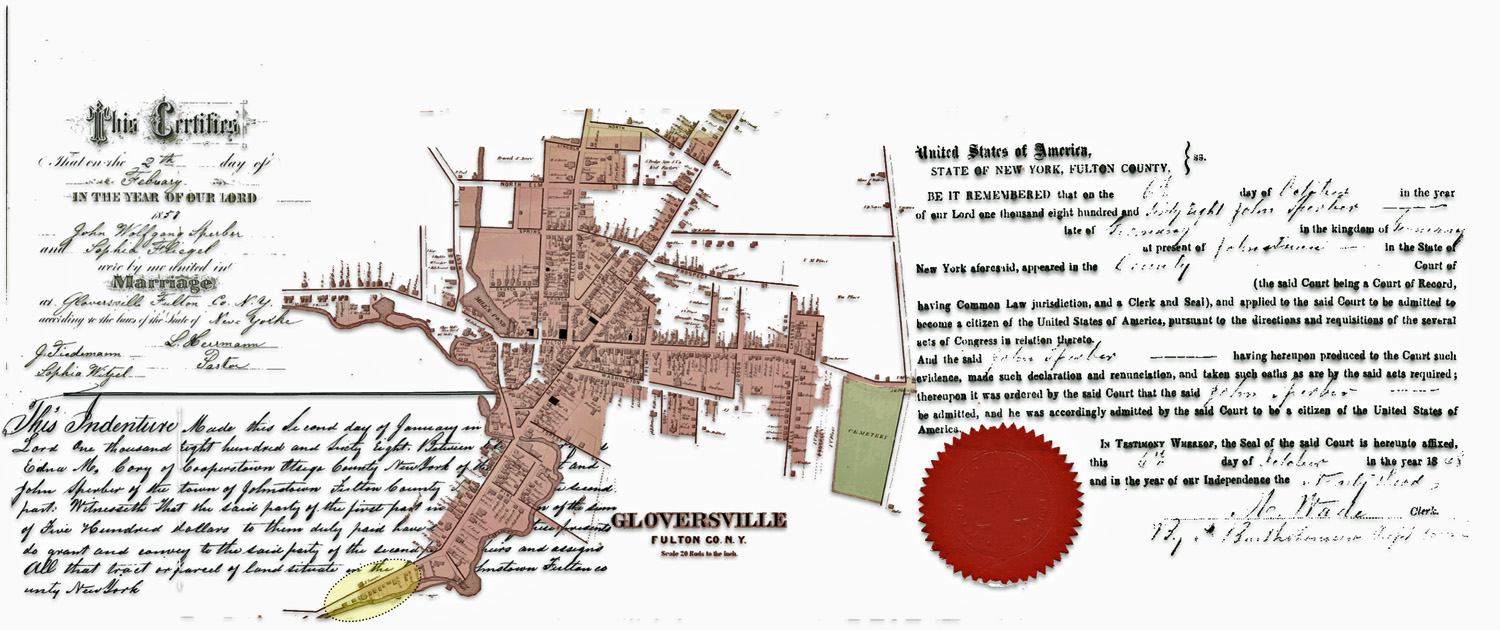

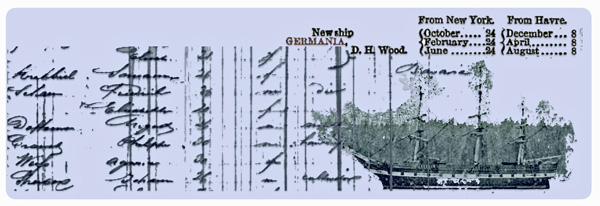

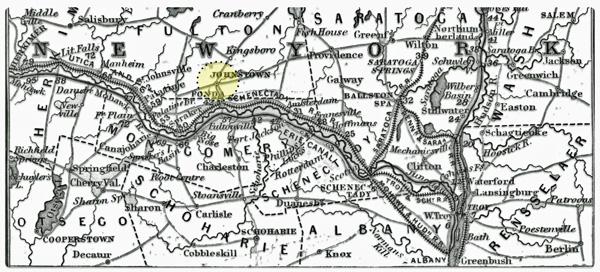

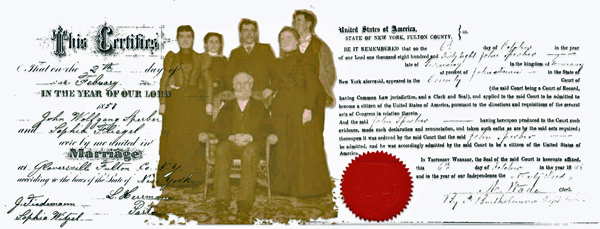

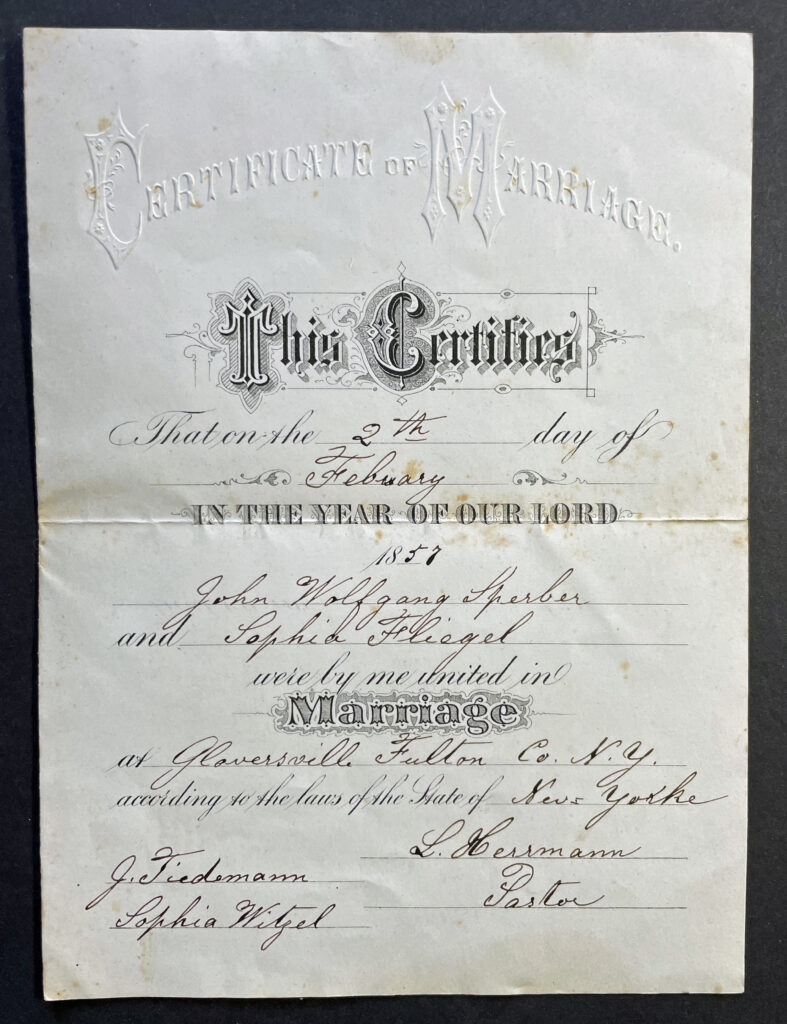

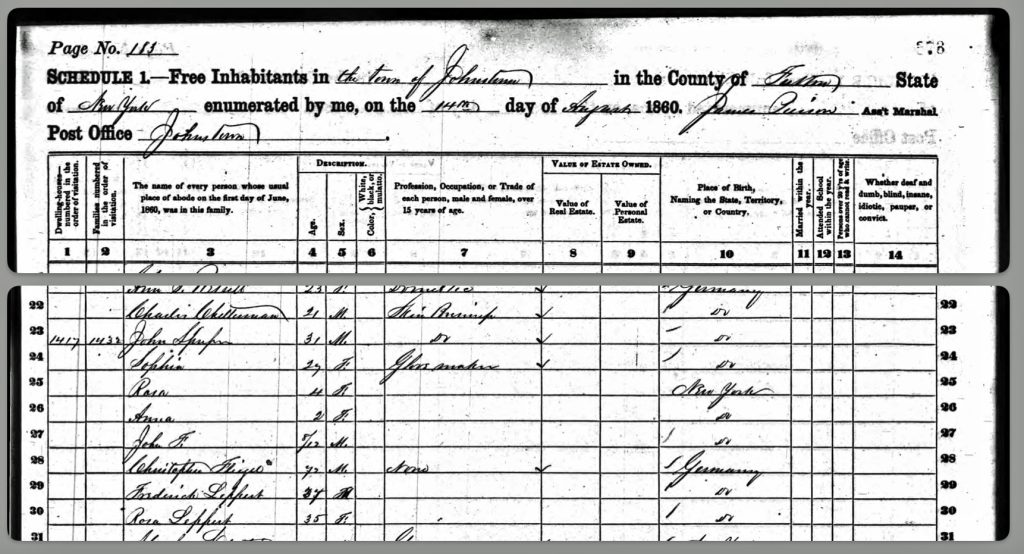

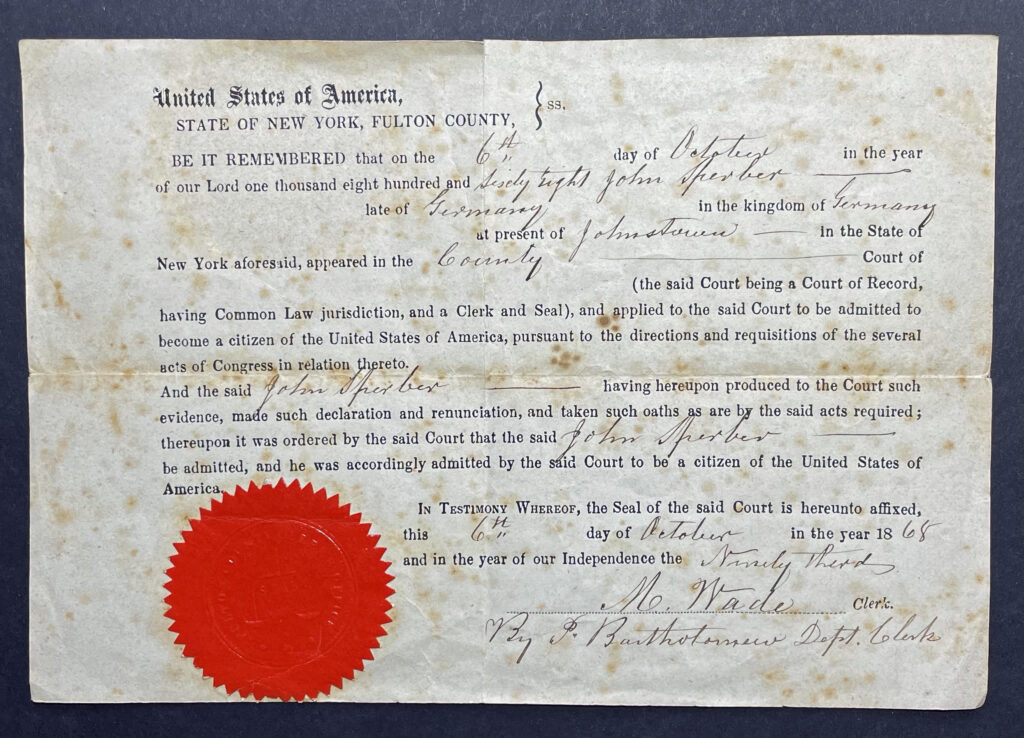

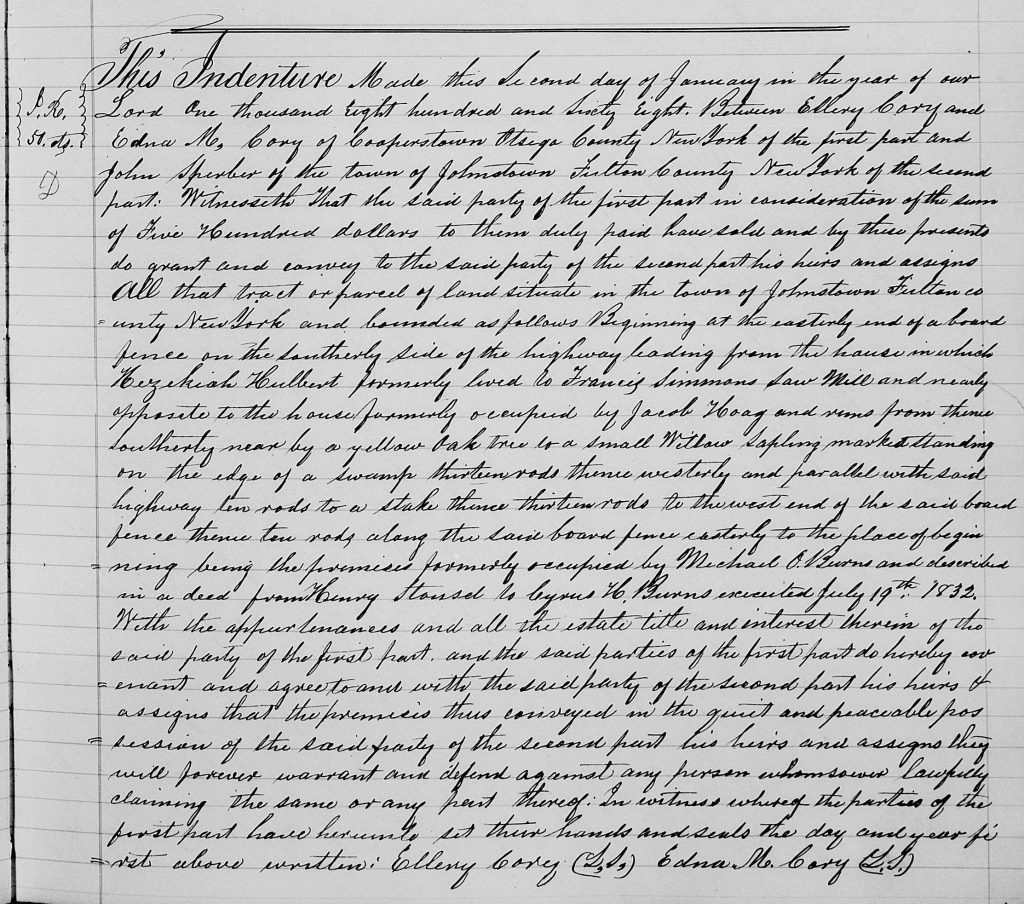

As discussed in the in part six of this story, John Sperber was married, started a family and worked in the glove making business in Gloversville in the late 1850’s. He also realized part of the American Dream in the 1860s after the Civil War ended. John became a citizen and bought a house.

The Sperber Family in the 1870s

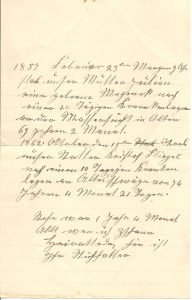

In the late 1860s John and Sophie Sperber had a foothold in their German past and their beginnings of a future in America. The growing local economy of Gloversville provided a fairly stable, prosperous base for a young couple from Germany to make a living and support a growing family. Their family ties and extended network of German immigrant peers in the glove making business provided additional social and economic support.

By 1860, there were 45 glove and mitten factories employing 1,040 workers in Gloversville. This did not include all of the home based glove shops that supported the glove making businesses in the Village of Gloversville. The town’s population had grown to 1,486. The Civil War increased demand for gloves during the 1860s, further boosting the glove making and tanning industries.

By 1870, Gloversville produced more than half of all leather gloves made in the United States. The town now had a population of 4,518, tripling in size from a decade earlier. [1]

The 1870s in the United States was a period of significant economic change and upheaval, often referred to as part of the “Gilded Age”. It was characterized by both remarkable economic growth and productivity, as well as major economic challenges and inequalities, culminating in the Panic of 1873 and the Long Depression which lasted until 1879, the worst recession in the United States until the Great Depression of the 1930s. The economic challenges and inequities, however, had less of an impact and effect on the Gloversville.

Tanneries were a major part of the local economy, processing leather from local hemlock forests. In 1870, Gloversville had 21 tanneries employing 350 workers. Finished leather was sent to the glove shops and also shipped out of town. Many of the tanneries were located upstream along the Cayadutta Creek where the Sperber’s house was located.[2]

The concentration of tanneries and glove shops encouraged the growth of related industries like thread and needle dealers, sewing machine companies, box and paper manufacturers, glue manufacturers and transportation services. [3]

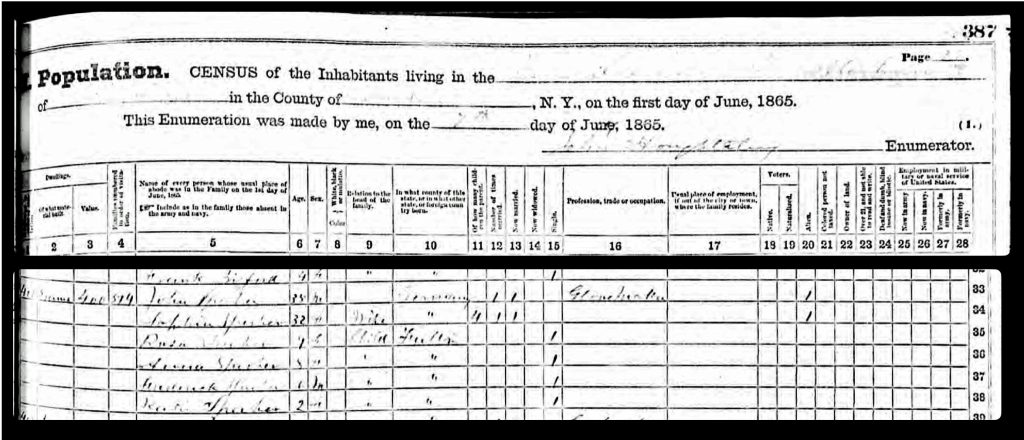

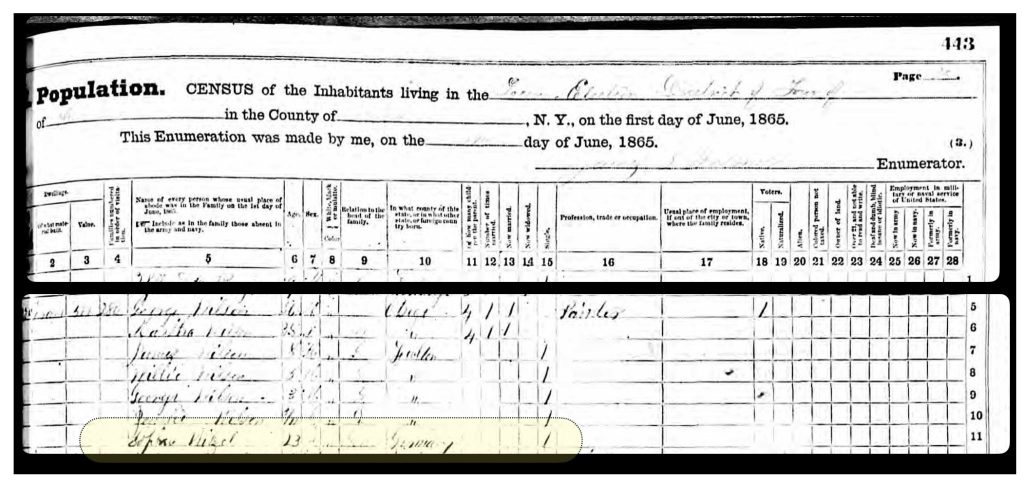

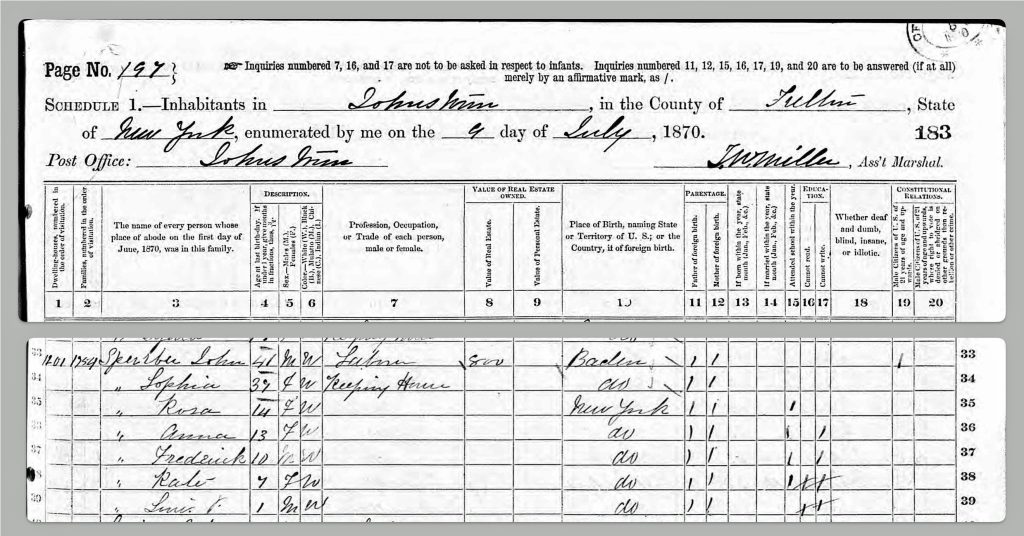

In 1870, the Sperber’s recently purchased house was valued at $800.00. The family now included John and Sophie and their five children. Rose and Anna were teenagers, 14 and 13 respectively. Frederick is 10 and Kate, who was born on January 1st, 1864, is 7. Their fifth child, Louis Sperber, was one year old. The census enumerator indicated that Rosa, Anna and Frederick were in school. He indicated that Anna and Frederick could not write and Kate could not read nor write. John’s occupation is listed as ‘laborer’.

