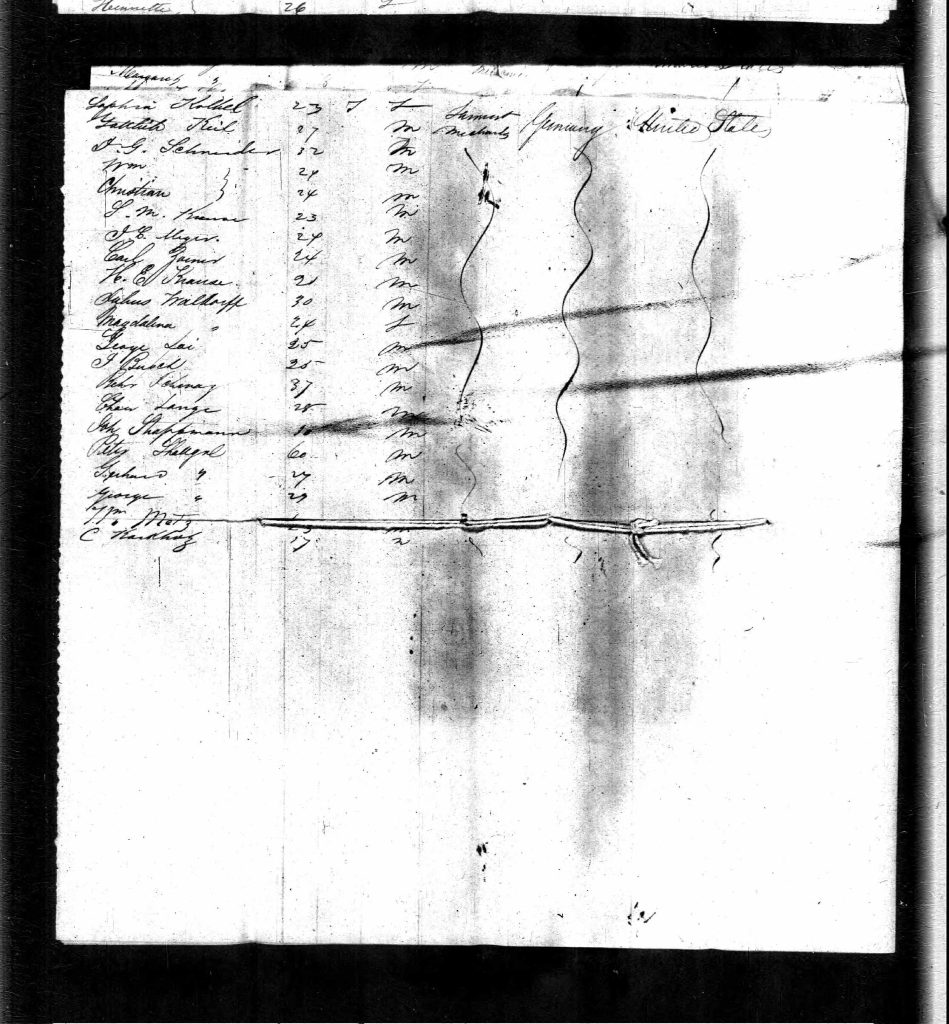

Ship manifest records suggest that Henry Krause, “H.E. Krause”, arrived in New York City on May 31, 1848 from Hamburg, Germany on the Ship Emma Heyn. [34]

Passenger and Crew List of Ship Emma Heyn, Page One

Passenger and Crew List of Ship Emma Heyn, Page 7 Line 9: “H.E. Krause age 21”

Kleindeutschland (Little Germany) in New York City

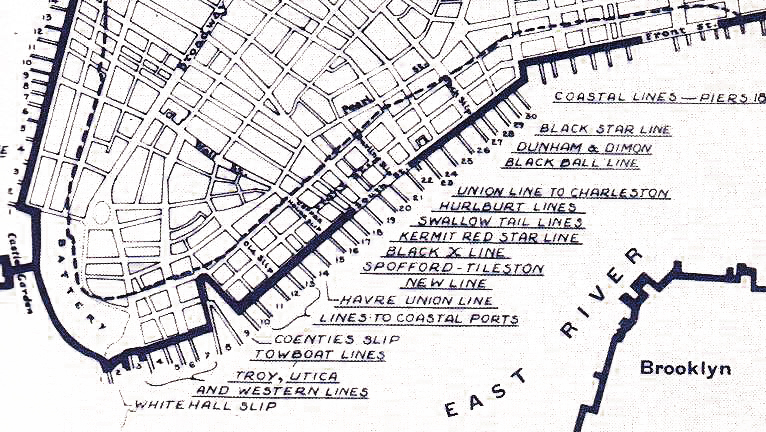

Depending on what shipping line Catherine and Henry used to come to the United States, they would have walked off their ship onto one of the piers on lower Manhattan on the East River. Catherine’s family, who arrived seven years later, arrived on the Havre Union Line on pier 14.

Pier 14 Port of New York, New York City 1851

Catherine and Henry spent seven years in New York City after their arrival to the United States.

Many of the German immigrants who came during this time period, notably those who landed in New York City, settled down to live their lives on the Lower East Side of New York City. Other German immigrants used this geographical ethnic enclave as a launching to find a spouse, establish networks and gain information and resources to make plans to travel further west into the United States.

Kleindeutschland was only a short distance from the piers where the packet ships arrived from the European ports. In the mid 1800’s, this area of New York City could more appropriately have been called the “Upper East Side,” since it was the northern edge of the developed area of eastern Manhattan Island.

Beginning in the 1840s, large numbers of German immigrants entering the United States provided a constant population influx for “Little Germany”. For many Germans, perhaps true for Catherine Fliegel, it must have been an eye opener to arrive in the United States and to see and experience a small urban area so densely packed with German people, Germanic culture and neighborhood communities similar to “home”.

The following presentation by Richard Haberstroh provides a detailed history of the development of the Kleindeutchland in New York City within the larger context of nineteenth century immigration. Various aspects of the social and day-to-day life in the German community are also provided.

In 1845, Little Germany was already the largest German-American neighborhood in New York. By 1855, its German population had more than quadrupled, displacing the American-born workers who had first moved into the neighborhood’s new housing. By 1855 New York had the third largest German population of any city in the world, out ranked only by Berlin and Vienna. [35]

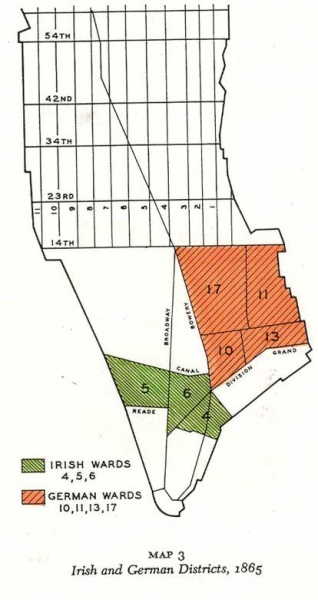

“The entire area reaching roughly from Division Street in the south to 14th Street in the north, and from the Bowery in the west to Avenue D in the east became a thriving center of German-American life and culture in the mid- to late 19th century – not only for New York City, but also for the country.” [36]

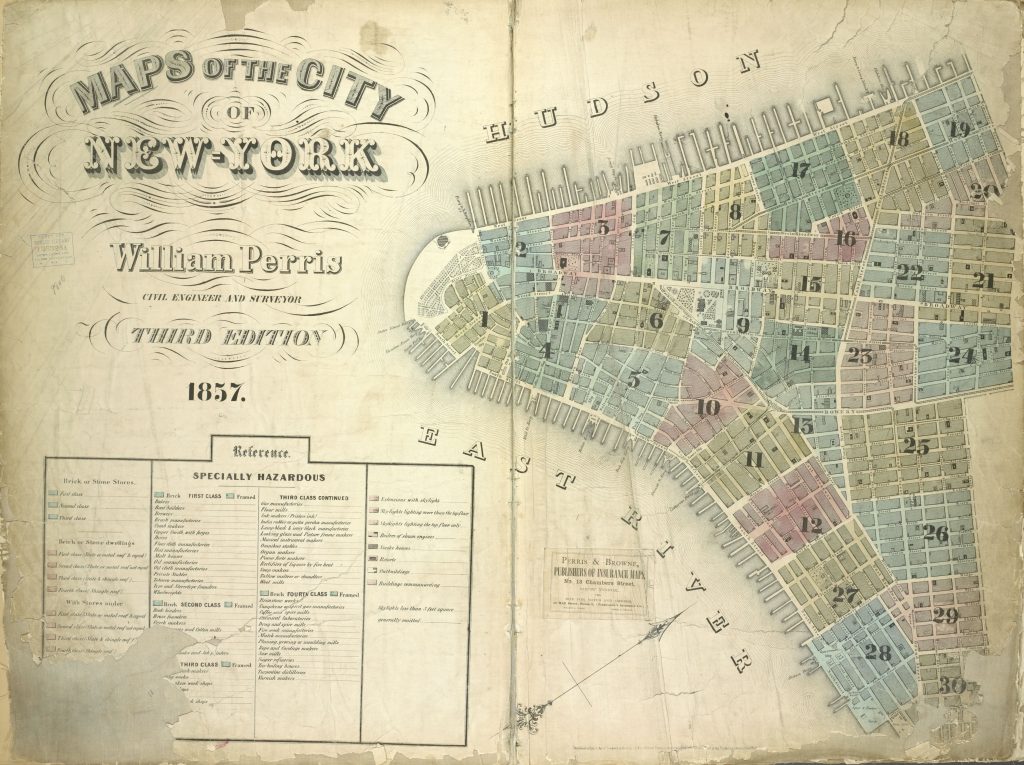

Orange Sections Represent New York Wards Where German Immigrants Lived [37]

