The families of both Harold Griffis and Evelyn Dutcher have a German influence. It is an influence that reflects a distinctive characteristic of the families of the Mohawk valley in New York state. German immigrants and their descendants made an indelible imprint on the Mohawk valley in New York since Colonial times.

“The Rhine and the Hudson ! The historic river of Europe and the historic river of America! How closely associated are they in the minds of those who dwell in the lovely valley in which we are met today !” [1]

The first European influence arrived in the early 1600’s with the arrival of the Dutch who promptly named all of the area to the north “New Netherlands”. They soon spread their influence up the Hudson River and west along the Mohawk River until 1664 when the British took over the Dutch lands and renamed them New York after the Duke of York.

In the early 1700’s, the Germans started to arrive and actually became the first permanent European settlers of today’s Mohawk valley. They and their Dutch neighbors tilled the rich soil of the region. This was literally a frontier area in flux between the Mohawk and European settlers.

Many of the initial settlements in the early 1700’s were created by German immigrants. While the Dutch, French and English occupied various colonial settlements on the fringe boundaries of the young colonies at various time periods, it was the German immigrants who created unique relationships with the Iroquois, particularly the Mohawk tribe, in establishing permanent settlements in the western territory of the New York colony. It was also the German immigrants who incurred substantial losses of property and life prior to and during the Revolutionary War while they lived in these settlements in the fringes of colonial controlled territory. [2]

In the late 1600s and early 1700s, the Germans took a different approach to dealing with the New York Indians than had the Dutch and English before them.

“The Dutch brought from Holland a traders sense of the world and viewed Indian villages as nodes on the paths of commerce. Because the Dutch wanted to control trade, not land, they did not need to occupy Indian villages. … The English, on the other hand, carried to America visions of extending the king’s dominion. They viewed New York as a battleground, a place to fight the French for domination of North America. The English could not possess New York without controlling the land.

“Just as the Dutch and English attitudes had been shaped by their European roots, the Germans’ attitude toward the Mohawks and the chaotic conditions of the Schoharie Valley may have been shaped by their experiences in the German southwest. Perhaps the Germans, coming from an area subject to continual invasion and to ever-changing rulers, had replaced a worldview consisting of conqueror and conquered with one of constantly changing allies and enemies, in which power was never absolute and always short-lived. Since conquest was an illusion, one sought allies who might help secure short-term gains. The Indians could be enemies or allies; the Germans needed the latter.” [3]

Harold and Evelyn’s German Family Ties

The relationships among European settlers and the Indians in the early colonial and post Revolutionary War period in the upper New York area is reflected in the ethnic background of the family ties found in the respective family trees of Harold Griffis and Evelyn Dutcher.

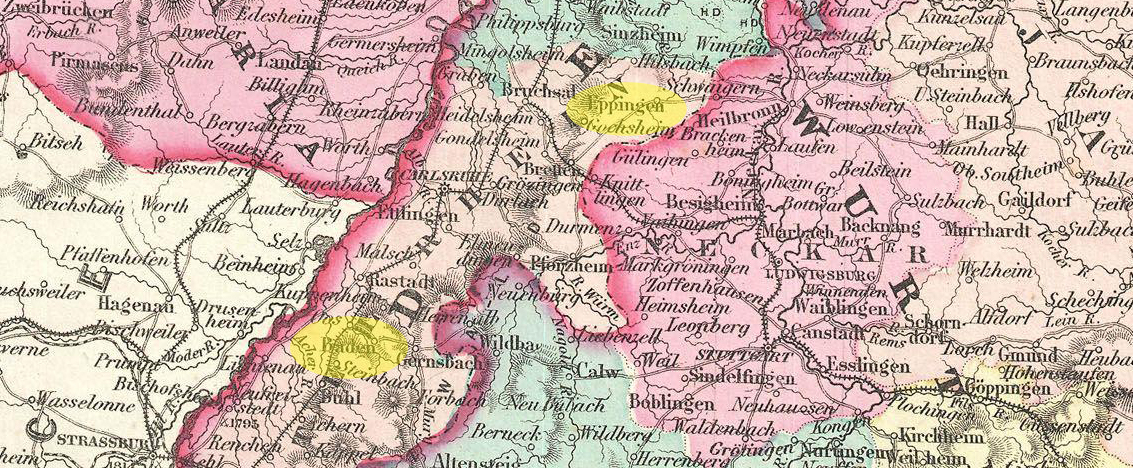

Some of the earliest emigrants to America came from the state of Württemberg, Germany. It is the area of Germany from which the number of emigrants surpassed any other German state. It is also the area where Harold and Evelyn’s German ancestors started their journey to America. [4]

Family Tree Branches with a Germanic Influence

Click here to see the family trees for Griffis family branches that are from German areas of Europe. Each family tree provides a context of their place in the general family tree for Harold Griffis and Evelyn Dutcher Griffis. Only grandparents and direct siblings are shown in the family trees.

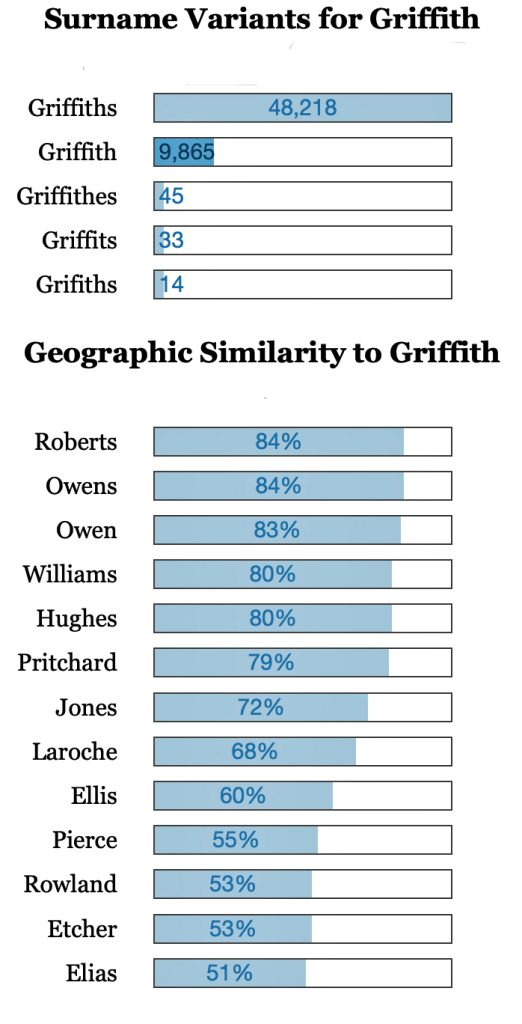

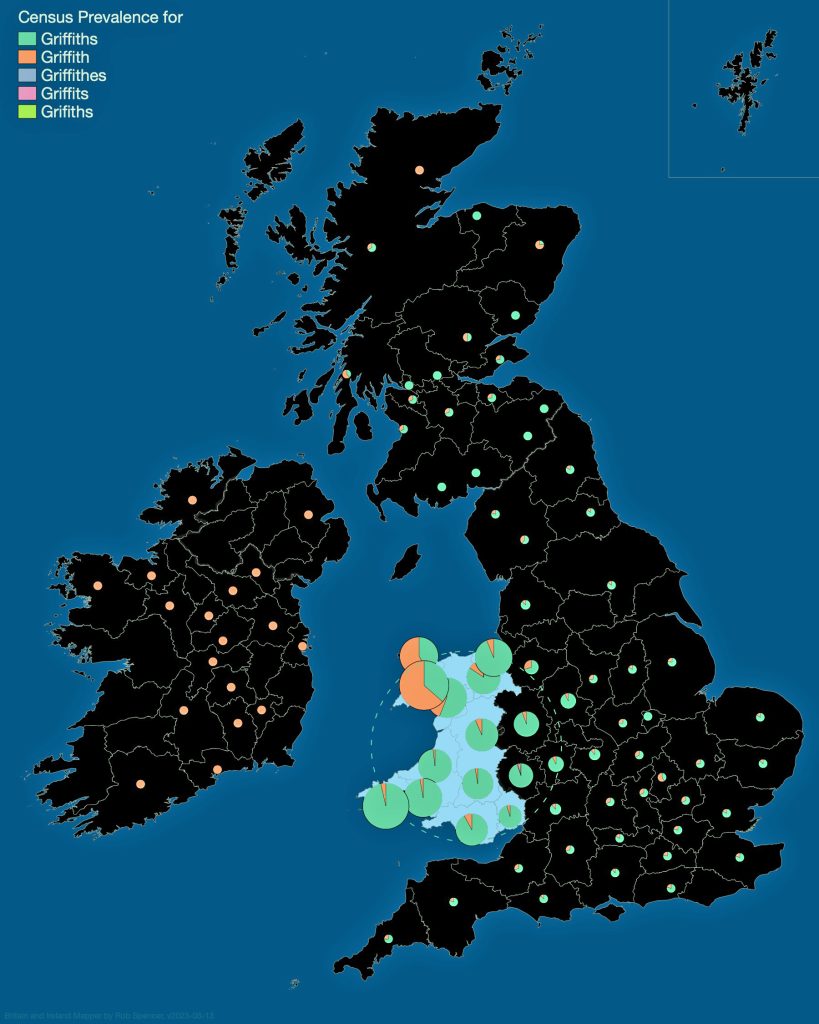

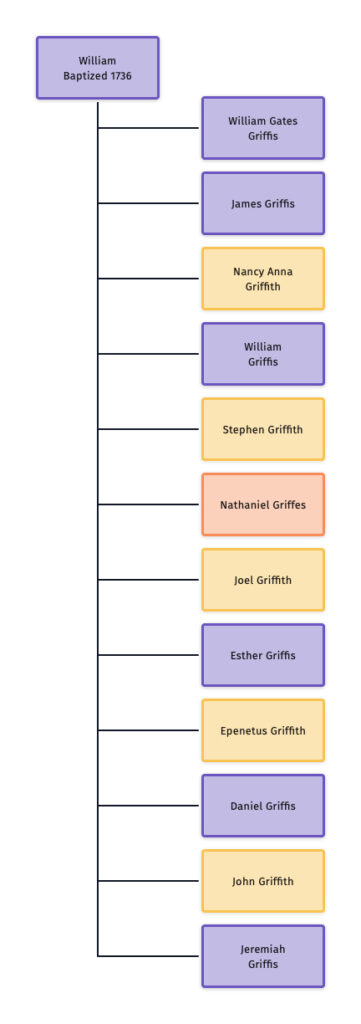

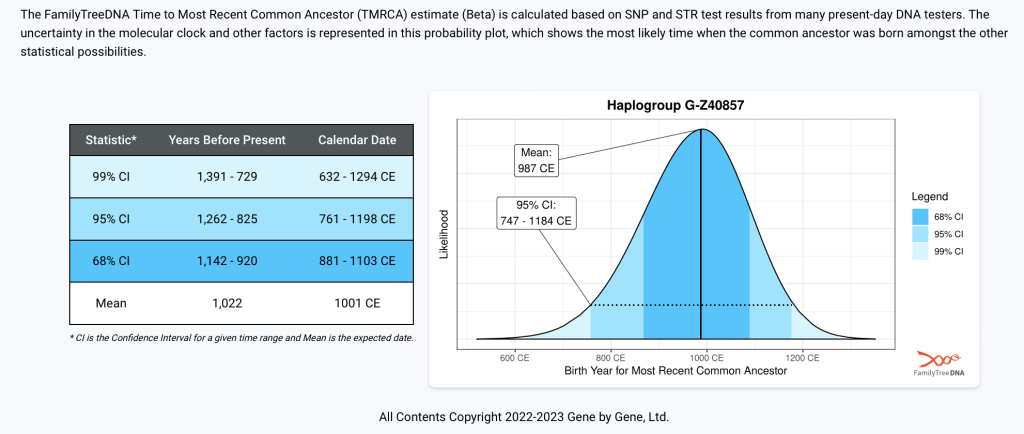

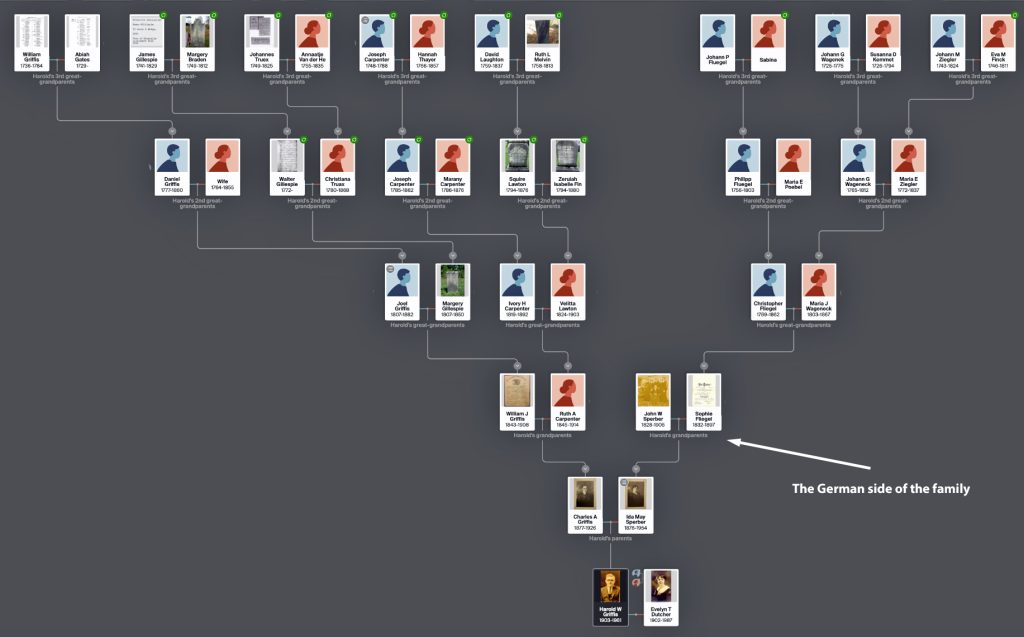

On Harold’s side of the family, the Sperber family and the Fliegel Family were immediate branches of the family that emigrated in the mid 1800’s from the Baden Würtemberg area [5] to the United States. While we do not know much about the Sperber family prior to their arrival in America, the Fliegel family can be traced back many generations to the Ittlingen, Germany area. Both families are maternal family branches of the Griffis family. Harold Griffis’ mother was Ida May Sperber. Ida Sperber was youngest child of John Wolfgang Sperber and Sophia Fliegels’ children. The immediate paternal side of Harold’s family reflect a Welsh (Griffis surname), English (Carpenter), and Scots-Irish background (Gillespie).

