Once a decision is made on the usefulness of the evidence and what genealogical facts to use, the next step is creating a story. The idea of a story is often the result of coming up with a novel angle to view genealogical facts. It could be an object that was once an ancestor’s possession, a photograph, a family, a major event experienced by a family or family member, the original set of ideas are endless.

However, once an imaginative spark leads to the premise of a story, the hard work begins. An idea of a story requires further research to put all of those facts and evidence into a wider historical, cultural, and social context. Reading a list of facts is literally accurate but, for me, lifeless. We need meat on the bones of our story to help spark one’s imagination.

Writing family history is challenging because we need accuracy, context, and imagination.

“A family history is not complete until it considers the time and place in which each individual lived. Our ancestors were affected by the events around them, just as people are now; their relationship to their environment is an important part of the family’s story. Providing historical context, however, requires thoughtful choices. In well-written family histories, the historical setting for each ancestor will treat events and social conditions relevant to that person’s life, not just major happenings of the era.” [1]

Genealogical and historical sources, combined with historical analyses of the larger cultural, social, economic, demographic, and material forces at the time of a given story can provide context and historical meaning to interpret those few facts we may have discovered about our family.

The methodological approaches associated with historians and genealogists are overlapping and complimentary.

“For historians, chronology is everything. In contrast, genealogists start in the present and then work backwards incrementally through time. Their currency is demographic information—names, birth and death dates, and marriages—and the historical narrative sometimes seems secondary to identifying particular individuals. …

“Genealogical excursions back in time, combined with scholarly analysis of the time period in question, can produce powerful stories that reveal a great deal not only about particular families, but about the great drama of human history.” [2]

The ultimate goal of a genealogical story would be the ability to tell the unique story of a family or family member from direct, original sources. Unfortunately, we normally do not have all the facts to reconstruct their lives. We have to ‘fill in the blanks’ between available facts that we have uncovered. The bulk of reconstructing a story is based on viewing lives within the contexts of larger cultural, social and larger scale influences on their lives.

While our ancestors had free will to choose unique and innovative solutions to the things they faced in life, it is highly probable that many of their decisions were influenced by major events of the day, various social groups in which they lived their lives, cultural beliefs and practices associated with various social groups that were important to them. Broader historical, social and environmental forces also set the stage for what was their sharfed world of values and action..

Most of the facts we may have found in our family research are based on a person or family. These facts might be embodied in letters, family objects, government documents such as marriage or census documents, wills, church documents, and other tangible objects. Most of our narrative of family history is focused at what I call the individual level or micro level of analysis.

My View of Influences in Family History

To provide a wider historical context to interpret an individual or family experience, it can be fruitful to examine an individual’s or family’s place within different levels of social structures or networks to understand what was going on at the time they lived. As reflected in table one, we can expand our view of our families in history in the context of wider spheres of social structures or networks that they were embedded.

Contextual factors broadly encapsulate the multitude of influential conditions within which individuals and communities exist and function. They can help explain or provide descriptive illustrations of what an ancestor’s life experiences were in a particular time period. [3]

Table One: Social Structural Levels or Networks of Influence

| Social Structural Level | Examples of Social Structural Influences |

|---|---|

| Individual | Family Member / Couple Nuclear Family |

| Micro Level | Extended Family / Local Neighborhood Local Social Groups (Church, Local Community) Local Occupational Work Groups |

| Intermediate Level | Ethnic Networks Economic Strata / Class City-Wide area / Local Regional Areas |

| Macro Level | State and National Level European Country Geographical Region |

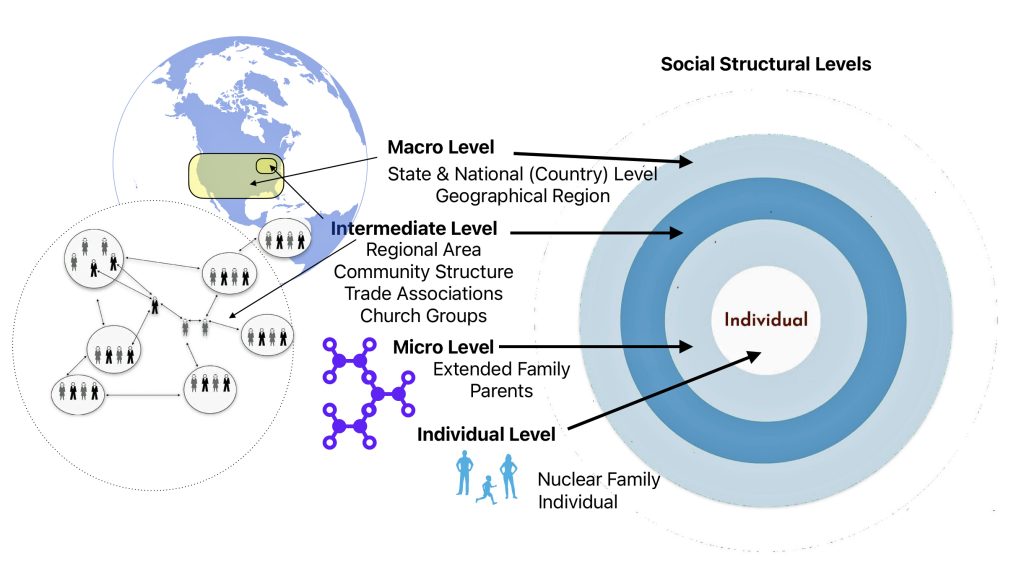

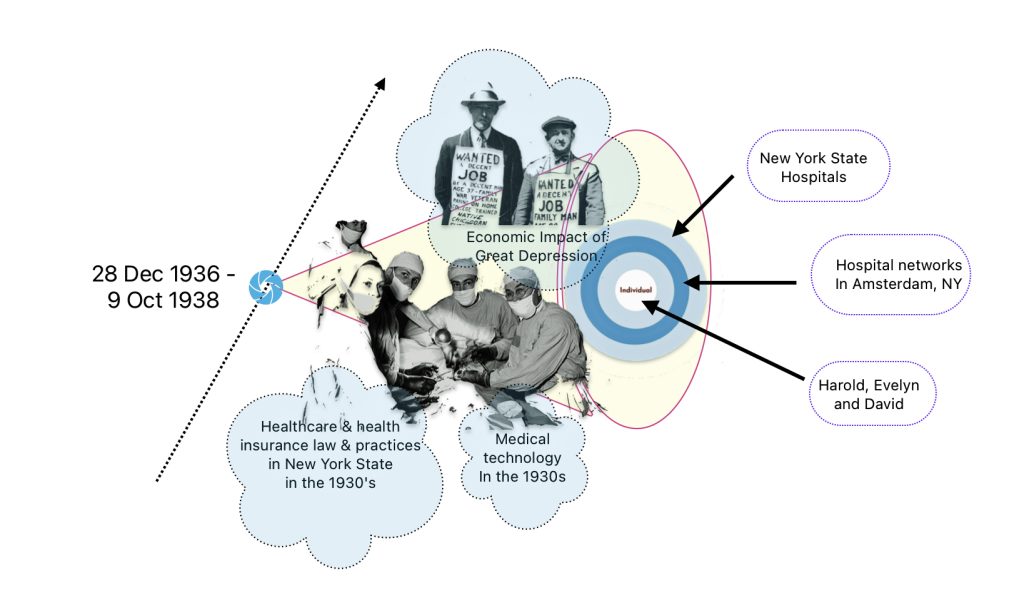

The social structural levels of analysis are also depicted in illustration one. We and our ancestors are always living within the influences of different social networks, groups and geographical areas. Depending on what we are researching, certain groups or social structural levels play an important or prominent part in providing an explanation of what we are looking at and what is happening at a particular point in time.

