There are a number of stories that reference the marriage of Harold William Griffis and Evelyn Teresa Dutcher. Given the number of photographs and documents related to their marriage it is befitting to provide a story solely to the subject.

Leading Up to the Marriage

Harold Griffis and Evelyn Dutcher began dating during their last two years at Gloversville High School, Gloversville, New York. Both were honor students and participated in a number of clubs and activities in their high school careers. William graduated from Gloversville High School with a commercial diploma and initially worked in the Gloversville YMCA after high school graduation. Evelyn graduated with a classical arts degree and immediately went on to obtain a college degree at the New York State teacher’s college in Albany, New York.

Having decided to become a minister while he was in high school, Harold realized the need to obtain a college degree. In his post high school graduate year he was tutored by his high school sweetheart, Evelyn, to take the required college entrance exams to enter college. With Evelyn’s help, Harold passed the college entrance exams. Harold then applied and was accepted to Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut.

Being one year ahead for Harold in her college studies, Evelyn Dutcher graduated from the New York State College for Teachers, Albany , New York in 1924. She went back to the Gloversville area and taught Latin at the Johnstown High School in Johnstown, New York while living with her parents [1].

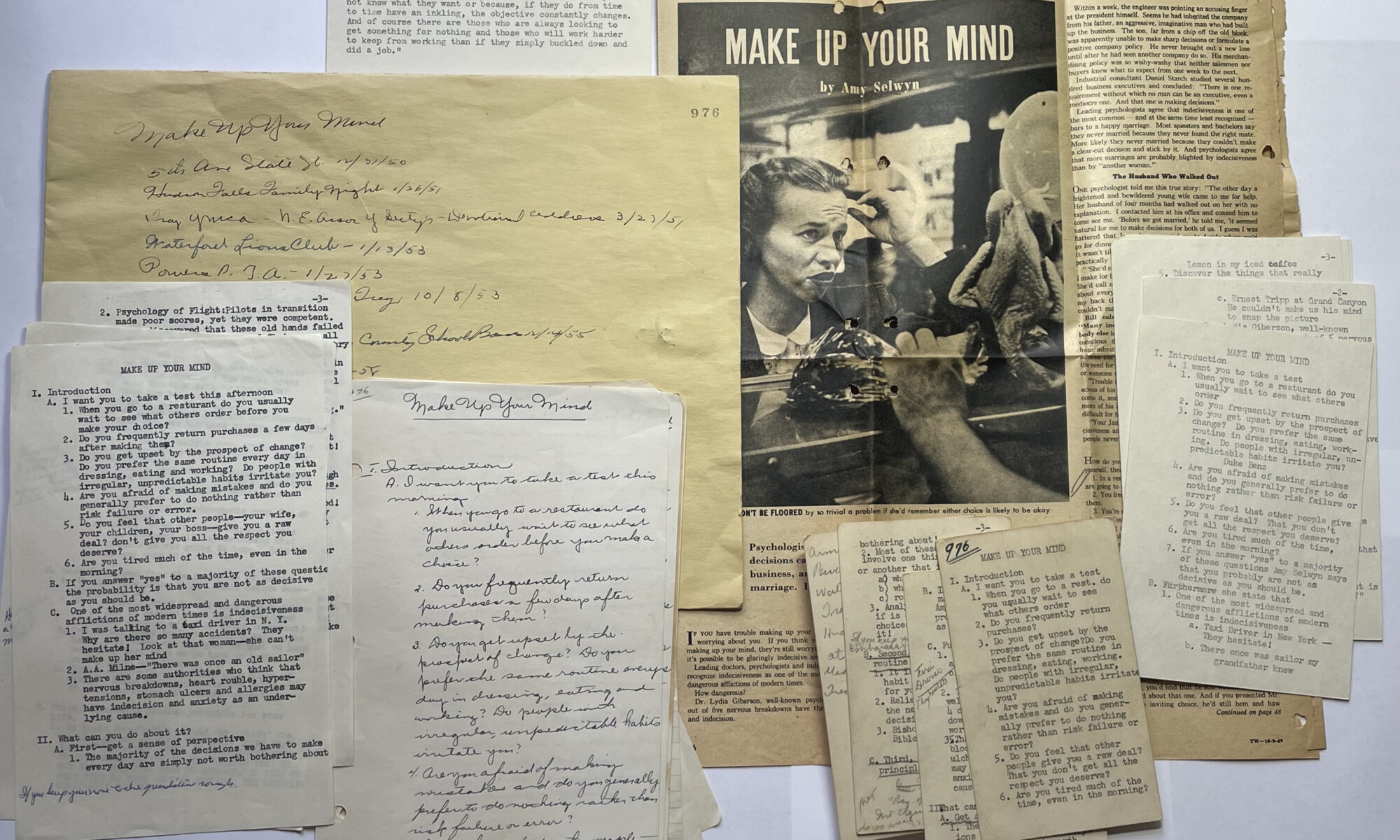

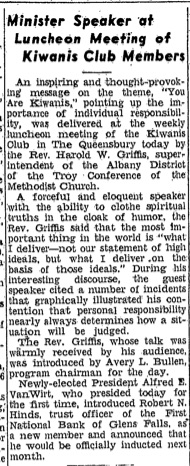

After Harold’s graduation in 1925, he began is career as a minister and pastor at two local Methodist Episcopal church: Jonesville and Groom’s Methodist M.E. churches in New York state.

A letter of Intent

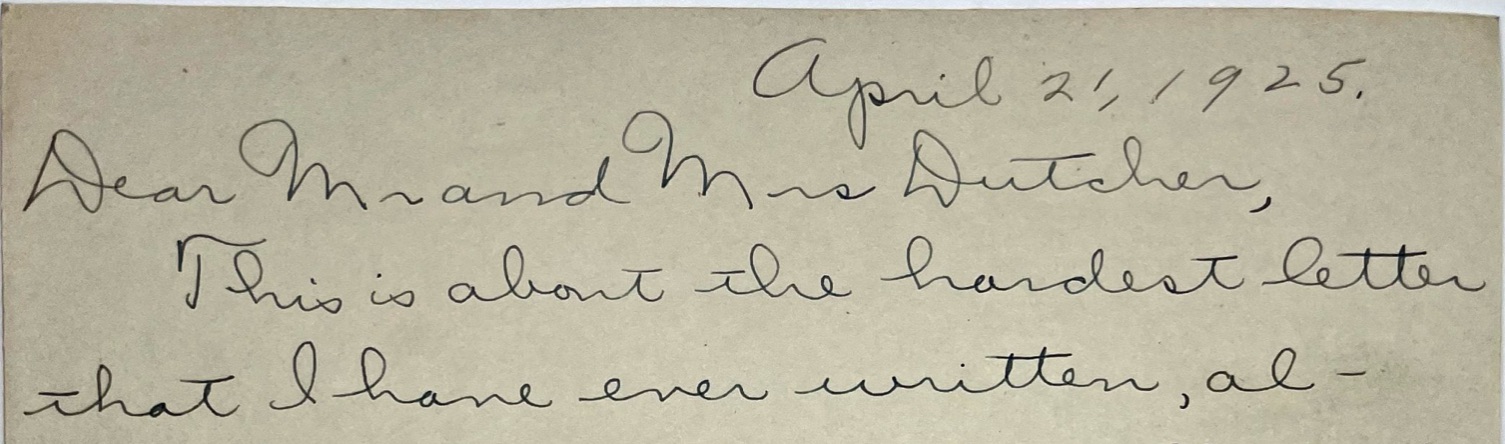

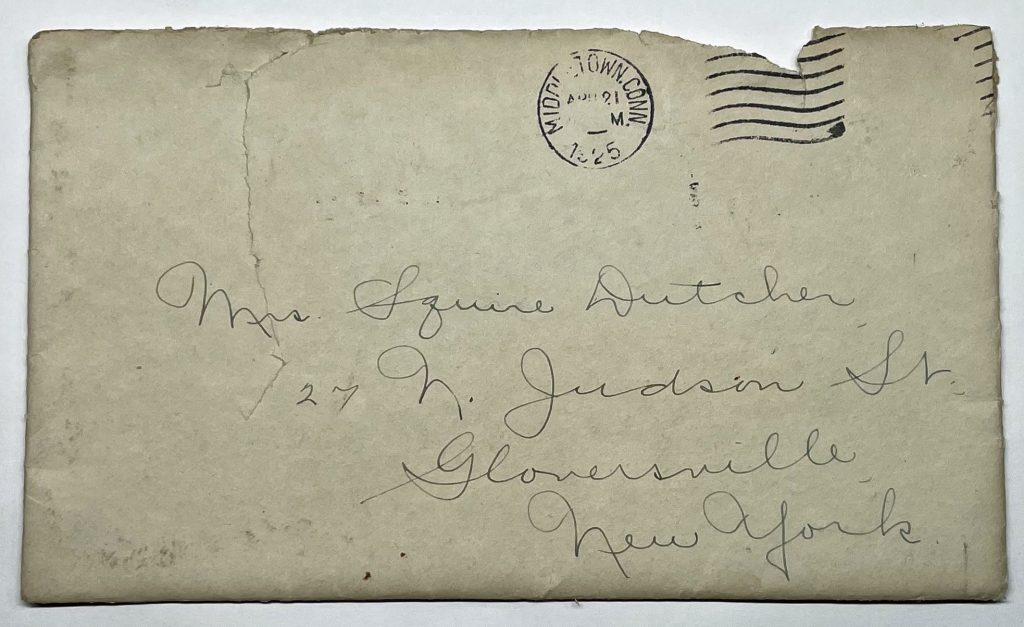

Prior to graduation, Harold wrote a letter from college to Squire and Jane Dutcher, his future father and mother-in-law. While Harold knew Jane and Squire Dutcher since perhaps his childhood, it was a letter he found to be difficult to write.

