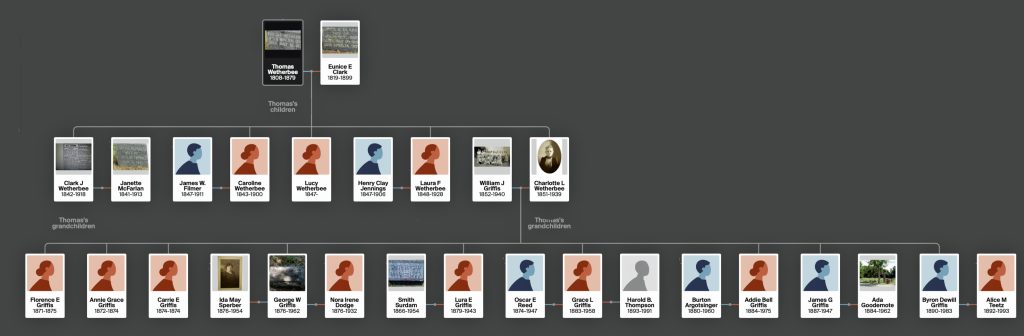

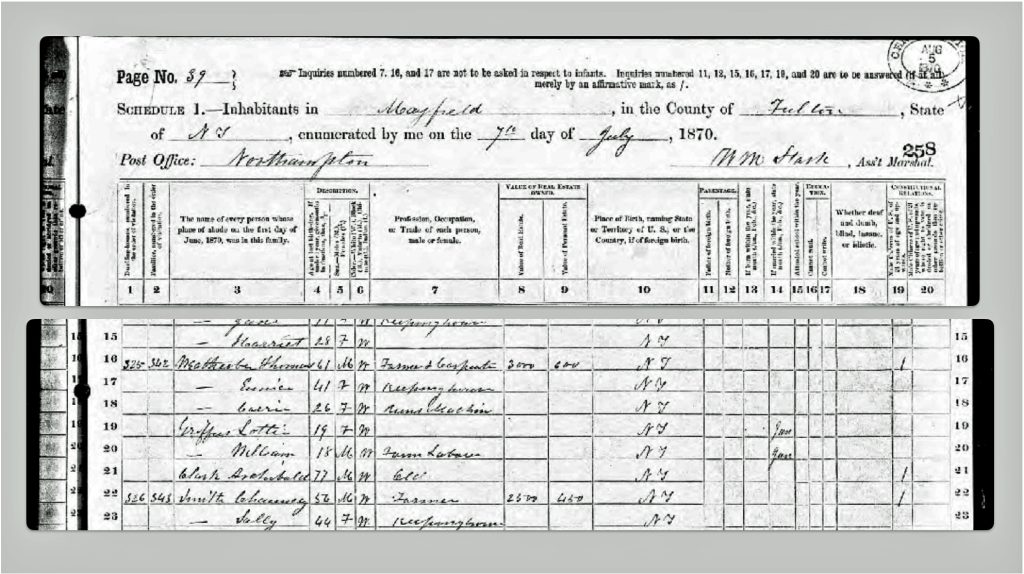

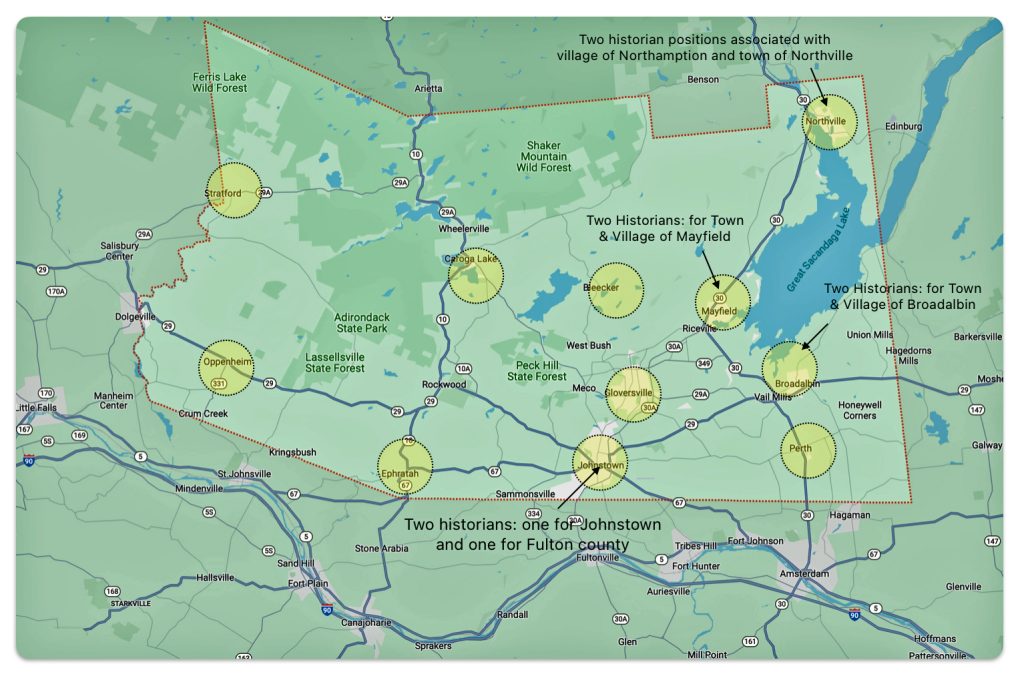

William J. Griffis and Charlotte Wetherbee married when they were teenagers in January 1870. William was one year younger than his bride. He was eighteen years old. The young couple moved in with Charlotte’s mother and father, Thomas Wetherbee and Eunice (Clark) Wetherbee. When they got married, Charlotte’s father was 61 years old. He was twenty years older than his wife Eunice, who was 41. [1] Thomas Wetherbee was a farmer and carpenter in the Mayfield, New York area. He built his farm house and a local school house in Mayfield, New York. [2]

William J. Griffis was the son of William Gates Griffis. William G. Griffis was the son of Daniel Griffis. Daniel Griffis is my great great great grandfather. Another son of Daniel’s was Joel Griffis. Joel is my great great grandfather and brother of William G. Griffis. William J. Griffis is my 1st cousin 4x removed.

The young couple quickly started a family. They had three daughters within four years after their marriage. It appeared life was going well for the extended family on the farm and particularly the young couple, working on the farm and raising a young, growing family.

Within four years, the farm household contained three generations of family members. The young couple lived with Charlotte’s parents as well as one of her sisters, Carrie Wetherbee (age 26), and her maternal grandfather, Archibald Clark, who was 77. Young William worked with his father-in-law on the farm.

Table One: William and Charlotte’s Daughters in the first Four Years of Their Marriage

| Children | Birth Date |

|---|---|

| Florence Eliza Griffis | May 1, 1871 |

| Annie Grace Griffis | September 1, 1872 |

| Carrie Esther Griffis | March 4, 1874 |

A Dark Time: The Winter of 1874 through the Spring of 1875

Beginning in December of 1874 through May the following year, the world of this young Griffis family, and the extended Wetherbee family living on the farm, was radically altered.

As reflected in table two, their two youngest daughters, Annie and Carrie, died within two weeks of each other in December, before and after the Christmas holiday. Annie was two and a half years old and Carrie was nine months old. Then, five months later, toward the end of May in 1875, their oldest and only surviving daughter, Florence, passed away 23 days after her fourth birthday. In the matter of five months, their young family was entirely gone. [3]

Table Two: The Winter of 1874 and the Spring of 1975

| Children | Birth Date | Death | Age |

|---|---|---|---|

| Florence Eliza Griffis | May 1, 1871 | May 24, 1875 | 4 Years |

| Annie Grace Griffis | September 1, 1872 | December 17, 1874 | 2 Years & 2.5 Months |

| Carrie Esther Griffis | March 4, 1874 | December 30, 1874 | 9 Months |

The death of a child is devastating regardless of time period. It is often referred to as the worst experience a parent can endure. A child’s death can cause a profound family crisis. It shatters core beliefs and assumptions about the world and the expectations about how life should unfold. Losing multiple young children is beyond comprehension or feeling. It is pan and loss that undoubtably makes the mind and soul numb. To loose all of their young children must have been devastating for the young couple as well as the extended family.

