Introduction

William James Griffis, and his older brother, Daniel Griffis, fought in the American Civil War. William is my great great grandfather. This is a story of two brothers, Daniel – the oldest sibling in the family and the William – the youngest male sibling in the family. Both had blue eyes, dark hair and were similar in height.

The tragedy of the Civil War is often summed up in the phrase “brother against brother.” Americans fought against Americans. Notably in the borderline states between the north and south, families had individuals who fought on both sides of the conflict. Moreover, Northern soldiers and Southern soldiers were very much alike — from their backgrounds, to their education, to their courage and loyalty to their local areas. So in a more general sense, ‘brothers fought against brothers’. This story, however, is not a story of a brother against another brother. It is a story of two brothers, Daniel and William who volunteered to fight for the Republic cause in the Civil War. Perhaps for different reasons, both Daniel and William volunteered to fight for the Union cause at the same time.

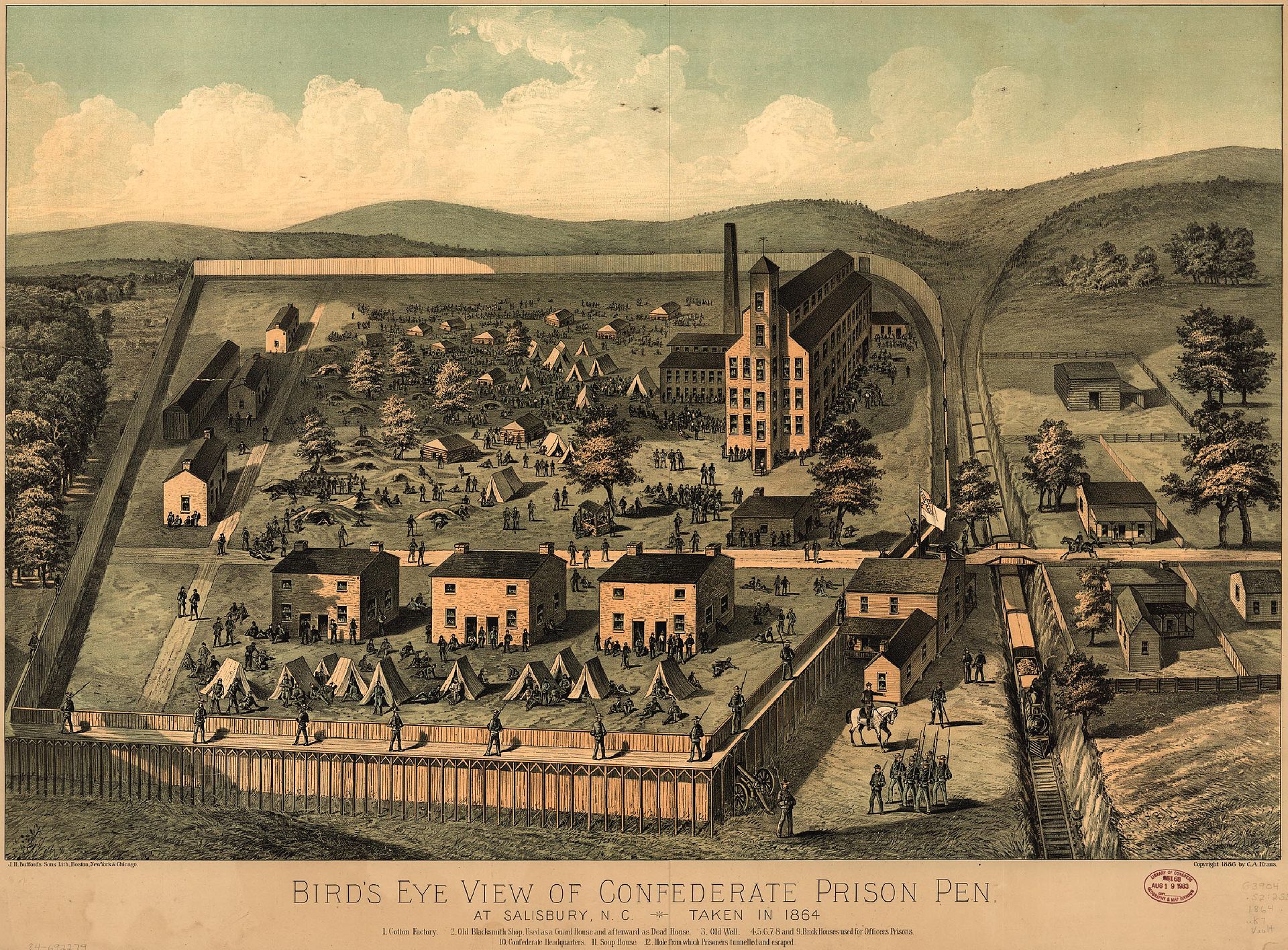

Both of their stories are different yet may be viewed as “two sides of the same coin”. One brother, William, during one of his assignments in his three years of duty, guarded confederate prisoners. The other older brother Daniel was captured and became a prisoner of the confederates. The individual who captured Daniel, John Singleton Mosby, ‘the grey ghost’, was a prisoner for 10 days in July, 1862 in a prison that William’s regiment subsequently had guard duty responsibilities in the District of Columbia in October of that year.