“This is about the hardest letter that I have ever written, although you probably all ready know about that which I am writing. Evelyn and I are engaged.”

The letter and a response from Jane Dutcher was kept by Harold and Evelyn through time. Perhaps Jane Dutcher kept Harold’s letter throughout her lifetime or gave it to her daughter Evelyn. Perhaps Evelyn or Harold had kept Jane’s reply. Regardless of why the two letters still exist, it is fortunate to have a piece of their lives and courtship memorialized in the letters.

Many letters similar to these have been written by young men to their beloved’s parents to either ask for her hand in marriage, indicate their sincere desires of love and fidelity to their daughter.

Harold’s letter reflects in many ways the nature of his personality. He had high values and principles that guided his behavior and fashioned his goals in life. Family relationships were very important to hm. “Home’ meant more than a physical place. While being comfortable in a home and having a sufficient standard of living was important, he valued mutual respect and trust among those who were important to him. The letter also reflects his empathy for Jane and Squire. While his future job as a minister may require moving from one church to another, he acknowledges their desire for Harold and Evelyn to be close to ‘home’. He also wants Evelyn’s parents to know he will alway provide the best for their daughter.

The letter also refers to an ‘unpleasant’ episode in Harold’s life.

“Last year my heart was broken, Mrs. Dutcher, for I suddenly found that my home was not quite all that I thought it to be. For a while I did not care what happened and then I saw that it was for me to build a home that would come up to my ideal.”

It is not known exactly what had transpired at the Griffis household in 1924. However, it is possible that Harold was alluding to an incident associated with his father Charles Griffis. Charles was a Deacon to a church in Gloversville, NY.

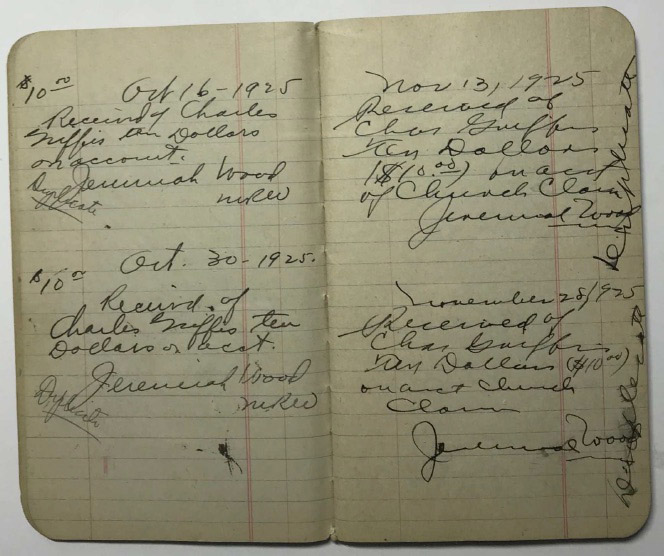

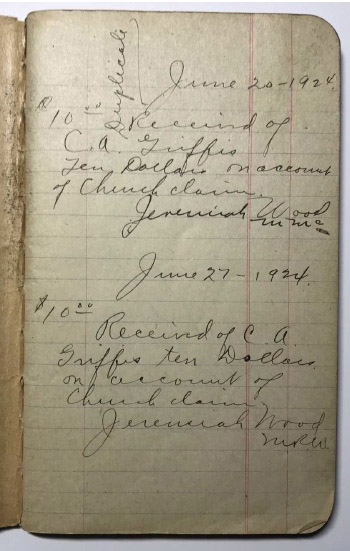

Purportedly Charles Griffis misappropriated funds from the church. The reason is unknown. A small ledger book of his personal accounts was saved by Charles and subsequently saved by his wife Ida Sperber Griffis when Charles passed away in 1926. Harold kept the small ledge book among his personal possessions. After his passing, Evelyn Griffis kept the ledges books. I found the book in her possessions after she passed away.

The book documents 57 payments of either $5.00 or $10.00 payments between June 20, 1924 and August 6, 1926. Charles paid a total of $490.00 to a Jeremiah Wood. In present day terms, this was about $6,000 in funds. [2] Jeremiah Wood was a Lawyer in Gloversville. Mr. Wood evidently had a legal relationship with either Charles or the church and was responsible for collecting and documenting the payments. [3]

Given Harold’s high ideals as a young man in his early 20’s, the discovery of his father’s misdeeds may have been devastating.