Illustration One: Social Structural Influences

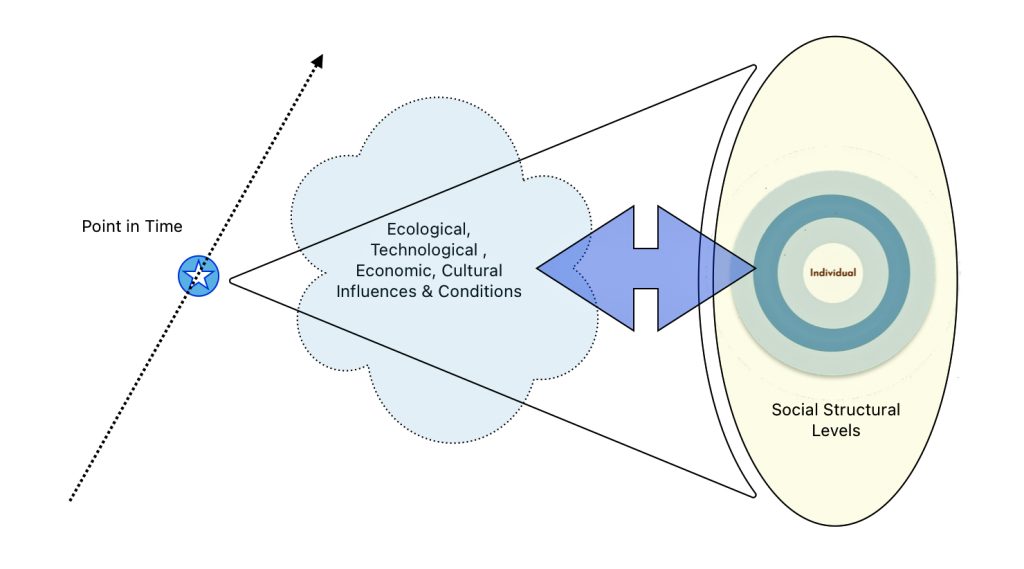

As depicted in illustration two, in addition to the various social structural levels that may influence our development of a story about a family member of family, there are ecological, technological, economic, cultural influences that may add historical context to the story. These influences may affect specific or all social structural levels.

The theoretical analysis and empirical studies of the correlation and causality between the interrelations of social structural, cultural, environmental, technical and other influences on human behavior are exhaustive and documented in the fields of anthropology, sociology and history. I am sidestepping these important and fundamental issues. [4]

I am merely attempting to write engaging stories about our ancestors. Therefore, simply recognizing the impact of and interplay between social, cultural, technological influences is sufficient to pinpoint potential sources of facts and evidence for weaving stories from our genealogical evidence. [5]

Illustration Two: Social Structural Levels and Other Influences

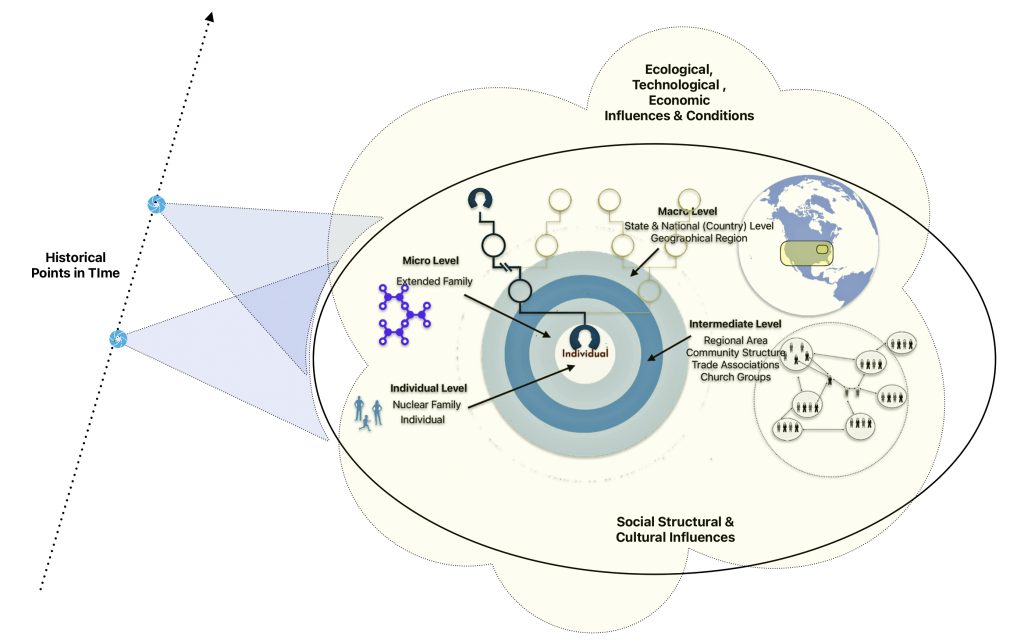

If we add time, the story will incorporate changes in any of these factors and their relationships, reflected in illustration three. I might, for example, be concerned with a particular event that impacts the nuclear and extended family and community and in a later time period I might be providing details on an event that impacts the extended family or the macro level.

Illustration Three: Time and Historical Context of Structure, Culture, and Other Factors

A few practical examples of stories that utilize this model are provided.

The Fliegel Family Coming to America

My stories of the Fliegel family members migrating to the United States can be used to explain this research perspective or approach. I had fragments of information about their emigration from Germany. I was able to locate ship manifest documents of their travel from Le Havre, France to New York City. I also had Federal and state census documents of the family once they settled in the United States.

All of these pieces of information provided starting points for further research to provide added historical context to their life stories.

