Establishing accurate family histories requires the careful evaluation of multiple sources of information to document facts and to reach reliable conclusions. This story touches on the general methods in the field of genealogy for examining evidence. I provide a few practical examples and a simple approach from my research to make these general guidelines come to life.

“The process of genealogical research seeks information (facts about events) to answer questions (research objectives) about people. The records searched are the source of the information; therefore you must evaluate both the information you found and the record(s) in which you found it. When considering the record, evaluate its relevance, category, and format.

“When considering the information, compare it and corroborate it with information you have found in other independent sources … . Also, evaluate the information itself on its own merits taking into consideration: origin of the information, facts given in the records, events described, and directness of the evidence. ” [1]

Long before the concept of “alternative facts” entered the lexicon of modern everyday life [2], the American rock band, Talking Heads, explored the idea in a song “Crosseyed And Painless,” [3] which is written from the perspective of a someone that is not certain of what is real.

Well, facts do indeed matter and sometimes they are a delight or a revelation when discovered. Sometimes they do not conform to our expectations in genealogical research and there is a temptation to continue to look for other facts to support a different view.. Facts at times can be directly empirically verified. Other times facts are from derivative sources or the testimony of others. Facts also can be verified by absence of information. Facts often require a comparison with other facts to assess their reliability.

The fundamental issue is how facts relate as evidence to statements we might make about a family member or about other genealogical matters.

For such a small four letter word, there are many meanings of the word ‘fact‘. The term takes on different shades of meaning depending on its use. It has different, nuanced meanings in philosophical, scientific, historical, mathematical, legal and genealogical perspectives. Perhaps in ‘common’ language, a fact is something that is known to have happened or to exist, especially something for which some form of proof exists, or about which there is information.

What is a fact? [4]

Here are a few definitions of the word ‘fact’:

- A fact is something that has really occurred or is the case.

- A fact is a piece of information that is indisputable and can be proven true or false.

- It is a statement about reality that is supported by evidence and can be verified through observation or measurement.

- Facts are objective and do not depend on personal opinions or beliefs. When you refer to something as a fact or fact , you mean that you think it is true or correct.

- A fact is a statement that can be verified. It can be proven to be true or false through objective evidence.

- A fact is the truth about events as opposed to interpretation.

- A fact is something that actually existed or had existed or occurred.

- A fact is a thing that is known or proved to be true. In a scientific view, a fact is an indisputable observation of a natural or social phenomenon. We can see it or demonstrate that it exists directly and show it to others.

From a ‘genealogist’s‘ point of view, it is safe to state that a fact is information associated with or about an individual family member, family, family object, property or action that is purported to be true.

Genealogical Facts and Evidence

These ‘facts’ or ‘events’ may be about a photo, an event, a period of time, a specific person, a couple, siblings, a branch of the family, or set of families. A genealogical story could be based on a multitude of possible organizing facts that define the boundary of a given story. That is the beauty of telling a story. Unless you are writing pure fiction, you need some facts that are reliable and can be documented.

Genealogical evidence is information used to document family relationships, life events, and historical facts about ancestors. It consists of evidence found in historical information (records, documents, and other sources) that help establish genealogical conclusions.

‘Evidence’ like ‘fact’ is also a word that has many meanings and interpretations. However, one might simply state that “evidence is an ‘assembly’ of facts indicating whether a belief or proposition is true or false”. [5]

Evidence is always gathered and presented either in support of or in opposition to an assertion about facts we have of an individual family member, family, a family object, property or action. When considering evidence, the most important aspect is whether the facts are relevant to the statement being examined. Facts in themselves have no purpose or agenda associated with them. [6]

For a genealogist, a fact is or facts are information used as evidence for substantiating the truthfulness of a something. Edward Hallett Carr, a British historian argued that ‘facts do not speak for themselves’. He argued that the historian can pick and decide which facts deserved to be shown, the order they are shown, and their context. Since the past is itself filled with facts, these facts are sifted, interpreted and analyzed for their relevance and value. [7]

(Facts) … “are like fish swimming about in a vast and sometimes inaccessible ocean; and what the historian catches will depend, partly on chance, but mainly on what part of the ocean he chooses to fish in and what tackle he chooses to use – these two factors being, of course, determined by the kind of fish he wants to catch. By and large, the historian will get the kind of facts he wants. History means interpretation.” [8]

Adapting Carr’s view on what is history and the role of the historian to the field of genealogy, genealogists are engaged in a continuous process of moulding their facts to their interpretation and their interpretation to facts. [9]

Genealogical facts never come to us or exist in a pure form. Genealogical facts are rarely ‘complete and unbiased’ to tell us something relevant to understanding the past. They usually need some corroboration from other sources. Facts do not care about our intended goals for their use, nor are they interested in our story.

“The reliability of any historical statement depends upon the perception of the participant who first reported or recorded it. The reliability of a genealogical conclusion, in turn, rests not just upon the accuracy of the original informant(s) but also upon the researcher’s understanding of what the informant(s) meant to say, as well as the researcher’s judgment in a number of other matters: the choice of sources, the thoroughness of the investigation, the analysis of information, the correlation of details, and the conclusions drawn—for starters.” [10]

Evidence always considers relevance. Evidence is a selected subset of all available facts chosen because they are deemed relevant to determining the validity of a genealogical assertion, similar to the fish simile in the Carr’s quote above.

Therein lies the rub. Who determines which facts are considered relevant? Who determines what evidence to use? What is the concluding assertion?

“No technique can be said to constitute the gold standard because there is no gold standard. … The common assertion of a gold standard of evidence is merely a rhetorical device. … The hard truth is that we have little choice but to adapt in creative ways to the kinds of evidence that social scientists confront.” [11]