The Kleindeutschland encompassed the 10th, 11th, 13th and 17th Wards of New York City – an area between 14th and Division Streets, the East River and the Bowery. Today this area includes the East Village, Alphabet City, and parts of Chinatown, the Bowery, Little Italy, and NoLita. [38]

The Germans who lived in this part of New York City maintained their language and culture. The “Germans” who came to America in the 1800s tended to form communities within their own regional groups. Badens, Bavarians and Prussians were prominent among the German speaking groups who settled in New York City. [39]

Germans tended to cluster in city wards based on their origin in Germany, more than other immigrants, such as the Irish, during this time period. Those from particular German states preferred to live together. This choice of living in wards with those from the same Germanic region was perhaps the most distinct feature of Kleindeutschland. [40]

The immigrants from Baden and Württemberg seem to have been fairly evenly spread throughout the four wards in the earlier years, with no major concentrations. [41]

The Prussians, for example, were most heavily concentrated in the city’s Tenth Ward. Germans from Hessen-Nassau area were predominantly found in the Thirteenth Ward in the 1860s. The Bavarians (including Palatines from the Palatinate region of western Germany on the Rhine River), were the largest group of German immigrants in the city by 1860 and were distributed evenly in each German wards except for the Tenth Ward.

Aside from the small group of Hanoverians, who had a strong sense of self-segregation forming their own “Little Hanover” in the Thirteenth Ward, the Bavarians displayed the strongest regional bias mainly toward the Prussians. At all times during this period, the Bavarians would be found wherever the Prussians were fewest [42]

“The German-Americans of New York City were broadly representative of the German immigration as a whole, or at least its urban component. The early settlers were from the west and south, Rhineland Germany, and even as late as 1863 it was possible to report that north-Germans are less frequently encountered than south-Germans. The leading contingents are from the Hesses, Baden, Württemberg and Rhenish Bavaria. One hears all dialects, but Berliner, Saxon and Westphalian are rare while Swabian and Upper-Rhenish modes of speech predominate.” [43]

Maps of the City of New York 1857

Click for larger View

Moving to the Johnstown – Gloversville Area

In 1854, the couple moved to Gloversville, New York. Perhaps her positive experiences in the new land were conveyed in letters to her family in Baden, similar to what many other German immigrants did after migrating to the United States. [44] Seven years later, in 1855, the rest of her family made the decision to follow.

“From (1830) … until World War I, almost 90 percent of all German emigrants chose the United States as their destination. Once established in their new home, these settlers wrote to family and friends in Europe describing the opportunities available in the U.S. These letters were circulated in German newspapers and books, prompting “chain migrations.” By 1832, more than 10,000 immigrants arrived in the U.S. from Germany. By 1854, that number had jumped to nearly 200,000 immigrants.” [45]

After the Civil War, the glove industry boomed in the Johnstown and Gloversville, New York area, causing large numbers of immigrants from many of Europe’s glove making centers to make their new homes there.

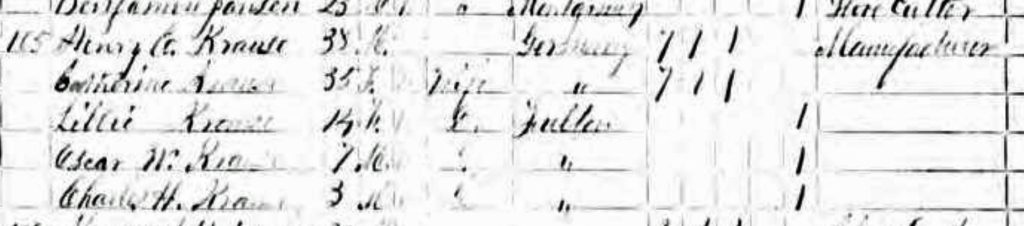

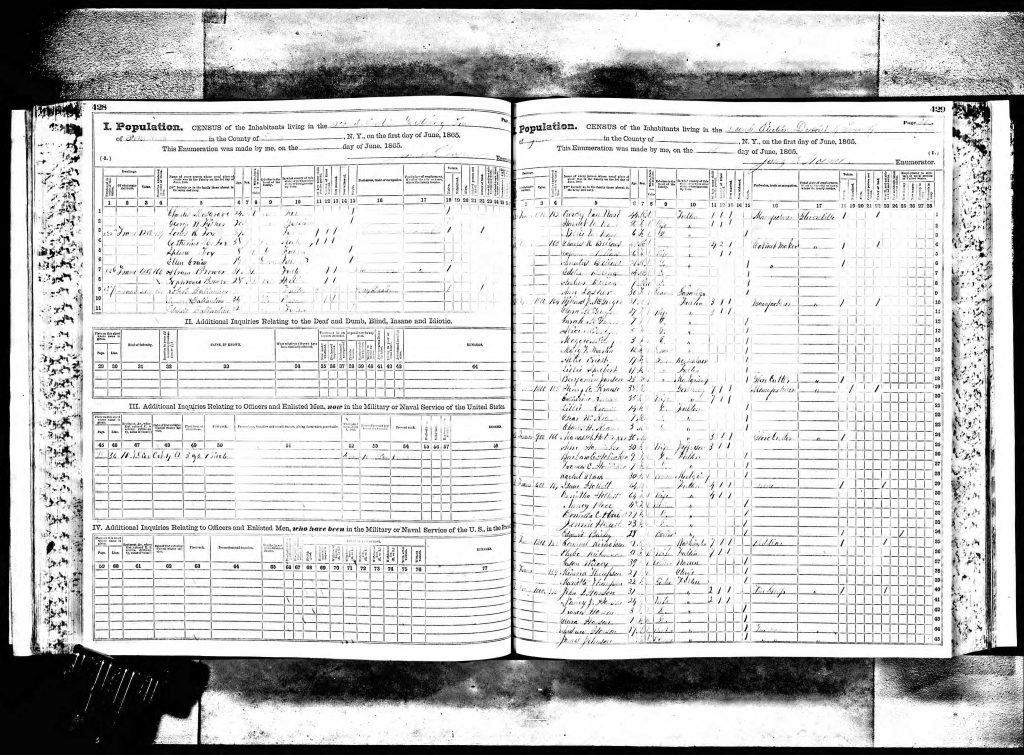

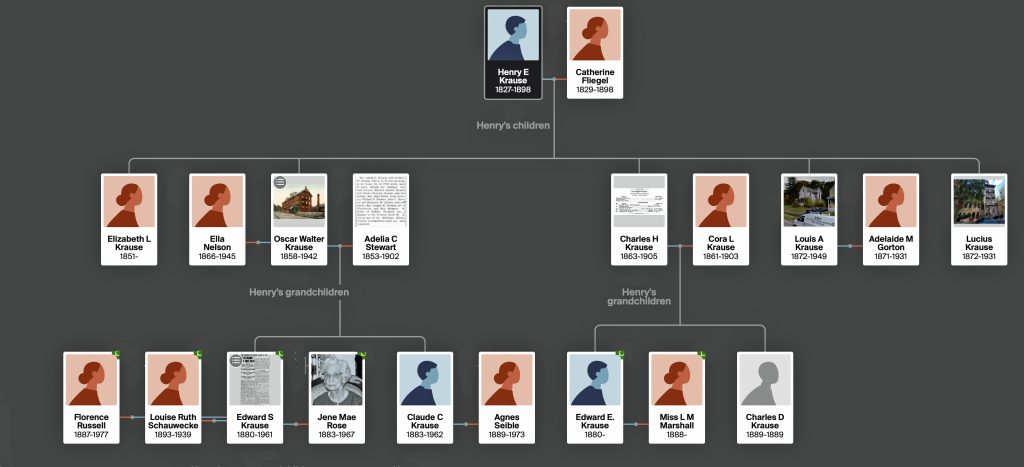

Henry and Catherine (Fliegel) Krause came to the Johnstown area, as indicated, prior to the rest of the Fliegel family. Their first child Elizabeth was born in 1851 while they lived in Little Germany in New York City. They then moved to Johnstown in 1855. Their second child Oscar was born in 1858 and their third child Charles was born in 1862. Their presence is not documented in the 1860 United States Federal Census. They are listed in the 1865 New York State census. [46]

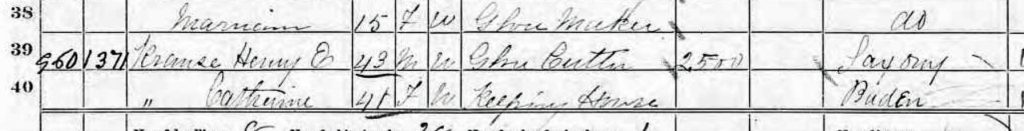

In the New York state census for 1865, the Krause family had one teenaged daughter and two young sons. Lillie was 14 years old, Oscar was 7 years old and Charles H. was 3 years old. In 1870, Henry was reported as 38 years old, his occupation is listed as “Manufacturer” and Catherine was 35 years old