See the Following Stories

- A German Influence July 11, 2023

- Our German Descendants from Baden: A Tradition of Migration (Part Two) May 16, 2024

- German Descendants from Baden: Following a Long Tradition of Migration (Part One) May 9, 2024

- John Wolfgang Sperber – Part One: The First of the Sperbers in America January 30, 2024

- The Fliegel Family: Their Journey to America October 10, 2023

- The Sperber & Fliegel Families in America: Catherine Fliegel the First to Arrive September 26, 2023

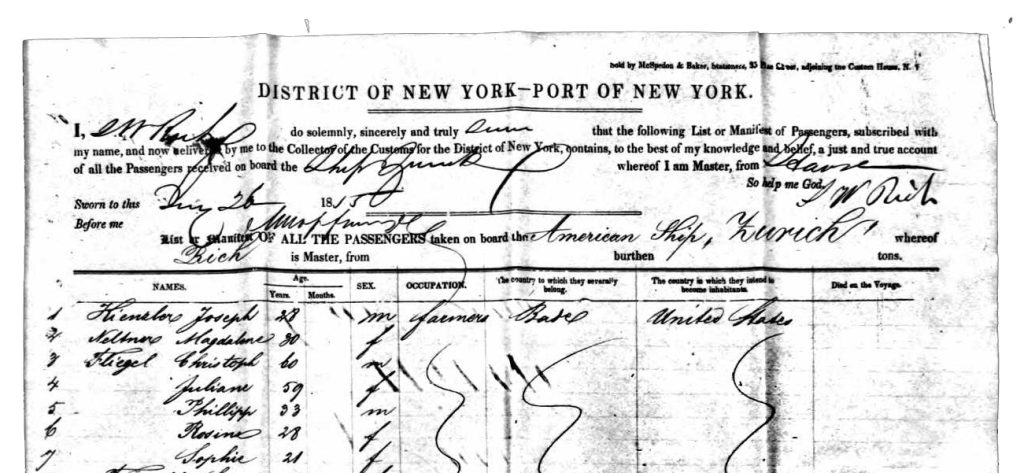

The manifest lists provided a wealth of information: I knew who came over, when they arrived, what ship they were on, where they purportedly were from in Germany, what ports they traveled from and where they landed in America, and what were their stated occupations. I also knew the name of ship captain.

Image of Top Page of Ship Manifest List

The ship manifest list provided leads for further research on the shipping company as well as the packet ship. It also provided a starting point to research and understand the development of global trade between Europe and America (i.e. New York City and Le Havre) in the mid 1800s and how it facilitated the immigration Germans to the United States. It also raised a number of questions concerning why Le Havre, France was used rather than some of the German ports, as a point of departure. I also started to consider questions regarding the nature and the conditions and constraints of the journey from their home in the Grand Duchy of Baden to Le Havre .

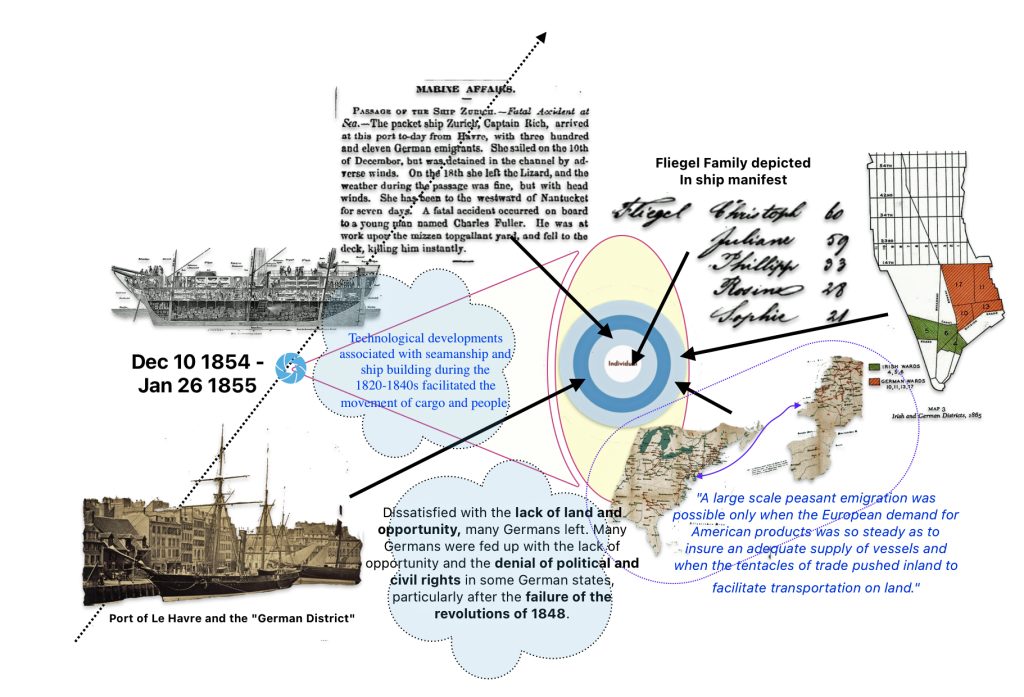

The date of their immigration provided a point in time to understand what was going on in Germany. I shifted my focus in the story to place their life experiences within the context of the various waves of German immigrants coming to America. I considered the reasons why they made this major change to their lives based on various intermediate and macro level factors such as the local economy where they lived in the grand Duchy of Baden. I looked at the economic and political push and pull factors at the macro levels as well as the technological factors that facilitated immigration transportation to understand other factors that influenced their decisions for travel from certain ports of departure.

The following two tables provide examples of social structural and other influences on the Fliegel family’s immigration experience to America.

Table Two: Social Structural Influences on the Fliegel’s Journey to America

| Social Structural Level | Examples of Social Structural Influences |

|---|---|

| Individual/ Family | Influence of Chain Migration of Family members: Catherine arrived first and remaining family arrived seven years later. This was an example of a much larger social practice. |

| Micro / Community | Learning from the past community and regional influences on immigration to America provided an understanding of why they chose the New York state area as a destination point. |

| The community influences in America:: Many of the German immigrants who landed in New York City, settled down to live their lives on the Lower East Side of New York City in Little Germany.. Other German immigrants used this geographical ethnic enclave as a launching to find a spouse, establish networks and gain information and resources to make plans to travel further west into the United States. | |

| Intermediate | Tradition of migratory patterns of population from Baden: within the constraints established by the labor market, immigrants frequently chose to live among kin, fellow townsmen, fellow provincials, or fellow nationals whenever possible. |

| Pull factors and tradition: Initially, most of Fulton county’s German population were descendants of immigration waves, “Palatines”, who settled in the Mohawk Valley in the 1700s. Some of their descendants moved into Gloversville and Johnstown in the 1840s and 1850s to find work in the glove industry. | |

| Macro | Migratory patterns of German States in 1840s and 1850s |

| Baden subsidized emigration to reduce the agricultural pressures experienced the 1850s. | |

| Demographic patterns: The Fliegel family and John Sperber immigrated between 1848 and 1855. It was a period that witnessed the greatest number of Germans immigrating to the United States. It also was a period of immigration largely represented by Germans emigrating from the south western German states. |

Table Three: Cultural, Techniological and Economic Influences on the Fliegel’s Journey to America

| Influences | Examples of Influences |

|---|---|

| Technical Innovations in North Atlantic Sea Travel | Boats & Sea Travel: Developments in Packet ship boat design and innovations of navigation |

| Inland travel Infrastructure of roadways and railways in German states and France | |

| European Economic Influences | Post War Economy: The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 took a toll on Germany’s economy. Two decades after the wars produced combination of war debt, created social structural & economic turbulence from the occupation of the French, a drain on natural resources, trade crises and agriculture disaster. |

| The price of migration: how the cost of travel impacted their decisions. | |

| German Publications & Travel Agents | Travel Literature:: Auswandererkarten, or German emigration maps in the mid 1800s offered detailed information about migrating to the United States. |

| Travel Agents & Brokers: the influence of travel agents on facilitating travel. | |

| North American Infrastructure Developments | Road, Rail and Waterways: The 1840s and 1850s saw the Mohawk Valley transitioning to a manufacturing based economy enabled by transportation developments, while still maintaining agricultural roots. The Erie Canal, completed in 1825, facilitated the development of large villages in the Mohawk Valley and provided a means to transport goods east and west. Railways between New York city and the capital region supplemented roadway travel along with innovations in waterway travel on the Hudson River. |

Based on basic questions related to how the Fliegel’s travel to European ports of departure and where immigrant ships landed in the United States, I was able to assemble evidence on their trek from Baden to Le Havre, France and their entry to American through New York City and staying in ‘Little Germany’. I then was able to assemble historical evidence of the possible influences that lead to their settling in the Gloversville, New York area.

