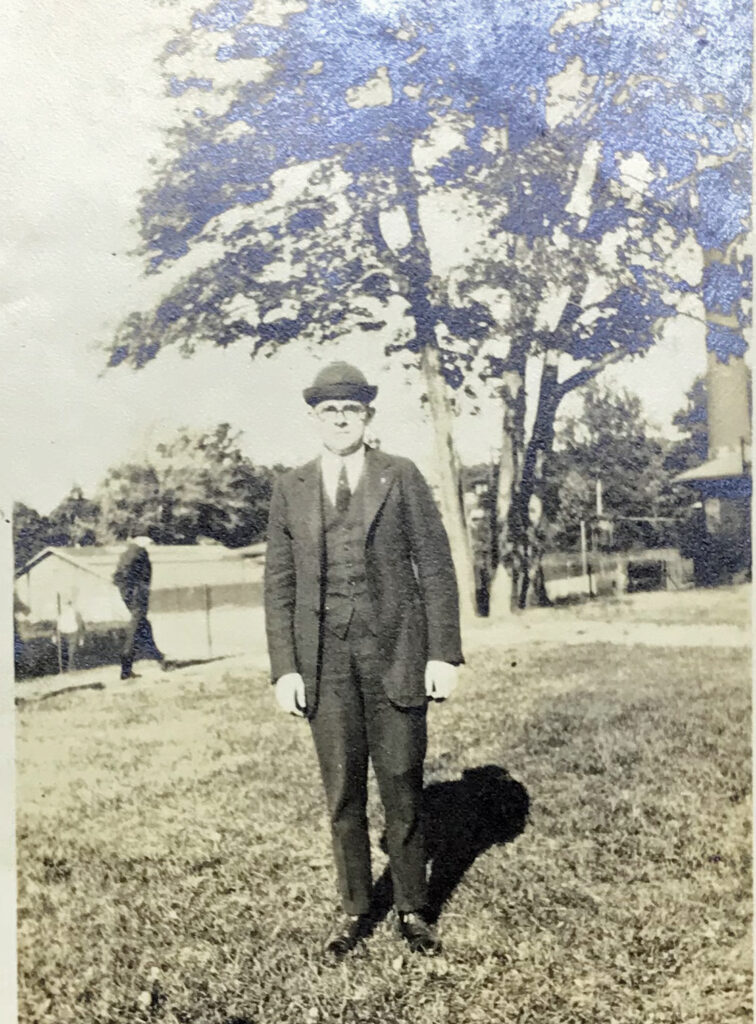

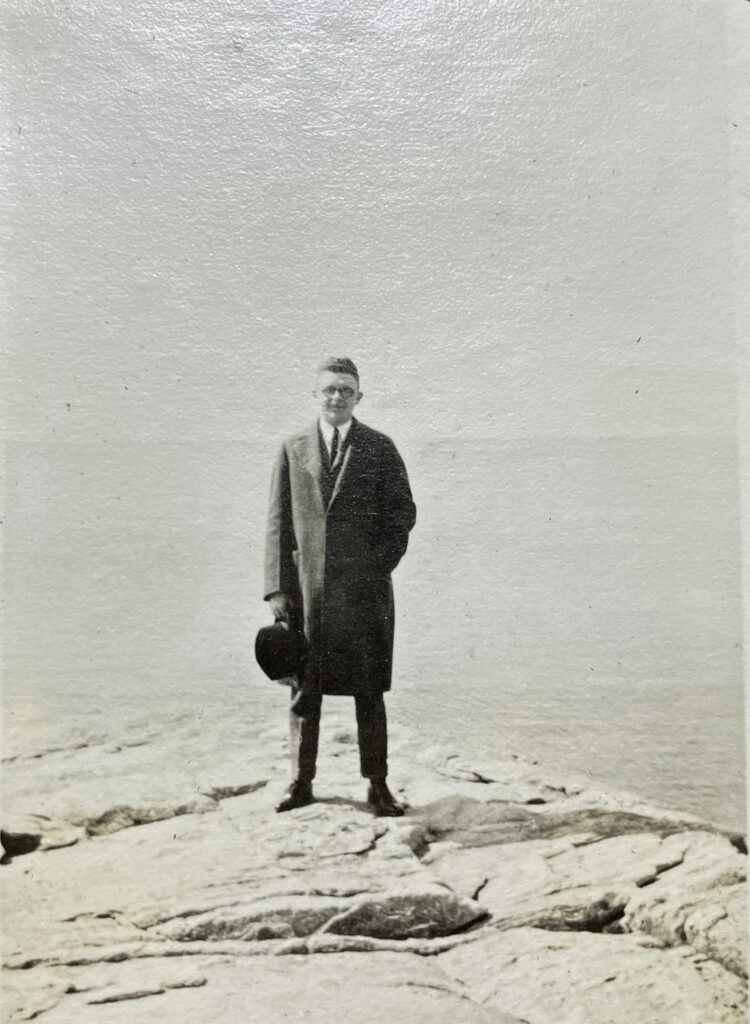

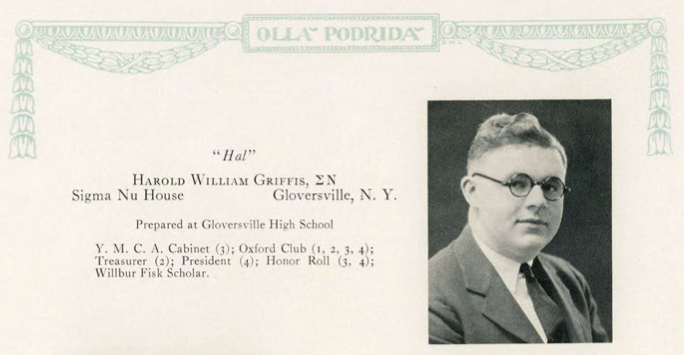

Harold William Griffis (June 29, 1903 – June 30, 1961) was the patriarch of the Griffis family that resided in the Albany-Troy-Schenectady (tri-city), New York area for four of the most recent generations of our family in the 1930’s through the 1950’s. Many of the living members of our current family unfortunately did not get the chance to know Harold Griffis given his untimely death a day after his 58th birthday.

He had a great sense of humor. He would be the first to laugh about himself and would provide stories to any audience to produce laughter and remind everyone of what it is to be human. He had great patience with his family. Harold accepted everyone regardless of limitations or faults and his tacit aim was getting the best out of each individual he came into contact with.

An only child, Harold was born on June 29, 1903 in Gloversville, New York. His parents were Charles Arthur Griffis and Ida May Sperber. Harold’s father Charles, passed away at the age of 49 after Harold graduated from college in 1926.

