This story is a bit different from the other stories of our family’s past. This story and three successive stories focus on how I view and conduct genealogical research and create stories of the past. I thought it would be appropriate to provide some background on how I approach and conduct research on family members and families in the past.

Hopefully these discussions about how I frame genealogical questions and conduct research do not get too deep or boring. I promise more stories about actual relatives will follow. I have so much material to produce these stories. I just hope I have sufficient time to get them out of my head for family members to enjoy. I also hope to get as many old photographs out of boxes for everyone to view and enjoy.

In order to answer the various questions that arise when reconstructing our family’s past, one needs to gather all the possible evidence, vet it for bias and authenticity, understand the larger historical picture presented by these facts and place them into context, and then make logical conclusions on what is a useful premise for a given story.

I am making it sound easy.

It actually takes a lot of digging through physical and digital source material. It also takes a lot of patience, objectivity, tenacity, focus, analysis and luck to find information or facts that appear to document a simple assertion about someone or solve a genealogical question. It then may entail many hours of focused research and analysis to get all those facts and evidence somewhat straight, trustworthy and reliable. The final step is to attempt to package these facts or evidence in a manner that makes them come to life and become an interesting story.

My method and approach to genealogical research is basically a continuous process involved with evaluating historical evidence. What I write today may change based on subsequent discoveries of new facts about my family or alternative information on interpreting existing facts.

Despite having what one might think is a well established and documented outline of family facts, attempting to write about a particular subject often reveals holes in my research. The ‘devil is in the details‘. This motivates me to try to clean up and make my earlier research more reliable and trustworthy. This usually leads me down more “rabbit holes” of research. [1]

My Goals as an Amateur Genealogist and Family Historian

According to the Board for Certification of Genealogists (BCG), “All genealogists strive to reconstruct family histories or achieve genealogical goals that reflect historical reality as closely as possible.” [2] The BCG is a prominent organization in the field of genealogy that plays a crucial role in maintaining professional standards and credibility within the industry. [3]

The BCG statement above has been referenced by many professional and amateur genealogists and family historians. [4] This is a sound principle and standard to guide one’s research efforts. It is a central tenet that I follow. Whether all genealogists strive to abide by this standard is an open question.

Similar to other genealogists, I have several key objectives when conducting research. The following four come to mind:

- A major goal is to trace, with the greatest accuracy, family lineages as far back in time as possible. This involves identifying direct ancestors through multiple generations and establishing kinship family trees among those ancestors.

- Documenting personal information and histories on specific individual family members is a major goal.

- Beyond names, dates, and family relationships, another goal is to discover personal stories, develop historical context, and interesting details about ancestors’ lives. This brings family history to life and creates a richer narrative.

- I also am fortunate to have inherited a large body of photographs of descendants that lived within the last 200 years and material items that that were made or belonged to family descendants. A major goal is to share information about these photogtraphs and historical items to family members.and other interested parties.

My General Perspective on Genealogy and Family History

My views of genealogy and family history and research questions closely resemble the perspectives of an historian. I have the desire to place the information I may have on a given individual, family and kinship network in the historical context of a community or geographical area. I also have an interest in establishing plausible narratives of the movement of ancestors from one place to another.

There are perhaps a number of general influences on how I conduct my research and write my stories.. Three overarching outlooks are:

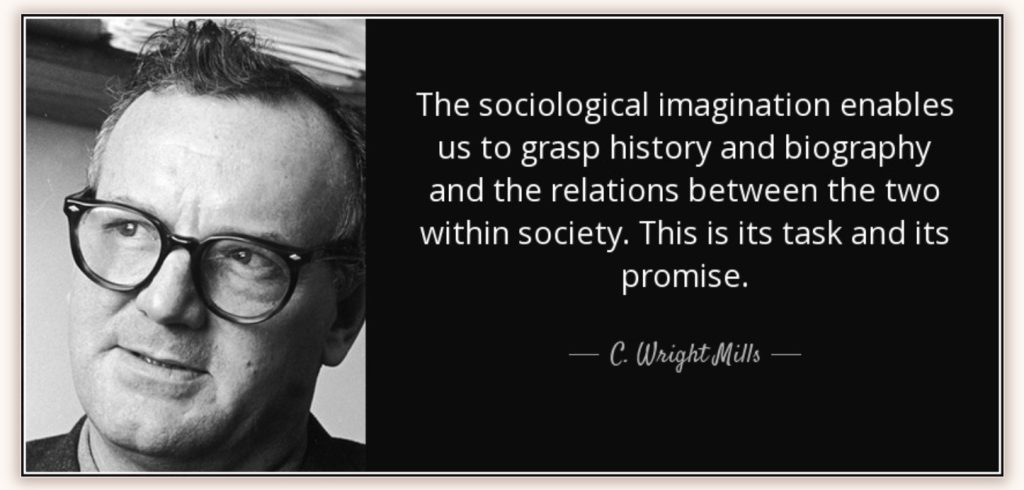

- My general perspective of traditional genealogical and family history research partly requires ‘looking through the lens’ of what C. Wright Mills called a ‘sociological imagination‘.

- I view traditional genealogy as a form of micro-history and social history. [5]

- I view an interrelatedness between traditional and genetic genealogy research that can create a more comprehensive and accurate picture of certain facets of our family history and kinship networks.

Sociological Imagination

A ‘sociological imagination‘ is a critical mindset for understanding the relationships between individuals and society and orienting genealogical research. C. Wright Mills introduced the concept of the sociological imagination in his 1959 book “The Sociological Imagination“. For genealogy and family history, it means putting genealogical evidence in context with larger social and cultural influences. [6]

In the context of genealogical research, the sociological imagination is a way of thinking of how to connect personal information of ancestors’ to historical information related to larger social structures, historical forces, and public issues at the time of their lives. Mills saw the sociological imagination as a critical tool for understanding the complex relationships between individuals and society.

Mills argued that neither individual lives nor the history of society can be understood without understanding both. It requires looking beyond personal circumstances and facts associated with family members in the past and considering the broader historical, cultural and social contexts that shaped their individual lives.

This perspective enables me to step back from looking at family members’ immediate personal experiences and facts and see how they connect to wider societal patterns and historical trends. It allows me to understand how biography and history intersect – how an ancestor’s personal experiences and related facts were shaped by their place in history and society.

Similar to Mills’ perspective, genealogists and historians in the past sixty-five years have also underscored that “one of the fundamental tenets of genealogy today is that we cannot trace our ancestors in isolation of their community”. [7]

‘History from Below’ – Microhistory and a Social Historical Perspective

The work and methods used by social historians have given me insight on how to broaden my approach to conduct genealogical research as well as craft family stories. They have revealed novel sources of gathering genealogical information and weaving that information in with traditional historical narratives at the community, regional and national levels. Depending on the subject of their research, I have also been able to incorporate their results in my writing.

In my view, similar to many genealogists and social historians, genealogy is the history of the common person. Some of our families may have had a “great person” in their past or have a “prominent family” in one of the branches of a family tree. These individuals or families are amply documented by facts and evidence from a variety of historical sources. They may even be memorialized by historians, newsprint or family narratives. However, most of our ancestors led common lives. Many of the vital facts about their lives are limited. Much of their lives were not directly documented or the sources of those documented facts were destroyed or remain hidden. [8]

“(T)he majority of … people led quiet, blameless lives and left very few traces, and almost all sources of biography come with collision with authorities. This tends to be for purposes of registration (birth, marriage, death, census, taxes, poor relief, etc) or for legal reasons, whether criminal… or civil. “ [9]

Most of our family ancestors were common people whose lives were not directly documented throughout stages of their lives. One of the inherent challenges in genealogical research is filling in the gaps, linking the few facts we discover about an ancestor or family through various other sources of evidence.

“History from the bottom up” is a historical approach that focuses on the lives of ordinary people and how they shape the past. It can be applied to a variety of scales, including: the individual level, family, local community, occupations and larger structural levels. Its methodological approach begins with small social groups, specific topics, and short time periods before expanding to broader contexts. It incorporates interdisciplinary methods from economics, statistics, and other social sciences. It challenges traditional top-down narratives by revealing how ordinary people actively shaped historical events. [10]

American social historians in the 1970s shifted away from studying elites and “great men” to examining the lives and experiences of ordinary people and marginalized groups. This “history from below” or “social history” approach aimed to reconstruct the perspectives of common people throughout history. The new social historians drew on methods and theories from other social sciences (such as sociology, demography, economics, anthropology, and geography) and genealogy. [11]

Social historians employed a variety of research methods that drew heavily from the social sciences. Quantitative methods became very popular among social historians in the 1960s-1970s. Quantification was seen as indispensable for doing “history from the bottom up” and understanding the local social structural influences on the lives of ordinary people. [12]

The field of social history later embraced greater ‘methodological pluralism’. Quantitative approaches continued but were supplemented by a diverse range of qualitative methods. “Methodological pluralism in history” refers to the idea that historians should not rely on just one type of source or method to study the past, but instead should utilize a variety of approaches, including quantitative data, qualitative interviews, archival documents, visual analysis, and oral histories, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of historical events and perspectives from different angles. It advocates for the use of multiple methodologies to avoid bias and provide a richer historical narrative. The goal was an integrative social history combining the best of both quantitative and qualitative approaches. [13]

Their research innovations were wedding historical individual level tracing practices associated with genealogical research and empirical approaches to examining community and regional population patterns. Part of their approach drew on the same sources and methods as those used by genealogists. The difference is the “the questions asked of the material”. [14]

Historians provide genealogists with many valuable perspectives that help to put families into clearer historical focus. Social historians examine broad social, economic, and demographic structures and long-term historical processes rather than specific events or individuals or families. Social historians look at factors like family and kinship systems, class structure, migration, ethnicity, patterns of work and leisure, and urbanization and industrialization.