The German Side of the Griffis Family [6]

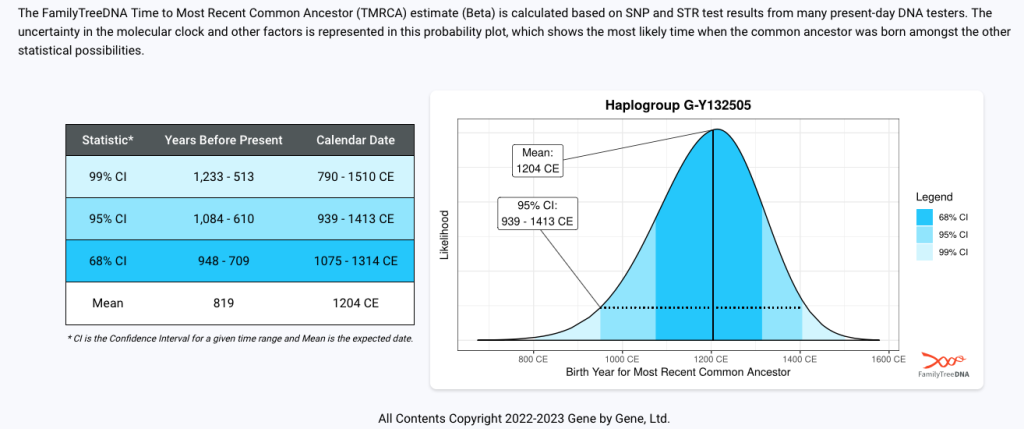

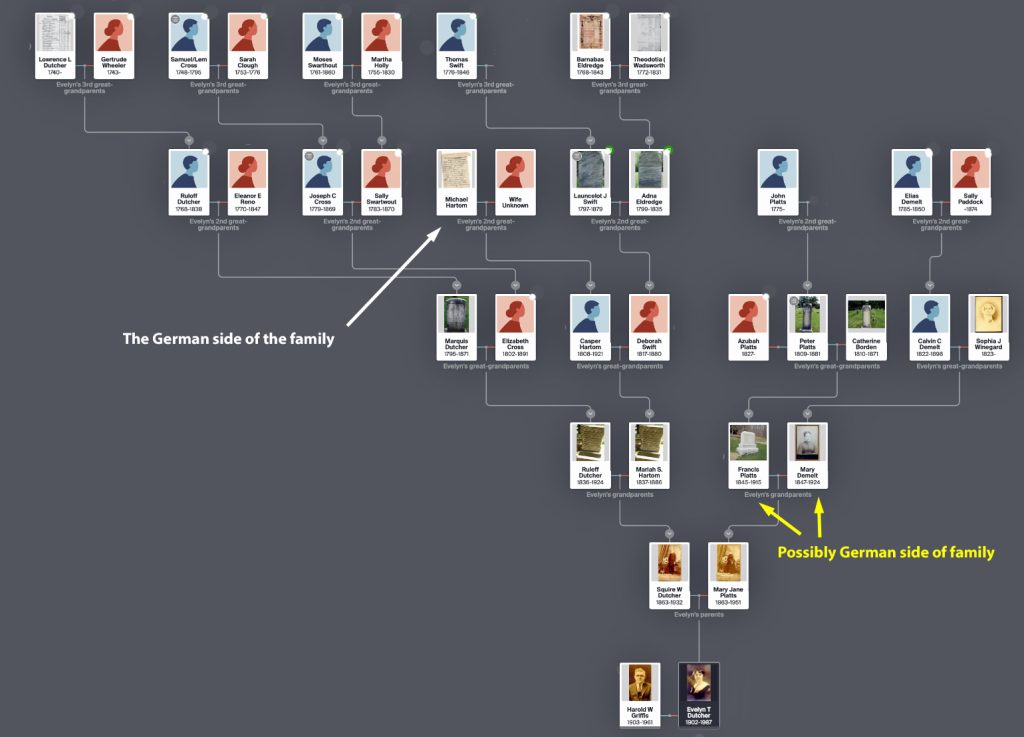

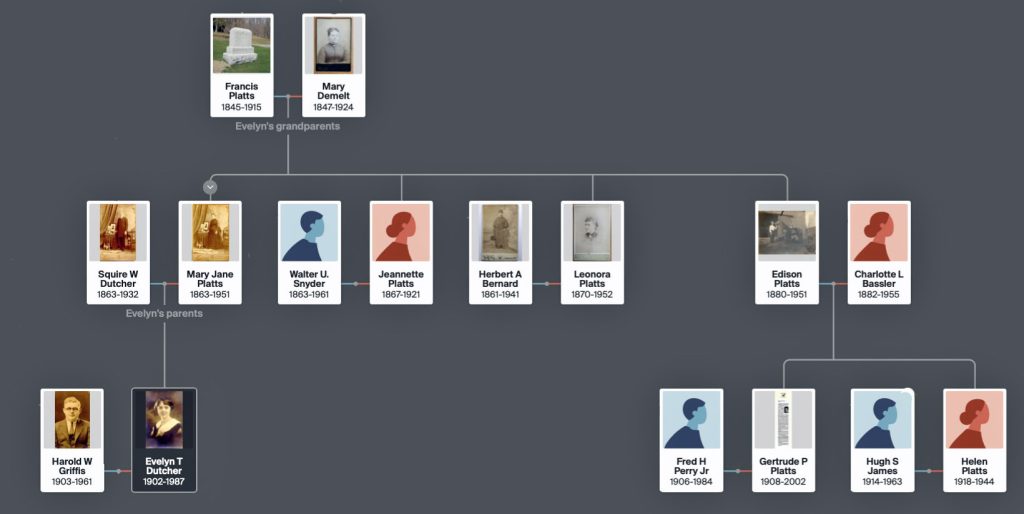

Similar to Harold’s family, Evelyn Dutcher’s family tree reflects the interaction of various ethnic backgrounds representing the mix of early European settlers in the New York colony. Her family represents Dutch, French, German and English ancestry.

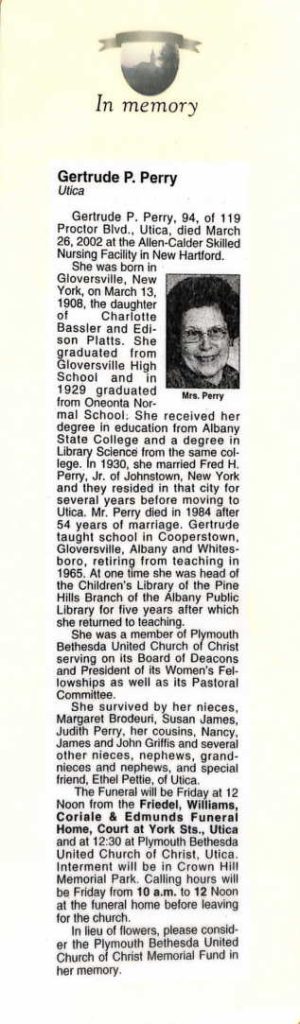

In fact, there is family lore that one of Evelyn’s female ancestors was from the Mohawk tribe. My father often mentioned the existence of this relative but had no specific documented knowledge about this relative. Based on conversations between Nancy Griffis and one of Evelyn’s cousins, Gertrude Platts Perry, it was indicated that Gertrude had old photographs that depicted the female family member that was from the Mohawk tribe. [7] If her recollections were true, then the individual possibly married a Platts family member. A review of available documentation on the Platts family offers no clue of an individual who had Mohawk descent. But, if there was a Mohawk member of the family, her name probably would have been an anglicized name in any documented records.

Evelyn’s surname, Dutcher, can be traced back to Dutch colonists in the 1600’s. The name is found with many spellings in the 1600’s: Duyster, Duyscher, Duchier, De Duyster. The family was likely one of the persecuted French Huguenots who fled from France to Holland. The names De Dutchier and De Duyster are found throughout sixteenth century French records. [8]

The Hartom family was a branch of Evelyn Dutcher’s family that emigrated from Germany earlier in 1775 to the American colonies. Evelyn’s father was Squire Dutcher. Squire’s father, Ruleff Dutcher, married Maria Hartom. Casper Hartom was Maria’s father. Casper’s father, Michael Hartom, is the family member that emigrated to the colonies in 1775. It is not known what part of the Germanic area of Europe his family is from.

The German Side of the Dutcher Family

There are two other family branches of Evelyn Dutcher’s family that may be German. However, I do not have definitive proof of their Germanic origin in terms of ship manifest lists of family members that originally came to the American colonies to confirm their point of origin. In addition, the origin of the surnames for these two family branches are not unique to one specific country or European region.

One of the family branches is the Demelt family. There is a good chance that the Demelt family is from Germanic origins. The family name, Demelt, was first found in Bavaria, where this surname surfaced in mediaeval times. [9]

The second family branch is the Platts family. Evelyn’s maternal side of the family included the Platts. It was originally presumed the Platts are of English origin. However, given where they settled and the name may have been an anglicized version of the German “Platz”, it is possible they were German. [10] There is no documentation to determine the ethnic origin of the Platts side of the family.

German Emigration to the Colonies & the United States

The reasons for emigrating to the new world for each of these families or individuals is perhaps unique but their respective decisions to leave their homeland were influenced by a larger economic and political landscape which provided a number of push and pull factors that influenced their decision. In addition, where they landed in the new world and where they subsequently traveled to put a stake in their new homeland were influenced by the paths of previous German immigrants.

At each successive wave, newcomers joined established settlers. This phenomenon of “chain migration” strengthened the already existing German regions in the American colonies and, later, the United States. Large sections of Pennsylvania, upstate New York, and the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia attracted multiple generations and successive waves of German emigration. [11]

Michael Hartom emigrated to the American Colonies in 1775. He was not part of the first wave of Germans to immigrate to the colonies but he closely followed the migratory path of the Palantines that represented the first major wave of Germanic immigration.

John Sperber and the Fliegel family emigrated in the mid 1850’s to a young new nation. Both were part of a major second wave of German immigration.

