This is part five of a story about Johann Wolfgang Sperber immigrating to the United States.

The first of this story provided an overview of the family legacy John Sperber established in his new homeland, an historical background on where John was from in Baden, Germany, the influences on his migration to the United States, and the historical evidence of his departure and arrival to America.

The second part of John Sperber’s story describes his journey from Baden-Baden to Le Havre based on historical evidence and historical accounts.

The third part of the story assesses the three major inland pathways to European ports that John had options to consider. Since it is not absolutely certain that John sailed on the Germania from Le Havre, I have provided historical background on the relative accessibility of the three major routes John may have taken to make his voyage to the United States.

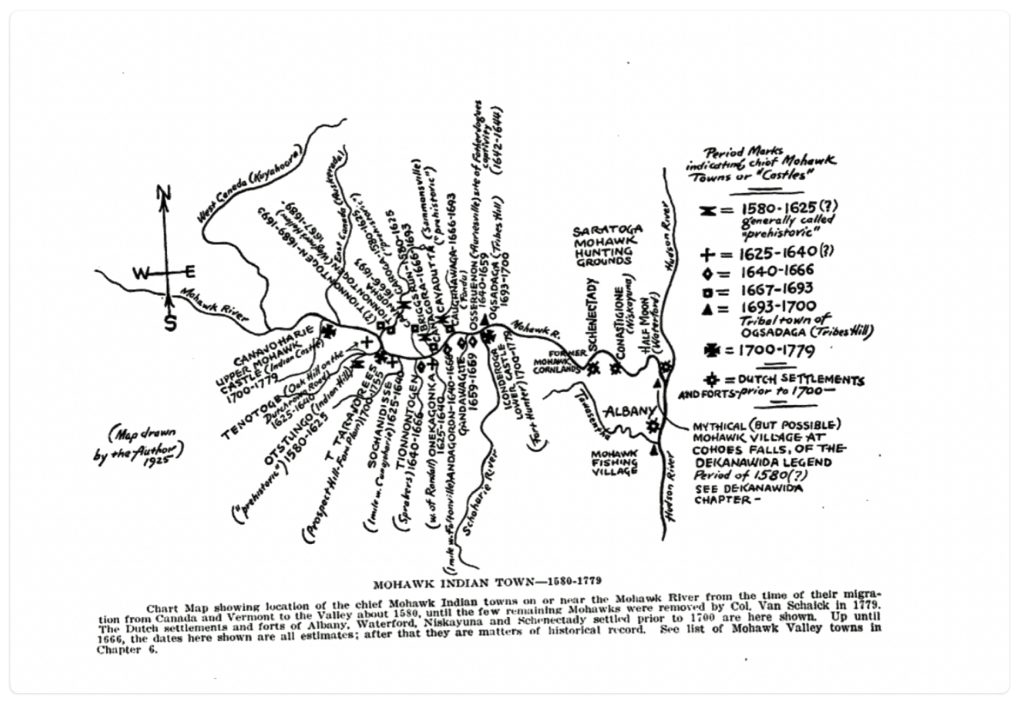

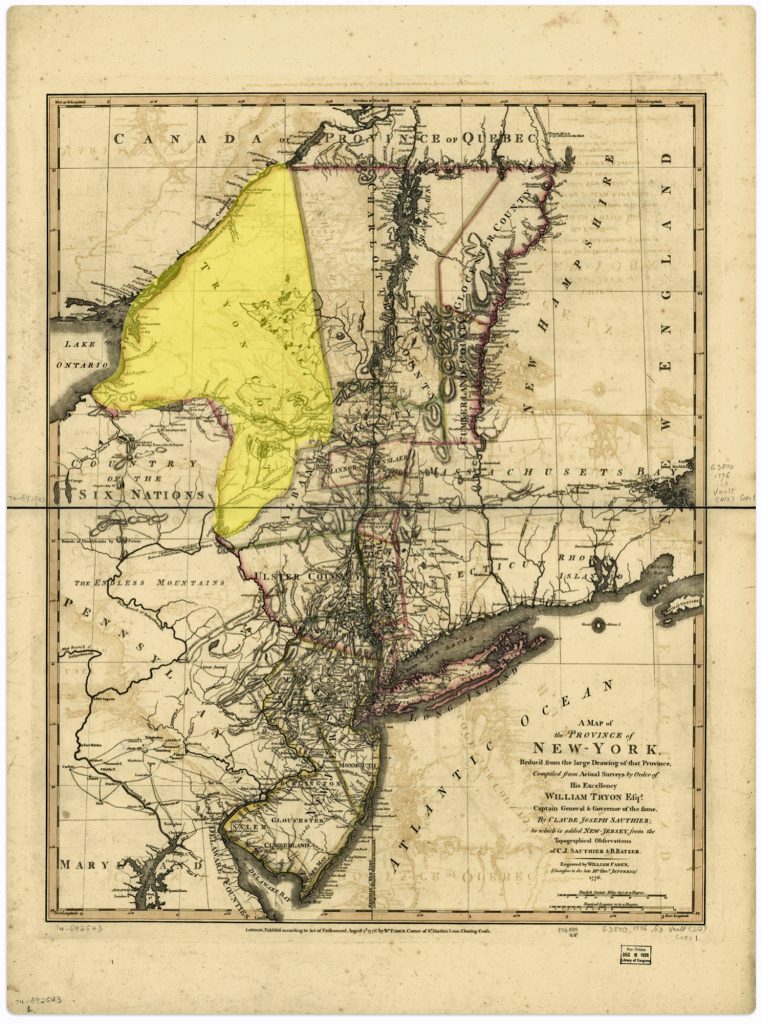

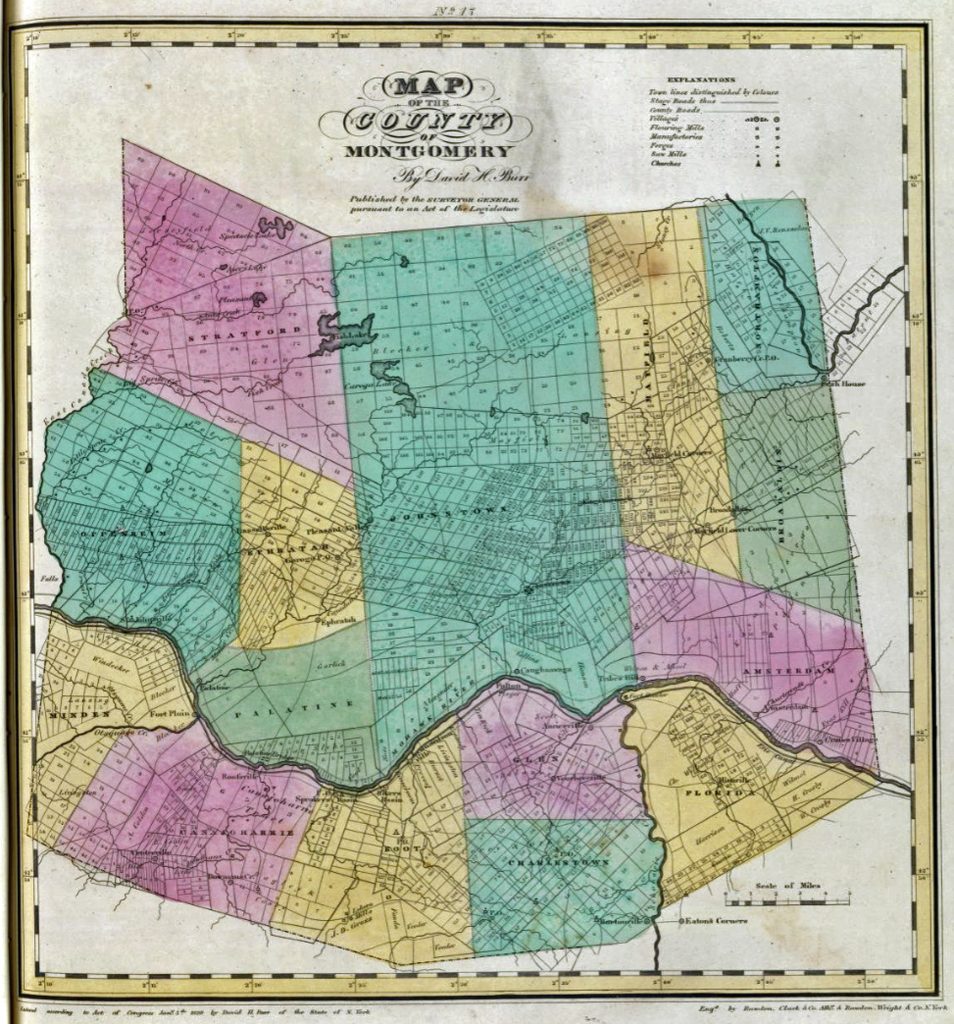

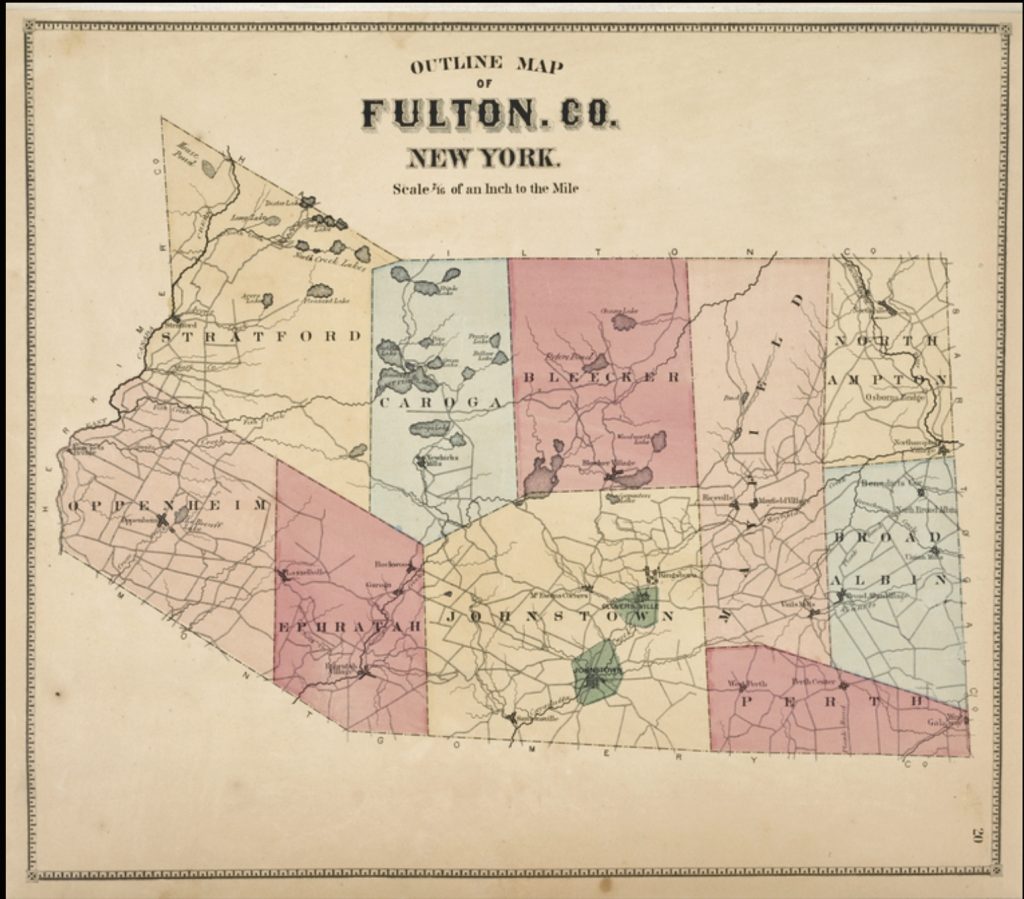

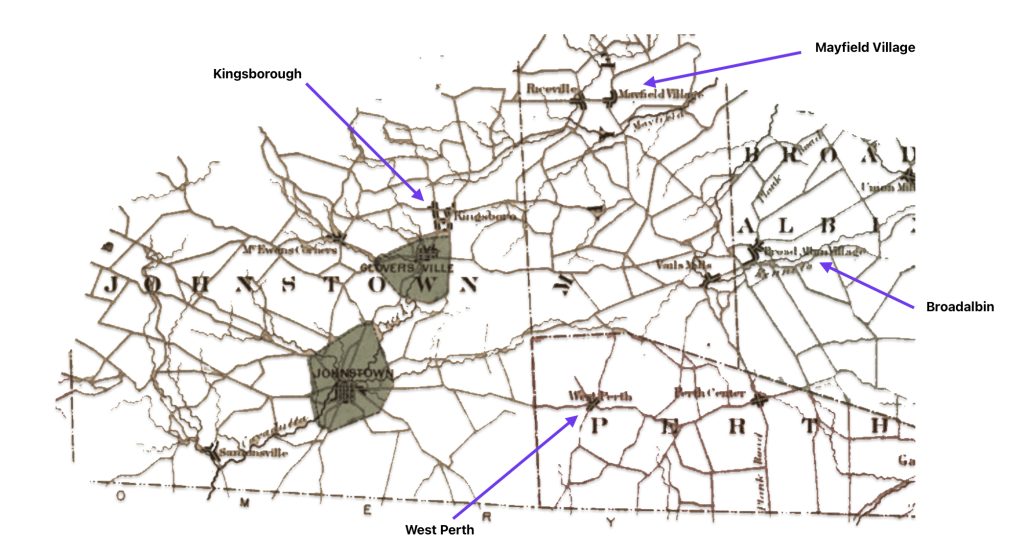

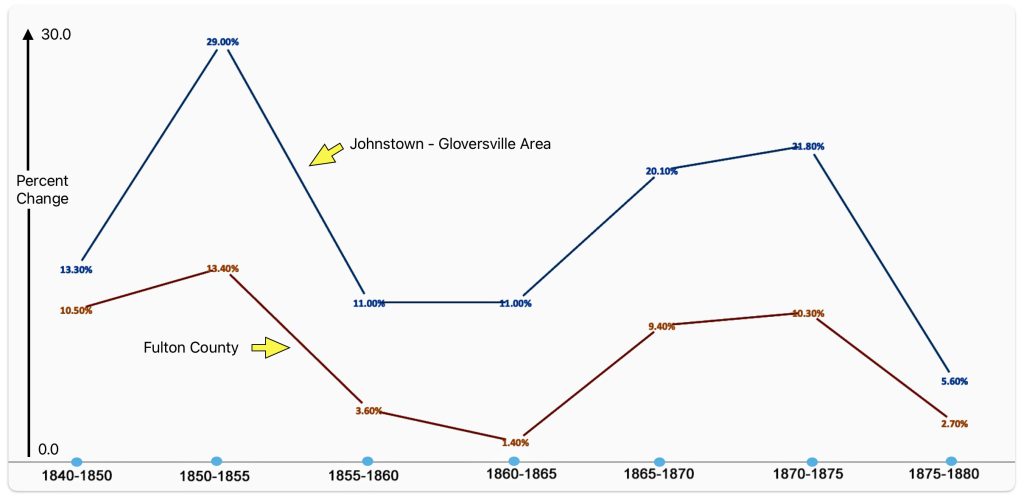

The fourth part of the story provides possible explanations of why Johann ended up in Fulton County, New York working in the glove making industry.

The fifth part of the story covers his travel to New York City and his options to travel to Gloversville, Fulton County, New York.

The sixth part of the story covers his establishing a new life and family in the Johnstown and Gloversville, New York area. This is the end of a rather long story that attempts to provide not only a discussion of the available ‘facts’ we have of Johann and his family but also provide a broader social and historical context in which he made this journey from Baden to New York state. Like a song, some of the ‘facts’ are a refrain from prior parts of the story.

Johann’s Journey from Le Havre, France

When Johann arrived in Le Havre, France to board a Harvre-Union line packet ship, it is not known how long he waited to start his trans-Atlantic journey. Johann may have already purchased a ticket in advance from an Havre travel agent on the French-Baden border before he started his westward journey across northern France. He conversely may have waited to purchase a ticket, given the uncertainties of travel, once he arrived in Le Havre. [1]

With a ticket in hand, he may have waited for a ship to board staying in or around the ‘German district’ in Le Havre. The German district, as discussed in a previous story, was a small area of about two and a half acres of land in the inner section of the port city. The German district existed for about forty years until 1856, after going through successive stages of demolition.

“This small port district of the old Le Havre … built on the former north-western front of the citadel . … . (the German district was) wedged between the barracks of the old citadel and the quay of the same name. Five small streets crossed the quarter, some of which were lined with shops and stalls. The 300 inhabitants, for the most part of modest backgrounds, exercised professions as diverse as sailor, day laborer, grocer, shoemaker or liquor shopkeeper. [2]

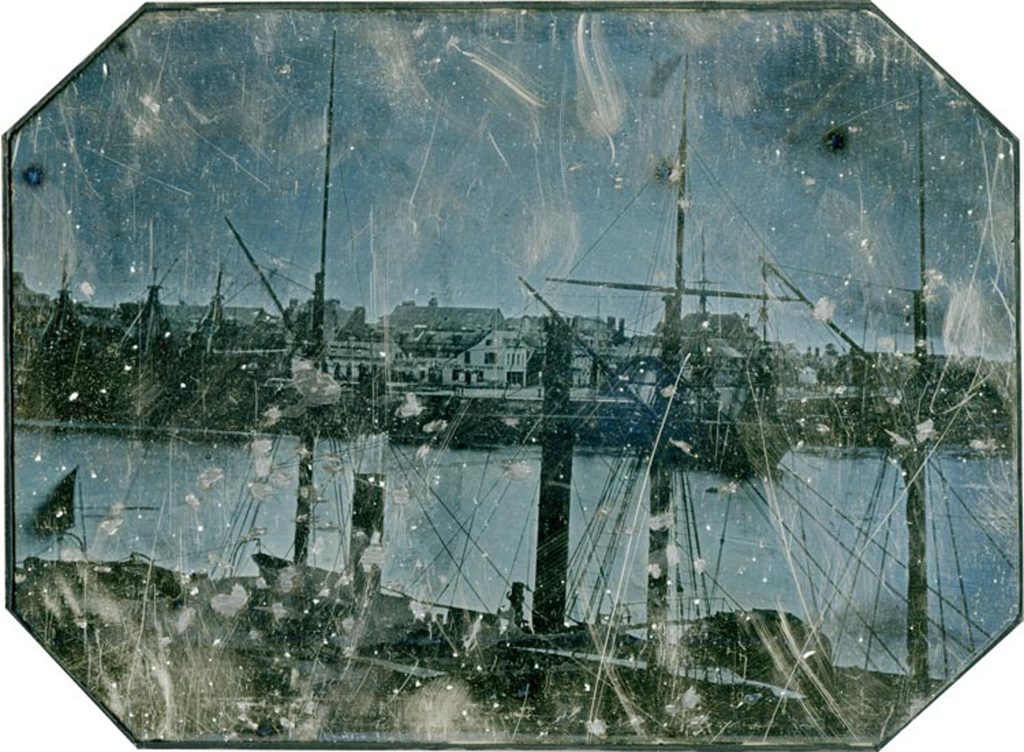

1845 Daguerreotype of the Port of Le Havre – German District [3]

The German District was a natural urban outgrowth of the successive waves of German immigrants traveling to Le Havre to start their journey to the United States. This small area of the port grew and prospered, providing services that were needed for the German emigrants waiting to board packet ships. Starting in 1846, the district was demolished in successive stages. By 1856, the district was no longer in existence.

Rediscovery of Historical Facts in a Daguerreotype Photograph

Gregory Saillard provides an interesting and wide ranging analysis of the 1845 Daguerreotype photograph of the Le Havre port shown above. His analysis and insight provides comparisons with drawings and paintings of the subject area during this time period.