Approaches utilized by social historians have increasingly documented the benefits of genealogy as a source of historical information and research methods associated with records and archival-research skills. Conversely, professional genealogists have underscored the need to place genealogical lineages and families into a broader social and historical context.

“The archival record is merely an artifact, a momentary product of a given act in time and space, and not a reflection of the context of life itself. It should be used as a window through which the broader events of life may be visualized and reconstructed.” [15]

As a professional genealogist Elizabeth Mills indicated, genealogy is micro-history and historical biography.

“Genealogists pluck individual people out of the typically nameless, faceless masses whom historians write about in broad terms. One by one, we breathe life back into people from the past. We piece together again the scattered fragments of their lives. We put them into their historical, social, and economic settings. Then we use our research and analytical skills to stitch these individuals together into the distinctive patchwork quilt that tells each family’s story. “ [16]

In the mid 1970s, Samuel Hays, an historian, urged genealogists to broaden the context of their family histories to make them more meaningful inquiries, to go beyond brief thumbnail biographies concerned with demographic facts of birth, death, occupation and family trees. [17]

Use of Genetic Genealogical Methods

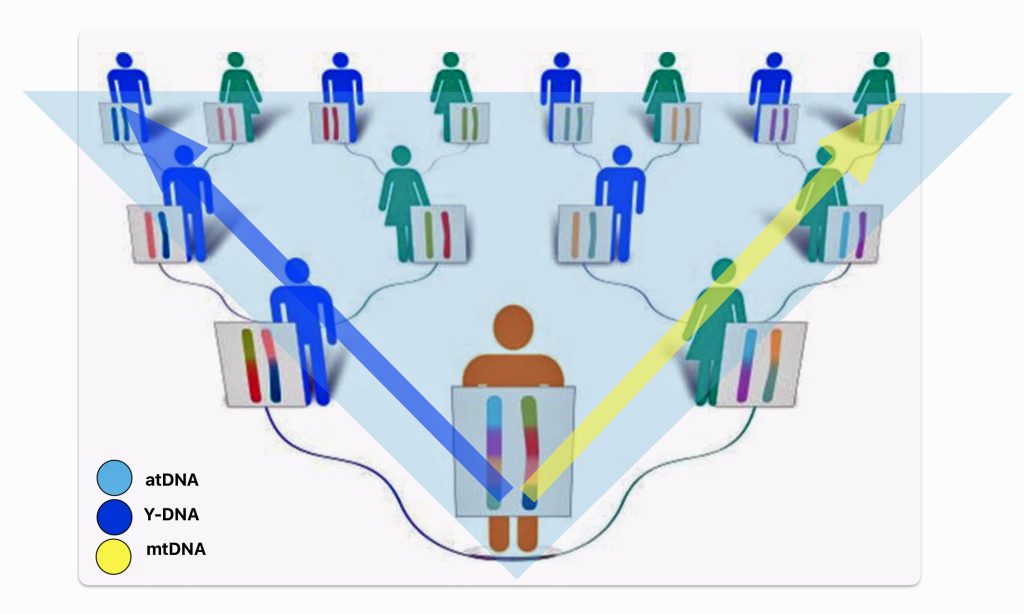

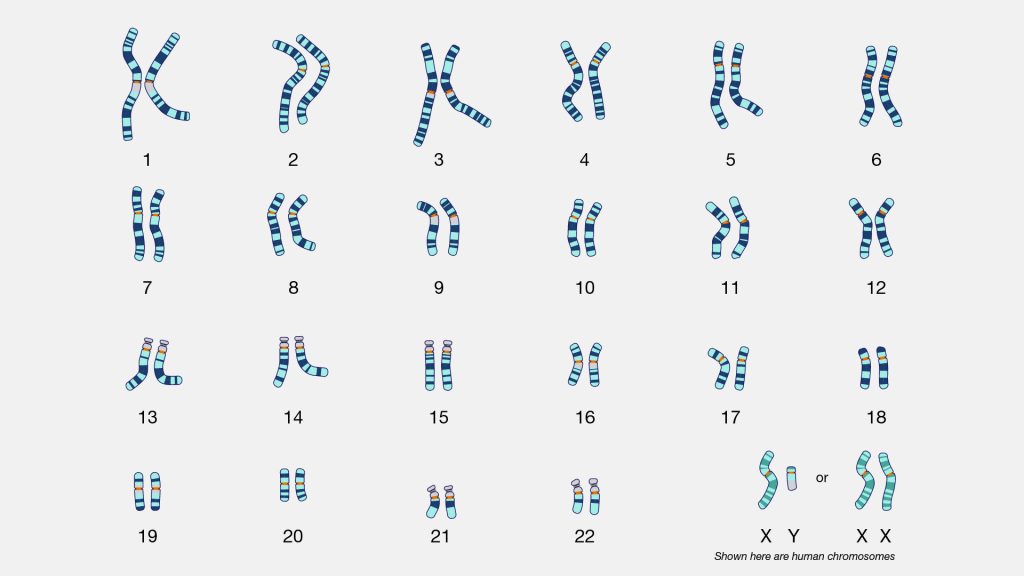

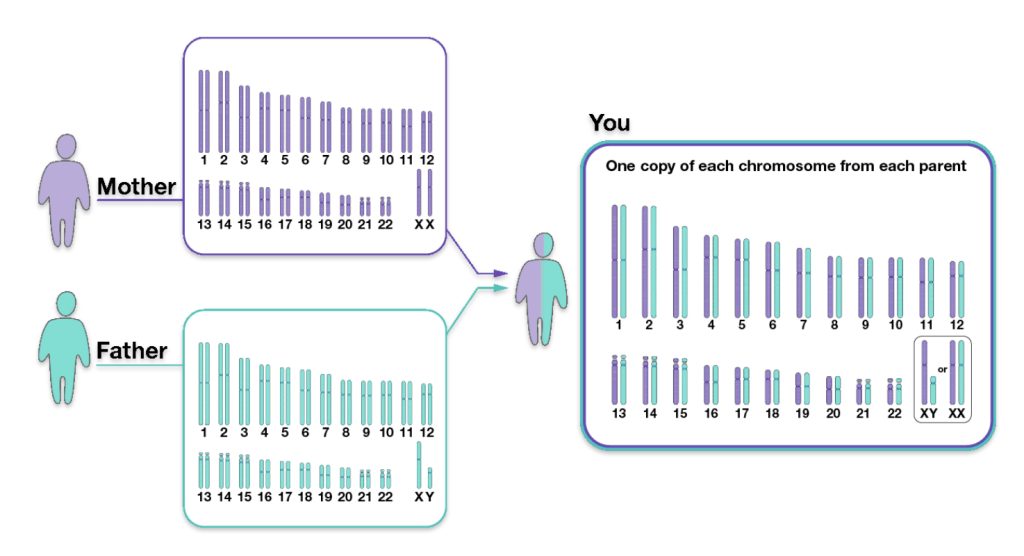

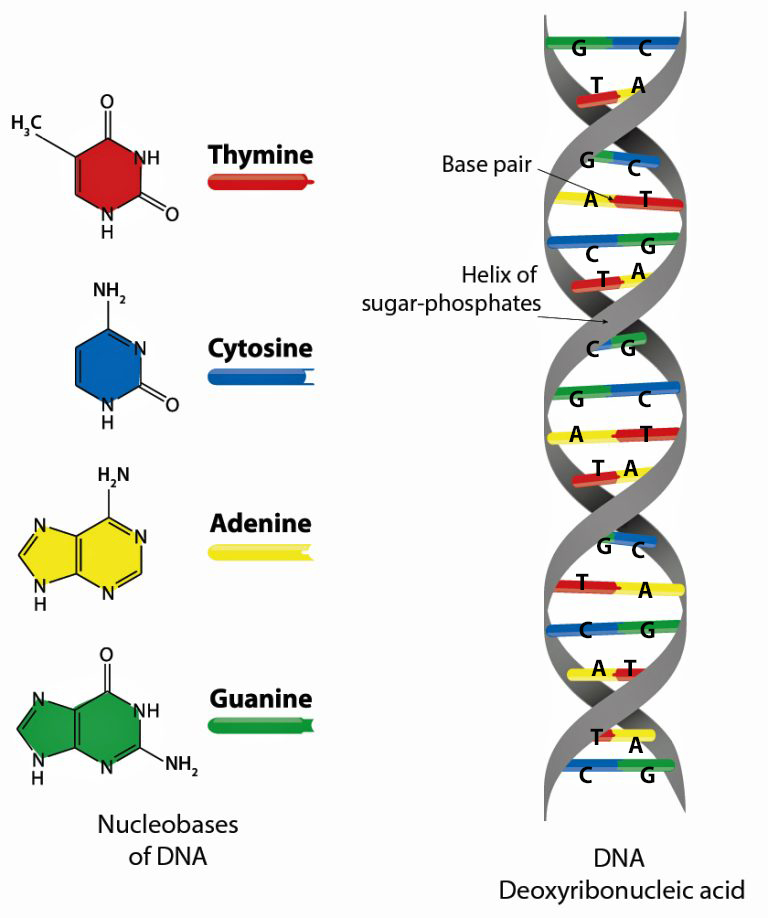

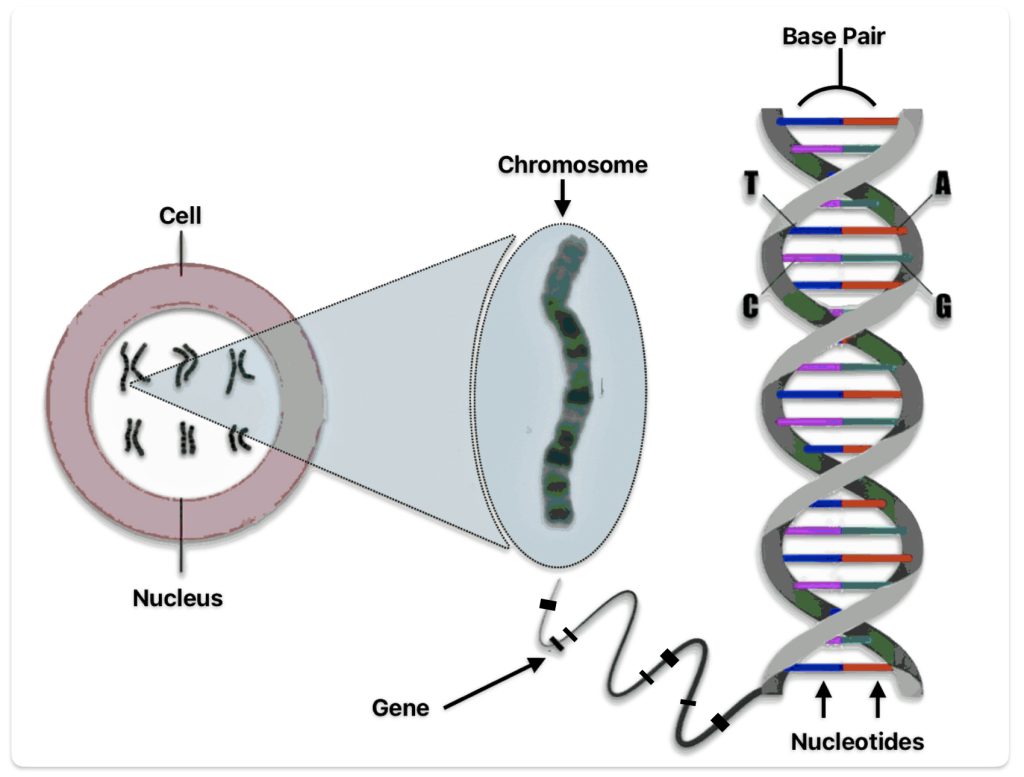

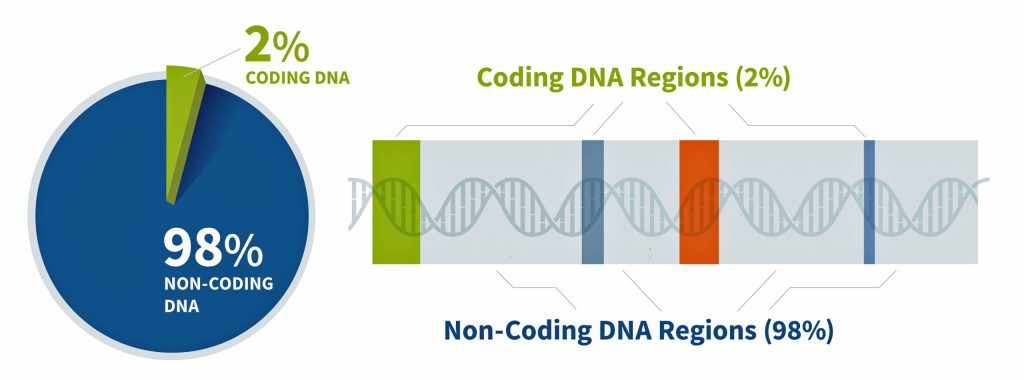

Traditional genealogy and genetic genealogy are complementary approaches that work together to create a more complete picture of a family history. DNA testing can enhance traditional genealogical research in several key ways through autosomal DNA (atDNA), Y-DNA, and Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) testing and analysis. [18]