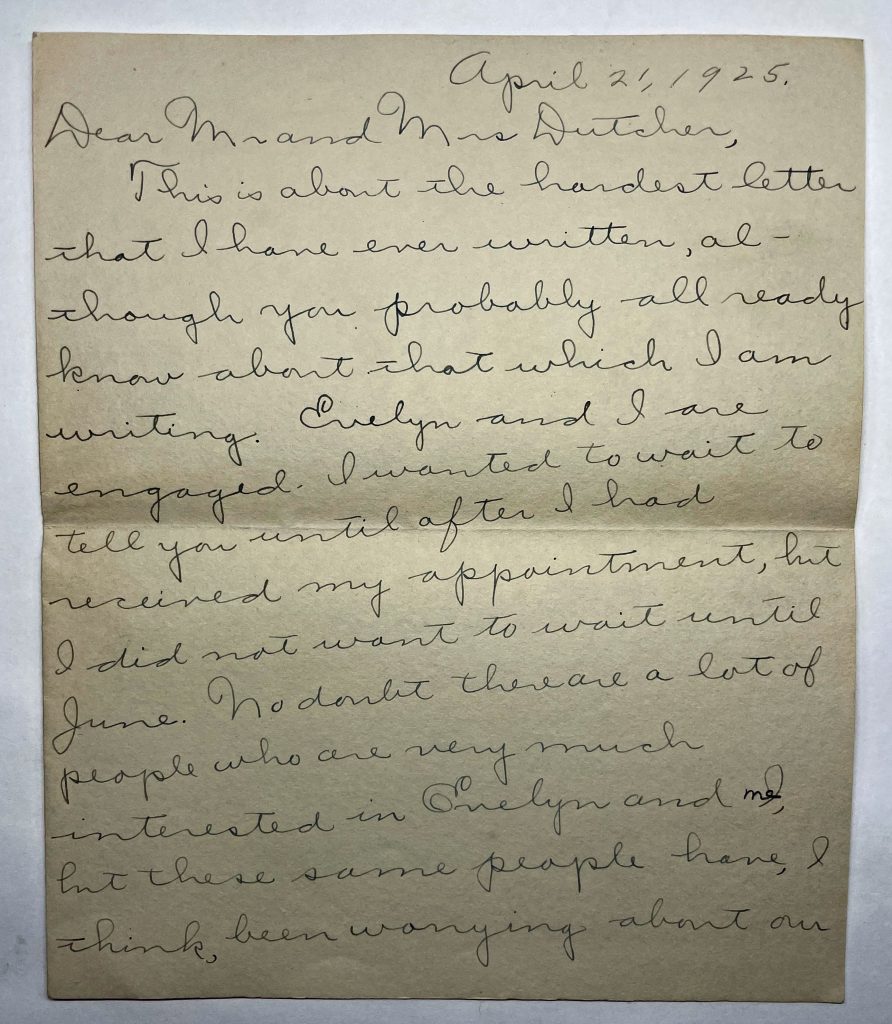

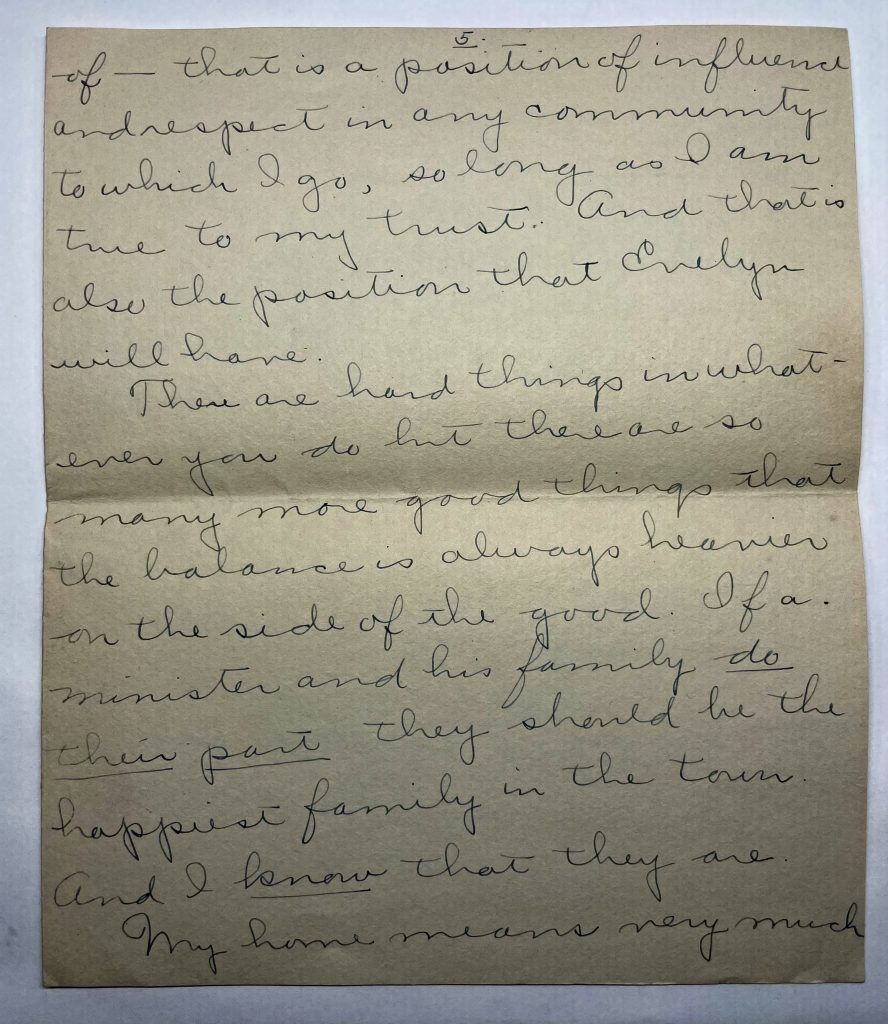

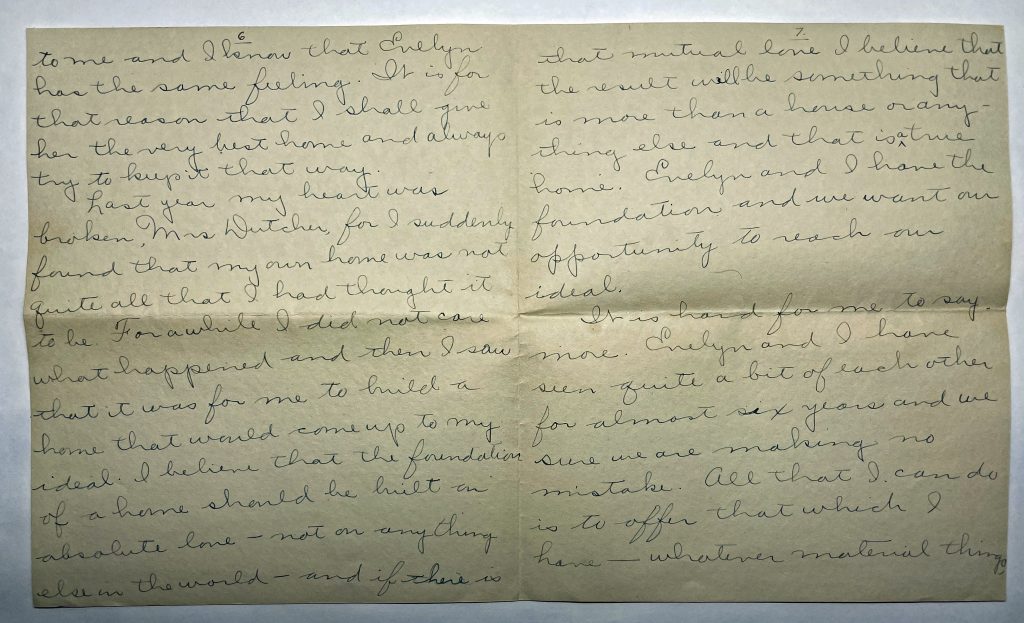

The following is a transcript of Harold’s letter. The original copies of the letter are also provided.

April 21 1925

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Dutcher,

This is about the hardest letter that I have ever written, although you probably all ready know about that which I am writing. Evelyn and I are engaged. I wanted to wait to tell you until after I have received my appointment, but I did not want to wait until June. No doubt there are a lot of people who are very much interested in Evelyn and me, but these same people have, I think, been worrying about our business a little too much. If I had waited until June, I am quite sure that these folks would have been so curious that they would have made Mr. Dutcher and you uneasy and me righteously indignant. Yes, a preacher is permitted to get righteously indignant. So I think it is best to settle things now so that we shall all know just where we stand.

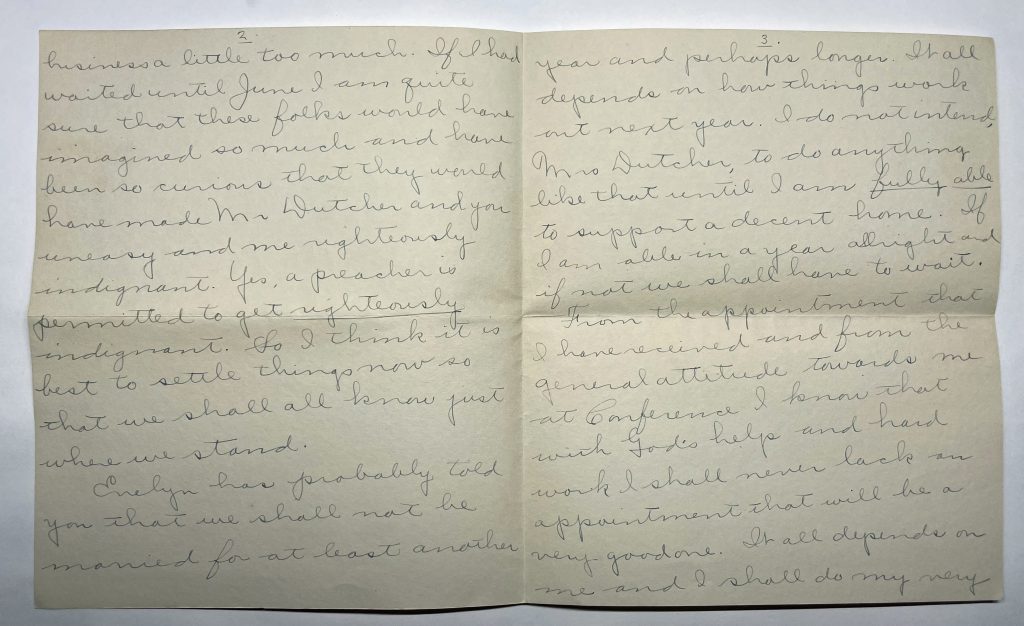

Evelyn has probably told you that we shall not be married for at least another year and perhaps longer. It all depends on how things work out next year. I do not intend, Mrs. Dutcher, to do anything like that until I am fully able to support a decent home. If I am able in a year all right and if not we shall have to wait.

From the appointment that I received and from the general attitude towards me at Conference I know that with God’s help and hard work I shall never lack an appointment that will be a very good one. It all depends on me and I shall do my very best.

I have no doubt that my life spent in Troy Conference and that means that I never will be so very far away from Gloversville. I mentioned this to remind you that Evelyn will never be far away from home, perhaps not nearly so far as she would be if she taught somewhere else.

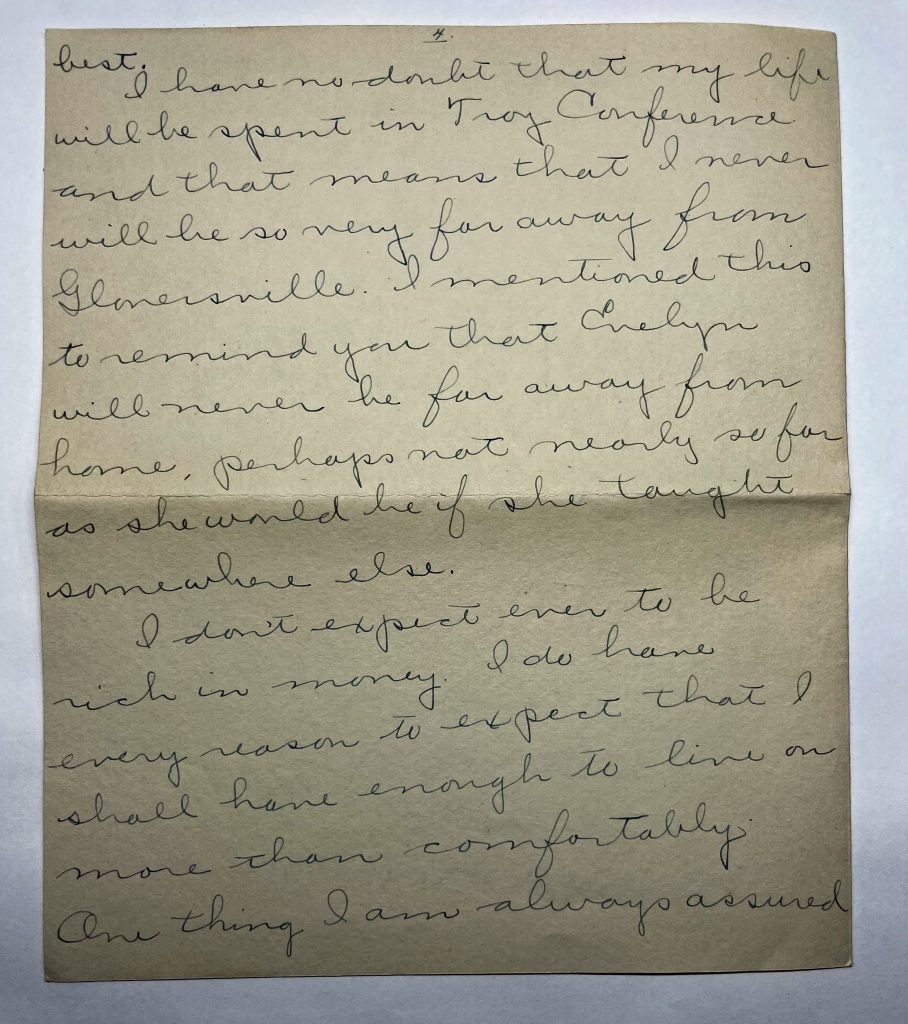

I don’t expect ever to be rich in money. I do have every reason to expect that I shall have enough to live on more than comfortably. One thing I am always assured of – that is a position of influence and respect in any community to which I go, so long as I am true to my trust. And that is also the position that Evelyn will have.

There are hard things in what ever you do but there are so many more good things that the balance is always heavier on the side of the good. If a minister and his family do their part they should be the happiest family in the town. And I know that they are.

My home means very much to me and I know that Evelyn has the same feeling. It is for that reason that I shall give her the very best home and always try to keep to that way.