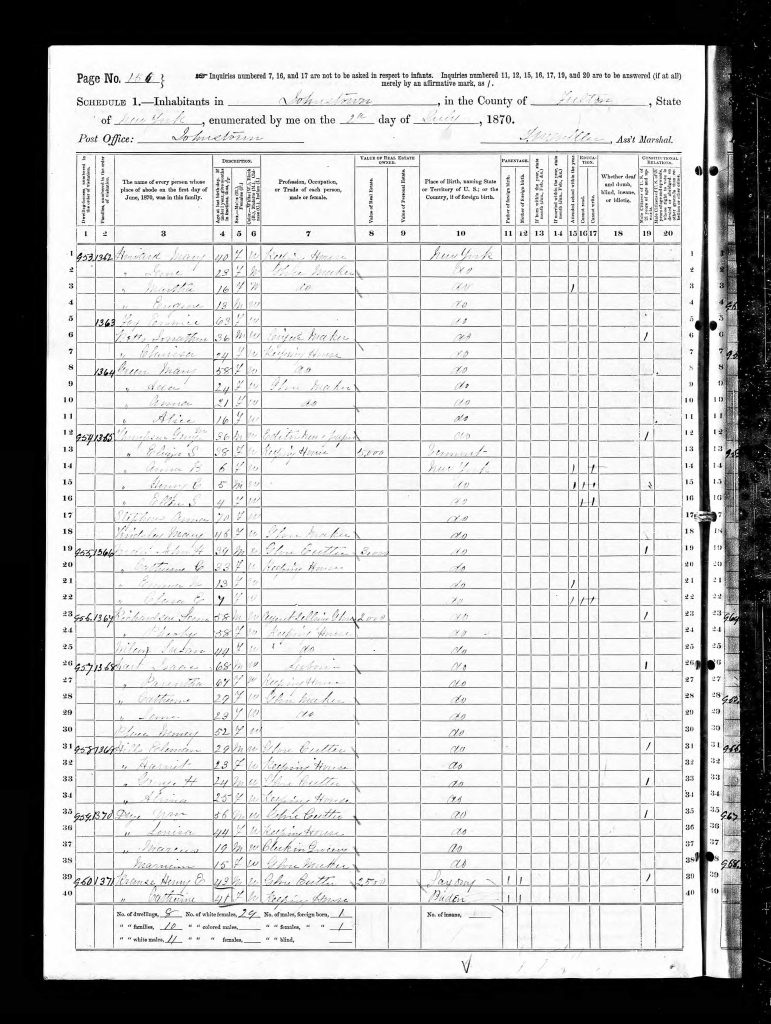

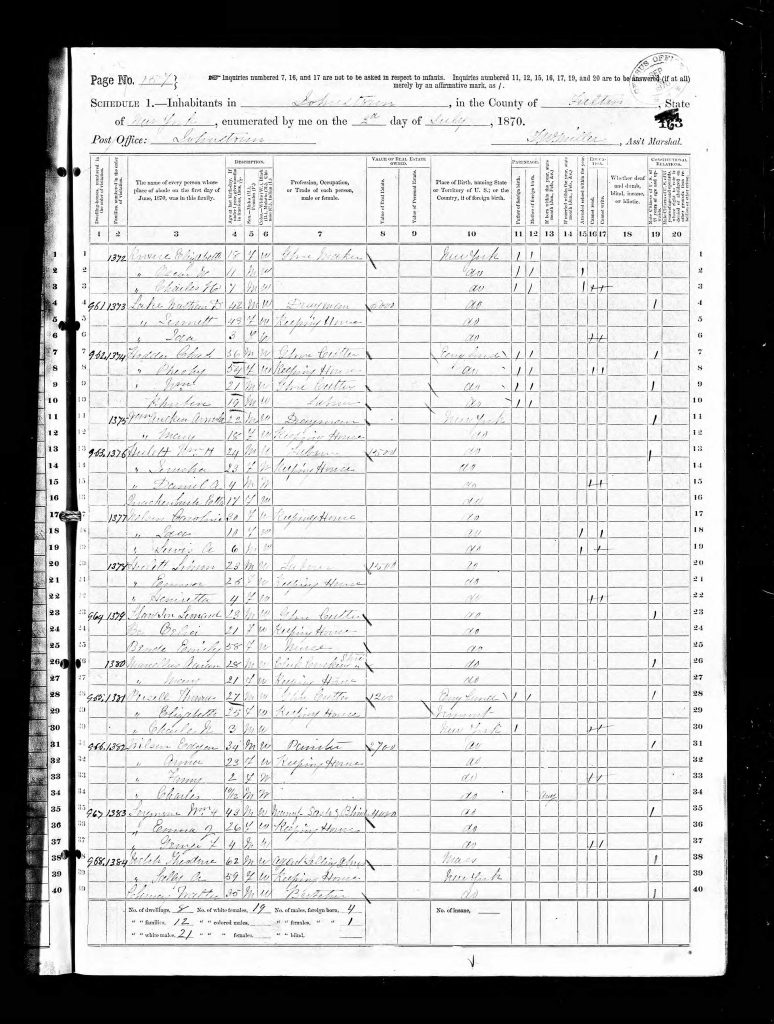

Krause Household, 1865 N.Y. State Census – Johnstown, N.Y.

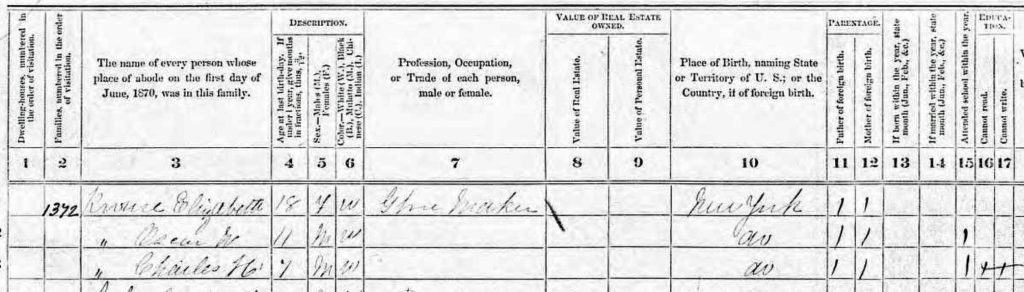

In July 1870 Federal Census, the Krause family is living in Johnstown, New York. Henry Krause (age listed as 43) and indicated his occupation as a glover cutter. Catherine (age 41) is keeping house. Lillie (Elizabeth) is 18, working as a glover maker and living with her parents. Oscar (age 11) and Charles (age 7) are in school. The parents are found on the bottom of one census page and the children are listed on the following census page. [47]

Krause Household, 1870 Federal Census – Johnstown, N.Y.

