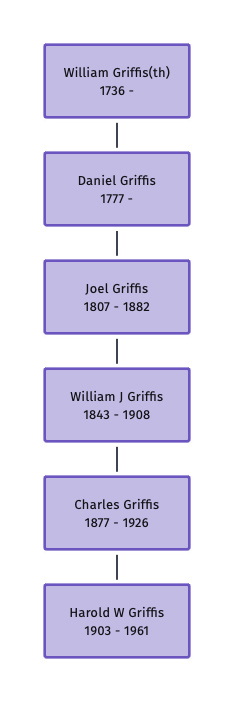

To date, I have pushed our knowledge of the Griffis surname for our particular family back to a William Griffis(th) who was baptized on June 6, 1736 in Huntington, Suffolk County, New York. There are other branches of our family that can be traced further back in time but information on the Griffis lineage becomes blurred before 1736.

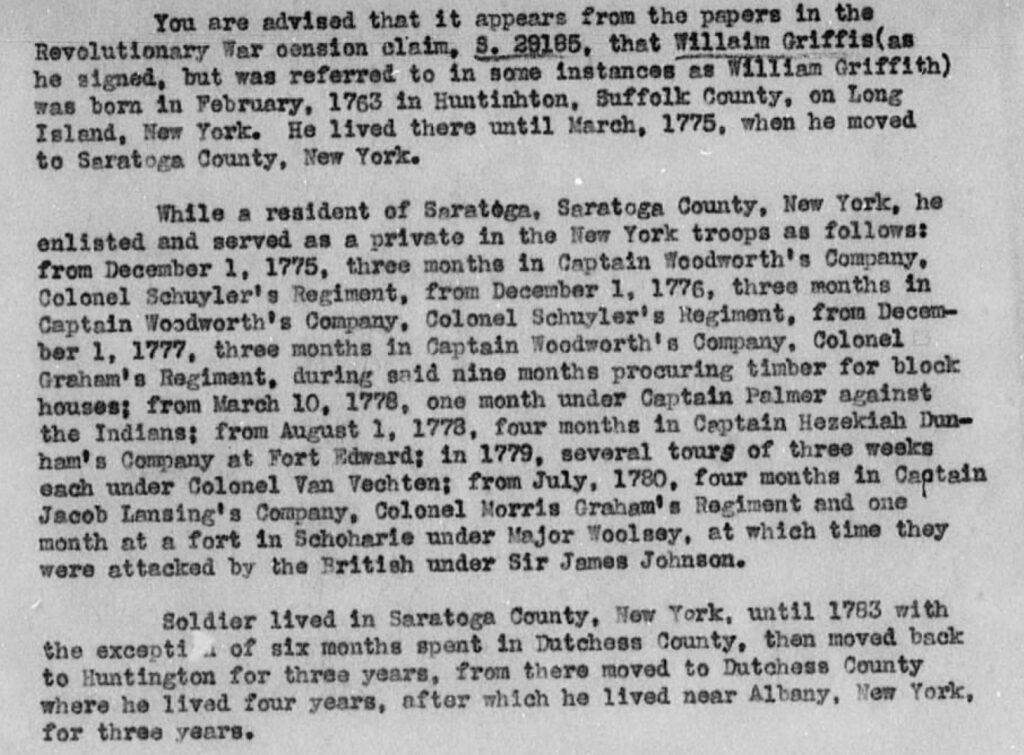

Based largely on the five following factors or sources of information, I was able to identify corroborating documentation of our lineage back to William Griffis(th):

- the realization and recognition that the surname changed over time;

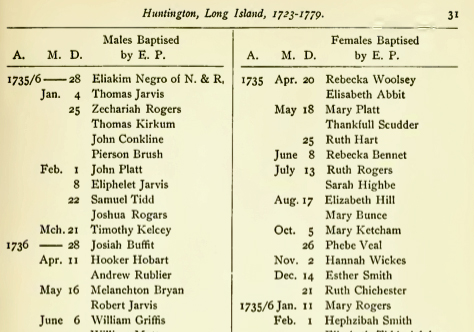

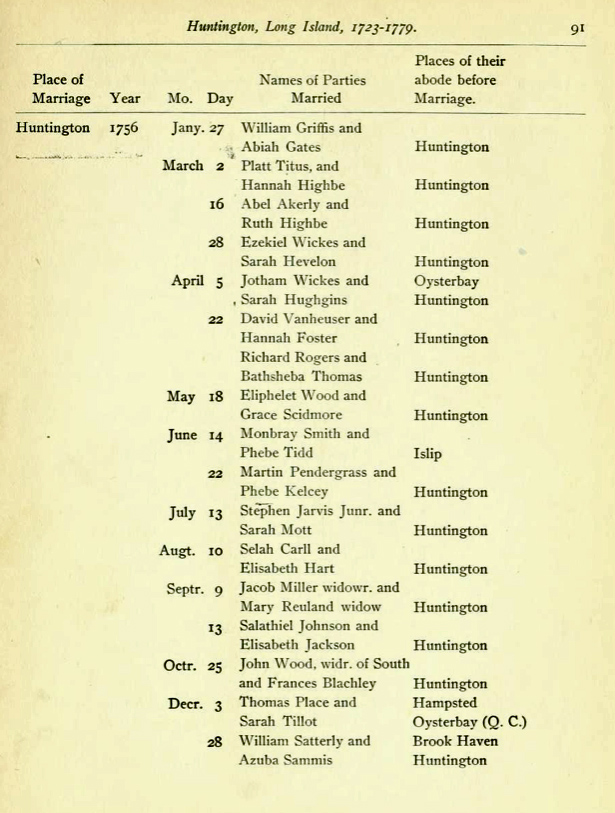

- the records of the First Church in Huntington, Long Island provided baptism and marriage records related to family members (pictured below);

- the information from three manuscripts on the Griffis(th) family of Huntington provided corroborating facts and additional information on various Griffis(th)(es) family branches;

- the discovery of family trees on the internet listing William Griffis(th) and his 12 children; and

- Federal and New York state census data.

No one who has had any significant involvement in family research can fail to have been challenged with the tracing of family surnames through the generations. This is especially true if you are tracing a family name in the American colonies before the United States of America became a nation and the family name is purportedly a Welsh surname. My personal journey of attempting to trace the Griffis family back in time has had its host of success stories. I have hit numerous dead end leads over 20 plus years and I have had a few surprises along the way.

This story focuses on my experience (of lack thereof) and perceptions on the research process that led me to William Griffis. I am the first to admit that the more I learn, the less I know.

Part one of this story may get a bit too deep for those who are simply interested in what is currently considered ‘family facts and interesting family stories‘. In that case, you may wish read the ‘Synopsis’ and jump to the last sections of this story for the facts and stories. On the other hand, hopefully the story will provide a sense of what happens when one starts down the path or rabbit hole of tracing a surname. The story conveys the level of my obsession with family research and provides a few interesting facts along the way.

This is part one of the story of tracing the Griffis surname. It deals with the challenges of documenting a name back into the 1600’s and prior centuries. Part two deals with my path of tracing the surname and family back from recent generations to William in 1736. The third and fourth parts of the story discuss how the spelling of the Griffis name for this specific family changed between and within generations in America for two or three generations, underscoring the fluid nature of simply using a last name. I have yet to find a source that explicitly delineates the changes of the surname through William’s descendants so I hope this information will be useful for future family research on this family from Huntington, Long Island.

Synopsis: Here’s the ‘Punch Line’ to the Story

The following provides the major conclusions gleaned in this three part story regarding my current efforts for tracing the Griffis surname back in time.

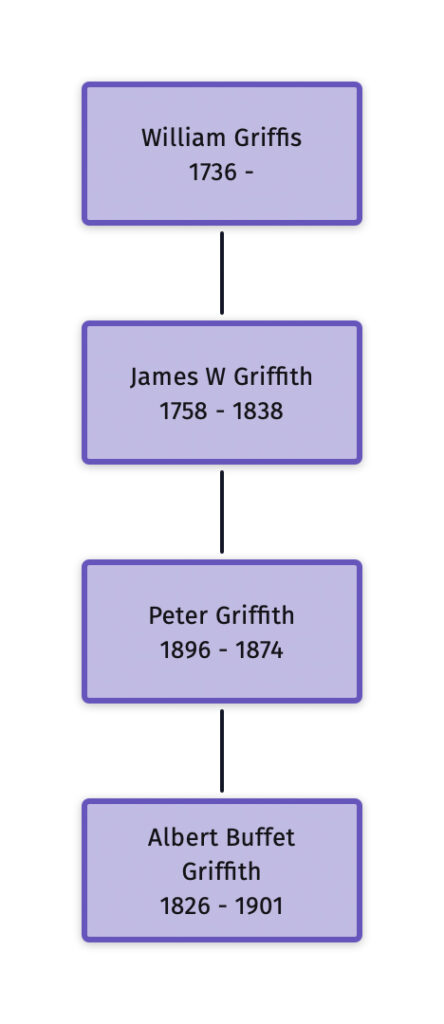

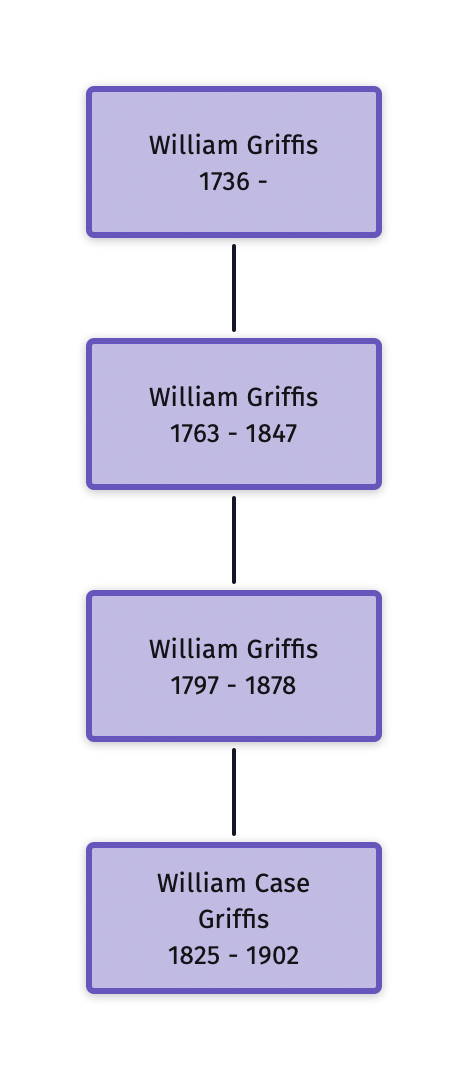

The furthest back that I can reliably trace the family surname is to a William Griffis. He was baptized June 6, 1736 in the First Church of Huntington, Long Island by the Reverend Ebenezer Prime. Based on family folklore, the family name was originally Griffith.

“According to family legend, as told by Albert Buffet Griffith to his daughter-in-law, Lillian Soper Griffith, William Griffith had difficulty pronouncing the ‘th’, and in a name or word the ‘th’ sounded like an ‘s’. As this speech impediment was an embarrassment to him, he allowed the clerk to record his name as Griffis rather than confessing the spelling was Griffith which would have called the clerk’s attention to the impediment.” [1]

While I do not doubt Albert Griffith’s conviction and belief about what he was told perhaps by his father or grandfather, this is a very interesting family story about how the family surname changed. The story, however, does not explain why William’s name was written as ‘Griffis’ when he was baptized by Reverend Prime in 1736. I imagine the lisp happened way after the baptism. While we can not definitively state what variation of the surname was used by William when he was living or if he indeed had a lisp, the few known records of William point to the use of surname Griffis. His 12 children and grandchildren, however, have spelled their surname various ways: Griffis, Griffith, and Griffes.

Since William Griffis was baptized in 1736 in Huntington, New York, it is assumed he was born in Huntington and his father or grandfather emigrated to the British colonies. This would imply that his unknown ancestors conceivably emigrated between the mid-1600’s or possibly as late as the early 1700’s.

Based on oral family stories and the variability of surname spellings of William’s twelve children and grandchildren (e.g. Griffith, Griffis, Griffes), the name was originally Griffith and the family came from Wales. The various different spellings of the surname within and across generations subsequent to William Griffis is reflective of the historic process of the receding influence of Welsh patronymic practices of conferring personal and family names.