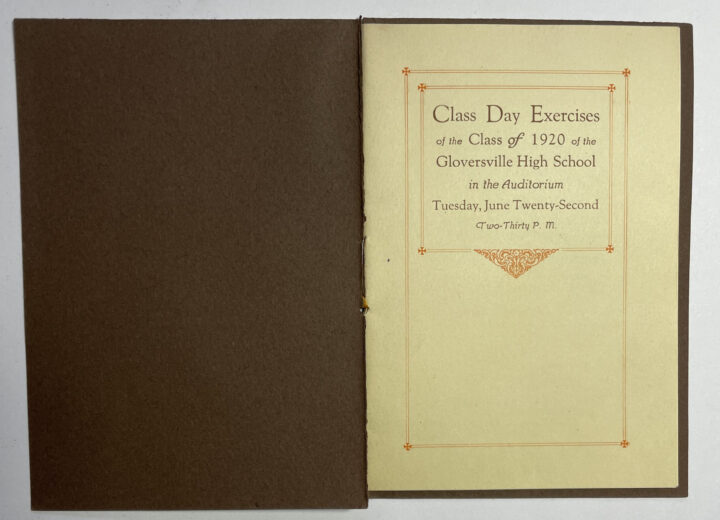

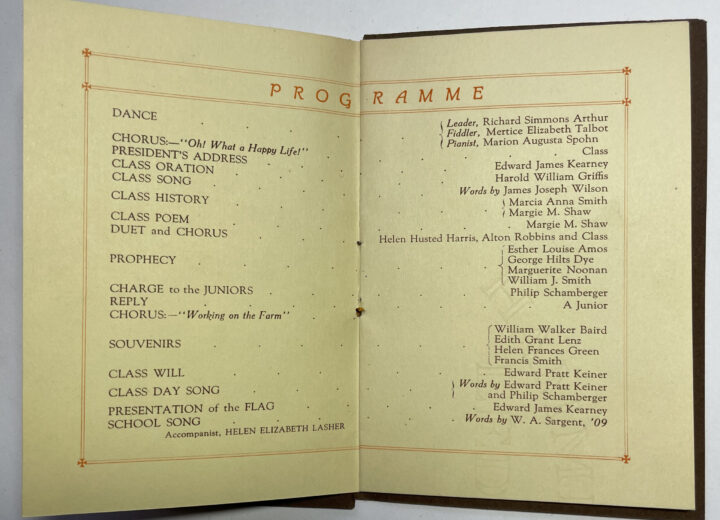

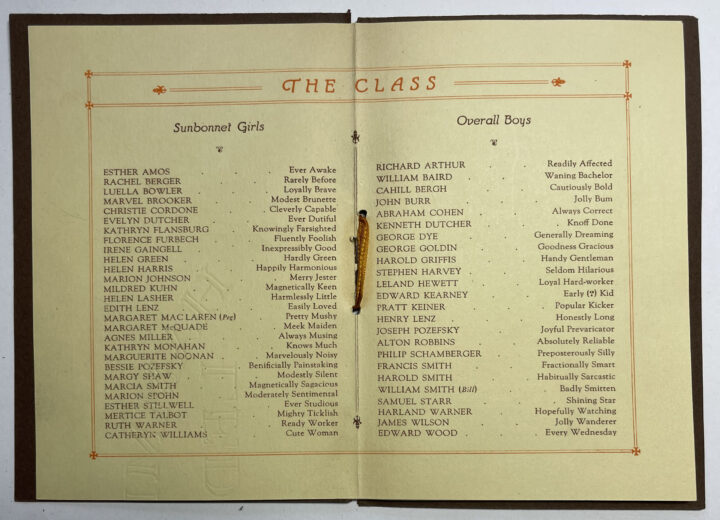

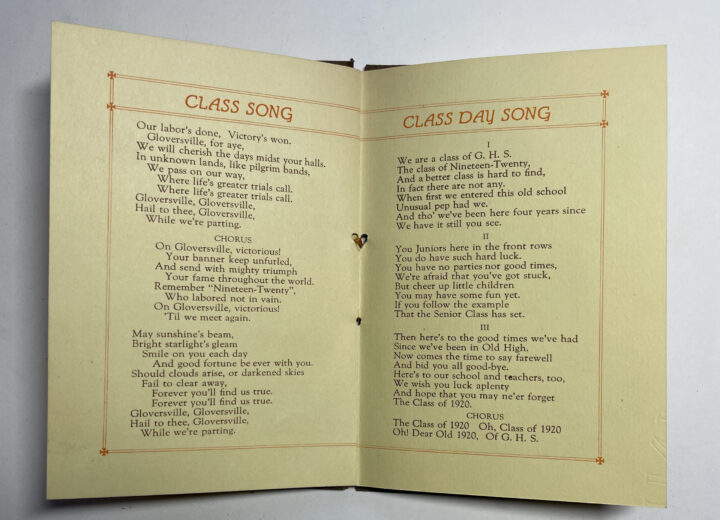

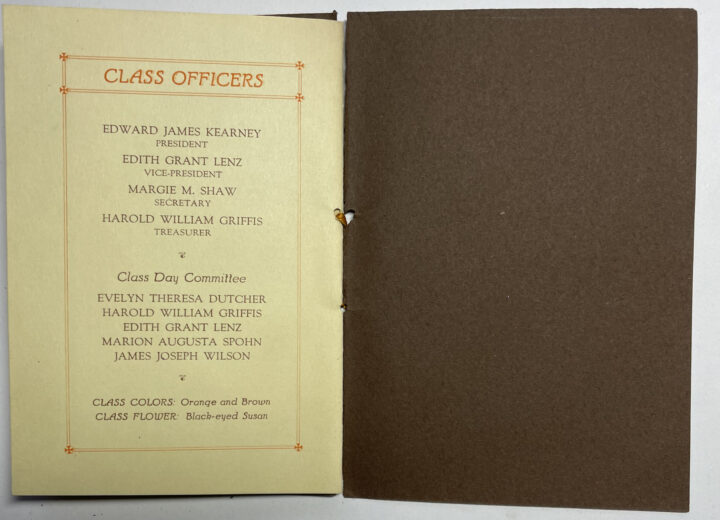

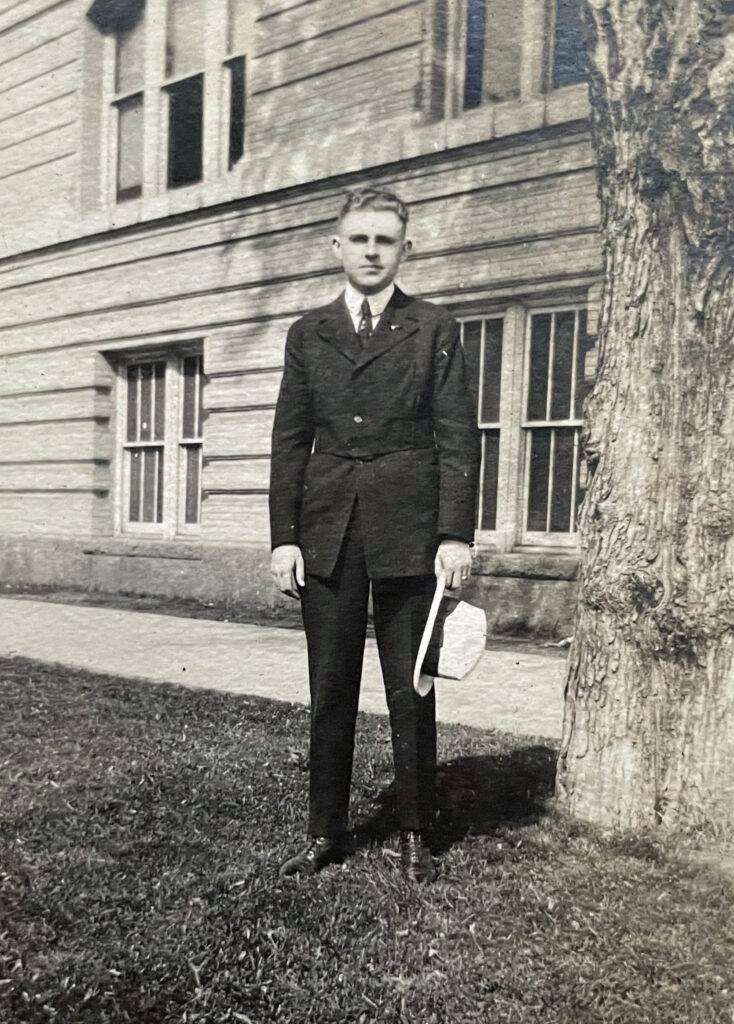

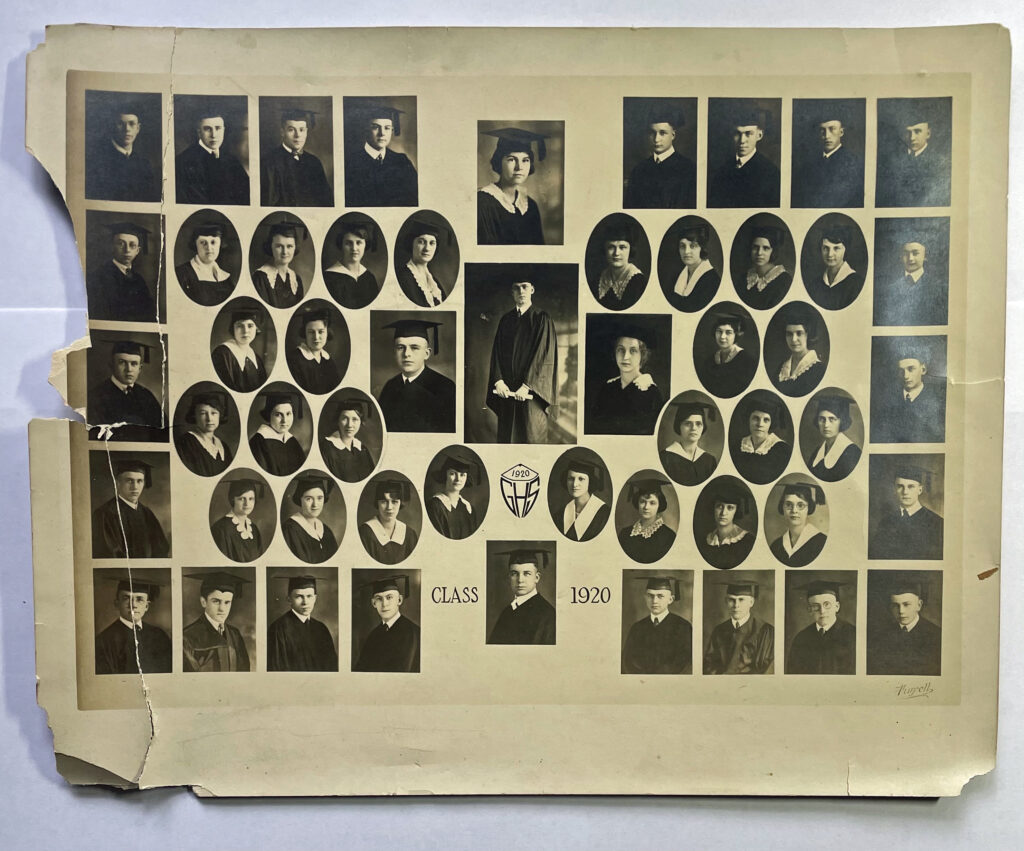

High School Graduation

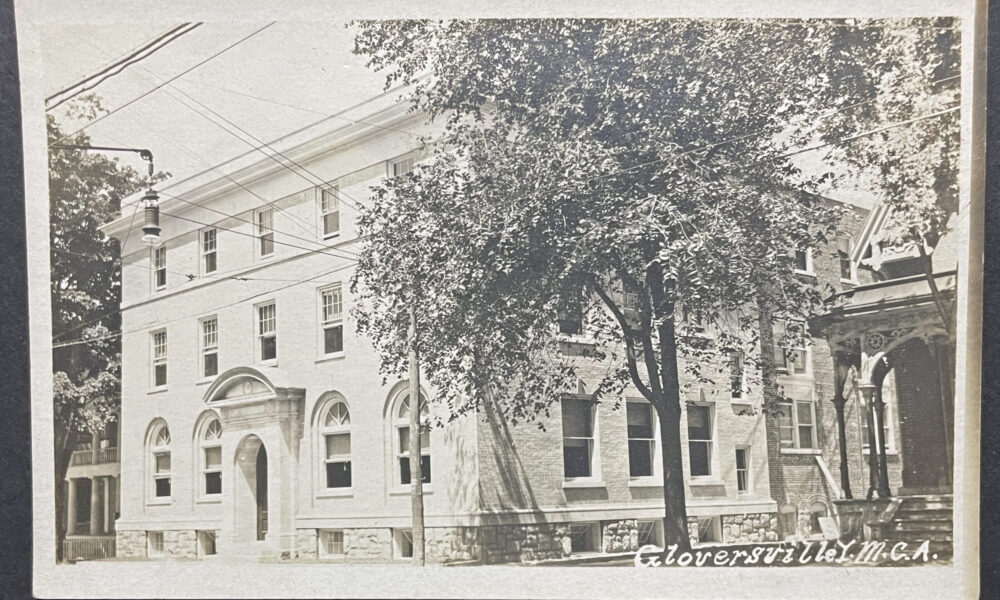

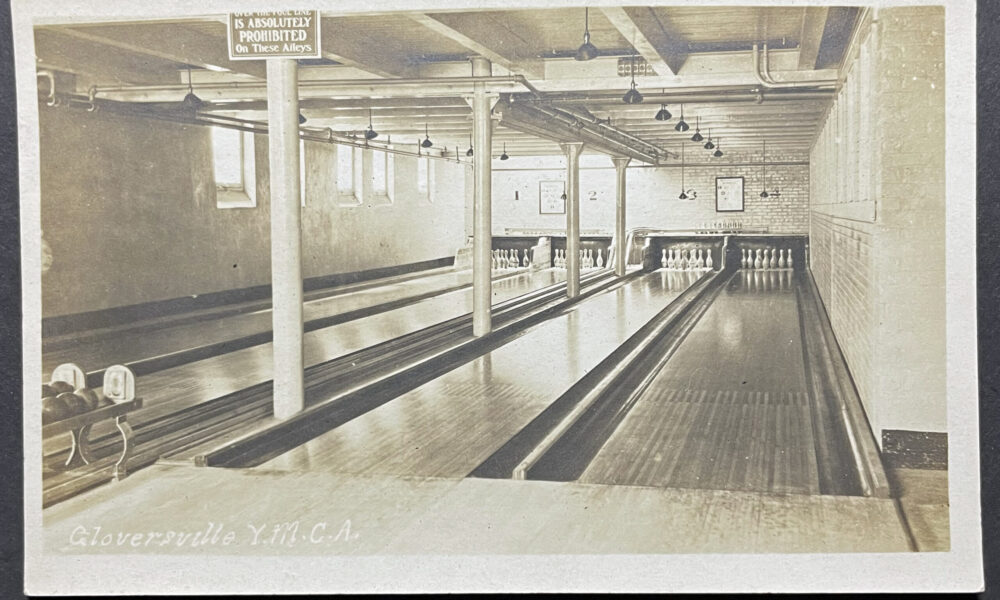

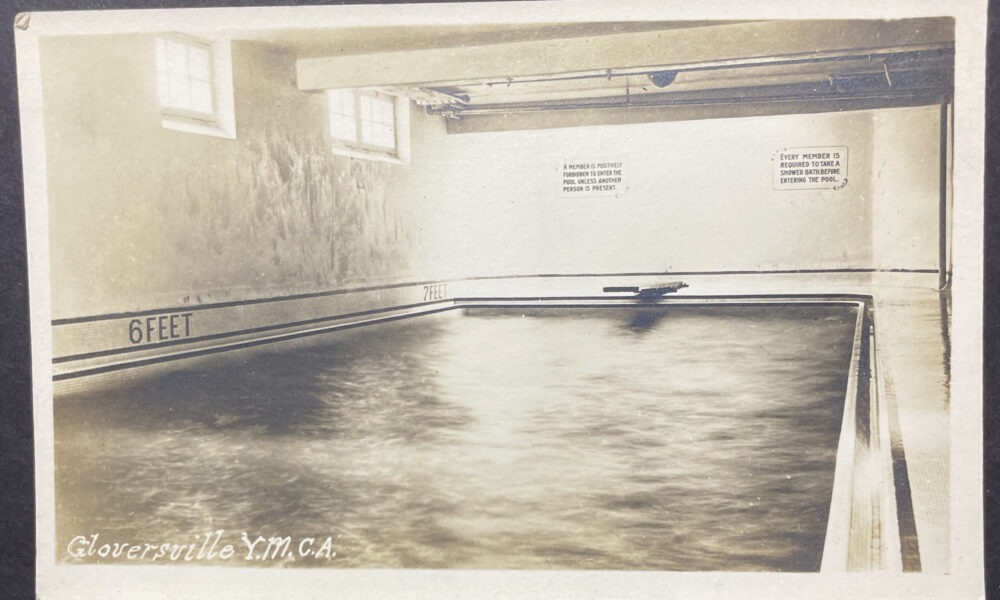

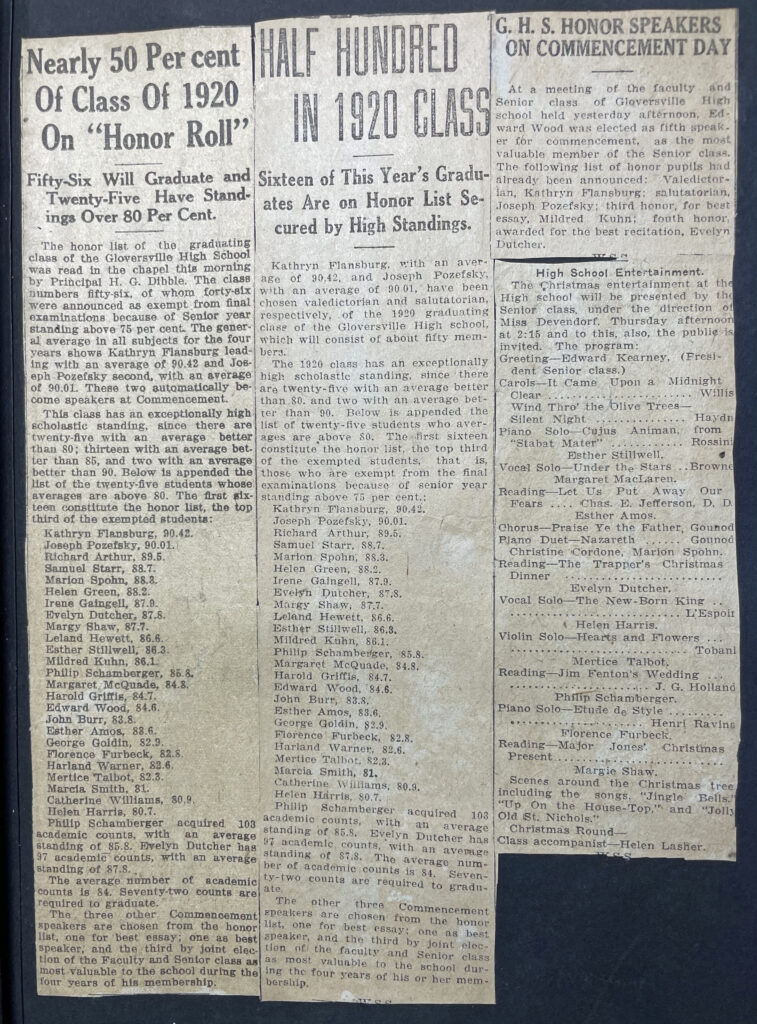

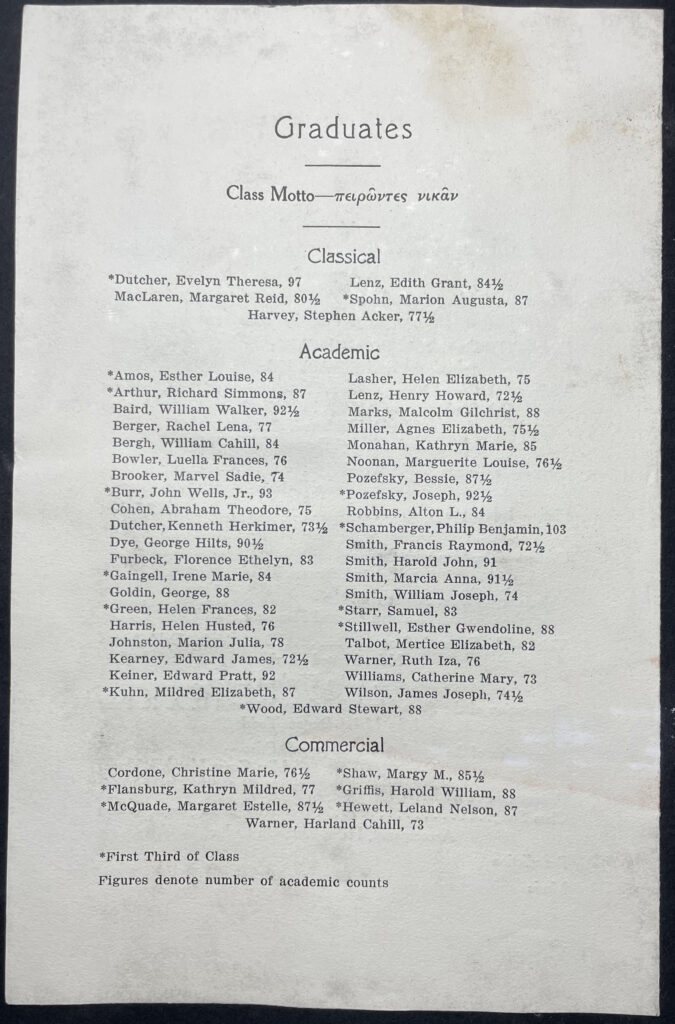

William graduated from Gloversville High School with a commercial diploma and initially worked in the Gloversville YMCA after high school graduation. The following are photos of the original Gloversville commencement exercises program that Evelyn Dutcher Griffis saved and had in a scrapbook. The commencement took place a week before Harold’s birthday. Harold Griffis gave the “Class Oration”. Harold was the senior class treasurer. Harold and Evelyn Dutcher, Harold’s high school sweetheart were part of the five member Class Day Committee. Evelyn was listed as “Ever Dutiful” and Harold was deemed as a “Handy Gentleman”. Kenneth Dutcher, a distant cousin of Evelyn’s, evidently did not enjoy academics as much and graduated in the lower half of the 52 member 1920 graduating class. His senior year moniker was “Knof Done’!

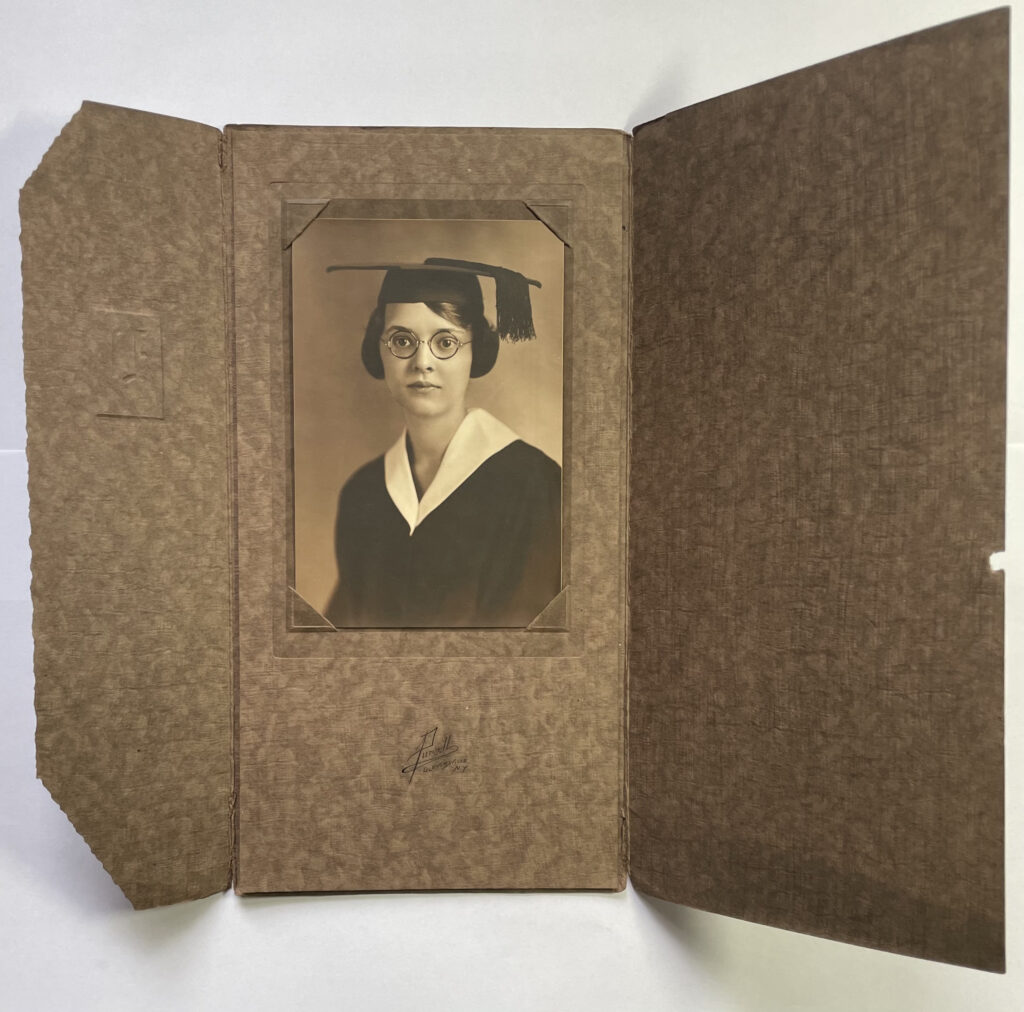