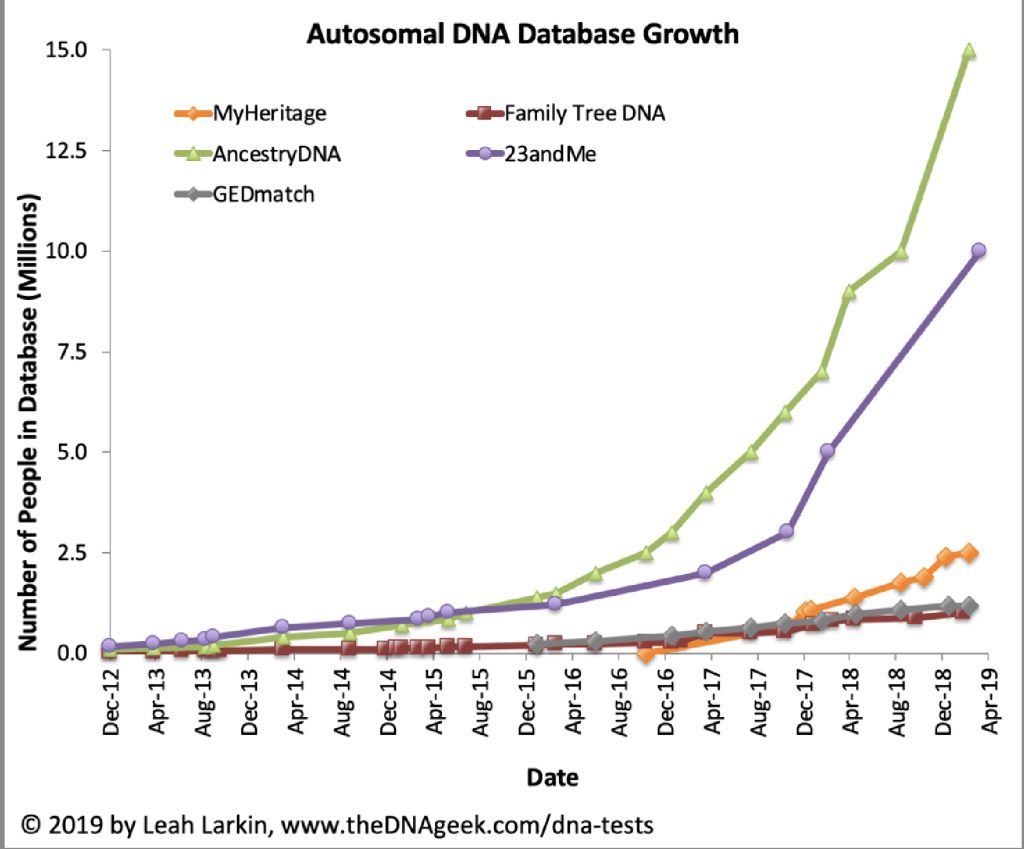

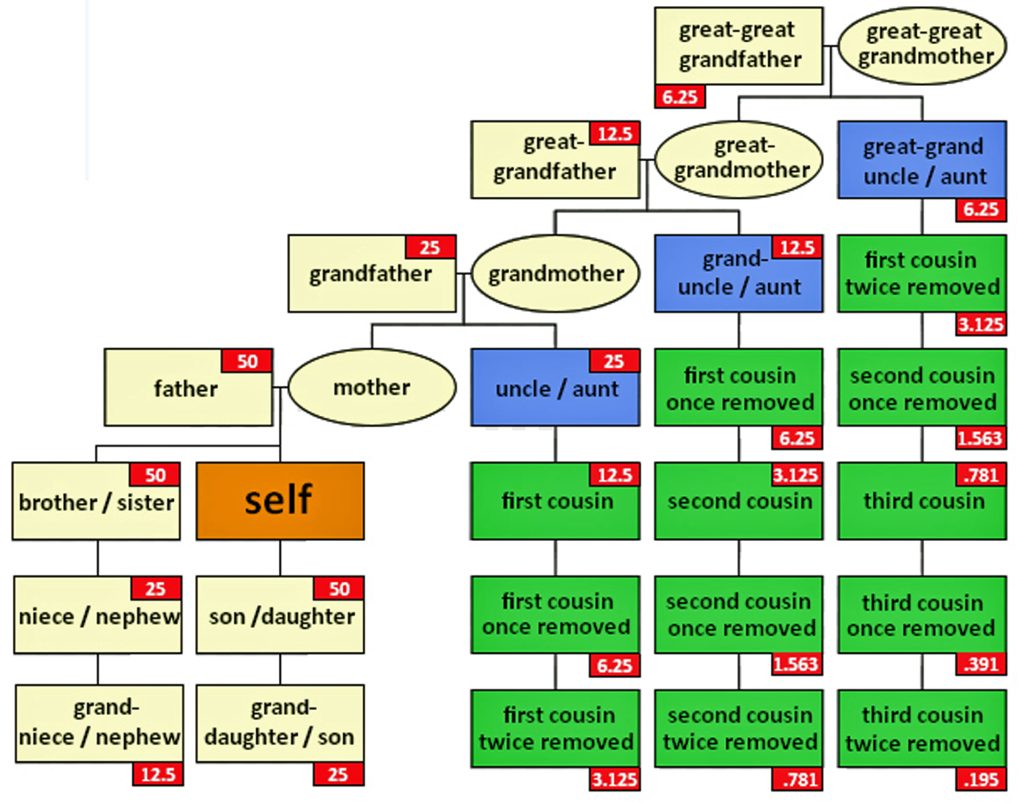

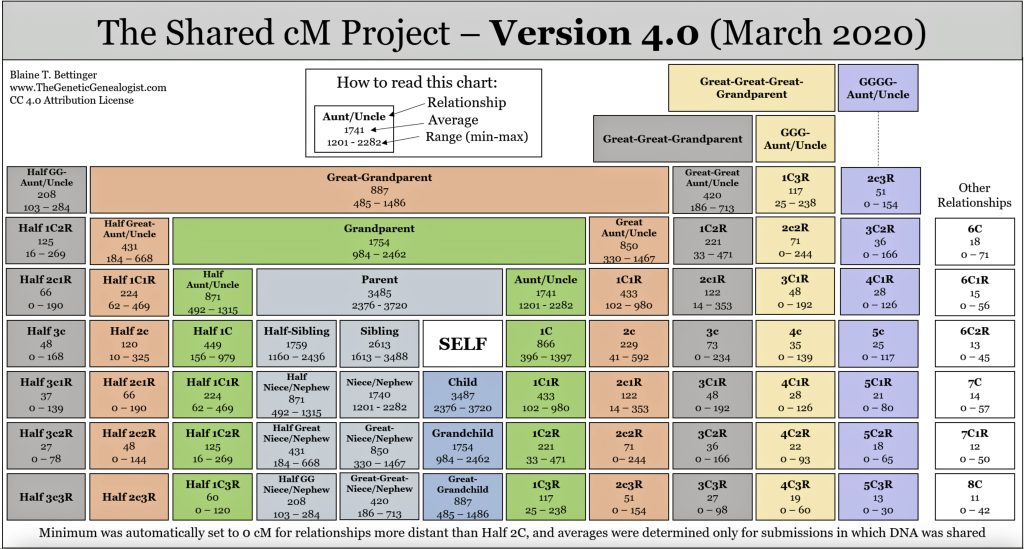

Autosomal DNA testing provides connections to relatives across all ancestral lines and have aided my efforts to identify relationships up to approximately five generations back. Y-DNA and mtDNA testing complement traditional genealogical research by providing distinct insights beyond the traditional paper trail associated with traditional genealogy into paternal and maternal lineages respectively.

DNA testing is often used in genealogical research simply to confirm or refute traditional paper evidence. However, there are other advantages in utilizing DNA evidence. Rob Spencer, a genetic genealogist that favors a macroscopic view of revealing broad genetic patterns from