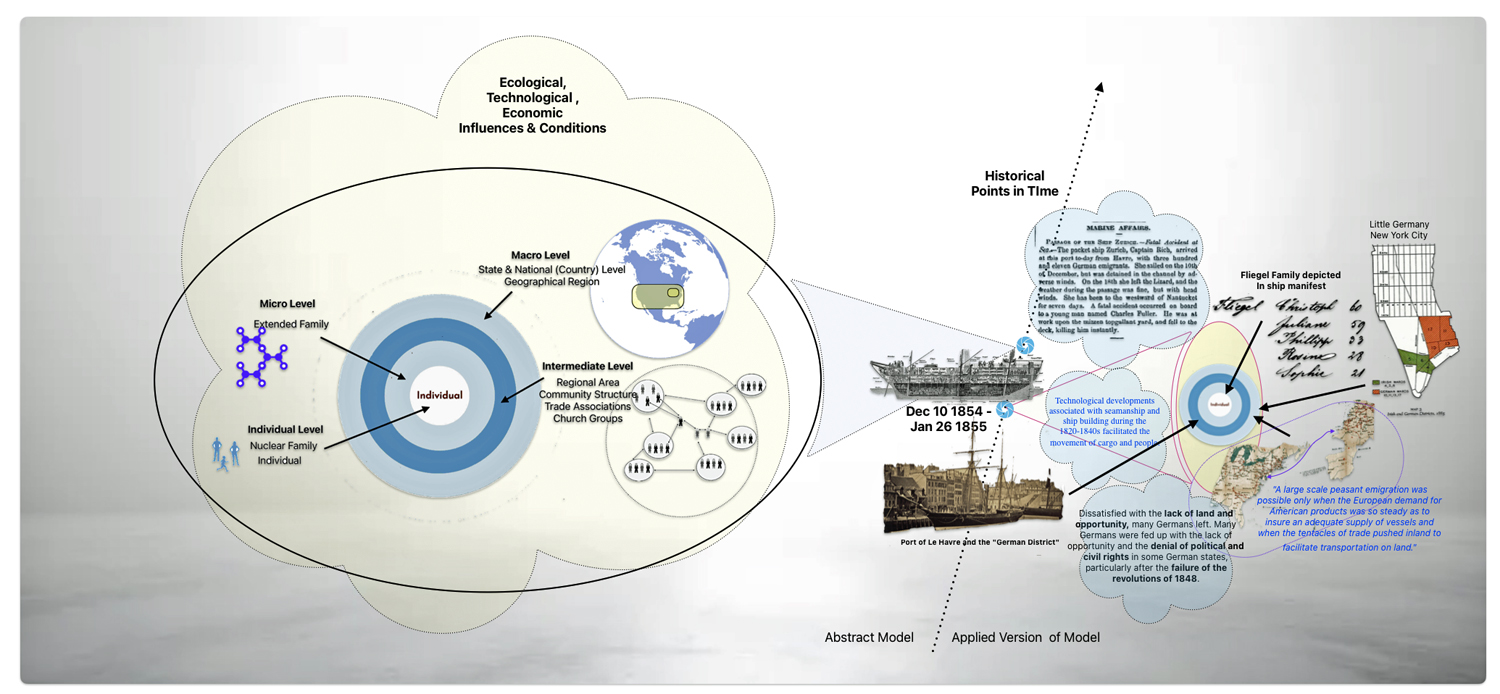

Illustration four depicts a sample of the influences I documented about the Fliegel family’s immigration to New York City from Le Havre through the lens of historical evidence that places their journey in the context of wider influences they experienced in their time.

Illustration Four: Practical Example of Viewing Different Levels of Influence on Fliegel Family Immigrating to America

U.S. and New York State census documents provided information at the micro and individual levels. I was able to document the composition of their family, their age, where they lived, marriages, children, their occupations, where they and their parents were born. This information provided a skeletal outline of their lives at the individual and micro levels in Johnstown and Gloversville, New York. For example, coupled county deed records and with historical data from insurance company maps, this information also provided possibilities of discerning the location of each of the families once the Fliegel children were married. I was able to document geographical relationships with family, work and journey to work. [6]

The census documents also provided leads for further research at the intermediate level and macro levels. I was able to conduct further research on the regional economy in the Mohawk Valley and the development of the Glove making industry in Fulton County.

David’s Story

Depending on the angle or focus of a particular story, one can provide an unique historical context to understand what was going on at a particular moment in time. Another example might help in understanding this approach.

My story of David Griffis, A Short Precious Life, provides documentation and photographs of my uncle who unfortunately died before he reached the age of two. Despite my grandparent’s attempts to obtain medical assistance at the emergency room of a local hospital, David was denied service due to his parents not having health insurance.

As indicated in the story, David could not breathe, Harold and Evelyn Griffis raced to a local hospital for emergency medical service. They then ran back to the car with David and raced to another hospital in town. The second hospital accepted David without insurance to attend to his needs. Unfortunately, time ran out. David passed away.

Without any embellishment, the story of David’s short life is remarkable and heart breaking. Provided with the basic outline of facts associated with this story, one of the immediate questions that arise is why was David refused treatment at the hospital? The unfathonable experience that Harold and Evelyn Griffis had with the death of their son David can be put into a wider historical context to try to comprehend why a child was denied access to hospital care.

If one were to look at healthcare and health insurance practices in the 1930’s, one can get a better understanding of why David did not receive medical attention. Only nine percent of the population had insurance on the eve of World War II. That percentage had more than doubled to nearly 23 percent by the end of the war. It more than doubled again by 1950 and was close to 70 percent by 1960.

The Great Depression had taken hold at this time. Many Americans were unable to afford the care they desperately needed. Insurance policies for health care coverage were practically non-existent. As a result, many hospitals across the country were thrown into financial ruin and were forced to close. Health was regarded as uninsurable at the time. When the hospital service plans finally became popular, they initially did not offer health insurance; they offered hospitalization coverage. but this was as few years after David’s untimely demise.

In addition to the state of hospital care and the health insurance industry in the Hew York state area, the social structural and economic impact on David’s situation is reflected in illustration five.