“(T)he photograph … undeniably constitutes, by its date (ca. 1845-1848), its nature (daguerreotype “in the open air”), its dimensions (full plate format), and its subject (a forgotten corner from the old Le Havre), a very important archive piece, at least on a regional scale.” [4]

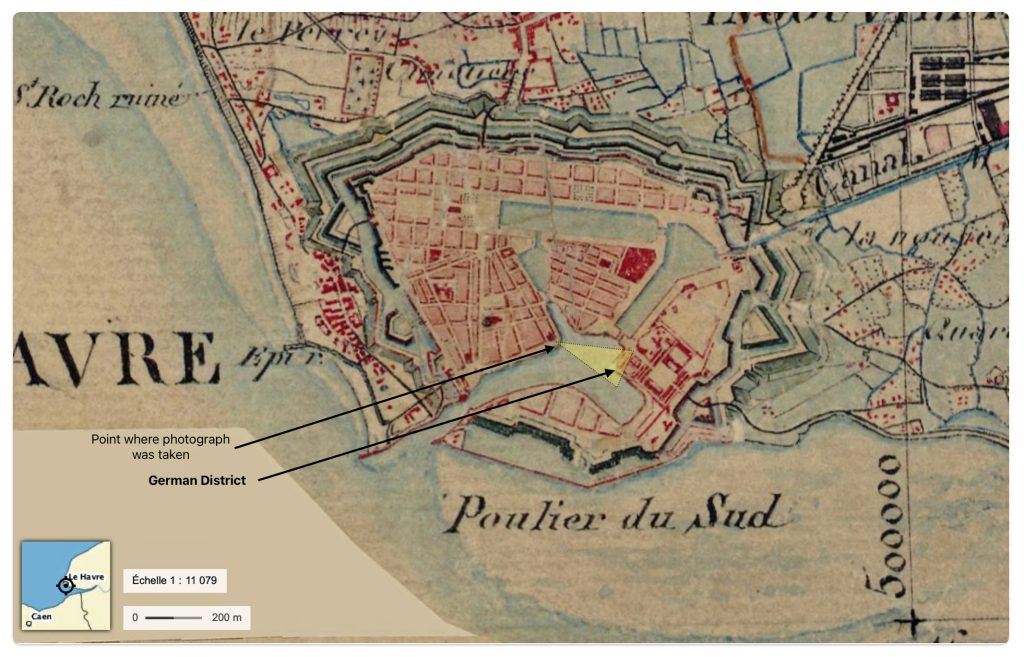

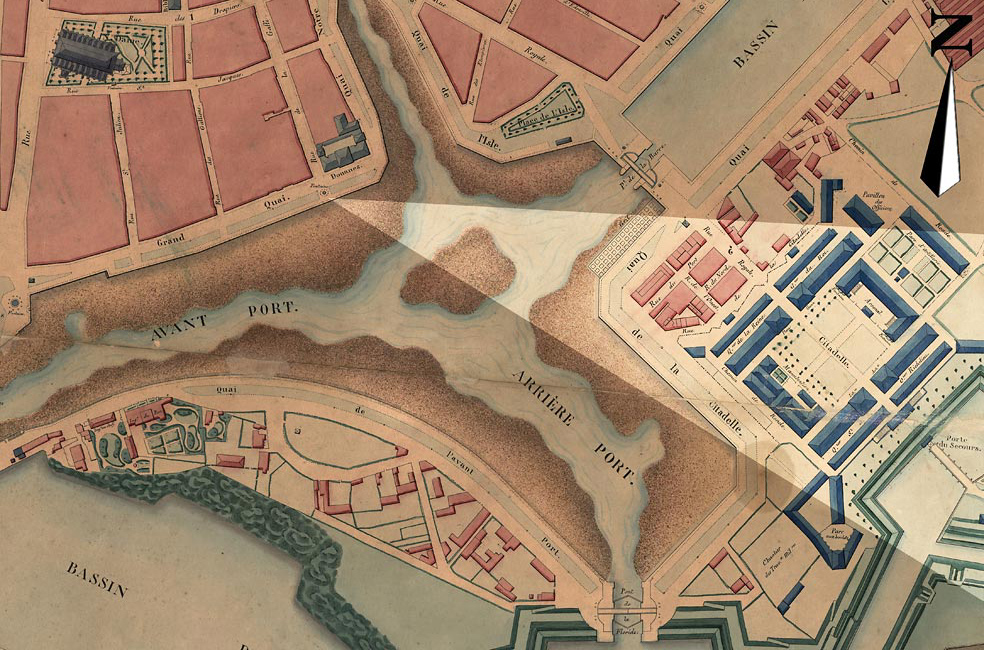

Viewing the Angle of the Photograph of the German District with Old Maps

Saillard points out that among the most interesting elements of the landscape in the photograph is the presence of the Germain district, which can be clearly seen in the center of the image. In his analysis of the old photograph he points out the angle from which the photograph was taken in the old port area of the city on an 1843 map.

Angle from Where the 1845 Daguerreotype was Photographed

We can ‘zoom out’ further to view the Le Havre port and its environs by relying on digital version of the carte d’état-major (1820-1866).

The carte d’état-major is an amazing series of maps in terms of what it covers, how it was developed, and the organization behind the production of the map. The carte d’état-major is a general map of France produced in the nineteenth century by the French army’s geographical services (Dépôt de la Guerre). It covers the entirety of France in 273 sheets. It also reflects the use of cutting edge techniques (at the time) of topographic surveying and representation methods, especially for relief, which was based on leveling measurements. [5]

Johann was one of many Germans, particularly from Baden, who used the packet ship services from Le Havre to sail to New York city. Between 1830 and the early 1850s, Le Havre was the major port of embarkation for German emigrants to the United states from the Rhine valley area to the United States. It was not until 1852 that Bremen first superseded Le Havre as the major port for the emigration of German nationals. Even after 1852, Le Havre remained the port of choice for ethnic Germans along the southwest area of the Rhine valley.

As a Badener, Johann was not alone in departing from Le Havre. In 1852, the year that Johann departed from Le Havre, sixty-three percent of the total number of immigrants leaving from Le Havre were from the German confederated states. Of the sixty-three percent, thirty-five percent of the German immigrants were from the Grand Duchy of Baden. Of the German confederated states, only Bavaria had more departing from Le Havre with almost half of the German immigrants departing from the port. Together, Bavaria and Baden overwhelmingly represented the number of immigrants departing from Le Havre. [6]

Johann’s Ship – The Havre-Union Germania

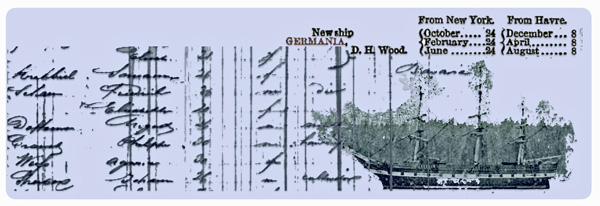

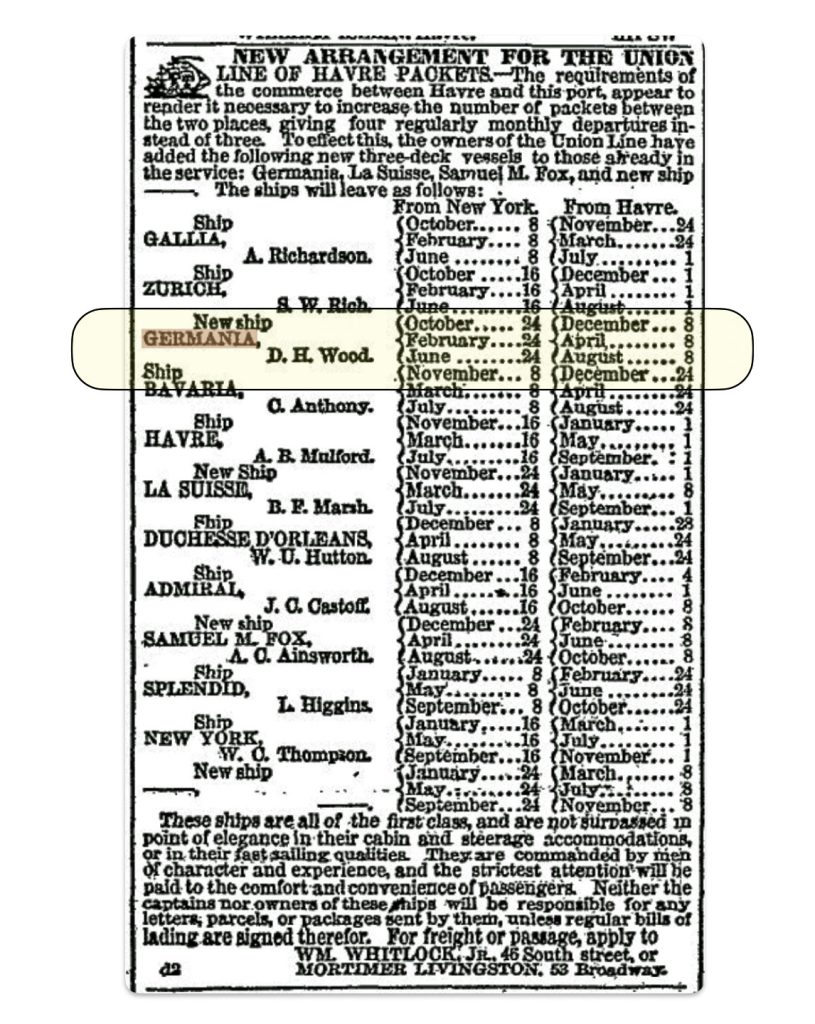

One of the hallmark characteristics of the Havre Union Packet ship service was its regularly scheduled service between Le Havre and New York city. The monthly schedules for each of the Havre Union Line ships were relatively stable, barring unforeseen changes in weather or other issues that might delay a scheduled departure date. [7]

At the time of Johnann Sperber’s voyage, there were eleven ships that were making four regularly scheduled round trip voyages between Le Havre and New York City for the Union Line of Havre each month. At the time, the Germania was one of the newer ships in the Havre Whitlock Line. [8]

Standard Advertisement for the Havre-Union Packet Line [9]

Johann’s day of departure from Le Havre is not known. However, we can arrive at an estimate of when the ship Germania left port. If John Sperber arrived in New York City on June 14, 1852, as reflected in the Germania ship manifest, [10] then based on the reliance of information found in the company’s advertised ship schedule (above), his ship was scheduled to depart from Le Havre on April 8th 1852. If the ship departed on time, this implies the journey took 64 days.

However, records on the westbound passages for the ship Germania indicate the longest trip was 52 days. Since none of the ship’s documented trips were 64 days in length, It would appear that the departure of John’s ship was delayed at the port of Le Havre. Documentation on the ship indicate that the average westbound passage for the Germania was 33 days. John’s voyage to America may have started on or around May 8th, 1852. [11]

Stereographic Photograph of the Ship Germania at Dock in Le Havre [12]

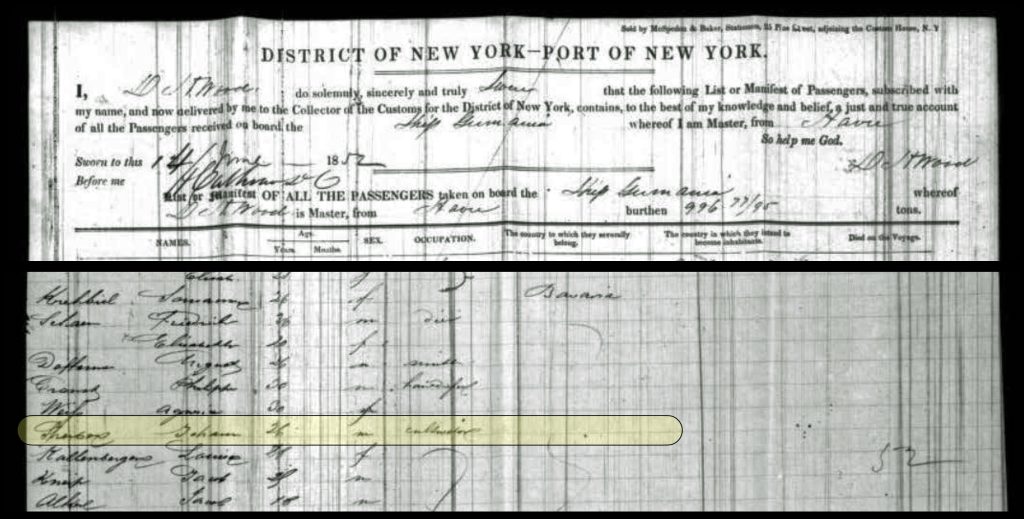

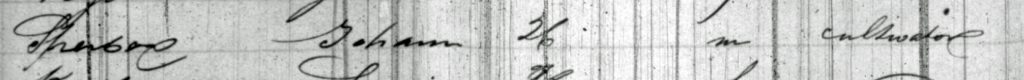

Based on the ship manifest records, Johann’s birth date was recorded as 1826. Johann Sperber was purportedly 26 years old when he came to America. His birth place was listed as ‘Bavaria‘. He traveled in the steerage area of the ship. The manifest indicated Johann’s professed occupation was a ‘cultivator‘, a farmer.

Ship Manifest List – Johann Sperber“: The Heading of the Manifest List & a Section of Page Six Where Johann Sperber is Listed [13]

While ‘Johann Sperber’ was identified as being from Bavaria on the ship’s manifest, it is possible he was summarily lumped in with the rest of the ‘Bavarian’ Germans he may have been situated with in the steerage area of the ship when the Captain went around and canvassed the passengers and compiled his manifest list. On an earlier page of the manifest list, the captain lists a number of emigrants from Baden.

The Arrival to New York City

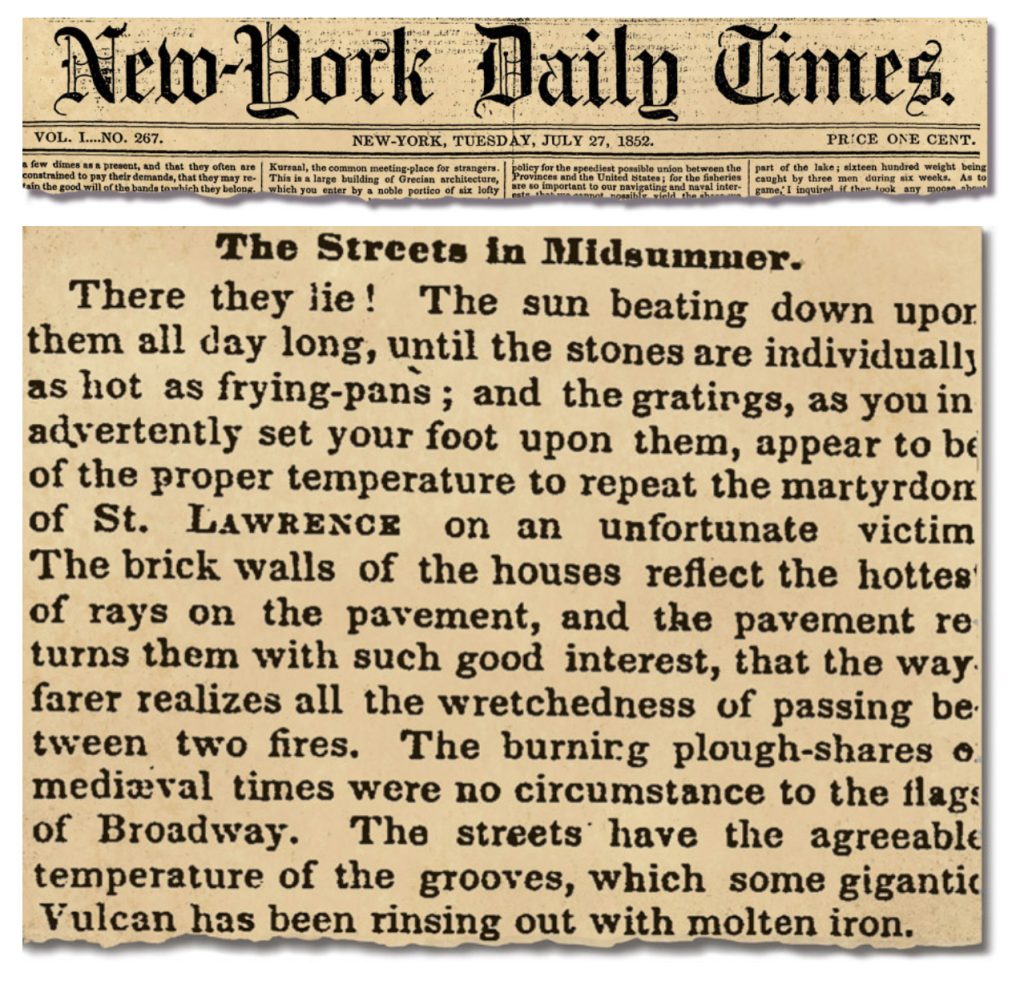

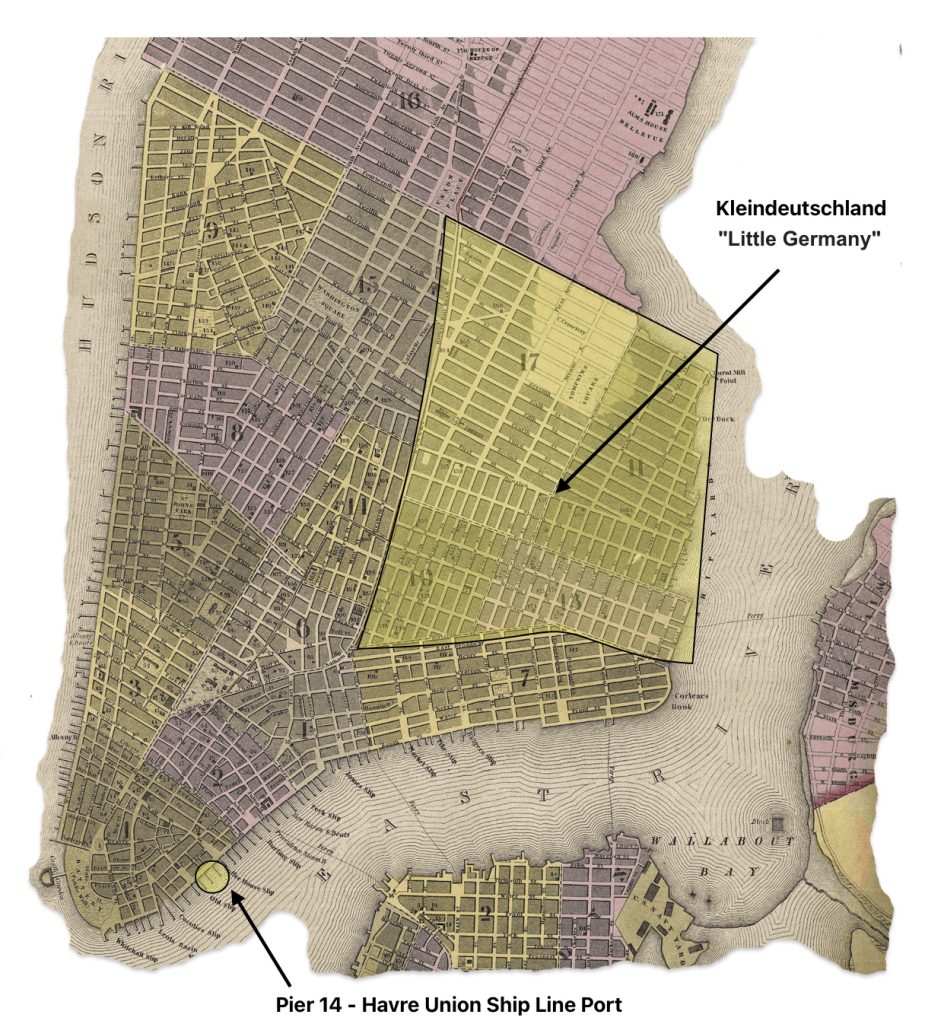

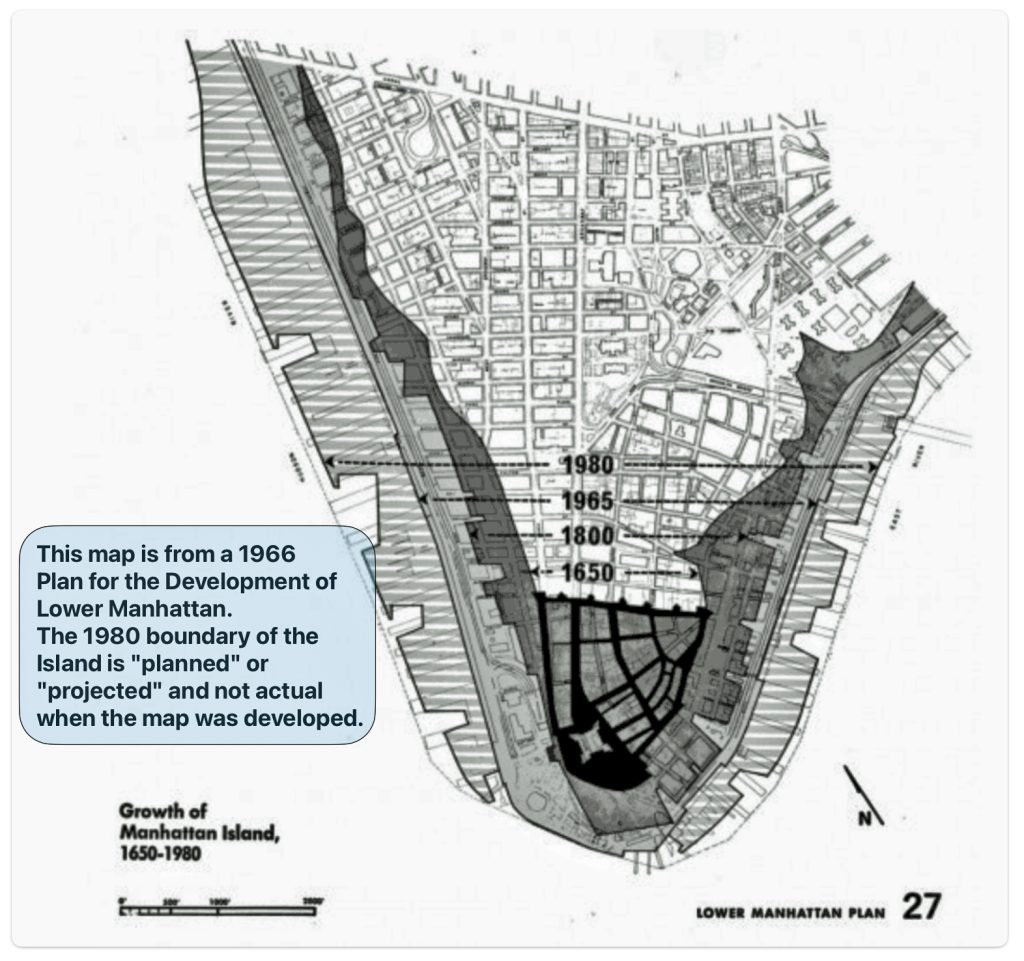

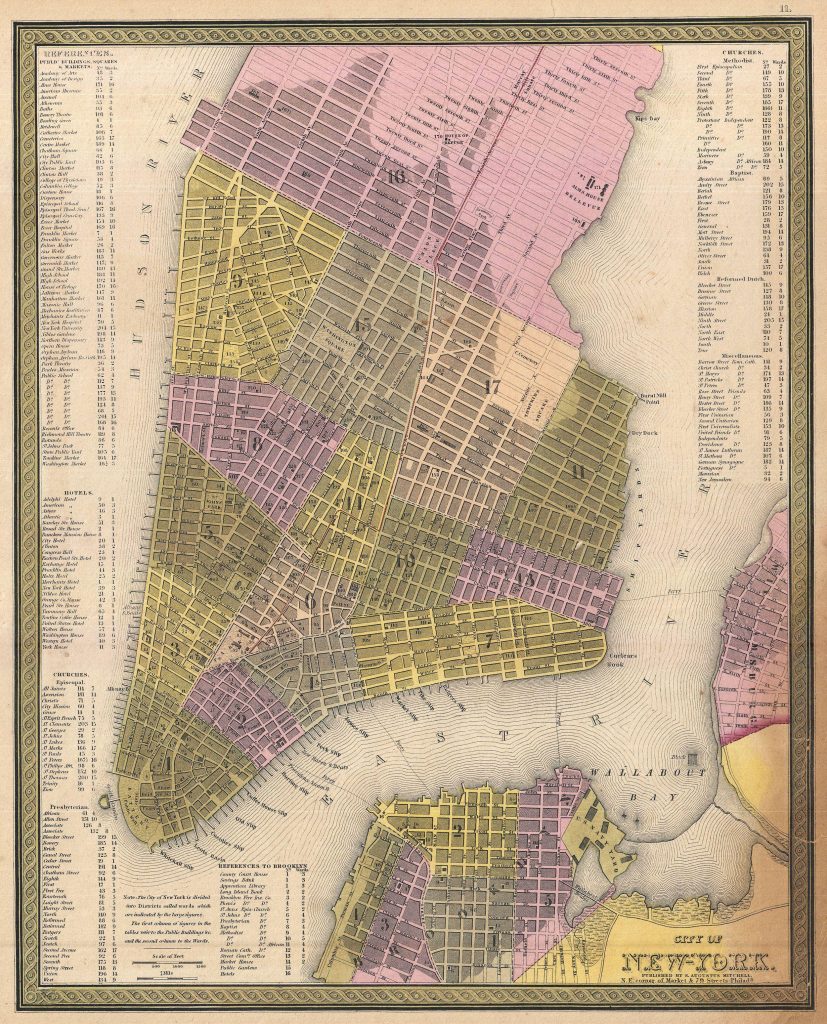

Johann Sperber arrived in New York City in the beginning of hot summer in 1852. Johann arrived at pier 14 on the lower end of Manhattan on the East River (see map one below).