Evelyn Dutcher saved local Gloversville newspaper articles on the high school graduation. Although the Commencement exercises program listed 52 students of the graduating class, the newspaper clipping indicate 56 graduated in 1920 and 25 students had a grade point average over 80. Both Harold and Evelyn were on the honor list of graduates. Evelyn received a ‘Classical’ degree and had a grade average of 87.4 while Harold received a Commercial degree and had a grade average of 84.7. Evelyn was the top in the class in terms of the number of ‘academic counts’ of courses taken in her four years of her high school career. She also received honors providing the best senior recitation.

Evelyn was the top in the class in terms of the number of ‘academic counts‘ of courses taken in her four years of her high school career with 97 and Harold was top among the commercial degree graduates with 87.

The photo below captured 21 of the 24 young men that graduated in 1920. Harold is the fifth person from the left.

Having decided to become a minister while he was in high school, he realized the need to obtain a college degree. In his post high school graduate year he was tutored by his high school sweetheart, Evelyn Theresa Dutcher, to take the required college entrance exams to enter college. While Harold was working, Evelyn went on to teacher’s college immediately after they both graduated from high school.

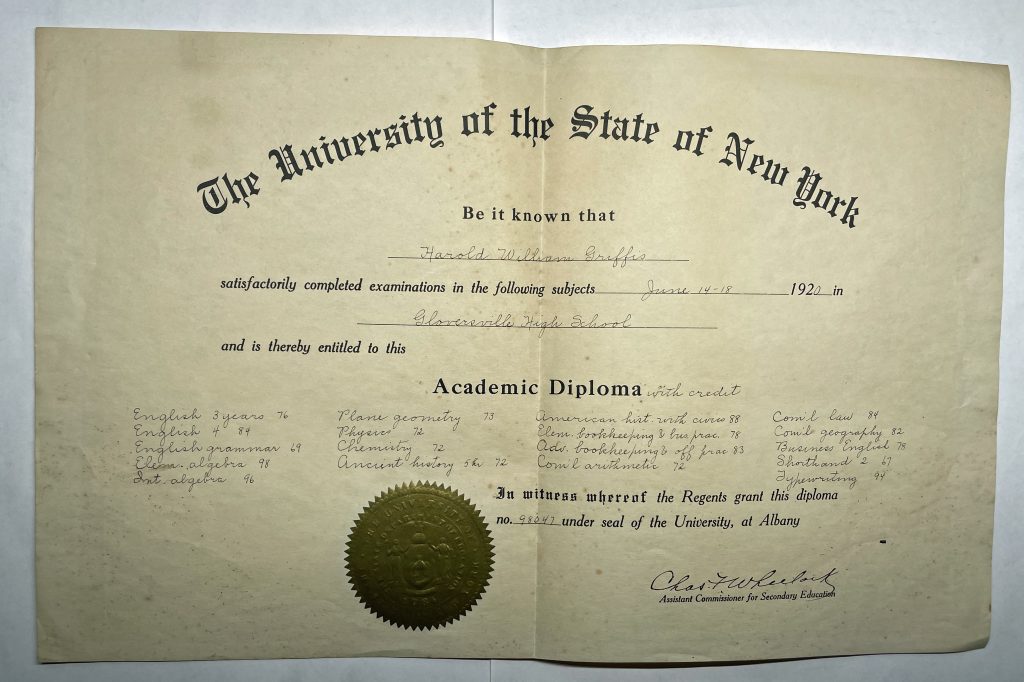

In June 1920 Harold obtained an “Academic Diploma with credit” for high school from the University of the State of New York after passing various examinations in academic subjects. This provided an initial step for him to apply for college.