genetic data, points our attention to other utilities of DNA research in genealogy. DNA testing provides a broader approach in which DNA connects to previously unknown people, living or dead, who may have other evidence relevant to our ancestry. DNA can ‘jump over information gaps’ in a lineage to connect to earlier ancestors and geographic locations.

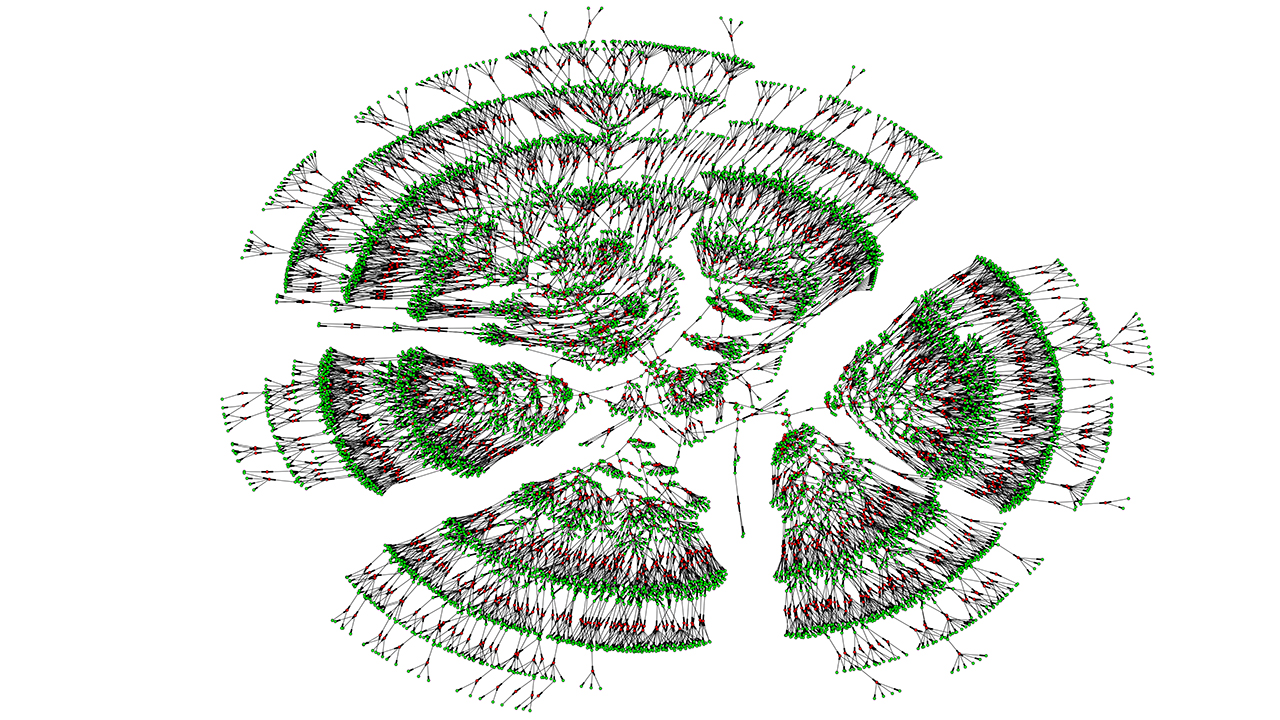

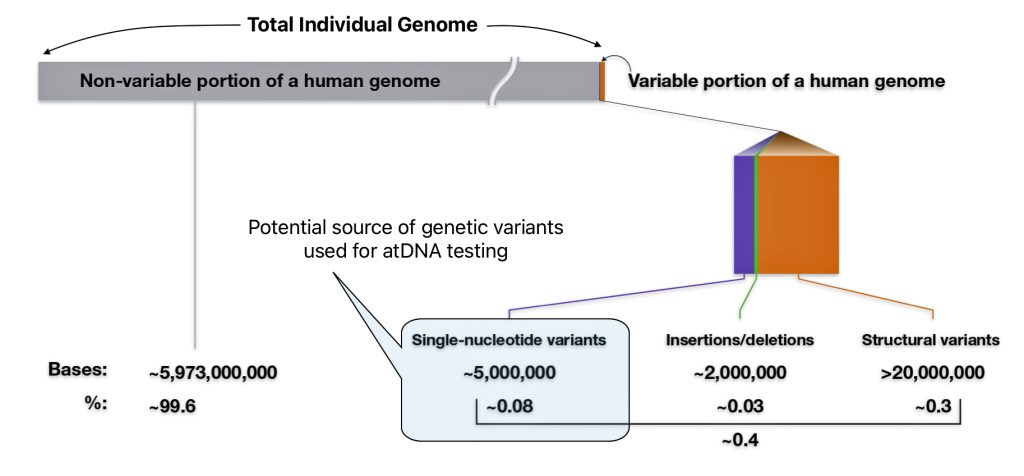

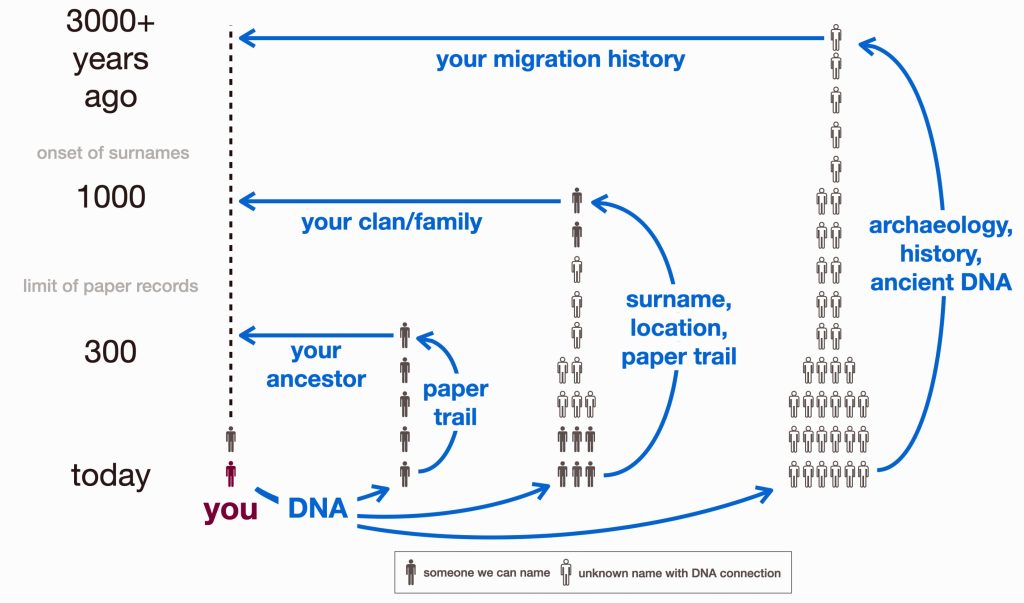

Rob Spencer provides a graphic portrayal of tracing one’s ancestor’s based on three levels of research (illustration one). The first level deals with traditional genealogical ‘paper trails’ and research which can provide information in the recent past. Beyond 300 years, the paper trail tends to thin out and evaporate. [19]