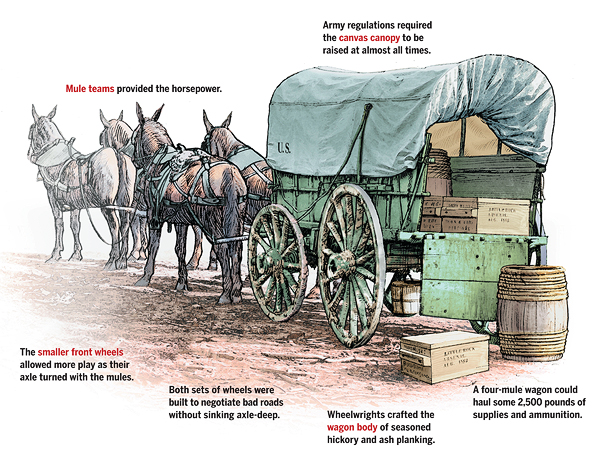

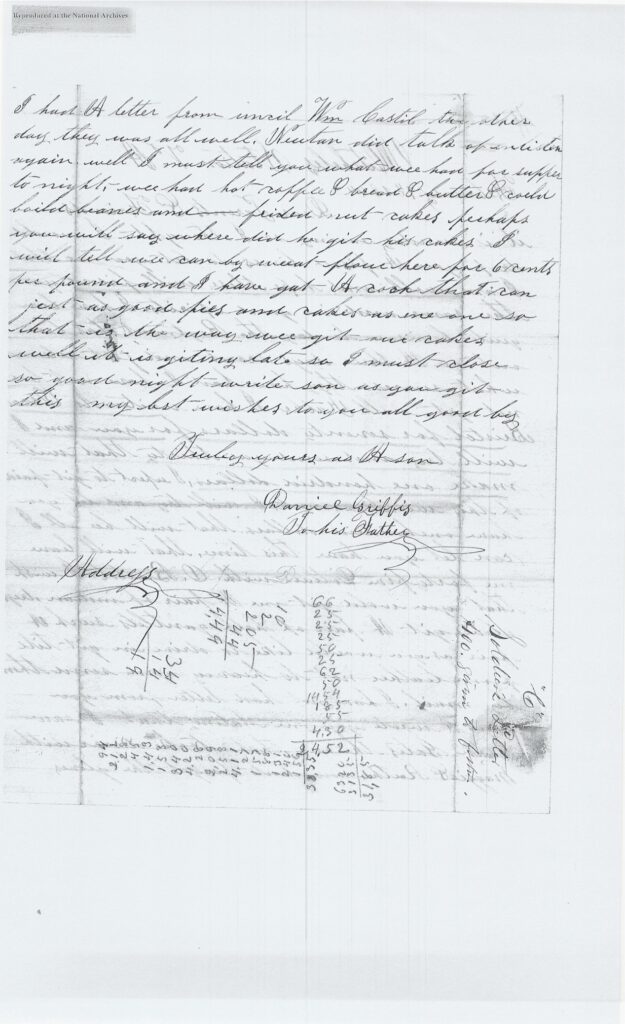

For William, his experience in the Civil War largely involved provost guard and garrison duty in the Nation’s capital and a few experiences with actual battle in Louisiana. While his infantry unit fought in Louisiana, his brother Daniel was engaged in a number of major battles and minor skirmishes in northern Virginia. Daniel, enlisted in an infantry division that later became a calvary unit. As a wagon master in a calvary regiment, Daniel was captured by Mosby’s raiders. He ultimately was transferred from Richmond, Virginia to one of the largest confederate prisons – Salisbury Prison in North Carolina. At the prison, he became ill and died.

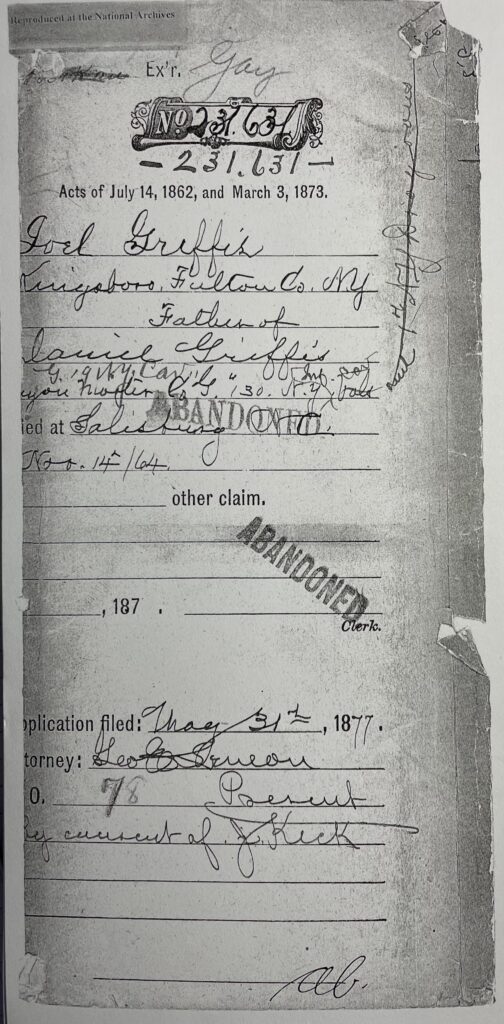

It is interesting to note that I did not know of Daniel’s involvement in the Civil War with the First Dragoons until I inadvertently found a pension file under the name of Joel Griffis, his father. His life at such a young age was a dead end in terms of ancestry research. I could not find him in U.S. Census records after 1860. Upon receiving copy of Joel Griffis’ Civil War pension request as a dependent, I discovered Daniel’s military history and untimely death. [1]

This story is created through the use of a variety of historical sources. In addition to the typical family ancestry sources of the U.S. Census, I have relied upon Civil War pension records, Library of Congress records related to Civil War Regiments, published historical accounts related to each of William and Daniels’ regiments, scholarly accounts on various facets of the Civil War and ‘non-academic’ historian’s accounts on the mundane aspects of the Civil war military and the common soldier. Hopefully, by combining these various sources, in absence of personal accounts in letters or other artifacts, I have been able to construct a story of what the two brother’s witnessed as soldiers. We may not know what they looked like, who they actually were and how they felt about things but perhaps putting them into a wider historical context of what they witnessed will give family members, and those interested in the common man in the civil war, a glimmer of who these two brothers were. I only wish we had photographs of their faces.