Last year my heart was broken, Mrs. Dutcher, for I suddenly found that my home was not quite all that I thought it to be. For a while I did not care what happened and then I saw that it was for me to build a home that would come up to my ideal. I believe that the foundation of a home should be built on absolute love – not on anything else in the world -and if there is that mutual love I believe that the result will be something that is more than a house or anything else and that is a true home. Evelyn and I have the foundation and we want our opportunity to reach our ideal.

It is hard for me to say more. Evelyn and I have quite a bit of each other for almost six years and we sure we are making no mistake. All that I can do is to offer that which I have – whatever material things whatever else – but greatest of all I offer myself to Evelyn, such as I am with my promise that has never yet been broken that I shall do my best to help her to have a true home.

Please write me Mrs. Dutcher and you too Mr. Dutcher.

Very sincerely,

Harold

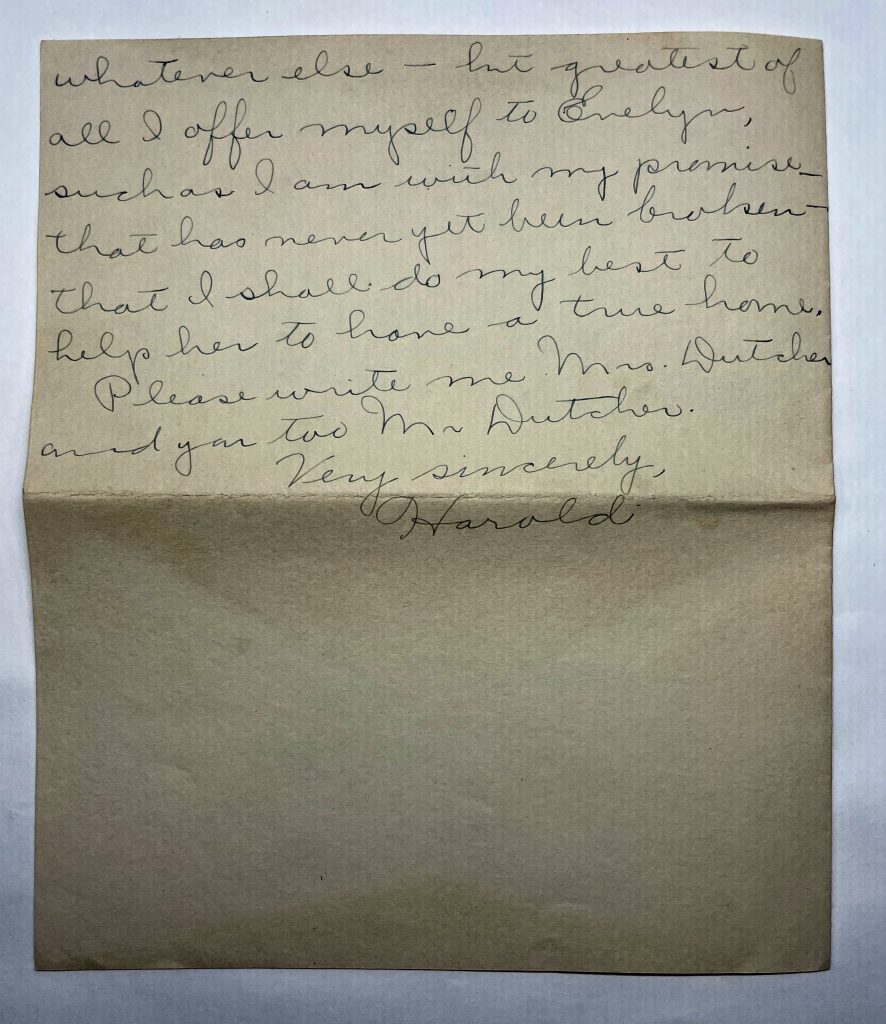

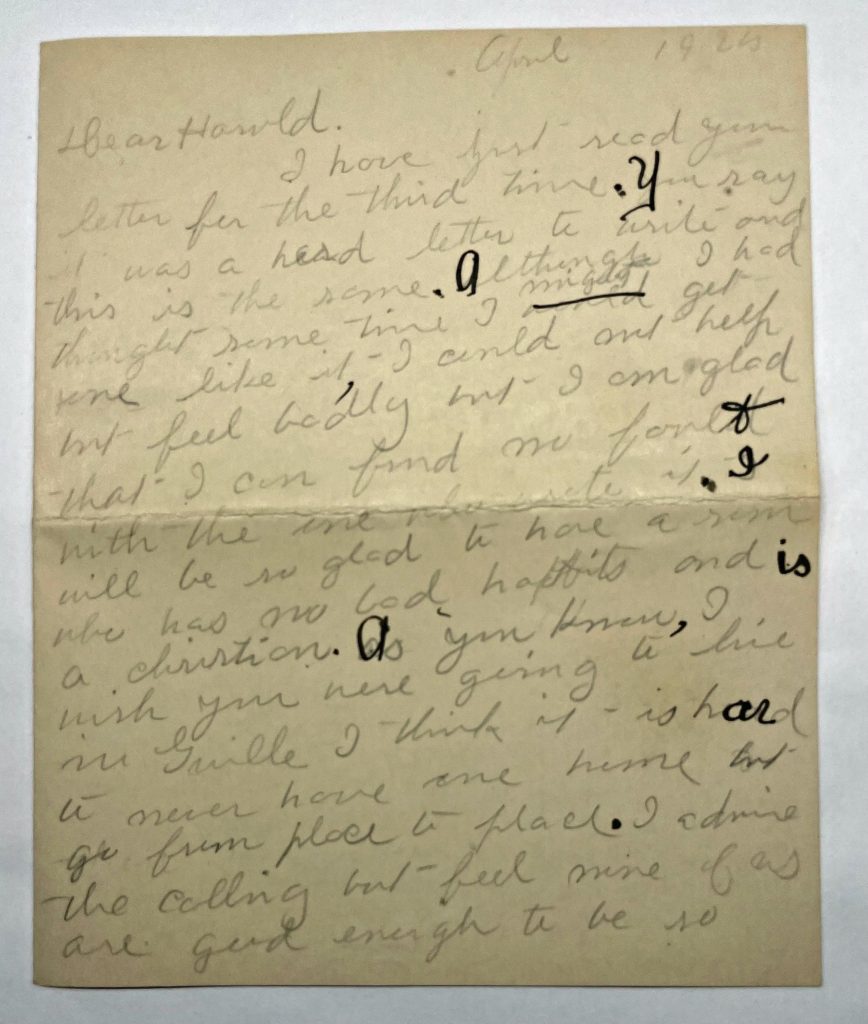

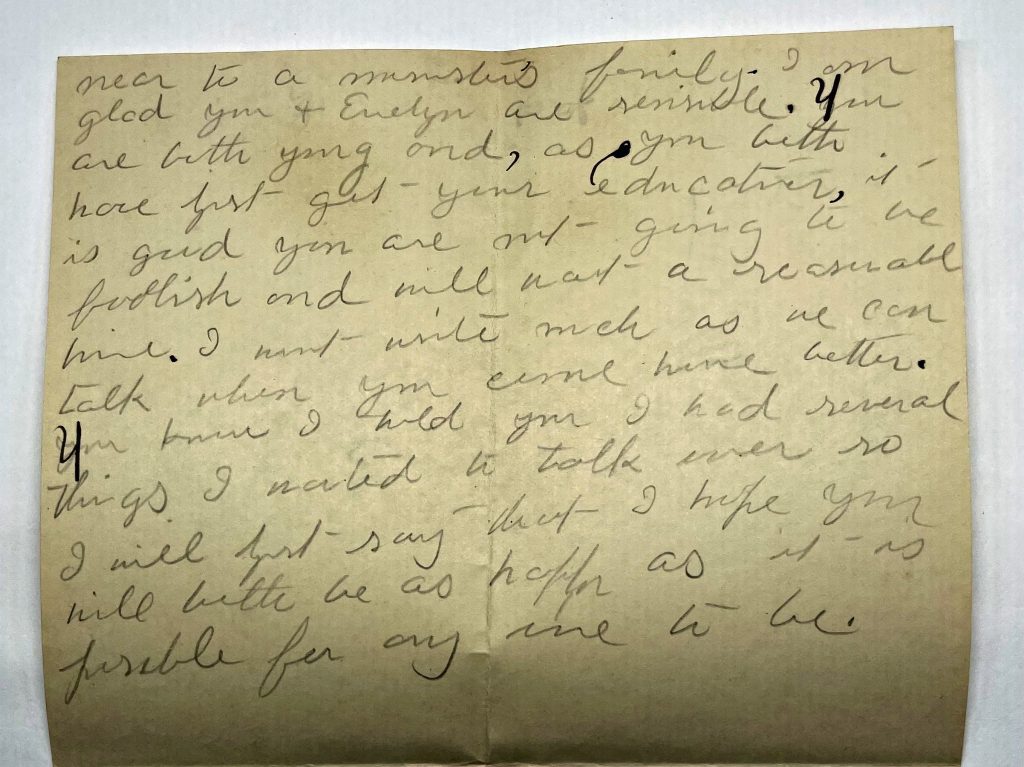

Jane Dutcher provided her future son-in-law with a brief but heartfelt letter. She read Harold’s letter three times before writing her reply which indicates she had given much thought about young Harold’s letter. She indicates she is proud of having Harold as a future son in law. While she would like to have the young couple living near or in Gloversville, but she hopes they will “both be as happy as it is possible for anyone to be”.

The following is a transcribed version of the letter.