Illustration Five: David’s Story

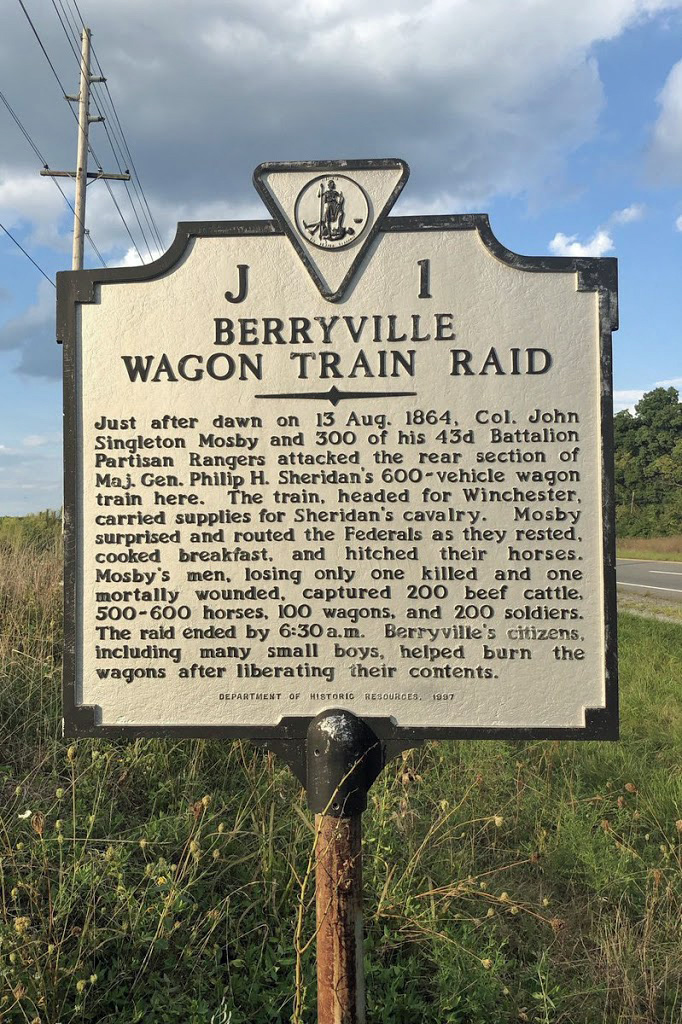

Daniel Griffis: His Capture by Mosby’s Raiders

Another example that relies heavily on indirect evidence and facts from a wider intermediate and macro level historical context is one of my stories about Daniel Griffis in the Civil War. Daniel Griffis was my second great grand uncle who was a Union army wagon master in the Civil War.

I did not know of Daniel’s involvement in the Civil War until I inadvertently found a pension file in the National Archives under the name of his father Joel Griffis. [7] In the pension request file, the Prison of War Records show a D.F. or D.E. Griffiths or Daniel Griffis, was captured at Berryville, Virginia on August 13, 1864. He was transported to Richmond, Virginia and placed in a Confederate prison. He was then sent from Richmond, Virgina to Salisbury North Carolina on October 9, 1864. While in the Salisbury Prison, he was admitted to the prison hospital October 30, 1984 and died November 4, 1864 of “Int. fever”. “Int” or “intermittent fever” in Civil War medical parlance usually referred to recurring fevers. “Intermittent fevers” was a term that was used for a variety of illnesses, notably malaria. [8] The Adjutant General Office’s letter indicates that Confederate prison records misspelled Daniel’s name as “D.F. D.E. Griffiths”. [9]

In terms of ancestry research. I could not find Daniel in U.S. or state census records after 1860. Upon receiving copy of Joel Griffis’ Civil War ‘pension request as a dependent’, I discovered Daniel’s military history and untimely death.

Daniel Griffis enlisted in the 130th infantry regiment of New York in August 1862 in Stillwater, New York. [10] This regiment had the distinction of being the only Union army volunteer regiment which was converted entirely from infantry to cavalry during the Civil War. It was ultimately renamed the First Regiment of Dragoons. [11]

At a point in his military service he became a wagon master. Available documentation indicates he was a wagon master in January or February 1864. Perhaps when the regiment was drilled in its new calvary duties in Manassas in October 1863 he assumed wagon master duties.

See related stories on Daniel and his brother William J. Griffis in the Civil War:

- Daniel Griffis – Captured, Imprisoned, & Perished March 13, 2021

- William James Griffis and Daniel Griffis – A Tale of Two Brothers (Part Three) March 5, 2021

- William James Griffis and Daniel Griffis – A Tale of Two Brothers (Part Two of Three) February 13, 2021

- William James Griffis and Daniel Griffis – A Tale of Two Brothers (Part One) February 3, 2021

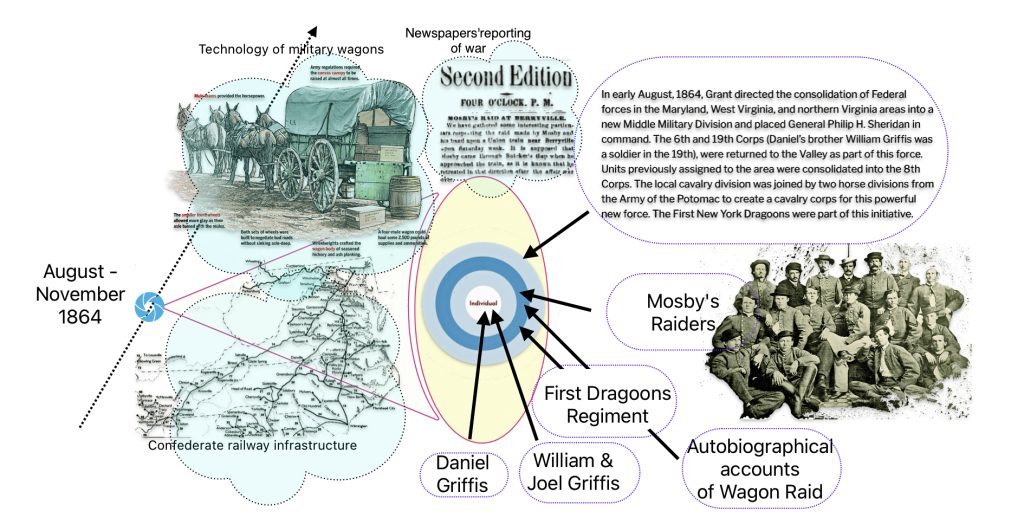

Daniel was involved in 34 major regimental engagements with the First New York Regiment of Dragoons. Virtually all of these engagements were in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. Early in the morning of August 13, 1864, Daniel and approximately 200 other soldiers were captured by the Confederate guerrilla regiment led by Colonel Mosby. Daniel was part of a reserve brigade wagon train that was captured by Mosby’s regiment.

With the absence of direct evidence of Daniel’s capture, subsequent incarceration and death, his story was created through the use of a variety of historical sources. In addition to the typical family ancestry sources of the U.S. Census, I relied upon Civil War pension records, Library of Congress records related to Civil War Regiments, published historical accounts related to Daniel’s regiments, scholarly accounts on various facets of the Civil War and ‘non-academic’ historian’s accounts on the mundane aspects of the Civil war military and the common soldier.

What is noteworthy is Civil War soldiers produced an unprecedented volume of autobiographical accounts, with publications appearing in numbers unmatched by any other war in American history. The high literacy rates among soldiers – over 90% for Union and 80% for Confederate troops – enabled this extensive documentation. [12]

The publication of these accounts followed distinct patterns. The initial wave of journals and diaries appeared immediately after the war. The main surge of memoirs began in the mid-1870s and continued steadily into the twentieth century.