While I started this story with the intent of interweaving the accounts of two brothers in the Union Army, I found that the story was getting a bit long so I have broken the story up into three major parts and side stories related to Daniel’s capture and imprisonment and William’s post military life.

Daniel and William: Their Lives Up to the War

The brothers were the sons of Joel Griffis and Margerie Gilespie [2]. Joel and Margerie were married in Watervliet, New York in 1831. [3] There were seven children in the family, four sons and two daughters. Daniel was the oldest (born 1832), followed by Stephen (1834), Joseph H. (1836), Margaret Mary (1838), William James (1843), Ruth Addie (1845) and Francis (1850). Based on the birth locations of the children, it appears the family moved from the Schenectady, New York area to Mayfield, New York around 1835. The two older sons were born in the Watervliet – Albany New York area while the remaining children were born in Fulton County where Mayfield is located. It appears that Joel and Margery along with other Griffis family members, notably his father Daniel Griffis (1777 – ) and brother William Gates Griffis (1805- 1860), migrated westward [4] to the rural areas of Mayfield in 1835 to live life as farmers.

In 1840, Joel and Margery’s family of six had one male under 5 (Joseph), two males 5 through 9 (Daniel and Stephen) and another male 30-39 (Joel). There was one female under 5 (Margaret), 1 female between the ages of 20-29 (Margerie). Four of the family members were employed in agricultural activities. [5]

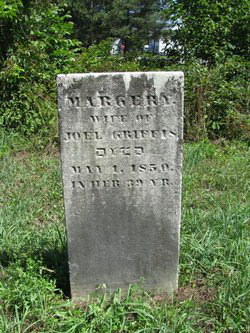

By 1850, the household grew to include William, Ruth and Francis. However, at the age of 39, Margery passed away on May 1st in 1850 [6]. It is not known what was the cause of death. Her youngest child, Francis, was born in 1849. Joel, a widower, undoubtably had his hands full with a household of six children ranging from Daniel at 18 to Ruth at one year of age. All but Stephen were living with Joel. [7] Stephen, at the age of 16, was living with his uncle William and grandfather Daniel [8].

Five years later, Joel is still single and has three older children, Stephen (21), Joseph (19), Margaret (17); and two younger children, William (12) and Ruth (9), in the household. The youngest, Francis, passed away at the age of 5. There are no records of her cause of death. The eldest, Daniel, moved out of the house around 1853 and was living in a boarding house, working as a laborer in Johnstown, New York [9].

Daniel, at the age of 24, married Augusta Bristol, the same age, at the Mayfield Central Presbyterian Church a the end of January, 1856 [10]. They may have been childhood sweethearts or long time neighbors that finally fell in love. The 1855 New York census indicates that she lived in Mayfield for the past 19 years and her home was close to Joel’s family farm. Daniel and Augusta must have known each other as they grew up. Augusta’s household was the 23rd house that the New York census taker visited. The Griffis household was the 33rd that the census taker visited while conducting the census on June 5th, 1855. [11] Augusta was living with her mother and sister Emily and two other women. Augusta listed her occupation as a glover maker.

Sometime after June 1855, Joel Griffis remarried. He married Anna Marie Ostrom. Not much is known about Anna or ‘Hannah’. In 1856, they started their family with the birth of Mary Griffis in 1856 and Oliver Griffis in 1859. Joel C. (Charles?) Griffis follows in 1862 and Amelia in 1865. Although the family is not documented in the 1860 census, it is assumed that William and Ruth are living with Joel and his new wife and their half sister and half brother.

The future for Daniel and his wife Augusta was cut short with her untimely death at the age of 27 in 1861 [12]. The death undoubtedly had a profound effect on Daniel. The cause of death is not know. We do not know if she died in child birth or other causes. Since she was buried in Mayfield, New York, it is assumed they were living in the Mayfield area.

It was during this year that the Civil War began in April. Initially, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 men to serve for three months. Later that summer, Congress approved the enlistment of 500,000 men for three years.

William Griffis was 18 in 1861. It is not known where he was living. He was a laborer when he entered the service.

In August, 1862, both Daniel and his brother William enlisted in the Union Army. It is not known if the brothers discussed their mutual decisions. Perhaps both were caught up in the national patriotic fervor or lured into service for the sense of adventure or monetary gain [13]. Perhaps both brothers simply desired to get away from Mayfield and their respective pasts. Most of the Civil War soldiers were between the ages of 18 and 39 with an average age just under 26. The majority of soldiers North and South had been farmers before the war. [14]