April 1925

Dear Harold

I have just read your letter for the third time. You say it was a hard letter to write and this is the same. Although I had thought some time I might get one like it- I could and help but feel badly but I am glad that I can find no fault with the one who wrote it . I will be so glad to have a son who has no bad habits and is a christian. As you know, I wish you were going to live in Gloversville. I think it is hard to never have one home and go from place to place. I admire the calling but feel mine if as are great enough to be so near to a minister’s family. I am glad you + Evelyn are sensible. You are both young and, as, you both have first get your education, it is good you are not giving to be foolish and will wait a reasonable time. I won’t write much as we can talk when you come home better. You know I told you I had several things I wanted to talk over so I will first say that I hope you will both be as happy as it is possible for any one to be.

The following are copies of Jane Dutcher’s actual letter.

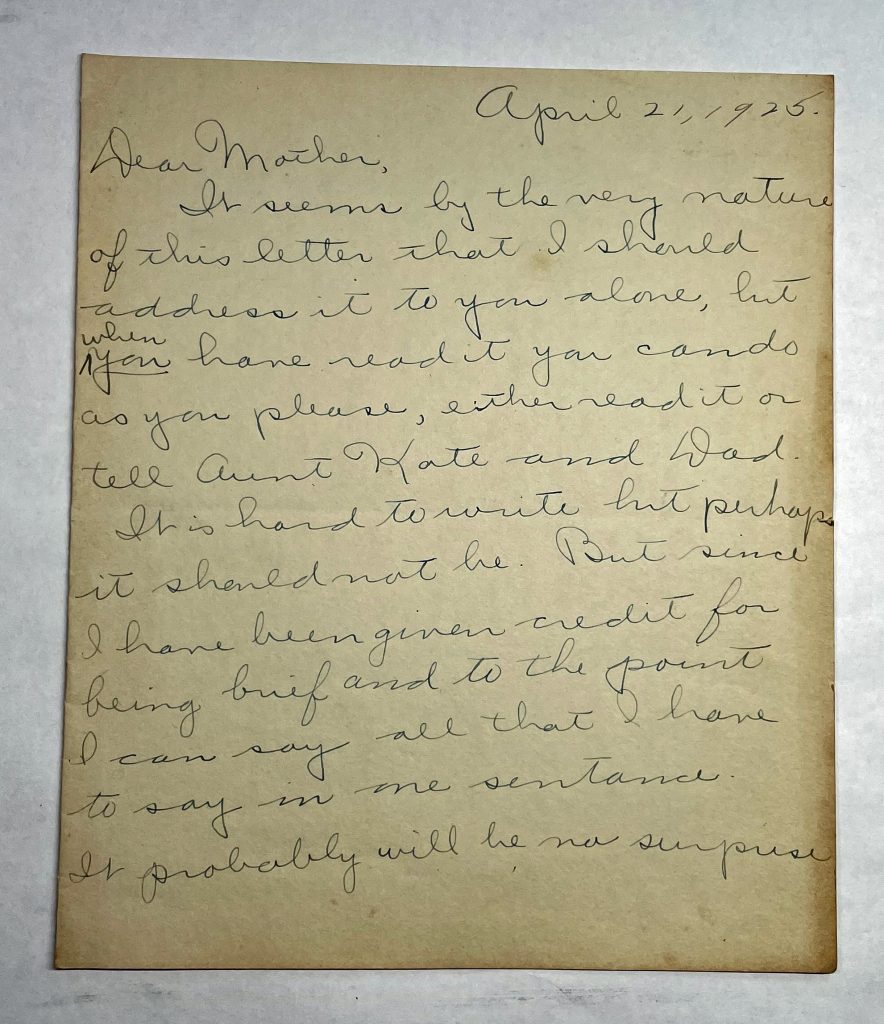

A Letter to His Mother

Harold also wrote a letter to his mother. This letter was only addressed to his mother and not to both his father and mother. Perhaps Harold was still having mixed emotions about his father’s situation with the church.

“ It seems by the very nature of this letter that I should address it to you alone, but when you have read it you can do as you please, either read it or tell Aunt Katie and Dad. “

The following is a transcribed version of the letter. It is not known if there was another page to the letter. Otherwise, it was a letter that ends without a closing salutation of his name.

April 21, 1925

Dear Mother,

It seems by the very nature of this letter that I should address it to you alone, but when you have read it you can do as you please, either read it or tell Aunt Katie and Dad.

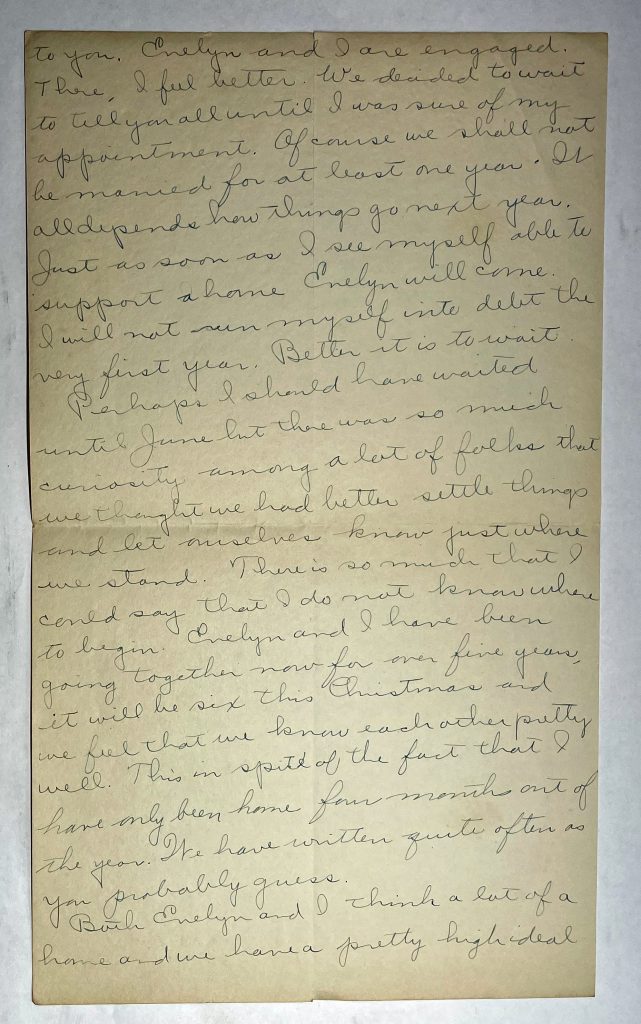

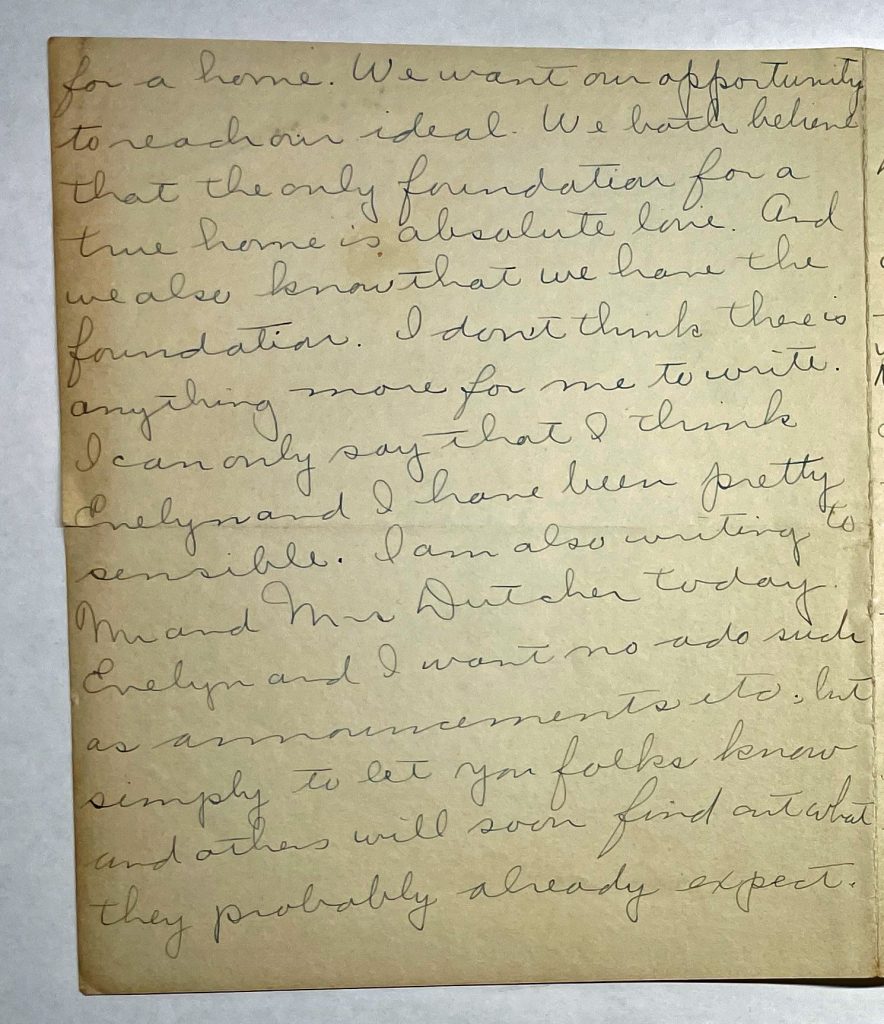

It is hard to write but perhaps it should not be. But since I have been given credit for being brief and to the point I can say all that I have to say in one sentence. It probably will be no surprise to you. Evelyn and I are engaged. There, I feel better. We decided to wait to tell you all until I was sure of my appointment. Of course we shall not be married for at least one year. It all depends how things go next year. Just as soon as I see myself able to support a home Evelyn will come. I will not run myself into debt thievery first year. Better it is to wait.