The following are three postcards of the Gloversville YMCA circa 1920 where harold worked for a year before he went to college.

Freshman Year

With Evelyn’s help, Harold passed the college entrance exams. Harold applied and was accepted to Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut.

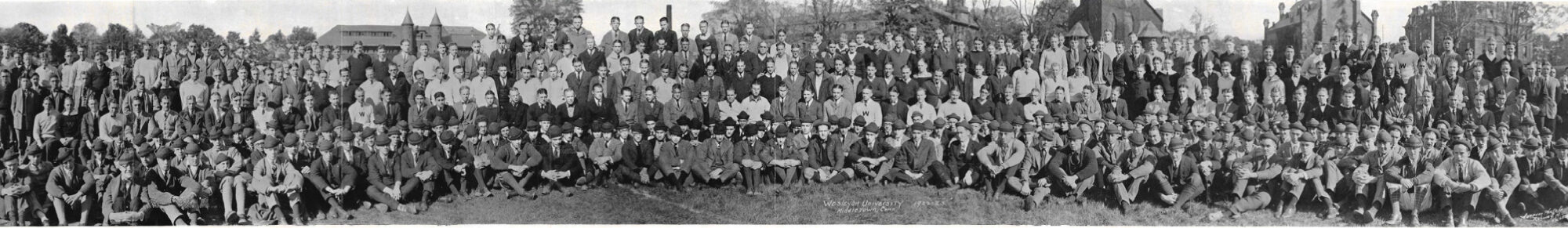

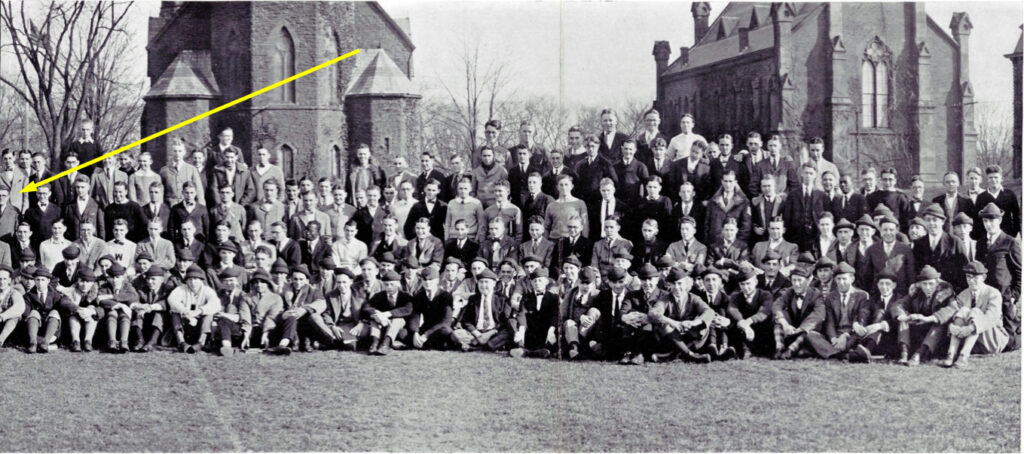

To see where Harold Griffis is in this panoramic photo click for the enlarged view of this photo:

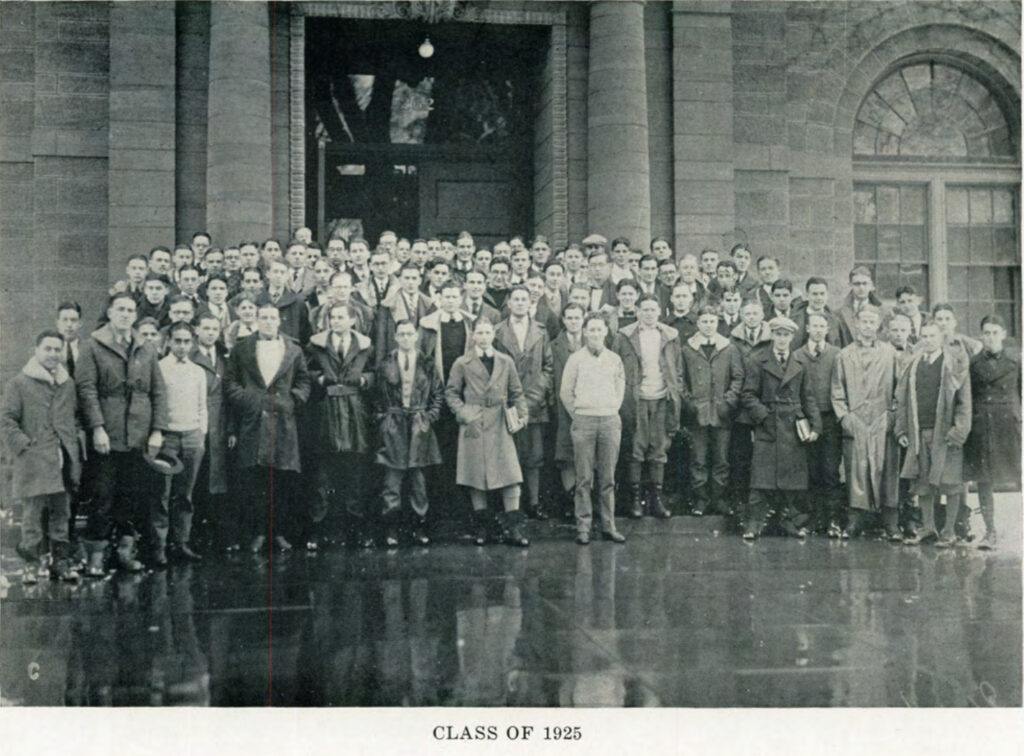

Sophomore Year

It is challenging to figure out where Harold Griffis is in this photo, here is a copy of the photo which identifies where Harold is in the photo.

Also a section of the photo provides a glimpse of Harold in the group photo.

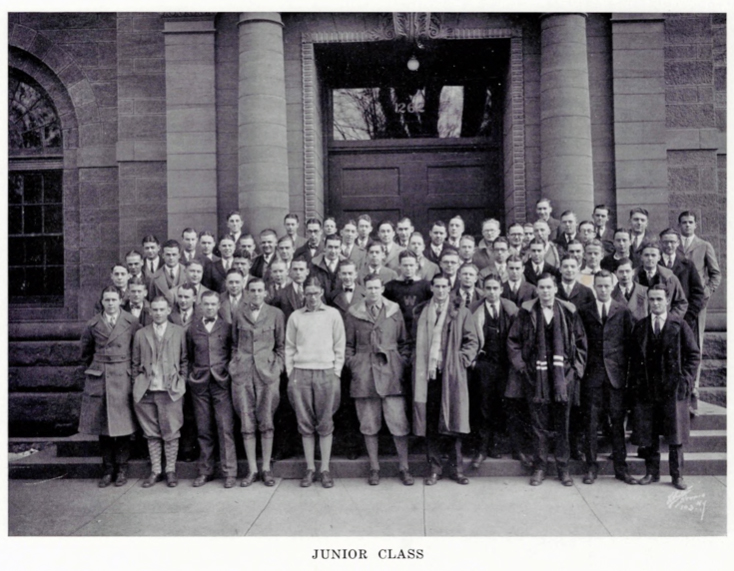

Junior Year

The annual panorama photograph of the entire student body of Wesleyan University for the 1923-1924 school year, Harold’s Junior year. The three photographs scan the student body from left, middle and right. Harold is in the right portion of the panorama, second top row on the extreme left, partially cut on the left hand frame of the photo.

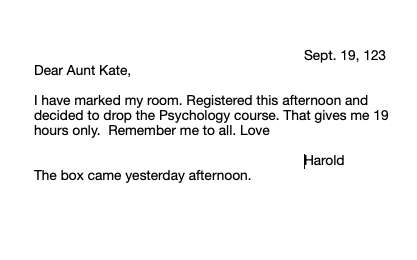

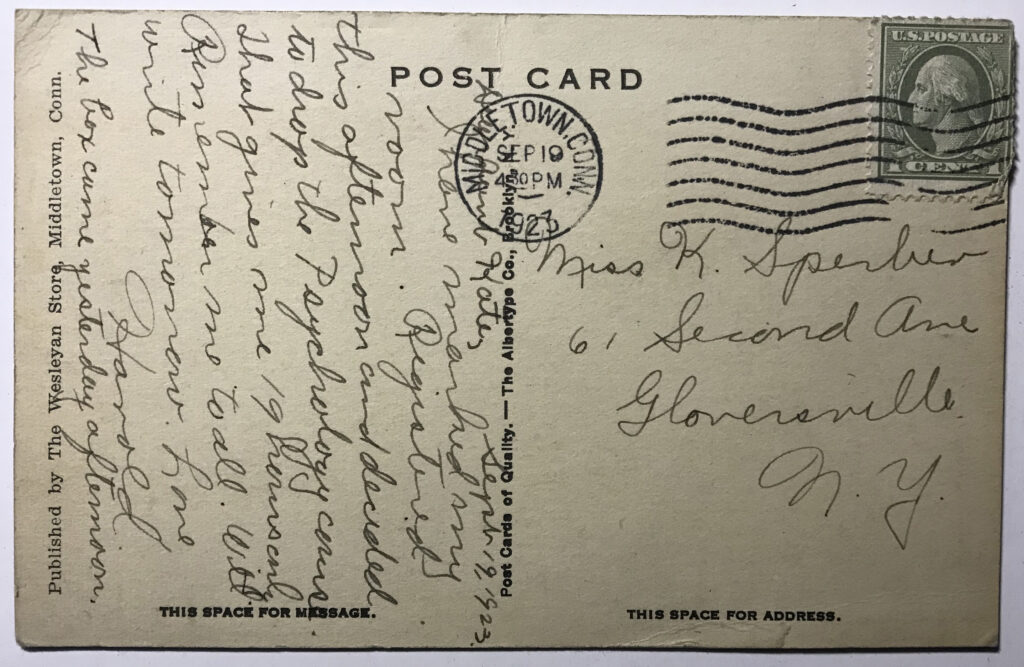

The following is a postcard that Harold sent at the beginning of his Junior year in college on September 19, 1923 to his Aunt Kate Sperber. Kate Sperber was a sister of Ida Sperber, Harold’s mother.

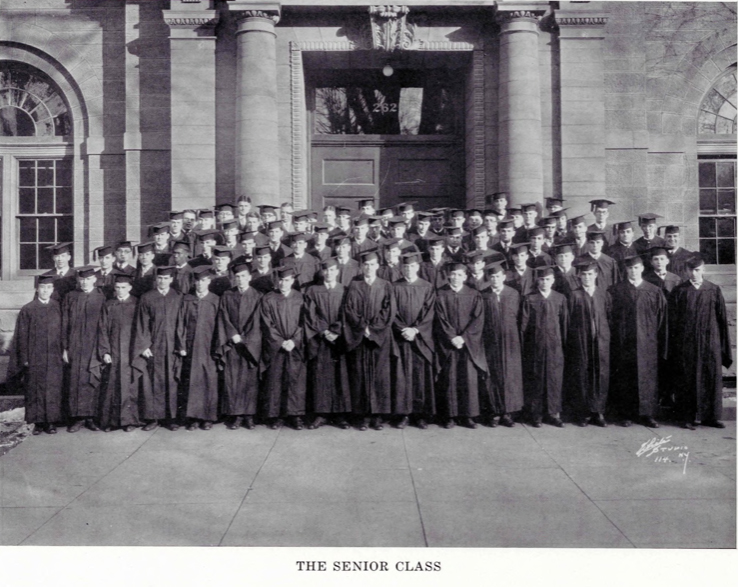

Senior Year

Alas, the student body panorama photograph was not documented in the yearbook when Harold graduated.