An article from the New-York Daily Times published on July 27, 1852 vividly described an oppressive heat wave gripping the city at that time that Johann arrived in America. The article, titled “The Streets in Midsummer”, stated that “The sun mercilessly beats down upon them all day long, heating the stones to the temperature of frying-pans.”

“The Streets in Midsummer” is full of meticulous detail, social commentary, references to art and literature, and overwrought prose. (“Nor is it enough that a man’s juices are evaporated, and carried away in clouds perhaps, to tumble elsewhere in thunder showers, upon unconscious umbrellas.”)

The temperature peaked at 89 degrees in late July before the article appeared, and otherwise stayed in the mid-80s before dipping into the high 70s. This suggests the city in the summer of 1852 was experiencing extreme heat. [14]

Map one below indicates where pier 14 was in lower Manhattan. It also reflects the proximity of an area to the east of the piers where many German immigrants settled or stayed before they continued their journey.

Map One: Lower Manhattan New York City: Proximity of Kleindeutschland and The Havre Union Packet Ship Pier 14 [15]

From the 1830’s onward, New York city was the major port for the arrival of German immigrants. Germans that did not stay in New York city or its environs may have had plans to continue their journey further inland.

It is not known how long Johann Sperber stayed in New York City or possibly in other towns in New York state before he settled in Gloversville, New York.

Possible Scenarios and Awareness of Ecological Fallacies

There are a few possible scenarios that describe how Johann made decisions to ultimately arrive in Gloversville, New York and become a glove maker.

- With knowledge of his ultimate destination, he may have simply gotten off the ship and then headed north up the Hudson River to Albany and the Johnstown-Gloversville, New York area.

- He may have had a vague idea of heading to an area that past generations of Badeners from his home region established homes from prior migrations (the Palatine area around the Mohawk River). He may have stayed in Little Germany in New York City to gain additional information or work, to determine his next specific steps and possible economic opportunities.

- He may have had no idea of his next step. He may have stayed in New York city to gain a sense of what his next step would be and given a predilection toward adventure, was willing to try anything and make a new life for himself up north along the Mohawk river.

- He may have stopped at one or more intermediate places in between New York City and Johnstown.

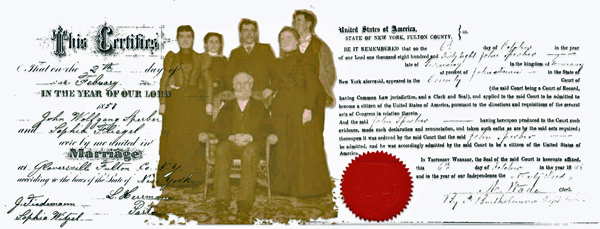

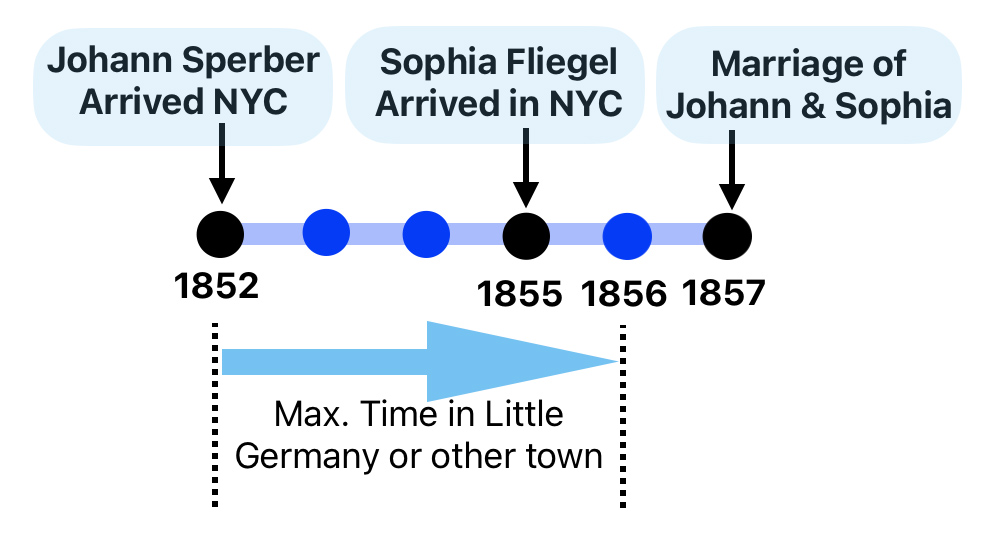

What we do know is Johann Sperber married Sophia Fliegel on February 2nd 1857 in Gloversville, New York. It is assumed that they met in Gloversville at least within a year before their marriage or sometime in late 1855. The Fliegel family arrived in January 1855.

I cannot find Johann Sperber in the 1855 New York census for Johnstown, New York or in the various Wards of New York City. As a single young man who probably was a boarder in a household, he may have eluded the census enumerator. The state census in Gloversville was taken in August of 1855 in Fulton county. I do not believe their marriage was arranged, so it is a question of how long their courtship was in in late 1855 and/or 1856.

Timeline for Johan and Sophia

This implies that Johann could have lived in New York City one to four years before traveling to Gloversville.

We do not have evidence on many of the specific actions and stages of life related to Johann Sperber. When attempting to provide possible scenarios of his journey to Fulton county, New York, one must guard against the ecological fallacy of inferring Johann’s individual experiences and characteristics to be necessarily associated with various German immigrant groups or group patterns.

An ecological fallacy is a logical error that occurs when inferences about the nature of individuals are deduced and made from inferences about the group to which those individuals belong. We need to guard against erroneously applying group characteristics of German immigrant groups to Johann who is also part of that group. It is a common error when making inferences from aggregate level data without examining individual-level data. [19]

Arriving in New York city could have been treacherous regardless of whether one had clear ideas of their next step when departing the ship.

“One of the greatest problems for the emigrants was arranging for their travel in the United States. On both sides of the Atlantic aggressive agents, called Makler in Germany and “runners” in the United States, hustled to sell railroad and canal tickets. They often misrepresented the actual cost, facilities and travel time, sometimes selling completely fraudulent tickets.” [20]

“The trials of the immigrant were by no means ended when he reached shore, for wherever he landed he was liable to fall a prey to the spoiler. Without the aid of friends who knew the snares that were set for him and understood the arts and wiles of the “bunco” men that lay in wait, he was fortunate if the first few weeks of residence in the land of hope and freedom were passed without the loss of a great part of his possessions including his health and freedom.“ [21]

“(R)unners” met the incoming ships, and by ingratiatory manners, deception, and false promises, sometimes even by seizing the baggage as it was landed, beguiled or forced the immigrants to follow them to the resorts they represented. It is a significant fact that most of the boarding-house owners and nearly all the “runners” were themselves foreign born, and they plundered most successfully people of their own race.” [22]

“Railroad agents and private ticket sellers also sought to influence newcomers. For instance the New York and Erie Railroad sold tickets for departures from the wharf so that docking passengers would not be able to change their minds and head in a direction not served by that line. Whenever an immigrant ship came into port, there was never a lack of hungry agents and runners who swarmed about peddling their services.” [23]

“Kleindeutchland” – Little Germany

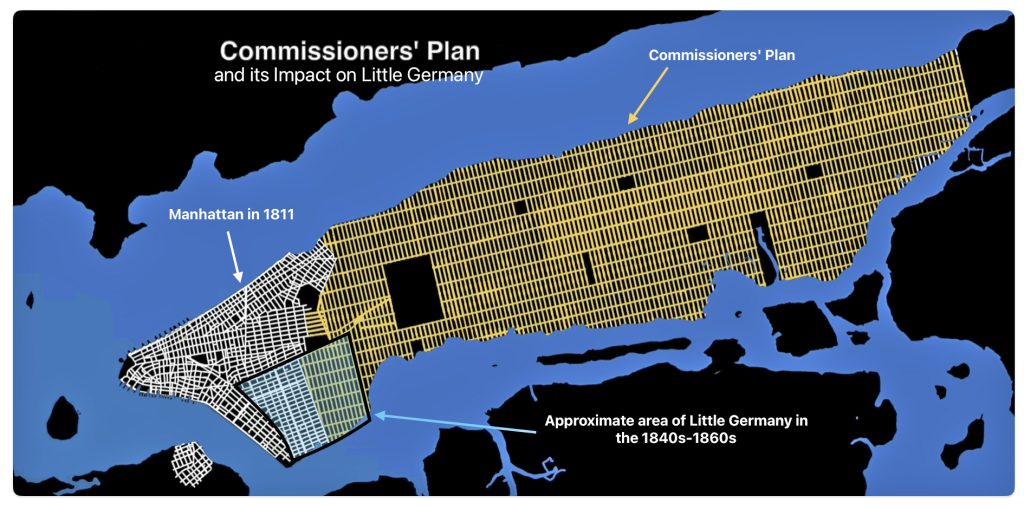

Only a relatively short distance from the pier 14 where the packet ships arrived from the Le Havre was an area on the east side of Manhattan where Germans started to settle in the 1840s. The area became known as “Kleindeutchland” or little Germany (see map one above). In the mid 1800’s, this area of New York City could more appropriately have been called the “Upper East Side” since it was the northern edge of the developed area of eastern Manhattan Island. [24]

“The entire area reaching roughly from Division Street in the south to 14th Street in the north, and from the Bowery in the west to Avenue D in the east became a thriving center of German-American life and culture in the mid- to late 19th century – not only for New York City, but also for the country.” [25]

Many of the German immigrants who came during this time period, notably those who landed in New York City, settled down to live their lives on the Lower East Side of New York City. Beginning in the 1840s, large numbers of German immigrants entering the United States provided a constant population influx for “Little Germany”. Other German immigrants used this geographical ethnic enclave as a launching pad to find a spouse, establish social networks or gain information and resources to make plans to travel further west into the United States for jobs or land.

“Between 1855 and 1880, Vienna and Berlin were the only cities with a larger German population than New York. Together they constituted the three capitals of the German speaking world.” [26]

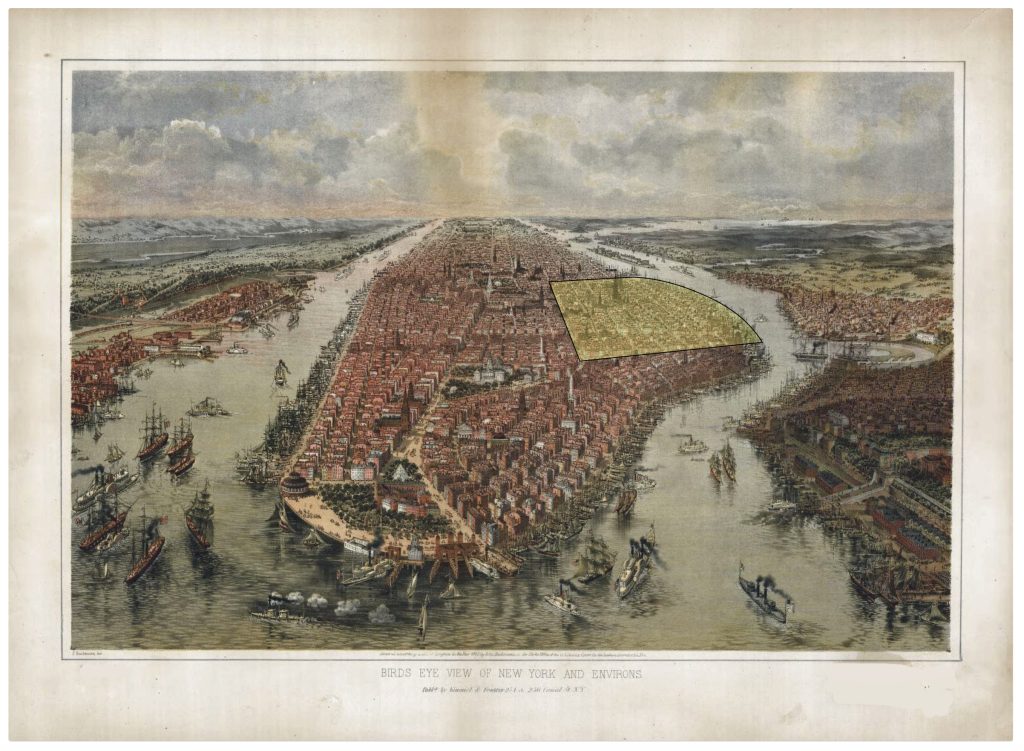

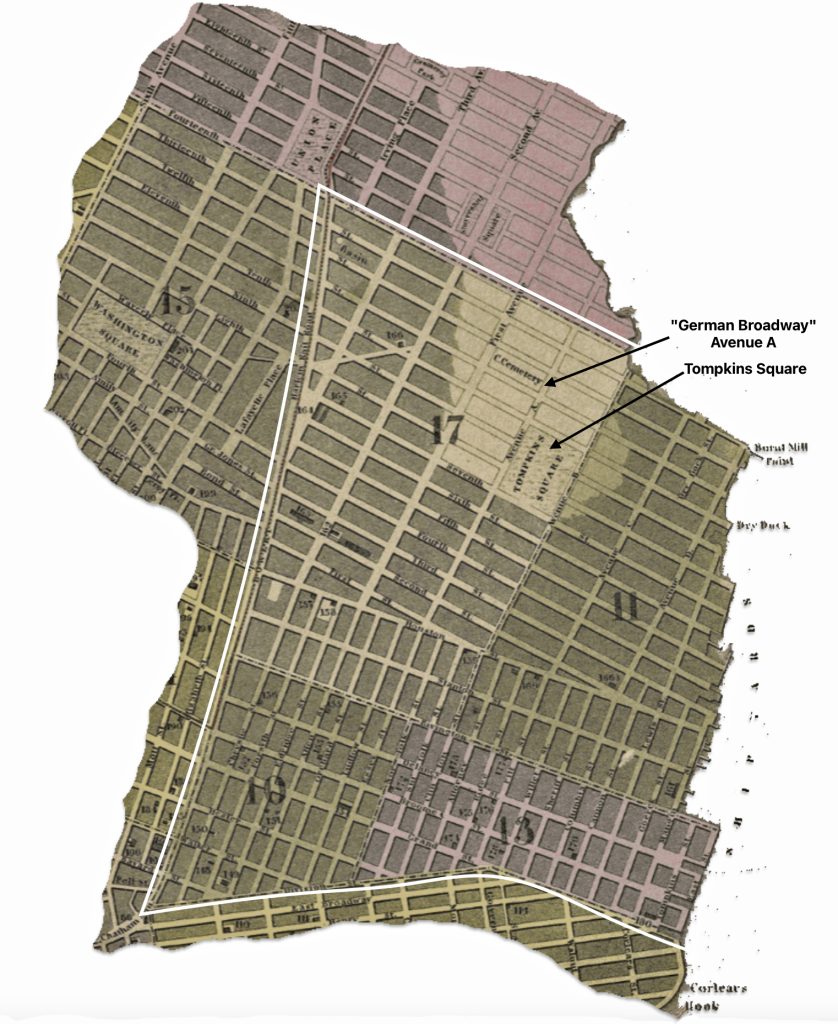

Map two below provides a ‘bird’s eye” view of where Little Germany was located in lower Manhattan. Although the map was created thirteen years after Johann’s arrival and a few buildings and docks may have changed in the environment, it gives a sense of the size and location of Kleindeutchland. I have highlighted the approximate area that encompassed Little Germany. [27]

Map Two: Bird’s Eye View of Little Germany in New York City

“By 1855, New York City, then consisting only of Manhattan, was the third largest “German” city in the world, after Berlin and Vienna, and by the 1870s it has been estimated that roughly 30 % of the population of New York City was made up of German immigrants and their American-born offspring. The core of that population lived in Kleindeutschland, the German cultural capital of the United States.” [28]

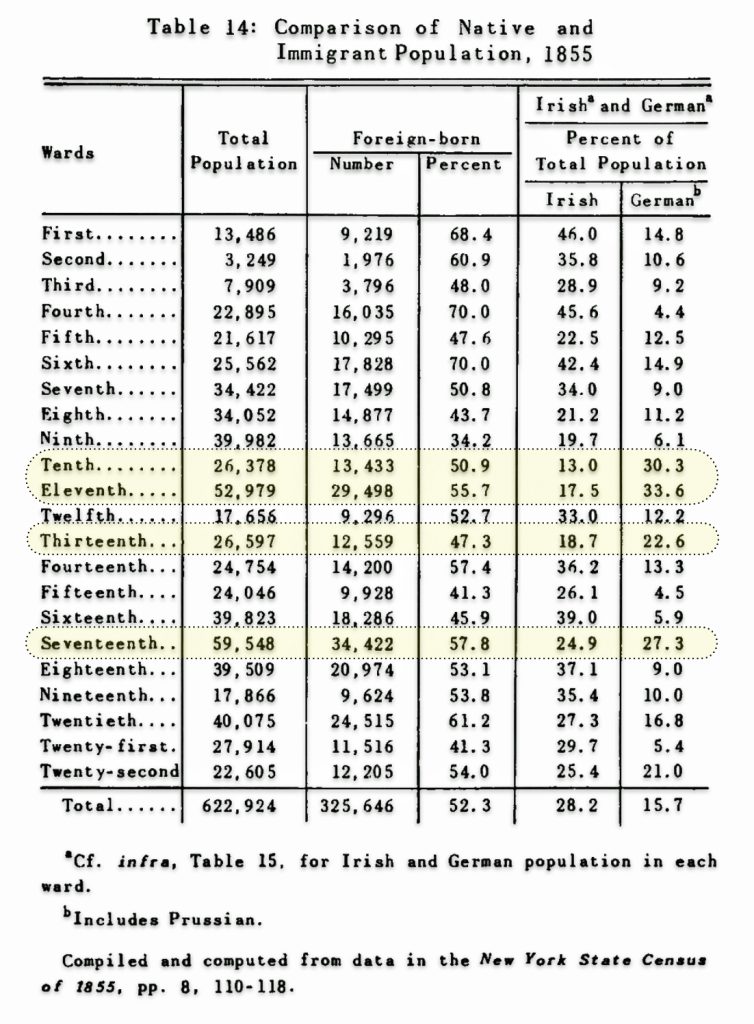

Kleindeutschland was composed roughly of the 10th, 11th, 13th, and 17th Wards of Manhattan. The 11th and 17th wards were the upper wards bounded on the south by Rivington Street, which were developed primarily through the arrival of these German immigrants. This area was not purely German, but the ‘Teutonic culture’ dominated in most parts. Wards four, five and six, which are contiguous and southwest of Little Germany, were areas that were predominately inhabited by Irish immigrants.

“The most densely Germanic area in terms of residents was the area around Tompkins Square Park, especially extending to the north and south. Avenue B, due to its importance as a commercial center, was sometimes referred to as German Broadway – Yorkville wouldn’t usurp the title for another few decades – and Avenue A rivaled it in importance simply as the main artery through the heart of the community. A bit further west, on and in the vicinity of the Bowery, were many of the important German social and financial institutions as well as places of recreation such as beer halls, theatres, and other attractions.” [29] See map three below.