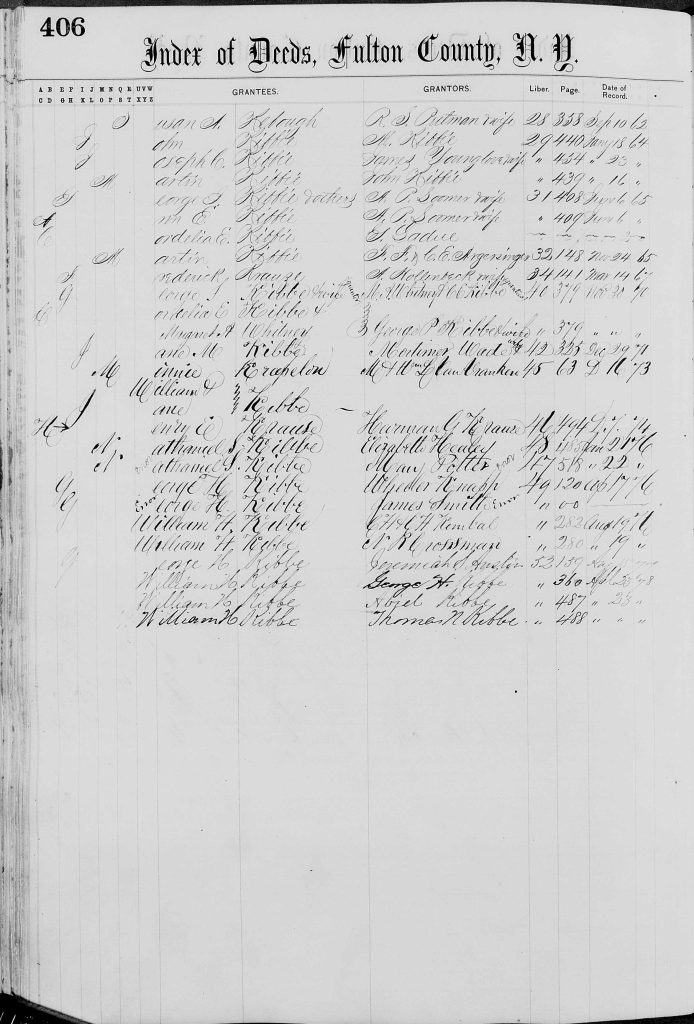

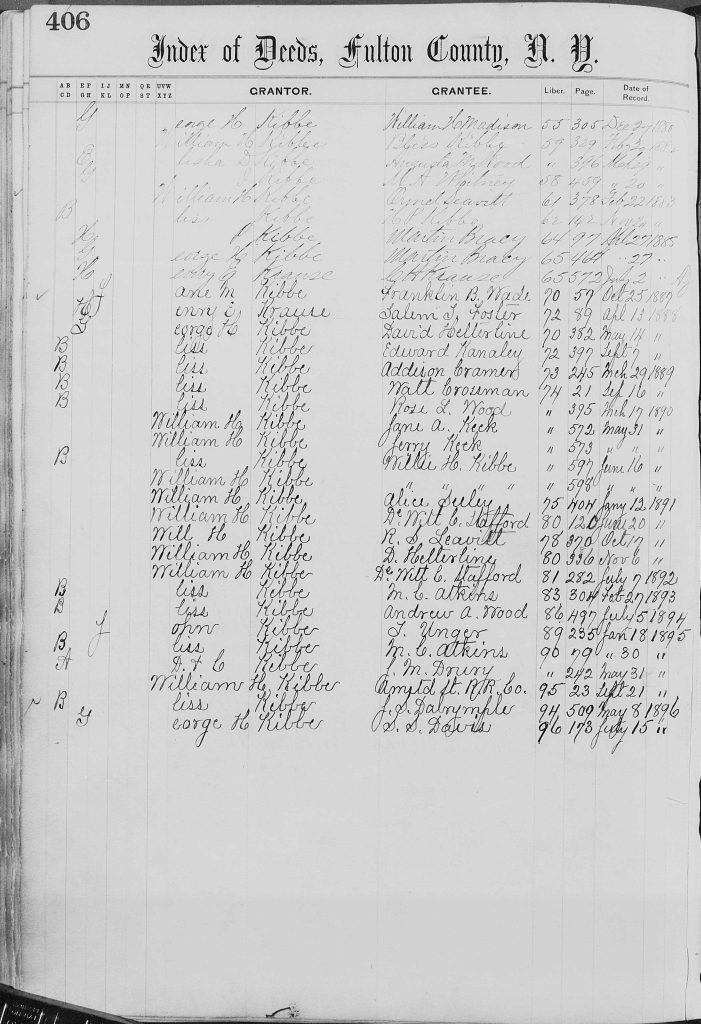

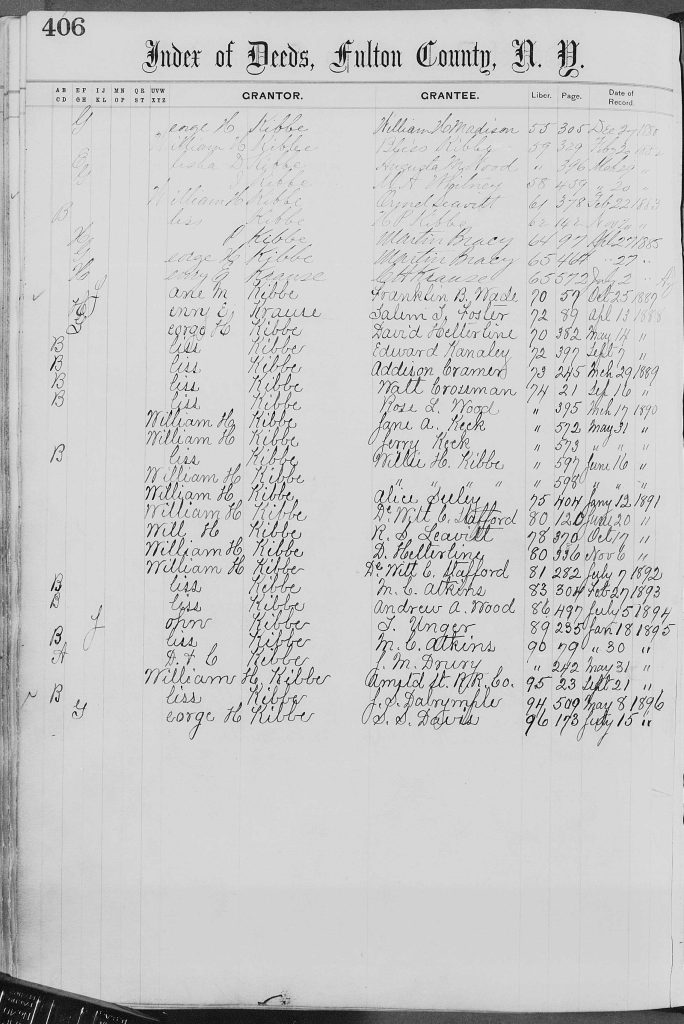

Based on the index of deeds for Fulton County, in 1874 the Krause family purchased a house in Gloversville, New York. [48] Since the source of the transaction is only an index, it is not known exactly where the house was located. However, if we rely on the obituary of Catherine (Katherine) Fliegel Krause, we can plausibly assume the property was located at 26 Elm Street, Gloversville.

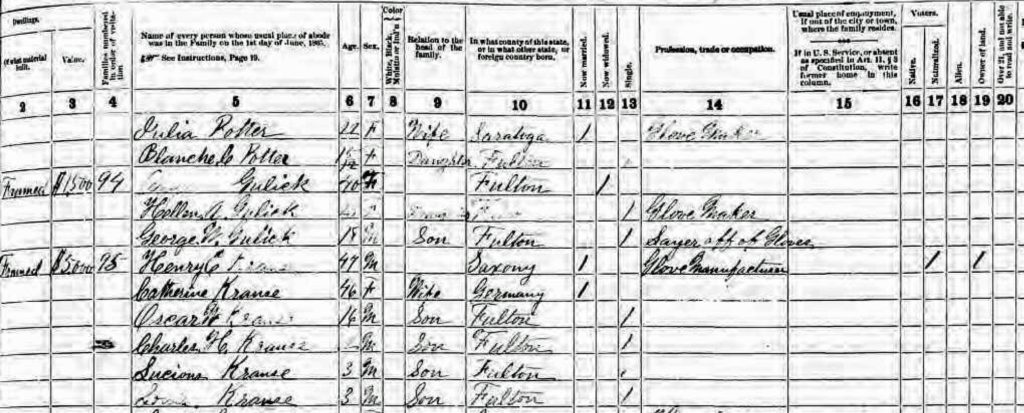

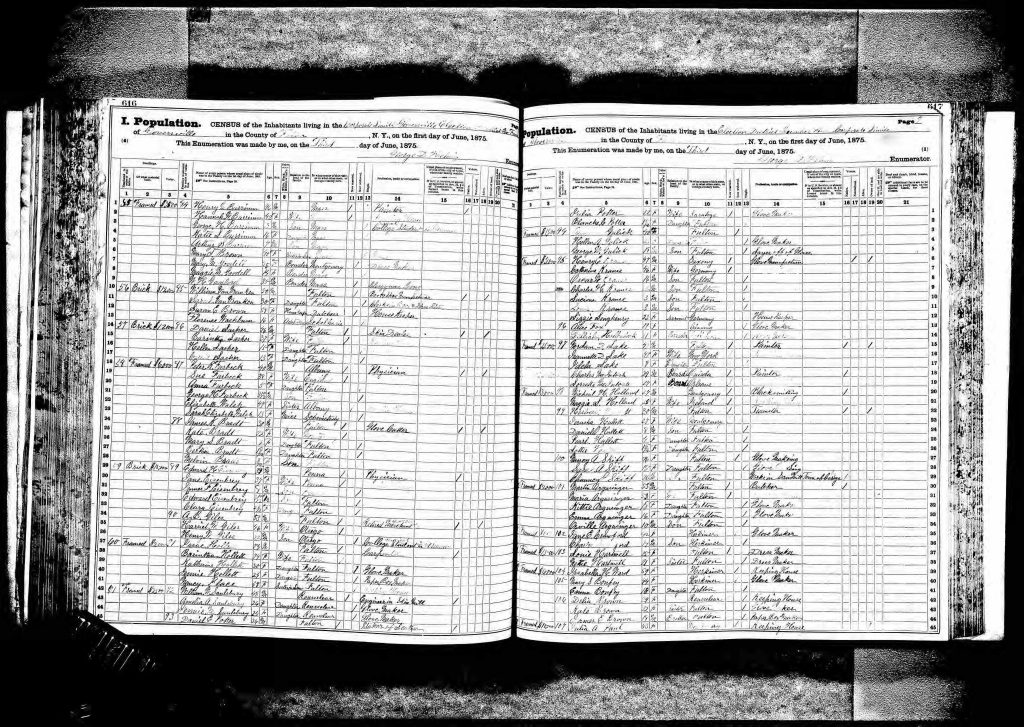

By 1875, Henry and Catherine added twins, Louis and Lucius, to the family. The twins were born in 1872. Their oldest and only daughter, Elizabeth, is no longer living with the family. Henry is reported to be 47 years old and his occupation is listed as a “Glove Manufacturer”. Catherine is reported to be 46 years old. [49]

Krause Household , 1875 New York State Census

On July 2, 1885 Henry transferred title of his home to his son Charles H Krause. [50] Three years later, in 1888, Charles sold a property to a non-family member. [51]

Catherine Fliegel Krause died at her home, located at 26 Elm Street, at 1:10 p.m. on January 27 1898. She was reported to be 68 years old. Henry Krause, passed away six months after his wife’s passing.