Illustration One: Three Levels of Genealogical Research

For example, within the first level of research in Spencer’s diagram, autosomal and Y-DNA can complement our efforts in documenting genealogy in the past six to ten generations. The results of Short Tandem Repeat (STR) DNA tests connected to other DNA testers can help build out family trees through information they might have on other family members. These DNA tests can help build out family tree where our paper records are limited. I have also been able to decipher the origins of the Griffis surname through traditional genealogy and Y DNA analysis. [20]

The use of Y-DNA research can help trace unknown ancestors prior to the use of surnames, pinpoint possible regional areas where ancestors lived, provide possible links to the recent past and link seemingly non-related individuals in the present to your genetic lineage. This is the second level in Spencer’s chart.

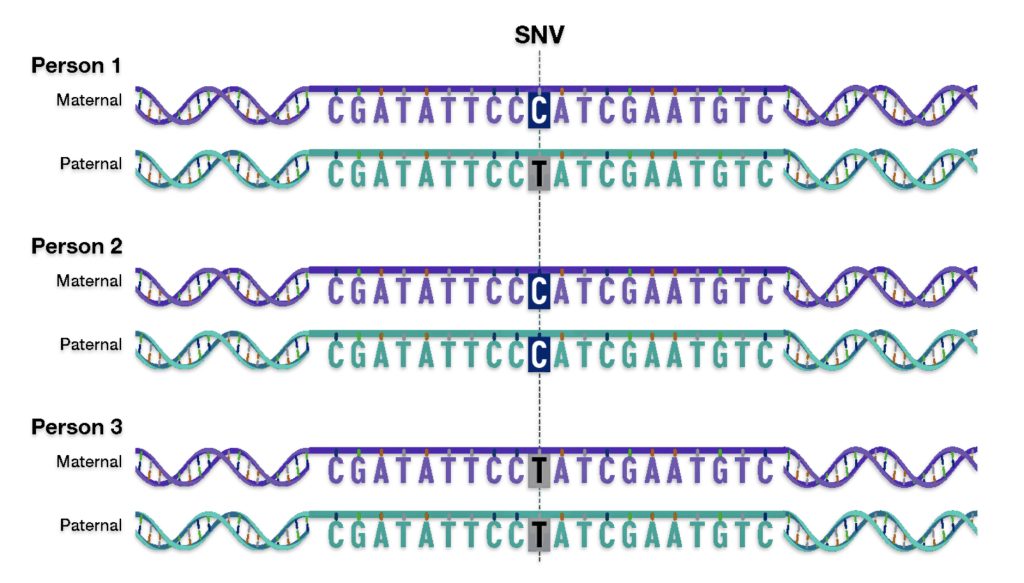

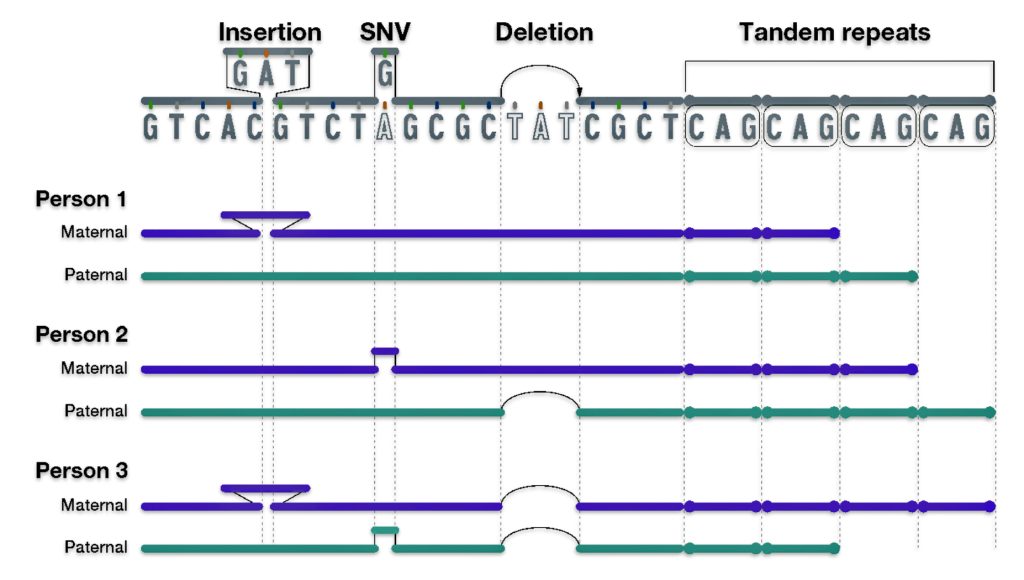

Y-SNP (Single nucleotide Single Nucleotide Polymorphism) DNA testing and research, coupled with archaeological and paleo-genomic discoveries can also shed light on macro level connections to migration patterns that can be associated with genetic ancestors.

Y-STR and Y-SNP testing have distinct characteristics that make them suitable for different types of genetic analysis, as reflected in the following table.

Comparison of STRs and SNPs

| Feature | STRs | SNPs |

|---|---|---|

| Mutation Rate | Higher | Lower |

| Stability | Less stable | Very stable |

| Reversibility | Can reverse | Rarely reverse |

| Time Scale | Recent ancestry ~ 1,500 years ago | Ancient ancestry ~ 50,000 years ago |

Using various types of DNA tests can increase the success of discovering additional genealogical information.

- Finding genealogical matches with different surnames. Since the Griff(is)(es)(ith) surname was a Welsh surname, the use of surnames did not become firmly established in certain parts of Wales until the late 1700’s to mid 1800’s. The use of Y-STR and Y-SNP DNA tests increases the chances of finding genetically related ancestors with different surnames in Europe.

- Finding genealogical matches currently confirmed through traditional research. The Y-STR DNA test can find matches with individuals that have already been documented in my family tree. Additional clues to male family members that are descendants of William Griffis can be found.

- Finding genealogical matches that point to Wales. Regardless of surname, genetic descendants can potentially be located in Wales and in Europe in general.

- Identify unknown ancestors and lineages in timelines where no records exist. The DNA test could narrow the search of male ancestors to specific genetic Y-DNA lines and identify the branching in these paternal lines.

- Identify ancient groups and migration patterns associated with the genertic paternal line. The Y-SNP and Y-STR DNA tests are able to obtain information on the patrilineal line at a higher, anthropological level and gain insights into the population level migratory patterns and that can be correlated with of the lineage.

Genealogy and Family History

I oftentimes use terms ‘family history‘ and ‘genealogy‘ interchangeably. Granted, the two terms and orientations do have subtle differences or priorities. Despite those differences, they are inextricably connected in most of our family storytelling. [21]

I believe the subtle differences between the two terms are more apparent when genetic genealogical research is introduced. Genealogical time is stretched beyond the time span of 300 years that is usually associated with traditional genealogical research, The ability to provide a family history of a given person or family diminishes and eventually vanishes as we go back in time. Traditional records evaporate after a number of generations and are replaced with genetic mutations from DNA tests or paleo artifacts.

Our terminology consequently changes and the focus of our story changes as we go back in time. We gradually start looking at our respective family descendants in terms of genetic distance, the location and movement of genetic lineages and haplogroups, and the presence of ancient cultures that might correlate with where our descendants may have been situated.

Genetic genealogy introduces a different view of time and the analysis of ‘genealogical facts’. If we add genetic genealogy as another possible source of genealogical methods to retrieve facts and evidence, then the notion of time radically expands in scope and how we perceive and measure time and view genealogical stories.

The type and nature of genealogical stories change. These stories will invariably focus on genetic distance rather than generations. As we get further away from the present and beyond ten generations ago, the stories will generally shift from individuals and families to lineages representing faceless individuals and groups. The branches in family trees no longer represent individuals but historical points of genetic mutations where we can pinpoint the ‘most common recent ancestor‘.