Two Brothers Enlisting in the Union Army

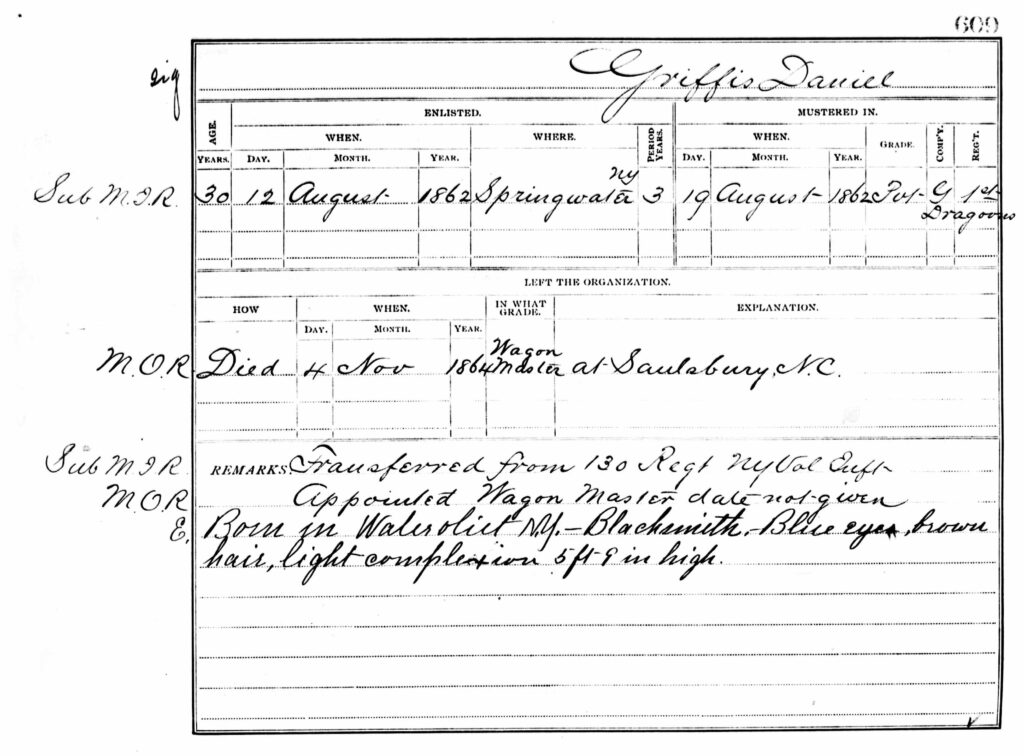

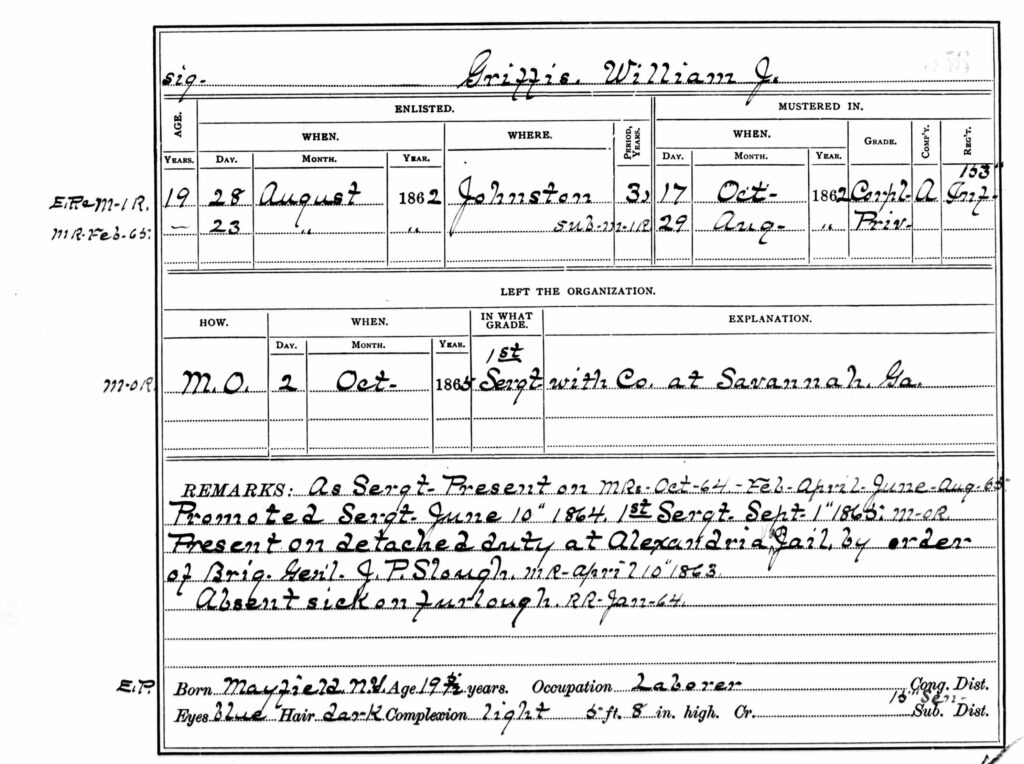

The brothers enlisted within two weeks of each other. Daniel enlisted at the age of 30 on August 12, 1862 and quickly mustered into service on August 19th. William, at 19, enlisted August 28, 1862 and quickly was promoted to corporal and mustered into service on October 17th, 1862.

The timing and quick turnaround between enlistment and mustering into service for both of the brothers reflected the nation’s urgent need for recruits. By the middle of 1862 the Civil War was into its fourteenth month. Both sides initially thought the ‘strife’ would not last long. However, high casualties and the failure of Major General McClellan’s Peninsular Campaign places pressure on the Union side for the need for more troops to turn the tide against the Confederacy. In 1862, rather than institute a politically sensitive draft, President Lincoln requested 300,000 more men and assigned each state a quota. The states could meet their quota in any manner they saw fit. Most states offered cash incentives, known as bounties, to gain recruits. The urgency for recruits is reflected in the rapidity of creating volunteer regiments and putting them into action. [15]