Germany in the 1600’s through the 1800’s

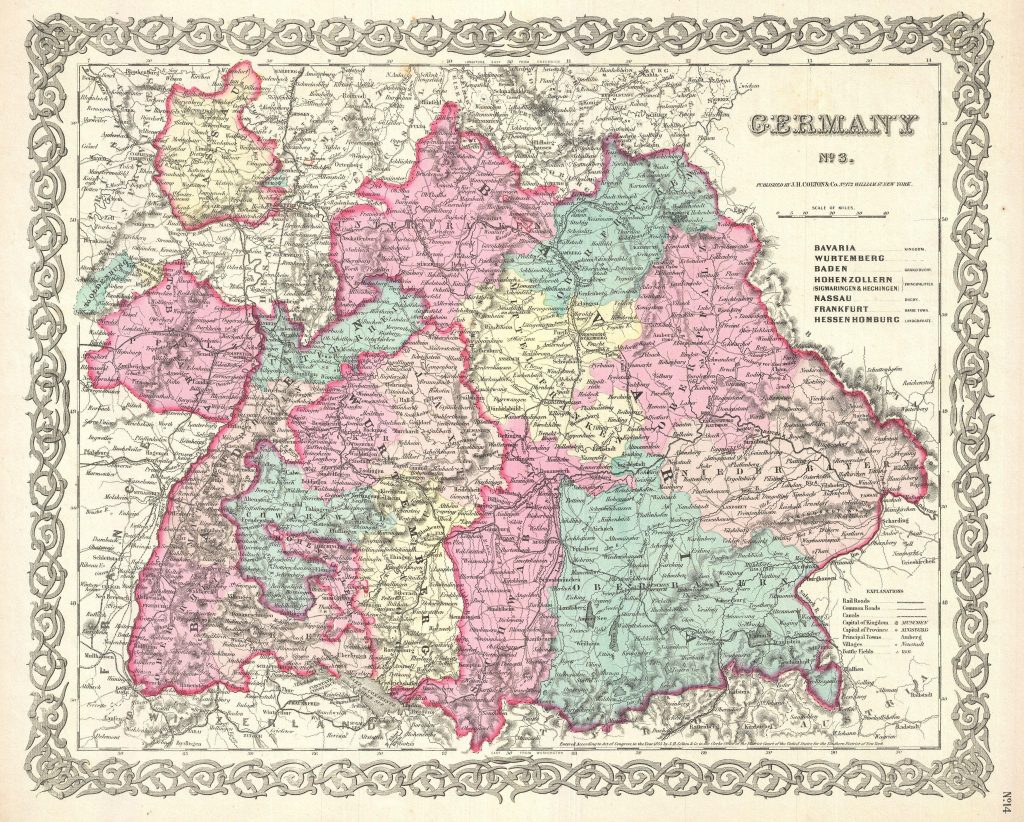

There was no unified “Germany” in the time period when the Hartom, Sperber, and Fliegel families emigrated to the Colonies and later to the United States. The European region that is currently Germany was divided into principalities and remnants of the Holy Roman Empire. Between the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) and the French Revolution (1789-1799), German geography was largely reflected by the histories of dozens of small political units, each enjoying virtually full rights of sovereignty. Political power increasingly fell to small regional governments controlled by aristocratic overlords, ecclesiastical dignitaries, or municipal oligarchs. [12]

Among the most powerful of these principalities was Prussia, led beginning in 1740 by King Frederick II, known as “Frederick the Great.” Under Frederick, Prussia expanded its territory to include parts of modern-day Austria and Poland. It would be almost a century before Germany was unified into the country we know today. Germany, or more exactly the old Holy Roman Empire, in the 18th century entered a period of decline that would finally lead to the dissolution of the Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. [13]

The following map reflects the political contours of the German states around the time that Michael Harton immigrated to the American Colonies in 1775.

Map of German States 1789 [14]

About 75 years later when the Sperber and Fliegel families emigrated to the United States, the German States had a similar yet different configuration. The Sperber and Fliegel families were from the Baden area of the map, an area located in the southwestern area of the empire next to the Kingdom of France along the Rhine River..

Map of German States 1815 – 1865 [15]

The immigrants from these geographic areas were referred to as German. However, ‘within’ the Germanic umbrella of ethnic identity as viewed by the English, Dutch, French, or Indians, they were Palatines, Badeners and Hessians. The Germans included many quite distinct subgroups with differing religious and cultural values. The making of a German and American identity was one of immigrants not just defining themselves in contrast to a British, French, Dutch, or Iroquois “other” group but also first defining themselves in contrast to many German “others”. [16]

Various Waves of German Immigration

German immigration to North America began in the 17th century and continued into the late 19th century at a rate exceeding that of any other country.

The Germans migrated to America for a variety of reasons depending on the specific historical time period. Push factors involved the effects of the continuous wars and conflicts, worsening opportunities for farm ownership in central Europe, persecution of some religious groups, and military conscription. Pull factors were better economic conditions, the opportunity to own land or earn a better wage, and religious freedom.

Germany also experienced unfavorable weather conditions in the 1800’s that brought about food crises. Lack of food brought about elevation of prices. With a continually increasing population, some areas experienced devastation. When sons were not able to inherit the ancestral farm to support themselves and their families, emigration was one way out.

German emigration to the American colonies began at the end of the 17th century when Germany was suffering from the after-effects of the bloody religious conflicts of the Thirty Years’ War and Christian minorities were being persecuted. Many farmers lived in poverty, their very existence threatened by failed harvests and land shortages.

German immigrants in the initial wave came from the states of Pfalz, Baden, Wuerttemberg, Hesse, and the bishoprics of Cologne, Osnabruck, Muenster, and Mainz. Working with William Penn, Franz Daniel Pastorius established “Germantown” near Philadelphia in 1683. A group of Mennonites, Pietists, and Quakers in Frankfurt, including Abraham op den Graeff , a cousin of William Penn, approached Pastorius about acting as their agent to purchase land in Pennsylvania for a settlement. Pastorius arrived in Philadelphia on August 20th, 1683. In Philadelphia, he negotiated the purchase of 15,000 acres from William Penn, the proprietor of the colony, and laid out the settlement of Germantown. [17]

European Migration to Britain in the 1700s

The initial wave of Germans to the colonies is often referenced as ‘the story of the Palantines” [18]. The Germans that eventually settled the Mohawk Valley came from the Rhine Valley River region known as the “Palatinate.” The name arose from the Roman word “Palatine,” the title given to the ruling family of the area when it was part of the Holy Roman Empire. With the outbreak of the Thirty Years War in 1618, came 96 years of sporadic fighting and wars that would leave the Palatinate destroyed. This forced thousands of Germans to flee their homeland, many who made the American colonies (before the revolution) and the United States (after the revolution) their new home.

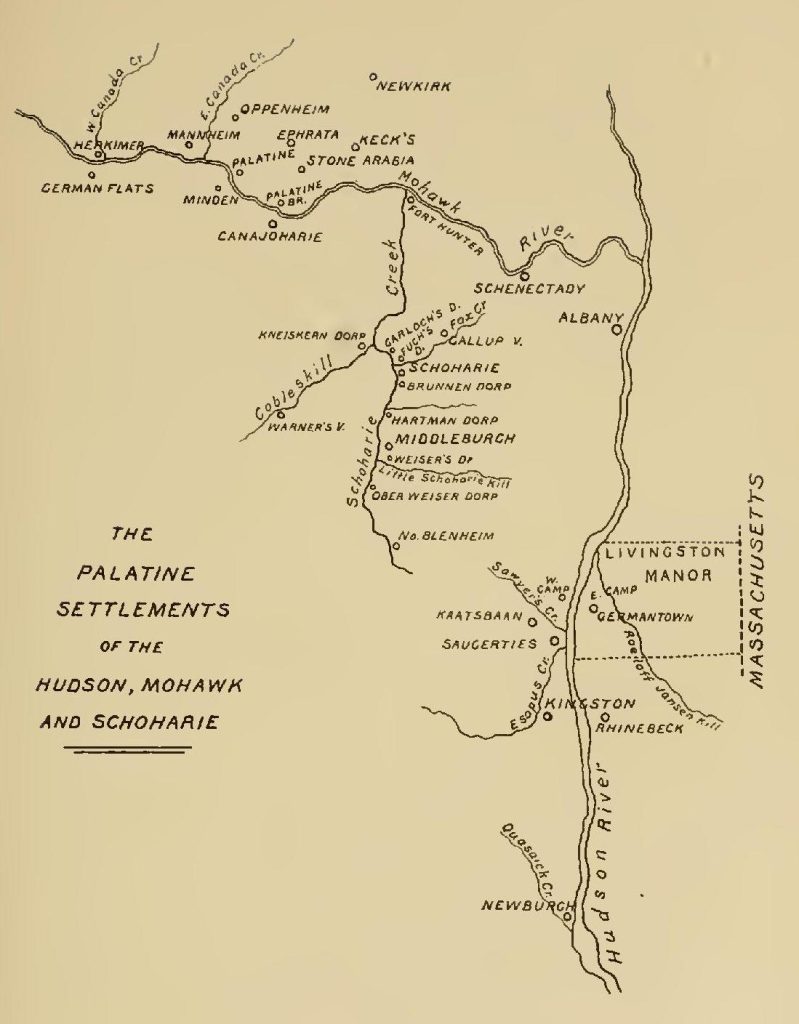

The movement of the initial wave of German immigrants, the so-called Palantines, was the result of the British government sending roughly 3,000 German immigrants in the early 1700’s to the colonies after they initially immigrated to England on rumors that Britain would provide passage to the American Colonies. In a quandry as to what to do with these German immigrants, the immigrants were sent by the English to the colonies on the proviso that they would be indentured laborers for the production of ‘naval stores’ (the production of tar and pitch in the pine forests of the Hudson valley). Once they got to the colonies, they refused to such an agreement and the English did not enforce their original contract. As a result the German immigrants settled on the Hudson River, some moved to New York City and New Jersey and others settled to scarcely settled areas of the New York frontier. [19] Many of these ‘scarcely settled’ areas would be areas that Griffis family branches would settle in the Mohawk valley.

Early German Settlements in the New York Colony

Source: Sanford H. Cobb, The Story of the Palatines: An Episode in Colonial History, New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1897, The Palatine Settlements of the Hudson, Mohawk, and Schoharie, Page 148 https://ia800906.us.archive.org/3/items/storyofpalatines01cobb/storyofpalatines01cobb.pdf

By the middle of the 18th century, German immigrants occupied a central place in American life. Germans accounted for one-third of the population of the American colonies, and were second in number only to the English. [20] Wars in Europe and America had slowed the arrival of immigrants for several decades starting in the 1770’s. By the year 1800, 100,000 Germans had migrated to the United States, and over eight percent of the American population was of German descent. The trend started to reverse and German immigration increased tenfold by 1830. [21]

“From that year until World War I, almost 90 percent of all German emigrants chose the United States as their destination. Once established in their new home, these settlers wrote to family and friends in Europe describing the opportunities available in the U.S. These letters were circulated in German newspapers and books, prompting “chain migrations.” By 1832, more than 10,000 immigrants arrived in the U.S. from Germany. By 1854, that number had jumped to nearly 200,000 immigrants.” [22]

For the typical working people in Germany, who were forced to endure land seizures, unemployment, increased competition from British goods, and the repercussions of the failed German Revolution of 1848, the economic and political prospects in the United States seemed bright. It also soon became easier to leave Germany, as restrictions on emigration were eased.

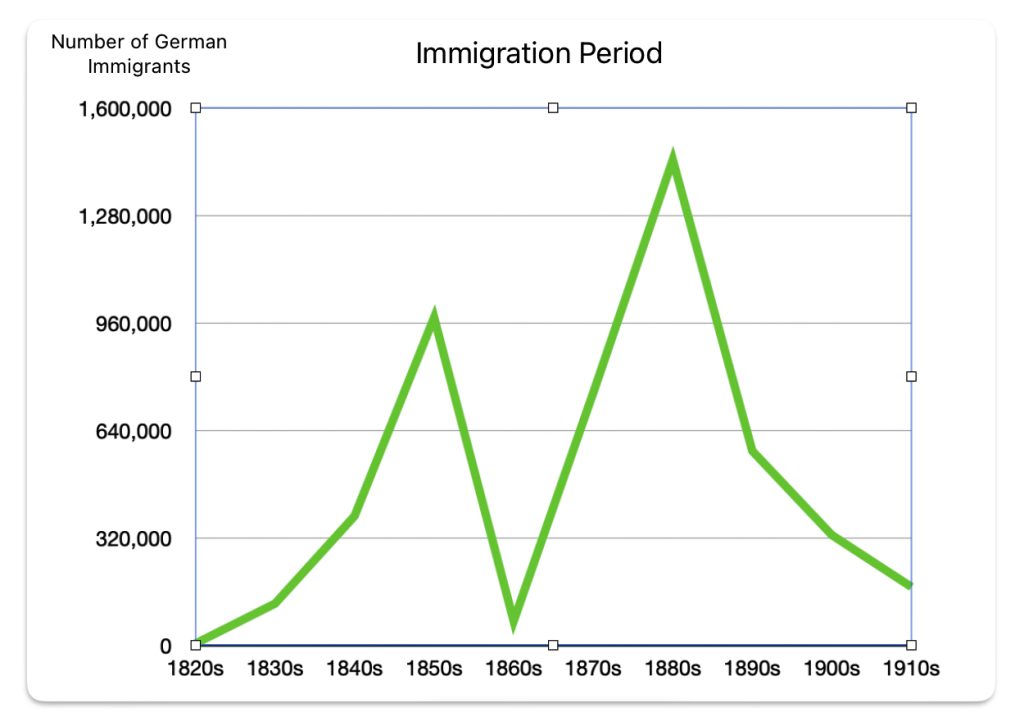

Nearly one million German immigrants entered the United States in the 1850s; this included thousands of refugees from the 1848 revolutions in Europe. As reflected in the table below, there were to major peaks in German immigration between 1820 and 1920. The 1850’s and the 1880’s witnessed the latest influx of immigrants from Germanic areas in Europe.