Sources

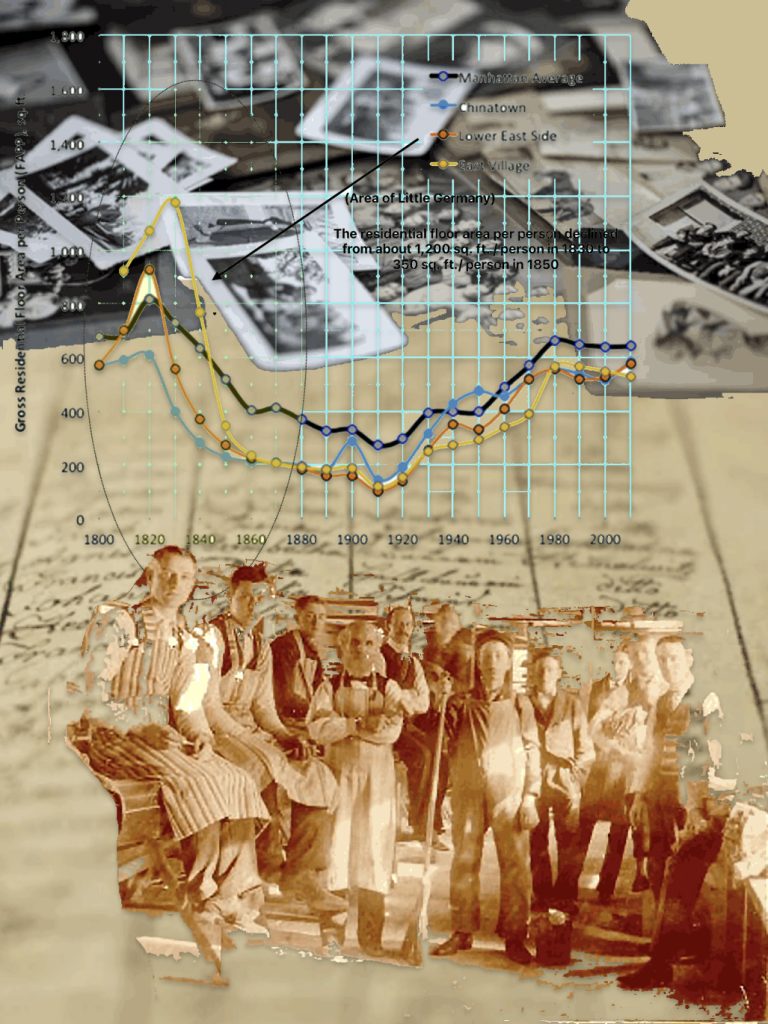

Feature Image: An amalgam of stock photographs about genealology from: Alpenwild: Alpine Adventures Perfected, https://www.alpenwild.com/staticpage/genealogy-research-in-germany-switzerland/ ; and from https://stock.adobe.com/

[1] See my Story: Part Three: How Do You Spell Griffis? April 2, 2022. The present story is an expansion and revision of my discussion of how I evaluated different sources of evidence when examining the different spellings of the Griffis(th)(es) surname among descendants of William Griffis, our genealogical “brick wall’ based on traditional sources of genealogical information for the surname.

[2] First sentence of Chapter One, Board for Certification of Genealogists, Genealogy Standards Nashville: Turner Publishing Co., 2021

[3] Founded in 1964 by Fellows of the American Society of Genealogists, the BCG serves as a certifying body for genealogistsThe BCG’s primary mission is to foster public confidence in genealogy as a respected branch of history. It accomplishes this through two main approaches:

- Standards Promotion: The organization promotes and maintains high ethical and technical standards in genealogical research and writing

- Certification: The BCG offers a rigorous certification process for genealogists, granting the title of Certified Genealogist (CG) to those who meet their stringent standards.

The BCG publishes the “Genealogy Standards,” which serves as an official manual and guide for family historians. This publication outlines the standards expected in genealogical research and writing.

Board for Certification of Genealogists, BCG, FamilySearch Wiki, This page was last edited on 4 November 2022, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Board_for_Certification_of_Genealogists,_BCG

Board for Certification of Genealogists, Genealogy Standards, second edition revised (Nashville: Ancestry.com, 2021)

[4] This quote is often used as a preamble to discussing genealogical methods and research. See for example:

Alice Childs, Genealogy Terminology: Genealogical Proof Standard, May 1, 2019, Alice Childs Blog, https://alicechilds.com/genealogy-terminology-genealogical-proof-standard/

Liz Sonnenberg, Seeking the True Story, May 17, 2023, Modern Memoirs Publishing, https://www.modernmemoirs.com/mmblog/2023/5/seeking-the-true-story

Linda Harms Okazaki, LGBTQ+ genealogy – Be proud of your ancestors, Jun 22, 2023, Nichi Bei News, https://www.nichibei.org/2023/06/finding-your-nikkei-roots-lgbtq-genealogy-be-proud-of-your-ancestors/

[5] Micro-history is a genre of historical research and writing that focuses on small-scale subjects or events to illuminate larger historical issues and trends. Microhistory offers a way to illuminate the textures of everyday life in the past and connect individual experiences to broader historical forces. By zooming in on small-scale subjects, it aims to reveal insights about historical processes that may be obscured at larger scales of analysis.

This approach emerged in the 1970s as a reaction against broad quantitative social history approaches.

For some micohistorians, their focus is on outliers rather than looking for the average individual as found by the application of quantitative research methods. In microhistory the term “normal exception” is used to penetrate the importance of this perspective.

Core Principles of micro-history are:

- Uncover the lived experiences of ordinary people and marginalized groups;

- Focus on small units of study, such as an individual, family, community, or specific event;

- Ask “large questions in small places” by connecting micro-level details to macro-level historical processes.

The methodological approach of microhistory tends to:

- Involve the analysis of primary sources and archival documents;

- Use narrative techniques to tell stories about the past;

- Utilize personal documents ( “ego documents”) like diaries and letters to access historical actors’ perspectives;

- Track clues across multiple sources to discover hidden connections; and

- Employ what has ben called the “evidential paradigm” – using small details to make larger inferences

Microhistory, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 22 March 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microhistory

Sigurdur Gylfi Magnusson, What is Microhistory?, History News Network, https://www.hnn.us/article/what-is-microhistory

Ginzburg, Carlo, et al. “Microhistory: Two or Three Things That I Know about It.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 20, no. 1, 1993, pp. 10–35. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1343946

Burke, Peter (1991). “On Microhistory”. In Levi, Giovanni (ed.). New Perspectives on Historical Writing. New Perspectives on Historical Writing. (1992). United States: Pennsylvania State University Press.

[6] Mills, C. Wright, The sociological Imagination, New York: Oxford University press, 1959, https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Sociological_Imagination/UTQ6OkKwszoC

See also:

The Sociological Imagination, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 13 August 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sociological_Imagination

Rose, Arnold M. “Varieties of Sociological Imagination.” American Sociological Review, vol. 34, no. 5, 1969, pp. 623–30. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2092299

Winter, Gibson. “The Sociological Imagination.” The Christian Scholar, vol. 43, no. 1, 1960, pp. 61–64. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41177145

Allen, Danielle. “On the Sociological Imagination.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 30, no. 2, 2004, pp. 340–41. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1086/421129

Kolb, William L. “Values, Politics, and Sociology.” American Sociological Review, vol. 25, no. 6, 1960, pp. 966–69. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2089989

[7] Elizabeth Shown Mills, Bridging the Historic Divide: Family History and “Academic” History, “History or Genealogy? Why Not Both?” presented at the Indianapolis-based Midwestern Roots Conference, Sponsored jointly by the Indiana Historical Society and the Indiana Genealogy Society, August 2004, Page 2 https://www.historicpathways.com/download/bridghisdivideivide.pdf

See also:

Elizabeth Shown Mills, Academia vs. Genealogy Prospects for Reconciliation, National Genealogical Society Quartrerly, Volume 71 , Number 2, June 1983, Pages 99 – 106 , https://www.historicpathways.com/download/acadvgenea.pdf

Elizabeth Shown Mills, Genealogy in the “Information Age”: History’s New Frontier?, national Genealogical Society Quarterly 91 (December) 2003, Pages 260-277, https://historicpathways.com/download/genininfoage.pdf

Taylor, Robert & Ralph J. Crandall, Historians and Genealogists: An Emerging Community of Interest, Chapter One in Robert M. Taylor & Ralph J. Crandall, Eds., General and Change: Genealogical Perspectives in Social History, Macon: Mercer University Press, 1986, Pages 3 – 28

Hays, Samuel P., History and Genealogy: Patterns of Change and Prospects for Cooperation, Cahpeter Two in Robert M. Taylor & Ralph J. Crandall, Eds., General and Change: Genealogical Perspectives in Social History, Macon: Mercer University Press, 1986, Pages 29 – 52

[8] For a similar view, see: Lisson, Lisa, Use Social History in Genealogy Research – Telling Your Ancestors’ Stories, Dec 2, 2019, Are you My cousin? Genealogy, https://lisalisson.com/social-history-genealogy/

[9] Durie, Bruce, Welsh Genealogy, Stroud, United Kingdom: The History Press, 2013, Page 7

[10] French historian Lucien Febvre first articulated the concept in 1932 as “histoire vue d’en bas et non d’en haut”. E.P. Thompson’s work, particularly “The Making of the English Working Class,” helped establish this approach. The movement gained momentum during the 1960s alongside social movements for civil rights and equality.