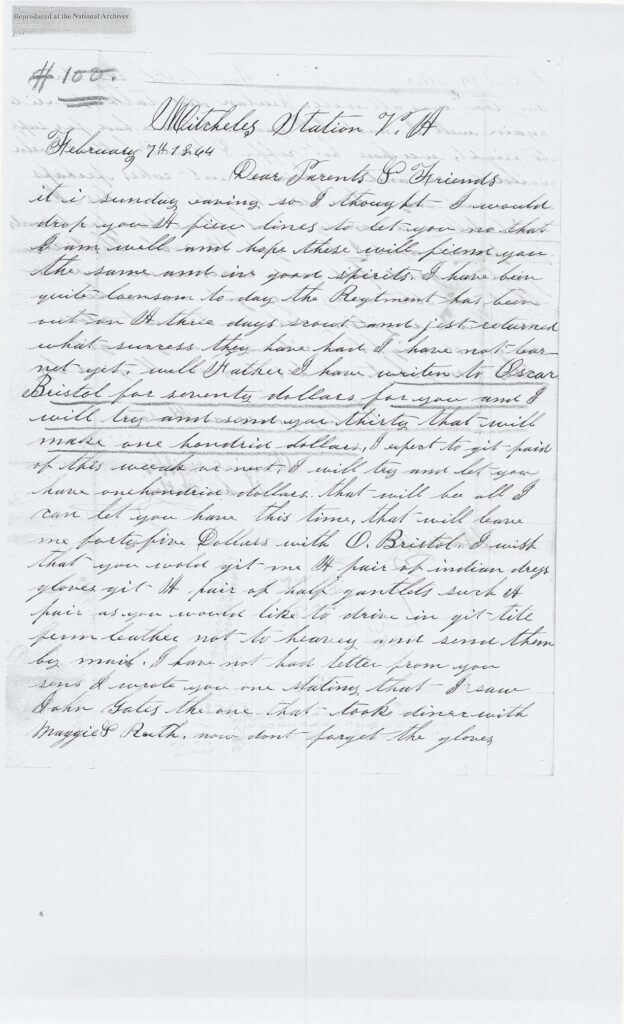

As reflected in the Muster Roll record below [16], Daniel enlisted in Springwater, New York as a Private. Springwater is approximately 200 miles west of Mayfield, NY, south of Hemlock Lake in the finger lake area of New York. The distance is considerable given the the era. Daniel moved to this area after the death of his wife and before he enlisted. He was providing assistance to Oscar Bristol, a farmer, before he enlisted. [17] While a family connection could not be documented, I believe Oscar Bristol was a second cousin of Augusta Bristol, Daniel’s former wife. Daniel listed his occupation as a Blacksmith. Perhaps he was providing blacksmith services to Oscar Bristol and trying to figure out his life after Augusta’s death.

Daniel enlisted for a three year assignment in the 130th New York volunteers infantry regiment. He enlisted in Company “G”. Each of the companies for the regiment were based on geographical areas from which they recruited soldiers. The “G” company recruited from the Stillwater, New York area. [18]

While perhaps he thought he would be in the infantry, his short military career was transformed from infantry duties to calvary and wagoner duties after a year in service. The 130th infantry regiment of New York had the distinction of being the only Union army volunteer regiment which was converted entirely from infantry to cavalry during the Civil War. [19] It was converted to a calvary unit on July 28, 1863 and renamed as the 19th regiment of New York volunteer calvary. In September of that year they were officially renamed as First New York Dragoons. The term dragoon generally refers to mounted infantry or light calvary.

“The history of the First New York Dragoons is, in one respect, unique, it having as an unbroken organization served in two distinct branches of military service, one year in infantry, and two in calvary. During the first year we were known as the One Hundred and Thirtieth New York Volunteer Infantry, and had abundant experience as ‘dough boys’ in fighting on foot, as well as in long and exhausting marches with blistered feet and aching joints. As cavaliers we also had our turn of pitying the poor boys who still had ‘hoof it’. We also learned full well that, though riding our prancing steads, the mounted service was not all fun, especially under such vigorous leaders as Sheridan.” [20]

While Daniel was quickly getting his affairs in order to muster into service in August 19, 1862, his younger brother William was enlisting in Fonda, New York on August 23rd. Fonda is on the Mohawk River, just south of Johnstown, New York. William mustered into service October 17, 1862 for the standard three year enlistment term in the New York 153rd Infantry Volunteers, Company “A”. Perhaps based on bounty incentives, it appears he was quickly promoted to corporal August 28, 1862 in Johnstown, New York. [21]

The 153rd New York Infantry Regiment was recruited in the counties of Fulton, Montgomery, Saratoga, Clinton, Essex and Warren. It was organized at Fonda and there mustered into the U. S. service on Oct. 17, 1862, for three years. The companies were recruited principally: at Johnstown (Company A); at Mohawk, Palatine and Root (Company B); at Glen, Florida, Root and Charleston (Company C); at Johnstown and Mayfield (Company D); at Minden and St. Johnsville (Company E); at Ephratah, Canajoharie, Oppenheim, Clifton Park and Lassellsville (Company F); at Mooers, Altona, Essex and Plattsburg (Company G); at Greenfield, Milton, Gal-way, Clifton Park, Ballston Spa, Moreau, Root and Wilson (Company H); at Champlain, Chesterfield, Plattsburg and AuSable (Company I); and at Queensbury, Ellenburg, Altona and Mooers (Company K). [22]

An interesting side note about the 153rd regiment is the existence of a woman, Sarah Rosetta Wakeman, who fought in Company H. Her military experience and ‘tour of duty’ mirrored William’s. However, as a woman in the military, her experience undoubtably was harrowing, fraught with constant worry of being outed as a woman, facing hostility and possible imprisonment. An estimated 400 young women disguised themselves as men and finessed their way through or around the physical exam to become soldiers. [23]