Map Three: A Close Up of The Four Wards of Little Germany

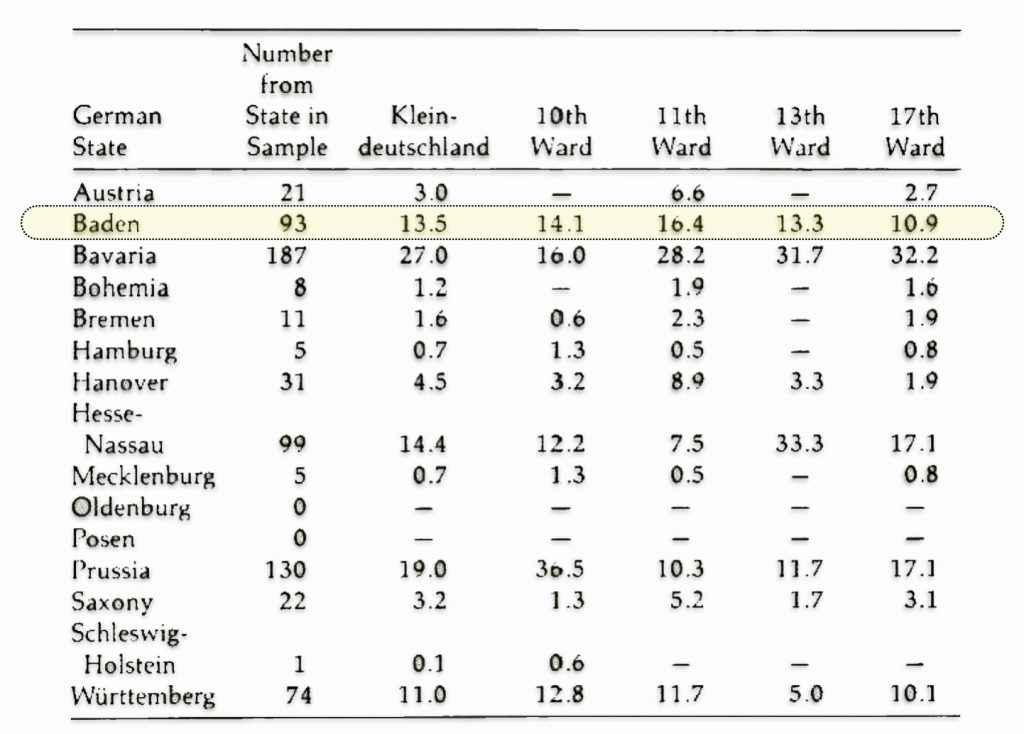

If Johann Sperber stayed in Little Germany before he embarked for the upper New York state, he may have resided in any of the four wards of Kleindeutschland. Badeners and Wurttembergers seem to have been fairly evenly spread throughout the four wards in the earlier years with no major concentrations. [30]

Table One: Relative Concentrations of Immigrants from the German States in Kleindeutschland and Its Wards in 1860 [31]

As time went on Germans tended to cluster more than other immigrants in New York City, such as the Irish. Germans from particular German states had a tendency to live close to each other.

- Grand Duchy of Baden: Johann Sperber’s fellow countrymen, the Germans from Baden, were found in all wards of Little Germany.

- Kingdom of Prussia: The Prussians were most heavily concentrated in the city’s Tenth Ward.

- Province of Hesse-Nassau: Germans from Hessen-Nassau tended to live in the Thirteenth Ward and in the 1860s and in the ensuing decades moved northward to the borders of the Eleventh and Seventeenth Wards.

- Kingdom of Württemberg: Germans from Württemberg began by the 1860s to migrate northward into the Seventeenth Ward.

- Kingdom of Bavaria: The Bavarians (included Palatines from the Palatinate region of western Germany on the Rhine River, which was subject to the King of Bavaria), was the largest group of German immigrants in the city by 1860. They were distributed evenly in each German ward except the Prussian Tenth.

- Kingdom of Hanover: Germans from Hanover constituted a small group and had a strong sense of self-segregation forming their own “Little Hanover” in the Thirteenth Ward.

Although there was self-segregation according to homeland state, there were interactions between Germans of various states and with other immigrant groups in the neighborhood. Bavarians displayed the strongest ‘regional bias’ mainly toward Prussians. The most distinctive characteristic of their settlement pattern was that they would be found wherever the Prussians were fewest. [32]

While the neighborhood was called Kleindeutschland or Little Germany, the wards were not entirely German. Depending on the year canvassed, each of the wards ranged between 33-60 percent of the population as German born. The four wards combined were 65 percent German by 1875. Houses were two to four stories tall, often with a store on the ground floor and/or a workshop in the back, made of wood, stone or brick, and usually with a rear yard for toilets, laundry space, and a kitchen garden. [33]

In the mid-1850s, the tenth and thirteenth wards, retained an early character of urban architecture consisting of wooden frame structures as opposed to the emergence of newer masonry structures. Buildings tended to cover only a small portion of their lots. Each block was ‘a jumble’ of buildings and a maze of alleyways. Industrial workshops were generally tucked away on internal courtyards.

“Alleyways led into the interiors of the blocks, which were filled with the workshops and factories that accounted for 64 percent of the manufacturing establishments in the built-up portion of the city (and 57 percent of the manufacturing establishments in all of New York City).” [34]

The demographics of New York’s settlers had an impact on the city’s make-up as well. Skilled labor would stay in New York City if jobs were available or began to use New York merely as a gateway, staying for a few months before moving to homesteads in outlying areas or the Midwest. Immigrants that stayed in New York city tended to stay in areas close to where they worked. Walking was virtually the major mode of transport available to the immigrant population.

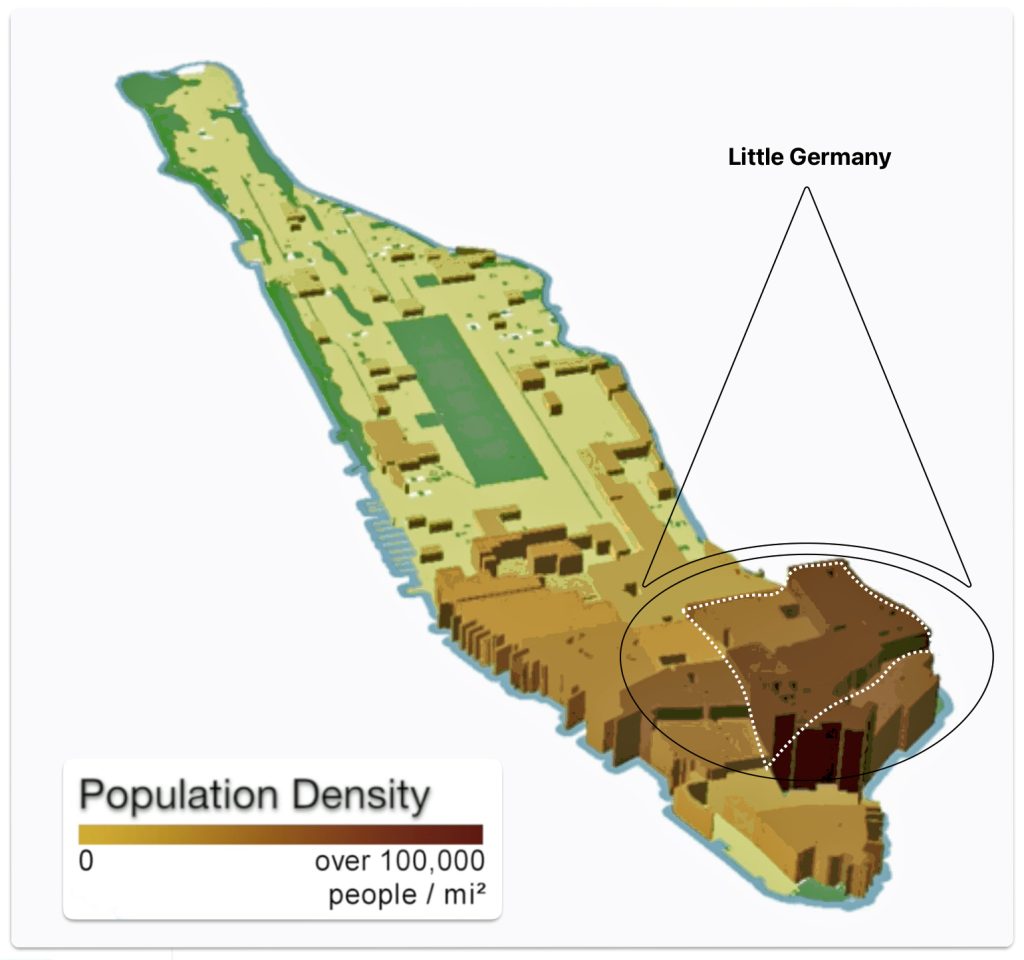

Map four provides a three-dimensional (3D) map showing population density in Manhattan in the year that Johann Sperber arrived in America. The map visualizes population density data in a 3D format, with height representing the number of people living in each area. I have outlined the area that comprised Little Germany in the map. The 3D rendering makes dense population centers visually stand out. Little Germany contained some of the highest density areas in New York City in 1852.

Map Four: Three Dimensional Population Density in Manhattan 1852

Between 1800 and 1910, density in urban Manhattan tripled from 200 to 600 people per hectare. A hectare is larger than an acre of land. One hectare is approximately 2.47 acres. The area known as Little Germany, which is now called the East Village, was significantly more dense than the average population density in the city, approaching 1,200 people per hectare.

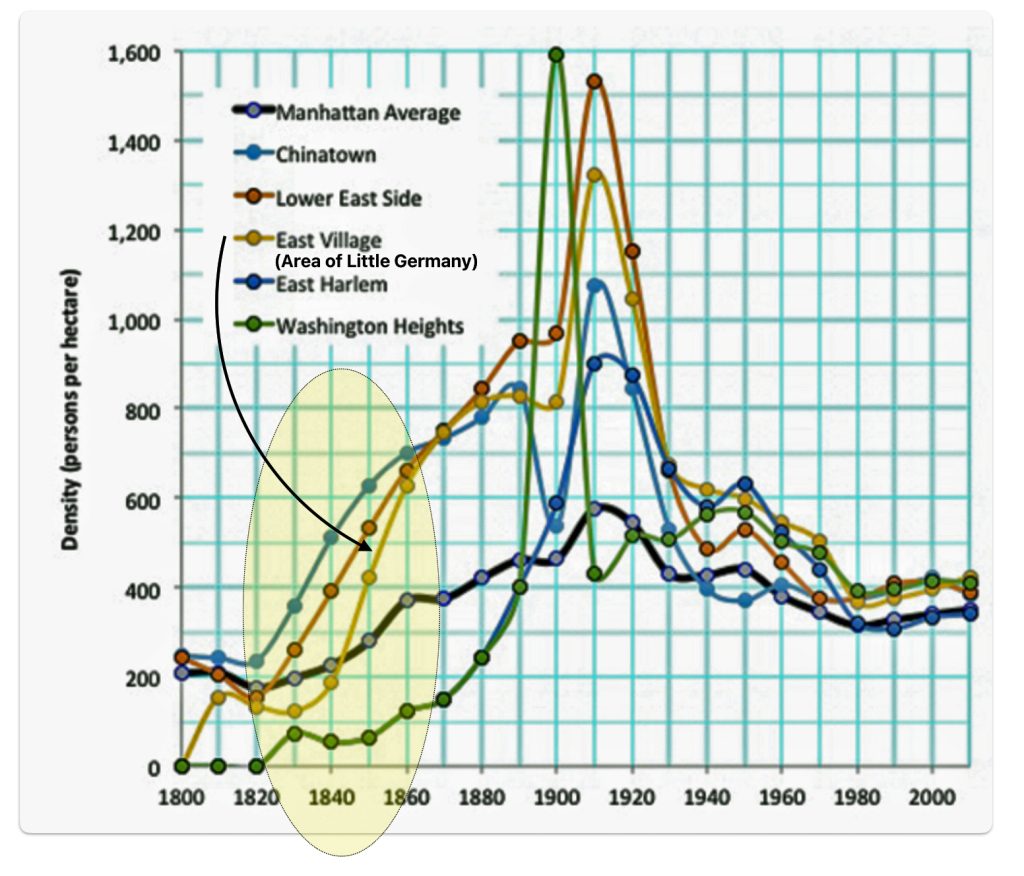

As reflected in graph one, the density of Manhattan remained stable at approximately 200 persons per hectare from 1800 to 1840 but then it began to steadily climb. The area (modern day East Village) which was Little Germany in the 1800s, experienced a rapid increase in population density between 1840 and 1860. Little Germany’s density increased three-fold from roughly 200 people per hectare to 600 in 1860. When Johann arrived in New York City, the density of Little Germany was roughly 500 people per hectare.

Graph One: Density in Manhattan Neighborhoods

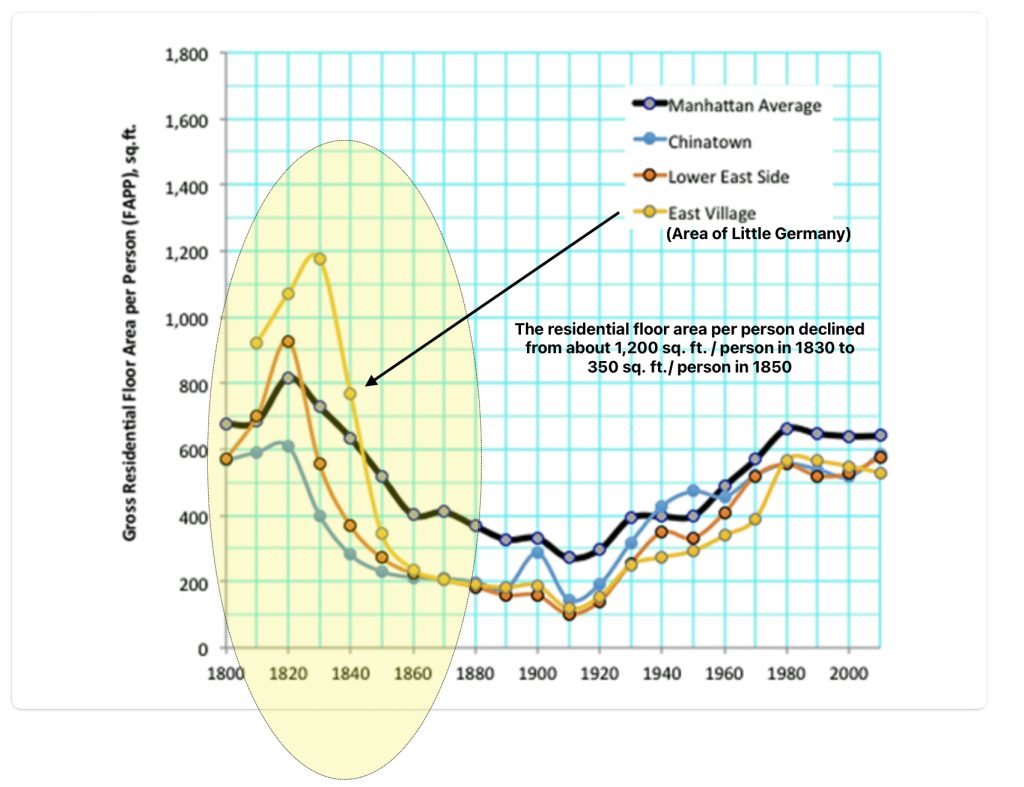

As indicated in graph two below, during the same time, Germans living in Little Germany experienced a drastic reduction in their respective living areas. The floor area per person in Little Germany declined seventy percent from about 1,200 square feet per person in 1830 to about 350 square feet per person in 1850. This was well below the average of 500 square feet per person.

Graph Two: Residential Floor Area per Person in selected Manhattan Neighborhoods [35]

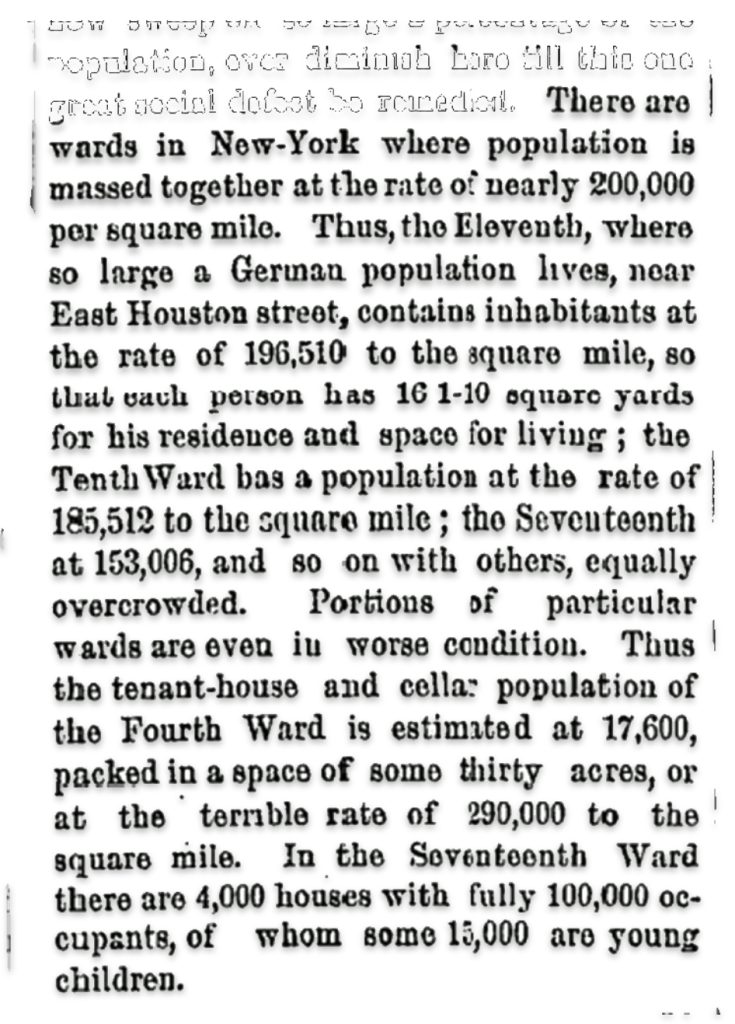

After Johann’s departure from the area, the living space in Little Germany continued to decline but at a less drastic rate to 200 in 1860. As population sky rocketed and living space did not increase at a commensurate rate, politicians, reformers, and scholars were seriously concerned with living conditions, notably in Little Germany, in the city’s crowded neighborhoods during this period. This is reflected in an opinion piece in the New York Times in 1876.

New York Times Article – Over Crowding in Tenement Houses in 1876

The river districts of the eleventh and thirteenth wards contained some of the world’s leading shipyards. The Eleventh Ward was also the major slaughterhouse district, where more than half of the hogs in New York city were slaughtered. [36]

The thirteenth ward, compared to the other wards, had more and heavier industry. Artisans’ workshops gave way to small and medium sized factories. Some of these factories produced the same products as the artisans’ workshops and furniture factories predominated. Other factories operated on a larger scale such as a fire brick manufacturer with forty employees. [37]

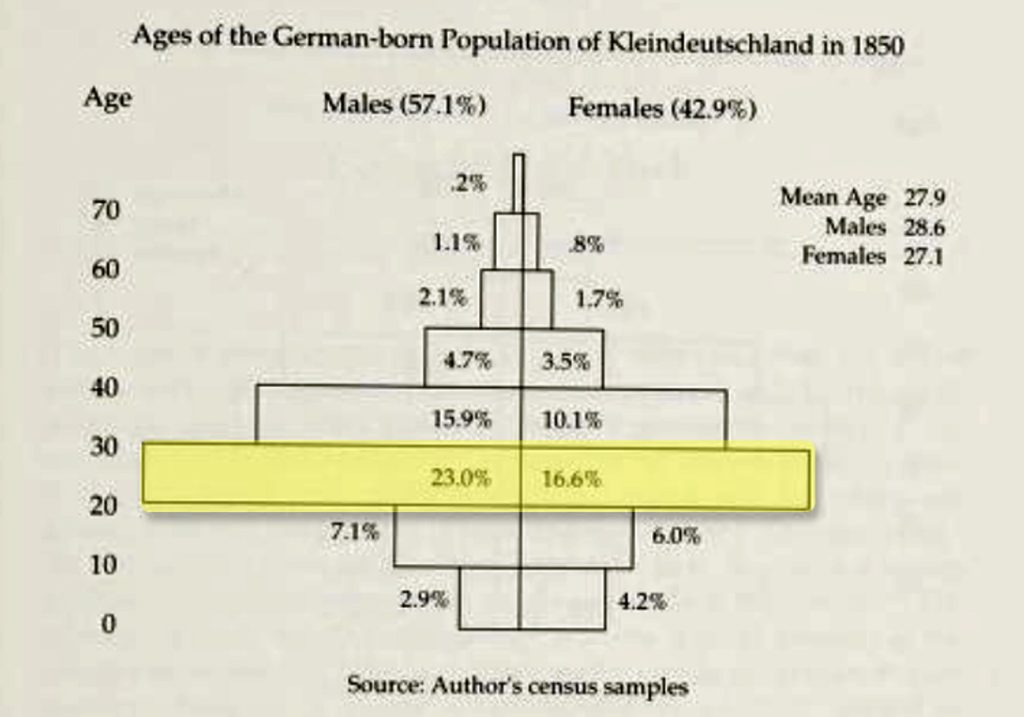

Johann Sperber fit the ‘archetype’ example of ‘the German immigrant in New York city in the 1850s’: a young single German male in his 20s. In 1850, two years prior to his arrival, 66 percent of the German immigrants in little Germany were in their twenties and thirties, as reflected in the distribution chart below. In addition, the male to female ratio was 61 : 39 in 1850, indicating a heavy predominance of single males. [38]

Graph Three: Ages of German Born Population in Kleindeutschland in 1850

There were many young men arriving from various German states in New York city. All looking for work and perhaps a potential spouse to start a family and a new life. Little Germany offered job opportunities and an effective mesh of social networks for gaining information on possible job opportunities in Little Germany and other areas where Germans were migrating.

When Johann reached America, he landed in a city that had a wide range of employment opportunities in a wide range of occupations. He may have stayed in Kleindeutchland and worked in one of the many occupations that Germans were employed in the four wards in New York City. He may have stayed in a shared living space with other single men to earn a sufficient amount of money to pay for transportation costs to the Mohawk Valley.