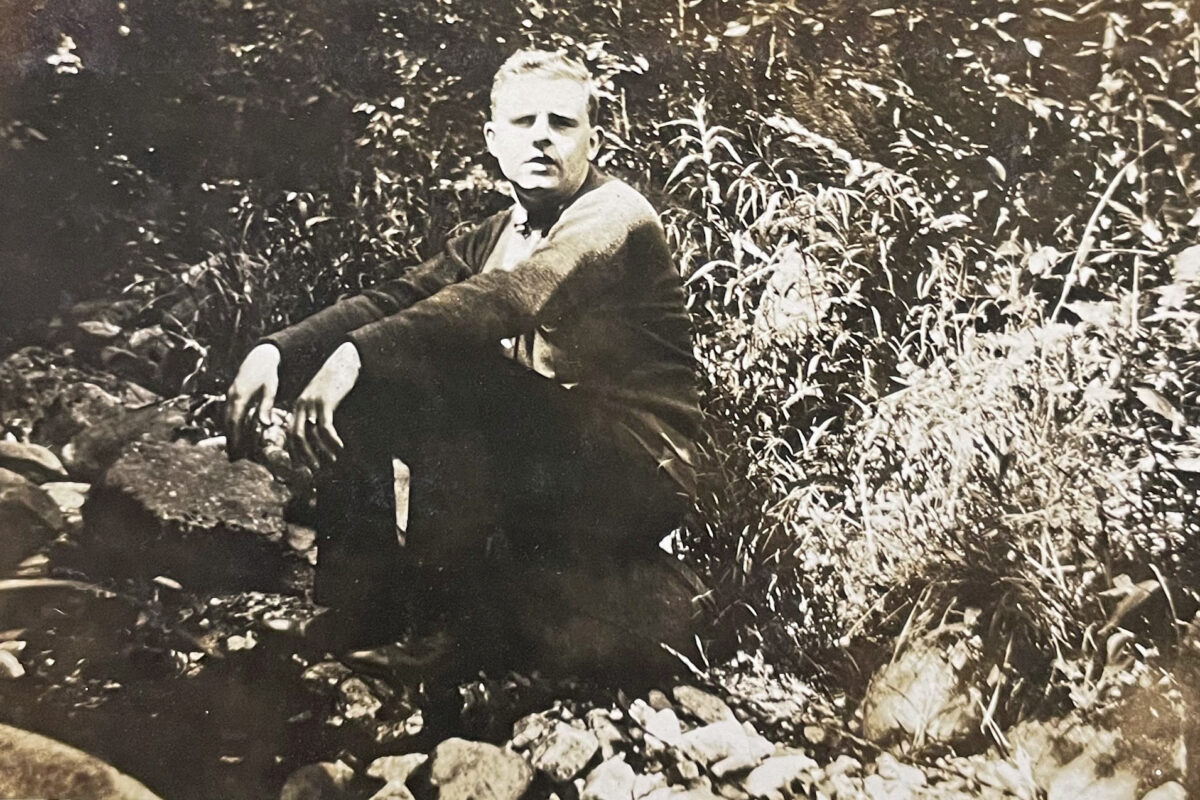

The following are photographs of a hiking trip with Evelyn and friends to Mountain Lake on July 4th, 1924, in between Harold’s junior and senior year.

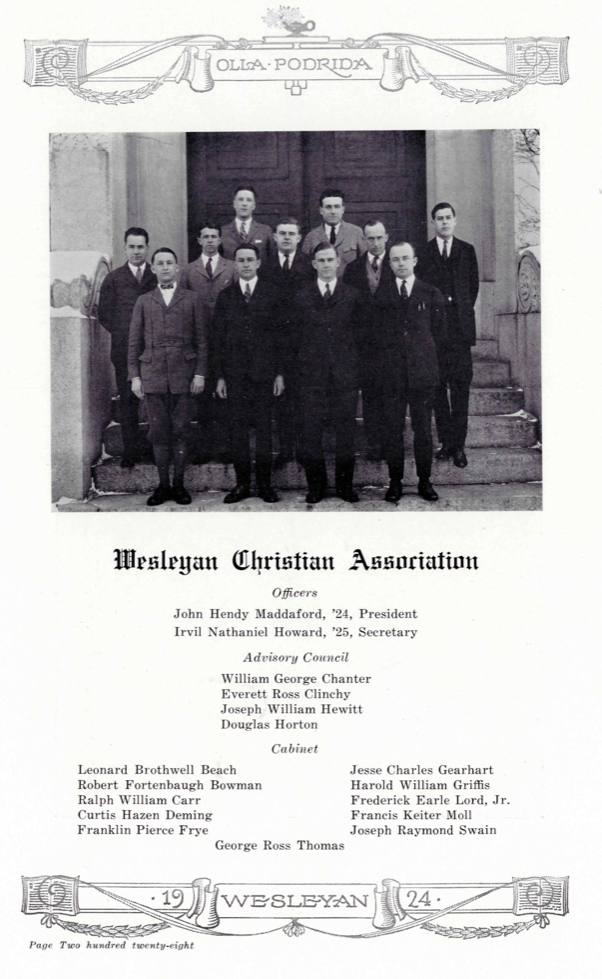

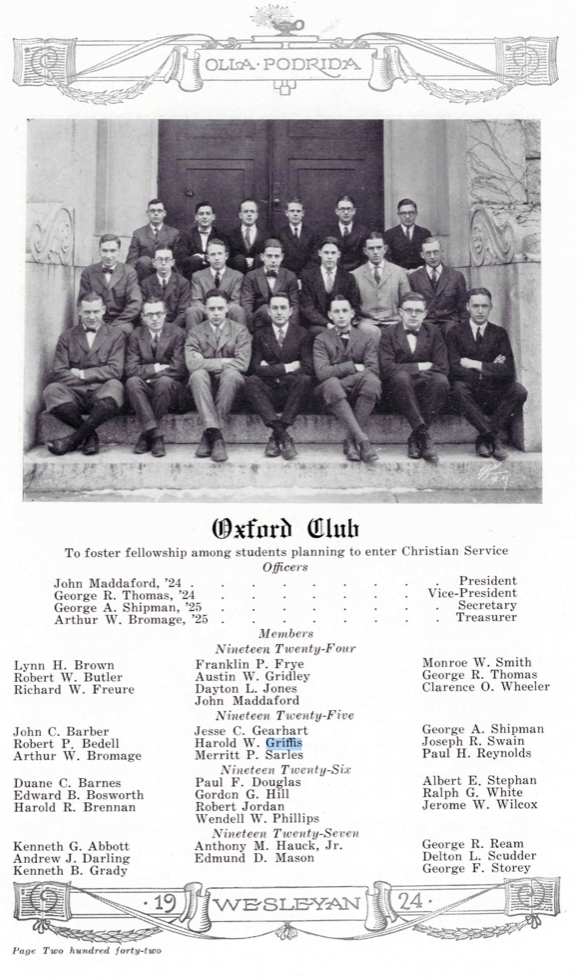

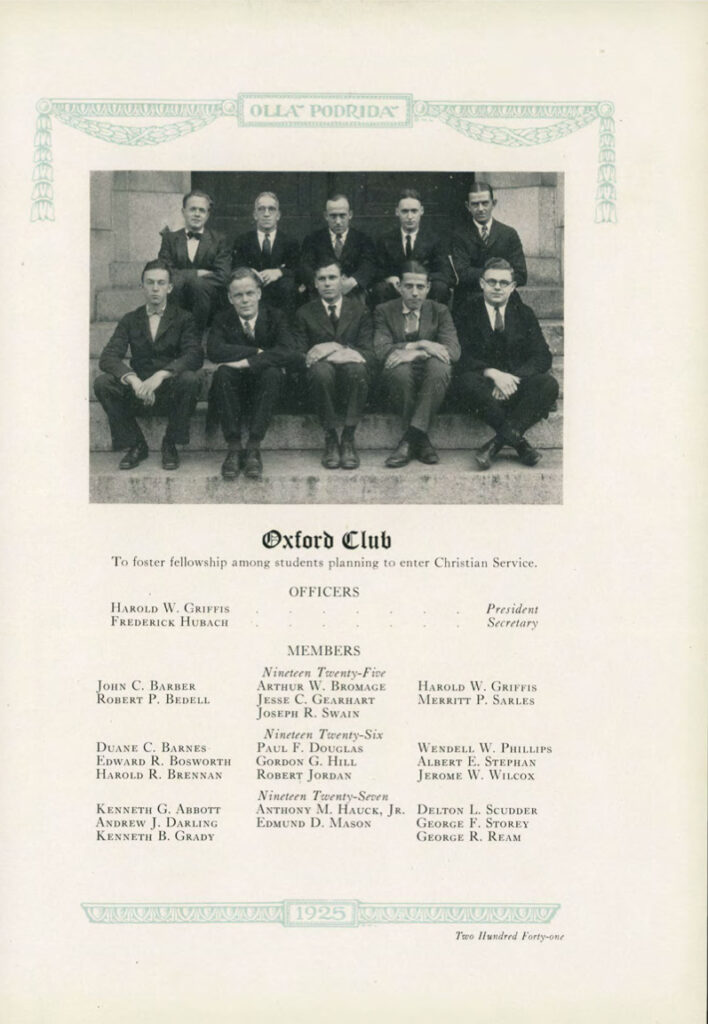

Harold was President of the Oxford Club in his senior year. He was also a cabinet member of the Christian Association.

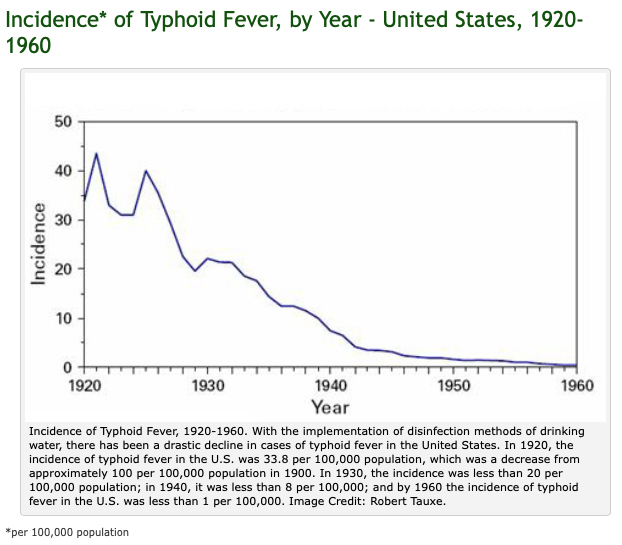

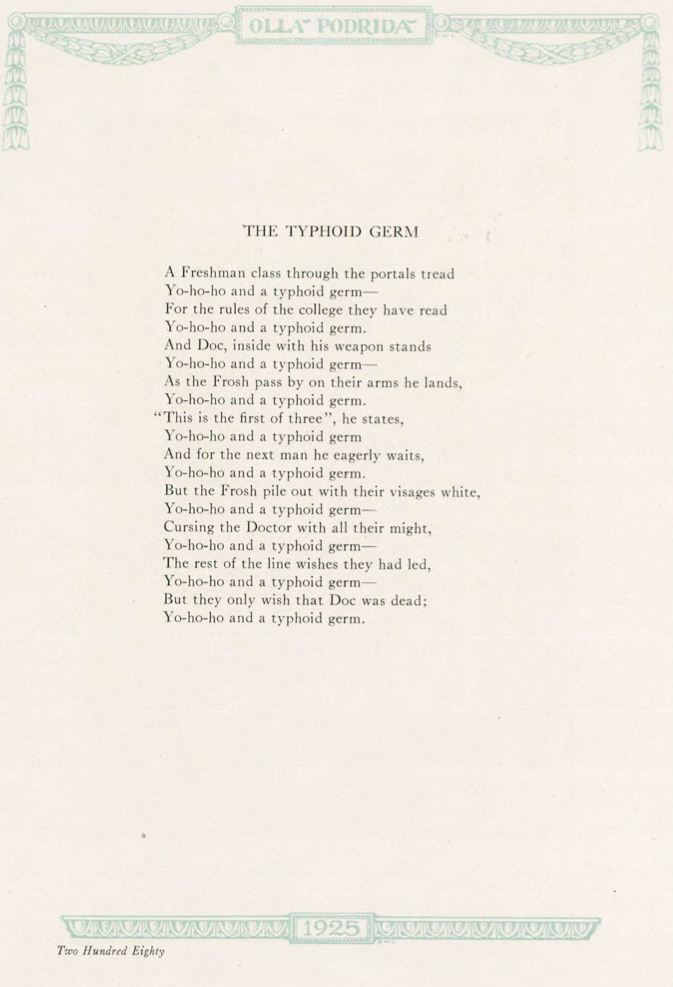

In the early 1900’s, Typhoid Fever was still a formidable disease. Its presence in the United States was reflected in Harold’s senior year yearbook in a poem (below). Typhoid fever is no longer a household word in America. However, during Harold’s school years, the disease frequently broke out in epidemic form. [1] The disease is characterized by a persistently high fever, rash, generalized pains, headache and severe abdominal discomfort that can lead to intestinal bleeding and even death. Ten percent of those who got the disease a century ago died.