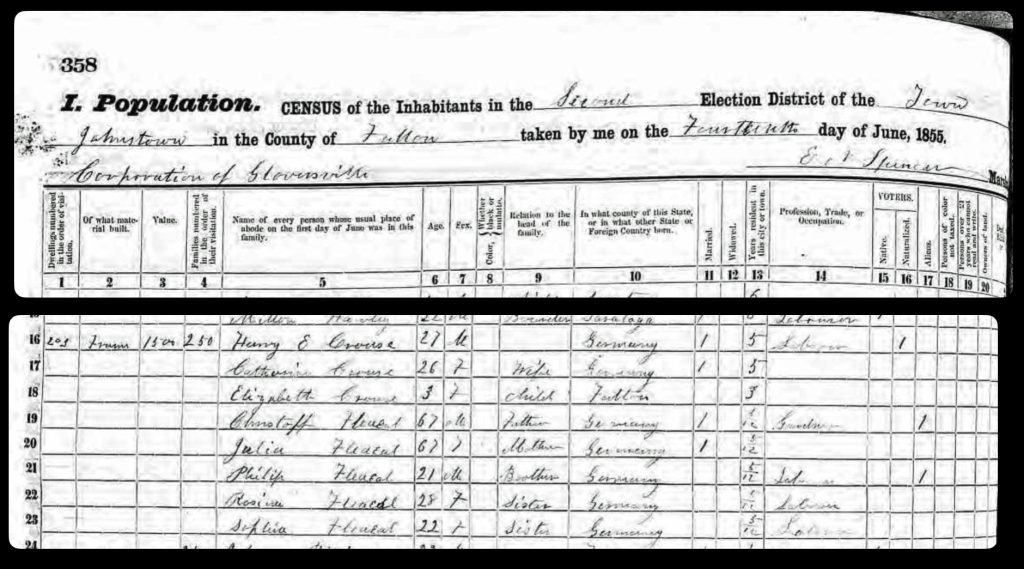

Census One: Enlarged Section of U.S. 1870 Census

Source: 1870 U.S. Federal census, New York State, Fulton County, Johnstown, Page 197, Lines 33 -39

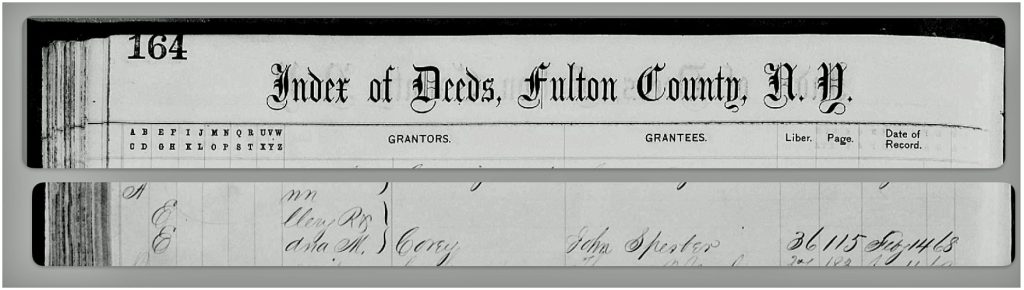

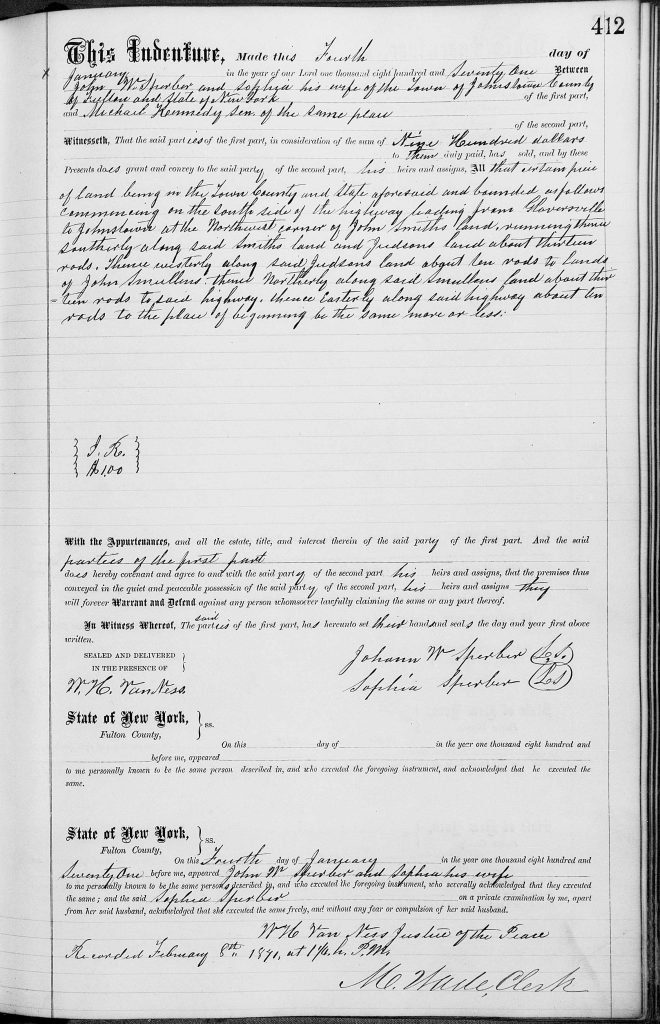

In 1871, it appears that John and Sophia sold a parcel of land for $900.00 to Michael Kennedy Senior. It is presumed that the parcel of land was part of the original parcel of land that was purchased in 1868. If this true, then the Sperbers were lucky and shrewd in making money off of their land acquisitions. They originally purchased property on South Main Street, the ‘highway’ that connected Gloversville with Johnstown, for five hundred dollars. In four years they sold a parcel of land for nine hundred dollars. Their home was located in the vortex of rail transport lines and a major roadway between Gloversville and Johnstown.

Transcribed Portion of the January 4, 1871 Deed

| This indenture, made this fourth day of January in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and Seventy one between John W. Sperber and Sophia his wife of the Town of Johnstown County of Fulton and State of New York of the first part, and Michael Kennedy Sen(ior) of the same place . This indenture, made this fourth day of January in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and Seventy one between John W. Sperber and Sophia his wife of the Town of Johnstown County of Fulton and State of New York of the first part, and Michael Kennedy Sen(ior) of the same place . Witnesseth, That the said parties of the first part, in consideration of the sum of Nine Hundred dollars to them duly paid has sold, and by these Presents does grant and convey to the said party of the second part, his heirs and assigns All that certain piece of land being in the Town County and State aforesaid and bounded as follows commencing on the south side of the highway leading from Gloversville to Johnstown at the Northwest corner of John Smiths land, running thence southerly along said Smiths land and Judsons land about thirteen rods. Thence westerly along said Judsons land about tend rods to lands of John Smullins thence Northerly along said Smullens land about thirteen rods to said highway, thence easterly among said highway about ten rods to the place of beginning of the same more or less. |

Land Deed Between John & Sophia Sperber and Michael Kennedy January 4, 1871

Source: New York Land Records, 1630 – 1975, Fulton County, Deeds 1869 – 1871 , vol 39, page 412

The establishment of rail connections between towns and cities as well as in-town trolleys during the 1860s was instrumental for supporting Gloversville’s rapid industrial growth. These transportation improvements facilitated the movement of raw materials, finished goods, and people, allowing Gloversville’s glove and leather trades to expand into national markets.

“In the mid-19th century virtually every town and city of any size was hoping to be served by the rapidly growing, and sprawling, railroad industry. One of these communities was Johnstown, which thought for sure it was soon to gain rail access when Fonda to the south along the Mohawk River was reached by the Mohawk & Hudson Railroad on August 1, 1836. Unfortunately, residents had to wait for more than 30 years until trains finally reached their community. On January 17, 1867 local businessmen organized the Fonda, Johnstown and Gloversville Railroad with intentions of establishing service to all three towns.” [4]

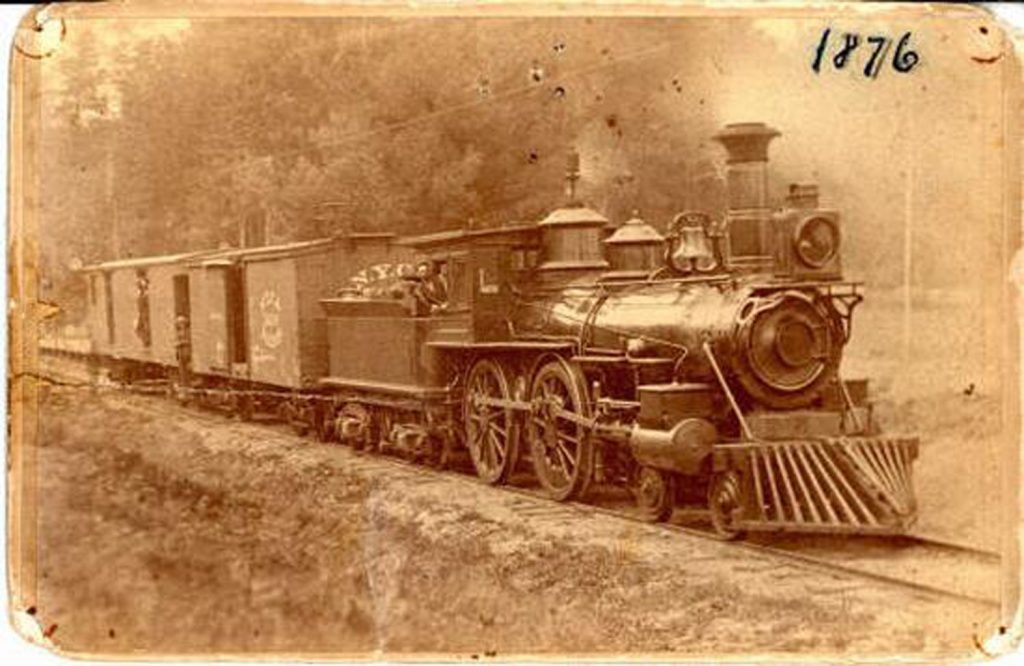

The Fonda, Johnstown and Gloversville Railroad (FJ&G) was incorporated in 1867 and the first train ran from Fonda to Gloversville in 1870. It connected Gloversville to the Railroad line in Fonda, allowing manufacturers to more easily transport their goods to outside markets. The FJ&G also provided passenger service, making it easier for workers, salesmen, and buyers to travel to and from Gloversville. Beginning in October of 1872 the Gloversville & Northville Railroad began construction of a 17-mile extension to link its towns. It was completed by the summer of 1876. [5]

The following is an 1870 photograph of a Fonda, Johnstown & Gloversville railroad locomotive that was purchased from the Manchester Locomotive Works, builder’s no. 249, during late summer of 1870. The cost of this engine was $10,500. It was renamed David A. Wells after its 1873 rebuilding in honor of the company’s vice-president. [6]

Locomotive “Pioneer” on the Fonda, Johnstown and Gloversville Railroad

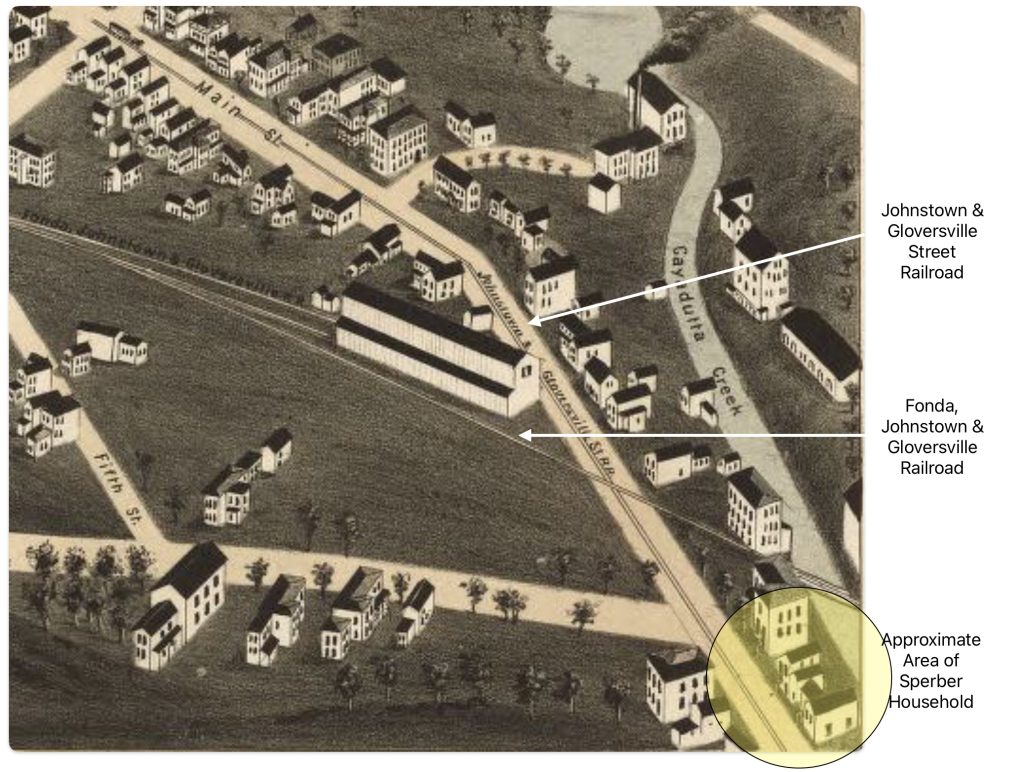

The Fonda, Johnstown & Gloversville rail line or Railroad crossed South Main Street to the Northeast of where the Sperber’s house was located. The rail line crossed Main Street and passed diagonally behind their property.

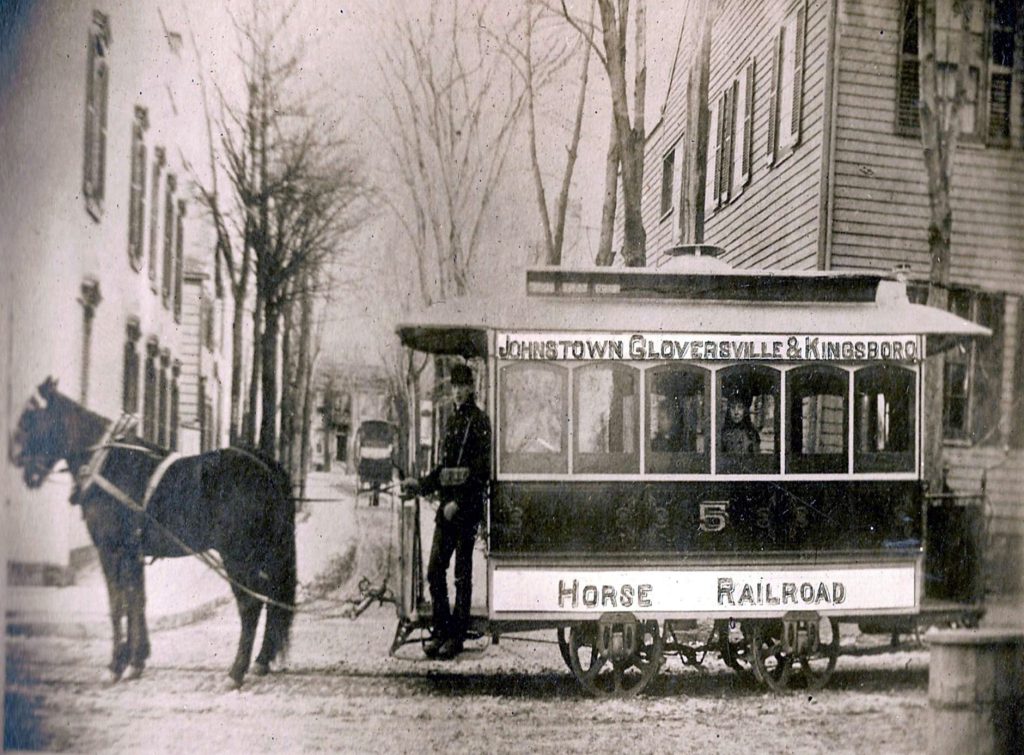

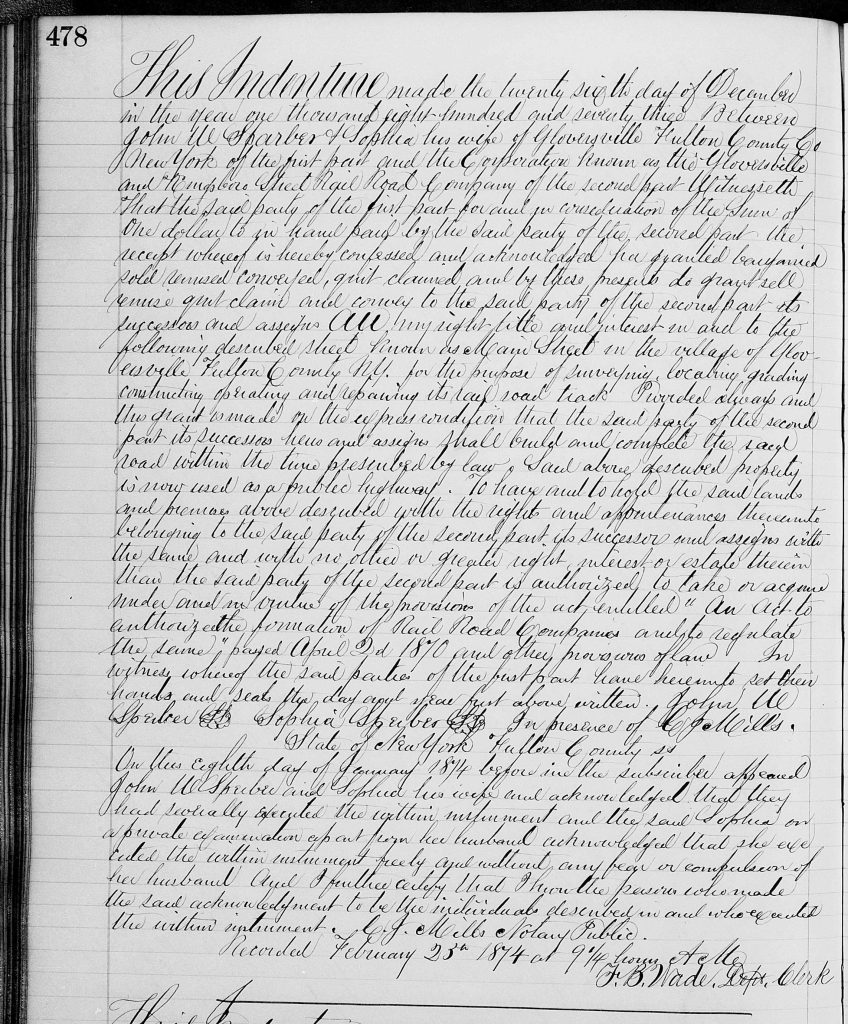

In 1874 an indenture to the Sperber property was enacted by the Gloversville and Kingsboro Street Rail Road Company. The Sperber’s were given one dollar to quit claim the rights to access their property for the purpose of surveying, locating, grading, constructing operating and repairing its rail road track“. [7] The horse rail track went up South Main Street in front of their house. On August 28, 1874, the first regular trip of a horse car passed from Johnstown to Gloversville.