Obituary of Henry Krause

Both obituaries fail to mention Henry and Catherine’s first child, Elizabeth. In fact, she ‘disappears’ from my research efforts after living with her family when she was eighteen in 1870. I am assuming she married sometime after 1870 and 1875 unless she met an untimely death .

Three of the four remaining children continued to live in the Gloversville area. Lucius, one of the twins, ended up living in New York City as a chiropodist. [52]

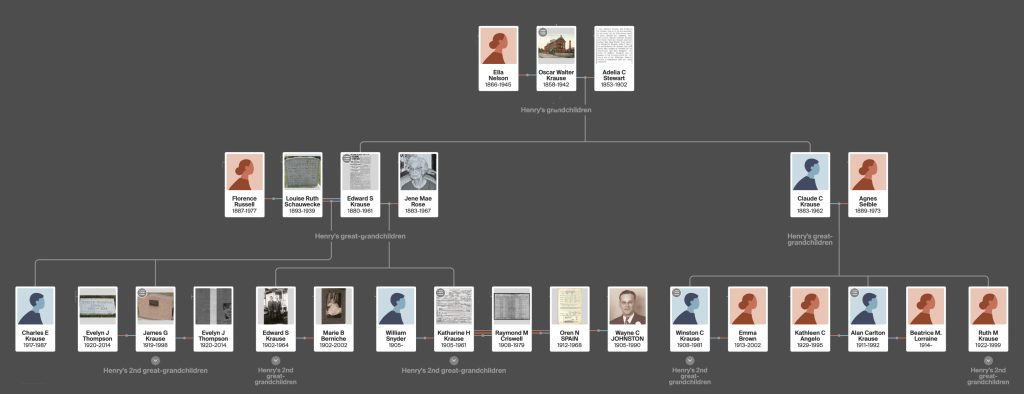

As reflected below,, Oscar and Charles, each had two children.

Three Generations of the Krause Family

Of the four grandchildren of Henry and Catherine, only Oscar’s children had children. Since many of the Henry and Catherines’ great-great grandchildren are living, they are are not listed in the following family tree.

Descendants of Oscar Walter Krause

Sources

Feature Photograph: Inside a Packet Ship, 1854, From Die Gartenlaube Leipzig Fruft Neil Courtesy of the Mariners’ Museum, Wkimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Inside_a_Packet_Ship,_1854.jpg

[1] Six generations of the Fliegel family have lived in the United States since their head of the family immigrated in the mid 1800s. See the following PDF file of the Fliegel family tree. The PDF format allows the viewers to zoom in and out to view the family tree. For reasons of privacy I have not included the current relatives living the the United States. Fliegel Family Tree. The rendering of the family tree is based on the intellectual property rights of ancestry.com. See Fliegel family tree

[2] The Daily Leader, Gloversville, 27 January 1898, Page 8. The death announcement in the newspaper provides a wealth of information regarding Katherine Fliegel’s dates surrounding her birth, immigration to the United States, and marriage to Henry Krause.

The dates for some of these events and her family are not entirely accurate nor are they corroborated by other sources.

The obituary indicates that she passed away the preceding day of the news story and she was 64 years old. This would imply she was born in 1834. Her birth has been listed as April 12, 1829 in other historical sources and in others as 1830. Nevertheless, it is currently the only piece of evidence that provides detailed dates regarding her immigration to America, her marriage, the birth of he first child and movement to the Gloversville area..

The following sources suggest that Caroline Fliegel was born in 1829:

- 1865 New York State Census, Fulton County, Gloversville Village, Johnstown, Line 20, Page 617

- 1870 U.S. Census, New York, Fulton County, Johnstown, Line 40, Page 156

- Cather / Katherine Krause / Fleigel, Find My Grave, memorial id: 183586202, birth: 12 Apr 1829, Baden, Landkreis Verden, Lower Saxony, Germany, DEATH27 Jan 1898 (aged 68), Gloversville, Fulton County, New York, USA BURIAL, Prospect Hill Cemetery Gloversville, Fulton County, New York, USA PLOT Sec 7 H.E. Krause Lot View Source https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/183586202/catherinekatherine-krause#source

- Baden, Germany, Lutheran Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials, 1502-1985, ancestry.com online records.

In addition, the obituary indicates that she and Henry lived at Elm Street, Gloversville since 1864. Index of Deeds records for Fulton county indicate Henry Krause was the Grantee of property in Fulton County in 1874. The 1864 New York census indicates that the Krause family lived in Johnstown.

The obituary also indicates that “She was survived by her four children Oscar W. Krause, Charles H. Krause, Lucius J. Krause and Louis A. Krause.” There is no mention of her first child Elizabeth.

[3] Aaslestad, Katherine, and Karen Hagemann. “1806 and Its Aftermath: Revisiting the Period of the Napoleonic Wars in German Central European Historiography,” Central European History (Cambridge University Press / UK) 39, no. 4: 547-579

Walter F. Wilcox, ed, International Migrations, Volume II: Interpretations, National Bureau of Economic Research NABER, January 1931, Chapter 12: Dr. F. Burgdörfer, Migration Across the Frontiers of Germany, p. 316-317 https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c5114/c5114.pdf

The Germans in America, European Reading Room, The Library of Congress, April 23, 2014, https://www.loc.gov/rr/european/imde/germchro.html

Irish and German Immigration, us history.org , https://www.ushistory.org/us/25f.asp

German Americans, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 4 September 2023 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_Americans

Bruce Levine, The Spirit of 1848: German Immigrants, Labor Conflict, and the Coming of the Civil War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992

Richard O’Connor, German-Americans: an Informal History. (1968), popular history

Krawatzek, Félix & Sasse, Gwendolyn. (2018). Integration and Identities: The Effects of Time, Migrant Networks, and Political Crises on Germans in the United States. Comparative Studies in Society and History. 60. 1029-1065. 10.1017/S0010417518000373. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328005527_Integration_and_Identities_The_Effects_of_Time_Migrant_Networks_and_Political_Crises_on_Germans_in_the_United_States

Walter D. Kamphoefner, Germans in America: A Concise History. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2021

Walter D. Kamphoefner, “Immigrant Epistolary and Epistemology: On the Motivators and Mentality of Nineteenth-Century German Immigrants.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 28, no. 3, 2009, pp. 34–54. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40543427

Walter D. Kamphoefner and Wolfgang Helbich, eds. German-American Immigration and Ethnicity in Comparative Perspective. Madison, Wisconsin: Max Kade Institute, University of Wisconsin–Madison 2004.

Walter Kamphoefner, The German Component to American Industrialization (1840 – 1893), Immigrant entrepreneurship, https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entries/the-german-component-to-american-industrialization/#edn12

Richard J. Bazillion, Social Conflict and PoliticalProtest in Industrializing Saxony, 1840 – 1860, Social History, Vol XVII Number 33 (May 1984: 79-92,

Amanda A. Tagore, Irish and German Immigrants of the Nineteenth Century: Hardships, Improvements, and Success, Honors College, Pace University, Paper 136, http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/136

Bade, Klaus J. “From emigration to immigration: The German experience in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.” Central European History 28.4 (1995): 507–535.

Bade, Klaus J. “German emigration to the United States and continental immigration to Germany in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.” Central European History 13.4 (1980): 348–377

U.S. Diplomatic Mission to Germany, History of German-American Relations > 1683 – 1900 – History and Immigration, June 2008, https://usa.usembassy.de/garelations8300.htm

Adams, Willi Paul. The German-Americans: An Ethnic Experience (1993) Web Archived

Aaron O’Neil, Number of migrants from Germany* documented in United States between 1820 and 1957, Statistics, June 21, 2022, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1044516/migration-from-germany-to-us-1820-1957/#statisticContainer

Some of the Key Reasons Why, Centuries Ago, Germans Immigrated to America, April 26, 2017, https://www.emissourian.com/some-of-the-key-reasons-why-centuries-ago-germans-immigrated-to-america/article_6c3fe3e5-b338-5c22-bdb9-6a1ca257bae8.html, PDF version

[4] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany: Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City 1845-80, Urbana:University of Illinois Press, 1990, page 16.

Irish and German Immigration, U.S. History , https://www.ushistory.org/us/25f.asp

Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: The Call of Tolerance, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/german/call-of-tolerance/

Amanda A. Tagore, Irish and German Immigrants of the Nineteenth Century: Hardships, Improvements, and Success, Pace University: Pforzheimer Honors College, May 2014, https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1144&context=honorscollege_theses

United States. Department of Homeland Security. Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2008. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, 2009, Table 2, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Yearbook_Immigration_Statistics_2008.pdf

See also: German Americans, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 21 June 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_Americans

Walter F. Wilcox, ed, International Migrations, Volume II: Interpretations, National Bureau of Economic Research NABER, January 1931, Chapter 12: Dr. F. Burgdörfer, Migration Across the Frontiers of Germany, p. 313-389 https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c5114/c5114.pdf

[5] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City 1845-80, Urbana:University of Illinois Press, 1990, Page 16

Walker, Mack. Germany and the Emigration, 1816-1885. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964. Pages 4-10, 26, 31

[6] Ira A. Glazier Editor, Germans to America Series II: List of Passengers Arriving Volume 6 April 1848- – October 1848, Wilmington: SR Scholarly Resources, Inc 2003, pages x- xi

[7] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City 1845-80, Urbana:University of Illinois Press, 1990, page 17, 26

Richard J. Bazillion, Social Conflict and Political Protest in Industrializing Saxony, 1840 – 1860, Social History, Vol XVII Number 33 (May 1984: 79-92,

See also:

History of German-American Relations > 1683-1900 – History and Immigration, U.S. Diplomatic Mission to German, This page was updated June 2008, https://usa.usembassy.de/garelations8300.htm.