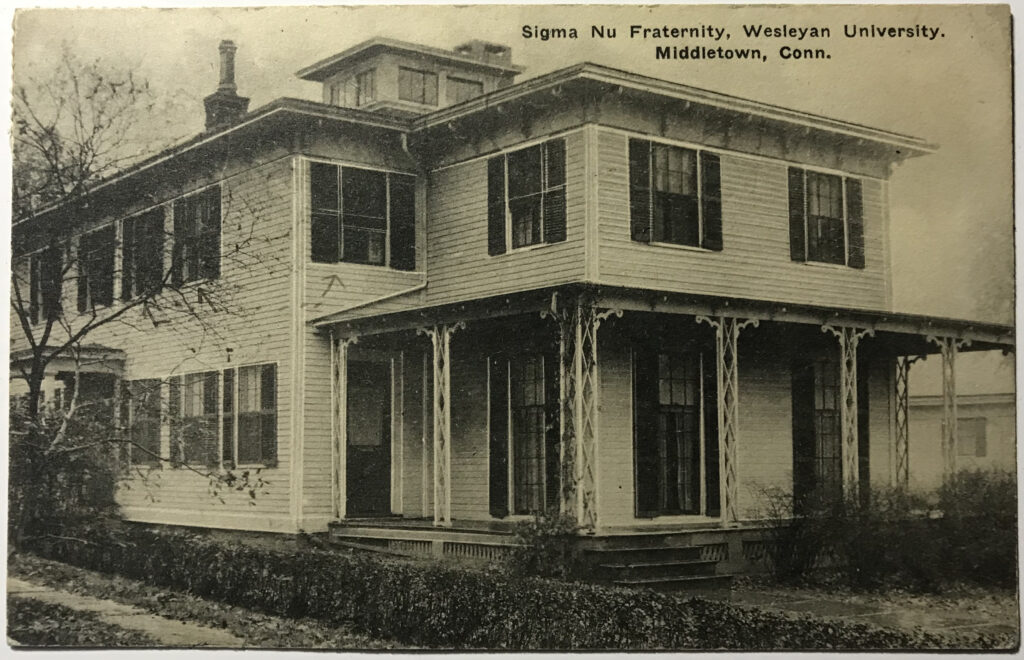

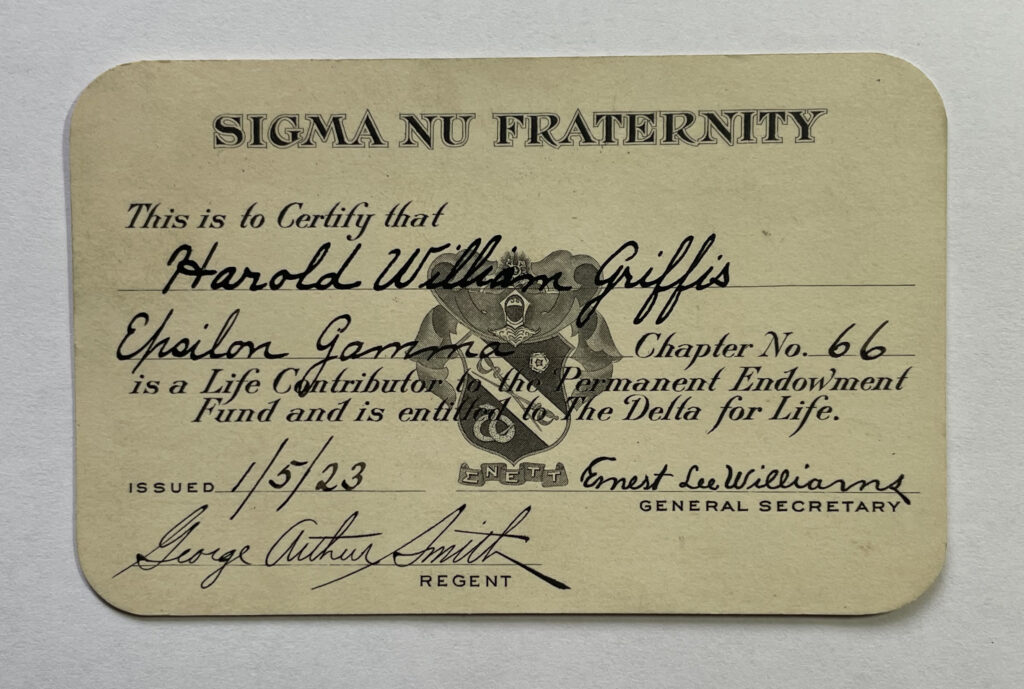

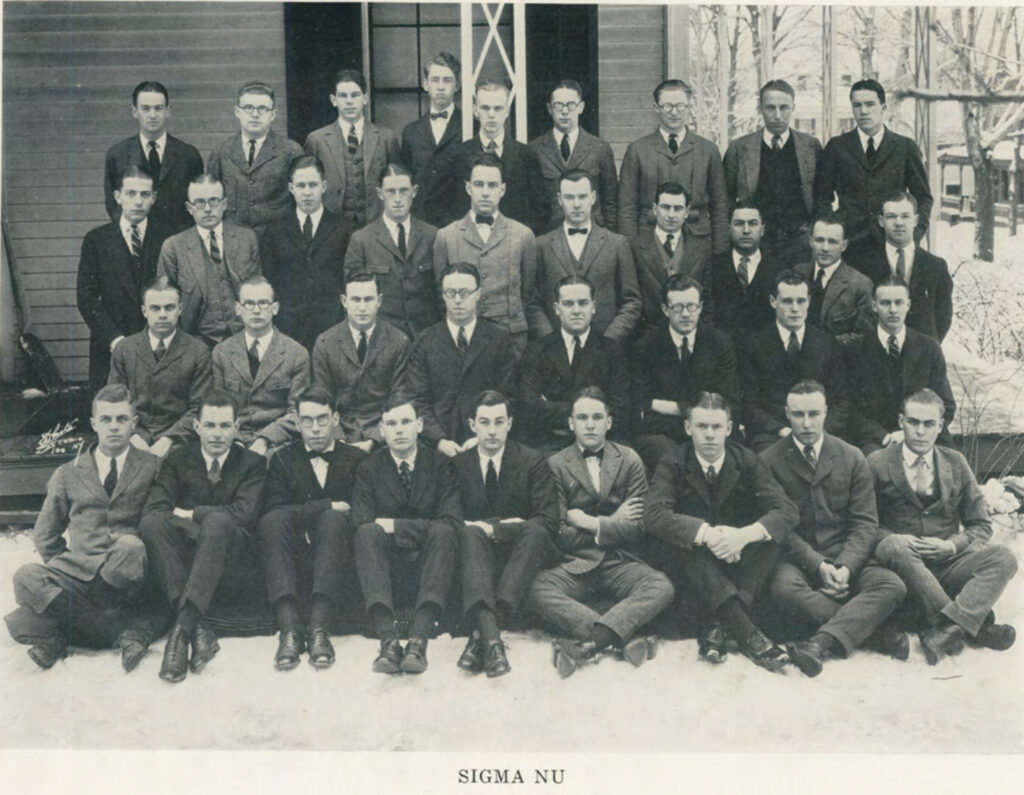

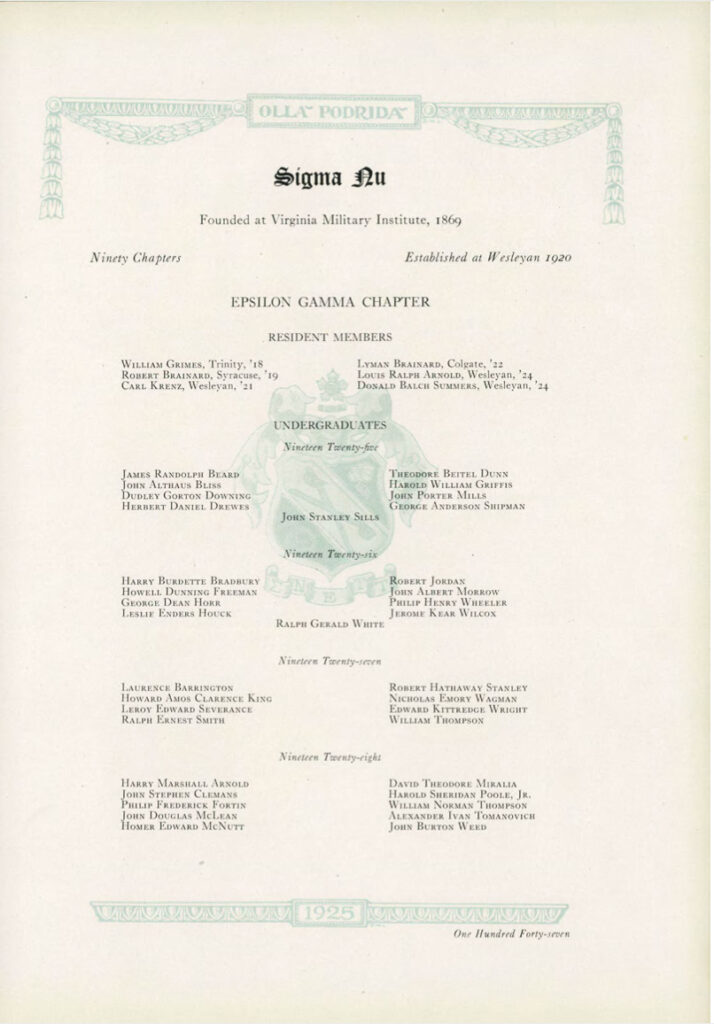

Sigma Nu Fraternity

Harold, as with many of the Wesleyan University students joined a Fraternity during his four year stay at college. He joined the Sigma Nu Fraternity which had recently established a local chapter at Wesleyan in 1920. Each fraternity had their group personality: some were party goers, others were the athletes of the college, and others were scholars.