The cause of the untimely death of the three young sisters within a six month period was attributed to diphtheria. [4] Their deaths from diphtheria were not isolated cases. A serious epidemic of diphtheria resulted in many deaths in the Mayfield – Broadalbin area in the 1870s. [5]

The Diphtheria Epidemic of the 1870’s

This epidemic reflected a larger trend in the nation. Starting around 1870, the number of diphtheria deaths nationwide began to increase. For example, “(f)or the nine years from 1869 to 1878, Michigan held its own, averaging 229 deaths a year due to diphtheria. In 1878 that number spiked to 887.” [6]

“In 1875, the 243-person death toll from diphtheria comprised 8.2% of all reported deaths (in Cleveland, Ohio). As was typical of the disease, children comprised most of the mortalities.” [7]

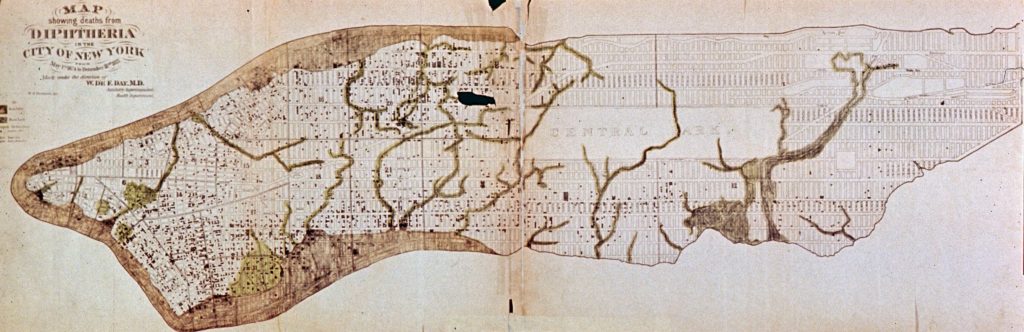

A map shows the deaths from diphtheria in New York City from May 1, 1874 to December 31, 1875, suggesting diphtheria was prevalent in the city in the mid-1870s [8]

Map Showing Deaths from Diphtheria in the City of New York December 31, 1875

In Geneva, New York, which was about 170 miles west of Mayfield, a diphtheria epidemic occurred from September 1878 to March 1879, with over 400 residents falling ill and at least 75 people, mostly children, dying. This provides a glimpse of the impact of diphtheria in one upstate NY town in the late 1870s. [9]

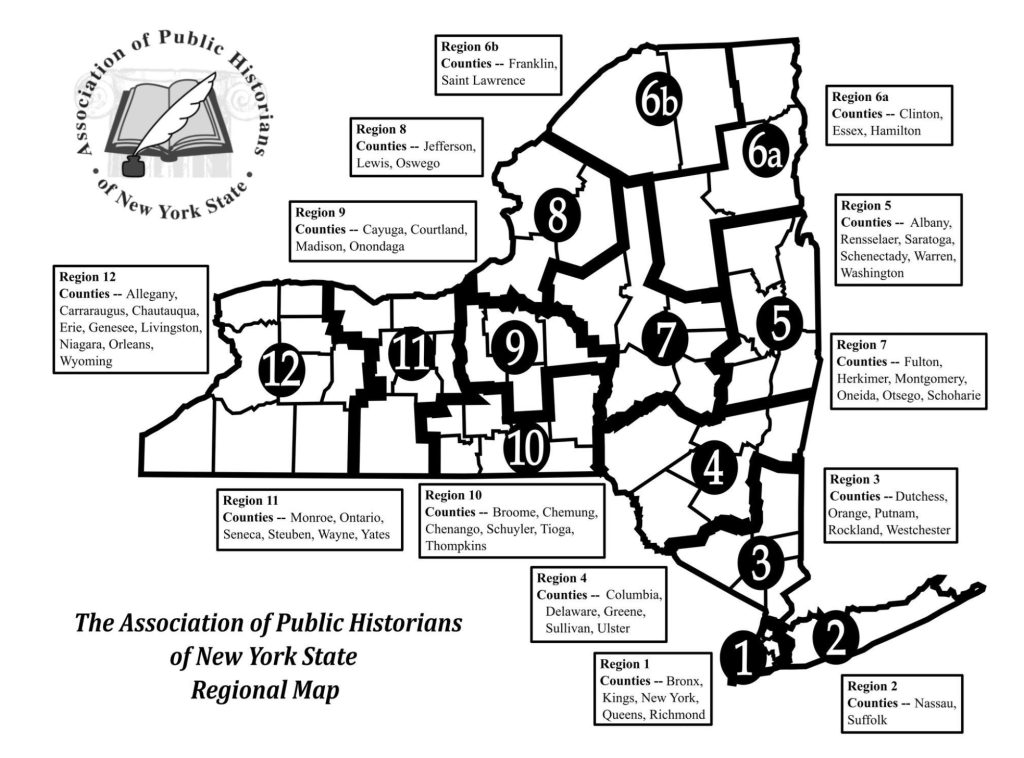

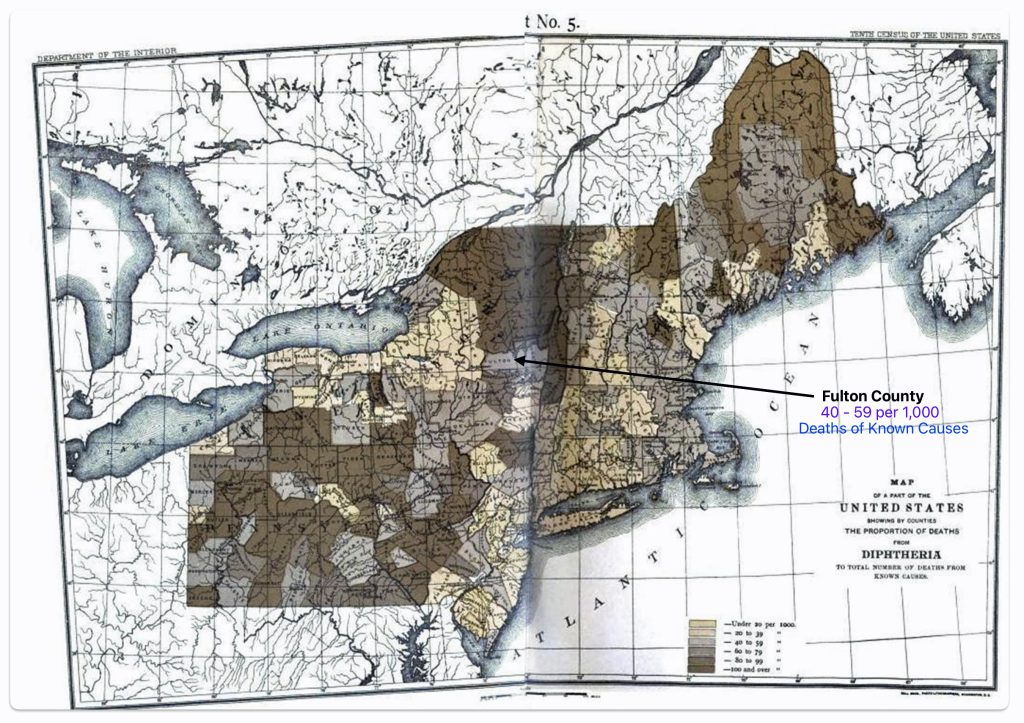

As reflected in a special section of the 1880 census, diphtheria was notably present in the northern part of New York state. Forty to fifty deaths per 1,000 deaths were attributable to Diphtheria in Fulton County, where the Griffis family lived. Just north and east of Fulton county, the rate was over 100 diphtheria deaths per 1,000 deaths. [10]

The Proportion of Deaths from Diphtheria to Total of Deaths from Known Causes by County 1880

Diphtheria: the Strangling Angel of Children

Called the “strangling angel of children,” [12] diphtheria was and is a serious bacterial infection caused by corynebacterium diphtheriae. It usually affects the mucous membranes of the nose and throat. It typically causes a sore throat, fever, a barking cough like croup, swollen glands and weakness. The hallmark sign of the disease is the development of a sheet of thick, gray material covering the back of the throat which can block the airway, causing the patient to struggle for breath. Often death came only a few days or even just hours after the onset of symptoms.

