Charles Tomlinson Griffes was one of Nathaniel Griffes’ great grandsons. Nathaniel was the sixth of 11 children of William Griffis (born 1736). Nathaniel introduced the unique spelling of the family name as Griffes which continued through his family line.

Although not a household name, Charles Tomlinson Griffes played an important role in the development of the American art song. Griffes possessed “a distinctive voice in American music”, and his song catalog, while moderate in size, demonstrated his “unique ability to fuse music and text” [9]. He suffered an untimely death, at the age of thirty-five, just as he reached the pinnacle of his career. [1] [2] [3] [16]

An art song is a vocal music composition, usually written for one voice with piano accompaniment, and usually in the classical art music tradition. [5].

At the turn of the 20th century, the American art song came of age. Serious composers from the United States began to break from the existing European traditions and develop their own unique style.

A near-contemporary of Charles Ives, Charles Griffes left a body of song ranging from “youthful German Romantic settings” to songs influenced by French Impressionism. Many of his mature songs, (especially Four Impressions, settings of Oscar Wilde) illustrate how Griffes wrote for the voice. His songs have been championed on record by Thomas Hampson [6].

Born on September 17th, 1884 in Elmira, New York, Griffes was the third of five children of Wilber Griffes and Clara Tomlinson. [15] When Charles was ten years old, he received his first piano lessons from his oldest sister, Katharine, who was herself a student of Mary Selena (Selina) Broughton. Miss Broughton was a piano teacher at Elmira College. At age fifteen, Griffes began his formal musical training with Miss Boughton. She also served as a mentor to the young Griffes. With her financial support, Griffes traveled to Berlin in 1903 to study music at the Stern Conservatory. Evidently, he was a brilliant piano student but felt more attracted to composition. [9] After two years at the Conservatory, Griffes studied briefly with Engelbert Humperdinck (the composer, not the singer). Griffes also continued his piano lessons in Europe with Gottfried Galston. [4]

In 1907, Griffes returned to America and became the director of music at the Hackley School for Boys in Tarrytown, New York. Although he purportedly did not intend the position to be permanent, Griffes served as director at the Hackley School for the remainder of his short life. At Hackley, Griffes was responsible for a variety of duties, including teaching piano and organ, directing the choir, performing in concerts, and accompanying guest artists at school functions. The position afforded Griffes a stable environment with a steady income, allowing him to dedicate his spare time to composition.

Around this time Griffes began to establish himself in American music circles. In 1909, Griffes’ work received its first publication when music publisher G. Schirmer printed five of his German Songs. By 1915, Griffes had a contract with Schirmer for the publication of six piano compositions (op. 5 and op. 6) and five English Songs for Voice and Piano (op. 3 and op. 4). [4]

Charles had begun, by this time, to drift away from” German romanticism and his compositions became more impressionistic” for the piano, including Three Tone-Pictures, op. 5 (1915), and Roman Sketches, op. 7 (1917). In 1916 and 1917, Griffes set five poems for voice and piano, using the five- and six-tone scales common in Eastern music rather than those associated with Western tonalities. Published as Five Poems of Ancient China and Japan, op. 10, they were premiered on November 1st, 1917 by Eva Gauthier, soprano, and Griffes, accompanying at the piano. Other Asian-influenced works by Griffes include Sho-jo, commissioned by Russian choreographer and dancer Adolf Bolm for the Ballet-Intime, and The Pleasure-Dome of Kubla Khan, initially scored for piano solo and later orchestrated. The latter composition did not receive its first performance in its original piano version until September 21, 1984 when pianist James Tocco played it in the Library of Congress’s Coolidge Auditorium. [1] [2] [3] [4] [9]

The year 1919 was, artistically speaking, the busiest year of Griffes’s life.

- Soprano Vera Janacopulos debuted Griffes’s Three Poems by Fiona Macleod, op. 11, on 22 March 1919 with the composer at the piano.

- The Modern Music Society featured a concert dedicated solely to Griffes’s music on 2 April 1919.

- The first performance of Griffes’s Poem for Flute and Orchestra occurred on 16 November 1919 by flutist Georges Barrère and the New York Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Walter Damrosch.

- Pierre Monteux conducted the Boston Symphony Orchestra in the first orchestral performances of The Pleasure-Dome of Kubla Khan on 28 and 29 November 1919; the orchestra repeated the performance in New York’s Carnegie Hall on 4 and 6 December.

- On 19 December 1919, Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra performed the orchestral debuts of Griffes’s Notturno für Orchester, The White Peacock, Clouds, and Bacchanale.

Griffes’s attendance at the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s performance of The Pleasure-Dome of Kubla Khan on December 4th, 1919 was his last public appearance.