Coming from a large, poor farming family, she left home disguised as a man purportedly to make better wages than as a domestic servant. Wakeman signed on as a boatman doing manual labor on a coal barge traveling on the Chenango Canal. Shortly after making her first trip, she encountered recruiters from the 153rd New York Infantry Regiment. The offer of a $152.00 bounty was too good to refuse, and on August 30, 1862, Wakeman enlisted under the name of Lyons Wakeman. One point of interest in Wakeman’s service is her time spent as a guard at Washington’s Carroll Prison. During her time there, one of the three women held at the prison was arrested for a crime Wakeman herself was committing: impersonating a man to fight for the Union. [24] The aftermath of the Red River Campaign resulted in her contracting chronic diarrhea of which she eventually died on June 19, 1864, in the Marine USA General Hospital in New Orleans.

Photo of Sarah Rosetta Wakeman (January 16, 1843 – June 19, 1864). Wakeman was a woman who served in the Union Army during the American Civil War under the male name of Lyons Wakeman. Wakeman served with Company H, 153rd New York Volunteer Infantry. Photo source: Afton Historical Society, Afton, Minnesota

Her letters written during her service remained unread for nearly a century because they were stored in the attic of her relatives.

Union privates were paid $13.00 per month until after the final raise of 20 June 20, 1864 when they received $16.00. In the infantry and artillery, officers at the start of the war received varying amounts based on rank: colonels, $212; lieutenant colonels, $181; majors, $169; captains, $115.50; first lieutenants, $105.50; and second lieutenants, $105.50. Soldiers were supposed to be paid every two months in the field, but they were fortunate if they received their pay at four-month intervals. [25]

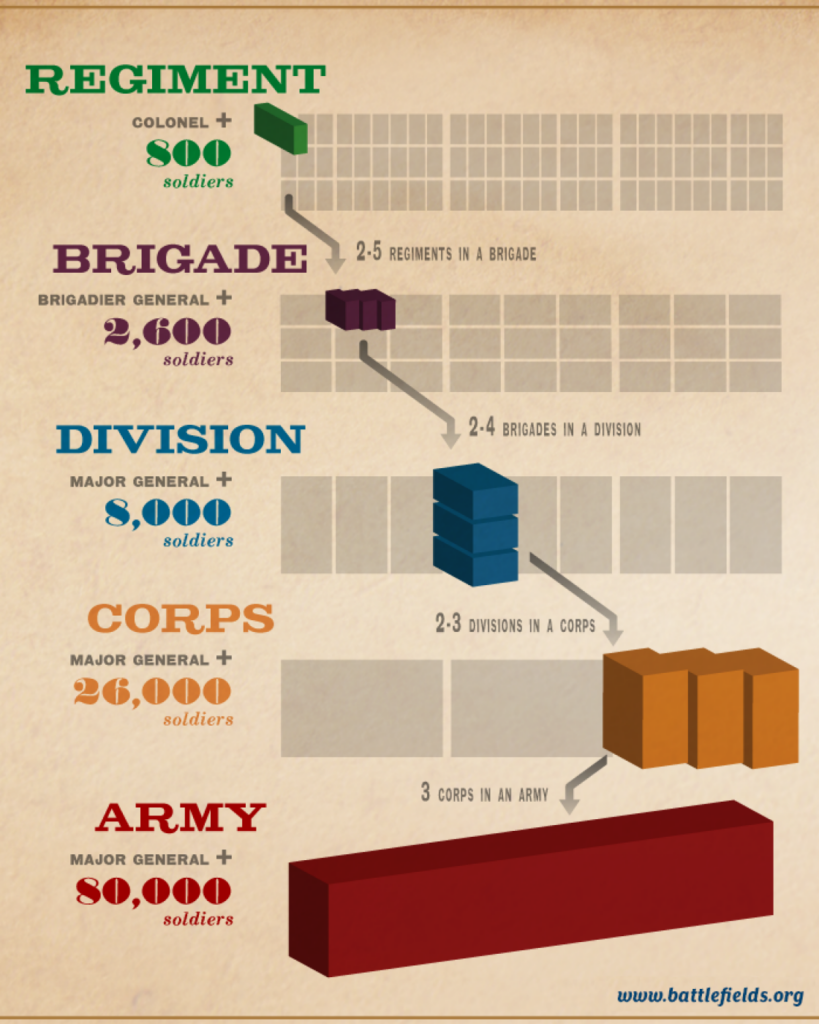

Unless you are an history buff of the Civil War, military organizations might seem a bit mystifying. [26] The regiment was the basic ‘maneuver unit’ of the Civil War at the beginning of the war. As the war progressed, the brigade began as the major maneuvering unit in terms of initiating strategic attacks and defenses.

Regiments were recruited from among the eligible citizenry of one or more nearby counties and usually consisted of 1,000 men when first organized. The attrition of disease, combat, and desertion would rapidly reduce this number as the war progressed. Replacements to regiments were rare for both sides. If a regiment was decimated through heavy casualties, the troops usually were transferred to other regiments. Regiments were usually led by colonels.

A volunteer regiment was made up of ten companies, each company was commanded by a captain and two lieutenants. A company was often filled with men from a single town or county and they elected their officers. Once all ten companies had been organized, they were assigned to a regiment and given a specific number by the state where they lived.

Two or more regiments would be organized into a brigade. A typical brigade consisted of between three and five regiments and was led by a brigadier general. One of the most significant themes in the evolution of Civil War armies was the gradual separation of the three branches. At the outset of the war, it was not uncommon to see a brigade that consisted of infantry regiments, cavalry regiments, and artillery batteries. As the war went on, it became apparent that it was more efficient to have similar regiments (i.e. infantry, calvary) in the same brigade.