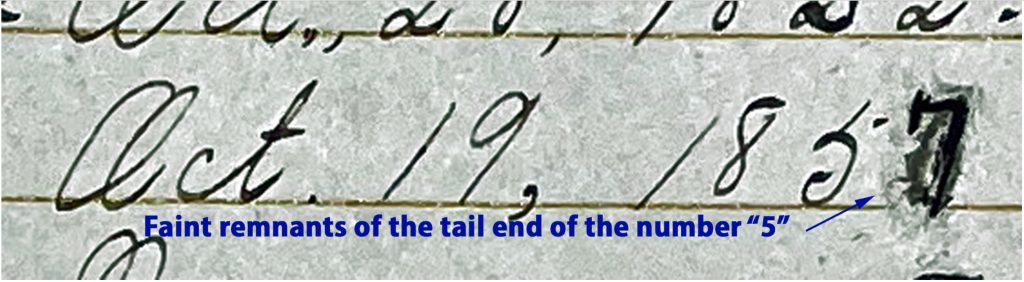

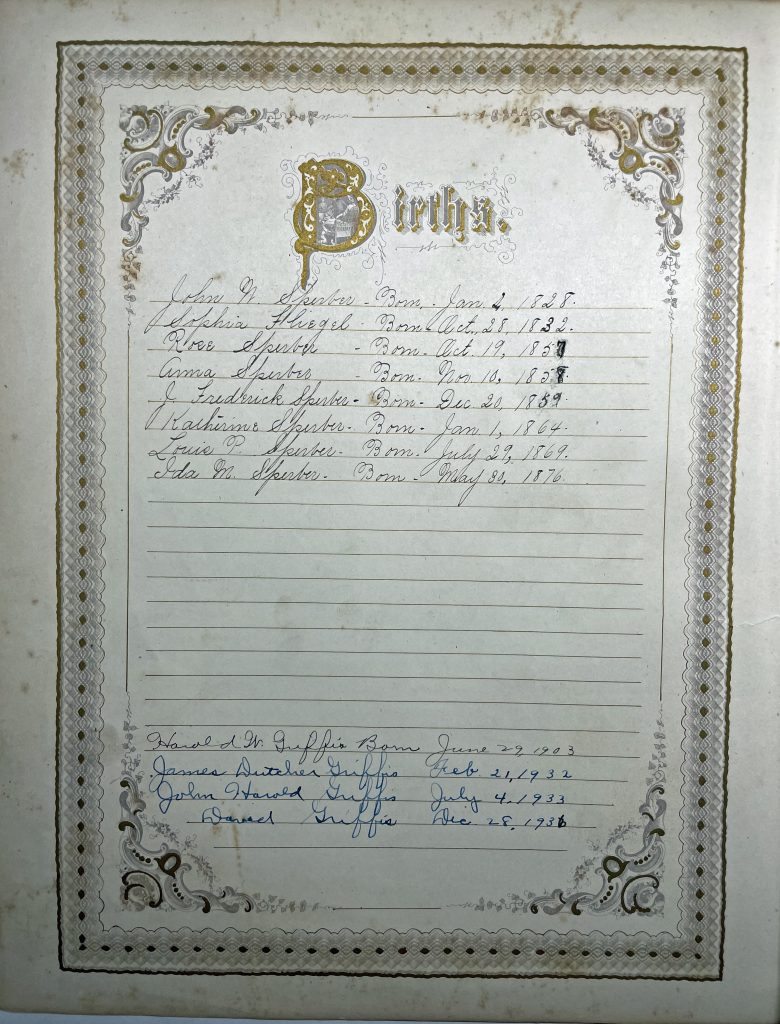

“Revised” Birth Date of Rose Sperber [12]

I have found military records that misspell a great-great grand-uncle’s surname that died in a Confederate prison. [13] I have found family records that were ‘revised’ to hide an unwed birth. [14] I have found many sources that provide multiple ways in which my surname has been spelled for Griffis relatives. [15] The list goes on. All of these require alternative sources of facts to corroborate or refine evidence for statements about a genealogical fact.

The accuracy of any source is unknown until the one has accumulated enough evidence for ‘tests of correlation‘ —the comparison and contrasting of sources and information to reveal points or degrees of agreement. [16]

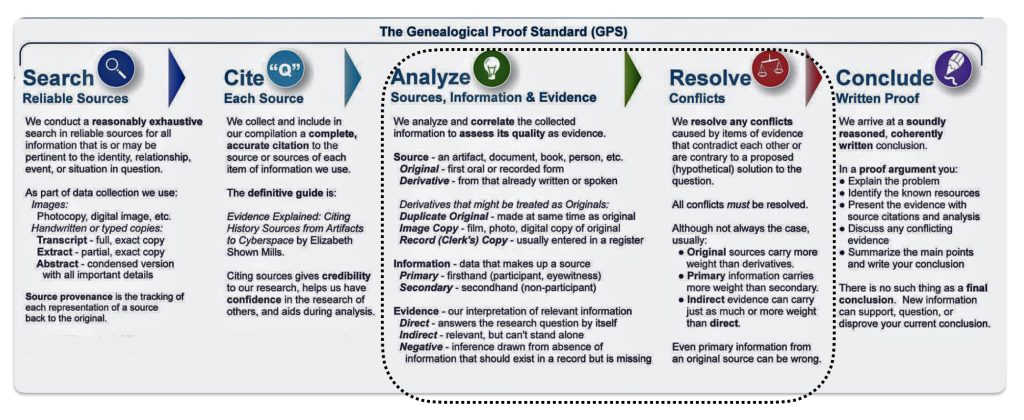

Evaluating Evidence in the Context of the Genealogical Proof Standard

The Genealogical Proof Standard (GPS) is a guideline established by the Board for Certification of Genealogists for determining the reliability of genealogical conclusions with reasonable certainty. Evaluating genealogical evidence is two of the five parts of the overall genealogical proof process: analysis and resolution. [17]

The Genealogical Proof Standard: Highlighting the Analysis & Resolution Stages

The GPS serves as a benchmark for quality in genealogical research, helping both professional and amateur genealogists maintain credibility in their work. The GPS consists of five essential elements or standards:

1. Reasonably Exhaustive Research: Research should be systematic and broad in scope; and all relevant and available records should be identified and searched.

2. Complete and Accurate Source Citations: Each statement of fact requires proper documentation; and sources should be thoroughly documented for verification.

3. Analysis and Correlation of Information: Evidence should be analyzed, interpreted and correlated; and information from multiple sources must be compared and evaluated.

4. Resolution of Conflicting Evidence: Contradictory evidence should be addressed and resolved. Researchers should not ignore evidence that disagrees with their conclusions.

5. Soundly Reasoned Conclusion: Conclusions should be coherently written. Arguments or narratives should be based on the strongest evidence.

There is a wide range of written discourse on the “how to’s” of conducting genealogy research and assessing facts, evidence and their respective sources. Many of these written resources are highly informative and provide excellent ‘tips of the trade’. [18]

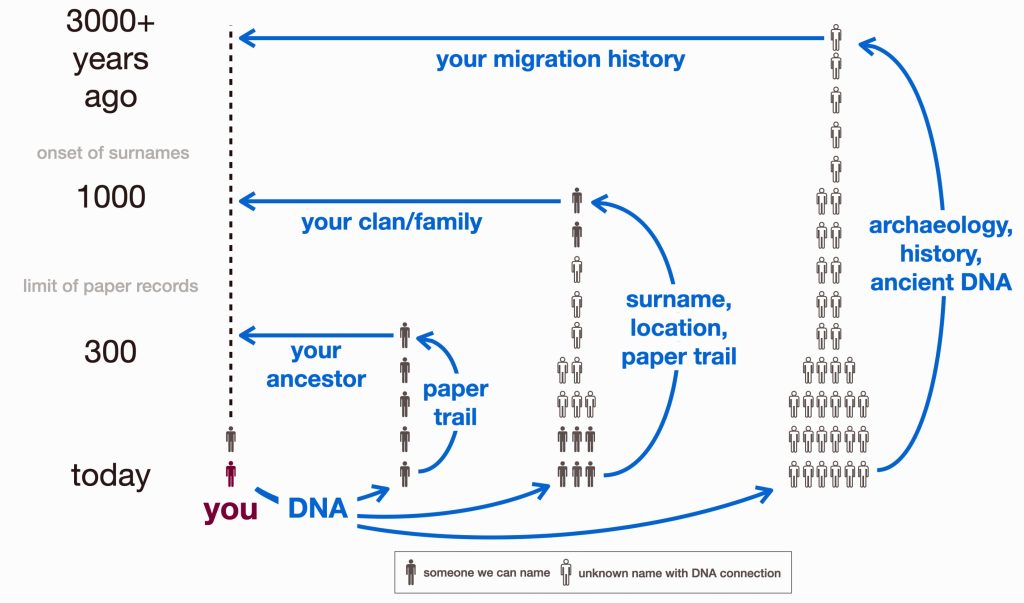

Many of these sources on conducting genealogical research start with distinguishing between primary and secondary sources of facts or evidence. Primary sources of information about facts or events are original, first-hand accounts of an event or time period. Secondary sources are interpretations and analyses of primary sources by someone other than the original author. [19]

The distinction between primary and secondary sources can vary depending on the context and the type of research being conducted. It is possible that some sources can function as both primary and secondary sources, depending on the research question and the interpretation of the researcher.