The Johnstown, Gloversville and Kingsboro Horse Rail Road Company was different and separate from the Fonda, Johnstown & Gloversville rail line. It was one of the first horse railroads in Fulton County.

Photograph of the Johnstown-Gloversville-Kingsboro Horse Railroad

Horsecars represented an intermediate technology between horse-drawn omnibuses and electric streetcars in the evolution of urban transit. [8] In the late 1800s, horse railroad companies, also known as horse-drawn streetcar or horsecar companies, provided urban transportation in many American cities before the widespread adoption of electric streetcars. Horse-drawn streetcars on rails emerged in the 1830s and became widespread by the 1860s-1880s. By 1880, there were about 18,000 horsecars operating in the United States. [9]

The Johnstown, Gloversville and Kingsboro Horse Rail Road Company was incorporated on November 12, 1873 under general laws of New York for the purpose of constructing and operating a horse-car railroad extending from Johnstown to Kingsboro (now a part of Gloversville), NY. The company operated 4.09 miles of track. It was originally constructed as a horse-car railroad around 1876. It was later changed to an electric railroad around 1893. The railroad cost $45,000 to build in 1875. Horse-drawn cars were operated over this road and replaced by sleighs in winter. There were six passenger cars and sixteen horses. [10]

Horses typically pulled the streetcars along rails embedded in city streets. A typical horsecar held around 30 passengers. The street cars in Gloversville were much smaller, as illustrated in the photo above.. Maintaining and stabling the horses was a major expense for the companies. Horses could only work a limited number of hours per day before needing rest. [11]

Joel Griffis and the Kingsboro Segment of the Johnstown, Gloversville and Kingsboro Horse Rail Road Company Rail Line

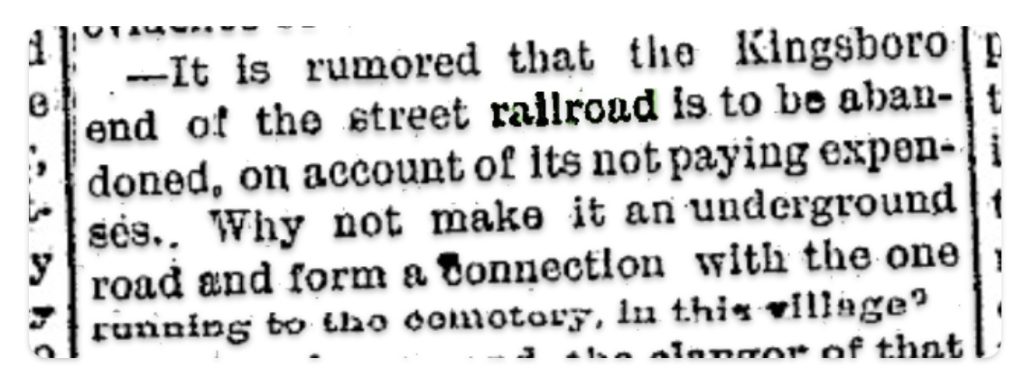

In 1875, the passengers between Gloversville and Kingsboro sections of the horse rail line were not sufficient to make the rail line profitable. While the glove making business was generally thriving, the Kingsboro section of the street rail line was struggling. Perhaps the problem was due to poor management or just a lack of customers between Gloversville and Kingsboro. The effects of nation-wide Long Depression, which lasted from 1873 to 1879, may have had an impact on the performance of this section of the street rail line.

The Amsterdam Recorder indicated on May 17, 1876, “fires and failures are becoming fashionable in Gloversville and Johnstown”

Joel Griffis, of Kingsboro, leased the Gloversville & Kingsboro rail line, at the age of 69, for an unspecified period in April 1876. By March of 1877 rumors were floating that the rail line was to be abandoned. [12]

The local newspaper jokingly suggested making the rail line an underground rail line to the cemetery.

The streetcar tracks between Gloversville and Kingsboro were taken up in the first week of June 1880. It was the end of the Gloversville and Kingsboro Horse Railroad.

Unfortunately, for Joel Griffis, regardless of his work experience, the economic conditions surrounding the Gloversville – Kingsboro rail service were not conductive for success. [13]

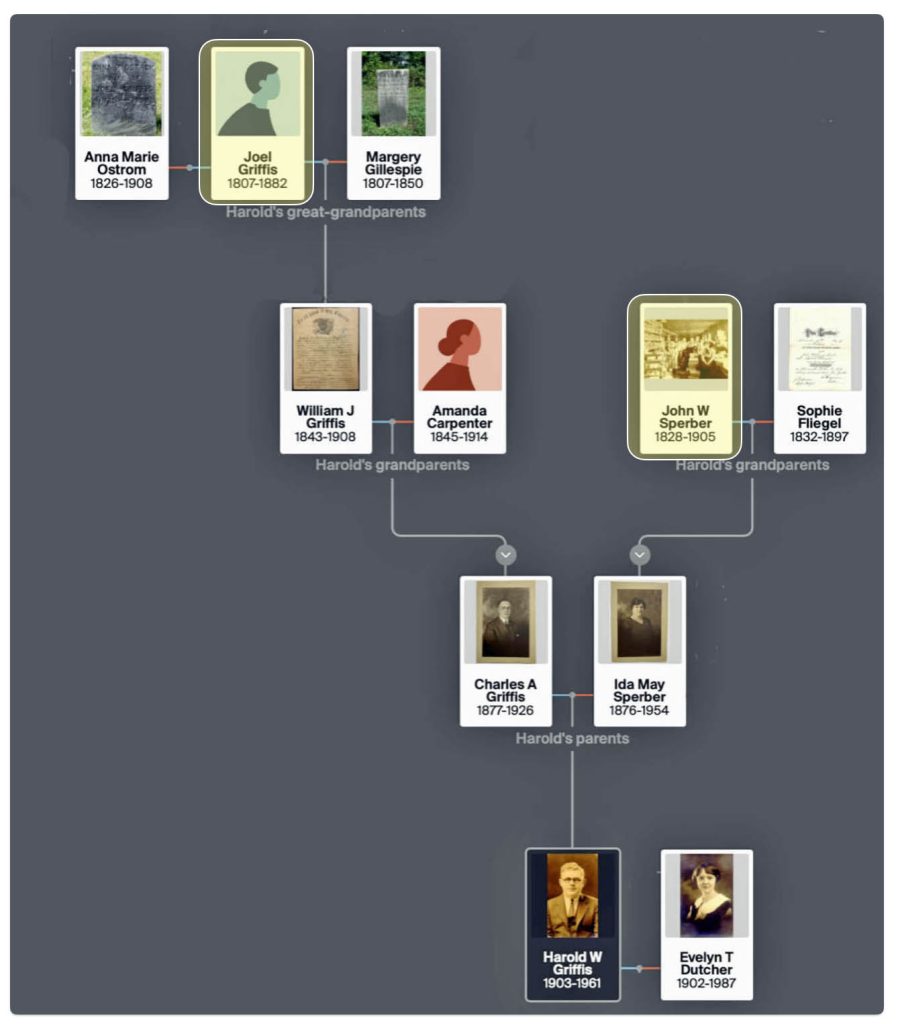

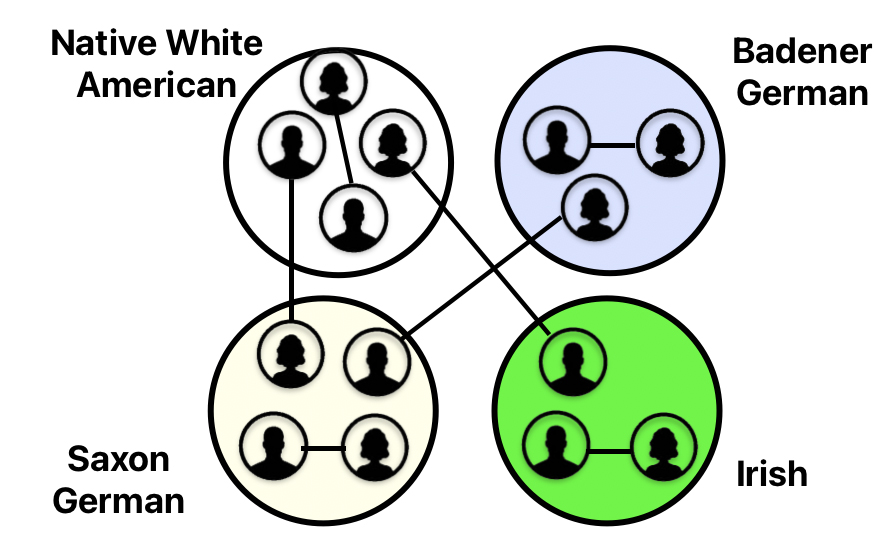

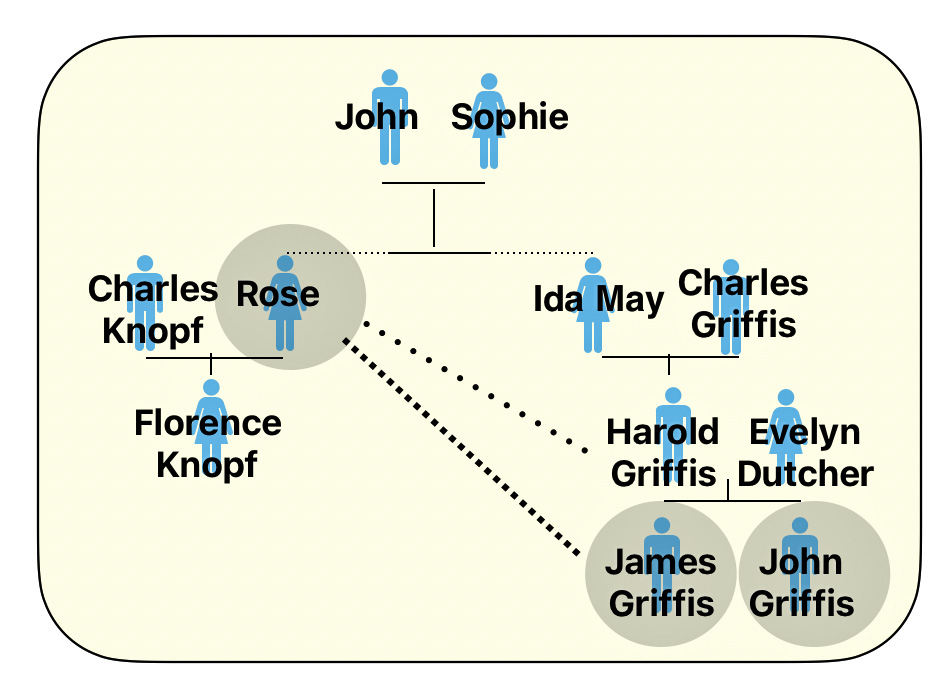

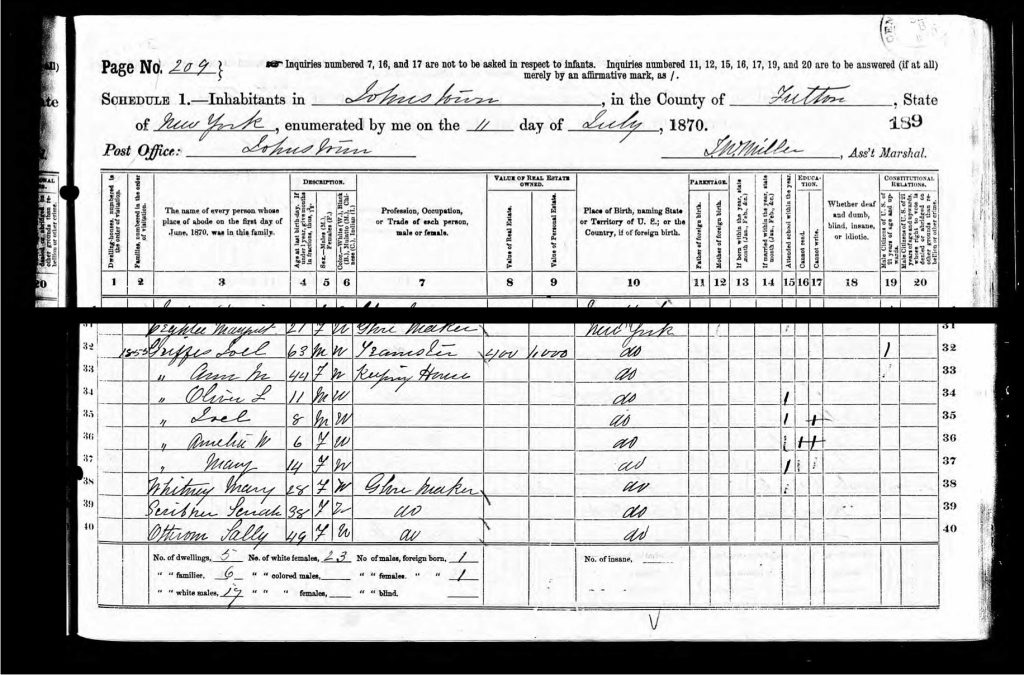

Joel Griffis: His Position within the Family Tree

While John Sperber was the maternal grandfather of Harold Griffis, Joel Griffis was the paternal great grandfather of Harold Griffis. Joel Griffis was born on 14 Oct 1807 in Albany, New York and died on 18 Oct 1882 in Gloversville City, Fulton, New York.

Joel Griffis had a large family with two wives. His first wife Margery Gillespie, was Harold’s paternal great grandmother. Joel and Margery had eight children. His sixth child, William James Griffis, was the grandfather of Harold Griffis. After Margery passed away in 1850, he remarried Anna Ostrom. Joel and Anna had four children. He was an older father for his four children with Anna.

Family Tree Between Joel Griffis and John Sperber and Harold Griffis

Joel had a series of careers. Joel was a farmer during his first marriage. When he remarried in the early 1850s, he moved to Kingsboro, which was part of Johnstown census district. He was a teamster during his second marriage.

A teamster was a person who drove a team of horses or oxen, especially to transport freight. The driver was referred to as a “teamster” because he was the one who managed the team of horses pulling the load. In the late 1800s, the average teamster often worked 12-18 hour days, 7 days a week. [14]

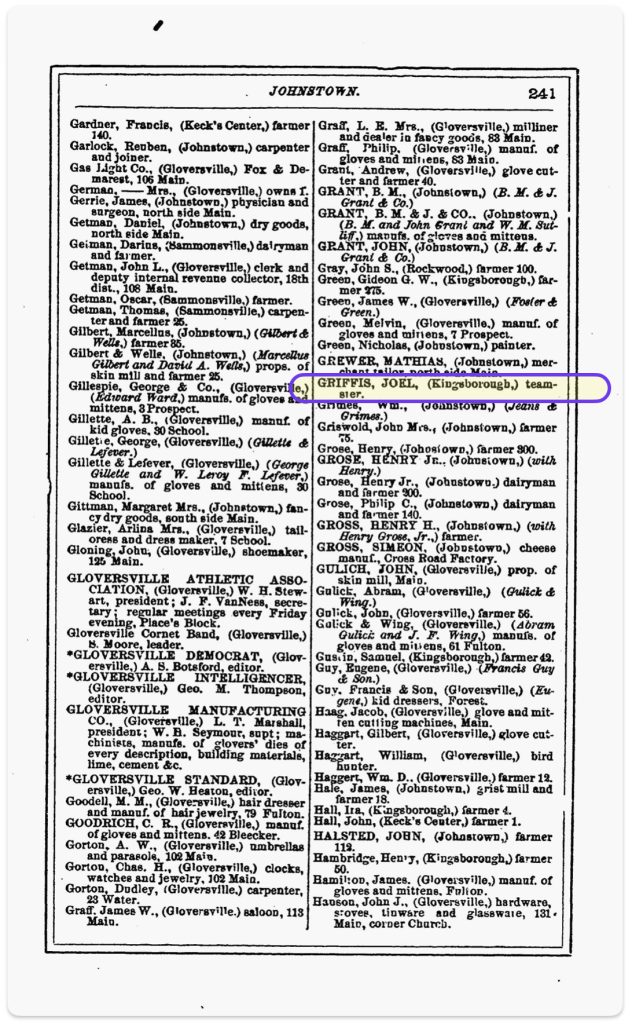

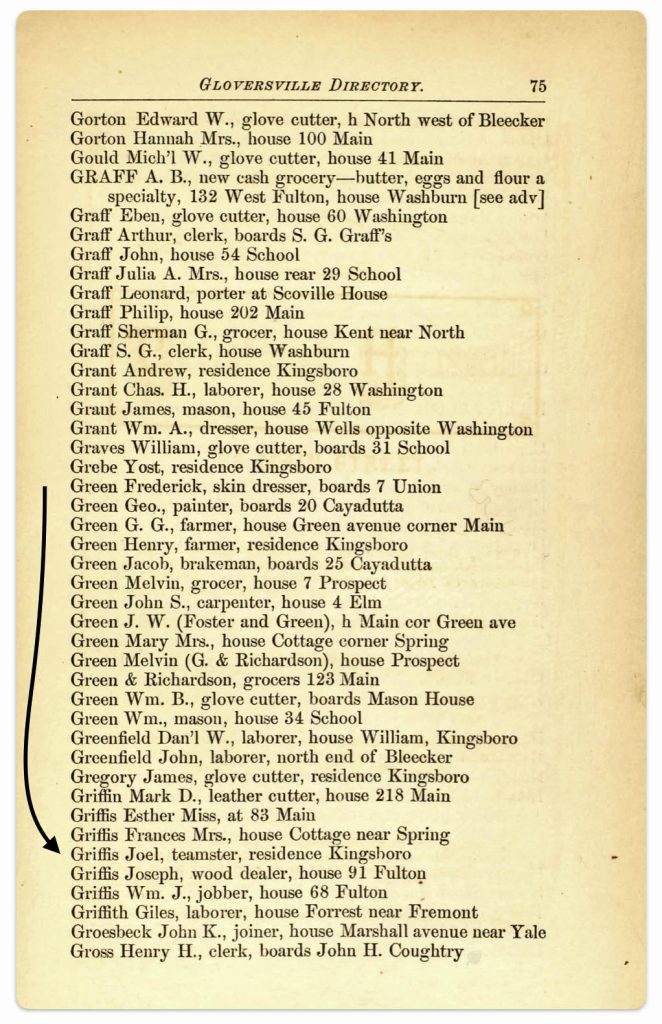

In the 1870 Federal Census, Joel indicated that he was a teamster. [15] Joel’s occupation was also listed as a teamster in City Directories in the late 1860s and the mid 1870’s. [16]

Evidently, Joel saw a chance for monetary gain by leasing the rights to the horse rail line given his teamster work experience.