Irish and German Immigration, U.S. History , https://www.ushistory.org/us/25f.asp. Walter F. Wilcox, ed, International Migrations, Volume II: Interpretations, National Bureau of Economic Research NABER, January 1931, Chapter 12: Dr. F. Burgdörfer, Migration Across the Frontiers of Germany, p. 313-389 https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c5114/c5114.pdf

Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: The Call of Tolerance, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/german/call-of-tolerance/

Amanda A. Tagore, Irish and German Immigrants of the Nineteenth Century: Hardships, Improvements, and Success, Honors College, Pace University, Paper 136, http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/136

European Emigration to the U.S. 1861 – 1870, Destination America, PBS, Sep 2005, https://www.pbs.org/destinationamerica/usim_wn_noflash_2.html

[8] Rüdiger Glaser, Iso Himmelsbach, Annette Bösmeier. Climate of migration? How climate triggered migration from southwest Germany to North America during the 19th century. Climate of the Past, 2017; 13 (11): 1573 DOI: 10.5194/cp-13-1573-2017

[9] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City 1845-80, (Urbana:University of Illinois Press, 1990), Page 18

[10] Simone A Wegge, To Part or Not to Part: Emigration and Inheritance Institutions in Nineteenth-Century Hesse–Cassel, Explorations in Economic History, Volume 36, Issue 1, 1999, Pages 30-55, https://doi.org/10.1006/exeh.1998.0703 Accessed 7 Sept. 2023

Hurwich, Judith J. “Inheritance Practices in Early Modern Germany.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 23, no. 4, 1993, pp. 699–718. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/206280. Accessed 7 Sept. 2023.

Simone A. Wegge, Inheritance Institutions and Landholding Inequality in Nineteenth-Century Germany: Evidence from Hesse-Cassel Villages and Towns. The Journal of Economic History, 81(3), 909-942. 2021, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050721000358

Charlotte Bartels, Simon Jäger, Natalie Obergruber, Long Term Effects of Equal Sharing: Evidence from Inheritance Rules for Land, Working Paper 28230, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge: Dec 2020, http://www.nber.org/papers/w28230

[11] 1848, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1848

Baden Revolution, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 9 June 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baden_Revolution

Lee, Loyd E. “Baden between Revolutions: State-Building and Citizenship, 1800-1848.” Central European History, vol. 24, no. 3, 1991, pp. 248–67. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4546213.

Lloyd E. Lee, Baden, Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions, Ohio University, 1997 2005 https://www.ohio.edu/chastain/ac/baden.htm

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Revolutions of 1848”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 8 May. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/event/Revolutions-of-1848

[12] 1848, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1848

[13] Baden Revolution, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 9 June 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baden_Revolution

Lee, Loyd E. “Baden between Revolutions: State-Building and Citizenship, 1800-1848.” Central European History, vol. 24, no. 3, 1991, pp. 248–67. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4546213.

Lloyd E. Lee, Baden, Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions, Ohio University, 1997 2005 https://www.ohio.edu/chastain/ac/baden.htm

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Revolutions of 1848”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 8 May. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/event/Revolutions-of-1848

[14] Grand Duchy of Baden, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Duchy_of_Baden

[15] Walter F. Wilcox, ed, International Migrations, Volume II: Interpretations, National Bureau of Economic Research NABER, January 1931, Chapter 12: Dr. F. Burgdörfer, Migration Across the Frontiers of Germany, p. 316-317 https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c5114/c5114.pdf

[16] Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: A New Surge of Growth, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/german/new-surge-of-growth/

[17] Aboard a Packet, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian, https://americanhistory.si.edu/on-the-water/maritime-nation/enterprise-water/aboard-packet

Kathi Gosz, A Look at Le Havre, a Less-Known Port for German Emigrants, 9 Oct 2011, ‘Village Life in Kreis Saarburg Germany’, Blog, http://19thcenturyrhinelandlive.blogspot.com/2011/10/look-at-le-havre-less-known-port-for.html

[18] Quote from: Genealogy Packet Boats, ships were backbone of U.S. Water travel, Tribune-Star, April 24, 2014, https://www.tribstar.com/features/history/genealogy-packet-boats-ships-were-backbone-of-u-s-water-travel/article_8033a7a5-947c-5e62-ba27-4ef854ca0343.html

See also: Packet boat, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 8 March 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Packet_boat

[19] Cohn, Raymond L., and Simone A. Wegge. “Overseas Passenger Fares and Emigration from Germany in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Social Science History 41, no. 3 (2017): 393–413. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90017919.

[20] Ibid

[21] Ira Glazier, ed., Germans to America Series II: Lists of Passengers Arriving at U.S. Ports in the 1840s, Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources, 2003, Page xiii

[21a] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration 1607 – 1860. Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press, 1941, Page 187

[22] History of Rail Transport in Germany, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 11 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_rail_transport_in_Germany

J.H. Clapham, The economic development of France and Germany, 1815-1914, Cambridge: University Press, 1921. Pages 140- 157, https://archive.org/details/cu31924013709641/mode/2up

Patrick O’Brien, Transport and Economic Development in Europe, 1789–1914. In: O’Brien, P. (eds) Railways and the Economic Development of Western Europe, 1830–1914. St Antony’s/Macmillan Series. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 1983 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-06324-6_1

Patrick O’Brien, Patrick, ed. Railways and the Economic Development of Western Europe 1830–1914 Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 1983

Andreas Kunz, Map 105: Map of Railway Lines 1846-1855, Server for digital historical mapshttps://www.ieg-maps.uni-mainz.de/mapsp/mapebga2.htm

History of Rail Transport in Germany, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 11 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_rail_transport_in_Germany.

Baden main line, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 26 February 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baden_main_line

[23] Source: The Railway Network in Europe in 1849, Karten- und Luftbildstelle der DB Mainz, Unknown author, Bahnkarte von Deutschland und Nachbarländern 1849. Dünne Linien sind Straßen. 1849, Public Domain in United States and Germany, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bahnkarte_Deutschland_1849.jpg

[23a] Ira Glazier, Ed., Germans to America Series II: Lists of Passengers Arriving at U.S. ports in the 1840s, Volume 6 April 1848 – October 1848, Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc 2003, Page xiii

[23b] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration 1607 – 1860. Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press, 1941, Page 186

[23c] The first railway bridge at Kehl across the Rhine was opened in May 1861.

Rhine Bridge, Kehl, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 25 February 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhine_Bridge,_Kehl#

[23d] The railway between Paris and Strasbourg was opened in several stages between 1849 and 1852, after Catherine’s journey to the United States.

A canal was also built concurrently and parallel with the railway line and by the same French administration, from 1839 to 1855. The 194 mile long canal was the longest in France when it opened in 1853. The canal connects the river Marne and the Canal entre Champagne et Bourgogne in Vitry-le-François with the port of Strasbourg on the Rhine. The original objective of the canal was to connect Paris and the north of France with Alsace and Lorraine, the Rhine, and Germany.

Paris-Est–Strasbourg-Ville railway, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 14 June 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris-Est–Strasbourg-Ville_railway.

Marne-Rhine Canal, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 28 February 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marne–Rhine_Canal.

The Canal de la Marne au Rhin

Canal De La Marne Au Rhin, French Waterways, https://www.french-waterways.com/waterways/north-east/marne-rhin/

[23e] Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration 1607 – 1860. Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press, 1941, Page 186

[23f] Ibid, Page 187

[24] Walker, Germany and the Emigration, pp. 46, 50, 74, 87-89; Mack Walker, Germany and the Emigration, 1816 – 1885, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964, Pages 46, 50, 74, 87-89

Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic Migration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1940. Pages 211-218 and 296-297

[25] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City 1845-80, (Urbana:University of Illinois Press, 1990), Page 24

[26] Baden, Germany, Lutheran Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials, 1783-1875: Catherina Flügel / Fluegel; Birth Date: 12 Apr 1829; Taufe (Baptism): 20 Apr 1829; Baptism Place: Ittlingen, Baden (Baden-Württemberg), Deutschland (Germany); Father: Christoph Flügel; Mother: Juliana Flügel; Parish: Ittlingen; City: Ittlingen; Evangelische Kirche Ittlingen (A. Eppingen).

[27] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City 1845-80, (Urbana:University of Illinois Press, 1990), Page 23

[27a] I reviewed available ship manifest records ships arriving in the New York City port between March 1848 through June 1848. The manifest lists are hand written. Many of the lists are difficult to read and many do not spell out the entire names of passengers. I found one manifest list that lists Catherine Fliegel in legible handwriting on the Ship Hector, arriving in New York City June 12, 1848.