It was during the first of the two major waves in the 1800’s that John Sperber and the Fliegel family migrated to the United States. Nearly one million German immigrants entered the United States in the 1850’s. The German immigrants arriving in the 1850’s represented almost 18 percent of the total number of German immigrants arriving to the United States between this one hundred year period. In the 1850’s German immigrants represented a little over a third of all immigrants coming to the United States. [23]

Table One: German Immigration to the United States (1820-1920) [24]

| Immigration Period | Number of Immigrants | % of Total German Migration | % of U.S. Total Migration By decade |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1820-1830 | 5,753 | 0.1% | 4.5% |

| 1831-1840 | 124,726 | 2.3 | 23.2 |

| 1841-1850 | 353,434 | 7.0 | 27.0 |

| 1851-1860 | 976,072 | 17.8 | 34.7 |

| 1861-1870 | 72,734 | 13.2 | 34.8 |

| 1871-1880 | 751,769 | 13.6 | 27.4 |

| 1881-1890 | 1,445,181 | 26.4 | 27.5 |

| 1891-1900 | 579,072 | 10.5 | 15.7 |

| 1901-1910 | 328,722 | 5.9 | 4.0 |

| 1911-1920 | 174,227 | 3.2 | 2.8 |

| Total | 5,494,690 | 100.00 |

The graph below depicts the two major waves of German immigrants within this one hundred year period.

The area that John Sperber and the Fliegel family left the German territories were particularly affected by the mass exodus to the United States.

Censuses have been taken in Germany at regular intervals since 1816. In most of the German states, including Prussia, they were taken every three years. Within the territory of pre-war Germany between 1840 and – 1910, the German population doubled in size. The increase however was due mainly to higher fertility rates and was not attributable to people moving into the German territory. In fact, there was an appreciable exodus of German’s moving out of the area which mitigated population growth in Germany. Germany lost about 5 million due to people moving out of the German territories. [25]

“The net loss through emigration was especially large between 1847 and 1855, when crop failure and famine impaired living conditions among a population still mainly agricultural. Political discontent and ferment also quickened the migratory impulse. in the three years, 1853-55, almost half a million people…left Germany annually. These losses through migration had the more harmful effect on the growth of population, since the mortality also increased, so that periods with the greatest losses through migration were also periods with the smallest excess of births.

“Between 1853-55, almost three quarters of the natural population increase was lost through migration. … In some parts of German (Württemberg, Baden and the Palatinate) noted for their large emigration it became so heavy that the population decreased. In 1849-52, Wüttenberg suffered an annual loss of 11,000 people (2.2 per 1000) and in 1852-55, suffered an annual loss of 64,000 persons or 12.2 per 1000.

“In Baden, (an area where the Sperber and Fliegel families lived – my note) despite a large excess of births between 1847 and 1855, emigration caused a continuous decline in population. … . “ [26]

Getting to America: the German Experience in the 1700’s

In the 1700’s, the emigrants from the Baden Wüteenberg area usually gathered in a town close to the River Rhine and then took passage on the Rhine north to The Netherlands. From there they sailed to a colonial port. It took several weeks to reach an Atlantic seaport, and another eight to 10 weeks of demanding ocean travel before they reached the shores of North America. [27] This migration path resembles the path of Michael Hartom, Evelyn’s great great grandfather.

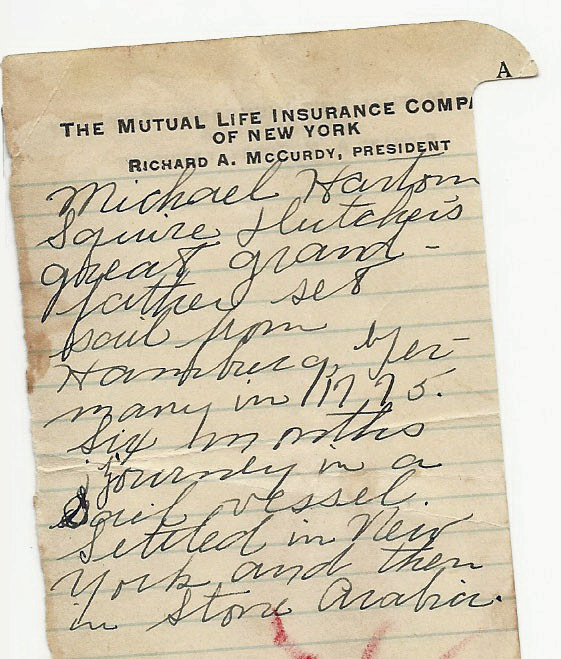

The handwritten note below appears to be a torn page from a small calendar notebook. Evelyn was interested in the genealogy of the Dutcher family and this was found in her notes. The note depicts an immigration path of the ‘second wave of Palatines‘ to the colonies.

“Michael Hartom Squire Dutcher’s great grandfather set sail from Hamburg, Germany in 1775. Six months journey in a sail vessel. Settled in New York and then in Stone Arabia.”.

I have researched a wide range of ship passenger lists from Europe between 1770 and 1800 but have yet to find Michael Hartom’s name on a ship manifest list. Discovering a passenger list with a name of a relative is often the result of chance and luck. Many ship manifests were not saved or documented. In addition, there is the inherent issue of what was written on paper.

Generally speaking the captains’ lists have the least value, as far as the spelling of the names is concerned. They were in most cases written by men who had no knowledge of German and to whom German surnames were a mystery they could not fathom. They wrote down the names as they were pronounced to them, spelling them as they would spell English names. As a result there are hundreds of names that have such fantastic forms that they are unrecognizable. [28]

The note written by Evelyn Dutcher Griffis indicates that it took Michael Hartom six months to reach America. This statement perhaps was overstated in terms of the actual length of the voyage. His entire journey from ‘home’ to New York City may have been six months.

In the days of sailing ships, crossing the Atlantic Ocean was certainly slow compared with modern times and frequently a dangerous experience. The overcrowded boats were at the mercy of the ocean and the weather, dependent upon the wind belts for propulsion. On a calm sea with little wind, the sails would hang useless and a trip across the ocean could take on average from one to three months. Disease was rampant in these crowded circumstances, with the ill and the healthy immigrant packed tightly together. Fatalities from disease and ships lost at sea were estimated to range from 10% to 15%. [29]

Prior to 1848, not only would immigrants have to load their own belongings, but families would be required to bring along food for the voyage. There was no one to advise the immigrants as to whether or not these rations would be adequate for the trip..

Poor immigrants often travelled to America on ships that were making their return voyage after having carried tobacco or cotton to Europe. The voyage took up to 90 days, oftentimes much longer, depending on the wind and weather. In steerage, ships were crowded, each passenger having about two square feet of space. The conditions were not sanitary, lice and rats were prevalent. Passengers were required to bring their food or were forced to procure food from the ship’s captain. The ventilation was poor. Between 10-20% of those who left Europe died on board. [30]

After the long and gruelling ocean voyage, most immigrants to the United States in the late 18th and early part of the 19th century made their way to rural areas to farm. Most immigrants in the mid-19th century remained in the ports where they had arrived except for those with the financial means for further travel.

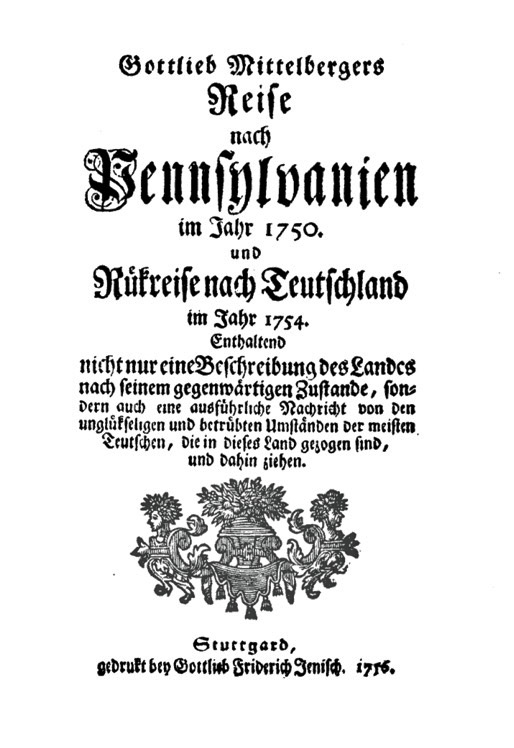

Gottlieb Mittelberger, an organ master and schoolmaster, who left one of the small German states in May 1750 , documented his experiences of sailing from the German territory to the colonies. Mittelberger had lost his job in the Duchy of Wurttemberg in the Holy Roman Empire. He sailed to Philadelphia and lived in colonial America for four years. Upon his return home he wrote a book, with the purpose to warn Germans of the hardships of emigration. [31]

Mittelberger indicates that the passage to America was long and treacherous. Due to delays in travel along the Rhine River and European ports, many of the immigrants would run out of funds and by the time they arrived in the American colonies, they were too poor to pay for the journey and therefore indentured themselves to wealthier colonialists, selling their services for a period of years in return for the price of the passage.

I have provided a number passages from his personal account:

“This journey lasts from the beginning of May to the end of October, fully half a year, amid such hardships as no one is able to describe adequately with their misery. The cause is because the Rhine boats from Heilbronn to Holland have to pass by 36 custom-houses, at all of which the ships are examined, which is done when it suits the convenience of the custom-house officials. In the meantime the ships with the people are detained long, so that the passengers have to spend much money. The trip down the Rhine alone lasts therefore 4, 5 and even 6 weeks. When the ships with the people come to Holland, they are detained there likewise 5 or 6 weeks. Because things are very dear there, the poor people have to spend nearly all they have during that time.” [32]

“Both in Rotterdam and in Amsterdam the people are packed densely, like herrings so to say, in the large sea-vessels. One person receives a place of scarcely 2 feet width and 6 feet length in the bedstead. “ [33]

“But during the voyage there is on board these ships terrible misery, stench, fumes, horror, vomiting, many kinds of sea-sickness, fever, dysentery, headache, heat, constipation, boils, scurvy, cancer, mouth-rot, and the like, all of which come from old and sharply salted food and meat, also from very bad and foul water, so that many die miserably. Add to this want of provisions, hunger, thirst, frost, heat, dampness, anxiety, want, afflictions and lamentations, together with other trouble, as c. v. the lice abound so frightfully, especially on sick people, that they can be scraped off the body. The misery reaches the climax when a gale rages for 2 or 3 nights and days, so that every one believes that the ship will go to the bottom with all human beings on board. In such a visitation the people cry and pray most piteously.” [34]

“Children from 1 to 7 years rarely survive the voyage; and many a time parents are compelled to see their children miserably suffer and die from hunger, thirst and sickness, and then to see them cast into the water. I witnessed such misery in no less than 32 children in our ship, all of whom were thrown into the sea.” [35]

“When the ships have landed at Philadelphia after their long voyage, no one is permitted to leave them except those who pay for their passage or can give good security ; the others, who cannot pay, must remain on board the ships till they are purchased, and are released from the ships by their purchasers. The sick always fare the worst, for the healthy are naturally preferred and purchased first; and so the sick and wretched must often remain on board in front of the city for 2 or 3 weeks, and frequently die, whereas many a one, if he could pay his debt and were permitted to leave the ship immediately, might recover and remain alive.” [36]

“The sale of human beings in the market on board the ship is carried on thus: Every day Englishmen, Dutchmen and High-German people come from the city of Philadelphia and other places, in part from a great distance, say 20, 30, or 40 hours away, and go on board the newly arrived ship that has brought and offers for sale passengers from Europe.” [37]

“When a husband or wife has died at sea, when the ship has made more than half of her trip, the survivor must pay or serve not only for himself or herself, but also for the deceased. When both parents have died over half-way at sea, their children, especially when they are young and have nothing to pawn or to pay, must stand for their own and their parents’ passage, and serve till they are 21 years old.” [38]

Mittelberger perhaps provides a description of what Michael Hartom may have experienced sailing to the colonies in 1775. However, each personal experience may have unique experiences that are not common for similar voyages at the time and possibly do not represent the experiences of the majority of voyages.. While it does not diminish the general portrayal of hardships that were faced crossing the Atlantic, recent studies on German emigration during this time period suggest that mortality rates on voyages were a bit lower than what Mittelberger states.

For example, mortality rates for German immigrants traveling to American in two time periods, 1727 to 1754 and 1785 to 1805, were much lower. One study was based on a sample of fourteen German immigrant vessels which enumerated passenger deaths directly in the ship records, taken from the Strassburger collection of German ship lists for the port of Philadelphia. This sample had over 1,566 passengers and appeared to be relatively representative of the typical immigrant voyage: voluntary, white, civilian immigrants transported by the private shipping market on the North Atlantic route. Six of the ships had mortality enumerated for the separate categories of adult men, adult women, and children. The overall passage mortality for these 1,566 Germans was 3. 8 percent. The voyage mortality for the the 1,153 adult men was slightly above that for the 237 adult women, 3.5 versus 2.5 percent, respectively, although this difference was not statistically significant. The 382 children fared far worse with a passage mortality of over 9 percent or almost three times the adult rate. [39]

Mittelberger’s journey took over 100 days at sea, whereas the average crossing during this time period was onJy about two months. Michael Hartom’s voyage was purportedly six months, as documented by Evelyn Dutcher Griffis. However, we do not know if Evelyn’s “six month” statement includes his travel to the departing port. We also do not know when Michael Hartom started his journey.