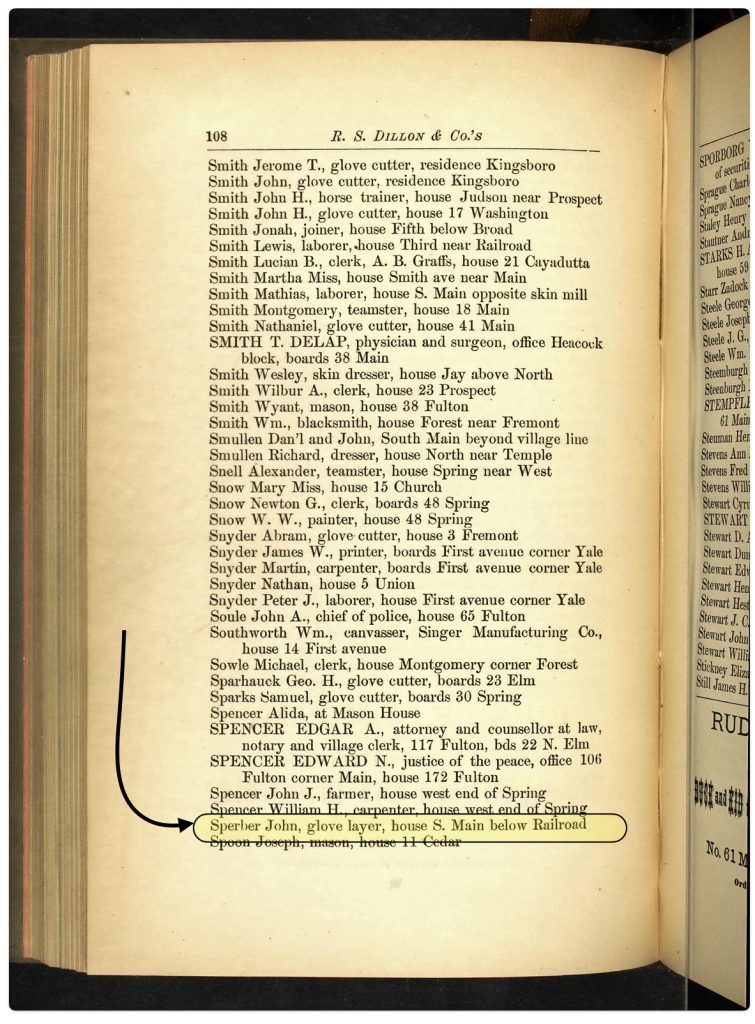

John Sperber listed himself in the Gloversville Directory in 1875. He indicated he was a glover layer and his residence was on’ S. Main Street below the railroad‘.

John Sperber in the 1875 Gloversville Directory

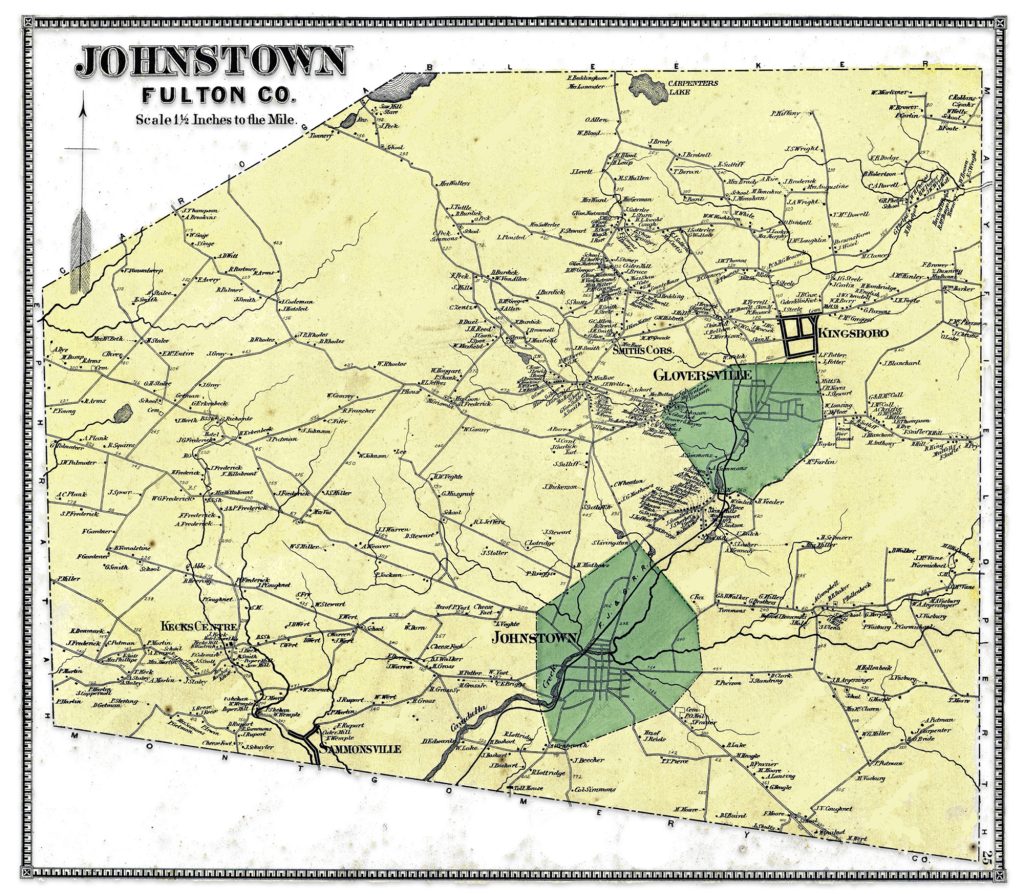

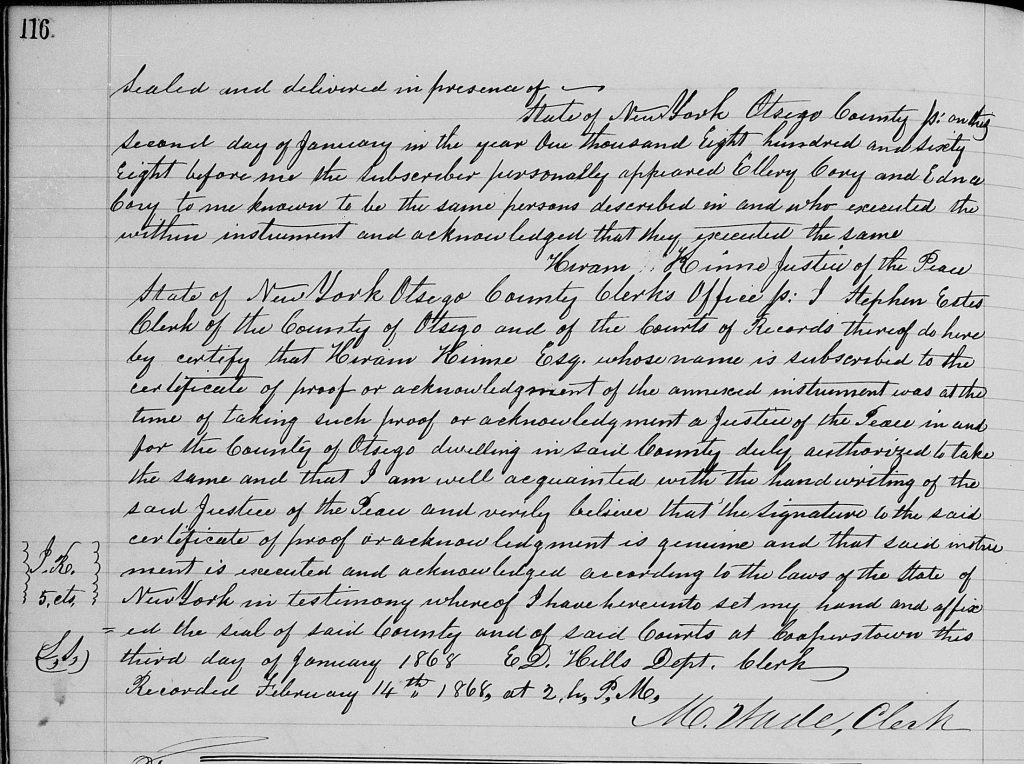

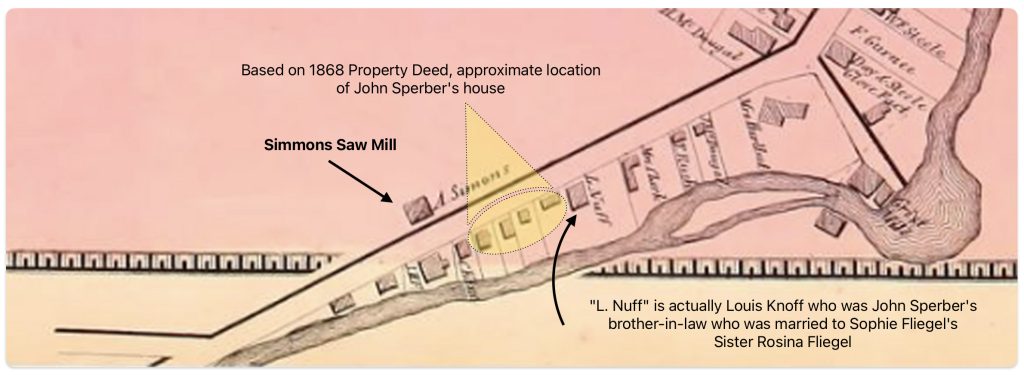

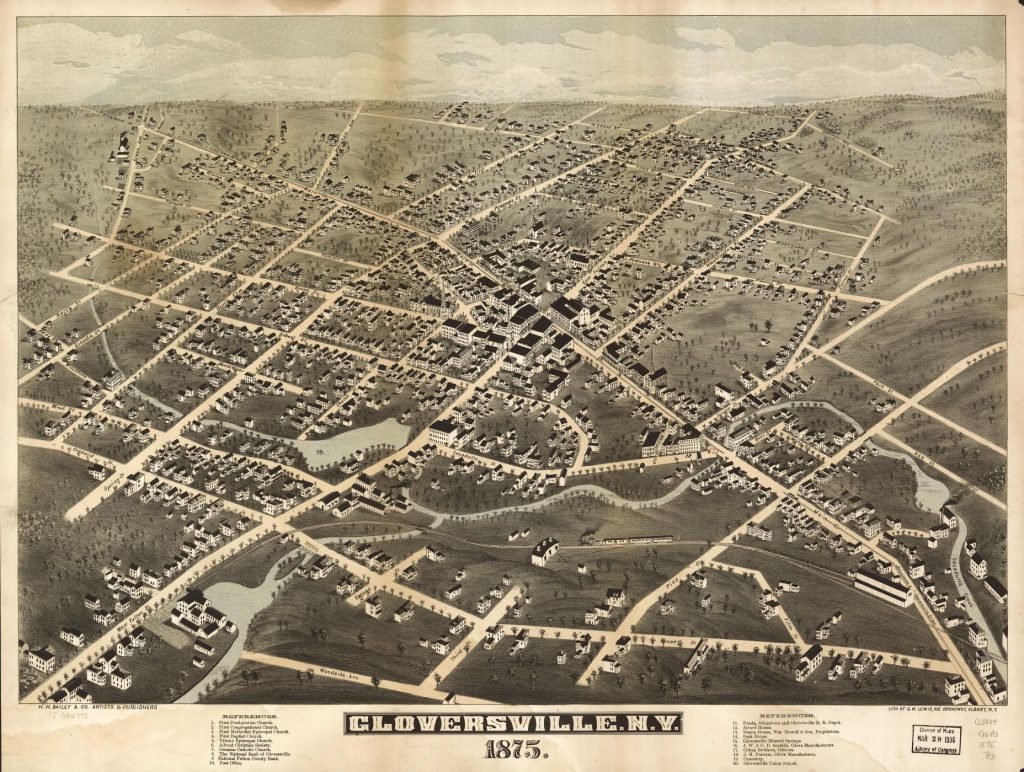

The following perspective map of Gloversville in 1875 provides a graphic portrayal of where the Sperber household was in context of the rail lines in the town.

Map One: Perspective Map of Gloversville 1875

John and Sophies’ house was located on South Main Street past Broad Street. While their household is just beyond the outline of the lower right hand corner of the map one, map two provides an illustrative view of the proximity of the two rail lines to their house.

Map Two: Close Up Section of 1875 Perspective Map Gloversville

Source: H.H. Bailey & Co, and George W Lewis. Perspective Map of Gloversville, N.Y. 1875, Albany: H.H. Bailey & Co., 1875 Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/75694778/

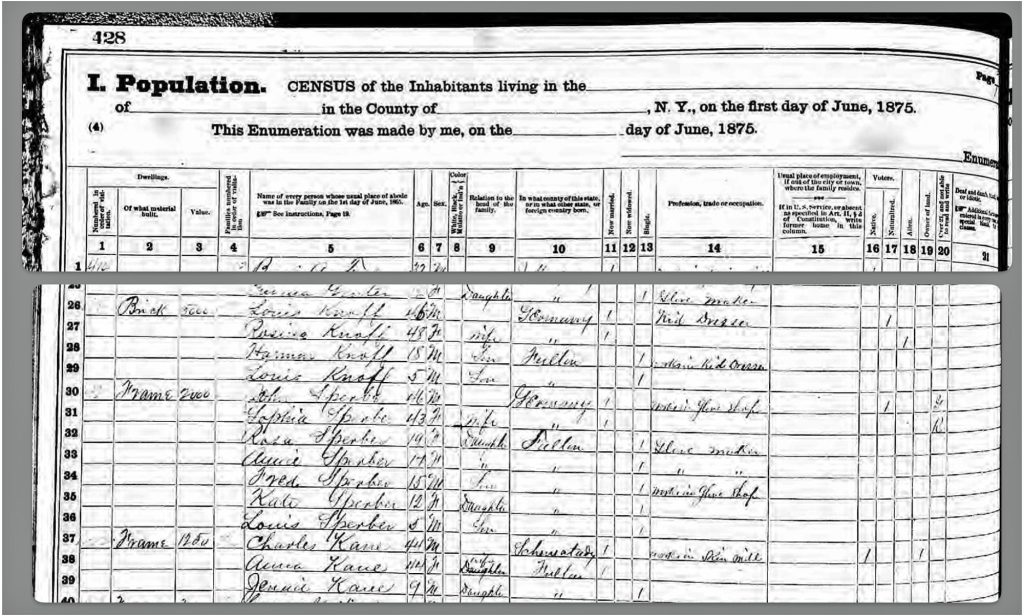

One of the next door neighbors of the Sperber family in 1875 was the Knoff family. The Knoff family lived in a brick house. John Sperber’s house was wooden frame house. As previously mentioned, Louis Knoff was John Sperber’s brother-in-law. Louis had a successful tanning business adjacent to where he lived.

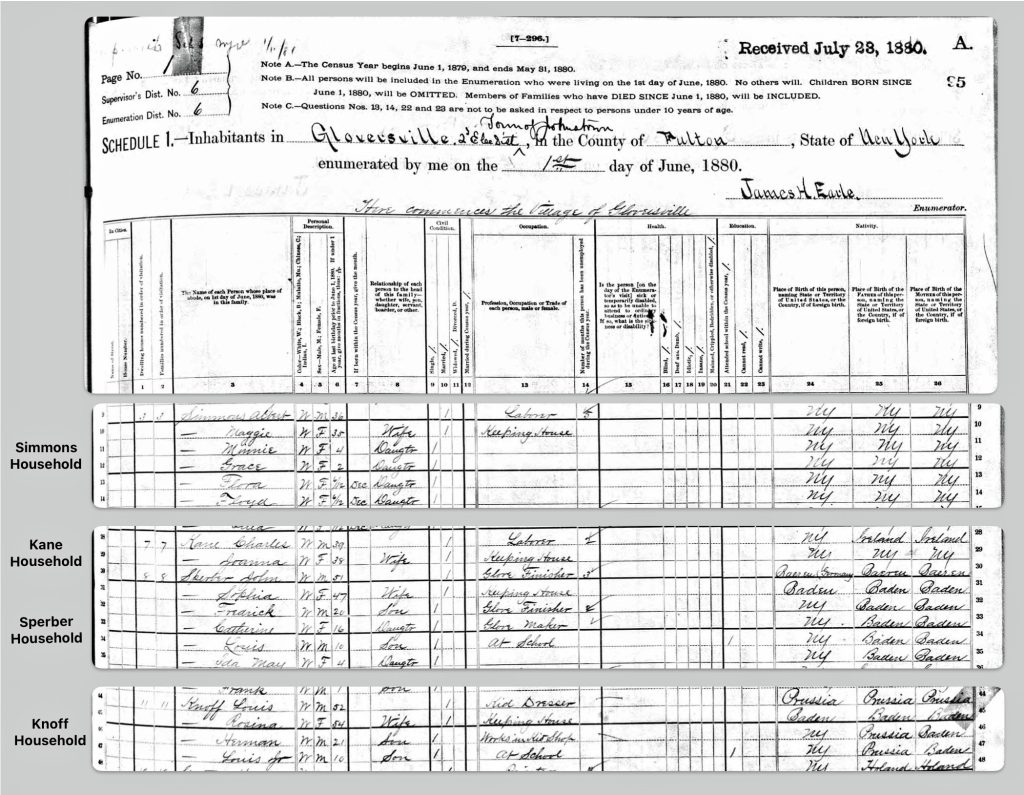

Adjacent to or across the street from the Sperber’s household was the household of Charles Kane. Kane’s property becomes meaningful when we discuss a land indenture associated with Sophia Sperber in the 1880s. The census enumerator canvassed the Kane household after he had canvassed the Sperber household.

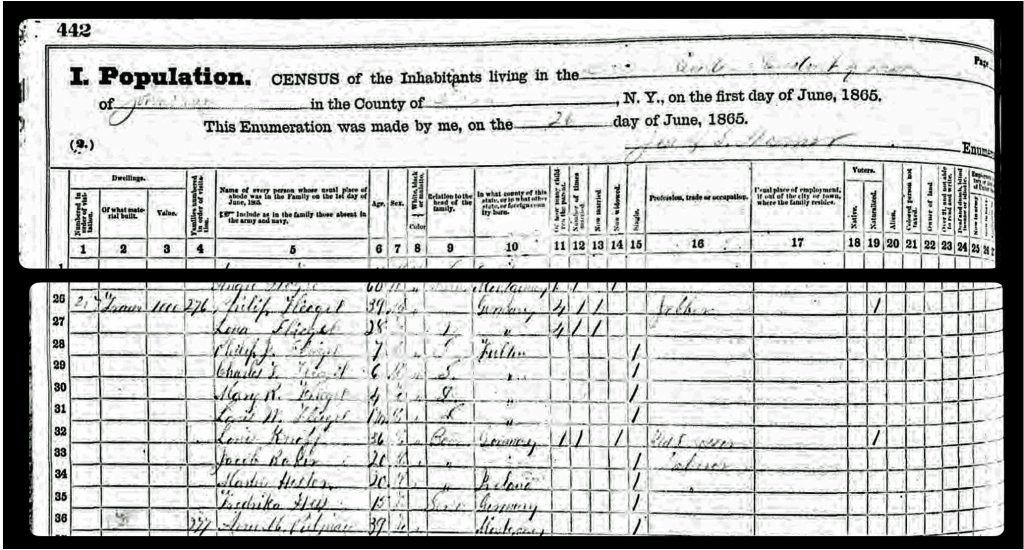

Census Two: The Sperber and Knoff Families in 1875

John and Sophia’s household in 1875 contained young working adults and children. Rose was 19 and was a glove maker. Annie was 17 and also working as a glove maker. Young Frederick was 15 and was working in a glove shop. Kate is 12 and presumably in school. Louis was 5 years old.

In 1875 John was reported to be 46 years old and Sophie was 43. It is interesting to note that the census enumerator indicated that John could not read nor write but placed a “G” in column 20, perhaps signifying that he could read and write German. For Sophia, the census enumerator indicated that she could read english, annotating the column with an “R”.

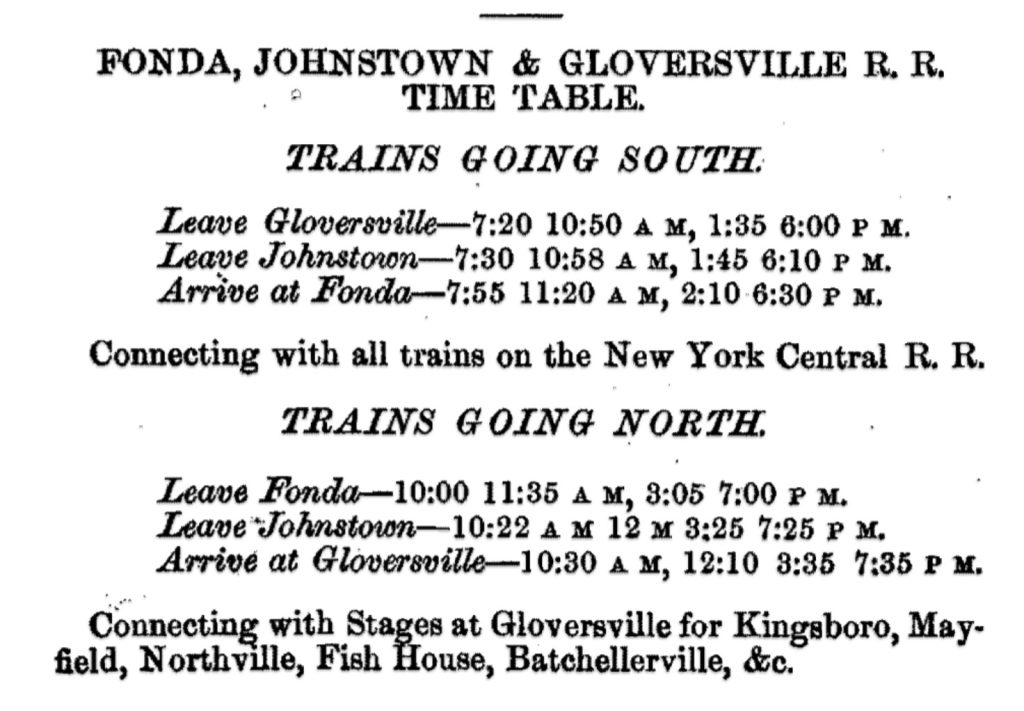

The Sperber and Knoff families did not live in a bucolic tree lined neighborhood. They undoubtably had daily reminders waking up in their homes to the effects of the tanning and glove making industry as well as daily movement of people and products on railways. They had a horse driven train railway in front of their houses on South Main Street. The steam railway, with noisy locomotives and creaky rails, ran on a frequent daily basis behind their properties, as reflected in the 1873 advertisement below..