Sigma Nu (ΣΝ) is an undergraduate college fraternity founded at the Virginia Military Institute on January 1, 1869. The fraternity’s values are summarized as an adherence to the principles of love, honor, and truth. [2]

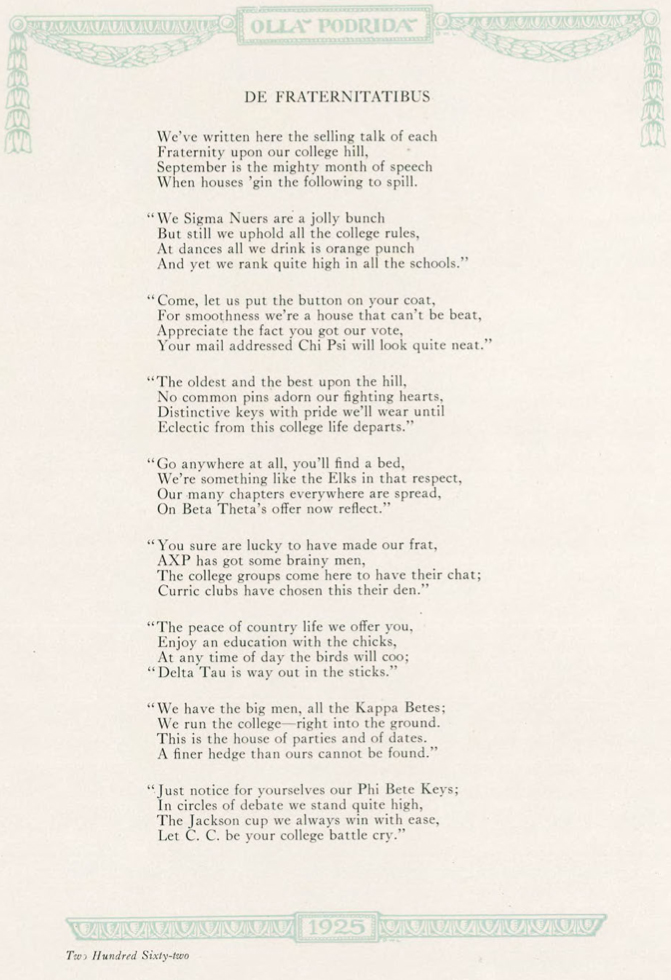

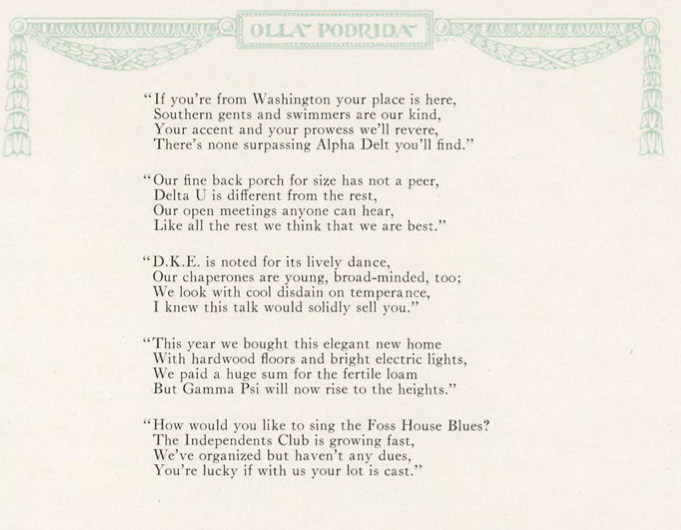

The Sigma Nu fraternity’s collective identity was captured in a poem, entitled De Fraternitatibus, in the 1925 Wesleyan University yearbook, Harold’s senior year. Evidently, the Sigma Nu boys were known to be tee totalers yet a happy bunch and stuck to college rules and received good grades.

It is interesting to note that the third last stanza of the poem describes the character of another fraternity DKE, Delta Kappa Epsilon. One of Harold’s sons, James Dutcher Griffis, also went to Wesleyan University. Given his personality as a gregarious, athletic, party-loving individual, much different than his father Harold, young James entered the DKE fraternity in the early 1950’s. It appears that the DKE house did not change since the early 1920’s. “They loved to dance, were broad minded in their views, and had a cool disdain on temperance”.

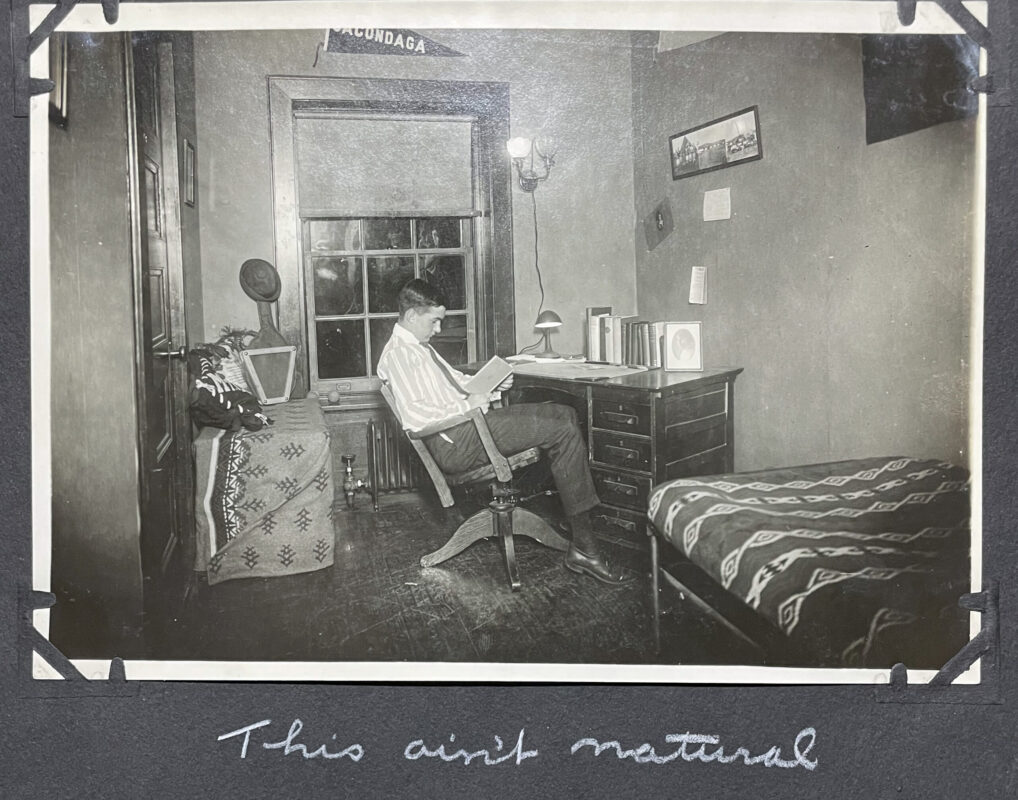

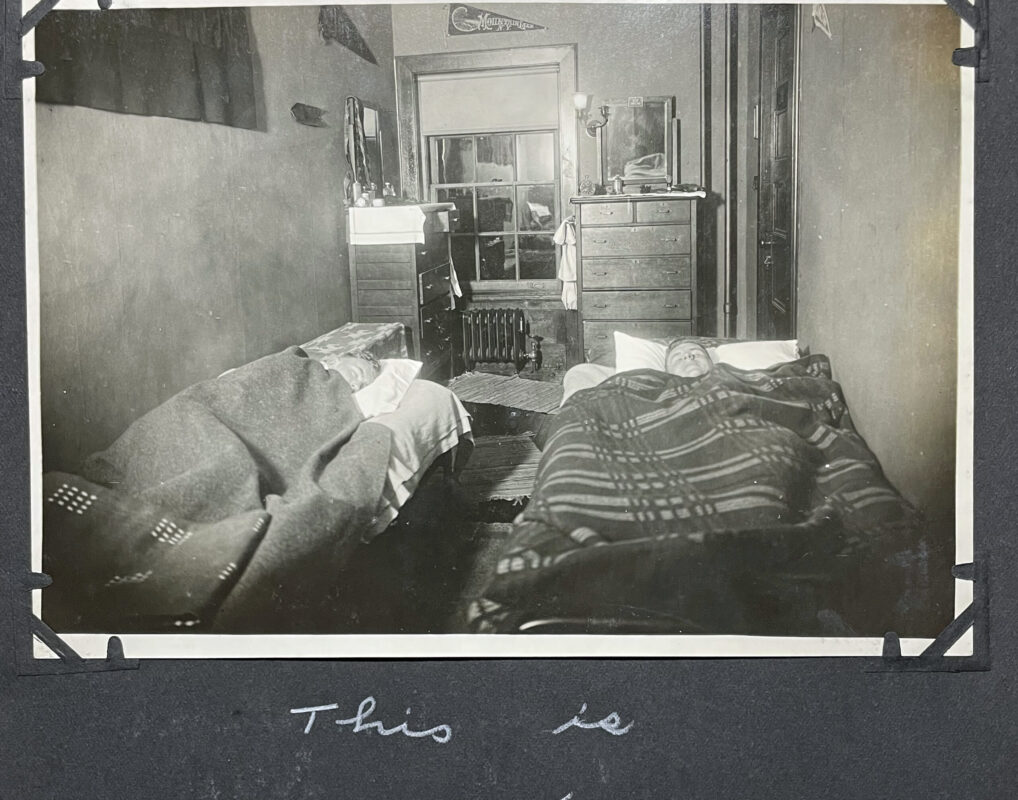

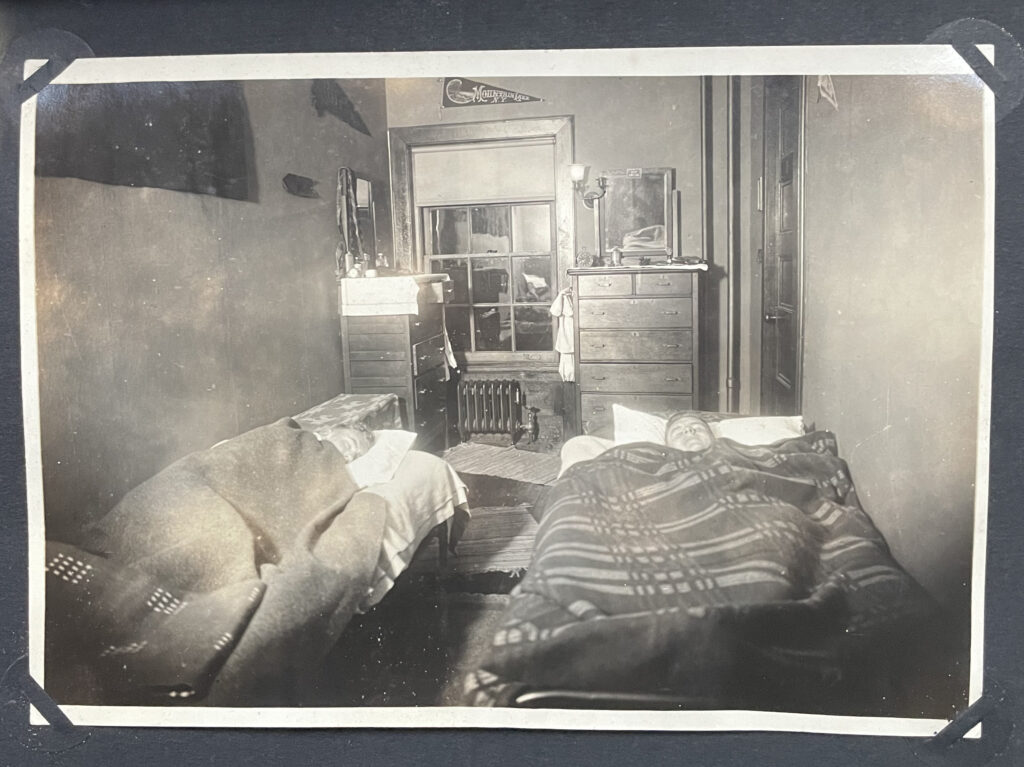

Below are photographs of Sigma Nu that were in a personal scrapbook compiled by Evelyn Dutcher, the photographs were taken around 1922.