“Diphtheria (Corynebacterium diphtheriae), an acute bacterial infection spread by personal contact, was the most feared of all childhood diseases. Diphtheria may be documented back to ancient Egypt and Greece, but severe recurring outbreaks begin only after 1700. One of every ten children infected died from this disease. Symptoms ranged from severe sore throat to suffocation due to a ‘false membrane’ covering the larynx. The disease primarily affected children under the age of 5. Until treatment became widely available in the 1920s, the public viewed this disease as a death sentence.” [13]

Diphtheria was known by several different names before it was officially named in 1826. In England in the early 1800s, it was known as “Boulogne sore throat,” as the illness had spread from France. [14] In 1826, French physician Pierre Bretonneau gave the disease its official name “diphthérite” (from Greek diphthera meaning ‘leather’), describing the appearance of the pseudomembrane that forms in the throat. He was the first to accurately describe the disease. [15]

Diphtheria existed and caused epidemics in the 1700s and early 1800s. Before its official discovery, diphtheria was prevalent in eighteenth and nineteenth century society. Between 1735 and 1740, a diphtheria epidemic in the New England colonies was thought to be responsible for the death of 80 percent of children under 10 years of age in select towns. [16]

The mortality rate from diphtheria in the 1800s was very high, especially among children. Diphtheria was the most feared of all childhood diseases in the 1800s. One of every ten children infected died from this disease. [17] Diphtheria case fatality rates ranged from about 20% for those under age five and over age 40, to 5-10% for those aged 5-40 years. [18]

Diphtheria: The Strangling of Children [19]

Life Continues in the Griffis Family

In an era before grief counseling and support groups, parents coped for the loss of children by relying primarily on their faith, their families, and the cultural scripts for mourning. While the outward rituals could not erase their sorrow, they provided a socially sanctioned way for parents to honor their children’s memory and slowly heal from heartbreaking losses.

We have no records to document how William and Charlotte handled the magnitude of their loss. It undoubtably had a profound impact on their lives.

Despite their loss of three daughters, as reflected in table three, they had eventually had their fourth child, George Griffis, in the fall of 1876, about 16 months after the death of Carrie Esther Griffis. After George, their first son, they had three additional daughters and two other sons.

Table Three: William & Charlotte’s Remaining Children

| Name | Birth Date | Years Between Each Birth | Death Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| George William Griffis | Oct 8, 1876 | 16 mos* | May 13, 1962 |

| Lura Elizabeth Griffis | May 13, 1879 | 29 mos | Dec 11, 1943 |

| Grace Lavina Griffis | Jul 3, 1883 | 36 mos | Jan 31, 1958 |

| Addie Bell Griffis | Nov 28, 1884 | 16 mos | Apr 2, 1975 |

| James Garfield Griffis | Apr 2, 1887 | 29 mos | Nov 28, 1947 |

| Byron Dewill Griffis | Sep 7, 1890 | 41 mos | Jun 4, 1983 |

Childhood Disease in the late 1800s

Losing multiple young children sadly was a common experience for parents in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Child mortality rates were substantially higher than they are in the 21st century. Various factors contributed to high child mortality rates, including infectious diseases, poor sanitation, limited medical knowledge, and inadequate healthcare. In the late nineteenth century, epidemics of cholera, typhus, yellow fever, smallpox, whooping cough and diphtheria claimed many lives, and endemic infectious diseases took a significant toll on infants and young children. [20]

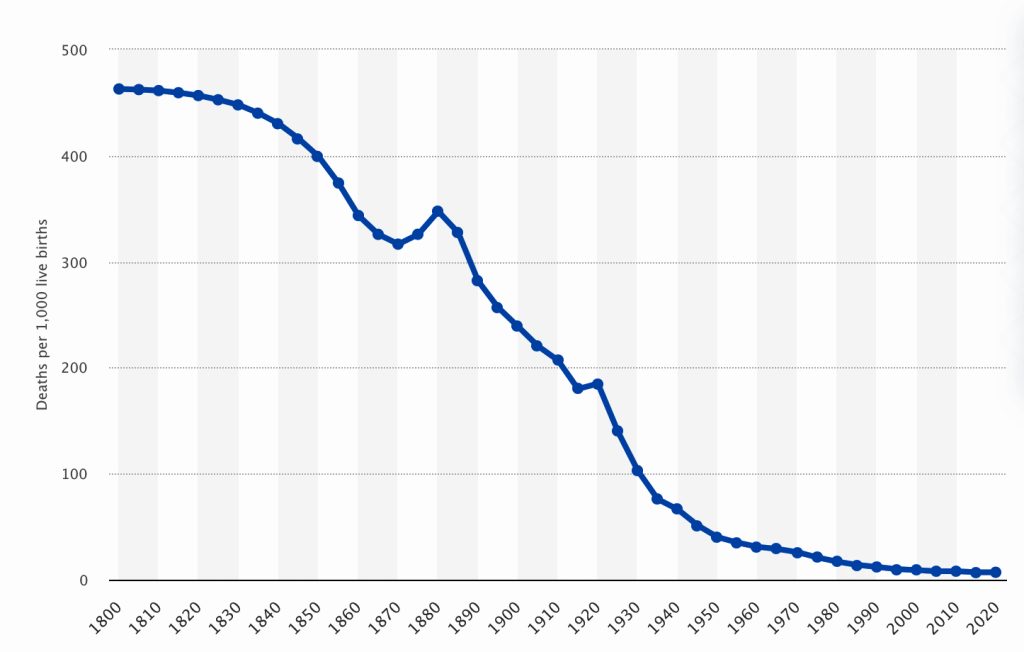

As reflected in the chart below, the child mortality rate in the United States, for children under the age of five, was 316.5 deaths per thousand births in 1870. This means that for every thousand babies born in 1870, over 32 percent did not make it to their fifth birthday. The child mortality rate in 1875 was 325.81. It was not util 1880 that the overall child mortality rate started to drop.

Over the course of the next 150 years, “this number has dropped drastically, and the rate has dropped to its lowest point ever in 2020 where it is just seven deaths per thousand births. Although the child mortality rate has decreased greatly over this 220 year period, there were two occasions where it increased; in the 1870s, as a result of the fourth cholera pandemic, smallpox outbreaks, and yellow fever, and in the late 1910s, due to the Spanish Flu pandemic.” [21]

Child Mortality Rate (Under Five Years Old) in the United States, from 1800 to 2020

In the late 1800s, the most common infectious diseases causing child mortality were primarily due to a range of bacterial and viral pathogens. During the 1870s, child mortality in New York state, as in much of the United States, was significantly influenced by a range of infectious diseases. The most common diseases causing child mortality during this period included: [22]

- Tuberculosis: Often referred to as consumption, tuberculosis was a leading cause of death in the 19th century, affecting individuals of all ages, including children. It was particularly deadly in urban areas like New York City, where crowded living conditions facilitated the spread of the disease.

- Diarrheal Diseases: Diarrheal diseases, including cholera infantum and dysentery, were prevalent causes of death among infants and young children. Poor sanitation and contaminated water supplies contributed to outbreaks of these diseases, which could lead to severe dehydration and death.

- Diphtheria: Known for causing severe respiratory issues, diphtheria was a significant cause of child mortality in this time perod and was a major cause of child mortality in the 1800s in general. The disease, as discussed, is characterized by the formation of a thick coating in the throat and airways, leading to breathing difficulties, heart failure, and paralysis.

- Scarlet Fever: Caused by the Streptococcus bacteria, scarlet fever was a common childhood illness that could lead to serious complications and death. Symptoms included a high fever, sore throat, and a distinctive red rash.

- Measles: Highly contagious, measles led to numerous deaths among children, particularly in densely populated areas. Complications from measles could include pneumonia, encephalitis, and blindness.

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis): Whooping cough was another highly contagious bacterial infection that caused severe coughing fits and was particularly deadly for infants and young children.