Fonda, Johnstown & Gloversville Train Schedule 1873

The Cayadutta Creek was also behind their homes. “The Cayadutta … continued to receive the effluent from the skin mills strung along its course. That creek smelled and foamed and irritated, both literally and figuratively, for another century; and as more and more plants were built along and sometimes over it, flooding became a problem.” [17]

The comparison of the geographical layout of Gloversville and Johnstown with other industrial towns in the Mohawk valley were strikingly different. In the Mohawk river towns of Utica, Amsterdam and Little Falls, factory enclaves were separate from residential areas. Factories were clustered along the river and rail lines. Residential areas were in other areas away from the areas of production. In Johnstown and Gloversville, glove shops and even tanneries were interspersed next to middle class frame houses. [18]

Through the 1880s and 1890s very few streets were paved and most were paved with cedar blocks. Major thoroughfares were paved with bricks. [19]

Toward the end of the 1870s, the Sperber family experienced the extremes of sorrow and happiness. They had their sixth child Ida Mae, my great grandmother; they witnessed the loss of one of their daughters and the marriage of another daughter. John and Sophie had their sixth child, Ida Mae Sperber, on May 30th 1876. [20] Anna Sperber, their second daughter, died of unknown causes on November 15th, 1876. Anna was only 19 years old. At the time of her death, she worked as a glove maker. [21]

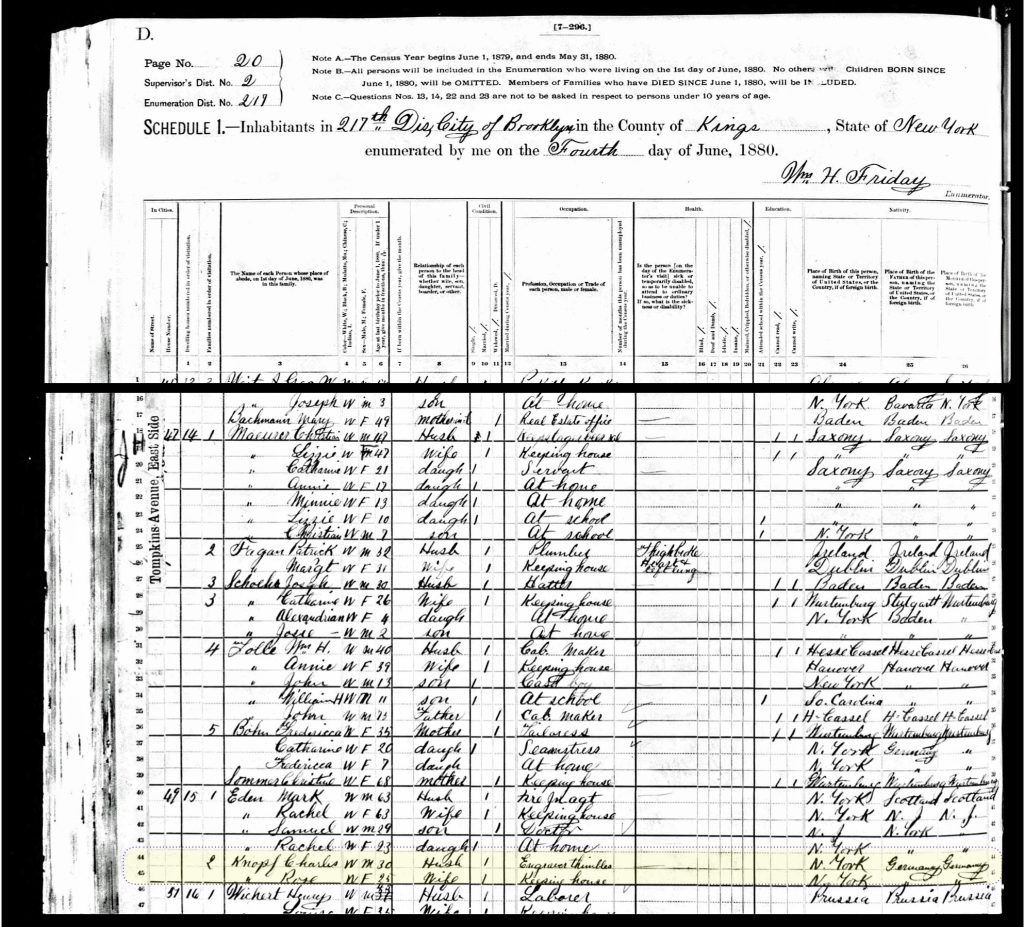

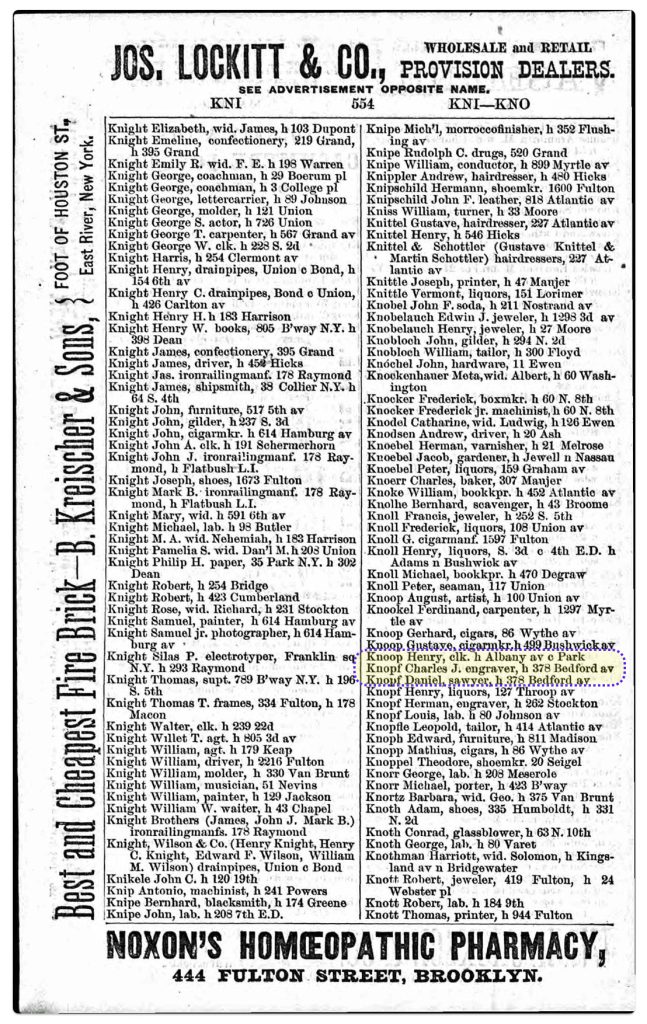

In 1876, at the ge of 20, Rose Sperber married Charles Knopf. Rose moved to Brooklyn, New York where Charles had an established business and where his family lived. [22]

Charles was an engraver or more specifically, a chaser. A chaser is a specialist silversmith who has perfected the complimentary skills of chasing and repoussé; the techniques of applying a three-dimensional decorative pattern to the front and back surfaces of a piece of work. [23]

The 1880s: Continued Prosperity and Children Growing Up

“Both Gloversville and Johnstown took on an aura of success in the decade of the 1880s as glove manufacturers began to produce increasing quantities of fine dress gloves. Skins mills were still concentrated along the creek and railroad corridors. The brick factories flaunted success and were still scattered throughout both towns. … The expansion of new glove shops in the 1880s occurred principally in Gloversville so that by 1890, there were roughly twice as many shops in Gloversville as in Johnstown. [24]

The rise of the factory system in the late 18th and early 19th centuries revolutionized manufacturing by centralizing production, dividing work processes into specialized tasks, and using machines to automate processes. The factory system represented a major shift from the cottage industry, enabling mass production, using standardized processes and unskilled labor, and achieving unprecedented output and efficiency that revolutionized manufacturing. [25]

“Fulton county’s tradition of piecework rates and independent contractors, which marked the industry in the early years, gave way to a form of independence that did not lead to modern factory organization. … (Smaller shops and home shops) began to specialize on different operations. This separation of work into different types of shops became even more pronounced in future years. Gloves were sent to special shops, some of them quite small, for different tasks like making and laying-off, or those like hemming, silking, and sewing buttonholes that remained handwork operations. The nature of the work limited real organization of factory work beyond the 1880s factory design which placed different operations on descending floors to create a smooth flow from leather to glove. Cutting – and sewing – remained an art and a craft.” [26]

Even as factories were growing, home glove shops continued to flourish. The tradition of piecework rates, artisanal skill, and independent small home based contractors continued. Many home shops began to specialize in different operations of glove making or creating gloves using different types of leather that were introduced in glove making.

The wages of Fulton county glovers set nationwide industry standards. Beginning in the 1870s and into the twentieth century, glove makers in Fulton County gradually relinquished their dominance in the manufacture of heavy work gloves to glove shops in the central and western parts of the United States that paid cheaper wages. Attention in Fulton county was focused on the making of fine men’s and women’s gloves which used more exotic skins and required greater artisanal care and skill in leather cutting and sewing.

In addition, women and children in their teens continued to work making gloves at home. Outside of Fulton County, the harsh realities of child labor, overcrowded tenement homework, and unsafe factory conditions were major catalysts for the labor battles and unionization efforts that defined the 1880s in America. Reformers increasingly drew attention to these issues and pushed for legislative changes to protect workers, especially women and children. While progress was gradual, the 1880s marked an important turning point in the fight against worker exploitation. [27]

While labor battles and legislative reform were waged across the nation, it did not have a predominant effect in Gloversville and Johnstown. The nature and structure of the glove making industry, the preponderance of home glove shops, and the economic independence of women workers accounted for the lower levels of discontent.

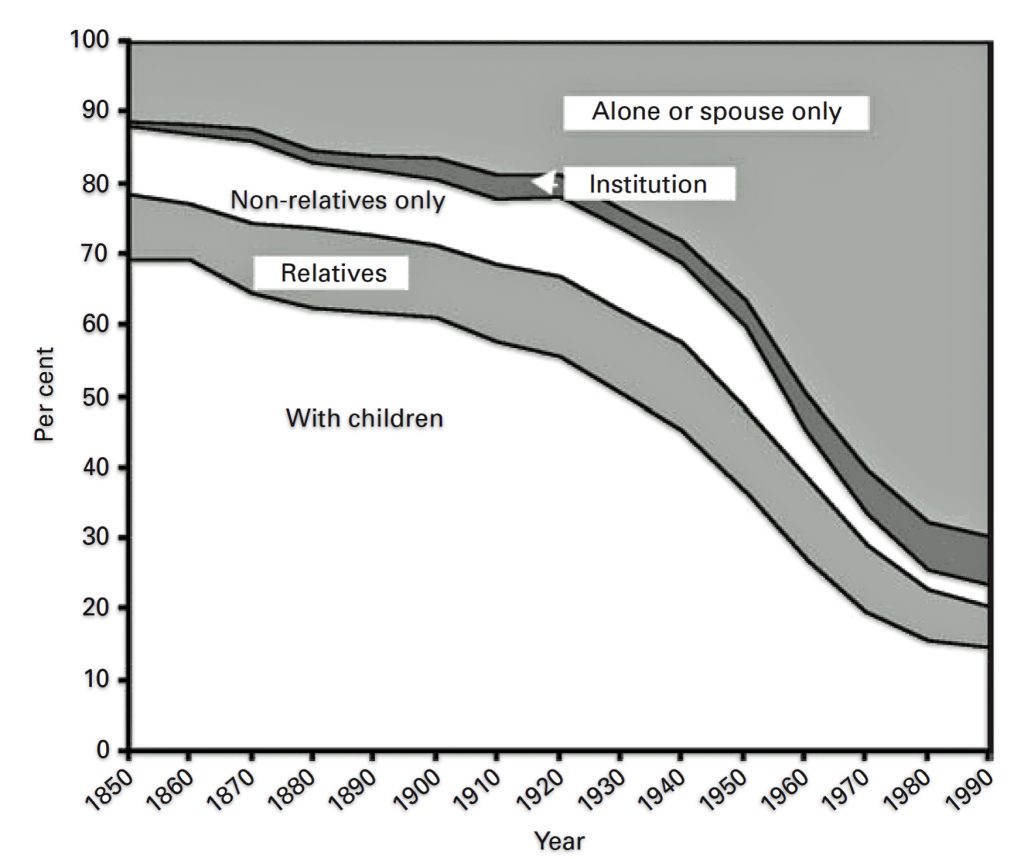

“Homework in the county expanded even as the number of factories increased. Single women often started in factories, married, and after the birth of the children began sewing at home. Older women preferred to sew at home. Spinsters or widows chose either factory or homework at will. As children left home, women returned to the factories. …(B)oth classes of workers shared a commonality: they remained very independent employees.” [28]

Most families in Fulton county were touched by the glove making industry or industries related to glove manufacturing. Virtually all members of a family at one time or another assumed a role in the glove making process. One could always ‘go back’ to the jobs in the glove making work processes. This is evident with the Sperber family. As reflected below in 1880, with the exception of Sophia Sperber, everyone in the Sperber household above the age of 13 was working in the glove making business.

The work processes and the nature of the business operations associated with glove making and glove sales were seasonal in nature. Retailers typically did not order gloves for the following winter until late spring or summer. Salesman were not sent out during the winter months. Factories were busy in the summer months and continued to have heavy work schedules in the fall. Factories were typically closed for a week in the summer and then usually closed the month of December.

In the winter time , the factories were dark. Glove cutters and makers could not see well and companies that relied on natural light worked shorter days. Many shops operated for only seven to eight months. A few of the bigger shops worked for about nine months. [29]

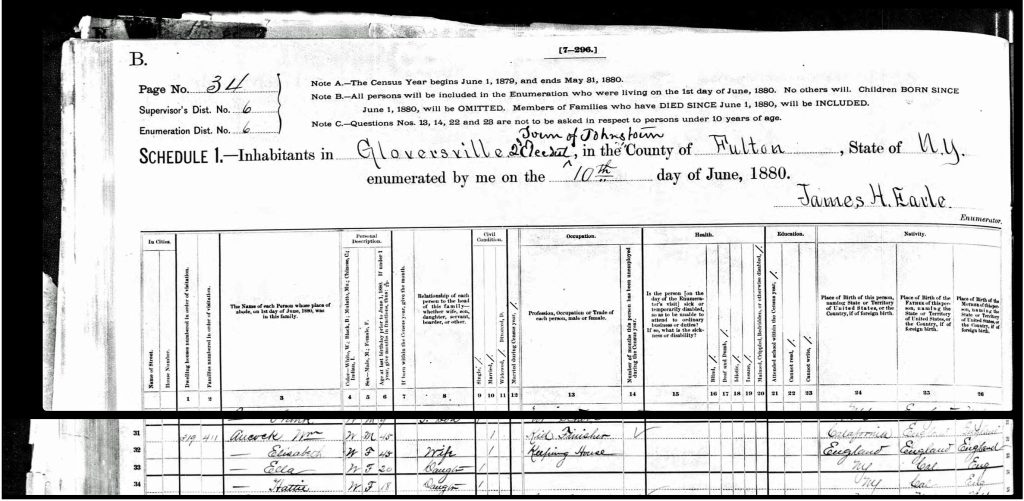

The seasonal nature of glove manufacturing is reflected in the tabulations of the census enumerator in the 1880 census for the Sperber family. The 1880 U.S. Census is well-known for being the first census to report a number of new facts about individuals being enumerated. [30] One of those new facts was found in column 14: the census documented the number of months someone was not employed in the prior year.

The seasonal nature of work in the glove making business is reflected in the work history of Sperber family members in the 1880 Federal census. The Sperber household had three family members working the glove making business in 1880. John Sperber was identified as a glove finisher and was not working for three months in the prior year. His son Frederick was 20 years old and living at home. He also was a glove finisher and had not worked for two months in the prior year.

John’s 16 year old daughter Kate, was a glove maker and worked the entire year. Kate may have worked from home sewing gloves. Larger glove manufacturers had a longstanding business arrangement of delivering packets of cut gloves to glove makers working from home shops and picking the finished sewn gloves up. [31]

Census Three: The Sperber and Knoff Households – 1880 Federal Census

Kate, at 16, was working. Louis was in school at the age of 10 and young Ida was 4 years old. The average grade level for children in America in the 1880s was around 8th grade. In the late 1800s, public schools were becoming more numerous, and states were beginning to require school attendance for children aged 8 to 14, with a curriculum focused on basic literacy, English, and arithmetic skills. However, for the Sperber family, the children began work at the age of 15. [32]

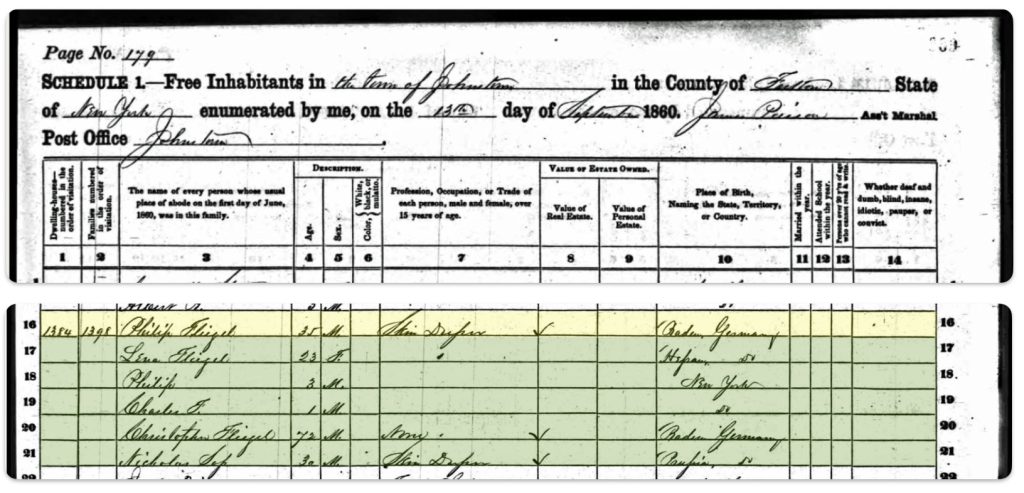

It is interesting that the census enumerator listed John and his parents’ place of birth as Baeren (Germany). Sophie’s place of birth as well as her parents is listed as Baden.