The distinction of primary, secondary or derivative sources of information are often times overlapping. Any source can offer both primary and secondary information. Original sources can also contain secondary information. Derivative sources of information can include primary information. The ambiguity of these categories of sources of information has led the governing body of accreditation for professional genealogists to avoid the use of the terms of primary and secondary sources. [20]

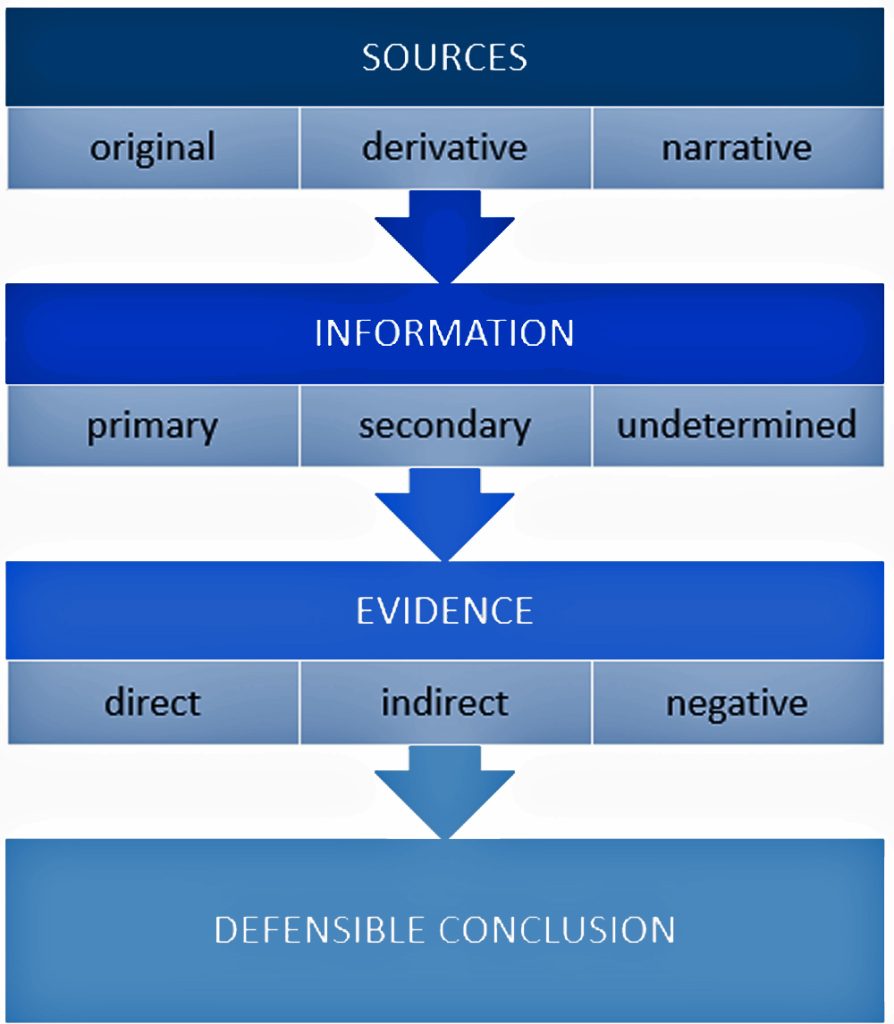

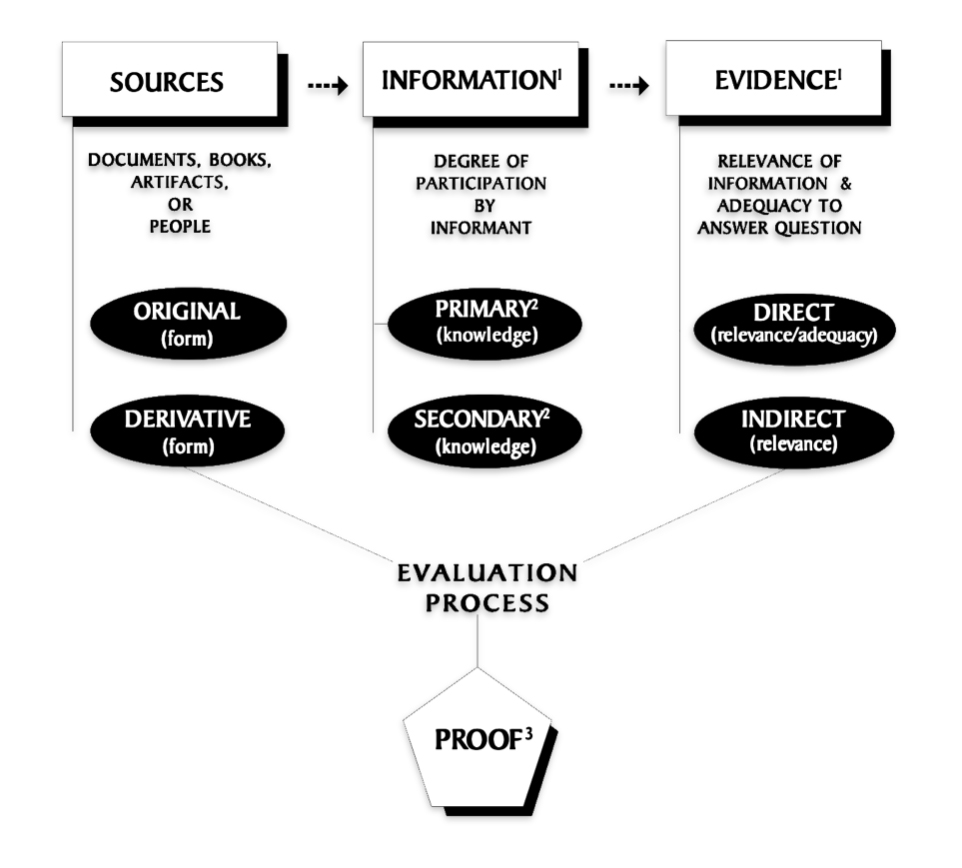

Evidence Analysis Process

In the late 1990’s, Elizabeth Shown Mills provided an ‘Evidence Analysis Process Map’ (EAP). The conceptual ‘map’ is a framework for evaluating genealogical information that follows a clear progression: sources provide information from which we select evidence for analysis, leading to sound conclusions that may be considered proof.