This approach emerged as a challenge to prevailing historical traditions, seeking to understand how common people, workers, marginalized groups, and the lower strata of society shaped and were shaped by historical events. This approach examined lives of laborers, families, and communities. It analyzed daily experiences, culture, and social conditions of ordinary people. Its contemporary significance provides a more inclusive and comprehensive view of historical events. It helps recover voices of those traditionally excluded from historical narratives

Manning, Patrick, The case for ‘Bottom-Up’ History, 1 Nov 2022, Patrick Manning Blog, https://patrickmanningworldhistorian.com/blog/culture-knowledge/the-case-for-bottom-up-history/

Boyce, Bruce, History From the Bottom Up 1 Aug 2020, I Take My Hsitory with My Coffee, https://www.itakehistory.com/post/history-from-the-bottom-up

Richard Evans, In Defense of History (London, UK: Granta Books, 1997), 161.

E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (London, UK: Victor Gollancz, Ltd, 1965), 194.

Eileen Cheng, Historiography: an Introductory Guide (New York, NY: Bloomsbury, 2012), 136.

[11] Social History, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 15 September 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_history

Social Science History, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 1 January 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_Science_History

The following are samples of social history research in this time period:

Walkowitz, Daniel , Worker City, Company Town, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978

Hershberg, T. (1973). The Philadelphia Social History Project: A Methodological History. United States: Stanford University.

Kladstriup, Regan, Philadelphia Social History project,The Encyclopadia of Greater Philadelphia, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/philadelphia-social-history-project/

Lardner, James. “History by Numbers: Defending Computers as Contemporary Tool.” The Washington Post, March 9, 1982.

Hershberg, Theodore, et al. “The Philadelphia Social History Project,” Historical Methods Newsletter special issue, v.9, no.2-3 (March-June 1976).

Hershberg, Theodore, ed. Philadelphia: Work, Space, Family, and Group Experience in the Nineteenth Century, Essays Toward an Interdisciplinary History of the City. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981.

Furstenberg, Frank Jr., Theodore Hershberg, and John Modell. “The Origins of the Female-Headed Black Family: The Impact of the Urban Environment,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 6, no. 2 (September 1975), 211-33.

Glassberg, Eudice. “Work, Wages and the Cost of Living: Ethnic Differences and the Poverty Line, Philadelphia, 1880.” Pennsylvania History, vol. 46, no. 1 (January 1979), 17-58

Haines, Michael. “Fertility and Marriage in a Nineteenth-Century Industrial City: Philadelphia, 1850-1880,” Journal of Economic History, vol. 40, no. 1 (March 1980), 151-158

Laurie, Bruce, Theodore Hershberg, and George Alter. “Immigrants and Industry: The Philadelphia Experience, 1850-1880,” Journal of Social History, vol. 9, no. 2 (Winter 1975), 219-248.

Laurie, Bruce. Working People of Philadelphia, 1800-1850. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1980.

Modell, John, Frank F. Furstenberg Jr., and Theodore Hershberg. “Social Change and Transitions to Adulthood in Historical Perspective,” Journal of Family History, vol. 1, no. 1 (September 1976), 7-32.

Seaman, Jeff, and Gretchen Condran. “Nominal Record Linkage by Machine and Hand: An Investigation of Linkage Techniques Using the Manuscript Census and the Death Register, Philadelphia, 1880,” 1979 Proceedings of the Social Statistics Section of the American Statistical Association, 678-683.

See also:

Clayton, Mary Kupiec, Elliott J. Gorn, Peter W. Williams, Encyclopedia of American social history, 3 Volumes, New York: Scribner, 1993, Volume II: https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofam0002unse_d6v8/page/n5/mode/2up

Cross, Michael S, updated by Julia Skikavich, March 4, 2015, The Canadian Encyclopedia, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/social-history

Fairburn, Miles, Social History: problems, strategies, and methods, New York : St. Martin’s Press, 1999, https://archive.org/details/socialhistorypro0000fair_d9v5

Himmelfarb, Gertrude. “The Writing of Social History: Recent Studies of 19th Century England.” Journal of British Studies, vol. 11, no. 1, 1971, pp. 148–70. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/175042

Staughton Lynd, Doing History From the Bottom Up: On E. P. Thompson, Howard Zinn, and rebuilding the labor movement from below, Haymarket, eBook, 2014

Peter N. Stearns, “Social History and World History: Prospects for Collaboration.” Journal of World History 2007 18(1): 43-52

[12] Some key quantitative approaches included:

- Historical demography using parish registers and censuses to study population trends;

- Economic history combining firm-level or individual data wit statistics to test economic hypotheses;

- Political history analyzing voting statistics and legislative roll calls; and

- Large digitization projects to create databases of historical records for quantitative analysis.

The use of quantitative methods in leading historical journals declined sharply after the mid-1980s. Many social historians began moving away from economic and social science frameworks.

[13] The field has evolved to recognize that the selection of methodological approaches should be based on pragmatic considerations rather than rigid adherence to a single method. This has led to more innovative and comprehensive research approaches, particularly in studying complex social phenomena.

Methodological Pluralism, encyclopedia.com, https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/methodological-pluralism

For examples of social history studies that I have utilized that analyze macroscopic historical trends with microscopic or local historical data that is similar to genealogical approaches, see the following for a good overview of the various approaches used to understanding German immigration:

Kamphoefner, Walter, D., The Westfalians, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987

Walter D. Kamphoefner, “Immigrant Epistolary and Epistemology: On the Motivators and Mentality of Nineteenth-Century German Immigrants,” Journal of American Ethnic History 28, no. 3 (Spring 2009): 34

Rudolph Vecoli, European Americans: From Immigrants to Ethnics, Section I : Immigrants, Ethnics, Americans, Cleveland Ethnic Heritage Studies, Press Books, Cleveland State University 1976. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/ethnicity/chapter/european-americans-from-immigrants-to-ethnics/

James Boyd in his Introduction to his PhD Dissertation , The Limits to Structural Explanation, provides a good overview of the historical approaches that have been used for explaining German migration to America, see:

James D. Boyd, An Investigation into the Structural Causes of German-American Mass Migration in the Nineteenth Century, Submitted for the award of PhD, History, Cardiff University 2013, https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/47612/1/2013boydjdphd.pdf

Helbich, Wolfgang. “German Research on German Migration to the United States.” Amerikastudien / American Studies, vol. 54, no. 3, 2009, pp. 383–404. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41158447

Günter Moltmann, “Migrations from Germany to North America: New Perspectives.” Reviews in American History, vol. 14, no. 4, 1986, pp. 580–96. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2702202

Wegge, Simone A. “Chain Migration and Information Networks: Evidence from Nineteenth-Century Hesse-Cassel.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 58, no. 4, 1998, pp. 957–86. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2566846

Cohn, Raymond L., and Simone A. Wegge. “Overseas Passenger Fares and Emigration from Germany in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Social Science History, vol. 41, no. 3, 2017, pp. 403. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/90017919

Wegge, Simone A. To part or not to part: emigration and inheritance institutions in mid-19th century Germany. Explorations in Economic History 36, 1999, pp. 30-55.

Nadel, Stanley, Little Germany: Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City 1845-80, Urbana:University of Illinois Press, 1990,

Félix Krawatzek and Gwendolyn Sasse, Writing home: how German immigrants found their place in the US, February 18, 20016, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/writing-home-how-german-immigrants-found-their-place-in-the-us-53342

Félix Krawatzek, Gwendolyn Sasse, The simultaneity of feeling German and being American: Analyzing 150 years of private migrant correspondence, Migration Studies, Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2020, Pages 161–188 https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mny014

Félix Krawatzek and Gwendolyn Sasse, Deciphering Migrants’ Letters, November 28, 2018, comparative Studies in Society and History, https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/cssh/tag/krawatzek/

Walter D. Kamphoefner, Wolfgang Helbich, et al., Editors., News from the Land of Freedom: German Immigrants Write Home (Documents in American Social History) : Cornell University Press, 1991.