Perhaps I should have waited until June but there was so much curiosity among a lot of folks that we thought we had better settle things and let ourselves know just where we stand. There is so much that I could say that I do not know where to begin. Evelyn and I have been going together now for over five years, it will be six this Christmas and we feel that we know each other pretty well. This in spite of the fact that that I have only been home four months out of the year. We have written quite often as you probably guess.

Both Evelyn and I think a lot of a home and we have a pretty high ideal for a home. We want our opportunity foreach our ideal. We both believe that the only foundation for a true home is absolute love. And we also know that we have the foundation. I don’t think there is anything more for me to write. I can only say that I think Evelyn and I have been pretty sensible. I am also writing to Mr. And Mrs. Dutcher today. Evelyn and I want no ado such as announcements etc., but simply to let you folks know and others will soon find out what they probably already expect.

The following are copies of the actual letter to his mother.

Wedding Day

They were married on Harold’s birthday June 29, 1926. After their wedding, they immediately left for Harold’s pastoral duties and initially lived in the Jonesville parsonage.

The following photo was taken on Harold and Evelyn’s wedding day. Harold and Evelyn are peeking out of the window behind their parents and Harold’s aunt Kate Sperber. The photograph was taken at Evelyn’s parent’s house, 27 North Judson Street, Gloversville, New York. In the photograph from left to right: Aunt Kate Sperber, Ida Sperber Griffis, Charles Griffis, Mary Jane Platts Dutcher, and Squire Dutcher.

The photograph of the wedding party below is also taken at 27 Judson Street. From left to right: Bernice Dutcher, who was Evelyn’s cousin; Evelyn Dutcher; Harold Griffis; and Russell Lane, Benice’s future husband. On the porch, to the right, is Charles Griffis looking on as the photograph was taken.