These accounts emerged from multiple motivations and took various forms. They were a response to strong public interest in military history. Some were written as part of the “Lost Cause” narrative in the South. Many of the accounts documented the daily struggles and mundane details of soldier life. [13]

Example of an Autobiographical Account of Daniel’s First Regiment of Dragoons

I was fortunate to find a number of autobiographical accounts of union solders who were part of the First Dragoons as well as the 149th Ohio volunteer infantry that was providing protection for Daniel’s wagon brigade. I also had access to autobiographical accounts written by confederate soldiers that fought with Mosby’s Raiders, who captured Daniel Griffis. [14]

I have also analyzed newspaper reporting of the confederate wagon raid on August 13th, 1864. Depending on what news source a newspaper obtained their information on the raid, the facts and figures varied considerably in regard to the number of prisoners captured, the number of livestock and equine stock was confiscated, and the number of wagons burned. With few exceptions, the Union based newspapers relied on a terse telegraph message from Secretary of War Stanton who quoted General Sheridan’s comments that the result of the raid was exaggerated by the Mosby Raiders.

I also researched the state of railway technology and development as well as the condition of roadways in Confederate territory to gain an understanding of how and where Daniel was transported.

By combining these various sources, in absence of personal accounts from Daniel, I have been able to construct a story of what Daniel witnessed as a soldier. We may not know what he looked like, who he actually was and how he felt about things but perhaps putting them into a wider historical context of what he witnessed will give family members, and those interested in the common man in the civil war, a glimmer of what he experienced.

Illustration six depicts a few of those influences in the context of my model of structural and technological influences.

Illustration Six: Structural and Technological Influences on Daniel’s Last Year of Life

The following are notable observations from my research on Daniel’s life as a union soldier.

- I discovered first hand published autobiographies of individuals who served alongside Daniel in his regiment of the First New York Dragoons and the 149th Ohio volunteer infantry – an infantry unit that traveled alongside and protected Daniel’s wagon train.

- I was also able to ‘fill in life experience gaps’ associated with Daniel’s life as a confederate prisoner through autobiographical accounts from soldiers who fought in infantry units that were captured during the Berryville wagon train raid.

- To trace his Daniel’s experience in the war, I relied on academic sources that described and analyzed the major military campaigns and battles that the New York Regiment of the First Dragoons were participants.

- I also used historical accounts of the Civil War to place Daniel’s experiences in a national and regional context.

- Historical documentation on the condition of railways and roadways in the mid 1860s in the Confederacy provided a basis to document possible routes that were used to transport Daniel as a prisoner.

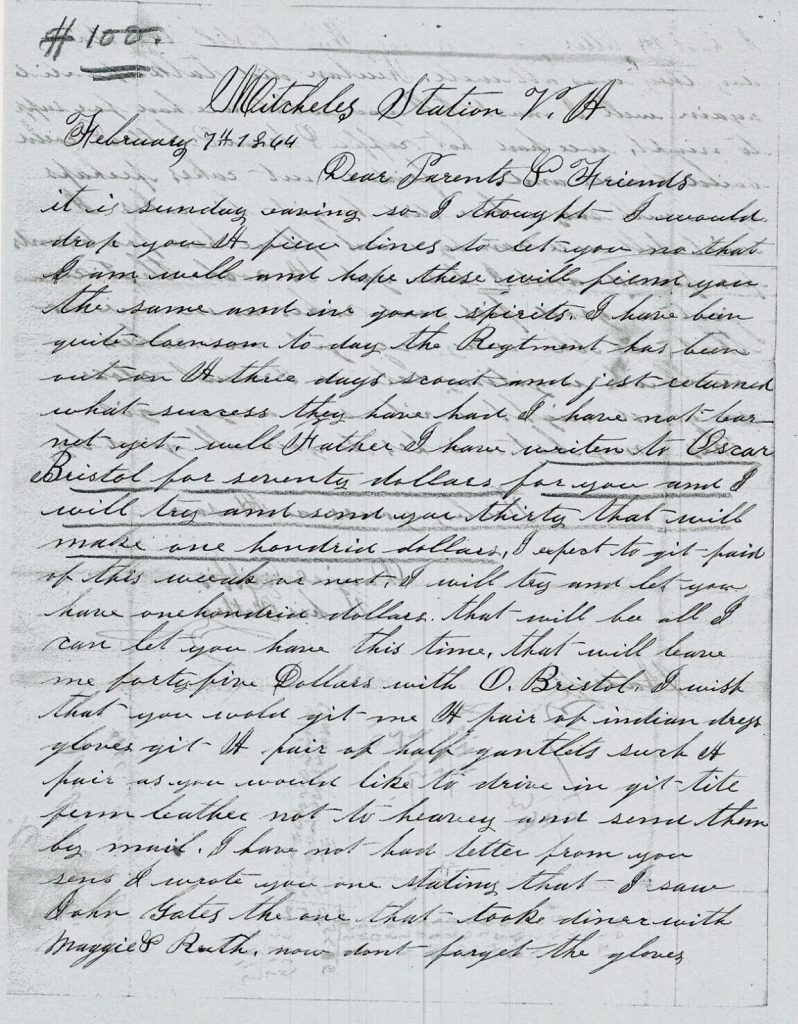

Don’t Forget the Gloves

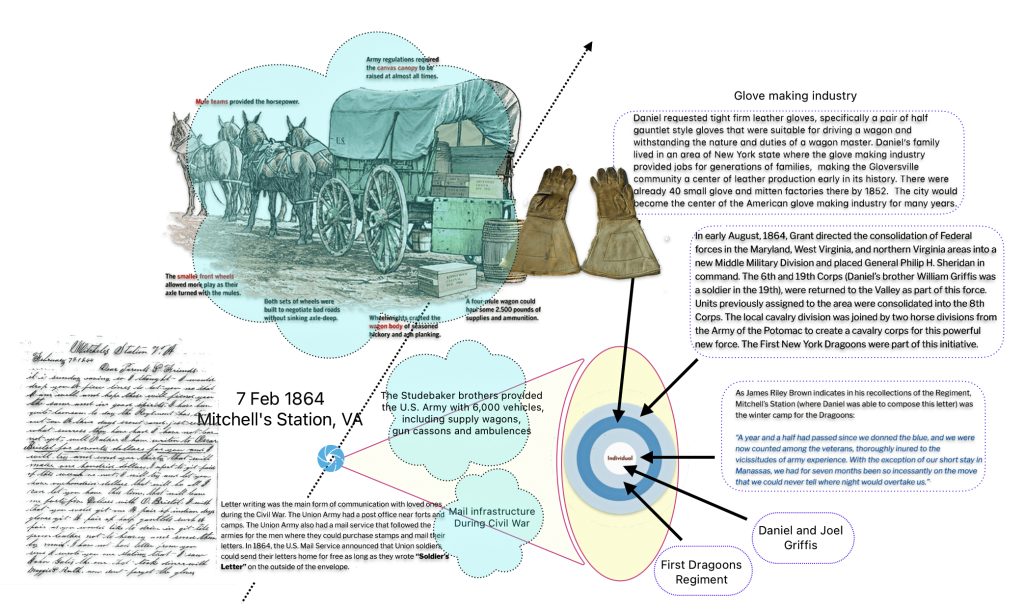

Related to Daniel’s story as a prisoner is the story about a letter he wrote to his father during the Civil War..