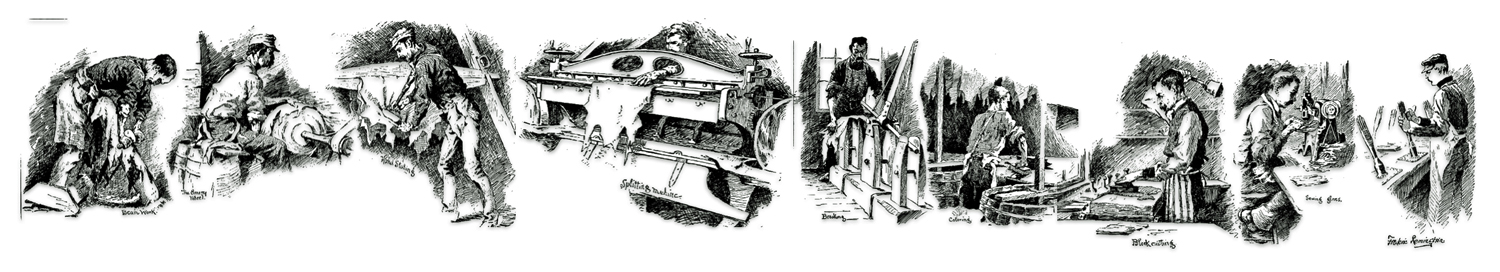

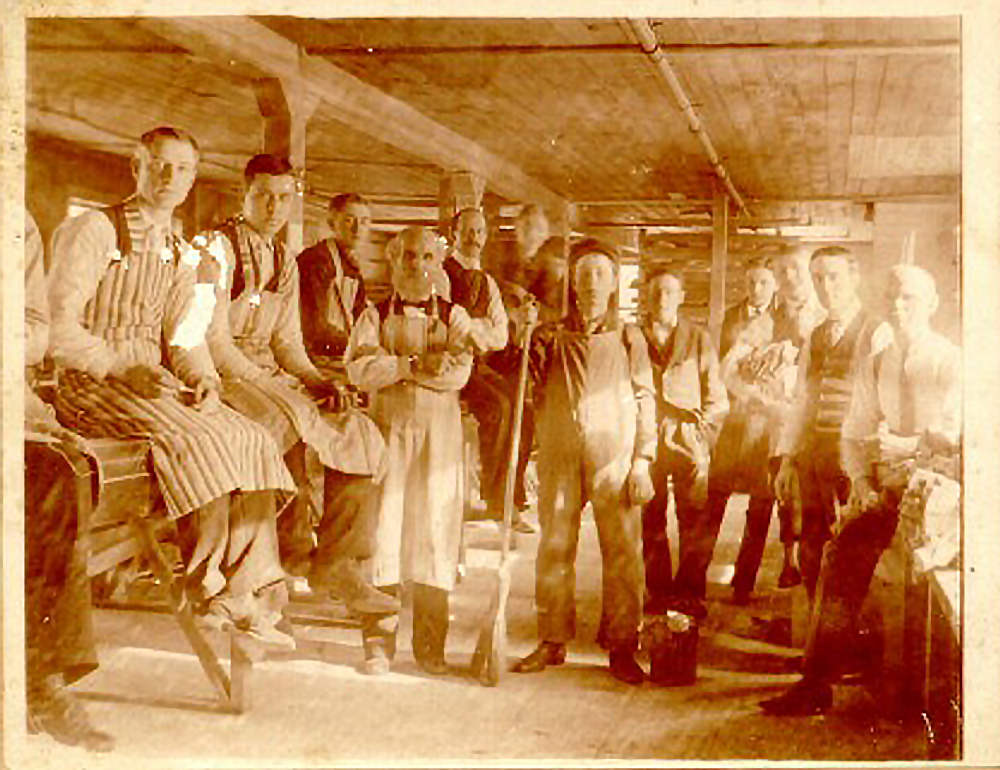

As stated in part four of this story, leather tanning and glove making were not novel artisanal activities in Europe. The various stages of the leather tanning and glove making profession and trade had an established history in various European countries.

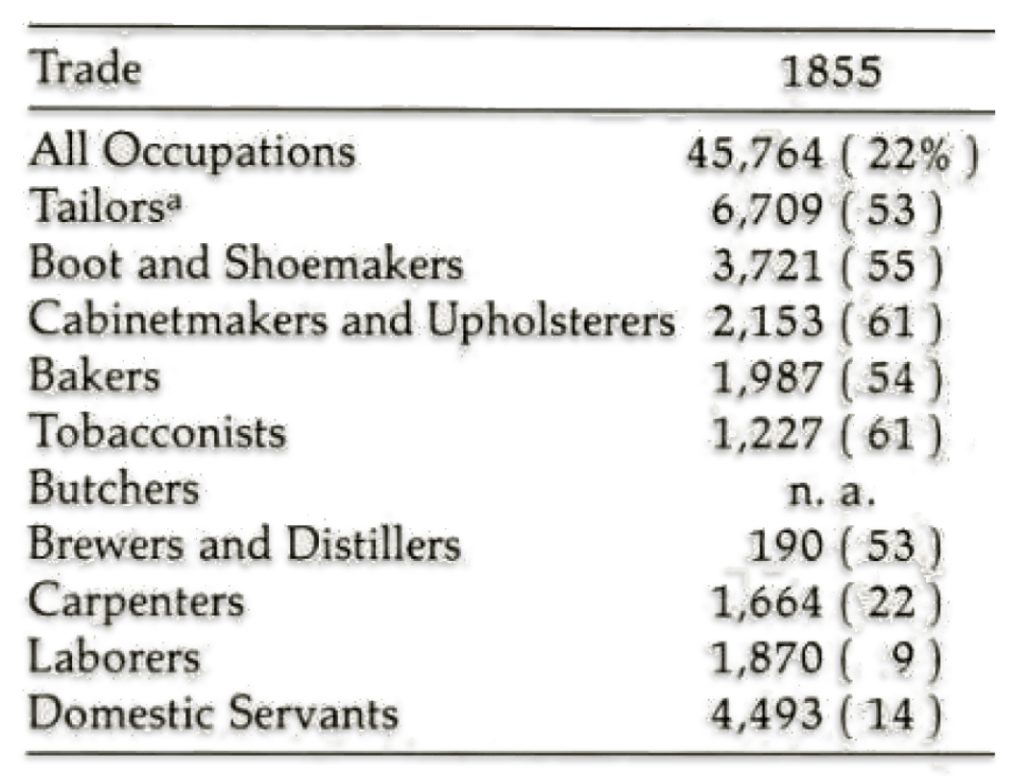

Jobs in “Kleindeutchland“

“The immigrants did not merely enter the economy as isolated individuals – they colonized it. At first the Germans dominated a few trades; then many trades, entire industries, and even whole sectors of the economy became German in character. … (T)he economy of Kleindeutschland evolved and became the basis for a German-American class structure, in which German factory workers and shopkeepers were flanked by a German criminal underclass and by German captains of industry.” [39]

Most of the occupations that Germans dominated were skilled trades or related to the distribution of food and dry goods.

“Some occupations were already German preserves, with Germans accounting for more than half of their practitioners. While many of these were small, specialized trades like furriers and brewers (with fewer than three hundred practitioners each in 1855 ), other German-dominated trades had thousands of members.” [40]

The following data in table two reflects the distribution of German born in selected occupations and trades three years after Johann Sperber arrived in New York City. There were other occupations in 1855 where the Germans were the largest ethnic group even though they were not a majority, for example, food dealers (3,045 Germans), peddlers (941 Germans), and musical-instrument makers (324 Germans).

Table Two: Numbers of German-born Workers in Selected Trades in New York City – 1855 and the Percent German-Born in Each Trade

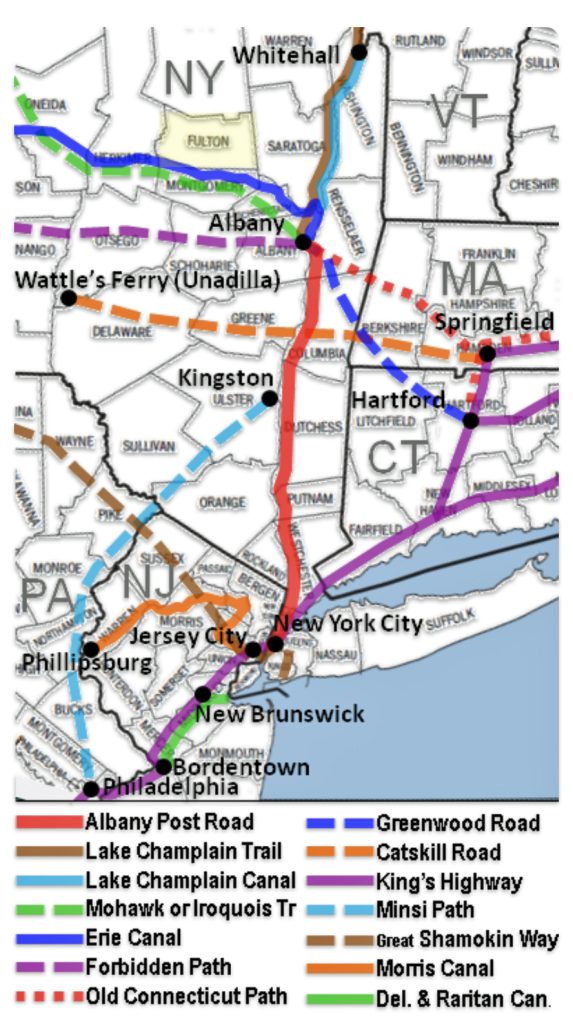

Transportation to the Mohawk Valley in the 1850s

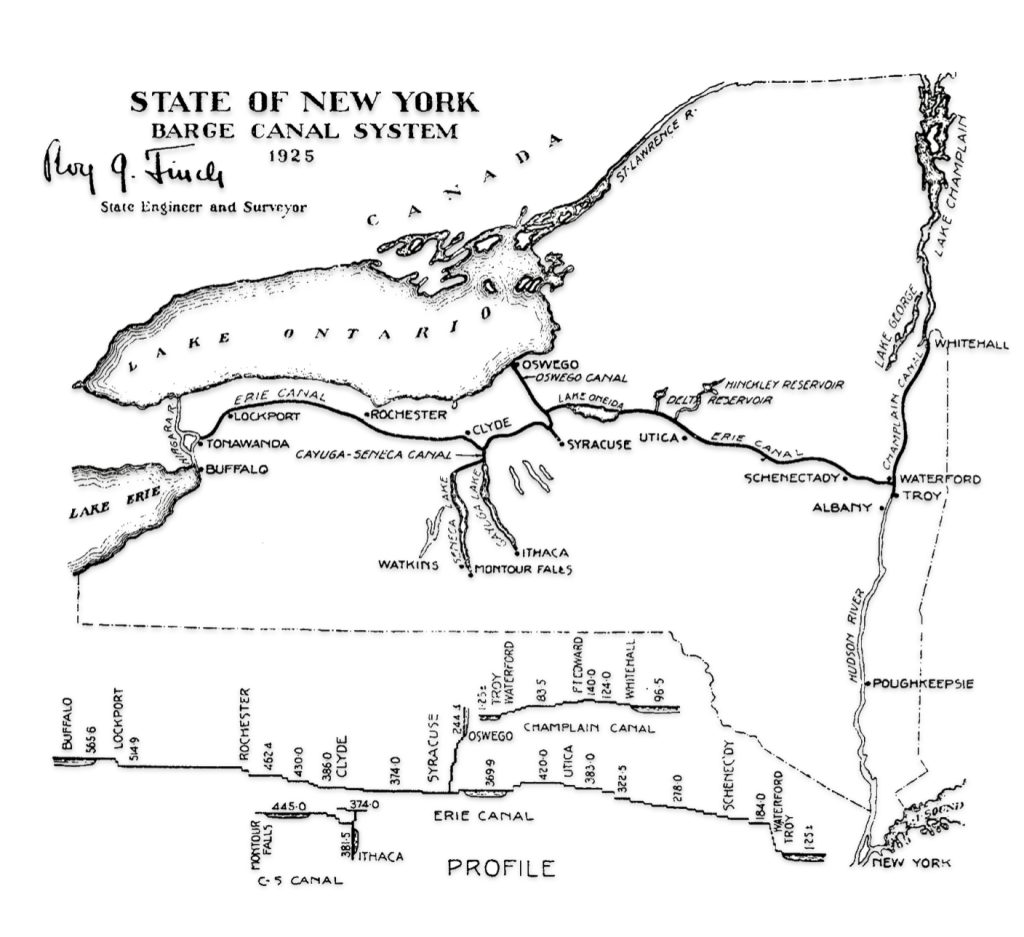

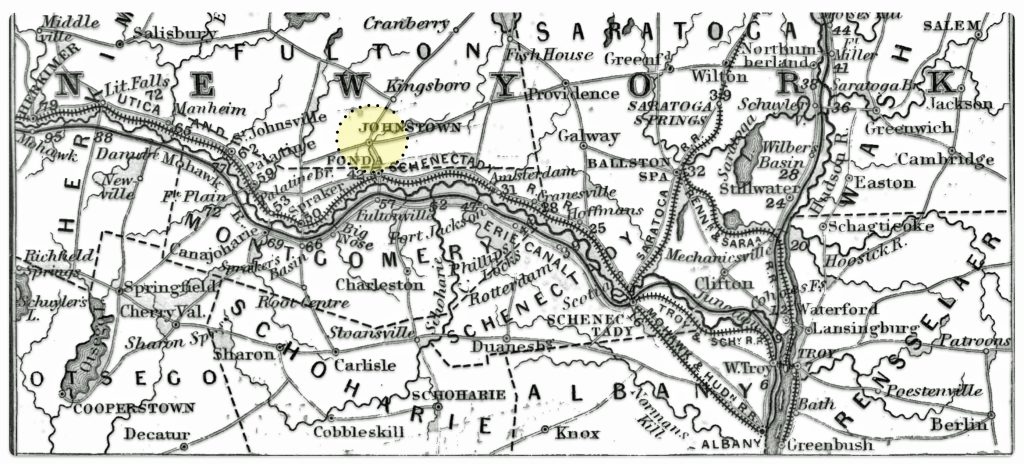

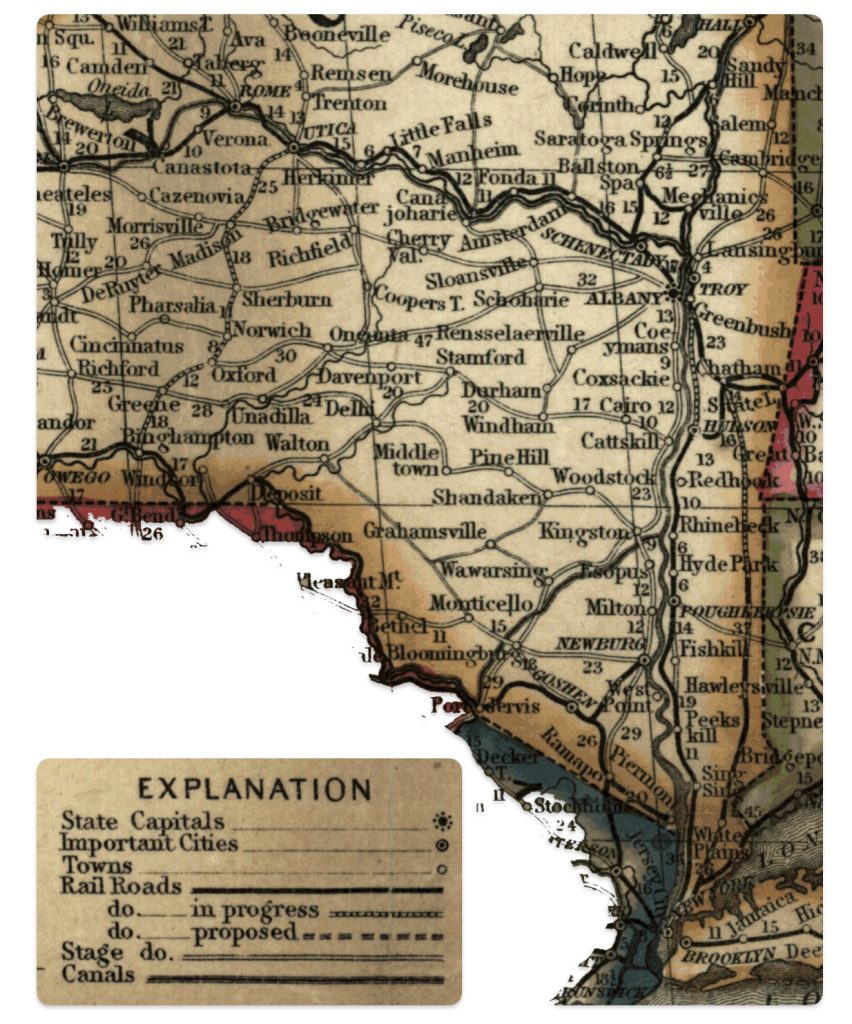

Between 1852 and 1856, Johann had a number of options to reach the Mohawk Valley from New York City.

- Roads: Stage coaches or wagons on the Highlands Turnpike or portions of the Albany Post Road to the capital area (Albany-Troy-Schenectady) could be utilized to make the trip northward. He then could have traveled west on roadways to Gloversville and Johnstown.

- Waterways and Roads: In the non winter months, steamboats traveled frequently on the Hudson River between New York City and the Albany area.

- Railways: Johann could have utilized the railway networks that recently linked New York City and the capital area. Once in Schenectady, Albany or Troy, he had an option to travel by rail following the Mohawk River and Erie canal to Fonda. The remainder of the short distance to Gloversville could be traveled by road.

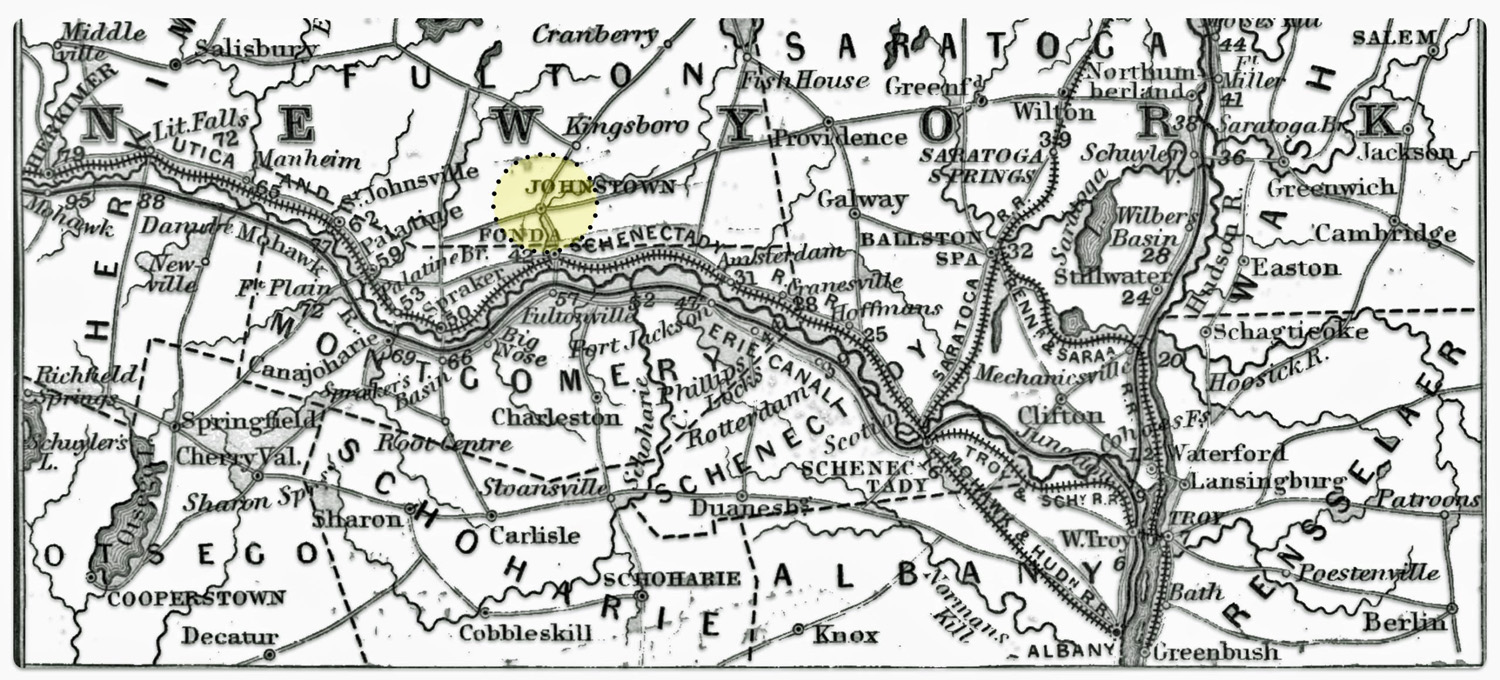

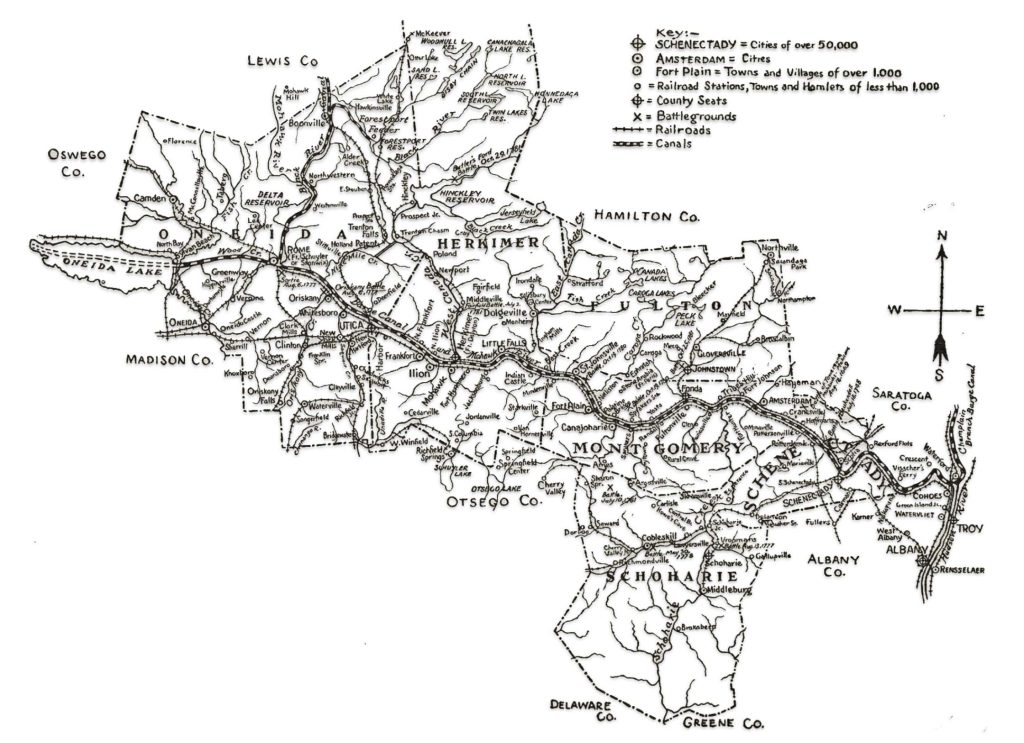

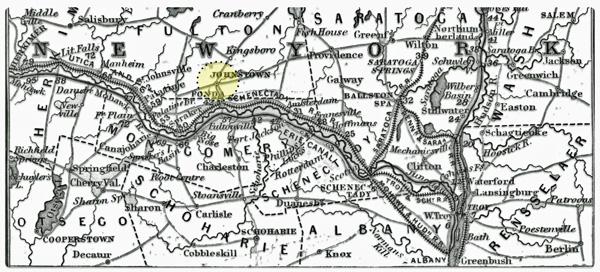

Map five was published in 1853 but was created in 1848. It is the best map that I could find that depicts the transportation networks of road, rail and water that existed when Johann was traveling to the Mohawk Valley. As reflected in map five, there were a number of options. Gloversville and Johnstown are not on the map. However, you can locate Fonda, New York that is located on the rail line that mirrors the Mohawk River. Fonda is west of Amsterdam and east of Canajoharie. Johnstown is about six miles north of Fonda.