In Wales, the use of surnames did not predominate until the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In the greater part of Wales, the ancient patronymic naming system continued: having children identified in relation to their father. This meant that surnames in the 1600’s and and 1700’s did not take on the weight of significance that they have for present generations. Using a surname was similar to using a first name, they changed based on what was conferred by prior generations and also what one wanted to use as a surname. For our family, William’s decendents used the surnames of Griffis, Griffes and Griffith.

Click for larger view.

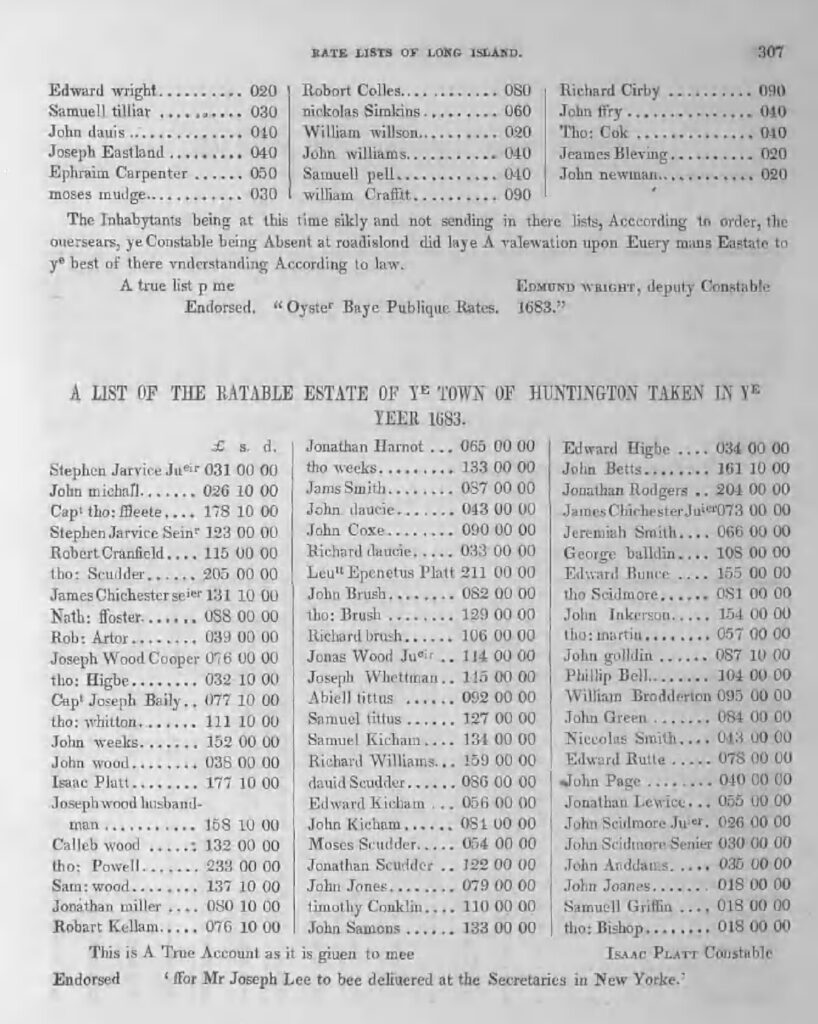

It would appear that either William’s father or grandfather were the original family emigrants to the colonies. Contrary to a wide range of Griffin(th)(ths)(is)(es)(in)(ins)(ing) American family genealogies, William’s ancestors were probably not descendants of a Edward Griffin or a Richard Griffin. There are references to a Samuel Griffin (Grffing)(Greffith) (Griffith) who lived and owned land in Huntington Long Island in the late 1600’s but there is no definitive proof that he is William’s grandfather or father or was related to the family.

However, family folklore indicates that Albert Buffet Griffith told his daughter-in-law, Lillian (same individuals referenced previously), that

“his great, great grandfather’s name was Samuel”. [2]

If Albert Griffith’s recollections are true, then William’s father was perhaps Samuel Griffith.

While not certain, a plausible argument that is subject to further research is that William’s ancestors, perhaps from southern Wales, traveled from Bristol to Boston or another northern port. Another possibility is that his ancestors may have emigrated to London and from there traveled to the colonies. He or his family initially settled in Massachusetts or Connecticut as early as 1630-1640. He or his family then emigrated to Huntington as part of a series of emigrant waves to populate newly established English towns on Long Island. Another avenue of leads is based on research and review of ship manifest lists which could reveal possible ancestors, three were named Samuel Griffith who arrived in 1681 (Maryland), 1701 (Pennsylvania), and 1720 (Maryland), as well as other individuals with the name of Griffith.

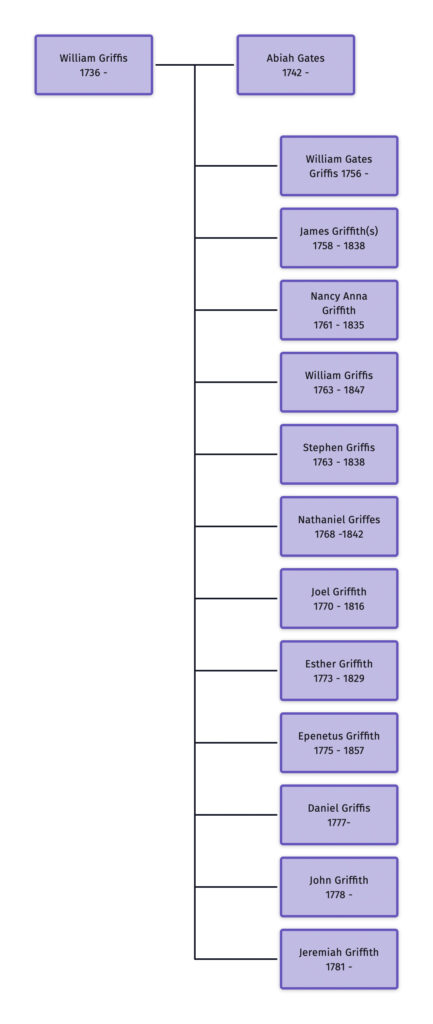

There is documentation that William Griffis married Abiah Gates on January 27th, 1756 in Huntington. They had 12 children, ten sons and two daughters. Two of the sons, James (second born) and William (fourth born) fought on the ‘patriot’s’ side in the Revolutionary War. Documentation of his sons and daughters are partly based on baptism records and family family manuscripts. Their oldest son, William Gates Griffis, also possibly fought on the patriot’s side in the Revolutionary War. (Yes, they had two sons named William.) Two of the children were born 10 months apart (William and Stephen).

William and Abiah appeared to have lived in Huntington for most of their lives, possibly their entire lives. They and family members that were not emancipated and living on their own lived in Huntington through a period that witnessed the British occupation during the Revolutionary War and, subsequent to the war, the birth of our nation. While many Long Island families sympathetic to the colonies’ independence fled to Connecticut or upper New York during the Revolutionary War, there is no evidence that the Griffis family fled during the occupation despite having two or three sons fighting on the patriot’s side.

Our direct descendent, Daniel Griffis, was the 10th child and 8th son of William and Abiah. William was about 41 years old when Daniel was born on April 1st, 1777. William was born during the British occupation of Long Island during the Revolutionary War.

William and Abiah had two additional sons, John and Jeremiah, while living under the British occupation during the Revolutionary War.

Little is known of William’s life, death or burial. A review of various historical accounts of Huntington and available historical records reveal little about William or Abiah. A review of documentation related to various Huntington cemeteries has provided no leads. If he died prior to 1782, the absence of information related to William Griffis’ burial or death may be due to the decimation of the Huntington church and its grave site in 1782 by the British during the Revolutionary War. If he died after the Revolutionary War, there is no evidence of a tombstone in local graveyards. There also is no known documentation related his death or a known will. There is no known documentation for the death of his wife, Abiah Gates.

The ability to trace the family surname backward from Harold Griffis through his father Charles Griffis, his grandfather William James Griffis, his great grandfather Joel Griffis and his great great grandfather Daniel Griffis was primarily based on the review of Federal and New York state census records. While we presently do not have a complete picture of Daniel Griffis’ entire family, we know there were at various times in the mid 1800’s four Griffis families in the small town of Mayfield: one headed by Daniel, another by William Griffis, one headed by Joel Griffis and another headed by Ensign Griffis.

A number of facts pertaining to (1) Daniel Griffis; (2) his older brother Nathaniel Griffes (he spelled the surname differently); (3) Daniel’s son William G. Griffis; and (4) Daniel and Nathaniel’s uncle Stephen Gates and his sons Stephen Gates Jr. and Daniel Griffes Gates appear to provide supporting evidence of a connection with the Griffis Mayfield, New York families and William Griffis in Huntington, Long Island, New York

- A family manuscript (the “Peets-Welsh manuscript” referenced below) and a manuscript by Martha K Hall, Griffith Genealogy: Wales, Flushing, Huntington indicate that Daniel was a son of William Griffis and Abiah (Gates) Griffis and was born April 1, 1777 in Huntington, Suffolk county. Both manuscripts also list the children of William and Abiah Gates Griffis.

- In the 1855 New York state census, Daniel Griffis reported that he was born in Suffolk County in 1776, based on a reported age of 79, and that he lived in Mayfield for 20 years.

- In the same 1855 census for the small town of Mayfield, New York, William G. Griffis and Joel Griffis indicate that they both were born in Albany county and had lived in the Mayfield, New York area for 20 years. This implies that Daniel, William and Joel moved to Mayfield about 1835 from the Albany-Schenectady area.

- In addition, William Griffis’ headstone in the Mayfield Riceville cemetery indicates his middle initial was “G”. I believe the “G” stood for Gates, a reference to his grandmother’s maiden name.

- The 1820 Federal Census for Niskayuna, Schenectady County, lists three ‘Griffies’ families in close proximity based on the census taker’s enumeration path. It is assumed the census enumerator misspelled their names. In addition, between two of the the ‘Griffies’ households, one headed by Daniel and another headed by Nathaniel, is a household headed by Steven Gates. Based on the above mentioned manuscripts, Nathaniel is Daniel’s older brother. Steven Gates (b. 1750 d. 1837) was Abiah Gates’ brother. Steven Gates is found living in this area in the Federal Census in 1790 through 1830. There is also a household one house away from Nathaniel’s that is headed by an Ensign Griffies. The 1820 Census also reveals an older Steven Gates. The composition of the four families that live close to each other reveal an older Gates family surrounded by younger Griffis families. Nathaniel was about midway in age between Stephen and his sons, Stephen Gates Jr. and Daniel W. Gates. Stephen Gates named a son Nathaniel Griffis Gates. Nathaniel Griffes (he spelled his name differently) names Daniel W. Gates as one of his executors of his will. The connection was one of mutual trust and affection between family members.

In the 1850 Federal census, an Esther Griffis is living in Daniel Griffis’ household. Esther is reported to be 86 years old which would imply that she was born in 1764. It is not known if this is his wife or possibly his sister who was born in 1773.

Joel Griffis was one of Daniel’s sons. Joel and his wife, Margerie, were married in Watervliet, New York in 1831. Watervliet is in Albany county. There were seven children in the family, four sons and two daughters. Daniel was the oldest (born 1832), followed by Stephen (1834), Joseph H. (1836), Margaret Mary (1838), William James our direct descendant (1843), Ruth Addie (1845) and Francis (1850). Based on the birth locations of the children, it appears the family moved from the Schenectady, New York area to Mayfield, New York around 1835. The two older sons were born in the Watervliet – Albany New York area while the remaining children were born in Fulton County where Mayfield is located. It appears that Joel and Margery along with other Griffis family members, notably his father Daniel Griffis (1777 – ) and brother William G. Griffis (1805- 1860), migrated westward from the Albany Schenectady area to the rural areas of Mayfield in 1835 to live life initially as farmers.

Surnames

My father told me when he was traveling around the country for work he would often pick up a local telephone directory (this was back in the 1960’s) and look up the Griffis name to see if there were any individuals with our surname. He would be surprised to find a Griffis among the Griffiths, Griffith, Griffen, Griffin, and other variant spellings listed in the telephone directories. Griffis is an unusual spelling of the Griff variant and he usually did not find many.

Surnames in our contemporary world signify many things and have a bearing on our social, religious, legal and cultural lives. Surnames give us a personal sense of identity with a family group and a grounding in a personal history of our family.