“Fulfilling a long-overdue need, a specific standard of proof has been crafted to cover the distinctive concerns of genealogical research. Terminology has been refined to eliminate conflicts between genealogical applications and usage common elsewhere.“ [21]

The Evidence Analysis Process (EAP) and the Genealogical Proof Standard (GPS) work together as complementary frameworks in genealogical research, with the Evidence Analysis Process supporting the achievement of GPS requirements. The EAP supports GPS’s requirement for soundly reasoned conclusions by providing a clear framework for: analyzing evidence strength, evaluating source reliability and assessing information quality.

The Evidence Analysis Process directly supports the third element of GPS by providing a structured method for analyzing and correlating collected information. The Evidence Analysis Process strengthens the fourth GPS element by providing a methodical way to evaluate and resolve contradictory evidence. Through careful source evaluation and information analysis, researchers can better address conflicting information.

There were a few modifications to the EAP map since 1999. [22] Presently the EAP map outlines three sources of information, three types of information and three types of evidence. [23]

The Evidence Analysis Process Map (EAP)

The EAP is a framework for evaluating genealogical research that follows three main stages: Sources, Information, and Evidence. It provides a concetual approach to evaluating and analyzing information from various sources and the origin of the information. The EAP emphasizes the importance of assessing the reliability of each source. Researchers should carefully examine the origin and nature of each fact, and document their sources. This helps determine the weight to give to different pieces of information when conflicts arise regarding the reliability of information.

As reflected in the diagram above, the EAP Map consists of three main sequential steps that lead to a conclusion:

- Sources: The process begins with gathering and evaluating source materials. This first step deals with the document or object itself, not the data the the source transmits. Examining the document is necessary because doing so will assist in determining the credibility of the information found in the document or object. [24]

- Information: After the source (the document or object itself) has been examined, the next category to consider is the information is the facts or data recorded on the source. Sources provide information that must be assessed for credibility and reliability. [25]

- Evidence: Information is analyzed to select relevant evidence that supports or contradicts the research question [26]

The Evidence Analysis Process Map encourages researchers to correlate details and compare information from multiple sources. This systematic approach helps identify patterns, dissimilarities, or conflicts that could strengthen or weaken a conclusion. This consideration is vital in assessing the strength of corroborating or conflicting evidence.

Practical Application: Levels of Certainty

While classifying a source or type of information is important, whether a source is original or derivative is not an indication of the reliability of the information it contains. To determine that, we need understand the source of the information or fact and how it was created.

In my attempt to document the events or specific facts associated with relatives, I utilize a wide range of primary and secondary genealogical and historical sources as well as original and derived sources of data when I am focused on a specific fact. I try to assess the reliability of those sources and then make decisions about how to use those facts. Sometimes a decision is made not to use a “fact”. I conclude that there is not enough documentation to use it as evidence. I may provide information on a particular dead end fact as ‘posted note’ for future research.

“Within sound genealogical studies, information statements about dates, identities, places, relationships, and similar matters are frequently prefaced by such terms as apparently, likely, possibly, or probably—all denoting that the stated “fact” is clouded by doubt. To date, these terms have no concrete definitions; practically speaking, they take on whatever shade each individual researcher provides with his or her supporting detail.” [27]

I have developed a rudimentary five point, ordinal scale that reflects how I evaluate the general evidence about a given genealogical statement. (See table one below.) It is not intended to be a rigorous scale to evaluate facts and evidence.. It is basically an heuristic construct to put things into perspective and to couch my assessments of various sources of facts when beset with conflicting information. [28]

Table One: Levels of Factual Reliability and Genealogical Evidence

| Proof Level | Level of Certainty “Common Language Qualifiers” | Consistency Between Sources & Examples / Types of Sources of Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| ONE | Conclusive Convincing “Is /Was” | ► Facts are consistent between all available record sources. ► Evidence supported by variety of independent records, direct and indirect sources. |

| TWO | “Very Likely” “With Noted Exceptions” | ► Information is consistent between available records sources with few exceptions. ► Majority of evidence supported by information from a variety of independent record sources. |

| THREE | “Probable” “Most Likely” | ► Evidence supported by variety of record sources.. ► A majority of various document sources provide similar information. |

| FOUR | “Likely” | ► Limited sources of conflicting evidence. ► At least half of all types of various document sources provide similar information. |

| FIVE | “Possible” | ► Limited sources of conflicting information. Indirect or negative evidence is relied upon to make a decision on available evidence. |

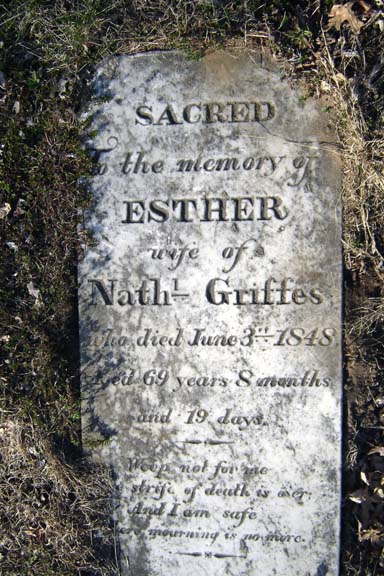

The Spelling of Nathaniel’s Surname

An example of this research process can be demonstrated in my research on determining the surname spelling for Nathaniel Griffes, as discussed in a prior story. Nathaniel Griffes is my fourth great grand-uncle. He was the sixth child of twelve children of William Griffis and Abiah Gates Griffis – the last common documented ancestor of the Griffis family in America. Nathaniel and his descendants are the only family branch to spell their surname as such.

My research on the various branches of the family surname led me to the conclusion that there were three variants in the spelling of the surname: Griffis, Griffith and Griffes. In my attempt to document the different spellings of the surname within and across generations of the family, I have compared various genealogical sources for an individual person and assessed the reliability of those sources.

The ‘ordinal scale of proof’ can be used as a heuristic guide to determine how I assessed various sources of evidence for the spelling of Nathaniel’s surname and for a given individual in his family.

In many cases, if I was able to find a family or individual headstone, I figured a headstone with a name carved into the stone reflected a convincing basis of how the surname was spelled in that time period. While mistakes have been made on head stones, the amount of effort put into creating a marker for an individual’s burial place is much more involved than simply transcribing a name on paper. Proof of a headstone and its spelling of the surname also may have influenced my views on how an individual’s immediate family may have spelled their surname since they were the ones that had the tomb stone made.

I have documented ‘conclusive’ evidence to support the statement that Nathaniel and his descendants spelled their surname as Griffes. There is evidence supported by variety of independent records that are either direct and indirect sources.

- In the 1810 U.S. Census his name is spelled Griffis. [29]

- In the 1820 census, it is spelled Griffies. [30]

- In the 1840 census it is spelled Griffes. [31]

- A Nathaniel Griffis is found as an enlisted Revolutionary soldier in Albany in 1776. [32] Church records indicate that his name was spelled as Griffes. [33]

- His Will [34] and probate records also reflect that his name was spelled Griffes. [35]

- Burial documentation reflects his name was spelled Griffes and there is a large family presence of Griffes family members in Vale cemetery in Schenectady, New York. 19 members of the Griffes family were buried in the cemetery. [36]

Table Two: Applying the Ordinal Scale in the Spelling of Nathaniel Griffes’ Name

| Proof Level | Level of Certainty “Common Language Qualifiers” | Consistency Between Sources & Examples / Types of Sources of Evidence | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| ONE | Conclusive Convincing “Is /Was” | ► Facts are consistent between all available direct record sources. ► Evidence supported by variety of independent records, direct and indirect sources. | “Nathanial and his descendants spelled their surname as Griffes” |

How Old was John Sperber?