College and Beyond

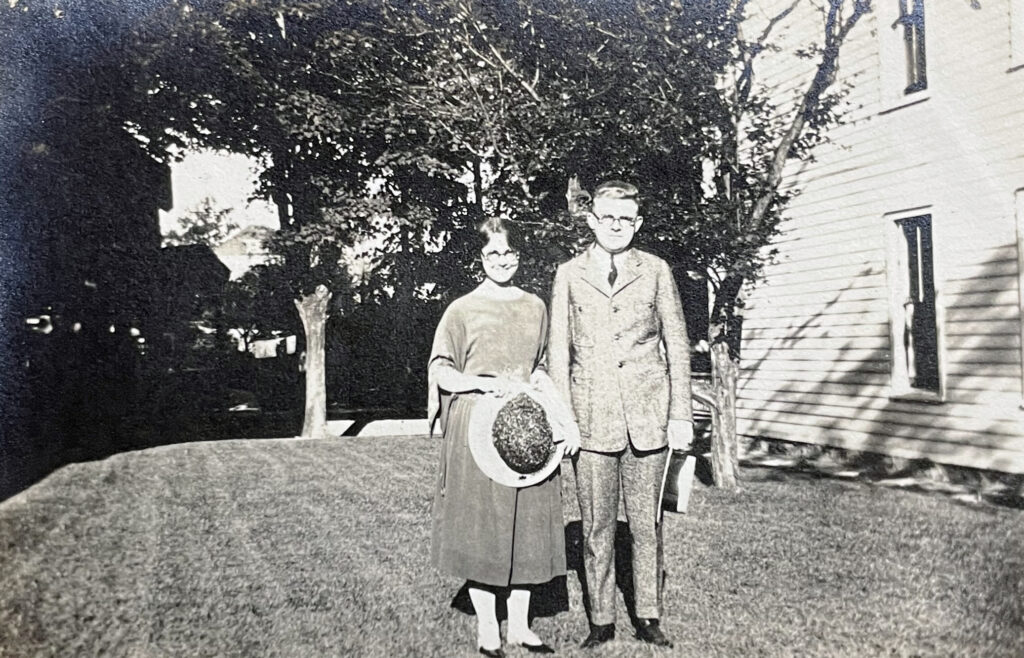

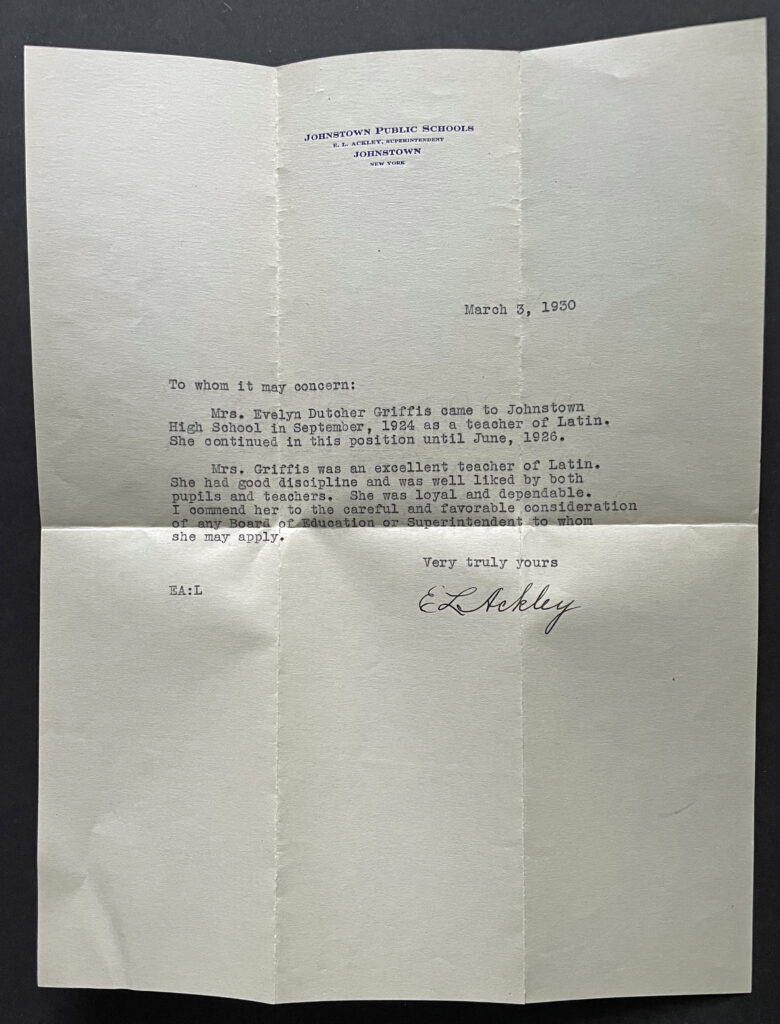

Harold and Evelyn began dating the last two years at Gloversville High School. Evelyn Dutch graduated from the New York State college for Teachers, Albany , New York in 1924. She went back to Gloversville and taught Latin at Johnstown High School for one year. [3]

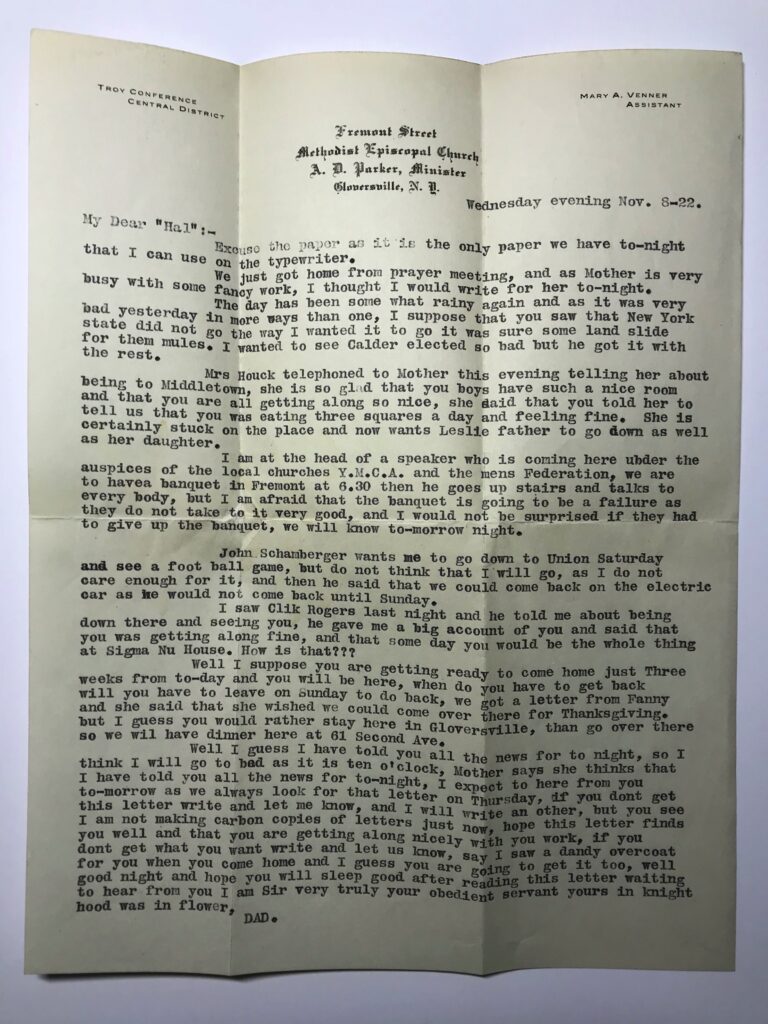

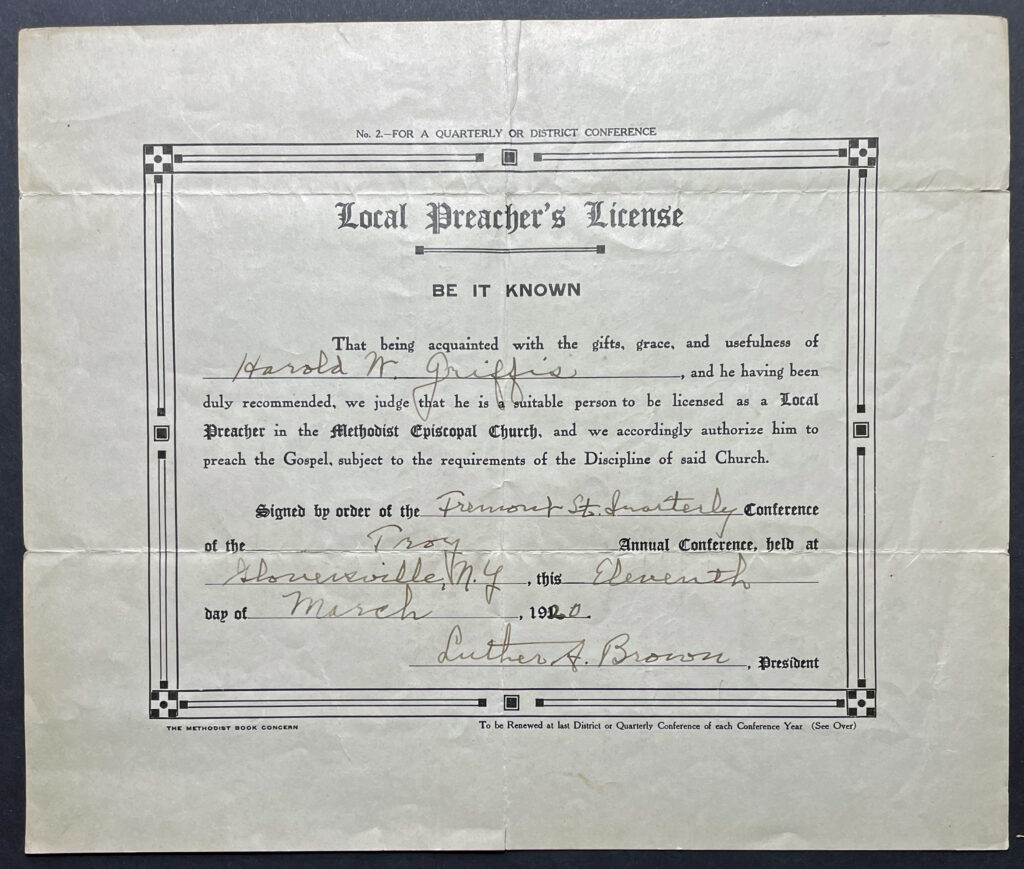

During his sophomore year at college, Harold applied to the Troy Annual Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church to be accepted and ordained as a Deacon. He obtained a Local Preacher’s License, signed by the Fremont Quarterly Conference of Troy Annual Conference, held in Gloversville March 11, 1920.

After Harold’s graduation, they were married on Harold’s birthday June 29, 1926. After their wedding, they immediately left for Harold’s pastoral duties initially at a church in Jonesville, New York. He then began his career as a pastor for the Methodist Episcopal Churches in Jonesville and Grooms, New York. His father Charles Griffis passed away on September 21, 1926.

1926 was a year of many milestones for young Harold and Evelyn: marriage, Harold starting his career as a pastor and the loss of his father’; for Evelyn, ending a brief teaching career after graduating from college and devoting her attention to her role as a pastor’s wife.

Photographs on their Wedding Day

Sources

The featured image is a panorama of all the students at Wesleyan University for the school year 1922-1923, from 1923 Olla Podrida, Annual College Yearbook, Wesleyan University, Middletown CT, 1923 , page 43. Harold Griffis was a sophomore. To view the entire photo click here.

[1] DiBacco, Thomas, When Typhoid was Dreaded, Washington Post, January 25, 1994

[2] Sigma Nu (ΣΝ) , Wikipedia, Page paced on 12 Feb 2021, was last updated 27 Nov 2020

[3] Letter of Recommendation from E. L Ackley, Superintendent, Johnstown Public schools, Johnstown, New York, March 3, 1930

Photograph sources:

- Dutcher, Evelyn, Personal scrapbooks

- Family photgraphs

- 1922 Yearbook, Olla Podrida, Middletown: Wesleyan University, 1922

- 1923 Yearbook, Olla Podrida, Middletown: Wesleyan University, 1923

- 1924 Yearbook, Olla Podrida, Middletown: Wesleyan University, 1924

- 1925 Yearbook, Olla Podrida, Middletown: Wesleyan University, 1925