Those interested in history itself often find it best illuminated when seen through the life of one person, an ancestor with whom we have some commonality of feeling by virtue of no more than a shared surname or location, or a half-remembered family story. [3]

In Europe, the use of surnames became popular in the Roman Empire and expanded throughout Western Europe. During the Middle Ages, the practice of using surnames died out as Germanic, Persian and other influences took hold. During the late Middle Ages surnames gradually re-emerged, first in the form of bynames, which typically indicated an individual’s occupation or area of residence, and gradually evolving into modern surnames. [4]

The surname of Griffis is actually a variant of the name Griffith, and its Welsh form of Gruffudd or Gruffydd. It is a traditional name of Welsh origin that was originally used as a personal name and eventually used as a surname, with or without the ‘s‘ as in Griffiths. [5] The name has many variations as a result of the natural evolution of the name in Welsh, as well as the translation of the name from Welsh into both Latin and English. Common variants include Griffin, Griffith, Griffiths, Griffing, Griffes, Griffis and other variations. The anglicized and Welsh forms are treated as different spellings of the same name in Wales.

“This ancient Welsh surname derives from the Old Welsh personal name “Grippiud”, which gradually developed into “Griffudd”, and “Gruffudd”, and the early standard form “Gruffydd”. The normal pronunciation of the name in South Wales became “Griffidd”, and those medieval scribes who were not Welsh generally wrote “Griffith”, as being the closest phonetic spelling within their writing system. This form, Griffith, and Griffiths the patronymic came to be used almost universally, as forename and surname, throughout Wales. The first element of the name, “Griff”, is of uncertain origin, but is thought to mean “strong grip”, with “(i)udd” the second element meaning “chief, lord”. “ [6]

Although there is documentation that ‘ancient’ Griffith families came from north Wales, there were in fact documented more Griffiths throughout Wales and across the border in England. [7]

The Challenges of Tracing Surnames

Prior to the inception of state and federal government organizations, records about families and individuals were largely limited to local towns and cities. Records were usually focused on land ownership, taxes, the conveyance of assets through wills, bankruptcy announcements, court announcements in local newspapers; and religious records that documented birth, baptism, marriages and death. If you were fortunate to have family bibles or personal correspondence, you could piece together a path of the lineage of a surname. Surviving tombstones in the 17th and 18th centuries in local grave yards also provide great clues if they have survived through time. While mistakes can be made chiseling a name in stone, there is a greater likelihood of making mistakes on paper.

Regardless of the source and general historical dates of records, assuming the surname has not changed through generations overtime, one faces challenges of the name being properly transcribed in various governmental, legal or social documents; newspapers; and other publications. Often, one finds a census taker or local town scribe writing a surname in a different manner. It is not uncommon to find different spellings of a last name for the same person in various historical documents.

If the surname has changed from generation to generation, this adds another twist in trying to tie the present to the past. This is especially the case with Welsh families and surnames. One may find not only changes between generations but minor modifications within generations of a family as is the case with our ‘Griffis(th)’ family.

Reviewing a wide range of written genealogical work on Griffin(th)(ths)(es)(ing)(s) family lineages had led me to question the validity and veracity of many of the genealogical stories and family trees found on the internet and in paper documents. For example, the author of one published volume on a Griffith family in Kentucky claimed:

“To my knowledge this is the first book published with a compIete pedigree of this Griffith lineage from year 100 through 1979” [8]

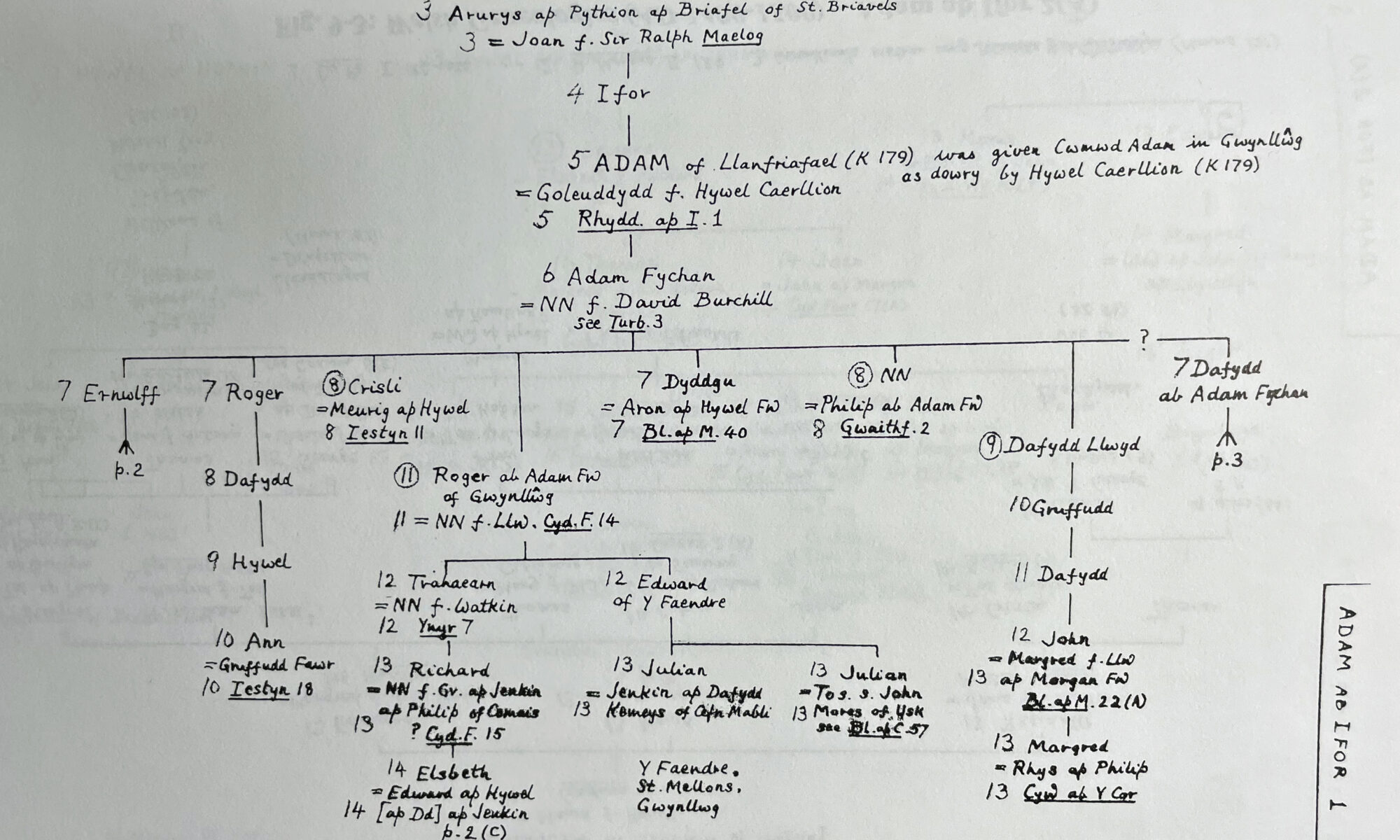

Tracing one’s ancestors back to the year 100 is indeed a daunting task that perhaps raises more questions concerning the veracity of sources. (See my reference to the Feature Photo for this story below.) Many of the documented pedigrees of Welsh families in the medieval times that family genealogists rely upon were of gentry and nobility. Most of the ‘common folk’ were tenant farmers and while many took the names of the gentry that they worked for or lived nearby, the documented pedigrees are not their pedigrees. The author referenced above does state, however, a few paragraphs later:

“Remember in any genealogy we can not always be sure of all the information that we find, and there is no way ALL the information can be checked or proven in every family line. Most sources are reliable but many are not. When in doubt do your own research.” [9]

Sage advice. My skepticism of past research is echoed by others and occasionally stirs up some lively debate which devolves into ad hominem arguments. [10] I can envision a Monty Python skit reenacting a spirited debate on Griffin(th)(ths)(is)(es)(in)(ins)(ing) ancestors. One of the commentators of an ongoing discussion has labeled these family trees as “The Welsh Trees R Us”. [11] While I may find humor in all of this, it reflects the deep intellectual and emotional commitment of many in trying to document their family genealogy.

Many of the Griffin(th)(ths)(es)(ing)(s) family trees rely upon unpublished, handwritten or typewritten manuscripts and a few key, published works which were written in the 1800s and 1900s. Many of the unpublished manuscripts simply list a lineage of individuals that have different spellings of a surname with no explanation of how they are linked or lack corroborating facts and specific research sources. The reader must assume that one generation is linked to another.

There is a tendency among family genealogists to latch on to those few sources of available information about individuals that have been discovered by others and to tie one name (person) to another. The result is one finds a number of specific individuals, documented in many articles, books and manuscripts that are repeatedly referenced as proof of a family lineage in a wide range of different family trees. These common ‘family’ ancestors become the ‘Adam and Eve of family trees’. This is especially the case with internet based family trees. The only reason why these individuals are referenced in so many disparate family trees is due to the archival fact that specific documents have withstood the test of time and have not perished. There is an absence of information on other souls so researchers grab onto what exists.

When doing research I have been prone to the practice of attaching an individual I discover on the internet or in a manuscript to a part of my family tree. I may connect a piece of information to a person or a new person onto the family tree for future research. I, however, should indicate whether this is a confirmed fact or requires further research since my documentation is public. To be fair to all who maintain internet based family trees, it is a community that shares information something akin to a wiki. Like a wiki, while information is freely shared and hopefully well documented, there is a need for critical thought and analysis.

The fact that many of these authors were able to locate as much information without the access to and use of modern online databases is laudable. I certainly do not believe any of these authors intended to deceive anyone with their assumptions, leaps of faith, or suppositions. They only had access to a small pool of documents or were limited in terms of visiting on-site sources of information. Some of the authors relied on oral family knowledge which in itself is of great value. They drew conclusions, albeit inconclusive ones.

I continue to rely upon their work for further leads in research. However, the conventions for documenting sources, which are much more rigorous than simply citing an assertion, call for the need to validate, in some fashion, the facts presented in previous family histories. What criteria satisfies ‘valid’ facts is a debatable issue. I am simply echoing a line of thought that has informed the research of Theresa Griffin about the Griffin family. [12]

Based on available historical genealogical data, the majority of family genealogists will be challenged to trace and document their respective family lineages beyond a certain point in time. As one goes back in time, fewer documents are available. The ability to locate written observations, documents, town records, church records or family records in the 1600’s or prior is largely based on persistence, focused disciplined research, typically going onsite to specific places to unearth records and just pure luck. If records are found, the added challenge is being able to decipher handwritten documents.

” (T)he majority of … people led quiet, blameless lives and left very few traces, and almost all sources of biography come with collision with authorities. This tends to be for purposes of registration (birth, marriage, death, census, taxes, poor relief, etc) or for legal reasons, whether criminal… or civil. “ [13]

The upshot of all of this is that research oftentimes leads you down paths ending at dead ends or to conclusions that you did not anticipate or fit your vision of what you believe is fact. Also, one’s family surname is not necessarily a static name or reference point to help you journey backwards in time. For many families, surnames change across and within generations. Tracing one’s ancestors through a surname can be messy, confusing, frustrating, and lead to to dead ends.

The Use of Surnames in Wales

Surnames in England emerged between the 12th and 14th centuries. A completely different historical trend existed in Wales. In Wales, surnames did not take on any scale until the sixteenth century. In the greater part of Wales, the ancient patronymic naming system continued: having children identified in relation to their father. This is comparable to the Patronymic system that led to the adoption of surnames from personal names in England and similar parallels can be found in other parts of Europe. Patronymic names in Wales changed from generation to generation, with a person’s first name being linked by ap, ab (son of) or ferch (daughter of) to the father’s name. The patronymic naming system could be extended with names of grandfathers and earlier ancestors, to perhaps the seventh generation. [14]

With the Acts of Union (1536-1543), the Welsh became fully subject to English law and administration. and became subject to the pressures to conform to English practices regarding the use of surnames. The first to adopt a permanent surname were the wealthier classes of Welsh under the pressure of the English bureaucracy. The practice filtered through Welsh society at different levels and periods of time. The next stage of transition toward the systematic use of surnames in Wales occurred when the second name under the patronymic system was passed on more or less unchanged to later, successive generations. It was not uncommon for a surname that seemed to be fixed in a family would still be liable to change from generation to generation. [15]

“The whole process of adopting fixed surnames was completed in different communities in Wales, evolving gradually and only rarely being the result of conscious decision, let alone legislation. Generally speaking, such surnames were taken earlier in the lowland areas, especially in the east and south of Wales, later in the upland areas; earlier among the gentry, later among laboring people. However, other factors were the degree of anglicization and urbanization in an area.” [16]

The most prevalent Welsh surnames derive from the former patronymic system. Sons took a surname based on the given name of their father, which changed each succeeding generation. Griffith, and its native form Gruffydd was initially used as a first name and then as a surname.