An handwritten letter from Daniel to his father Joel Griffis was found in the U.S. Civil War Pension File Claim 231.631 of Joel Griffis, 31 May 1877.

Joel Griffis claimed that he was economically dependent on his son Daniel Griffis. Joel unsuccessfully requested a survivor’s pension. The letter was found in the request for a pension file. It was used to bolster Joel’s argument that he was financially dependent upon his son’s service in the Army.

The two page letter was hand written while Daniel, age 32, and his regiment were camped in Mitchell’s Station, Virginia in the winter of 1863-1864. The letter touches on a number of subjects that provide a glimpse of everyday life as a soldier during war.

Daniel’s letter contains the following subjects:

- The Regiment’s scouting trip;

- Discussion on monetary support to his father and obtaining funds owed by Oscar Bristol;

- Obtaining leather gloves for his wagon master duties;

- A brief discussion about family and friends; and

- The quality of food while at winter camp at Mitchell’s Station.

I was able to paint a picture of Daniel’s story by researching various social structural levels and technological influences in 1864 in the following areas (see Illustration eight as an example) :

- the role of wagons in the civil war;

- glove making during the civil war;

- the nature of food and rations for the civil war soldier;

- the genealogical tree of Daniel’s family;

- the technical characteristics and possible innovations associated with civil war wagons;

- what is was like and what were the demands to be a wagon master in the civil war; and

- historical accounts of the various engagements of the First Dragoons.

Many of these observations lead to documenting social, cutlural, economic and technological influences and conditions that had an impact on Daniel’s life as a soldier.

Illustration Seven: Structural and Technological Influences: Daniel’s Letter

The Concepts of Selection and Significance

While recognizing the impact of various social, economic, cultural, technological influences on our ancestors, it begs the question on how does one pick and choose influences at various social levels and highlight cultural, technological or other factors in weaving stories from our genealogical evidence.

There is no easy answer. Selection is influenced by the questions being asked about the past. Perhaps one way to help with the ‘selection’ process is to frame questions of why or how it was possible something happened. Was it due to how family members were raised or were there influences in the local community or larger society? Did the local or regional economy have an impact on what you are writing about?

Edward Hallett Carr, an English historian, fundamentally viewed history as a continuous dialogue between the present and the past, where facts and their interpretation are inseparably intertwined. He rejected the notion that history was simply a collection of objective facts. In Carr’s view, facts fall into two categories: basic facts of the past (like “the Civil War was fought between 1860 and 1865) and facts chosen by historians for their significance. Carr emphasized that historical work is constructed and represents a discourse about the past rather than a mere reflection of it. [13]

Historical facts are not simply discovered and recorded but are actively selected and arranged by historians, and family historians, through a process of interpretation. The historian actively shapes historical narratives by choosing which facts to emphasize and interpret, rather than being a passive recorder of events. Facts do not exist in a pure form but are always “refracted through the mind of the recorder“.

Objectivity in history comes not from avoiding selection but from the family historian’s “sense of direction in history” and ability to choose significant facts that contribute to deeper historical understanding. This challenges the traditional notion of absolute historical objectivity while maintaining scholarly rigor.

Final Thoughts

The family historian actively shapes historical understanding by selecting and interpreting facts rather than merely collecting them. When writing a story, certain facts and evidence are highlighted to provide a background or historical texture to the story.

While much of my time is spent on gathering and analyzing facts and evidence that are directly associated with a specific person, family or family object, understanding and documenting the historical context requires in-depth research across multiple sources. This investment of time and focus creates richer, more meaningful, engaging family narratives that bring ancestors’ stories to life.

In addition to the above mentioned conceptual model of general social structural levels and other influences (cultural, technical, economic, political, environmental, etc), the perspective of time can be added to the mix to provide context and historical meaning to family history.

My views on adding different views of time are discussed in another story.

Sources

Feature Image: The image depicts the conceptual model for categorizing social structural influences and other influences that may be sources of evidence for providing an historical context for family stories. An application of the model is also depicted.

[1] Carmen J Finley, Creating a Winning Family History, Basic Standards for Family History Research and Writing, NGS Special Publication No. 99, Arlington: National Genealogical Society, 2010 , Page 20

[2] Jacqueline Jones, A Historian Among Genealogists: Working on Who Do You Think You Are?, Perspectives on History, Jan 1, 2013, https://www.historians.org/perspectives-article/a-historian-among-genealogists-working-on-who-do-you-think-you-are-january-2013

[3] See, for example, the two referenced sources below that merely provide influences that can be considered in writing a genealogical story.

Perilla StammlerJaliff, 75 Social Factors Examples (With Definition). 3 Sep 2023, HelpfulProfessor.com, https://helpfulprofessor.com/social-factors-examples/

Chris Drew, 101 Contextual Factors Examples, HelpfulProfessor.com, https://helpfulprofessor.com/contextual-factors-examples/

[4] See for example,:

Lloyd, Christopher. “The Methodologies of Social History: A Critical Survey and Defense of Structurism.” History and Theory, vol. 30, no. 2, 1991, pp. 180–219. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2505539

Crothers, Charles. “Recent Works on Social Structure: A literature – Review Essay, Humboldt Journal of Social Relations, vol. 22, no. 2, 1996, pp. 97–107. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23263034 .

Willer, David, et al. Social Theory and Historical Explanation, Humboldt Journal of Social Relations, vol. 22, no. 2, 1996, pp. 63–84. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23263032 .

Knottnerus, J. David. Social Structure: AN Introductory Essay, Humboldt Journal of Social Relations, vol. 22, no. 2, 1996, pp. 7–13. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23263028

Porpora, Douglas V. , Are There Levels of Social Structure?, Humboldt Journal of Social Relations, vol. 22, no. 2, 1996, pp. 15–29. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23263029

Spillman, Lyn. , How are Structures Meaningful? Cultural Sociology and Theories of Social Structure, Humboldt Journal of Social Relations, vol. 22, no. 2, 1996, pp. 31–45. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23263030

[5] See the following examples for great tips for putting facts into context:

Putting Family History into Context: A Special Issue of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly. NGS Quarterly 88 (December 2000).

Everton Publishers, The Handybook for Genealogists, United States of America, 11th ed. (Logan, Utah: Everton Publishers, 2006).

Sandra MacLean Clunies, “Writing the Family History: Creative Concepts for a Lasting Legacy,” in Putting Family History into Context: A Special Issue of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly, NGS Quarterly 88 (December 2000): 247–65

Val D. Greenwood, The Researcher’s Guide to American Genealogy, 3rd ed. (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2000),

Patricia Law Hatcher, Producing a Quality Family History (Salt Lake City: Ancestry, 1996).

Christine Rose, “Family Histories,” in Elizabeth Shown Mills, ed., Professional Genealogy: A Manual for Researchers, Writers, Editors, Lecturers, and Librarians (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2001), 449–74.