[14] Hays, Samuel P., History and Genealogy: Patterns of Change and Prospects for Cooperation, Chapter Two in Robert M. Taylor & Ralph J. Crandall, Eds., General and Change: Genealogical Perspectives in Social History, Macon: Mercer University Press, 1986, Pages 47

[15] Hays, Samuel P., History and Genealogy: Patterns of Change and Prospects for Cooperation, Chapter Two in Robert M. Taylor & Ralph J. Crandall, Eds., General and Change: Genealogical Perspectives in Social History, Macon: Mercer University Press, 1986, Pages 43

[16] Elizabeth Shown Mills, Bridging the Historic Divide: Family History and “Academic” History, “History or Genealogy? Why Not Both?” presented at the Indianapolis-based Midwestern Roots Conference, Sponsored jointly by the Indiana Historical Society and the Indiana Genealogy Society, August 2004, Page 3 https://www.historicpathways.com/download/bridghisdivideivide.pdf

See also:

Lenstra, Noah , ‘Democratizing ‘ Genealogy and Family Heritage Practices: the View from Urbana, Illinois, In Encounters with Popular Pasts: Cultural Heritage and Popular Culture, Mike Robinson and Helaine Silverman, eds., NewYork: Springer 2015, Page 203

De Groot, Jerome, On Genealogy, The Public Historian, Volume 37, Issue 3, August 2015, Page 119, https://online.ucpress.edu/tph/article-abstract/37/3/102/89479/International-Federation-for-Public-History?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Tucker, Susan. 2016. City of Remembering: A History of Genealogy in New Orleans. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2016, Page 165

Creet, Julia, The Genealogical Sublime, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2020, Page 168

Weil, François. 2007. John Farmer and the Making of American Genealogy. New England Quarterly 80. Pages 408–34., Page 181, https://direct.mit.edu/tneq/article-abstract/80/3/408/15801/John-Farmer-and-the-Making-of-American-Genealogy?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Hareven, Tamara, K., The Search for Generational Memoriy: Tribal Rites in Industrial Society. Daedalus, 107, 1978, Pages 137 – 149

Taylor, Robert M. 1982. Summoning the Wandering Tribes: Genealogy and Family Reunions in American History. Journal of Social History 16, Pages 21–35, https://academic.oup.com/jsh/article-abstract/16/2/21/1031592?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Bidlack, Russell E. 1983. Librarians and Genealogical Research. In Ethnic Genealogy: A Research Guide. Edited by Jessie Carney Smith, Westport: Greenwood Press.1983, Page 9

Morgan, Francesca. 2010a. A Noble Pursuit? Bourgeois America’s Uses of Lineage. In The American Bourgeoisie: Distinction and Identity in the Nineteenth Century. Edited by Sven Beckert and Julia Rosenbaum. New York: Palgrave, 2010, Page 144

Carmen J. Finely, Creating a Winning Family History, NGS Special Publication No. 99, National Genealogical Society, Arlington: National Genealogical Society, 2010

[17] Hays, Samuel P., History and Genealogy: Patterns of Change and Prospects for Cooperation, Chapter Two in Robert M. Taylor & Ralph J. Crandall, Eds., General and Change: Genealogical Perspectives in Social History, Macon: Mercer University Press, 1986

[18] Autosomal DNA, This page was last edited on 21 October 2020, International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki, https://isogg.org/wiki/Autosomal_DNA

Genetic genealogy, This page was last edited on 27 March 2022,, International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki, https://isogg.org/wiki/Genetic_genealogy

Mitochondrial DNA, This page was last edited on 22 May 2018, International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki, https://isogg.org/wiki/Mitochondrial_DNA

Mitochondrial DNA tests, This page was last edited on 13 February 2021, https://isogg.org/wiki/Mitochondrial_DNA_tests

[19] Rob Spencer, Y and mtDNA, May 1, 2023, Case Studies in Macro Genealology, Presentation for the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, Slide Five, July 2021, http://scaledinnovation.com/gg/mnl/mnl3.pdf

[20] Y-STR DNA testing is a specialized form of DNA analysis that exclusively examines short tandem repeats (STRs) found on the male Y chromosome. Y-STR testing can help identify ancestral origins and migration patterns, though with some limitations. The test examines specific patterns on the Y chromosome that are passed down through paternal lineages, creating unique signatures that can trace geographical ancestry.

Y-STRs (Short Tandem Repeats) differ from other Y-SNP markers like SNPs in several key ways. STRs mutate more frequently over time and through generations than SNPs. Changes can occur roughly once every 500 transmissions. Multiple mutations at the same location are common. Y STR analyses are better for looking at recent genealogical connections and useful for determining time frames between common ancestors. They are less effective for deep ancestral research.

Unlike STR DNA, SNP DNA is very stable over many generations. When a mutation does occur, it is carried indefinitely by the male descendants of the individual in whom the SNP was formed – the ‘SNP Progenitor’. This makes SNP DNA testing particularly useful for distinguishing one genetic lineage from another.

Chris Gunter, Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPS), National Human Genome Research Institute, 12 Sep 2022, https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Single-Nucleotide-Polymorphisms

What are single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)?, National Library of Medicine, accessed 10 Jul 2022, https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/genomicresearch/snp/

Single-nucleotide polymorphism, Wikipedia, page accessed 4 Apr 0222, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Single-nucleotide_polymorphism

What are SNP’s, Genetics Generation, Page accessed 15 Jun 2022, https://knowgenetics.org/snps/

Sampson JN, Kidd KK, Kidd JR, Zhao H. Selecting SNPs to identify ancestry. Ann Hum Genet. 2011 Jul;75(4):539-53. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3141729/

National Institute of Justice, “What Is STR Analysis?,” March 2, 2011, nij.ojp.gov:

https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/what-str-analysis

STR analysis, Wikipedia, page was last edited on 13 June 2022, page accessed, 4 Sep 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/STR_analysis

Short Tandem Repeat, International Society of Genetic Genealology Wiki, page was last edited on 31 January 2017,page accessed 10 Oct 2022, https://isogg.org/wiki/Short_tandem_repeat

Wei W, Ayub Q, Xue Y, Tyler-Smith C. A comparison of Y-chromosomal lineage dating using either resequencing or Y-SNP plus Y-STR genotyping. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2013 Dec;7(6):568-572. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2013.03.014. Epub 2013 Jun 13. PMID: 23768990; PMCID: PMC3820021. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3820021/

Y-STR, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 15 February 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Y-STR

A Comparison of Our Y-DNA Tests, FamilyTreeDNA Help Center, https://help.familytreedna.com/hc/en-us/articles/5579319716111-A-Comparison-of-Our-Y-DNA-Tests

[21] Regarding the use of the terms family historian versus genealogist, here are a few examples of the discourse on whether they are distinct or not.

“(T)he two fields can have different priorities. A genealogist, for example, might simply want to know the names and birthplaces of their ancestors. But a family historian would be equally as interested in reconstructing what those ancestors’ lives were like, and learning about other members of their nuclear families.”

Andrew Koch, Genealogy vs. Family History | Definitions and Examples of Each, Family Tree Magazine, April 2023, https://familytreemagazine.com/general-genealogy/what-is-genealogy-family-history/

“Today, the two terms are used interchangeably most of the time. There is a subtle distinction and many would enjoy debating the nuances in the language. Genealogy is often used to describe a line of descent, traced continuously from an ancestor, often also called a lineage. There is some expectation that a genealogy is a formal or scholarly study of ancestral family lines and that documentary evidence of each generational bloodline connection can be proven with evidence and records. Family history also means the study of a family tree and generational connections, but some feel is has a bit more connotation of a biographical study of a family and may include the heritage and traditions a family passed on. Basically both words mean the study of families, finding their stories, and tracing their lineage and history. You will see we interchange the two terms and you can feel free to do so also.”

Are Genealogy and Family History different?, National Genealogical Society, https://www.ngsgenealogy.org/family-history/, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Genealogy

“Genealogical or family history research is the process of searching records to find information about your relatives and using those records to link individuals across several generations.”

Genealogy, Family Search Wik, This page was last edited on 11 May 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Genealogy

“What’s the difference between a genealogist and a family historian? People sometimes use those two concepts as though they were interchangeable, and this adds to the confusion. There are differences between a genealogist and a family historian … For many people, there is some overlap between the tasks that are typically done by a genealogist and the tasks done by a family historian. A person might start by using vital records to fill in their family tree, and then later, start looking for personal stories about those ancestors.”

The Differences between a Genealogist and a Family Historian, FamilyTree, Page accessed Nov 11, 2023 , www.familytree.com/blog/the-differences-between-a-genealogist-and-a-family-historian/

James Tanner, Am I a genealogist or a family historian?, Feb 18, 2014, Genealogy’s Star, Blog, https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2014/02/am-i-genealogist-or-family-historian.html

Paul Chiddicks, Are you a Genealogist or Family Historian?, The Chiddicks family Tree,, Blog, July 17, 2021, https://chiddicksfamilytree.com/2021/07/17/are-you-a-genealogist-or-family-historian/

“Genealogy is defined as the study of a person’s ancestry or lineage. Family history is defined as an extension of genealogy in which the life and times of the people concerned are investigated. So I guess the real difference is that family historians dig a little deeper into genealogy, or at least that’s how I define it. But ultimately the terminology really doesn’t matter at least to me anyway. Because through this journey I have been a genealogist, a family historian, an investigator, a reporter, an analyst, a writer, and a natural observer. I have had to wear many hats to get as far as I have in my research.”

Genealogist or Family Historian… Do You Think There is a Difference???, Journey Through the Generations, Nov 5 2018, https://journeythroughthegenerations.com/2018/11/05/genealogist-or-family-historian-do-you-think-there-is-a-difference/

“To me, a genealogist and a family historian are the same. Without data there can be no narrative. Without the narrative, a genealogy does not meet the industry standards. Context is essential when we research our family history. Some genealogists, sadly even professionals, do not care about context and stories. “

“Not all agree that these terms have different definitions. Lene Dræby Kottal, a professional researcher who holds the Certified Genealogist credential and specializes in Danish ancestry, argues that the two terms amount to a distinction without a difference.”

Lene Kottal, From Data to Narrative: Genealogist versus Family Historian, Genealogist Kottal Blog, Page accessed October 5, 2023, https://www.genealogistkottal.com/danish-genealogy-blog/from-data-to-narrative-genealogist-versus-family-historian/