Unable to afford editors or copyists, he had to correct proofs and prepare copies of his own large orchestral scores against the mounting deadlines that came with his emerging professional reputation. Perhaps due to his lifestyle, the burdens of trying to balance making a living and composing, he contracted influenza late in 1919. Over the next several weeks, intensifying fever, chronic weight loss, and growing fatigue finally brought about his collapse on December 4, 1919, just after a Carnegie Hall performance of his music. He was moved to the Loomis Sanatorium in upstate NY.

Having suffered from empyema for several months, Griffes succumbed to the disease on April 8, 1920 at the age of 35. He was buried on April 10th, and among the pallbearers at his funeral service was Oscar G. Sonneck, director of the publication department of G. Schirmer and former chief of the Music Division, Library of Congress.

He kept meticulous diaries, which provide a detailed history of musical life in New York City from 1907 to 1919. From them can be gleaned the slow, laborious journey from virtual invisibility to his first public successes in the last years of his life. Many of the diaries were destroyed by his sister after his death to prevent widespread knowledge of his being gay, his recreational New York life, his attraction to men in uniform, and his only long-term relationship (with a married policeman). [2] [12]

“His funeral was held in the Church of the Messiah, at Park Avenue and 34th St. in New York City. No music had been specified for the service. Unexpectedly, during the service, the sound of a Bach chorale entered the church. It came from the 71st Regiment armory across the street, where a music festival was in progress. Standing on the parapets of the armory building, a choir of trombonists played Griffes’s accidental requiem. The sight would have pleased him as well as the sound. They were all in uniform. The old Church of the Messiah was replaced by a new building in 1948. The present building now houses, among other things, rehearsals of the New York City Gay Men’s Chorus.” [12]

The amount and quality of his music is impressive considering his short life and his full-time teaching job, especially his twenty-six songs for piano and voice. Although famous for his orchestral compositions, his vocal works, such as Four Impressions and Three Poems by Fiona Macleod, established Griffes as one of America’s noted songwriters. [1][3][4][9] Much of his music is still performed. The following is an illustrative example of Charles Griffes compositions for Flute and Piano [10] [11] [13]

Sources

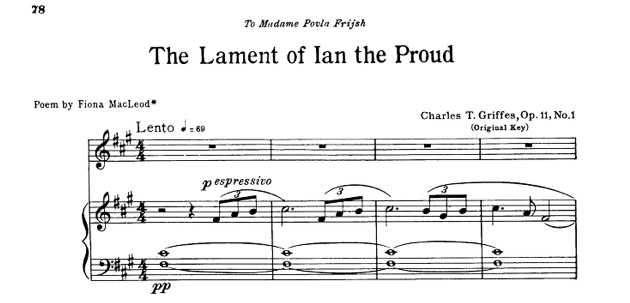

Featured Image at top of story: a copy of the first page of a musical composition, The Lament of Ian the Proud Music by Charles T Griffes and three Poems of Fiona MacLeod

[1] Anderson, Donna K. Charles T. Griffes: A Life in Music. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993.

[2] Maisel, Edward. Charles T. Griffes: The Life of an American Composer. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984.

[3] Upton, William Treat. “The Songs of Charles T. Griffes.” Musical Quarterly 9, no. 3 (July 1923): 314-28.

[4] Library of Congress Biographies: Charles Griffes

[5] Wikipedia, Definition of an Art Song

[6] American Art Song: An Overview, My Scena, Richard Turp 4 Sep 2018

[7] Dr. Amanda Cook, Between the Ledger Lines: A Blog for the Modern Flutist, Griffes: Poem Program Notes

[8] The Lament of Ian the Proud Music by Charles T Griffes and three Poems of Fiona MacLeod

[9] Bach Cantatas Website, Charles Tomlinson Griffes, contributed by Aryeh Oron, April, 2006

[10] Kile Smith, Impressions of Charles Tomlinson Griffes on Discovies from the Fleisher Collection, Radio Program, write.com 90.1, 11 Jan 2013

[11] Top Ten Compositions of Charles Tomlinson Griffes likley to be played, Concerty.com

[12] Find a Grave, Charles Tomlinson Griffes

[13] Musical Catelogue and Biography of Charles Tomlinson Griffes. Naxios Records

[14] U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, 1906-1907, Roll 019, Certificate 19829, 15 Sue 1906, image 503

[15] 1900 U.S. Federal Census, New york, Chemung County, Elmira Ward 03, district 0013, Page 16, Lines 69 – 76

[16] Charles Tomlinson Griffes, WikiVisually, Page accessed 14 Feb 2021

One Reply to “Charles Tomlinson Griffes – The American Art Song”

Comments are closed.