Two or more brigades were organized into a division. Divisions tended to be slightly smaller in the Union army–usually two or three brigades. Confederate divisions could include as many as five or six brigades. Divisions were led by major generals.

Two or more divisions would be organized into a corps. A corps typically included infantry, cavalry, and artillery units, the idea being that a corps was a formation that could conduct independent operations.

Two or more corps would be organized into an army which was commanded by a general. During the Civil War the Union most commonly named its armies after rivers or waterways (eg. the Army of the Potomac) while the Confederacy designated its armies after states or regions (eg. the Army of Northern Virginia).

First Stop Washington D.C.

Daniel’s brother William and the 153rd regiment left the state of New York on October 18, 1862. Both brothers may have had similar experiences traveling to the nation’s capital. The trip to Washington D.C. for the 153rd New York Volunteer regiment was their final destination as Provost Guards. The 130th New York Volunteers had a longer journey deep into Confederate territory.

Daniel and William’s lives were to be profoundly changed.

“The life of a soldier in the 1860s was an arduous one, and for the thousands of young Americans who left home to fight for their cause, it was an experience none of them would ever forget. Military service meant many months away from home and loved ones, long hours of drill, often inadequate food or shelter, disease, and many days spent marching on hot, dusty roads or in a driving rainstorm burdened with everything a man needed to be a soldier as well as baggage enough to make his life as comfortable as possible. There were long stretches of boredom in camp interspersed with moments of sheer terror experienced on the battlefield. For these civilians turned soldiers, it was very difficult at first getting used to the rigors and demands of army life. Most had been farmers all of their lives and were indifferent to the need to obey orders. Discipline was first and foremost a difficult concept to understand, especially in the beginning when the officer one had to salute may have been the hometown postmaster only a few weeks before. Uniforms issued in both armies were not quite as fancy as those worn by the hometown militias, and soldiering did not always mean fighting. There were fatigue duties such as assignments to gather wood for cook fires. Metal fittings had to be polished, horses groomed and watered, fields had to be cleared for parades and drill, and there were water details for the cook house. Guard duty meant long hours pacing up and down a well-trod line, day or night, rain or shine, always on watch for a foe who might be lurking anywhere in the hostile countryside.” [27]

Washington city defenses boasted 68 enclosed forts with 807 mounted cannon and 93 mortars, 93 unarmed batteries with 401 emplacements for field guns and 20 miles of rifle trenches plus three blockhouses. [28]

Sources

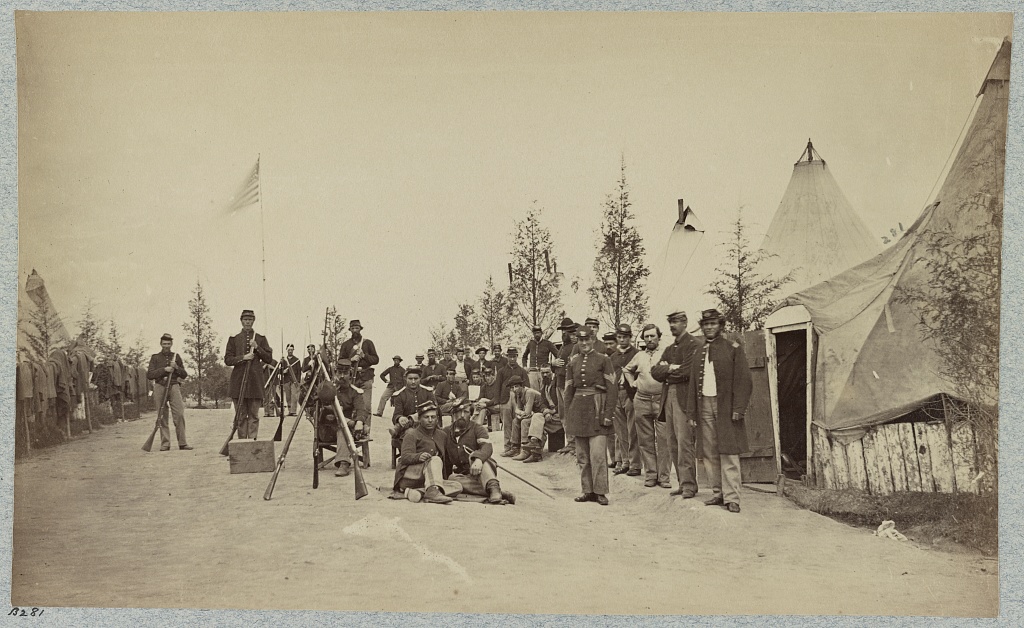

Featured photograph: 153rd Infantry, Library of Congress, photographed between 1862 and 1865, printed between 1880 and 1889, Gift of Col. Godwin Ordway; 1948, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

First photograph in story: Membership medal in possession of William Griffis commemorating duty in the 153rd Regiment during the Red River Campaign

[1] Pension Claim Number 231.631 Joel Griffis, Kingsboro, Fulton Co., NY, father of Daniel Griffis, Application filed May 31, 1877, Adandoned May 8, 1887, U.S. Department of the Interior, Pension Office

[2] Joel Griffis was born October 14, 1807 in Albany , NY and died October 18, 1882 in Gloversville, NY; Margery Gillespie was born 30 Jan 1897 in Schenectady, NY and died 01 May 1850 in Mayfield, NY.

[3] Newspaper announcement: The Schenectady Cabinet, Marriage and Engagement Notices, 2 Mar 1831.