The Burial of the Three Daughters

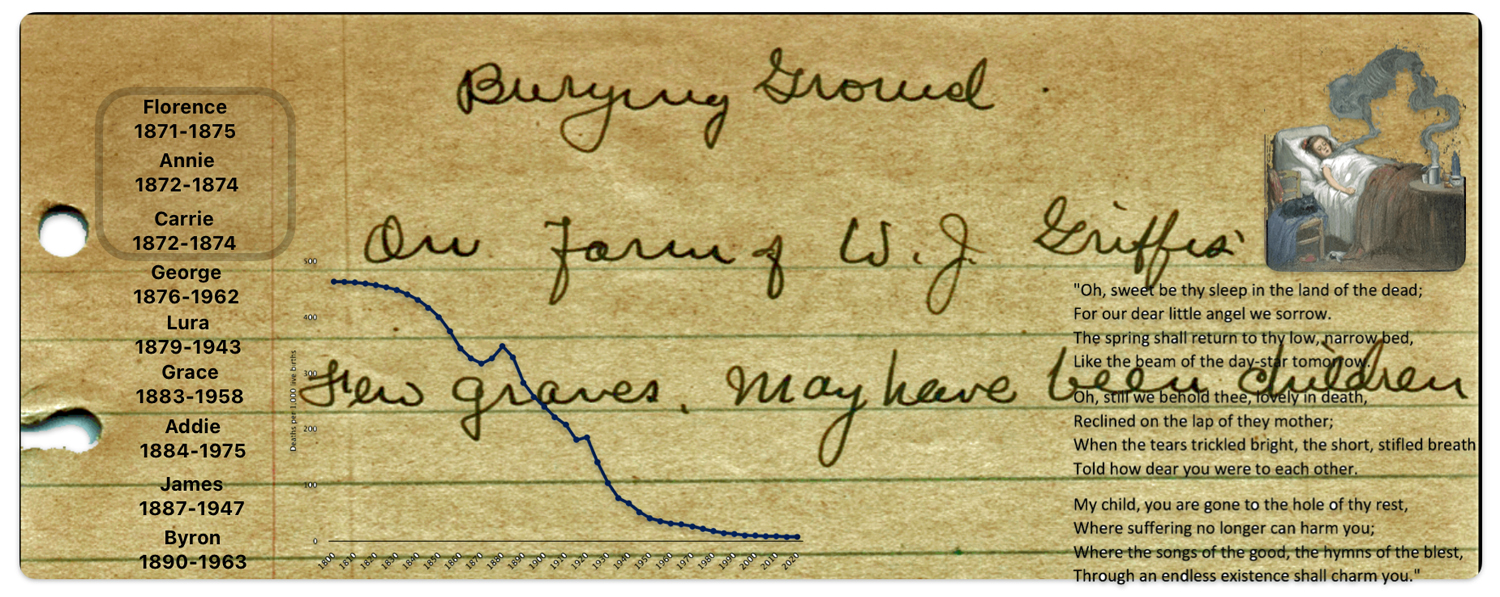

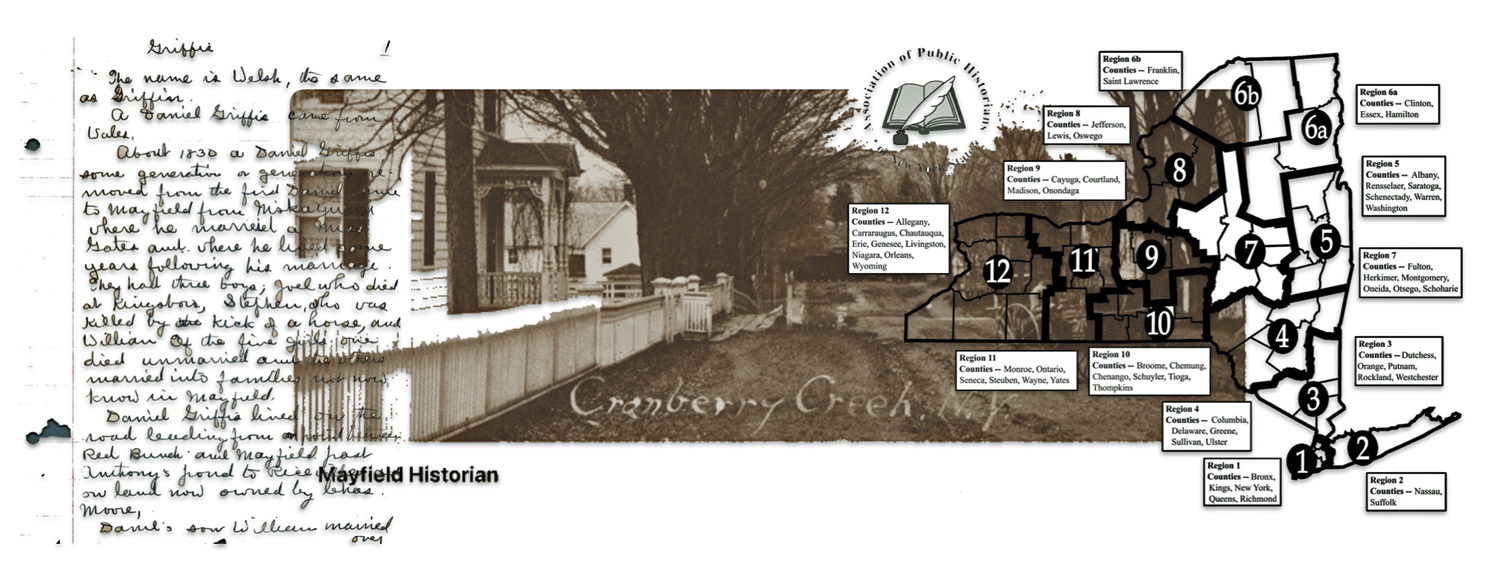

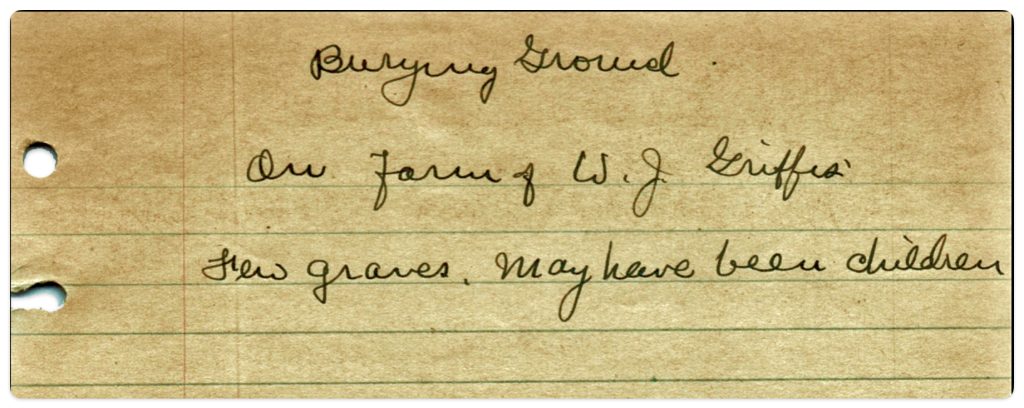

William and Charlotte buried their three daughters in graves on the farm. It appears that they were unmarked or the headstones were not present in the mid 1930s. Their burial was documented in the notes of Mayfield Historian Edward Ruliffson in 1935 on “Missing Burying Grounds”. In a terse one sentence statement it is noted that there were a few graves, possibly children, that were identified on the farm of W. J. Griffis. [23]

“Burying Ground on farm of W. J. Griffis Few graves, May have been children.”

Ruliffson’s Notes on Missing Burying Grounds in Mayfield

It was not uncommon for families in rural areas in the 1800s to bury their dead in family plots on farmland. In many rural areas, it was common for families to bury their deceased on their own land, often on a hilltop or another chosen spot within the family property. These family burial grounds served as the final resting places for multiple generations.

The transition from burying the dead on family plots to using cemeteries in America was a gradual process that evolved over several centuries, with significant changes occurring in the nineteenth century. Initially, burials in America followed the practices of burying the dead in small, family-owned plots or in churchyards. The concept of cemeteries as we know them today began to take shape in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. [24]

The 1700s saw the beginning of cemeteries and graveyards, with Americans organizing burial grounds and marking the burial places of their dead with headstone and monuments. However, it was not until the late nineteenth century that the ‘modern cemetery’ was born. These were public burial spaces designed to be inviting so that families could come and spend time visiting their loved ones. This shift was partly due to practical reasons, such as the need for more space and concerns about sanitation in growing urban areas, and partly due to changing attitudes towards death and mourning. [25]

It would not have been surprising to find family burial plots on the Griffis farm. However, there were only three graves on the Griffis family land. The family owned the farmland for at least three generations. As reflected in table four, aside from three unmarked graves, no other family members who lived on the property were buried on near the three graves. Archibald Clark, Eunice’s father, was buried, along with his wife and other Clark family members at the West Galway Cemetery. William J. Griffis was buried next to his wide Charlotte on the Wetherbee cemetery plot in the Broadalbin – Mayfield Rural Cemetery.