Map Five: Railroads, Canals, and Stage Roads Surrounding Hudson and Mohawk Rivers

Source: Modified map from Drake, Ira S, and Cowperthwait & Co Thomas. Mitchell’s new traveller’s guide through the United States, showing the rail roads, canals, stage roads &c. with distances from place to place. Philadelphia, Thomas, Cowperthwait & Co., 1853, created 1848. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/gm70005367/

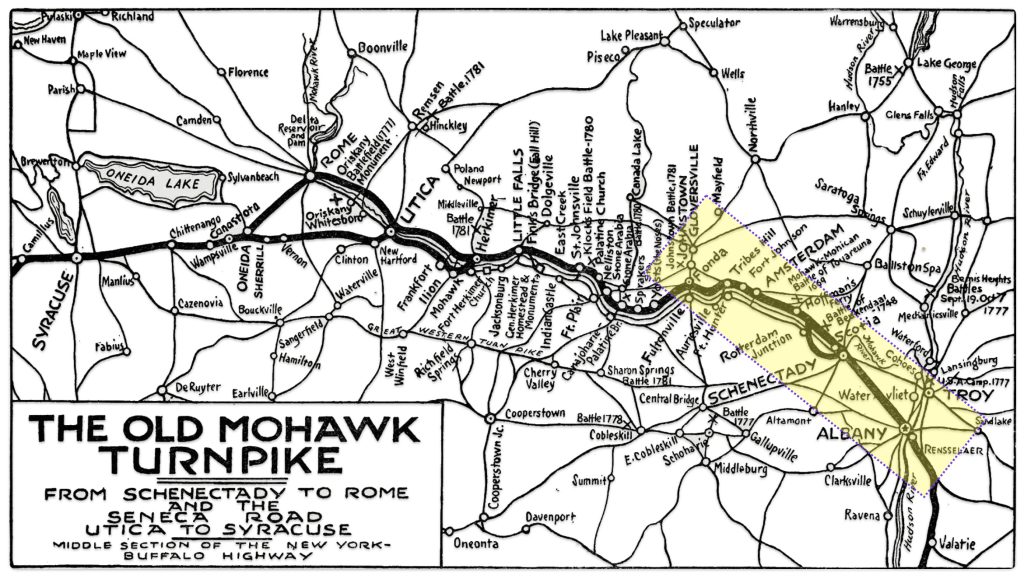

Map Six provides a graphic depiction of the major roads that Johann may have utilized to get from the capital district area of Troy and Albany to Gloversville.

Map Six: The Old Mohawk Turnpike

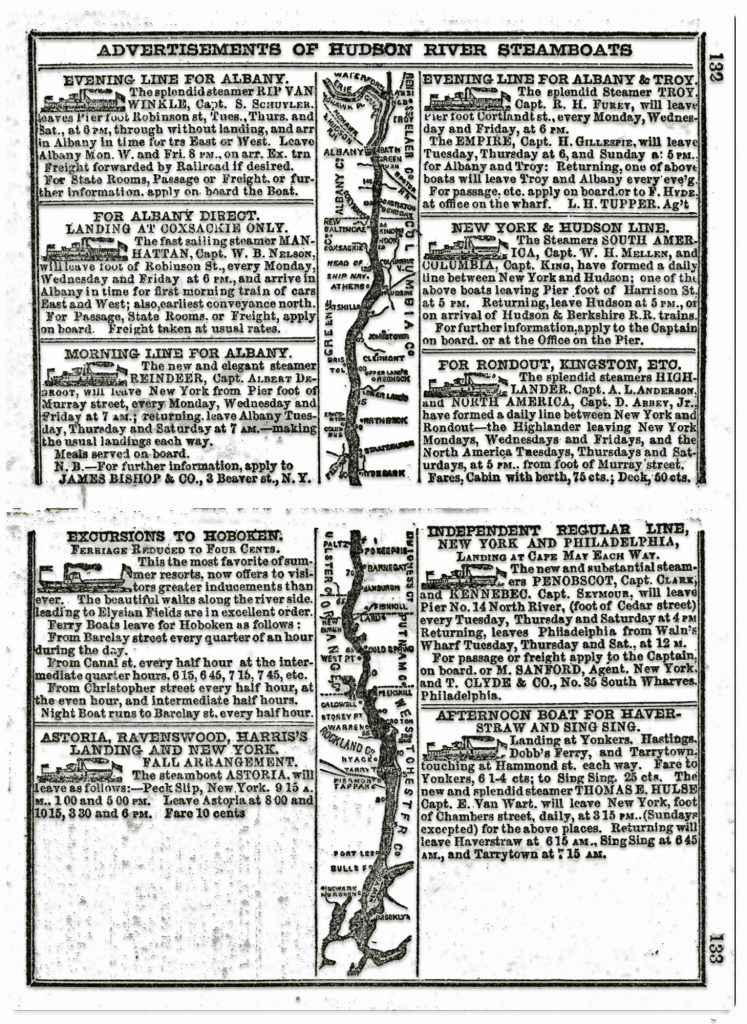

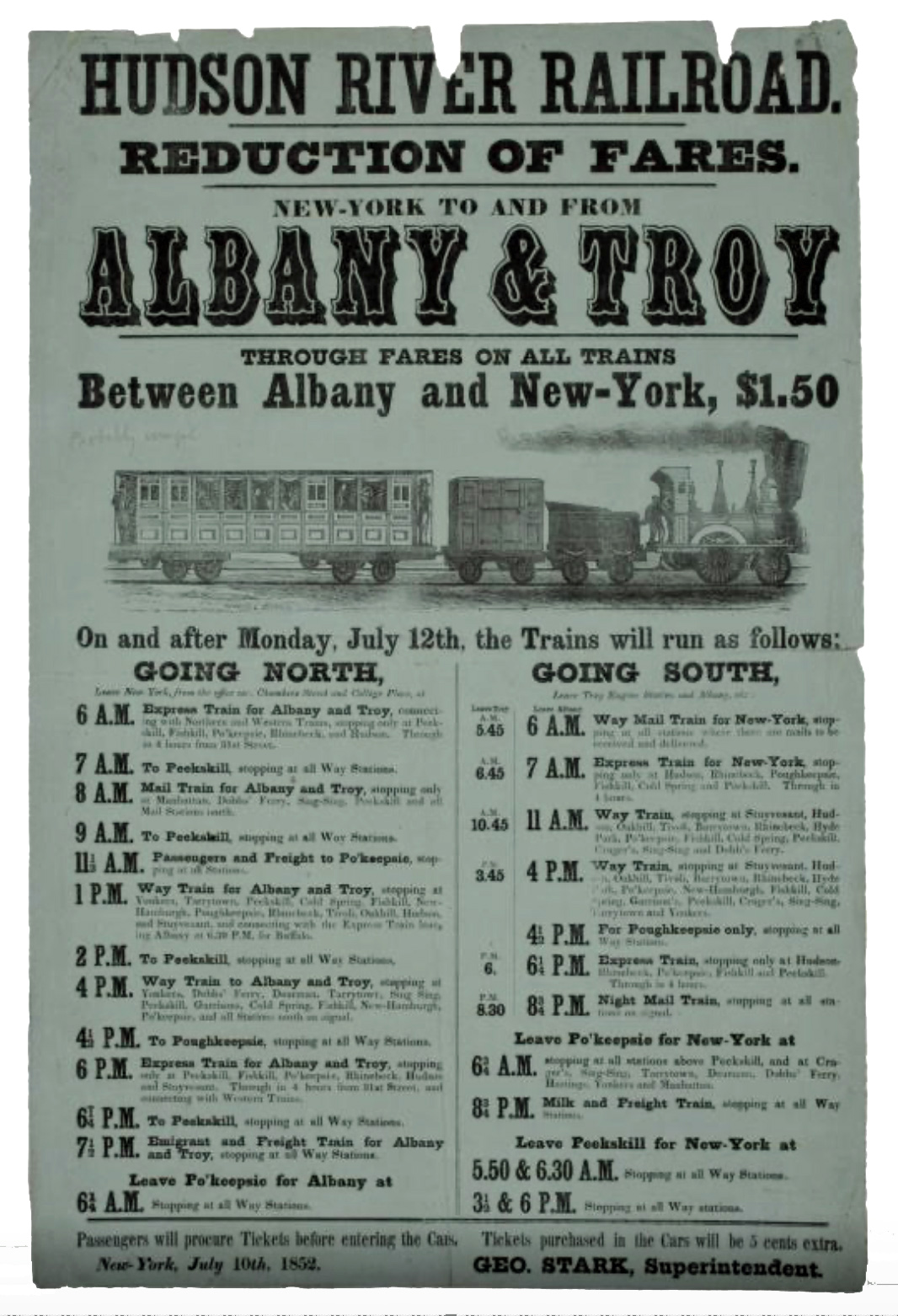

The entire length of the Hudson River is three hundred and twenty-five miles. Ships could ascend the river as far as Hudson, one hundred and fifteen miles. Steamboats and sloops could reach to Albany and Troy, which was about 143 miles, as reflected in the following advertisements around 1851. [41]

Hudson River Day Boats Between New York City and Albany

Another advertisement, published in a travel guide (see below) in 1851 indicates the prevalence of various Hudson River steamboat lines that traveled between New York City and the capital areas of New York state around the time of Johann’s arrival to America.

Advertisements for Hudson River Steamboats

The biggest difference between steamboat and overland road travel was money and time. Overland travel took significantly longer than steamboat travel. Steamboats could travel fifty to one-hundred miles a day against the river’s current, but stagecoaches and wagons traveled only seven to twelve miles. Stagecoaches often moved slower because they had to change horses, and road conditions and weather also caused delays. Steamboat passengers usually paid less than overland passengers due to supply and demand. A greater supply of steamboats existed, all offering the same accommodations to passengers, so competition kept the prices low. [42]

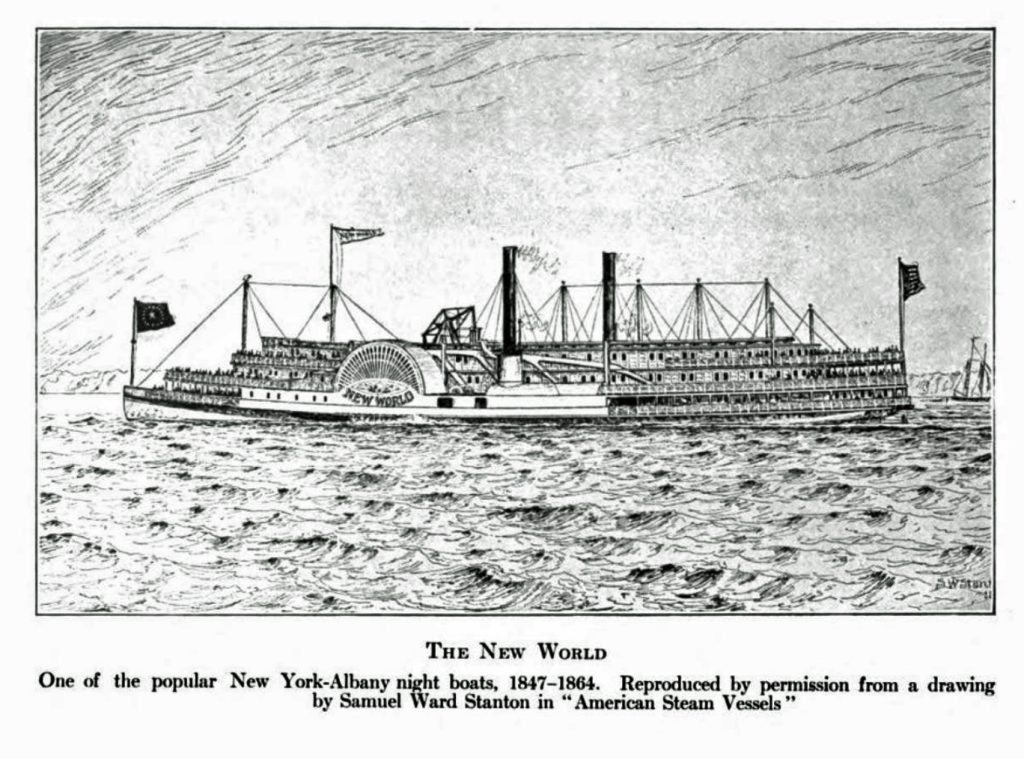

Steamboats began their domination of Hudson River travel after Robert Fulton’s North River (often referred to as the Clermont) traveled from New York City to Albany in 1807 in a record 32 hours. Hudson River steamboats were called ‘sidewheel steamers’. They were unique in that they had two paddlewheels located in the center of the boat on either side. In contrast, Mississippi River steamboats have single, wide paddlewheel at the rear or stern of the boat. [43]

By the 1820s, steamboats on the Hudson were a common sight, running at night as well as during the day. Night boats became popular with businessmen traveling between New York City and Albany, who could travel first-class and arrive well-rested in the morning. While many of the steamboats afforded travel amenities for the emerging middle class, immigrants could obtain cheaper fares in steerage and on older and slower steamboats that were used for freight and steerage. [44]

In 1819 there were only nine steamboats in operation on the Hudson River. By 1840, there were more than 100 in service. By the 1840s, steamboat travel was the easiest and fastest method of transportation in the Hudson Valley. The trip from New York City to Albany took about 10 hours and 30 minutes. [45]

The Steamboat The New World on the Hudson River

“Each succeeding steamer cut down the time of the passage. In 1817, it had been reduced to eighteen hours and in 1826 the Constellation and Constitution had made the trip to Albany in fifteen hours. By 1836 a new boat, the North America, had cut it down to ten hours and the improvement went steadily on … . “ [46]

Table three reflects the ongoing ‘race’ between commercial steamboat enterprises for the distinction of having the fastest boat on the river. As reflected in the table the travel time for the fastest steamboats on the Hudson River were significantly reduced between 1807 and 1849. When Johann arrived in America, the fastest steamboat was able to reach Albany in seven and a half hours. I imagine most of the immigrants traveled on steamboats that were not at the cutting edge of performance. The goal for the majority of steamboat operators was to reach Albany in less than 10 hours. The Hudson River Day Line steamboats in the 1860s claimed to operate under the “nine hour system”, taking 9 hours to complete the trip between Albany and New York City, with Poughkeepsie as the half-way point. [47]

Table Three: Speed Records in Steamboat Travel Time

| Year | Steamboat Name | Time (Hour: Minutes) |

|---|---|---|

| 1807 | Clemont | 32 |

| 1817 | Chancellor Livingston | 18 |

| 1826 | Constellation | 15 |

| 1836 | North America | 10 |

| 1849 | Alida | 7:45 |

| 1851 | New World | 7:43 |

| 1852 | Francis Skiddy | 7:30 |

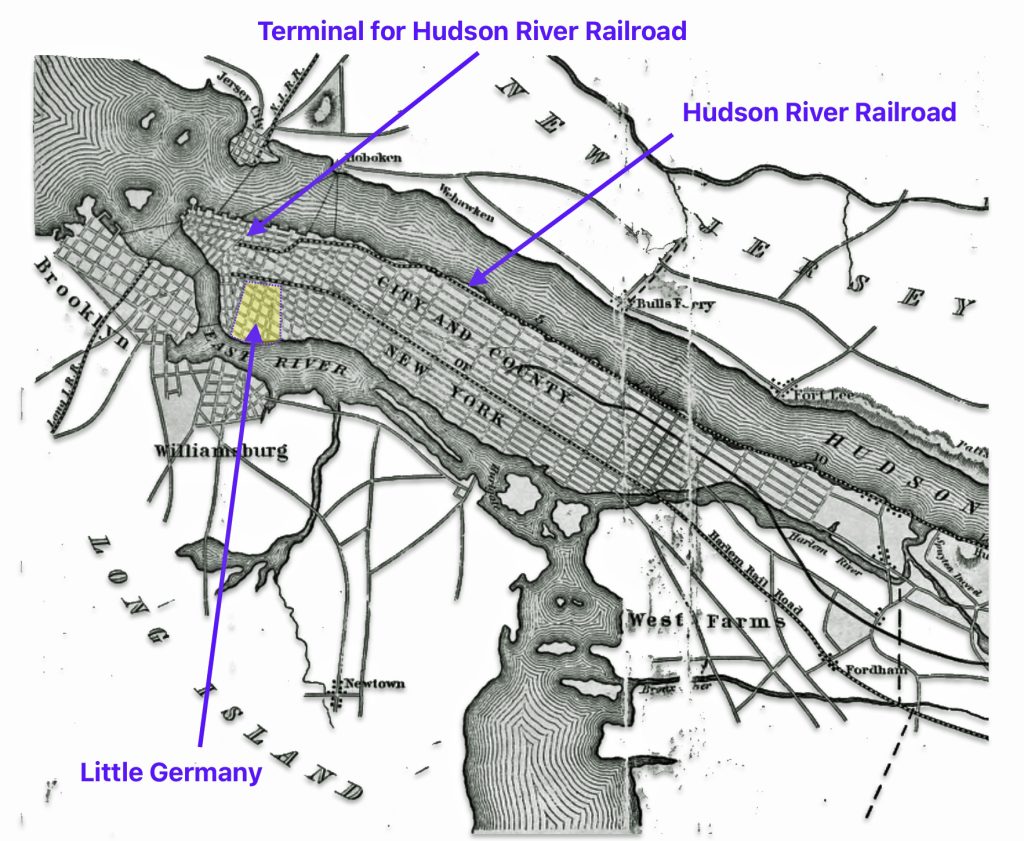

Through the 1840s, steamboat travel was the easiest and fastest method of transportation in the Hudson Valley. It dwindled, however, in the 1850s due to the faster travel service and competition of the Hudson River Railroad.

Railroads were rapidly expanding in the mid-19th century. By the 1840s, a railroad grid was taking shape in New York state, providing a transportation infrastructure that fueled the growth of commerce and transportation.

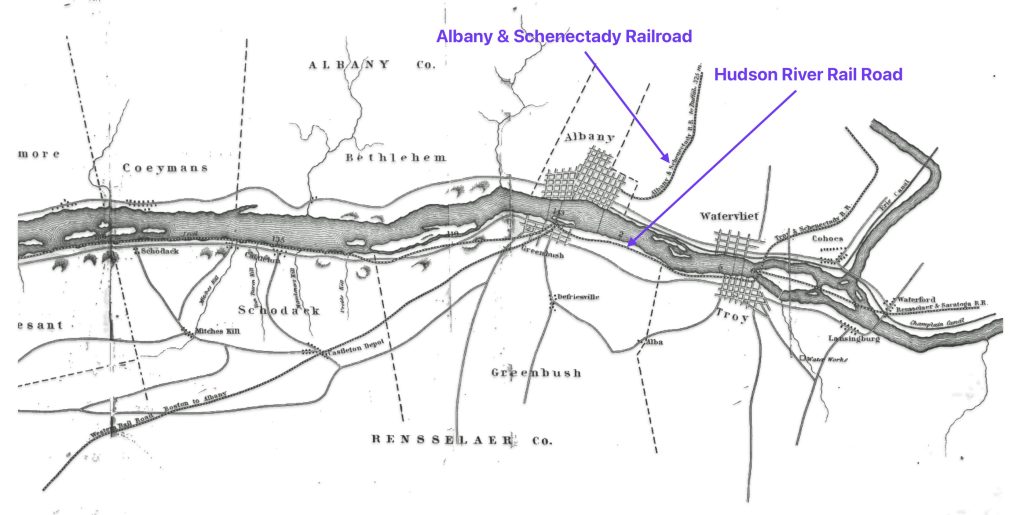

Between 1852 and 1856, Johann could have taken a train from New York City heading north towards upstate New York. The Hudson River Railroad was chartered in 1846 to build a rail line from New York City north to Rensselaer, NY (near Albany). The full line was completed in 1851, one year prior to Johann’s arrival. This provided the first rail link along the eastern shore of the Hudson River. It reduced reliance on steamboat travel along the Hudson River and spurred economic development in cities and towns along its route

The Start of the Hudson River Railroad was close to Little Germany, as depicted in map seven.