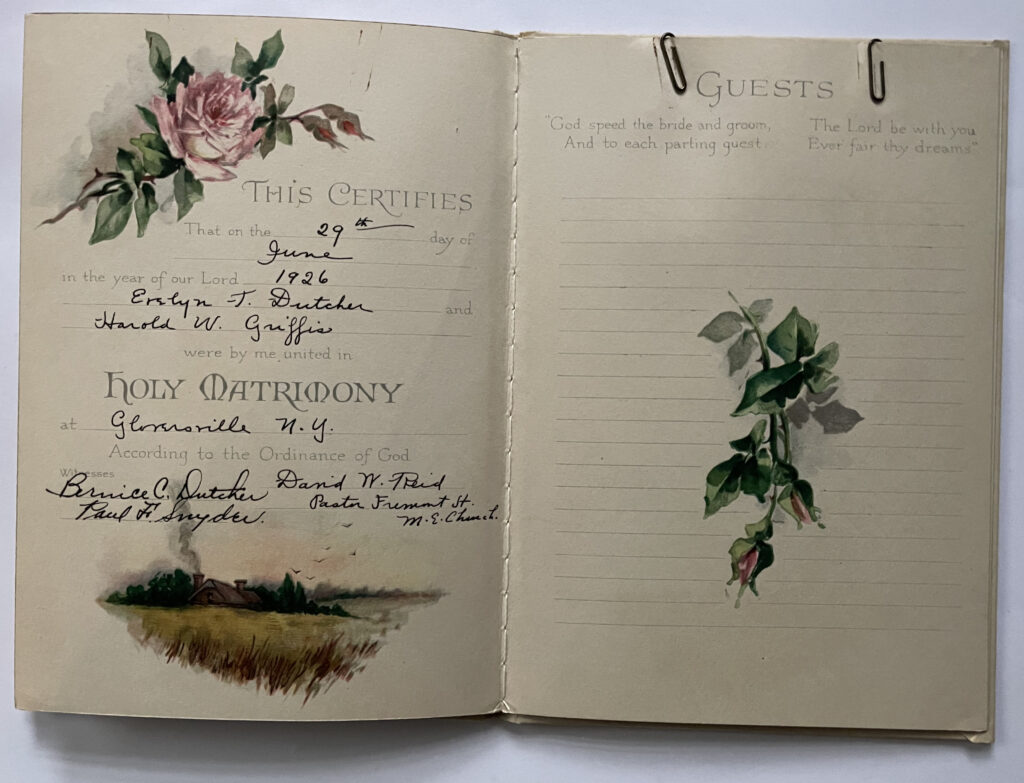

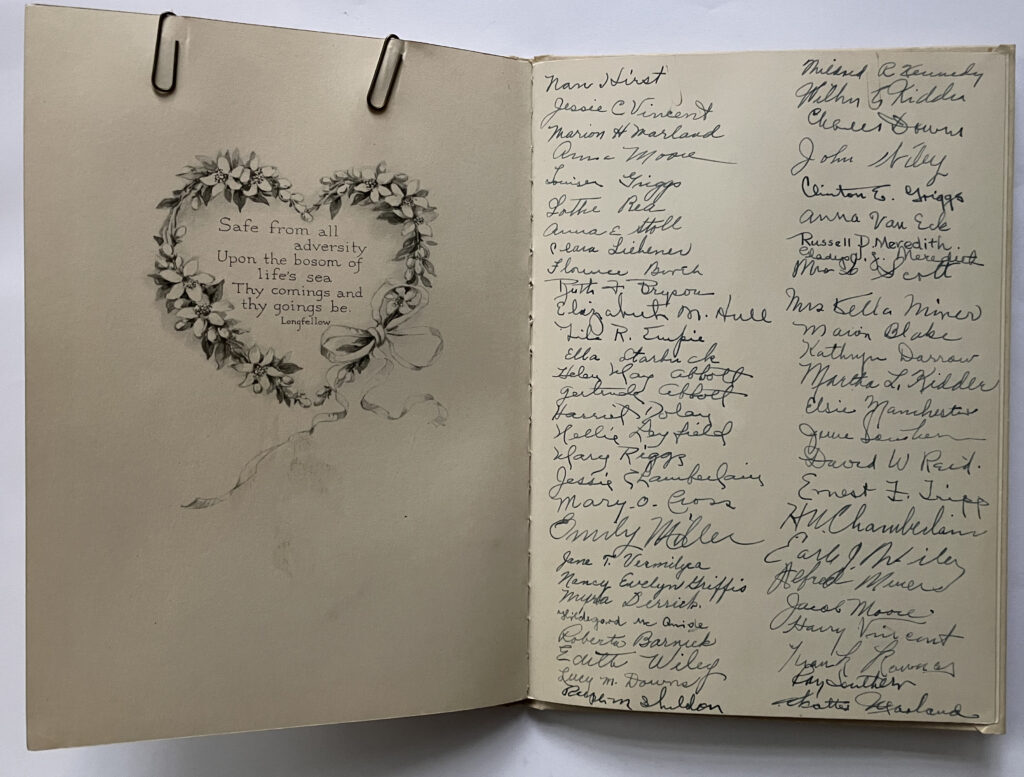

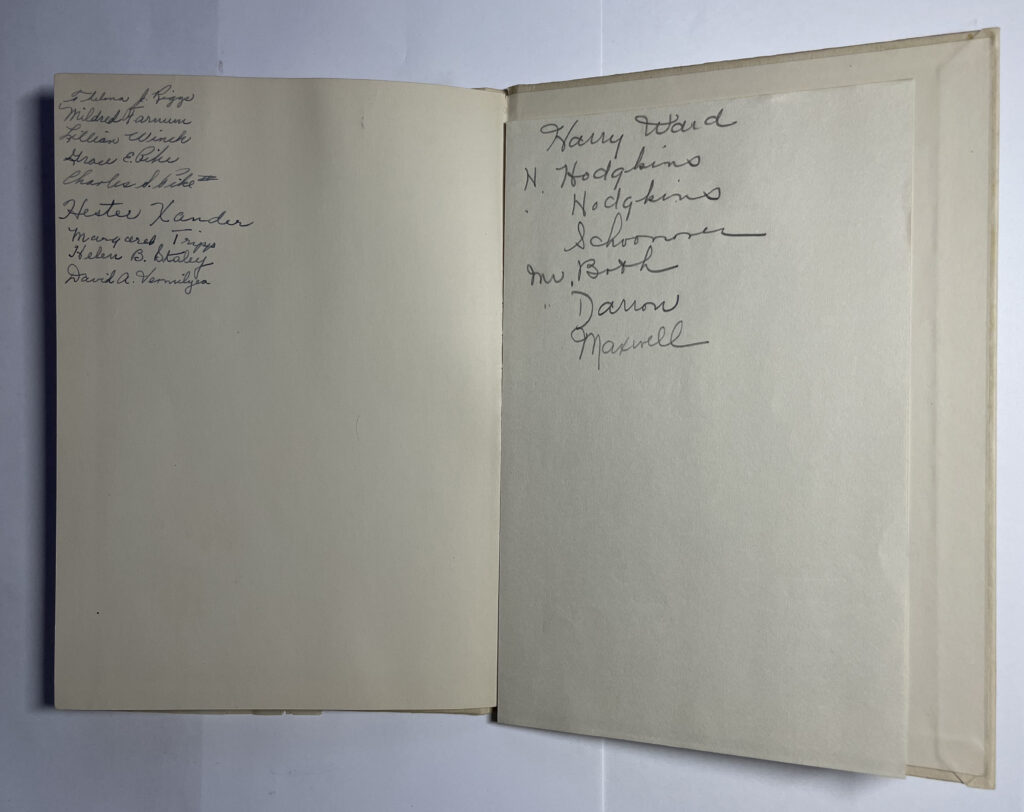

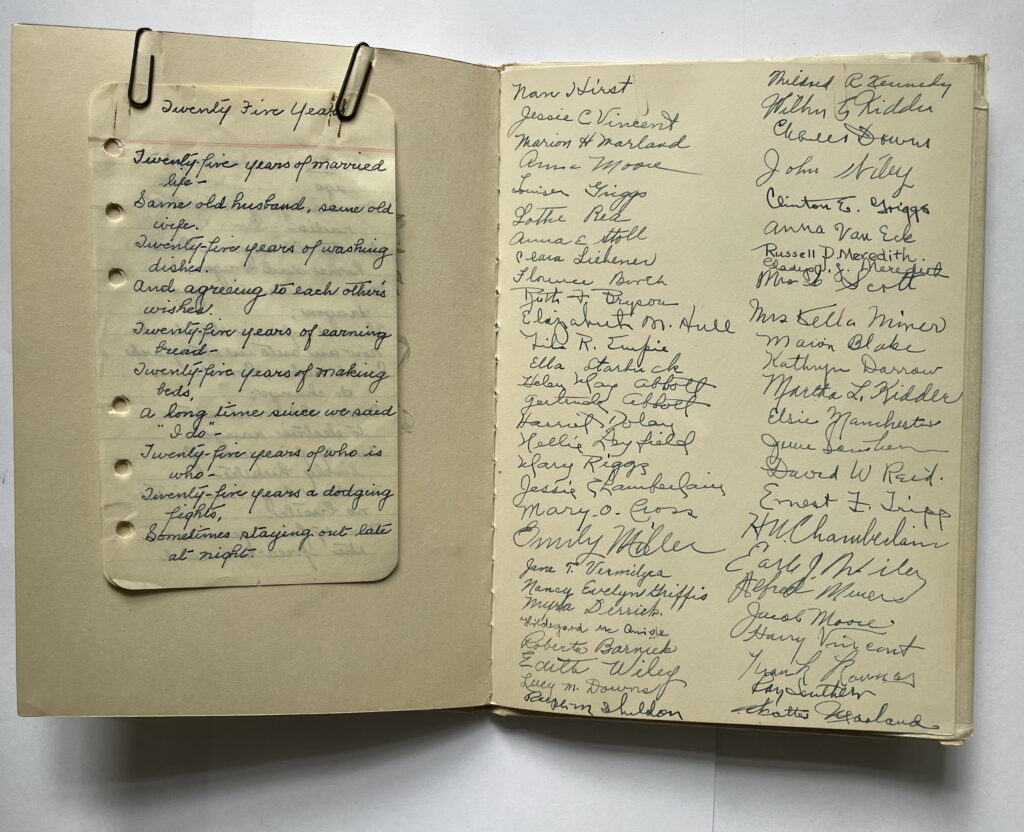

The following is Harold and Evelyn’s marriage guest book. Harold W. Griffis and Evelyn T. Dutcher were married in the Fremont Street Methodist episcopal Church by the pastor David W. Reid. their witnesses were Bernice Dutcher, Evelyn’s cousin and another cousin, Paul Snyder. The pages that include names of individuals who attended the wedding or gave gifts must have been amended many years after the actual date. The name ‘Nancy Evelyn Griffis’ is listed but Nancy is Harold and Evelyn’s fourth child.

1926 was a year of many milestones for both young Harold and Evelyn. It began their 35 years together as husband and wife. Harold was starting his career as a pastor. Harold lost his father, Charles, in the latter part of the year. Evelyn ended a brief teaching career after graduating from college and devoted her attention to her role as a pastor’s wife until Harold passed away a day after his birthday on June 30, 1961.

Twenty Five Years Later – 1951

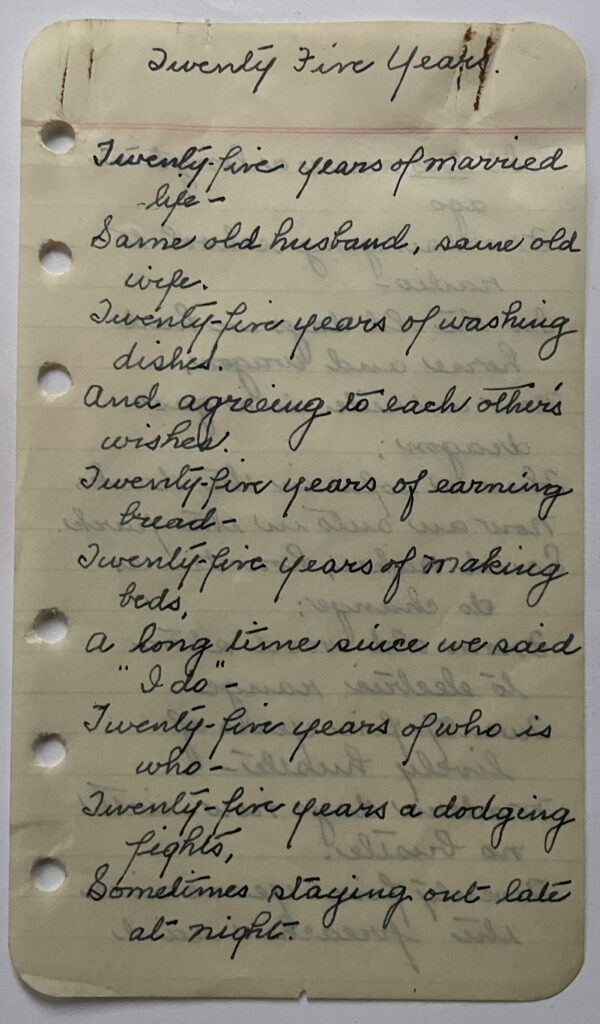

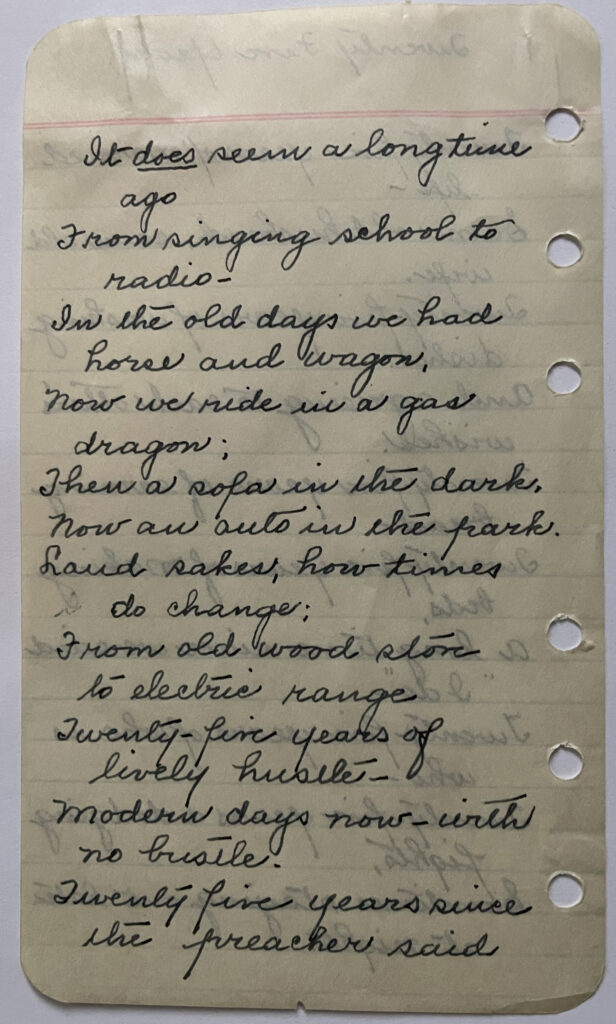

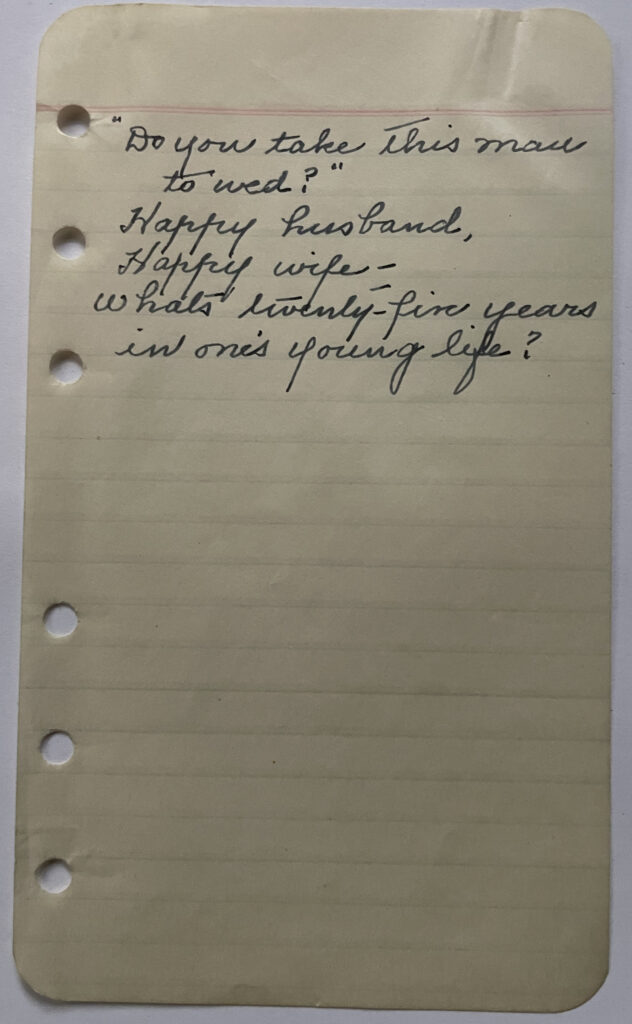

The following handwritten notebook pages were attached in the Guestbook. After viewing their handwriting, I believe the poem was written and transcribed by Evelyn. She probably placed it into the Guest book around their 25th wedding anniversary. Click for larger view.