In studies of Welsh forenames in use in Wales in the fifteenth century, it has been noted that Welsh forenames were fading while ‘new’ Anglo-Norman names were growing. However, among the ‘traditional’ Welsh forenames that were continued to be used, Gruffudd represented 6 percent throughout Wales. The modern derivative, Griffths, continued to be used throughout Wales. For comparison, the figures for surnames in Wales between 1813-1837 indicate that Griffiths represented 2.8 percent of the Welsh population. [17]

The ten most common surnames in Wales in 1856 were Jones (13.84%), Williams (8.91%), Davies (7.09%), Thomas (5.70%), Evans (5.46%), Roberts (3.69%), Hughes (2.98%), Lewis (2.97%), Morgan (2.63%) and Griffiths (2.58%). [18] Of these ten, only five were found throughout Wales and did not display any marked concentration in any one area: Thomas, Lewis, Griffiths, Edwards and Morris. Other common surnames included Owen, Pritchard and Parry. The popular given names from which these surnames derived, such as Jones from John, and Davies from David, clearly depict the patronymic practice. While these figures reflect all of Wales, there have been studies which document that different areas of Wales have different levels and mixtures of surnames. [19] For example:

“(T)he ten most common names in the Uwchgwyrfai area of Caernarfonshire covered more than 90% of the population. those names (in the early part of he nineteenth century) were: Jones (22.8%), Williams (18.40%), Roberts (13.28%), Hughes (7.78%), Griffiths (7.39%), Thomas (5.37%), Owen (4.86%), Evans (4.17%), Pritchard (3.65%) and Parry (2.92%).”

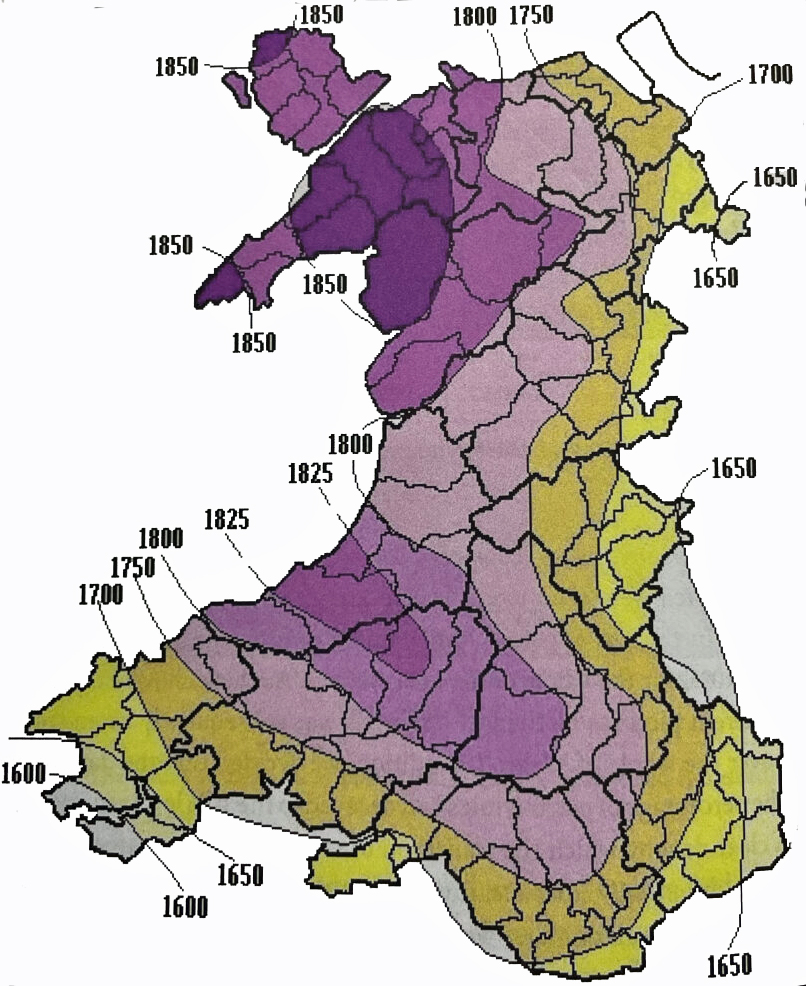

In a study of Welsh wills between 1590 and 1809, John and Sheila Rowlands documented ‘patterns of decay’ in the use of the patronymic naming system in Wales. [20] They completed a study aimed at providing a means of determining areas in Wales when the use of the patronymic naming system reduced to about 10 percent of the names in a given area.

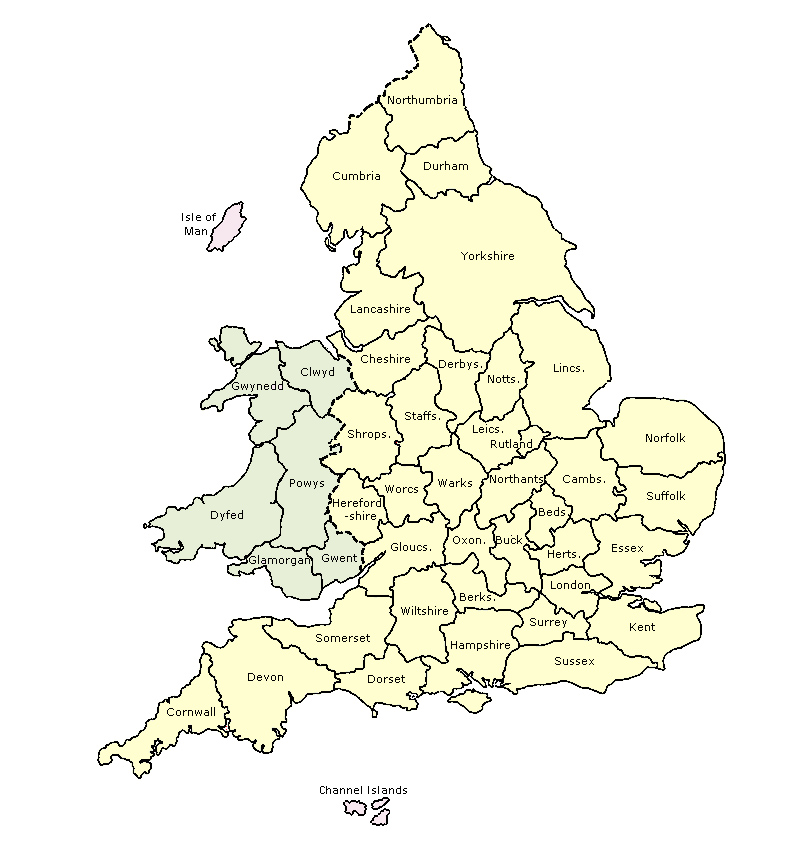

The map above, which is from their study, illustrates the wide variation when surnames were adopted in various parts of Wales. Surnames became the norm by 1750 across the coastal plain of south Wales and along the eastern border with England. The use of surnames was also widespread in the coastal area of Gower (Glamorgan – see map of England and Wales below), Monmouthshire (Gwent), and Flintshire (Clwyd on the map below).

It was not until the mid-nineteenth century that the Patronymic system was fully replaced in Wales. When the Welsh immigrated to America in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the patronymic pattern eventually stopped, and their surnames became hereditary. However, it is not uncommon to find variations of surname spellings within and between family generations in documents associated with our family members in the 1600’s and 1700’s in the colonies.

Welsh in the American Colonies

Aside from the Dutch and French, the Welsh together with the Scotts and English were some of the earliest colonists to arrive in America. [21] Many of the Welsh that came to the colonies were either residing in England or southern Wales. The southern region of Wales, located just across the Bristol Channel from what was then England’s second largest port city, Bristol, supplied thousands of emigrants to England during the 17th and 18th centuries. “Estimates suggest that at least 6,000 Welsh-born persons had settled in London in the early seventeenth century, amounting to some seven per cent of the capital’s resident population.” [22] To a large degree, the Welsh that initially immigrated with the English to the colonies in the 1600’s came from the English ports of Bristol and London. [23]

The first major attempt to establish a Welsh settlement in the ‘New World’ was initiated by William Vaughan who, at his own expense, attempted to establish a foothold in Newfoundland in 1617. The settlement, called, Cambrial, was unsuccessful and was eventually abandoned in the 1620s. For the next century, the areas that eventually became Canada and the American Colonies and the West Indies were the targets for all emigrants from Wales. [24]

The influx of the first major wave of Welsh immigrants to America began in the mid to late 1600s. While there were movement of individuals, the majority transferred in denominational groups and settled together in small communities. Between the Restoration (1660) and the turn of the century, it is estimated that about 3,000 individuals of Welsh descent came to the colonies. [25] It is not known how many arrived prior to 1660.

“During the period from 1618 when Britain had a mere toe-hold in New England, to the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, there was no particular Welsh flavor to the development of the trans-Atlantic colonies… (m)any of those who made the crossing did so for land and trade and, to a large degree, were Anglican gentry; others were criminals and indentured servants. Some few people from Wales did emigrate during the Laudian persecution of the 1630s to gain religious and political freedom and were active in New England in the 1650s in evangelical reform. … At the same time, Wales was experiencing extreme economic problems. To a much greater extent than England, Wales consisted of a multitude of small tenant farmers whose plight was worsening with the concentration of land and power in the grasp of a prospering minority. … It is against this background that the first sizable emigrations from Wales occur, though quality rather than quantity is the keystone. ” [26]

In addition to the ‘push’ factors that influenced emigration (e.g. religious and political persecution, environmental factors, disease, poverty, etc.), some of the ‘pull’ factors of emigration to America were the availability of ship lines traveling to the colonies from various English ports and the economic and religious opportunities available in particular areas managed under different land management companies. Colonial government differed widely from colony to colony. In some colonies, a tremendous amount of authority was vested in the proprietary rulers to whom the crown had granted charters (Virginia and Maryland). In others, power was widely dispersed among the colonists (Massachusetts and Connecticut). There were three classes of colonies established in the Americas by the British: Royal (owned by the King); Proprietary (land grants given by the British government) and Charter (charters were granted to the colonists by the king through a joint-stock company and were usually a self-governing colony). [27]

The comments by Bruce Durie on tracing Welsh ancestry in Wales also reflects on the similar challenges of tracing ancestors in American colonies in the 1600’s and 1700’s.

“Most genealogical research stalls somewhere in the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries. Between the 1500s and the 1830s to 1840s (the beginning of statutory regulation, the censuses and much else, as the Victorians set about organizing a secular society) not everyone will be recorded, especially Nonconformists and the poor, particularly in both sparsely populated areas and the densely packed centers of very large town and cities. Remember that it was mainly baptisms (not births) which were noted in the parish registers, and the same goes for the other sacraments – proclamation of marriage (banns) rather than the marriage itself, and burial or mort-cloth (shroud) rental rather than death.” [28]

Passengers and Ships to the Colonies

One needs to visualize the experience of traveling to the colonies in the 1600’s, the journey was filled with uncertainties, hardship, disease, and lack of privacy. Visualize a vessel of two hundred tons carrying a hundred passengers with a crew of about fifty officers and seamen, with their necessary freight and supplies including livestock. A typical voyage to the colonies or back to England took 8 to 12 weeks. Ships during this time period were not built to accommodate travelers. the ships were built for trade.

“Up to the seventeenth century, the tonnage of vessels crossing the Atlantic with passengers increased very little. Few reached beyond 500 tons. The type of vessel that typically was used for passenger trade were ships engaged in the wine trade to Mediterranean ports. These ships were constructed for that purpose and were known as ‘sweet’ ships. They were usually well caulked and always dry.” [29]

“Turning a wine ship into a passenger vessel with accommodations for one hundred and fifty or two hundred souls becomes a problem f several dimensions. The officer’s quarters on the poop deck and the sailor’s bunks in the forecastle were always limited in space, and the only space for passengers was the space between the towering stern structure and he forecastle or between decks. Below this hold, which was used for the cargo, the ordinance, and the stowing of longboats. In this part of the ship …cabins had been constructed, probably rough compartments of boards for women and children, while hammocks for the men were swung from every available point of vantage. “ [30]

Between the landing of the Mayflower and the American Revolution, a large number of individuals that emigrated to the colonies sailed from the ports of London, Liverpool, or Bristol and disembarked at New York, Boston, Annapolis, or Baltimore. [31] It has been estimated that

“For fifteen years space to the year 1643… the number of ships that transported passengers in this space of time as is supposed is 298. Men women and children passing over the wide ocean, as near as at present can be gathered, is also supposed to be 21,200 or thereabouts.