Map Seven: The Start of the Hudson River Railroad in New York City

During the winter months, averaging from ninety to one hundred days of each year, the Hudson River was closed by the ice. “(I)t proved a serious inconvenience, to say the least, for a channel, through which from one and a half to two millions of passengers were conveyed in the summer months, to be closed for the remainder of the year.” In the winter, when the river was closed the railroad was the major mode of transportation for both passengers and freight. [48]

Map Eight: The Terminus of the Hudson River Railroad in Albany & Troy New York

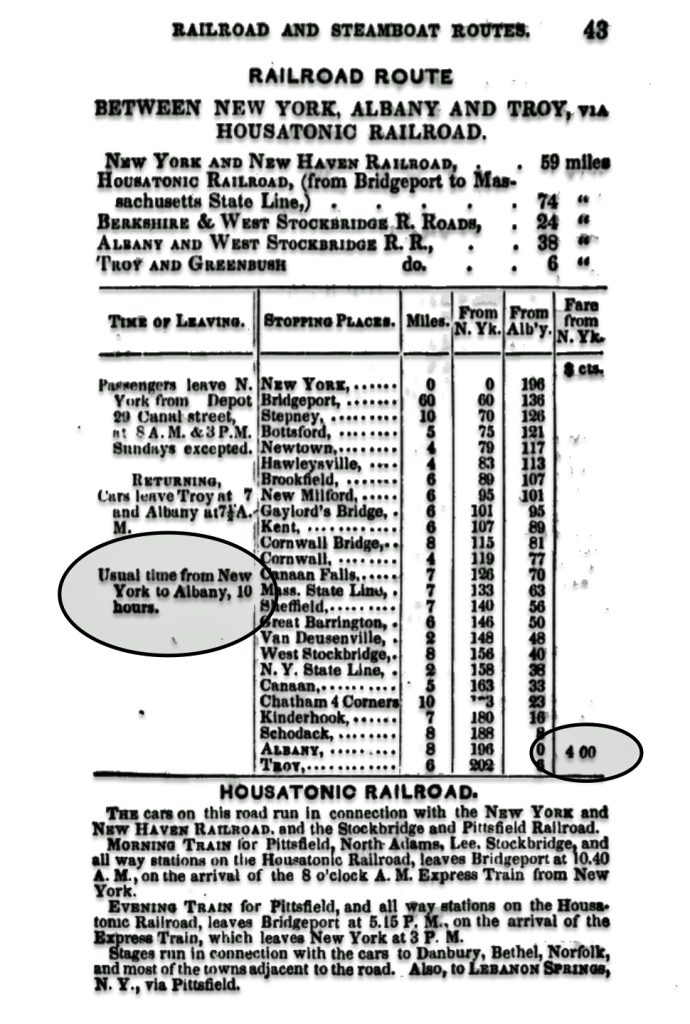

As reflected below, travel by rail took about ten hours between New York City and the capital area for the price of four dollars. Four dollars in 1850 is equivalent in purchasing power to about $161.06 in contemporary times. [49]

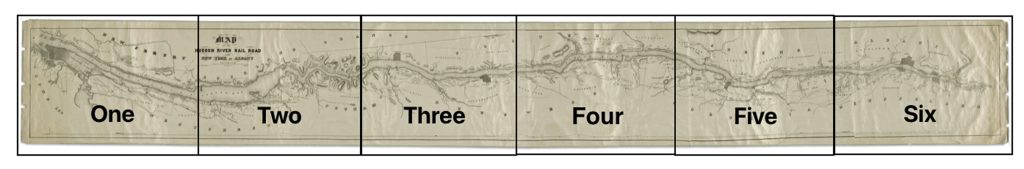

Map nine is an amazing multipage map that depicts the entire length of the Hudson River Railroad, from New York city to Albany New York.

Map Nine: The Hudson River Railroad from New York to Albany [50]

Since this map is so long, for a closer look at various sections of this map, click on the following lnks for a particular segment of the map:

Map One | Map Two | Map Three | Map Four | Map Five | Map Six

The broadside advertisement [51] of the railroad schedule for the Hudson River railroad below lists twelve trains scheduled for departure from New York City. It is noteworthy that one scheduled night train at 7:30 pm was listed as an “Emigrant and Freight Train for Albany and Troy”. The fares possibly were cheaper than the day rates; and the quality of the ride to Albany was probably ‘below standard’.

Hudson River Railroad Schedule Published on a Broadside Advertisement- July 10th 1852 [52]

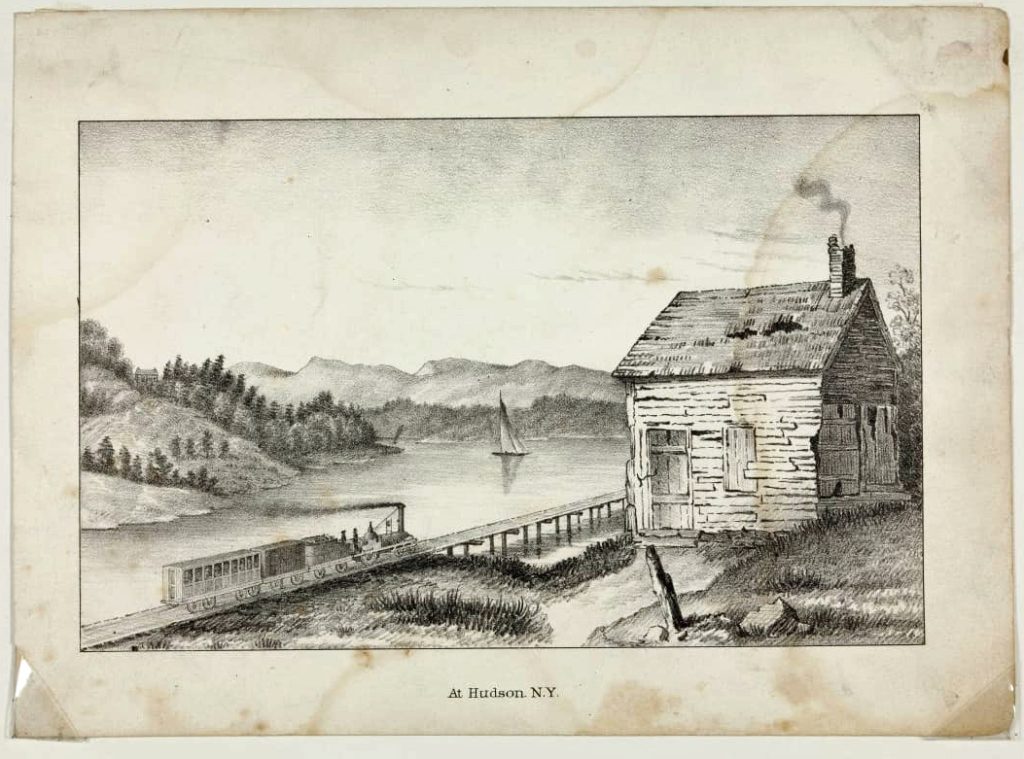

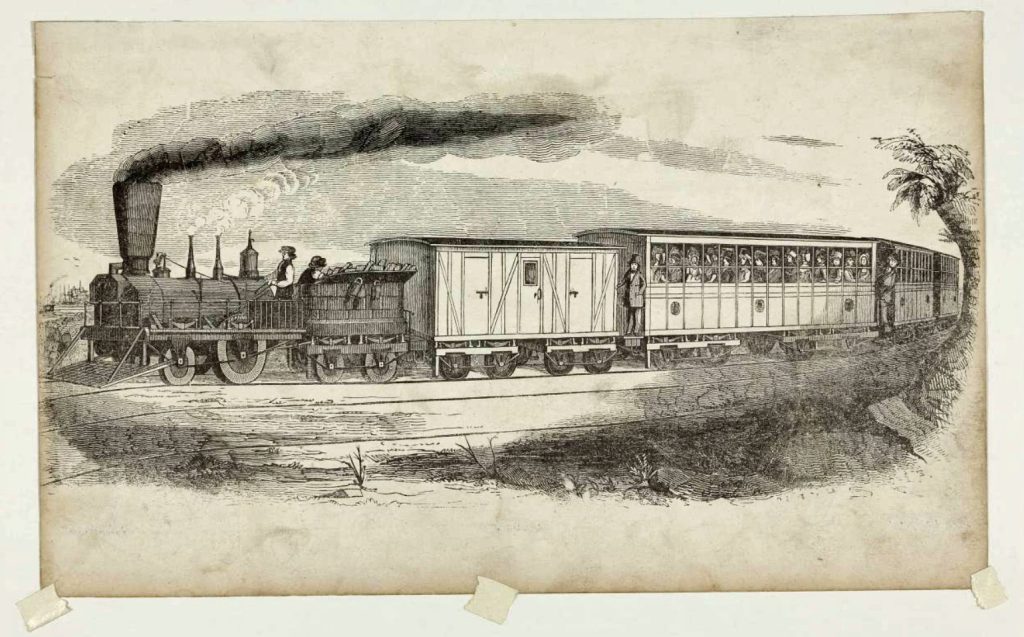

The following 1850s engravings depict a train with baggage and passenger cars near the town of Hudson, New York, traveling the tracks that parallel the Hudson River.

Train on the Hudson River Railroad, “At Hudson, N.Y.,” circa 1851 [53]

Wood Engraving of a Railroad Train, 1848-1852 [54]

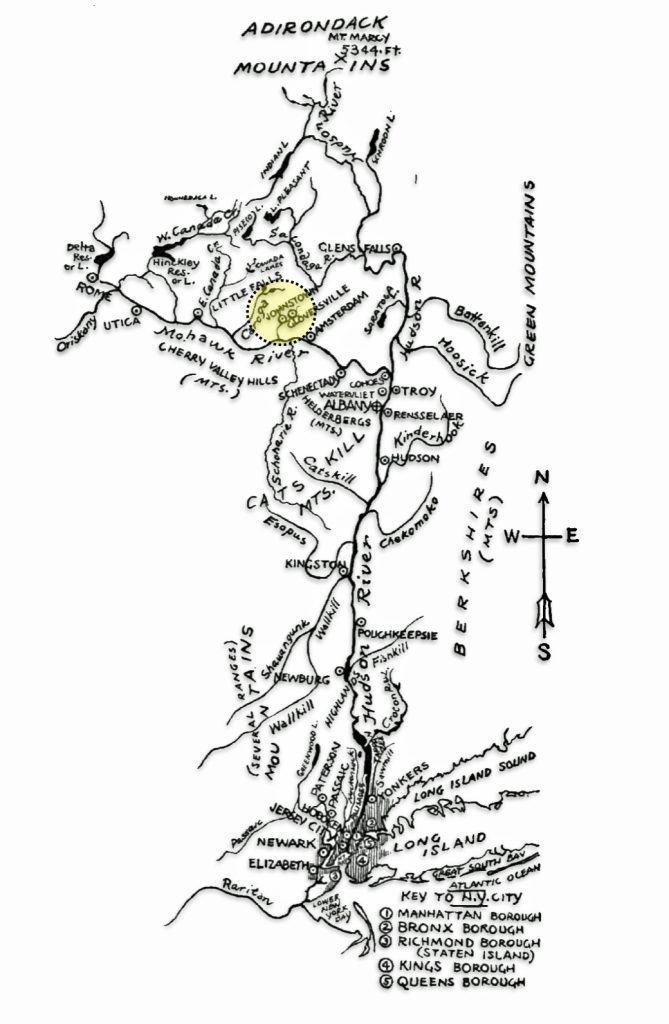

Arriving in Troy or Albany, New York by rail, water, road left about 45 miles from Johnstown and Gloversville. Johann could have continued on rail service to Fonda, New York and then could have taken a stagecoach to Johnstown The distance between Fonda and Johnstown is only 4.6 miles. Otherwise, Johann could have traveld by road from the train station in Albany to Gloversville.

The area around Albany, Troy and Schenectady had a long history of developing segments of railway. The Erie Canal, opened in 1825 between Albany and Buffalo and followed the Hudson and Mohawk rivers between Albany and Schenectady. The 40-mile Albany–Schenectady water route included several locks and was slow. Stagecoaches traveled the 17-mile direct route between the cities. In 1826 the Mohawk & Hudson Rail Road was incorporated to replace the canal stages between Albany and Schenectady. The Mohawk & Hudson Railway opened in 1831 [55]

“One by one, railroads were incorporated, built, and opened westward from the end of the Mohawk & Hudson: Utica & Schenectady, Syracuse & Utica, Auburn & Syracuse, Auburn & Rochester, Tonawanda (Rochester to Attica via Batavia), and Attica & Buffalo. By 1841 it was possible to travel between Albany and Buffalo by train in just 25 hours, lightning speed compared with the canal packets. Ten years later the trip took a little over 12 hours. In 1851 the state passed an act freeing the railroads from the need to pay tolls to the Erie Canal, with which they competed. That same year the Hudson River Railroad opened from New York to East Albany.” [56]

Conclusion

Once Johann Sperber landed in New York City, he had a number of options for his future in America. New York City provided a geographical base to plan his future movements. For the 1850s saw major changes and improvements in transportation, ushering in what historians call the “Transportation Revolution.”

The biggest advancement was the rapid growth of railroads. In 1850, there were about 9,000 miles of railroad tracks in the U.S. By 1860, this had more than tripled to over 30,000 miles. Railroads allowed people and goods to be transported much faster and more efficiently than ever before. A trip from New York to Chicago that used to take over a month could now be completed in just two days. [57]

However, train travel in the 1850s was still quite primitive and uncomfortable compared to today’s standards. Passenger cars were hot and stuffy in the summer, freezing cold in the winter, and filled with smoke and soot from the engine. Seating was on hard wooden benches. There were no dining cars, so passengers had to rely on meager offerings at train stations, which often lacked proper facilities. [58]

Before railroads became widespread, stagecoaches were a common way to travel longer distances. In the early 1800s, a network of toll roads called turnpikes were built, with stagecoach lines running between major cities. By the 1830s, the travel time from Boston to New York had been reduced from 4-6 days to just 1.5 days thanks to better roads and stagecoach relays. However, stagecoach travel was still bumpy, dusty, and unpleasant. [59]

In addition to overland travel, steamboats and canals became important modes of transportation, especially for freight. Starting with Robert Fulton’s steamboat in 1807, a network of steamboat lines soon developed on major rivers. Canals were also built to connect waterways, with the famous Erie Canal opening in 1825. But by the 1850s, railroads had outpaced both improved roads and canals to become the dominant form of transportation.

In the early 1800s, the primary routes from New York City to the Mohawk Valley were turnpikes (toll roads). Stagecoaches and wagons traveled these rudimentary roads, which made for slow and uncomfortable journeys that could take weeks.

However, the transportation revolution of the early-to-mid 19th century brought major improvements. The Erie Canal, completed in 1825, provided an efficient water route between the Hudson River at Albany and Buffalo on Lake Erie, running through the Mohawk Valley. This allowed goods and people to be transported much more quickly compared to overland routes.

The development of railroads in the 1830s and 1840s further transformed travel. In 1831, the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad began the first regular steam locomotive service between Albany and Schenectady. By the 1850s, several railroads were operating in the region as part of the rapidly expanding New York state railroad system, including the Utica and Schenectady Railroad and Syracuse and Utica Railroad. These rail connections made travel between New York City and the Mohawk Valley substantially faster and more comfortable compared to previous decades.

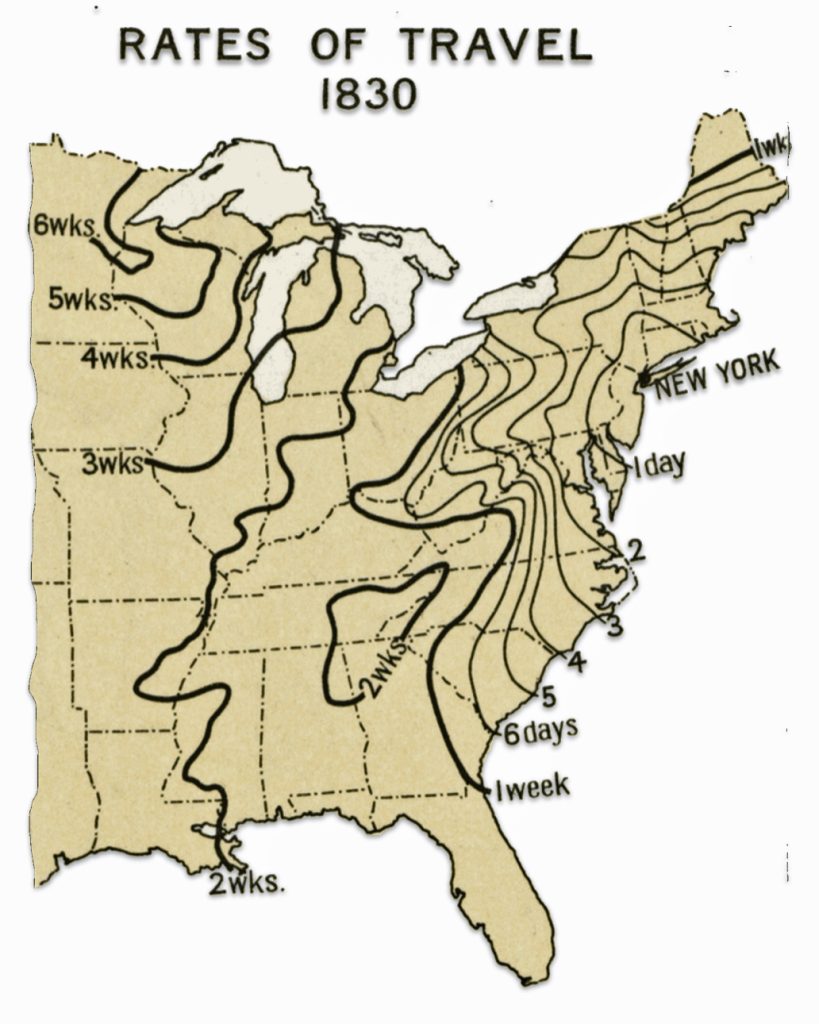

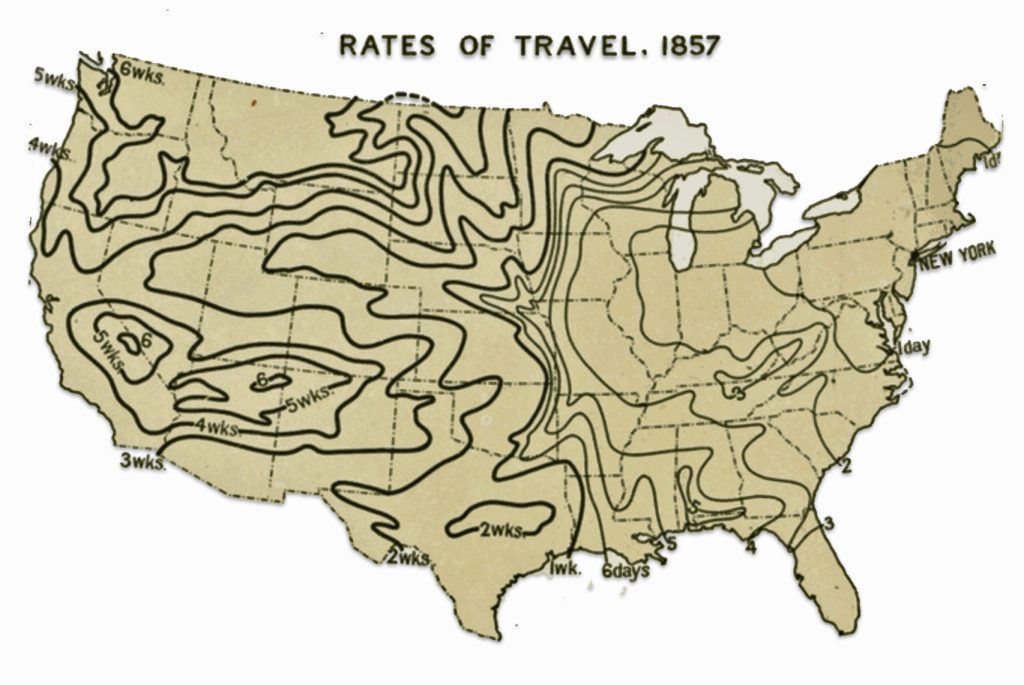

For example, maps showing travel times from New York City in 1830 indicate that reaching Albany took about 1 week.

By 1857, that same trip only took around 1 day by railroad. The 80-mile trip from Schenectady to Utica along the Mohawk Turnpike that used to take days now took just a few hours by rail.

While Johann was traveling up to the Mohawk Valley between 1852 and 1856, the many options he had available were rapidly changing.

Sources

Feature Photograph: This is a portion of an 1847 map that also appears in Williams, Wellington, Map 19, Appleton’s northern and eastern traveller’s guide: with new and authentic maps, illustrating those divisions of the country. Forming, likewise, a complete guide to the middle states, Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. Illustrated with numerous maps and plans of cities, engraved on steel and several wood engravings, New York: D. Appleton & Co. 1855, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b263188&seq=251

[1] Braunstein, Jean, L’émigration allemande par le port du Havre au XIXe siècle, Table: Emigrants Allemands Embarques Au Havre (1830 – 1870), Annales de Normandie, 1984, Page 102, https://www.persee.fr/doc/annor_0003-4134_1984_num_34_1_6382

[2] Gregory Saillard, Discovery of an unknown daguerreotype from old Le Havre: “The quai de la Citadelle circa 1845-1848” , 11 Jan 2023, The Classic, https://theclassicphotomag.com/discovery-daguerreotype-le-havre/

[3] Daguerreotype Photo Source: Anonymous, Havre, Quai de la Citadelle ca. 1845-1848, full plate daguerreotype, 20 x 24,8 cm, temporary modern mount, private collection.; referenced in Gregory Sallard’s blog story.