[6] The Sanborn Map Company was a prominent American publisher of detailed fire insurance maps from 1867 to the late 20th century. The maps provided detailed information about the size, shape, construction materials and function of buildings in urban areas. They also included details like street names and widths, property boundaries, building use, and the location of water mains, fire alarms and fire hydrants and the exact street numbers of buildings.

While originally created for insurance purposes, Sanborn maps have become invaluable historic resources. They allow researchers to trace urban development and changes over time, providing unparalleled detail about the built environment of American cities from the late 1800s through the mid-1900s. The Library of Congress holds the largest collection of Sanborn maps, which are widely used by historians, architects, genealogists and others.

Sanborn Maps, Wikipedia, This page was last edited on 1 May 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanborn_maps

Sanborn Maps, About This Collection, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/sanborn-maps/about-this-collection/

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Gloversville, Fulton County, New York., Sanborn Map Company, Published Oct 1902, Digital Id http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3804gm.g3804gm_g059511902

Coons, Alana, Let’s Talk about Sanborn Maps, University Heights Historical Society, https://www.uhhs-uhcdc.org/blog/lets-talk-sanborn-maps

Introduction to the Collection, Sanborn Maps Collection, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/sanborn-maps/articles-and-essays/introduction-to-the-collection/

Interpreting Sanborn Maps, Fire Insurance Maps at the Library of Congress: A Resource Guide, Library of Congress, https://guides.loc.gov/fire-insurance-maps/sanborn-interpreting

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map: How to Read Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, The Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia , https://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/collections/maps/sanborn/web/details.html

How to: Use Sanborn Maps City Archives & Special Collections, New Orleans Public Library, https://nolacityarchives.org/2024/01/08/how-to-use-sanborn-maps/

[7] May 31, 1877 letter from U.S. Adjutant General’s Office to the Bureau of Pensions, Department of Interior, part of the file of Joel Griffis application for a military pension on behalf of Daniel Griffis, Pension File Application No. 231.631, National Archives, Civil War Pensions.

Joel Griffis claimed that he was economically dependent on Daniel Griffis and unsuccessfully requested a survivor’s pension.

[8] Goellnitz, Jenny, Civil War Medical Terms, E-History, Department of History, Ohio State University, Page was accessed January 19, 2021

[9] D. H. Rucker, D.H., Acting Quartermaster General, Brevet Major General, Quartermaster General’s Office, General Orders No. 7, February 20, 1868. Names of Soldiers who in Deference of the American Union, Suffered Martyrdom in the Prison Pens Throughout the South, Washington, Government Printing Office, 1868, Page 44 of the linked version, Page 134 of the original version.

[10] Jim Griffis, William James Griffis and Daniel Griffis – A Tale of Two Brothers (Part One), 3 Feb 2021, Griffis Family: Selected Stories from the Past, https://griffis.org/william-james-griffis-and-daniel-griffis-a-tale-of-two-brothers-part-one/

[11] Jim Griffis, The First New York dragoons – Daniel Griffis, 12 Dec 2022, Griffis Family: Selected Stories from the Past, https://griffis.org/the-first-new-york-dragoons-daniel-griffis/

[12] “Civil War armies were the most literate in history to that time. More than 90 percent of white Union soldiers and more than 80 percent of Confederate soldiers were literate, and most of them wrote frequent letters to families and friends … .”

McPherson, James, For Cause and Comrades Why Men Fought in the Civil War, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997, Domina, L. (2017, July 26). Autobiography: White Women during the Civil War. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature. Retrieved 21 Dec. 2024, from https://oxfordre.com/literature/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.001.0001/acrefore-9780190201098-e-659

[13] On the Front Lines of History, The Gettysburg Compiler, Civil War Institute, Gettysburg College, https://gettysburgcompiler.org

What They Wrote, What They Saved: The Personal Civil War, 15 Oct 2014 through 20 Mar 201, Harvard Radcliffe Institute, https://www.radcliffe.harvard.edu/event/2014-what-they-wrote-saved-exhibition

McPherson, James, For Cause and Comrades Why Men Fought in the Civil War, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997, Domina, L. (2017, July 26). Autobiography: White Women during the Civil War. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature. Retrieved 21 Dec. 2024, from https://oxfordre.com/literature/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.001.0001/acrefore-9780190201098-e-659

About Personal Narratives and Diaries, American Civil War: Resources in Special Collections, University Libraries, University of Maryland, https://lib.guides.umd.edu/c.php?g=326774&p=2197450

Inscoe, John. “Civil War Journals, Diaries, and Memoirs.” New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified Aug 25, 2020. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/civil-war-journals-diaries-and-memoirs/

[14] See for example:

James Riley Bowen, Regimental History of the First New York Dragoons: Originally the 130th N. Y. Vol; Infantry; During Three Years of Active Service in the Great Civil War, originally published by author 1900, Reprinted by Forgotten Books, 2012 https://archive.org/details/regimentalhistor00bowe/page/n7/mode/2up

Munson, John W. Reminiscences of a Mosby Guerrilla. New York: Moffat, Yard, and Co., 1906, https://archive.org/details/reminiscencesam00munsgoog

Perkins, George, A summer in Maryland and Virginia; or, Campaigning with the 149th Ohio volunteer infantry, a sketch of events connected with the service of the regiment in Maryland and the Shenandoah Valley, Virginia, Chillicothe, O. The Sholl printing company, 1911, https://archive.org/details/summerinmaryland00perk/page/n3/mode/2up

For discussions on the use of autobiographies, see for example:

Redlich, Fritz. “Autobiographies as Sources for Social History: A Research Program.” VSWG: Vierteljahrschrift Für Sozial- Und Wirtschaftsgeschichte, vol. 62, no. 3, 1975, pp. 380–90. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20730257. Accessed 29 Oct. 2023.

Civil War Memoirs .” American History Through Literature 1870-1920. . Encyclopedia.com. 18 Oct. 2023 https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/culture-magazines/civil-war-memoirs

Saunders, Catherine E. “American Civil War Era Memoirs and Autobiographies.” Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism, edited by Lawrence J. Trudeau, vol. 272, Gale, 2013. Gale Literature Resource Center.

Jaume Aurel, “Autobiographical Texts as Historical Sources: Rereading Fernand Braudel and Annie Kriegel.”. Biography, vol. 29, no. 3, 2006, pp. 425–45. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23540525. Accessed 29 Oct. 2023.

[15] Carr, Edward Hallet, What is History, Cambridge: University of Cambridge, 1966

Woznicki, Chris,The Epistemological Foundations of History: Bloch and Carr’s Philosophy of History Compared, 12 Mar 2018, CWoznicki Think Out Loud, https://cwoznicki.com/2018/03/12/the-epistemological-foundations-of-history-bloch-and-carrs-philosophy-of-history-compared/

Amelia Heath (2010) E.H. Carr: Approaches to Understanding Experience and Knowledge, Global Discourse, 1:1, 24-46, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/23269995.2010.10707835

UKEssays. Edward Hallet Carrs Arguments In What Is History?. 2 May 2017, Retrieved from https://www.ukessays.com/essays/philosophy/edward-hallet-carrs-arguments-in-what-is-history-philosophy-essay.php?vref=1