“the number of settlers of this territory before 1650 was less than twenty-five thousand, of whom about six thousand were original male progenitors of families, the rest being women, children, and servants”. [32]

Bristol was the first English maritime port which undertook voyages to the colonies. the Channel ports came next – Falmouth, Plymouth, Dartmouth and Southhampton. London did not become associated with this traffic until the Great Migration (1620-1640).

It has been noted that many passengers designated as being bound for Virginia in the early to mid 1600’s were actually bound for New England.

“(S)ome of the emigrants to America, who took passage in vessels “bound to Virgina”, found their way to New England, at an early period, and instances of names being found in or near Boston identical with names found in the lists of passengers, are cited. … (S)ome of the said vessels which are noted as “bound for Virginia” were in fact bound to New England, for that early period, New England was oftentimes spoken of as “North Virginia” and was by some supposed to be within bounds of Virginia proper… .” [33]

The following provides a novel visualization shipping patterns. In the video below, Ben Schmidt has taken data for Spanish, Dutch and English vessels between 1750 and 1850 and compressed them into one twelve month span to show seasonal patterns. Every journey has been visualized, with ships colour-coded by nation. [34]

Most of the regions in the North American British colonies were dominated by one particular port. Boston was the leading port in Massachusetts and throughout New England. New York City was the hub of New York’s trade. Philadelphia dominated the Delaware Valley’s seaborne commerce. Baltimore emerged by the time of the American Revolution as the chief port on the Chesapeake Bay which was 50 years after William’s baptism. Charleston was the focal point for ships and trade throughout the south of the British colonies. [35]

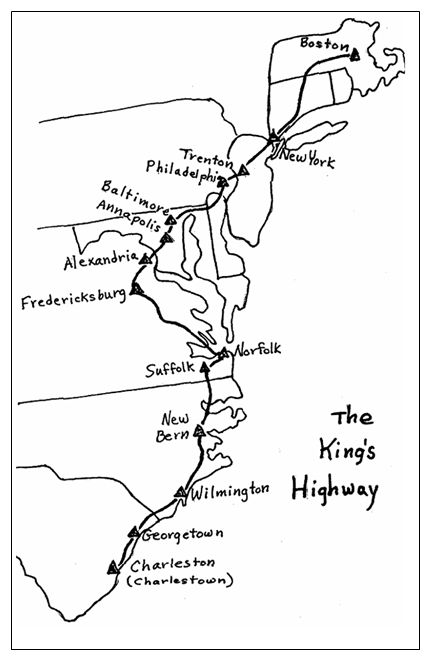

Coupled with these major ports and other minor ports, the Colonies had an emerging rudimentary network of trails that became roadways for travel north and south and into western portions of territory. However, land transportation posed a major problem in the British colonies. It was not until the mid 1700s that a continuous major road emerged that connected the colonies. This major road was called the King’s Highway 1636-1774 ( the Boston Post Road) from Boston to Charleston by 1750. Water travel was the preferred mode of transportation because roads were little more than trails. Most travelers preferred the packet boats servicing the southern coast rather than take the rugged four hundred mile overland trail. Initially, the colonists simply followed the old Indian trails or more commonly used the waterways. However, as people migrated into the interior, roads between the new settlements became necessary and were developed. [36]

Prior to 1820, many ships coming to America did not keep documentation of who was on board. Immigration increased appreciably after this time as well as documentation of ship manifests. However, documents and publications on immigrants traveling to the new world in the 1600’s and early 1700’s is sketchy. Many individuals traveled to their destination on cargo ships, usually only five, ten, maybe thirty passengers suffered through the trip together. Because of this, pinpointing documentation on the journey of a specific individual to pre-1820 America can be very challenging. [37]

My review of passenger lists of individuals traveling to the colonies in the 1600’s and early 1700’s, published genealogical accounts of families in colonial New England and New York, and other genealogical references have thus far resulted in a few tangible leads for the potential father or grandfather of William Griffith(s). I found 17 individuals with the name of Griffith or a variant of the surname that might be his father or grandfather. [38]

Griffin(th)(ths)(is)(es)(in)(ins)(ing) American Genealogies:

From a family geneological standpoint, this is where the story gets a bit ‘academic’. When one does a bit of family research and started to dig into deeper sources, the following references to a family’s past for anyone with a Griff- surname will usually encounter or reference the following individuals. One of the common ‘myths’ or unsubstantiated series of facts that has repeatedly been used to build American Griffin(th)(ths)(es)(ing)(s) family trees is tying the stories of Edward Griffin(en)(th) (born around 1602) and his brother John (born around 1608) from Walton, Pembrokeshire, South Wales to the American Colonies. Depending on historical references, Edward and brother John’s last name is spelled Griffen, Griffith or Griffin. Both brothers purportedly traveled in 1635 from Wales on the ships Abraham and Constance respectively, landing on Kent Island off the coast of Virginia. They have been mentioned in various family manuscripts and published genealogies. If you start to research any variant of the ‘Griff-‘ name in America, you will eventually be brought to these brothers.

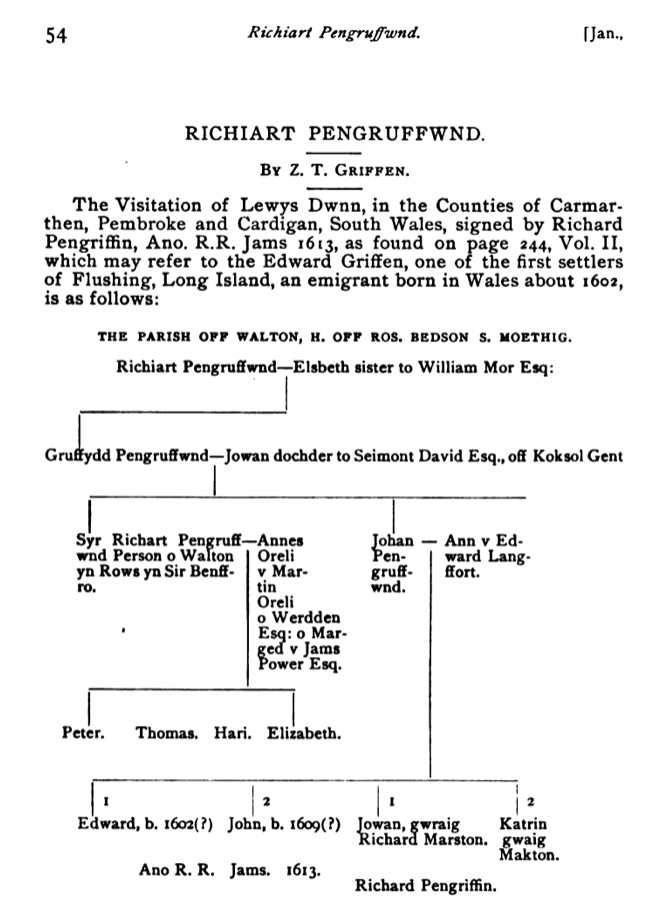

Many of the family histories also trace the purported family lineage backward from Edward Griffiin(en)(th) to Richard Pengruffwnd. This link is largely based on the research by Zeno Griffen. The common theme of this genealogical story is: Richard or Richiart’s descendancy purportedly is to a Gruffydd Pengruffwnd (Griffith Griffith) his son, who had a son John Griffith (who married Ann Langfort(d), who had Edward (b.1602) and John (b.1608). [39]

This common theme found in many of the Griffin(th)(ths)(is)(es) American Genealogies is reflected in the following quote from Paul Griffin. Paul Griffin provides an excellent starting point for research in an internet article of a bibliography of published and unpublished books, articles or manuscripts about the Griffin(th)(ths)(es)(ing)(s) family.

“Edward went from Wales to England and adopted the English spelling of his surname (originally Pengruffwnd, then Griffith). He was a constable in London when he killed a man in a tavern in the line of duty. He was pardoned by King James I on January 7, 1625 for justifiable manslaughter. He was said to have been a trusted servant and financial agent for Lady Wake (Wakefield?) in 1633. Edward and John sailed from England, on August 24, 1635 bound for Virginia, Edward aboard the ship “Abraham,” John aboard the “Constance”. It should be noted that those immigrants that left England at that time fortuitously escaped the Bubonic Plague that devastated the population some thirty years later. Edward first settled on Kent Island off the east shore of Chesapeake Bay near the mouth of the Susquehanna River. It is reported that he built oak staves for the hulls of ships. [The story handed down to me from my father was that the Griffins were ship builders in Wales.]

In June 1638, armed emissaries of Lord Baltimore attacked the Virginia settlers on Kent and Palmers Islands, killed three of its defenders, captured Edward Griffin and took him to Maryland. [There was a land feud at this time concerning the control of Virginia and Maryland. Lord Baltimore, siding with Maryland in trying to force the Virginia colonist off the Islands, ordered his brother to seize Kent and Palmer Islands and arrest everyone loyal to Captain William Claybourne, secretary of the Colony of Virginia. King Charles I mediated this squabble and censured Lord Baltimore, ordering him to cease his violence against the Virginians. This was not immediately carried out as Edward was held a prisoner for some time.]

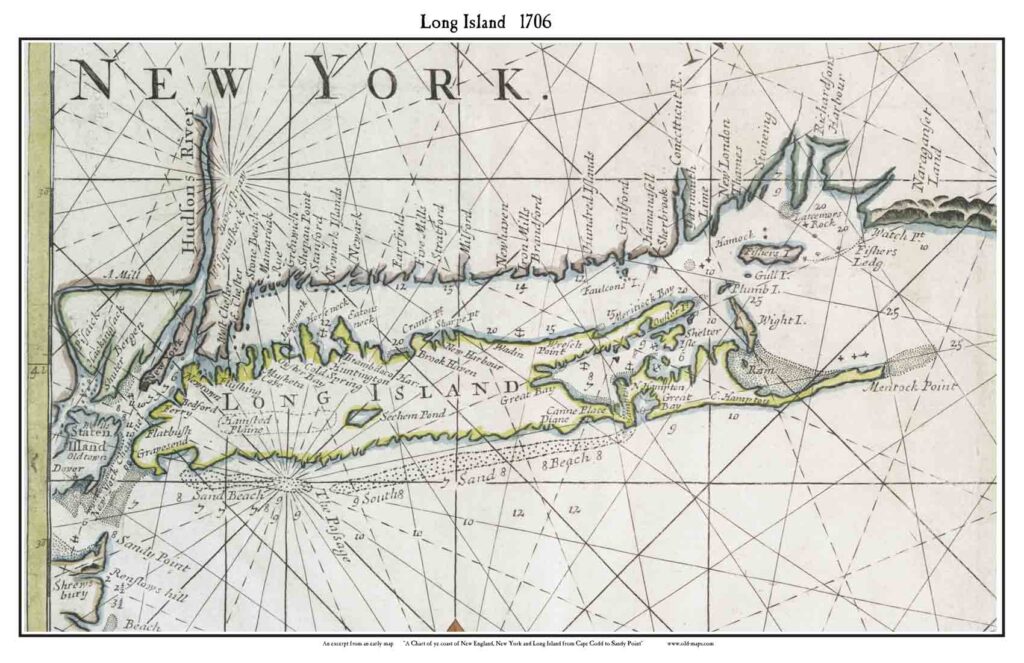

Edward escaped to the Dutch Colony of New Amsterdam, where he acquired land and finally located at Flushing L.I. about 1657 as one of its first settlers. He joined the Society of Friends (Quakers) in 1657 and protested the persecution of Quakers to Gov. Peter Stuyvesant. His descendants in the third generation became pioneers in Westchester and Dutchess Counties (especially Nine Partners Patent area) in New York State.” [40]

In a similar account [41] , Edward Griffin(en)(th) escaped from his captors in Maryland and came to New Amsterdam (present day New York city) 1640. He purportedly settled in Flushing in 1653 or possibly in Gravesend in 1656. He was one of the signers of the Flushing Remonstrance (signed as ‘Edward Griffine’ [42] ) against Governor Stuyvesant’s order forbidding the harboring of Quakers on December 27, 1657. In 1661 he was believed to be a resident of Oyster Bay. During that year, on Sept. 23rd, he acted as interpreter between the Indians and John Richbell in the purchase of land in Mamaroneck. Some time before 1675 he settled permanently in Flushing on Long Island, New York. He sailed for England December 14th, 1678 in the ship Blossom and later returned to Flushing. In 1686 he petitioned in behalf of his son John in relation to his share of the common lands of Flushing .