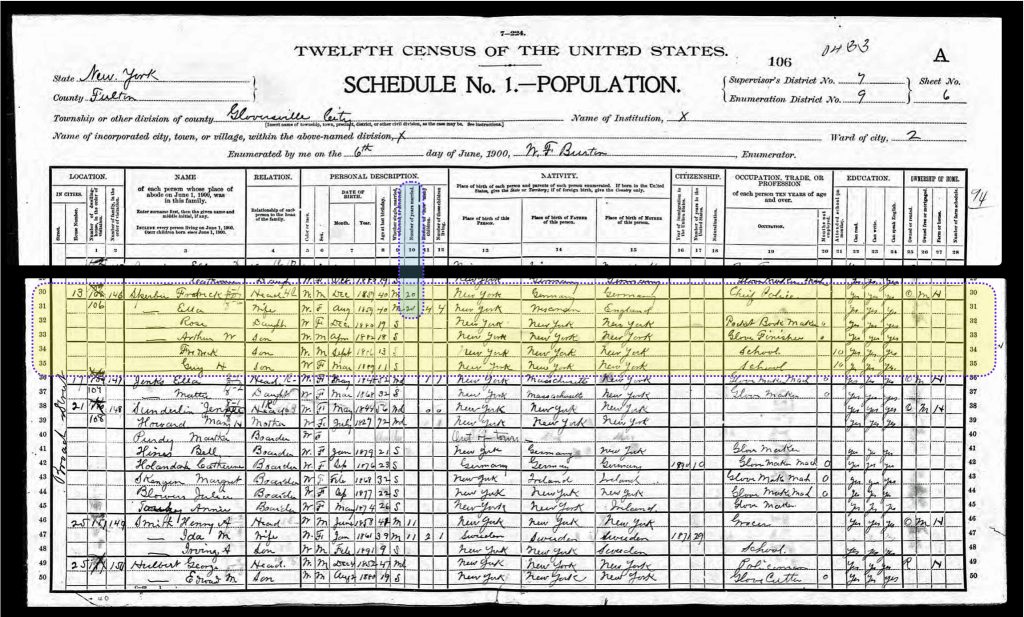

While we do not have definitive proof, Frederick Sperber married Ella Aucock in 1880. Both were 20 years old when they married. Since the census was taken on June 1, 1880 and Frederick and Ella were still living with their parents in June [33] , they probably were married after the census was taken. Fred and Ella’s first child, Rosa, was born in December 1880. [34] After 1880, the Sperber household had three remaining children at home.

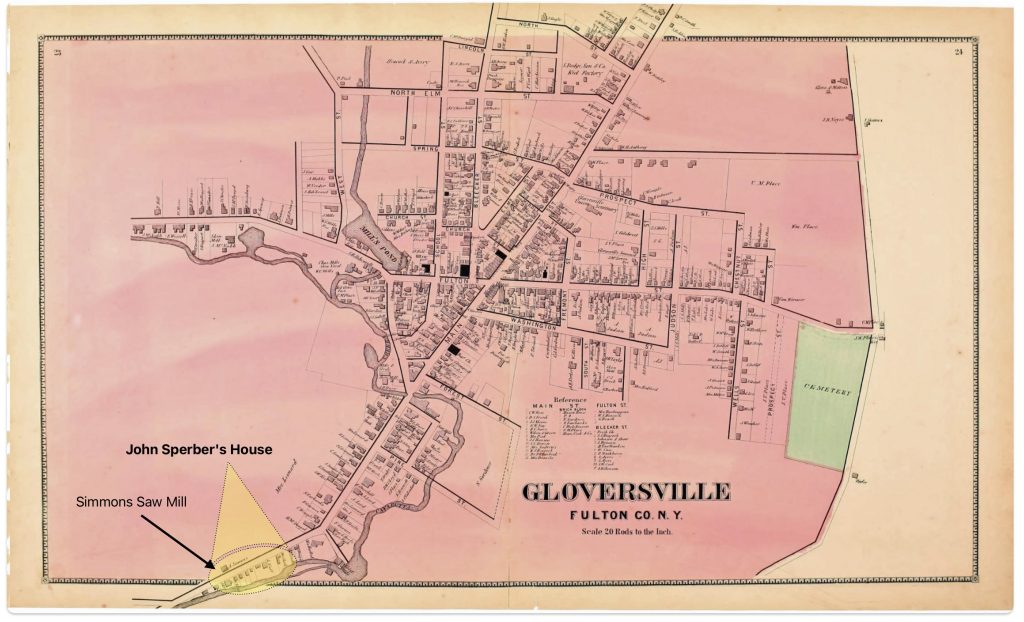

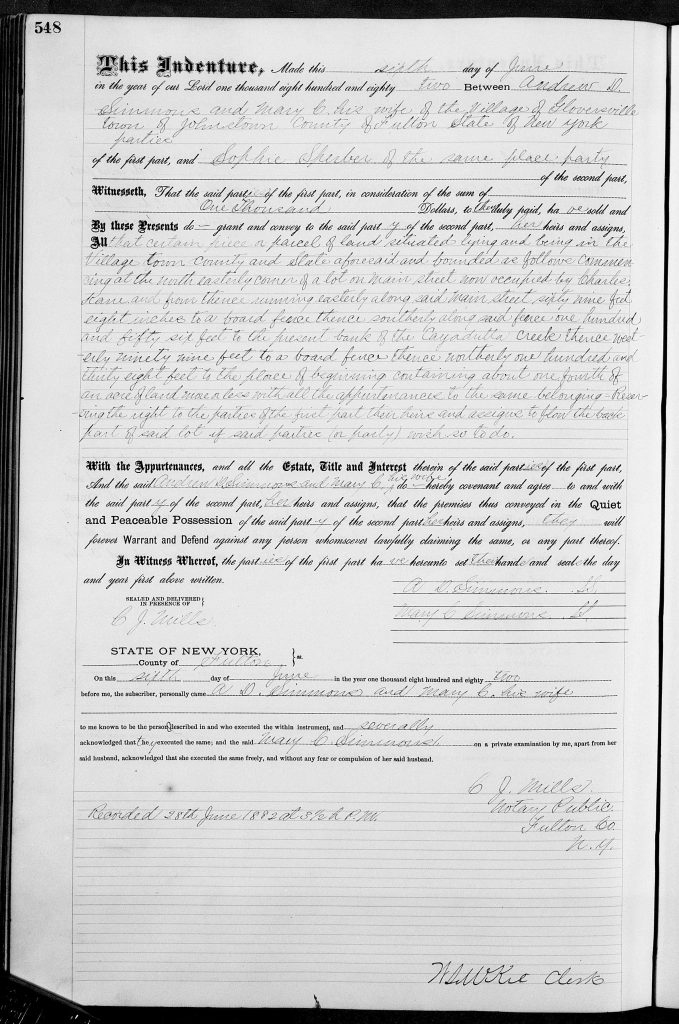

In 1882, John and Sophie Sperber purchased approximately one quarter of a parcel of land from Andrew D. Simmons, in the name of Sophia Sperber. [35] The following is the description of the land. It appears that they purchased the adjacent piece of property that was occupied by the Kane family, listed in the 1880 census. It is not known what they did with the land. It is also not known why they purchased the land and put the title under Sophia’s name.

| “This indenture made this sixth day of June in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and eighty two between Andrew D Simmons and Mary C. his wife of the village of Gloversville town of Johnstown County of Fulton of New York parties of the first part and Sophie Sperber of the same place . “Witnesseth that the said parties of the first part, in consideration of the sum of one thousand dollars to them duly paid have sold and by these presents to grant and convey to the said party of the second part, her heirs and assigns all that certain piece or parcel of land situated lying and being in the Village town county and State aforesaid and bounded as follows commencing at the northeasterly corner of a lot on Main Street now occupied by Charles Kane and from thence running easterly along said Main Street sixty nine feet and eight inches to a broad fence thence southerly along the fence with one hundred and fifty six feet to the present bank of the Cayadutta Creek thence westerly ninety nine feet to a board fence thence northerly one hundred and thirty eight feet to the place of beginning containing about one fourth of an acre of land more or less with all the appurtenances to the same belonging . Reserving the right to the parties of the first part their heirs and assigns to flow the back part of said lot if said parties (or party) wish to do so.” |

Land Deed Between A.D. Simmons and his wife and Sophia Sperber

Source: New York Land Records Fulton County, Volume 59, Page 548, 28 Jun 1882, Grantor Andrew D Simmons and Grantee Sophia Sperber

John Sperber: the Glove Maker

Based on stated occupations documented in a variety census and town directories and two of the surviving family photographs of John Sperber depicting his work environment in the 1880’s or 1890’s, we know he was in the glove making business for most, if not all, of his working life in America. The following table depicts the various roles within the glove making work process that John Sperber has identified with throughout his life.

Occupations of John Sperber Based on Sampled Years of Census Enumeration and Gloversville Directories

| Year | Self-Stated Occupation | Age | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | Skin Business | 32 | Federal Census |

| 1870 | Laborer | 42 | Federal Census |

| 1873 | Glove Finisher | 45 | Gloversille Directory |

| 1875 | Glover Layer | 47 | Gloversville Directory |

| 1875 | Working in Glove Shop | 47 | N.Y. Census |

| 1880 | Glove Finisher | 52 | Federal Census |

| 1881 | Glove Maker | 53 | Gloversville Directory |

| 1884 | Glove Cutter | 56 | Gloversville Directory |

| 1885 | Glove Finisher | 57 | Gloversville Directory |

| 1887 | Glover | 59 | Gloversville Directory |

| 1888 | Glove Finisher | 60 | Gloversville Directory |

| 1889 | Glover | 61 | Gloversville Directory |

| 1890 | Glover | 62 | Gloversville Directory |

| 1900 | Sewing Machine Operator Gloves | 62 | Federal Census |

| 1903 | Glover | 65 | Gloversville Directory |

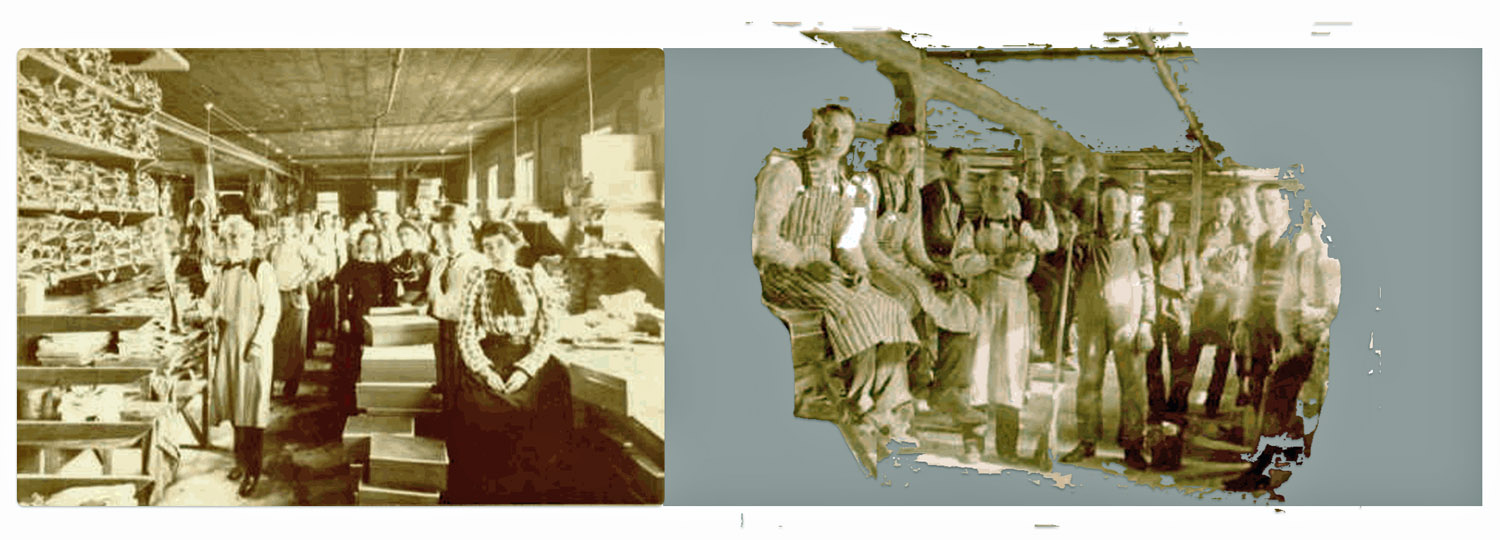

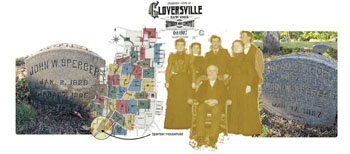

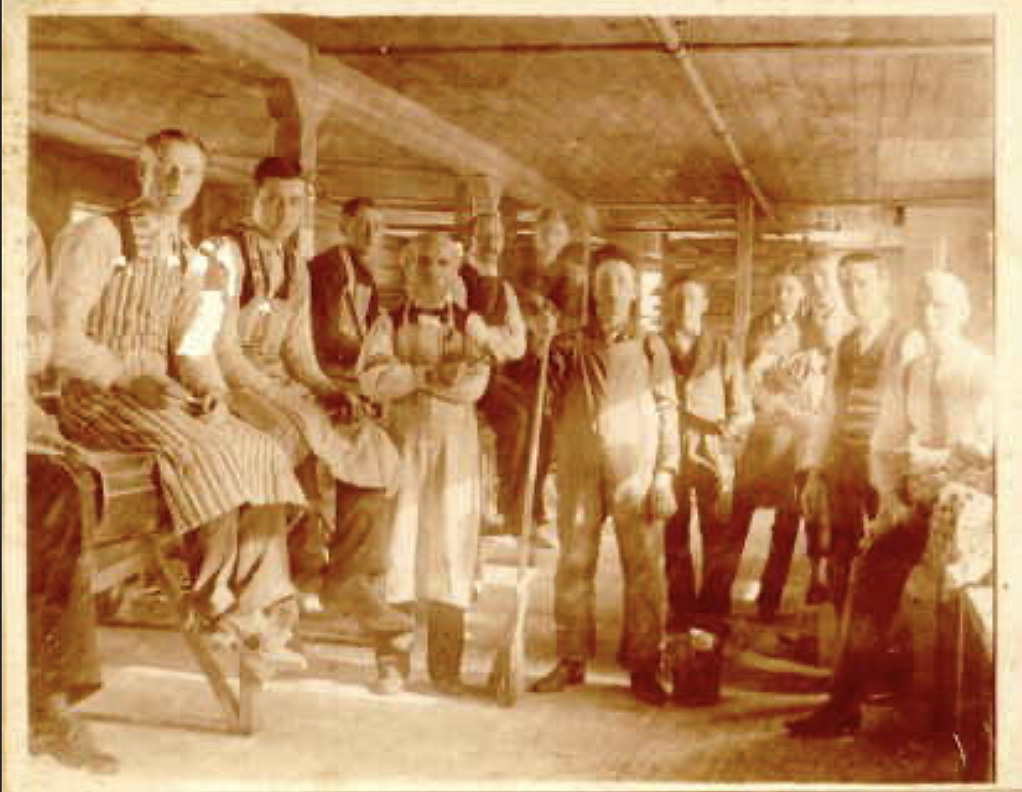

Two of the three existing photographs of John Sperber were taken at Littauer’s Glove factory in Gloversville. The photographs were not dated but contained hand written inscriptions, indicating the photographs were taken in the ‘laying off room’. They were probably taken in the 1890s.

In the first photograph below, John Sperber is standing in the foreground to the left. It appears that John and his fellow workers are all standing in an area where finished gloves were put into boxes. To the left of John there appears to be a glove iron on a work bench.

“Littauer Laying Off Room

The second photograph below appears to be in a warehouse area of the Littauer’s Glove factory. The photograph could have been taken in the same area as the first photograph. The beams in both of the photographs look similar. “Littauer’s Laying Off Room, the shop floor” is hand written on back of photo. John Sperber is standing with his arms folded in the center foreground of the photo.

In both of the photographs, John Sperber is dressed in a suit, as are the other men in the photographs. John appears to be standing next to a young man with a broom. Perhaps a young man that is starting his career in glove making as a sweeper in the factory.

David Pincombe was born in Gloversville in 1959. He is not related to our family. However, similar to various branches in the Griffis family, his family worked in the glove industry in Gloversville for many generations. [36] David made a perceptive observation about the different work roles in the glove making process. He remembers his great grandfather’s pride in his work “laying off” gloves:

“[Great] Grandpa and all the men – that was a prestigious position. They dressed up to go to work and lay off gloves. Jacket, suit, vest, tie, stick pin, watch chain, the works!”

The photographs of John Sperber illustrate that pride and sense of professionalism.

Littauer’s Laying Off Room, the Shop Floor

The term “laying off” in the context of glove manufacturing refers to a specific, final step in the glove-making process.T he leather pieces are cut to size and sewn together inside out. After the gloves have been sewn inside-out and they turned right-side out. This is done manually in a process called “turning”.

After turning, the gloves move to the “laying off” step where final shaping occurs. Although the glove materials like leather will form to the hands, this step helps bring them into their proper fitted shape. The glove is then put on a hand-shaped iron based on its size. The irons are very hot. The steam heat helps relax the leather which allows the glove to stretch out to the appropriate size. Additionally, fingertips are shaped and wrinkles are worked out. [37]

The photograph below provides examples of glove irons.

Example of Three brass Glove Irons, Circa 1900

“After the gloves are made they are drawn over metal hands heated by steam, a “laying-off” process, as it is termed, and by means of which the glove is shaped and given its finished appearance.” [38]

“(T)he laying off is very hot work, because it’s a steam-generated piping [which] runs up whatever part you need to lay off. It’s either the hand or the thumb. And you put these gloves on this [the piping] and the bronze is scorching hot. Heaven help you if you touch it! And that stretches it and smooths it, and then it goes very nicely, put together in a pair, and stacked, and dried, and then they go in to be polished.” [39]

Based on the two photographs, we know that John Sperber worked at the Littauer Brothers Glover Manufacturing company in the 1890s. We do not know when he started working at the Littauer’s. John possibly worked for Littauer for most of his career.