Another example determining the reliability of facts and evidence in family research is how I determined when my second great grandfather Johann Wolfgang Sperber was born. Table three provides information on facts and evidence using the EAP Mapping model.

Table Three: When was John Wolfgang Sperber Born

| Source | Information | Evidence | Birth Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original: National Archive’s micro- publication M237 “Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, 1850-1856 , Rolls 85.-169 | Secondary: Three J. Sperber’s found: ▸ age 26, ar. 1952 ▸ age 26, ar. 1956 ▸ age 26, ar. 1955 One W. Sperber found: ▸ age 26, ar. 1953 | Negative: The records provide variable information on a J. Sperber or W. Serber arriving from European ports between 1850 and 1856; do not know if it is John W Sperber. | Uncertain |

| Original: Marriage Certificate of John Wolfgang Sperber and Sophia Fliegel | Primary: John and Sophia were married on 2 Feb 1857 in Gloversville, N.Y. | Negative : The record does not mention his age. The record does not directly address the research question. | Uncertain |

| Orignal: 1865 N.Y. State Census, New York State Archives; Albany, New York, USA; Census of the State of New York, 1865, Page 387, Line 33 | Secondary: Enumerator documented his age as 35. This would imply he was born in 1828 | Direct: The record does directly address his age. | 1828 |

| Original: 1870 Federal Census; Johnstown, Fulton, New York; Roll: M593_938; Page: 183A | Secondary: Enumerator documented his age as 41. This would imply he was born in 1828 | Direct: The record does directly address his age. | 1828 |

| Original: 1875 N.Y. State Census, Fulton, , Johnstown, E.D. 02,Page 428, Line 30, New York State Archives; Albany, NY, USA; | Secondary: Enumerator documented his age as 47. This would imply he was born in 1828 | Negative: The record does directly address his age. | 1828 |

| Original: 1880 Federal Census, Gloversville, Fulton, New York; Roll: 834; Page: 95A, Line 30; Enumeration District: 006 | Secondary: Enumerator documented his age as 51. This would imply he was born in 1829 | Direct: The record does directly address his age. | 1829 |

| Original: 1900 U.S. Federal Census, National Archives & Records Administration, Gloversville Ward 1, Fulton, New York; Roll: 1036; Page: 5; Enumeration District: 0006, Page 5, Line 98. | Secondary: John Sperber reported as 72 years old, | Indirect: The record directly addresses age. | 1828 |

| Derivative: Find A Grave, Memorial ID: 158839082, Plot Section 8, Prospect Hill Cemetery, Gloversville, Fulton County, New York | Primary: Inscription on head stone: “Father”. Additional information in memorial states John was born 2 Jan 1828 in Baden, Germany. | Indirect: The record indicates his birth year. | 2 Jan 1828 |

It appears that with few exceptions, available documentation on John Sperber suggests that he was born in 1828 and possibly on January 2nd.

Table Four: Applying the Ordinal Scale for Determining John Sperber’s Birth Year

| Proof Level | Level of Certainty “Common Language Qualifiers” | Consistency Between Sources & Examples / Types of Sources of Evidence | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| TWO | “Very Likely” “With Noted Exceptions” | ► Information is consistent between available records sources with few exceptions. ► Majority of evidence supported by information from a variety of independent record sources. | “With noted exceptions, documentation indicates that John Sperber was born in 1828.” |

Conclusion

In the end, the best combination of sources of proof involve first hand accounts along with objective, independent corroborating sources. Without that combination, it comes down to gradations of informed hunches. The key is providing a written explanation of how you reached your conclusions.

Indirect sources require corroboration. One thing I am certain is you cannot totally rely on how census or tax roll enumerators, or military pay rolls spelled names in their documents. I imagine the recorders of information relied on what they heard from who ever answered door or what they heard and spelled phonetically. How questions were phrased also play a part in the type of answers that are provided. You are also faced with deciphering their handwriting. [37]

Three Stooges Skit on a Census Taker: Are You Married or Happy?

If I was trying to pinpoint the birth of a given relative, I might have found a family or individual headstone in a cemetery.In addition. I may have discovered a number of conflicting references of date of birth in various state and Federal census tabulations. I might even have a birth certificate or a microfiche copy of a birth certificate. There might be a newspaper story about the person’s birth. All of these facts may or may not reflect the same birth date. The challenge becomes what to consider as more reliable than others to state, as evidence, a specific birthdate of a relative.

Something like a headstone may appear to be a source of solid facts. One might assume that a headstone with a name carved into the stone reflects a convincing argument of how the surname was spelled, when the person was born or died and perhaps who was their spouse. While mistakes have been made on head stones, the amount of effort put into creating a marker for an individual’s burial is much more involved than simply transcribing a name on paper. Proof of information on a headstone and its spelling of the surname may provide more weight on a given birth date than what might be found in a Federal census.

One assumes that a relative of or someone who knew the deceased provided correct information to be carved on the headstone. One is also assuming the individual who carved the inscriptions in the headstone completed the job without errors. If an error occurred, family members may decide to ignore the inaccuracy based on the cost of replacing the headstone. If you are looking at a very old headstone, deciphering the lettering and numbers can be challenging. [38]

Having additional documentation such as census records, birth certificates, or newspapers articles about the person may increase the veracity and reliability of information on the headstone. However, the additional information (e.g. birth certificate, newspaper obituary, etc) may cast doubt on the date chiseled on the tomb stone. Ultimately a decision is made, perhaps couched in terms of the probability on the vital statistics found on the headstone.

It is not a fool proof method. I may still have missed the target on establishing the reliability or trustworthiness of information associated with many statements found in the family stories. Hopefully my level of success is much better than a professional baseball player’s batting average.

Sources

Feature Image: An amalgam of stock photographs about facts and evidence, the sources of the original images are found at: Division of Property and Evidence, Caldwell Police, City of Caldwell, https://www.cityofcaldwell.org/departments/caldwell-police/divisions/evidence ; Electronic Evidence and Opinion No. 19, 7 Jul 2020, Digital evidence, European Committee on Legal Co-operation, https://www.coe.int/en/web/cdcj/digital-evidence/-/asset_publisher/7dbCE86mCocc/content/belarus-gender-equality-and-justice?; and Fact or opinion?, ChangeFactory, https://www.changefactory.com.au/our-thinking/articles/fact-or-opinion/

[1] Evaluate the Evidence, FamilySearch Wiki, This page was last edited on 30 April 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Evaluate_the_Evidence

[2] Alternative Facts, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 1 November 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alternative_facts

Susan Martinez-Conde and Stephen L. Macknick, Scientific American, Jan 27, 2017, The Delusion of Alternative Facts, https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/illusion-chasers/the-delusion-of-alternative-facts/

[3] Brian Eno / Chris Frantz / David Byrne / Jerry Harrison / Tina Weymouth, Crosseyed and Painless lyrics © Universal Music Publishing Group, Warner Chappell Music, Inc

Crosseyed and Painless, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 8 April 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crosseyed_and_Painless

Talking Heads – Crosseyed and Painless – Official Original Video 1980, YouTube, https://youtu.be/_Zrkf65GmwE?si=n5i5GNG5BT5mmYTh

Lyrics of Cross Eyed andPainless, Talking Heads , SongFacts, https://www.songfacts.com/lyrics/talking-heads/crosseyed-and-painless

[4] The following are a few examples on ‘what are facts’.