Mittelberger’s ship carried 486 passengers. The average in the German trade was 300 between 1750 and 1754, and almost half that at other times. He also experienced a relatively longer, more crowded passage. [40]

By the 1830s to 1860s, North Atlantic passage mortality had fallen to between 2.4 and 1.0 percent, or as low as 10 per J,000 per month. Since these voyages lasted around one to one and a half months, the annualized crude death rate was as low as 80 to 120 per 1,000. Thus late eighteenth-century passage mortality was only about twice as high as early nineteenth-century passage mortality. [41]

Immigration in the 1800’s: Packet Ships from Havre

The German emigrants in the 1800’s, which included John Sperber and the Fliegel family, came to the United States via Le Havre, France, which was also reached via the Rhine River. Though people from all over Germany migrated to America, the Rhine represented the main highway out of Germany to the New World in the 1800s. They also took ships from other ports, notably Bremen, Germany and a smaller portion of travelers left via Hamburg. In the nineteenth century these ports were reachable by train.

“After the fall of Napoleon, Havre became the chief port of departure for continental Europe, and it retained its supremacy for more than a generation. The Swiss and South Germans arrived there overland or by sail from Cologne; and many came in coasting vessels from North Germany, and even from Norway for transshipment to America. In 1854 the German emigration by way of Havre exceeded that from Bremen by twenty thousand; while Bremen was ahead of Hamburg by twenty-five thousand, and Hamburg in turn led Antwerp by a like number. The completion of the German railway system and the great expansion of steam navigation in the Hanseatic cities eventually deprived Havre of her predominance in the business, but she remained an important port of departure as long as there was a large emigration from the region to which she was an accessible outlet.” [42]

“The development of steam transportation for immigrants, even after the invention of the screw propeller, was not so rapid as might have been expected. It was not till 1865 that more of them came by steam than by sail; and for more than a decade after that date sailing vessels still had a considerable share of the business.” [43]

Beginning in 1820, ship captains were required to file a list of all passengers aboard an arriving ship to the U.S. port authorities. The documentation provided a basis for official estimates of immigration for the nineteenth century. [44] While this increased the chances of being able to document German immigrants arriving in the United States, it is not a certainty that one will find ship manifest lists for all incoming passengers on ships that traveled to the United States in this time period.

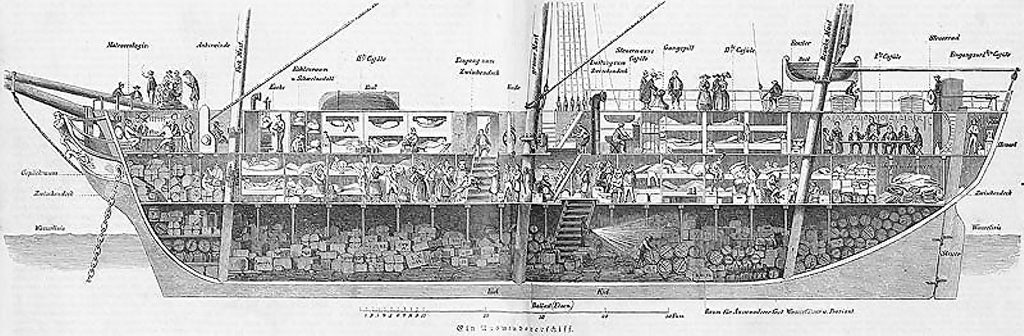

Many immigrants sailed to America or back to their homelands in packet ships between 1817 – 1880. The term packet ship was used to describe a vessel that featured regularly scheduled service on a specific point-to-point line. Usually, the individual ship operated exclusively for a specific shipping line. Packet ships were sail vessels that carried mail, cargo, and people.

Most of the immigrants crossed the Atlantic in the steerage area of the packet ships. Conditions varied from ship to ship, but steerage was normally crowded, dark, and damp. [45] While. the trip for immigrants was much shorter than those experienced in the 1700’s, the Atlantic crossing was still fraught with dangers ranging from shipwreck, overcrowded quarters, meager food rations, theft, disease and death.

In the late 1840s, William Smith became one of many immigrants who chose to leave his native home and family to undertake the trip to the United States. His published personal narrative of his experiences aboard the ship India as a steerage passenger traveling from Liverpool, England, to New York City exemplifies the experience of many millions of other immigrants to the United States. The mid-nineteenth-century steerage deck was, at its best, cramped and uncomfortable; ceiling heights could lie as low as five and a half feet, and the overall dimensions of the space were often about seventy-five by twenty-five feet. Travelers shared these tight quarters for an average of forty days. [46]

Disease spread quickly in this crowded environment, Smith’s personal narrative alludes to the prevalence of sickness and death. However, various studies have shown that the mortality rate on ships in the md 1800’s was not as high as what personal narratives have portrayed. Many have thought that immigrant mortality was fairly high during these years, but one study has shown that the mortality rate was 1.4 percent of the passengers, or about 10 per thousand per month, died on a typical voyage. The percent who died was significantly higher for ships arriving in November through February than for the other months. Sailing conditions in the North Atlantic were substantially worse during these months. [47]

The packet ships, unlike the later and more glamorous clippers, or steamers were not designed for speed. They carried cargo and passengers, and for several decades packets were the most efficient way to cross the Atlantic.

“Packet ships, packet liners, or simply packets, were sailing ships of the early 1800s that did something which was novel at the time: they departed from port on a regular schedule.” [48]

The cutaway below reveals how travelers and cargo sailed together on a packet ship. Travelers with enough money purchased “cabin passage” and slept in private or semiprivate rooms. The vast majority of passengers, usually immigrants, bought bunks in steerage, also called the ’tween deck’ for its position between the cabins and the hold.

Cross Section of a Packet Ship [49]

Packet Ships were sturdy vessels designed to sail the rough north Atlantic at the cost of speed. They measured about 200 feet long with three masts and a blunt, broad and flat bow. They could travel about 200 miles per day if the conditions were right. Their trans-Atlantic voyages averaged 23 days to go east, and 40 days to go west. [50]

In the 1830s steamships were introduced, and by the end of the Civil War they were taking over as the mode of transportation, especially for the more affluent. The sailing packet lines ceased operation altogether in 1880.

“By 1847, there were many ads showing that regular service had been established. In 1850, there was a noticeable uptick in the number of advertisements announcing regularly scheduled sailings between Europe and the United Stales. At this point. there were also more ads claiming passage on “fast” sailing ships, presumably trying to compete with the new steamships. Over the 1850s, more and more ads were placed regarding passage on steamships. By 1855, advertisements for fares on sailing ships dropped off and the paper no longer printed a fare table.” [51]

Getting and navigating to European ports was a new challenge for most emigrants, many of whom had never ventured very far from their home village. Ads in German newspapers oftentimes gave information about where where to stay in ports, when the cost of staying in the ports was included in the passage price, and how to survive cheaply before setting sail.

“For an adult traveling in steerage ona sailing ship, the average fare was 33 to 35 (Prussian) Thalers, about 23 dollars. These fares explain why most of the Germans who emigrated were positively self selected, that is, they were not poor farm laborers or servants but were somewhat better off. Around 1850, even a master farm laborer in the Rhine area earned only about 60 Thalers per year in cash in addition lo various in-kind goods, worth probably at least another 20 Thaler.” [52]

The most common destination for German emigrants was New York City, and getting there was expensive for many Germans. Moving to the United States was not a cheap endeavor for Germans during the middle of the nineteenth century. The fares were generally higher fares from Le Havre, Antwerp, and Rotterdam than from Hamburg or Bremen. The reason is that the listings for the fares from these cities included the cost of getting from a city in the interior of Germany to the port city. For example a listing might be “Koeln – Havre – New York”.

Even for individuals with skills that commanded a good wage, such as 70 to 100 Thalers a year, paying for just one transatlantic fare would have cost between one-third and one-half of their yearly income. While individuals could afford to emigrate at these prices, it was near the limit of what was affordable. For those who could come close to raising the necessary funds. paying for the voyage was made more feasible if they had an inheritance or could liquidate all their goods and properly before leaving.

“Most German emigrants had incomes no lower than those earned by the lower middle class, creating an emigrant population from German states that was positively self selected in the 1840s and 1850.” [53]

The Sperber and Fliegel Families: Emigration in the 1850’s

John Sperber and the Fliegel family emigrated to the United States in different years in the 1850’s. John Sperber reportedly arrived around 1853 and the Fliegel family arrived in 1855.

The ‘pater familias’, John Wolfgang Sperber, was born in Baden, Germany around 1828. His bride, Sophia Fliegel, and her family also immigrated to the United States around the same time. Both families were from the Grand Duchy of Baden. It is the German State occupying the southwest corner of Germany. As you can see from the map below, Baden borders on the Alsace region of France, Switzerland, Austria, and the German states of Hessen and Bavaria.

1855 Colton Map of Bavaria, Wurtemberg and Baden, Germany

The Sperber and Fliegel families were originally from Baden and Ettlingen Ittlingen respectively. Both towns are in the Baden Würtemberg area. The Wageneck family is a maternal branch of the Fliegel family. The family can also be traced back a number of generations from the Baden Würtemberg area.

The Baden-Württemberg area comprises the historical territories of Baden, Prussian Hohenzollern, and Württemberg. Baden spans along the flat right bank of the river Rhine from north-west to the south (Lake Constance) of the present state. Württemberg and Hohenzollern lay more inland and are hillier, including areas such as the Swabian Jura mountain range. The Black Forest formed part of the border between Baden and Württemberg. While the area is now formally a German state, it is historically an area that represented a variety of German city states.

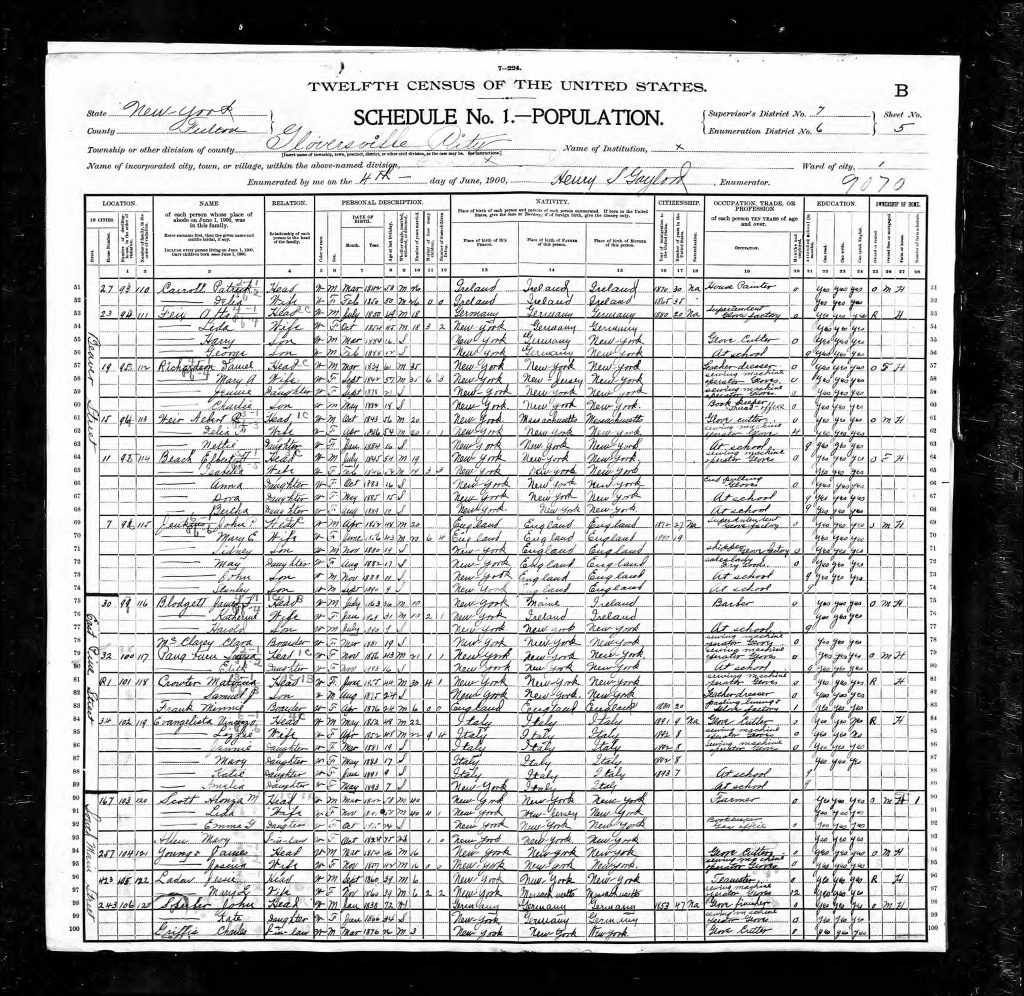

John Sperber was the second of the two family members to settle in Gloversville, New York. It is not entirely certain as to when John Sperber arrived in the United States. In a 1900 U.S. Federal Census, John Sperber reported, at the age of 72, that he arrived in the United States in 1853. Ship manifest records indicate a John Sperber arrived in 1852. [54]

Researching ship manifest lists of ships that arrived in the United States around 1853 revealed a few records that may point to our John or Johann Sperber. [55] The most likely record documents the arrival of a Johann Sperber arriving in the port of New York City on June 14, 1852. [56] Johann Sperber traveled on the packet ship named Germania and departed from Havre, France. Based on the ship manifest records, Johann Sperber was 26 years old, his estimated birth date was 1826, his occupation was listed as ‘cultivator‘ and his birth place was listed as ‘Bavaria‘. He stayed in the steerage area of the ship.