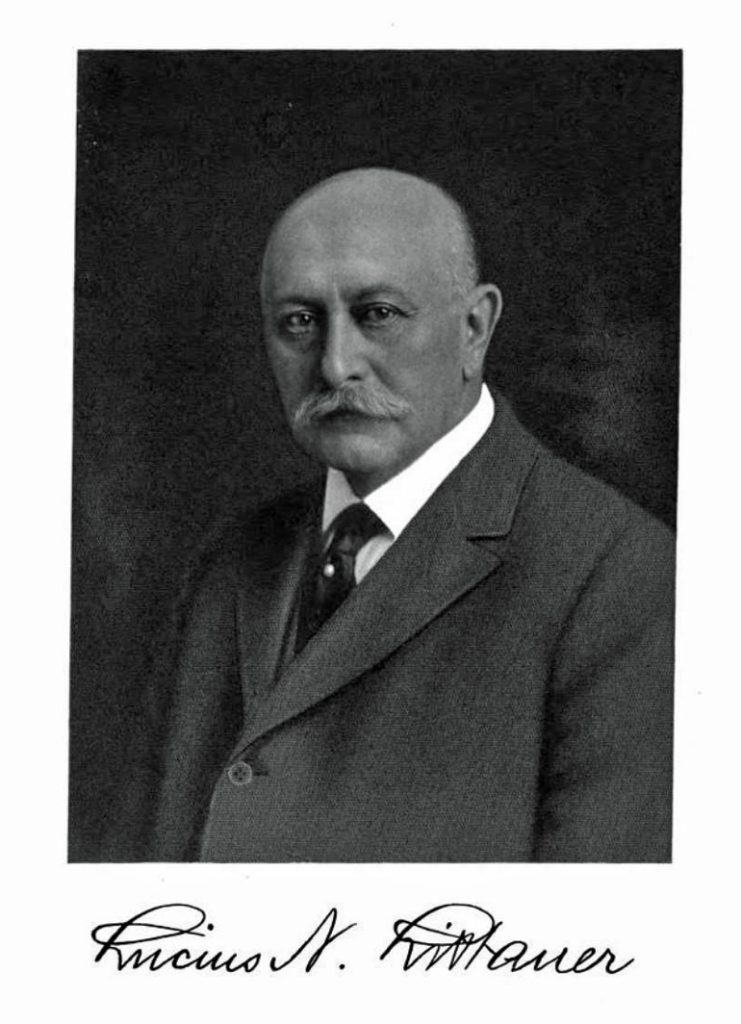

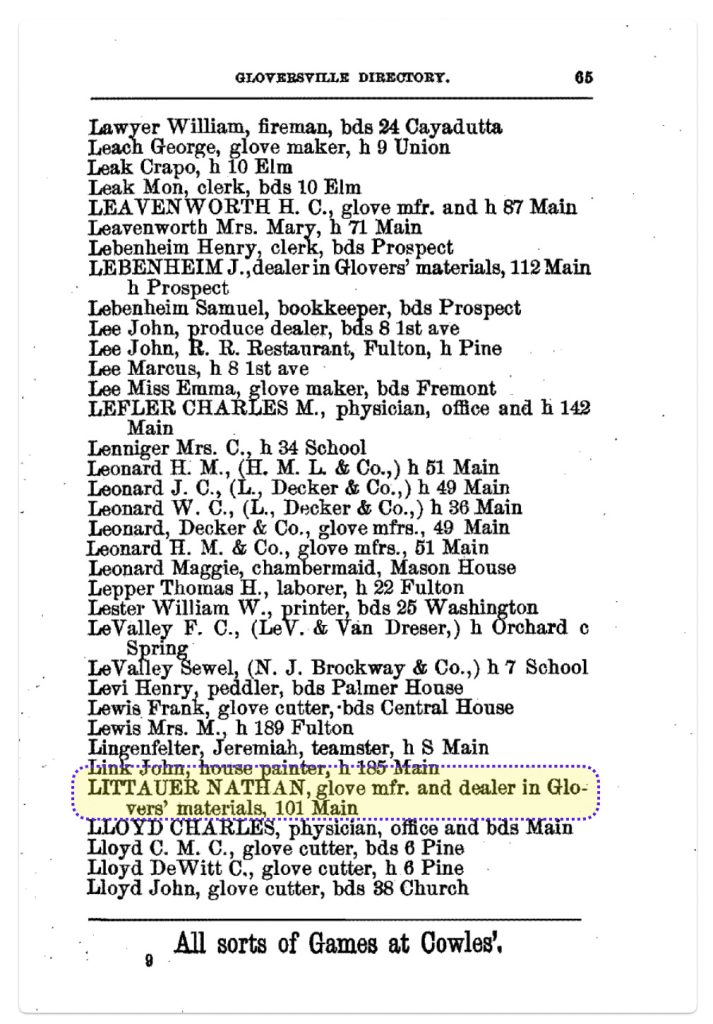

The Littauer Glove Manufacturing company was founded in 1866 by Nathan Littauer, a Jewish immigrant from Breslau, Germany who settled in Gloversville, New York in 1846. Nathan started out as a peddler selling dry goods, and by 1855 had established a dry goods store in Gloversville and began manufacturing gloves. In 1860, he set up a sales office in New York City to market the gloves, and in 1866 moved there with his family while continuing the glove manufacturing in Gloversville. [40]

Nathan’s son Lucius Nathan Littauer, born in Gloversville in 1859, joined his father’s glove business after graduating from Harvard in 1878 and after a stint as Harvard’s football coach after graduation. Nathan’s roommate in college was Teddy Roosevelt. In 1883, Lucius and his brother Eugene took over the company from their father and developed it into the largest glove manufacturing enterprise in the United States. [41]

“In 1898, Littauer had been elected to his second term in Congress at the same rime that the voters of New York State chose Theodore Roosevelt their governor. This was an extremely fortunate coincidence for Littauer, for the two men had been roommates at Harvard and shared much in common: a love for athletics, both were Republicans, and both were New Yorkers. Shortly after his election as Governor of New York, Roosevelt stated publicly that Littauer was his friend and closest political adviser.” [42]

Lucius Littauer’s close relationship with Roosevelt lasted through Teddy’s presidency. Their friendship became strained when Littauer did not support Roosevelt’s decision to run as a third party presidential candidate in 1912. [43]

Portrait of Lucius Nathan Littauer

Volume 3: https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/qOApAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj93vfQneOGAxWp8MkDHQfDDNEQ7_IDegQIDxAF

Under Lucius’ leadership, the company focused on producing finer, high-end gloves using imported materials like cape leather that had previously been made in Europe. This allowed the company to capture the high-end of the American glove market. At its peak, the Littauer Glove Corporation employed 800-1000 people. [44]

As a U.S. Congressman from 1897-1907, Lucius Littauer sponsored legislation that put a tariff on fine imported gloves. This protected domestic glove manufacturers like his own company from foreign competition and enabled them to pay wages capable of supporting American living standards. [45]

In 1873, Nathan Littauer, the father of Lucius Littauer, was listed in the Gloversville city directory as a glove manufacturer and dealer in glovers’ materials at 101 Main Street. [46] This was likely his home address. An early location of the Littauer glove business before Lucius and his brother Eugene expanded the business was located on Main Street. Lucius Littauer also lived on South Main Street in Gloversville, but the factory address is not specified. The Littauer Glove Factory was relocated on West Fulton Street in Gloversville in the early 20th century.

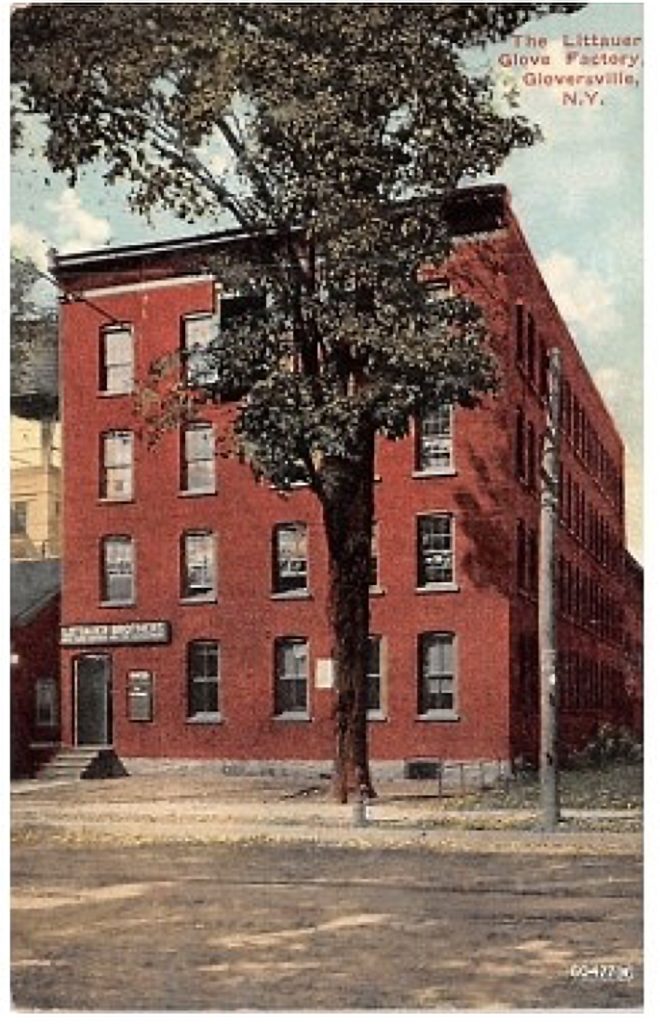

The following postcard image of the Littauer Glove Factory shows a multi-story factory building.

Postcard of the Littauer Glove Factory, Gloversville, New York [47]

The address of the Littauer Glove building in the postcard can be verified from images taken of the building in contemporary times. Below is a Google street view photograph of the building located at 124 South Main Street. While the Littauer Glove Company was sold in 1927, the building still exists and glove making activities continue. [48]

124 South Main Street, Littauer Building in July 2019

The post card illustration of the Littauer glove factory presents the front view of the company’s building from the street and does not convey the size and magnitude of the manufacturing plant.

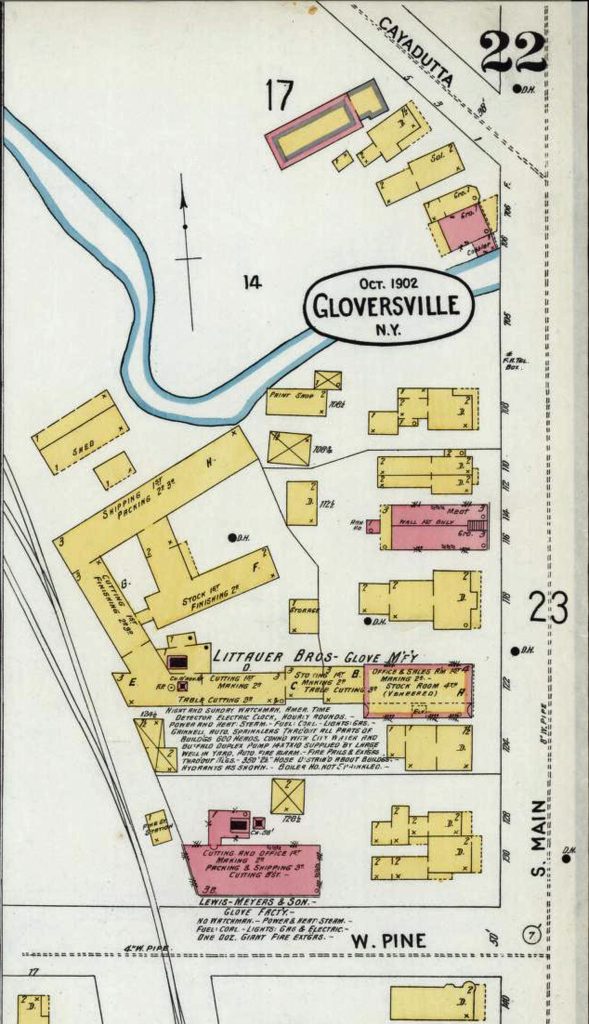

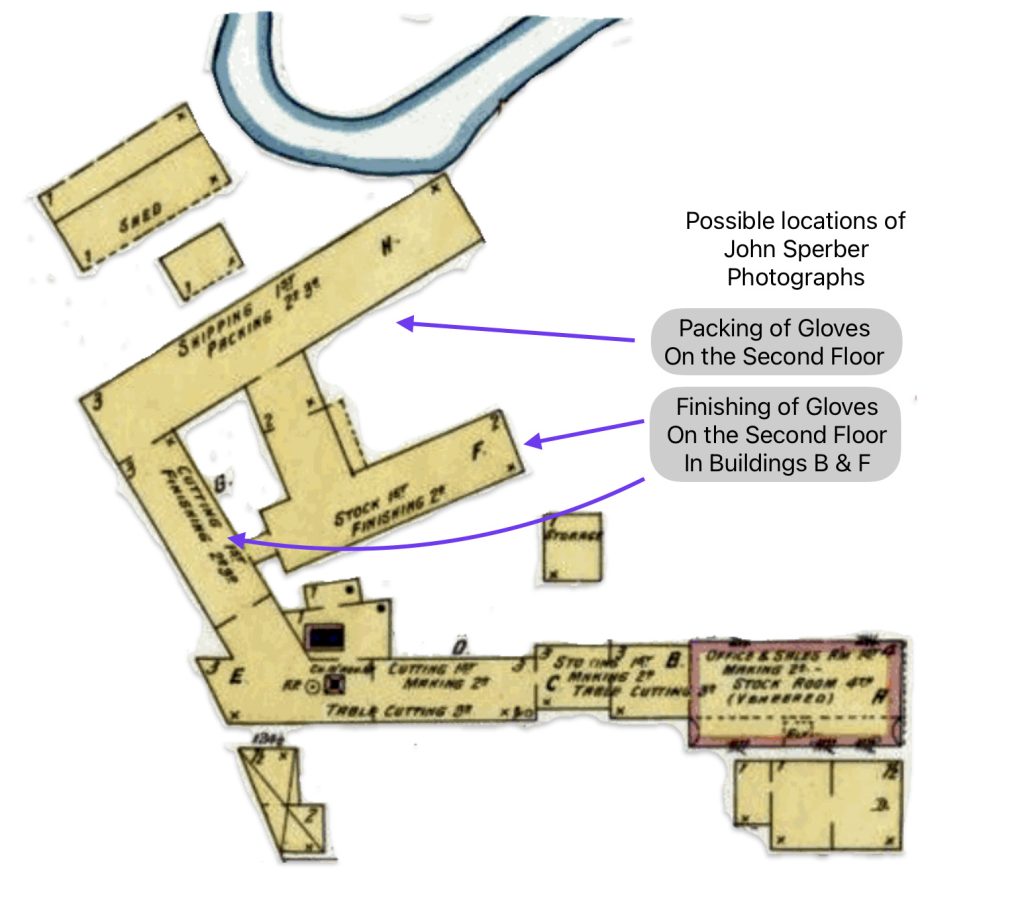

As reflected in map three below, the Sanborn fire map of Gloversville in 1902 provides an highly detailed description and functions of the buildings associated with the Littauer glove company. While originally created for insurance purposes, Sanborn maps are invaluable historic resources. [49]

Map Three: Layout of the Littauer Brothers Glove Manufacturing Company 1902

The Littauer glove manufacturing plant was located at 124 South Main street, between Cayadutta Street and West Pine Street. As reflected below, the Littauer glove factory comprised a series of multilevel attached buildings that wrapped around from Main Street in the form of an ‘E’ shaped structure.

Possible Locations Where Photographs of John Sperber were Taken

The buildings labeled “B & F – Finishing 2nd (floor)” in the map were possible places where the two photographs of John Sperber were taken. It is also possible that one of the photographs with glove boxes was taken on the second or third floor of building ‘H’ in the packing area of the company.

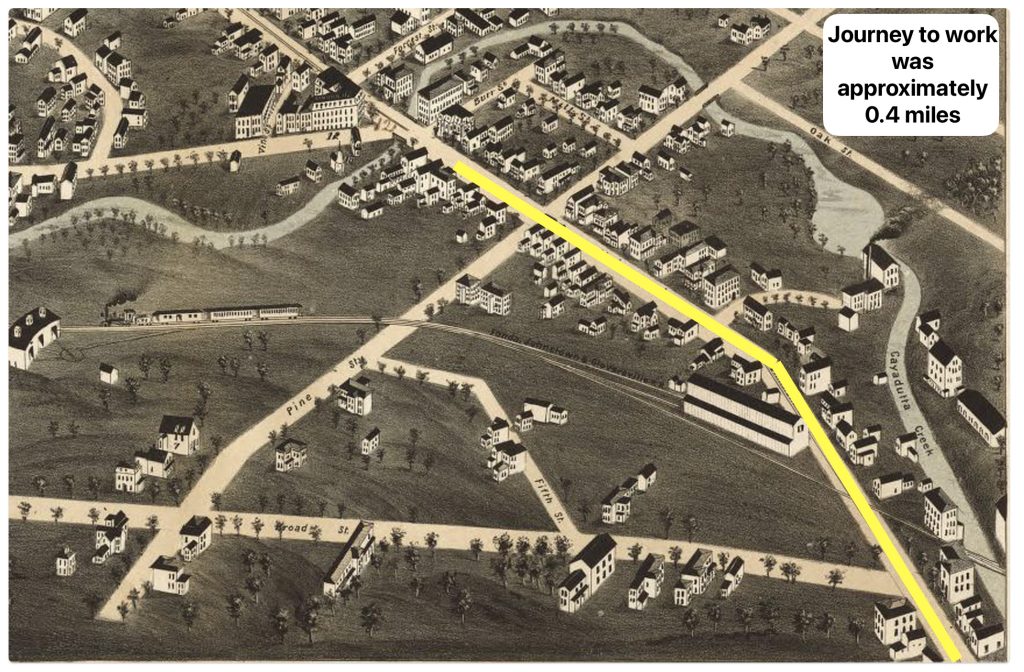

The typical travel distances to work for the working class in the mid to late 1800s were quite short, usually walkable distances. Most people lived and worked in the same local area, often walking to work. Cities were more compact before the widespread use of streetcars, subways and commuter rail. Most people lived near their workplace out of necessity. Typical commuting distances were short, usually walkable or travel-able by horse or cart. As previously indicated, tanneries and large glove factories were interspersed next to middle class and working class frame houses.

“Workers’ homes in Gloversville seemed to cluster near the center of town, in an area north of Burr Hill (which later became Meyers Park), near the Cayadutta Creek and the mills, west of Broad Street, and along String Street and its intersecting streets.” [50]

John and Sophies’ house was along the Cayadutta Creek. John Sperber’s commute to work was less than a half of a mile. He probably walked to and from work each day. He also had the option to take the street train on Main street. John’s commute can be visualized through the use of the 1875 perspective map of Gloversville. [51]

John Sperber’s Journey to Work

Sources

Feature Photograph: The banner for the final section of the story of John Wolfgang Sperber is an amalgam of the ony three photographs we have of John Sperber. The center photograph is a cut out of Sperber family members posing in 1897. In between the cut out is are two photographs of John Sperber in the Laying Off room at the Littauer Glove Factory.

[1] Gloversville, New York, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gloversville,_New_York

[2] Ibid

[3] The Gloversville Daily Leader, Saturday, October 28, 1899, Gloversville New York, pages pages 12 – 13;

See also Menear, Peggy and Jeanette Shiel , History of Gloversville, Copied from from The Gloversville Daily Leader, of the Date of Saturday, October 28, 1899, 13 May 2008, Fulton County NYGenWeb, https://fulton.nygenweb.net/history/glovshistory.html

[4] Burns, Adam, Fonda, Johnstown & Gloversville Railroad, revised March 14, 2024, American-Rails, https://www.american-rails.com/fjg.html

[5] Fonda, Johnstown and Gloversville Railroad, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 28 December 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fonda,_Johnstown_and_Gloversville_Railroad

[6] Mohawk Valley Democrat, Sept 10, 1870 and the Gloversville Intelligencer, Sept 15, 1870, and Gloversville Intelligencer, Aug 7, 1873. Digital source: https://nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/fmcc/id/13/rec/2

[7] Fulton County Land Deeds, 25 Feb 1874 John Sperber , Grantee’s Employer G and K S R R Co. entry volume 45, page number 478

Land Assessment 25 February 1874 John & Sophie Sperber

The following is a transcript of the quit claim deed:

| This indenture made the twenty sixth day of December in the year of one thousand and eight hundred and seventy three between John W Sperber and Sophia his wife of Gloversville Fulton County New York of the first part and the Corporation known as the Gloversville and Kingsboro Street Rail Road Company of the second party Witnesseth that the said party of the first part for and in consideration of the sum of one dollar to in hand paid by the said part of the second part the receipt whereof is hereby quit claimed and by these present to grant sell revise quit claim and assign All my right title to and interests in and to the following described sheet known as Main Street in the village of Gloversville Fulton County NY for the purpose of surveying, locating, grading, constructing operating and repairing it rail road track Provided always and thus grant is made on the express condition that the said party of the second its successors heirs and assigns shall shall build and complete the said road within the time prescribed by law. Said above described property is now used as a public highway. To have and hold the said lands belonging to the said party of the second part its successor and assigns with the same and with no other or greater right interest or estate therein than the said party of the second part is authorized to take or acquire under and on virtue of the provision of the entitled “An act to authorize the formation of Rail Road Companies and the regulate the same” passed April 2nd 1870 and other provisions of law. In witness whereof the said parties of the first part have hereunderto set their hands and seals the day and year first abovbe written. John W. Sperber Sophia Sperber In presence of C J Mills, State of New York Fulton County On the eighth day of January 1874 before in the subscribed appeared John W Sperber and Sophia his wife and acknowledged that they had severally executed the written instrument and the said Sophia on a private examination apart from her husband acknowledged that she executed the written instrument freely and with out any fear or compulsion of her husband And I further certify that I have the persons who made the said acknowledgement to the individuals described in and who executed the written instruction C.J. Mills Notary Public Recorded 25th 1874 at 9 1/4 hours F.B. Wade Dept. Clerk |

[8] Omnibuses were one of the earliest forms of public transportation in American cities in the early-to-mid nineteenth century before the introduction of horse-drawn streetcars and later electric streetcars. They were horse-drawn passenger vehicles adapted from stagecoaches to provide local transit service within cities. Omnibuses were large enclosed carriages pulled by 1-3 horses, depending on their size. The largest models could hold up to 42 passengers. They typically had two long bench seats inside oriented perpendicular to the axles, allowing more passengers than a regular stagecoach.

Omnibuses ran on predetermined routes and schedules in cities, stopping to pick up and drop off passengers along the way for a set fare. This made them an early form of mass public transit. In the late 1850s, omnibuses began to be replaced by horse-drawn streetcars running on smooth rails. The streetcars offered a superior ride and lower fares.