Kevin Mulligan and Fabrice Correia, Facts, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, revised Oct 16, 2020, Edward N. Zalta (ed.) , https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/facts/

Fact, Oxford Dictionary, Google Search of ‘Fact”

Fact, Dictionary.com, https://www.dictionary.com/browse/fact#

Fact, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 9 June 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fact

Morgan Housel, The Difference Between a Statistic and a Fact, Nov 17, 2016, MorganHouse, https://collabfund.com/blog/the-difference-between-a-stat-and-a-fact/

Fact, Cambridge Dictionary, Pages accessed 10 Nov 2023, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/fact#.

Fact, Merriam Webster, Page accessed 10 Nov 2023, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/fact

[5] See quote, for example, from:

The illusion of evidence based medicine, BMJ 16 Mar 2022; 376:702, doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o702

Evidence, Evaluation, and Learning, U.S. Department of State, https://www.state.gov/evidence-evaluation-and-learning/

[6] Here are a number of source references on the concept of ‘evidence’:

Evidence, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 10 November 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evidence

Thomas, Kelley, Evidence, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.), revision Mon Jul 28, 2014, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/evidence/

Victor DiFate, Evidence, International Encyclopedia of Philosphy, https://iep.utm.edu/evidence/

Bryan L. Mulcahy, How to Evaluate Genealogical Evidence, November 15, 2016, Illinois Sons of American Revolution, https://www.illinois-sar.org/uploads/9/7/6/5/97654736/how_to_evaluate_genealogical_evidence.pdf

Evidence Analysis Explained Part III: Evaluating Genealogical Evidence, LegacyTree Genealogists, https://www.legacytree.com/blog/evaluating-genealogical-evidence

Thomas W. Jones, Using Indirect and Negative Evidence to Prove Unrecorded Events, 2021, https://familysearch.brightspotcdn.com/ef/f4/6f1e19da4506a2e177c6d22c1925/jones-indirectandnegative-rt.pdf

Elizabeth Shown Mills, in “QuickLesson 13: Classes of Evidence—Direct, Indirect & Negative,”Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage, Dec 11, 2020 ( https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-13-classes-evidence—direct-indirect-negative

Genealogical Proof Standard, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 13 December 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genealogical_Proof_Standard

Tyler S. Stahle, Understanding the Genealogical Proof Standard, March 9, 2016, https://www.familysearch.org/en/blog/understanding-the-genealogical-proof-standard

Elizabeth Shown Mills, Working with Historical Evidence: Genealogical Principles and Standards, Vol 87, No. 3, Sep 1999, Evidence, A special Issue of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly, Pages 165 – 184, https://www.historicpathways.com/download/workwthhistevidence.pdf.

Genealogical Proof Standard, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 13 December 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genealogical_Proof_Standard

[7] Edward Hallett Carr, What is History?, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1962. Page 23

See also: Kenneth Andres, Analysis of E. H. Carr’s “The Historian and His Facts”, 16 Sep 2016, Medium, https://medium.com/@kennethandres/analysis-of-e-h-carrs-the-historian-and-his-facts-d59e7ac687ee

[8] Ibid, Page 34

[9] ” “the historian is engaged on a continuous process of moulding his facts to his interpretation and his interpretation to his facts. It is impossible to assign primacy to one over the other”. Edward Hallett Carr, What is History?, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1962. Page 34

[10] Elizabeth Shown Mills, Working with Historical Evidence: Genealogical Principles and Standards, Vol 87, No. 3, Sep 1999, Evidence, A special Issue of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly, Pages 165 – 166, https://www.historicpathways.com/download/workwthhistevidence.pdf

[11] This is a quote that was originally in Robert J. Sampson, Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 384. I found it in: Thomas W. Jones, Perils of Source Snobbery, OnBoard , Newsletter of the Board of Certified Genealogists, 18 (May 2012),9–10, 15 https://bcgcertification.org/skillbuilding-perils-of-source-snobbery

[12] This is a blown up portion of an old paper pamphlet that was used to record family births, deaths and marriages were part of the artifacts of Harold Griffis. The pamphlet originally was used to document the births, marriages and deaths of Sperber family members. It appears that the pamphlet in time came into the possession of Rose’s youngest sister, Ida Sperber. The names of Harold and Evelyn and their first three children were then added to the bottom of the list of the Sperber family. On another page, the birth dates, marriages and deaths of maternal relatives of Evelyn Griffis, The Platts family, were also added to the pamphlet. It became a living written family testament of vital statistics for the Sperber, Platts, and Griffis families.

Births of Sperber Family Members

A closer look at the change of Rose’s birth year suggests that it was originally written as ‘1855’, which would have accurately reported her birth year as stated by her mother Sophia Sperber in another document. Her mother Sophie was married in 1857. The birth year on this document was probably revised to hide the fact that Rose was born out of wedlock.

[13] Griffis, Jim, Daniel Griffis – Captured, Imprisoned, & Perished, March 13, 2021, Griffis Family: Selected Stories from the Past, Blog

[14] Griffis, Jim, The Art of Translation and Discovery, July 4, 2023 Griffis Family: Selected Stories from the Past, Blog

[15] Griffis, Jim, Griff(is)(in)(ith)(iths)(es)(in)(ins)(ing) Surname and American Genealogies: Part One, February 17, 2022, Griffis Family: Selected Stories from the Past, Blog

[16] Stefani Evans, CG, “Evidence Correlation,” OnBoard 18 (September 2012), Newsletter of the Board of Certified Genealogists, https://bcgcertification.org/skillbuilding-evidence-correlation/

“Genealogists test their evidence by comparing and contrasting evidence items. They use such correlation to discover parallels, patterns and inconsistencies, including points at which evidence items agree, conflict or both. “

Board for Certification of Genealogists, Genealogy Standards Nashville: Turner Publishing Co., 2021

Melissa A. Johnson, The Importance of Genealogical Analysis and Correlation, April 2015, INGS Monthly, National Genealogical Society, https://www.ngsgenealogy.org/wp-content/uploads/Complimentary-NGS-Monthly-Articles/NGS-Monthly-Johnson-Analysis-Correlation-Apr2015.pdf

Thomas W. Jones, Assessing Genealogical Sources—Part 1, Jan 25, 2021, Genealogical Publishing, https://genealogical.com/2021/01/25/assessing-genealogical-sources-part-1/

How To Evaluate Sources For Confidence In Your Genealogy Research, Sep 28, 2023, https://www.heritagediscovered.com/blog/genealogy-brick-wall-how-to-evaluate-sources

[17] Genealogical Proof Standard, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 11 November 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genealogical_Proof_Standard

The Genealogical Proof Standard – International Institute, This page was last edited on 27 April 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/The_Genealogical_Proof_Standard_-_International_Institute