[4] Based on U.S. Federal Census and New York State census data, the father of Joel, Daniel Griffis, possibly Daniel’s sister Esther, and Joel’s brother William Gates Griffis and his family also migrated westward to Mayfield. This household lived close by on another farm. In the 1855 New York Census, Fulton County, Mayfield, Election District 1, Page 499, Line 27, Column 13, Daniel Griffis indicated he had lived in Mayfield for the past 20 years.

Between 1820 to 1840, Mayfield witnessed almost a 30 percent growth in population from 2,025 to 2,615. For historical background of Mayfield, New York, see: History of Mayfield, NY from History of Fulton County, Revised and Edited by Washington Frothingham, published by D. Mason & Co. Syracuse, NY 1892

[5] 1840 United States Federal Census, Mayfield, Fulton County, New York, National Archives and Administration, image 14 of 29 filmstrip.

Enumerators of the 1840 census were asked to include the following categories in the census: name of head of household; number of free white males and females in age categories: 0 to 5, 5 to 10, 10 to 15, 15 to 20, 20 to 30, 30 to 40, 40 to 50, 50 to 60, 60 to 70, 70 to 80, 80 to 90, 90 to 100, over 100; the name of a slave owner and the number of slaves owned by that person; the number of male and female slaves and free “colored” persons by age categories; the number of foreigners (not naturalized) in a household; the number of deaf, dumb, and blind persons within a household; and town or district, and county of residence.

[6] Headstone Inscription: “WIFE OF JOEL GRIFFIS” “IN HER 39 YR” Burial: Riceville Cemetery Mayfield Fulton County New York, USA Created by: Katherine MacIntyre Record added: Aug 08, 2012 Find A Grave Memorial# 95024757

[7] 1850 United States Federal Census, Mayfield, Fulton County, New York, National Archives and Administration, page 28, lines 31-37

[8] 1850 United States Federal Census, Mayfield, Fulton County, New York, National Archives and Administration, page 38, lines 6-10

[9] 1855 New York Census, Johnstown, Fulton County, Election District 2, Sheet 369, Line 15, June 1855

[10] Mayfield Central Presbyterian Church Records, contributed by James F. Morrison and transcribed by Mary Beth Johnson, January 31, 1856.

[11] New York State census, Mayfield, Fulton County, New York , June 5, 1855 Page 502, line 1.

[12] Headstone Information – Birth: unknown Death: 1861 Inscription: “WIFE OF DANIEL GRIFFIS” “AGE 27” Burial: Riceville Cemetery Mayfield, Fulton County New York, USA Created by: Katherine MacIntyre , Find a Grave

[13] Baptism of Fire A Call to Arms: Recruiting and Enlistment of the Civil War Soldier, Manassas National Battlefield Park, National park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior

[14] Civil War Soldiers: Information and Articles About Soldiers in the Civil War, history.net

[15] John Sacher, Conscription, Essential Civil War Curriculum, Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Tech, (Online) May, 2012

[16] New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900, 1st Dragoons, Page 609

[17] In a September 28, 1877 affidavit from Joel Griffis for obtaining a pension from Daniel’s military service, it was also indicated that the 70 dollars “he had earned by his labor just before enlisting and left it with him at time of his departure with said Bristol at Springwater” (September 28, 1877 Affidavit of Joel Griffis, Claim No. 231.631 filed by J. Reck. Ally, Johnstown, NY)

[18] First Dragoons Regiment, Civil War New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, NYS Division of Military and Naval Affairs, Last modified: February 8, 2018

[19] James Riley Bowen, Regimental History of the First New York Dragoons: Originally the 130th N. Y. Vol; Infantry; During Three Years of Active Service in the Great Civil War, originally published by author 1900, Reprinted by Forgotten Books, 2012, Page 89.

[20] Ibid, Page 7

[21] New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900, 153rd Infantry, Page 257

[22] 153rd Infantry Regiment, Civil War New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, NYS Division of Military and Naval Affairs, Last modified January 24, 2018

[23] Wakeman, Sarah Rosetta and Lauren Cook Burgess. An uncommon soldier : the Civil War letters of Sarah Rosetta Wakeman, alias Private Lyons Wakeman, 153rd Regiment, New York State Volunteers. Pasadena, Md: The Minerva Center, 1994. Page xi

[24] Tsui, Bonnie, She Went to the Field: Women Soldiers of the Civil War. Guilford: Two Dot, 2006, Page 46-47

[25] Boatner, Mark M. III (1959). The Civil War Dictionary. New York, N.Y.: David McKay Company.

[26] See: Civil War Army Organization, Americancivilwar.com, original source was from National Park Service, Gettysburg National Military Park, Gettysburg, PA;

Civil War Army Organization, American Battlefield Trust;

From Regiment to President: The Structure and Command of Civil War Armies, National Park Service, updated August 14, 2017;

Armies in the American Civil War, and Union Army, Wikipedia;

Heiser, John, credited author, Gettysburg National Military Park, Anchor: A North Carolina History Online Source, Appendix K: Organization of Civil War Armies ;

Wolfe, Brendan, Military Organization and Rank During the Civil War, Encyclopedia Virgina, Library of Virginia, 27 Oct. 2015. Web. 11 Jan. 2021, First published: October 5, 2009, Last modified: October 27, 2015; Faust, Patricia L., ed. Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1986; reprint, New York: HarperPerennial, 1991

Armies in the American Civil War, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 14 November 2020 and accessed on December 28, 2020

[27] Tanner, Robert G. Life of the Civil War Soldier, thomaslegion.net. Page accessed January 10, 2020.

[28] Washington City: Defenses Surrounding the City, American Battlefield Trust