[4] Gregory Saillard, Discovery of an unknown daguerreotype from old Le Havre: “The quai de la Citadelle circa 1845-1848” , 11 Jan 2023, The Classic, https://theclassicphotomag.com/discovery-daguerreotype-le-havre/

[5] Carte D’Etat-Major 1820-1866, https://geocatalogue.apur.org/catalogue/srv/api/records/833fc566-cdbf-418e-8485-6fcd00af118b

The Service Géographique’s Carte de France refers to a detailed topographic map series produced by the French military’s geographical service, known as the Service Géographique de l’Armée. This map series, often referred to as the “Carte d’état-major,” was initiated in the early 19th century and played a crucial role in military and administrative planning in France.The Carte de France was notable for its scale and detail, typically at 1:80,000, which allowed for precise military and civil use.

The production of these maps was a significant undertaking, involving extensive surveys and cartographic expertise. The maps were highly regarded for their accuracy and detail, including topographical features like elevation contours, waterways, and urban layouts, which were essential for both military strategy and civil administration.

Carte d’état-major, Wkiipédia, La dernière modification de cette page a été faite le 20 avril 2024, https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carte_d%27état-major

[6] Beckert, Sven, Empire of Cotton: A Global History, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014, Pages 95, 148, 202, 205, 211 – 212, 216

See also: Dunham, Arthur L. “The Development of the Cotton Industry in France and the Anglo-French Treaty of Commerce of 1860.” The Economic History Review, vol. 1, no. 2, 1928, pp. 281–307. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2590336

“En 1852, 63 % des 72 325 emigrants embarques au Havre sont des Allemands. Ce chiffre s’eleve meme a 78,5 %, soit 54 000 emigrants allemands, en 1853. L’ emigration allemande par le port du Havre a atteint alors un sommet qui ne sera plus depasse.”

Braunstein, Jean, L’émigration allemande par le port du Havre au XIXe siècle, Table: Emigrants Allemands Embarques Au Havre (1830 – 1870), Annales de Normandie, 1984, Page 97 (quote) and page 101, https://www.persee.fr/doc/annor_0003-4134_1984_num_34_1_6382

[7] Havre-Union Line, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 14 January 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Havre-Union_Line

Albion, Robert G. (1965). Square-Riggers on Schedule: The New York Sailing Packets to England, France, and the Cotton Port (reprint ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965, Pages 110, 126 – 27, 286 – 287

Fairburn, William A. (1945). Merchant Sail, 6 vols. Center Lovell, Me: Fairburn Marine Educational Foundation, 1945, Pages 1136 -1137, 1235, 1245, 1269

Holley, O. L., ed. The New-York State Register, for 1845. New York: J. Disturnell, 1845, p. 257.

[8] A ‘standard’ advertisement of the Havre Union Shipping Line schedule between New York and Le Havre provided standardize dates for departure and arrival for each ship. It was routinely posted in the New York Evening Post as reflected below:

- Evening Post 12 February 1851, Page 4

- Evening Post 21 February 1851, Page 4

- Evening Post 16 May 1851, Page 4

- Evening Post 29 July 1851, Page 4

- Evening Post, 7 October 1851, Page 4

- Evening Post 23 October 1851, Page 4

- Evening Post 18 November 1851, Page 4

- Evening Post 10 December 1851, Page 4

- Evening Post 29 January 1852, Page 4

- Evening Post 3 March 1852, Page 4

- Evening Post 8 April 1852, Page 4

- Evening Post 24 July 1852, Page 4

- Evening Post 1 July 1852, Page 4

- Evening Post 27 July 1852, Page 4

- Evening Post 10 August 1852, Page 4

[9] Evening Post 3 March 1852, Page 4

[10] This record is found on microfiche Passenger lists of vessels arriving at New York, 1820-1897 United States. Bureau of Customs; United States. National Archives and Records Service [microform], slide 552 of 830, reel 114 – June 1-19, 1852 https://archive.org/details/passengerlistsoo0114unix/page/n551/mode/2up . The entire ship manifest list came be accessed as a PDF file.

[11] In its thirteen years in service, the shortest westward trip for the Germania was 26 days, the longest was 52 days and the average number of days the Germania took to reach New York City was 38. See Fairburn, William A. (1945). Merchant Sail, Volume II Center Lovell, ME: Fairburn Marine Educational Foundation. Pages 1198 & 1298

[12] The photograph was a stereographic photograph of the ship Germania docked at the Quai Casimir Delavigne, port of Le Havre. The stereographic photograph was produced after 1850. Handwritten in pencil on back was “Packet Ship GERMANIA/ Chas H Townsend [sic.] Comdg”. The photograph was printed “420 Quai Casimir – Delavigne (Havre).” The GERMANIA was built 1850, Portsmouth, New Hampshire by Fernald & Pettigrew. It was part of the New York & Havre Union Line.

Ship GERMANIA at pier, Le Havre, France, Collections and Research, Mystic Seaport Museum http://mobius.mysticseaport.org/detail.php?module=objects&type=related&kv=197389

Stereographs became extremely popular in the 19th century, especially after the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. Cheap stereoscope viewers and mass-produced stereograph cards made the technology affordable and accessible to the general public. By the mid-1850s, stereographs had become a widespread form of home entertainment.

Johnson, David, Nineteenth-Century Virtual Reality Devices, Oct 19 2017, New Orleans Museum of Art, https://noma.org/stereoscopes-first-virtual-reality-devices/

Guthrie, Anabeth, Stereo Views: The Nineteenth Century Meets the Twenty-First Century, National Gallery of Art, https://www.nga.gov/press/exh/138/backgrounder1.html

Development of stereoscopic photography, Britanica, https://www.britannica.com/technology/photography/Early-attempts-at-colour

Falza, Labiba, Double Takes: A Brief History of Stereographs, Jun 30 2023, Library Matters, McGill University Library News, https://news.library.mcgill.ca/double-takes-a-brief-history-of-stereographs/

Christie, Ian, 19th Century Craze for Stereoscopic Photography, Gresham College, https://www.gresham.ac.uk/watch-now/19th-century-craze-stereoscopic-photography

[13] Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data:View Sources. “United States Germans to America Index, 1850-1897.” Database. FamilySearch. http://FamilySearch.org : 18 July 2022. Citing NARA NAID 566634. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

M237 Roll 114, 1 Jun 1852–19 Jun 1852, https://www.archive.org/details/passengerlistsoo0114unix

[14] Weiser, Benjamin, Heat-Struck, July 1852, New York TImes, July 26, 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/28/nyregion/heat-struck-july-1852.html

Weiser, Benjamin, Heat-Struck, July 1852, July 26, 2013, New York TImes, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2013/07/28/nyregion/heat-struck-july-1852.html

[15] This map is a portion of the 1850 map made by Mitchell, Samuel Augustus, City of New-York, Hand Colored Map, 1850 Mitchell Map of New York City, Published by S. Augustus Mitchell, Philadelphia 1850.

Mitchell Map of New York City 1850

“This hand colored map of New York City is a lithograph engraving, dating to 1850 by the American mapmaker S.A. Mitchell Sr. The map epicts the island of Manhattan from 37th street (Kips Bay) south to Battery Park and Brooklyn from Williamsburg to Columbia St. The whole is shown in magnificent detail with many important buildings, ranging from the Brooklyn Naval Yard to important hotels and churches, depicted and labeled. One of the most visually appealing maps of New York City to emerge from the workshops of a mid-19th century American cartographer.”

Mitchell, Samuel Augustus, City of New-York, Hand Colored Map, 1850 Mitchell Map of New York City, Published by S. Augustus Mitchell, Philadelphia 1850; Online image: Geographicus NewYork City, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:1850_Mitchell_Map_of_New_York_City_-Geographicus-_NewYorkCity-mitchell-1850.jpg

Information on the location of the Havre Union Pier is based on: Map of the Port of New York on the south tip of Manhattan Island in 1851. Source: From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Map of the Port of New York on the south tip of Manhattan Island in 1851. Heavy broken line marks the waterfront below City Hall park in 1784. Area filled in prior to 1820. The original source is unknown. The old illustration was found in Carl C. Cutler, Queens of the Western Ocean, Annapolis: U.S. Naval Institute, 1961 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Port_of_New_York_1851.jpg

Information regarding the boundaries of Little Germany are based on information in Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City 1845-80, (Urbana:University of Illinois Press, 1990), Page 24

[19] Ecological Fallacy, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 15 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecological_fallacy

Hsieh, John J.. “ecological fallacy”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 4 Sep. 2017, https://www.britannica.com/science/ecological-fallacy

[20] Hoerder, Dirk. “The Traffic of Emigration via Bremen/Bremerhaven: Merchants’ Interests, Protective Legislation, and Migrants’ Experiences.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 13, no. 1, 1993, pp. 76. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27501115

[21] Thomas W. Page, “The Transportation of Immigrants and Reception Arrangements in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 19, no. 9, 1911, pp. 744. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1820349 .

[22] Ibid, Page 744

[23] Rippley, La Vern J. “Official Action by Wisconsin to Recruit Immigrants, 1850-1890.” Yearbook of German-American Studies, vol. 18, 1983, pp. 185-196; Page 186

[24] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City 1845-80, (Urbana:University of Illinois Press, 1990), Page 24, https://archive.org/details/littlegermanyeth0000nade

Herman, David, Revisiting Kleindeutschland, the East Village’s Little Germany, Oct 6, 2022, Off the Grid: Village Preservation Blog, https://www.villagepreservation.org/2022/10/06/revisiting-kleindeutschland-the-east-villages-little-germany/

Moses, Richard, Kleindeutschland: Little Germany in the Lower East Side, Lower East Side Preservation Initiative (L.E.S.P.I.), https://lespi-nyc.org/kleindeutschland-little-germany-in-the-lower-east-side/

Herman, David, Revisiting Kleindeutschland, the East Village’s Little Germany, Oct 6, 2022, Off the Grid: Village Preservation Blog, https://www.villagepreservation.org/2022/10/06/revisiting-kleindeutschland-the-east-villages-little-germany/

Schulz, Dana, Kleindeutschland: The History of the East Village’s Little Germany, Oct 2, 2014, 6sqft New York City, https://www.6sqft.com/kleindeutschland-the-history-of-the-east-villages-little-germany/

Little Germany, Manhattan, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 22 November 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Germany,_Manhattan

Carter, Abi, Little Germany, NYC: The rise and fall of a New York German community , 22 Sep 2023, https://www.iamexpat.de/lifestyle/lifestyle-news/little-germany-nyc-rise-and-fall-new-york-german-community

Yarce, Julio, What’s Left of Little Germany in NYC, Kleindeutschland, Untapped New York, https://untappedcities.com/2021/01/28/little-germany-nyc/

Lebkuchen, Leckerlee, A Brief History of Kleindeutschland in NYC, Nov 18, 2016, Leckerlee, https://leckerlee.com/blogs/blog/a-brief-history-of-kleindeutschland

Carr, Nick, Remnants of Kleindeutschland (Little Germany), May 11, 2009, Scouting in New York Blog, https://www.scoutingny.com/remnents-of-kleindeutschland-little-germany/

The Decline and Fall of Kleindeutschland, Blog Archive, Tenement Museum, https://www.tenement.org/blog/the-decline-and-fall-of-kleindeutschland/

[25] Richard Moses, Development of Kleindeutschland or Little Germany, Lower East Side Preservation Initiative, https://lespi-nyc.org/kleindeutschland-little-germany-in-the-lower-east-side/

[26] Nadel, Stanley, Kleindeutschland: New York City’s Germans: 1850 -1880, PhD Thesis, Columbia University, 1981, Page 1, https://www.proquest.com/openview/5078409a29b659dedb77c9e5b41ff5a7/1?cbl=18750&diss=y&pq-origsite=gscholar

Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany : ethnicity, religion, and class in New York City, 1845-80, Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 1990, https://archive.org/details/littlegermanyeth0000nade

[27] Bachmann, John, and Kimmel & Forster. Bird’s eye view of New York and environs. [New York Kimmel & Forster, 1865] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/75693052/

[28] Nadel, Stanley, Kleindeutschland: New York City’s Germans: 1850 -1880, PhD Thesis, Columbia University, 1981, Page 1, https://www.proquest.com/openview/5078409a29b659dedb77c9e5b41ff5a7/1?cbl=18750&diss=y&pq-origsite=gscholar

[29] Moses, Richard, Kleindeutschland: Little Germany in the Lower East Side, Lower East Side Preservation Initiative (L.E.S.P.I.), https://lespi-nyc.org/kleindeutschland-little-germany-in-the-lower-east-side/

[30] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany : ethnicity, religion, and class in New York City, 1845-80, Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 1990, Page 38, https://archive.org/details/littlegermanyeth0000nade

[31] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany : ethnicity, religion, and class in New York City, 1845-80, Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 1990, Appendix B Page 163 https://archive.org/details/littlegermanyeth0000nade

[32] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany : ethnicity, religion, and class in New York City, 1845-80, Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 1990, Pages 29, 37 – 39, https://archive.org/details/littlegermanyeth0000nade

[33] Ziegler-McPherson, Christina. (2014). German Immigrants in New York City, 1840-1920. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305770017_German_Immigrants_in_New_York_City_1840-1920/citation/download

See also Ernst, Robert, Immigrant Life in New York City, Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1994, Page 193. While this table reflects numbers for 1855, it is representative of the ethnic and native born mix of population in each of the New York City wards.

[34] Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany : ethnicity, religion, and class in New York City, 1845-80, Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 1990, Page 32, https://archive.org/details/littlegermanyeth0000nade

[35] Floor Area Per Person (FAPP) is a measure of the amount of floor space available to each individual within a given area or building. It is commonly used in space planning for offices, residential buildings, event venues, and public spaces to ensure comfort, safety, and efficient use of space.

Floor area, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 16 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Floor_area

Bitton, David, What Is Floor Area Ratio (FAR) & How to Calculate It, may 28, 2024, Doorloop, https://www.doorloop.com/definitions/floor-area-ratio-far

[36] Nadel, Page 32

[37] Nadel, Page 34

[38] Nadel, Page 24

[39] Ellis, B. Eldred, Gloves and the Glove Trade, London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons Ltd, 1921 , Page 71 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/93/Gloves_and_the_glove_trade_%28IA_glovesglovetrade00elli%29.pdf

[40] Ellis, B. Eldred, Gloves and the Glove Trade, London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons Ltd, 1921 , Page 71 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/93/Gloves_and_the_glove_trade_%28IA_glovesglovetrade00elli%29.pdf

[41] Bradbury & Guild, Hudson River and the Hudson River Railroad : with a complete map, and wood cut views of the principal objects of interest upon the line, Boston: Bradbury & Guild, 1851, Page 8, https://archive.org/details/ldpd_11549740_000

[42] Oklahoma Historical society, Steamboat Heroine, Overland Travel vs. Steamboat Travel, https://www.okhistory.org/learn/steamboat6

[43] Barges were also used to transport passengers up and down the Hudson River.

“Another feature of river life in the early days of steam navigation was the barges that carried passengers up and down the Hudson. These generally hailed from some of the small towns on the upper river that could not supply traffic enough to support a steamboat service. … These barges were boats with a main and upper deck almost as long and commodious as a steamer.” – Page 95

“It is believed the propeller type of river boat was especially built to make it more feasible to tow these barges, as the side wheel boats made it very noisy, the revolving paddles splashing the water at the side of the barges all night long. … Traveling by barge was not always the height of enjoyment and comfort … . Progress was slow and the boats latterly carried a varied cargo of farm products, bales of hay and live stock. Calves and lambs bound for the city slaughter horses and horses for the New York street car lines… .” – Page 98

Buckman, David Lee, Old Steamboat Days On the Hudson River, New York: Grafton Press, 1907, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Old_Steamboat_Days_on_the_Hudson_River/qEet2wKZTScC?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PP9&printsec=frontcover

[44] Blauweiss, Stephen and Karen Berelowitz, The Hudson River was yesteryear’s Thruway, AUG 18, 2021, HV1, The Hudson River was yesteryear’s Thruway, https://hudsonvalleyone.com/2021/08/13/the-hudson-river-was-yesteryears-thruway/

[45] North River Steamboat, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 1 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_River_Steamboat

Blauweiss, Stephen and Karen Berelowitz, The Hudson River was yesteryear’s Thruway, AUG 18, 2021, HV1, https://hudsonvalleyone.com/2021/08/13/the-hudson-river-was-yesteryears-thruway/

[46] Buckman, David Lee, Old Steamboat Days On the Hudson River, New York: Grafton Press, 1907, Page 65 https://www.google.com/books/edition/Old_Steamboat_Days_on_the_Hudson_River/qEet2wKZTScC?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PP9&printsec=frontcover

[47] Map of the Hudson River Line Steamers, 1883, Jan 21, 2014, Croton History & Mysteries, https://crotonhistory.org/2014/01/21/map-of-the-hudson-river-line-steamers-1883/

[48] Bradbury & Guild, Hudson River and the Hudson River Railroad : with a complete map, and wood cut views of the principal objects of interest upon the line, Boston: Bradbury & Guild, 1851, Pages 10-11, https://archive.org/details/ldpd_11549740_000

[49] CPI Inflation Calculator, https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1850?amount=4#

[50] Moore, W. C. (draftsman), Robert Haering (Engraver), George Snyder (Lithographer), “Map of the Hudson River Rail Road from New York to Albany.” Map. N.Y.: Lith. of G. Snyder, (c) 1848. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:ht250c54n

This map is also found as the last page in Bradbury & Guild, Hudson River and the Hudson River Railroad : with a complete map, and wood cut views of the principal objects of interest upon the line, Boston: Bradbury & Guild, 1851 https://archive.org/details/ldpd_11549740_000

[51] Broadside printing was a popular form of printing in the 18th and 19th centuries that involved printing on a single large sheet of paper pr heavy cardboard, only on one side. Some key characteristics of broadside printing include:

- Broadsides were typically large sheets printed on one side only, designed to be read unfolded and posted publicly to disseminate information widely.

- They served as an early form of mass media before newspapers became common, used to spread news, announcements, advertisements, and political views to the public.

- Broadsides were a very common form of ephemeral, disposable printing from the 16th-19th centuries, intended to have an immediate impact and then be discarded.

- They were often quickly and crudely printed in large quantities and distributed for free or sold cheaply on the streets.

- Broadsides featured large, eye-catching lettering and sometimes included woodcut illustrations to attract attention from a distance.

- In the ninteenth century, new technologies like fat face type and chromolithography allowed for more expressive typography and color printing in broadsides.

- Broadsides were used to announce events, publish proclamations, advocate political and social causes, advertise products, and celebrate literary and musical works

Broadside (printing), Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 15 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broadside_(printing)

The Popularity of Broadsides, Printed Ephemera: Three centuries of Broadsides and Other Printed Ephemera, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/broadsides-and-other-printed-ephemera/articles-and-essays/introduction-to-printed-ephemera-collection/the-popularity-of-broadsides/

Brabner, Ian, Rare Americana, American Broadsides: History on a Sheet of Paper, https://www.rareamericana.com/articles/american-broadsides/

[52] Hudson River Railroad Schedule of Fares Between New York City, Albany and Troy, New York, 1852, 10 July 1852, Broadside (Notice), Mat board Paper (Fiber product), Height: 16.438 in x Width: 10.75 in, Seymor Dunbar Collection, Digital Collections, Henry Ford Museum, https://www.thehenryford.org/collections-and-research/digital-collections/artifact/131241/#slide=gs-204355

[53] Train on the Hudson River Railroad, “At Hudson, N.Y.,” circa 1851, Height: 7.688 in Width: 10.5 in, Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago Illinois, Digital Collections, Henry Ford Museum, https://www.thehenryford.org/collections-and-research/digital-collections/artifact/162285#slide=gs-224603

[54] Wood Engraving of a Railroad Train, 1848-1852, Height: 5.688 in Width: 9.375 in, Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago Illinois, Digital Collections, Henry Ford Museum, https://www.thehenryford.org/collections-and-research/digital-collections/artifact/61888#slide=gs-219882

[55] New York Central Railroad, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 27 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_Central_Railroad

Troy & Schenectady Railroad, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 12 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Troy_%26_Schenectady_Railroad

Adam Burns, Mohawk and Hudson Railroad, American Rails, June 7, 2023, https://www.american-rails.com/mohawk.html

List of New York railroads, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 3 August 2023, , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_New_York_railroads

Adam Burns, New York Central Railroad (NYC): “The Great Steel Fleet”, Sep 11, 2023, American Rails, https://www.american-rails.com/york.html

Adam Burns, Fonda, Johnstown & Gloversville Railroad, Apr 13 2023, American-Rails, https://www.american-rails.com/fjg.html

Fonda, Johnstown and Gloversville Railroad, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 28 December 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fonda,_Johnstown_and_Gloversville_Railroad

George Drury, December 28, 2020, Remembering the New York Central System — Part 1, Railroads & Locomotives, https://www.trains.com/ctr/railroads/fallen-flags/remembering-the-new-york-central-system-part-1/

Daniels, George H. (George Henry), 1893 map of the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad, The New York Central & Hudson River R.R. and connections, Buffalo, 1893 , Library of Congress, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3711p.rr004870

[56] George Drury, December 28, 2020, Remembering the New York Central System — Part 1, Railroads & Locomotives, https://www.trains.com/ctr/railroads/fallen-flags/remembering-the-new-york-central-system-part-1/

New York Central Railroad, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 27 September 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_Central_Railroad

[57] Burns, Adam, Railroads and the Industrial Revolution (1850s), Mar 9, 2024, American-Rails, https://www.american-rails.com/1850s.html

[58] Lacy, Connie, Not for sissies: Train travel in the 1850s, Dec 2, 2020, https://www.connielacy.com/post/not-for-sissies-train-travel-in-the-1850s

[59] Historical Background on Traveling in the Early 19th Century, Teach US History. Org, https://www.teachushistory.org/detocqueville-visit-united-states/articles/historical-background-traveling-early-19th-century