Edward Griffin(en)(th) purportedly married Mary (last name not known) in 1653 in Flushing, New York and had five children: Richard [43], John [44] , Susannah [45], Edward [46] and Deborah [47].

As Theresa Griffin has exhaustively and methodically documented in her research of the Griffin family, posted in 2009 [48], there were more than twenty Griffin family histories at the time of her critical analysis of Griffin family research that tie Pengruffwnd [Pengriffin] and his descendants with the Edward Griffith(in) who arrived in Virginia in 1635, and who ended his days as Edward Griffin(en)(th), in Flushing, New York. Almost all of these publications and family trees cite the work of Zeno T. Griffen or can be traced back to his research.

As Ms. Griffin indicates:

Zeno Griffen offered the above visitation pedigree of Richiart Pengruffwnd, recorded by Lewys Dwnn (pronounced Lewis Dunn) in his 1613 Heraldic Visitation of Wales, as evidence that this person was his ancestor, Edward Griffin, who died after 1698, in Flushing. To date, this statement has neither been authenticated nor challenged, though it is not surprising that Griffen’s assertions went unquestioned. It is not only notoriously difficult for Americans to search and translate Welsh records, but the variant spellings of Pengruffwnd (hereafter Pengriffin) and the Griffin and Griffith surname variations make the workload overwhelming. Consequently, American and Canadian descendants of Edward Griffin have used Dwnn’s pedigree as the starting point of their family histories for over 100 years. It appears, however, that in his zeal to find a family for his ancestor, Zeno made several incorrect assumptions, which resulted in the above-mentioned pedigree being published in the “New York Genealogical and Biographical Record” in 1906 and 1912. [49]

Ms. Griffin documents the following four general conclusions:

1. Neither Edward Griffin nor Sgt. John Griffin (another individual that is frequently cited in Griff- family research) Simsbury, Connecticut, [50] was related to the Pengruffwnd/Pengriffin family. The man who was born Edward Pengruffwnd (Griffith/Griffin (or Griffith Griffith)) was dead by 1622, and his brother, John Griffith, died in 1624.

2. Edward Griffin of Flushing, and Sgt. John Griffin of Simsbury, were not brothers and did not share a common blood relative within the past 10,000 years. There is solid DNA evidence that not only disproves their relationship, but clearly shows they are from different haplogroups.

3. Jasper Griffing of Southold (another individual that is frequently cited in Griff- family research [51] ) , did not share a common blood relative with Edward Griffin within the past 10,000 years. There is solid DNA evidence to prove this assertion.

4. The coat of arms attributed to the descendants of Edward Griffin, Sgt. John Griffin, and Jasper Griffing, was actually awarded to Griffin Appenreth, of Calais, who died in 1553, leaving no male heirs. No American or Canadian Griffins have rights to the following coat-of-arms, family crest, or motto:

- Gu[les] on a fesse betw[een] three lozenges or, each charged with a fleur-de-lis of the first, a demi-rose betw[een] two griffins, segreant of the field/ of the first

- Crest – A griffin segreant

- Motto – Semper paratus [52]

Through her methodical research Theresa Griffin cogently calls to question many of the assumptions, historical narratives, and family ties associated with Edward Griffin(en)(th) and concludes:

- We do not have an exact date of birth for Edward.

- We do not know the name of Edward’s parents.

- We do not know where Edward was born.

- We do not know when Edward married.

- We do not know the maiden name of Edward’s wife Mary, or if she was his only wife.

- We do not know the dates of birth of his children, or if he, had four children.

- We do not know Edward’s exact date of death.

- We do not have a will for Edward, although Van Peenen’s family history asserts his will was probated in November, 1691. I have spent hundreds of hours trying to locate one and have been unsuccessful. [53]

The influence and references to Zeno Griffien’s work is also found in genealogical studies of the Griffin(th)(ths)(ing)(is)(es) families outside of the United States. As a researcher states in a study of the Griffin family in Smithville, Ontario:

“I recently came across some material written in the early 1900s by a Zeno T. Griffen of Chicago. He seems to have spent many hours researching the origins of the American Griffin family. He quoted a pedigree in Dwnn’s Heraldic Visitations of Wales (1:244), and postulated that we are descended from this line. I have included this material in the hope that someone will be able to pursue this further and prove that we can, in fact, call these people our forebears.” [54]

While the story about Edward Griffin(en)(th) is exciting and provides the basis for a great script for a movie and despite the numerous citations of this story in various family histories, we are left more with conjecture than facts. I believe Edward Griffin is not related to our William Griffis(th).

William’s Ancestors and Family in the American Colonies

It is assumed that his father or grandfather emigrated to the British colonies. This would imply that his descendants conceivably emigrated between the 1640 to the late 1600’s or possibly the early 1700’s.

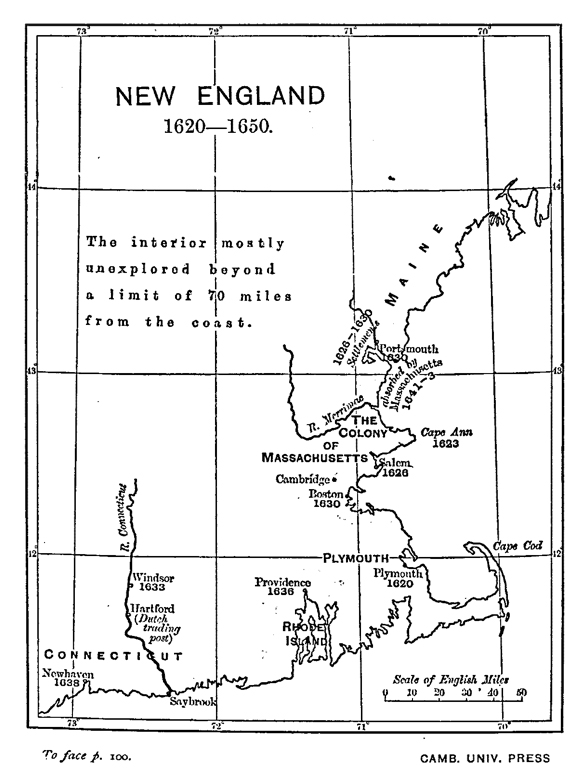

It is likely that William’s descendants traveled from London or Bristol and arrived in the northern colonies, perhaps to Boston, Salem, or other northern ports rather than the southern posts. It is conceivable that they then traveled from Massachusetts or Connecticut to Huntington, Long Island. However, as noted, William’s ancestors may have traveled on ships destined for Virginia based on ship manifests that actually landed in New England. They may also have traveled by land or intercostal boat from Maryland or Virginia up to New England or Long Island.

Huntington, Long Island was settled in 1646 and 1653 by an English company from Sandwich, Massachusetts. Prior to Huntington’s settlement it is noteworthy that “298 ships had brought over 22,200 emigrants to New England before the assembling of the Long Parliament (mid 1600’s); and the cost of the Plantations had been almost $1,000,000. In a little more than 10 years, 50 towns and villages had been planted; and between 30 and 40 churches built.” [55] Inland migration began from the Atlantic coast, following a wave of immigration into the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The first five ships carried about 900 colonists and the company’s charter. Some 16,000 settlers arrived during the period 1630–1642.

“The English towns on the Island, both on the Dutch and English territories, were settled by companies of individuals, the most of whom had first landed in some part of New England but had remained there only a short time, a little longer in some instances than was necessary to select a proper placer for a permanent residence, and to form themselves into associations adequate to the commencement of new settlements.” [56]

The greater part of Long Island was settled by colonists from Connecticut and Massachusetts. A confederation, The United Colonies of New England, was formed to manage and protect various settlements in 1643. Huntington came under their protection in 1660. [57]

Huntingon was close to New Amsterdam or what became New York City. From the very beginning, New Amsterdam hosted a diverse population, in sharp contrast to the homogeneous English settlements going up in New England. In addition to the Dutch, the growing city included Scots, English, Germans, Scandinavians, French Huguenots, Muslims, Jews, Native Americans, and African slaves and freemen). As early as 1643, a Jesuit missionary reported that New Amsterdam’s few hundred residents spoke 18 different languages between them. [58]

“The people of Huntington were for the most part farmers, but there were some who followed the sea ; and although it is not probable that the profits of the cod fisheries and the whale fisheries came here, quite likely the traffic in West Indian goods, in rum and slaves, occasionally enriched some of Mr. Prime’s parishioners.” [59]

“It is not clear when or where the first settlement (of Huntington) was effected. The earliest Indian deed, between the Sagamore Raseokan, of the Matincock tribe, on the one hand, and Richard Houlbrock, Robert Williams and Daniel Whitehead on the other, when certain lands in the township about six miles square were sold by the Sycamore to the pioneers for ‘6 coats, 6 kettles, 6 sachets, 6 howes, 6 shirts, 10 knives, 6 fathoms of wampum, 30 uses, 30 needles’, is dated April 2, 1653, and it was not until six years later that a town meeting was called… .” [60]

Most of the early settlers of Huntington were English. They arrived in Huntington by way of Massachusetts and Connecticut. The emigration from New England (Connecticut and Massachusetts) to Long Island in the mid 1600’s was largely attributed to religious motives versus commercial motives. [61] The first settlement of Huntington was commenced by eleven families, immediately followed by others. The original settlers in the English towns were principally English Independents or Presbyterians. Many were well educated and left reputable connections in England. The early records and public documents of several towns reflect that the leading men had knowledge of English law and were ‘acquainted with public business’.

The first and oldest English land grant company came across the Sound from the vicinity of New Haven and Branford, Connecticut under the guidance of the Reverend William Leverich. They landed at Huntington harbor and located in the valley where the eastern part of Huntington village exists. There was a second emigration to the area, an off shoot of the initial group, led by Reverend Richard Denton. This group was from Werthersfield, Massachusetts and for a time from Stamford, Connecticut. A third wave of emigrants to Huntington came from the Salem, Massachusetts area after stopping in Southold and for a a short period of time in Southhampton. [62]

“In the first years of the settlement the pioneers built their rudely constructed dwellings around and near the “town spot,” where they had a fort and “watch-houses,” and where the “train bands” were drilled. Their animals were daily- driven out and herded under guard, some in the “east field,” now Old Fields, and some in the “west field,” now West Neck, and at night the cattle were driven back and corralled near the watch-house. Gradually, however, the more adventurous pushed out in all directions, and made them- selves homes where they found the richest soil and most attractive surroundings, and at their meetings grants of “home lots” were made.” [63]

The Puritans (who sought to “purify” the Church of England from within) didn’t arrive in the American Colonies until 1630. They were Calvinists, and preferred a Reformed style of service and polity ― rule by elders instead of bishops. Those tenets traveled with a second wave of Puritan emigrants who set sail from Lynn in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in March 1640 to Long Island, in present day New York. There they founded what is widely considered the oldest Presbyterian congregation in America: First Presbyterian Church, Southampton, New York. The next seven oldest Presbyterian churches in America were also established by Puritans on Long Island: Southold, 1640; Hempstead, 1643; East Hampton, 1648; Newtown, 1652; Huntington, 1658; Setauket, 1660; and Jamaica, 1662.

Purportedly the settlers from Lynn were searching for available land to farm. They landed at Cows Neck near present-day Manhasset. They were arrested and imprisoned by Dutch officials for allegedly tearing a symbol of Dutch sovereignty from a tree. they were released on the condition of leaving the island for good. However, they sailed back toward Massachusetts Bay, eventually making their way to Southampton.

In addition the thee aforementioned emigrant waves to Long Island, it is also a possibility that William’s descendants were part of a group from New Haven. Around this time settlers from near New Haven, in present day Connecticut, founded another settlement on Long Island called Southold. Several secondary sources state that Rev. John Youngs, previously of England, formally organized a church there in October 1640. [64]

While the Dutch settled what is currently called Manhattan and western Long Island and the English controlled New England, the first settlers in Huntington were largely outside the jurisdiction of any European authority. Several towns in the English territory of Long Island were not under direct control of any colonial government. Being too remote from England or the land patent companies, the powers of governance relied on the inhabitants of each town. Each town in their initial stages of settlement were a pure form of democracy. The people in each town exercised sovereign powers through town committees.