The Packet Ship Germania at pier, Le Havre, France [57]

Johann Sperber sailed on the Germania, a packet ship built in 1850 . It was in service by by the Havre Whitlock ship line between 1850 – 1863. Based on the ship’s records, it took an average of 38 days to sail from Havre to New York City. The Germania was one of fourteen ships owned and managed by the Havre Whitlock Line. [58] The ships sailed from New York to Le Havre every month on the 8th, 16th, and 24th, and sailed from Le Havre every month on the 1st, 8th, and 24th. [59]

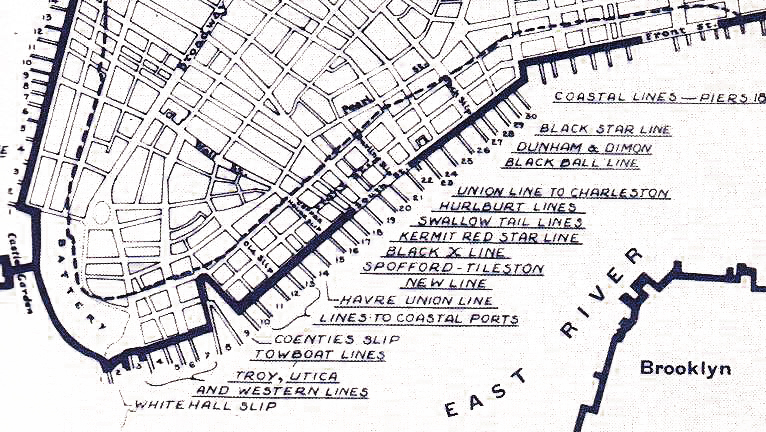

As reflected in the map below, Johann arrived at pier 14 in New York City on June 14, 1852.

Port of New York 1851

It is not known how and how long it took for Johann Sperber to travel from New York City to the Johnstown – Gloversville area.

“Gloversville was originally settled by New England Puritans in the 1790’s. In the ensuing decades as the community grew, leather tanning became a prominent local industry due to the purity and abundance of water and the availability of hemlock bark as a source of tannin. As a result, the manufacture of gloves became widespread as a cottage industry. It was in 1828 that the settlement was officially given its current name upon the establishment of the first post office.” [60]

After the Civil War, the glove industry boomed in the Johnstown and Gloversville, New York area, causing large numbers of immigrants from many of Europe’s glove making centers to make their new homes there.

The Fliegel family was actually from Ittlignen which is not listed on the above 1855 map. From 1355, Ittlingen was a possession of the Lordship of Gemmingen. Their rule ended in 1806, when the Gemmingens’ properties were mediatized to the Grand Duchy of Baden. Ittlingen was assigned on 22 June 1807 to Oberamt Gochsheim, the only such district in Baden. On 24 July 1813, Ittlingen was assigned to the district of Eppingen.

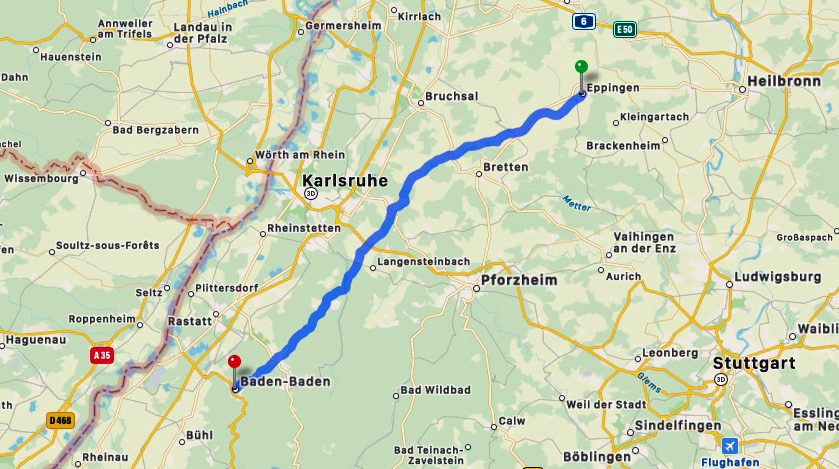

As the crow flies, Baden and Eppingen are about 47 miles apart. It would take you 16 and a half hours to walk from one area to the other.

Distance Between Baden and Eppingen Germany

In 1855, Christopher (Christoph) Fliegel and his wife Maria Juliana Wageneck made a major life altering decision to emigrate with their three young adult children to the United States. This must have been a hard decision to make, perhaps due to push factors they experienced in Germany. Christopher was 60 years old and Juliana was in her late fifties.

Similar to Johann Sperper’s experience, the family traveled from their German Rhineland home to Havre, France and took one of the packet ships run by the Havre-Union Line. They, like Johann arrived at pier 14 in New York City.

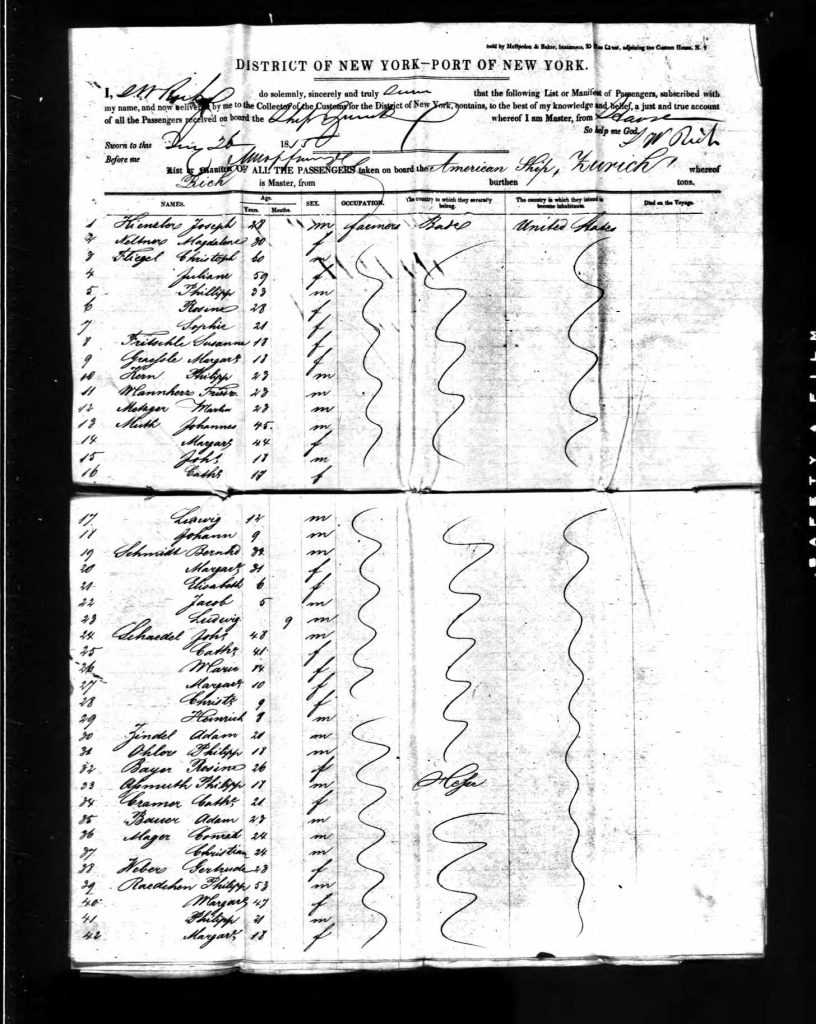

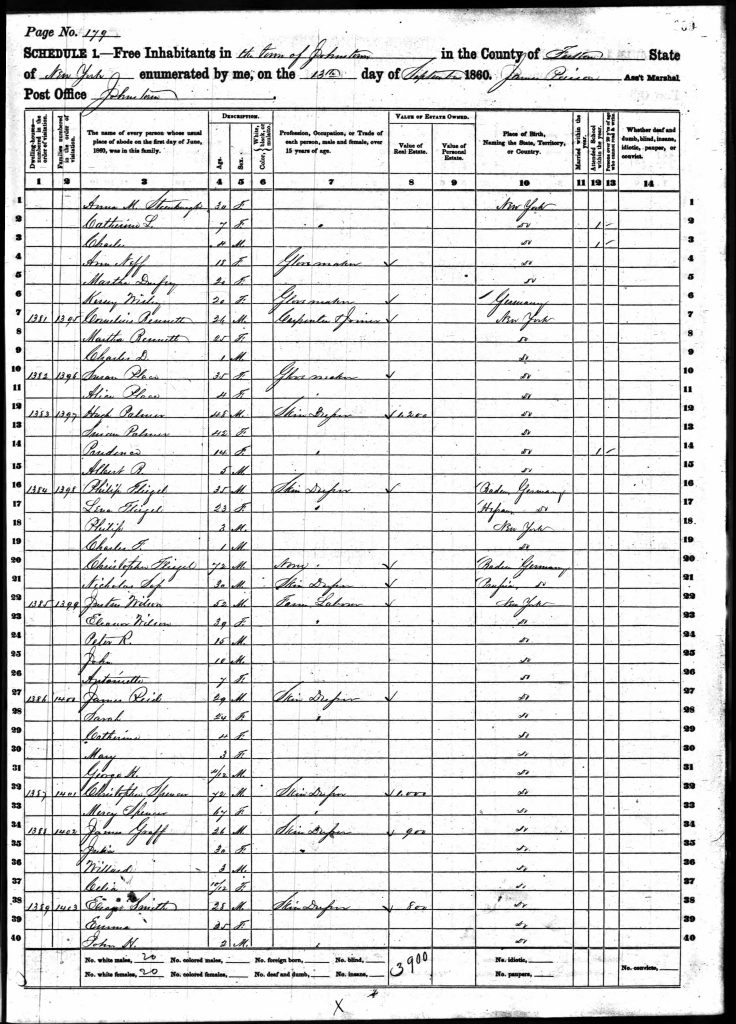

The manifest list for the ship the Fliegel family traveled on is below. It lists the following information (lines 3 – 7): Christoph Fliegel (age 60), Juliani (59), Phillipp (33), Rosina (28) and Sophie (21) from Baden Germany. [61]. They were among 303 individuals who sailed on the ship ‘Zurich‘ and arrived in New York City on January 26, 1855. [62]

Ship Manifest List for Fliegel Family

The American Ship Zurich was built in New York by W.H. Webb in 1844. [63] It was a class A2 ship of 817 tons with 2 decks. It was made of white Oak and the hull was medalled in September 1854. During its lifetime (1844 – 1863) it sailed from the New York port and principally sailed to Havre, France and it averaged 35 days from Harvre to New York City. [64] It was one of twenty-five packet ships that were part of what was called the Havre Old Line. [65]

Once in New York City, the family traveled west and ultimately established their new home in Johnstown New York. In five years, the U.S. Federal Census captured a shapshot of the family. [66] Chistopher, age 72, is living with this son Philip’s family Philip’s occupation is listed as a “Skin Dresser” , a work activity associated with glove making. Evidently the census enumerator did not capture Juliana’s whereabouts. Christoph Fliegel lived long enough to see his family settled in the United States. He passed away at the reported age of 74 on October 15, 1872. His wife Juliana reportedly died on February 23, 1867.

1860 U.S. Census

Sources

Feature Photograph of this story: This is a portion of a map from Colton, G. W., Colton’s Atlas of the World Illustrating Physical and Political Geography, Vol 2, New York, 1855 (First Edition) Issued as page no. 14 in volume 2 of the first edition of George Washington Colton’s 1855 Atlas of the World. The map covers the 19th century German provinces of Bavaria, Wurttemberg, Baden and Pfalz, as well as numerous smaller regions. The map is divided and color coded according to regional divisions. Various cities, towns, forts, rivers and assortment of additional topographical details are identified.

Highlighted Areas on Map: You can see the proximity of Eppingen (the home of the Fliegel family) and Baden, the home of John Wolfgang Sperber). 1855 Colton Map of Bavaria, Wurtemberg and Baden, Germany – Geographicus Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1855_Colton_Map_of_Bavaria,Wurtemberg_and_Baden,_Germany–Geographicus-_Germany3-colton-1855.jpg The Fliegel family was actually from Ittlignen which is not listed on the 1855 map. From 1355, Ittlingen was a possession of the Lordship of Gemmingen [de]. Their rule ended in 1806, when the Gemmingens’ properties were mediatized to the Grand Duchy of Baden. Ittlingen was assigned on 22 June 1807 to Oberamt Gochsheim [de], the only such district in Baden. On 24 July 1813, Ittlingen was assigned to the district of Eppingen.