Table Four: Burial Locations of Immediate Members of Griffis and Wetherbee Family [26]

| Family Member | Date of Death | Burial Location |

|---|---|---|

| Thomas Wetherbee | 24 Mar 1879 | Broadalbin – Mayfield Rural Cemetery |

| Eunice Wetherbee | 14 Apr 1899 | Broadalbin – Mayfield Rural Cemetery |

| Archibald Clark | 24 May 1881 | West Galway Cemetery |

| William J. Griffis | 28 May 1940 | Broadalbin – Mayfield Rural Cemetery |

| Charlotte Griffis | 19 Feb 1939 | Broadalbin – Mayfield Rural Cemetery |

Overall, the burial practices for children who died from diphtheria in the 1870s were shaped by the urgent need to control the spread of the disease, the economic resources of the affected families, and the prevailing cultural and religious practices related to death and mourning.

Burial practices for children who died from diphtheria in the 1870s varied depending on local customs, the severity of the epidemic in the area, and the resources of the community and family affected. Many of the traditional customs for burial and mourning were not practiced if family members died from diphtheria due to the possibility of contagion.

Various sources suggest a number of general practices and challenges associated with burials of loved ones whose deaths were attributed to diphtheria :

- Immediate and Isolated Burials: Due to the infectious nature of diphtheria and the rapid deterioration of the bodies, burials often occurred quickly after death. There was a concern about preventing the spread of the disease, which sometimes led to more isolated burial sites or sections within cemeteries designated for victims of infectious diseases. [27]

- Use of Disinfectants and Precautions: In some cases, communities took precautions to prevent the spread of the disease during the burial process. This included the use of disinfectants in the sick-room and around the deceased’s belongings. There was an awareness of the need to handle the bodies and belongings of the deceased with care to avoid further transmission of the disease. [28]

- Simple and Private Ceremonies: The fear of spreading the disease often led to simpler and more private funeral ceremonies, with limited attendance. The focus was on quick interment to reduce the risk of exposure to the living . [29]

- Impact on Family and Community Burial Practices: The high mortality rate among children due to diphtheria epidemics had a profound impact on family and community burial practices. In some cases, multiple children from the same family or community were buried in close succession, which could lead to the establishment of specific areas within cemeteries for diphtheria victims or even the creation of new burial grounds. [30]

- Economic and Emotional Strain: The cost of burials and the emotional toll of losing children to diphtheria affected families and communities. The economic strain could influence the type of burial and memorialization possible for the deceased. [31]

Treatment of Diphtheria in the Late 1900s into the 1900s

The discovery and development of a diphtheria antitoxin unfortunately occurred fifteen years after the death of the three Griffis sisters.

The treatment of diphtheria in the 19th century transitioned from rudimentary and often desperate measures to more scientific and effective approaches. The Griffis daughters succumbed to diphtheria before the advent of antitoxin and vaccines. The remedies used for diphtheria were quite varied and often based on limited medical knowledge and personal experience rather than scientific evidence. Some of the treatments and remedies included the use of disinfectants, gargling with Kerosene Oil, Calomel treatments and opium laced herbal formulas. [32]

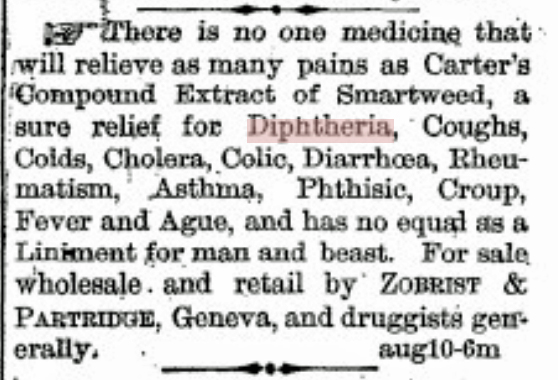

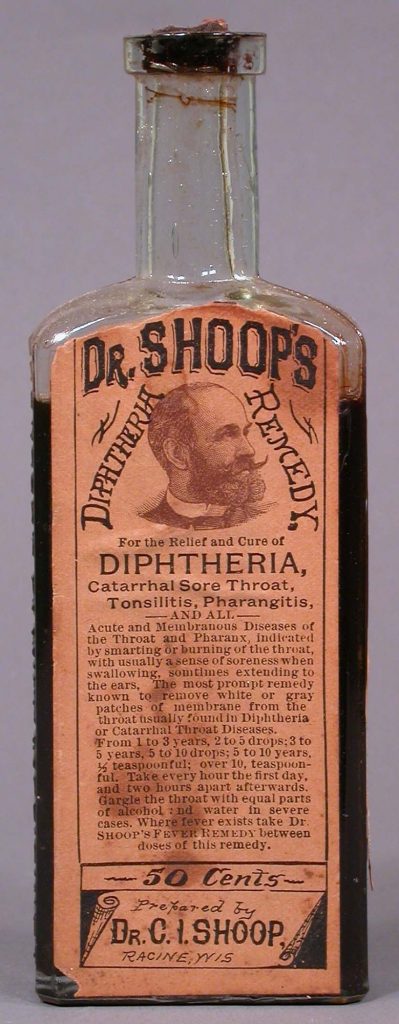

The following is an example of the many advertisements that were prevalent in local newspapers in the 1870s for remedies that purported cured or provided relief from Diphtheria.

Geneva, New York Daily Gazette, 4 January 1878 Page 3 – Cures for Diphtheria

These treatments were largely symptomatic and aimed at managing the airway obstruction caused by the pseudomembrane. The actual effectiveness of these remedies was limited, and the mortality rate from diphtheria remained high until the development of antitoxin therapy in the 1890s.

Many patient medicines were advertised, such as Dr. Shoop’s Diphtheria Remedy (to the left). Medical regulation was less stringent and many of these medicines were used before the development of more effective treatments and vaccines for diphtheria. These types of remedies were often advertised widely but their effectiveness was typically unproven and they sometimes contained harmful substances.

The history of diphtheria treatment is characterized by three inventions—tracheotomy, intubation and serum therapy. These three intervention approaches were introduced between the 1840s and the 1890s. The development of antitoxin therapy was a pivotal moment, offering a real cure for the first time and paving the way for future advances in vaccines and public health strategies to combat the disease.

Until the turn of the 20th century, treatment options were limited. In order to try to save a patient from suffocation by the pseudomembrane, doctors performed tracheotomy or intubation procedures. Before the development of more specific treatments, tracheotomy was one of the few available interventions for diphtheria. This surgical procedure involved cutting an opening in the trachea to insert a tube, allowing air to bypass the obstructed or narrowed part of the throat. Despite its use, tracheotomy was a risky procedure with a high mortality rate due to complications such as infection. [34]

Developed by Dr. Joseph O’Dwyer in the 1880s, intubation was a less invasive alternative to tracheotomy. It involved inserting a tube into the larynx to keep the airway open without the need for an incision. O’Dwyer’s intubation technique became a critical life-saving intervention for diphtheria patients with obstructed airways. [35]

Intubation Kit

The set contains: 7 hard rubber O’ Dwyer tubes with metal obturators; One O’ Dwyer’s improved scale, an introducer; a intubation tube extractor; and one Denhardt’s mouth gag. “ORIGINAL MANUFACTURER OF DR. JOSEPH O’DWYER’S INTUBATION INSTRUMENTS FOR THE LARYNX”. A label on the interior lid reads “GEORGE EMROLD / MF’R of / SURGICAL INSTRUMENTS / 312 & 314 E 22 ST. NY.”