Between the mid to late 1600’s, the political climate surrounding and impacting the newly established English towns was in continual flux. During the war between the Dutch and English ( 1672 to 1674), the Dutch attempted to recover their authority on Long Island. They arrived at the end of July in 1673 and with a quick submission by the English in New York established a new Dutch governorship. They issued a series of proclamations to several of the English Long Island towns requiring them to send two deputies to New York establish allegiance to the Dutch rule. The towns that were originally settled by the Dutch submitted to the resolutions. In October, of 1673, the Dutch sent emissaries to other towns to seek similar agreements. The settlers of Huntington offered to sign the agreement tone faithful to the Dutch government but refused to take any oath that would bind them to take up arms against the British crown.

The governor of Connecticut eventually raised objections of the Dutch incursion. The Dutch governor escalated actions by undertaking efforts to take the Long Island towns by force. Connecticut in conjunction with confederates, declared war against the Dutch and made preparations for war in the spring of 1674. The Dutch governor backed down in March 1674 and ordered all vessels back to New York. Peace was established between England and the Netherlands February 1674. News of the end of the war did not arrive to the colonies until several months later. No one from England was sent to receive the surrender of the New York and the impacted towns until the fall of 1674. [65]

During this time in England, a king was beheaded, a civil war was fought, another king was restored to the throne and the Glorious Revolution saw the invitation to a Dutch regent to take the English throne. Each change of leadership led to a required reaffirmation of the settlers’ claim to land. In 1688, following the ascension of James II to the English throne, his governor, Thomas Dongan, issued a patent that confirmed property rights of the earlier land patent. In addition, it mandated the creation of “Trustees” to manage and distribute town-owned land. The Trustees, like other town officials, were chosen at a local Town Meeting.

Most of the early English settlements on Long Island established common local governance measures or local rules. The first class of local rules were related to the division of their lands; the enclosure of common fields for cultivation and pasture; regulations respecting fences, highways and watering places; the management of livestock and horses; and the management of common grounds and the destruction of wild animals. The second class of rules were associated with measures related to public defense; the collection of taxes for the education of their youth; the preservation of morals and the support of religious freedom as well as the suppression and punishment of crimes and offenses.

One of the first measures adopted in every town was the requirement of every man to have arms and ammunition and to be ready to assemble at an appointed time and place when warned under a penalty of neglect. [66]

The public expenses for local town regulations and management were defrayed by a tax, the amount of which was fixed by a vote of the people in a general town meeting. The salaries of the first ministers in most of the towns were raised by taxes by an assessment on all inhabitants according to the land they had occupied. [67]

The seventeenth century in colonial America was tumultuous in terms of local events and local controls as well as the influence of political shifts in England. In 1664, the English gained control of the Dutch colony of New Netherland. The Duke of York became proprietor of the area and the colony was renamed New York. The Duke’s representative, Governor Richard Nicholls, asserted control over all of Long Island and summoned representatives of each town on Long Island to meet in Hempstead early in 1665. The representatives were required to bring with them evidence of title to their land and to receive a patent from the crown affirming that title.

Huntington consisted mostly of farms. The community also included a school, a church, flour mills, saw mills, brickyards, tanneries, a town dock and a fort.

“Among the records of Huntington for 1657, there is a draught of a contract with a school master for three years, at a salary of 25 pounds for the first year, 35 pounds for the second year and 40 pounds for the third year”. [68]

Shipping was also an important part of the economy with vessels traveling to and from other ports along the Sound and also as far as the West Indies.

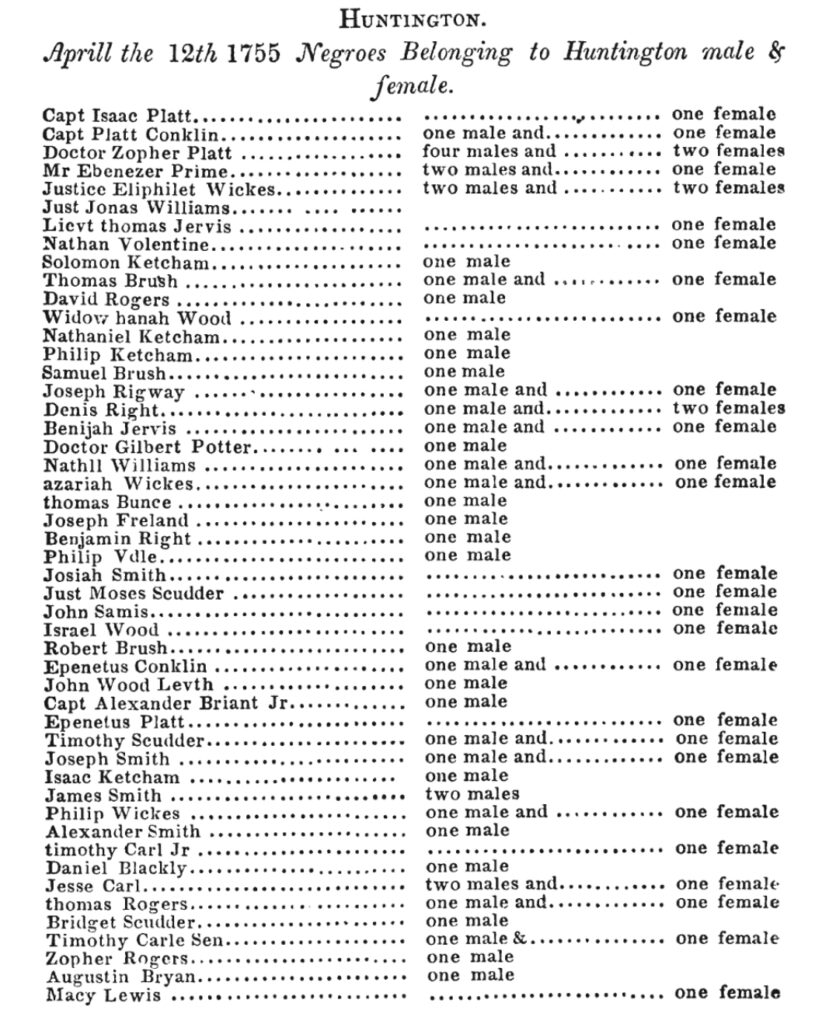

“Slavery existed in Huntington until the beginning of the nineteenth century. Farmers relied on slave labor for help in the fields and but rarely did a person own more than a few slaves. For example, according to a 1755 census, there were 81 slaves belonging to 35 families in Huntington. Unlike the South, the economy was not heavily dependent on slave labor. The New York State Legislature passed an act in 1799 providing for the gradual abolition of slavery.” [69]

Based on the absence of records that explicitly identify a Griffis household with slaves, it is unlikely that the Griffis Family had slaves. [70]

In 1660 residents in Huntington voted to place the town under the jurisdiction of Connecticut to gain some protection from the Dutch.

The Griffis Family and the Revolutionary War

Daniel Griffis was born in 1777. The Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Brooklyn Heights, was a major military action of the American Revolutionary War fought on Tuesday, August 27, 1776, at the western edge of Long Island in present-day Brooklyn, New York. The British defeated the Americans and gained access to the strategically important port of New York. The Battle of Brooklyn was the first major battle to take place after the colonies declared its independence on July 4, 1776. In terms of troop deployment and combat, it was the largest battle of the war. [71]

Resentment of English authority was strong in Huntington. As reflected in town meeting minutes and historical accounts, alarmed by the events in Boston and hoping to re-assert their rights as British citizens, the citizens of Huntington adopted a “Declaration of Rights” in June 1774, affirming “that every freeman’s property is absolutely his own” and that taxation without representation is a violation of the rights of British subjects. The Declaration of Rights also called for the colonies to unite under a general action to refuse to do business with Great Britain until the crisis in Boston was resolved.

The year of independence proved eventful—and tragic—for Huntington. The year started with the shipment of gunpowder. On July 22, news of the signing of the Declaration of Independence reached Huntington where it was met with great excitement. An effigy of the king was created using materials ripped from the red flag that included the British union and the words “GEORGE III” on one side and “LIBERTY” on the other. The union and the king’s name were removed, leaving a red flag with “LIBERTY” in white letters. The effigy was hung and blown up. Thirteenth patriotic toasts were made to celebrate the occasion.

The following month, the Liberty Flag, as it came to be known, was carried to the Battle of Long Island. Unfortunately, the American forces suffered a humiliating defeat. George Washington and his army had to escape to Manhattan at night under cover of fog. [72]

The British controlled New York and the entire island between 1776 to 1783. Daniel Griffis was about 5 months old when this battle was fought. When the British finally left, he was 6 years old. His father William was 41 years old and his mother, Abiah, was 48, when he was born. At the start of the occupation, Daniel’s three oldest siblings brothers, William Gates Griffis and James Griffis, were respectively 21 and 19 years old and his oldest sister Anna was 16. Two other brothers, William and Stephen, were both 14 years old. James and William fought for the colonists in the Revolutionary War. It is believed his older brother, William Gates Griffis, also fought for the colonists. [73]

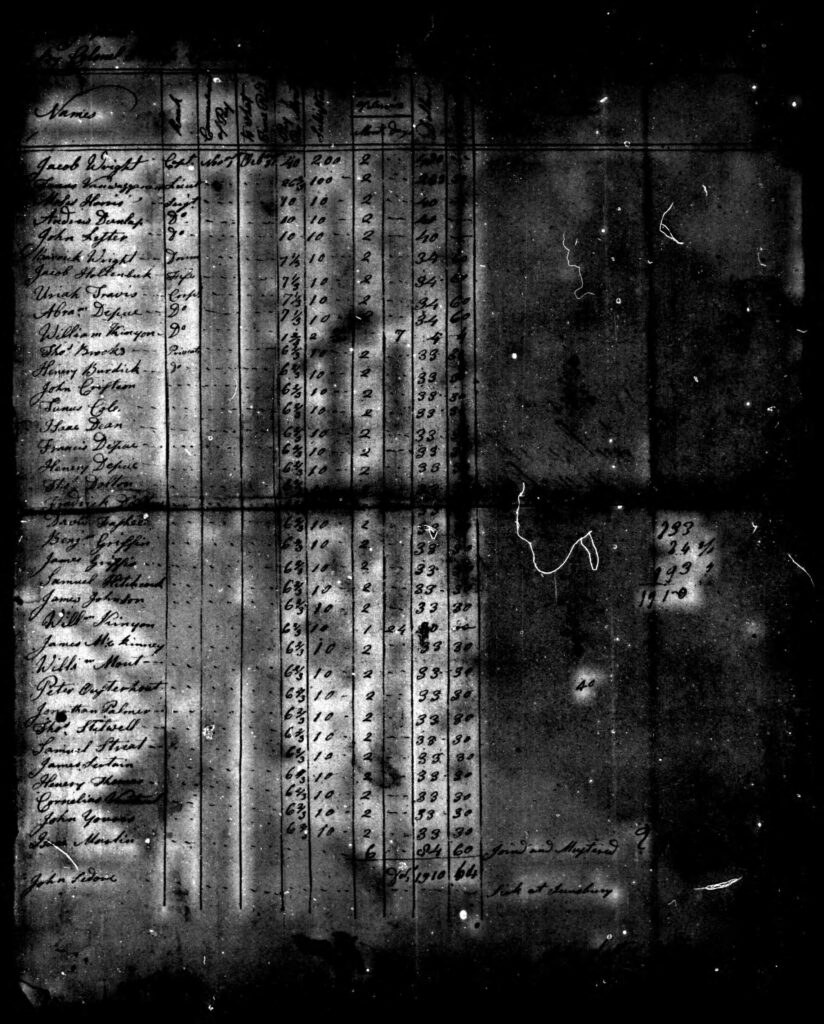

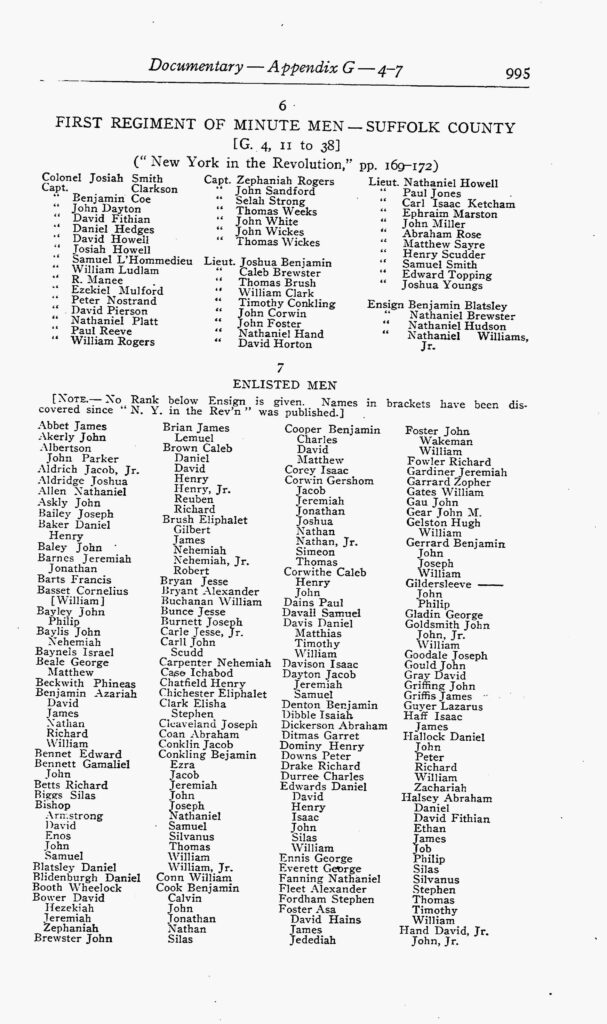

There is little in terms of documentation on the Griffis family in Huntington, Long Island during the war. However, it appears that William and Abiah and their family stayed in Huntington through the duration of the war. It is noted that James Griffis, William’s son, served in Colonel Smith’s Regiment of Minute Men and was engaged in the Battle of Brooklyn. He returned Huntington after the Minute Men were disbanded after the colonists’ defeat in Brooklyn.