Stahle, Tyler S., Understanding the Genealogical Proof Standard, 9 Mar 2016, FamilySearch Blog, https://www.familysearch.org/en/blog/understanding-the-genealogical-proof-standard

Genealogical Proof Standard, This page was last edited on 30 April 2023, FamilySearch Wiki, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Genealogical_Proof_Standard

Genealogical Proof Standard (GS), Board for Certification of Genealogists, https://bcgcertification.org/ethics-standards#genealogical-proof-standard-gps

[18] Evidence, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 10 November 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evidence

Thomas, Kelley, Evidence, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.), revision Mon Jul 28, 2014, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/evidence/

Victor DiFate, Evidence, International Encyclopedia of Philosphy, https://iep.utm.edu/evidence/

Bryan L. Mulcahy, How to Evaluate Genealogical Evidence, November 15, 2016, Illinois Sons of American Revolution, https://www.illinois-sar.org/uploads/9/7/6/5/97654736/how_to_evaluate_genealogical_evidence.pdf

Evidence Analysis Explained: Digging Into Genealogical Sources, LegacyTree Genealogists, https://www.legacytree.com/blog/evidence-analysis-sources

Evidence Analysis Explained Part II: Evaluating Genealogy Information, LegacyTree Genealogists, https://www.legacytree.com/blog/evaluating-genealogy-information

Evidence Analysis Explained Part III: Evaluating Genealogical Evidence, LegacyTree Genealogists, https://www.legacytree.com/blog/evaluating-genealogical-evidence

Thomas W. Jones, Using Indirect and Negative Evidence to Prove Unrecorded Events, 2021, https://familysearch.brightspotcdn.com/ef/f4/6f1e19da4506a2e177c6d22c1925/jones-indirectandnegative-rt.pdf

Elizabeth Shown Mills, in “QuickLesson 13: Classes of Evidence—Direct, Indirect & Negative,”Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage, Dec 11, 2020 ( https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-13-classes-evidence—direct-indirect-negative

Elizabeth Shown Mills, Evidence! Citation & Analysis for the Family Historian (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1997),

Elizabeth Shown Mills, Evidence Explained: Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace, 2nd ed. (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing, 2009)

Elizabeth Mills, “Working with Historical Evidence: Genealogical Principles and Standards,” in Evidence: A Special Issue of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly, NGS Quarterly 87 (September 1999): 165–84

Elizabeth Mills, Helen F. M. Leary, and Christine Rose, “Evidence Analysis: Definitions, Principles, and Practices,” in Virginia: Where a Nation Began, National Genealogical Society 1999 Conference in the States Program Syllabus (Arlington: NGS, 1999), 41–48

Elizabeth Mills and Donn Devine, ”Evidence Analysis,” in Mills, ed., Professional Genealogy: A Manual for Researchers, Writers, Editors, Lecturers, and Librarians (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2001): 327–42

Genealogical Proof Standard, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 13 December 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genealogical_Proof_Standard

Tyler S. Stahle, Understanding the Genealogical Proof Standard, March 9, 2016, https://www.familysearch.org/en/blog/understanding-the-genealogical-proof-standard

Elizabeth Shown Mills, Working with Historical Evidence: Genealogical Principles and Standards, Vol 87, No. 3, Sep 1999, Evidence, A special Issue of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly, Pages 165 – 184, https://www.historicpathways.com/download/workwthhistevidence.pdf.

Diane Haddad, 3 Tips to Analyze Genealogical Evidence , Family Tree Magazine, https://familytreemagazine.com/general-genealogy/3-tips-to-analyze-genealogy-evidence/

Genealogical Proof Standard, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 13 December 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genealogical_Proof_Standard

[19] Primary sources are documents, images or artifacts that provide first hand testimony or direct evidence concerning an historical topic. They are original documents created or experienced contemporaneously with the event being researched. They also enable researchers to get as close as possible to what actually happened during an historical event or time period.

Examples of primary sources include:

- Letters, diaries, scrapbooks and journals;

- Images or artifacts (e.g. clothing, furniture, material objects);

- Photographs, audio recordings, video recordings, films

- Government documents (e.g. census data, laws, regulations);

- Interviews and oral histories;

- Records of organizations

- Autobiographies and memoirs

- Printed ephemera (e.g. admission ticket, graduation ceremonies, a play, a movie, advertisements, etc.)

- Historical newspapers and magazines; and

- Works of literature or art created at the time.

Secondary sources are works that analyze, assess or interpret an historical event, era, or phenomenon, generally utilizing primary sources to do so. Secondary sources are generally written after the events that are being researched. However, if an individual wrote about events that he or she experienced first-hand many years after that event occurred, it is still considered a primary source because it is a direct account from a participant or witness to the event.

Examples of secondary sources include:

- Historiographical works and textbooks;

- Articles and book reviews;

- Biographies and autobiographies; Newspaper editorials, journal articles, speeches, reviews, and research essays;

- Documentaries and films about historical events; and

- Encyclopedias and reference books about specific topics.

[20] Elizabeth Mills, “Working with Historical Evidence: Genealogical Principles and Standards,” in Evidence: A Special Issue of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly, NGS Quarterly 87 (September 1999): 171-172 , https://www.historicpathways.com/download/workwthhistevidence.pdf

[21] Elizabeth Mills, “Working with Historical Evidence: Genealogical Principles and Standards,” in Evidence: A Special Issue of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly, NGS Quarterly 87 (September 1999): 169 , https://www.historicpathways.com/download/workwthhistevidence.pdf

[22] The original source of the Evidence Analysis Process Map can be found in Mills, Elizabeth Shown. “Working with Historical Evidence: Genealogical Principles and Standards.” Evidence: A Special Issue of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly 87 (September 1999): 165–84.

See also: Elizabeth Shown Mills, “QuickLesson 17: The Evidence Analysis Process Model,” Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-17-evidence-analysis-process-map

Mills, Elizabeth Shown , A Template for Evaluating Evidence, Genealogical Computing 24 (April–June 2004) [extracted from unpaginated archived copy, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com/learn/library/article.aspx?article=9270 : 16 October 2011) also https://www.historicpathways.com/download/templateforee.pdf

The original map:

See: Seaver, Randy, Changes to the Evidence Analysis Process Map in GPS, 6 May 2013, Genea-Musings, https://www.geneamusings.com/2013/05/changes-to-evidence-analysis-process-map.html

[23] Evidence Analysis Explained: Digging Into Genealogical Sources, LegacyTree Genealogists, https://www.legacytree.com/blog/evidence-analysis-sources

Evidence Analysis Explained Part II: Evaluating Genealogy Information, LegacyTree Genealogists, https://www.legacytree.com/blog/evaluating-genealogy-information

Evidence Analysis Explained Part III: Evaluating Genealogical Evidence, LegacyTree Genealogists, https://www.legacytree.com/blog/evaluating-genealogical-evidence

[24] There are three general sources of information: original , derivative and narrative.

- Original: The actual record, document, or object;

- Derivative: A record or object created at a later date which reports the same information as the original source.

- Narrative: An original narrative with conclusions that is a product of original and derivative source research.