Casey, Bob, Horse-Drawn Vehicles in the City, 13 Sep 2021, The Henry Ford https://www.thehenryford.org/explore/blog/horse-drawn-vehicles-in-the-city

Kirk, Marcia, Omnibuses and Horse Cars or What I have Learned from Assisting Researchers, New York Department of Records and Information Services, 18 May 2018, https://www.archives.nyc/blog/2018/5/18/omnibuses-and-horse-cars-or-what-i-have-learned-from-assisting-researchers

Pre-Automobile Transportation History (1830s–1890s), Gala, University of Michigan, https://www.learngala.com/cases/model-t/4

Horsebus, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 13 July 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horsebus

Schrag, Zachary M., Urban Mass Transit In The United States, Economic History Association, https://eh.net/encyclopedia/urban-mass-transit-in-the-united-states/

Parks, Madeline, History of Buses in Public Transportation, Gogo Charters, https://gogocharters.com/blog/history-of-public-bus-transportation/

Hepp, John, Omnibuses, 2012, The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/omnibuses/

[9] Thane, Anna, The pioneering years of the horse-drawn railway, 10 Oct 2020, Regency Explorer, https://regency-explorer.net/horseandtrain/

Horsecar, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 13 July 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horsecar

Middleton, William D., The Time of the Trolley, , Milwaukee: Kalmbach Publishing , 1967, Pages 13 and 424

Morris, Eric, From Horse Power to Horsepower, 24 Jan 2014, Access, No. 30 Berkeley: University of california Transportation center, https://web.archive.org/web/20140124204000/http://www.uctc.net/access/30/Access%2030%20-%2002%20-%20Horse%20Power.pdf

Cloud, Kaden and Zak Phosri, Omaha Horse Railway Bond, Omaha in the Anthropodene, https://steppingintothemap.com/anthropocene/items/show/32

List of horse-drawn railways, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 9 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_horse-drawn_railways

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britanica, Horsecar, Britanica, 18 Jun. 2017, https://www.britannica.com/technology/horsecar .

[10] Larner, Paul K, Our railroad: The History of he Fonda, Johnstown & Gloversville railroad (1867-1893), Bloomington: Authrhouse, 2009, Pages 73 – 96

Chicago Transit Authority, Public Information Department, Horses to horsepower : a pictorial review of local transportation in Chicago since 1859, Chicago: CTA Public Information Dept. 1970 Page 2 https://archive.org/details/horsestohorsepow00chic/page/2/mode/2up

Burns, Adam, Fonda, Johnstown & Gloversville Railroad, 14 Mar 2024, https://www.american-rails.com/fjg.html

Wikipedia:WikiProject Trains/ICC valuations/Fonda, Johnstown and Gloversville Railroad, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 16 April 2016, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:WikiProject_Trains/ICC_valuations/Fonda,_Johnstown_and_Gloversville_Railroad

For a pictoral comparison of different types of street railway cars, see: Chicago Transit Authority, Public Information Department, Horses to horsepower : a pictorial review of local transportation in Chicago since 1859, Chicago: CTA Public Information Dept. 1970 Page 2

https://archive.org/details/horsestohorsepow00chic/page/2/mode/2up

[11] Horses working in 19th century American street rail systems faced numerous health issues due to poor living and working conditions:

- Short lifespans: The average working lifespan of a streetcar horse was only about 2-5 years, compared to 20-30 years for a horse under good conditions. This indicates the extreme toll the work took on their health.

- Overwork and exhaustion: Horses typically worked long hours, traveling a dozen miles per day in 4-5 hour shifts. Falls due to exhaustion were common, with horses collapsing in the streets about once every 100 miles on average.

- Unsanitary living conditions: Horses were kept in cramped, poorly ventilated urban stables. The immense amount of manure they produced, up to 35 tons per day in a city like New York, attracted disease-spreading flies and created hazardous sanitation issues.

- Disease: Close quarters and constant travel facilitated the rapid spread of diseases like equine influenza. Outbreaks could quickly incapacitate large numbers of horses, paralyzing city transportation.

- Injuries: Cobblestone streets were hard on horses’ legs and hooves. Lameness and other injuries from the constant pounding were widespread. Many horses that collapsed were simply left to die in the streets.

- Cruelty and neglect: Struggling transit companies often cut corners on horse care to save money. Sick, injured and dying horses were still forced to work. Veterinary care was primitive and concern for their welfare was not a priority.

The level of care for horses associated with street rail systems in America during the 1800s appears to have been relatively poor. Horses used for pulling streetcars had a very short life expectancy, only about two years on average. This suggests they were worked very hard with little regard for their long-term health and wellbeing. Streetcar horses typically worked long hours, traveling a dozen miles per day in four to five hour shifts.

The scale of horse usage was immense – by the mid-1880s there were over 400 street railway companies in the United States using more than 100,000 horses in total. Some individual companies used thousands of horses. The West Chicago Railways Company alone had 4,000 horses. Maintaining this many animals was expensive and companies likely cut corners on their care.

As machines, horses were worked until they could no longer perform and then were replaced. Caring for their health beyond keeping them functioning was not a major consideration for streetcar companies focused on profits and moving passengers.

Lyle, Horse-Drawn Street Railways: Technology That Changed Chicago, Dec 2 2013, Chicago Public Library, https://www.chipublib.org/blogs/post/technology-that-changed-chicago-horse-drawn-street-railways/

Horsecar, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 17 July 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horsecar

Heyday of the Horse, American Museum of Natural History, https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/horse/how-we-shaped-horses-how-horses-shaped-us/work/heyday-of-the-horse

Kohlstedt, Kurt, The Big Crapple: NYC Transit Pollution from Horse Manure to Horseless Carriages, 99% Invisible, https://99percentinvisible.org/article/cities-paved-dung-urban-design-great-horse-manure-crisis-1894/

Carlsson, Chris, The Heyday of Horsecars, FoundSF, https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=The_Heyday_of_Horsecars

Freeberg, Ernest, The Horse Flu Epidemic that Brought 19th-century America to a Stop, Dec 4 2020, Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-horse-flu-epidemic-brought-19th-century-america-stop-180976453/

Nikoforuk, Andrew, The Big Shift Last Time: From Horse Dung to Car Smog, 6 Mar 2013, The Tyee, https://thetyee.ca/News/2013/03/06/Horse-Dung-Big-Shift/

[12] Larner, Paul K, Our railroad: The History of the Fonda, Johnstown & Gloversville railroad (1867-1893), Bloomington: Authorhouse, 2009, Pages 95

[13] Larner, Paul K, Our railroad, Page 96

[14] The Early Years, International Brotherhood of Teamsters, https://teamster.org/about/teamster-history/the-early-years/

Kavalchik, Kara, Where Did the Name “Teamsters” Come From?, 2 Sep 2012, Mental Floss, https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/12411/where-did-name-teamsters-come

[15] 1870 U.S. Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Johnstown, Page 209 Lines 32-37

[16] Gazetteer and business directory of Montgomery and Fulton Counties, N.Y. for 1869-70, Page 241

Gloversville and Johnstown Directory including Kingsboro 1875-76, page 75

[17] Barbara McMartin, The Glove Cities: How A People and Their Craft Built Two Cities, NY: Lake View Press, 1999, Page 33

[18] Barbara McMartin, The Glove Cities, Page 92

[19] Barbara McMartin, The Glove Cities, Page 93

[20] Ida M Griffis, Birth date: 30 May 1876; Claim Date 10 Dec 1946; SSN 112103082, U.S> Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936 – 2007

[21] Anna Sperber, Birth 1857 Fulton. County, Death 15 Nov 1876, Burial: Prospect Hill cemetery, Gloversville, Fulton County, Memorial ID: 158848306, “Anna was the daughter of John W. and Sophia Fliegel Sperber. She worked as a glove maker. Anna was 19 years old.”

Anna Sperber, Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/158848306/anna-sperber

[22] Rose and Charles Knopf are found in the 1880 census:

[23] Chaser, The Goldsmiths’ Centre, https://www.goldsmiths-centre.org/career-profiles/profiles-chaser/

Charles Knopf is found in the 1879 Directory for Brooklyn. He is listed as an engraver, living at 378 Bedford Avenue. Charles Knopf was living with his father Daniel Knopf. Daniel was a cabinet maker. In the directory his occupation was listed as a sawyer. A “Sawyer is an occupational term referring to someone who saws wood, particularly using a pitsaw either in a saw pit or with the log on trestles above ground or operates a sawmill. One such job is the occupation of someone who cuts lumber to length for the consumer market … .”

Sawyer, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 13 June 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sawyer_(occupation)

1880 Occupational Codes, Code 237, Sawyer, Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, https://usa.ipums.org/usa/volii/occ1880.shtml

[24] Barbara McMartin, The Glove Cities, Page 45 and 46

[25] The factory system that emerged during the Industrial Revolution differed significantly from the earlier cottage industry in terms of production methods. Here are the key differences:

Centralization of Production:

- Cottage industry: Production was decentralized, with goods being produced in homes or small workshops scattered across towns and villages.

- Factory system: Production was centralized in large factories, usually located in cities near power sources (water, steam) and transportation routes. Factories brought together workers, machinery, and raw materials under one roof.

Mechanization and Technology

- Cottage industry: Relied on skilled artisans using hand tools or simple machinery to craft goods. The goods were often unique since they were individually made.

- Factory system: Utilized powered machinery (initially water and steam, later electricity) to mechanize and speed up production. Technological innovations like the spinning jenny, water frame, and power loom revolutionized industries like textiles.

Scale of Production

- Cottage industry: Goods were produced on a small scale due to the limitations of decentralized production.

- Factory system: Allowed for mass production of goods on a much larger scale, which helped meet growing demand. Factories achieved economies of scale, lowering product costs.

Labor and Skill

- Cottage industry: Depended on the skills of individual craftspeople who often completed products from start to finish.

- Factory system: Utilized division of labor, with most workers being either low-skilled machine operators or unskilled laborers. Work was broken down into simple, repetitive tasks.

Standardization

- Cottage industry: Products were often unique and varied since they were handmade by individuals.2

- Factory system: Products and their components were made to standard specifications using precision machinery, allowing for uniformity and interchangeability of parts.

Beck, Elias, Cottage Industry vs. Factory System during the Industrial Revolution, March 25, 2022, History Crunch, https://www.historycrunch.com/cottage-industry-vs-factory-system.html#/

Factory System, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 15 July 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Factory_system

[26] Barbara McMartin, The Glove Cities, Page 88

See also Hunt, Arthur, Twelfth Census of the United States, Census Bulletin No. 175, Washington D.C. May 24, 1902, Pages 5 & 6 https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1900/bulletins/manufacturing/175-manufactures-gloves-mittens-leather.pdf

[27] Child labor was widespread in the late nineteenth century. About a fifth of all U.S. workers were under age 16 by 1900. Childrenworked long hours, often twelve or more hour days, in dangerous factories and mines. Suffragettes and concerned mothers began protesting child labor in the mid-1800s, leading to some modest reform legislation starting in the 1870s.

Many immigrant families in cities like New York lived and worked in overcrowded, unsanitary tenement houses. Entire families would live in small, poorly ventilated apartments, spending long days rolling cigars or assembling garments and machinery at home, a practice known as “piecework.” Investigators like journalist Jacob Riis launched campaigns to expose and reform the exploitative tenement housing conditions.

The 1880s saw increasing labor unrest and battles between workers and management over issues like safety, wages, hours, and the right to unionize. Key events included the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, the Haymarket Affair of 1886, and numerous coal miner strikes. Unions like the Knights of Labor grew rapidly in the 1880s to advocate for workers’ rights.

Michael Schuman, Michael, “History of child labor in the United States—part 1: little children working,” Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, January 2017, https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2017.1

Hufford, Deborah, Child Labor in the 1800s, 24 Mar 2020, Notes from The Frontier, https://www.notesfromthefrontier.com/post/child-labor-in-the-1800s

Tenements and Toil, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/italian/tenements-and-toil/

America at Work, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/america-at-work-and-leisure-1894-to-1915/articles-and-essays/america-at-work/

Labor Wars in the U.S., American Experience, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/theminewars-labor-wars-us/

Whaples, Robert. “Child Labor in the United States”. EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. October 7, 2005. URL https://eh.net/encyclopedia/child-labor-in-the-united-states/

Brian Gratton and Jon Moen, “Immigration, Culture, and Child Labor in the United States, 1880-1920.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 34, no. 3 (2004): 355-91.

Moehling, Carolyn. “State Child Labor Laws and the Decline of Child Labor.” Explorations in Economic History 36 (1998): 72-106.

Parsons, Donald O. and Claudia Goldin. “Parental Altruism and Self-Interest: Child Labor among Late Nineteenth-Century American Families.” Economic Inquiry 27, no. 4 (1989): 637-59.

[28] Barbara McMartin, The Glove Cities, Page 93

[29] Barbara McMartin, The Glove Cities, Page 93

[30] The 1880 U.S. Census is well-known for being the first census to report a number of new facts about individuals being enumerated. It was the first time in a Federal census that the relationship of each individual to the head of the household. It was also the first to specify the place of birth not only of the individual being enumerated, but also the place of birth of his or her parents. Street name and house number were also documented. Unfortunately, for Gloversville, the census enumerator did not document this information. In addition, the census provided information on birth month if an individual was born in the preceding year. In column 14, the census documented the number of months someone was not employed in the prior year. Column 15 asked a very unique question. This column asks if the individual was sick or temporarily disabled on the day that the enumerator arrived. If so, the enumerator was to specify the illness or reason for the disability. Columns 16 through 20 canvas respondents on health related issues. Columns 21 through 23 asked questions related to education.

7 Important Clues From the 1880 U.S. Census, Legacy Tree Genealogists, https://www.legacytree.com/blog/7-important-clues-from-the-1880-u-s-census

[31] Hunt, Arthur, Twelfth Census of the United States, Census Bulletin No. 175, Washington D.C. May 24, 1902, Pages 5 & 6 https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1900/bulletins/manufacturing/175-manufactures-gloves-mittens-leather.pdf

Barbara McMartin, The Glove Cities, Page 93

[32] Reese, William, The Origins of the American High school, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995

[33] As indicated in the story, Frederick was still living with his parents in June 1880. The following census tabulation verifies that Ella Abcock was living with her parents in June 1880.

[34] We do not have documentation on the exact date of marriage between Frederick Sperber and Ella Aucock. The 1900 census asks how long someone was married (column 10). The census enumerator indicated that Frederick and Ella Sperber were married 20 years. Column 7 indicates the month and year of birth. Their first child, Rosa, was born in December 1880.

Frederick and Ella Sperber’s Household in 1900

[35] New York Land Records Fulton County, Volume 59, Page 548, 28 Jun 1882, Grantor Andrew D Simmons and Grantee Sophia Sperber

[36] Amy Feiereisel, North Country at Work: Tanning and Glove-Making in Johnstown and Gloversville, North Country Public Radio, Nov 28, 2018, https://www.northcountrypublicradio.org/news/story/37491/20181128/north-country-at-work-tanning-and-glove-making-in-johnstown-and-gloversville

[37] Laura, Inside the Watson Gloves Factory – Learn How Our Gloves Are Made, Jan 12 2021, Watson Gloves, https://www.watsongloves.com/inside-the-watson-gloves-factory-learn-how-our-gloves-are-made/

[38] Hunt, Arthur, Twelfth Census of the United States, Census Bulletin No. 175, Washington D.C. May 24, 1902, Manufactures: Gloves and Mittens – Leather, Selected statistics derived from Table 11 on Page 17 https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1900/bulletins/manufacturing/175-manufactures-gloves-mittens-leather.pdf

[39] Amy Feiereisel, North Country at Work: tanning and glovemaking in Johnstown and Gloversville, North Country Public Radio, Nov 28, 2018, https://www.northcountrypublicradio.org/news/story/37491/20181128/north-country-at-work-tanning-and-glove-making-in-johnstown-and-gloversville

[40] Greene, Nelson, Chapter 103: Mohawk Manufacturing Statistics, History of the Mohawk Valley: Gateway to the West 1614 – 1925, Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1925, Pages 478-482, Volume 3: https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/qOApAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj93vfQneOGAxWp8MkDHQfDDNEQ7_IDegQIDxAF

Barbara McMartin and W. Alec Reid, The Glove Cities, Caroga, NY: Lake View Press, 1999,, Pages 56 -57

Gloversville historian – stump city , glove industry, littauer, more http://www.cityofgloversville.com/residents/city-historian/

[41] “Littauer, Lucius Nathan .” Encyclopaedia Judaica. Encyclopedia.com https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/littauer-lucius-nathan

Greene, Nelson, Chapter 103: Mohawk Manufacturing Statistics, History of the Mohawk Valley: Gateway to the West 1614 – 1925, Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1925, Pages 478-482, Volume 3: https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/qOApAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj93vfQneOGAxWp8MkDHQfDDNEQ7_IDegQIDxAF

Lucius Littauer, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 16 July 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucius_Littauer

[42] Boxerman, Burton Alan. Lucius Nathan Littauer, American Jewish Historical Quarterly, vol. 66, no. 4, 1977, pp. 501. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23880341 .

[43] Boxerman, Burton Alan. Lucius Nathan Littauer, Page 507

[44] Lucius Littauer, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 16 July 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucius_Littauer

Boxerman, Burton Alan. Lucius Nathan Littauer, American Jewish Historical Quarterly, vol. 66, no. 4, 1977, pp. 498–512. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23880341 .

“Littauer, Lucius Nathan .” Encyclopaedia Judaica. Encyclopedia.com https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/littauer-lucius-nathan

Blast from the Past: T.R. and L.L. BFFs https://leaderherald.com/gloversville-local-news-johnstown-local-news/community-news/2022/01/blast-from-the-past-t-r-and-l-l-bffs/

[45] Cudmore, Bob, Focus on History: Littauer a Gloversville luminary, 17 Aug 2018, The Daily Gazette, https://www.dailygazette.com/opinion/focus-on-history-littauer-a-gloversville-luminary/article_d873d7ef-4087-5649-b4a6-2df126474006.html

Lucius Littauer, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 16 July 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucius_Littauer

“Littauer, Lucius Nathan .” Encyclopaedia Judaica. Encyclopedia.com https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/littauer-lucius-nathan

[46] The Gloversville and Johnstown Directory, New Haven: Price & Andrew, Printed by Henry Bradley, 131 Union Street, 1873, Page 65

[47] Post Card of the The Littauer Glove Factory Gloversville, New York, 1916, Old Post Cards, https://www.oldpostcards.com/uspostcards/new-york/gloversville-ny_yy_10387-the-littauer-glove-factory.html

[48] Boxerman, Burton Alan. Lucius Nathan Littauer, American Jewish Historical Quarterly, vol. 66, no. 4, 1977, pp. 508. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23880341 .

[49] The Sanborn Map Company was a prominent American publisher of detailed fire insurance maps from 1867 to the late 20th century. Founded in 1867 by Daniel Alfred Sanborn, the company created richly detailed maps of approximately 12,000 cities and towns across the United States, Canada, and Mexico.Sanborn maps were originally designed to assist fire insurance companies in assessing the risk associated with insuring a particular property.

The maps provided detailed information about the size, shape, construction materials and function of buildings in urban areas. They also included details like street names and widths, property boundaries, building use, and the location of water mains, fire alarms and fire hydrants.

The Sanborn Company sent out legions, or to use the collective group term of surveyors, ‘chains’, of surveyors to map building footprints and collect urban data. At its peak in the 1920s, the company employed about 700 people, including 300 field surveyors and 400 cartographers, printers and managers. Sanborn held a virtual monopoly over fire insurance maps for much of the 20th century after acquiring its last major competitor in 1916.

While originally created for insurance purposes, Sanborn maps have become invaluable historic resources. They allow researchers to trace urban development and changes over time, providing detail about the built environment of American cities from the late 1800s through the mid-1900s.

The Library of Congress holds the largest collection of Sanborn maps, which are widely used by historians, architects, genealogists and others.

Sanborn Maps, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 1 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanborn_maps

Sanborn Maps, About This Collection, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/sanborn-maps/about-this-collection/

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Gloversville, Fulton County, New York., Sanborn Map Company, Published Oct 1902, Digital Id http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3804gm.g3804gm_g059511902

Coons, Alana, Let’s Talk about Sanborn Maps, University Heights Historical Society, https://www.uhhs-uhcdc.org/blog/lets-talk-sanborn-maps

[50] Barbara McMartin, The Glove Cities, Page 92

[51] Harris, Richard, The Journey to Work: A Historical Methodology , Historical Methods A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History, Vol 30 No 2, March 1997, Pages 97 – 109, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249037136_The_Journey_to_Work_A_Historical_Methodology