Many of the colonists who had served as officers in their local militia or as members of a town and county committee, fled to American controlled areas (New Jersey, Upper New York State, Connecticut) for safety. Those who remained at home were harassed and their personal and real property were confiscated, used or plundered. Those who stayed on the island were subject to the orders of British officers.

“The sudden presence of British troops alarmed citizens and interrupted their daily lives. Soldiers relied on Long Islanders for provisions and housing for an indefinite amount of time. In reality, few were truly safe, and violence of all kinds was commonplace. People from all walks of life were robbed, abused, kidnapped, and sometimes murdered by marauders who took advantage of wartime situations. Yet, despite all of this doom and gloom, some Long Islanders managed to persist in their daily life activities under British occupation.” [74]

The British troops forced Huntington residents to take oaths of allegiance to the Crown. If a man refused to take the oath, he and his family faced the prospects of loosing their property. Many of the families that stayed through the occupation signed the oaths to avoid persecution while tacitly supporting the revolution. James Griffis, who fought for the Suffolk County Minutemen, returned home and during the occupation and signed the oath in 1788. [75]

The British established a headquarters in Huntington and used Long Island as a supply depot for the occupying forces in Manhattan. Crops and livestock were taken, horses and oxen were commandeered, and residents were forced to provide food, housing and labor.

“The people of Long Island not only suffered from the abuse of the British during the war but after the war they also incurred the prejudices of the state legislature. Two separate acts in 1783 and 1784, they were prohibited from requesting compensation for the damage and loses they incurred while under British occupation. In addition, a tax of 37,000 pounds was assigned to Long Island, as compensation to the other parts of the state for not having been in a condition to take a more active role in the war against the enemy. “ [76]

In a Huntington town property assessment report at the end of the war, it is reported that the value of property held by William Griffis was 16 pounds. It reflected a piece of property that was rather modest in comparison to other properties in Huntington. The lowest value was 8 pound and 10 shillings for the property held by “Widow Sarah Platt” and the highest property owned by Doctor Zophar Platt was valued at 561 pounds. [77]

Griffith(s) Family Trees and Manuscripts of the Griffis Huntington Family

excerpted from a New England Map For larger view.

There are a number of web based family trees, unpublished personal manuscripts and published sources that directly reference William Griffis(th)(in)(ths) of Huntington, New York. I did not come upon this discovery of these records until fifteen years after my start at periodically looking into the Griffis lineage. The diagram depicted in the Synopsis at the beginning of this story provides a quick outline of the 12 children of William Griffis.

The information on William’s 12 children is based on documentation found in three Griffis Family manuscripts, a number of family tree websites and the church records of the Rev. Ebenezer Prime who was the Pastor of the First Church of Huntington. [78]

Table One: Major Sources of Griffis Family Tree Documentation

| Family Tree | Source | Description |

| Descendants William Griffith | Long Island genealogy | Basic information on William and Abiah, their 12 children, and descendants of James, (Nancy) Anna, Epenetus |

| Gates | Long Island genealogy | Basic information on William and Abiah, their 12 children, and descendants of James, (Nancy) Anna, Epenetus |

| Bryant | Long Island genealogy | Basic information on William and Abiah, their 12 children, and descendants of James, (Nancy) Anna, Epenetus. A PDF copy of the family listing of these branches of the family can be found here. |

| William Griffith [80] | Griffi(th)(n)(s)(ng) Surname DNA Project | Pedigrees posted to this site are the submissions of the individual DNA participants. G49 DNA kit 125476 |

| William Griffis | Rootsweb Individual Family Tree | Lists William as Griffis and all descendants as Griffith. Only detailed descendants of fourth son William Griffis(th). PDF copy available in the event internet source is discontinued. Another detailed list of descendants of William Griffis who emigrated to Ontario, Canada after the Revolutionary War |

| Griffith | Peets – Welsh Manuscript | Lists William and Abiah and 12 children, and descendants of second oldest son James. PDF copy of the manuscript can be found here. |

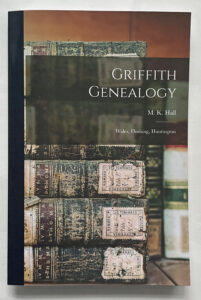

| Griffith | M. K. Hall manuscript | Lists William and Abiah and 12 children, limited information on descendants of second son James. A PDF copy of the book can be found here. |

| Griffith | Jones – Welch Manuscript | The Jones-Welch manuscript provides a wealth of information on the family tree of the fourth child of William Griffis: William Griffis who was born in 1763. PDF copy of the manuscript can be found here. |

| James Griffith | ancestry.com | Information on James Griffis(th) descendants |

| William Griffis | Manuscript | Records of the First Church in Huntington, Long Island, 1723 – 1779, Being the Records Kept by the Rev. Ebenezer Prime the Pastor During Those Years, (from old catalog) (Huntington, NY: Moses L Scudder, 1899). Provides Baptism and marriage dates for William and most of his children. |

Family Tree Websites

There are numerous web based family trees and genealogies that reference William Griffis(th)(in), baptized in 1736. These family trees can be found at longislandsurnames.com, ancestry.com , geni.com, familysearch.com , myheritage.com , and wikitree.com.

Four notable limitations for all of these web based trees are:

- There are a few that identify proposed ancestors of William but all of those family trees lack sound, corroborating facts that support the linkages to his purported parents or grandparents and other ancestors.

- Many of these internet based family trees contain inconsistent or contradictory facts.

- All of the family trees list family members with the same uniform surname with no substantiation of facts regarding discrepancies in spelling or that a given family member used a specific spelling of Griffis, Griffith, Griffies, or Griffes.

- None of the family trees provide complete lines of descendants for William’s children that had families.

There are a few family trees located on ancestry.com that provide excellent documentation on some of the family branches or descendants of William Griffis. I discovered these family trees after I came upon two unpublished manuscripts on the family in 2015. I have relied upon those sites and the manuscripts to document other branches in the Griffis(th)(es) family of Huntington, N.Y.

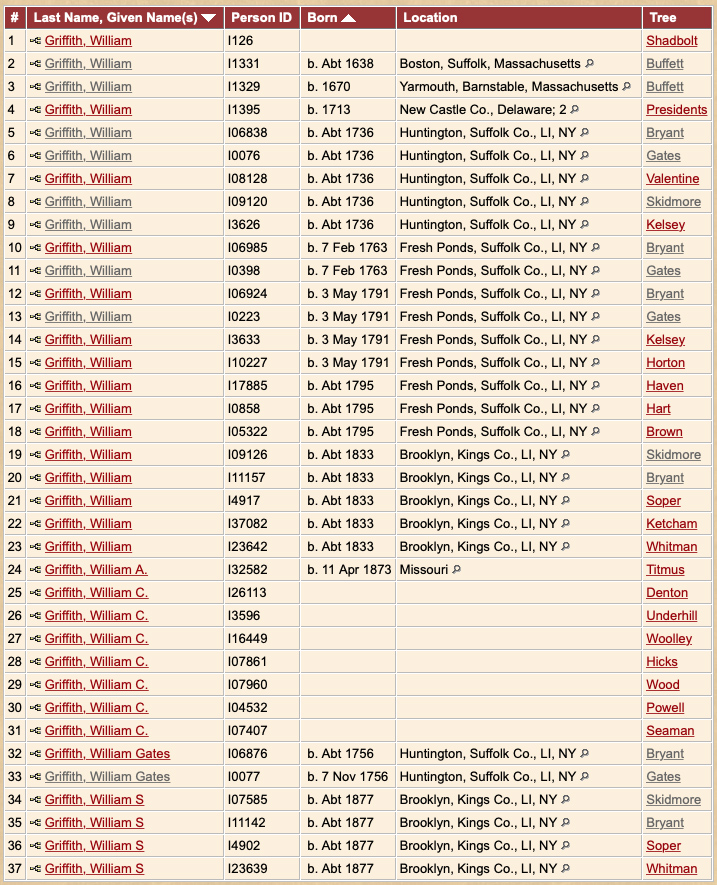

One major source of information was found at a website long island genealogy. A link on the website lists family trees that managed by specific individuals who link a William Griffith (see chart below). As illustrated in the list, there are a number of family trees that reference William an his ancestors. It is notable that there are also family trees for the Gates branch of the family. Most of the family trees listed and maintained on this website uniformly spell the surname as Griffith and appear to contain the same information.

In correspondence with the Research Team that manages the Long Island Genealogy website, I received a document that referenced the church records of the Records of the First Church in Huntington, Long Island 1723-1779. [79] The document lists a partial family tree of the descendants of William Griffis(th). The list has detailed information on the descendants of James, Anna and Epenetus. The document appears to list individuals that were found in a Gates family trees on the Long Island website.

There are three genealogical manuscripts that explicitly mention William Griffi(th)(in)(s) of Huntington, New York. Two of the manuscripts are unpublished. The third has been published by third party companies and may have been used to document facts in the other two manuscripts. Similar to the other manuscripts and published works previously mentioned, they exhibit similar patterns of linking individuals without genealogical proof prior to the early 1700’s. While they may have certain limitations or gaps in facts, they are useful documents that provide insight into our Griffis family from Huntington, New York. Not only do they document the surname back to the early 1700’s, they document various branches of the family tree not only in New York state but in other parts of the country as well as Canada. Ironically, they have no information on our specific branch of the Griffis(th)(es) family (Daniel Griffis).

I was at a certain point in my research around 2015 that I was hitting dead ends in my attempt to document the Griffis family tree beyond the early 1800’s. I was under the mistaken assumption that my research needed to focus on the name ‘Griffis’.

Griffis(th) Family of Huntington, Long Island Manuscripts

Two notable unpublished manuscripts [81] that provided added insight and genealogical information on specific branches of the Griffith(s) family from Huntington, New York are listed below. They were brought to my attention by another avid genealogist who actually was remotely related through marriage, Susan Montagne. [82] I came upon this discovery via the internet. Ms. Montagne was primarily interested in William Griffis, the fourth child of William Griffith(s), who was born in 1763 and eventually emigrated from New York to Canada. I saw her name referenced in a well documented footnote on information pertaining to William Griffis (born 1763) that was part of a family tree developed by Cheryl (Kemp) Taber on RootsWeb. [83] Further research resulted in finding an ancestry.com Griffis family tree developed and maintained by Susan Montagne. I also found a website that identified a William Griffith of Huntington and his family. [84]

Two Influential Griffis Family, Huntington, NY Manuscripts

“Peets – Welch Manuscript“

“Jones – Welch Manuscript“

Mildred Griffith Peets and Capitola Griffis Welch , Griffith Family History in Wales 1485–1635 in America from 1635 Giving Descendants of James Griffis (Griffith) b. 1758 in Huntington, Long Island, New York, compiled by Capitola Griffis Welch, Unpublished manuscript, 1972 PDF copy of the manuscript can be found here.