“Known familiarly as O’ Dwyer’s intubation tubes, sets came equipped with thin tubes made of metal or hard rubber of varying sizes, a scale for determining the correct size tube to be used, a mouth gag, an introducer for placing the tube down the throat, and an extractor, a forceps-like instrument for removing the tube.Inserting the tubes was a two person procedure. A thread is passed through the hole in the tube. The child is held in an upright position by the assistant holding the head back. A mouth gag paced in the mouth, and the doctor inserts the tube down the throat. Once the tube is in place the introducer is removed.” [36]

The discovery and development of diphtheria antitoxin in the 1890s marked a significant breakthrough in the treatment of diphtheria. Emil von Behring and Shibasaburō Kitasato’s work on immunizing animals with heat-treated diphtheria toxin and using their serum as an antitoxin for treatment was groundbreaking. This antitoxin, derived from the blood of immunized animals, neutralized the diphtheria toxin and could cure the disease in affected individuals. The introduction of antitoxin therapy dramatically improved the survival rates of diphtheria patients. [37]

The efficacy of serum therapy was further established through controlled trials and methodological advancements in medical research. Johannes Fibiger’s work in the late nineteenth century, which involved treating every other patient with serum and comparing outcomes, was an early example of a more rigorous approach to evaluating treatments. This helped solidify the role of serum therapy in treating diphtheria. [38]

Anti-Diphtheritic Serum No. 3, 1898 [39]

The widespread use of diphtheria vaccines would not occur until the 20th century. The development of the diphtheria toxoid vaccine in the 1920s was based on earlier research into antitoxin and toxin production. Vaccination campaigns in the early 20th century significantly reduced the incidence of diphtheria. [40]

Diphtheria Toxoid (Anatoxin-Ramon) Bio. 2100 – Diphtheria Prophylactic – Two Doses for One Person [41]

Sources

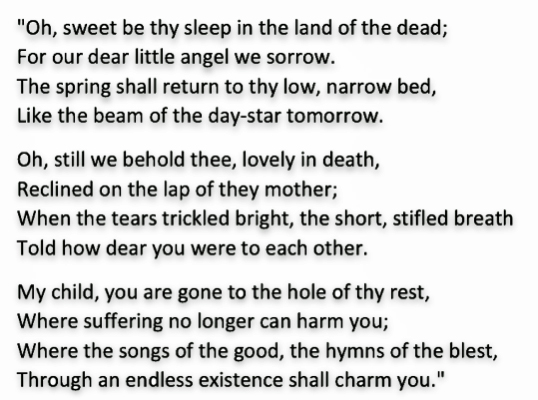

Feature Photograph: The feature photograph of this story is an amalgam of: (1) Notes on Missing Burial Grounds in Mayfield County by the Reverend Edward Ruliffson Mayfield Historian in the 1930s; (2) A list of the children of William J. Griffis and Charlotte (Wetherbee) Griffis; (3) a poem written by a mother who lost a child to diphtheria in the late 1870s (see below); (4) an illustration of a young girl suffering from diphtheria,.

(1) Notes on Missing Burial Grounds in Mayfield County by the Reverend Edward Ruliffson, Mayfield Historian in the 1930s, documents were shared by the Mayfield historian Eric Close, PDF Copy

(2) Children of William J. Griffis and Charlotte Wetherbee Griffis and their spouses:

(3) “For Addie Mehwalt, Age 2 Years, 7 months Alex and Mary Mehwalt, a young Santa Cruz couple, were so devastated by the death of their daughter that they found it necessary to move away from the area to contain their grief. They left behind one of the most beautiful poems in this collection.”

Reader, Phil. “Voices of the Heart: Memorial Poems from the Diphtheria Epidemic of 1876-78.” Santa Cruz, CA: Cliffside Publishing, 1993. SCPL Local History. https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/134500

(4) Cooper, Richard Tennant, Watercolor, Ghostly Skeleton trying to strangle a sick child Wellcome Collection, Reference Wellcome Collection 24006i, Reference Note: Robert E. Greenspan, Medicine: perspectives in history and art, Alexandria, Va.: Ponteverde Press, 2006, p. 319 (reproduced) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/mff3hsaw

One of several paintings commissioned by Henry S. Wellcome around 1912 from Richard Cooper, who was then working in Paris. Cooper was educated at Tonbridge and then trained as an artist in Paris before the First World War. In 1914 he joined the British Army and in 1916 was transferred to the Royal Engineers. His obituary in The times says that he worked on camouflage with Solomon J. Solomon RA as well as acting as official war artist for The graphic. After the war he enjoyed a flourishing career as a graphic artist designing posters: he is particularly well known for his advertisements for the London Underground

A ghostly skeleton trying to strangle a sick child; representing diphtheria. Watercolour by R. Cooper. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection.

[1] 1870 United States Federal census, New York, Fulton County, Mayfield, July 7, 1870, Page 258, Lines 16-21

Household of Thomas Wetherbee – 1870

[2] Personal notes by Mayfield town historian Edward Ruliffson, 1935. See footnote 12 in the April 2, 2024 story, Recent Discoveries from Oral History Compiled by a Local Mayfield Historian – Part II

[3] For a period of time, I was not certain was to why I was unable to find historical documentation on the first three daughters of William and Charlotte Griffis. See the following sources that discuss the challenges of tracing female ancestors in the United States.

Linda Clyde, Ever Wonder Why It’s So Hard to Trace Your Female Ancestry?, April 26, 2017, FamilySearch Blog, https://www.familysearch.org/en/blog/ever-wonder-why-its-so-hard-to-trace-your-female-ancestry

Candice Buchanan, Female Ancestors: Finding Women in Local History and Genealogy, Research Guides, Updated February 13, 2024, Library of Congress, https://guides.loc.gov/female-ancestors

I came upon newsletters for the interchange of genealogical data and history of the Weatherbee or Wetherbee (and variant spellings) families in America. Some early ancestors immigrated to the United States from England in the 1600’s. I was able to find terse yet direct confirmation of the early deaths and causes of death for the three daughters .

Carl & Lucile Weatherbee (with additional authors for specific family lines and queries), Weatherbee Round-up : A newsletter for all Weatherbee descendants, Volume 25, No. 4 July/Aug 1991 page 144 ; See Weatherbee round-up : a newsletter for all Weatherbee descendants, FamilySearch, https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/2262?availability=Family%20History%20Library

Carrie Esther Griffis, Geneanet, Born March 4, 1874, Deceased December 30, 1874, aged 9 months old, https://gw.geneanet.org/weterb1?lang=en&p=carrie+esther&n=griffis

Annie Grace Griffis, Geneanet, Born September 1, 1872, Deceased December 17, 1874, aged 2 years old, https://gw.geneanet.org/weterb1?lang=en&p=annie+grace&n=griffis

Florence Eliza Griffis, Geneanet, Born May 1, 1871, Deceased May 24, 1875, aged 4 years old, https://gw.geneanet.org/weterb1?lang=en&p=florence+eliza&n=griffis

[4] Ibid

[5] R. J. Honeywell, Updated 13-May-2008, Broadalbin in History, http://www.fulton.nygenweb.net/history/Broadhist1907a.html

[6] Beth Gruber, Marquette’s 1878 diphtheria epidemic, Jul 5, 2023, The Mining Journal, https://www.miningjournal.net/news/superior_history/2023/07/marquettes-1878-diphtheria-epidemic-2/

[7] Deadly Diphtheria: the children’s plague, October 26, 2017, post based upon the Dittrick Museum Diphtheria Exhibit, guest curated by Cicely Schonberg, Dittrick Meidcal History center Blog, College of Arts and Sciences, Case Western Reserve University, https://artsci.case.edu/dittrick/2014/04/29/deadly-diphtheria-the-childrens-plague/

[8] Map Showing Deaths from Diphtheria in the City of New York December 31, 1875, Pictures of life and character in New York, Page. 36. National Library of Medicine, Digital Collections, National Institute of Health, https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101425218-img http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101425218

Thomas R. Frieden, Public Health in New York City: 200 Years of Leadership , Tjhe New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2005, https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/bicentennial/historical-booklet.pdf

[9] “By April 1879 at least 75 people, mostly children, lost their lives. Over 400 of the village’s residents fell ill with the disease between September 1878 and March 1879. Whole families became sick, and a few parents lost all of their children to the disease. “

Anne Dealy, Diphtheria Epidemic, September 27, 2013, Historic Geneva Blog, https://historicgeneva.org/medicine/diphtheria-epidemic/

[10] Brian Altonen, The 1890 Census Disease Maps, Blog on Public Health, Medicine and History, https://brianaltonenmph.com/gis/more-historical-disease-maps/1890-the-1890-census-disease-maps/

[11] “One of several paintings commissioned by Henry S. Wellcome around 1912 from Richard Cooper, who was then working in Paris. Cooper was educated at Tonbridge and then trained as an artist in Paris before the First World War. In 1914 he joined the British Army and in 1916 was transferred to the Royal Engineers. His obituary in The times says that he worked on camouflage with Solomon J. Solomon RA as well as acting as official war artist for The graphic. After the war he enjoyed a flourishing career as a graphic artist designing posters: he is particularly well known for his advertisements for the London Underground.”