Evidence Analysis Explained: Digging Into Genealogical Sources, LegacyTree Genealogists, https://www.legacytree.com/blog/evidence-analysis-sources

[25] This category is subdivided three ways:

- Primary: Information was recorded at or near the time of the event by someone wo had first hand knowledge.

- Secondary: Information was recordsed after the time of the event or by someone who did not have director or first hand knowedge.

- Undetermined: Insufficient data is provided to accurately identify the informant.

Evidence Analysis Explained Part II: Evaluating Genealogy Information, LegacyTree Genealogists, https://www.legacytree.com/blog/evaluating-genealogy-information

[26] “The purpose of genealogy is to reach defensible conclusions about our ancestors. This is done through proper analysis of the evidence. When we consider the sources, the information, and the evidence we can reach conclusions which are reliable.“

“There are three types of evidence: Direct, Indirect, and Negative.

- Direct: Conclusions about facts or information that were drawn from explicit sources appear to need no additional supporting documentation .

- Indirect: Conclusions about facts or information that were drawn from mutliple sources because no single source directly answers the research question.

- Negative: Conclusions about facts or information that were drawn because evidence fails to exist.

Evidence Analysis Explained Part III: Evaluating Genealogical Evidence, LegacyTree Genealogists, https://www.legacytree.com/blog/evaluating-genealogical-evidence

[27] Elizabeth Shown Mills, Working with Historical Evidence: Genealogical Principles and Standards, Vol 87, No. 3, Sep 1999, Evidence, A special Issue of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly, Page 181, https://www.historicpathways.com/download/workwthhistevidence.pdf

[28] My ordinal scale of certainty is similar to a three tier scale in Norman Ingham’s discussion of the processes involved in genealogical analysis:

- (Reasonable) certainty, used at the “proof” stage—a term signifying a convincing degree that is comparable to the math/physics concept verification.

- Possibility, used at the “speculation” stage—a term comparable to the math/physics concepts intuition and guess.

- Probability, used at the “hypothesis” stage—a term comparable to the math/physics concepts proposal and conjecture.

Inghan, Norman W. , “Some Thoughts about Evidence and Proof in Genealogy,” The American Genealogist 72 (July–October 1997): 380–85

[29] Nathaniel Griffis, 1810 U.S. Census, New York, Albany, Watervliet, Line 20, Page 1312

[30] Nathaniel Griffes, 1820 U.S. Census, New York, Schenectady, Niskayuna, Line 16, Page 577

[31] National Griffes, 1840 U.S. Census, New York, Schenectady, Niskayuna, Line 15, Page 353

[32] Nathaniel Griffis, Albany County Militia (Land Bounty Rights) – Sixth Regiment Regiment, New York in the Revolution as Colony and State, Vol. I: The Militia, Compillation of Documents and Records from the Office of the State Comptroller, Albany: J.B. Lyon Company, 1904, page 227 See footnote 32 above for image.

[33] Nathaniel Griffes and family were members of the Dutch Reformed Church in Schenectady, New York. The church records indicate that Nathaniel Griffes and his wife Mary Ann Griffes, and Mary Esther Griffes became a members in 30 October 1834. The three are listed again as being received into the church on 1 November 1842. Nathaniel’s son James A. Griffis was received into the church congregation on 6 June 1853. His wife was received by ‘confession’ on 4 June 1869.

[34] Will of Nathaniel Griffes, U.S. Wills and Probate Records, 1659 – 1999, Schenectady Wills, Vol D – E, 1832 – 1845, date of Will 20 May 142, date of Probate 15 Apr 1842, Probate Place Schenectady NY, Image 325 – 327, Pages 386 – 390. See PDF copy of will.

[35] Nathaniel Griffes, Probate Date 15 Apr 1842, Probate Place Schenectady, New York, Inferred Death Date 1842 Letters Test, Vol 0004-0006, 1839-1863, image 68, Page 32, Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Original data: New York County, District and Probate Courts.

[36] Vale Cemetery Memorials for Individuals named Griffes, Find a Grave website, accessed 31 Mar 2022. There are nineteen individuals buried in the cemetery with the surname Griffes.

Griffes Family Members Buried in Vale Cemetery

| Name | Dates | Plot information |

|---|---|---|

| Angelica K. Schermerhorn Griffes | 1847-1930 | Sect H lot 12 |

| Anna R Griffes | 4 Feb 1861 – 6 Nov 1885 | Section M-3 |

| Catherine Nichols Griffes | 18 Feb 1838 – 28 Jan 1890 | Section H |

| Catherine Maria Griffes | unknown – 1841 | |

| Esther Griffes | 1778 – 3 Jun 1848 | |

| James A Griffes | 3 Dec 1839 – 18 Jan 1898 | Section M-3 |

| Jane Viele Griffes | 24 Oct 1832 – 25 Jul 1918 | M-30 |

| Joel Griffes | 10 May 1799 – 24 Oct 1828 | |

| Julia Griffes | 1815 – 1890 | |

| Julia A Griffes | 10 Dec 1838 – 25 Sep 1864 | M-3 |

| Julie Ann Griffes | unknown – 1848 | |

| Maria Griffes | 1817 – 9 Jul 1828 | |

| Mary Whitney Griffes | 1808 – 1877 | |

| Nathaniel Griffes | unknown – 11 May 1956 | H-12 |

| Nathaniel Griffes | 3 Oct 1763 – 3 Mar 1842 | |

| Sally Griffes | unknown – 1819 | |

| Stephen Griffes | 1805 – 1850 | |

| William W Griffes | 29 Oct 1870 – 22 Jul 1872 | |

| William Whitney Griffes | 1835 – 17 Jan 1905 |

[37] Early census records are often difficult to read and appear to have obvious errors. To what degree are these earlier records considered reliable when doing research?, Quora, https://www.quora.com/Early-census-records-are-often-difficult-to-read-and-appear-to-have-obvious-errors-To-what-degree-are-these-earlier-records-considered-reliable-when-doing-research

When evaluating any source, it is always wise to consider how, when, and under what conditions the record was made.

For example, by understanding some of the difficulties encountered by enumerators, it becomes easier to understand why some individuals cannot be found in the census schedules or their indexes.

From the first enumeration in 1790 to the most recent in 2000, the government has experienced difficulties in gathering precise information for a number of reasons. At least one of the problems experienced in extracting information from individuals for the first census continues to vex officials today: there were and still are many people who simply do not trust the government’s motives. Many citizens have worried that their answers to census questions might be used against them, particularly in regards to taxation, military service, and immigration. Some have simply refused to answer enumerators’ questions; others have lied.

https://wiki.rootsweb.com/wiki/index.php/Overview_of_the_U.S._Census

[38] 3 Methods for Reading Hard-to-Read Tombstones, March 7, 2019, Merkle Monuments, https://www.merklemonuments.com/reading-hard-to-read-tombstones ; Karen Miller Bennett, Five Tips for Safely Reading and Photographing Tombstones, Karen’s Chat, Blog, https://karenmillerbennett.com/tombstone/five-tips-for-safely-reading-and-photographing-tombstones/ ; Cemetery Conservators for United Standards, Reading Stones Basics, https://cemeteryconservatorsunitedstandards.org/reading-stones/