Original digital file of map: 3,500 x 2,810 pixels, in ZoomViewer: https://zoomviewer.toolforge.org/index.php?f=1855%20Colton%20Map%20of%20Bavaria%2C%20Wurtemberg%20and%20Baden%2C%20Germany%20-%20Geographicus%20-%20Germany3-colton-1855.jpg&flash=no

[1] Benjamin Myer Brink, The Palatine Settlements, Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association, 1912, Vol. 11 (1912), pp. 136 https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/42889955.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A962eaf10dd5afe3ff4cdb27ba7b18019&ab_segments=&origin=&initiator=

[2] Cobb, Sanford Hoadley. The Story of the Palatines: An Episode in Colonial History. United Kingdom, G. P. Putnam’s sons, 1897. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Story_of_the_Palatines/eUgjAAAAMAAJ?hl=en

Brink, Benjamin Myer. “THE PALATINE SETTLEMENTS.” Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association, vol. 11, 1912, pp. 136–43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42889955. Accessed 27 May 2023.

Ellsworth, Wolcott Webster. “THE PALATINES IN THE MOHAWK VALLEY.” Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association, vol. 14, 1915, pp. 295–311. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42890044. Accessed 27 May 2023.

Diefendorf, Mary Riggs. The Historic Mohawk. United Kingdom, Putnam, 1910. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Historic_Mohawk/ziIVAAAAYAAJ?hl=en

Walter Allen Knittle, Early Eighteenth Century Palatine Emigration; a British Government Redemptioner Project to Manufacture Naval stores, Philadelphia: Dorrance & Co, 1905, https://archive.org/details/earlyeighteenthc00knit/page/n5/mode/2up

Nelson Greene, History of the Mohhawk Valley, Gateway to the West, 1614 – 1925 Covering the Six Counties of Schenectady, Schoharie, Montgomery, Fulton, Herkimer and Onieda – CVolume 2, S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_of_the_Mohawk_Valley_Gateway_to/aOApAQAAMAAJ?hl=en

The Palatine Germans, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/the-palatine-germans.htm

[3] Quote is from Philip Otterness, Becoming German, The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004, Pages 120-121

See also:

Donna Merwick, Possessing Albany, 1630-1710: The Dutch and English Experiences, Cambridge, 1990), Pages 204, 227, 259, 291, 294

Thomas Burke, Mohawk Frontier: The Dutch Community of Schenectady, New York 1660-1710, Ithaca, 1991, Page 213

Natalie Zemon Dennis, Cultivating a Landscape of Peace: Iroquois-European Encounters in the Seventeenth-century America, Ithaca, 1993, , Page 131

Francis Jennings, Ambiguous Iroquois Empire, New York, 1984, Page 193

[4] Württemberg Emigration and Immigration, FamilySearch, This page was last edited on 9 December 2022, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Württemberg_Emigration_and_Immigration

Germany Emigration and Immigration, FamilySearch, This page was last edited on 11 May 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Germany_Emigration_and_Immigration

Pre-1820 Emigration from Germany, FamilySearch, This page was last edited on 16 December 2022, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Pre-1820_Emigration_from_Germany

Michael P. Palmer, German and American Sources for German Emigration to America, Germans to America Zgenealology.net, http://www.genealogienetz.de/misc/emig/emigrati.html

[5] Baden-Württemberg, Wikipedia, Page accessed 19 May 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baden-Württemberg

Baden-Württemberg Maps, Family Search, Baden-Württemberg_Maps, This page was last edited on 26 June 2020, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Baden-Württemberg_Maps

History of Baden-Württemberg, Wikipedia, Page accessed on 19 May 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Baden-Württemberg

Württemberg Emigration and Immigration, FamilySearch, This page was last edited on 9 December 2022, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Württemberg_Emigration_and_Immigration

[6] The family tree diagrams were created using the online Ancestry.com family tree software. Consistent with their terms and conditions, the images of my family tree are used for only personal use in this blog. https://www.ancestry.com/c/legal/termsandconditions

[7] Gertrude Platts Perry was Evelyn Dutcher’s first cousin.

Kinship Relationship Between Evelyn Dutcher and Gertrude Platts

According to Nancy Griffis, based on conversations with Gertrude, she held her cousin, Evelyn, in high esteem; so much so that at times she was jealous of Evelyn’s success in life. As indicated by Nancy Griffis, based on Gertrude’s perception of her relationship with her cousin, she grew up in Evelyn’s shadow. At one point, she burned many photographs associated with the family. Allegedly one of the photographs was of the Indian descendant of the family.

[8] Walter Kenneth Griffith, The Dutcher Family, General Books LLC, 2010

[9] Demelt History, Family Crest & Coats of Arms,House of Names, https://www.houseofnames.com/demelt-family-crest

[10] The Platts name has three possible origins. The first and most likely being a topographic name for someone who lived on a flat piece of land deriving from the Olde French “plat” meaning “a flat surface”. The surname is first recorded in the early half of the 13th century. The name may also derive from the Olde English “plaett” or the Medieval English “plat” meaning “a plank bridge”, and given to one dwelling by a foot bridge. The first recorded spelling of the family name is shown to be that of John de la (of the) Platte, which was dated 1242 – The Pipe Rolls of Worcestershire, during the reign of Henry III, The Frenchman 1216-1272. A third possibility is of German origin, an “Anglicized” form of German Platz.

See:

Last name: Platts, SurnameDB,

Read more: https://www.surnamedb.com/Surname/Platts#ixzz83KfbK4Ud

Platts Name Meaning, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/name-origin?surname=platts

Platt Surname Definition, Forebears, https://forebears.io/surnames/platt

Platts Name Origin, Meaning and Family History, Your Family History, https://www.your-family-history.com/surname/p/platts/?year=1841#map

[11] History of German-American Relations, 1683-1900 – History and Immigration, U.S. Diplomatic Mission to Germany, Public Affairs, Information Resource Center, Page updated June 2008, https://usa.usembassy.de/garelations8300.htm

Carl Wittke, Carl, We Who Built America The Saga of the Immigrant (Cleveland: Western Reserve University, 1939). Page 187

[12] Germany from c. 1760 to 1815, Britanica, Page accessed 25 May 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Germany/Germany-from-c-1760-to-1815

See also: States of the German Confederation, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 29 June 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/States_of_the_German_Confederation

[13] Germany from c. 1760 to 1815, Britanica, Britanica.com , https://www.britannica.com/place/Germany/The-cultural-scene

Office of the Historian, The United States and the French Revolution, 1789-1799, Milestones: 1789-1800, U.S. Departmement of State, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1784-1800/french-rev#:~:text=The%20French%20Revolution%20lasted%20from,embroiled%20in%20these%20European%20conflicts

French Revolution, Wikipedia, Page updated 23 May 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Revolution

Thirty Years War, Wikipedia, Page updated 27 May 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thirty_Years%27_War

Benecke, Gerhard, Germany in the Thirty Years War. New York: St. Martin’s Press 1978

Polišenský, J. V. (1968). “The Thirty Years’ War and the Crises and Revolutions of Seventeenth-Century Europe”. Past and Present. 39 (39): 34–43. doi:10.1093/past/39.1.34

Rabb, Theodore K. (1962). “The Effects of the Thirty Years’ War on the German Economy”. Journal of Modern History. 34 (1): 40–51. doi:10.1086/238995. JSTOR 1874817

Theibault, John (1997). “The Demography of the Thirty Years War Re-revisited: Günther Franz and his Critics”. German History. 15 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1093/gh/15.1.1

[14] Robert Alfers, Map of German States 1789, 8 June 2008, German version, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_the_Holy_Roman_Empire,_1789_en.png

[15] States of the German Confederation, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 16 April 2023, Map of German states 1815-1866, by Ziegelbrenner, from Wikipedia, Karte des Deutschen Bundes 1815–1866 / Map of German Confederation 1815–1866, 19 Jan 2008, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/States_of_the_German_Confederation

[16] Philip Otterness, Becoming German, The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004, Page 3

{17] Learned, Marion Dexter, The Life of Francis Daniel Pastorius, the Founder of Germantown: Illustrated with Ninety Photographic Reproductions, Philadelphia, W. J. Campbell, 1908, https://archive.org/details/lifefrancisdani00leargoog/page/4/mode/2up

Samuel Whitaker Pennypacker, The Settlement of Germantown, Pennsylvania: And the Beginning of German Emigration to North America,Phildelphia, W. J. Campbell, 1899, https://archive.org/details/settlementgerma00penngoog

[18] F. Burgdorfer, Chapter 12: Migration Across the Frontiers of Germany, p. 313-389, Walter F. Wilcox, ed, International Migrations, Volume II: Interpretations, National Bureau of Economic Research NABER, January 1931, https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c5114/c5114.pdf

In 1709, in an area in Blackheath in south London, 13,000 German migrants called the Palatines formed what became regarded as Britain’s first refugee camp. They spoke different languages and belonged to different churches and became a curiosity for thousands of Londoners of the period. Most hoped to travel on to Carolina in the New World, after promises of work and prosperity, but in the end only a few made the trip to North America, and many returned to Germany.

See a YouTube video on the subject: BBC bitesize migration 2 palatines online v3 :European Migration to Britain in the 1700’s https://youtu.be/C1aeuKErVIo

[19] The Palatine Germans, The National Park Service, Updated October 8, 2022 https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/the-palatine-germans.htm

Aaron Spencer Fogleman, Hopeful Journeys: German Immigration, Settlement and Political Culture in Colonial America, 1717-1775, Philadelphia: University of pennsylvania Press 1996

Philip Otterness, Becoming German, The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York,Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004

Cobb, Sanford Hoadley. The Story of the Palatines: An Episode in Colonial History. United Kingdom, G. P. Putnam’s sons, 1897. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Story_of_the_Palatines/eUgjAAAAMAAJ?hl=en

Brink, Benjamin Myer. “The Palatine Settlements” Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association, vol. 11, 1912, pp. 136–43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42889955. Accessed 27 May 2023.

Ellsworth, Wolcott Webster. “The Palatines in the Mohawk Valley.” Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association, vol. 14, 1915, pp. 295–311. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42890044. Accessed 27 May 2023.

Diefendorf, Mary Riggs. The Historic Mohawk. United Kingdom, Putnam, 1910. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Historic_Mohawk/ziIVAAAAYAAJ?hl=en

Benton, Nathaniel Soley. A History of Herkimer County: Including the Upper Mohawk Valley, from the Earliest Period to the Present Time ; with a Brief Notice of the Iroquois Indians, the Early German Tribes, the Palatine Immigrations Into the Colony of New York, and Biographical Sketches of the Palatine Families, the Patentees of Burnetsfield in the Year 1725 ; and Also Biographical Notices of the Most Prominent Public Men of the County ; with Important Statistical Information. United States, J. Munsell, 1856. https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_History_of_Herkimer_County/G1IOAAAAIAAJ?hl=en

[20] Building a New Nation, Library of Congress, Classroom Materials, Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History, German, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/german/building-a-new-nation/

Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History, Building a New Nation, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/german/building-a-new-nation/

[21] German Immigration timeline, Study Smarter, https://www.studysmarter.us/explanations/history/us-history/german-immigration/

Bernard N. Meisner, Pushes, Pulls and the Records: A Brief Review of the Various Waves of German Immigrants to the United States, Dallas Genealogical Society German Genealogy Group,

[22] Quote from: Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: A New Surge of Growth, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/german/new-surge-of-growth/

European Emigration to the U.S. 1861 – 1870, Destination America, PBS, Sep 2005, https://www.pbs.org/destinationamerica/usim_wn_noflash_2.html

[23] History of German-American Relations > 1683-1900 – History and Immigration, U.S. Diplomatic Mission to German, This page was updated June 2008, https://usa.usembassy.de/garelations8300.htm

Irish and German Immigration, U.S. History , https://www.ushistory.org/us/25f.asp

Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: The Call of Tolerance, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/german/call-of-tolerance/

Amanda A. Tagore, Irish and German Immigrants of the Nineteenth Century: Hardships, Improvements, and Success, Pace University: Pforzheimer Honors College, May 2014, https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1144&context=honorscollege_theses

[24] United States. Department of Homeland Security. Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2008. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, 2009, Table 2, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Yearbook_Immigration_Statistics_2008.pdf

See also: German Americans, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 21 June 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_Americans

[25] Walter F. Wilcox, ed, International Migrations, Volume II: Interpretations, National Bureau of Economic Research NABER, January 1931, Chapter 12: Dr. F. Burgdörfer, Migration Across the Frontiers of Germany, p. 313-389 https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c5114/c5114.pdf

[26] Ibid, Pages 316-317

[27] The Call of Tolerance, Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History, Germany, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/german/call-of-tolerance/