Cooper, Richard Tennant, Watercolor, Ghostly Skeleton trying to strangle a sick child Wellcome Collection, Reference Wellcome Collection 24006i, Reference Note: Robert E. Greenspan, Medicine: perspectives in history and art, Alexandria, Va.: Ponteverde Press, 2006, p. 319 (reproduced) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/mff3hsaw

[12] Michael Dwyer, Strangling Angel: Diphtheria and Childhood Immunization in Ireland, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2018

Foong Seong Kin, Mawaddah Azman, Bong Qi Yi, Yong Doh Jeing, Strangling angel of children- diphtheria: A case series of airway management and disease progress in diphtheria, International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology Case Reports, Volume 25, 2019, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2588910919300099?via%3Dihub

Byard, Roger W. Diphtheria – ‘The strangling angel’ of children. Journal of Forensic Legal Medicine, 2013 Feb; 20 (2): 65-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2012.04.006. Epub 2012 May 24.

Diphtheria ‘The Strangler’, Museum of Health Care at Kingston, https://www.museumofhealthcare.ca/explore/exhibits/vaccinations/diphtheria.html

Dwyer M. Introduction. In: Strangling Angel: Diphtheria and Childhood Immunization in Ireland. Reappraisals in Irish History. Liverpool University Press; 2017:1-12.

[13] Deadly Diphtheria: the children’s plague, October 26, 2017, post based upon the Dittrick Museum Diphtheria Exhibit, guest curated by Cicely Schonberg, Dittrick Medical History center Blog, College of Arts and Sciences, Case Western Reserve University, https://artsci.case.edu/dittrick/2014/04/29/deadly-diphtheria-the-childrens-plague/

See also:

Diphtheria, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diphtheria

Margaret Putnam Brennen, The Diphtheria Epidemic of 1874-1876. August 19, 2016, The Golden Crescent: Stories from the History of Lyme, NY, https://goldencrescent.weebly.com/home/category/diphtheria-epidemic

Perri Klass, How Science Conquered Diphtheria, the Plague Among Children, October 2021, Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/science-diphtheria-plague-among-children-180978572/

Ashley Hagen, The Toxin-Based Diseases Common in North America during the 1600-1700s, July 5, 2019, American Society of Microbiology, https://asm.org/articles/2019/july/the-toxin-based-diseases-common-in-north-america-d

[14] Diphtheria: Corynebacterium diphtheriae, The History of Vaccines, Mütter Museum, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, https://historyofvaccines.org/history/diphtheria/overview

[15] Diphtheria, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diphtheria

Diphtheria: Corynebacterium diphtheriae, The History of Vaccines, Mütter Museum, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, https://historyofvaccines.org/history/diphtheria/overview

[16] Caulfield, Ernest, “A True History of the Terrible Epidemic Vulgarly Called the Throat Distemper, Which Occurred in His Majesty’s New England Colonies between the Years 1735 and 1740.” The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Ser., Vol 6, No 2. p. 338., 1949

See also: Shulman, Stanford, The History of Pediatric Infectious Diseases , Pediatric Research. Vol. 55, No. 1, 2004

[17] Deadly Diphtheria: the children’s plague, October 26, 2017, Dittrick Medical Center Blog, https://artsci.case.edu/dittrick/2014/04/29/deadly-diphtheria-the-childrens-plague/

[18] Diphtheria: Corynebacterium diphtheriae, The History of Vaccines, Mütter Museum, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, https://historyofvaccines.org/history/diphtheria/overview

[19] The Sutliff Museum, A Million Ways to Die in the 19th Century, YouTube Video, Last updated on May 8, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=ePV-tu9y7cg ; www.sutliffmuseum.org Warren, Ohio

[20] Preston, Samuel H. and Michael R. Haines, The Social and Medical Context of Child Mortality in the Late Nineteenth Century, in Samuel H. Preston and Michael R. Haines, ed, Fatal Years: Child Mortality in Late Nineteenth-Century America, Princeton University Press, January 1999, Pages 3 – 48; Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/pres91-1 ; Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11541

[21] Aaron O’Neill, Child mortality in the United States 1800-2020, Feb 2, 2024, Statista , https://www.statista.com/statistics/1041693/united-states-all-time-child-mortality-rate

[22] Diseases and epidemics of the 19th century, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 20 January 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diseases_and_epidemics_of_the_19th_century

Cholera, Virtual New York, Graduate cener, City of New York (CUNY), https://virtualny.ashp.cuny.edu/cholera/cholera_intro.html

Richard Plunz and Andrés Álvarez-Dávila, Density, Equity, and the History of Epidemics in New York City State of the Planet, Columbia Climate School, June 30, 2020 , https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2020/06/30/density-equity-history-epidemics-nyc/

Echoes of Epidemics Past: Telling the Stories of New York’s Champions and Change Makers, April 24, 2020, Museum of the City of New York, https://www.mcny.org/story/echoes-epidemics-past

Shulman, Stanford T. The history of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Pediatr Res. 2004 Jan;55(1):163-76. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000101756.93542.09. Epub 2003 Nov 6. Erratum in: Pediatr Res. 2004 Jun;55(6):1069. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7086672/

Preston, Samuel H. and Michael R. Haines, The Social and Medical Context of Child Mortality in the Late Nineteenth Century, in Samuel H. Preston and Michael R. Haines, ed, Fatal Years: Child Mortality in Late Nineteenth-Century America, Princeton University Press, January 1999, Pages 3 – 48; Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/pres91-1 ; Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11541

Lorna Ebner, Quarantine in Nineteenth-Century New York , April 14, 2020, History of Medicine and Public Health, New York Academy of Medicine Library Blog, https://nyamcenterforhistory.org/2020/04/14/quarantine-in-nineteenth-century-new-york/

Nycole Neveol, Deadly Summers: Infant and Child Deaths in 19th Century Rochester, New York, State University of New York, Geneseo, https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1137&context=great-day-symposium

Thomas R. Frieden, Public Health in New York City: 200 Years of Leadership , Tjhe New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2005, https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/bicentennial/historical-booklet.pdf

Diseases and epidemics of the 19th century, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 20 January 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diseases_and_epidemics_of_the_19th_century

Condran, Gretchen A., and Harold R. Lentzner. “Early Death: Mortality among Young Children in New York, Chicago, and New Orleans.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 34, no. 3, 2004, pp. 315–54. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3657041

Godias J. Drolet and Anthony M. Lowell, A Half Century’s Progress Against Tuberculosis in New York City 1900 – 1950, New York Tuberculosis and health Association, 1952, https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/tb/tb1900.pdf

Diseases and epidemics of the 19th century, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 20 January 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diseases_and_epidemics_of_the_19th_century

[23] Notes on Missing Burial Grounds in Mayfield County by the Reverend Edward Ruliffson, Mayfield Historian in the 1930s, documents were shared by the Mayfield historian Eric Close, PDF Copy

[24] Wendy Chestnut , Burial customs differed at turn-of-the-century, April 11, 2024, Williamsport Sun-Gazette, https://www.sungazette.com/news/top-news/2018/04/burial-customs-differed-at-turn-of-the-century/

Mattie Aguero, Evolution of American Funerary Customs and Laws, September 28, 2022, Library Congress Blogs , https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2022/09/evolution-of-american-funerary-customs-and-laws/

[25] Mattie Aguero, Evolution of American Funerary Customs and Laws, September 28, 2022, Library Congress Blogs , https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2022/09/evolution-of-american-funerary-customs-and-laws/

Burkette A. The Burial Ground: A Bridge Between Language And Culture. Journal of Linguistic Geography. 2015;3(2):60-71. doi:10.1017/jlg.2016.2 ; https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-linguistic-geography/article/burial-ground-a-bridge-between-language-and-culture/F7DFEB1AC003DB2575148448E0AF2782

[26] Sources for burial:

List of Wetherbee family member memorials found in Broadalbin-Mayfield Rural Cemetery: www.findagrave.com

List of Griffis family member memorials found in Broadalbin-Mayfield Rural Cemetery: www.findagrave.com:

Archibald Clark, West Galway Cemetery, West Galway, Fulton County, Memorial ID: 29292190, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/29292190/a-clar

[27] Ann Dealy, Diptheria Epidemic, Sep 27 2013, Historic Geneva, https://historicgeneva.org/medicine/diphtheria-epidemic/

Deadly Diphtheria: the children’s plague, Oct 26, 2017, Dittrick Medical History center blog, Case Western Reserve, https://artsci.case.edu/dittrick/2014/04/29/deadly-diphtheria-the-childrens-plague/

Phil Reader, Voices of the Heart: Memorial Poems from the Diphtheria Epidemic of 1876-78, Santa Cruz Public Libraries Local History, https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/files/original/ff77baa4aaefd6c8b03fdcda3d1a59ed.pdf