Passenger lists of vessels arriving at New York, 1820-1897 [microform], U.S. Bureau of Customs, National Archives and Records Service, Washington: National archives and Records Service, 1959,

Reel 0071 – Passenger Kits of Vessels Arriving at New York 1820 – 97 The National – Mar 1 – May 8, 1848 M237 Roll 71

Reel 0072 – Passenger Kits of Vessels Arriving at New York 1820 – 97 The National – May 9 – 31, 1848 M237 Roll 72

Reel 0073 – Passenger Kits of Vessels Arriving at New York 1820 – 97 The National Jun 1 – Jul 6, 1848 – M237 Roll 73

Based on the review of the U.S. Bureau of Customs records, I isolated ships with German passengers. The following tables list the ships that were reviewed that had German passengers. Since the journey could take approximately one month, I checked ship manifest lists a month before and after May 1848.

“The average length of a westbound journey was 34 days, but it varied very much from one journey to another. Even though there were slower and faster vessels,162 one and the same ship could make a westbound trip in 41 days and the following one in 22.”

Seija-Riitta Laakso, Across the Oceans, Development of Overseas Business Information Transmission, 1815-1875, Helsinki: Helsinki University Printing House, 2006 https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7bea/f11c96cf9797721fd4aafafca8f334414c3a.pdf. Page 50.

Ships Arriving in New York March 1 – May 8, 1848

| Arrival Date | Departing Port | Ship Name |

|---|---|---|

| April 5 | -(?) | Scotland |

| April 20 | Bremen | Brig Arion |

| April 21 | Havre | Ducher d’Orleans |

| April 22 | Antwerp | Shakespeare |

| April 22 | Bremen | Bark Minna |

| April 24 | Harvre | St. Nicholas |

| April 24 | Hamburg | Leibniz |

| May 2 | Bremen | Famal |

| May 2 | Antwerp | Shepard |

| May 3 | Bremen | Brig Lesmovin (?) |

| May 4 | Hamburg | Hamburg Bank Washington |

| May 5 | Bremen | Bank Caroline |

| May 5 | (?) | Powhatten |

| May 5 | Havre | Monitor Livingston |

| May 6 | Bremen | Matador |

| May 8 | Bremen | Emma |

| May 8 | Antwerp | Tennessee |

Ships Arriving in New York May 9 – May 31, 1848

| Arrival Date | Departing Port | Ship Name |

|---|---|---|

| May 9 | Havre | Augusta |

| May 9 | Havre | Amazon |

| May 11 | Bremen | Bank Boden |

| May 11 | Bremen | Von Humbolt |

| May 11 | Rotterdam | F.G. Wicheleausen |

| May 12 | Hamburg | Brarens (?) |

| May 12 | Hamburg | Caroni (?) |

| May 15 | Antwerp | Echo |

| May 15 | Havre | Havre |

| May 18 | Rotterdam | Amicitia |

| May 18 | Havre | Luchinvas (?) |

| May 19 | Antwerp | Victoria |

| May 21 | Bremen | Vater Gunner |

| May 21 | Havre | Emma Heyn |

| May 21 | Bremen | Atlantic |

| May 21 | (?) | Magdamina |

| May 23 | Bremen | Livonig |

| May 23 | Antwerp | Inciatta (?) |

| May 24 | Hamburg | Howard |

| May 25 | Havre | Onego |

| May 26 | Bremen | Westphalia |

| May 26 | Bremen | Lessing |

| May 26 | Havre | Baltimore |

| May 27 | Bremen | Auckland |

| May 27 | Bremen | Pacific |

| May 27 | Hamburg | Manon |

| May 27 | Antwerp | May Flower |

| May 27 | Rotterdam | Henry |

| May 27 | Bremen | Marianne |

| May 27 | Bremen | Argonaut |

| May 28 | Bremen | Meta |

| May 29 | Bremen | Elise Charlotte |

| May 29 | Bremen | Melanie Elise |

| May 29 | Havre | Charborne |

| May 29 | Bremen | Atlantic |

| May 29 | Havre | Adams |

| May 29 | Antwerp | Larns |

| May 29 | Antwerp | Adelaide |

| May 29 | Bremen | Bark Orion |

| May 29 | Bremen | Bark Francisca |

| May 29 | Havre | Far West |

| May 29 | Antwerp | Anna |

| May 29 | Antwerp | Manchester |

| May 29 | Hamburg | Fretag |

| May 29 | Bremen | Meta Denison |

| May 29 | Havre | Eliza Dessuchn (?) |

| May 30 | Bremen | Mercury |

| May 30 | Hamburg | Perserverance |

| May 30 | Havre | Bavaria |

| May 30 | Antwerp | Mathilde |

| May 31 | Bremen | Mary |

| May 31 | Hamburg | Emma Heyn |

| May 31 | Bremen | Amazon |

Ships Arriving in New York June 1 – July 6, 1848

| Arrival Date | Departing Port | Ship Name |

|---|---|---|

| June 1 | Havre | Tremont |

| June 1 | Havre | Burgundy |

| June 2 | Amsterdam | Bark Dione |

| June 3 | Hamburg | Bark Lessing |

| June 3 | Bremen | Bark Regina |

| June 3 | Bremen | Brig Joshua |

| June 5 | Rotterdam | Bark Helene Catharine |

| June 5 | Antwerp | Brig Antwerpia |

| June 5 | Havre | Alfred |

| June 5 | Rotterdam | Oscar |

| June 10 | Havre | Medemseh |

| June 12 | Bremen | Basserman |

| June 12 | Rotterdam | Bark Antoleon |

| June 12 | Bremen | Belinda |

| June 12 | Antwerp | Barque Orion |

| June 12 | Antwerp | Ship Luconia |

| June 12 | Havre | Ship Hector |

| June 12 | Havre | Ship Laura |

| June 12 | Amsterdam | Barque Osprey |

| June 12 | Bremen | Schooner Heros |

| June 12 | Bremen | Ship Rapide |

I also reviewed lists of ships and German immigrants found in: Ira Glazier, Ed., Germans to America Series II: Lists of Passengers Arriving at U.S. ports in the 1840s, Volume 6 April 1848 – October 1848, Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc 2003

[28] Richard Haberstroh, The German Churches of Metropolitan New York : A Research Guide / Richard Haberstroh. New York, N.Y.: New York Genealogical & Biographical Society, 2000.

[29] In this region, part of Germany which was lost to other countries after World War II, many records, both church/parish registers and civil registration records, were damaged, destroyed, or misplaced. Province of Saxony (Provinz Sachsen), German Empire Civil Registration,

FamilySearch, This page was last edited on 2 August 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Province_of_Saxony_(Provinz_Sachsen),_German_Empire_Civil_Registration

[30] Saxony, Britannica Last Updated: Aug 2, 2023 , https://www.britannica.com/place/Saxony-historical-region-duchy-and-kingdom-Europe

Saxony, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 21 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saxony

[31] Map source: Das Königreich Sachsen innerhalb des Deutschen Bundes, 11 Nov 2012, Diese Datei ist lizenziert unter der Creative-Commons-Lizenz , Königreich Sachsen im Deutscher Bund.png, https://wiki.genealogy.net/Datei:Königreich_Sachsen_im_Deutscher_Bund.png

The German Confederation was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, which had been dissolved in 1806. The Confederation had only one organ, the Federal Convention.

German Confederation, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 7 September 2023

James Sheehan, German History, 1770-1866. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1989.

[32] Saxony, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 21 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saxony

Industrialization in Germany, Wikipedia,This page was last edited on 27 July 2023https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrialization_in_Germany

[33] Schäfer, Michael. (2015). Global Markets and Regional Industrialization: The Emergence of the Saxon Textile Industry, 1790–1914. In Regions, Industries, and Heritage (pp.116-135) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304820792_Global_Markets_and_Regional_Industrialization_The_Emergence_of_the_Saxon_Textile_Industry_1790-1914

“Saxony is commonly regarded one of the main industrial regions of 19th-century Germany. Industrialization processes started early and apparently this was closely connected to the region’s ‘proto-industrial’ roots. Saxony had been producing goods for markets outside the region itself ever since silver ore had been discovered in the mountainous woodlands bordering Bohemia. For centuries the Erzgebirge – Ore Mountains – region was virtually scattered with mines, foundries and forges where quite an impressive range of metals and minerals was extracted and proc-essed: silver, copper, tin, iron, zinc, nickel, cobalt, even uranium. Home workers produced cutlery and other household goods, musical instruments or wooden toys. Lace-, ribbon- and border-making had spread throughout the Ore Mountains from the 16th century onwards. Many other textile goods were manufactured in the lower regions north and west of the Erzgebirge proper: in the Vogtland as well as in the Chemnitz area, and further east in Upper Lusatia (Oberlausitz). But ore mining had been declining ever since the heydays of the silver boom in the 1490s to the 1520s and thus played only a minor role in the Industrial Revolution. More important for the industrial transformation of Saxony in the 19th century were certainly the various branches of textile manufacture.”

“Weavers’ Revolt .” St. James Encyclopedia of Labor History Worldwide: Major Events in Labor History and Their Impact. . Encyclopedia.com. 18 Sep. 2023 https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/weavers-revolt

Charles Tilly, Louise Tilly, and Richard Tilly. The Rebellious Century, 1830-1930.Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1975.