[28] William John Hinke, ed, Ralph Beaver Strassburger, Pennsylvania German Pioneers: A Publication of the Original Lists of Arivals In the Port of Philadelphia From 1727 to 1808, Volume I, Norristown, PA: pennsylvania Gernam Society, 1934, Page xx https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniagerm05penn_1/page/n9/mode/2up

[29] David Lodge, The Journey Was Difficult: Many Did Not Survive the Trip Across the Ocean, Shelby County Historical Society, Nov 1997, https://www.shelbycountyhistory.org/schs/immigration/thejourney.htm

[30] Leaving Europe: A New Life in America – Departure and Arrival, Europeana, European Union, https://www.europeana.eu/en/exhibitions/leaving-europe/departure-and-arrival

Patricia Bixler Reber, 18th century immigrant ships – provisions, hardships, indentured servant process, 14 Oct 2019, Researching Food History, http://researchingfoodhistory.blogspot.com/2019/10/18th-century-immigrant-ships-provisions.html

Ellie Ayton, What was Life Like on Board an Emigrant Ship generations Ago?, 9 Sep 2020, Find My Past, https://www.findmypast.com/blog/history/life-on-board

A “description of Gottleib’s account – Passage To America, 1750,” EyeWitness to History, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com (2000) http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/passage.htm

John Simkin, Journey to America, Sep 1977, Spartacus Educational, https://spartacus-educational.com/USAEjourney.htm

Ellie Ayton, What was Life Like on Board an Emigrant Ship generations Ago?, 9 Sep 2020, Find My Past, https://www.findmypast.com/blog/history/life-on-board

Leaving Europe: A New Life in America – Departure and Arrival, Europeana, European Union, https://www.europeana.eu/en/exhibitions/leaving-europe/departure-and-arrival

[31] Gottlieb Mittelberger’s Journey to Pennsylvania in the Year 1750 and Return to Germany in the year 1754, Philadelphia: John Jos. McVey, 1989 https://www.google.com/books/edition/Gottlieb_Mittelberger_s_Journey_to_Penns/4KYlAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=intitle:Gottlieb+intitle:Mittelberger%27s+intitle:Journey+intitle:to+intitle:Pennsylvania&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

[32] Ibid, Page 18

[33] Ibid, Page 19

[34] Ibid, Page 20

[35] Ibid, Page 23

[36] Ibid, Page 25

[37] Ibid, Page 26

[38] Ibid, Page 28

[39] Grubb, Farley. “Morbidity and Mortality on the North Atlantic Passage: Eighteenth-Century German Immigration.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 17, no. 3 (1987): 565–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/204611.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid

[42] Page, Thomas W. “The Transportation of Immigrants and Reception Arrangements in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Political Economy 19, no. 9 (1911): 732–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1820349.

[43] Ibid; see also

Cohn, Raymond L. “The Transition from Sail to Steam in Immigration to the United States.” The Journal of Economic History 65, no. 2 (2005): 469–95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3875069.

Cohn, Raymond L. “Mortality on Immigrant Voyages to New York, 1836-1853.” The Journal of Economic History 44, no. 2 (1984): 289–300. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2120706.

Graham, Gerald S. “The Ascendancy of the Sailing Ship 1850-85.” The Economic History Review 9, no. 1 (1956): 74–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/2591532.

Moltmann, Günter. “Migrations from Germany to North America: New Perspectives.” Reviews in American History 14, no. 4 (1986): 580–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/2702202.

Graham, Gerald S. “The Ascendancy of the Sailing Ship 1850-85.” The Economic History Review 9, no. 1 (1956): 74–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/2591532.

Riley, James C. “Mortality on Long-Distance Voyages in the Eighteenth Century.” The Journal of Economic History 41, no. 3 (1981): 651–56. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2119944.

Hoerder, Dirk. “The Traffic of Emigration via Bremen/Bremerhaven: Merchants’ Interests, Protective Legislation, and Migrants’ Experiences.” Journal of American Ethnic History 13, no. 1 (1993): 68–101. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27501115.

Bade, Klaus J. “German Emigration to the United States and Continental Immigration to Germany in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries.” Central European History 13, no. 4 (1980): 348–77. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4545908.

[44] Immigration, Steaming into the Future, Steamship Historical Society of America, https://shiphistory.org/themes/immigration/

[45] Aboard a Packet, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian, https://americanhistory.si.edu/on-the-water/maritime-nation/enterprise-water/aboard-packet

Kathi Gosz, A Look at Le Havre, a Less-Known Port for German Emigrants, 9 Oct 2011, ‘Village Life in Kreis Saarburg Germany’, Blog, http://19thcenturyrhinelandlive.blogspot.com/2011/10/look-at-le-havre-less-known-port-for.html

[46] William Smith, An Emigrant’s Narrative or a Voice from Steerage, New York: Published by the Author and Printed by E. Winchester, 1850 https://www.google.com/books/edition/An_Emigrant_s_Narrative_Or_A_Voice_from/wIYTAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

An Emigrant’s Narrative; or, A Voice from the Steerage Summary, WikiSummaries, Last updated on November 10, 2022, https://wikisummaries.org/an-emigrants-narrative-or-a-voice-from-the-steerage/

[47] Cohn, Raymond L. “Mortality on Immigrant Voyages to New York, 1836-1853.” The Journal of Economic History 44, no. 2 (1984): 289–300. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2120706.

[48] McNamara, Robert. “Packet ship.” ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/packet-ship-definition-1773390 (accessed July 10, 2023)

[49] Inside a Packet Ship, 1854, From Die Gartenlaube Leipzig Fruft NeilCourtesy of the Mariners’ Museum, Wkimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Inside_a_Packet_Ship,_1854.jpg

[50] Quote from: Genealogy Packet Boats, ships were backbone of U.S. Water travel, Tribune-Star, April 24, 2014, https://www.tribstar.com/features/history/genealogy-packet-boats-ships-were-backbone-of-u-s-water-travel/article_8033a7a5-947c-5e62-ba27-4ef854ca0343.html

See also: Packet boat, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 8 March 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Packet_boat

[51] Cohn, Raymond L., and Simone A. Wegge. “Overseas Passenger Fares and Emigration from Germany in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Social Science History 41, no. 3 (2017): 393–413. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90017919.

[52] Ibid

[53] Ibid

[54] United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1900. T623, 1854 rolls. Year: 1900; Census Place: Gloversville Ward 1, Fulton, New York; Roll: 1036; Page: 5; Enumeration District: 0006, Bounded By Forest, Fremont, Steele Ave, City Limits, South Main , Page 5, Line 98.

[55] Researching ship manifest lists during this time period have revealed a few records that may point to our John or Johann Sperber

German Passengers Immigrating to American Around 1853 with Name Sperber

| Name | Birth Year | Birthplace | Arrival Date | Departure Port | Arrival Port |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johann Sperber | 1826 | Bavaria | 14 Jun 1852 | Havre | New York |

| Joh G. Sperber | 1834 | Bavaria | 09 Jul 1856 | Hamburg | New York |

| J. Sperber | 1832 | Bavaria | 08 May 1855 | Bremen | New York |

| W. Sperber | 1828 | 20 Jun 1853 | Bremen | New York |

Original data:View Sources.

“United States Germans to America Index, 1850-1897.” Database. FamilySearch. http://FamilySearch.org : 18 July 2022. Citing NARA NAID 566634. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

I have researched a number of sources for ship manifest records for Johan Wolfgang Sperber and Michael Hartom, some of which are listed below:

Below is a list of indexes and finding aids for New York passenger lists for 1820 to the 1890s (and beyond), including the Castle Garden period.

- New York Passenger Lists Online Index and Images, 1820-1957 at Ancestry/requires payment; includes digitized images of the passenger lists from the National Archives microfilm; covers the Castle Garden, Barge Office and Ellis Island years

- New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1891 at FamilySearch (free with registration) includes index and images of the passenger lists

- New York, New York, Index to Passenger Lists, 1820-1846 at FamilySearch (free with registration) index only

- New York, New York, Index to Passengers Lists of Vessels, 1897-1902 at FamilySearch (free with registration) index only

- Germans to America, 1850-1897 (books and online database)

- Germans to America, 1840-1849 (books)

- German Immigrants: Lists of Passengers Bound from Bremen to New York 1847-1871 (books – these do not include every ship, only a small percentage)

- ISTG Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild LLC, Passenger Manifest Lists and Other

- Edited by Ira A. Glazier and P. William Filby, authors: Glazier, Ira A. (Main Author), Filby, P. William (Percy William), 1911-2002 (Added Author). Germans to America : lists of passengers arriving at U.S. ports, Wilmington, [Delaware] : Scholarly Resources Inc., 1988-2002

- Edited by Ira A. Glazier, Germans to America – series II : lists of passengers arriving at U.S. ports in the 1840s, Lanham, Maryland : Scarecrow Press, c2004

- Gary J. Zimmerman and Marion Wolfert, German immigrants : lists of passengers bound from Bremen to New York, with places of origin, Baltimore, Maryland : Genealogical Publishing Company, 1985-1993

- ISTG Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild , Ships Manifests Departing from Germany, Ports of departure include: Altona, Bremen, Bremerhaven, Cuxhaven, Geestemunde, Hamburg, Stettin, Swinemunde (currently Swinoujscie, Poland), German Unspecified Ports, https://immigrantships.net/bremenproj/bremenproject.html

[56] Affiliate Manifest ID: 00006987, Affiliate ARC Identifier: 1746067 “United States Germans to America Index, 1850-1897,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:KD7R-9SX : 27 December 2014), Johann Sperber, 14 Jun 1852; citing Germans to America Passenger Data file, 1850-1897, Ship Germania, departed from Havre, arrived in New York, New York, New York, United States, NAID identifier 1746067, National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

[57] Source: Ship GERMANIA at pier, Le Havre, France, Collections & Research, Mystic Seaport Museum , Stereograph photograph by Andrieu, J.

France, Normandie, Le Havre after 1850, paper 7 x 3-1/2 in.; sailing vessels at pier, GERMANIA in foreground; written on back “422 Ecluse de la Barre, at Saquebot, de Gernania de New-York/ au Heavre/ Packet ship Germania/ Chas Henry Townsend [sic.] Cmdg.” Printed on front “VILLES & PORTS MARITIMES” and “PHOTOIE DE J. ANDRIEU, PARIS.” [GERMANIA, ship, later bark, built 1850, Portsmouth, NH, by Fernald & Pettigrew, 996 tons, 170.7 x 35.5 x 17.7; New York & Havre Union Line.] http://mobius.mysticseaport.org/detail.php?module=objects&type=related&kv=197388

[58] Havre-Union Line (trans-Atlantic packet), Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 17 May 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Havre-Union_Line_(trans-Atlantic_packet)

[59] Holley, O. L., ed. (1845). The New-York State Register, for 1845. New York: J. Disturnell. p. 257

[60] History of Gloversville, City of Gloversville, http://www.cityofgloversville.com/residents/city-historian/

[61] Albion, Robert G. Square-Riggers On Schedule: The New York Sailing Packets to England, France, and the Cotton Ports. Hamden, Conn.: Archon, 1965.

Cutler, Carl C. Queens of the Western Ocean: The Story of America’s Mail and Passenger Sailing Lines. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1961.

Lubbock, Basil. The Western Ocean Packets. New York: Dover, 1988.

[62] Christoph Fliegel (age 60), Juliani (59), Phillipp (33), Rosina (28) and Sophie (21) from Baden Germany, Year: 1855; Arrival: New York, New York, USA; Microfilm Serial: M237, 1820-1897; Jan 26, 1855, Page One, Lines: 3-7; List Number: 53, Ship or Roll Number: Zurich

New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957, Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Microfilm Publication T715, 8892 rolls. NAI: 300346. Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service; National Archives at Washington, D.C. Supplemental Manifests of Alien Passengers and Crew Members Who Arrived on Vessels at New York, New York, Who Were Inspected for Admission, and Related Index, compiled 1887-1952. Microfilm Publication A3461, 21 rolls. NAI: 3887372. RG 85, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service; National Archives, Washington, D.C. Index to Alien Crewmen Who Were Discharged or Who Deserted at New York, New York, May 1917-Nov. 1957. Microfilm Publication A3417. NAI: 4497925. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Passenger Lists, 1962-1972, and Crew Lists, 1943-1972, of Vessels Arriving at Oswego, New York. Microfilm Publication A3426. NAI: 4441521. National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7488/images/NYM237_150-0080?pId=1184419 ;

[63] Immigration & Steamships, Mystic Seaport, the Museum of America and the Sea, https://research.mysticseaport.org/exhibits/immigration/

[64] American Lloyd’s Register of American and Foreign Shipping, New York: E & G.W. Blunt, Clayton & Ferris Printers, 1859, Page 93 https://research.mysticseaport.org/item/l0237571859/#29

[65] Havre-Union Line (trans-Atlantic packet), Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 17 May 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Havre-Union_Line_(trans-Atlantic_packet)

[66] U.S. Federal Census, New York, Fulton County, Johnstown, Dweling Number 1398, 6 household members, lines 16-21, Page 179.