[28] Ann Dealy, Diptheria Epidemic, Sep 27 2013, Historic Geneva, https://historicgeneva.org/medicine/diphtheria-epidemic/

[29] Ann Dealy, Diptheria Epidemic, Sep 27 2013, Historic Geneva, https://historicgeneva.org/medicine/diphtheria-epidemic/

Deadly Diphtheria: the children’s plague, Oct 26, 2017, Dittrick Medical History center blog, Case Western Reserve, https://artsci.case.edu/dittrick/2014/04/29/deadly-diphtheria-the-childrens-plague/

[30] Ann Dealy, Diptheria Epidemic, Sep 27 2013, Historic Geneva, https://historicgeneva.org/medicine/diphtheria-epidemic/

Deadly Diphtheria: the children’s plague, Oct 26, 2017, Dittrick Medical History center blog, Case Western Reserve, https://artsci.case.edu/dittrick/2014/04/29/deadly-diphtheria-the-childrens-plague/

Phil Reader, Voices of the Heart: Memorial Poems from the Diphtheria Epidemic of 1876-78, Santa Cruz Public Libraries Local History, https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/files/original/ff77baa4aaefd6c8b03fdcda3d1a59ed.pdf

[31] Deadly Diphtheria: the children’s plague, Oct 26, 2017, Dittrick Medical History center blog, Case Western Reserve, https://artsci.case.edu/dittrick/2014/04/29/deadly-diphtheria-the-childrens-plague/

Phil Reader, Voices of the Heart: Memorial Poems from the Diphtheria Epidemic of 1876-78, Santa Cruz Public Libraries Local History, https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/files/original/ff77baa4aaefd6c8b03fdcda3d1a59ed.pdf

[32] Use of Disinfectants: Druggist E. Maynard recommended the use of disinfectants in the sick-room and for all vessels containing secretions from the sick, which likely helped prevent the transmission of the disease. See Dealy, Ann, Diphtheria Epidemic, September 27, 2013, Historic Geneva Blog, https://historicgeneva.org/medicine/diphtheria-epidemic/

Gargling with Kerosene Oil: This was suggested as a cure, though it was not based on any scientific evidence and was likely ineffective or even harmful2. For example see: Medical Hints: DIPHTHERIA AND PETROLEUM, The Sacred Heart Review, Volume 11, Number 26, 19 May 1894, Newspaper records maintained by Boston College Libraries, https://newspapers.bc.edu/?a=d&d=BOSTONSH18940519-01.2.48&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——- ; see also Young, D.W. , An Article on Malignant Diphtheia, with Report on Eleven Cases, The Chicago Medical Examiner Vol VI, No 1, Jan 1865 , https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9997272/pdf/chicmedex137054-0001.pdf

Calomel Treatment: Calomel, or mercurous chloride, was used as a treatment, though its efficacy and safety were questionable. See for example: Batten John M. , The Treatment of Diphtheria, Read before the Pennsylvania State Medical Society in May, 1892. JAMA. 1893; XX(15): Pages 406–408. doi:10.1001/jama.1893.02420420002001a https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/470168

[33] Dr. Shoop’s Diphtheria Remedy was manufactured around the period of 1892 to 1920. This timeframe is indicated by the physical description note of the bottle that contained Dr. Shoop’s Family Medicine, which includes “Dr. Shoop’s Restorative” and is associated with the same Dr. C. Irving Shoop who had a large list of patent medicines. The bottle is dated circa 1892-1920, which suggests that Dr. Shoop’s Diphtheria Remedy would have been produced within that same general time period.

See: Dr Shoop’s Diphtheria Remedy, National Museum of American History, The Smithsonian Institution, https://www.si.edu/object/dr-shoops-diphtheria-remedy%3Anmah_716374

See also: Greer, David S., Guide to the Patent medicine bottle collection, 1850-1920, Box 3, Bottle 76 – Dr. Shoop’s Family Medicine, John Hay Library, University Archives and Manuscripts,Brown University, 2023, https://www.riamco.org/render?eadid=US-RPB-ms2008.002&view=all

Carters compound extract of smartweed was an Opium laced herbal formula that emerged in 1871. Carter’s Compound Extract of Smartweed was a medicinal product manufactured by the Brown Medicine Company in Erie, Pennsylvania. This product was part of the broader category of patent medicines that were popular in the United States during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Patent medicines, including Carter’s Compound Extract of Smartweed, were often advertised as cure-alls for a wide range of ailments and conditions.

The history of patent medicines like Carter’s Compound Extract of Smartweed is intertwined with the history of medicine and advertising in America. These products were typically sold directly to the public through advertisements in newspapers, magazines, and via traveling medicine shows. They were known for their bold claims and were often marketed as effective treatments for multiple unrelated diseases. One notable aspect of Carter’s Compound Extract of Smartweed, as with many patent medicines of the time, was its composition. The article from pressrepublican.com mentions that Carter’s Extract of Smartweed was an opium-laced herbal formula. This highlights a common practice of the era, where potent substances such as opium, alcohol, cocaine, and morphine were frequently included in the ingredients of patent medicines. These substances often contributed to the medicines’ effects, making them popular but also potentially dangerous.

See: Julie Robinson Robards, A dose of patent medicine history, Jul 16, 2012, Press-Republican, https://www.pressrepublican.com/news/lifestyles/a-dose-of-patent-medicine-history/article_fc67e7c5-e13b-5269-b8e6-3d6640f23064.html

[34] Diphtheria: Corynebacterium diphtheriae, The History of Vaccines, Mütter Museum, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, https://historyofvaccines.org/history/diphtheria/overview

Deadly Diphtheria: the children’s plague, October 26, 2017, post based upon the Dittrick Museum Diphtheria Exhibit, guest curated by Cicely Schonberg, Dittrick Meidcal History center Blog, College of Arts and Sciences, Case Western Reserve University, https://artsci.case.edu/dittrick/2014/04/29/deadly-diphtheria-the-childrens-plague/

Dealy, Ann, Diphtheria Epidemic, September 27, 2013, Historic Geneva Blog, https://historicgeneva.org/medicine/diphtheria-epidemic/

Diphtheria, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diphtheria

[35] Diphtheria: Corynebacterium diphtheriae, The History of Vaccines, Mütter Museum, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, https://historyofvaccines.org/history/diphtheria/overview

Diphtheria, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diphtheria

[36] Intubation Kit, National Museum of American History, The Smithsonian Institution , Object Details, https://www.si.edu/object/intubation-kit:nmah_1090324

[37] Diphtheria: Corynebacterium diphtheriae, The History of Vaccines, Mütter Museum, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, https://historyofvaccines.org/history/diphtheria/overview

Diphtheria Treatments and Prevention, the Antibody Initiative, The Smithsonian Institution, https://www.si.edu/spotlight/antibody-initiative/diphtheria

Diphtheria, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 5 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diphtheria

[38] Annick Opinel, Ulrich Tröhler, Christian Gluud, Gabriel Gachelin, George Davey Smith, Scott Harris Podolsky, Iain Chalmers, Commentary: The evolution of methods to assess the effects of treatments, illustrated by the development of treatments for diphtheria, 1825–1918, International Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 42, Issue 3, June 2013, Pages 662–676, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyr162

[39] Anti-Diphtheritic Serum No. 3, 1898, In 1898, the Smithsonian museum collected from some of the earliest commercial antitoxin manufactured in America from Parke, Davis & Co.: Diphtheria Treatments and Prevention, The Antibody Initiative, The Smithsonian Institution, https://www.si.edu/spotlight/antibody-initiative/diphtheria

[40] Diphtheria Treatments and Prevention, the Antibody Initiative, The Smithsonian Institution, https://www.si.edu/spotlight/antibody-initiative/diphtheria

Deadly Diphtheria: the children’s plague, October 26, 2017, Dittrick Medical Center Blog, https://artsci.case.edu/dittrick/2014/04/29/deadly-diphtheria-the-childrens-plague/

[41] Diphtheria Toxoid (Anatoxin-Ramon) Bio. 2100 – Diphtheria Prophylactic – Two Doses for One Person, Diphtheria Treatments and Prevention, The Antibody Initiative, The Smithsonian Institution, https://www.si.edu/object/diphtheria-toxoid-anatoxin-ramon-bio-2100-diphtheria-prophylactic-two-doses-one-person:nmah_716527