The following are the three handwritten notebook pages that were attached in the Guestbook.

Sources

Featured image: This is a blow up of the first sentence in a letter Harold Griffis wrote to his future in-laws, Squire and Jane Dutcher, regarding his engagement with Evelyn Dutcher and his plans and intentions for marriage.

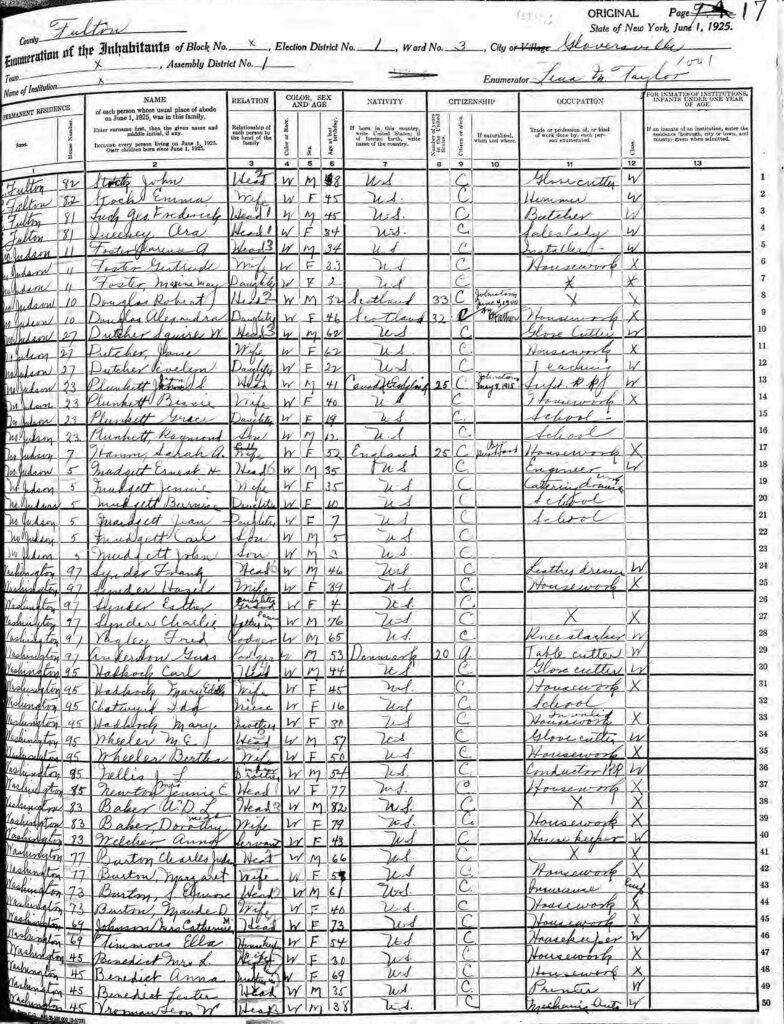

[1] New York State Census, 1925, Fulton County, Gloversville, Election District 1, Ward 3, Assembly District 1, Page 17, Lines 10-12

[2] Ian Webster, $1 in 1925 is worth $14.60 in 2018, CPI Inflation Calculator, https://www.officialdata.org/1925-CAD-in-2018

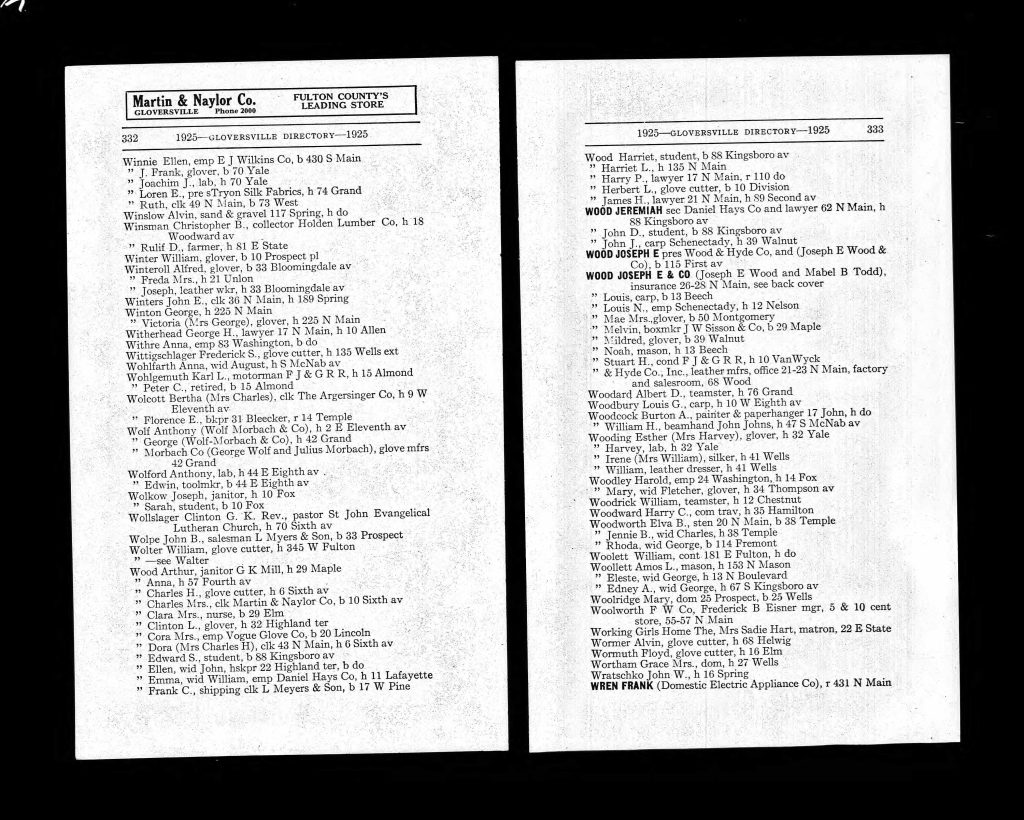

[3] Jeremiah Wood was born in Mayfield, New York on 6 Jan 1874 and died 5 May 1942 in Gloversville. Jeremiah Wood was a Lawyer in Gloversville for a number of years, as reflected in a number of Gloversville City Directories. The Gloversville City Director below lists Wood as a lawyer with Daniel Hayes Co. in 1925, located at 62 North Main Street, Gloversville, N.Y. it is interesting to note that Jeremiah Wood’s grandfather was Rev. Jeremiah Wood, a pastor for 50 years at the Mayfield Presbyterian Church. It is not known if this is the church that Charles Griffis was a deacon.

Source: 1925 Gloversville City Directory , Page 333, Ancestry.com. U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

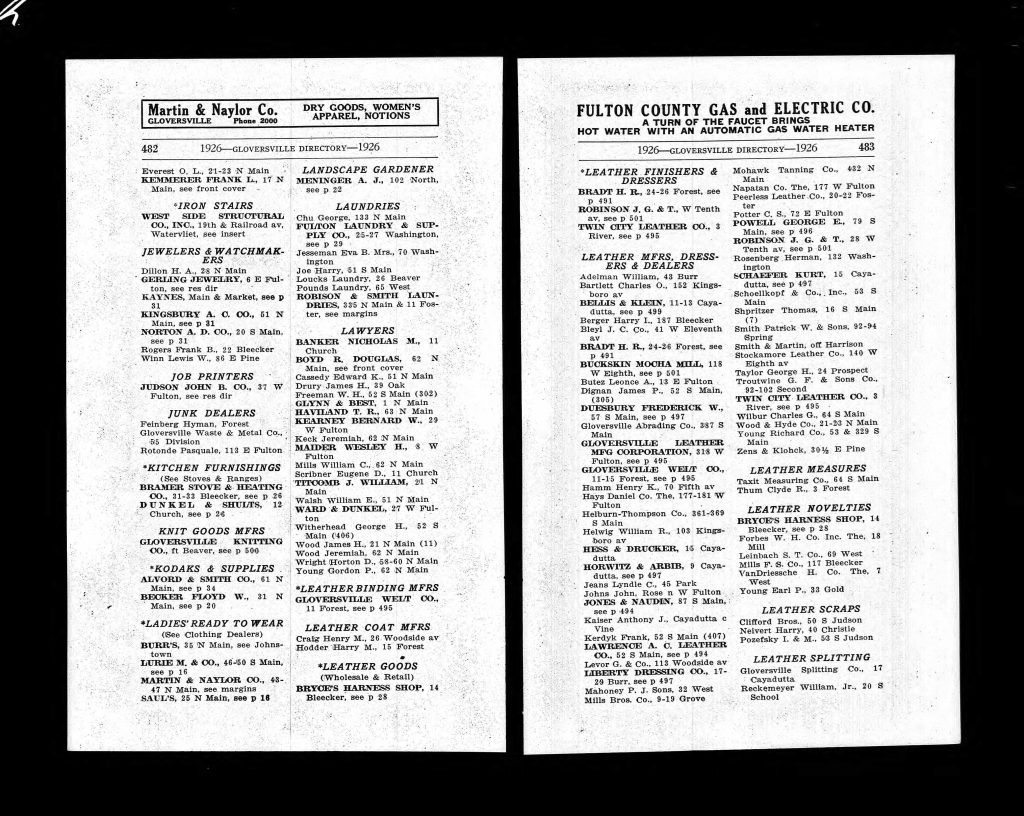

Source: 1926 Gloversville City Directory, Page 482, Ancestry.com. U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.