Jürgen Kocka, “Problems of Working-Class Formation in Germany: The Early Years, 1800-1875.” In Working-Class Formation: Nineteenth-Century Patterns in Western Europe and the United States, edited by Ira Katznelson and Aristide R. Zolberg. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986.

[34] “H.E. Krause” Age 21, departed from Hamburg, Germany and arrived in New York port on 31 May 1848 on the Emma Heyn. The National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, D.C.; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at and Departing from Ogdensburg, New York, 5/27/1948 – 11/28/1972; Microfilm Serial or NAID: M237, 1820-1897, image 7. Line 9.

Passenger lists of vessels arriving at New York, 1820-1897 [microform], U.S. Bureau of Customs, U.S. national Archives and Records Service, Reel 0072 – Passenger List of Vessels Arriving at New York 1820-97 The National – May 9 – 31, 1848, Page 830 – 831 https://archive.org/details/passengerlistsoo0072unix/page/n837/mode/2up

[35] James K Pollack and Homer Thomas, Homer (1952). Germany in Power and Eclipse. New York, NY: Dylan Hill, 1952, Page 510

[36] Richard Moses, Development of Kleindeutschland or Little Germany, Lower East Side Preservation Initiative, https://lespi-nyc.org/kleindeutschland-little-germany-in-the-lower-east-side/

[37] Philip Liu, Germans, The People of New York, City College of New York CCNY, This page was last modified 13 May 2009 . Based on work by Qing Qing Wu, Richard Huang and Lindsey Freer, https://macaulay.cuny.edu/seminars/drabik09/articles/g/e/r/Germans.html,

[38] Germans, The People of New York, City College of New York CCNY, This page was last modified 13 May 2009 by Philip Liu. Based on work by Qing Qing Wu, Richard Huang and Lindsey Freer, https://macaulay.cuny.edu/seminars/drabik09/articles/g/e/r/Germans.html

Richard Moses, Development of Kleindeutschland or Little Germany, Lower East Side Preservation Initiative, https://lespi-nyc.org/kleindeutschland-little-germany-in-the-lower-east-side/

Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999 Page 745

Sabrina Axster, Deutschland in the US, Part I: tracking German migration, Dec 21, 2015, updated Aug 16, 2017, New Women New Yorkers, Propelling Immigrant Women to greater Heights, part-i-tracking-german-migration

Sabrina Axster, Deutschland in the US, Part II: Coming to New York, Dec 21, 2015, updated Aug 16, 2017, New Women New Yorkers, Propelling Immigrant Women to greater Heights, https://www.nywomenimmigrants.org/coming-to-new-york/

Kleindeutschland and the Lower East Side, Manhattan – Streets, http://www.maggieblanck.com/NewYork/LowerEastSide.html

Little Germany, Manhattan, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 8 August 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Germany,_Manhattan

Stanley Nadel, Little Germany: Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City, 1845-80, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990,

Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press., 1999,

Fans Jacobs, The Short Life of Little Germany, New York’s First Ethnic Enclave, June 22, 2014, ThinkBig, https://bigthink.com/strange-maps/663-death-of-little-germany-how-a-ship-sank-an-enclave/

[39] Stanley Nadel (1990), Little Germany: Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City, 1845-80, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990, Pages 29, 37-39

[40] Little Germany, Manhattan, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 8 August 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Germany,_Manhattan

[41] Stanley Nadel (1990), Little Germany: Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City, 1845-80, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990, Page 38

[42] Little Germany, Manhattan, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 8 August 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Germany,_Manhattan

[43] Stanley Nadel (1990), Little Germany: Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City, 1845-80, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990, Page 23

[44] Timothy G. Anderson Ohio University, David j Wishart, ed, Germans, Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, Paged accessed 22 Sep 2023, http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.ea.013.xml

A research project by Krawatzek and Gwendolyn Sasse developed a computer-aided textual analysis of about 6,000 letters sent between the US and Germany between 1830 and 1970. Their contents allowed the researchers to trace how migrants’ identities and transnational ties changed over the decades.

See: Félix Krawatzek and Gwendolyn Sasse, Writing home: how German immigrants found their place in the US, February 18, 20016, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/writing-home-how-german-immigrants-found-their-place-in-the-us-53342

Félix Krawatzek, Gwendolyn Sasse, The simultaneity of feeling German and being American: Analyzing 150 years of private migrant correspondence, Migration Studies, Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2020, Pages 161–188 https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mny014

Félix Krawatzek and Gwendolyn Sasse, Integration and Identities: The Effects of Time, Migrant Networks, and Political Crises on Germans in the United States. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 60(4), June 2018, 1029-1065. doi:10.1017/S0010417518000373 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/comparative-studies-in-society-and-history/article/abs/integration-and-identities-the-effects-of-time-migrant-networks-and-political-crises-on-germans-in-the-united-states/A5B951CA7AEB2C2C33958799C40FDDA2

Félix Krawatzek and Gwendolyn Sasse, Deciphering Migrants’ Letters, November 28, 2018, comparative Studies in Society and History, https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/cssh/tag/krawatzek/

Walter D. Kamphoefner, Wolfgang Helbich, et al., Editors., News from the Land of Freedom: German Immigrants Write Home (Documents in American Social History) : Cornell University Press, 1991.

[45] Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: Germans – A New Surge of Growth, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/german/new-surge-of-growth/

[46] “By using both federal censuses (administered by the U.S. Government every ten years beginning in 1790) and state censuses (administered by the State of New York every ten years beginning in 1825), one could theoretically locate a family every five years, creating a fantastic framework for further research and uncovering a lot of useful information in the process.”

New York State Census Records Online, New York Genealogical & Biographical Society, https://www.newyorkfamilyhistory.org/subject-guide/new-york-state-census-records-online#1865

Henry Krause Household. New York State Archives; Albany, New York, USA; 1865 Census of the State of New York, 1865, page 429, Lines 19-23. Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., State Census, 1865 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data:Census of the state of New York, for 1865. Microfilm. New York State Archives, Albany, New York.

[47] Household of Krause Family, 1870; Census Place: Johnstown, Fulton, New York; Roll: M593_938; Page: 156 and 157, Ancestry.com. 1870 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch. Original data: 1870 U.S. census, population schedules. NARA microfilm publication M593, 1,761 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.Minnesota census schedules for 1870. NARA microfilm publication T132, 13 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.

[48] Index of Deeds, Fulton County, New York, Page, Line 9, Page 406, “United States, New York Land Records, 1630-1975”, database with images, FamilySearch(https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:CSBD-XL2M : 1 March 2023), Henry E Krause, 1874.

| Grantee’s Name | Henry E Krause |

|---|---|

| Grantor’s Name | Harman G Krause |

| Event Type | Land Assessment |

| Event Date | 7 Dec 1874 |

| Event Place | Fulton, New York, United States |

| Entry Number | 46 |

| Page Number | 494 |

[49] Household of Krause Family 1875, New York State Archives; Albany, NY, USA; Census of the State of New York, 1875, Fourth Election district of corporate limits of Gloversville, Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., State Census, 1875 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013. Page 617, Lines 6-11

Original data:Census of the state of New York, for 1875. Microfilm. New York State Archives, Albany, New York.

[50] “United States, New York Land Records, 1630-1975”, database with images, FamilySearch(https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6N74-PYRW : 1 March 2023), Henry E Krause, 1885.

| Grantee’s Name | C H Krause |

|---|---|

| Grantor’s Name | Henry E Krause |

| Event Type | Land Assessment |

| Event Date | 2 Jul 1885 |

| Event Place | Fulton, New York, United States |

| Entry Number | 65 |

| Page Number | 572 |

[51] “United States, New York Land Records, 1630-1975”, database with images, FamilySearch ( https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6N74-PYRZ : 1 March 2023), Henry E Krause, 1888.

| Grantee’s Name | Salem T Foster |

|---|---|

| Grantor’s Name | Henry E Krause |

| Event Type | Land Assessment |

| Event Date | 13 Apr 1888 |

| Event Place | Fulton, New York, United States |

| Entry Number | 72 |

| Page Number | 89 |

[52] Chiropody is an historic term which has been used to describe someone that specializes in the health and well-being of feet. According to the Institute of chiropody and podiatry, it was not until more recent years that the professional title of Podiatrist was created to recognize the specialist qualifications of the profession.

Podiatry, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 10 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Podiatry

Ships Arriving in New York June 1 – July 6, 1848

| Arrival Date | Departing Port | Ship Name |

|---|---|---|

| June 1 | Havre | Tremont |

| June 1 | Havre | Burgundy |

| June 2 | Amsterdam | Bark Dione |

| June 3 | Hamburg | Bark Lessing |

| June 3 | Bremen | Bark Regina |

| June 3 | Bremen | Brig Joshua |

| June 5 | Rotterdam | Bark Helene Catharine |

| June 5 | Antwerp | Brig Antwerpia |

| June 5 | Havre | Alfred |

| June 5 | Rotterdam | Oscar |

| June 10 | Havre | Medemseh |

| June 12 | Bremen | Basserman |

| June 12 | Rotterdam | Bark Antoleon |

| June 12 | Bremen | Belinda |

| June 12 | Antwerp | Barque Orion |

| June 12 | Antwerp | Ship Luconia |

| June 12 | Havre | Ship Hector |